Abstract

Introduction:

The use of telehealth screening (TS) for diabetic retinopathy (DR) consists of fundus photography in a primary care setting with remote interpretation of images. TS for DR is known to increase screening utilization and reduce vision loss compared with standard in-person conventional diabetic retinal exam (CDRE). Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor intravitreal injections have become standard of care for the treatment of DR, but they are expensive. We investigated whether TS for DR is cost-effective when DR management includes intravitreal injections using national data.

Materials and Methods:

We compared cost and effectiveness of TS and CDRE using decision-tree analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis with Monte Carlo simulation. We considered the disability weight (DW) of vision impairment and 1-year direct medical costs of managing patients based on Medicare allowable rates and clinical trial data. Primary outcomes include incremental costs and incremental effectiveness.

Results:

The average annual direct cost of eye care was $196 per person for TS and $275 for CDRE. On average, TS saves $78 (28%) compared with CDRE and was cost saving in 88.9% of simulations. The average DW outcome was equivalent in both groups.

Discussion:

Although this study was limited by a 1-year time horizon, it provides support that TS for DR can reduce costs of DR management despite expensive treatment with anti-VEGF agents. TS for DR is equally effective as CDRE at preserving vision.

Conclusions:

Annual TS for DR is cost saving and equally effective compared with CDRE given a 1-year time horizon.

Keywords: diabetes, teleretinal screening, fundus photography, decision-tree analysis, telemedicine

Introduction

With the rising prevalence of diabetes, by the year 2050, almost 20 million people older than 40 years in the United States are projected to have diabetic retinopathy (DR), the leading cause of blindness among working-age Americans.1 It is essential to annually screen patients for DR because damage is often visible on physical examination long before patients become symptomatic. Moreover, treatments for DR are effective at slowing the progression of disease, but they may not be able to reverse severe damage. Despite the proven effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of early detection, only 20–60% of patients with diabetes receive an annual dilated fundus examination, the standard of care based on published guidelines.2–4 Once identified, modern treatments for DR are very effective, but expensive.

Traditionally, the treatment for progressing DR has been focal laser or pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP). However, newer intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections are taking over as first-line therapy owing to improved outcomes and adverse events. However, these new anti-VEGF agents are exceedingly expensive compared with laser. Anti-VEGF agents alone made up >14% of the Medicare Part B's total drug spending for 2018,5 costing ∼$1,500 per injection.6 Although it is important to implement public health programs that seek to improve DR screening utilization, increased treatment costs need to be anticipated as a natural consequence of prevalent, but undiagnosed vision-threatening disease.7

One proposed method to increase uptake of DR screening while reducing costs is telehealth screening (TS). TS can be implemented in primary care offices using nonmydriatic fundus photography, with remote interpretation of retinal images.3 Studies have shown that the majority of patients prefer the experience of TS over a live examination owing to its convenience,8–10 and multiple studies suggest that TS programs can be cost-effective.7,11–13 However, although there have been studies that highlight the cost-effectiveness of intravitreal anti-VEGF for treatment of DR,14–16 there are limited studies analyzing the cost-effectiveness of TS for DR and management that consider the costs associated with expensive anti-VEGF medications.

The objective of this study was to determine whether TS for DR would be an effective intervention to improve quality of care and reduce per capita costs. In particular, we sought to explore how costs change with the increased uptake expected with TS over conventional diabetic retinal exam (CDRE). In this study, we analyzed the cost and effectiveness of TS and management of DR, including anti-VEGF drugs, compared with CDRE and management of DR in a U.S. population of people with diabetes using decision tree analysis.

Materials and Methods

We determined cost and effectiveness using decision tree analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis with TreeAge Pro™ software (TreeAge Software, Inc., Williamstown, MA). The University of Vermont Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from review as nonhuman subjects research. We compared annual teleretinal screening to annual dilated eye examination performed by an optometrist or ophthalmologist (CDRE). The study population is people in the United States with diagnosed diabetes mellitus.

