Abstract

Background

Multi‐strategic community wide interventions for physical activity are increasingly popular but their ability to achieve population level improvements is unknown.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of community wide, multi‐strategic interventions upon population levels of physical activity.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Public Health Group Segment of the Cochrane Register of Studies,The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, MEDLINE in Process, EMBASE, CINAHL, LILACS, PsycINFO, ASSIA, the British Nursing Index, Chinese CNKI databases, EPPI Centre (DoPHER, TRoPHI), ERIC, HMIC, Sociological Abstracts, SPORTDiscus, Transport Database and Web of Science (Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index). We also scanned websites of the EU Platform on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; Health‐Evidence.org; the International Union for Health Promotion and Education; the NIHR Coordinating Centre for Health Technology (NCCHTA); the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and NICE and SIGN guidelines. Reference lists of all relevant systematic reviews, guidelines and primary studies were searched and we contacted experts in the field. The searches were updated to 16 January 2014, unrestricted by language or publication status.

Selection criteria

Cluster randomised controlled trials, randomised controlled trials, quasi‐experimental designs which used a control population for comparison, interrupted time‐series studies, and prospective controlled cohort studies were included. Only studies with a minimum six‐month follow up from the start of the intervention to measurement of outcomes were included. Community wide interventions had to comprise at least two broad strategies aimed at physical activity for the whole population. Studies which randomised individuals from the same community were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

At least two review authors independently extracted the data and assessed the risk of bias. Each study was assessed for the setting, the number of included components and their intensity. The primary outcome measures were grouped according to whether they were dichotomous (per cent physically active, per cent physically active during leisure time, and per cent physically inactive) or continuous (leisure time physical activity time (time spent)), walking (time spent), energy expenditure (as metabolic equivalents or METS)). For dichotomous measures we calculated the unadjusted and adjusted risk difference, and the unadjusted and adjusted relative risk. For continuous measures we calculated percentage change from baseline, unadjusted and adjusted.

Main results

After the selection process had been completed, 33 studies were included. A total of 267 communities were included in the review (populations between 500 and 1.9 million). Of the included studies, 25 were set in high income countries and eight were in low income countries. The interventions varied by the number of strategies included and their intensity. Almost all of the interventions included a component of building partnerships with local governments or non‐governmental organisations (NGOs) (29 studies). None of the studies provided results by socio‐economic disadvantage or other markers of equity. However, of those included studies undertaken in high income countries, 14 studies were described as being provided to deprived, disadvantaged or low socio‐economic communities. Nineteen studies were identified as having a high risk of bias, 10 studies were unclear, and four studies had a low risk of bias. Selection bias was a major concern with these studies, with only five studies using randomisation to allocate communities. Four studies were judged as being at low risk of selection bias although 19 studies were considered to have an unclear risk of bias. Twelve studies had a high risk of detection bias, 13 an unclear risk and four a low risk of bias. Generally, the better designed studies showed no improvement in the primary outcome measure of physical activity at a population level.

All four of the newly included, and judged to be at low risk of bias, studies (conducted in Japan, United Kingdom and USA) used randomisation to allocate the intervention to the communities. Three studies used a cluster randomised design and one study used a stepped wedge design. The approach to measuring the primary outcome of physical activity was better in these four studies than in many of the earlier studies. One study obtained objective population representative measurements of physical activity by accelerometers, while the remaining three low‐risk studies used validated self‐reported measures. The study using accelerometry, conducted in low income, high crime communities of USA, emphasised social marketing, partnership with police and environmental improvements. No change in the seven‐day average daily minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity was observed during the two years of operation. Some program level effect was observed with more people walking in the intervention community, however this result was not evident in the whole community. Similarly, the two studies conducted in the United Kingdom (one in rural villages and the other in urban London; both using communication, partnership and environmental strategies) found no improvement in the mean levels of energy expenditure per person per week, measured from one to four years from baseline. None of the three low risk studies reporting a dichotomous outcome of physical activity found improvements associated with the intervention.

Overall, there was a noticeable absence of reporting of benefit in physical activity for community wide interventions in the included studies. However, as a group, the interventions undertaken in China appeared to have the greatest possibility of success with high participation rates reported. Reporting bias was evident with two studies failing to report physical activity measured at follow up. No adverse events were reported.The data pertaining to cost and sustainability of the interventions were limited and varied.

Authors' conclusions

Although numerous studies have been undertaken, there is a noticeable inconsistency of the findings in the available studies and this is confounded by serious methodological issues within the included studies. The body of evidence in this review does not support the hypothesis that the multi‐component community wide interventions studied effectively increased physical activity for the population, although some studies with environmental components observed more people walking.

Plain language summary

Community wide interventions for increasing physical activity

Not having enough physical activity leads to poorer health. Regular physical activity can reduce the risk of chronic disease and improve one's health and wellbeing. The lack of physical activity is a common and in some cases a growing health problem. To address this, 33 studies have used improvement activities directed at communities, using more than one approach in a single program. When we first looked at the available research in 2011 we observed that there was a lack of good studies which could show whether this approach was beneficial or not. Some studies claimed that community wide programs improved physical activities and other studies did not. In this update we found four new studies that were of good quality; however none of these four studies increased physical activity levels for the population. Some studies reported program level effects such as observing more people walking, however the population level of physical activity had not increased. This review found that community wide interventions are very difficult to undertake, and it appears that they usually fail to provide a measurable benefit in physical activity for a population. It is apparent that many of the interventions failed to reach a substantial portion of the community, and we speculate that some single strategies included in the combination may lack individual effectiveness.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Community wide interventions for promoting physical activity | |||

|

Patient or population: whole communities (adults, adolescents and children) Settings: community based Intervention: multi‐component of at least two physical activity interventions targeting the whole community Comparison: existing programmes and infrastructure | |||

| Outcomes [duration of follow up] | Summary of effects | Number of communities (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) |

|

Physical activity % Physically active Intervention compared to control adjusted pre/post cross‐sectional sampling (end of intervention to 6 years) |

Typically no evidence of benefit | 25 (10) | ⊕⊕OO1 Low |

|

Physical activity % physically active Intervention compared to control adjusted pre‐post cross‐sectional sampling (end of intervention to 3 years, 4 months) |

Typically no evidence of benefit | 160 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High |

|

Energy expenditure METS/week score, adjusted mean difference (follow up; end of intervention to 4 years) |

Typically no evidence of effect Range: ‐241 to +176 |

156 (5) | ⊕⊕OO1 Low |

|

Physical activity Average daily minutes of moderate to vigorous (24 months) |

No evidence of effect from the baseline of 36 minutes per day | 2 (1) | ⊕⊕⊕O2 Moderate |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||

1Substantial heterogeneity between trials regarding type of interventions and measured outcomes; wide and overlapping range of effects

2Findings based on a single study in only two communities

Background

Physical activity is recognised as being important for reducing the overall burden of disease (WHO 2009). Very strong scientific evidence based on a wide range of well‐conducted studies shows that physically active people have higher levels of health‐related fitness, a lower risk profile for developing a number of disabling medical conditions and lower rates of various chronic diseases than do people who are inactive (US Physical Activity Guidelines 2008).

Despite the positive health effects associated with regular physical activity, physical inactivity remains a common public health problem in high, middle and low income countries (Heath 2012). The prevalence of physical inactivity remains high, and in some cases has even increased in recent years (Bauman 2009; Guthold 2008). In addition, low income and ethnic minority adults have the highest rates of physical inactivity, people at the top of the socio‐economic scale appear to perform more leisure‐time activity than those at the bottom of the scale, and participation is patterned by age and gender (Belanger 2011; Crespo 2000; Crespo 2001; Gidlow 2006).

The lack of physical activity cannot be attributed solely to personal motivation and so countries that are tackling this complex issue are increasingly electing to employ multi‐component approaches (that is informational, behavioural, and environmental) in increasing a population's physical activity (Heath 2012; Kahn 2002; WHO 2004).

Description of the intervention

Community wide interventions are attractive in that they aim to improve the health risk factors (especially low physical activity) of a whole population. These strategies generally involve investment in visible infrastructure and planning initiatives with the aim of producing long‐lasting benefits for the community. They differ from singular community based strategies which may target only a particular subset of the population. Community wide interventions offer a number of advantages over offering only one approach to a population. They operate at a series of levels to impact on behaviour. These levels reflect social‐ecological models of health and include changes to policies and environments, and involve mass media and individually focused activities (for example primary healthcare screening).

