Abstract

Background

Frailty and obesity are associated with poor outcomes in older adults. Previous studies have shown that excessive visceral fat leads to frailty by promoting inflammation. However, the association between visceral fat obesity (VFO) and frailty has not been elucidated. We aimed to investigate the correlation between VFO and frailty in middle-aged and older adults.

Methods

A total of 483 adults aged ≥45 years were recruited. Estimated visceral fat area (eVFA) and total fat (TF) were determined by bioimpedance analysis. Waist circumference, body mass index (BMI), and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were recorded. Frailty was assessed using the Fried frailty phenotype. Logistic regression analysis was used to analyze the association between frailty and other variables. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the correlations between the frailty phenotype score, eVFA/TF, and other factors.

Results

Frail adults were older and had higher waist circumference, eVFA metabolic indicators, and coronary artery disease incidence. Participants with frailty had a higher prevalence of VFO than those without. After adjusting for age, sex, and chronic diseases, frailty was associated with eVFA but not waist circumference, WHR, or BMI. Spearman correlation analysis showed that the frailty phenotype score was positively associated with eVFA and BMI in women but not men. After adjusting for age, frailty was not associated with BMI or WHR. The eVFA/TF ratio was negatively correlated with grip strength and walking speed and positively correlated with the clinical frailty scale score in middle-aged and older adults.

Conclusion

Middle-aged and older adults with VFO had a higher risk of frailty. Frailty was associated with a higher eVFA but not with BMI or WHR. The frailty score was positively associated with eVFA and BMI in women, but not in men. A higher eVFA was correlated with worse physical function, even after adjusting for TF.

Keywords: visceral fat obesity, visceral fat area, frailty, middle-aged and older adults

Introduction

Frailty is a medical syndrome with decreased multisystem function, manifested by increased susceptibility to stress events and increased risk of disability, falls, fractures, hospitalization, dependency, and death.1 Although frailty was initially identified and confirmed in older adults, increasing evidence suggests that frailty is a marker of the health status of inpatients in all age groups.2,3 Therefore, frailty does not only affect older adults; it can be measured from the middle years, thereby expanding the possibility of prevention and strengthening the focus on frailty development in the course of life.

Obesity has been recognized as one of the most serious public health problems and may exacerbate age-related declines in health and physical function, leading to deterioration in overall health and quality of life.4 Obesity is one of the most important predictors of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases.5 Intra-abdominal fat is more harmful to the cardiovascular and metabolic systems than abdominal wall fat.6 Visceral fat is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality.7 The relationship between visceral fat and longevity is causal, visceral fat depletion as a potential treatment strategy to prevent or delay age-related diseases and to increase longevity.8 Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) has been used to assess visceral fat area (VFA), reflecting the degree and distribution of visceral fat accumulation.9 Adults with VFA ≥100 cm2 can be diagnosed with visceral fat obesity (VFO).10

Frail older adults with obesity have a high mortality.11 Abdominal obesity is a risk factor for frailty in various populations.12,13 Recent studies highlighted the importance of assessing body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC) in older adults, suggesting that general and abdominal obesity should be routinely screened to determine frailty in clinical practice.14 Frail patients are more likely to have a higher body fat mass and WC.15 Furthermore, WC is a better indicator for detecting frailty than BMI.13 Excessive visceral fat can lead to frailty by promoting inflammation and increasing insulin resistance.16 However, the relationship between VFO and frailty has not been investigated. Therefore, we aimed to clarify the association between VFO, which is harmful to health, and frailty. In addition, the selection of middle-aged and older adults is more conducive to early detection and intervention. We hypothesized that VFO would be associated with a high risk of frailty in middle-aged and older adults.

