Key Points

Question

What are the financial outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in California hospitals?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of 348 California hospitals between the first quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, hospital financial performance was highly variable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Financial losses were reduced by COVID-19 relief funding and strong equities market performance starting in the second quarter of 2020; losses were concentrated among safety-net hospitals, with operating losses totaling more than $3.2 billion across 101 California safety-net hospitals between the first quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2021.

Meaning

In this study, government assistance programs were found to play a substantial role in lessening the financial damage of COVID-19 for hospitals in California, especially those with safety-net status.

Abstract

Importance

The COVID-19 pandemic challenged the financial solvency of hospitals, yet there is limited evidence examining hospital financial performance through the first 15 months of the pandemic.

Objective

To assess the financial outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in California hospitals.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study tracked the financial performance of 348 hospitals in California using Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data from the State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Hospital financial performance was examined from January 2019 to June 2021 for all hospitals in aggregate and by safety-net status.

Exposures

Pre–COVID-19 financial outcomes vs COVID-19 period outcomes.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Quarterly revenues, expenses, and profits.

Results

In 348 California hospitals, hospital financial performance was highly variable during the COVID-19 pandemic. Losses were reduced by COVID-19 relief funding and strong equities market performance starting in the second quarter of 2020. Non–safety net hospitals maintained positive operating margins throughout the pandemic, while safety-net hospitals experienced large losses. Between the first quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2021, California safety-net hospitals’ net operating losses were more than $3.2 billion.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study of California hospitals, hospital financial performance was tracked between the first quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021. Although hospitals experienced reduced profits between January 2020 and June 2021, the interventions of government assistance programs were able to mitigate more detrimental fiscal consequences. When compared with non–safety net hospitals, safety-net hospitals were confronted with more concentrated financial losses.

This cross-sectional study uses quarterly data from 348 California acute care facilities between 2019 and June 2021 to assess financial outcomes, government financial assistance programs, and safety-net hospital performance compared with non–safety net hospital performance.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic placed substantial pressure on the US health care industry and caused substantial disruptions to the acute care hospital system. Beginning in March 2020, many hospitals cancelled elective and outpatient procedures to accommodate potential surges of COVID-19 in patients and reduce hospital transmission of the virus. Elective and outpatient procedures are important factors in a hospital’s financial health, accounting for approximately 63% of an average hospital’s revenue in 20181 and their cancellation posed serious challenges to the financial solvency of many hospitals.2,3 Although increased admissions for patients with COVID-19 might have partially offset lost revenue from other procedures, the American Hospital Association estimated a total loss of $202.6 billion by American hospitals between March and June 2020.4

Realizing the potential destabilizing financial consequences of COVID-19 for health care professionals and facilities,5,6 the US federal government enacted a number of assistance programs. Beginning in April 2020, the Provider Relief Fund (PRF) granted hospitals participating in Medicare 2% of their previous year’s patient revenue.7 Subsequent PRF distributions were targeted at rural hospitals, safety-net hospitals (SNHs), and health care institutions serving a high share of Medicaid patients. Other financial assistance came in forms such as a 20% increase in Medicare payments for patients with COVID-19, loans through the Medicare Accelerated and Advance Payment Programs and the Paycheck Protection Program, state-funded increases in Medicaid payments in many states, and reimbursements to health care organizations for testing, treatment, and vaccination of uninsured patients.8 The scale of financial assistance given to hospitals was unprecedented and helped the overall profit margins of hospitals in 2020 to remain similar to prior years, especially for government, rural, and smaller hospitals.9

Similar to government, rural, and smaller hospitals, SNHs traditionally operated on thinner margins prior to the pandemic10 and might have been disproportionately disrupted by COVID-19 both financially and operationally.11,12 Consequently, the patient populations served by these SNHs were vulnerable to reduced access to health care services. To address this situation, the PRF contained a $10 billion targeted distribution for SNHs.13

This cross-sectional study analyzed the financial performance of California hospitals overall and by SNH during the first 6 quarters of the COVID-19 pandemic. Observing continuous dynamics of hospital financial performance is important to an understanding of how hospitals fared as cases rapidly surged then receded multiple times in 2020 and 2021. Using quarterly data from 348 California acute care facilities between 2019 and June 2021, this study focused on 3 research questions: (1) What happened to California hospitals financially during the first 18 months of the COVID-19 outbreak? (2) What roles did government financial assistance programs play? and (3) How did SNHs fare compared with non-SNHs?

