Abstract

Background

Neck pain is common, disabling and costly. Exercise is one treatment approach.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of exercises to improve pain, disability, function, patient satisfaction, quality of life and global perceived effect in adults with neck pain.

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, MANTIS, ClinicalTrials.gov and three other computerized databases up to between January and May 2014 plus additional sources (reference checking, citation searching, contact with authors).

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing single therapeutic exercise with a control for adults suffering from neck pain with or without cervicogenic headache or radiculopathy.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently conducted trial selection, data extraction, 'Risk of bias' assessment and clinical relevance. The quality of the evidence was assessed using GRADE. Meta‐analyses were performed for relative risk and standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after judging clinical and statistical heterogeneity.

Main results

Twenty‐seven trials (2485 analyzed /3005 randomized participants) met our inclusion criteria.

For acute neck pain only, no evidence was found.

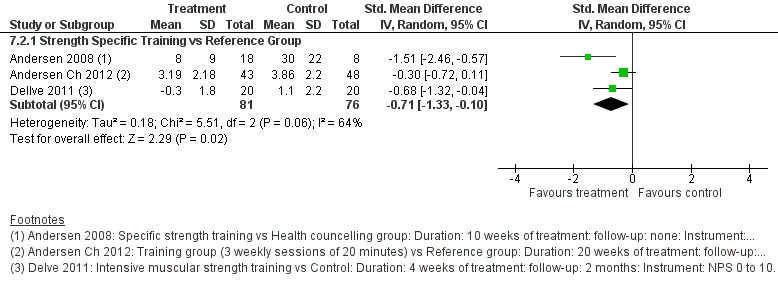

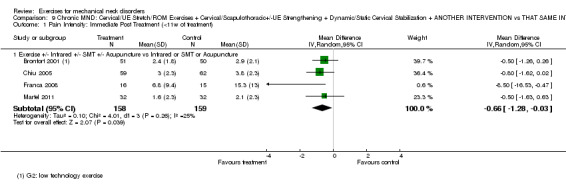

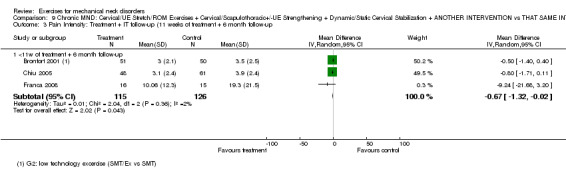

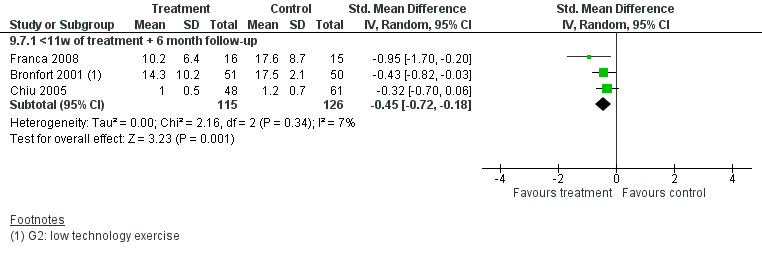

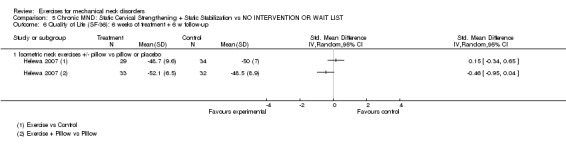

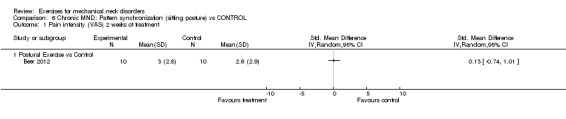

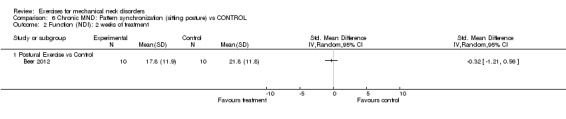

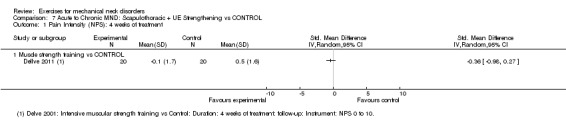

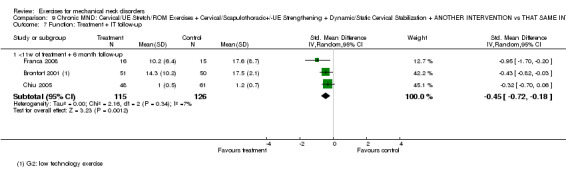

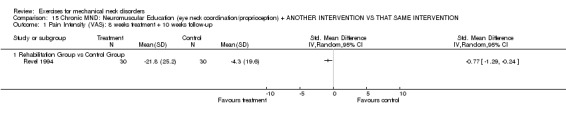

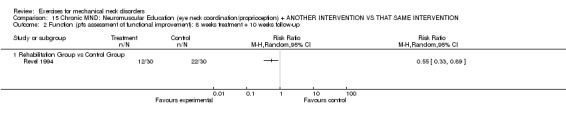

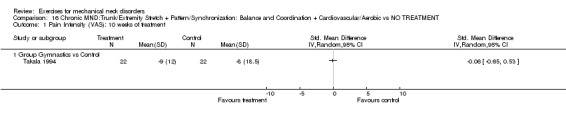

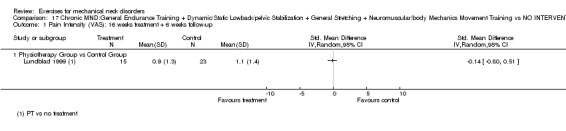

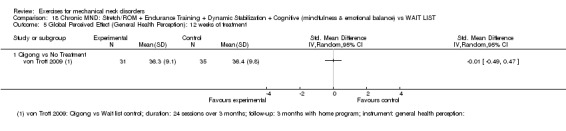

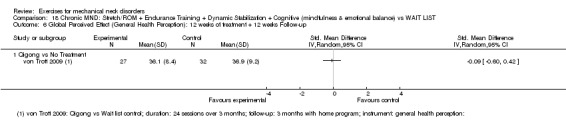

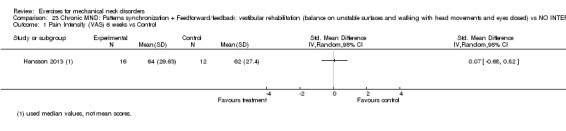

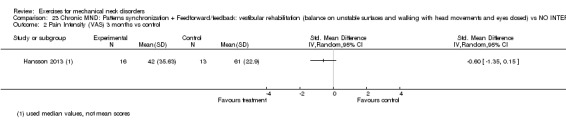

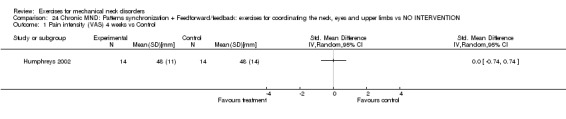

For chronic neck pain, moderate quality evidence supports 1) cervico‐scapulothoracic and upper extremity strength training to improve pain of a moderate to large amount immediately post treatment [pooled SMD (SMDp) ‐0.71 (95% CI: ‐1.33 to ‐0.10)] and at short‐term follow‐up; 2) scapulothoracic and upper extremity endurance training for slight beneficial effect on pain at immediate post treatment and short‐term follow‐up; 3) combined cervical, shoulder and scapulothoracic strengthening and stretching exercises varied from a small to large magnitude of beneficial effect on pain at immediate post treatment [SMDp ‐0.33 (95% CI: ‐0.55 to ‐0.10)] and up to long‐term follow‐up and a medium magnitude of effect improving function at both immediate post treatment and at short‐term follow‐up [SMDp ‐0.45 (95%CI: ‐0.72 to ‐0.18)]; 4) cervico‐scapulothoracic strengthening/stabilization exercises to improve pain and function at intermediate term [SMDp ‐14.90 (95% CI:‐22.40 to ‐7.39)]; 5) Mindfulness exercises (Qigong) minimally improved function but not global perceived effect at short term. Low evidence suggests 1) breathing exercises; 2) general fitness training; 3) stretching alone; and 4) feedback exercises combined with pattern synchronization may not change pain or function at immediate post treatment to short‐term follow‐up. Very low evidence suggests neuromuscular eye‐neck co‐ordination/proprioceptive exercises may improve pain and function at short‐term follow‐up.

For chronic cervicogenic headache, moderate quality evidence supports static‐dynamic cervico‐scapulothoracic strengthening/endurance exercises including pressure biofeedback immediate post treatment and probably improves pain, function and global perceived effect at long‐term follow‐up. Low grade evidence supports sustained natural apophyseal glides (SNAG) exercises.

For acute radiculopathy, low quality evidence suggests a small benefit for pain reduction at immediate post treatment with cervical stretch/strengthening/stabilization exercises.

Authors' conclusions

No high quality evidence was found, indicating that there is still uncertainty about the effectiveness of exercise for neck pain. Using specific strengthening exercises as a part of routine practice for chronic neck pain, cervicogenic headache and radiculopathy may be beneficial. Research showed the use of strengthening and endurance exercises for the cervico‐scapulothoracic and shoulder may be beneficial in reducing pain and improving function. However, when only stretching exercises were used no beneficial effects may be expected. Future research should explore optimal dosage.

Keywords: Adult; Female; Humans; Male; Physical Therapy Modalities; Acute Pain; Acute Pain/therapy; Chronic Pain; Chronic Pain/therapy; Headache; Headache/etiology; Headache/therapy; Manipulation, Chiropractic; Manipulation, Chiropractic/methods; Neck; Neck Pain; Neck Pain/etiology; Neck Pain/therapy; Pain Management; Pain Management/methods; Radiculopathy; Radiculopathy/therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Exercise for Neck Pain

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of exercise therapy on pain, disability, patient satisfaction, and quality of life among people with neck pain.

Background

Neck pain is common; it can limit a person's ability to participate in normal activities and is costly. Exercise therapy is a widely used treatment for neck pain. This review includes active exercises (including specific neck and shoulder exercises, stretching, strengthening, postural, breathing, cognitive, functional, eye‐fixation and proprioception exercises) prescribed or performed in the treatment of neck pain. Studies in which exercise therapy was given as part of a multidisciplinary treatment, multimodal treatment (along with other treatments such as manipulation or ultrasound), or exercises requiring application by a trained individual (such as hold‐relax techniques, rhythmic stabilization, and passive techniques) were excluded.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to May 2014. We found 27 trials (with a total of 2485 participants) examining whether exercise can help reduce neck pain and disability; improve function, global perceived effect, patient satisfaction and/or quality of life. In these trials, exercise was compared to either a placebo treatment, or no treatment (waiting list), or exercise combined with another intervention was compared with that same intervention (which could include manipulation, education/advice, acupuncture, massage, heat or medications). Twenty‐four of 27 trials evaluating neck pain reported on the duration of the disorder: 1 acute; 1 acute to chronic; 1 subacute; 4 subacute/chronic; and 16 chronic. One study reported on neck disorder with acute radiculopathy; two trials investigated subacute to chronic cervicogenic headache.

Key results

Results showed that exercise is safe, with temporary and benign side effects, although more than half of the trials did not report on adverse effects. An exercise classification system was used to ensure similarity between protocols when looking at the effects of different types of exercises. Some types of exercise did show an advantage over the other comparison groups. There appears to be a role for strengthening exercises in the treatment of chronic neck pain, cervicogenic headache and cervical radiculopathy if these exercises are focused on the neck, shoulder and shoulder blade region. Furthermore, the use of strengthening exercises, combined with endurance or stretching exercises has also been shown to be beneficial. There is some evidence to suggest the beneficial effects of specific exercises (e.g. sustained natural apophyseal glides) with cervicogenic headaches and mindfulness exercises (e.g. Qigong) for chronic mechanical neck pain. There appears to be minimal effect on neck pain and function when only stretching or endurance type exercises are used for the neck, shoulder and shoulder blade region.