From the health care system perspective, we considered the direct medical costs of screening and the direct medical costs for a 1-year time horizon of managing and treating patients who screen positive for any severity of DR or diabetic macular edema (DME) in our base case. We based the costs on clinical trials that evaluated total yearly costs for diagnosis and treatment of varying severity of DR, including the cost of usage of ranibizumab for proliferative DR (PDR) and DME (Table 1).15,16 Hutton et al.16 reported 2-year costs only, so to estimate 1-year costs for this study, those values were multiplied by 0.67, assuming that more of the costs would be accrued within the first year of diagnosis and treatment.

Table 1.

Estimated Values of Variables in Decision Tree Analysis and their Source

| VARIABLE | BASE CASE | LOW VALUE | HIGH VALUE | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of Attending Screening | 0.50 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 2,3,17 |

| Probability of Teleretinal Screen being Positivea | 0.35 | 0.1 | 0.41 | 13,18,19,20 |

| Probability of Teleretinal Screen Positive being Falsea | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.48 | 13,18,19 |

| Probability of Teleretinal Screen Negative being Falsea | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 18,19 |

| Probability of CDRE False Negativea | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 21 |

| Probability of CDRE Positivea | 0.26 | 0.1 | 0.28 | 20,21 |

| Prevalence of DR | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 18,22–24 |

| Prevalence of PDR | 0.065 | 0.025 | 0.105 | 23–25 |

| Prevalence of DR without DME | 0.932 | — | — | 22 |

| Prevalence of mild NPDR out of all DR | 0.588 | — | — | 22 |

| Prevalence of DME | 0.068 | — | — | 22 |

| Prevalence of DME with VA 20/25 or better | 0.5 | — | — | 26 |

| Prevalence of DME with VA 20/25 or better that will need treatment within one year | 0.34 | — | — | 27 |

| Prevalence of DME with VA 20/32–20/40 | 0.34 | — | — | 26 |

| Prevalence of DME with VA 20/50 or worse | 0.39 | — | — | 26 |

| Probability of attending CDRE with visual symptoms or screen positive | 0.95 | — | — | 28 |

| Probability of Going Blind from Untreated DME without symptoms | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 19,29 |

| Probability of Going Blind from Untreated PDR without symptoms | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 19,29 |

| Probability of PDR symptoms in a year | 0.141 | — | — | 13 |

| Probability of DME symptoms in a year | 0.106 | — | — | 13 |

| Probability of Going Blind from PDR after PRP | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 19,29 |

| Annual Cost of PRP for PDR | $6,020 | $4,942 | $7,099 | 16 |

| Annual Cost of Ranibizumab for DME with VA 20/40 or betterb | $19,924 | $17,740 | $22,953 | 15,30 |

| Annual Cost of Ranibizumab for DME with VA 20/50 or worseb | $23,769 | $21,585 | $26,403 | 15,30 |

| Annual Cost of Ranibizumab for PDR with DME and VA 20/40 or betterb | $24,219 | $22,036 | $26,403 | 15,16 |

| Annual Cost of Ranibizumab for PDR with DME and VA 20/50 or worseb | $24,765 | $22,582 | $26,949 | 15,16 |

| Cost of One Follow Up Eye Examb | $124 | — | — | 5,30, code 92014 |

| Cost of One New Patient Ophthalmology Examb | $149 | — | — | 30, code 92004 |

| Cost of Telescreen Examb | $15 | — | — | 30, code 92227 |

| Indirect Cost of One Ophthalmology Clinic Visitb | $25 | — | — | 31 |

| Disability Weight of Mild Vision Impairment | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 32 |

| Disability Weight of Moderate Vision Impairment | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.049 | 32 |

| Disability Weight of Severe Vision Impairment | 0.184 | 0.125 | 0.258 | 32 |

| Disability Weight of Blindness | 0.187 | 0.124 | 0.260 | 32 |

| Disability Weight of No Vision Impairment | 0 | — | — | Assumption |

Calculated based on prevalence, specificity, and sensitivity data not shown.

USD 2020 values converted from US inflation calculator based on U.S. Labor Department's Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index.33

CDRE, conventional diabetic retinal exam; DME, diabetic macular edema; DR, diabetic retinopathy; NPDR, nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy; PDR, proliferative diabetic retinopathy; PRP, pan-retinal photocoagulation; VA, visual acuity.