Methods

Data Collection

We used Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data from the State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development.14 The University of North Carolina Wilmington Office of Sponsored Programs and Research Compliance reviewed this study and determined that this study did not meet the regulatory definition of human participants research; therefore, approval was waived. The sample was limited to hospitals with financial data deemed comparable to other hospitals by the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Noncomparable hospitals excluded from the analysis included Kaiser Permanente hospitals that report consolidated data for many hospitals, psychiatric hospitals, long-term care hospitals, Shriners hospitals that do not charge for care, and state hospitals that provide care for patients with mental and developmental disabilities. The analysis sample included 3480 observations in a panel of 348 hospitals observed for 10 quarters (January 2019 to June 2021). This cross-sectional study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Statistical Analysis

For each quarter, we calculated mean operating revenues, operating expenses, net operating income, nonoperating income and expenses, and net income for the sample of 348 hospitals from the first quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2021.

Total revenue was calculated by summing inpatient revenue, outpatient revenue, and other operating revenue. Other operating revenue included various revenues, such as nonpatient food sales, sale of drugs to individuals who were not patients, medical records, parking, and tuition from medical and nursing schools. In addition, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services requires hospitals to report the PRF payments as other operating revenue on the Medicare Cost Report.15 However, it is not possible to directly measure the amount of assistance because The Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data contains a single field for all items belonging to other operating revenue and does not break out subcategories.

Our results focus on 2 forms of profitability: net operating income and net income. Net operating income is a component of net income and represents profit after total operating expense is deducted from total revenue, but before nonoperating income and expense is considered. Thus, we calculated net operating income as the total of inpatient, outpatient, and other operating revenue less expenses from patient care. After calculating net operating income, nonoperating revenues less expenses were subtracted to reach net income. These nonoperating revenues less nonoperating expenses included revenue from real estate rental income, rental and medical building expenses, unrestricted donations, governmental appropriations, housing expenses, retail operations expenses, and investment income. The data did not break out categories of this variable separately, but other research found that the largest category of nonoperating income less nonoperating expenses was investment income.16 For each hospital, we calculate operating margin by dividing net operating income by total revenue, and profit margin by dividing net income by total revenue.

Next, we subset our sample of 348 hospitals into 247 non-SNHs and 101 SNHs and analyzed the financial performance of them. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has traditionally used the Medicare Disproportionate Share Hospital index to define SNHs.17 Furthermore, the eligibility criteria for the PRF Safety Net Hospitals Targeted Distribution required hospitals to have a Medicare Disproportionate Patient Percentage of 20.2% or higher.18 We followed this definition and hospitals were classified as an SNH if Medicaid and indigent discharges as a percentage of total discharges were within the top quartile in 2019.

The first detected COVID-19 case in the US was confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on January 21, 2020, and COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020.19 Therefore, the 4 quarters of 2019 were considered pre–COVID-19 periods and all subsequent quarters were COVID-19 periods.

We calculated sample means and 95% CIs to compare groups. For primary analysis, statistical significance was not assessed. All dollar values were deflated to first quarter 2019 prices using the hospital price index.20 When statistical tests were performed, statistical significance was set at 2-sided P < .05. Data analyses were performed using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corp).

Results

Overall Financial Performance

Table 1 presents mean revenues, expenses, and income for the 348 hospitals from the first quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2021. Mean net operating income was the lowest in second quarter 2020 at −$2.7 million (95% CI, −$6.5 million to $1.1 million). Despite operating losses, large increases in other operating revenue (mean, $9.3 million; 95% CI, $7.1 million to $11.4 million) and nonoperating revenue (mean, $4.3 million; 95% CI, $1.7 million to $6.8 million) mitigated losses as government assistance programs and the stock market recovery took effect during the quarter. Mean net operating income was again negative in the first quarter of 2021 (mean, −$1.1 million; 95% CI, −$3.6 to $1.5 million) and positive during other quarters.

