Modern oncology practice is increasingly complex. Patients and clinicians are faced with a growing array of possible interventions—from novel chemotherapeutics to immunotherapies and cancer vaccines, alongside advances in palliative and supportive therapies and increasing roles for advanced diagnostics such as advanced genomic sequencing, circulating tumor DNA, and artificial intelligence. With these advances come numerous potential ethical challenges. These include nuanced questions related to balancing goals of cure and symptom palliation, navigating therapeutic misconceptions and conflicts of interest, and the role of hope/hype in emerging technologies such as precision medicine and artificial intelligence in oncology.1-4

Despite these ethical challenges, limited empirical work has been performed examining the role and practice of clinical ethics in oncology. The bioethics literature is sparse in this space, with but a handful of descriptive analyses of ethics consultation volume, ethicist training, and consult themes/content.5-14 In oncology, empirical literature around ethics consultation is limited primarily to practice characterizations of a pediatric oncology center,9 a medical oncology intensive care unit,8 and a review of consultations at a large cancer center early in the COVID-19 pandemic.7 These reports collectively demonstrate that ethics consults in oncology often respond to conflicts between clinicians and surrogates about some of the most fundamental considerations in oncology practice, such as those related to treatment decisions and/or end-of-life care. After consultation, most conflicts are reported to be amicably resolved. Details on the content, value, and outcomes of ethics consultation in oncology are limited, however, and more empiric research is sorely needed.

It is in this context that Marathe et al15 describe their experience with the creation of an ethics consultation order in the electronic health record (EHR) in the manuscript accompanying this editorial. The authors retrospectively reviewed the volume of ethics consults received at their large tertiary cancer center in the 17 months before and after they instituted an order in the EHR with which clinicians could request an ethics consultation. Of note, the authors chose this timing to avoid potential bias due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which erupted in the United States soon after the end of the studies post-implementation period.

After the establishment of an EHR order to request an ethics consultation, the authors identified an increase in consultations, both in absolute number of consults and in consults per patient. These results were consistent in both the inpatient and outpatient settings.15 We commend the authors for this interesting and important work. Indeed, they recognized the value of ethics consultation in oncology, identified a potential barrier to accessing such consults, and attempted to surmount that barrier with a common sense (and likely inexpensive) intervention.

On the other hand, several questions about their conclusions remain. First, can we reliably state that offering an orderable consult request in the EHR is what drove the described increase in consult volume? Second, and perhaps even more importantly, what does an increase in consult volume tell us about consult quality? The authors thoughtfully address the first question, acknowledging that their report of the correlation of consult volume with implementation of the EHR order does not imply causality due to the potential presence of unmeasured confounding factors and secular trends. Importantly, a recent large cross-sectional analysis of ethics consultation volume in US hospitals demonstrated that ethics consultations have increased over the past 2 decades, particularly among large institutions similar to that described by Marathe et al.15 As a result, it is conceivable that the increase in consults was a local manifestation of a more general trend and not one related to the EHR order. Regardless, there is value in oncology clinicians having ready access to ethics consultation services, and attempts to break down barriers to consult access are laudable, even if the impact of the intervention versus other factors might be difficult to quantify.

If the goal of the intervention is to expand access and promote resolution of ethical dilemmas in oncology care, the second question about how quantity and quality of consultation are related is even more important. Ethics consult volume is sometimes used as a proxy measure for quality,16 and a robust literature in health care describes lower-quality care and higher mortality rates with lower-volume interventions, both at the level of the hospital and the individual practitioner.17-19 In oncology, similar relationships are evident, with lower operative mortality rates and better long-term outcomes after oncologic surgery at high-volume centers,20,21 and nonoperative survival for a variety of cancer subtypes also associated with higher patient volume.22

Does this intuitive relationship hold true for ethics consultation volume? One could hypothesize that a larger number of ethics consults indicate perceived value by clinicians, patients/surrogates, and others who request these services. After all, why would a large number of consults continue to be requested if they were not seen as helpful? On the other hand, higher volume could actually be a marker of ineffective ethics services (ie, ongoing, unsolved ethical concerns) or it could signify frequent ethically questionable actions that require the support of ethics experts to navigate or the presence of distressing or otherwise ethically troubling circumstances requiring additional support. Indeed, a prior publication in JCO Oncology Practice identified an increase in the frequency of ethics consultation requests at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic,7 truly a uniquely ethically troublesome period, given questions of rationing care, disparities in access and outcomes, and widespread sharing of disinformation/misinformation.23-26