Methods

Study Population

A total of 483 participants (45–97 years), 211 middle-aged adults (45–64 years) and 272 older adults (65–97 years), were recruited. The average age for the total population was 68.82±11.04 years, including 295 men and 188 women. Data on medical history and physical and laboratory examinations were collected. Those who could not complete the assessments or had severe diseases, including heart, liver, kidney, thyroid, and hematological diseases, were excluded. Adults with peripheral amputation and life-sustaining transplantable medical instruments such as pacemakers for whom we were unable to use BIA due to these conditions were also excluded. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University (2018–039). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Frailty Assessment

Frailty was assessed by frailty phenotype by Fried et al17 including the following five items: 1) Shrinking was defined as unintentional weight loss by ≥4.5 kg or ≥5% of body weight in the past year;17 2) Weakness used the cutoff value of handgrip strength based on Chinese older adults, adjusted for sex and BMI;18 3) Fatigue was identified by two questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale: “I felt that everything I did was an effort” or “I could not get going”;19 4) Slowness used the cutoff value of walking speed based on our previous study, adjusted for sex and height;20 5) Inactivity was defined as self-reported exercise for <3h/week over the past 12 months.21 Frailty was classified as the presence of three or more of these criteria, and non-frailty as less than 3.

Handgrip strength was measured in the standing position with participants wearing light clothes. Both hands were measured using a CAMRY EH101 electronic grip meter (SENSSUN, China). Two measurements were performed for each individual, and a higher value was recorded in kilograms (kg). Walking was measured over 4 m in an unobstructed corridor. Individuals were instructed to walk at their usual pace, and walking time was recorded. The ratio of 4 m to time was the walking speed.

The Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) was used to assess a person’s level of frailty. CFS is a judgment-based frailty tool that evaluates specific domains, including comorbidity, function, and cognition, to generate a frailty score ranging from 1 (very fit) to 9 (terminally ill).22

Anthropometric Assessment

Trained staff administered a structured questionnaire through interviews and collected anthropometric measurements using standard procedures.23 Height, body mass, WC, and hip circumference were recorded. Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) is the ratio of WC divided by hip circumference. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (m) squared.

Assessment of Estimated VFA

Estimated VFA (eVFA) and total fat (TF) were assessed using BIA with a body composition analyzer, ioi353 (JAWON, Korea). We used ioi353 to analyze body composition in five segments of the body (right upper limb, left upper limb, trunk, right lower limb, and left lower limb) with 8 points of tactile electrodes, according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The BIA method for measuring VFA is significantly associated with computed tomography (CT), which is the gold standard for measuring VFA.24 Individuals with an eVFA ≥100 cm2 were defined as having a VFO.10 The eVFA/TF is the ratio of eVFA divided by TF.

Clinical Assessment

After a rest period of at least 10 min, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) (HBP-1300, Omron electronic sphygmomanometer, Japan) in the left and right arms were measured in the supine position, and the mean value calculated. Hypertension was defined as SBP ≥140 mmHg (1 mmH=0.133 kPa), DBP ≥90 mmHg, per the use of antihypertensive medication based on WHO guidelines for the management of hypertension.25 Type 2 diabetes was defined based on the 2006 WHO National Diabetes Group criteria26 or use of treatments for diabetes. Coronary heart disease (CHD) was defined as significant coronary stenosis(es) on coronary angiography or CT and/or positive ischemia by stress myocardial scintigraphy.27

Laboratory Assessment

Fasting blood glucose (FBG), glycated hemoglobin, type A1C (HbA1c), alanine transaminase (ALT), uric acid (UA), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), triglyceride (TG), serum creatinine (SCr), and homocysteine (HCY) levels were measured using 12-h fasting blood samples.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation, mean rank, or number and percentage. Differences in the characteristics between the two groups were evaluated using the chi-squared test for categorical variables, independent t-test for continuous variables, and Kruskal–Wallis comparisons for abnormally distributed continuous variables. Binary logistic regression analysis adjusted for age, sex, and other risk factors was used to identify the factors associated with frailty. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the relationship between frailty phenotype score, eVFA/TF, and other factors. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (Chicago, IL, USA, version 25.0) or GraphPad Prism 9.3 software (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). P-value was considered significant at <0.05.

