Abstract

Purpose

Peer support programmes that provide services for various health conditions have been in existence for many years; however, there is little study of their benefits and challenges. Our goal was to explore how existing peer support programmes help patients with a variety of health conditions, the challenges that these programmes meet, and how they are addressed.

Methods

We partnered with 7 peer support programmes operating in healthcare and community settings and conducted 43 semi-structured interviews with key informants. Audiorecordings were transcribed and qualitative analysis was conducted using grounded theory methods.

Results

Peer support programmes offer informational and psychosocial support, reduce social isolation, and connect patients and caregivers to others with similar health issues. These programmes provide a supportive community of persons who have personal experience with the same health condition and who can provide practical information about self-care and guidance in navigating the health system. Peer support is viewed as different from and complementary to professional healthcare services. Existing programmes experience challenges such as matching of peer supporter and peer recipient and maintaining relationship boundaries. They have gained experience in addressing some of these challenges.

Conclusions

Peer support programmes can help persons and caregivers manage health conditions but also face challenges that need to be addressed through organizational processes. Peer support programmes have relevance for improving healthcare systems, especially given the increased focus on becoming more patient-centred. Further study of peer programmes and their relevance to improving individuals’ well-being is warranted.

Keywords: caregiver, health services research, patient-centred research, peer support, qualitative research

Key messages.

Peer support programmes provide a supportive community for patients.

Persons can be helped to better manage their health conditions.

These programmes also face challenges that need to be addressed.

Patient-centred care may be improved by offering peer support.

Background

Peer support programmes help connect a person with a health problem to another person (a peer) who has experiential knowledge of managing a similar health problem. In the community, there are over 500,000 support groups and over 6.25 million people who use self-help groups in the United States.1 Peer support programmes are offered by organizations that focus on specific health conditions such as the Alzheimer’s Association, the National Kidney Foundation, and the American Cancer Society, among others. Over 2,000 mental health facilities offer peer support in the United States.2 Some of these programmes have been operating for many years but few of these programmes, have been studied, apart from Alcoholics Anonymous and National Alliance on Mental Illness.3,4

Studies of peer support interventions that have been developed in the research setting suggest they can be beneficial. Randomized controlled trials of peer support for depression, HIV, and diabetes have been shown to improve goal setting, perceived competence, and decrease risky behaviours.5–10 Studies of peer support for chronic disease self-management have shown positive effects on patient activation, self-efficacy, and self-care behaviours.11,12 Often these interventions do not translate into practice and, aside from mental health, are not accessible in healthcare settings for many health conditions. Multiple factors have been suggested as to why this is the case, including lack of familiarity and trust in the effectiveness of peer support programmes as well as lack of financing and knowledge to scale up programmes.13,14

Peer support programmes are particularly relevant nowadays as health systems seek to improve healthcare delivery. In primary care, patient-centred medical homes are integrating services delivered by lay health workers that provide psychosocial support and address social determinants of health to extend the reach of formal health services.15 Federal programmes are incentivizing primary care clinics to collaborate with community organizations that provide social services and orient their care with patient needs at the centre.16 Given the shift in healthcare priorities, peer support programmes that have been established and operating for many years may be a useful resource to advance patient-centred care.

In this study, we sought to explore the value of peer support programmes existing in the community and healthcare systems for people managing a health issue or health condition by asking the following questions: What does peer support offer people with various health conditions; what are the challenges to providing/using these programmes and how can those challenges be addressed?

Methods

Strategy and rationale

We conducted semi-structured interviews with participants who have varying roles in peer support programmes to explore their perspectives on this type of support for various health conditions. We used a grounded theory as a method of enquiry because we desired an inductive approach consisting of a rigorous analytic process both iterative and recursive that allows themes to emerge from the data. In preparation for interview, we developed a semi-structured interview guide that included questions regarding the general benefits of participation in a peer programme as well as how participation contributes to health and well-being. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University.

Researchers’ role and assumptions

The core team consisted of a family physician and healthcare services researcher (HA), a geriatric psychiatrist and health services researcher (JJ), a BA-trained study coordinator (EK), a research nurse expert in community-academic partnerships (LB), a qualitative health researcher (TL), a nurse programme leader in a peer programme (JF), and a research coordinator with experience in healthcare services research (EK). EK, JJ, and TL conducted interviews, and all team members participated in regular data analysis meetings. All authors acknowledged that they brought to the study assumptions that became part of the analytic process which were balanced by our approach to use grounded theory to let the themes emerge from the data rather than impose a conceptual framework.17

Population selection

We used a convenience sampling strategy to identify 7 peer support programmes (3 healthcare based and 4 community based) that was chosen with a focus on the diversity of the populations they served, the variety of settings and a record of sustained services. The programmes were identified through established relationships and input from experts in the field (Table 1). We used the following selection criteria: (i) programme offered peer support to patients, family-caregivers, or both, (ii) peer support included group meetings, one-on-one mentoring, or both, (iii) peer support was delivered face-to-face or by telephone (i.e. online-only programmes were excluded), and (iv) peer support activities were led by peers alone or co-led by peers and healthcare professionals. The Weight Watchers programme opted out of sending the recruitment flyers citing proprietary reasons and we only interviewed programme leaders within that programme. Among the programmes that were chosen, we approached programme leaders who circulated recruitment flyers to key informants (peer supporters and peer support recipients) within their programme. To obtain multiple perspectives e.g. interpersonal as well as organizational levels, we interviewed programme leaders (PL), peer supporters (PS), and peer support recipients (PR) within each peer programme. We aimed to interview 5–7 key informants.

