Abstract

Retrograde bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ) has served as a paradigm to study TGF-β-dependent synaptic function and maturation. Yet, how retrograde BMP signaling transcriptionally regulates these functions remains unresolved. Here, we uncover a gene network, enriched for neurotransmission-related genes, that is controlled by retrograde BMP signaling in motor neurons through two Smad-binding cis-regulatory motifs, the BMP-activating (BMP-AE) and silencer (BMP-SE) elements. Unpredictably, both motifs mediate direct gene activation, with no involvement of the BMP derepression pathway regulators Schnurri and Brinker. Genome editing of candidate BMP-SE and BMP-AE within the locus of the active zone gene bruchpilot, and a novel Ly6 gene witty, demonstrated the role of these motifs in upregulating genes required for the maturation of pre- and post-synaptic NMJ compartments. Our findings uncover how Smad-dependent transcriptional mechanisms specific to motor neurons directly orchestrate a gene network required for synaptic maturation by retrograde BMP signaling.

INTRODUCTION

In metazoans, transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) members play key roles in the developing and mature central nervous system (CNS) to orchestrate a wide variety of processes including neurogenesis, neuronal specification, synaptic growth as well as stability, neurotransmission, homeostasis and plasticity (1,2). Commensurate with its critical neuronal functions, deregulation of the TGF-β pathway is linked with multiple severe human neurological disorders (3,4). Despite these roles, the downstream molecular and transcriptional mechanisms regulated by neuronal TGF-β signaling remain largely unknown.

The Drosophila neuromuscular junction (NMJ) provides an ideal model for determining how TGF-β signaling coordinates complex synaptic functions and its downstream effector target genes. At the growing larval NMJ, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), a branch of TGF-β ligands, trigger retrograde BMP signaling and downstream transcription in motor neurons that are essential for synaptic function and maturation (5–7). Secreted at the NMJ by muscle cells and motor neurons, the BMP ligand Glass bottom boat (Gbb) binds a presynaptic receptor complex composed of the type II BMP receptor kinase Wishful Thinking (Wit) and the type I BMP receptor kinases, Thickveins (Tkv) and Saxophone (Sax) (5,6,8). Through dynein-dependent retrograde trafficking, this complex is transported along the axon and phosphorylates Mother against dpp (Mad), a transcription factor (9). Phospho-Mad (pMad) associates with Medea (Med) and accumulates in the nucleus to bind BMP-responsive elements (BMP-RE) and to regulate downstream gene expression required for BMP-dependent synaptic functions (8,10,11). The pMad/Med transcription factor activity is postulated to control most BMP-dependent synaptic functions at the NMJ because most of the synaptic defects observed in loss of function mutants for gbb, tkv, sax and wit are also present in Mad and Med mutants, as well as upon overexpression of DNA-binding defective Mad in motor neurons (5,8,11,12).

Despite the critical importance of BMP-dependent transcription in fly motor neurons, only two BMP-activated target genes, trio and twit, have been confirmed as effectors of NMJ function and maturation. However, overexpression of either of these genes in wit mutants only partially rescued the synaptic defects, implicating roles for other unknown BMP targets (13,14). Additionally, it is interesting to note that our current understanding on the role of these BMP-regulated genes in NMJ growth and function is only based on the analysis of null mutant phenotypes. Therefore, the generation of mutants that selectively test the contribution of BMP input on the expression of these target genes would better demonstrate how retrograde BMP signaling regulates synaptic functions.

We recently reported that the pMad/Med complex directly binds BMP-activating elements (BMP-AEs) to upregulate BMP target genes in fly motor neurons in the larval ventral nerve cord (VNC) (10). Pioneering studies performed in other Drosophila tissues revealed that BMP-dependent activation is also mediated by an indirect de-repression mechanism (15,16). In this case, the absence of BMP signaling allows expression of the transcriptional repressor encoded by brinker (brk), which represses BMP-activated target genes (17–19) (Figure 1A). In the presence of BMP signaling, brk transcription is repressed by the direct binding of the pMad/Med complex together with the corepressor Schnurri (Shn) at BMP-silencer elements (BMP-SEs). Thus, BMP signaling indirectly upregulates target genes in those tissues (20,21). Notably, in addition to brk, the BMP-SE mediates the direct BMP-dependent repression of numerous genes in other tissues (22–26). In motor neurons, any role for the BMP-SE in direct gene repression is unknown.

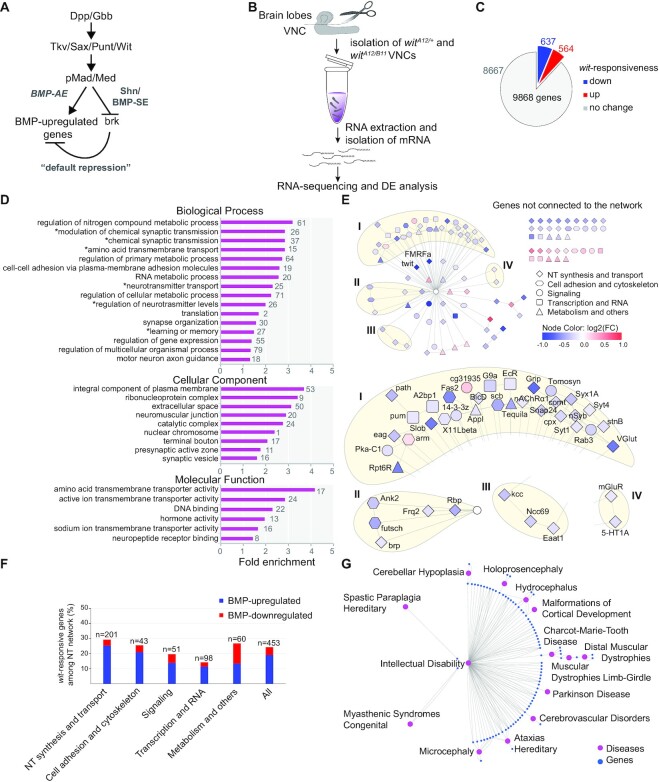

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic of the canonical BMP signaling pathway in Drosophila, noting the direct activation arm via BMP-AE and the default repression arm via BMP-SE to repress the brk transcriptional repressor. (B) Schematic of the RNA-seq experiment to examine differential gene expression (DE) between control and wit null VNCs, with the brain lobes removed. (C) The number of genes that were downregulated (blue), upregulated (red) or not affected (gray) in wit nulls. (D) PANTHER Gene Ontology (GO) over-representation analysis for the 637 genes upregulated by BMP signaling. The number of over-represented genes within each term are provided next to each bar. The fold enrichment is the −log10(P-value). (E) A neurotransmission network of 453 genes is shown, with blue and red nodes indicating genes that are BMP-upregulated and downregulated, respectively. The color intensity of the nodes defines the log2 (fold change) of DE. All wit-unresponsive genes are indicated as a single central white node. Genes are classified based on their function as shown beside the network. Four major interaction clusters are shown (I–IV). (F) Bar graph showing the proportion of wit-responsive genes in each functional category shown in panel (E). (G) Disease to gene interaction network for the 1086 putative human orthologs using DisGeNET analysis.

Here, we use computational DNA motif discovery, in vivo reporter assays and genome engineering to identify the downstream gene regulatory program controlled by BMP signaling in motor neurons. We show that BMP signaling upregulates a network of genes, including many with established synaptic functions and/or implicated in neurological disorders. Most of those BMP-upregulated genes harbor conserved BMP-REs in their locus, suggesting that these target genes are directly regulated. Surprisingly, we find that BMP-SEs operate as activator motifs for neuronal gene expression, as opposed to their strict silencer function in other tissues. Finally, targeted mutation of BMP-RE motifs demonstrates the discrete requirement of BMP transcriptional input to the active zone scaffolding gene bruchpilot (brp) and to a novel gene, without maturity (witty), in the control of NMJ maturation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains

Flies were reared on standard medium at 25°C, 70% humidity. UAS-cg14274-dsRNA (TRIP.JF03191; BL#28763), UAS-mCherry (Valium10; BL#35787) 6935-hid (BL#25679), Gal4221w− (BL#26259), Df(2L)BSC200 (BL#9627), Df(2R)BSC408 (BL#24912), hs-Cre (BL#851), OK6-gal4 (BL#64199), repo-gal4 (BL#7415), brkXA(BL#58792) (17), tub-PBac (BL#8283), witA12 and witB11 (BL#5173 and #5174) (5) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila stock center.

Genotypes by figure

Figure 3A. w;;Van75,80nlsLacZ, witA12/+.w;;Van65nlsLacZ, witA12/Van65nlsLacZ. Figure 3B. w;;Van75,80nlsLacZ, witA12/+.w;;Van65nlsLacZ, witA12/Van65nlsLacZ.w;;Van75,80nlsLacZ, witA12/witB11. w;;Van65nlsLacZ, witA12/Van65nlsLacZ,witB11. Figure 3E. w;;Van75,80nlsLacZ/+.w;;Van65nlsLacZ/Van65nlsLacZ.w;;Van75,80ΔmadnlsLacZ/+.w;;Van65ΔmadnlsLacZ/ Van65ΔmadnlsLacZ. Figure 3F. w;;Van75nlsLacZ/+.w;;Van75SE>AEnlsLacZ/+.w;Van26nlsDsRed/+.w;Van26AE>SEnlsDsRed/+. Figure 4. w;;Van36nlsLacZ/+.w;;Van36 AE>SEnlsLacZ/+. Figure 5A. w;Shn::HA/Shn::HA;repo-gal4/UAS-nlsEGFP. Figure 5B-C. w;ok6-Gal4,UAS-nlsEGFP;Van75nlsLacZ/+. w;ok6-Gal4,UAS-nlsEGFP; UAS-ShnCT/Van75nlsLacZ.w;ok6-Gal4,UAS-EGFPnls;UAS-ShnCT/Van75SE>AEnlsLacZ. Figure 5E,F. yw/Y;Van26nlsDsRed/+.yw,brkXA/Y;Van26nlsDsRed/+. Figure 6B–D. w; brpBMP-SE/Df(2R)BSC408. w; brp BMP-SEΔmad/Df(2R)BSC408. Figure 6F,G. w.w; Ly6Del/Ly6Del. w;R-Ly6AE/R-Ly6AE.w; R-Ly6AEΔmad/R-Ly6AEΔmad. Figure 6H,I. UAS-Dicer2/w; +/Ly6Del;UAS-mCherry/+. UAS-Dicer2/w; +/Ly6Del; elav-Gal4/UAS-dsRNA-witty.