We used clinical trials to estimate costs to holistically estimate the total direct medical costs for the entirety of a patient's ophthalmologic care, including the costs of managing subsequent adverse events and surgeries. Other costs were estimated based on national Medicare allowable fees (Table 1) without geographic adjustment factors. In addition, we performed a secondary analysis for societal perspective, which considered indirect costs based on previously derived nonmedical costs of attending a vitreoretinal clinic, including transportation costs and loss of wages for both the patient and accompanying person ($25/visit).31 Discounting was not included in this study because of the short 1-year time horizon. Cost data were from the years 2014 to 2019, which was adjusted for inflation to 2020 USD amounts.33

We analyzed effectiveness by considering the associated disability weight (DW) of various levels of vision impairment at the end of the 1-year time horizon. These values were based on the Global Burden of Disease Study,32 which is widely used across medical disciplines to estimate disability of various medical states ranging from 0 (perfect health) to 1 (equivalent to death) (Table 2). We assumed that treatment of PDR with PRP would sustain the current level of visual impairment, whereas the treatment of DME with intravitreal anti-VEGF would improve the current visual impairment status by one level (e.g., moderate vision impairment becomes mild vision impairment). We accounted for improved vision outcomes with early initiation of treatment in the screening groups compared with the no-screening groups by differing rates of blindness and vision impairment.

Table 2.

Effectiveness Outcomes in Decision Tree Analysis Based on the 2013 Global Burden of Disease Study19

| VISION HEALTH STATE | VA | DW |

|---|---|---|

| Mild impairment | 20/40 to 20/60 | 0.003 |

| Moderate impairment | <20/60 to 20/200 | 0.031 |

| Severe impairment | <20/200 to 20/400 | 0.184 |

| Blind | <20/400 | 0.187 |

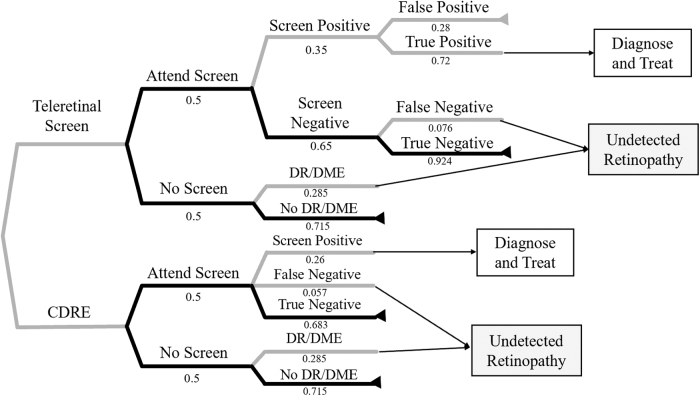

We based the design of the tree (Fig. 1; Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2) on updated practice guidelines20 and high-quality cost-effectiveness analyses.15,16,34 We designed the structure of the undetected retinopathy subtree (Supplementary Fig. S1) from the natural progression of retinopathy and DME with the assumption that people would present for treatment only if vision symptoms were to occur. We based the structure of the subtree for diagnosing and treatment of DR (Supplementary Fig. S2) on the varying costs and vision outcomes associated with differing severities of visual acuity, DME status, and severity of DR that are found in the literature.15,16,35 We based prevalence of DR and its subtypes on epidemiologic studies.22–26

Fig. 1.

Simplified decision tree base case comparing teleretinal screen intervention with a CDRE intervention. Branches from a vertex represent the possible outcomes of an event; terminal nodes (◃) are assigned the cost and effectiveness based on values from the literature. The black lines represent the two most likely pathways through each tree and the gray lines represent all other pathways (DR and DME). CDRE, conventional diabetic retinal exam; DME, diabetic macular edema; DR, diabetic retinopathy.

