Abstract

An 83-year-old male with complete atrioventricular block underwent dual-chamber pacemaker implantation. Venography showed normal anatomy of the left axillary vein. Following sedation with intravenous propofol, local anesthesia, and skin incision, we punctured the left axillary vein on the first limb. However, the guidewire could not be advanced despite blood backflow after the initial puncture. On venography, left axillary vein on the first limb totally disappeared with dilated collaterals. We diagnosed axillary vein spasm and injected 1000 μg of intravenous nitroglycerin. After 15 min, repeated venography showed slight contrast flow in the axillary vein. We alternatively punctured the axillary vein on the second limb. However, the axillary vein was spasmodically occluded again. We considered the possibility that puncture of the right axillary vein could also result in venous spasm. Since the left cephalic vein was identified after waiting time, we partially cut down the left cephalic vein and inserted guidewires into the vein. The ventricular and atrial leads were successfully implanted through sheaths in the right ventricular septum and right atrial appendage, respectively.

Learning objective

Pacemaker implantation complicated with puncture-related axillary vein spasm is challenging. Severe venous spasms refractory to waiting time or nitroglycerin sometimes require conversion of access site. However, the bail-out technique from ipsilateral access remains unclear. Cut-down technique of the ipsilateral cephalic vein is one alternative to manage severe axillary vein spasm refractory to nitroglycerin and waiting time.

Keywords: Axillary vein puncture, Cephalic vein, Cut-down technique, Pacemaker implantation, Venous spasm

Introduction

Contrast-guided axillary vein puncture is a widely used technique for the implantation of transvenous leads of cardiac implantable electronic devices. Although venous spasm is recognized as one of the common complications, its mechanism and bail-out techniques are scarcely known. Drug-refractory severe venous spasm is an independent risk factor for pacemaker implantation failure and may require a change in the access site [1]. Herein, we present a case of severe venous spasm induced by contrast-guided axillary vein puncture, which was converted to partial cut-down of the ipsilateral cephalic vein, resulting in successful pacemaker implantation.

Case report

An 83-year-old man was admitted to the emergency department owing to recurrent episodes of syncope. The electrocardiogram showed complete atrioventricular block with escaped ventricular rhythm of 32 beats per minute. Chest X-ray showed no cardiomegaly, pleural effusion, or congestion. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed normal left ventricular size and function without any valvular disease. Coronary angiography showed no coronary stenosis. The patient was scheduled for dual-chamber pacemaker implantation on the left side.