Table 1. Revenues, Expenses, and Income for All Hospitalsa.

| Variable | Quarter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||||

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | First | Second | Third | Fourth | First | Second | |

| Revenue in US $ millions | ||||||||||

| Total | 83.053 | 87.468 | 80.818 | 81.129 | 84.257 | 78.810 | 82.567 | 84.863 | 83.403 | 86.423 |

| Inpatient | 49.033 | 50.215 | 45.934 | 46.444 | 49.437 | 44.217 | 46.999 | 48.956 | 49.489 | 47.768 |

| Outpatient | 30.768 | 33.509 | 31.351 | 31.189 | 31.463 | 25.311 | 29.949 | 30.636 | 29.389 | 34.335 |

| Other operating | 3.252 | 3.744 | 3.532 | 3.496 | 3.357 | 9.281 | 5.619 | 5.272 | 4.525 | 4.321 |

| Total operating expenses | 78.481 | 80.943 | 79.698 | 80.713 | 83.424 | 81.488 | 81.153 | 84.490 | 84.478 | 82.686 |

| Inpatient | 48.163 | 48.485 | 47.402 | 48.257 | 50.865 | 51.905 | 49.681 | 52.130 | 52.935 | 48.346 |

| Outpatient | 30.318 | 32.458 | 32.297 | 32.456 | 32.559 | 29.583 | 31.472 | 32.360 | 31.543 | 34.340 |

| Net operating income | 4.573 | 6.525 | 1.120 | 0.415 | 0.832 | −2.678 | 1.413 | 0.373 | −1.075 | 3.737 |

| Nonoperating revenue less nonoperating expenses | 4.137 | 2.986 | 1.765 | 7.574 | −2.636 | 4.270 | 5.436 | 7.687 | 4.832 | 6.466 |

| Net income | 8.709 | 9.511 | 2.885 | 7.989 | −1.804 | 1.592 | 6.849 | 8.060 | 3.756 | 10.203 |

| Margin, % | ||||||||||

| Operating | 2.9 | 5.1 | −0.9 | −0.8 | −1.2 | −3.6 | 0.9 | 0.3 | −1.2 | 2.3 |

| Profit | 7.1 | 8.4 | 1.2 | 7.7 | −1.9 | 1.7 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 2.2 | 7.5 |

| No. of hospitals | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 | 348 |

Table shows mean revenue, expenses, and margins for 348 California hospitals between the first quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, shown in millions of dollars. Data are the Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data from the State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. The analysis sample included 3480 observations in a panel of 348 hospitals observed for 10 quarters.

Mean net income was the lowest during the first quarter of the pandemic in the first quarter of 2020 at −$1.8 million (95% CI, −$4.2 million to $0.5 million). This decrease in net income is associated with nonoperating revenue less nonoperating expenses which decreased by a mean of $10.2 million from $7.6 million (95% CI, $5.2 million to $9.9 million) in the fourth quarter of 2019 to −$2.6 million in the first quarter of 2020 (95% CI, −$5.0 million to −$0.2 million). All subsequent quarters mean net income was positive and comparable to prepandemic levels.