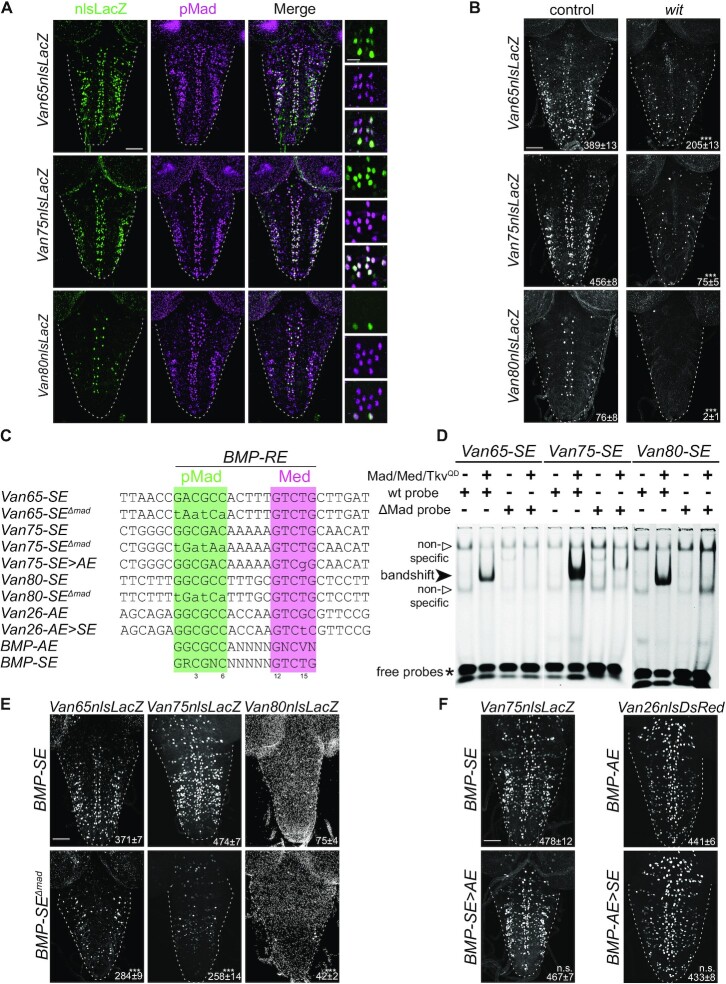

Figure 3.

(A) Reporter activity (anti-nuclear β-gal immunoreactivity; green), from three genomic fragments containing conserved BMP-SE, is localized primarily in motor neurons as revealed by pMad co-staining (magenta). (B) Reporter activity of these three genomic fragments is reduced in wit nulls. The mean ± SEM number of nuclei per VNC expressing the reporter is indicated (inset). (C) Sequences of the consensus, wildtype and mutant BMP-SE and BMP-AE motifs, examined in the other panels, noting the position number of specific nucleotides in the motif, below. The sequences shown in green and purple are predicted to be bound by pMad and Med as previously shown. (D) EMSA for three IRDye700-labeled BMP-SE wild-type and mutated (ΔMad) sequences with lysates from S2 cells transfected with the indicated plasmids. A strong band shift for each labeled wild-type probe was only obtained in lanes loaded with S2 cell lysate transfected with Mad, Med and TkvQD (MMT). The labeled mutated probes did not generate a band shift under the same conditions. Two weak band shifts that we consider non-specific with regard to Smad binding were also obtained for each probe regardless of the absence or presence of MMT or wild-type and mutated probes. (E) Reporter activity driven from three wit-responsive genomic fragments in which the BMP-SE is either wild-type or mutated (ΔMad) at the pMad binding site indicated in panel (C). Reporter activity of mutated genomic fragments was reduced. (F) Reporter activity (anti-nuclear β-gal immunoreactivity or DsRed expression) driven from two wit-responsive genomic fragments after motif conversion as indicated in panel (C). These mutations did not disrupt reporter activity. ***P < 0.001; n.s. not significant (two-sided unequal variance Student’s t-test) with n = 5–9 VNCs per genotype. Scale bars of panels A,B,E,F: 50 μm; A, inset: 10 μm.

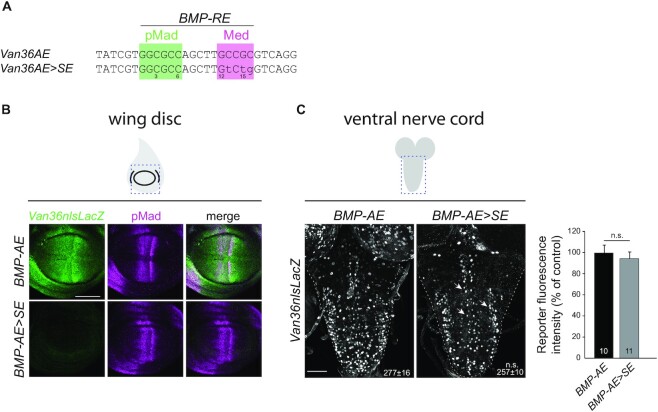

Figure 4.

(A) Sequences of the wild-type and converted BMP-AE examined in panels (B,C). (B,C) Comparison of reporter activity (anti-nuclear β-gal immunoreactivity) in the wing disc and VNC, driven from a wit-responsive genomic fragment containing either a BMP-AE, or a BMP-AE > SE conversion. (B) In the wing disc, wild-type reporter expression (green) mirrored BMP signaling activity as revealed by anti-pMad immunolabeling (magenta). Activity of the converted BMP-AE > SE reporter was strongly downregulated. (C) In the VNC, motor neuron expression (white arrows) of the BMP-AE > SE reporter remained unaffected. The mean ± SEM number of motor neuron nuclei per VNC expressing the reporter is indicated (inset). n.s., not significant (two-sided unequal variance Student’s t-test) with n = 10–11 VNCs per genotype. Scale bars of panels (B,C): 50 μm.

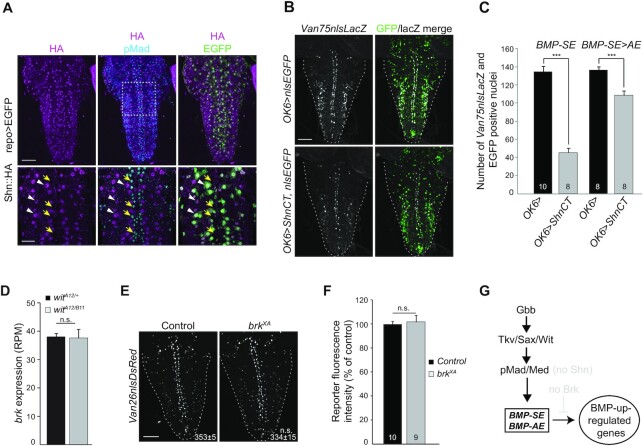

Figure 5.

(A) Expression of an endogenous HA-tagged shn (shn::HA) allele (anti-HA immunolabeling) is restricted to repo-positive glia (green, white arrowheads) and neurons with no BMP signaling as revealed by the absence of pMad co-staining (blue, yellow arrows). (B) Reporter activity (anti-nuclear β-gal immunoreactivity) driven from the wit-responsive genomic fragment Van75 with a BMP-SE in control and ShnCT misexpressing motor neurons. (C) Quantification of reporter activity loss of the Van75 genomic fragment containing either a wildtype BMP-SE or a converted BMP-SE> AE motif. The number of nuclei per VNC that are positive for EGFP and the Van75 reporter is represented by mean ± SEM. Misexpression of ShnCT strongly downregulated the activity of the reporter containing the BMP-SE, but not with the BMP-AE. (D) Brk transcription is not altered in wit null VNCs. The RPM (reads per million) per biological replicate is represented by the mean ± SEM. n = 4 biological replicates for each RNA-seq experimental condition. (E) Nuclear DsRed reporter expression driven from the wit-responsive Van26 reporter containing a BMP-AE in control and brkXA mutants. The mean ± SEM number of nuclei per VNC expressing the reporter is indicated (inset). (F) Quantification of fluorescence intensities per VNC for genotypes shown in panel (E) is represented by mean ± SEM. The activity of the Van26 reporter is not altered in brkXA. (G) In this model, the BMP-AE and BMP-SE mediate the direct upregulation of BMP target genes by BMP signaling in motor neurons, in the absence of Brk and Shn (light gray). ***P< 0.001; n.s., not significant (two-sided unequal variance Student’s t-test for C,E,F and Wald test, P-value adjusted with Benjamini–Hochberg for D) with n = 8–10 VNCs per genotype. Scale bars of panels A,B,E: 50 μm; A, magnification: 25 μm.

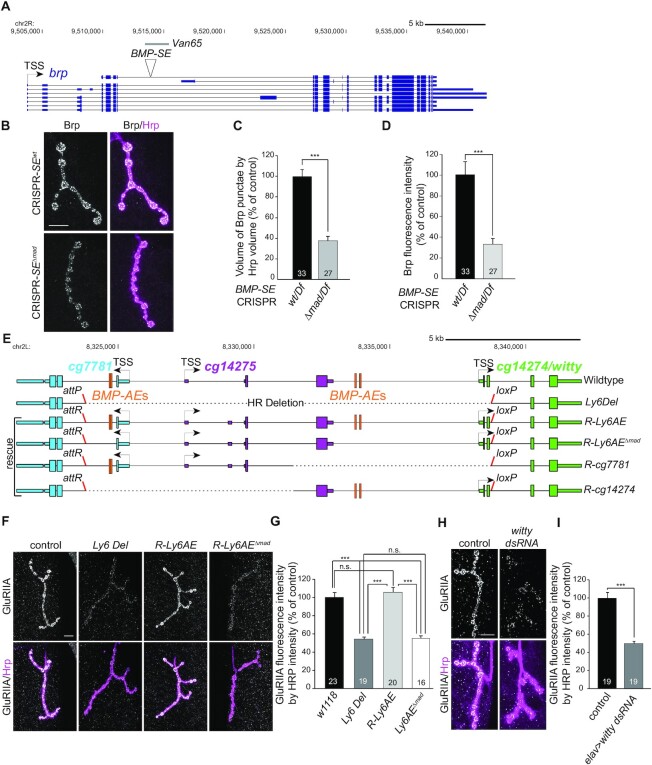

Figure 6.

