PURPOSE:

Regulatory agencies have sought to speed up the review of new cancer medicines and reduce delays in approval between countries. We examined trends in regulatory review times and association with clinical benefit for new cancer medicines in six jurisdictions: United States (Food and Drug Administration [FDA]), European Union (European Medicines Agency [EMA]), Switzerland (Swissmedic), Japan (Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency [PMDA]), Canada (Health Canada), and Australia (Therapeutic Goods Administration).

METHODS:

We studied all new cancer drugs approved in the six aforementioned jurisdictions from 2007 to 2020. We extracted all applicable expedited programs, total regulatory review times, and, for drugs first approved by the FDA, times to subsequent regulatory approval. Clinical benefit was assessed using the European Society for Medical Oncology-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale value framework and ASCO-Cancer Research Committee's targets. Nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare total review times for high versus low clinical benefit drugs.

RESULTS:

One hundred and twenty eight drugs received initial approval in at least one of the six included jurisdictions. Most drugs approved by the FDA (91%) and Health Canada (59%) qualified for at least one expedited program within those jurisdictions, compared with 46% of EMA approvals and 18% of PMDA approvals. The FDA was the first regulator to approve 102 (80%) drugs. Delays in submission accounted for a median of 20.2% (EMA) to 83.8% (PMDA) of the time to subsequent approval. There was no association between high clinical benefit and shorter total review times.

CONCLUSION:

Most new cancer therapies were approved first by the FDA, and delays in submission of regulatory applications accounted for substantial delays in approving cancer drugs in other countries. Regulators should prioritize faster review for drugs with high clinical benefit.

INTRODUCTION

Regulatory agencies around the world have increasingly sought to speed up the development and approval of new medicines. Notably, since 2012, regulators in the United States (Food and Drug Administration [FDA]), Europe (European Medicines Agency [EMA]), Japan (Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency [PMDA]), Switzerland (Swissmedic), and Australia (Therapeutic Goods Administration [TGA]) have established new expedited programs. These expedited programs, as well as existing regulatory pathways, are frequently used to facilitate the approval of cancer therapies.1,2 For example, in 2019, all cancer drugs approved by the FDA qualified for at least one expedited program.3

Nevertheless, regulatory agencies continue to face pressure to accelerate new drug approvals4-6 and reduce delays in approval when drugs are approved first in a comparable country.7 In 2019, the FDA announced plans (Project Orbis) for concurrent submission and review of oncology products with regulators in Canada and Australia; this initiative was expanded in 2020 to include Switzerland and Singapore.8 In October 2020, the United Kingdom announced plans to join a consortium of drug regulatory agencies to jointly review certain new medicines with its exit from the European Union (EU).9 Ideally, both international initiatives and individual regulators' expedited programs would prioritize cancer therapies providing clinically meaningful benefits. Widely used value frameworks include the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO)-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (MCBS)10 and the ASCO's Cancer Research Committee (ASCO-CRC) targets.11

Given substantial changes in the regulatory landscape in recent years, we aimed to assess trends in total regulatory review times for new cancer medicines in six jurisdictions: United States (FDA), EU (EMA), Switzerland (Swissmedic), Japan (PMDA), Canada (Health Canada), and Australia (TGA). We also evaluated the association between clinical benefit and times to approval and use of expedited programs.

METHODS

We identified new cancer drugs approved by the FDA (United States), EMA (EU), Swissmedic (Switzerland), PMDA (Japan), Health Canada (Canada), and TGA (Australia) from January 2007 to May 2020 using publicly available registers of drug approvals available for each regulatory agency. The study period was chosen to include key expedited programs that have been established by regulators, including EMA's conditional marketing authorization in 2006 and the FDA's breakthrough therapy designation in 2012. For each drug, we used the ingredient (generic) name to determine whether it had been approved by any of the other regulators. We included drugs for solid tumors and hematologic malignancies, and focused on the first approved indication, which corresponds to initial market availability of these therapies.