If ethics consult volume does not always reliably predict ethics consult quality, are there other evidence-based quality metrics for ethics consultation? Although publicly funded federal programs such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and public-private partnerships such as the National Quality Forum have spearheaded efforts to define high-quality practices across health care disciplines in the United States, similar work in clinical ethics is only in its infancy. The American Society for Bioethics and Humanities (ASBH), the leading bioethics organization in the United States, has published Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation, which aims to describe standards for ethics consults (and the ethics consultants who perform them).27 The most recent edition of this report, published in 2011, provides a valuable framework for examining the quality of ethics consultation services, but the quality metrics seen in most other areas of clinical practice are largely absent. Importantly, a third edition of this guidance is currently in preparation (J.M.M. acknowledges being a member of the task force preparing this text), which will recognize the general paucity of evidence-based quality metrics in this area and call for the development of robust quality standards.

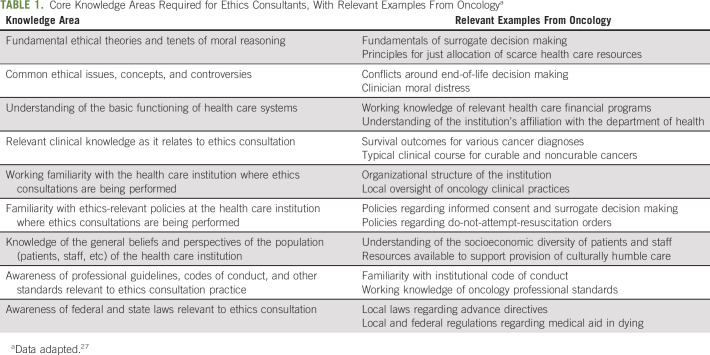

Limitations notwithstanding, the ASBH Core Competencies provide valuable resources for those performing ethics consultation in oncology. Table 1 describes nine core knowledge areas required of ethics consultants as identified by the ASBH,27 with relevant oncology-focused examples. Ethics consultants in oncology should have a working knowledge in these areas or at least ready access to those with such expertise. We currently lack data regarding what qualifies as high-quality ethics consultation practice, but this gap in the literature is increasingly recognized,28-30 with efforts underway to develop evidence-based standards for ethics consultation.

TABLE 1.

Core Knowledge Areas Required for Ethics Consultants, With Relevant Examples From Oncologya

In absence of such standards, those performing ethics consultations in oncology who wish to undertake quality assessment/improvement work must make do with surrogate markers for consult quality or other metrics without a strong evidence base. Marathe et al15 make a valiant effort in demonstrating greater ethics consult volume at their oncology center after implementing an order for such consults in their EHR. Although we cannot be certain that the higher volume of consults reported by the authors after their intervention corresponds with increased consult quality, aiming to ease barriers to access to ethics consultation remains meaningful. It is important for practicing oncologists to understand what ethics consults involve and what skills and competencies those conducting such consults bring to the bedside. Looking ahead, it will be important for the growing field of clinical ethics consultation—both in oncology and more generally—to use similar rigorous standards for quality assessment and improvement to those used in other areas of health care. In the meantime, as the field of oncology continues to grow in complexity, ensuring that patients, surrogates, clinicians, and staff all have ready access to ethics consultation services remains critical, even if we lack data to state with certainty that consult volume is a reliable proxy for consult quality.

Jonathan M. Marron

Honoraria: Genzyme

Consulting or Advisory Role: Partner Therapeutics

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/802634/summary

Jeffrey M. Peppercorn

This author is the Editor-in-Chief designate for JCO Oncology Practice. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Employment: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Athenex, Abbott Laboratories

Research Funding: Outcomes4Me

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

See accompanying article on page 674

DISCLAIMER

The funders/sponsors had no role in the preparation of this manuscript.

SUPPORT

J.M.M. receives research funding from the Palliative Care Research Cooperative Group (PCRC) and the National Institutes of Health. A.H. receives funding from the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the Greenwall Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health. G.A.A. receives funding from National Institutes of Health, the American Cancer Society, the Greenwall Foundation, and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: Jonathan M. Marron

Data analysis and interpretation: Jonathan M. Marron

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Ethics Consultation in Oncology: The Search for Quality in Quantity

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Jonathan M. Marron

Honoraria: Genzyme

Consulting or Advisory Role: Partner Therapeutics

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/802634/summary

Jeffrey M. Peppercorn

This author is the Editor-in-Chief designate for JCO Oncology Practice. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Employment: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: GlaxoSmithKline (I)