Results

A total of 350 participants were diagnosed with as VFO in this population (72.5%). As shown in Table S1, for the total population, WC was 96.33±8.65 cm in men and 87.56±9.48 cm in women. eVFA was 144.82±41.20 cm2 in men and 94.86±37.25 cm2 in women. The percentage of patients with hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and CHD were 70.2%, 38.1%, and 29.8%, respectively. The average frailty phenotype score was 1.04±1.10. Among the 47 participants (9.7%) categorized as frail, 0.95% were middle-aged adults, and 16.5% were older adults. The average CFS score was 4.67±1.37.

Participants with frailty were older and had more chronic diseases such as CHD. The estimated VFA and WC in the frail group was higher than those in the non-frail group; however, BMI and WHR were not different. CFS score, DBP, HbA1c, TG, TC, LDL-C, and SCr levels were higher in the frail group than in the non-frail group. Participants with frailty had a higher prevalence of VFO than those without it (89.4% vs 70.2%, P=0.042) (Table 1). Binary logistic regression analysis showed that, after adjusting for sex, age, CHD, WC, DBP, HbA1c, TC, TG, LDL-C, and Scr, eVFA was associated with frailty (odds ratio [OR]=0.982, 95% CI: 0.969–0.996, P=0.010) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison Between Frail and the Non-Frail Adults

| Non-Frail (n=436) | Frail (n=47) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General data | Sex (Male, n (%)) | 259 (59.4%) | 33 (70.2%) | 0.147 |

| Age (years) | 67.27±10.34 | 81.66±7.93 | <0.001 | |

| BMI/ (kg/m2) | 25.53±3.09 | 25.47±3.90 | 0.758 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 135.72±17.82 | 136.02±19.01 | 0.958 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.09±11.14 | 70.79±10.69 | 0.002 | |

| Obesity | WC (cm) | 92.58±9.89 | 96.62±10.92 | 0.027 |

| WHR | 0.94±0.07 | 0.96±0.05 | 0.105 | |

| eVFA (cm2) | 123.04±45.84 | 154.05±50.26 | 0.005 | |

| TF (kg) | 20.40±5.50 | 20.80±6.15 | 0.955 | |

| CFS | CFS score | 3.14±1.2 | 5.60±1.01 | <0.001 |

| Glucose and lipid metabolism | FBG (mmoL/L) | 5.8524±1.97 | 6.10±2.59 | 0.534 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.32±1.30 | 6.66±1.46 | 0.007 | |

| ALT (U/l) | 19.96±11.61 | 21.38±20.76 | 0.076 | |

| UA (μmol/L) | 339.71±88.54 | 355.70±86.54 | 0.181 | |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.74±1.31 | 1.38±0.68 | 0.015 | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.37±1.08 | 4.00±1.04 | 0.017 | |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.60±0.86 | 2.29±0.82 | 0.021 | |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.21±0.33 | 1.18±0.31 | 0.735 | |

| Scr (μmoL/L) | 70.85±35.90 | 84.47±44.92 | 0.016 | |

| HCY (μmoL/L) | 14.81±6.85 | 15.42±5.15 | 0.127 | |

| Chronic diseases | Hypertension (n, %) | 302 (69.3%) | 36 (76.6%) | 0.083 |

| T2D (n, %) | 162 (37.2%) | 23 (48.9%) | 0.329 | |

| CHD (n, %) | 116 (26.6%) | 28 (59.6%) | <0.001 |

Notes: Data were expressed as mean (standard deviation), median (interquartile range) or n (%).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; eVFA, estimated visceral fat area; TF, total fat; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin, Type A1C; ALT, alanine transaminase; UA, uric acid; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; Scr, serum creatinine; HCY, homocysteine; T2D, type 2 diabetes; CHD, coronary heart disease.

Table 2.

Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Associated with Frailty

| Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| WC | 0.961 (0.929–0.995) | 0.996 (0.984–1.007) |

| eVFA | 0.989 (0.981–0.997) | 0.982 (0.969–0.996) |

Notes: *Adjusted for sex, age, coronary heart disease, diastolic blood pressure, glycosylated hemoglobin Type A1C, total cholesterol, triglyceride, low density lipoprotein cholesterol, and serum creatinine.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; WC, waist circumference; eVFA, estimated visceral fat area.