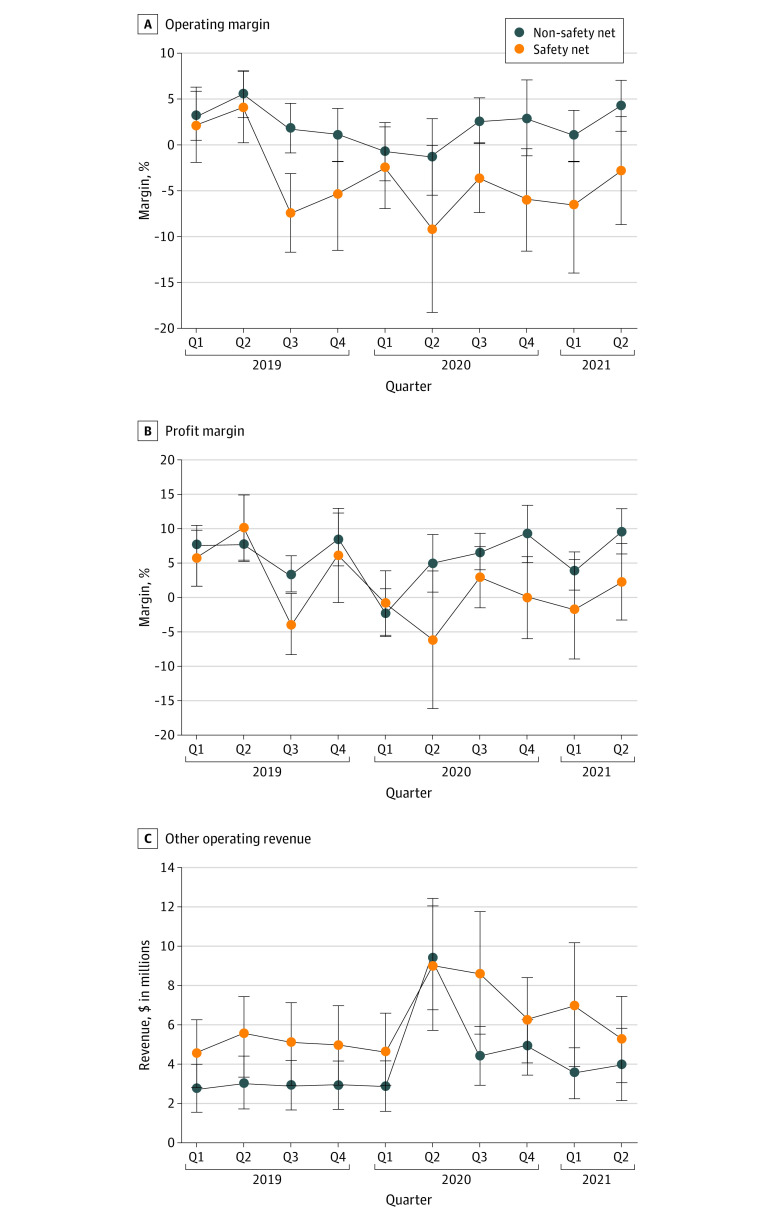

For all hospitals, the operating margin decreased from 2.8% (95% CI, 0.9% to 4.7%) in 2019 to 0.4% (95% CI, −1.8% to 2.6%) in 2020 then increased to 1.3% (95% CI, −1.1% to 3.7%) in the first 6 months of 2021 (Figure 1A). Non-SNH hospitals followed a similar pattern. In contrast to non-SNHs, SNH margins did not show a recovery in 2021 and were negative in 2020 and 2021. A similar pattern occurs for total margin (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Annualized Operating Margin and Profit Margin From Q1 2019 to Q2 2021.

Data are the Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data from the State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development and COVID-19. The sample contains 348 hospitals. Q indicates quarter.

Figure 2 presents quarterly operating margin and total profit margin for all hospitals with the same data shown in Table 1. Profit margin decreased substantially to −1.9% (95% CI, −5.0% to 1.0%) in the first quarter of 2020. Operating margin decreased in the second quarter of 2020 but recovered during the subsequent quarters.

Figure 2. Quarterly Operating Margin and Profit Margin for All Hospitals Q1 2019 to Q2 2021.

Data are the Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data from the State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development and COVID-19. The sample contains 348 hospitals. Q indicates quarter.

Financial Performance by Safety-Net Status

Non-SNHs fared substantially better than SNHs during the pandemic (Table 2 and Figure 3). For non-SNHs, operating margin was negative only in the first and second quarters of 2020 and quickly returned to positive levels comparable to pre–COVID-19 quarters. In comparison, operating margin for SNHs decreased substantially from the first quarter of 2020 to the second quarter of 2020 and remained lower than pre–COVID-19 quarters for the sample periods (Figure 3A). Similar trends occurred with respect to profit margin (Figure 3B). Between the first quarter of 2020 and the second quarter of 2021, California safety-net hospitals’ net operating losses were more than $3.2 billion. During the course of our research, we found that California SNHs were more likely to be teaching hospitals (16% [170 of 1010 hospital-quarters] vs 5% [120 of 2470 hospital-quarters]; P<.001), less likely to be rural (10% [100 of 1010 hospital-quarters] vs 16% [394 of 2470 hospital-quarters]; P<.001), have more beds (mean [SD], 248 [18.9] for SNH vs 206 [11.4] for non-SNH; P<.001), and were located in areas with lower median household income ($71 709 vs $74 517; P<.001).