One systematic review has categorised these interventions into four types (Cavill and Foster 2004). These are (1) comprehensive integrated community approaches, where physical activity is part of an overall risk factor reduction programme (for example the Minnesota Heart Health Project (Luepker et al 1994)); (2) community wide ‘campaigns’ using mass media (Renger 2002)); (3) community based approaches using person focused techniques; and (4) community approaches to environmental change. The third category includes programmes that use methods and strategies such as one‐to‐one counselling, classroom instruction, and cognitive‐behavioural strategies but in community facilities and settings such as church halls or community centres (Sharpe 2003). The final category includes programmes that use some form of community action, often including a coalition or advocacy group, to make positive changes to the physical environment (King 1994). These interventions are often delivered to communities in combinations.

How the intervention might work

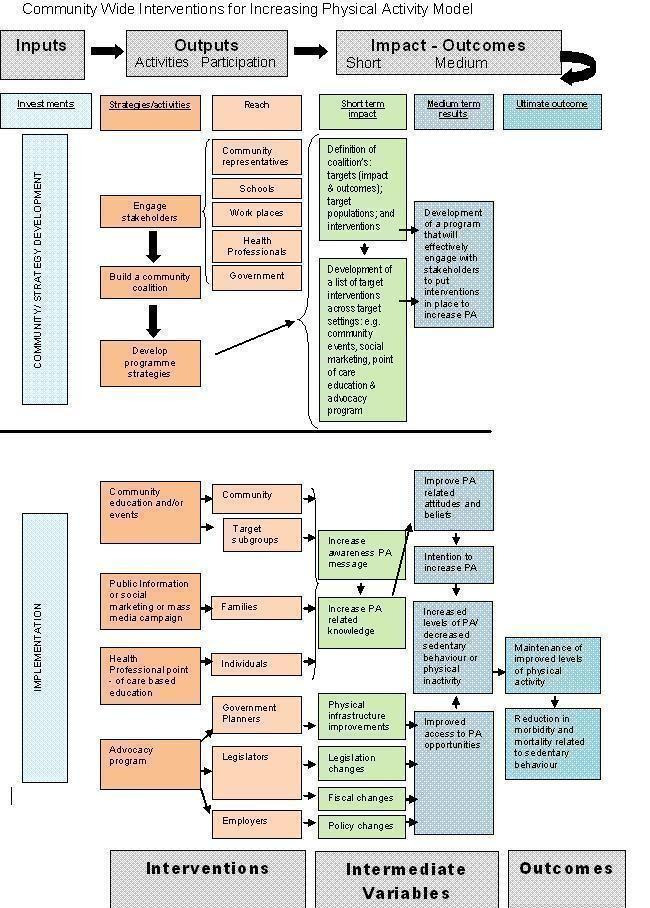

We developed a logic model to capture the broad range of different approaches found in community interventions (Figure 1). This framework divides the actions into two phases, a community strategy development phase and an implementation phase, as there is some evidence to suggest community wide approaches appear more sustainable in the longer term (Foster 2000). The community strategy development phase describes the construction phase of a community intervention. Actions include identification of target groups, populations, the setting for delivery, stakeholders and intervention options. The implementation phase describes the delivery of actions to encourage physical activity behaviour change. Actions might include mass media campaigns, community participation or educational events, advocacy and environmental changes. The outputs of both phases might be measured in a range of variables as short to long‐term outcomes. For example, intermediate outcomes could include knowledge of the benefits of an active lifestyle or improved access to physical activity. Examples of long‐term outcomes could be a reduction in morbidity and mortality related to physical activity behaviour. Changes in the proximal and intermediate variables, such as knowledge or attitudes, are likely to be more amenable to change through communication campaigns (Cavill and Bauman 2004).

1.

Logic Model for Community Wide Interventions for Increasing Physical Activity.

Why it is important to do this review

Many studies of community wide interventions have been undertaken but, prior to our earlier review, few have published evaluations of their process or impact. Although the popularity of these interventions is increasing, there was a need to combine all the global evidence currently available in an up‐to‐date systematic review. We believed a review would enable a more in‐depth exploration of the effectiveness of the interventions as well as investigating equity and inclusiveness issues. Earlier reviews (for example Kahn 2002) do not contain the more recent studies and newer health promotion strategies built upon more recent research and health promotion theory. It is hoped that this update of the Cochrane review will be particularly useful to those decision makers with the responsibility of selecting and implementing community wide investments. The application of the logic model for this review illustrates the belief that community wide interventions should be understood more broadly than as being just the sum of several interventions that have been implemented in a community.

Objectives

Primary research objective

We sought to determine the effects of community wide, multi‐strategic interventions upon community levels of physical activity.

Secondary research objectives

We addressed the following predetermined research objectives.

To explore whether any effects of the intervention are different within and between populations, and whether these differences form an equity gradient.

To describe other health (e.g. cardiovascular disease morbidity) and behavioural effects (e.g. diet) where appropriate outcomes are available.

To explore the influence of context in the design, delivery and outcomes of the interventions.

To explore the relationship between the number of components, duration and effects of the interventions. As an addition to the published protocol, we sought to understand more explicitly whether the intensity of the community wide intervention could explain differences of effects between studies.

To highlight implications for further research and research methods to improve knowledge of the interventions in relation to the primary research objective.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

It is recognised that public health and health promotion interventions are evaluated using a wide variety of approaches and designs. We permitted the inclusion of cluster randomised controlled trials, randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐experimental designs which used a control population for comparison, interrupted time‐series (ITS) studies, and prospective controlled cohort studies (PCCS). Only studies with a minimum six‐month follow up from the start of the intervention to measurement of outcomes were included. The six‐month period was considered as the minimal time frame as physical activity behaviour changes, as understood by the Prochaska and DiClemente model (Prochaska 1992), are established in the action stage, which is when the individual actively engages in the new behaviour. For physical activity, the highest likelihood for relapse occurs within the first six months of starting a regular program (Dishman 1994).

Types of participants

The term community wide generally refers to either: 1) an intervention directed at a geographic area, such as a city or a town defined by geographical boundaries; or 2) an intervention directed toward groups of people who share at least one common social or cultural characteristic.

As the focus of the review was whole‐of‐community interventions, we defined participants in the included studies as comprising those persons of any age residing in a geographically defined community, such as urban, peri‐urban, village, town, or city. We excluded interventions which were whole of state or country. Although some of the strategies targeted individuals with chronic disease, collectively the participants included in the studies needed to be representative of the whole community and not restricted to a particular geographic subregion (for example a park) or subgroups (for example only elderly people). To be included, a strategy must have shown intent to be comprehensive in reaching the targeted community. Participants must have been free living and not part of any institutionalised community, such as those who were mentally ill, the frail or bedridden elderly population, or those incarcerated in prison.

Types of interventions

It is recognised that to achieve a whole of community approach requires more than a singular strategy, as changing behaviour is a difficult task (Mummery 2009). Although little is known about how to reach the most disadvantaged groups in the community (Mummery 2009), we defined a community wide approach as one which should include strategies that have, within their scope, outreach to many disadvantaged groups. For this review, we defined a community wide intervention as one which has at least two of the following six broad strategies aimed at physical activity. The list categories of suitable strategies, which would be components of an integrated community wide intervention, are consistent with the logic model.

1. Social marketing through local mass media (e.g. television (TV), radio, newspapers).

2. Other communication strategies (e.g. posters, flyers, information booklets, websites, maps) to raise awareness of the project and provide specific information to individuals in the community.

3. Individual counselling by health professionals (both publicly and privately funded), such as the use of physical activity prescriptions.

4. Working with voluntary, government and non‐government organisations, including sporting clubs, to encourage participation in walking, other activities and events.

5. Working within specific settings such as schools, workplaces, aged care centres, community centres, homeless shelters, and shopping malls. This may include settings that provide an opportunity to reach disadvantaged persons.

6. Environmental change strategies such as creation of walking trails and infrastructure with legislative, fiscal or policy requirements, and planning (having ecological validity) for the broader population.

Studies that were community based but did not include at least two of the six stated strategies were excluded. We recognised that single strategy interventions (for example mass media only) are likely to be topics of other reviews and they were beyond the scope of this review.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Whilst it is desirable to focus on a small range of outcome measures, the context for research in this area of health is that measures of physical activity at a population level are complex (both the measures and the methods) and international consensus on gold standards has not been reached.

To be included in this review, studies needed to measure physical activity in the study population. Physical activity could be quantified using a variety of measurements, for example percentage of people active or inactive, frequency of physical activity, percentage meeting recommendations, percentage undertaking active travel; and other objective (for example accelerometers, pedometers) or subjective methods (for example self‐reported questionnaires, diaries) (Bassett et al 2008).

Secondary outcomes

Data on other related measures of health were extracted.

1. Measures of health outcomes and risk factor status (e.g. cardiovascular disease, body mass index (BMI), energy expenditure).

2. Measures of other health behaviours (e.g. sedentary behaviour, dietary patterns, or smoking).

3. Intermediate outcomes (e.g. knowledge of and attitudes toward the benefit of physical activity).

4. Any adverse outcomes that were reported (e.g. unintended changes in other risk factors, opportunity cost, and injuries).

