PURPOSE:

Patients with cancer are at heightened risk of experiencing financial hardship. Financial navigation (FN) is an evidence-based approach for identifying and addressing patient and caregiver financial needs. In preparation for the implementation of a multisite FN intervention, we describe existing processes (ie, events and actions) and mechanisms (ie, how events work together) connecting patients to financial assistance, comparing rural and nonrural practices.

METHODS:

We conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with stakeholders (ie, administrators, providers, and staff) at each of the 10 oncology care sites across a single state (five rural and five nonrural practices). We developed process maps for each site and analyzed stakeholder perspectives using thematic analysis. After reporting findings back to stakeholders, we synthesized themes and process maps across rural and nonrural sites separately.

RESULTS:

Eighty-three stakeholders were interviewed. We identified six core elements of existing financial assistance processes across all sites: distress screening (including financial concerns), referrals, resource connection points, and pharmaceutical, insurance, and community/foundation resources. Processes differed by rurality; however, facilitators and barriers to identifying and addressing patient financial needs were consistent. Open communication between staff, providers, patients, and caregivers was a primary facilitator. Barriers included insufficient staff resources, challenges in routinely identifying needs, inadequate preparation of patients for anticipated medical costs, and limited tracking of resource availability and eligibility.

CONCLUSION:

This study identified a clear need for systematic implementation of oncology FN to equitably address patient and caregiver financial hardship. Results have informed our current efforts to implement a multisite FN intervention, which involves comprehensive financial toxicity screening and systematization of intake and referrals.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with cancer are at heightened risk of experiencing financial hardship, termed financial toxicity.1-3 Associated with worse health-related quality of life and, in extreme cases, heightened mortality,4-6 financial toxicity is a threat to decades of advancement in cancer care. In addition, financial toxicity is more commonly experienced by low-income patients, patients of color, and patients living in rural areas.1,7 Thus, addressing patients' financial needs is essential for providing high-quality, equitable, and timely care to achieve optimal outcomes.

Promising research has identified financial navigation (FN) as an evidence-based practice to reduce financial toxicity by detecting and addressing patient and caregiver financial needs.8-13 It is critical to understand how oncology practices currently address financial concerns to inform the adaptation and implementation of FN in diverse clinical contexts. Given differences between rural and nonrural health care settings (eg, patient volume and financial margins)14 and research suggesting that financial needs of rural patients may not be addressed as proactively as their urban counterparts,15 it is important to better understand differences in existing workflows.

Several previous studies have described the availability of systematic financial assistance processes at US cancer centers.15-18 However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to pair qualitative interviews with process mapping to understand site-specific financial assistance workflows from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. The objective of this study, therefore, was to use process mapping to prepare for the implementation of a multisite FN intervention. Process mapping aims to develop an explicit, visual representation of a stakeholders' understanding of a specific process, including the pathways, roles, and resources involved.19,20 We sought to describe the processes and mechanisms in place for providing financial assistance to patients and caregivers in oncology practices across North Carolina, comparing rural and nonrural sites. We defined processes as the series of events and actions involved in connecting patients to financial assistance resources and mechanisms as how these events work together with available resources to alleviate financial distress. We also sought to understand stakeholder perspectives on barriers and facilitators to addressing patient financial needs within current workflows and how these differ by geography.

METHODS

Study Setting, Sample, and Recruitment

We used process mapping in 10 oncology practices in North Carolina before implementing FN. Five sites were defined as rural on the basis of Rural-Urban Commuting Area codes. We recruited health system stakeholders involved in connecting patients to financial assistance via e-mail (average of three reminders). Stakeholders included administrators, clinicians, and support staff involved in connecting patients with financial assistance. Study staff originally interviewed Site Principal Investigators (PIs), who identified others involved in financial assistance through a snowball sampling approach. Of the 91 individuals approached, 83 completed an interview (91% response rate). Stakeholders were given a $50 in US dollars (USD) gift card for participation.

Data Collection

Two study team members (M.M. and M.G.) conducted 45- to 60-minute in-depth, semistructured interviews by phone or secure video-conferencing platform between February 2017 and April 2021 (see the interview guide in Appendix 1, online only). We interviewed consenting participants at each site until we reached thematic saturation. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and deidentified.

Analysis

Using Dedoose (version 9.0.15),21 we inductively developed a codebook through initial review of transcripts from one site; this codebook was iteratively refined over time. Six coders (C.B.B., V.P., M.M., M.G., N.P., and L.P.S.) coded three transcripts, discussing discrepancies and refining code definitions until reaching consensus. Coders divided and independently coded remaining transcripts. For each site, two coders (C.B.B. and V.P.) analyzed coded excerpts using thematic analysis to identify emergent themes and develop a process map documenting financial assistance workflows.22 We presented deidentified themes and maps back to the site PI, financial navigator, and other stakeholders invited by site PI at each site during a 1.5-hour videoconference. Report-backs highlighted the key individuals involved in connecting patients to financial assistance, challenges in the current workflow (eg, delays, insufficient screening, and limited staffing), and the complexity of existing referral pathways. We revised maps on the basis of stakeholder input.