Data Extraction

To assess the regulatory characteristics of the included drug approvals, for each drug, we extracted the dates of regulatory application submission and approval, indication, cancer type, and expedited program. Dates of regulatory approval were available from all six regulators; dates of regulatory application submission were available for the FDA, EMA, PMDA, and Health Canada for the entire study period and for TGA after 2014, but not for Swissmedic. Information on expedited program and approval type (Appendix Table A1, online only) were publicly available from FDA (priority review, accelerated approval fast track, breakthrough therapy designation, and real-time oncology review pilot), EMA (accelerated assessment, conditional marketing authorization, and priority medicines scheme), PMDA (priority review, conditional approval, and sakigake designation), Swissmedic (temporary authorization), Health Canada (priority review and Notice of Compliance with Conditions), and TGA (priority review and provisional approval). Among these, the expedited programs with shorter targets for regulatory review times were FDA's priority review (6 months), EMA's accelerated assessment (150 days), PMDA's priority review (9 months) and sakigake (6 months), Health Canada's priority review (180 days), and TGA's priority review (150 days). All data for the study period were updated in December 2021.

We reviewed regulatory review dossiers or, if unavailable, product labeling for data on the pivotal trials supporting approval of the included drugs. For solid tumor drugs, clinical benefit was assessed using the ESMO-MCBS version 1.1 scale10 and targets for clinically meaningful benefit developed by working groups of ASCO-CRC (limited to randomized controlled trials).11 Consistent with prior studies1,12-16 as well as developers of these frameworks,17 high clinical benefit was defined as ESMO-MCBS scores of 4-5 (in palliative settings) or A-B (in adjuvant or neoadjuvant therapy settings), and overall survival gains > 2.5 months or progression-free survival gain > 3 months.11,18

Statistical Analysis

For jurisdictions with available data (all except Swissmedic), we calculated total regulatory review times, defined as the time from submission to regulatory approval. We assessed differences in total review times and submission dates between jurisdictions. For drugs first approved by the FDA, we evaluated times to subsequent regulatory approval by one of the other included regulators and the proportion of these times accounted for by later submission to other regulators (ie, delays in submission of regulatory applications).

To evaluate the association between regulatory review times and clinical benefit, we used the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test to compare total review times for high versus low benefit drugs. We then fit separate Cox regression models to assess the association between clinical benefit and times to subsequent regulatory approval for drugs first approved by the FDA.

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Two-tailed P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Institutional review board approval was not required because all data were publicly available.