Quality of the evidence

No high quality evidence was found, indicating that there is still uncertainty about the effectiveness of exercise for neck pain. Future research is likely to have an important impact on the effect estimate.There were a number of challenges with this review; for example, the number of participants in most trials was small, more than half of the included studies were either of low or very low quality and there was limited evidence on optimum dosage requirements.

Summary of findings

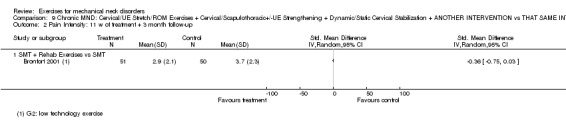

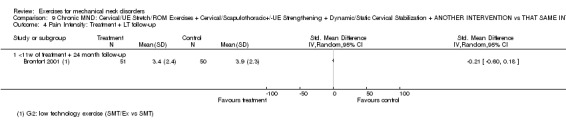

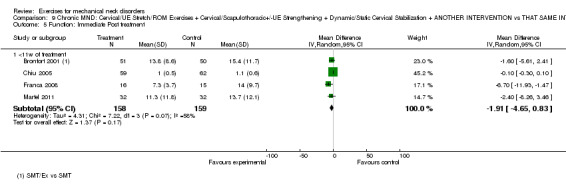

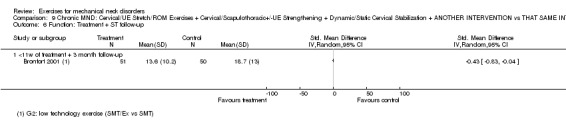

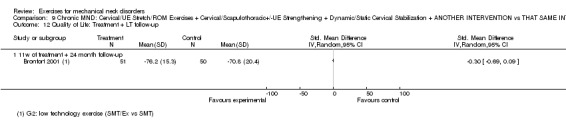

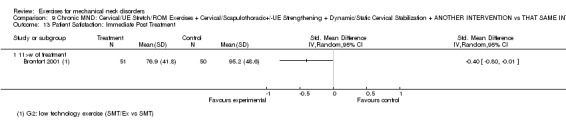

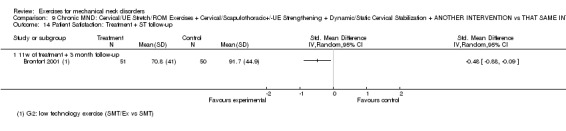

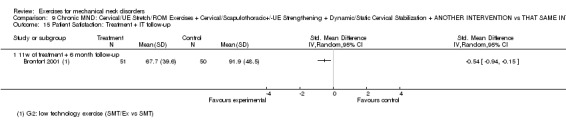

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Chronic MND: Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercises + Cervical/Scapulothoracic+/‐UE Strengthening + Dynamic/Static Cervical Stabilization + ANOTHER INTERVENTION compared to THAT SAME INTERVENTION.

| Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercises + Cervical/Scapulothoracic+/‐UE Strengthening + Dynamic/Static Cervical Stabilization + ANOTHER INTERVENTION compared to THAT SAME INTERVENTION for chronic mechanical neck disorders | |||

| Patient or population: patients with mechanical neck disorders Settings: ambulatory care clinic Intervention: Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercises + Cervical/Scapulothoracic+/‐UE Strengthening + Dynamic/Static Cervical Stabilization + ANOTHER INTERVENTION Comparison: THAT SAME INTERVENTION | |||

| Outcomes | Effects | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 10 worst pain (follow‐up: 6 months) |

Three trials showed a small reduction in pain. Pooled scores estimated using a mean difference of ‐0.67 (‐1.32 to ‐0.02) |

241 (3 studies: Bronfort 2011, Chiu 2005, Franca 2008) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Function: NDI 0 no disability to 50 maximum disability (follow‐up: 6 months) | Three trials showed a small to moderate improvement in function. Pooled scores estimated using a mean difference of ‐2.80 (‐6.36 to 0.76) |

241 (3 studies: Bronfort 2011, Chiu 2005, Franca 2008) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

|

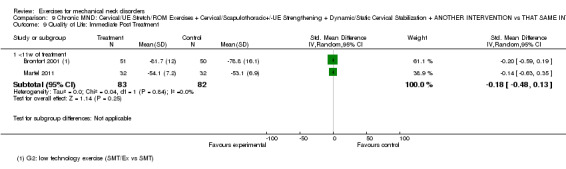

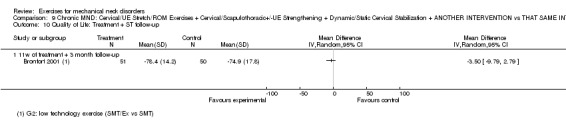

Quality of Life: SF‐36 (physical component) 0 worse to 100 better, SF‐12. (follow‐up: Immediate post treatment) |

Two trials showed no significant difference Pooled scores estimated using a standard mean difference of ‐0.18 (‐0.48 to 0.13) |

165 (2 studies: Bronfort 2001, Martel 2011) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 |

|

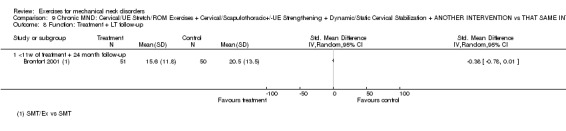

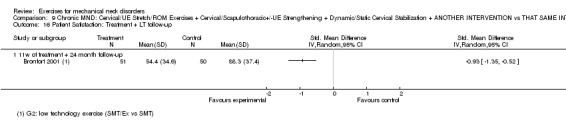

Patient Satisfaction: 1 to 7; completely satisfied to completely dissatisfied (follow‐up: 24 months) |

One trial showed moderate improvement in satisfaction Scores estimated using a standard mean difference of ‐0.93 (‐1.35 to ‐0.52) |

101 (1 study: Bronfort 2001) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate |

|

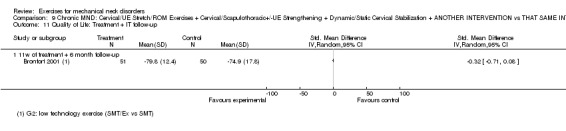

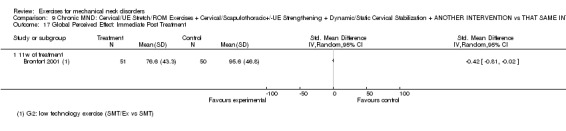

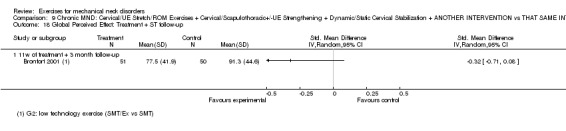

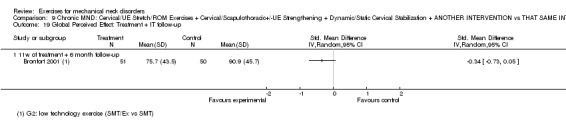

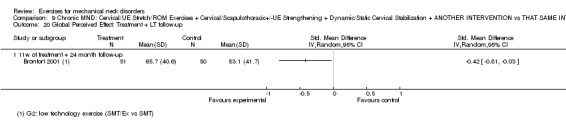

Global Perceived Effect: Patient‐ Rated Improvement 1 more improvement to 9 less improvement (follow‐up: 24 months) |

One trial showed a small to moderate improvement in global perceived effect Scores estimated using a standard mean difference of ‐0.42 (‐0.81 to ‐0.03) |

101 (1 study: Bronfort 2001) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate |

| Adverse Effects | One study reported increased neck or headache pain: Intervention group (n = 8), comparison group (n = 6); increased radicular pain intervention group (n = 1); severe thoracic pain comparison group (n = 1); all cases self‐limiting and no permanent injuries (Bronfort 2001). 3 trials reported no complications or serious adverse events (Chiu 2005, Franca 2008, Martel 2011) | ||

| Moderate quality evidence: (4 trials, 341 participants, Bronfort 2001; Chiu 2005; Franca 2008; Martel 2011) shows moderate pain relief and improved function up to long‐term follow‐up for combined cervical, scapulothoracic stretching and strengthening for chronic neck pain. A clinician may need to treat 6 to18 people to achieve this type of pain relief and 4 to 13 to achieve this functional benefit. Moderate quality evidence (one trial, 101 participants; Bronfort 2001) demonstrates patients are very satisfied with their care. Changes in quality of life are suggestive of benefit but not conclusive. Changes in global perceived effect measures indicate a difference immediately post treatment and at long‐term follow‐up. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Two of the pooled studies had high risk of bias scores (Franca 4/12 and Martel 5/12). That is, the studies met fewer than 6 of the 12 criteria, indicating high risk of bias.

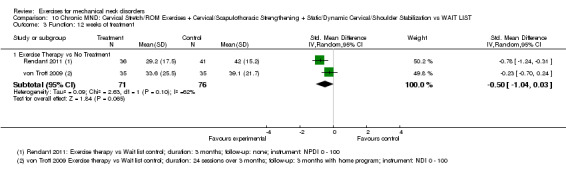

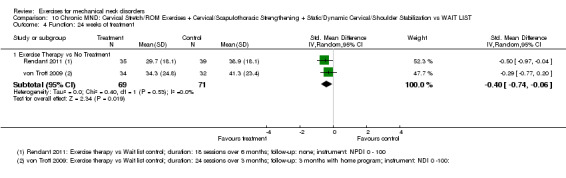

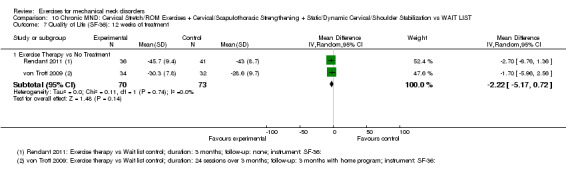

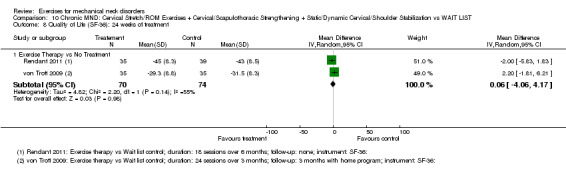

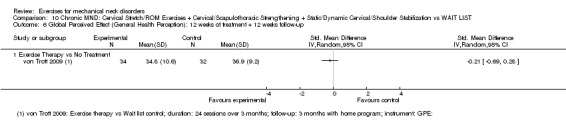

Summary of findings 2. Chronic MND: Cervical Stretch/ROM Exercises + Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening + Static/Dynamic Cervical/Shoulder Stabilization compared to WAIT LIST.

| Cervical Stretch/ROM Exercises + Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening + Static/Dynamic Cervical/Shoulder Stabilization compared to WAIT LIST for mechanical neck disorders | |||

| Patient or population: patients with chronic mechanical neck disorders Settings: residential community Intervention: Cervical Stretch/ROM Exercises + Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening + Static/Dynamic Cervical/Shoulder Stabilization Comparison: WAIT LIST | |||

| Outcomes | Effects | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

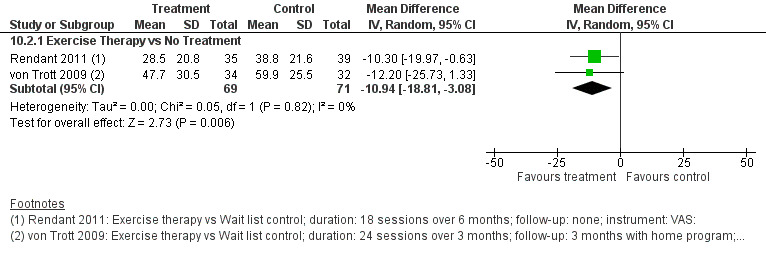

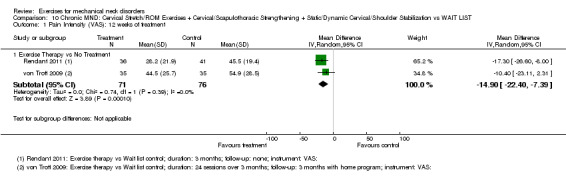

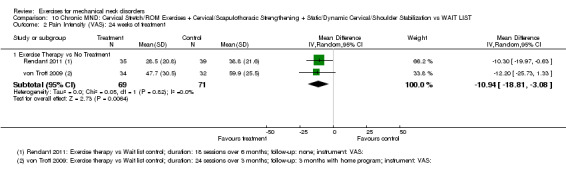

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain; (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment b. 24 weeks of treatment or 12 weeks of treatment+ 12 weeks follow‐up |