After all site report-backs, we synthesized process maps across sites. The study team reviewed all finalized process maps, grouping rural and nonrural sites. We first identified common elements across all maps (eg, screening, referrals, and resources). We then noted similarities and differences within each element by site and compared rural and nonrural sites. Second, we synthesized stakeholder perspectives across sites by combining themes at the code level across all rural and nonrural sites. Two coders (C.B.B. and V.P.) iteratively identified overarching themes, grouping similar themes describing barriers and facilitators to connecting patients to financial assistance, and compared emergent themes between rural and nonrural sites. The institutional review board at UNC-CH deemed this study exempt (#20-3181).

RESULTS

Participant and Site Characteristics

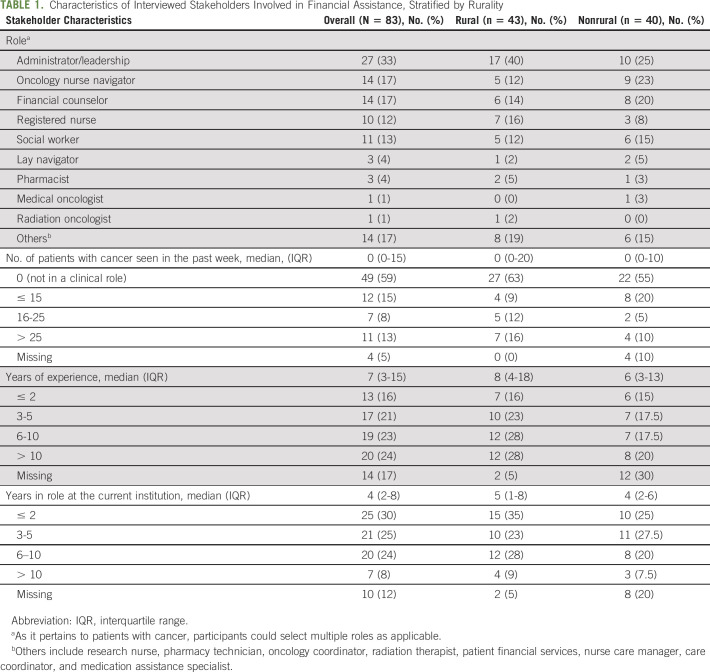

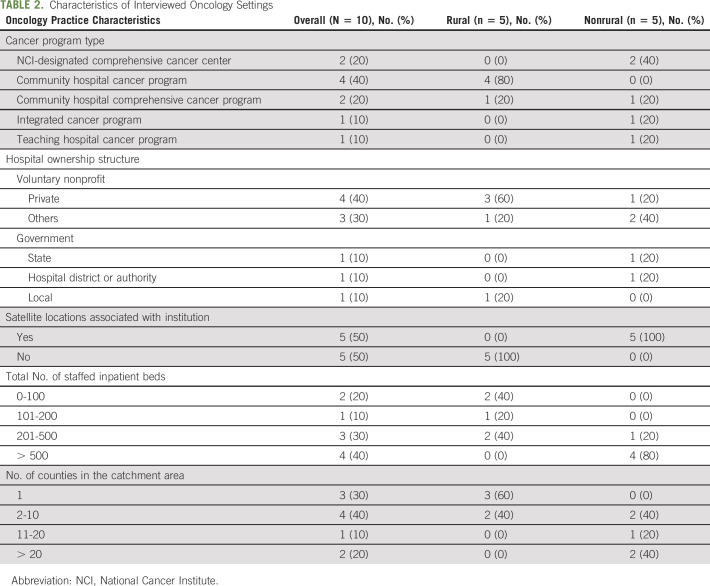

We conducted 78 interviews with 83 stakeholders across five rural and five nonrural sites (several interviews included two or three participants). Interviewees occupied both clinical (41%) and nonclinical (59%) roles and had a median of 7 years of experience (Table 1). Cancer center type, hospital ownership structure, and facility size varied by rurality (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Interviewed Stakeholders Involved in Financial Assistance, Stratified by Rurality

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of Interviewed Oncology Settings