RESULTS

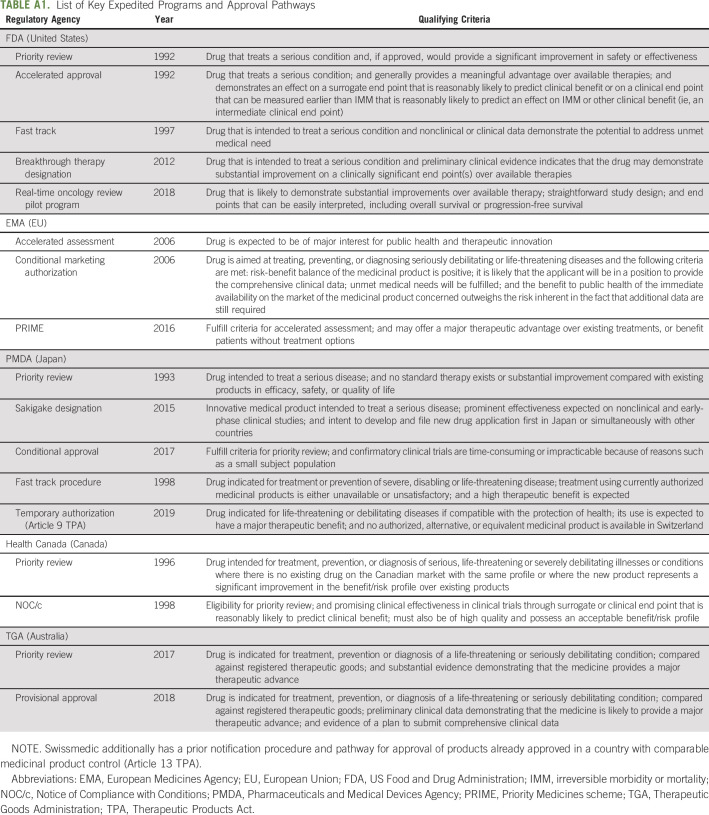

Between January 2007 and May 2020, 128 cancer drugs received initial regulatory approval in at least one of the six included jurisdictions (Table 1, Appendix Table A2, online only). Seventy-seven (60%) of the 128 included drugs were approved for solid tumors. As of May 2020, 58 (45%) drugs were approved by all six regulators; 26 (20%) were approved in only one jurisdiction. The FDA approved 117 (91%) drugs, the EMA 94 (73%), Swissmedic 84 (66%), PMDA 75 (59%), Health Canada 88 (69%), and the TGA 84 (66%). The FDA was the first regulator to approve 102 (80%) drugs, compared with 10 (8%) drugs approved first by EMA, three (2%) by Swissmedic, 11 (9%) by PMDA, and two (2%) by TGA; no drugs were first approved by Health Canada.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of New Cancer Drugs Approved by the FDA, EMA, Swissmedic, PMDA, Health Canada, and TGA, January 2007-May 2020

Regulatory Review and Expedited Programs

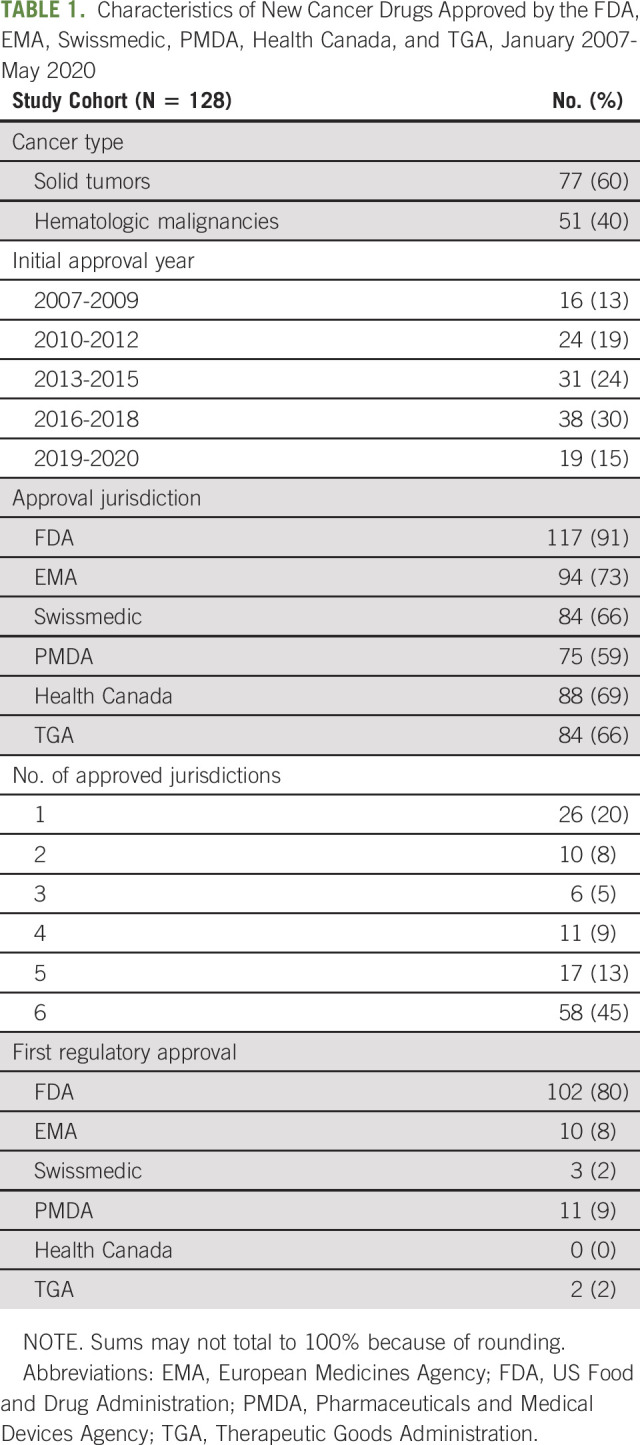

Overall, most cancer drugs approved by the FDA (91%) and Health Canada (59%) qualified for at least one expedited program within those jurisdictions (Table 2). By contrast, only 46% of EMA approvals and 18% of PMDA approvals qualified for an expedited program within those jurisdictions. Most (82%) cancer drugs approved by the FDA received priority review, compared with 17% of EMA approvals (accelerated assessment), 16% of PMDA approvals (priority review and sakigake), 28% of Health Canada approvals, and 12% of TGA approvals (after creation of the program in July 2017).