Table 1.

Characteristics of interviewed key informantsa from project peer support programmes (N = 43).

| Interviewee characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |

| 25–44 | 11 (26) |

| 45–64 | 26 (62) |

| 65+ | 5 (12) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 35 (87) |

| Ethnicityb (N = 39) | |

| Asian | 3 (8) |

| Black or African American | 12 (30) |

| Spanish/Hispanic/Latino | 1 (3) |

| White | 23 (59) |

| Educational level | |

| Some high school | 2 (5) |

| High school graduate or GED | 3 (7) |

| Some college or Associate degree | 4 (9) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15 (36) |

| Advanced degree | 18 (43) |

| Role in peer programmec | |

| Peer programme recipient | 15 |

| Peer supporter | 14 |

| Programme leader | 14 |

| Peer programmes | |

| Programme A | 8 (20) |

| Programme B | 6 (15) |

| Programme C | 5 (12) |

| Programme D | 9 (22) |

| Programme E | 5 (12) |

| Programme F | 7 (17) |

| Programme G | 1 (2) |

Key informants in peer programmes included peer support recipients, peer supporters, and programme leaders.

This category contains missing participant data (number of participants for whom data was available included in parenthesis).

The highest level role was assigned to each participant, e.g. a programme leader may have experience as peer supporter.

Data collection

Three of the authors (EK, TL, and JJ) all of whom were trained and experienced in conducting qualitative research obtained oral consent and conducted interviews independently lasting 45–60 min with each participant in person (if available in the Baltimore area) or by telephone. The authors did not have a prior relationship prior to the participants and were introduced to the key informants as research team members and a description of the study was given. We also asked about any negative effects of participation. Data were collected from 7 April 2016 to 24 March 2017. Informants did not receive interview questions prior to the interview. All interviews were audiorecorded and professionally transcribed. No interviews were repeated and no fieldnotes were taken. NVIVO was used to code, develop a coding schema or coding tree which was used to analyse the data.

Data analysis strategy

We conducted qualitative data analysis of the interview transcripts using grounded theory which is an inductive approach used to develop a theoretical understanding through iterative analysis of qualitative data.18,19 A subset of 3–5 transcripts were used to conduct initial coding by 3 research team members and an initial list of codes was developed. The initial coding list was applied to the other subsequent transcripts and new codes were added to the list. We then proceeded to intermediate coding. We used the constant comparative method, moving between codes, different transcripts, and themes to arrive at a conceptual understanding of how participants benefit from peer support programmes and the challenges in providing it. Our goal was not to fit the data to preconceived ideas of peer support programmes but to code openly to identify abstract, emerging concepts. We achieved data saturation when no new information was expected to be added that would enhance or change study findings.20 Finally, we conducted advanced coding with integration of categories identified through previous coding stages. The authors identified the themes based on their frequency across transcripts and also included less frequent themes to capture the breadth of the themes. We considered the impact of various factors such as whether the programme was hospital or community based, the health condition addressed by the programme and method of delivery of peer support e.g. individual or group. Analysis meetings were held weekly and any disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Trustworthiness

To assess trustworthiness, the findings from the analysis were shared with study participants from each of the peer programmes to confirm that the results were consistent with their perspectives.

Results

Sample characteristics

We interviewed 43 key informants from 7 peer support programmes who had varying roles (Table 1). We found that the majority of the informants (41/43) in our study were persons who had personal experience with the target health condition whether working in the role of peer supporter or programme leader. Table 2 describes organizational characteristics and services offered in the peer programmes that participated in this study.

Table 2.

Description of peer support programmes.

| Setting | People served | Health state/condition | Programme location | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Community | Patients | Family | ||||

| Programme A | √ | √ | Substance abuse community-based | Local (12-step meetings are global) | Offers one-on-one peer counselling and support in person, includes 12-step meetings (e.g. Narcotics Anonymous/Alcoholics Anonymous) available 24/7. | ||

| Programme B | √ | √ | √ | Mental illness community-based | National | Offers peer-to-peer support groups to persons with mental illness and family caregivers; includes structured separate courses taught by peers and family-caregivers about coping with mental illness. | |

| Programme C | √ | √ | √ | √ | New mother hospital-based with community-based groups | Local | Offers telephone one-to-one support for new mothers for 12 weeks after delivery. Mothers are connected with mentors prior to their discharge from the hospital. Issues discussed may relate to mother or baby care. Support groups in community also provided. |

| Programme D | √ | √ | Children with disability community-based and connected to hospitals | National | Offers one-on-one telephone support to parents of children with disabilities by connecting the parent seeking support with a trained volunteer Support Parent. | ||

| Programme E | √ | √ | √ | Heart, liver, and lung transplant; breast, uterine, and ovarian cancer; cystic fibrosis hospital-based | Regional | Offers one-on-one peer support by telephone or in-person. Connects patients (and caregivers) with various health problems with trained mentors who have experienced a similar health condition. | |

| Programme F | √ | √ | √ | Cancer hospital-based | Local | Offers one-on-one peer support by cancer survivors to newly diagnosed patients by telephone. Includes family caregiver group supports. | |

| Programme G | √ | √ | Overweight and obesity community-based | National/some international | Offers peer group support via meetings and activities. Provides weight loss mentor. | ||

The benefits of peer support programmes

Psychosocial benefits: hope, support, and motivation to “get through this”

Table 3 summarizes the positive benefits that peer support programmes can bring to persons managing a health condition as well as caregivers and peer supporters themselves. This was expressed across all programmes. Persons with health conditions ranging from mental health, breast cancer, being overweight indicated that having a health condition was socially isolating and stigmatizing. A programme recipient said, “a lot of people will dismiss me because I have an illness.” Participants said being part of a peer support programme made them feel less alone, they appreciated the caring from peers and they felt a sense of belonging in a community that made them feel “normal,” “accepted,” and “connected” like a “family.” One peer supporter said that participation in a peer programme does not change the situation, but gave them hope, “Okay, maybe I can get through this.”