Financial Assistance Process Mapping

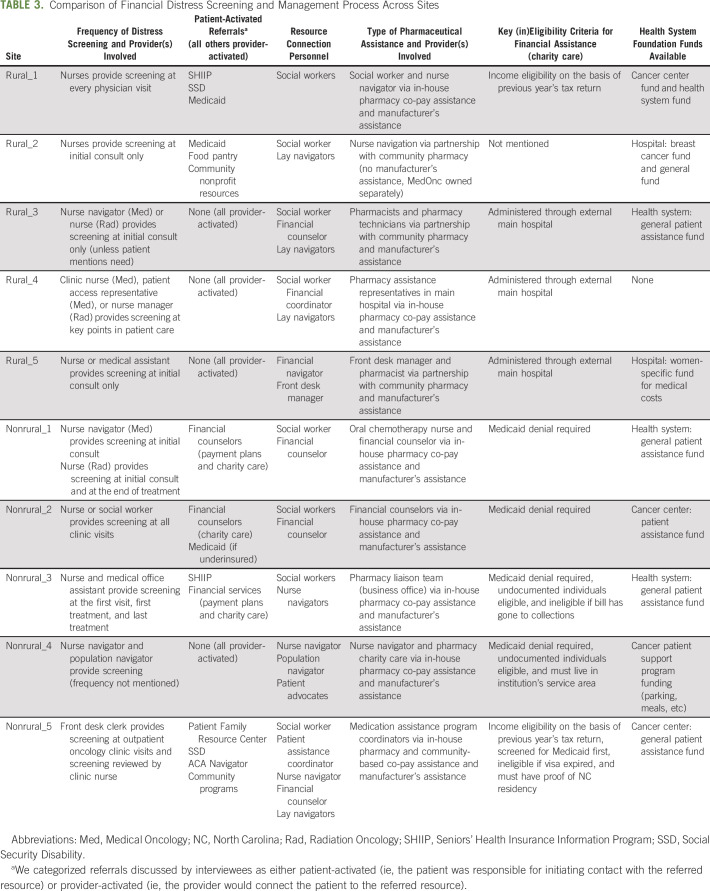

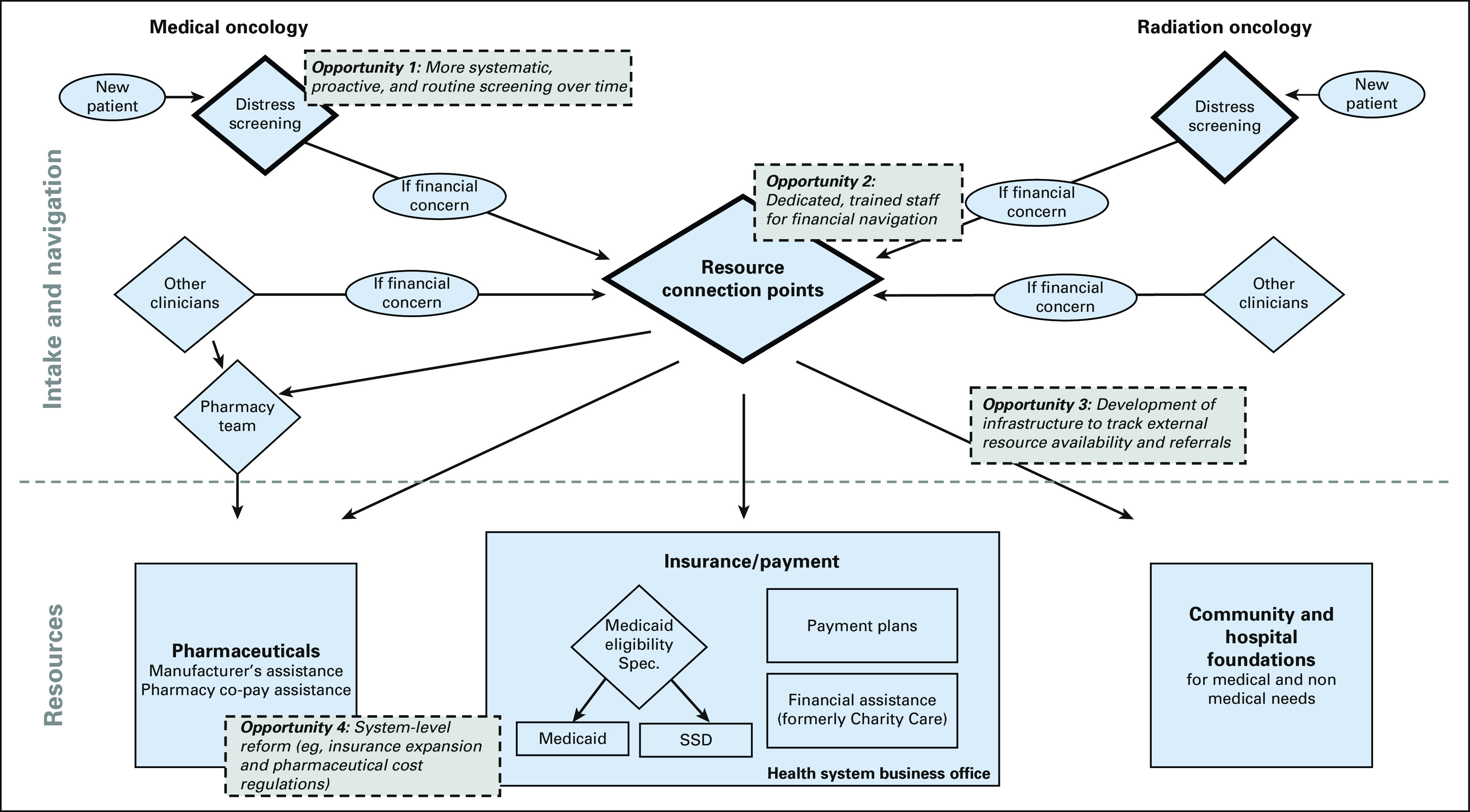

We identified six core elements of existing processes: distress screening (including financial concerns), referrals, resource connection points, and pharmaceutical, insurance, and community/foundation resources. Figure 1 presents a simplified process map documenting core elements across sites. Within each element, we describe commonalities and differences across all sites, followed by differences between rural and nonrural sites. Table 3 includes a description of each element by site.

FIG 1.

Overview of financial assistance workflows and opportunities for improvement. The figure presents a simplified, deidentified process map documenting how patients entering a cancer center for treatment are screened for financial distress and directed to resources for medical and nonmedical needs. Opportunities for improvement in existing workflows identified through the interviews and process mapping exercises are overlaid on existing processes. SSD, Social Security Disability.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of Financial Distress Screening and Management Process Across Sites

Distress Screening

To screen for financial distress, all sites used the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) distress thermometer and problem list,23 which includes practical problems such as insurance/financial and transportation. Most often, the distress thermometer was administered by a nurse, nurse navigator, or medical assistant. Administration frequency varied, ranging from once, at initial consult, to all key points in patient care. The site administering the distress screening at all key points noted the administrative burden associated with this frequency. Another site that only administered the screening at initial consult did so because patients viewed frequent screening as redundant.