TABLE 2.

Expedited Programs and Total Regulatory Review Times by Jurisdictiona

Time to Subsequent Regulatory Approval

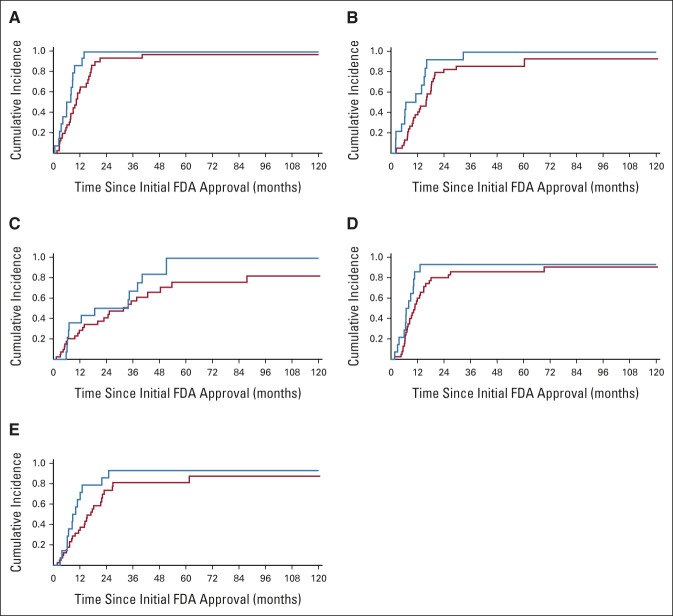

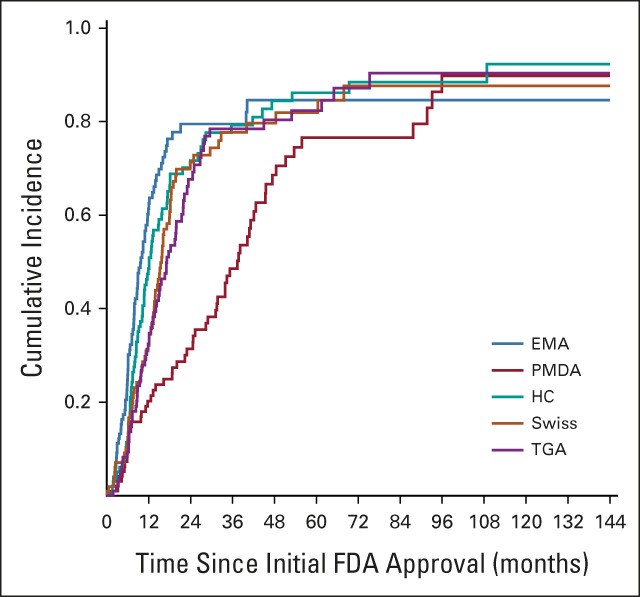

As of May 2020, among the 102 drugs first approved by FDA, the median time to subsequent approval by EMA was 9.7 months (95% CI, 7.9 to 11.7), 15.7 months (95% CI, 13.6 to 18.0) for Swissmedic, 37.4 months for PMDA (95% CI, 31.2 to 42.7), 12.2 months for Health Canada (95% CI, 10.2 to 15.7), and 17.1 months for TGA (95% CI, 13.7 to 21.8; Fig 1).

FIG 1.

Time to subsequent regulatory approval for cancer drugs in other countries first approved by the FDA. EMA, European Medicines Agency (European Union); FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; HC, Health Canada (Canada); PMDA, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (Japan); Swiss, Swissmedic; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration (Australia).

Delays in submission accounted for a median of 20.2% (interquartile range [IQR], 4.3%-32.9%) of the time to subsequent approval by EMA, 44.2% (IQR, 29.7%-77.9%) of time to approval by TGA, 60.9% (IQR, 44.9%-81.4%) of time to approval by Health Canada, and 83.8% of time to approval by PMDA (IQR, 65.8%-96.4%).