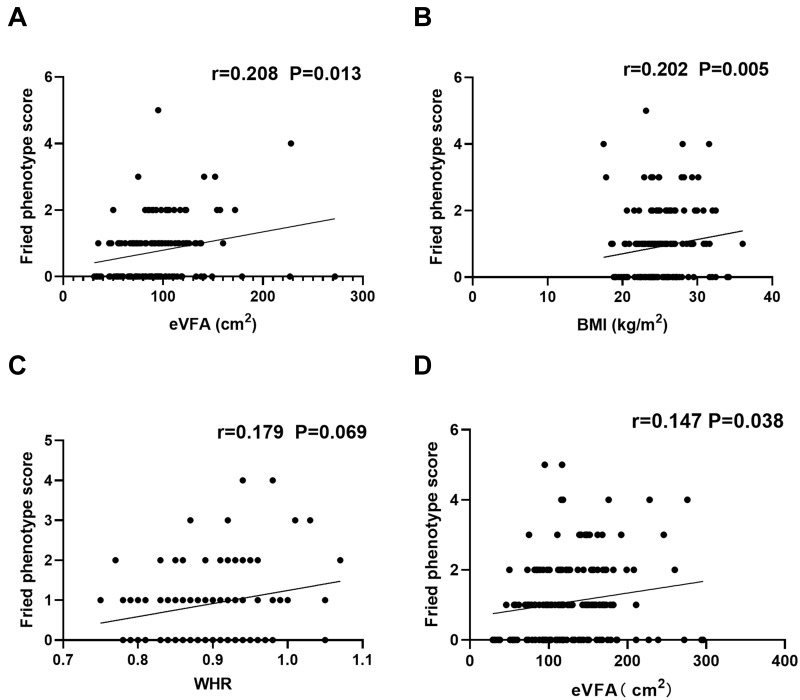

We further examined the correlation between the frailty phenotype score and eVFA, BMI, and WHR. The frailty phenotype score was positively correlated with eVFA (r=0.208, P=0.013) and BMI (r=0.202, P=0.005) in middle-aged and older women adults, and not associated with WHR (r=0.179, P=0.069) (Figure 1A–1C). For men, the frailty phenotype score was negatively associated with BMI (r=−0.134, P=0.022) before adjusting by age and this relationship was lost afterward (Table 3). However, after adjusting for age, frailty was not found to be associated with BMI or WHR. Further analysis of the subgroup of older adults showed that the frailty phenotype score was positively correlated with eVFA (r=0.147, P=0.038) (Figure 1D) but not with BMI or WHR (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Correlation between frailty and eVFA, BMI and WHR. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between frailty phenotype score and (A) eVFA, (B) BMI, (C) WHR in women (middle-aged and older adults), (D) eVFA in older adults (men and women).

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio; eVFA, estimated visceral fat area.

Table 3.

Correlation Between Frailty and eVFA, BMI and WHR

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | Adjusted P value* | r | P value | Adjusted P value* | |

| eVFA | −0.010 | 0.882 | 0.693 | 0.208 | 0.013 | 0.026 |

| BMI | −0.134 | 0.022 | 0.787 | 0.202 | 0.005 | 0.057 |

| WHR | −0.019 | 0.813 | 0.891 | 0.179 | 0.069 | 0.118 |

Note: *Adjusted by age.

Abbreviations: eVFA, estimated visceral fat area; BMI, body mass index; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

To avoid the effect of TF on the above association, we used the ratio of eVFA/TF to analyze the correlation between eVFA and physical function (grip strength and walking speed) and CFS. Higher eVFA/TF was associated with worse physical function, as indicated by weaker grip strength (men: r=−0.559, P<0.001; women: r=−0.307, P<0.001) and slower walking speed (men: r=−0.325, P<0.001; women: r=−0.200, P=0.026), as well as higher levels of frailty (CFS, men: r=0.335, P<0.001; women: r=0.284, P=0.001) in the total population. In older adults, eVFA/TF was negatively correlated with grip strength (r=−0.348, P<0.001) and walking speed (r=−0.230, P=0.027) and positively correlated with CFS (r=0.267, P<0.001) in men. In middle-aged adults, eVFA/TF was negatively correlated with grip strength (r=−0.472, P<0.001) in men and positively correlated with CFS (r=0.369, P=0.011) in women (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation Between eVFA/TF and Other Variables