Rural sites emphasized that, regardless of formal screening frequency, they constantly checked in with patients informally, enabled by the small size of their facility. “I'm always reassessing for distress and concerns and problems. …in the beginning, they may not have any need…but as they get going in the process, needs will pop up” (Social Worker, Rural_3). Nonrural sites expressed concern about patients falling through the cracks. As described by one interviewee, if a patient does not mention their financial need on the screener, “I think people just sort of assume that everything is okay and you keep marching on” (Nurse Navigator, Nonrural_3).

Referrals

We categorized referrals as either patient-activated (ie, the patient was responsible for initiating contact with the referred resource) or provider-activated (ie, the provider would connect the patient to the referred resource). Whether referrals were patient-activated or provider-activated, patients would first connect with a staff member involved in financial assistance (categorized as resource connection points, discussed below), who would then either recommend resources for patients to seek out on their own (patient-activated) or connect the patient to resources directly (provider-activated). The majority of referrals across all sites were provider-activated. Proactive, provider-activated referrals were viewed as an important way to prevent financial hardship from arising. “If we identify these things on the front end, then our patient is less likely to have a crisis in the middle of treatment because they've been carrying this burden” (Social Worker, Rural_4). Referrals to Medicaid and Social Security Disability (SSD) were most likely to be patient-activated.

Rural sites had less complex, more provider-activated referral pathways. Provider-activated referrals were noted as being particularly important in rural sites because of low patient health and technology literacy. Nonrural sites more commonly had patient-activated referrals to the hospital business office, which included financial assistance (charity care) and payment plan administration.

Resource Connection Points

Staff involved in financial assistance varied by site. Oncology social workers most commonly connected patients to nonmedical resources, and financial counselors addressed medical financial needs. Lay navigators and patient advocates were typically volunteer positions designed to help to fill in the gaps. Nurse navigators were also involved in financial assistance at some sites. “[We don't] necessarily have the answers, but we help find the answers through other people and other resources” (Nurse Navigator, Nonrural_5).

Rural sites had fewer people serving as connectors. However, nonrural site staff were responsible for a higher patient volume. “…they're all wearing so many different hats and there's only two social workers in this ginormous cancer center” (Clinical Nurse Specialist, Nonrural_3).

Pharmaceutical Resources

Sites used numerous strategies for connecting eligible patients to manufacturers' assistance programs (eg, internal databases and software). One site recognized the benefit of manufacturers' assistance but underscored that it was not a comprehensive solution: “…we've figured out how to get everybody free drug…that's not a solution, that's a Band-Aid” (Nurse Navigator, Nonrural_3).

Rural sites less commonly had an in-house pharmacy, but some partnered with community specialty pharmacies for co-pay assistance using hospital foundation funds. Two of the nonrural sites had pharmacy teams dedicated to manufacturers assistance.

Insurance Resources

Medicaid application assistance, financial assistance (or charity care), and payment plans were typically housed in the hospital business office, most often physically located outside of the cancer center. We observed differences across sites in financial assistance eligibility criteria (eg, residency and citizenship requirements) and application review times (ranging from two weeks to more than 100 days). Most sites used the previous year's tax returns to verify income, and sites varied in how broadly financial assistance was advertised. Hospital-based financial assistance was seen as a resource of last resort after exhausting other resources. Interviewees across sites expressed frustration with the administrative burden of Medicaid and SSD applications. "It's all just complicated…I think…a lot of people are denied disability because they've turned in a badly-completed application" (Patient Assistance Coordinator, Nonrural_5).

In rural sites, business offices were more commonly located in another county because of being a satellite site of a main hospital. This inhibited the ability of providers to assist patients with financial assistance applications and created confusion surrounding who was responsible for Medicaid and SSD application assistance.

Community and Foundation Resources

Community nonprofit agencies and hospital foundations were particularly important for covering nonmedical costs. However, staying current with resources and eligibility criteria was time-consuming. Hospital foundation funds were used to supplement needs after exhausting external resources. “We like to spend everybody else's money before we spend our own” (Administrator, Rural_3). Funds were distributed in wide-ranging amounts, typically with an annual cap (from $50 to $5,000 (USD) per year). One site used foundation funds to operate a food pantry within the cancer center. Overall, interviewees emphasized the constraints of foundation and community funds in relation to patient needs. “[It] doesn't nearly meet the need… if you're not able to work for three to six months … 500 bucks or even a maximum of a thousand dollars barely touches what you're going to need to get through that time” (Administrator, Nonrural_5).

Fewer resources were available in rural counties. As a result, rural sites relied more on internal foundations to meet patients' nonmedical needs. After a patient indicated a nonmedical financial need, one rural site interviewee said “But what do we do with it? Because I don't have any way to address this necessarily” (Nurse Manager, Rural_5).