Association With Clinical Benefit

Sixteen of 74 (22%) solid tumor drugs were rated as high clinical benefit as assessed with ESMO-MCBS. Drugs considered high clinical benefit according to ESMO-MCBS were associated with shorter total regulatory review times for Health Canada (–1.90 months; 95% CI, –0.18 to –3.61 months; P = .03). However, there was no association between clinical benefit and total review times for FDA (P = .90), EMA (P = .32), PMDA (P = .83), and TGA (P = .57).

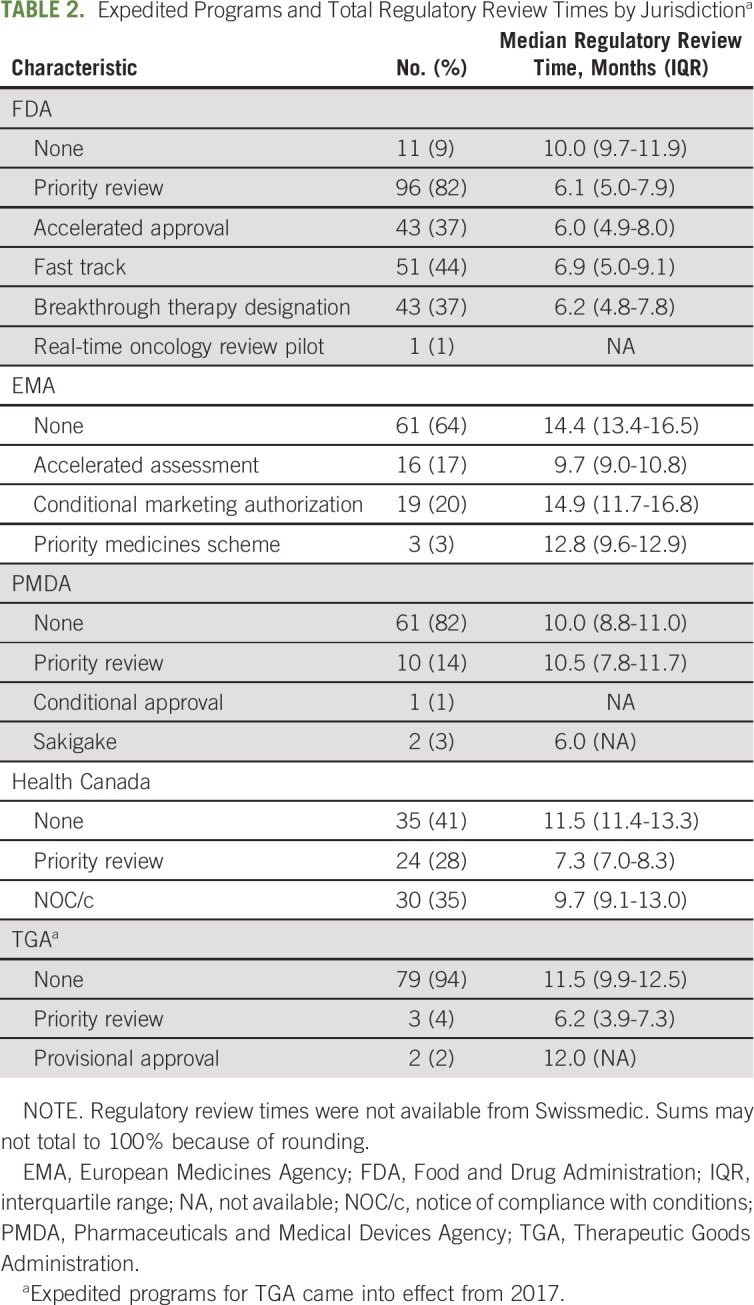

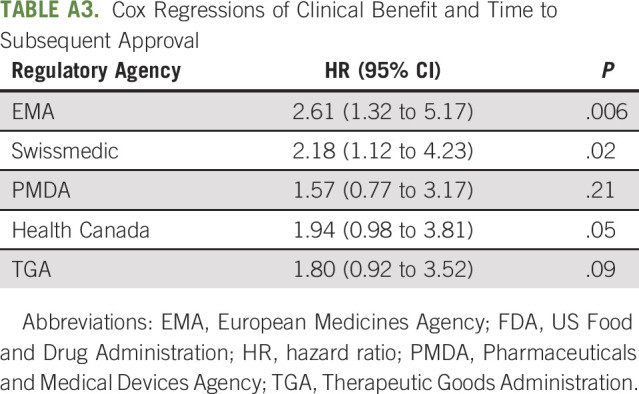

In Cox regression models for each jurisdiction, high-benefit drugs were associated with decreased times to subsequent approval by EMA (6.0 v 10.4 months; hazard ratio, 2.61; 95% CI, 1.32 to 5.17; P = .006) and Swissmedic (6.7 v 15.9 months; hazard ratio, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.12 to 4.23; P = .02; Fig 2, Appendix Table A3, online only). The association between clinical benefit and time to subsequent approval was not significant for PMDA (18.7 v 31.7 months; P = .21), Health Canada (6.9 v 10.8 months; P = .05), and TGA (8.8 v 17.0 months; P = .09).

FIG 2.

Association between time to subsequent regulatory approval and clinical benefit according to ESMO-MCBS: (A) EMA, (B) Swissmedic, (C) PMDA, (D) Health Canada, and (E) TGA. High clinical benefit is shown in blue; low clinical benefit is shown in red. EMA, European Medicines Agency; ESMO-MCBS, European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; PMDA, Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency; TGA, Therapeutic Goods Administration.

Only 38 drugs could be assessed with ASCO-CRC (randomized controlled trials), of which 28 (74%) were categorized as providing high clinical benefit. No expedited programs were associated with high clinical benefit according to ASCO-CRC. There was no association between clinical benefit according to ASCO-CRC and total review times or time to subsequent approval by any regulatory agency.

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of regulatory review times and clinical benefit for cancer drugs approved by six major regulatory agencies since 2007, we found that most new cancer therapies were approved first by the FDA and qualified for one of FDA's expedited programs. For drugs approved first by the FDA, the median time to subsequent approval ranged from 9.7 months for Europe (EMA) to 37.4 months for Japan (PMDA). Delays in submission of regulatory applications accounted for 20% (EMA), 44% (TGA), 61% (Health Canada), and 84% (PMDA) of these times to subsequent approval.

