Abstract

In public good provision and other collective action problems, people are uncertain about how to balance self-interest and prosociality. Actions of others may inform this decision. We conduct an experiment to test the effect of watching private citizens and public officials acting in ways that either increase or decrease the spread of the coronavirus. For private role models, positive examples lead to a 34% increase in donations to the CDC Emergency Fund and a 20% increase in learning about COVID-19-related volunteering compared to negative examples. For public role models these effects are reversed. Negative examples lead to a 29% and 53% increase in donations and volunteering, respectively, compared to positive examples.

Keywords: COVID-19, Role models, Public goods, Prosociality, Norm activation model

1. Introduction

We take cues about how to behave from other people, especially in times of great uncertainty like the current COVID-19 pandemic. Home-bound, many turn to the media to learn about the actions of fellow citizens and political leaders as potential role models.1 Imagine you are watching the evening news and you see coverage of people defying social distancing guidelines, partying on the beach, or congregating in restaurants. Would you give up on flattening the curve or increase your efforts to make up for failings of others? What if, instead, you saw reporting of thousands of people volunteering as health workers in their communities? Would you be inspired and join the fray or sit back more relaxed, knowing that others fill in the void? And would your reaction differ if the people you saw were public figures?

We test these questions through an experiment with 690 participants recruited online in the United States. We randomly assign participants to watch a short video showing either private citizens or politicians behaving in ways that have either a negative or a positive effect on preventing the spread of the coronavirus. These news clips represent common media narratives at the time of the outbreak. We measure the effect of these videos on two forms of prosocial behavior2 : how much they donate to the CDC Emergency Fund out of a bonus that we designate to them and whether they spend time learning about local volunteering opportunities related to COVID-19.

We find that participants who watch positive citizen role models donate 34% more of their bonus than those watching people disobey social distancing guidelines. We observe a similar pattern for the volunteering outcome (although the difference is not statistically significant). Positive private role models beget more positive behavior, resulting in a virtuous cycle of prosociality; the opposite is true for negative role models (Willer, 2009).

Results look very different for public role models. We randomly assign participants to view coverage of elected officials either acting prosocially (leading the public health response and giving inspirational speech) or in an antisocial manner (failing to take actions to curb the virus, while engaging in insider trading). Participants who watch the positive role model donate 29% less and are 53% less likely to take steps to learn about volunteering opportunities compared to people who watch politicians mismanaging the crisis. In sum, results suggest that the actions of government officials are seen as substitutes, those of fellow citizens as complements to the participants’ own actions.

These results can be reconciled by Schwartz’s seminal Norm Activation Model (NAM) (Schwartz, 1977), which posits that prosocial behavior depends on both the adoption of prosocial norms and a sense of responsibility among individuals for taking actions that satisfy those norms. Trust is one of the key norms among groups that succeeded in acting prosocially and avoiding prisoner’s dilemmas (Ostrom, 2009). Studies find that the majority of people are “conditional cooperators”: they are willing to contribute to a public good if they believe that others will do the same (Fischbacher et al., 2001). Making sacrifices requires trust in reciprocity — otherwise an individual’s own costly actions are ultimately fruitless. Norms of trust can thus create coordinated responses without the need for negotiations, explicit agreements or enforcement. We find that that trust is influenced by the actions of private role models: people who watched positive examples are 21% more likely to agree with the statement “Most people can be trusted” than those who watched the negative examples of private role models.

By contrast, public role models do not affect trust norms. They do, however, influence whether people feel responsible to contribute to a collective action problem. Watching the video of failing political leaders leads to a 70% increase in the share of participants who report that personal responsibility to take action was an important factor in their decision how much to donate. While pinning down the exact causal channel is challenging (Celli, 2022), these findings suggest that positive private role models are effective because they increase norms of trust. By contrast, observing negative public role models may increase prosocial behavior because it increases people’s responsibility to “step up” and take action.

These results speak to a rapidly emerging literature on the COVID-19 crisis. The question of how to encourage prosocial behavior has received renewed interest during the pandemic (Costa-Font & Machado, 2021). Several studies show that there is a link between the perception of COVID-19 risk and prosocial behavior (Abel, Byker, Carpenter, 2021, Akesson, Ashworth-Hayes, Hahn, Metcalfe, Rasooly, 2020, Branas-Garza, Jorrat, Alfonso-Costillo, Espin, García, Kovářík, 2022). These findings are important as Campos-Mercade et al. (2021) demonstrate that prosociality predicts health behavior such as physical distancing and buying face mask during the current pandemic.3

We also contribute to the literature on role models. Role models have been extensively studied in social psychology, founded on social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, 1977) and social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954). Role models have been shown to influence others by acting as behavioral models, showing what is feasible, and inspiring people (Morgenroth et al., 2015). Our intervention is most closely related to a set of studies that specifically test the effect of role models in entertainment and news media. These have been shown to increase female autonomy (Jensen & Oster, 2009), reduce fertility (La Ferrara et al., 2012), and improve financial decision making (Berg & Zia, 2017), among other behaviors.

Last, our study speaks to the literature on public good provision. Studies have found that people consider private and public contributions to public goods as substitutes (Roberts, 1984). For example, if government funding to charitable organizations increases people tend to give less (Andreoni, Payne, 2011, De Wit, Bekkers, 2017). Our results suggest that this substitution behavior extends to the perceived ability of the government to provide public goods and confirms that it operates through a feeling of responsibility.