Table 3.

Themes on benefits of peer support from key informant interviews within 7 peer support programmes.

| Theme | Representative quote/s |

|---|---|

| Benefits of peer support programmes | PL—programme leader, PS—peer supporter, PR—peer support recipient |

| Psychosocial benefits | “…when you ask people what the best part is about, and regardless of which program you’re asking about, they tell you that the best part for them, the majority of the time and literally probably 60 to 70 percent, in any survey we’ve done, the biggest, the first, the top answer that we get, is that ‘the best part about it was finding out I’m not alone.’” (B, PL) |

| “I think when you are part of a peer to peer program, the main thing is that you don’t feel you are the only one in the world going through a difficult experience especially when have a heart transplant. It’s not just a surgery. It’s a transformation of your life. You are basically given another chance to live and that’s a good thing. So you don’t feel isolated when you have a mentor.” (E, PS) | |

| “To just hear almost like that survivor story really calmed my anxiety down and I knew I wasn’t alone. I think that’s the big fear is that everyone’s alone, especially when you get rare diagnoses. …And so it was just kind of regaining that hope and, you know, calming me down.” (D, PS) | |

| “It provides the patient that extra support that she is now talking to someone who’s been through what she is getting ready to go through, and is able to ask concrete questions like, ‘What did you do for this? How did you handle that?’ And more even physical, ‘How did you manage to take a shower? How did you manage to do the laundry? How did you manage to get in and out of bed?’, depending on the type of surgery. Also in regards to emotional supportive state that, ‘Yes, I had that two years ago. It was very difficult, but today I am alive and well and functioning in this capacity.’ So it’s two-sided for the physical information versus the emotional support.” (F, PL) | |

| Insight and impetus to change | “He didn’t even have a GED but because of this process [peer support] that he was able to recognize his self-value, then he started going to school and recognized that, ‘I can do better, I can do this.’ … He was able to recognize that if he wanted to change, he had to make that inevitable step forward and move on.” (A, PS) |

| “I believe that education from peers is much more readily accepted than education from professionals. Because if you see someone who has gone through what you’ve gone through and has tried something that works, then you’re more apt to try it too. … It was the case for me. … That has been the case for numerous people that I’ve run into contact with over the years. May not be the case for everyone, but that was a strong motivator for me. I saw a whole lot of people who were medication-compliant, who were seeing their doctors regularly, who had coping skills, who would say, “I can tell you what you can try that may help,” and I mean, I saw a lot of people, not just one, so it’s the numbers.” (B, PL) | |

| Role modelling | “…you see someone who’s just like you, who feels the same way as you, who has gone through similar things, who has the same illness as you, achieve. This particular woman has her own business. She’s a motivational speaker. She travels all over the country and before, she wasn’t like that.” (B, PL) |

| Connection to a social network and sense of community | “…a lot of moms make lifelong friends in our groups and sort of their families grow up together, and once the group has ended, they continue to support each other.” (C, mentor) |

| “And I think that’s a big part of the sense of community is the fact that people realize there is somewhere where you’re not the outcast. You know, we’ve all been there, done that. There’s really not much that you can say that will shock us. And it’s okay to talk about anything. … It’s extremely powerful.” (B, PL) | |

| Practical knowledge and resources | “… I was connected with so many people … [and] a bunch of different other resources that I think I’m getting a really good perspective from a lot of different people that live different ways.” (D, PS) |

| “With the moms group, I just learned an awful lot about what should be the normal course of development, both gross motor skills and then cognitive. You can read it in a book, but when you can see it in front of you happening, I think that really was educational for me.” (C, PS) | |

| “This place is open 24 hours a day, you know. There’s no other place better than this place to me, you know. What they have to offer, you know what I mean, as far as education-wise, GED and go to school, you know. Support as far as if you don’t have an income, they help you get a social service, you know, and public housing, you know.” (A, PS) | |

| Self-management skills and relapse prevention | “Well, it’s, you know, how to stay off of drugs. If you don’t pick it up, you won’t put it in you, you know. And staying focused. You know, staying clean. Places and faces, you know. For real. You know, ‘cause they say can’t nobody stop you from growing but you, you know.” (A, PS) |

| “I pay more attention to my symptoms. I have a better idea of what to look out for as far my early warning signs. Before I did the relapse vision chart, I hadn’t really spent a lot of time thinking about my previous relapses and how they began and how they spiraled out of control. … I’m catching my relapses earlier and earlier and not being in the emergency room or the hospital as often.” (B, PS) | |

| Navigation of health services | “I’m like a guide. Different resources, we communicate with, build relationships with, so if a person comes in, if they can’t get the help that they need here, we can refer them to other places. So, I considered myself like a walking guide.” (A, PS) |