Two trials showed a medium reduction in pain. a. Pooled mean difference ‐14.90 (‐22.40 to ‐7.39) b. Pooled mean difference ‐10.94 (‐18.81 to ‐3.08) |

147 (2 studies: Rendant 2011, von Trott 2009) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 |

|

Function: NPDI or NDI 0 no disability to 100 maximum disability; (follow‐up: immediate post treatment)

a. 12 weeks of treatment b. 24 weeks of treatment or 12 weeks treatment + 12 weeks follow‐up |

Two trials showed a medium improvement in function. a. Pooled SMD ‐0.50 (‐1.04 to 0.03) b. Pooled SMD ‐0.40 (‐0.74 to ‐0.06) |

147 (2 studies: Rendant 2011, von Trott 2009) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 |

|

Quality of Life: SF‐36 (physical component) 0 worse to 100 better; (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment b. 24 weeks of treatment or 12 weeks treatment + 12 weeks follow‐up |

Two trials showed no significant difference in quality of life scores a. Pooled mean difference ‐2.22 (‐5.17 to 0.72) b. Pooled mean difference 0.06 (‐4.06 to 4.17) |

143 (2 studies: Rendant 2011, von Trott 2009) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 |

|

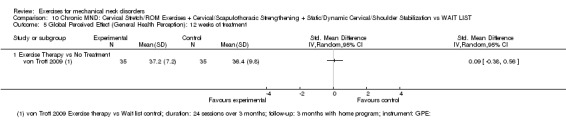

Global Perceived Effect: General Health Perception 0 worse to 100 better (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment b. 24 weeks of treatment |

One trial showed no significant difference in GPE. | 70 (1 study: von Trott 2009) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 |

| Adverse Effects | Reported by 18 patients in exercise group: muscle soreness (n = 15), myogelosis (n = 11), headaches (n = 5), vertigo (n = 2), change in mood (n = 1), worsening of neck pain (n = 1), worsening of tinnitus (n = 1) , nausea (n = 1), muscle tensions (n = 2) | ||

| Moderate quality evidence (two trials, 147 participants, von Trott 2009; Rendant 2011) shows cervical stretch/ROM exercises + cervical/scapulothoracic strengthening + static/dynamic cervical/shoulder stabilization probably has moderate benefit for pain and function, but not GPE and QoL at immediate post treatment and short‐term follow‐up. A clinician may need to treat four people to achieve moderate degree of pain relief and five to achieve moderate functional benefit in one patient. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 One of the studies (Rendant 2011) scored 6/12 on 'Risk of bias' assessment.That is, the study met 6 or fewer than 6 of the 12 criteria, indicating high risk of bias. 2 Small studies

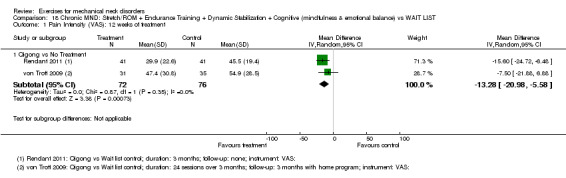

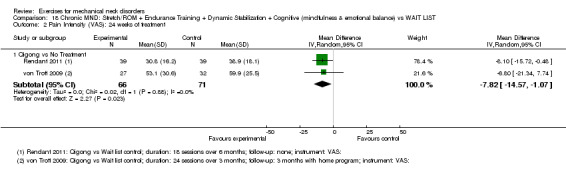

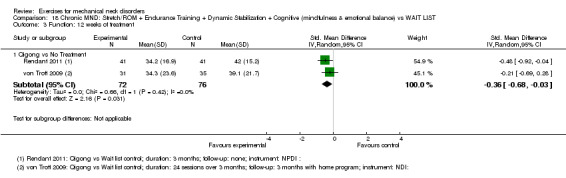

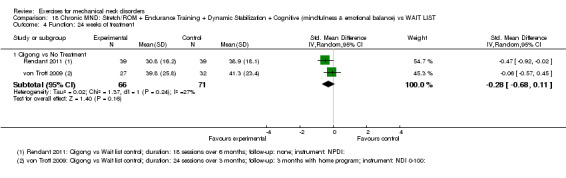

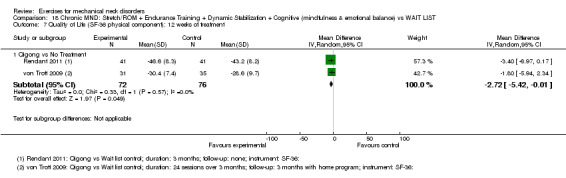

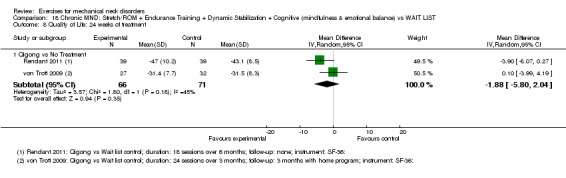

Summary of findings 3. Chronic MND: Qigong Stretch/ROM + Endurance Training + Dynamic Stabilization + Cognitive (mindfulness & emotional balance) compared to WAIT LIST.

| Stretch/ROM + Endurance Training + Dynamic Stabilization + Cognitive (mindfulness & emotional balance) compared to WAIT LIST for mechanical neck disorders | |||

| Patient or population: patients with chronic mechanical neck disorders Settings: residential community Intervention: Stretch/ROM + Endurance Training + Dynamic Stabilization + Cognitive (mindfulness & emotional balance) Comparison: WAIT LIST | |||

| Outcomes | Effects | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment b. 24 weeks of treatment or 12 treatments + 12 weeks follow‐up |

Two trials showed a moderate reduction in pain Pooled scores estimated using a a. Mean difference of ‐13.28 (‐20.98 to ‐5.58) b. Mean difference of ‐7.82 (‐14.57 to ‐1.07) |

148 (2 studies: Rendant 2011, von Trott 2009) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

|

Function: NPDI 0 no disability to 100 maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment b. 24 weeks of treatment or 12 weeks treatment + 12 weeks follow‐up |

Two trials showed a small improvement in function Pooled scores estimated using a a. Standard mean difference of ‐0.36 (‐0.68 to ‐0.03) b. Standard mean difference of ‐0.28 (‐0.68 to 0.11) |

148 (2 studies: Rendant 2011, von Trott 2009) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

|

Quality of Life: SF‐36 (physical component) 0 worse to 100 better (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment b. 24 weeks of treatment or 12 weeks treatment + 12 weeks follow‐up |

Two trials showed little to no difference in quality of life Pooled scores estimated using a a. Mean difference of ‐2.72 (‐5.42 to ‐0.01) b. Mean difference of ‐1.88 (‐5.80 to 2.04) |

148 (2 studies: Rendant 2011, von Trott 2009) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝1 moderate |

| Global Perceived Effect: General Health Perception 0 worse to 100 better (follow‐up immediate post treatment and short‐term) | One trial showed no significant difference in GPE. | 70 (1 study: von Trott 2009) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2 |

| Adverse Effects | Reported by 23 patients in qigong group including: muscle soreness (n = 17), myogelosis (n = 12), vertigo (n = 10), other pain (n = 4), headache (n = 3), thirst (n = 1), engorged hands (n = 1), twinge in the neck (n = 1), urinary urgency (n = 1), bursitis of left shoulder (n = 1), nausea (n = 2), muscle tension (n = 1) | ||

| Moderate quality evidence: (2 trials, 148 participants, Rendant 2011; von Trott 2009) shows Qigong exercises (Dantian Qigong) may improve pain and function slightly when compared with a wait list control at immediate and short‐term follow‐up. It may have little or no benefit at immediate and short‐term follow‐up on quality of life and global perceived effect. A clinician may need to treat four to six people to achieve this type of pain relief, five to eight people to achieve this functional benefit, and seven to 10 people for this improvement in quality of life. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 One included study (Rendant 2011) scored 6/12 on risk of bias assessment.That is, the study met 6 or fewer than 6 of the 12 criteria, indicating high risk of bias. 2 Small studies.

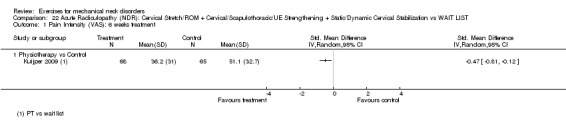

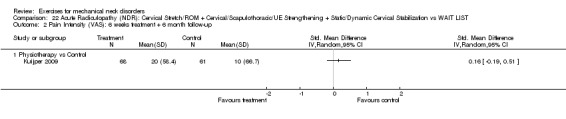

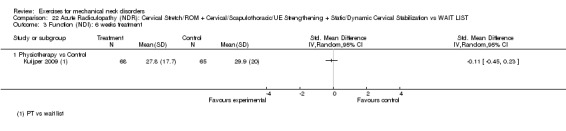

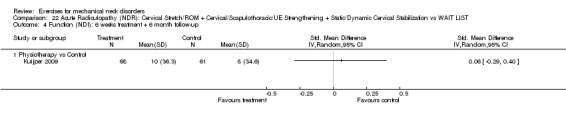

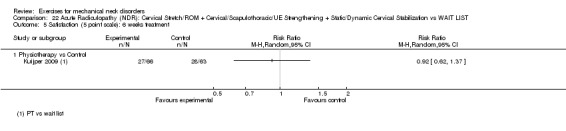

Summary of findings 4. Acute Radiculopathy: Cervical Stretch/ROM + Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Strengthening + Static/Dynamic Cervical Stabilization vs WAIT LIST.

| Cervical Stretch/ROM + Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Strengthening + Static/Dynamic Cervical Stabilization compared with wait list for acute radiculopathy | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with acute radiculopathy Settings: Three hospitals in Netherlands Intervention: Cervical Stretch/ROM + Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Strengthening + Static/Dynamic Cervical Stabilization Comparison: Wait list | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 10 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 6 months |

One trial showed a small reduction in pain immediately post treatment and no benefit at 6 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.47 (‐0.81 to ‐0.12) post intervention b. Standard mean difference are 0.16 (‐0.19 to 0.51) at 6 months follow‐up. |

133 participants (1 study: Kuijper 2009) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝1,2 low |

|

Function: NDI 0 no disability to 50 maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 6 months |

One trial showed a small reduction in functional disability immediately post treatment and no benefit at 6 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.11 (‐0.45 to 0.23) post intervention. b. Standard mean difference are 0.06 (‐0.29 to 0.40) at 6 month follow‐up. |

133 participants (1 study: Kuijper 2009) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝1,2 low |

|

Patient Satisfaction: 5‐point scale, 1 to 5; very satisfied to unsatisfied (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment |

a. One trial showed no difference in patient satisfaction immediately post treatment. relative risk ratio are 0.92 (0.62 to 1.37) post intervention. | 129 participants (1 study: Kuijper 2009) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝1,2 low |

| Adverse Effects | Not reported | ||

| Low quality evidence: (one trial, 133 participants, Kuijper 2009) Cervical Stretch/ROM + Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Strengthening + Static/Dynamic Cervical Stabilization may improve pain slightly, but may make no difference in function and patient satisfaction when compared immediately post treatment with a control for acute cervical radiculopathy. However, there may be no difference in pain and functional improvement at intermediate‐term follow‐up. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 One included study (Kuijper 2009) scored 4/12 on risk of bias assessment.That is, the study met 6 or fewer than 6 of the 12 criteria, indicating high risk of bias. 2 Small study.