(A) Annotated UCSC genome browser image showing the bruchpilot (brp) locus with the BMP-SE and the wit-responsive genomic fragment used for reporter analysis. (B) Anti-Brp (gray) immunoreactivity at NMJ4 in wandering third instar larvae for which the BMP-SE is either wild-type or mutated to prevent pMad binding (ΔMad). Neurons are labeled by anti-HRP (magenta). These BMP-SE alleles are hemizygous over a genomic deficiency that encompasses the brp locus. (C, D) Quantification of Brp punctae volume (C) and intensity (D) reduction in BMP-SE mutants is represented by mean ± SEM. ***P< 0.001 (two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test). (E) Annotated UCSC genome browser image showing the Ly6 gene locus with the four BMP-AEs, the region deleted (HR Deletion) in the Ly6 allele (Ly6Del), and the four genomic rescues in which the locus was replaced by either the wild-type sequence (R-Ly6AE), the wild-type sequence with mutations in the four BMP-AEs (R-Ly6AEΔMad), or a partial fragment rescuing either cg7781 (R-cg7781) or cg14274 (R-cg14274). The attP and loxP sites used for genome engineering are shown. (F) Representative NMJ4 immunostained for GluRIIA (gray) shown for controls, Ly6Del mutants, and in R-Ly6AE and R-Ly6AEΔMad rescue. Anti-HRP is magenta. (G) Immunofluorescence intensities for genotypes shown in panel (F) are represented by mean ± SEM. The loss of anti-GluRIIA immunoreactivity in Ly6Del mutants is rescued in R-Ly6AE, but not in R-Ly6AEΔMad, ***P< 0.001, n.s., not significant (one-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey HSD test). (H) Representative NMJ4 immunostained for GluRIIA following neuronal RNAi knockdown of witty using the elav-Gal4 driver. (I) Quantification of GluRIIA immunofluorescence after RNAi knockdown of neuronal witty. ***P< 0.001 (two-sided unequal variance Student’s t-test). Scale bars of panels B,F,H: 10 μm.

RNA-seq analysis and enrichment of BMP-AE and BMP-SE motifs near BMP-regulated genes

For a detailed description of our multi-pipeline RNA-seq analysis, refer to (10). Differential expression between control and wit null mutant wandering third instar larval VNCs is represented as log2 fold change.

To test for enrichment of BMP-AE and BMP-SE motifs as well as bcd-responsive fragments (27) to BMP-responsive genes in the CNS and the embryonic blastoderm, the location of both BMP-RE motif types (BMP-AE with BLS > 0.6 and BMP-SE with BLS > 0.7) and the bcd-responsive fragments was mapped with the BMP-responsive genes identified by our RNA-seq and by previous work (28). The number of BMP-RE motifs or bcd-responsive fragments within 50 kb of the transcriptional start site of a BMP-responsive gene was then counted. Statistical significance of the enrichment was calculated using Pearson's Chi square test for count data in R (function chisq.test) with continuity correction without correcting for multiple testing (http://www.R-project.org/).

GO term over-representation analysis

Analysis of the DE genes in wit null mutant ventral nerve cord (VNC) was performed using our previous RNA-seq (10). Gene ontology over-representation analysis of the wit DE genes was carried out using PANTHER (http://pantherdb.org/) (29,30) and DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov) (31,32). For PANTHER, the Fisher’s exact test and Bonferroni correction for multiple testing was applied. For DAVID, the Benjamini correction was used to determine the P-value.

Construction of a neurotransmission gene network

The 453 genes that relate to neurotransmission identified in PANTHER were used to build a neurotransmission gene network in STRING (https://string-db.org/) (33). The meaning of network edges and the active interaction sources were defined as evidence, experiments and databases, respectively. The neurotransmission gene network was then exported into Cytoscape (v3.8.0) and displayed using the yFiles organic layout (34).

DisGeNET analysis of the BMP-upregulated genes

We used DIOPT (https://www.flyrnai.org/diopt) (35) and Ensembl ortholog (36) prediction tools to retrieve the 1086 putative human orthologs of the 637 Drosophila BMP-upregulated genes identified in our RNA-seq, using the ‘Return only best match’ option. We used the DisGeNET application in Cytoscape (v3.8.0) (37–39) to build a disease to gene interaction network, applying the curated source with the strong evidence level to identify human orthologs involved in nervous system diseases. The yFiles radial layout was then used to display the network. We used the MGI Mammalian Phenotype Level 4 2019 in Enrichr (https://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr) (40–42) to determine any enrichments of the 1086 putative human orthologs for neuronal and synaptic mice phenotypes.

BMP-SE identification and prioritization

Using merMer (http://www.insilicolabs.com/cgi-bin/style.cgi) (43), we identified 385 occurrences matching the consensus BMP-SE motif (GRCGNCN5GTCTG) in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Of these, we selected 261 BMP-SE motifs located in intronic, UTR and intergenic regions and filtered them by the controlled Branch Length Score (BLS) to motif confidence to evaluate phylogenetic conservation over 12 Drosophila species with the assistance of the Stark group. A BLS confidence score based on the relative conservation of the BMP-SE motif and control motifs was assigned (Supplementary Figure S3). To generate reporter constructs for in vivo testing of enhancer activity, we first selected all 20 BMP-SEs with a motif confidence ≥0.9 directly located within 12 kb of a wit-responsive gene. To obtain more instances to test, we also selected 14 additional BMP-SEs: (i) with a motif confidence ≥0.8 that locates within 12 kb of a strong wit-responsive gene (log2(FC) ≥ 0.6), (ii) with a motif confidence of 0.8 that is ‘paired’ with another BMP-SE of motif confidence ≥0.9 within 12 kb of the same annotated gene locus, (iii) with a motif confidence ≥0.8 located within 12 kb of a BMP-repressed gene or (iv) with a motif confidence ≥0.8 located within 12 kb of a BMP-upregulated gene of interest. The initial computational analysis used the Release 3 of the D. melanogaster reference genome (Dm3) (44). To calculate the proximity of BMP-SE, BMP-AE and bcd genomic fragment (27) to BMP-regulated genes, the coordinates of the motifs were later converted to Release 6 (Dm6) (45). Wit-responsiveness of neuronally expressed genes was determined using our previous RNA-seq (10).

Drosophila DNA constructs and transgenic flies

To generate reporter constructs, we used the same approach as described previously (10) using primers reported in Supplementary Table S1. Mutagenesis was carried out using the Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB) or by SOE-PCR using primers designed to introduce the specific mutations. All constructs were verified by sequencing.

For fly transgenesis, reporter constructs were inserted via PhiC31 integrase-mediated site-specific integration at insertion site attP40 (25C6) on chromosome 2 or attP2 (68A4) on chromosome 3 by Genetics Services Inc. (MA, USA) and Rainbow Transgenics Flies Inc. (CA, USA).

Genome engineering by CRISPR and ends-out targeting

The endogenously tagged HA::Brk and Shn::HA alleles were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 genome engineering in combination with PhiC31integrase-mediated site-specific recombination. Briefly, the coding sequence and parts of the 5'UTR and 3'UTR of brk and shn were removed using Cas9, guide RNAs (gRNAs) and homology arms (HAs) (brk: 5': chrX: 7 307 101–7 308 108; 3': chrX: 7 310 681–7 311 658; shn: 5': chr2R: 11 206 075–11 207 317; 3': chr2R: 11 216 395–11 217 557) flanking the guide RNAs recognition sites. The gRNAs and HAs were, respectively, cloned into the pCFD4 and pHD-dsRed-attP plasmid (Addgene) (46). Plasmids were co-injected into nos-Cas9 embryos, and modified flies were identified in the progeny using the 3xP3::dsRed marker, which was subsequently removed by Cre recombinase. The deleted regions were then reconstituted by standard PhiC31/attB transgenesis using the RIVwhite_3xHA::brk and RIVwhite_Shn::3xHA plasmids. The RIVwhite plasmid (47) including 3xHA::brk contains the deleted brk exon and the sequence encoding three copies of the HA tag inserted directly downstream of the start codon. The RIVwhite_Shn::3xHA plasmid contains the full-length coding cDNA with the deleted part of the 3'UTR and the sequence encoding three copies of the HA tag prior to the stop codon. Transformants were identified by the presence of the w + marker, which was then excised using Cre recombinase.

To mutate the BMP-SE of the brp locus, we used the scarless gene editing procedure described in https://flycrispr.org/scarless-gene-editing/. Briefly, overlapping extension PCR was used to insert the two homology arms (5': chr2R: 9 512 865–9 513 874; 3': chr2R: 9 513 972–9 515 364) that carry either a mutated or a wild-type BMP-SE motif and the 3xP3::eGFP pBac transposon cassette into the pJet 1.2 (ThermoFisher) donor vector. The 2 guide RNA sites surrounding the BMP-SE motif (sequence reported in Supplementary Table S1) were identified using the CRISPR Optimal Target Finder (48) and subsequently cloned into the sgRNA (pU6-BbsI-chiRNA) vector (Addgene). To avoid multiple CRISPR-mediated excision events, both PAM sequences were mutated. To account for possible off-target effects of CRISPR, a donor construct with a wild-type BMP-SE and mutated PAM sequences was used as control. Mutant and wild-type donor vectors were injected into nos-Cas9 fly embryos, along with the two corresponding sgRNA vectors (Rainbow Transgenics Flies Inc., CA, USA). EGFP screening in progeny of injected flies was performed using a Leica MZ10 F Stereo Microscope. Removal of the 3xP3::eGFP transposon cassette in transformants was carried out using piggyBac transposase. After confirmation by sequencing, this procedure yielded two independent lines for the mutant BMP-SE and one line for the wild-type BMP-SE.