Barriers and Facilitators to Connecting Patients to Financial Assistance

Interviews revealed stakeholder perspectives on barriers and facilitators to connecting patients to financial assistance within existing workflows. In comparing stakeholder attitudes between rural and nonrural sites, the most notable differences were related to the influence of facility size on communication. Interviewees from rural sites emphasized that their small size made multidirectional communication easier. “One of our strengths here is that we are such a small clinic that we know all the patients by name. We're constantly seeing them… I think a lot of our patients, if they need help with something, I think they feel comfortable coming to us for help” (Social Worker, Rural_2). By contrast, one nonrural site described the large size of their institution as a barrier to patient communication. Because social workers covered multiple sites, they were rarely able to meet with patients in person. This made it harder to connect and understand patient needs. Several nonrural sites also emphasized that their large size made communication among providers—about patients, available resources, and process changes— more challenging. “…part of the issue could be not working in silos…in such a big place like this one, [working in silos is] a challenge because [it] seems that…in some departments, they may be duplicating efforts…there should be more communication across departments” (Patient Navigator, Non-rural_4).

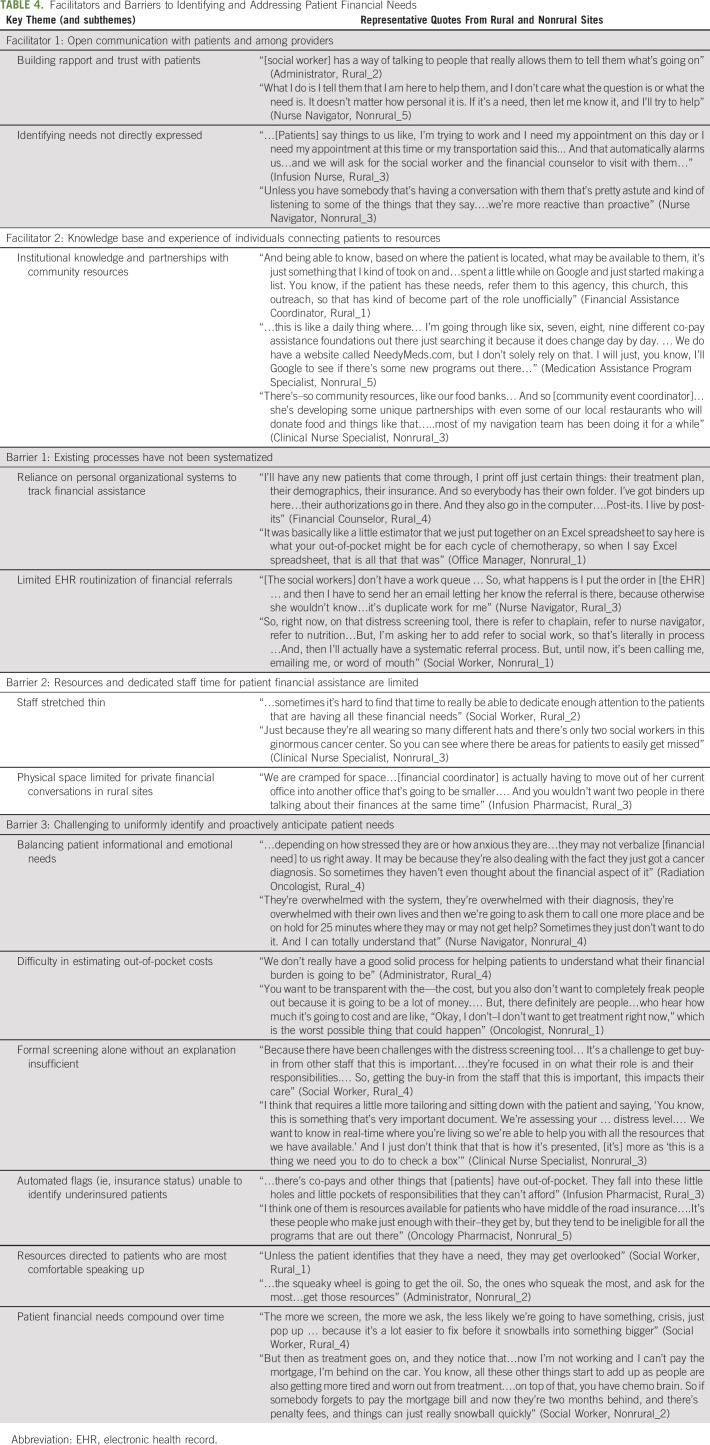

Otherwise, stakeholders across rural and nonrural sites described similar facilitators and barriers to addressing patient financial needs (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Facilitators and Barriers to Identifying and Addressing Patient Financial Needs

Facilitators

Stakeholders emphasized the importance of honesty and trust, both with patients and among providers, in identifying patients' financial needs and connecting them to assistance. Building rapport with patients was critical to enabling open communication. Stakeholders described the importance of detecting needs indirectly (described as reading between the lines) since patients did not always verbalize their needs.

An individual's institutional knowledge, developed through years of experience, was also a key facilitator to connecting patients to resources. Sharing curated lists of available resources, guides for how to complete complex applications, and relationships with community nonprofit organizations were invaluable. Unfortunately, this knowledge was not systematically captured and was often lost with staffing changes.

Barriers

Several barriers to connecting patients to financial assistance were identified. The lack of systematization in existing processes resulted in a reliance on idiosyncratic organizational systems to track financial assistance. Stakeholders described developing their own processes—using calendars, binders, and sticky notes—to track patients and the status of various applications. Stakeholders at the majority of sites expressed frustration that referrals for financial assistance had not been built into their electronic health record systems. Lacking dedicated staff time for patient financial assistance was also noted as a barrier, given that staff involved in financial assistance processes were commonly serving in multiple capacities. In larger health systems, expansion of clinical operations often resulted in the number of providers and patients outpacing support staff. The absence of space for private financial conversations was also noted as a barrier in several sites.