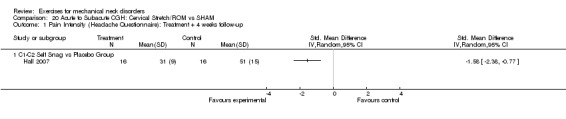

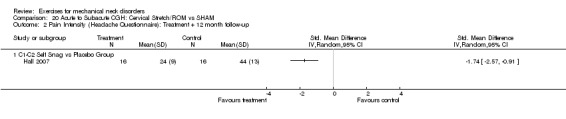

Summary of findings 5. Acute to subacute CGH: Cervical stretch/ROM vs SHAM.

| Cervical stretch/ROM vs SHAM compared with SHAM intervention for subAcute CGH | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with subAcute cervicogenic headache (CGH) Settings: Physiotherapy Private Practice Intervention: Cervical stretch/ROM Comparison: SHAM INTERVENTION | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment ) a. 4 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed a small reduction in pain a. Standard mean difference are ‐1.58 (‐2.38 to ‐0.77) at 4 weeks b. Standard mean difference are ‐1.74 (‐2.57 to ‐0.91) at 12 months. |

32 (1 study: Hall 2007) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ||

| Low quality evidence: (one trial, 32 participants, Hall 2007 ) shows Cervical stretch/ROM may improve a large amount for pain reduction at short‐ and long‐term follow‐up with the use of C1 to C2 self‐SNAG exercises when compared with a sham for (sub)acute cervicogenic headache. A clinician may need to treat three people to achieve this type of long‐term pain relief. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Percision: Small study (n=16 per arm).

2 Reporting bias: due to trial size and single outcome, future research is likely to influence the direction of reported effect. Replication in a second trial is needed.

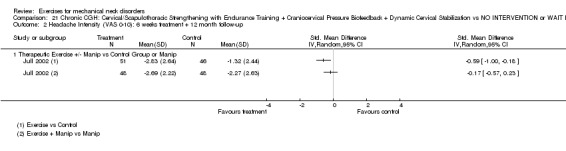

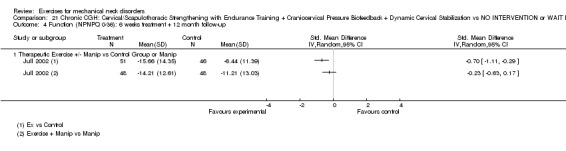

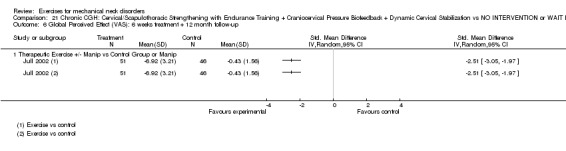

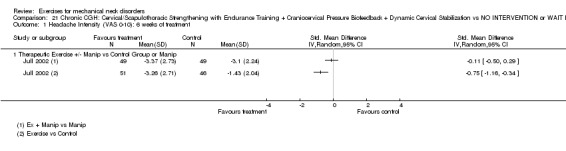

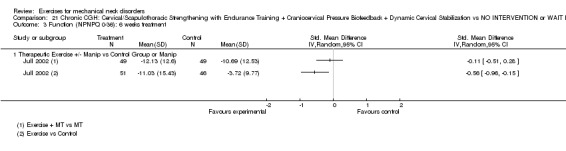

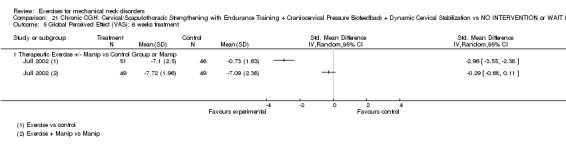

Summary of findings 6. Chronic CGH: Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening with Endurance Training + Craniocervical Pressure Biofeedback + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization vs NO INTERVENTION.

| Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening with Endurance Training + Craniocervical Pressure Biofeedback + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization compared with NO INTERVENTION for Chronic CGH | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic CGH Settings: multiple trial centres Intervention: Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening with Endurance Training + Craniocervical Pressure Biofeedback + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization Comparison: NO INTERVENTION | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 10 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed a large reduction in pain at 6 weeks and 12 months follow up. a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.75 (‐1.16 to ‐0.34) at 6 weeks b. Standard mean difference are ‐0.59 (‐1.00 to ‐0.18) at 12 months follow‐up. |

97 (1 study: Jull 2002) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

|

Function: NPNPQ 0% no disability to 100% maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed a moderate reduction in functional disability a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.56 (‐0.96 to ‐0.15) at 6 weeks b. Standard mean difference are ‐0.70 (‐1.11 to 0.29) at 12 months follow‐up. |

97 (1 study: Jull 2002) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

|

Global Perceived Effect: VAS 0 to 100 (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed a large benefit in global perceived effect a. Standard mean difference are ‐2.96 (‐3.55 to ‐2.38) at 6 weeks. b. Standard mean difference are ‐2.51 (‐3.05 to ‐1.97) at 12 months follow‐up. |

97 (1 study: Jull 2002) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Adverse effects | Minor and temporary adverse effects were noted: 6.7% of headaches were provoked by treatment | ||

| Moderate quality evidence: (one trial, 97 participants, Jull 2002) shows cervicoscapular strengthening and endurance exercises including pressure biofeedback probably improves pain, function and global perceived effect for chronic cervicogenic headaches at long term follow‐up when compared to no treatment. A clinician may need to treat six people to achieve this type of pain relief and functional benefit in one patient. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Percision: Although small study, consistent findings are noted across multiple outcomes at long term follow‐up.

Summary of findings 7. Chronic CGH: Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening with Endurance Training + Craniocervical Pressure Biofeedback + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization + Manual Therapy vs Manual Therapy.

| Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening with Endurance Training + Craniocervical Pressure Biofeedback + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization + Manual Therapy compared with Manual Therapy for Chronic CGH | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with Chronic CGH Settings: multiple trial centres Intervention: Cervical/Scapulothoracic Strengthening with Endurance Training + Craniocervical Pressure Biofeedback + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization + Manual Therapy Comparison: MANUAL THERAPY | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: 6 weeks treatment VAS 0 no pain to 10 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed a small reduction in pain a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.11 (‐0.50 to 0.29) at 6 weeks b. Standard mean difference are ‐0.17 (‐0.57 to 0.23) at 12 months follow‐up. |

96 (1 study: Jull 2002) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

|

Function: NPNPQ 0% no disability to 100% maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed a small reduction in functional disability a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.11 (‐0.51 to 0.28) at 6 weeks b. Standard mean difference are ‐0.23 (‐0.63 to 0.17) at 12 months follow‐up. |

96 (1 study: Jull 2002) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

|

Global Perceived Effect: VAS 0 to 100 (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed a small benefit in global perceived effect a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.29 (‐0.68 to 0.11) at 6 weeks b. Standard mean difference ‐0.30 (‐0.70 to 0.10) at 12 months follow‐up. |

96 (1 study: Jull 2002) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Adverse effects | Minor and temporary adverse effects were noted: 6.7% of headaches were provoked by treatment | ||

| Moderate quality evidence (one trial, 96 participants, Jull 2002) shows when exercise combined with manual therapy contrasted with manual therapy alone there is probably no difference in pain, function and global perceived effect for chronic cervicogenic headaches at long‐term follow‐up. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Percision: Although small study, consistent findings are noted across multiple outcomes at long term follow‐up.

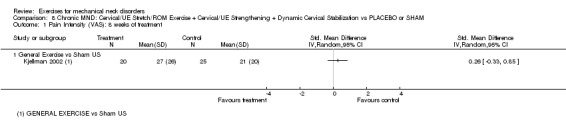

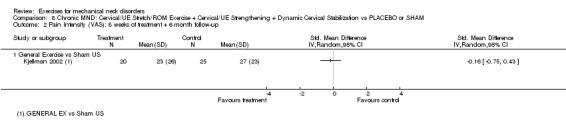

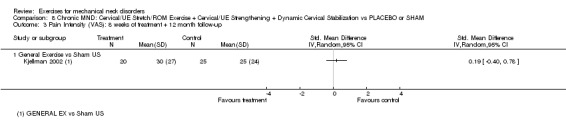

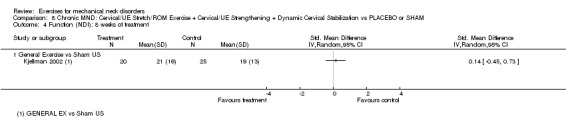

Summary of findings 8. Chronic MND: Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercise + Cervical/UE Strengthening + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization vs PLACEBO or SHAM.

| Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercise + Cervical/UE Strengthening + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization compared with PLACEBO or SHAM for Chronic MND | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic MND Settings: Primary care physical therapy and private physical therapy practices Intervention: Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercise + Cervical/UE Strengthening + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization Comparison: PLACEBO or SHAM | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 2 months of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 6 months c. 12 months |

One trial showed no difference in pain immediately post intervention and at 6 and 12 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference 0.26 (‐0.33 to 0.85) immediately 2 months post intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.16 (‐0.75 to 0.43) at 6 months follow‐up. c. Standard mean difference ‐0.19 (‐0.40 to 0.78) at 12 months follow‐up. |

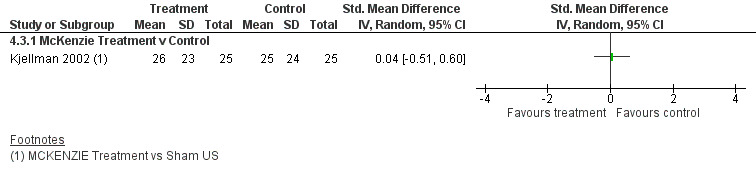

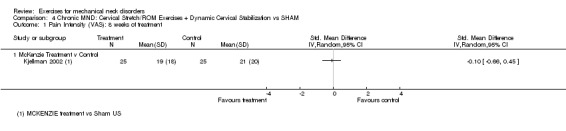

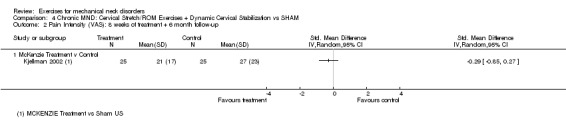

77 (1 study: Kjellman 2002) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

|

Function: 2 months treatment NDI 0 no disability to 50 maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 2 months of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment ) b. 6 months c. 12 months |

One trial showed no difference in function immediately post intervention and at 6 and 12 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference are 0.14 (‐0.45 to 0.73) immediately post 2 months intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.06 (‐0.66 to 0.53) at 6 months follow‐up. c. Standard mean difference 0.12 (‐0.47 to 0.72) at 12 months follow‐up. |

77 (1 study: Kjellman 2002) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ||

| Low quality evidence: (One trial, 77 participants, Kjellman 2002) No difference for pain relief and function immediately post intervention, at 6 and 12 months follow‐up using Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercise + Cervical/UE Strengthening + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization for chronic MND. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 One of the studies (Kjellman 2002)) scored 5/12 on 'Risk of bias' assessment.That is, the study met 6 or fewer than 6 of the 12 criteria, indicating high risk of bias. 2 Small studies