Process measures

Measures relating to the process of implementing an intervention were also extracted.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

Cochrane Public Health Group Specialised Register in the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS);

The Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process;

EMBASE;

CINAHL;

PsycINFO ;

LILACS;

ASSIA;

British Nursing Index (BNI);

Database: CAJ, CCND, CPCD, CJSS, CMFD, CDFD, Chinese CNKI databases (http://www.global.cnki.net/grid20/index.htm);

EPPI Centre;

DoPHER;

TRoPHI;

ERIC;

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (grey literature);

Sociological Abstracts;

SPORTDiscus;

Transport Database TRIS;

Web of Science

Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index,

Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index.

We searched the following websites for relevant publications, including grey literature:

EU Platform on Diet, Physical Activity and Health;

Health Evidence (http://healthevidence.org);

IUHPE (International Union for Health Promotion and Education);

NCCHTA (National Coordinating Centre for Health Technology Assessment) (http://www.ncchta.org);

NICE guidelines (http://www.nice.org.uk);

SIGN guidelines (http://www.sign.ac.uk);

US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (http://www.cdc.gov/);

World Health Organization (http://www.who.int/en/).

Searches were carried out for studies published from January 1995 to January 2014. The search strategies and details of the search dates can be found in Appendix 1 . The MEDLINE search was developed for precision and sensitivity with advice from the Public Health Group's Trials Search Co‐ordinator and tested against a set of 38 relevant studies from across the globe. The search was then adapted to the remaining databases using database‐specific subject headings, where available.

Searching other resources

In addition, reference lists of all relevant systematic reviews, guidelines and included primary studies were searched.

For the original review, the following experts in the field were contacted to ask if they were aware of any recently published, in press or unpublished studies: Dr Harry Rutter (National Obesity Observatory, Oxford), Dr Nick Cavill (Oxford University), Mr Glenn Austin (GP Links Wide‐Bay), Mr Jiandong Sun (Queensland University of Technology), Professor Kerry Mummery (University of Central Queensland), Professor Gregory W Heath (University of Tennessee College of Medicine) and Professor Ross C Brownson (Washington University in St Louis). Subsequent to the original review we had studies brought to our attention by experts and researchers.

The past 12 months of the six journals that contained two or more studies (completed or in progress) meeting the review inclusion criteria were handsearched in the original review, however for the update this was determined as unnecessary and was not repeated. The journals were:

American Journal of Public Health;

Australia Health Promotion;

BMC Public Health;

Norsk Epidemiologi;

Preventive Medicine;

Scandinavian Journal of Public Health.

Through various methods, including contact with authors, the review team obtained a full text PDF or an abstract containing sufficient details to determine eligibility of all potentially relevant studies. Non‐English study reports were all examined by readers with appropriate language skills to determine whether they were to be excluded or included.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The initial search strategy produced a listing of nearly 26,000 citations across the original review and this update. An initial screening of titles and abstracts was undertaken to remove those which were obviously outside the scope of the review. Authors were overly inclusive at this stage and, if in doubt, a paper was left in. The full text was obtained for the papers potentially meeting the inclusion criteria (based on the title and abstract only) and multiple publications and reports on the same study were linked together. All the full text papers obtained were then screened by two review authors (PB and shared between DF, JS, and CF) who compared the description of the intervention with the logic model (Figure 1) to assess whether the required components of a community wide intervention and permissible study designs were fully met. Where there was a persisting difference of opinion, a third review author was asked to review the paper in question and a consensus was reached between the three review authors.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted for all the studies that met the inclusion criteria. For each study, two review authors (PB and shared between DF, JS, and CF) independently completed data extraction forms, which were tailored to the requirements of this review. Quality criteria questions for RCTs, controlled clinical trials (CCTs), controlled before and after (CBA) studies and ITS study designs were incorporated into the data extraction form. A checklist was used to ensure inclusion of data relevant for health equity (Ueffing 2009). In addition, multiple reports and publications of the same study were assembled and compared for completeness and possible contradictions. Data were extracted from companion studies that reported findings on the process evaluation of the intervention. The specific components present in the primary paper and companion publications were reviewed using the logic model (Figure 1) to assist in the categorisation of studies and interpretation of results where heterogeneity was present.

Numerical data for analysis were extracted from the included studies and managed in an Excel spreadsheet.

The data extraction form was first piloted by three review authors (PB, DF, and JS) to assess its ability to capture study data and inform assessment of study quality. Problems in the use of the form that were identified were resolved through discussion and the form was revised as required.

Where studies reported more than one endpoint per outcome, the primary endpoint identified by the authors was extracted. Where no primary endpoint was identified by the authors, the measures were ranked by effect size and we extracted the median measure (Curran 2007). Measures of physical activity or sedentary behaviour that were based upon meeting a national standard were noted and the potential for unequal comparisons identified. We collected information on how physical activity was reported, that is whether it was through self‐report in a telephone survey or devices such as pedometers. Data extracted independently by the review authors were compared and any differences were resolved through discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Only studies that met the inclusion criteria were assessed and reported in a risk of bias table as per the recommendation of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008).

Two review authors (PB and one other author) assessed the risk of bias for each study. Analysis of non‐randomised controlled trials followed the recommendations in Chapter 13 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Where there was disagreement between review authors in risk of bias assessment, this was resolved by discussion and consensus.

Studies were assessed for the five general domains of bias: selection, performance, attrition, detection, and reporting, as well as for an additional category to capture any other concerns pertaining to the study quality that did not fit distinctly into either of the five domains. For example, this additional category included instances where the statistical analyses presented in the included study were problematic and failed to adjust for baseline differences between the control and intervention groups, or failed to address what appeared to be regression to the mean. This category was also applicable if there appeared to be a 'head‐start' or other advantage for the intervention community. Each was assessed with answers of 'Yes' indicating low risk of bias, 'No' indicating high risk of bias, and 'Unclear' indicating either lack of information or uncertainty over the potential for bias. Studies were judged overall as at 'low', 'unclear' or 'high' risk of bias after consideration of the study design and size, and the potential impact of the identified weaknesses noted in the table for each study.

Specifically, assessment of performance bias included identification of explicit statements of measures undertaken to avoid contamination (that can occur when the control group also receives the intervention) such as spatial separation, non‐delivery of the program to the control communities, and minimisation of wide‐reaching mass media. We also considered measurement of the community's awareness of the message obtained through community surveys, both of the intervention and control communities. Additionally, integrity of the intervention was considered and performance bias was assessed as being present when the study's process evaluation (perhaps an additional publication) described instances where the program was not delivered as planned.

Studies were assessed as at high risk of detection bias when incomplete data were inadequately defined or, particularly in cross‐sectional sampling, where the characteristics of the follow‐up groups varied significantly from the baseline groups.

Detection bias was assessed to be at low risk where measurement tools were used in their entirety, the outcome assessment was blind (if deemed appropriate), the outcome measure metrics were valid, the measure was of sufficient quality (for example assessed over the period > one day) and the sample was representative (for example random sampling of the community).

Reporting bias was assessed as being at low risk if the reports appeared to be free from selective reporting and the measures reported were complete and matched the aims of the studies. Studies where follow‐up measurement was absent, or appeared to be deliberately withheld, were assessed as at high risk of reporting bias.

The review authors determined a priori that the best evidence (both contextually relevant and representing the purpose of the intervention) was likely to come from cluster RCTs and CBA studies. Although this differs from the usual evidence hierarchy (NHMRC 1999) (which emphasises RCTs for assessment of interventions), it is considered a better approach than the problematic application of the usual criteria when appraising the evidence for social and public health interventions (Petticrew 2003).

Measures of intervention effect

The effect sizes for dichotomous outcomes were expressed as relative risk (RR) and risk difference (RD) in the first instance. For comparability across studies, given the important baseline differences between intervention (I) and control (C) groups, we calculated from the authors' data an adjusted estimate of effect based on the differences at baseline. Therefore, for dichotomous outcomes we calculated the following.

1. Net percentage change from baseline = ((Ipost ‐ Ipre)/Ipre) ‐ ((Cpost ‐ Cpre)/Cpre) x 100.

2. Adjusted risk difference = (Ipost ‐ Ipre) ‐ (Cpost ‐ Cpre).

3. Adjusted relative risk = (Ipost / Cpost)/(Ipre/Cpre).

Confidence intervals (95%) were calculated using the Wald test.

For continuous outcomes we calculated the following from the authors' data.

1. Post mean differences (PMD) = Imeanpost ‐ Cmeanpost

2. Adjusted mean difference = [(Imeanpost ‐ Cmeanpost) ‐ (Imeanpre ‐ Cmeanpre)]

3. Adjusted percentage change relative to the control group = [((Imeanpost ‐ Cmeanpost) ‐ (Imeanpre ‐ Cmeanpre))/Cmeanpost] x 100.