In the TS intervention, we designated ungradable images as “positive screens” all of whom receive a diagnostic CDRE. We predicted the progression of disease over time with and without early detection, and specificity and sensitivity of screening on values from multiple previous cost-effectiveness analyses for TS (Table 1).13,18,19,29 The main outcomes of our analysis included incremental cost and incremental effectiveness.

To address uncertainty, we performed probabilistic sensitivity analysis using Monte Carlo simulation using 100,000 trials. We used a triangular distribution for each value in the models based on high and low estimates from the literature (Table 1), with the exception of screen positivity percentage in the TS arm, for which we used a uniform distribution to reflect widely varying thresholds for screening sensitivity (any DR, “vision-threatening” DR, moderate NPDR, etc.). Main outcomes of interest include the probability that teleretinal screening is cost saving and more effective.

We performed a one-way sensitivity analysis to determine how altering the cost of remote fundus photography ultimately affects the overall cost-effectiveness of TS. In addition, we performed one-way sensitivity analysis for the variable of utilization of teleretinal screening to determine how increasing screening uptake would affect the cost savings and vision savings of the interventions.

Results

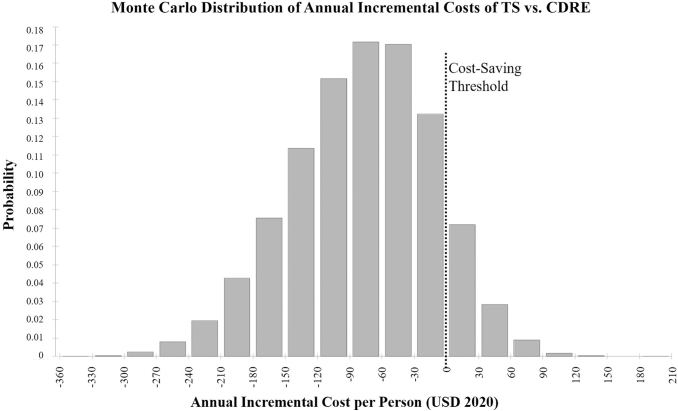

The decision tree roll-back analysis indicated that the single most likely pathway for a given patient was to not have DR and not attend screening (probability = 0.358; Fig. 1) because the prevalence of DR is <50%. Across all potential outcomes and treatments in the base case, the average annual direct medical cost for all eye care was $196/person in the TS group, and $275/person in the CDRE group, for an average annual cost savings of $78/person. Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analysis revealed that TS intervention was cost saving in 88.9% of trials (Fig. 2). Secondary analysis including the indirect costs of attending in-person ophthalmology visits demonstrated the average cost is $203/person in the TS group, and $291/person in the CDRE group for an average cost savings of $88/person.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of base case annual incremental costs (teleretinal costs—CDRE costs) per person from the Monte Carlo simulation comparing teleretinal screening costs and CDRE. On average, TS was $78 less expensive and was cost saving 88.9% of the time (TS and CDRE). TS, telehealth screening.

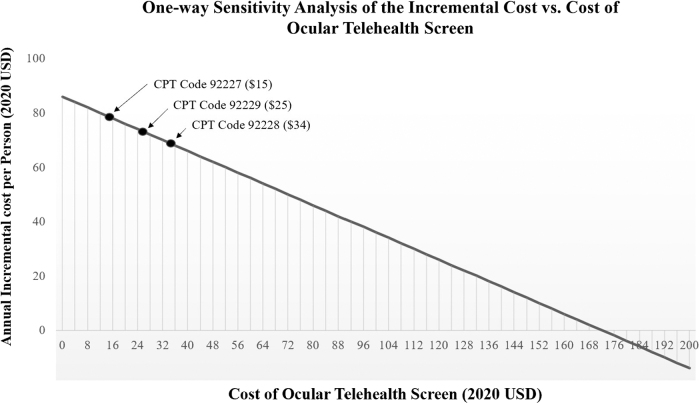

TS and CDRE both had the same average DW outcome of 0.001. TS is more effective in 64.5% of trials with an average incremental effectiveness of −2 × 10−5 (Fig. 3). One-way sensitivity analysis of the annual incremental cost at varying costs of ocular telehealth shows that TS is cost saving when the cost of ocular telehealth is <$172 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of base case analysis of incremental effectiveness from the Monte Carlo simulation comparing teleretinal screen compared with CDRE in DW. On average, TS has a DW 2 × 10−5 DALYs less than CDRE, making TS is more effective than live screen 64.5% of the time by a small, likely clinically insignificant margin. DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years; DW, disability weight.