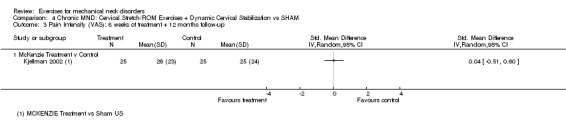

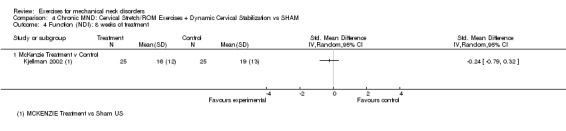

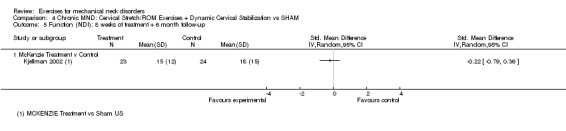

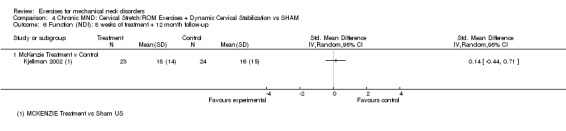

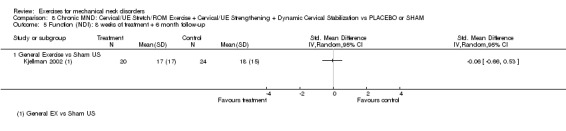

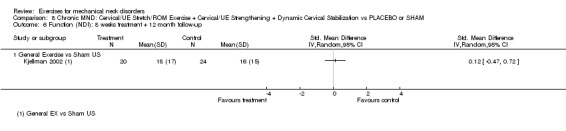

Summary of findings 9. Chronic MND: Cervical Stretch/ROM Exercises + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization vs SHAM.

| Cervical Stretch/ROM Exercise + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization compared with SHAM for Chronic MND | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic MND Settings: Primary care physical therapy and private physical therapy practices Intervention: Cervical/UE Stretch/ROM Exercise + Cervical/UE Strengthening + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization Comparison: PLACEBO or SHAM | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 2 months of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 6 months c. 12 months |

One trial showed no difference in pain immediately post intervention and at 6 and 12 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.10 (‐0.66 to 0.45) immediately post 2 months intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.29 (‐0.85 to 0.27) at 6 months follow‐up. c. Standard mean difference 0.04 (‐0.51 to 0.60) at 12 months follow‐up. |

50 (1 study: Kjellman 2002) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

|

Function: NDI 0 no disability to 50 maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 2 months of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment ) b. 6 months c. 12 months |

One trial showed no difference in function immediately post intervention and at 6 and 12 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference are ‐0.24 (‐0.79 to 0.32) immediately post 2 month intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.22 (‐0.79 to 0.36) at 6 months follow‐up c. Standard mean difference 0.14 (‐0.44 to 0.71) at 12 months follow‐up. |

50 (1 study: Kjellman 2002) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ||

| Low quality evidence: (One trial, 50 participants, Kjellman 2002) No difference for pain relief and function immediately post intervention, at 6 and 12 month follow‐up using Cervical Stretch/ROM Exercise + Dynamic Cervical Stabilization for chronic MND. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 One of the studies (Kjellman 2002) scored 5/12 on 'Risk of bias' assessment.That is, the study met 6 or fewer than 6 of the 12 criteria, indicating high risk of bias. 2 Small studies

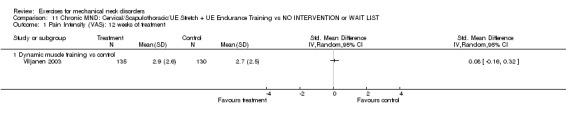

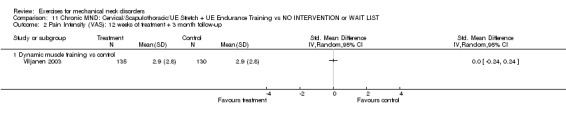

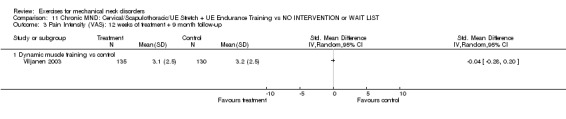

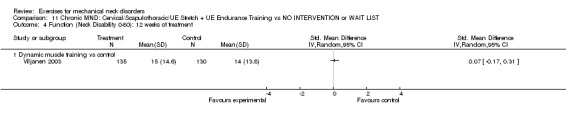

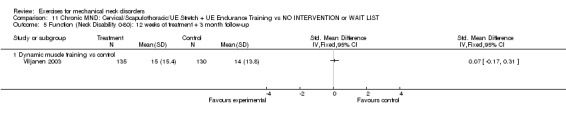

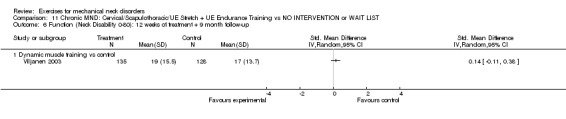

Summary of findings 10. Chronic MND: Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Stretch + UE Endurance Training vs NO INTERVENTION or WAIT LIST.

| Chronic MND: Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Stretch + UE Endurance Training compared with NO INTERVENTION or WAIT LIST for chronic MND | ||||

|

Patient or population: patients with chronic MND Settings: office workers Intervention: Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Stretch + UE Endurance Training Comparison: NO INTERVENTION or WAIT LIST |

||||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

|

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 3 months c. 9 months |

One trial showed no difference in pain immediately post intervention and at 3 and 9 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference are 0.08 (‐0.16 to 0.32) immediately post 12 weeks intervention. b. Standard mean difference 0.00 (‐0.24 to 0.24) at 3 months follow‐up. c. Standard mean difference ‐0.04 (‐0.28 to 0.20) at 9 months follow‐up. |

393 (1 study: Viljanen 2003) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

|

Function: NDI 0 no disability to 50 maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 12 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 3 months c. 9 months |

One trial showed no difference in function immediately post intervention and at 3 and 9 months follow up. a. Standard mean difference 0.07 (‐0.17 to 0.31) immediately post 12 weeks intervention. b. Standard mean difference 0.07 (‐0.17 to 0.31) at 3 months follow‐up. c. Standard mean difference 0.14 (‐0.11 to 0.38) at 9 months follow‐up. |

393 (1 study: Viljanen 2003) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | |||

| Moderate quality evidence: (one trial, 393 participants, Viljanen 2003) Little to no difference for pain relief and function immediately post intervention, at 3 and 9 months follow‐up using Cervical/Scapulothoracic/UE Stretch + UE Endurance Training for chronic MND. | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

1 Percision: high drop out rate (14%); reason for dropout not described.

Summary of findings 11. Acute to Chronic MND: Scapulothoracic/UE Endurance Training vs CONTROL.

| Scapulothoracic/UE Endurance Training compared with CONTROL for (sub)Acute/Chroninc MND | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with Acute to Chronic MND Settings: two large withe collar organizations Intervention: Scapulothoracic/UE Endurance Training Comparison: CONTROL | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

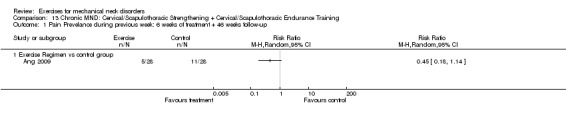

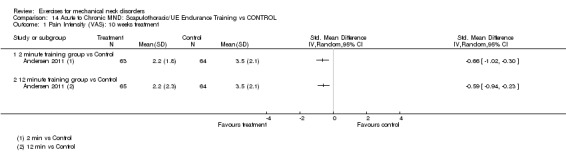

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 10 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post 10 weeks treatment) a. 2‐minute training group b. 12‐minute training group |

One trial showed moderate pain relief immediately post intervention. a. Standard mean difference for the 2 minute training group ‐0.66 (‐1.02 to ‐0.30). b. Standard mean difference for the 12 minute training group ‐0.59 (‐0.94 to ‐0.23). |

198 (1 study: Andersen 2011) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 |

| Adverse effects | Reported worsening of neck muscle tension during and/or in the days after training (2‐minute n = 1, 12‐minute n = 4), shoulder joint pain during training (2‐minute n = 1, 12‐minute n = 4), pain in the upper arm during training (2‐minute n = 1, 12‐minute n = 1), pain of the forearm/wrist during training (12‐minute n = 2), worsening of headache after training (2‐minute n = 1, 12‐minute n = 1). No long‐lasting or major complications resulted from the training program. | ||

| Moderate quality evidence: (one trial, 198 participants, Andersen 2011) Moderate benefit for pain relief immediately post intervention using Scapulothoracic/UE Endurance Training for (sub)Acute/Chronic MND. A clinician may need to treat four people to achieve this type of pain relief. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Percision: small sample (n = 63 or 64 per Arm) measured at Immediate post treatment.

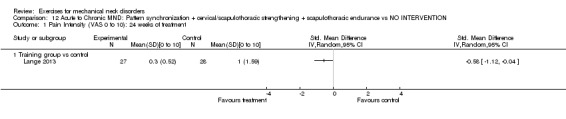

Summary of findings 12. Subacute to Chronic WAD: Trunk/Extremity Stretch/ROM + Trunk/Extremity Strengthening + Trunk/Extremity Endurance Training + Pattern/Synchronization: Coordination + Cardiovascular/Aerobic + Cognitive (CBT) + ANOTHER TREATMENT vs THAT SAME OTHER TREATMENT.

| Trunk/Extremity Stretch/ROM + Trunk/Extremity Strengthening + Trunk/Extremity Endurance Training + Pattern/Synchronization: Coordination + Cardiovascular/Aerobic + Cognitive (CBT) + ANOTHER TREATMENT compared with THAT SAME OTHER TREATMENT for Subacute/chronic WAD | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with subacute/chronic WAD Settings: two physiotherapy clinics Intervention: Trunk/Extremity Stretch/ROM + Trunk/Extremity Strengthening + Trunk/Extremity Endurance Training + Pattern/Synchronization: Coordination + Cardiovascular/Aerobic + Cognitive (CBT) + ANOTHER TREATMENT Comparison: THAT SAME OTHER TREATMENT | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

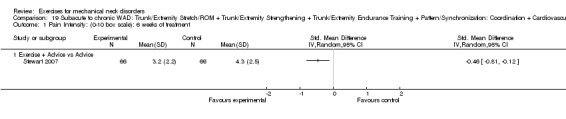

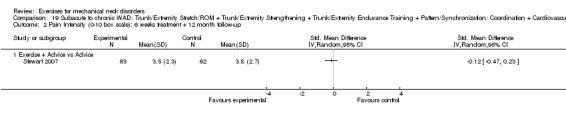

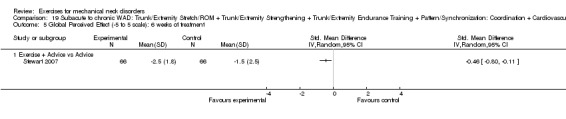

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 10 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed small pain relief immediately post intervention and no difference at 12 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference ‐0.46 (‐0.81 to ‐0.12) immediately post 6 weeks intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.12 (‐0.47 to 0.23) at 12 months follow‐up. |

132 (1 study: Stewart 2007) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

|

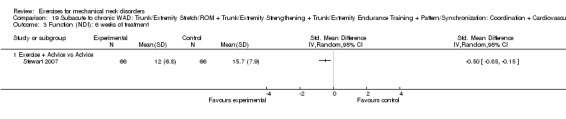

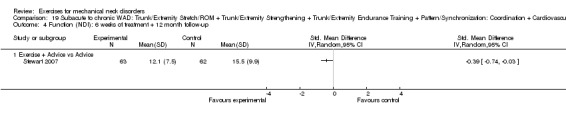

Function: NDI 0 no disability to 50 maximum disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up period after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed small benefit in function immediately post intervention and at 12 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference ‐0.50 (‐0.85 to ‐0.15) immediately post 6 weeks intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.39 (‐0.74 to ‐0.03) at 12 months follow‐up. |

132 (1 study: Stewart 2007) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

|

Global perceived effect: ‐5 to 5 scale; vastly worse to completely recovered (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed small benefit in global perceived effect immediately post intervention and no difference at 12 months follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference ‐0.46 (‐0.80 to ‐0.11) immediately post 6 weeks intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.18 (‐0.54 to 0.17) at 12 months follow‐up. |