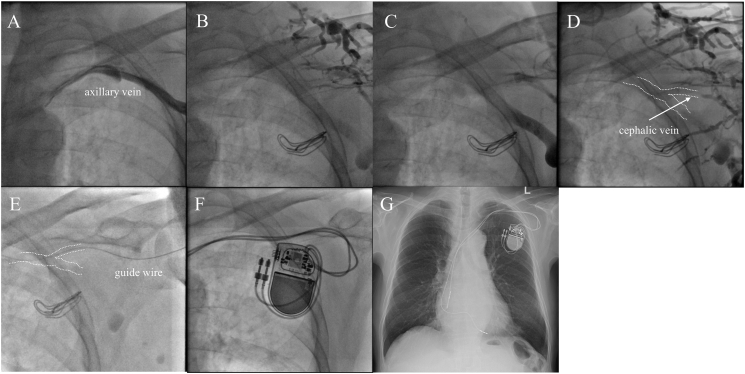

Venography with 10 ml of intravenous contrast agent [iopamidol, a nonionic, low-osmolar iodinated contrast agent (300 mgI/ml)] showed normal anatomy of the left axillary vein (Fig. 1A). Following sedation with intravenous propofol, local anesthesia, and skin incision, we punctured the left axillary vein on the first limb guided by fluoroscopy. The first puncture showed good blood backflow. However, the guidewire could not be advanced after the initial puncture. Venography revealed that the left axillary vein on the first limb completely disappeared with dilated collaterals (Fig. 1B). We diagnosed axillary vein spasm and injected 1000 μg of intravenous nitroglycerin. After 15 min, repeated venography showed slight flow of contrast agent in the left axillary vein (Fig. 1C). We alternatively punctured the axillary vein on the second limb. Despite blood backflow, the guidewire could not also be advanced. Venography revealed total occlusion of the axillary vein again (Fig. 1D). We considered the possibility that puncture of the right axillary vein could also result in severe venous spasm. Since the left cephalic vein was slightly evident after the waiting time, we directly performed partial cut-down of the left cephalic vein under sufficient sedation without additional administration of vasodilators or sedative agents. We considered that direct insertion of ventricular and atrial pacemaker leads into the cephalic vein could be difficult because of the spastic narrow cephalic vein. Therefore, we decided to insert two guidewires through an inserter into the cephalic vein from a single cut-down site first. Consequently, guidewires were successfully advanced (Fig. 1E). Then, two sheaths were also inserted into the cephalic vein without exacerbation of venous spasm. The ventricular and atrial leads were screwed through sheaths in right ventricular septum and right atrial appendage, respectively. After confirmation of acceptable capture and sensing thresholds (sensed R wave 14.3 mV, threshold 0.9 V/0.4 ms, sensed P wave 3.0 mV, threshold 0.5 V/0.4 ms), both leads were connected to a pacemaker generator set to DDD (Fig. 1F). Chest X-ray showed proper deflection of leads (Fig. 1G). Ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced computed tomography performed the following day after the procedure showed patency of the left axillary vein (Fig. 2A and B). The patient has been free from device-related events for six months.

Fig. 1.

Details of the procedure. (A) Venography showing normal anatomy of the left axillary vein. (B) After first puncture, the left axillary vein on the first limb completely disappeared with dilated collaterals. (C) After 15 min, repeated venography showed slight flow of contrast agent in the left axillary vein. (D) After second puncture, venography depicted total occlusion of the axillary vein again. (E) We directly performed partial cut-down of the left cephalic vein and inserted guidewires into the cephalic vein. (F) Both leads were connected to a pacemaker generator. (G) Chest X-ray showing proper deflection of the leads.

Fig. 2.

Left axillary vein on the day after pacemaker implantation. (A) Ultrasonography showed patency of the left axillary vein. (B) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography demonstrated blood flow of the left axillary vein.

Discussion

Contrast-guided axillary vein puncture is a common procedure for the placement of pacing and defibrillation leads for many cardiologists in the present day, along with partial cut-down of the cephalic vein. Although axillary vein spasm is a common complication in contrast-guided axillary vein puncture in transvenous pacemaker lead implantation, the bail-out technique has rarely been described. Duan et al. [1] reported that venous spasm occurred in 37.8% of patients during axillary venous puncture. Severe venous spasm, defined as a reduction of more than 90% in the lumen caliber, occurred in 8.1% of patients and led patients to failure of venous puncture. In addition, drug-refractory severe venous spasm is an independent risk factor of pacemaker implantation failure and may require a change of access site [1]. Venous spasm is inducible by chemical effect of contrast agent, mechanical stimulation by puncture needle and guidewire [2].

Nitroglycerin, which is a commonly used vasodilatory drug for arterial spasm, has a beneficial effect on preventing venous spasm [3]. However, once venous spasm occurs, the effectiveness of nitroglycerin is limited [4]. In cases of severe venous spasm refractory to nitroglycerin with waiting time, the bail-out technique other than changing access site remains unclear. Cephalic vein cut-down technique facilitates less frequent complications such as pneumothorax and pacemaker lead failure, however, it can be technically challenging because of tortuousness, small caliber, and complexity of identification of the cephalic vein, and attribute longer procedural time compared to contrast-guided axillary vein puncture [5]. However, considering the possibility of severe venous spasm on the contralateral side, cephalic vein cut-down technique is an alternative approach for severe axillary vein spasm.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Duan X., Ling F., Shen Y., Yang J., Xu H.Y. Venous spasm during contrast-guided axillary vein puncture for pacemaker or defibrillator lead implantation. Europace. 2012;14:1008–1011. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnappa D., Sakaguchi S., Kasinadhuni G., Tholakanahalli V.N. An unyielding valve leading to venous spasm during pacemaker implantation: a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2019;3:1–4. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytz142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duan X., Ling F., Shen Y., Yang J., Xu H.Y., Tong X.S. Efficacy and safety of nitroglycerin for preventing venous spasm during contrast-guided axillary vein puncture for pacemaker or defibrillator leads implantation. Europace. 2013;15:566–569. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan N.Y., Leung W.S. Venospasm in contrast venography-guided axillary vein puncture for pacemaker lead implantation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2003;26:112–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atti V., Turagam M.K., Garg J., Koerber S., Angirekula A., Gopinathannair R., et al. Subclavian and axillary vein access versus cephalic vein cutdown for cardiac implantable electronic device implantation: a meta-analysis. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2020;6:661–671. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]