The 95% confidence intervals could not be calculated using this approach.

Unit of analysis issues

Studies allocated by clusters that did not account for clustering during analysis were not re‐analysed. This was because these studies were not randomised and there was only a small number of clusters, and so clustering would have a minimal effect.

Dealing with missing data

Protocols and baseline publications for the studies were used to identify outcome data that were expected to be present in the follow‐up report which presented the outcomes. Incomplete data (that is less than 40% of data) were assessed during the risk of bias assessment. Data that appeared to be completely absent were noted as reporting bias. Missing data were also captured in the data extraction form and reported in the risk of bias table. The authors were contacted to try and acquire missing data for inclusion. In some instances this included the use of a Chinese speaking epidemiologist.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Due to heterogeneity in the study designs employed, the populations in which the interventions were conducted, and the interventions themselves no meta‐analysis was conducted.

Assessment of reporting biases

We considered plotting trial effect against standard error and presenting this in a funnel plot (Higgins 2008) to determine whether asymmetry could be caused by a relationship between effect size and sample size or by publication bias (Egger 1998). However, we decided against doing this given the high risks of bias in the data and the poor quality of measurement undertaken in the studies.

Intensity of intervention

We categorised the intensity of the community wide intervention to assess whether intensity could account for differences that existed in the outcomes between studies. The intensity of the intervention was categorised based on the following six characteristics and attributes that we hypothesised would be important in understanding differences in the effectiveness of the community wide intervention; two review authors (PB and DF) independently assessed each characteristic as 'more intensive', 'less intensive' or 'unclear':

development of community partnerships and coalition (first level of the logic model ‘Community/Strategy Development’), showing evidence of engaging stakeholders and building a community coalition;

levels of intervention (second level of the logic model ‘Implementation’), intervening at the individual (personal), social (interpersonal) and environmental (physical and legislative) levels;

reach of the strategies (second level of the logic model), the intervention reaches the whole of the community, multiple sectors of the community, targets subgroups, with awareness > 85%;

magnitude of the intervention, the extent of continuous provision of the intervention through the intervention period (volume of the intervention): frequency and duration of strategies, with high intensity typified as sustained integration of the intervention;

description of cost, where stated the cost per person for the intervention (excluding the evaluation) in the context of the year and the location, presumably indicating the magnitude of the intervention;

statement of intensity by the authors, descriptors found within the studies where the investigators themselves used descriptors such as 'high impact' or 'significant cost'.

We categorised the overall assessment of intensity for each study as 'high', 'medium', 'low', or 'unclear'. Given that the six categories we assessed on were not distinct, and the sufficiency of detail varied between the studies, each review author independently made the overall assessment using subjective informed determination rather than a predefined algorithm. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

Data synthesis

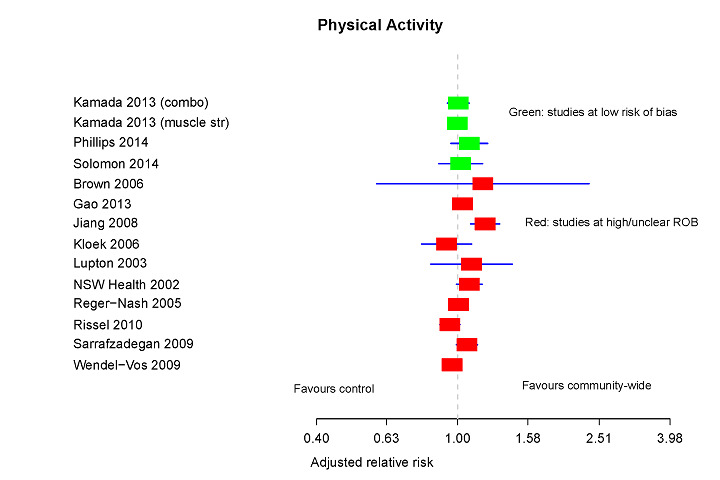

Continuous outcomes were reported on the original scale. where possible. We predetermined we would undertake a meta‐analysis only when data were clinically homogeneous. We followed Chapter 9: 'Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analyses' of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). As data were not available that were sufficiently similar and of sufficient quality, a meta‐analysis was not performed. We predetermined that evidence from differing study designs and outcome types was not to be combined in a forest plot from standard meta‐analysis (Christinsen 2009). However, to identify trends and provide summary statements, simple forest plots were generated for three dichotomous outcomes (% physically active, % physically active during leisure time and % physically inactive).

Subgroup analysis

We predetermined that, where sufficient data were available, we would perform additional subgroup analyses to compare outcomes by: types of study designs; group effects for people who shared a common social, cultural, or health status characteristic (for example age, gender, ethnicity); reach of intervention and intensity of intervention (derived from use of the logic model and process evaluations). We had intended that a subgroup analysis would be used to explore whether there was likely to be a relationship of effect to disadvantage and whether an equity gradient was present. Given the limitations of the data, both in their quality and the absence of subgroup reporting, no further subgroup analysis could be undertaken.

Sensitivity analysis

The studies with low risk of bias have been grouped in the forest plots.

Summary of findings

We had intended to undertake a summary of findings table for the primary outcomes related to physical activity and sedentary behaviour using GRADE profiler (Cochrane IMS 2009). This was to be created using the measures for the primary outcomes identified as being most reliable and which predominated. Given that very few studies had reliable measures of physical activity and sedentary behaviour, and much of the data were incomplete, a modified approach was required in which we split the presentation of findings according to the risk of bias. We considered the primary challenge that all the community wide interventions were different and all of the communities unique and thus caution was required in potentially homogenising very different approaches. As conducting meta‐analyses was deemed inappropriate, a summary table has been prepared using narrative analysis of the included studies.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

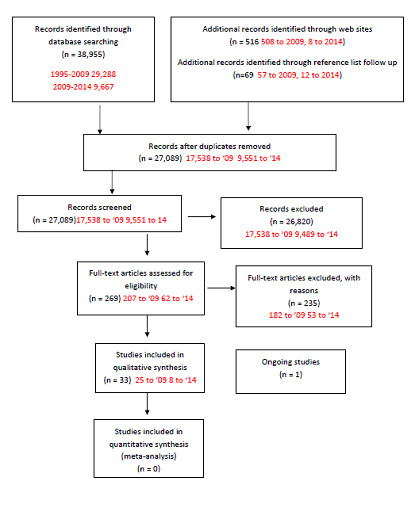

Electronic searches from 1995 to November 2009, in the original review, yielded 17,538 hits following removal of duplicates (Figure 2), of which 207 were considered potentially eligible and were assessed in full text. The update search, to January 2014, identified an additional 9551 hits following removal of duplicates (Figure 2), of which 62 were considered potentially eligible and assessed in full text. The results of the searches of the electronic databases and websites are found in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. The full search strategies, dates, and number of hits are given in Appendix 1. Twenty‐five studies were included in the original review (Brown 2006; Brownson 2004; Brownson 2005; De Cocker 2007; Eaton 1999; Goodman 1995; Gu 2006; Guo 2006; Jenum 2006; Jiang 2008; Kloek 2006; Kumpusalo 1996; Luepker 1994; Lupton 2003; Nafziger 2001; Nishtar 2007; NSW Health 2002; O'Loughlin 1999; Osler 1993; Reger‐Nash 2005; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Simon 2008; Wendel‐Vos 2009; Young 1996; Zhang 2003). Eight additional studies were identified in the update search (Gao 2013; Kamada 2013; Mead 2013; Nguyen 2012; Phillips 2014; Rissel 2010; Solomon 2014; Wilson 2014) resulting in a total of 33 included studies. We identified one study for which there is no published conclusion and have identified it as 'ongoing' (Davey 2011).

2.

PRISMA diagram based upon Moher 2009.