| Male | Female | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P value | r | P value | |

| All adults | ||||

| Grip strength | −0.559 | <0.001 | −0.307 | <0.001 |

| Walking speed | −0.325 | <0.001 | −0.200 | 0.026 |

| CFS | 0.335 | <0.001 | 0.284 | 0.001 |

| Older adults | ||||

| Grip strength | −0.348 | <0.001 | −0.148 | 0.188 |

| Walking speed | −0.230 | 0.027 | −0.067 | 0.559 |

| CFS | 0.267 | <0.001 | 0.178 | 0.114 |

| Middle-aged adults | ||||

| Grip strength | −0.472 | <0.001 | −0.265 | 0.051 |

| Walking speed | −0.153 | 0.184 | −0.112 | 0.457 |

| CFS | 0.091 | 0.417 | 0.369 | 0.011 |

Abbreviations: eVFA, estimated visceral fat area; TF, total fat; CFS, Clinical Frailty Scale.

Discussion

Frailty is an age-related syndrome characterized by the loss of functional reserve and an increased risk of adverse consequences.28,29 Nearly 10% of adults aged ≥45 years diagnosed frailty in this study, indicating that frailty has become a serious social problem and tends to occur earlier in life. We found that participants with frailty had a higher prevalence of VFO than those without it (89.4% vs 70.2%). eVFA was higher in frail adults and remained associated with an increased risk of frailty even after adjustments for multiple variables such as age, WC, chronic conditions, and glucose and lipid metabolism. These findings provide evidence implicating the role of VFO in frailty among middle-aged and older adults.

We showed that the prevalence of VFO was as high as 72.5% in this population, which is consistent with the characteristics of central obesity in the body fat distribution in the Chinese population.30 Excessive visceral fat and increased intramuscular fat have been shown to favor pro-inflammatory and insulin resistance, and catabolic status requires clinical trials evaluating interventions for metabolic syndrome to prevent or treat frailty.16 This study showed that eVFA, but not BMI or WHR, was higher in frail participants than in non-frail participants. BMI cannot distinguish between fat mass and lean muscle mass;31 thus, it is considered a poor measure of overall obesity in older adults.31,32 WC has also been diffusely used as a substitute measure for total abdominal obesity;32 however, it cannot distinguish between subcutaneous and visceral fat within the abdominal region.33 The accrual of subcutaneous fat does not appear to play an important role in the etiology of disease risk.8

Through binary logistic regression analysis, we found that eVFA was more predictive of frailty than WC. Meanwhile, eVFA was an independent risk factor for frailty, after adjusting for sex and other risk factors. Recent studies have shown that frailty is a wasting disease, consistent with the incorporation of weight loss into the frailty criteria.34 Therefore, BMI is generally considered unsuitable for older adults; too low a BMI may increase the risk of frailty, and the relationship between them presents a U-shaped curve correlation.35 However, this was not true for VFO and frailty. With increasing medical resources, the use of simple, rapid, inexpensive, and noninvasive techniques to accurately measure body composition values, such as eVFA, can allow more accurate assessment of obesity types to predict the occurrence of frailty. An individualized program was developed for this population to improve the overall health and quality of life of the patients.