| “So that’s what I needed, I needed the networking piece and I needed somebody to say, ‘This is a good place to start, this is a good person to call,’ and just sort of get me and our family plugged into not the overall autism community because I think that’s kind of easier to do, but my son has what they used to consider, Asperger’s and what I have found is in that particular community it’s really hard to find services and peers. So I was hoping that Parent 2 Parent could help me with that.” (D, PR) | |

| Benefits to caregivers | “It was a lady who was a caregiver. She explained to her what she had to do, how to handle the situation. And I don’t think my wife had any idea what she was getting into frankly. … that woman was explaining to her what she would have to do. I think it’s actually the first two months after the transplant it was kind of difficult. I mean they are really hard for both the patient and the caregiver. And that was a very important way to help getting started.” (E, PR) |

| “… that one mom was very caring and said “We have to hook you up with some helpers here.” I teach my son to look for the helpers in his life. The helpers have to be pulled into the parent’s life too and right early, not when she’s 52 and could throw herself out the window…” (D, PR) | |

| “I think it gave me the confidence to ask questions. If I had a question for a physician or somebody providing services for my son I feel like I had the conversation once with somebody to maybe role-play that, and so it enabled me to continue that as I was advocating for services for my son.” (D, PS) | |

| Benefits to peer mentors | “What I hear the most is that it helps … whether you’re involved administratively or involved as a teacher or a mentor, that it helps with our own recovery and wellness to be actively involved in helping others. … there’s something very healing about being able to give back and to be able to stay engaged and also be involved in doing something where it’s okay if I’m not doing absolutely wonderful all the time.” (B, PL) |

| “So it’s a win-win situation. You feel that you are doing something for somebody else and at the same time, you are doing something for yourself in terms of understanding life as a gratitude.” (E, PS) | |

| “[The program] does help me too, because it helps me know that I’m helping other people, and so everything I’ve learned matters, because I’m able to help other people, so it’s like a continued therapy for me as well being able to help these other families.” (D, PS) | |

| Peer support complements medical care | “They had a heart transplant. And who could I ask, you know. Who had been there, basically. You know, ‘cause no matter what, you can go to—you can tell a doctor or whoever how you feel, but if they haven’t literally went through the procedure or whatever, they can only understand so much.” (E, PR) |

| “Where … I feel that my skills are not suitable, that’s where I report it … I don’t think I’m able to give that person that assistance and help that they need, I think it’s either pathological or something beyond that, … and that really needs a social worker or a psychologist or something to intervene and that’s what I do.” (E, PS) | |

| “I wish I would’ve known these powerful … Peer-to-Peer people when [my child] was two and that it would be part of the care plan… I wish when the child is diagnosed that it’s part of the algorithm to pull Peer-to-Peer in way back then. … It’s self-care. … when the child is diagnosed that that’s part of the doctor’s algorithm, then respite gets in place right away. …Respite and peer-to-peer support has to be part of the care plan right from the beginning, because then there’s something left of Mom.” (D, PS) |

Through the community of people in peer programmes, participants saw and interacted with role models like themselves who overcame disabilities, something they rarely encountered in their daily lives. Observing and interacting with role models with the same illness who were able to achieve life successes could increase self-esteem and feelings of empowerment. A programme leader who herself had a chronic mental health condition described how she was motivated to change: “When I met a group of people who were medication-compliant, who regularly saw their psychiatrist and their therapist, and who stayed well enough to work and stayed well enough to function in the community, I said, ‘Well, I want that, so I’m going to try that too.’” (Programme B, PL)

Practical self-care knowledge: information about resources and self-care skills—“I just learned an awful lot”

Programme participants said they learned practical information about managing their health condition through talking with others whom they met through the peer programme. For example, a programme participant in a hospital-based programme who was matched after surgery gained information about how to manage drains after breast cancer surgery to maximize sleep or how to get out of bed when depressed or in pain. She got answers to practical questions such as “how do you take a shower after a surgical procedure?” (F) A recipient of peer support who participated in a programme for new mothers said, “both [peer] programs just helped me learn a lot about how to be a good parent.” (C, PR) A peer supporter learned relapse prevention skills and keeping up with her treatments to remain out of the hospital. Peer support programmes also helped people connect to resources for transportation, with navigation of health services, and helped people understand their available options.

Benefits to family-caregivers

Some programmes focussed on supporting caregivers whose needs were not always met during medical appointments where the focus was the patient. Caregivers said that peer supporters helped orient them to their role (e.g. helped them anticipate the life changes that were needed to help a family member cope successfully after a transplant surgery). For some caregivers, engaging in peer support programmes was a fundamental way in which they coped and managed the illness of a loved one and also enabled them to engage actively with physicians. One parent with an autistic child, who received peer support said that “I think it gave me the confidence to ask questions. …it enabled me to continue that, as I was advocating for services for my son.” (D) Despite the benefits, caregivers said other life demands and caring for a disabled child were barriers, so that “it can be hard to find a good time to connect with your other parent [peer supporter who is a parent].” (D, PS) Connecting by telephone was the easiest in this context; however, “…so many people want that face-to-face connection.” (D, PL) Yet, in-person meetings can be more difficult especially when geographical distance is a barrier.