Our findings that delays in regulatory submission to regulators other than the FDA and EMA account for a substantial fraction of delays in approving new cancer drugs in those countries provide support for coordinating joint submission and review of new drug applications. Such initiatives are currently underway. In 2018, Australia, Canada, Switzerland, and Singapore announced plans to jointly review and approve new medicines through a New Chemical Entities Work Sharing Initiative.19 The first products approved by this consortium were cancer therapies, namely, apalutamide (prostate cancer), abemaciclib (breast cancer), and niraparib (ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancers). In 2019, Switzerland established a pathway for temporary approval of drugs already approved in comparable countries20; this pathway was used to accelerate the availability of larotrectinib (tumors with NTRK gene fusion) and cemiplimab (cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma). In 2020, tucatinib, indicated for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive breast cancer, was the first new drug approved through Project Orbis21: FDA approval was granted in April 2020, with subsequent approval by Swissmedic issued in 19 days (May 2020) and by Health Canada in 49 days (June 2020).

In addition to international regulatory collaboration, regulatory agencies have established expedited programs, which have resulted in shorter regulatory review times for qualifying products. We found that the application of these expedited programs varied between countries. Although the FDA granted priority review to 82% of cancer drugs, only 12%-28% of drugs approved by EMA, PMDA, Health Canada, or TGA qualified for faster regulatory review through comparable programs. We also found little evidence that expedited programs successfully prioritized drugs with high clinical benefit, including notably the breakthrough therapy program in the United States. These findings may reflect uncertainty or lack of systematic definition of the level of benefit expected for drugs qualifying for faster clinical development or regulatory review. Aligning reviews with health technology assessment agencies, such as in Canada and in the EU, and using a validated value framework, such as ESMO's MCBS, may help raise the bar for expedited programs in general so that regulators can deploy limited time and resources most efficiently. Strengthening the standards for expedited programs is also important for patients and clinicians, given the signaling effect that such programs may have,22 the need for patient-relevant outcomes data to guide treatment decisions, and the possible safety risks associated with drugs approved through expedited programs in general.23-25