1. Search results for electronic databases.

| Database | Number of hits |

| ASSIA | 1144 |

| British Nursing Index (BNI) | 105 |

| CINAHL | 2881 |

| Chinese atabase:CAJ,CCND,CPCD,CJSS,CMFD,CDFD, http://www.global.cnki.net/grid20/index.htm | 124 |

| Cochrane Library | 1841 |

| Cochrane Public Health Group Specialized Register | 31 |

| EMBASE | 4941 |

EPPI Centre

|

38 200 |

| ERIC | 416 |

| Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) | 308 |

| LILACS | 416 |

| MEDLINE & MEDLINE In‐Process | 5691 |

| PsycINFO | 1315 |

| Sociological Abstracts | 874 |

| SPORTDiscus | 365 |

| Transport Database TRIS | 49 |

| Web of Science Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index |

9108 |

2. Search results for websites.

| Web sites | Hits |

| EU Platform on Diet, Physical Activity and Health | 0 |

| http://health‐evidence.ca | 5 |

| IUHPE (International Union for Health Promotion and Education) | 0 |

| NCCHTA http://www.ncchta.org | 1 |

| NICE guidelines http://www.nice.org.uk | 4 |

| SIGN guidelines http://www.sign.ac.uk | 0 |

| US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention http://www.cdc.gov/ | 0 |

| World Health Organisation http://www.who.int/en/ | 1 |

Included studies

Communities in the included studies

Twenty‐five of the included studies were set in high income countries (using the World Bank economic classification). Of these, 11 studies were conducted in North America (Brownson 2004; Brownson 2005; Eaton 1999; Goodman 1995; Luepker 1994; Mead 2013; Nafziger 2001; O'Loughlin 1999; Reger‐Nash 2005; Wilson 2014; Young 1996), three in Australia (Brown 2006; NSW Health 2002; Rissel 2010), one in Japan (Kamada 2013) and 10 in Europe (De Cocker 2007; Jenum 2006; Kloek 2006; Kumpusalo 1996; Lupton 2003; Osler 1993; Phillips 2014; Simon 2008; Solomon 2014; Wendel‐Vos 2009). Of the remaining eight studies, two were set in lower middle income countries: one in Pakistan (Nishtar 2007) and one in Vietnam (Nguyen 2012); and six were set in upper middle income countries: five in China (Gao 2013; Gu 2006; Guo 2006; Jiang 2008; Zhang 2003) and one in Iran (Sarrafzadegan 2009).

A total of 267 communities were included in the review. The size of the community in which the intervention took place varied greatly, from two small villages with a total population of less than 1000 inhabitants (Kumpusalo 1996) and clusters of villages greater than 500 (Solomon 2014) to a large region with a population of 1,895,856 (Sarrafzadegan 2009). Similarly, the location of the communities varied with 12 studies taking place in what could be considered rural or remote settings and the remaining 21 studies located in urban centres or cities.

Interventions in included studies

When assessed against the six categories, we found substantial differences in the combinations of interventions used in the included studies. Almost all of the interventions included a component of building partnerships with local governments or non‐government organisations (NGOs) (29 studies). Other strategies used in the interventions included some form of individual counselling by health professionals (20 studies), mass media campaigns (23 studies) or other communication strategies (26 studies). Some studies were delivered in specific settings (18 studies) and used environmental change strategies (14 studies).

Only four interventions that were investigated by the included studies contained elements of all six of the components described in the inclusion criteria (Brown 2006; Gao 2013; Goodman 1995; Luepker 1994) (see Methods section). Three interventions were comprised of five components, 10 of four components, seven of three components and two of two components (Table 4).

3. Categories of strategies included in interventions.

| Study | Mass Media | Other communication | Individual | Partnerships | Settings | Environmental | Total |

| Brown 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 |

| Brownson 2004 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Brownson 2005 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| De Cocker 2007 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Eaton 1999 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Gao 2013 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 |

| Goodman 1995 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 |

| Gu 2006 | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Guo 2006 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Jenum 2006 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Jiang 2008 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Kamada 2013 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Kloek 2006 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Kumpusalo 1996 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Luepker 1994 | X | X | X | X | X | X | 6 |

| Lupton 2003 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Mead 2013 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Nafziger 2001 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Nguyen 2012 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Nishtar 2007 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| NSW Health 2002 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| O'Loughlin 1999 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Osler 1993 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Phillips 2014 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Reger‐Nash 2005 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Rissel 2010 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Sarrafzadegan 2009 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Simon 2008 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Solomon 2014 | X | X | X | X | X | 5 | |

| Wendel‐Vos 2009 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Wilson 2014 | X | X | X | X | 4 | ||

| Young 1996 | X | X | X | 3 | |||

| Zhang 2003 | X | X | 2 | ||||

| Total | 23 | 26 | 20 | 29 | 18 | 14 |

2 components ‐2 studies; 3 components ‐ 10 studies; 4 components ‐ 13 studies; 5 components ‐ 4 studies; 6 components ‐ 4 studies.

See Types of interventions for examples of suitable strategies which would be components of an integrated community wide strategy

Theoretical perspectives

Interventions were developed from a variety of theoretical perspectives, although many studies did not identify any such perspective in their papers. Nine of the studies sought to increase physical activity in a community by developing an intervention based on an ecological approach (Brown 2006; Brownson 2004; Brownson 2005; De Cocker 2007; Gao 2013; Jenum 2006; Mead 2013; Simon 2008; Wilson 2014). Six studies developed interventions with the stages of change model as their guiding framework (Kamada 2013; Kloek 2006; Luepker 1994; Phillips 2014; Reger‐Nash 2005; Rissel 2010) while four studies used the social learning model (Eaton 1999; Luepker 1994; O'Loughlin 1999; Osler 1993). Two studies used the community empowerment model for developing their interventions (Jenum 2006; Lupton 2003). Other theoretical approaches used included behaviour change of self‐efficacy (O'Loughlin 1999), persuasive communications theory (Luepker 1994), social cognitive theory (Mead 2013), active friendly environments (Solomon 2014), social marketing (Rissel 2010; Wilson 2014) and community organisation principles (Kloek 2006; Osler 1993). Of note, a number of studies described basing their interventions or components of interventions on multiple models. However, 11 did not explicitly state a theoretical model (Goodman 1995; Gu 2006; Guo 2006; Jiang 2008; Nafziger 2001; Nishtar 2007; NSW Health 2002; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Solomon 2014; Young 1996; Zhang 2003).

Intensity of Interventions

A subjective assessment of the intensity of each intervention was conducted based on the consideration of six criteria, as described in the methods section. Ten studies were judged to be high intensity, 14 of medium intensity and nine of low intensity (Table 5). The categorisation of high intensity was typically assigned to an intervention which acted on multiple levels within a community via multiple strategies as understood by the logic model (Figure 1). For example, the Brown 2006 study used mass media as well as other forms of communication to increase awareness of physical activity. The study also promoted self monitoring and goal setting using a website and provided access for individuals to pedometers and logbooks. Counselling by health professionals was another mode of intervention and a number of setting‐specific initiatives were conducted. The investigators also collaborated with the local government in improving the environment for physical activity by repairing walking tracks and creating signage and maps. Importantly, this intervention had the express intent of increasing the physical activity of the whole population, whereas some interventions included in this review targeted a range of behaviours other than physical activity. O'Loughlin 1999 was one such study which, with quite a modest budget (when compared to some of the larger interventions), employed multiple strategies in targeting smoking and diet along with physical activity. Given these factors it was considered to be of moderate intensity.

4. Assessment of intensity of the interventions.

| Study | High | Medium | Low | Unclear |

| Brown 2006 | X | |||

| Brownson 2004 | X | |||

| Brownson 2005 | X | |||

| De Cocker 2007 | X | |||

| Eaton 1999 | X | |||

| Gao 2013 | X | |||

| Goodman 1995 | X | |||

| Gu 2006 | X | |||

| Guo 2006 | X | |||

| Jenum 2006 | X | |||

| Jiang 2008 | X | |||

| Kamada 2013 | X | |||

| Kloek 2006 | X | |||

| Kumpusalo 1996 | X | |||

| Luepker 1994 | X | |||

| Lupton 2003 | X | |||

| Mead 2013 | X | |||

| Nafziger 2001 | X | |||

| Nguyen 2012 | X | |||

| Nishtar 2007 | X | |||

| NSW Health 2002 | X | |||

| O'Loughlin 1999 | X | |||

| Osler 1993 | X | |||

| Phillips 2014 | X | |||

| Rissel 2010 | X | |||

| Reger‐Nash 2005 | X | |||

| Sarrafzadegan 2009 | X | |||

| Simon 2008 | X | |||

| Solomon 2014 | X | |||

| Wendel‐Vos 2009 | X | |||

| Wilson 2014 | X | |||

| Young 1996 | X | |||

| Zhang 2003 | X | |||

| Total | 10 | 14 | 9 | 0 |

Intensity was assessed subjectively and independently based upon six characteristics as described in Data collection and analysis

The interventions studied by Gu 2006, Jiang 2008 and Zhang 2003 reached every individual in their target communities through quite substantial contacts such as repeated door‐to‐door visitation and health screening. The extensive reach of the intervention, combined with what was a potentially significant dose, led to their classification as high intensity interventions despite them being very different to Brown 2006. Conversely, most of the interventions judged as being of low level intensity had a much poorer reach into the communities. Indeed, several of the studies judged as being of low intensity were described by their authors as being of low intensity or low cost (Osler 1993; Simon 2008). In the case of Osler 1993, the low cost of the intervention was demonstrated in the limited amount of activity that took place compared to the more intense interventions. Similarly, Simon 2008 was judged as a low intensity intervention as, while it aimed to reach the whole community, the vast majority of its activities were targeted at one section of the community (in this case adolescents attending school). Overall, some studies appeared to have good reach (Gao 2013) whilst others (Solomon 2014) identified that very few residents were even aware of, and participated in, the intervention. Several of the studies provided descriptions of people participating in the components.