Numerous barriers were related to the challenges of anticipating and identifying financial needs. Stakeholders described needing to balance patient informational and emotional needs. Despite wanting to proactively prepare patients for the financial consequences of treatment, they recognized that patients were often not able to simultaneously process both health and financial distress. In addition, stakeholders described the challenge of accurately estimating patient out-of-pocket costs although some sites developed informal calculators. Many stakeholders felt that NCCN distress screening was insufficient, particularly when administered without explanation of the tool's importance. Stakeholders also noted limitations associated with electronic health record–triggered flags for the uninsured, which cannot identify underinsured patients. In addition, stakeholders recognized that patient financial needs often compounded and changed over time, rendering one-time screening at intake insufficient. Consequently, stakeholders felt that resources were directed to patients who were most comfortable speaking up.

DISCUSSION

Both rural and nonrural sites had existing institutional processes in place to connect patients and their caregivers to medical and nonmedical financial assistance. However, existing processes were limited by insufficient staff resources, challenges in identifying patient needs, and inadequate infrastructure to track external resource availability and referrals. Our findings add to those of previous studies of financial services in US cancer centers15,17,18 by documenting how oncology practices in diverse rural and nonrural settings screen for financial hardship and route patients to assistance.

Challenges with existing financial assistance processes identified in previous studies include a lack of cost transparency,16 patient reluctance to ask for help,16 inadequate staffing,15,18 and the need for better integration of financial advocacy into oncology practice.18 Each of these challenges was also identified by stakeholders across both rural and nonrural sites in our analysis, but rural sites felt that the smaller size of their facilities enabled them to better respond to patients' needs. In addition, stakeholders in our study described how the lack of cost transparency in routine oncology care and patient health and financial literacy limitations compounded the challenges of delivering assistance.

Our findings suggest several opportunities to improve current financial assistance processes through the implementation of FN (overlaid on current workflows in Fig 1). First, screening both proactively and comprehensively throughout treatment ensures equitable allocation of financial resources. Although distress screening is a critical component of high-quality oncology care,24 single checkboxes for patients to identify financial or insurance concerns are not sufficient to capture the full scope of patient financial needs,25,26 particularly if the screening tool is not administered routinely or with sufficient explanation. Although more work is needed to study the implementation of financial screening in clinical practice, the FN intervention will pair a validated patient-reported outcome measure of financial toxicity, the COST tool,27-29 with distress screening to increase the likelihood that patient financial concerns are systematically identified. Systematic screening should also help to address noted staffing shortages by triaging on the basis of the level of need, thus optimizing the time that navigators spend with patients and caregivers.

Second, FN will provide an infrastructure to support patient intake and referral tracking. This will streamline existing processes, document resources to which patients are successfully referred, and limit reliance on personal organization systems. Finally, FN involves building networks of financial navigators across cancer centers and connecting navigators to nonprofits with experience in navigation. This will facilitate knowledge sharing and support new navigators who lack institutional knowledge, a key facilitator to connecting patients to resources. FN is critical to addressing gaps and inefficiencies identified in financial assistance workflows. However, we must not overlook the importance of system-level reforms, such as insurance expansion and pharmaceutical cost regulations.30

Results should be viewed in the context of several limitations. First, the experiences and processes described were drawn from practices located within a single state, which is unlikely to reflect the full diversity of financial assistance processes elsewhere, particularly given state-level policy differences (eg, North Carolina has not expanded Medicaid). However, we purposefully recruited rural and nonrural, for-profit and non-profit practices and a diverse sample of stakeholders from a large, geographically, and socioeconomically diverse state. Second, we did not interview patients, despite patients being a key stakeholder in the financial assistance process. We plan to interview patients after FN implementation.

In conclusion, this study characterizes processes and mechanisms in place to identify and address patient financial needs from both rural and nonrural cancer sites. Barriers and facilitators identified by stakeholders illuminate the need for the systematic implementation of FN in diverse oncology settings to equitably address patient financial hardship.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful to all the individuals who participated in this study. We would also like to thank Cindy Rogers and Julia Rodriguez-O’Donnell for their substantial contributions to the formative work for this project.