We want to acknowledge two limitations of the study design. First, we estimate short-term effects of role models. While immediate reactions are important and especially relevant during an acute crisis, it is important to note that effects may vary over time. Second, we use examples of specific examples of behavior that vary across several dimensions. And while we emphasize that the type of behavior we are showing applies to both Republican and Democratic officials, we are using examples of specific politicians for public role models which may be seen as partisan. It is, however, reassuring that treatment effects do not vary by participants’ political leaning.

Overall, our findings suggest that the perception of how others act in a national crisis can have large effects on people’s behavior. Sociologists believe that major national crises can present watershed moments in what people prioritize and how the social and economic system is structured. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic may affect how much people support changes in the health care system, social protection or paid sick leave legislation. Perceptions of trust and social solidarity may shape what these changes will look like.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the study design and sample. Section 3 reports results and discusses mechanisms. Section 4 concludes with a discussion.

2. Study design

2.1. Recruitment and sample characteristics

The study was conducted in early April 2020, shortly after states started to enact shelter-in-place and social distancing orders. We recruit 689 participants located in 48 U.S. states via Cloud Research.4 Table A1 (Column 2) shows baseline characteristics of our study sample. The average age of the population is 37, slightly below the national average of 38.2. 40% are female and 70% of our sample identifies as “White”, compared to the national average of 60%. 65% of participants completed a four year college degree, far above the national average of 35%.

Participants have a diverse range of political leanings: 44% describe themselves as liberal, 21% as moderate and 35% as conservative. Compared to the national average, liberals are over-represented (44% vs. 24%), while the share of conservatives is almost identical (35% vs. 37%). With respect to attitudes regarding COVID-19, 80% assert that people can effectively protect themselves from getting infected, and 35% believe that they will contract the virus. Participants are also relatively well informed - 87% agree with the statement that they have closely followed media reporting on the coronavirus.

2.2. Treatments

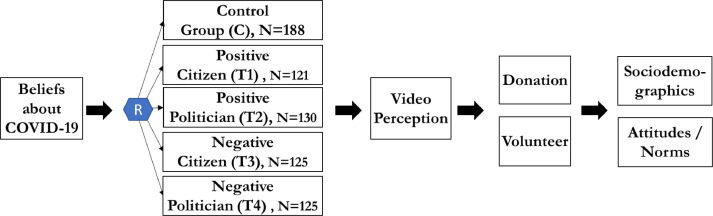

Fig. 1 summarizes the experimental design. After eliciting attitudes about the coronavirus, we randomize participants into a control group or one of four treatment groups.5 We tell all participants that we study how people react to “how the media reports about the coronavirus”. All participants then receive the following instructions: “Please watch the following 1 min video. We will then ask you to assess the quality of the reporting.”

Fig. 1.

Experimental design.

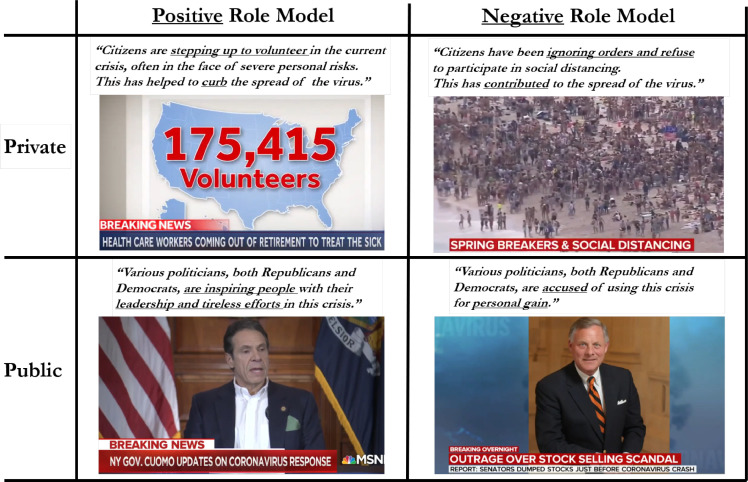

People in each treatment group read one general message followed by a short video showing news coverage of such behavior. Specifically, these include prominent example of either prosocial (from hereon referred to as positive) or anti-social (negative) behavior, committed either by private citizens or politicians. (For a transcript of the videos see Appendix B.1.) Fig. 2 summarizes the different messages and the content of the video for each treatment group. The positive private role model message reads “Citizens are stepping up to volunteer in the current crisis, often in the face of severe personal risks. This has helped to curb the spread of the virus.” It is exemplified by a video showing thousands of Americans volunteering as health workers. By contrast, the negative private role model example states that “Citizens have been ignoring orders and refuse to participate in social distancing. This has contributed to the spread of the virus.” and shows a video of multiple people defying social distancing orders and congregating in public places.

Fig. 2.

Treatment groups.

The positive public role model example states that “Various politicians, both Republicans and Democrats, are inspiring people with their leadership and tireless efforts in this crisis.” and shows an inspirational speech by New York Governor Cuomo in which he stresses that in this historic crisis you need to see both citizens and the government to “perform at their best”. The negative public role model example states that “Various politicians, both Republicans and Democrats, are accused of using this crisis for personal gain.” and documents how various (Republican and Democratic) politicians are accused of insider trading while failing to take action and publicly downplaying the health risk of the coronavirus.