This study has limitations. First, we focused on approved products and assessed differences in regulatory review times between jurisdictions. Some variation in times to approval may be accounted for by factors other than application submission or regulatory review alone. For example, manufacturers may need to conduct additional trials enrolling local participants. Second, there were limited data for several expedited programs, such as PMDA's sakigake program and TGA's priority review, which were only recently established. Third, consistent with prior studies,26-29 total regulatory review time was defined as the total time between drug application submission and date of approval. This period includes time elapsed (including regulatory clock-stops) as the manufacturer submits updated data or application amendments, responds to questions from the regulator, or corrects other components of the overall application (eg, manufacturing issues)—which may not be directly within the regulator's control. Finally, clinical benefit was assessed on the basis of the data available at approval, since this represents the data used to justify inclusion in expedited programs. It is possible that assessments of clinical benefit could change as more evidence becomes available after approval.

In conclusion, this study found substantial variation in regulatory review times for cancer drugs by major regulatory agencies around the world. Review times were fastest in the United States, mainly because virtually all cancer drugs approved by the FDA qualified for one or more expedited programs. For regulators other than the FDA and EMA, delays in submission of regulatory applications by manufacturers accounted for a significant portion of the time to subsequent approval. Although some drugs with expedited approval provided substantial clinical benefit, regulators could use value frameworks such as ESMO-MCBS to better prioritize faster review for drugs with high clinical benefit.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

List of Key Expedited Programs and Approval Pathways

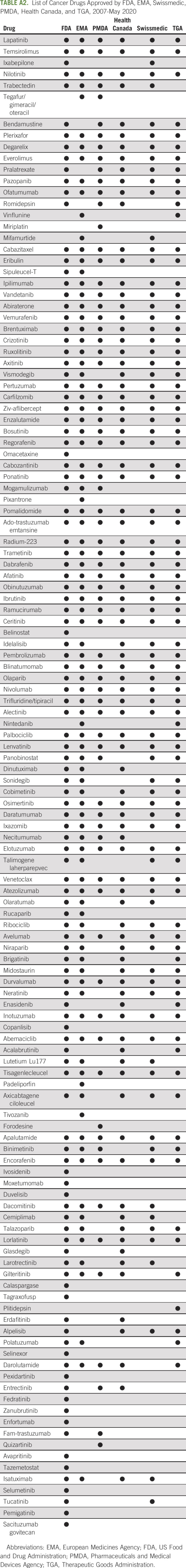

TABLE A2.

List of Cancer Drugs Approved by FDA, EMA, Swissmedic, PMDA, Health Canada, and TGA, 2007-May 2020

TABLE A3.

Cox Regressions of Clinical Benefit and Time to Subsequent Approval

Aaron S. Kesselheim

Expert Testimony: Blank Rome

Ariadna Tibau

Honoraria: Novartis, Lilly

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported by the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation, Swiss National Science Foundation (PCEGP1_194607), and Kaiser Permanente Institute for Health Policy. Dr. Kesselheim and Mr. Lee were additionally supported by Arnold Ventures.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Thomas J. Hwang, Aaron S. Kesselheim, Kerstin N. Vokinger

Financial support: Thomas J. Hwang, Aaron S. Kesselheim, Kerstin N. Vokinger

Administrative support: Thomas J. Hwang, Kerstin N. Vokinger

Provision of study materials or patients: Ariadna Tibau

Collection and assembly of data: Thomas J. Hwang, Ariadna Tibau, ChangWon C. Lee

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Clinical Benefit and Expedited Approval of Cancer Drugs in the United States, European Union, Switzerland, Japan, Canada, and Australia

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Aaron S. Kesselheim

Expert Testimony: Blank Rome

Ariadna Tibau

Honoraria: Novartis, Lilly

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hwang TJ, Franklin JM, Chen CT, et al. : Efficacy, safety, and regulatory approval of Food and Drug Administration-designated breakthrough and nonbreakthrough cancer medicines. J Clin Oncol 36:1805-1812, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molto C, Hwang TJ, Borrell M, et al. : Clinical benefit and cost of breakthrough cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. Cancer 126:4390-4399, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Food and Drug Administration : New Drug Therapy Approvals. FDA, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/media/134493/download [Google Scholar]