Benefits to peer mentors

Both those providing and receiving peer support benefitted. Peer supporters across all programmes expressed the effect of a positive experience giving support to others, “I’ve learned so much through my journey. Let me share with everyone else.” (D) Peer supporters said that they found emotional and social benefits by serving as role models and coaches, and that increased their confidence in their own ability to overcome challenges related to their health. Peer supporters said they experienced enhanced sense of purpose by helping others overcome similar struggles. As 1 peer supporter said, “it helps with our own recovery and wellness to be actively involved in helping others.” (A)

Peer support programmes can complement medical care

Some programmes that are hospital based or connected with health systems received referrals from professional staff. For example, in the programme for new mothers, “they [new mothers] get the information in a packet from their obgyn … at the hospital when they deliver their baby.” (PS) A peer mentor who cared for a disabled child stated that “… anytime you get that new diagnosis, I think, people can really benefit from it [peer program].” (D, PS) A programme leader who herself was a nurse with experience of breast cancer described direct benefits to healthcare providers. For example, peer supporters offered a calming and supportive presence to a cancer patient during a biopsy that decreased the patient’s anxiety and made the biopsy easier to conduct for the healthcare provider.

Programme recipients who had experience with a medical condition stated that in addition to having medical professionals (e.g. physicians, nurses, or psychotherapists), having peer supporters who have “lived it” offered was complementary to what healthcare professionals provide. One peer support recipient stated that “doctors were very, very good at explaining to me basically what the operation would be. They cannot explain to you really what’s happening after.” (E)

Peer programmes also can connect persons with clinical symptoms to professional care and clinical services. In peer programmes that serve mothers with newborn infants and breast cancer survivors, peer supporters described how they identified signs of depression in a person they were matched with and referred this person to programme leaders who were healthcare professionals e.g. nurses or social workers. The new mother or cancer survivor could then be referred for further care as needed.

Challenges to peer support delivery and how they are addressed

There were common challenges shared by all programmes and specific challenges for each peer programme based on setting e.g. hospital or community based and format of their programmes. Table 4 lists themes around challenges faced by peer programmes and provides representative quotes that describe them.

Table 4.

Themes on challenges met by peer support programmes and how those are addressed, from key informant interviews within 7 peer support programmes.

| Topic | Representative quotes describing challenges and how programmes address them |

|---|---|

| Funding | “We’ve had so many challenges with funding that if we could find a way to really give some validity to the parent to parent, peer to peer model, that would give us the ability to fund raise. That would be huge because it is really something that I feel very, very valuable for families. And they report that it is, that it’s very helpful for them. They don’t feel so isolated, their confidence has increased. But yet, it can be really challenging to keep a program running just financially, sustaining it.” (D, PL) |

| “The retreats are very expensive. … it can go up to $20,000 for one retreat, so [the program] has latched onto some very philanthropic donors who help out with that. In fact one gentleman who lost his wife at a young age, to breast cancer, had come to our couples retreat one year and he had signed up to stay in that retreat into perpetuity financially. So usually it’s because we have touched someone with the support that we do provide that makes them want to step up and help us financially…” (F, PL) | |

| Barriers to supporting another person | “…people don’t usually wanna talk about tough subjects … sometimes it can be difficult to talk to a complete stranger about it, especially if you’re not confident in understanding” (D, PS) |

| “But it’s something that you have to be in acceptance with and you have to, you know, feel like you need the peer.” (E, PR) | |

| Boundaries and emotional entanglement | “I get emotionally upset but I have learned and we are in training for that. I have talked to a lot of people, I feel sorry for a lot of things that people are going through, but I try not to get too emotionally involved in it. I try to stay on a more professional side of it.” (A, PS) |

| “…there’s times when it really gets to you because it brings back everything you had been through. But they know that and talk about that in the training and there’s not too much you can do about that and it’s just part of it.” (E, PS) | |

| Fidelity to the programme | “When we hear about things that are going on out in the field that are not true to the model, it’s typically from another teacher or mentor or trainer in the community who hears about it and calls us.” (D, PL) |

| “There is a support structure. We … at the national level look to the state organizations to provide that technical assistance and oversight for the affiliates and the leaders that are actually doing the classes, teaching the programs, running the support groups, et cetera. We do have a non-certification process and a de-certification process. So we do have a process where if, for example, I’m a state trainer and I’m doing a training here in Mississippi and there are people who come to the training and I just don’t really think they’re ready to teach a course, there’s a process in place for me to work with my affiliate to let that person know that, you know, why they don’t meet the criteria and what recommendations are made to either bring them up to speed, including a recommendation to just, you know, ‘You need to go back out and take the class again and come back next year.’ There’s also a process for decertifying a teacher or a support group facilitator where if for some reason it comes to the affiliate or the state organization’s attention that maybe the person is not doing the best job.” (B, PL) | |

| Geographical restrictions | “Our program is located in a larger city, …, but we also serve five surrounding counties that are more rural. And it is very challenging to provide services in those counties … So that’s why a lot of our contact is done over the phone.” (D, PL) |

| “Some of the other challenges are just geographic … they might wanna meet with somebody, but then it’s trying to work it out. If they wanna to meet face-to-face, when are they down to clinic… When can they come in?—that type of thing. But we do try to do a lot by phone and email.” (E, PL) | |

| Matching based on condition and cultural similarity | “So I think the condition has to be similar to you, from the mentor to the mentee. Even though the experiences are always different, the condition, I think they have to be similar, and also I think it’s important if the patient has a cultural background that the mentor understands that cultural background as well.” (E, PS) |

| “So if it was a patient undergoing mastectomy we’d match her with a mastectomy patient and then we try and see maybe reconstruction versus no reconstruction and then narrow that down a little bit more to the type of reconstruction and then also age if we’re able to get it closer in age.” (F, PL) | |