Fig. 4.

One-way sensitivity analysis of the incremental cost (CDRE cost—TS cost) at different costs for ocular telehealth. TS is cost saving when the cost of the ocular telehealth screen is $172 or less. Points labeled on the graph represent commonly used CPT codes for telescreening without interpretation (92227) with incremental cost saving of $78.50, telescreening with interpretation (92228) with incremental cost saving of $69, and telescreening with artificial intelligence (92229) with incremental cost saving of $73.50. CPT, Current Procedural Terminology.

One-way sensitivity analysis of the uptake of TS while the utilization to CDRE remains constant at 50% reveals that TS is vision saving when TS utilization is >48% and is cost saving when TS usage is <80%.

Discussion

TS for DR has been promoted as a way to improve screening utilization and save costs in an effort to improve vision in patients with diabetes. Studies have shown that the majority of patients prefer the experience of TS,8–10 and multiple studies support the claim that TS is cost-effective.7,11,13,36 However, there are limited studies analyzing the cost and effectiveness of TS that consider the increased cost burden of the newer intravitreal anti-VEGF agents.

This study did include the costs of anti-VEGF agents and found that TS is cost saving compared with live screening for a 1-year time horizon when considering the total direct medical costs for an entire year, with an average annual cost savings of $78 per person. In our conservative model, those with DR had an elevated cost of management owing to having both a telescreen and a CDRE, as opposed to a single CDRE. However, this study demonstrates that the increased cost to those with DR is offset by the decreased cost to those without DR. Those without DR save costs by allowing people without the disease to avoid the $149 cost of an examination with an eye care professional and instead get a less expensive teleretinal screen for $15 in the base case (Medicare allowable for Current Procedural Terminology [CPT] code 92227).30

Secondary analysis, which considered the indirect costs saving associated with avoiding a clinic visit,31 demonstrated that an additional $10 per person on average can be saved. This included the average costs of transportation and lost wages. It is important to note that many people screened in a CDRE paradigm by an optometrist or nonretinal ophthalmologist will still require a second evaluation and management charge from their ultimate retinal physician, and so cost savings may be underestimated by assuming CDRE to only require a single examination.

This study also demonstrates that a TS intervention is equally effective compared with the CDRE. The reason for small differences in effectiveness between the interventions is driven by the differences in sensitivity and specificity. Because a CDRE is generally reported to be more specific and less sensitive than the telescreen, there are more false-negative results in CDRE. This leads to an increased amount of undetected retinopathy, which leads to poorer vision outcomes. However, the differences in effectiveness are negligible in this study, as a DW difference of 2 × 10−5 is likely not clinically significant, given a DW for mild vision impairment is 0.003. Clinically meaningful differences could emerge were a time horizon longer than 1 year is chosen for analysis, particularly if differential rates of screening are observed in one arm.

Because TS is expected to lead to improved screening uptake,10 cost savings may be overestimated and effectiveness may be underestimated in our base case, which assumed equal uptake of screening in both interventions in the interest of being conservative. To further explore this, one-way sensitivity analysis of the teleretinal screening utilization was performed. This demonstrated the hypothesized trend that improved screening utilization in the TS branch compared with the CDRE branch results in TS being less cost saving and more vision saving. As screening uptake for TS increases to 80%, it will no longer be cost saving compared with CDRE uptake at a base rate of 50%. However, our model also demonstrates that TS will be increasingly vision saving compared with CDRE once the TS screening utilization is >48%.

In this study, ranibizumab was selected as the agent of choice in our base case model for several reasons. The first is that ranibizumab was the first agent to be FDA-approved for DME and more cost-effectiveness studies have been performed with this agent, which allows this study to have a more robust approach to the costs of treatments for varying levels of DME as well as PDR. It is also the second-most expensive of the three intravitreal anti-VEGF agents and therefore is expected to yield more conservative results than using the least expensive agent.