Frailty is more common in women than in men.36 Spearman correlation analysis showed that the frailty phenotype score was positively associated with eVFA in women adults in this study, and the association did not change after adjusting for age, indicating that it is necessary to control VFO as early as possible. Further analysis adjusted for TF showed that eVFA was negatively correlated with grip strength and walking speed and positively correlated with CFS in both men and women, confirming that VFO is associated with decreased physical function and frailty. Compared with older men, grip strength was more correlated with eVFA/TF in middle-aged men, and CFS was correlated with eVFA/TF in middle-aged women but not older women. This indicates that early intervention for middle-aged patients with eVFA is necessary. A previous study showed that in oldest-old adults, VFA was the best evaluator for obesity associated with mobility disability.37 Abdominal obesity could be a concern for physical, psychological, and social frailty.38 Those with high visceral adipose tissue were more likely to have poor grip strength, suggesting that the mechanisms of frailty may differ by visceral adipose tissue.39 Obesity, as defined by VFA, should be considered and valued. VFA plays an important role and has a good evaluation effect on the course of frailty.

This study had some limitations. First, this was a cross-sectional study and the associations observed could not establish a causal relationship between VFO and frailty. Therefore, further longitudinal studies are required. Second, we could not eliminate some remnant confounding influences due to comorbid conditions. Therefore, further prospective studies are needed to explore the association between frailty and VFO. Third, some relationships are based on weak r values, which may be caused by the small number participants. Despite these limitations, most frailty-related studies only targeted older adults, showing that some middle-aged adults have developed frailty, while eVFA/TF was negatively correlated with grip strength in men and positively correlated with CFS in women. Therefore, it is necessary to identify early interventions for frailty. Recent study have targeted weight loss interventions led to decreases in body and VF but preservation of muscle mass and strength.40

In conclusion, frailty has become an important issue endangering human health, and early recognition and intervention should be emphasized. This study showed that frailty was more likely in middle-aged and older adults with VFO, and that eVFA was a risk factor for frailty, which highlights the importance of assessing eVFA in middle-aged and older adults. Frailty screening should be routinely performed in adults with VFO in clinical practice. Further studies on the reduction of visceral fat accumulation and frailty interventions are warranted to validate our findings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Tong Ji, Ying Li, Yiming Pan, Yumeng Chen, Ou Zhao, Shijie Li, Guanzhen Wang, Jiatong Li, Xiaojun Li, Wanshu Zhang, and Li Zhang for their support in data collection for this study.