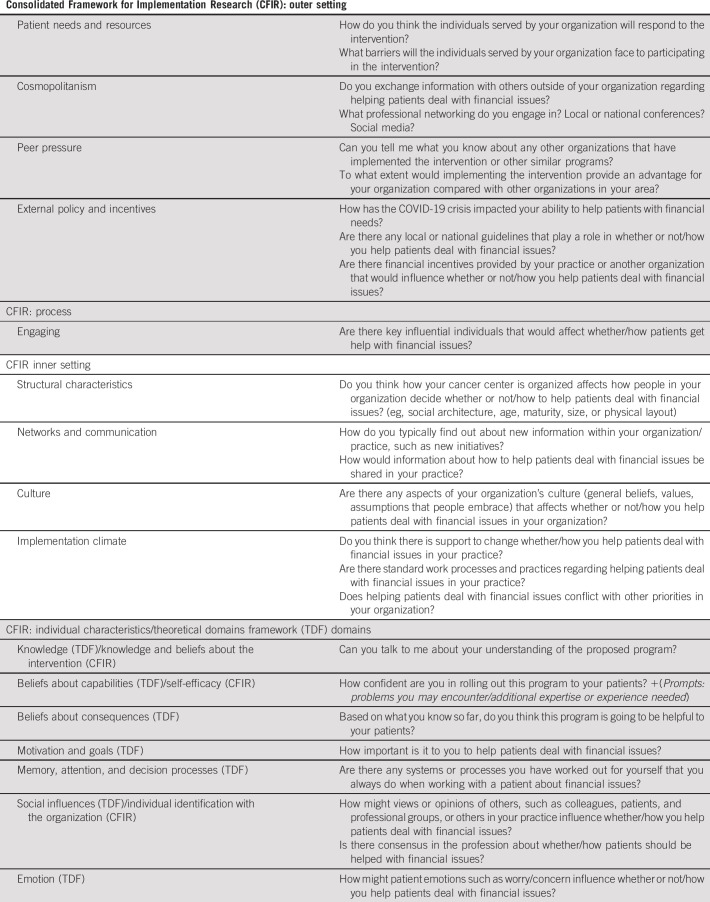

APPENDIX 1. Key Stakeholder Semistructured Interview Guide

Introduction:

Thank you for your interest in this study. Thank you so much for completing the online survey we sent prior to this interview. The aim of this interview is to help us understand how your practice responds to patients with financial problems. Your responses to both the survey and the interview will help us understand how to improve cancer programs' ability to respond to patients with financial problems moving forward.

We expect that our discussion will last about 45 minutes to an hour. Are you in a place where you feel comfortable and like you can speak freely, ie, in an office with a door that closes? Everything you tell us will remain confidential and will only be reported as part of a bigger group, without your name attached to it. Before we begin, I would like to ask your permission to audio record our discussion (for research and training purposes). Would it be OK with you if I record this interview? (If participant refuses to be audio-recorded, the project coordinator will take notes instead) The interview will be turned into written notes, but your name or any identifying details will not be associated with any of the notes. The audio recordings will be erased once the project is complete.

Do you have any questions before we begin?

If you have any questions, please reach out to the study staff or the Principal Investigator for this study.

1. Role in the organization

2. I'd like to start by asking you what might happen if I were a patient in your cancer program, and I asked for help with finances related to my cancer treatment.

Depending on the extent to which the interviewee responds to the question above and gives a clear sense of the context of the cancer program as it relates to financial counseling, including determinants of whether and how services are offered, you may also choose to ask the following questions:

Prompts:

a. What happens when a patient mentions having trouble paying for personal expenses (eg, rent, electricity, gas) due to the costs of their treatment?

3. What would happen if I were a patient in your cancer program, and I needed help with my finances related to my cancer treatment, but I didn't ask anyone for help?

Prompts:

a. Are all patients asked about their financial assistance needs? Who is responsible for asking patients about their financial assistance needs?

b. What happens when a patient is having trouble paying for personal expenses (eg, rent, electricity, gas) due to the costs of their treatment?

4. Now, I'd like to discuss potential barriers and facilitators to implementing a specific program to help patients deal with their financial issues in your organization.

The financial navigation program consists of (1) identification of cancer patients at high risk for or currently experiencing financial difficulties related to their cancer treatment; (2) connecting these patients to a dedicated oncology financial navigator in your organization (supported by a UNC grant in this context), who will use a comprehensive assessment tool to determine financial needs and one-on-one appointments to direct patients to specific financial support resources and assist with applications; and (3) routine tracking and monitoring of patients' financial and health outcomes. The patients referred to a financial navigator will have at least two visits with the navigator with some patients receiving more intensive, needs-dependent support.

Could you please talk about how implementing an intervention like this in your organization might work? Are there things that would facilitate the intervention's implementation? What about things that might make implementing the intervention challenging?

Prompts

Thank you so much for talking with us. We would like to get the perspectives of 5-10 people within your organization, who else do you think we should interview within your organization?

Lisa P. Spees

Research Funding: AstraZeneca/Merck

Donald L. Rosenstein

Research Funding: NCCN/Pfizer (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Oxford University Press: royalties from book sales of The Group: Seven Widowed Fathers Reimagine Life; UptoDate: royalties from chapters in the palliative care section

Mindy Gellin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sensal Health

Cleo A. Samuel-Ryals

Employment: Flatiron Health

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Flatiron Health

Katherine Reeder-Hayes

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Stephanie B. Wheeler

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

DISCLAIMER

Funders did not have any role in the study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented at 14th Annual Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health, December 14-16, 2021, Virtual.

SUPPORT

Supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH; 1-R01-CA240092-02, 3-P30-CA016086-44-S4, PI: Wheeler and Rosenstein). Additional funding for this project was provided by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and Pfizer Independent Grants for Learning & Change (PI: Wheeler and Rosenstein). C.B.B. was additionally supported by a NCI Cancer Care Quality Training Program grant, UNC-CH, Grant No. T32-CA-116339, for which SBW is a mentor and PI. V.P. was funded by the Cancer Prevention and Control Education Program (T32CA057726-27).