| “I think that the barrier would be that my son had a very rare condition, so there weren’t necessarily people available … eventually I think I kind of honed in on saying ‘Well, it would be really helpful to talk to another parent that has a child with a G-tube that has significant cognitive delay …’ those kinds of things. So I think it was easier for us then to kind of hone in on those more conditions than diagnosis….” (D, PS) | |

| “We offer a new match. We—because we follow our matches, we follow up at one to two weeks to make sure that the match has happened. And that they’re comfortable with it. And then, we send a—at three weeks, we send an email to the support parent to remind them to call the parent.” (D, PL) | |

| “I try to match on issues. So for example, I had a 45-year-old man with a heart transplant that his main issue was talking about rejection issues. I was able to match him with a woman in her 60s that had gone through some rejection issues with her transplant. So, that was really what his concern was, and I found that that match worked really for both of them.” (E, PL) | |

| Need to convince professional providers | “That was a hard nut to crack. They [physician] could see the benefit of the volunteer in the room when they weren’t in the room, but we had to show them the benefit of having the volunteer meet the patient before she goes into the room [for a biopsy] and kind of get that sense of calmness, you know… it took us to actually show the physicians that, and now they ask for a volunteer.” (F, PL) |

| Because people can get territorial over there and not—I shouldn’t say that they should, but as they do, “This is my patient and there’s someone coming into the room that maybe I’m not sure what they’re doing or why they’re here, what purpose do they bring,” and they’re thinking maybe in a different line of thought as to more medical interventions as opposed to maybe more emotional support. So it’s important that we blend those two and that they’re well aware that that’s what we’re doing and nothing more. (F, PL) | |

| “I sent letters out to the cardiologists explaining that this program is here, and a few of the cardiologists reached out saying ‘Well, we have experienced parents within our practice that we would like to refer to be support parents,’ and I felt like I’ve done a lot of education of the staff to let them know that this program exists and the importance of having a parent matched with another parent who’s sort of walked in a similar path, and so I ended up getting a grant to help publicize the program.” (D, PL) |

Emotional barriers to providing peer support

Programmes leaders of all programmes described 1 common challenge that is associated with the nature of using peer supporters whose experiential knowledge define their role, but also can be the source of their vulnerability. Programme leaders indicated that peer supporters may have difficulty discussing traumatic periods in their own life, and as 1 peer supporter stated, “there’s times when it really gets to you because it brings back everything you had been through.” (E) There was also the stress of supporting others who are ill or struggling with caregiving. As 1 peer supporter stated, “The biggest challenge that I know for myself is that if you’re … taking on a lot of people worries, their problems because I have to watch myself too… I am a recovering addict too, so if I lose myself trying to help somebody else, game over.” (A) Balancing personal involvement and maintaining boundaries were described by peer supporters and programme leaders as important aspects of ensuring a successful peer support relationship. Several programmes reported discussions on maintaining boundaries during training activities and offered support services to ensure continued well-being of peer supporters (e.g. encouraging taking time off when the peer supporter feels ill or vulnerable).

Fidelity to programme procedures and ensuring adequate delivery of services

Programme leaders described careful attention to selection of peers, and providing orientation/training and continuous support. Common areas of guidance for peer supporters were around safeguarding against being judgemental or providing medical advice. Programme leaders stated that they carefully evaluate the readiness of peers to provide support and “if I feel that they’re not ready to mentor, but they want to be involved in improvements or things at our facility, then I refer them” for other roles in the programme. (E) National peer support programmes had manuals and teams devoted to conducting training. Healthcare-based programmes had training that included patient privacy and documentation matters, and had healthcare professionals (clinical social workers and nurses) who provided supervision and continuous support services to peer supporters. A programme leader of a national peer programme said continuous monitoring and participant evaluations used to ensure that “certain standards, standard operating procedures and policies” and “a code of conduct that we ask people to sign when they become trained.” (B) The programme leaders of smaller programmes (with local reach) described processes to address these same challenges through less-structured, informal processes.

Matching

Leaders of programmes where individualized peer support is provided described the challenges of matching peer supporters and programme participants based on similarities. For those programmes that provide services to persons with rare health conditions, typically in hospital-based programmes, the availability of peer supporters with the health conditions e.g. a chromosomal abnormality or a subtype of breast cancer, was described as “limited,” especially in nonurban settings. Programme leaders said they addressed this challenge by matching based on issues rather than a rare health condition. Some programmes that only provide connection by telephone and rely on successfully matching said they sometimes checked up on the matches after the initial call and offered other matches if the initial matches were not successful. The peer programmes offering addiction recovery services, mental health and programmes for weight control did not report having these problems. These programmes said they did not focus on individual peer support services and some said they used group support that brings people together with similar conditions. In these programmes, one-to-one interactions may occur but was not the focus. A peer supporter who leads peer support groups believed that the group format may be helpful to share information such as resources, but one-to-one facilitated sharing of personal information and struggles more readily.