Consulting or Advisory Role: Athenex, Abbott Laboratories

Research Funding: Outcomes4Me

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Marron JM, Cronin AM, DuBois SG, et al. Duality of purpose: Participant and parent understanding of the purpose of genomic tumor profiling research among children and young adults with solid tumors. JCO Precis Oncol. 2019;3 doi: 10.1200/PO.18.00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hantel A, Clancy DD, Kehl KL, et al. A process framework for ethically deploying artificial intelligence in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 10.1200/JCO.22.01113 [epub ahead of print on July 18, 2022] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3. LeBlanc TW, Marron JM, Ganai S, et al. Prognostication and communication in oncology. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:208–215. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marron JM, Joffe S. Ethical considerations in genomic testing for hematologic disorders. Blood. 2017;130:460–465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-01-734558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fox E, Danis M, Tarzian AJ, et al. Ethics consultation in U.S. hospitals: A national follow-up study. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22:5–18. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2021.1893547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zaidi D, Kesselheim JC. Assessment of orientation practices for ethics consultation at Harvard Medical School-affiliated hospitals. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:91–96. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Friedman DN, Blackler L, Alici Y, et al. COVID-19-related ethics consultations at a cancer center in New York City: A content review of ethics consultations during the early stages of the pandemic. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e369–e376. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Voigt LP, Rajendram P, Shuman AG, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of ethics consultations in an oncologic intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2015;30:436–442. doi: 10.1177/0885066614538389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Johnson LM, Church CL, Metzger M, et al. Ethics consultation in pediatrics: Long-term experience from a pediatric oncology center. Am J Bioeth. 2015;15:3–17. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2015.1021965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Danis M, Fox E, Tarzian A, et al. Health care ethics programs in U.S. Hospitals: Results from a national survey. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22:107. doi: 10.1186/s12910-021-00673-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fox E, Danis M, Tarzian AJ, et al. Ethics consultation in U.S. hospitals: New findings about consultation practices. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2022;13:1–9. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2021.1996117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fox E, Duke CC. Ethics consultation in U.S. hospitals: Determinants of consultation volume. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22:31–37. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2021.1893548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fox E, Tarzian AJ, Danis M, et al. Ethics consultation in United States hospitals: Assessment of training needs. J Clin Ethics. 2021;32:247–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fox E, Tarzian AJ, Danis M, et al. Ethics consultation in U.S. hospitals: Opinions of ethics practitioners. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22:19–30. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2021.1893550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marathe PM, Zhang H, Blacker L, et al. Ethics consultation requests after implementation of an electronic health record order. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:e1505–e1512. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glover AC, Cunningham TV, Sterling EW, et al. How much volume should healthcare ethics consult services have? J Clin Ethics. 2020;31:158–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EV, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, et al. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2117–2127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR. Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:511–520. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Birkmeyer NJ, Goodney PP, Stukel TA, et al. Do cancer centers designated by the National Cancer Institute have better surgical outcomes? Cancer. 2005;103:435–441. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Birkmeyer JD, Sun Y, Wong SL, et al. Hospital volume and late survival after cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2007;245:777–783. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252402.33814.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Raphael MJ, Siemens R, Peng Y, et al. Volume of systemic cancer therapy delivery and outcomes of patients with solid tumors: A systematic review and methodologic evaluation of the literature. J Cancer Policy. 2020;23:100215. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marron JM, Joffe S, Jagsi R, et al. Ethics and resource scarcity: ASCO recommendations for the oncology community during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2201–2205. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Balogun OD, Bea VJ, Phillips E. Disparities in cancer outcomes due to COVID-19—A tale of 2 cities. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1531–1532. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marron JM, Charlot M, Gaddy J, et al. The ethical imperative of equity in oncology: Lessons learned from 2020 and a path forward. Am Soc Clin Oncol Ed Book. 2021;41:e13–e19. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_100029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guidry JPD, Carlyle KE, Miller CA, et al. Endorsement of COVID-19 related misinformation among cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105:265–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Core Competies Task Force . Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation. ed 2. Glenview, IL: American Society for Bioethics and Humanities; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Malek J. A call for evidence-based clinical ethics consultation. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22:40–42. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2022.2044566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kon AA. Quality healthcare ethics consultation: How do we get it and how do we measure it. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22:38–40. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2022.2044550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Crites JS, Cunningham TV. All healthcare ethics consultation services should meet shared quality standards. Am J Bioeth. 2022;22:69–72. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2022.2048741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]