Disclosure

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Morley JE, Vellas B, Van Kan GA, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–397. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Chu NM, Segev DL. Frailty and longterm post-kidney transplant outcomes. Curr Transplant Rep. 2019;6(1):45–51. doi: 10.1007/s40472-019-0231-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Rasmussen S, Chu NM, et al. Perceptions and practices regarding frailty in kidney transplantation: results of a national survey. Transplantation. 2020;104(2):349–356. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Porter Starr KN, McDonald SR, Bales CW. Obesity and physical frailty in older adults: a scoping review of lifestyle intervention trials. Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu G, Wu Z, Jing L, et al. A study on the incidence of cardiovascular disease on the metabolic syndrome in 11 provinces in China. Chin J Endem. 2003;24:551–553. doi: 10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.2003.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiba Y, Saitoh S, Takagi S, et al. Relationship between visceral fat and cardiovascular disease risk factors: the Tanno and Sobetsu study. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:229–236. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuk JF, Katzmarzyk PT, Nichaman MZ, Church TS, Blair SN, Ross R. Visceral fat is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in men. Obes Res. 2006;14:336–341. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmine F, Luigi S, Saverio G, Nicolina LS, Giovanni T. Should visceral fat be reduced to increase longevity? Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):996–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia W, Lu J, Xiang K, Bao Y, Lu H, Chen L. Reliability evaluation of simple body fat parameters estimation for intra-abdominal obesity. Chin J Epidemiol. 2002;23:20–23. doi: 10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.2002.01.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuji M. The examination committee of criteria for ‘obesity disease’ in Japan, Japan society for the study of obesity. new criteria for ‘obesity disease’ in Japan. Circ J. 2002;66:987–992. doi: 10.1253/circj.66.987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee Y, Kim J, Han ES, Ryu M, Cho Y, Chae S. Frailty and body mass index as predictors of 3-year mortality in older adults living in the community. Gerontology. 2014;60:475–482. doi: 10.1159/000362330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.García-Esquinas E, José García-García F, León-Muñoz LM, et al. Obesity, fat distribution, and risk of frailty in two population-based cohorts of older adults in Spain. Obesity. 2015;23:847–855. doi: 10.1002/oby.21013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao Q, Zheng Z, Xiu S, Chan P. Waist circumference is a better predictor of risk for frailty than BMI in the community-dwelling elderly in Beijing. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018;30:1319–1325. doi: 10.1007/s40520-018-0933-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Afonso C, Sousa-Santos AR, Santos A, et al. Frailty status is related to general and abdominal obesity in older adults. Nutr Res. 2021;85:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2020.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu L, Zhang J, Shen S, et al. Association between body composition and frailty in elder inpatients. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:313–320. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S243211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clegg A, Hassan-Smith Z. Frailty and the endocrine system. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(9):743–752. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(18)30110-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu C, Smit E, Xue QL, Odden MC. Prevalence and correlates of frailty among community-dwelling Chinese older adults: the China health and retirement longitudinal study. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;73:102–108. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma L, Zhang L, Sun F, Li Y, Tang Z. Cognitive function in Prefrail and frail community-dwelling older adults in China. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19:53. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1056-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma L, Tang Z, Chan P, Walston JD. Novel frailty screening questionnaire (FSQ) predicts 8-year mortality in older adults in China. Frailty Aging. 2019;8:33–38. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2018.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Church S, Rogers E, Rockwood K, Theou O. A scoping review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:393. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01801-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stewart AD, Marfell-Jones M, Olds T, Ridder H. International standards for anthropometric assessment. In: International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry. New Zeland ISAK; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryo M, Maeda K, Onda T, et al. A new simple method for the measurement of visceral fat accumulation by bioelectrical impedance. Diab Care. 2005;28:451–453. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Writing Group of 2018 Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension, 2018 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension. Prevention and Treatment of Cardio-Cerebral-Vascular Disease. 2019;19(1):1–44. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-816X.2019.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycemia: Report of a WHO/IDF Consultation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conte SM, Vale PR. Peripheral arterial disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(4):427–432. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Europe PMC Funders Group. Frailty in older people. Lancet. 2013;381:752–762. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394:1365–1375. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31786-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C. Obesity problem—is the new public health challenges in our country. Chin J Endem. 2002;23(1):1. doi: 10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.2002.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batsis JA, Zagaria AB. Addressing obesity in aging patients. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(1):65–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Decaria JE, Sharp C, Petrella RJ. Scoping review report: obesity in older adults. Int J Obes. 2012;36(9):1141–1150. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shuster A, Patlas M, Pinthus JH, Mourtzakis M. The clinical importance of visceral adiposity: a critical review of methods for visceral adipose tissue analysis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1009):1–10. doi: 10.1259/bjr/38447238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rolland Y, Czerwinski S, Van Kan GA, et al. Sarcopenia: its assessment, etiology, pathogenesis, consequences and future perspectives. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:433–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02982704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan L, Chang M, Wang J. Abdominal obesity, body mass index and the risk of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2021;50:1118–1128. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afab039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Majid Z, Welch C, Davies J, Jackson T. Global frailty: the role of ethnicity, migration and socioeconomic factors. Maturitas. 2020;139:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2020.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chua KY, Lin X, Wang Y, Chong Y-S, Lim W-S, Koh W-P. Visceral fat area is the measure of obesity best associated with mobility disability in community dwelling oldest-old Chinese. BMC Eriatrics. 2021;21:282. doi: 10.1186/s12877-021-02226-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song X, Zhang W, Hallensleben C, et al. Associations between obesity and multidimensional frailty in older Chinese people with hypertension. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:811–820. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S234815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson MR, Kolaitis NA, Gao Y, et al. A nonlinear relationship between visceral adipose tissue and frailty in adult lung transplant candidates. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(11):3155–3161. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Batsis JA, Shirazi D, Petersen CL, et al. Changes in body composition in older adults after a technology-based weight loss intervention. J Frailty Aging. 2022;11(2):151–155. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2022.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2020YFC2008604).

Ethical Standards

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University. Information was only collected after written consent was obtained from all participants. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.