All of these news clips show stories that were featured by multiple media outlets. In fact, the share of participants who state after watching the video that the content was “Not novel” ranges between 30% and 40% (Fig. B2). The videos are also perceived to be highly accurate - the share who claim the content is “inaccurate” ranges between 2% and 5% (Fig. B2). Importantly, differences in novelty and accuracy are small and not statistically significant, with the exception of the positive citizen role model is perceived to be marginally more accurate than the negative role model. All results we show in this paper are robust to controlling for perceptions of novelty and accuracy.

While most of the analysis will focus on the difference between the treatment arms, we included a control group that watches a video on the science behind the coronavirus.6 Specifically, participants in the in control group read that “Scientific research about the coronavirus is still evolving” and watch a video about the chemical composition of the coronavirus.

2.3. Balance and estimation

Columns 3 through 11 in Table A1 report mean values of the five randomly assigned groups as well as p-values () from a test of equal means of the control and respective treatment group. Of 36 tests, none is significant at the 5% level and only one difference is significant at the 10% level.7

Testing for causal inference in this context is straightforward. In the next section, we will present results graphically, comparing outcome means between randomly assigned groups. In the appendix, we also report results from OLS regressions using the following specification:

| (1) |

Outcome for participant i is regressed on the treatment group dummies. Beta coefficients measure the difference in outcomes between the treatment and control groups. We also report results controlling for baseline covariates and compute heteroskedasticity robust standard errors.

3. Results

3.1. Prosocial behavior: donation and volunteering

Two of the most commonly used metrics for individual prosocial behavior are charitable giving and volunteering. To address concerns of surveyor demand effects, we design the following two outcomes (as specified in the AEA registry). We first give participants an (unanticipated) bonus of 30 cents and give them the option to donate part of the bonus to the CDC Emergency Response Fund.8 We inform them that it funds “personal protective equipment and critical response supplies” to help “prevent the spread of the coronavirus” (see Fig. B3, top panel). After participants make their donation decision, we inform them about an organization called “VolunteerMatch”, which “helps people volunteer in the coronavirus crisis”. We record whether participants click on a link to “learn more about virtual and local volunteering opportunities” (see Fig. B3, bottom panel).

The average donation was 13.2 cents (44.1%) with 64.7% of participants donating a positive amount. 43.8% of participants click on the link to learn about volunteering opportunities. Table B1 (Col 1–4) shows how socio-demographic characteristics are correlated with these outcomes.

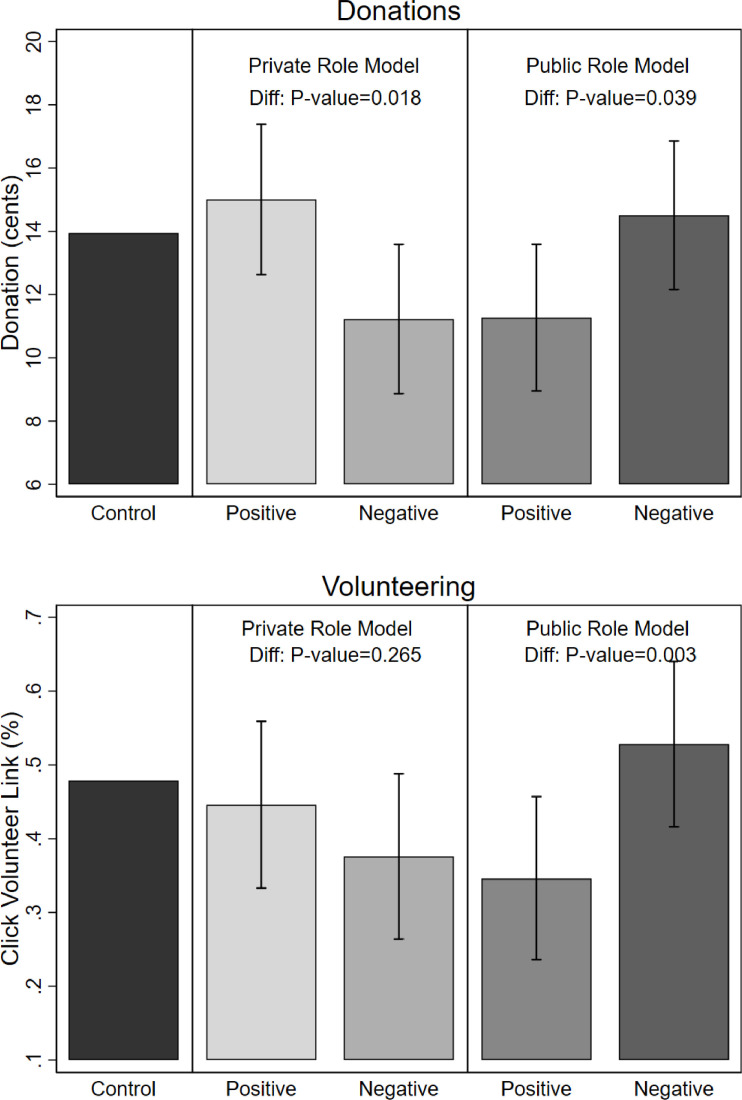

Fig. 3 shows how these two measures of prosociality differ between the randomly assigned groups. The top panel shows that people donate 3.78 cents (34%) more after receiving the positive compared to the negative private role model treatment. Importantly, the relationship reverses for public role models: people learning about the negative example donate 3.25 cents (29%) more. Both of these differences are significant at the 5% level. Table A2 (Col 1 and 2) reports corresponding regression estimates, including p-values for comparison of means between all treatment arms.