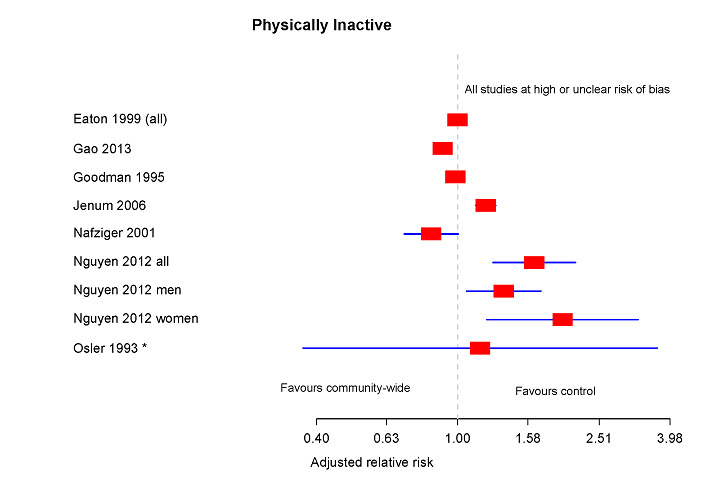

Outcome measures

To be included in the review, the study had to include a measurement of physical activity. A variety of dichotomous and continuous outcomes were used in these studies. Thirteen studies reported the proportion of participants attaining a certain level of physical activity (Brown 2006; Gao 2013; Jiang 2008; Kamada 2013; Kloek 2006; Lupton 2003; NSW Health 2002; Phillips 2014; Reger‐Nash 2005; Rissel 2010; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Solomon 2014; Wendel‐Vos 2009). The inverse of these outcomes was the reporting of the proportion of participants who were physically inactive, that is failing to attain a defined level of physical activity (Eaton 1999; Gao 2013; Goodman 1995; Jenum 2006; Nafziger 2001; Nguyen 2012; Osler 1993). Three other studies also reported the percentage of participants attaining a certain level of physical activity but prescribed that this had to have taken place during leisure time (Kumpusalo 1996; Luepker 1994; Nishtar 2007).

Time spent being physically active during leisure time (for example as hours per week) was also reported as a continuous outcome in three studies (De Cocker 2007; Simon 2008; Wendel‐Vos 2009). Other continuous outcomes of physical activity reported in the included studies included walking (Brownson 2004; Brownson 2005; De Cocker 2007; Wendel‐Vos 2009), energy expenditure (Kloek 2006; Phillips 2014; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Solomon 2014) and minutes in moderate‐vigorous physical activity each day (Wilson 2014).

Most of the included studies also measured other behaviours and health outcomes related to chronic disease. Behaviours measured included smoking, alcohol consumption, fruit and vegetable intake, fat and junk food intake and BMI. Other studies included speciality activity measures such as percentage of persons cycling. Knowledge and attitudes towards physical activity and health knowledge were reported in some studies. Health outcomes measured included chronic disease such as diabetes and hypertension, obesity and laboratory measures such as vitamin C, plasma and cholesterol levels. Reviewing the findings of these measures was not the objective of this review and so they have not been explored here.

Excluded studies

The Excluded studies table lists the studies that were excluded and the determined reasons. In several cases the studies were excluded for more than one reason. The predominant reasons for studies being excluded at this stage of the selection process were the study design (n = 84) or the intervention (n = 83) not meeting the inclusion criteria. In 42 cases the study was not designed in a way which could target the entire community, and in 28 cases the population sampled was not inclusive. In one case the study described the intervention without providing any results, in one case the report was inadequate and in five the measurement of physical activity was absent (deemed not likely to be the result of selective reporting of outcomes bias).

Risk of bias in included studies

The update has noted the increased use of randomisation in the allocation procedure and a significant improvement in the study design methodology from earlier studies. Earlier, all of the included studies were described as controlled before and after studies with the exception of one controlled ITS study (Luepker 1994) and one cluster cohort study (O'Loughlin 1999). Although the original review contained only one cluster RCT (Simon 2008), the updated review now includes an additional four RCTs: three cluster randomised studies (Kamada 2013; Phillips 2014; Wilson 2014) and one stepped wedge cluster randomised trial (Solomon 2014). This should be clearly understood as a change in the methodological approach of evaluation of community wide interventions. Each of these studies used a random selection of participants (representative sample) from the communities to participate in the measurement of outcomes.

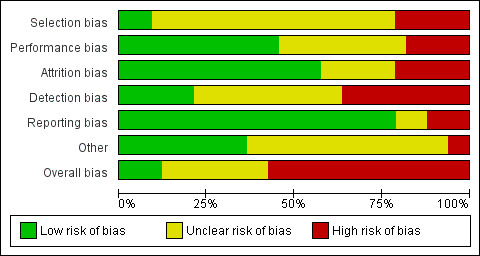

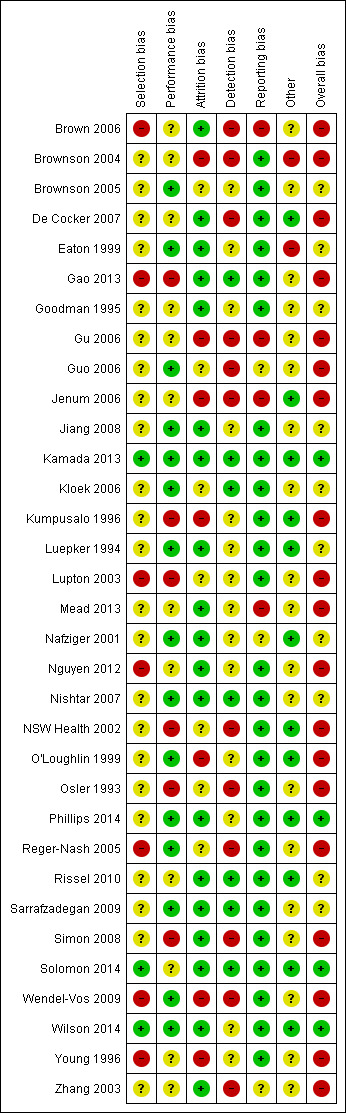

All included studies were assessed for their risk of bias. Graphical presentation of the results of the risk of bias assessments of the individual studies and of the overall body of evidence are found in Figure 3 and Figure 4. In the earlier review no studies were identified as low risk of bias, however in this update four of the eight studies have been identified as low risk (Kamada 2013; Phillips 2014; Solomon 2014; Wilson 2014). Overall, 19 studies were identified as being at a high risk of bias (Brown 2006; Brownson 2004; De Cocker 2007; Gao 2013; Gu 2006; Guo 2006; Jenum 2006; Kumpusalo 1996; Lupton 2003; Mead 2013; Nguyen 2012; NSW Health 2002; O'Loughlin 1999; Osler 1993; Reger‐Nash 2005; Simon 2008; Wendel‐Vos 2009; Young 1996; Zhang 2003). Ten studies were found to have an unclear risk of bias (Brownson 2005; Eaton 1999; Goodman 1995; Jiang 2008; Kloek 2006; Luepker 1994; Nafziger 2001; Nishtar 2007; Rissel 2010; Sarrafzadegan 2009). Of those studies judged as at either high or unclear risk of bias only one of the studies was randomised, thus selection bias was a major risk for these studies. This was exacerbated as many of these studies only included one measurement point pre‐intervention and one post‐intervention, and in a number of the studies there were differences in important baseline characteristics between the study groups. We observed minor methodological deviations such as a change in the method of application of the survey questions from baseline to follow‐up (for example Phillips 2014). Where a singular minor methodological issue occurred which was deemed unlikely to change interpretation of the findings, we determined that an overall downgrading of the study to high risk was unwarranted.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

For the studies deemed to be low risk, allocation to the intervention and control occurred by randomisation (for example cluster RCT) rather than by purposeful allocation of the intervention community to communities which had the capacity to undertake the intervention rather than those which did not, such as Gao 2013. Non‐randomised controlled trials could also have been assessed as lower risk if the measurement was repeated pre and post‐intervention (to determine whether the changes were a result of trends toward the mean or the result of imprecision of the outcome measures). Low risk studies used measurement metrics that were both valid and reliable for population level interventions, avoided subjective self‐report assessment, and typically made over more than one day. Further, the individuals sampled should be representative of the population and include those difficult to reach. Studies at low risk of bias should, in the publication of results, include all of the measures stated in the study protocol and all of those reported in the initial publication of the study.