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the need to protect the privacy of the individuals who participated in the study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Financial support: Donald L. Rosenstein, Stephanie B. Wheeler

Administrative support: Michelle Manning, Mindy Gellin, Neda Padilla

Provision of study materials or patients: Ronny A. Bell, Carla Strom, Phyllis A. DeAntonio, Tiffany H. Young, Sherry King, Brian Leutner, Derek Vestal

Collection and assembly of data: Caitlin B. Biddell, Lisa P. Spees, Victoria Petermann, Michelle Manning, Mindy Gellin, Neda Padilla

Data analysis and interpretation: Caitlin B. Biddell, Lisa P. Spees, Victoria Petermann, Michelle Manning, Mindy Gellin, Neda Padilla, Kendrel Cabarrus

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Financial Assistance Processes and Mechanisms in Rural and Nonrural Oncology Care Settings

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Lisa P. Spees

Research Funding: AstraZeneca/Merck

Donald L. Rosenstein

Research Funding: NCCN/Pfizer (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Oxford University Press: royalties from book sales of The Group: Seven Widowed Fathers Reimagine Life; UptoDate: royalties from chapters in the palliative care section

Mindy Gellin

Consulting or Advisory Role: Sensal Health

Cleo A. Samuel-Ryals

Employment: Flatiron Health

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Flatiron Health

Katherine Reeder-Hayes

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Stephanie B. Wheeler

Research Funding: Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Pfizer

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Han X, Zhao J, Zheng Z, et al. Medical financial hardship intensity and financial sacrifice associated with cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:308–317. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zheng Z, Jemal A, Han X, et al. Medical financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer. 2019;125:1737–1747. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gordon LG, Merollini KMD, Lowe A, et al. A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: We can't pay the co-pay. Patient. 2017;10:295–309. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith GL, Lopez-Olivo MA, Advani PG, et al. Financial burdens of cancer treatment: A systematic review of risk factors and outcomes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019;17:1184–1192. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.7305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, et al. Population-based assessment of cancer survivors' financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:145–150. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zahnd WE, Davis MM, Rotter JS, et al. Rural-urban differences in financial burden among cancer survivors: An analysis of a nationally representative survey. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:4779–4786. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04742-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shankaran V, Leahy T, Steelquist J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program. JCO Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e122–e129. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.024927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sadigh G, Gallagher K, Obenchain J, et al. Pilot feasibility study of an oncology financial navigation program in brain cancer patients. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16:1420–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yezefski T, Steelquist J, Watabayashi K, et al. Impact of trained oncology financial navigators on patient out-of-pocket spending. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24(5 suppl):S74–s79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doherty MJ, Thom B, Gany F. Evidence of the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of oncology financial navigation: A scoping review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30:1778–1784. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wheeler SB, Rodriguez O, Donnell J, et al. Reducing cancer-related financial toxicity through financial navigation: Results from a pilot intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:694. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sherman D, Fessele KL. Financial support models: A case for use of financial navigators in the oncology setting. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2019;23:14–18. doi: 10.1188/19.CJON.S2.14-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaufman BG, Thomas SR, Randolph RK, et al. The rising rate of rural hospital closures. J Rural Health. 2016;32:35–43. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Petermann V, Zahnd WE, Vanderpool RC, et al. How cancer programs identify and address the financial burdens of rural cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2021;30:2047–2058. doi: 10.1007/s00520-021-06577-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. de Moor JS, Mollica M, Sampson A, et al. Delivery of financial navigation services within National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2021;5:pkab033. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkab033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McLouth LE, Nightingale CL, Dressler EV, et al. Current practices for screening and addressing financial hardship within the NCI Community Oncology Research Program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30:669–675. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-20-1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khera N, Sugalski J, Krause D, et al. Current practices for screening and management of financial distress at NCCN member institutions. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18:825–831. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2020.7538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Antonacci G, Reed JE, Lennox L, et al. The use of process mapping in healthcare quality improvement projects. Health Serv Manage Res. 2018;31:74–84. doi: 10.1177/0951484818770411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kononowech J, Landis-Lewis Z, Carpenter J, et al. Visual process maps to support implementation efforts: A case example. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:105. doi: 10.1186/s43058-020-00094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dedoose Version 9.0.15, Web Application for Managing, Analyzing, and Presenting Qualitative and Mixed Method Research Data [computer program] Los Angeles, CA: Sociocultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Thermometer and Problem List for Patients. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; https://www.nccn.org/docs/default-source/patient-resources/nccn_distress_thermometer.pdf?sfvrsn=ef1df1a2_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tavernier SS. Translating research on the distress thermometer into practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18(suppl):26–30. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.S1.26-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ehlers SL, Davis K, Bluethmann SM, et al. Screening for psychosocial distress among patients with cancer: Implications for clinical practice, healthcare policy, and dissemination to enhance cancer survivorship. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9:282–291. doi: 10.1093/tbm/iby123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jacobsen PB, Norton WE. The role of implementation science in improving distress assessment and management in oncology: A commentary on "screening for psychosocial distress among patients with cancer: Implications for clinical practice, healthcare policy, and dissemination to enhance cancer survivorship.”. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9:292–295. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Souza JA, Yap B, Ratain MJ, et al. User beware: We need more science and less art when measuring financial toxicity in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1414–1415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Hlubocky FJ, et al. The development of a financial toxicity patient-reported outcome in cancer: The COST measure. Cancer. 2014;120:3245–3253. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Souza JA, Yap BJ, Wroblewski K, et al. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: The validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) Cancer. 2017;123:476–484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yabroff KR, Bradley C, Shih YT. Understanding financial hardship among cancer survivors in the United States: Strategies for prevention and mitigation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:292–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the need to protect the privacy of the individuals who participated in the study.