Discussion

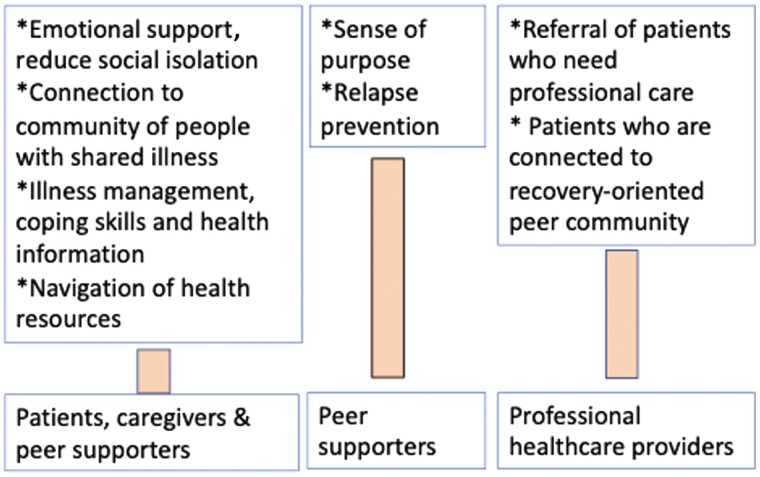

The goal of the study was to look at a diverse sample of peer support programmes operating within both community and healthcare settings in order to explore the benefits of peer support and the challenges to its delivery in real-world settings. Our findings show that peer support programmes can have positive benefits for persons with a health problem, their caregivers, the peer supporters themselves. The various benefits for peer recipients include psychosocial support, reduced social isolation, improved knowledge of self-care skills, navigation of the health system and connection to community-based resources (see Fig. 1). The peer supporters derive a sense of purpose from their role which can help maintain recovery from their illness. The healthcare professional may also benefit indirectly when their patients learn self-care skills and connect to a support system that encourages using relapse prevention skills and community-based resources. Our study also reported on current challenges met by operating peer support programmes and how those are being addressed. Our results extend the existing research on peer support by showing the benefits of established and operating peer support programmes that currently provide services for a broad variety of health conditions.

Fig. 1.

Identified benefits of peer support programmes.

Our results are consistent with studies and conceptual theories exploring mechanism and underlying processes of peer support.21–23 Our study suggests that loneliness and social isolation are common in persons struggling with health conditions and they want support that extend beyond medical care.24 We know from an abundance of evidence that social isolation and loneliness are associated with a host of negative health outcomes.25,26 Mood problems such as depression and low sense of purpose have been shown to be associated with poor health27–29 and can negatively affect engagement in health services as well as adherence to medical treatments.30–32 For technical care and medical information, people turn to healthcare professionals, but when the need pertains to questions about daily living and coping with a health issue, or seeking emotional support, then other peers who have experiential knowledge may be preferred.33

In addition to psychosocial support, participants in our study valued peer support programmes for practical information about illness management and help with navigation of clinical and community resources. Peer support programmes encourage self-help and can connect participants to a social network of individuals with knowledge and experience with similar health conditions. This can help participants improve their ability to manage their health conditions and help caregivers better care for a child or family member. Use of peer support as a self-management resource has been shown to be effective in diabetes, and emerging evidence exists for its benefits in individuals with depression, but use of peer support for the breadth of health conditions that the programmes in our study work examined, has not been extensively studied.34,35

Challenges in delivering peer support programmes exist. Participants in our study articulated challenges such as peer to peer matching, peer relationship boundaries, and Scepticism from professional providers. Similar challenges have been found in studies of existing peer programmes in mental health and peer support in primary care settings.36,37 To ensure a positive and beneficial experience for participants, existing peer programmes have put processes in place to ensure good selection, training and oversight of peer supporters, use of manuals in some cases, and education and relationship building with professionals to encourage trust in the programme and referral of patients. Few implementation studies of peer support interventions exist and which organizational strategies lead to important programme outcomes such as fidelity, quality, or health outcomes has not been well established.7,38,39 Further studies are needed to determine how programmes can address these challenges and ensure effective peer support delivery. Our qualitative study helps generate hypothesis for further testing, but does not provide generalizable results on effectiveness of peer programmes.

This study has some limitations. First, we have partnered with a small group of peer programmes and our findings may not represent all operating peer support programmes. However, the intent behind this qualitative study was to explore the potential value of peer support outside of research settings for a broad range of health conditions and the real-world challenges to delivery of peer support, rather than to conduct an in-depth study or assessment of specific programmes. For the latter, a quantitative assessment focussing on specific clinical and satisfaction outcomes would be more appropriate. Second, the number of key informants interviewed varied across the partner programmes which was often the result of variable programme size. Third, for Programme G only 1 key informant was interviewed. This was due to a decision made by the leadership of this programme to limit key informants to 1 high level leader to avoid inadvertent disclosure of proprietary information. Compared with multiple interviews obtained from other programmes; however, the interview provided information on another health condition and a different programme. Fourth, the programmes in our study focussed on 1 health condition and do not include descriptions of how persons with multimorbid health conditions might benefit from peer programmes. Finally, our study cannot show whether the intensity of programme participation or type of support received had a differential impact on participant experience.

Conclusion

Existing peer programmes that operate in hospitals and community-based settings can be an important resource for patients, caregivers, and health systems. Future studies are needed to compare effectiveness of various peer support delivery approaches. Further research to illuminate core components of peer support, training, supervisory, and evaluation processes to ensure effectiveness for multiple health conditions will also be helpful towards expanding the availability of these programmes. Such evidence can increase the availability of these programmes to patients and families.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Jin Hui Joo, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Meyer 235, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Lee Bone, Department of Health, Society and Behavior, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Joan Forte, Formerly Department of Patient Experience, Stanford Health Care, Sunnyvale, CA, United States.

Erin Kirley, Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Thomas Lynch, Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Duke University, Durham, NC, United States.

Hanan Aboumatar, Department of Health, Society and Behavior, Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States; Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States; Department of Medicine, School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health under grant K23MH100705, and through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Eugene Washington PCORI Engagement Award (2463-JHU).