Selection bias

Selection bias was a major concern in the earlier review as only one study used randomisation to allocate communities (Simon 2008). Previously, no studies were judged as being at low risk of selection bias, although 19 studies were considered to have an unclear risk of bias (if the groups were comparable at baseline for important potential confounders; and if the assessors judged that if the communities were reversed it was likely that the same outcome would be achieved) (Brownson 2004; Brownson 2005; De Cocker 2007; Eaton 1999; Goodman 1995; Gu 2006; Guo 2006; Jenum 2006; Jiang 2008; Kloek 2006; Luepker 1994; Nafziger 2001; Nishtar 2007; NSW Health 2002; O'Loughlin 1999; Osler 1993; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Simon 2008; Zhang 2003). In this update, two of the new studies were identified as being at high risk of selection bias (Gao 2013; Nguyen 2012) and three unclear (Mead 2013; Phillips 2014; Rissel 2010). Four new randomised studies were considered to be at low risk of selection bias (Kamada 2013; Solomon 2014; Wilson 2014).

Performance bias

Collectively, 15 studies were judged as having a low risk of performance bias (Brownson 2005; Eaton 1999; Guo 2006; Jiang 2008; Kamada 2013; Kloek 2006; Luepker 1994; Nafziger 2001; Nishtar 2007; O'Loughlin 1999; Phillips 2014; Reger‐Nash 2005; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Wendel‐Vos 2009; Wilson 2014). While information on the blinding of communities was rare, these studies were judged as being at low risk of contamination and provided evidence of good integrity in the delivery of the intervention even though in some circumstances the intervention was clearly weak.

Attrition bias

Nineteen studies were assessed as being at low risk of attrition bias (Brown 2006; De Cocker 2007; Eaton 1999; Gao 2013; Goodman 1995; Jiang 2008; Kamada 2013; Luepker 1994; Mead 2013; Nafziger 2001; Nguyen 2012; Nishtar 2007; Phillips 2014; Rissel 2010; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Simon 2008; Solomon 2014; Wilson 2014; Zhang 2003). Potential for attrition bias was often not applicable through the cross‐sectional sampling of different individuals as representatives of the same population rather than following specific individuals through time. Some cohort studies had very high completion rates possibly related to recruitment intention of being resident in the community for the duration of the study (Mead 2013; Rissel 2010). There were no cases of communities withdrawing from the studies.

Detection bias

Twelve studies had a high risk of detection bias, 14 an unclear risk and 7 were low risk (Gao 2013; Kamada 2013; Kloek 2006; Nishtar 2007; Rissel 2010; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Solomon 2014). Assessment of detection bias included an assessment of the validity of the measurement tools and the quality of the outcome measures. In this update, one study used accelerometers to objectively measure physical activity.

Reporting bias

Four studies had a high risk of reporting bias (Brown 2006; Gu 2006; Jenum 2006; Mead 2013), with three assessed as being unclear (Guo 2006; Nafziger 2001; Zhang 2003) and 26 as low risk of bias. In the studies judged as having a high risk of reporting bias, there was evidence to indicate that outcomes important to the study were collected but not reported (as confirmed through communication with the authors). Ideally, access to study protocols would help with the process of accessing reporting bias, however in most cases this was not possible. Some studies did publish papers describing the intervention and evaluation methods prior to the final evaluation of the study thus enabling some scrutiny of reporting bias. Some studies with negative findings provided limited reporting of the outcomes and a preference towards the higher quality measurement instruments (for example Phillips 2014; Wilson 2014); however, with no likely impact upon the conclusions we determined them low risk for reporting bias.

Other bias

One study was judged as being at high risk of other bias (Brownson 2004), having had a 'head‐start' with several years of preparation in the intervention community prior to the program start, which was deemed to provide it with an advantage. The effect of this bias was unpredictable as it could have resulted in a null effect or been an effect modifier.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Physical activity, dichotomous outcomes

Twenty‐seven studies reported physical activity as some form of dichotomous measure.

Fourteen studies reported physical activity measured as the attainment of a predefined amount of physical activity (Brown 2006; Brownson 2005; Gao 2013; Jiang 2008; Kamada 2013; Kloek 2006; Lupton 2003; NSW Health 2002; Phillips 2014; Reger‐Nash 2005; Rissel 2010; Sarrafzadegan 2009; Solomon 2014; Wendel‐Vos 2009) (Table 6; Figure 5). Only two of these studies, both based in China, found the intervention to be collectively effective across the whole population, in an intense intervention in urban Beijing (Jiang 2008) and Hangzhou China (Gao 2013). Lupton 2003 and Brown 2006 found the interventions to be effective in the male and female populations of the targeted communities respectively. The remaining studies found no evidence of effect.

5. Dichotomous outcomes ‐ physical activity.

| Study | Overall bias | Measure | Definition | Net % change | Unadjusted RD | Adjusted RD (95% CI) | Unadjusted RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Baseline |

| Brown 2006 | High risk of bias | % physically active | 150 minutes of activity in at least 5 separate sessions in the last week | 15.40 | 0.9 | 7.33 (‐23.48 ‐ 38.13) | 1.02 | 1.18 (0.60 ‐ 2.35) | 41.9 |

| Gao 2013 | High risk of bias | % Moderate or high physically active | Categories on IPAQ | 3.34 | 7.4 | 2.50 (1.17 ‐ 3.83) | 1.10 | 1.03 (1.01 ‐ 1.05) | 70.5 |

| Jiang 2008 | Unclear risk of bias | Regular physical activity | Not provided | 18.12 | 6.38 | 10.75 (5.23 ‐ 16.27) | 1.24 | 1.20 (1.09 ‐ 1.31) | 60.39 |

| Kamada 2013 | Low risk of bias | % physically active | Engaging in 150mins/week or more of walking, engaging in daily flexibility or engaging in 2 or more days a week of in muscle strengthening activities (All groups vs. control) |

‐0.17 | ‐1.6 | 0.00 (0.0‐0.0) | 0.973 | 1.00 (0.99‐1.00) | 63.0 |

| Low risk of bias | % physically active | Engaging in 150mins/week or more of walking, engaging in daily flexibility or engaging in 2 or more days a week of in muscle strengthening activities (Aerobic exercise group vs. control) |

‐2.80 | 0.000 | ‐2.0 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 66.6 | |

| Low risk of bias | % physically active | Engaging in 150mins/week or more of walking, engaging in daily flexibility or engaging in 2 or more days a week of in muscle strengthening activities (Aerobic exercise and strengthening group vs. control) |

0.41 | ‐0.3 | 0.30 (‐4.56 ‐ 5.16) | 1.00 | 1.00 (0.94 ‐ 1.08) | 64.0 | |

| Kloek 2006 | Unclear risk of bias | % physically active | At least 30 minutes of moderate‐intensity physical activity on at least 5 days a week | ‐7.36 | ‐1 | ‐3.97 (5.02 ‐ ‐12.95) | 1.04 | 0.93 (0.79 ‐1.10) | 59.0 |

| Lupton 2003 | High risk of bias | % physically active | Minimum of four hours of weekly moderate PA during the last year | 9.84 | 8.3 | 6.87 (‐13.04 ‐ 26.78) | 0.98 | 1.10 (0.84 ‐ 1.43) | 72.5 |

| NSW Health 2002 | High risk of bias | % physically active | Engaged in at least 150 minutes and five sessions of moderate activity or three sessions of vigorous activity per week | 7.14 | ‐0.2 | 3.39 (‐0.29 ‐ 7.08) | 1.14 | 1.08 (0.99 ‐ 1.17) | 49.2 |

| Phillips 2014 | Low risk of bias | % meeting | Physical activity: 5x30 minutes per week | 7.89 | 1.9 | 5.00 (‐2.879 ‐ 12.879) | 1.029 | 1.079 (0.957 ‐ 1.216) | 63.4 |

| Reger‐Nash 2005 | High risk of bias | % physically active | Moderate activity at least 30 minutes for at least 5 days per week or vigorous activity at least 20 minutes for at least 3 days per week | 0.36 | 1.2 | 0.38 (‐0.06 ‐ 0.82) | 1.15 | 1.01 (0.10 ‐ 1.01) | 46.9 |

| Rissel 2010 | Unclear risk of bias | % physically active | undertaking 150 min/week | ‐5.55 | ‐5.0 | ‐2.8(‐6.47 ‐ 0.873) | 0.907 | 0.951 ( 0.891 ‐1.015) | 44.9 |

| Sarrafzadegan 2009 | Unclear risk of bias | % physically active | Individuals with >= 30 minutes/day of moderate or vigorous activity | 4.17 | 2.1 | 1.89 (‐0.23 ‐ 4.02) | 1.07 | 1.06 (1.00 ‐ 1.14) | 47.0 |

| Solomon 2014 | Low risk of bias | % physically active | Did sufficient physical activity to meet the current United Kingdom physical activity guidelines (at least 150 minutes of moderate‐intensity activity per week in bouts of 10 minutes or more, or at least 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity per week | 1.03 | NA | NA | NA | 1.02 (0.88 ‐ 1.17)† | 66.9 |

| Wendel‐Vos 2009 | High risk of bias | % physically active | 150 min/week and at least 5 sessions per week, and physically active at least 30 min/day at least 5 days a week | ‐3.50 | ‐0.7 | ‐1.60 (‐0.10 ‐ ‐3.10) | 0.86 | 0.97 (0.93 ‐ 1.00) | 42.8 |

RD = Risk difference

RR = Relative Risk

† Data as presented by the study authors. Odds ratio of adjusted comparison (Intervention minus control in stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled design, p‐value = 0.80, ICC 0.008. Baseline represents baseline for all..