However, Ross et al.15 demonstrated that management of DME with bevacizumab saves $14,500 in the first year of treatment. A secondary analysis in which estimated annual bevacizumab costs were used instead demonstrated the predicted finding that annual treatment costs per person in both telescreen and CDRE intervention would be decreased by $80 and $95, respectively, and that teleretinal screening would be cost saving at higher screening adherence rates compared with the base case (87% instead of 80%, data not shown).

Another factor that will alter the cost-effectiveness of TS is the cost associated with the telescreen itself. This study used the Medicare value of $15/screen in the base case with use of CPT code 92227.30 In general, the reimbursement of teleretinal screening might need to be greater to implement sustainable programs. This study suggests a reimbursement of TS up to $172 would be cost saving compared with a live examination for the first year. Figure 4 demonstrates the cost savings (although more modest) of the other commonly used CPT codes 92228 and 92229 using artificial intelligence to grade images.

These results are encouraging that TS is a cost saving and effective strategy for the screening and subsequent management of DR, even when the cost to treat DR can be exceedingly high. Many other studies have found similar results. Garoon et al., Brady et al., and Coronado et al. highlight the potential for cost savings of teleretinal screening.11,37,38 Rein et al.13 is an example of one of very few studies that have considered the prices of intravitreal anti-VEGF drugs in the cost, but that study differs from this one in that it was not targeting the differences between teleretinal screening and CDRE. This study helps bolster support that telescreening for DR will provide quality, cost saving care that will improve population health, despite the growing costs of management of DR with the advent of anti-VEGF agents.

Economic modeling necessarily entails simplification and assumptions to obtain operational results, although every attempt was made to make an accurate model that is supported by data. Whenever possible, the model was designed to be conservative, to underestimate the value of TS. A key limitation of this model is its 1-year time horizon, which allows a detailed look at what occurs during the first year of management and screening, but cannot consider the important implications of DR in the long-term both on costs and vision impairment. However, the 1-year time horizon did allow us to analyze vision impairment outcomes with DWs from the Global Burden of Disease study, which provides benchmark metrics across all medical disciplines.

Another consideration is the use of clinical trials for costs, which could be an overestimate of true costs of treatment outside a rigorous study, but has the benefit of including necessary costs of managing complications and other aspects of care that could be erroneously excluded using other methods. We also did not include the long-term indirect costs associated with visual impairment, such as loss of future wages or costs of hired caretakers.

In addition, the model lacked analysis of concurrent ocular diseases. Their inclusion would likely increase costs and vision saving from screening interventions owing to incidentally finding and treating other eye diseases, as evidenced in Chasan et al.7 Finally, this model assumes that everyone who screens positive in either arm will show up to their follow-up appointments. This is not a realistic assumption, because the barriers that lead to poor in-person screening in the first place are still present.7,39

However, there is a lack understanding of what proportion of people link to subspecialty retina care in the context of routine DR screening performed by optometrists or comprehensive ophthalmologists, or how linkage to care would be affected by TS compared with CDRE. Perhaps uptake would be improved by a “warm handoff” in a TS intervention in which a direct referral and appointment could be made on the spot,40 although this would necessitate a real-time diagnosis, which is a challenge in conventional asynchronous telehealth, but may be facilitated by point-of-care diagnosis using artificial intelligence.41,42 Although the aforementioned limitations may decrease the accuracy of the exact predicted dollar amounts of each intervention, it is also true that these assumptions were applied equally to both arms, and therefore do not directly impact the ability to compare them or our overall inferences.