132 (1 study: Stewart 2007) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

|

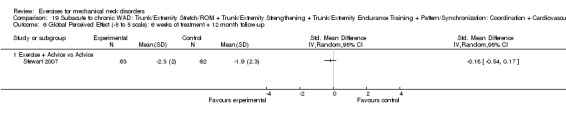

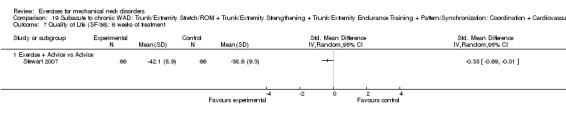

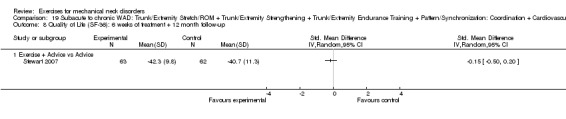

Quality of Life: SF‐36 0 high disability to 100 no disability (follow‐up: immediate post treatment) a. 6 weeks of treatment (follow‐up after treatment) b. 12 months |

One trial showed small benefit in global perceived effect immediately post intervention and no difference at 12 month follow‐up. a. Standard mean difference ‐0.35 (‐0.69 to ‐0.01) immediately post 6 weeks intervention. b. Standard mean difference ‐0.15 (‐0.50 to 0.20) at 12 month follow‐up. |

132 (1 study: Stewart 2007) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 |

| Adverse effects | Reported; The main complaint in this group was muscle pain with exercise (3) followed by knee pain (2) and lumbar spine pain (2). | ||

| Low quality evidence: (one trial, 132 participants, Stewart 2007) Small benefit for pain relief, function, global perceived effect and quality of life immediately post treatment and small benefit at 12 month follow up for function using Trunk/Extremity Stretch/ROM + Trunk/Extremity Strengthening + Trunk/Extremity Endurance Training + Pattern/Synchronization: Coordination + Cardiovascular/Aerobic + Cognitive (CBT) + ANOTHER TREATMENT for Subacute/chronic WAD. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 One of the studies (Stewart 2007) scored 6/12 on 'Risk of bias' assessment.That is, the study met 6 or fewer than 6 of the 12 criteria, indicating high risk of bias. 2 Small studies

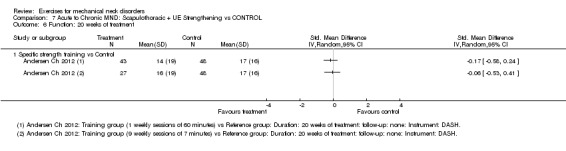

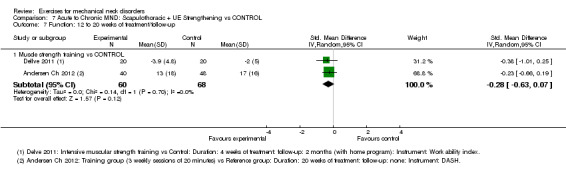

Summary of findings 13. Acute to Chronic MND: Scapulothoracic + UE Strengthening vs CONTROL.

| Scapulothoracic + UE Strengthening compared with CONTROL for (sub)Acute/Chronic MND | |||

|

Patient or population: patients with Acute to Chronic MND Settings: Seven workplaces Intervention: Scapulothoracic + UE Strengthening Comparison: CONTROL | |||

| Outcomes | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

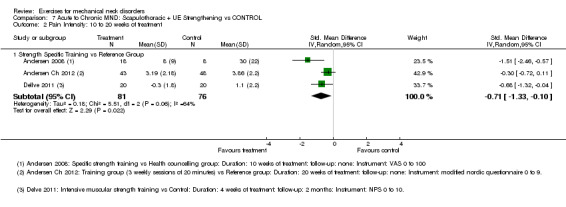

| Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post 10 to 20 weeks of treatment) | Three trials showed a moderate reduction in pain. Pooled scores estimated using a standard mean difference ‐0.71 (‐1.33 to ‐0.10). | 157 (3 studies: Andesen 2008, Andersen CH 2012, Dellve 2011) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate |

|

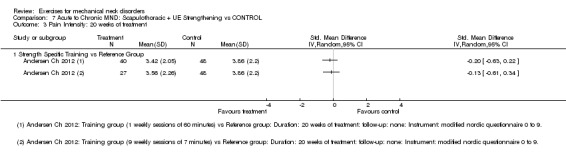

Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post 20 weeks of treatment) a. 1 weekly session b. 9 weekly sessions |

One trial (two comparisons) showed no difference in pain relief immediately post intervention. a. One weekly session of 60 minutes, scores using a standard mean difference ‐0.20 (‐0.63 to 0.22). b. Nine weekly sessions of seven minutes, scores using a standard mean difference ‐0.13 (‐0.61 to 0.34). |

163 (1 study: three groups, Andersen CH 2012) |

⊝⊝⊝⊝ very low1 |

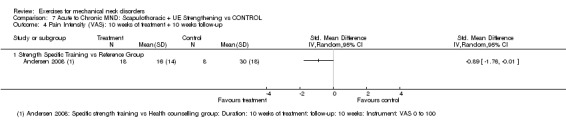

| Pain Intensity: VAS 0 no pain to 100 worst pain (follow‐up: immediate post 10 weeks of treatment) | One trial showed moderate reduction in pain 10 weeks post intervention. Scores using a standard mean difference ‐0.89 (‐1.76 to ‐0.01) at 10 week follow‐up. | 26 (1 study: Andersen 2008) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low |

|

Function: DASH 20% no difficulty to 100% fully unable (follow‐up: immediate post 20 weeks of treatment). a. 1 weekly session b. 9 weekly sessions |

One trial showed no difference in function immediately post intervention. a. Standard mean difference ‐0.17 (‐0.58 to 0.24) immediately post intervention for one weekly session of 60 minutes b. Standard mean difference ‐0.06 (‐0.53 to 0.41) for nine weekly sessions of seven minutes. |

163 (1 study: Andersen CH 2012) |

⊝⊝⊝⊝ very low1 |

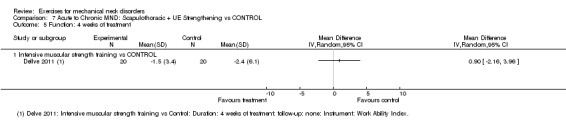

| Work ability index: 7 poor ability to 49 excellent ability treatment (follow‐up: immediate post 20 weeks treatment) | One trial showed a small improvement in work ability immediately post intervention. Standard mean difference ‐0.23 (‐0.66 to 0.19) immediately post 20 weeks intervention. | 88 (1 study: Dellve 2011) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ low |

| Adverse effects | Not reported | ||

| Moderate quality evidence: (3 trials, 157 participants, Andersen 2008, Andersen Ch 2012, Dellve 2011) that scapulothoracic and upper extremity strength training probably improves pain. It probably functional outcomes when compared to control for chronic mechanical neck pain immediately post treatment (10 or 20 week interventions). However low quality evidence suggests that scapulothoracic and upper extremity strength training may improve pain slightly. | |||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1 Design: 0, Limitations: ‐1, Inconsistency: 0, Indirectness: 0, Imprecision: ‐1, Other: ‐1 subgroup analysis.

Background

Description of the condition

Neck disorders are common (Hogg‐Johnson 2008; Hoy 2014), painful, and limit function in the general population (Carroll 2008a, Haldeman 2010,), workers (Côté 2008) and people with whiplash associated disorders (WAD) (Carroll 2008b; Buitenhuis 2009). The global point prevalence of neck pain was estimated to be 4.9% in 2010 (Hoy 2014). In the United States, 15.1% of adults state having had neck pain within the previous three months (NCHS 2013).

In 2005, the mean medical expenditure amongst Americans with spine problems was estimated to be $6096USD per individual annually compared with $3516USD amongst those without spine problems (Martin 2008). Côté 2008 reported 3% to 11% of claimants in the work force were sufficiently disabled to lose time from work each year. Direct and indirect costs are substantive (Martin 2008).

Description of the intervention

We adopted the Therapeutic Exercise Intervention Model to sub‐classify exercise (Sahrmann 2002). This model is based on the elements of movement system. Sahrmann 2002 originally described movement as a system made up of five elements. Hall 2005 further developed this concept into a three dimensional model. The elements of movement system intersect with two other axes ‐ activity and dosage. After determining which element of the movement system needs to be addressed to restore function, the activity or technique to achieve the functional goal is chosen. The dosage parameters are modified according to the tissues involved and the principles of tissue healing. A brief description of each element follows.

1.Support Element: An exercise categorized under this element would affect the functional status of the cardiac, pulmonary and metabolic systems (e.g. aerobic endurance activities).

2. Base Element: Exercises categorized under base element would affect the functional status of the muscular and skeletal systems and is commonly linked to the biomechanical element. This element provides the basis for movement as follows:

extensibility/stiffness properties of muscle, fascia and periarticular tissues for range of motion and stretching exercises,

mobility of neuromeningeal tissue for neural mobilization exercises,

force or torque capability of muscles and the related muscle length‐tension properties for strengthening exercises, and

endurance of muscle also involved in strengthening for endurance‐strength training.

3.Modulator Element: Exercises under this element relate to motor control for neuromuscular reeducation as follows:

patterns and synchronization of muscle recruitment, and

feed‐forward or feedback systems using verbal, visual, tactile and other proprioceptive input to the patient.

4. Biomechanical Element: This element is an interface between the motor control associated with the modulator element and musculoskeletal function associated with the base element. Components of the biomechanical element include:

static stabilization forces involved in alignment and muscle recruitment, and

dynamic stabilization forces involved in arthrokinetics, osteokinetics and kinematics.

5. Cognitive or Affective Element: Exercises in this category affect the functional status of the psychological system as it is related to movement as follows:

the cognitive ability to learn,

patient and caregiver compliance,

motivation, and

emotional status.

How the intervention might work

Exercise has both physical and mental benefits through its effects on numerous systems such as the cardiovascular system; immune system; brain function; sleep; mood; and the musculoskeletal system (Abernethy 2013). Exercise can result in the following.

Increase flexibility and mobility of structures; improve muscle strength and endurance; increase tensile strength of ligaments and capsule; amplify strength and prevent injury of tendons and cartilage; and is also important for repair of these tissues.

Improve cardiovascular function resulting in less chance of developing heart conditions, strokes, or high blood pressure.

Relieve stress, anxiety and depression; improve mood; and increase self‐esteem and weight management by producing positive biochemical changes in the body and brain. Endorphins released post exercise act as a natural pain reliever and antidepressant in the body.

Reduce the risk of premature mortality; improve functional capacity and help older adults maintain independence. Exercise increases circulation throughout the spine and supporting structures, which is crucial to promote healing.

Improve quality and duration of sleep and help sleep disorders such as insomnia.

Enhance cognitive function in older adults through physical activity and aerobic exercise.

Positively benefit the human immune system if done in moderation.

Central to these benefits are the stages of change, encompassing the health belief and cognitive behavior models, used to help patients make the lifestyle changes necessary for successful adherence to exercise, maintain new behaviours over time and address anticipated relapses (Zimmerman 2000). Helping patients change behavior is an important role for all clinicians.