Table 2. Revenues, Expenses, and Income by Safety-Net Statusa.

| Variable | Quarter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | ||||||||

| First | Second | Third | Fourth | First | Second | Third | Fourth | First | Second | |

| Non–safety net hospitals | ||||||||||

| Revenue in US $ millions | ||||||||||

| Total | 82.297 | 86.374 | 82.644 | 82.649 | 84.049 | 78.371 | 83.453 | 86.483 | 83.784 | 88.105 |

| Inpatient | 47.822 | 48.63 | 46.148 | 46.403 | 47.896 | 41.892 | 46.477 | 48.274 | 48.348 | 47.284 |

| Outpatient | 31.733 | 34.722 | 33.595 | 33.351 | 33.307 | 27.1 | 32.57 | 33.315 | 31.919 | 36.874 |

| Other operating | 2.741 | 3.022 | 2.901 | 2.895 | 2.846 | 9.379 | 4.406 | 4.893 | 3.518 | 3.948 |

| Total operating expenses | 77.737 | 79.344 | 78.644 | 80.431 | 82.205 | 77.829 | 79.894 | 83.665 | 82.276 | 81.448 |

| Inpatient | 46.67 | 46.272 | 45.38 | 46.658 | 48.462 | 47.148 | 46.932 | 49.541 | 49.543 | 45.849 |

| Outpatient | 31.067 | 33.073 | 33.263 | 33.773 | 33.743 | 30.681 | 32.962 | 34.125 | 32.733 | 35.599 |

| Net operating income | 4.56 | 7.03 | 4 | 2.218 | 1.844 | 0.542 | 3.559 | 2.817 | 1.508 | 6.657 |

| Nonoperating revenue less nonoperating expenses | 3.735 | 1.944 | 1.003 | 6.794 | −3.628 | 4.948 | 4.783 | 7.691 | 3.83 | 5.342 |

| Net income | 8.295 | 8.973 | 5.003 | 9.012 | −1.784 | 5.491 | 8.342 | 10.508 | 5.338 | 11.999 |

| Margin, % | ||||||||||

| Operating | 3.2 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 1.1 | −0.7 | −1.3 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 1 | 4.3 |

| Profit | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| No. of hospitals | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 | 247 |

| Safety-net hospitals | ||||||||||

| Revenue in US $ millions | ||||||||||

| Total | 84.904 | 90.143 | 76.353 | 77.411 | 84.764 | 79.882 | 80.399 | 80.904 | 82.469 | 82.312 |

| Inpatient | 51.996 | 54.09 | 45.412 | 46.544 | 53.204 | 49.902 | 48.276 | 50.624 | 52.28 | 48.953 |

| Outpatient | 28.408 | 30.542 | 25.865 | 25.9 | 26.954 | 20.938 | 23.539 | 24.082 | 23.203 | 28.125 |

| Other operating | 4.5 | 5.511 | 5.076 | 4.966 | 4.606 | 9.043 | 8.584 | 6.198 | 6.986 | 5.234 |

| Total operating expenses | 80.301 | 84.853 | 82.278 | 81.403 | 86.406 | 90.437 | 84.233 | 86.506 | 89.863 | 85.715 |

| Inpatient | 51.813 | 53.899 | 52.344 | 52.169 | 56.743 | 63.54 | 56.405 | 58.462 | 61.231 | 54.452 |

| Outpatient | 28.487 | 30.954 | 29.934 | 29.234 | 29.663 | 26.897 | 27.828 | 28.044 | 28.631 | 31.263 |

| Net operating income | 4.603 | 5.29 | −5.925 | −3.992 | −1.642 | −10.554 | −3.834 | −5.603 | −7.393 | −3.403 |

| Nonoperating revenue less nonoperating expenses | 5.118 | 5.535 | 3.629 | 9.481 | −0.21 | 2.61 | 7.032 | 7.678 | 7.282 | 9.212 |

| Net income | 9.721 | 10.825 | −2.296 | 5.488 | −1.852 | −7.944 | 3.198 | 2.075 | −0.111 | 5.809 |

| Margin, % | ||||||||||

| Operating | 2.2 | 4.2 | −7.4 | −5.4 | −2.5 | −9.2 | −3.6 | −6 | −6.5 | −2.8 |

| Profit | 4.1 | 4.8 | 4.4 | 6.9 | 4.8 | 10 | 4.5 | 6 | 7.2 | 5.6 |

| No. of hospitals | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 | 101 |

Table shows mean revenue, expenses, and margins for 247 non–safety net hospitals and 101 safety-net hospitals between the first quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2021, in millions of dollars. Data are the Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data from the State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. The analysis sample included 3480 observations in a panel of 348 hospitals observed for 10 quarters.