Fig. 3.

Treatment effects on donation and volunteering. Notes: The graph shows treatment effects on donations and volunteering (not controlling for covariates). 90% confidence intervals are reported.

Results for volunteering follow a similar pattern. People are 53% more likely to click on the link after seeing videos of negative compared to positive politician behavior (p-value = 0.003) Table A2 (Col 3 and 4). Conversely, they are 19% more likely to take the time to learn about opportunities after watching positive compared to negative citizen examples. While this difference is meaningful, due to a lack of statistical power it is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.265). The similarity between outcomes is all the more remarkable as donation and volunteering are not correlated () and may thus measures different dimensions of prosocial behavior.9 Last, it is noteworthy that these differences are mainly driven by the negative effects of negative private and positive public role models compared to the control group watching the science video.

3.2. Mechanisms

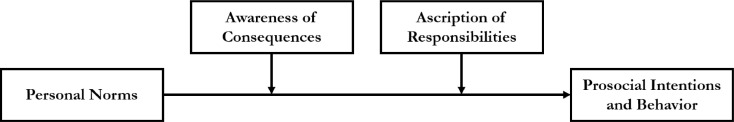

3.2.1. Framework: norm activation model

The seminal Norm Activation Model (NAM) by Schwartz (1977) posits that there are three fundamental antecedents to prosocial behavior: people need to (i) adopt personal norms, (ii) be aware of the consequences of (in)action, (iii) and feel responsible to act (See Fig. 4 ).10 Predictions of the NAM have found support in prosocial behaviors ranging from volunteering (Schwartz & Howard, 1980), donating blood (Zuckerman & Reis, 1978) and environmental protection (Schultz et al., 2005).

Fig. 4.

Norm activation model. Notes: The graph shows a simplified version of Schwartz (1977)’s Norm Activation Model based on De Groot & Steg (2009).

The NAM framework helps in gaining a deeper understanding of the results presented in the previous section. We focus on two specific mechanisms that we hypothesize are affected by observing the behavior of others during the pandemic and that have been demonstrated to affect prosocial behavior in other settings: trust norms and the ascription of responsibility. Specifically, we collected data on participants’ norm of trusting others and their sense of responsibility to act in the current crisis and test how these outcomes differ across the different role model treatments.11 There are of course many other drivers of prosocial behavior and mechanisms that may explain the experimental results.

3.2.2. Trust norms

We collect data on how much people agree with the statement that “Most people can be trusted.”, a standard metric of general trust or social capital (Putnam, 1993). The overall share in our sample who agree with the statement is 57%, similar to the share of 52% found in nationally representative surveys (Pew, 2019). Determinants of social trust are reported in Table B1.

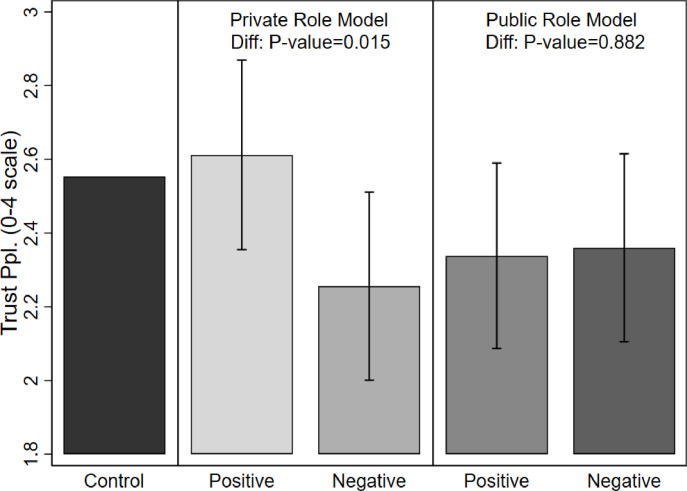

Fig. 5 shows how agreement with this statement varies across treatment arms (responses coded as 0 = strongly disagree,..., 4 = strongly agree). The average for participants watching the positive citizen video is 0.36 points (0.32 s.d.) higher than for those watching the negative citizen video (p-value: 0.015). This translates into a 11.2 percentage point (21.2%) increase in the share agreeing that most people can be trusted. By contrast, responses are very similar between the politician videos.

Fig. 5.

Trust in people. Notes: The graph shows how much people agree with the statement “Most people can be trusted” across treatment assignment (not controlling for covariates). Responses are coded as 0 = strongly disagree through 4 = strongly agree.

People’s beliefs and actions are shaped by personal norms. Fischbacher et al. (2001) conclude that the most people are conditional cooperators: their voluntary contributions to public goods are positively correlated with their ex ante beliefs about whether others also contribute.12 Kim et al. (2019) find that environments in which people are trusting of others also have high degrees of trustworthiness. Trust is thus highly predictive of conditional cooperation and can increase voluntary contributions to public goods. In the context of our study, trust can convince people to act against their narrow self-interest and behave more prosocially.