Why it is important to do this review

In our last update on exercise therapy, we found low to moderate quality evidence of pain relief benefit for combined cervical, scapulothoracic stretching and strengthening for chronic neck pain in the short and long term. The relative benefit of other types of exercise was not clear (Kay 2012). Since then, five other reviews have found primarily very low to low grade evidence as follows: 1) Stretching and strengthening for chronic neck pain (Bertozzi 2013; Southerst 2014; Vincent 2013), 2) Strengthening, endurance and modular element (Bronfort 2009; Racicki 2012) for chronic cervicogenic headache, 3) Neuromuscular exercises (proprioception/eye‐neck co‐ordination) (Leaver 2010; Teasell 2010a) for subacute and chronic WAD, 4) Stretching and range of motion (ROM) exercises (Leaver 2010) for non‐specific neck pain, 5) Stretching, strengthening, endurance training, balance/co‐ordination, cardio and cognitive/affective elements (Leaver 2010; Lee 2009; Salt 2011; Southerst 2014; Teasell 2010c) for chronic neck pain, 6) Qigong exercises (; Lee 2009; Southerst 2014) for chronic neck pain, 7) Supervised exercise (Teasell 2010c) for chronic WAD, and 8) Strengthening neck exercises (Bertozzi 2013; Southerst 2014) for chronic neck pain.

In contrast, reviews found low grade evidence for no beneficial effect on pain as follows: 1) Stretching and strengthening (Salt 2011; Southerst 2014) for radiculopathy, 2) General fitness training (Bertozzi 2013; Kay 2012) for acute to chronic neck pain, and 3) Stretching and endurance training in chronic neck pain (Bertozzi 2013; Kay 2012). There may be more than one way to summarize the results but few used the grade system. The GRADE approach considers a number of additional factors (adverse events, costs, temporality, plausibility, dose response, strength of association, and clinical applicability) to place the results into a larger context (Guyatt 2006).

Many previous reviews looked at multimodal approaches such as manual therapy and exercise (Bronfort 2009; Clar 2014; Miller 2010; Schroeder 2013) but our focus is on exercise alone.

A number of these reviews included studies that were not clearly categorized; they also included studies that were not single intervention trials. The results limited our ability to understand the comparative effectiveness of exercise interventions for the management of neck pain. Therefore, the true impact of exercise alone could not be determined with strong evidence. Although there was some evidence of benefit as noted above, it became clear that categorizing exercises into a classification system according to their elements was essential in differentiating the intended effect that different types of exercises may have had. Exploring the dosage and mode of delivery of recommended exercises is essential in future reviews.

In the current update, our objective was to adapt a therapeutic model for exercise and sub‐classify the different exercises. This allowed us to link the specific aims of the exercise activity to its anatomical rationale. As a result, we gained a better perspective on the intended aim of the specific exercise, which allowed us to clarify some of the reporting variances and the variance in exercise types that may have been affecting the estimates of effect size. We wanted to determine the more accurate effect of exercises, which have clinical implications in patients with neck pain.

Objectives

This systematic review assessed the short‐ to long‐term effect of exercise therapy on pain, function, patient satisfaction, quality of life, and global perceived effect in adults experiencing mechanical neck pain with or without cervicogenic headache or radiculopathy. Where appropriate, the influence of risk of bias, duration of the disorder and subtypes of neck disorder on the treatment effect was assessed.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included any published or unpublished randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in any language. We excluded quasi‐RCTs and clinical controlled trials (CCTs).

Types of participants

Participants included in the review were adults (males or females aged 18 years or older) with acute (less than 30 days), subacute (30 days to 90 days) or chronic (greater than 90 days) neck disorders categorized as:

mechanical neck disorders (MND), which included whiplash associated disorders (WAD) category I and II (Spitzer 1987; Spitzer 1995), myofascial neck pain, and degenerative changes that encompassed osteoarthritis and cervical spondylosis (Schumacher 1993),

cervicogenic headache (CGH) (Olesen 1988; Olesen 1997; Sjaastad 1990; Sjaastad 1998; Sjaastad 2008), and

neck disorders with radicular findings (NDR) (Spitzer 1987; Spitzer 1995).

We excluded studies if they investigated neck disorders with definitive or possible long tract signs (e.g. myelopathies); neck pain caused by other pathological entities (Schumacher 1993); headache associated with the neck, but not of cervical origin; co‐existing headache, when either neck pain was not dominant or the headache was not provoked by neck movements or sustained neck postures; and 'mixed' headache.

Types of interventions

We included studies that used one or more type of exercise therapy specified in the Therapeutic Exercise Intervention Model to sub‐classify exercise (Sahrmann 2002) prescribed or performed in the treatment of neck pain. For the purposes of this review, we excluded studies in which exercise therapy was given as part of a multidisciplinary treatment, multimodal treatment (e.g. manual therapy plus exercise), or exercises that required manual therapy techniques by a trained individual (such as hold‐relax techniques, rhythmic stabilization, and passive techniques).

Types of comparisons

We contrasted interventions against the following comparisons:

sham or placebo,

no treatment or wait list, and

exercise plus another intervention versus that same intervention (for example, exercise plus manual therapy versus manual therapy).

We excluded all other comparisons.

Types of outcome measures

A study was included if it used at least one of the four primary outcome measures of interest:

pain,

measures of function/disability (including, but not limited to, neck disability index, activities of daily living, return to work, and sick leave),

patient satisfaction, and

global perceived effect/quality of life.

We extracted information on adverse events and costs of care when available.

We defined the duration of follow‐up as:

immediately post treatment (≤ one day),

short‐term follow‐up (one day to three months),

intermediate‐term follow‐up (three months up to, but not including, one year), and

long‐term follow‐up (one year or longer).

Search methods for identification of studies

A research librarian searched computerized bibliographic databases, without language restrictions, for medical, chiropractic and allied health literature. Subject headings (MeSH) and key words included anatomical terms, disorder or syndrome terms, treatment terms and methodological terms.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases from their inception up to between January and May 2014:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, which includes the CBRG Trials Register; Ovid, 21 May 2014),

MEDLINE(Ovid, 1950 to April 2014 week 4),

Embase (Ovid, 1980 to April 21, 2014),

Manual Alternative and Natural Therapy (MANTIS; Ovid, 1980 to May 2014),

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; EBSCO, 1982 to March 2014),

Index to Chiropractic literature (ICL; Jan 2014), and

ClinicalTrials.gov (May 2014).

See Appendix 1 for the search strategies used for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, MANTIS, CINAHL, and ICL.

Searching other resources

We also screened references of all retrieved full‐text articles, identified content experts and searched conference proceedings from the World Confederation of Physical Therapist (WCPT 2007; WCPT 2011, International Federation of Orthopaedic and Manipulative Therapists IFOMPT 2012; IFOMPT 2008 ‐ hardcopy used), World Federation of Chiropractic (WFC 2013 ‐ CD copy used), and searched personal files up to May 2014 for grey literature.

Data collection and analysis

For continuous data, standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using a random‐effects model. Standard mean difference was selected over mean difference (WMD) because different types of exercises were assessed and most interventions used different outcome measures that used different scales.

Selection of studies

Two review authors with expertise in medicine, physiotherapy, chiropractic, massage therapy, statistics, or clinical epidemiology independently conducted citation identification and study selection using pre‐piloted forms. The assembled group did not author any of the primary trials. We assessed agreement for study selection using the quadratic weighted Kappa statistic (Kw), Cicchetti weights (Cicchetti 1976). We resolved disagreements through consensus and consultation with a third party if required.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently conducted data abstraction on pre‐piloted forms. We resolved disagreements through consensus. We consulted a neutral third party if consensus was not reached. We contacted study authors for missing information and data clarification. We extracted data on design (RCT, number analyzed/number randomized, intention‐to‐treat analysis, power analysis), participants (disorder subtype, duration of disorder), intervention (treatment characteristics for the treatment and comparison group, dosage/treatment parameters, co‐intervention, treatment schedule, duration of follow‐up), and outcomes (baseline mean, end of study mean, absolute benefit, reported results, point estimate with 95% CI, power, side effects, cost of care, and adverse events). These factors are noted in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently conducted assessment of risk of bias in included studies using pre‐piloted forms. Disagreements were resolved through consensus (Graham 2011). The Cervical Overview Group used a calibrated team of assessors and at least two assessors independently assessed the risk of bias. 'Risk of bias' tables were presented and discussed by the broader validity assessment team to maximize inter‐rater reliability (Graham 2011), and consensus was reached on final 'Risk of bias' assessments. We did not exclude studies from this review on the basis of the 'Risk of bias' assessment results. The following biases were assessed: selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, groups similarity at baseline); performance bias (blinding of personnel/care providers, co‐intervention, and compliance); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessor); attrition bias (incomplete outcome data); reporting bias (selective reporting) (see Appendix 2 for the 'Risk of bias' criteria recommended by the Cochrane Back Review Group (Furlan 2009)). We rated each 'Risk of bias' item as low, high, or unclear and entered it into the 'Risk of bias' table for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

We used primarily SMD with 95% CIs for continuous data. There are two summary statistics used for meta‐analysis of continuous data, the mean difference (MD) and the standard mean difference (SMD). The selection of the summary statistic was determined by whether all studies in a homogenous meta‐analysis group reported an outcome using the same scale (pooled MD) or using a different scale (pooled SMD). The estimation of minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for pain, function and disability were in accordance with the Cochrane Back Group recommendations (Furlan 2009). For the purpose of the review, the MCID for pain was 10 on a 100‐point pain intensity scale (Farrar 2001; Felson 1995; Goldsmith 1993). To assign some descriptors on the size of the difference between the treatment group and control groups, we considered the effect to be small when it was less than 10% of the visual analogue scale (VAS) scale, medium when it was between 10% and 20% of the VAS scale, and large when it was 20% to 30% of the VAS scale. For the neck disability index (NDI), we used a MCID of 7/50 neck disability index units (MacDermid 2009). It is noted that the minimal detectable change varies from 5/50 for non‐complicated neck pain to 10/50 for cervical radiculopathy (MacDermid 2009). For other outcomes (i.e. global perceived effect and quality of life), where there was an absence of clear guidance on the size of clinically important effect sizes, we used the common hierarchy of Cohen 1988: small (0.20), medium (0.50) or large (0.80). Risk ratios (RR) were calculated for dichotomous outcomes. When neither continuous nor dichotomous data were available, we extracted the findings and the statistical significance as reported by the author(s) in the original study.

Dealing with missing data

Where data were not extractable, we contacted the primary authors. For continuous outcomes reported as medians, we calculated effect sizes (Kendal 1963; p 237).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Prior to calculation of a pooled effect measure, the reasonableness of pooling was assessed, based on clinical judgement. Using a random‐effects model, statistical heterogeneity was tested using the Chi2 method between the studies. In the absence of heterogeneity (P > 0.10), we calculated a pooled SMD, MD or RR.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess reporting bias using sensitivity analysis but this was not possible due to a paucity of trials in any one category. Assessment of publication bias included use of the graphical aide funnel plot.

Data synthesis

We assessed the quality of the body of the evidence using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2006). Domains that may have decreased the quality of the evidence are: 1) study design, 2) risk of bias, 3) inconsistency of results, 4) indirectness (not generalizable), 5) imprecision (insufficient data), other factors (e.g. reporting bias) (Higgins 2009). The quality of the evidence was adjusted by a level based on the performance of the studies against the five domains. All plausible confounding factors were considered, as were their effects on the demonstrated treatment effects and their impact on the dose‐response gradient (Atkins 2004).

Levels of evidence were defined as follows.

High quality evidence: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. There are consistent findings among 75% of RCTs, with low risk of bias, that generalize to the population in question. There are sufficient data, with narrow confidence intervals. There are no known or suspected reporting biases (all of the domains are met).

Moderate quality evidence: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate (one of the domains is not met).

Low quality evidence: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate (two of the domains are not met).

Very low quality evidence: We are very uncertain about the estimate (three of the domains are not met).

No evidence: No RCTs were identified that measured this outcome.