To perform genomic engineering of the Ly6 gene cluster, we followed the procedure described in (49–51). In summary, the PCR amplified 5' (chr2L: 8,318,763–8,323,873) and 3' (chr2L: 8,338,698–8,342,585) homologous regions flanking the Ly6 genes cluster were cloned into the targeting pGX-attP-WN vector using the restriction sites NotI/Acc65I and BglII/XhoI, respectively. Following P-element mediated transgenesis (Genetics Services Inc., MA, USA), the targeting DNA was excised and linearized using Flippase and I-SceI. Targeted ‘knock out’ events were selected using the dual selection marker W::Neo ([G418] in food = 0.17 mg/ml). A total of 400 000 progeny were screened, yielding 110 potential candidates of which two were found to be correctly targeted events, as confirmed by sequencing. The W::Neo marker was then excised using Cre recombinase resulting in the final Ly6Del mutant allele, in which 14,825 bp of the Ly6 genes cluster is replaced with an attP and loxP site. To restore wild-type and mutated genomic fragments, we integrated sequences of the Ly6 genes cluster into the attP site of Ly6Del; the genomic fragment was PCR-amplified and inserted into the pGE-attBGMR vector using the NotI/Acc65I restriction sites. Mutagenesis of the four BMP-AE motifs was carried out by SOE-PCR using primers designed to introduce the specific mutations. Partial deletions of the Ly6 gene cluster were performed using the restriction site NotI/SpeI and AscI/Acc65I. Mutagenesis was carried out by SOE-PCR using primers designed to introduce the specific mutations. All constructs were verified by sequencing. These constructs were inserted via PhiC31 integrase-mediated site-specific integration into Ly6Del (Rainbow Transgenics Flies Inc. CA, USA). The w + marker from the obtained transformants was excised using Cre, resulting in flies that harbor a wild-type or mutated Ly6 genes cluster flanked by an attR and a loxP site.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were carried out as in (10). The sequence of the probes are indicated in Supplementary Table S1.

Dissection, immunofluorescence and microscopy

Standard procedures were used for immunostaining Drosophila wandering third instar VNCs and NMJ4s. To immunostain GluRIIA at NMJ4, Bouin’s solution was used as fixative for 5 min at room temperature. For NMJ dissections, variation in developmental stage between experimental groups was minimized by transferring first instar larvae to fresh vials at a density of 80 larvae/vial until the desired stage. The synapse located at muscle 4 within abdominal segment 2–5 was selected for analysis. Primary antibodies were mouse anti-Brp (1:20; nc82), mouse anti-GluRIIA (1:50; 8B4D2) and mouse anti-Dlg (1:50 4F3) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, USA); chicken anti-βgal (1:1000; ab9361); rabbit anti-pSmad1/5 (1:100; 41D10; Cell signaling Technology), rat anti-HA (1:100; 3F10; Roche). Secondary antibodies were donkey anti-Mouse, anti-Chicken, anti-Rabbit conjugated to FITC, DyLight 488, Cy3, Cy5 and Alexa 647 (1:500–1:1000; Jackson ImmunoResearch). Images of experimental groups were captured with the same settings with an Olympus FV1000 and Zeiss 880 confocal microscopes.

Quantification of immunofluorescence for reporter expression in the VNC and molecular markers at NMJ4

Bitplane:Imaris v9.2.1 software was used to quantitate reporter activity in nuclei of the VNC and fluorescence intensity of molecular markers at NMJ4. Nuclear reporter activity quantification was carried out as described previously (10). For intensity measurements at NMJ4 (Brp: abdominal segments 2–5, GluRIIA/Dlg: 2–3), the total region of synaptic boutons (HRP staining) was defined using the ‘Surfaces’ tool to select the appropriate NMJ. For each experimental group, an intensity threshold was then selected to ensure the created surface encompasses the entirety of the molecular marker and HRP-stained region. The ‘Cut’ function was used to remove irrelevant structures. To quantify Brp punctae, the surface was then converted to a binary mask, and the ‘Spots’ mode function was used to select the punctae. An estimated XY diameter was calculated by measuring the diameter of select punctae with the ‘Line’ measurement function. For each experimental group, an appropriate threshold was selected to ensure the maximum number of punctae were captured while minimizing false positives. Accuracy of the ‘Spots’ function was validated by manually calculating the volume of selected punctae by measuring its length and radius using the ‘Line’ function and approximating its volume as a bicone. Finally, calculated spots were filtered for those which are only found within the region defined by the HRP-stained binary mask surface. The total volume and intensity of Brp punctae, and also HRP staining, were automatically calculated and extracted. For the quantification of GluRIIA and Dlg immunofluorescence at NMJ4, a similar procedure to that for Brp was used, except that the total intensity of these molecular markers was calculated using the ‘Surface’ mode function and no HRP-stained binary mask was used.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the online tools at https://www.statskingdom.com/, http://ccb-compute2.cs.uni-saarland.de/wtest/ (52) and https://astatsa.com/KruskalWallisTest/. To determine whether sample populations were normally distributed, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used. All comparisons were performed using the Student’s t-test, one-way ANOVA or the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum and Kruskal–Wallis rank sum tests. For RNA-seq, the Wald test was used and the P-value was adjusted with the Benjamini–Hochberg FDR method. Differences between genotypes were considered significant when P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) and graphing was carried out using MS Excel.

RESULTS

Identification of a neuronal BMP gene regulatory network

To identify target genes that mediate the downstream function of BMP-dependent transcription in motor neurons, we examined differentially expressed genes in wit null wandering third instar larvae (10) (Figure 1B). Among the 9868 genes expressed in the VNC, 1201 genes (12.2%) were significantly differentially expressed (DE); 637 (6.5%) were downregulated, and 564 (5.7%) genes were upregulated (Figure 1C and Supplementary Table S2). To reveal whether DE genes were enriched within functionally related gene networks, GO term over-representation analysis using the functional annotation tools, PANTHER (29,30) and DAVID (31,32), was applied to DE genes. Of the 564 genes upregulated in wit nulls (BMP-downregulated), no biological processes were over-represented. In contrast, of the 637 genes downregulated in wit nulls (BMP-upregulated), PANTHER identified 16 over-represented biological processes, of which six were related to neurotransmission, with the others also pertinent to the reported wit NMJ phenotype, including ‘cell-cell adhesion via plasma membrane adhesion molecules’ and ‘synapse organization’ (Figure 1D). Genes over-represented by Cellular Component were mostly localized to the synapse, and those over-represented by Molecular Function were mostly related to amino acid transport and ion transport, as well as neuropeptide/neurohormone signaling. Similar findings were obtained using DAVID (Supplementary Figure S1A). Thus, because BMP activity is mostly restricted to motor neurons in the VNC, these data indicate that retrograde BMP signaling upregulates a large number of genes that coordinately regulate synaptic growth and neurotransmission in motor neurons (5–7).

Persistent retrograde BMP signaling and downstream transcription is required to maintain neurotransmission and allow for plasticity throughout larval growth, but the downstream target genes are largely unknown (7,12). Using our data to identify candidate genes, we focused on the network of neurotransmission genes (NT) that is over-represented for BMP-activated genes. The six over-represented GO term categories that relate to neurotransmission comprise a total of 453 genes, of which 110 are BMP-responsive (24.3% of genes in the network), including 86 BMP-upregulated (19%) and 24 BMP-downregulated (5.3%) genes (Figure 1D and E; Supplementary Figure S2). Within this NT network, we found four major interaction clusters (I–IV) that contain 38 BMP-upregulated genes encoding key regulators of neurotransmission, neurotransmitter transporters (VGlut, Eaat1), ion channels (nAChRα1, mGluR, 5-HT1A, eag), modulators of ion channels (Grip, Slob), active zone organization and synaptic vesicle fusion (Brp, Syx1A, Syt1, nSyb, Comt, Snap24, Cpx, Tomosyn) and vesicle recycling (rab3, StnB) (Figure 1E and Supplementary Figure S2). We further subdivided the 110 wit-responsive genes within this broad neurotransmission category into five groups of related gene function: (i) NT synthesis and transport, (ii) cell adhesion and cytoskeleton, (iii) signaling, (iv) transcription and RNA, and (v) metabolism and others (Figure 1E and F). We found that the majority of the wit-responsive gene groups were BMP-upregulated, except for the ‘metabolism and others’ group, which shows a 1:1 ratio (Figure 1F). Thus, BMP signaling transcriptionally upregulates a gene network encoding functionally interacting components of NMJ neurotransmission.

To lift these findings over to mammalian phenotypes and human disease, we first identified the highest scoring human orthologs (1086 genes) of the 637 BMP-upregulated genes, using DIOPT (35). Using EnrichR (40–42) with mammalian phenotypes in MGI, we observed significant enrichments for neuronal and synaptic phenotypes, particularly related to neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity (Supplementary Figure S1B). Second, we examined disease associations for the 1086 human orthologs. Using DisGeNET (37–39) with stringent settings, we found that 85 human orthologs were associated with 14 diseases including intellectual disability, spastic paraplegia, Parkinson disease and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (Figure 1G and Supplementary Table S3). Altogether, we conclude that retrograde BMP signaling upregulates neurological disease-relevant genes to promote synaptic function.

BMP-AE and BMP-SE motifs mediate BMP-dependent upregulation of neuronal gene expression

Having identified a BMP-regulated synaptic gene network, we then assessed the proportion of these genes that are directly regulated by BMP signaling in motor neurons. Because the CNS displays great cell-subtype diversity with a relatively low number of motor neurons that makes genomics methods to identify pMad bound regions challenging, we opted for a computational approach to test for enrichment of BMP-AE (GGCGCCAN4GNCV) and BMP-SE (GRCGNCN5GTCTG) motifs, for which the GGCGCC/GRCGNC sequences are bound by pMad and the GNCV/GTCT sequences are bound by Med (21,53). Previously, we found that the BLS to motif confidence method (54) efficiently identified functional BMP-AE motifs that upregulate expression of nearby genes in motor neurons (10). BMP-SE motifs are established BMP-dependent silencers of gene expression during embryogenesis, growth and patterning of larval imaginal discs, yet their function remained unexamined in neurons.

To determine if the BLS method can predict functional BMP-SEs, we filtered the 261 strict BMP-SE motifs found in the noncoding Drosophila genome using BLS (Supplementary Figure S3) and identified 154 conserved BMP-SEs based on the strict consensus sequence (GRCGNCN5GTCTG). These were used to calculate enrichment near BMP-regulated genes found in transcriptomic datasets reporting differential gene expression upon ubiquitous BMP-activation in the embryonic blastoderm (28). Confirming expectations, BMP-SE motifs were significantly enriched near BMP-downregulated genes, and BMP-AE motifs near BMP-upregulated genes. A control set of Bicoid (Bcd)-responsive genomic fragments showed no enrichment (Figure 2A). This confirmed that the BLS approach accurately predicts functional instances of these two motifs genome-wide.