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University. This not a cohort study nor a trial.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interest such as affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or nonfinancial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Data availability

Data available upon request.

References

- 1. Center for Community Health and Development. Community Tool Box. University of Kansas; 1994–2021. [accessed 2021 Nov 5]. https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/implement/enhancing-support/peer-support-groups/main [Google Scholar]

- 2. University of Michigan Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center. National analysis of peer support providers: practice settings, requirements, roles and reimbursement. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan School of Public Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reif S, Braude L, Lyman DR, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, Shoma Ghose S, Salim O, Delphin-Rittman ME.. Peer recovery support for individuals with substance use disorders: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(7):853–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dixon LB, Lucksted A, Medoff DR, Burland J, Stewart B, Lehman AF, Fang LJ, Sturm V, Brown C, Murray-Swank A.. Outcomes of a randomized study of a peer-taught Family-to-Family Education Program for mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(6):591–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dennis CL, Hodnett E, Kenton L, Weston J, Zupancic J, Stewart DE, Kiss A.. Effect of peer support on prevention of postnatal depression among high risk women: multisite randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338(7689):a3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin K, Yang C, Sun CJ, Latkin CA.. Results of a randomized controlled trial of a peer mentor HIV/STI prevention intervention for women over an 18 month follow-up. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1654–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shalaby RAH, Agyapong VIO.. Peer support in mental health: literature review. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7(6):e15572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Berg RC, Page S, Øgård-Repål A.. The effectiveness of peer-support for people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0252623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mizokami-Stout K, Choi H, Richardson CR, Piatt G, Heisler M.. Diabetes distress and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: mediator and moderator analysis of a peer support intervention. JMIR Diabetes. 2021;6(1):e21400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moriss R, Kaylor-Hughes C, Rawsthorne M, Coulson N, Simpson S, Guo B, James M, Lathe J, Moran P, Tata L, et al. A Direct-to-Public Peer Support Program (Big White Wall) versus web-based information to aid the self-management of depression and anxiety: results and challenges of an automated randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e23487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, Bona JR, Fricks L, Jenkins-Tucker S, Sterling E, DeClemente R, Lorig K.. The Health and Recovery Peer (HARP) Program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res. 118(1–3):264–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang R, Yan C, Tian Y, Lei B, Yang D, Liu D, Lei J.. Effectiveness of peer support intervention on perinatal depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:788–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fisher E, Coufal MM, Parada H, Robinette J, Tang P, Urlaub D, Castillo C, Guzman-Corrales LM, Hino S, Hunter J, et al. . Peer support in health care and prevention: cultural, organizational, and dissemination issues. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:363–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davidson L, Bellamy C, Guy K, Miller R.. Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(2):123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Flock SA, Gill JM.. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):601–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Barr VJ, Robinson S, Marin-Link B, Underhill L, Dotts A, Ravensdale D, Salivaras S.. The expanded Chronic Care Model: an integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the Chronic Care Model. Hosp Q. 2003;7(1):73–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marshall C, Rossman GB.. Designing qualitative research. 7th ed. Los Angeles (CA): Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glaser BG, Strauss AL.. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York (NY): Aldine Publishing; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chun Tie Y, Birks M, Francis K.. Grounded theory research: a design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Med. 2019;7:2050312118822927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guest G, Brunce A, Johnson L.. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Embuldeniya G, Veinot P, Bell E, Bell M, Nyhof-Young J, Sale JEM, Britten N.. The experience and impact of chronic disease peer support interventions: a qualitative synthesis. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92(1):3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Solomon P. Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27(4):392–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dennis CL. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(3):321–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heisler AB, Friedman SB.. Social and psychological considerations in chronic disease: with particular reference to the management of seizure disorders. J Pediatr Psychol. 1981;6(3):239–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kawachi I, Berkman LF.. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health. 2001;78(3):458–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, Cacioppo JT.. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(6):907–914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fanakidou I, Zyga S, Alikari V, Tsironi M, Stathoulis J, Theofilou P.. Mental health, loneliness, and illness perception outcomes in quality of life among young breast cancer patients after mastectomy: the role of breast reconstruction. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(2):539–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Berkman LF, Glass TA.. Social integration, social networks, social support and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, editors. Social epidemiology. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Berntson GG.. The anatomy of loneliness. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12(3):71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Latkin CA, Kuramoto SJ, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE.. Social norms, social networks, and HIV risk behavior among injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hagerty BM, Lynch-Sauer J, Patusky KL, Bouwsema M, Collier P.. Sense of belonging: a vital mental health concept. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1992;6(3):172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Coyne JC, Downey G.. Social factors and psychopathology: stress, social support, and coping processes. Annu Rev Psychol. 1991;42:401–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Fox S. Peer to peer healthcare. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yeung A. Self-management of depression. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lorig K, Ritter PL, Villa FJ, Armas J.. Community-based peer-led diabetes self-management: a randomized trial. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(4):641–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moran GS, Russinova Z, Gidugu V, Yim JY, Sprague C.. Benefits and mechanisms of recovery among peer providers with psychiatric illnesses. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(3):304–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Repper J, Carter T.. A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. J Ment Health. 2011;20(4):392–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chinman M, Shoai R, Cohen A.. Using organizational change strategies to guide peer support technician implementation in the Veterans Administration. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2010;33(4):269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chinman M, Salzer M, O’Brien-Mazza D.. National survey on implementation of peer specialists in the VA: implications for training and facilitation. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2012;35(6):470–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.