It may be surprising that watching actions of fellow citizens has a large effect on trust norms. One explanation is that in an unprecedented national crisis, people are more uncertain about how (prosocial) fellow people respond and are therefore more likely to revise their views and norms. In line with this argument, we find that people show a much stronger emotional response to seeing the private role model examples. Fig. B1 reports whether people report feeling sad or happy and stressed or calm after watching the videos (measured on a 1–10 scale). The difference in happiness between watching positive and negative examples is more than three times larger for citizens (2.6 points, 1 s.d.) than politician (0.75 points, 0.29 s.d.). Similarly, the difference for feeling stressed vs. calm is twice as large for private compared to public videos.

3.2.3. Ascription of responsibility

To better understand the rationale for people’s decision to act prosocially, we ask participants at the end of the survey “Which of the following questions most influenced your decision of how much to donate?”. One of the four questions participants can choose is “Is it my personal or the government’s responsibility to provide help?”.13 Data suggests that this statement is a proxy for whether people feel responsible to act prosocially: people who choose this answer donate 41% more than others.

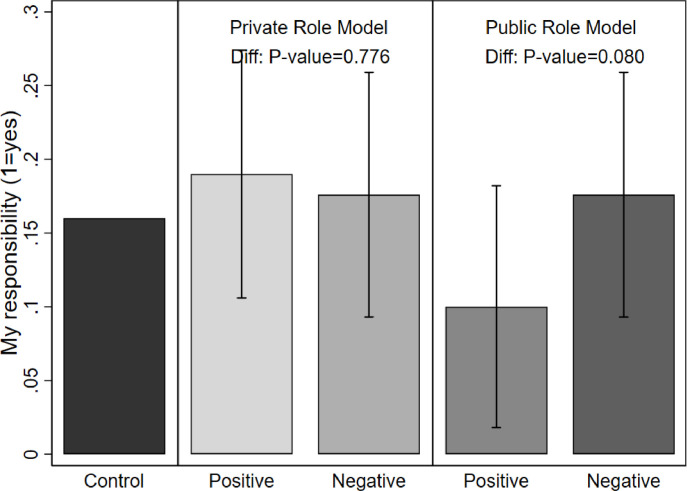

Fig. 6 shows that the feeling of responsibility does not vary across private role models. By contrast, this share is 7.6 percentage point (75%) higher for those watching the negative compared to positive public role models. While these differences are estimated imprecisely (p-value = 0.079), they suggest that positive public role models reduce a sense of responsibility. In line with this explanation, people report feeling significantly calmer after watching the video of a politician who is widely hailed for effectively managing the crisis (Fig. B1, bottom panel).

Fig. 6.

Feeling responsible. Notes: The graph shows treatment effects on respondents reporting feeling responsible to act (not controlling for covariates).

These results are consistent with traditional public good models of prosocial behavior, which predict that government funding crowds out individual support as people are mainly concerned about the overall amount of funding (Roberts, 1984). People thus consider private and public contributions as (perfect) substitutes. Studies have found support for this type of crowding out in charitable giving and other prosocial behavior.14 Our findings suggest that crowding out occurs not just for actual government contributions but also for the perceived ability of the government to provide public goods. Confronted with examples of politicians failing to manage the crisis, participants feel the need to step up and compensate for government shortcomings.

In sum, results are consistent with predictions of the NAM: Positive private role models facilitate prosocial behavior more than negative role models because they increases prosocial norms of trust while not affecting ascription of responsibility. By contrast, negative public role models do not change prosocial norms, but increase a sense of responsibility.

To further explore the role of these mechanisms, we conduct mediation analysis. One important limitation is that mediation analysis can identify the causal effect of mechanisms only under strong and untestable assumptions, most notably about the exogeneity of mediators (Celli, 2022). With these caveats in mind, Table A3 shows how treatment coefficients change when we control for mediators predicted by the NAM. For donations, the effect of private and public role models is reduced when we control for trust (Col. 1–3) and responsibility (Col. 4 and 5), respectively. Depending on the functional form, treatment coefficients drop by 10% to 25%, which is consistent with the idea that trust and responsibility are not the only relevant mechanisms. However, while the differences in treatment effects of public and private role models stop being significant at the 5% level, they are not statistically different from each other across specifications with and without mediator variables. In addition, for volunteering, we do not find that treatment effects of public role models change when we control for responsibility (Col. 6 and 7), possibly because the variation in the mediator was only marginally significant (Fig. 6). Overall, our interpretation is that these results are broadly consistent with the role of trust and responsibility, but that a conclusive test of underlying mechanisms requires additional research.

4. Discussion

In times of great uncertainty, people look at the actions of others for guidance. Our study shows that private and public role models affect people’s behavior. Examples of volunteering citizens enhances social trust and increases prosociality compared to examples of people defying social distancing. By contrast, seeing public figures mismanaging the crisis increases prosocial behavior as it strengthens people’s sense of responsibility. While failures of political leaders unequivocally worsened the crisis, they may have thus inadvertently convinced citizens to step up and take actions in their own hands, whether by delivering food, sowing masks, or donating.

We want to acknowledge four caveats of our study design. First, our main outcomes (donation and volunteering) focus on individual behavior. A different form of prosociality is to follow government orders, even if they come at a personal cost. We collect data on this by asking participants how much they agree with the statement “The government should take every necessary action, even if this leads to large losses in the stock market.” Fig. B5 shows that differences between the treatment groups are small and not statistically significant, suggesting that our intervention did not change views on support for government measures. Effects seem to be limited individual behavior. This may be unsurprising given that people tend to hold firm views about the role of government.