We used the Cochrane GRADE approach and considered a number of additional factors (adverse events, costs, temporality, plausibility, dose response, strength of association, and clinical applicability) to place the results into a larger context. The number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB) and treatment advantages were calculated to communicate the magnitude of effect for main findings (Gross 2002).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Not conducted due to lack of data.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis or meta‐regression for the factors: symptom duration, methodological quality and subtype of neck disorder were planned but were not carried out because we did not have enough data in any one category.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

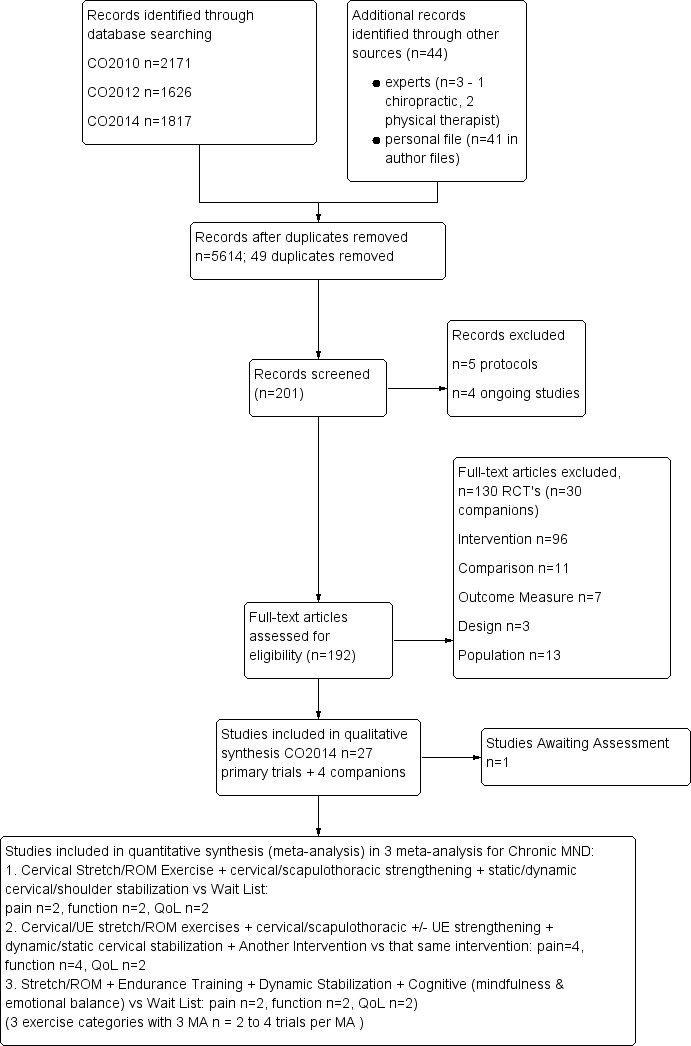

Considering all sources, we identified 5614 records through database searches and we found 44 records from other sources searched from start up to November 2013. Following screening of 201 full text articles, 192 were assessed for eligibility, (agreement on selection showed weighted kappa 0.94, SE 0.02). After further application of the eligibility criteria, we found 27 trials that used exercise treatment for non‐specific subacute and chronic neck pain, and selected them for this review; Figure 1 describes the flow of included, excluded, and ongoing, as well as those awaiting classification.

1.

Study flow diagram (PRISMA).

Included studies

Twenty‐seven trials [(2485/3005) analyzed at end of study /randomized participants] were selected for this review.

Three studies described different aspects of the same study population under additional publications: Andersen 2008 ‐ one trial, two publications; Bronfort 2001 ‐ one trial, four publications; Stewart 2007 ‐ one trial, three publications.

Twenty‐four trials evaluated neck pain: one evaluated acute neck pain (Lange 2013); one evaluated acute/subacute/chronic neck pain (Kjellman 2002); one evaluated subacute neck pain (Chiu 2005); four evaluated subacute/chronic neck pain (Andersen 2008; Andersen 2011; Andersen Ch 2012; Stewart 2007); 16 trials evaluated chronic neck pain (Allan 2003; Ang 2009; Beer 2012; Bronfort 2001; Dellve 2011; Franca 2008; Hansson 2013; Helewa 2007; Humphreys 2002; Lundblad 1999; Hallman 2011; Martel 2011; Rendant 2011; Revel 1994; Viljanen 2003; von Trott 2009); and one trial did not specify the duration of neck pain (Takala 1994).

One study reported on neck disorder with radicular signs and symptoms (Kuijper 2009) and 14 studies did not specify if radicular signs and symptoms were present (Andersen 2011; Andersen Ch 2012; Beer 2012; Dellve 2011; Hall 2007; Hallman 2011; Hansson 2013; Helewa 2007; Humphreys 2002; Lange 2013; Lundblad 1999; Rendant 2011; Viljanen 2003; von Trott 2009).

Two trials investigated cervicogenic headache, one subacute (Hall 2007) and the other chronic (Jull 2002).

One trial investigated acute radiculopathy (Kuijper 2009).

Studies varied in sample size from 16 to 340 (n analyzed), and 27 of 28 trials were considered small (less than 70 participants per intervention arm).

Excluded studies

Studies (n=130 primary papers and 30 companion paper) were excluded for the following reasons: two used a quasi‐RCT design, one used a prospective observational design, 12 examined a different type of participant (e.g. chronic tension headache, cervical dystonia), one reported on a subgroup of the included population, 96 tested a different intervention (e.g. not active exercise, the exercise was the same in all groups, or the exercise group could not be separated out from a multimodal intervention), 11 used a comparison group and seven did not measure any of the identified primary outcomes. See Characteristics of excluded studies tables for more details.

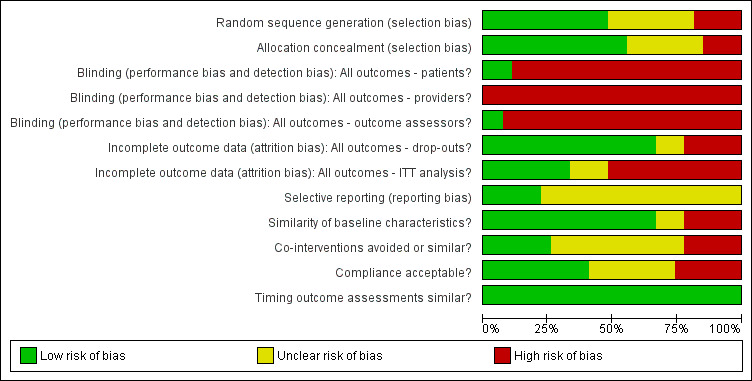

Risk of bias in included studies

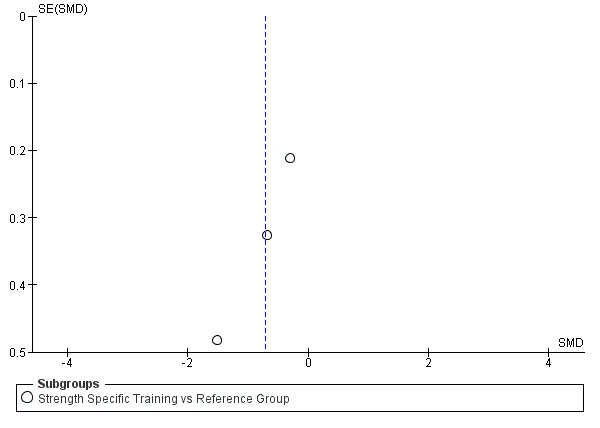

We used the quadratic weighted Kappa (Kw) statistic to assess agreement on a per question basis (Kw 0.23 to 1.00). Each 'Risk of Bias' item is presented as a percentage across all included studies Figure 2. Common methodological weaknesses included each of the criteria listed below (see 'Risk of Bias' tables). Methodological quality did not appear to influence the end results of the reviews; both high and low quality studies had similar outcome directions. Albeit, limited data were available to analyze for publication bias; Figure 3 suggests that we cannot rule out publication bias. This relationship between risk of bias and end results of the review was not formally tested using sensitivity analysis or meta‐regression, as there were not enough trials in any one meta‐analysis.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: 7 Acute to Chronic MND: Scapulothoracic + UE Strengthening vs CONTROL, outcome: 7.2 Pain Intensity: 10 to 20 weeks of treatment.

Allocation

There was failure to describe or use appropriate concealment of allocation in 42.9% of studies.

Blinding

There was a lack of effective "blinding" procedures in 92.9% of trials ‐ the minimum expectation being blinding of the outcome assessor.

Incomplete outcome data

There were incomplete outcome data provided by 28.6% of the trials.

Selective reporting

There was selective reporting bias with 78.6% of the trials.

Other potential sources of bias

Compliance was monitored and acceptable in only 42.9% of trials, and co‐intervention was either not avoided or not described in 71.4% of trials. The funnel plot (Figure 3) has the classic small negative trial missing that may suggest publication bias (language bias); we did not search non‐English databases. Alternatively, it could reflect the poor methodological quality leading to inflated effects in smaller trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5; Table 6; Table 7; Table 8; Table 9; Table 10; Table 11; Table 12; Table 13

Chronic Mechanical Neck Pain

1. Support Element

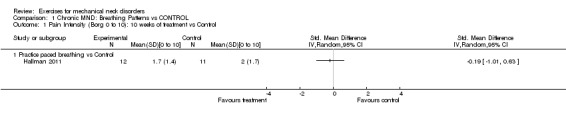

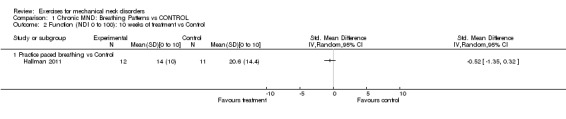

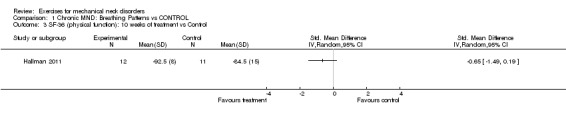

a) Breathing Exercises

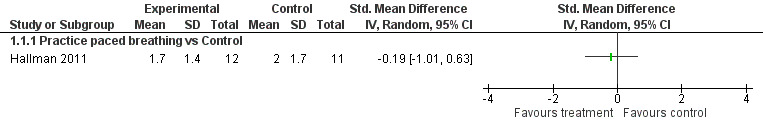

Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises versus Control

One trial Hallman 2011 compared diaphragmatic breathing with a no treatment control. This latter group took part in the breathing protocol in sessions 1 and 10, without any prescribed treatment in between.

Pain Intensity outcomes

No difference in pain between groups immediately post treatment (Figure 4).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Chronic MND: Breathing Patterns vs CONTROL, outcome: 1.1 Pain Intensity (Borg 0 to 10): 10 weeks of treatment vs Control.

Function outcomes

No difference in function between groups immediately post treatment.

Quality of Life outcomes

No difference in quality of life between groups immediately post treatment.

Conclusion: There is low quality evidence (one trial, 24 participants, Hallman 2011) that diaphragmatic breathing may have no effect on pain, function and quality of life when compared to a no treatment control for chronic mechanical neck pain immediately post treatment (50 sessions over 10 weeks).

b) Cardiovascular/Aerobic Training

General Fitness Training versus Control

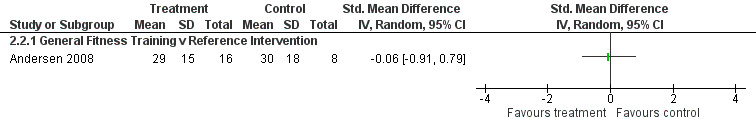

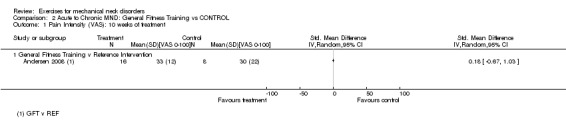

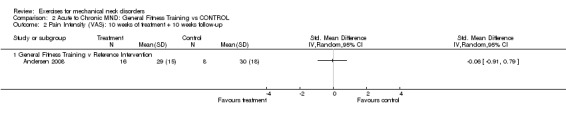

One trial with two publications (Andersen 2008) compared a general exercise program with a no treatment control (general health information) intervention.

Pain Intensity Outcomes

No difference in pain between both (see above: general exercise versus control) groups immediately post treatment (Figure 5).

5.