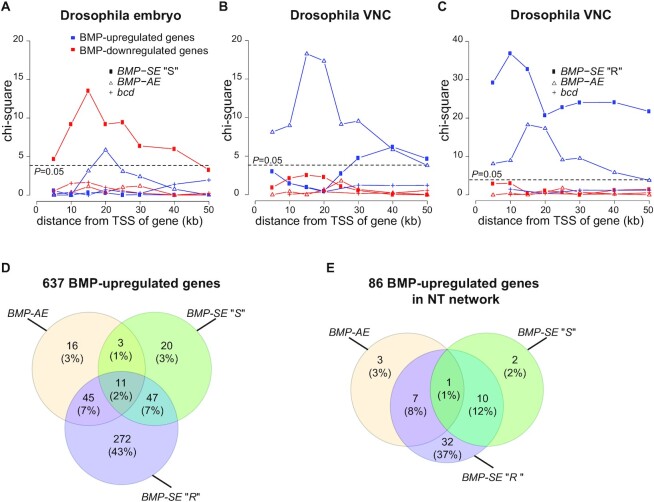

Figure 2.

(A–C) Chi-square calculation of enrichment of BMP-AEs and bcd-responsive genomic fragments as well as strict (A,B) and relaxed (C) BMP-SE motifs (strict BMP-SE denoted ‘S’, relaxed BMP-SE denoted ‘R’) to BMP-responsive genes in (A) published RNA-seq datasets from the embryonic blastoderm and (B,C) larval VNCs. All motifs that exceed the threshold P-value of 0.05 are considered significantly enriched. The x-axis indicates incremental distance (in kb) of the motifs from the transcriptional start site (TSS) of expressed genes. Strict BMP-SE motifs are excluded to calculate enrichment of relaxed BMP-SE motifs. (D–E) Venn diagrams showing the number of all neuronal BMP-upregulated genes (D) and specifically those in the neurotransmission (NT) network (E) that contain a BMP-AE and/or BMP-SE motifs within 50 kb of their TSS.

We performed the same analysis using our wit null VNC RNA-seq datasets (10). Extending our previous findings, we found that conserved BMP-AEs were significantly enriched to BMP-upregulated genes but not to BMP-downregulated genes (Figure 2B). However, unexpectedly, BMP-SEs were also significantly enriched near BMP-upregulated genes and not to BMP-downregulated genes (Figure 2B). A parsimonious explanation for this observation would hold that the BMP-SE may operate as an atypical activator motif in motor neurons, in contrast to its strict repressive function in other tissues.

Recruitment of the pMad/Med complex and Shn to the BMP-SE requires the strict consensus sequence of Med-recruiting nucleotides at positions 12, 14 and 15 for repressor activity (21). In contrast, positions 13 and 16 of the BMP-SE motif display less strict consensus sequence requirements (55). Therefore, we tested whether a relaxed BMP-SE motif (GRCGNCN5GTCTG to GNCGNCN5GNCT) would increase enrichment near BMP-upregulated genes. Confirming this prediction, we found that relaxing the BMP-SE motif increased the enrichment of BMP-SE at BMP-upregulated genes, but not at BMP-downregulated genes, supporting the hypothesis that BMP-SE motifs mediate BMP-upregulation of numerous neuronal target genes (Figure 2C).

These data provide evidence that both BMP-REs mediate direct BMP-dependent upregulation of neuronal gene expression. Indeed, 22% (142/637) of the BMP-upregulated genes harbor a conserved BMP-AE and/or strict BMP-SE within 50 kb of their transcription start site (TSS) (Figure 2D). Moreover, when considering the more relaxed BMP-SE motif, we found that 65% (414/637) of the BMP-upregulated genes harbor a conserved BMP-RE within 50 kb of their TSS (Figure 2D). A similar 64% (55/86) was observed when only the BMP-upregulated genes of the NT network were considered, indicating that neurotransmission at the NMJ is controlled by a large number of genes that are likely directly upregulated by BMP-signaling (Figure 2E and Supplementary Table S4).

BMP-SE upregulates reporter gene expression in motor neurons

To obtain functional evidence that BMP-SE motifs operate as transcriptional activators in motor neurons, we selected 34 conserved BMP-SEs for in vivo testing, based on their close proximity to wit-responsive genes. Genomic fragments containing those 34 BMP-SEs were cloned into nuclear lacZ reporter constructs to test their reporter activity in larval VNCs. We found that 24 (70.6%) of these DNA fragments drove reporter expression in the VNC, and that 16 (47.1%) were active in pMad positive neurons (Figure 3A and Supplementary Table S1). To assess whether these 34 genomic fragments are BMP-regulated, we tested reporter expression in wit nulls. We found that 11 of the 16 reporters active in pMad positive neurons (69%) displayed a loss of expression in wit mutants, and that only 1 out of the 34 reporters (2.9%) exhibited upregulation (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure S4A and Table S5). This further supported our hypothesis that the BMP-SE motif primarily mediates BMP-dependent activation in the VNC. We next tested whether the activity of these genomic fragments is controlled by the embedded BMP-SE motif. To this end, we selected three BMP-SEs, based on strong wit-responsiveness of their corresponding genomic fragments and examined the recruitment of pMad/Med complexes at those motifs by EMSA. Lysates of Schneider 2 cells (S2) transfected with Mad, Med and a constitutively activated Tkv (TkvQD) were tested for their capacity to band shift IRDye700 tagged probes containing those BMP-SEs (Figure 3C and D). We found that the pMad/Med complex shifted each labeled probe, indicating its binding to the BMP-SE motifs. These interactions were sequence specific, since all band shifts were not observed when labeled mutated probes (ΔMad), carrying substitution mutations at the pMad binding, were tested (Figure 3D). Interestingly, we also observed two band shifts, with both the labeled wild-type and mutant probes with lysates of non-transfected and transfected S2 cells. This suggests that additional unknown proteins, found in S2 cells, bind and shift these probes independently of BMP-signaling and the sequence of the BMP-SE motif. Thus, we interpret these band shifts as non-specific because they do not represent pMad/Med complex binding at the BMP-SE motif. We also observed that a number of these non-specific bands were eliminated upon pMad/Med complex probes binding, which we presume is due to higher affinity of the pMad/Med complex for the wild-type probe than the unknown proteins. These observations were also confirmed in EMSA using unlabeled wild-type and ΔMad-mutated probe competitors (Supplementary Figure S4B).

To obtain in vivo evidence that the BMP-SE motifs mediate BMP-activation, we mutated the BMP-SEs within 5 wit-responsive genomic fragments. These BMP-SEs were selected because of their significant wit-dependent loss of reporter expression (Van61, Van65, Van75, Van80) or gain of reporter expression (Van74). We found that three out of these four BMP-activated genomic fragments displayed a loss of reporter expression due to BMP-SE mutation (Figure 3E and Supplementary Figure S4C). In contrast, mutation of the BMP-SE within Van74 did not lead to any change, suggesting that the increase of expression for this reporter in wit nulls is not mediated by this motif (Supplementary Figure S4C). Altogether, these data provide functional in vivo evidence that the BMP-SE mediates BMP-dependent gene upregulation in motor neurons.

The BMP-SE displays tissue-specific dichotomous function

Our finding that BMP-SE motifs operate akin to the function of BMP-AE motifs in the VNC led us to test whether BMP-SE and BMP-AE sequences are functionally interchangeable in motor neurons. To this end, we converted the BMP-SE of the Van75 reporter into a BMP-AE (Van75SE>AE), by replacing the thymine at position 15 with a guanine (Figure 3C). Second, we converted the BMP-AE of the Van26 reporter into a BMP-SE (Van26AE>SE), by replacing the guanine at position 15 with a thymine (Figure 3C). The BMP-AE within the Van26 reporter was previously shown to be essential for its neuronal activity (10). These modifications did not change reporter activity of either genomic fragment (Figure 3F), suggesting that BMP-SE and BMP-AE motifs are interchangeable gene activators in neurons. However, it is also possible that DNA motifs embedded in sequences adjacent to the BMP-SE are responsible for its unique gene activation output in motor neurons. To rule this possibility out, we performed a BMP-AE to BMP-SE conversion in the wit-responsive Van36 fragment (Figure 4A). This fragment displays BMP-responsiveness in both the wing imaginal disc and in neurons of the VNC (Figure 4B and C) (10,53). In line with our prediction, the Van36AE>SE reporter showed a total loss of expression in the wing disc but maintained wild-type reporter expression in motor neurons (Figure 4B and C). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that the activator function of the BMP-SE in motor neurons is independent of additional regulatory motifs in the genomic fragment.

Interestingly, we noted that the Van36 reporter is also expressed in many glial cells of the VNC, and that this pattern was lost when the BMP-AE was mutated into a BMP-SE (Figure 4C). Since a role for BMP signaling in gene regulation in glia of the VNC is unknown at this time, it remains unclear whether this observation is artifactual, or due to a BMP-dependent silencing function of the BMP-SE in glia.

Absence of the Shn de-repression path for BMP-SE mediated activation in motor neurons

Next, we tested for any contribution of Shn to BMP-SE function in motor neurons. By both RNA-seq and examination of the expression of a functional C-terminal, HA-tagged allele of shn (shn::HA), we found that shn is indeed expressed in the VNC. By RNA-seq, we did observe a modest but significant downregulation of shn in wit nulls (Supplementary Figure S5A). However, upon analysis of Shn::HA expression, we found it to be selectively absent from most pMad-positive neurons (91.7% ± 0.9; n = 4 VNCs) (Figure 5A) but robustly expressed in other cells. This raises the possibility that the absence of Shn in most motor neurons may account for the specific BMP-SE activator function in these cells. To test this hypothesis, we misexpressed a subfragment of Shn (ShnCT) in motor neurons, which recapitulates Shn repressive activity (21). In this context, we compared reporter activity of the wild-type Van75 reporter, which contains a wild-type BMP-SE, with a converted Van75 reporter in which the BMP-SE was converted to a BMP-AE (Van75SE>AE). We reasoned that if the BMP-SE activator function depends on the absence of Shn in motor neurons, then the wild-type Van75 reporter would be repressed, whereas the Van75SE>AE reporter would not be affected, based on the requirement of Shn activity upon the strict BMP-SE consensus sequence. In confirmation of our hypothesis, we observed a 70% loss of reporter activity of wildtype Van75 compared to a 20% loss of the converted Van75SE>AE reporter (Figure 5B and C). The incomplete loss of reporter activity following ShnCT misexpression likely reflects both the lack of BMP responsiveness of the reporter in a subset of VNC cells (see Figure 3B and E) and the low GAL4 expression in certain motor neurons. Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that an additional unknown cofactor that assists in Shn recruitment to the activated Smad complex at the BMP-SE is absent in some motor neurons. These data suggest that the absence of Shn in most motor neurons is a prerequisite for the activator function of the BMP-SE embedded in the Van75 reporter.