A second open question is whether the effects of role models persist or if we are instead merely capturing short-run effects. While our study was not designed to answer this question, it is noteworthy that in many situations, people’s decision whether to act prosocially is heavily influenced by what they observe others are doing in that moment.15 Our results suggest that this can set up a dynamic that amplifies the effects of private actions since people tend to follow the behaviors of others (Willer, 2009).

Third, we want to acknowledge that we test the effect of certain behaviors of private and public role models in the context of the early stage of the COVID pandemic. These examples differ along many dimensions including the size of the groups and the domains of behavior displayed. Follow-up work can address this limitation by choosing positive and negative cases within a domain, e.g. adherence to social distancing by private and public individuals.

Last, there are limitations to our empirical test of underlying mechanisms. We show that providing information about the behavior of others has a causal effect on trust norms and the ascription of responsibility. While we cannot conclusively test that these effects drive the overall changes in prosocial behavior, it is reassuring that these results are closely linked to predictions of the NAM, which has been validated across numerous domains of prosocial behavior. However, future research should test these mechanisms more rigorously, e.g. by employing research designs that exogenously vary these mediators (Celli, 2022), and also explore alternative mechanisms that may explain the impact of role models on prosocial behavior across a wider set of domains.

Footnotes

This paper greatly benefited from discussions with and comments by Simeon Abel, Daniel Buchman, Tanya Byker, Jeff Carpenter, Leander Heldring, and especially Thomas Chupein. Noah Whiting provided excellent research assistance. The experiment was registered under registry number AEARCTR-0005697 and IRB approval was obtained from Middlebury College. All errors and omissions are our own.

We define a role model as someone other people look to in order to help determine appropriate behaviors. Consistent with seminal work by Lockwood, Jordan, & Kunda (2002), this broad definition includes both positive role models to be imitated and negative role models whose behavior people want to avoid.

We define prosociality as acts that benefit others, including behaviors such as sharing, donating and cooperating (Batson & Powell, 2003).

For an updated overview of studies see the registry of COVID-19 studies on https://www.eeassoc.org.

Cloud Research recruits participants from MTurk, which is a popular platform for academic research. See for example DellaVigna & Pope (2018) and Abel (2022). Papers show that online experiments can be as internally and externally valid as laboratory experiments (see e.g. Horton, Rand, & Zeckhauser, 2011), even in studies where the subject pool and design is held constant (Hergueux & Jacquemet, 2015). However, recent research questions the data quality of MTurk (Gupta, Rigotti, & Wilson, 2021). To address these concerns we use the platform Cloud Research, which pre-screens MTurk participants and thus leads to more reliable data (Gupta, Rigotti, & Wilson, 2022).

Fig. 1 shows the sample sizes for each treatment arm. The size of the control group is 50% larger to increase statistical power for a comparison between control group and pooled treatment arms.

We also piloted a “pure” control group that did not watch any video. Results between these two groups were similar so we decided to include the video as a form of placebo treatment.

Characteristics between treatment groups are also balanced. For example, p-values for a test of joint significance are 0.48 and 0.47 for differences between positive and negative private and public role models, respectively.

The CDC Foundation is an independent, nonprofit organization supporting the work of the Center for Disease Control (CDC). While the CDC is a United States federal agency, it enjoys broad public trust. A recent poll found that 77% trust the CDC.

Table B1 shows that some people treat volunteering and donations as substitutes. E.g., those who are concerned about contracting COVID-19 donate more but are less likely to show interest in volunteering.

There is disagreement on whether the awareness of consequences and acscription of responsibility act as mediators (see De Groot & Steg, 2009 for a discussion.)

In collecting outcomes, we inform people about the consequences of their action. For example, the donation question mentioned that “funds are used to buy equipment to stop the spread of the virus”. All participants should therefore be aware of consequences of prosociality and it is thus unlikely that this mechanism can explain differential treatment effects. Other determinants of prosocial behavior include the identification of actions to address needs, which we also provide to participants in our study (De Groot & Steg, 2009).

Thöni & Volk (2018) find in a meta analysis that findings by Fischbacher et al. (2001) are robust to a range of game experimental parameters.

Other answers include “Does that small amount make a difference?” (26.9%), “Do I have enough resources myself in the current situation?” (36.7%), and “How much do people expect me to give?” (8.2%).

In a meta-analysis, De Wit & Bekkers (2017) find that a one dollar increase in government support for charitable organizations decreases private donations by about 64 cents. Other studies find that this form of crowding out also applies to volunteer labor (Duncan, 1999). There is, however, evidence that at least part of this crowding out is due to reduced fundraising by organizations (Andreoni & Payne, 2011).