- 4.The White House : Joint Address to Congress, 2017. www.whitehouse.gov/joint-address [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parliament of Australia, Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs : Availability of New, Innovative and Specialist Cancer Drugs in Australia, 2017. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Community_Affairs/Cancer_Drugs [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gyawali B, Hwang TJ, Vokinger KN, et al. : Patient-centered cancer drug development: Clinical trials, regulatory approval, and value assessment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 39:374-387, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondo T: Future Plan of PMDA for the Next Five Years, 2014. https://ec.europa.eu/futurium/en/system/files/ged/future_plan_of_pmda_japan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Food and Drug Administration : Project Orbis. FDA, 2019. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/oncology-center-excellence/project-orbis [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency : UK Medicines Regulator Joins up With Australia, Canada, Singapore and Switzerland Regulators, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-medicines-regulator-joins-up-with-australia-canada-singapore-and-switzerland-regulators [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherny NI, Dafni U, Bogaerts J, et al. : ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1. Ann Oncol 28:2340-2366, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis LM, Bernstein DS, Voest EE, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology perspective: Raising the bar for clinical trials by defining clinically meaningful outcomes. J Clin Oncol 32:1277-1280, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tibau A, Molto C, Borrell M, et al. : Magnitude of clinical benefit of cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration based on single-arm trials. JAMA Oncol 4:1610-1611, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tibau A, Molto C, Ocana A, et al. : Magnitude of clinical benefit of cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration. J Natl Cancer Inst 110:486-492, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Del Paggio JC, Sullivan R, Schrag D, et al. : Delivery of meaningful cancer care: A retrospective cohort study assessing cost and benefit with the ASCO and ESMO frameworks. Lancet Oncol 18:887-894, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vokinger KN, Hwang TJ, Grischott T, et al. : Prices and clinical benefit of cancer drugs in the USA and Europe: A cost-benefit analysis. Lancet Oncol 21:664-670, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vokinger KN, Hwang TJ, Daniore P, et al. : Analysis of launch and postapproval cancer drug pricing, clinical benefit, and policy Implications in the US and Europe. JAMA Oncol 7:e212026, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherny NI, de Vries EGE, Dafni U, et al. : Comparative assessment of clinical benefit using the ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale version 1.1 and the ASCO value framework net health benefit score. J Clin Oncol 37:336-349, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar H, Fojo T, Mailankody S: An appraisal of clinically meaningful outcomes guidelines for oncology clinical trials. JAMA Oncol 2:1238-1240, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Australia, Canada, Singapore, Switzerland (ACSS) Consortium : New Chemical Entities Work Sharing Initiative (NCEWSI) Overview, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/international-activities/australia-canada-singapore-switzerland-consortium/new-chemical-entities-work-sharing-initiative-overview.html [Google Scholar]

- 20.Federal Act on Medicinal Products and Medical Devices (Therapeutic Products Act, TPA), 2019. Article 9b. https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/20002716/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration : FDA Approves First New Drug under International Collaboration, A Treatment Option for Patients with HER2-Positive Metastatic Breast Cancer. FDA, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-new-drug-under-international-collaboration-treatment-option-patients-her2 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesselheim AS, Woloshin S, Eddings W, et al. : Physicians' knowledge about FDA approval standards and perceptions of the “breakthrough therapy” designation. JAMA 315:1516-1518, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shepshelovich D, Tibau A, Goldvaser H, et al. : Postmarketing modifications of drug labels for cancer drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration between 2006 and 2016 with and without supporting randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 36:1798-1804, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mostaghim SR, Gagne JJ, Kesselheim AS: Safety related label changes for new drugs after approval in the US through expedited regulatory pathways: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 358:j3837, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Downing NS, Shah ND, Aminawung JA, et al. : Postmarket safety events among novel therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration between 2001 and 2010. JAMA 317:1854-1863, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beall RF, Hwang TJ, Kesselheim AS: Major events in the life course of new drugs, 2000-2016. N Engl J Med 380:e12, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang TJ, Darrow JJ, Kesselheim AS: The FDA's expedited programs and clinical development times for novel therapeutics, 2012-2016. JAMA 318:2137-2138, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, et al. : Regulatory review of novel therapeutics—Comparison of three regulatory agencies. N Engl J Med 366:2284-2293, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Food and Drug Administration : CDER Approval Times for Priority and Standard NDAs and BLAs, 2016. https://www.fda.gov/media/102796/download [Google Scholar]