5.

Forest plot of dichotomous outcomes of meeting a criteria of being physically active ‐ mixed measures and study designs by risk of bias.

Jiang 2008 reported an increase in regular physical activity (we calculated an adjusted RR 1.20, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.31) for an intervention involving intensive contact with individuals in urban communities in Beijing. The intervention had very substantial penetration into the community with quarterly door‐to‐door distribution of handouts, counselling by health practitioners, and the identification of those within the community with high risk factors through an intensive individual screening campaign in which 73% of the community participated. Gao 2013 also reported a small but statistically significant increase (adjusted RR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.05). This intervention was a multi‐component high intensity intervention and the study was at high risk of bias as the authors allocated communities to the control arm which did not have the capacity to support the intervention.

The Finnmark Intervention study (Lupton 2003) aimed at improving cardiovascular health in a small arctic community in Norway, and reported a significant increase (P = 0.047) in males being physically active, as defined as accruing a minimum of four hours of moderate physical activity over a week during the last year. This was measured six years after the initial baseline measurement and commencement of an intervention which involved the engagement of the community largely through activities run by sporting clubs and associations. Unfortunately, no significant change was found in the female population (P = 0.151) as reported by the authors and the calculated adjusted RR for the entire population was non‐significant (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.43).

Conversely, the Rockhampton 10,000 Steps Project conducted in a regional Australian community found an increase in the proportion of physically active females (achieving 150 minutes of activity in at least five separate sessions over the last week) but not males (Brown 2006). The interpretation of these findings was complicated as the control community was significantly more active than the comparison community at baseline (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.93). At follow‐up, two years later, there was no longer a significant difference with the percentage of the comparison community categorised as being active decreasing by 6.4% while the intervention community increased 0.9%. Combined, there was once again no difference between the two populations (adjusted RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.60 to 2.35).

No evidence of effectiveness was found in the three studies at low risk of bias. Phillips 2014 found no increase in the percentage of people meeting the target of 5 x 30 minutes per week (adjusted RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.96 to 1.22) and, similarly, Solomon 2014 did not find an increase in the percentage meeting the UK recommendation of at least 150 minutes of moderate‐intensity activity per week in bouts of 10 minutes or more, or at least 75 minutes of vigorous‐intensity activity per week (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.17). Further, in Japan Kamada 2013 in three comparisons, controlled versus muscle strengthening versus aerobic activity versus combined, found no statistical increases in either arm of the intervention analysed (adjusted RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.00; RR 0.97 (confidence interval could not be calculated); RR 1.00 95% CI 0.94 to 1.10).

The Isfahan Healthy Heart program aimed to improve the health of a large population (> two million) through a multi‐strategic, large scale intervention (Sarrafzadegan 2009). The adjusted RR of 1.06 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.14) suggested a small increase in the percentage of the population with greater than, or equal to, 30 minutes per day of moderate or vigorous activity, although this was not found to be statistically significant. This result needs to be understood in the context of a decreasing trend in physical activity in both the intervention and comparison groups. Further, for the continuous outcome energy expenditure, a decrease was observed.

Wendel‐Vos 2009 reported no effect on the percentage of participants meeting the study's target of 150 minutes per week and at least five sessions per week in the Maastricht region of the Netherlands, following a large five‐year project aiming to improve individuals' chronic disease risk factors (adjusted RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.0). Also, targeting several health‐related behaviours, Kloek 2006 reported on an intervention targeting socioeconomically deprived neighbourhoods in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. No effect was found on the proportion of the population attaining at least 30 minutes of moderate‐intensity physical activity on at least five days in a week (adjusted RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.10).

In investigating a mass media dominated intervention aimed at increasing walking behaviour, Reger‐Nash 2005 found no effect on moderate activity of at least 30 minutes for at least five days per week or on vigorous activity for at least 20 minutes on at least three days per week (adjusted RR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.01).

NSW Health 2002 reported no statistically significant effects on physical activity, defined as those individuals engaged in at least 150 minutes and five sessions of moderate activity or three sessions of vigorous activity per week, for a short intervention aimed at increasing the use of parks and walking. The calculated adjusted RR was 1.08 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.17) with the interpretation of this finding complicated by a decrease in physical activity attainment in both the intervention and the comparison communities. This was demonstrated with the risk difference (RD) for the intervention being ‐0.2. Similarly, Rissel 2010, with an emphasis on cycling, used the same outcome measures and found no increase (adjusted RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.02).

A further study did report on the number of people involved in physical exercise, however we could not obtain a definition of physical exercise (Guo 2006). Given this, interpretation of the results of this study conducted in rural villages in China was difficult (and this study was not included in Table 6). This was further complicated as the villages were not comparable at baseline for the number of people undertaking physical activity (34.6%, 95% CI 29.7 to 40.2; 6.2%, 95% CI 12.2 to 20.8). The study did conclude there was a significant difference in the number of people undertaking physical exercise between the intervention and control villages over the period of the study (change of 27%; P value not found).

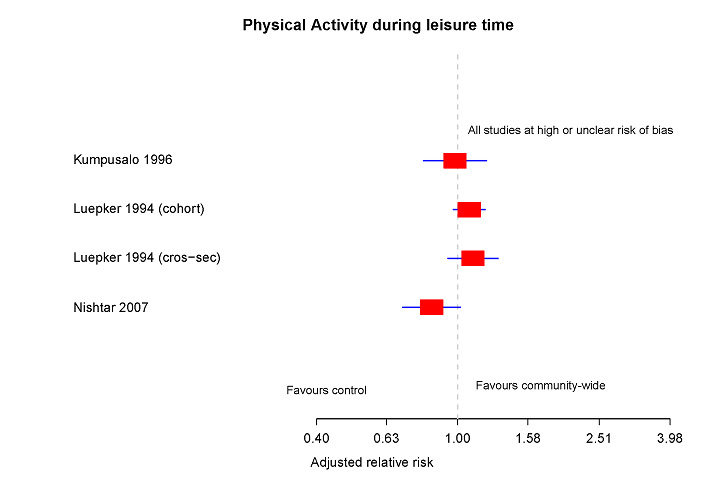

Three studies reported the measure of leisure time physical activity (Kumpusalo 1996; Luepker 1994; Nishtar 2007) (Table 7; Figure 6). Two studies, one set across a large region in Pakistan (Nishtar 2007) and the other in Finnish villages (Kumpusalo 1996), found no evidence of effect. One of these studies, the Minnesota Heart Health Program, found some evidence of effectiveness although this was not consistent across the different sampling methods used in the study nor over the time span of data collection (Luepker 1994).

6. Dichotomous outcomes ‐ physical activity during leisure time.

| Study | Overall bias | Measure | Definition | Net % change | Unadjusted RD | Adjusted RD (95% CI) | Unadjusted RR | Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Baseline |

| Luepker 1994 | Unclear risk of bias | PA during leisure time | Regularly active during leisure time | a11.26 | 8.5 | 5.35 (‐3.32 ‐ 14.02) | 1.08 | 1.11 (0.94 ‐ 1.30) | 48.6 |

| b9.4 | 4.3 | 4.70 (‐1.64 ‐ 11.04) | 1.09 | 1.08 (0.97 ‐ 1.20) | 49.4 | ||||

| Kumpusalo 1996 | High risk of bias | PA during leisure time | Undertaking physical activity during leisure time > 3 times weekly | ‐1.76 | 0.6 | ‐0.64 (‐8.24 ‐ 6.96) | 1.02 | 0.98 (0.80 ‐ 1.21) | 39.0 |

| Nishtar 2007 | Unclear risk of bias | PA during leisure time | Not provided | ‐25.58 | 2.5 | 0.52 (‐0.04 ‐ 1.08) | 2.41 | 0.88 (0.77 ‐ 1.02) | 3.0 |

adata from independent surveys

bdata from cohort surveys

RD = Risk difference

RR = Relative Risk

6.

Forest plot of dichotomous outcomes of meeting a criteria of being physically active during leisure time ‐ mixed measures and study designs.