For example, Reyniers & Bhalla (2013) find that people’s donation behavior is strongly influenced by what they learn others are donating.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Balance table.

| Sample |

Control mean |

T1 pos cit |

T2 pos gov |

T3 neg cit |

T4 neg gov |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | Mean | ||||||

| Age | 689 | 37.2 | 36.6 | 38.7 | 0.15 | 36.8 | 0.83 | 36.8 | 0.84 | 37.4 | 0.5 |

| Female | 689 | 0.4 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.22 |

| White | 679 | 0.7 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.14 | 0.77 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.65 | 0.52 |

| College | 679 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.94 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.35 |

| Liberal | 689 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 0.88 | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.5 |

| Conservative | 689 | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.3 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.58 |

| Follow Media | 689 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.45 | 0.88 | 0.31 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.87 | 0.51 |

| Concern Virus | 689 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.94 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 0.35 | 0.76 |

| Trust Protection | 689 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.31 | 0.86 | 0.37 | 0.75 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.38 |

| Joint Significance | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.53 | |||||||

Notes: P-values () are reported for a comparison of means with the control group. Characteristics are also balanced between treatment arms. P-values for tests of joint significance are: 0.54 (T1 = T2), 0.59 (T1 = T3), 0.53 (T1 = T4), 0.15 (T2 = T3), 0.34 (T2 = T4), 0.82 (T3 = T4).

Table A2.

Results: donations, volunteering, trust, responsibility.

| Donation |

Volunteering |

Trust People |

Responsibility |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Positive Private (T1) | 1.062 | 0.778 | 0.032 | 0.047 | 0.058 | 0.043 | 0.031 | 0.031 |

| (1.467) | (1.480) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.131) | (0.129) | (0.045) | (0.045) | |

| Positive Public (T2) | 2.677* | 2.801** | 0.133** | 0.128** | 0.215* | 0.180 | 0.060 | 0.057 |

| (1.407) | (1.413) | (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.125) | (0.128) | (0.038) | (0.038) | |

| Negative Private (T3) | 2.725* | 2.905** | 0.103* | 0.098* | 0.297** | 0.311** | 0.016 | 0.014 |

| (1.396) | (1.403) | (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.126) | (0.126) | (0.043) | (0.044) | |

| Negative Public (T4) | 0.562 | 0.283 | 0.049 | 0.038 | 0.193 | 0.197 | 0.016 | 0.019 |

| (1.421) | (1.411) | (0.058) | (0.058) | (0.132) | (0.130) | (0.043) | (0.044) | |

| Controls | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y |

| Observations | 682 | 672 | 689 | 679 | 689 | 679 | 689 | 679 |

| Rsquare | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Sample Mean | 13.24 | 13.24 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 2.43 | 2.43 | 0.16 | 0.16 |

| Std Dev | 12.37 | 12.37 | 0.497 | 0.497 | 1.128 | 1.128 | 0.367 | 0.367 |

| T1 = T2 | 0.020 | 0.027 | 0.105 | 0.195 | 0.059 | 0.124 | 0.043 | 0.050 |

| T1 = T3 | 0.018 | 0.022 | 0.264 | 0.420 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.776 | 0.732 |

| T1 = T4 | 0.757 | 0.757 | 0.200 | 0.181 | 0.094 | 0.101 | 0.776 | 0.808 |

| T2 = T3 | 0.975 | 0.947 | 0.621 | 0.627 | 0.555 | 0.354 | 0.079 | 0.105 |

| T2 = T4 | 0.038 | 0.047 | 0.003 | 0.007 | 0.882 | 0.905 | 0.079 | 0.084 |

| T3 = T4 | 0.034 | 0.038 | 0.015 | 0.031 | 0.475 | 0.426 | 1.000 | 0.918 |

Notes: The dependent variable in Column 1 and 2 measures the amount (in cents) out of the bonus of 30 cents that participants donate towards the CDC. The dependent variable in col. 3 and 4 is a binary measure of whether participants click on the volunteering link. Col. 5 and 6 measure whether people agree with the statement that most people can be trusted, with answers coded from strongly disagree = 0 to strongly agree = 4. Col. 7–8 measure whether people report that the question of personal responsibility was most important in their donation decision. All estimations are OLS. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. The mean of the dependent variable for the control group is reported. The bottom rows present p-values from a test of equal coefficients for the different treatment arm combinations. * , ** , ***

Table A3.

Mediation analysis.

| Donation |

Volunteering |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| Pos. Private (T1) | 0.825 | 0.760 | 0.801 | ||||

| (1.462) | (1.446) | (1.443) | |||||

| Neg. Private (T3) | 2.720** | 2.233 | 2.069 | ||||

| (1.378) | (1.389) | (1.396) | |||||

| Pos. Public (T2) | 2.196* | 1.863 | 0.094* | 0.096** | |||

| (0.084) | (1.243) | (0.048) | (0.048) | ||||

| Neg. Public (T4) | 1.043 | 0.998 | 0.088** | 0.088** | |||

| (1.259) | (1.256) | (0.051) | (0.051) | ||||

| Mediator | No | Trust | Trust | No | Resp. | No | Resp. |

| Mediator Fn. Form | Linear | Non-par. | Linear | Linear | |||

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Observations | 672 | 672 | 672 | 682 | 682 | 689 | 689 |

| Rsquare | 0.053 | 0.072 | 0.08 | 0.007 | 0.027 | 0.012 | 0.013 |

| T1 = T3 | 0.025 | 0.057 | 0.068 | ||||

| T2 = T4 | 0.038 | 0.068 | 0.003 | 0.003 | |||

Notes: This table reports how treatment coefficients change when we control for mediating variables. Regressions include the full set of treatment variables but for readability only treatment coefficients are reported for treatment arms that affect the respective mediator. We furthermore restrict regressions to specifications for which we observe significant treatment effects. For trust, we estimate linear and non-parametric models with dummy variables for each response option in the Likert scale. For responsibility, we estimate models with the binary mediator. All estimations are OLS. Robust standard errors are in parentheses. The bottom rows present p-values from a test of equal coefficients. * , ** , ***