We then focused on brk, a repressor of BMP-activated target genes in many tissues that is repressed by BMP signaling and Shn (Figure 1A). In the VNC, we observed a lack of differential expression for brk in wit nulls (Figure 5D). This lack of BMP-dependent expression was confirmed by examining expression of a functional endogenously HA-tagged brk allele that faithfully recapitulates its expression in the wing disc (Supplementary Figure S5B and C). Next, we explored the possibility that low levels of Brk in motor neurons, not detectable by immunohistochemistry, may still be sufficient to repress potential BMP-AEs to control for optimal expression of BMP-upregulated genes. To this end, we analyzed expression of Van26BMP-AE, a sensitive BMP-dependent reporter expressed in many motor neurons, in brkXAstrong hypomorphs. We found no change in the activity of Van26BMP-AE in motor neurons (Figure 5E and F), suggesting that brk does not repress BMP-AEs.

We conclude that downstream BMP signaling transcriptional outcomes in motor neurons do not operate in the context of the de-repression path involving brk and shn function, in contrast to most other Drosophila tissues analyzed to date (Figure 5G).

BMP-REs mediate BMP-upregulation of critical synaptic genes

We then wished to dissect the contribution of BMP signaling and both BMP-RE motif types to the regulation of synaptic genes controlling BMP-dependent synaptic functions. To this end, we focused our attention on three BMP-upregulated genes: brp, cg7781 and cg14274. Brp encodes a presynaptic active zone scaffolding protein regulating synaptic neurotransmission and plasticity (56,57). The brp locus contains a single conserved BMP-SE motif that is wit-responsive in reporter assays (Figures 6A and 3E, Van65). Cg7781 and cg14274 encode predicted glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored (GPI) proteins with unknown function, which are related to the Ly6 genes qvr andtwit, both controlling neurotransmission in Drosophila (14,58,59). Cg7781 and cg14274 are organized in a gene cluster (Figure 6E) that contains four conserved BMP-AEs mediating BMP-signaling in reporter assays (10).

Using a CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing approach, we generated two alleles at the brp BMP-SE motif; a mutant allele in which the BMP-SE was edited to prevent pMad/Med binding, and a control allele that did not modify the BMP-SE but controlled for the PAM site mutations (Supplementary Figure S6). We analyzed the consequence on Brp expression at the larval NMJ by anti-Brp immunolabeling. Mutation of the BMP-SE motif resulted in a strong loss of Brp immunoreactivity at NMJ boutons (Figure 6B–D), supporting a role for the BMP-SE in mediating BMP-upregulation of this gene.

To examine the function of Ly6 genes and their BMP-dependent upregulation by the BMP-AE motif, we used homologous recombination to delete a ∼15 kb region including the four BMP-AEs and the first coding exons of cg7781 and cg14274. We replaced this region with an attP and a loxP site (Ly6Del) to target wild-type or modified sequences of the Ly6 genes cluster at its endogenous locus (Figure 6E). This deletion also includes the wit-unresponsive Ly6 gene cg14275 (Figure 6E and data not shown). Ly6Del mutants were viable and fertile, allowing us to examine phenotypes at the larval NMJ. Examining wandering third instar NMJ4, we observed a dramatic reduction of postsynaptic glutamate receptor subunit IIA (GluRIIA) in Ly6Del mutants (Figure 6F and G). The loss of GluRIIA was specific, since the levels of the postsynaptic marker, Discs Large (Dlg), and the active zone scaffolding protein, Bruchpilot (Brp), remained unaffected (Supplementary Figure S7A and B). To identify which of the Ly6 genes contribute to this phenotype, we examined GluRIIA in Ly6Del mutant NMJs rescued with two non-overlapping wild-type genomic fragments that encompass either cg7781 (R-cg7781) or cg14274 (R-cg14274) (Figure 6E). We found that cg14274, but not cg7781, is required for GluRIIA at NMJ4 (Supplementary Figure S7C). To then test if presynaptic expression of cg14274 regulates postsynaptic GluRIIA at the NMJ, we expressed a dsRNA against cg14274 under the control of the elav-Gal4 pan-neuronal driver. We observed a strong reduction of GluRIIA (Figure 6H and I) at NMJ4, indicating that neuronal cg14274 expression controls the accumulation of GluRIIA at the post-synapse in muscle. By virtue of its function at the synapse, we named the cg14274 gene without maturity (witty). Finally, to test if the BMP-AE motifs near the witty locus mediate BMP-dependent upregulation of witty in motor neurons to control postsynaptic GluRIIA, we mutated the four BMP-AEs in the Ly6 genes cluster (Figure 6E). Strikingly, this phenocopied the loss of GluRIIA observed in Ly6Del mutant NMJ4 (Figure 6F and G). Therefore, the BMP-AEs mediate the BMP-dependent upregulation of witty transcription in motor neurons to control GluRIIA accumulation in the muscle at the NMJ.

Taken together, these data demonstrate that both motifs, the BMP-AE and the BMP-SE, mediate widespread direct BMP-dependent upregulation of genes critical for synaptic maturation (Figure 7).

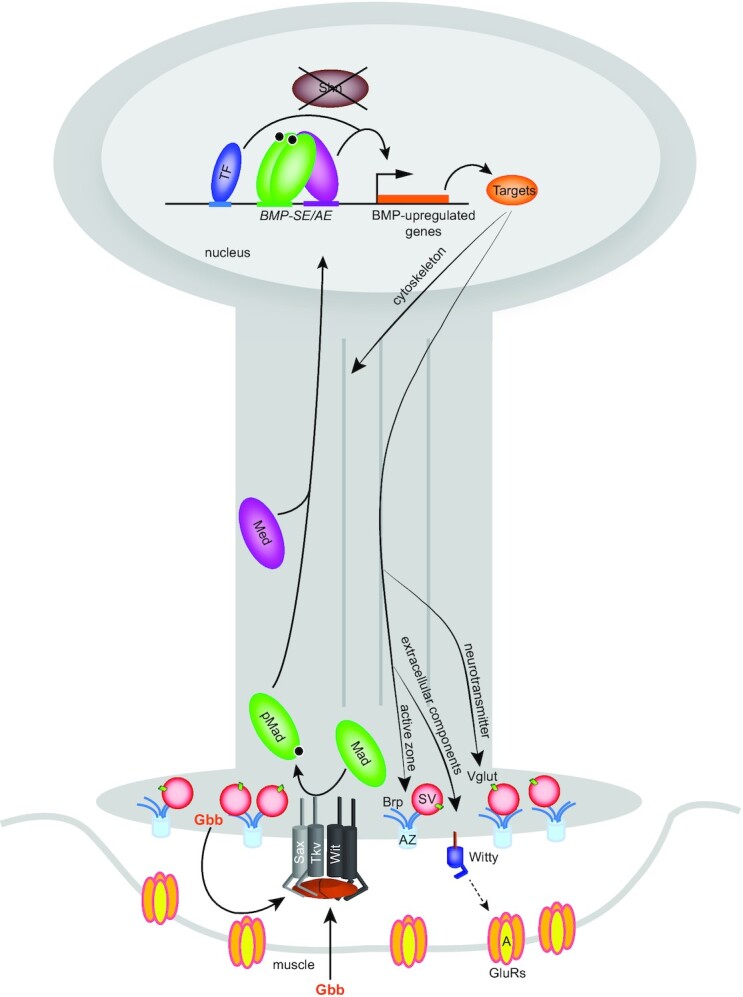

Figure 7.

In this model, the BMP ligand Gbb is secreted by muscle cells and motor neurons to bind a tetrameric complex of Sax-Tkv/Wit, the type I and type II BMP receptor kinases. Upon receptor activation, cytoplasmic Mad is phosphorylated by Tkv-Sax and binds the co-Smad Med to accumulate in the motor neuron nucleus. In the absence of the corepressor Shn, the activated pMad/Med complex binds BMP-AE and BMP-SE to activate, with additional input from other transcription factors, a battery of target genes to regulate neuronal function such as neurotransmitter transport, active zone scaffolding, cytoskeleton organization and postsynaptic GluRIIA clustering.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified a network of wit-responsive genes in Drosophila motor neurons, with an overrepresentation of upregulated genes involved in neurotransmission. We also found adjacent candidate cis-regulatory BMP-REs for many of these genes. This suggests that BMP signaling primarily operates directly to upregulate a network of presynaptic genes to promote motor neuron maturation. Notably, we discovered that BMP-SE motifs operate as activators in motor neurons, and that the Shn/Brk de-repression pathway is absent, revealing a unique regulatory mechanism for BMP gene regulation in these cells. Next, by BMP-RE mutagenesis we demonstrated the role of direct BMP-dependent regulation of brp and the novel gene witty, thereby providing mechanistic insight into the contribution of retrograde BMP signaling to synaptic maturation. Considering that neurotransmission requires continuous BMP-dependent regulation and NMJ growth appears to be only BMP-dependent during early developmental time points (12), it will be interesting to monitor BMP-dependent gene expression through embryonic and larval stages after modulating BMP signaling components and activity levels in motor neurons. Furthermore, the direct BMP-dependent regulation of a large fraction of the gene network we have identified raises the possibility that BMP signaling may be involved in scalable, fast transcriptional responses to perturbations at the growing NMJ. While such mechanisms remain undemonstrated, we believe that future efforts to monitor the dynamics of BMP-regulated target gene transcription will be facilitated by our identification of direct BMP target genes and their BMP-responsive cis-regulatory elements.