Conclusions

This study provides evidence that TS for DR is a cost-saving strategy for managing an increasingly expensive disease, although future research needs to be performed into the long-term and indirect costs of teleretinal screening to be certain that these benefits are not transient. In addition, implementation of teleretinal screening in different settings will be important to identify which factors make TS more effective, cost saving, and perhaps better quantify potential improvements in access to care.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contribution

D.M.C. contributed to the work in the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data as well as drafting the article. B.Y.K. and N.W. contributed to the conception and design of the study as well as critically revising of the article. D.S.S. contributed to the work in the analysis and interpretation of the data as well as critically revising the article. C.J.B. contributed to the conception and design of the work, analysis and interpretation of the data, and critically revising the article.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

D.M.C., B.Y.K., N.W., and C.J.B. have no conflicts of interest to disclose. D.S.S. reports grants from Abbott, Inc., outside the submitted works.

Funding Information

D.M.C. and B.Y.K. was supported in part by the Elliot W. Shipman Professorship Fund. D.S.S. reports grants from Abbott, Inc., outside the submitted work. N.W. has no funding information to declare. C.J.B. was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P20GM103644.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Saaddine JB, Honeycutt AA, Narayan KM, Zhang X, Klein R, Boyle JP. Projection of diabetic retinopathy and other major eye diseases among people with diabetes mellitus: United States, 2005–2050. Arch Ophthalmol 2008;126:1740–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murchison AP, Hark L, Pizzi LT, et al. Non-adherence to eye care in people with diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2017;5:e-000333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Horton MB, Brady CJ, Cavallerano J, et al. Practice guidelines for ocular telehealth-diabetic retinopathy, third edition. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:495–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Benoit SR, Swenor B, Geiss LS, Gregg EW, Saaddine JB. Eye care utilization among insured people with diabetes in the U.S., 2010–2014. Diabetes Care 2019;42:427–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Part B Drug Spending and Utilization, Calendar Years 2014–2018. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/Historical_Data (last accessed January 17, 2022).

- 6. Konstantinidis L, Mantel I, Pournaras J-AC, Zografos L, Ambresin A. Intravitreal ranibizumab (Lucentis®) for the treatment of myopic choroidal neovascularization. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009;247:311–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chasan JE, Delaune B, Maa AY, Lynch MG. Effect of a teleretinal screening program on eye care use and resources. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:1045–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valikodath NG, Leveque TK, Wang SY, et al. Patient attitudes toward telemedicine for diabetic retinopathy. Telemed J E Health 2017;23:205–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurji K, Kiage D, Rudnisky CJ, Damji KF. Improving diabetic retinopathy screening in Africa: Patient satisfaction with teleophthalmology versus ophthalmologist-based screening. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2013;20:56–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gupta A, Cavallerano J, Sun JK, Silva PS. Evidence for telemedicine for diabetic retinal disease. Semin Ophthalmol 2017;32:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Garoon RB, Lin WV, Young AK, Yeh, AG, Chu, YI, Weng CY. Cost savings analysis for a diabetic retinopathy teleretinal screening program using an activity-based costing approach. Ophthalmol Retina 2018;2:906–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jones S, Edwards RT. Diabetic retinopathy screening: A systematic review of the economic evidence. Diabet Med 2010;27:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rein DB, Wittenborn JS, Zhang X, et al. The cost-effectiveness of three screening alternatives for people with diabetes with no or early diabetic retinopathy. Health Serv Res 2011;46:1534–1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brown GC, Brown MM, Turpcu A, Rajput Y. The Cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab for the treatment of diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2015;122:1416–1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ross EL, Hutton DW, Stein JD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of aflibercept, bevacizumab, and ranibizumab for diabetic macular edema treatment: Analysis from the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network Comparative Effectiveness Trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2016;134:888–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hutton DW, Stein JD, Bressler NM, Jampol LM, Browning D, Glassman AR. Cost-effectiveness of intravitreous ranibizumab compared with panretinal photocoagulation for proliferative diabetic retinopathy: Secondary analysis from a diabetic retinopathy clinical research network randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:576–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Phan AD, Koczman JJ, Yung CW, Pernic AA, Doerr ED, Kaehr MM. Cost analysis of teleretinal screening for diabetic retinopathy in a county hospital population. Diabetes Care 2014;37:301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. James M, Turner DA, Broadbent DM, et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of screening for sight threatening diabetic eye disease. BMJ 2000;320:1627–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu B, Li J, Wu H. Strategies to screen for diabetic retinopathy in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e-1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jani PD, Forbes L, Choudhury A, Preisser JS, Viera AJ, Garg S. Evaluation of diabetic retinal screening and factors for ophthalmology referral in a telemedicine network. JAMA Ophthalmol 2017;135:706–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Javitt JC, Aiello LP. Cost-effectiveness of detecting and treating diabetic retinopathy. Ann Intern Med 1996;124;164–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kanjee R, Dookeran RI, Mathen MK, Stockl FA, Leicht R. Six-year prevalence and incidence of diabetic retinopathy and cost-effectiveness of tele-ophthalmology in Manitoba. Can J Ophthalmol 2017;52 Suppl 1:S15–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yau JW, Rogers SL, Kawasaki R, et al. Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care 2012;35:556–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang X, Saaddine JB, Chou CF, et al. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the United States, 2005–2008. JAMA 2010;304:649–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, et al. The Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. III. Prevalence and risk of diabetic retinopathy when age at diagnosis is 30 or more years. Arch Ophthalmol 1984;102:527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study design and baseline patient characteristics. ETDRS report number 7. Ophthalmology 1991;98(5 Suppl):741–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Baker CW, Glassman AR, Beaulieu WT, et al. Effect of initial management with aflibercept vs laser photocoagulation vs observation on vision loss among patients with diabetic macular edema involving the center of the macula and good visual acuity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019;321:1880–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Whited JD, Datta SK, Aiello LM, et al. A modeled economic analysis of a digital tele-ophthalmology system as used by three federal health care agencies for detecting proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Telemed J E Health 2005;11:641–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rachapelle S, Legood R, Alavi Y, et al. The cost-utility of telemedicine to screen for diabetic retinopathy in India. Ophthalmology 2013;120:566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Physician fee schedule search. 2016. Available at https://www.cms.gov/medicare/physician-fee-schedule/search (last accessed January 17, 2022).