Figure 3. Operating Margin, Profit Margin, and Other Operating Revenue Data.

Operating margin, profit margin, and other operating revenue data are the hospital quarterly financial and utilization data from the State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development and COVID-19. The sample contains 101 safety-net hospitals and 247 non–safety net hospitals. A safety-net hospital is defined by being in the top quartile of Medicaid and indigent discharges as a percentage of total discharges in 2019.

The PRF played an important role in the finances of both SNH and non-SNHs (Figure 3C). From the first quarter of 2019 to the first quarter of 2020, other operating revenue stayed relatively constant for both SNHs and non-SNHs. Increases in other operating revenue were observed in the second quarter of 2020, from $4.6 million (9.5% CI, $2.8 million to $6.5 million) to $9.0 million (95% CI, $5.6 million to $12.4 million) for SNHs. For non-SNHs, other operating revenue increased from $2.8 (95% CI, $1.6 million to $4.1 million) to $9.4 million (95% CI, $6.7 million to $12.0 million). Although subsequent quarters experienced reductions relative to the second quarter of 2020, other operating revenue stayed higher than prepandemic levels. The decrease in other operating revenue was smaller for SNHs, likely representing additional PRF targeted at SNHs.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we examined the financial performance of California hospitals during the first 6 COVID-19 quarters. The first 2 pandemic quarters (the first quarter of 2020 and second quarter of 2020) were characterized by reduced net operating income and net income. Net profitability of hospitals was associated with fluctuations in other operating revenue and nonoperating revenue less nonoperating expenses. Government assistance played an important role in the increase in other operating revenue and helped to contain what could have been a much more dire situation for hospitals. In addition, the fluctuations in nonoperating revenue less expense is associated with financial market performance, which further helped bolster hospital profits from the second quarter of 2020 to the second quarter of 2021.21 These trends in profitability were not evenly distributed across all hospitals because changes were more pronounced among SNHs.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the data are limited to the state of California, which may not be generalizable to the US. Nevertheless, California comprises 12% of the US population and has had the most COVID-19 cases and deaths to date.22 Studying California is worthwhile because the California Hospital Quarterly Financial and Utilization Data are quarterly whereas other hospital financial data available at the annual level (eg, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hospital cost reports, American Hospital Association Annual Survey) lack the granularity to measure within-year dynamics in financial performance. As we have reported, net income was variable with periods of substantial decreases and increases relative to the pre–COVID-19 period.

The second limitation of this study is that COVID-19 relief payments and changes in the value of equity market holdings are grouped into variables with other types of income and expenses. This data limitation prevents us from quantifying the exact contribution of these items to changes in profitability. However, the goal of this article is to track overall changes in hospital profits during the pandemic. The allocation of COVID-19 PRF23,24 and nonoperating income’s role in hospital profitability during the prepandemic period has been studied elsewhere.16,25 Future research should use different data to explore these items in terms of profit outcomes.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study of California hospitals, we found a negative association between COVID-19 and hospital financial performance. Although hospitals experienced reduced profits between January 2020 and June 2021, the intervention of government assistance programs was able to mitigate more detrimental fiscal consequences. When compared with non-SNHs, SNHs had lower profits and received more government assistance.

eFigure. Non-Operating Income Less Non-Operating Expenses and S&P 500 Performance

References

- 1.Khullar D, Bond AM, Schpero WL. COVID-19 and the Financial Health of US Hospitals. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2127-2128. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM. Characteristics of operating room procedures in US hospitals, 2011. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. February 2014. Accessed August 16, 2022. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb170-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States-2011.jsp [PubMed]

- 3.Best MJ, McFarland EG, Anderson GF, Srikumaran U. The likely economic impact of fewer elective surgical procedures on US hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surgery. 2020;168(5):962-967. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Hospital Association . Hospitals and Health Systems Face Unprecedented Financial Pressures Due to COVID-19. 2020:1-11. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.aha.org/guidesreports/2020-05-05-hospitals-and-health-systems-face-unprecedented-financial-pressures-due