Our findings suggest that the gene network identified here orchestrates neurotransmission and maturation at the Drosophila NMJ. We speculate that orthologs of many of these genes operate within related networks to control similar functions in vertebrate synapses. To expand on this, we examined if any of the neuronal genes upregulated by BMP signaling are disease relevant. Through highly stringent orthology and disease association searches, we found that 77 BMP-upregulated genes have a human gene ortholog strongly implicated in a neurological disorder. Interestingly, among those 77 genes, the ortholog of fly Reticulon-like 1 (Reticulon 2; RTN2) is implicated in Hereditary Spastic Paraplegias (HSPs) (60). Moreover, deregulation of TGFβ/BMP signaling has also been implicated in HSPs (61–63); thus, our work suggests a relevant link between RTN2 and the TGFβ/BMP signaling pathway in HSP.

A notable finding in our study is that the BMP-SE operates as an activator in motor neurons. Thus, this motif does not operate as a strict silencer in Drosophila, but as a context-dependent dichotomous cis-regulatory element, depending on the tissue and the presence of Shn. Studies aimed at identifying BMP-responsive cis-regulatory elements in vertebrates have revealed that both BMP-AE and BMP-SE-type motif sequences are present. Interestingly, BMP-SE-type motifs seem to operate as strict activators in vertebrates (64,65), with Shn orthologs having a co-activator function (65,66). This observation and our findings that the BMP-SE motif operates as an activator in Drosophila motor neurons can be reconciled from an evolutionary perspective, given evidence that the CNS of both vertebrates and invertebrates share a monophyletic origin and is patterned by BMP signaling (67,68). Although the role of the BMP signaling pathway in patterning the trunk CNS along the dorso-ventral axis of animals is conserved, BMP-dependent target gene regulation is often reversed. For example, in the dorsal neuroectoderm, expression of Drosophila msx and zebrafish msxB genes are both BMP-regulated; through a BMP-SE motif that mediates silencing in Drosophila and a relaxed BMP-SE motif that mediates activation in zebrafish (69). Therefore, we speculate that while BMP-AE and BMP-SE motifs are activators by default, the latter motif was subsequently recruited to the repression of brk and other genes in numerous tissues in Drosophila (20,21,23–26). In contrast, in tissues where BMP-dependent regulation of brk is absent, such as in Drosophila motor neurons, or in vertebrates where no brk gene is present, the BMP-SE retained its ancestral activator role.

By validating the function of BMP-REs that upregulate brp and witty, we not only demonstrate that our approach is efficient at identifying direct target genes involved in BMP-dependent synaptic functions but also provide a framework for the experimental dissection of the discrete contribution of BMP signaling to the expression and function of those genes at the NMJ. Previous work reported that Brp-positive active zones number and density was strongly reduced at the NMJ in gbb, wit and antimorphic Mad1 mutants (12,70). Moreover, inhibition of BMP-dependent transcription in third instar larvae led to rapid loss of active zone density, which correlates with the observed loss of competence for presynaptic homeostatic plasticity after BMP blockade (7,12). We now provide mechanistic evidence for these observations by showing that brp is directly BMP-upregulated. This may explain how persistent retrograde BMP signaling and transcriptional activity are required to maintain active zone integrity (7,12).

Our findings demonstrate that canonical BMP-dependent upregulation of witty is required for postsynaptic GluRIIA accumulation at the NMJ but does not rule out additional postsynaptic functions for witty. While these data are consistent with the observation that postsynaptic GluRIIA is severely reduced in wit and mad1 mutants (71–73), they do contrast with recent reports that a non-canonical BMP signaling pathway dependent on synaptic pMad also regulates GluRIIA at the NMJ (71). Therefore, these canonical and non-canonical pathways may indeed function as non-redundant BMP-dependent mechanisms. To expand on such a model, we suggest that synaptic pMad may allow for acute, short-term compensatory responses, whereas the pMad-dependent transcriptional mechanism may offer a longer-term consolidation response. Future experiments aimed at defining the underlying mechanisms regulated by witty will be critical to understanding how presynaptic retrograde BMP signaling controls postsynaptic maturation.

In conclusion, the identification of BMP-activated genes and their BMP-REs facilitates the discovery of novel synaptic genes, as well as the dissection of how BMP-dependent transcriptional regulation of target genes contributes to NMJ function. We anticipate that our approach will facilitate the disentanglement of transcriptional versus synaptic roles for BMP signaling at the NMJ.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Raw numerical data used to generate graphs can be found in Supplementary Table S5.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are very grateful to Dr Anaïs Bardet and Dr Alexander Stark for performing the motif confidence analysis for the BMP-SE and also to Stephanie Huynh for helping to generate the Ly6Del mutant at the initial stage of the project. We thank members of the Allan laboratory and Tim O’Connor for insightful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Yang Hong, Markus Affolter, Allen Laughon and the Bloomington and VDRC Drosophila Stock Centers, the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center P[acman] Resources for fly stocks and molecular reagents.

Author contributions: R.V. and D.W.A. conceived and designed the experiments. R.V. performed most of the experiments. M.M. generated the wildtype and mutant CRISPR alleles of the BMP-SE in the brp locus, performed the immunostaining of Brp at NMJ4 with assistance from R.V. and quantified the data. T.L. performed the EMSA experiments. G.P. and C.-M.E. generated the Shn::HA and Brk::HA alleles. S.F. and R.V. performed the bioinformatics analysis. S.M.-G. quantified the expression of the molecular markers at Ly6 genes cluster mutant NMJ. A.P.H. and G.K. discovered the loss of GluRIIA in the Ly6Del mutant. R.V., A.C. and S.L. generated mutant versions of the reporter constructs. R.V., M.M., T.L., S.F., S.M.-G, A.C., S.L. and D.W.A. analyzed data. R.V. generated the figures. R.V. and D.W.A. wrote the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Robin Vuilleumier, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

Mo Miao, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

Sonia Medina-Giro, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

Clara-Maria Ell, Spemann Graduate School of Biology and Medicine (SGBM), University of Freiburg, Freiburg, 79104, Germany; CIBSS - Centre for Integrative Biological Signaling Studies and Institute for Biology I, Faculty of Biology, Hilde Mangold Haus, Habsburgerstrasse 49, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, 79104, Germany.

Stephane Flibotte, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

Tianshun Lian, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

Grant Kauwe, Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, CA 94945, USA.

Annie Collins, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

Sophia Ly, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

George Pyrowolakis, CIBSS - Centre for Integrative Biological Signaling Studies and Institute for Biology I, Faculty of Biology, Hilde Mangold Haus, Habsburgerstrasse 49, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, 79104, Germany.

A Pejmun Haghighi, Buck Institute for Research on Aging, Novato, CA 94945, USA.