Supplementary material

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.socec.2022.101942

Appendix B. Supplementary materials

Supplementary Raw Research Data. This is open data under the CC BY license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

References

- Abel M. Do workers discriminate against female bosses? Journal of Human Resources. 2022:1120–1131. [Google Scholar]

- Abel M., Byker T., Carpenter J. Socially optimal mistakes? Debiasing COVID-19 mortality risk perceptions and prosocial behavior. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 2021;183:456–480. [Google Scholar]

- Akesson J., Ashworth-Hayes S., Hahn R., Metcalfe R.D., Rasooly I. Technical report. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. Fatalism, beliefs, and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni J., Payne A.A. Is crowding out due entirely to fundraising? Evidence from a panel of charities. Journal of Public Economics. 2011;95(5–6):334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A., Walters R.H. vol. 1. Prentice-Hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ; 1977. Social learning theory. [Google Scholar]

- Batson C.D., Powell A.A. Handbook of psychology. 2003. Altruism and prosocial behavior; pp. 463–484. [Google Scholar]

- Berg G., Zia B. Harnessing emotional connections to improve financial decisions: Evaluating the impact of financial education in mainstream media. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2017;15(5):1025–1055. [Google Scholar]

- Branas-Garza P., Jorrat D., Alfonso-Costillo A., Espin A.M., García T., Kovářík J. Exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic and generosity. Royal Society Open Science Journal. 2022;9(1):9210919. doi: 10.1098/rsos.210919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Mercade P., Meier A.N., Schneider F.H., Wengström E. Prosociality predicts health behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics. 2021;195:104367. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli V. Causal mediation analysis in economics: Objectives, assumptions, models. Journal of Economic Surveys. 2022;36(1):214–234. [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Font J., Machado S. How can policy interventions encourage pro-social behaviours in the health system? LSE Public Policy Review. 2021;1(3) [Google Scholar]

- De Groot J.I., Steg L. Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;149(4):425–449. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.149.4.425-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Wit A., Bekkers R. Government support and charitable donations: A meta-analysis of the crowding-out hypothesis. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2017;27(2):301–319. [Google Scholar]

- DellaVigna S., Pope D. Predicting experimental results: Who knows what? Journal of Political Economy. 2018;126(6):2410–2456. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan B. Modeling charitable contributions of time and money. Journal of Public Economics. 1999;72(2):213–242. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7(2):117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbacher U., Gächter S., Fehr E. Are people conditionally cooperative? Evidence from a public goods experiment. Economics Letters. 2001;71(3):397–404. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Rigotti L., Wilson A. The experimenters’ dilemma: Inferential preferences over populations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.05064. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Gupta N., Rigotti L., Wilson A. Technical report. 2022. Preferences over experimental populations. [Google Scholar]

- Hergueux J., Jacquemet N. Social preferences in the online laboratory: Arandomized experiment. Experimental Economics. 2015;18(2):251–283. [Google Scholar]

- Horton J.J., Rand D.G., Zeckhauser R.J. The online laboratory: Conducting experiments in a real labor market. Experimental Economics. 2011;14(3):399–425. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R., Oster E. The power of TV: Cable television and women’s status in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2009;124(3):1057–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Putterman L.G., Zhang X. Technical report. 2019. Trust, beliefs and cooperation: An experiment. [Google Scholar]; Working Paper

- La Ferrara E., Chong A., Duryea S. Soap operas and fertility: Evidence from Brazil. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2012;4(4):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood P., Jordan C.H., Kunda Z. Motivation by positive or negative role models: Regulatory focus determines who will best inspire us. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(4):854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenroth T., Ryan M.K., Peters K. The motivational theory of role modeling: How role models influence role aspirants’ goals. Review of General Psychology. 2015;19(4):465–483. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom E. Games, groups, and the global good. Springer; 2009. Building trust to solve commons dilemmas: Taking small steps to test an evolving theory of collective action; pp. 207–228. [Google Scholar]

- Pew . Technical report. Pew Research Center; 2019. Trust and distrust in America. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam R. The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. The American Prospect. 1993;13(4):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Reyniers D., Bhalla R. Reluctant altruism and peer pressure in charitable giving. Judgment and Decision Making. 2013;8(1):7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts R.D. A positive model of private charity and public transfers. Journal of Political Economy. 1984;92(1):136–148. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz P.W., Gouveia V.V., Cameron L.D., Tankha G., Schmuck P., Franěk M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. Journal of Cross-cultural Psychology. 2005;36(4):457–475. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S.H. Normative influences on altruism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1977;10(1):221–279. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S.H., Howard J.A. Explanations of the moderating effect of responsibility denial on the personal norm-behavior relationship. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1980;43(4):441–446. [Google Scholar]

- Thöni C., Volk S. Conditional cooperation: Review and refinement. Economics Letters. 2018;171:37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Willer R. Groups reward individual sacrifice: The status solution to the collective action problem. American Sociological Review. 2009;74(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M., Reis H.T. Comparison of three models for predicting altruistic behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1978;36(5):498. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Raw Research Data. This is open data under the CC BY license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/