- 5.Colenda CC, Applegate WB, Reifler BV, Blazer DGI II. COVID-19: Financial Stress Test for Academic Medical Centers. Acad Med. 2020;95(8):1143-1145. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graves JA, Baig K, Buntin M. The Financial Effects and Consequences of COVID-19: A Gathering Storm. JAMA. 2021;326(19):1909-1910. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) . COVID Relief Funding for Medicaid Providers. 2021:1-12. Issue Brief. February 2021. https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/COVID-Relief-Funding-for-Medicaid-Providers.pdf

- 8.Ochieng N, Fuglesten Biniek J, Musumeci M, Neuman T. Funding for Health Care Providers During the Pandemic: An Update. 2021. Accessed January 19, 2022. https://www.kff.org/policy-watch/funding-for-health-care-providers-during-the-pandemic-an-update/#

- 9.Wang Y, Bai G, Anderson G. COVID-19 and Hospital Financial Viability in the US. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(5):e221018. doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bazzoli GJ, Fareed N, Waters TM. Hospital financial performance in the recent recession and implications for institutions that remain financially weak. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):739-745. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coughlin TA, Ramos C, Samuel-Jakubos H. Safety net hospitals in the COVID-19 crisis: how five hospitals have fared financially. 2020. Accessed December 27, 2021. https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2020/12/safety-net-hospitals-in-the-covid-19-crisis-how-five-hospitals-fared-financially.html

- 12.Morning Briefing KHN. 'On a precipice’: safety-net hospitals struggle to survive during pandemic. Accessed January 2, 2022. https://khn.org/morning-breakout/on-a-precipice-safety-net-hospitals-struggle-to-survive-during-pandemic/

- 13.Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) . Targeted Distributions. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.hrsa.gov/provider-relief/data/targeted-distribution

- 14.State of California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development . Hospital Quarterly Financial & Utilization Report. https://data.chhs.ca.gov/dataset/hospital-quarterly-financial-utilization-report-complete-data-set

- 15.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) Billing. 2021:1-180. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/03092020-covid-19-faqs-508.pdf

- 16.Bai G, Yehia F, Chen W, Anderson GF. Investment Income of US Nonprofit Hospitals in 2017. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(9):2818-2820. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05929-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popescu I, Fingar KR, Cutler E, Guo J, Jiang HJ. Comparison of 3 Safety-Net Hospital Definitions and Association With Hospital Characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e198577-e198577. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) . Targeted Distribution Questions. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.hrsa.gov/provider-relief/faq/target-distribution

- 19.The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . First Travel-related Case of 2019. Novel Coronavirus Detected in United States. Accessed December 5, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html

- 20.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics . Producer Price Index by Commodity: Health Care Services: Hospital Inpatient Care [WPU512101]. Accessed February 3, 2022. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WPU512101

- 21.Kacik A. Not-for-profit hospitals lean on investment income to cover losses. Modern Healthcare. Accessed June 24, 2022. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/finance/not-profit-hospitals-investment-income-covers-operating-losses

- 22.Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) . Cumulative COVID-19 Cases and Deaths. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/cumulative-covid-19-cases-and-deaths/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Number%20of%20COVID-19%20Cases%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D

- 23.Grogan CM, Lin Y-A, Gusmano MK. Health Equity and the Allocation of COVID-19 Provider Relief Funds. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(4):628-631. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coughlin TA, Ramos C, Samuel-Jakubos H. More Than a Year and a Half after Congress Approved Funding to Help Health Care Providers Weather the Pandemic, Billions of the $178 Billion Allocated Remain Unspent Remain Unspent. 2021:1-16. October 2021. Accessed February 3, 2022. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104969/more-than-a-year-and-a-half-after-congress-approved-funding-to-help-health-care-providers-weather-the-pandemic-billions-of-the-178-billion-allocated-remain-unspent_0.pdf

- 25.Singh SR, Song PH. Nonoperating revenue and hospital financial performance: do hospitals rely on income from nonpatient care activities to offset losses on patient care? Health Care Manage Rev. 2013;38(3):201-210. doi: 10.1097/HMR.0b013e31825f3e16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Non-Operating Income Less Non-Operating Expenses and S&P 500 Performance