- 31. Smiddy RA, Smiddy WE. Nonmedical costs and implications for patients seeking vitreoretinal care. Retina 2014;34:1882–1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Salomon JA, Haagsma JA, Davis A, et al. Disability weights for the Global Burden of Disease 2013 study. Lancet Glob Health 2015;3:e712–e723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. US Inflation Calculator. 2021. [cited March 7, 2021]. Available at https://www.usinflationcalculator.com (last accessed January 17, 2022).

- 34. Kim SW, Kang GW. Cost-utility analysis of screening strategies for diabetic retinopathy in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2015;30:1723–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wong TY, Sun J, Kawasaki R, et al. Guidelines on Diabetic Eye Care: The International Council of Ophthalmology recommendations for screening, follow-up, referral, and treatment based on resource settings. Ophthalmology 2018;125:1608–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones CD, Greenwood RH, Misra A, Bachmann MO. Incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy during 17 years of a population-based screening program in England. Diabetes Care 2012;35:592–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Brady CJ, Villanti AC, Gupta OP, Graham MG, Sergott RC. Tele-ophthalmology screening for proliferative diabetic retinopathy in urban primary care offices: An economic analysis. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2014;45:556–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Coronado AC, Zaric GS, Martin J, Malvankar-Mehta M, Si FF, Hodge WG. Diabetic retinopathy screening with pharmacy-based teleophthalmology in a semiurban setting: A cost-effectiveness analysis. CMAJ Open 2016;4:e95–e102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peavey JJ, D'Amico SL, Kim BY, Higgins ST, Friedman DS, Brady CJ. Impact of socioeconomic disadvantage and diabetic retinopathy severity on poor ophthalmic follow-up in a rural Vermont and New York population. Clin Ophthalmol 2020;14:2397–2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ades PA, Keteyian SJ, Wright JS, et al. Increasing cardiac rehabilitation participation from 20% to 70%: A road map from the Million Hearts Cardiac Rehabilitation Collaborative. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;92:234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ Digit Med 2018;1:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Abramoff MD, Leng T, Ting DS, et al. Automated and computer-assisted detection, classification, and diagnosis of diabetic retinopathy. Telemed J E Health 2020;26:544–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.