Douglas W Allan, Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, V6T 1Z3, Canada.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) [F16-01394, F20-04798 to D.W.A.]; Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [EXC-2189, Project ID: 390939984 to G.P.]; National Institutes of Health (NIH) [R01NS082793 to A.P.H]. Funding for open access charge: CIHR [F20-04798].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sanyal S., Kim S.M., Ramaswami M.. Retrograde regulation in the CNS; neuron-specific interpretations of TGF-beta signaling. Neuron. 2004; 41:845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meyers E.A., Kessler J.A.. TGF-β family signaling in neural and neuronal differentiation, development, and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017; 9:a022244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bayat V., Jaiswal M., Bellen H.J.. The BMP signaling pathway at the drosophila neuromuscular junction and its links to neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2011; 21:182–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kashima R., Hata A.. The role of TGF-β superfamily signaling in neurological disorders. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai). 2018; 50:106–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marqués G., Bao H., Haerry T.E., Shimell M.J., Duchek P., Zhang B., O’Connor M.B. The drosophila BMP type II receptor wishful thinking regulates neuromuscular synapse morphology and function. Neuron. 2002; 33:529–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aberle H., Haghighi A.P., Fetter R.D., McCabe B.D., Magalhães T.R., Goodman C.S.. Wishful thinking encodes a BMP type II receptor that regulates synaptic growth in drosophila. Neuron. 2002; 33:545–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Goold C.P., Davis G.W.. The BMP ligand gbb gates the expression of synaptic homeostasis independent of synaptic growth control. Neuron. 2007; 56:109–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rawson J.M., Lee M., Kennedy E.L., Selleck S.B.. Drosophila neuromuscular synapse assembly and function require the TGF-beta type i receptor saxophone and the transcription factor mad. J. Neurobiol. 2003; 55:134–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Smith R.B., Machamer J.B., Kim N.C., Hays T.S., Marqués G.. Relay of retrograde synaptogenic signals through axonal transport of BMP receptors. J. Cell. Sci. 2012; 125:3752–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vuilleumier R., Lian T., Flibotte S., Khan Z.N., Fuchs A., Pyrowolakis G., Allan D.W.. Retrograde BMP signaling activates neuronal gene expression through widespread deployment of a conserved BMP-responsive cis-regulatory activation element. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:679–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCabe B.D., Hom S., Aberle H., Fetter R.D., Marques G., Haerry T.E., Wan H., O’Connor M.B., Goodman C.S., Haghighi A.P.. Highwire regulates presynaptic BMP signaling essential for synaptic growth. Neuron. 2004; 41:891–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Berke B., Wittnam J., McNeill E., Van Vactor D.L., Keshishian H.. Retrograde BMP signaling at the synapse: a permissive signal for synapse maturation and activity-dependent plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2013; 33:17937–17950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ball R.W., Warren-Paquin M., Tsurudome K., Liao E.H., Elazzouzi F., Cavanagh C., An B.S., Wang T.T., White J.H., Haghighi A.P.. Retrograde BMP signaling controls synaptic growth at the NMJ by regulating trio expression in motor neurons. Neuron. 2010; 66:536–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim N.C., Marqués G.. The Ly6 neurotoxin-like molecule target of wit regulates spontaneous neurotransmitter release at the developing neuromuscular junction in drosophila. Dev. Neurobiol. 2012; 72:1541–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Affolter M., Pyrowolakis G., Weiss A., Basler K.. Signal-induced repression: the exception or the rule in developmental signaling?. Dev. Cell. 2008; 15:11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barolo S., Posakony J.W.. Three habits of highly effective signaling pathways: principles of transcriptional control by developmental cell signaling. Genes Dev. 2002; 16:1167–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campbell G., Tomlinson A.. Transducing the dpp morphogen gradient in the wing of drosophila: regulation of dpp targets by brinker. Cell. 1999; 96:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Minami M., Kinoshita N., Kamoshida Y., Tanimoto H., Tabata T.. Brinker is a target of dpp in drosophila that negatively regulates dpp-dependent genes. Nature. 1999; 398:242–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jaźwińska A., Kirov N., Wieschaus E., Roth S., Rushlow C.. The drosophila gene brinker reveals a novel mechanism of dpp target gene regulation. Cell. 1999; 96:563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Müller B., Hartmann B., Pyrowolakis G., Affolter M., Basler K.. Conversion of an extracellular dpp/BMP morphogen gradient into an inverse transcriptional gradient. Cell. 2003; 113:221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pyrowolakis G., Hartmann B., Müller B., Basler K., Affolter M.. A simple molecular complex mediates widespread BMP-induced repression during drosophila development. Dev. Cell. 2004; 7:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stathopoulos A., Levine M.. Localized repressors delineate the neurogenic ectoderm in the early drosophila embryo. Dev. Biol. 2005; 280:482–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beira J.V., Springhorn A., Gunther S., Hufnagel L., Pyrowolakis G., Vincent J.P.. The dpp/TGFβ-dependent corepressor schnurri protects epithelial cells from JNK-induced apoptosis in drosophila embryos. Dev. Cell. 2014; 31:240–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vuilleumier R., Springhorn A., Patterson L., Koidl S., Hammerschmidt M., Affolter M., Pyrowolakis G.. Control of dpp morphogen signalling by a secreted feedback regulator. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010; 12:611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen D., McKearin D.M.. A discrete transcriptional silencer in the bam gene determines asymmetric division of the drosophila germline stem cell. Development. 2003; 130:1159–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen D., McKearin D.. Dpp signaling silences bam transcription directly to establish asymmetric divisions of germline stem cells. Curr. Biol. 2003; 13:1786–1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen H., Xu Z., Mei C., Yu D., Small S.. A system of repressor gradients spatially organizes the boundaries of bicoid-dependent target genes. Cell. 2012; 149:618–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Deignan L., Pinheiro M.T., Sutcliffe C., Saunders A., Wilcockson S.G., Zeef L.A., Donaldson I.J., Ashe H.L.. Regulation of the BMP signaling-responsive transcriptional network in the drosophila embryo. PLoS Genet. 2016; 12:e1006164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thomas P.D., Kejariwal A., Campbell M.J., Mi H., Diemer K., Guo N., Ladunga I., Ulitsky-Lazareva B., Muruganujan A., Rabkin S.et al.. PANTHER: a browsable database of gene products organized by biological function, using curated protein family and subfamily classification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003; 31:334–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mi H., Muruganujan A., Thomas P.D.. PANTHER in 2013: modeling the evolution of gene function, and other gene attributes, in the context of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:D377–D86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huang da W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A.. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huang da W., Sherman B.T., Lempicki R.A.. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009; 4:44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Doncheva N.T., Morris J.H., Bork P.et al.. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019; 47:D607–D613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shannon P., Markiel A., Ozier O., Baliga N.S., Wang J.T., Ramage D., Amin N., Schwikowski B., Ideker T.. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003; 13:2498–2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hu Y., Flockhart I., Vinayagam A., Bergwitz C., Berger B., Perrimon N., Mohr S.E.. An integrative approach to ortholog prediction for disease-focused and other functional studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011; 12:357–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yates A.D., Achuthan P., Akanni W., Allen J., Allen J., Alvarez-Jarreta J., Amode M.R., Armean I.M., Azov A.G., Bennett R.et al.. Ensembl 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020; 48:D682–D688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bauer-Mehren A., Rautschka M., Sanz F., Furlong L.I.. DisGeNET: a cytoscape plugin to visualize, integrate, search and analyze gene-disease networks. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26:2924–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bauer-Mehren A., Bundschus M., Rautschka M., Mayer M.A., Sanz F., Furlong L.I.. Gene-disease network analysis reveals functional modules in mendelian, complex and environmental diseases. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e20284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Piñero J., Saüch J., Sanz F., Furlong L.I.. The DisGeNET cytoscape app: exploring and visualizing disease genomics data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021; 19:2960–2967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chen E.Y., Tan C.M., Kou Y., Duan Q., Wang Z., Meirelles G.V., Clark N.R., Ma’ayan A.. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013; 14:128–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kuleshov M.V., Jones M.R., Rouillard A.D., Fernandez N.F., Duan Q., Wang Z., Koplev S., Jenkins S.L., Jagodnik K.M., Lachmann A.et al.. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:W90–W97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Xie Z., Bailey A., Kuleshov M.V., Clarke D.J.B., Evangelista J.E., Jenkins S.L., Lachmann A., Wojciechowicz M.L., Kropiwnicki E., Jagodnik K.M.et al.. Gene set knowledge discovery with enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 2021; 1:e90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Markstein M., Markstein P., Markstein V., Levine M.S.. Genome-wide analysis of clustered dorsal binding sites identifies putative target genes in the drosophila embryo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002; 99:763–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Adams M.D., Celniker S.E., Holt R.A., Evans C.A., Gocayne J.D., Amanatides P.G., Scherer S.E., Li P.W., Hoskins R.A., Galle R.F.et al.. The genome sequence of drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2000; 287:2185–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoskins R.A., Carlson J.W., Wan K.H., Park S., Mendez I., Galle S.E., Booth B.W., Pfeiffer B.D., George R.A., Svirskas R.et al.. The release 6 reference sequence of the drosophila melanogaster genome. Genome Res. 2015; 25:445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Port F., Chen H.M., Lee T., Bullock S.L.. Optimized CRISPR/cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014; 111:E2967–E2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Baena-Lopez L.A., Alexandre C., Mitchell A., Pasakarnis L., Vincent J.P.. Accelerated homologous recombination and subsequent genome modification in drosophila. Development. 2013; 140:4818–4825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gratz S.J., Ukken F.P., Rubinstein C.D., Thiede G., Donohue L.K., Cummings A.M., O’Connor-Giles K.M. Highly specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9-catalyzed homology-directed repair in drosophila. Genetics. 2014; 196:961–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Huang J., Zhou W., Watson A.M., Jan Y.N., Hong Y.. Efficient ends-out gene targeting in drosophila. Genetics. 2008; 180:703–707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Huang J., Zhou W., Dong W., Watson A.M., Hong Y.. From the cover: directed, efficient, and versatile modifications of the drosophila genome by genomic engineering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009; 106:8284–8289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhou W., Huang J., Watson A.M., Hong Y.. W::Neo: a novel dual-selection marker for high efficiency gene targeting in drosophila. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e31997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Marx A., Backes C., Meese E., Lenhof H.P., Keller A.. EDISON-WMW: exact dynamic programing solution of the wilcoxon-mann-whitney test. Genom. Proteom. Bioinf. 2016; 14:55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weiss A., Charbonnier E., Ellertsdóttir E., Tsirigos A., Wolf C., Schuh R., Pyrowolakis G., Affolter M.. A conserved activation element in BMP signaling during drosophila development. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010; 17:69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kheradpour P., Stark A., Roy S., Kellis M.. Reliable prediction of regulator targets using 12 drosophila genomes. Genome Res. 2007; 17:1919–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gafner L., Dalessi S., Escher E., Pyrowolakis G., Bergmann S., Basler K.. Manipulating the sensitivity of signal-induced repression: quantification and consequences of altered brinker gradients. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e71224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wagh D.A., Rasse T.M., Asan E., Hofbauer A., Schwenkert I., Dürrbeck H., Buchner S., Dabauvalle M.C., Schmidt M., Qin G.et al.. Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in drosophila. Neuron. 2006; 49:833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kittel R.J., Wichmann C., Rasse T.M., Fouquet W., Schmidt M., Schmid A., Wagh D.A., Pawlu C., Kellner R.R., Willig K.I.et al.. Bruchpilot promotes active zone assembly, Ca2+ channel clustering, and vesicle release. Science. 2006; 312:1051–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wang J.W., Humphreys J.M., Phillips J.P., Hilliker A.J., Wu C.F.. A novel leg-shaking drosophila mutant defective in a voltage-gated K(+)current and hypersensitive to reactive oxygen species. J. Neurosci. 2000; 20:5958–5964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Koh K., Joiner W.J., Wu M.N., Yue Z., Smith C.J., Sehgal A.. Identification of SLEEPLESS, a sleep-promoting factor. Science. 2008; 321:372–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Montenegro G., Rebelo A.P., Connell J., Allison R., Babalini C., D’Aloia M., Montieri P., Schüle R., Ishiura H., Price J.et al.. Mutations in the ER-shaping protein reticulon 2 cause the axon-degenerative disorder hereditary spastic paraplegia type 12. J. Clin. Invest. 2012; 122:538–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Summerville J.B., Faust J.F., Fan E., Pendin D., Daga A., Formella J., Stern M., McNew J.A.. The effects of ER morphology on synaptic structure and function in drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell. Sci. 2016; 129:1635–1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wang X., Shaw W.R., Tsang H.T., Reid E., O’Kane C.J.. Drosophila spichthyin inhibits BMP signaling and regulates synaptic growth and axonal microtubules. Nat. Neurosci. 2007; 10:177–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tsang H.T., Edwards T.L., Wang X., Connell J.W., Davies R.J., Durrington H.J., O’Kane C.J., Luzio J.P., Reid E.. The hereditary spastic paraplegia proteins NIPA1, spastin and spartin are inhibitors of mammalian BMP signalling. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009; 18:3805–3821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Javier A.L., Doan L.T., Luong M., Reyes de Mochel NS, Sun A., Monuki E.S., Cho K.W.. Bmp indicator mice reveal dynamic regulation of transcriptional response. PLoS One. 2012; 7:e42566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Yao L.C., Blitz I.L., Peiffer D.A., Phin S., Wang Y., Ogata S., Cho K.W., Arora K., Warrior R.. Schnurri transcription factors from drosophila and vertebrates can mediate bmp signaling through a phylogenetically conserved mechanism. Development. 2006; 133:4025–4034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]