Abstract

Prior studies established that the Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxidative stress response is influenced by iron availability, whereas more recent evidence demonstrated that it was also controlled by quorum sensing (QS) regulatory circuitry. In the present study, sodA (encoding manganese-cofactored superoxide dismutase [Mn-SOD]) and Mn-SOD were used as a reporter gene and endogenous reporter enzyme, respectively, to reexamine control mechanisms that govern the oxidative stress response and to better understand how QS and a nutrient stress response interact or overlap in this bacterium. In cells grown in Trypticase soy broth (TSB), Mn-SOD was found in wild-type stationary-phase planktonic cells but not in a lasI or lasR mutant. However, Mn-SOD activity was completely suppressed in the wild-type strain when TSB was supplemented with iron. Reporter gene studies indicated that sodA transcription could be variably induced in iron-starved cells of all three strains, depending on growth stage. Iron starvation induction of sodA was greatest in the wild-type strain and least in the lasR mutant and was maximal in stationary-phase cells. Reporter experiments in the wild-type strain showed increased lasI::lacZ transcription in response to iron limitation, whereas the expression level in the las mutants was minimal and iron starvation induction of lasI::lacZ did not occur. Studies comparing Mn-SOD activity in P. aeruginosa biofilms and planktonic cultures were also initiated. In wild-type biofilms, Mn-SOD was not detected until after 6 days, although in iron-limited wild-type biofilms Mn-SOD was detected within the initial 24 h of biofilm establishment and formation. Unlike planktonic bacteria, Mn-SOD was constitutive in the lasI and lasR mutant biofilms but could be suppressed if the growth medium was amended with 25 μM ferric chloride. This study demonstrated that (i) the nutritional status of the cell must be taken into account when one is evaluating QS-based gene expression; (ii) in the biofilm mode of growth, QS may also have negative regulatory functions; (iii) QS-based gene regulation models based on studies with planktonic cells must be modified in order to explain biofilm gene expression behavior; and (iv) gene expression in biofilms is dynamic.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is ubiquitous, being found in diverse environments such as soil, freshwater, and marine environments. It is also an opportunistic pathogen of the airways of cystic fibrosis patients and in immunocompromised hosts including cancer, AIDS, and burn patients (16). Similar to other pathogens and gram-negative bacteria, P. aeruginosa has a global regulatory system known as quorum sensing (QS) that controls expression of numerous genes, many of which are associated with virulence (11, 37). Bacterial QS, or cell-to-cell communication, is a process in gram-negative and some gram-positive bacteria where low-molecular-weight diffusible molecules synthesized by one cell trigger gene activation in other cells (17). In gram-negative bacteria, the signaling molecules are either homoserine lactone/acyl side chain based (HSLs; autoinducers), diketopiperazine (29), or via 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4-quinolone (45), while gram-positive bacteria use small peptides. Because of its aforementioned ubiquity in nature and its importance in disease, P. aeruginosa is a model organism for QS study.

QS is viewed as a cell density-dependent phenomenon that allows bacteria to communicate, sense population density, and ultimately coordinate transcription of many genes. Bacteria monitor their population by sensing the level of autoinducer signal molecules (17). HSL-based QS in P. aeruginosa is a multitiered process governed by two gene tandems, lasR-lasI and rhlR-rhlI (41–43). The las system is composed of LasR, a transcriptional regulator protein, and LasI, an autoinducer synthase that produces one of the three known Pseudomonas HSLs, PAI-1 [N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone]. The second tier consists of RhlR, which is also a transcriptional regulator, and RhlI, an autoinducer synthase that catalyzes the synthesis of a second HSL, PAI-2 (N-butyryl-l-homoserine lactone). PAI-1 interacts with the regulator LasR to activate transcription of target genes (42). The LasR–PAI-1 complex will activate the transcription of lasI and several genes important in defense against oxidative stress such as those coding for the major catalase, KatA, and the manganese-cofactored superoxide dismutase (Mn-SOD) (27). Further, recent work by Whiteley et al. has identified many other QS-regulated genes that were previously unrecognized (52).

Whether considered in either disease or environmental settings, an important aspect of P. aeruginosa ecology is its propensity to form biofilms. P. aeruginosa biofilms have high cell densities and an architecture that typically consists of highly ordered mushroom- and pillar-like structures (7). This important aspect of P. aeruginosa biology has also been shown to be influenced by QS (8). QS-deficient mutants form a thin, tightly packed biofilm, differing markedly from wild-type biofilm architecture, suggesting that particular aspects of biofilm cell physiology are under control of QS and are important for normal biofilm formation. The physiology of bacterial biofilms is viewed to be different from that of planktonic cultures (7), but the true extent of such potential differences is still poorly understood.

We are examining P. aeruginosa biofilm responses to environmental stimuli as a means of studying gene expression and physiology of biofilm bacteria. We have elected to focus on the oxidative stress response because our knowledge of the antioxidant responses in this organism is firmly grounded genetically and physiologically (20–24) and because antioxidant enzymes are of central importance to the pathogenicity of this organism (26). Further, we have recently found that key components of the oxidative stress response are regulated by QS (27). Curiously, earlier studies had also implicated iron availability as a significant controlling factor in expression levels of antioxidant enzymes in P. aeruginosa (20–27). As QS has thus far been found to exert its effects when cell densities are high, a condition which is found in biofilms and which can lead to localized areas of high nutrient demand, we have hypothesized that nutrient limitation may also be an important factor to consider in studies aimed at understanding QS and biofilm biology (28). The availability of well-defined QS mutants offers an excellent opportunity to examine and compare gene expression in biofilms and planktonic cells under conditions where the availability of a specific nutrient can be conveniently and reliably manipulated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

P. aeruginosa wild-type strain PAO1 (30), the lasI::Tn10 mutant PAO-JP1 (44), and the lasR mutant PAO-R1 (42) were used in this study. Plasmids pDJH201 (contains sodA::lacZ [27]) and pPCS223 (contains lasI::lacZ [51]) were used in reporter gene experiments. These plasmids were introduced into the different strains by electroporation and maintained with carbenicillin (300 mg · liter−1). In each case, plasmid transformation was verified by restriction enzyme analysis of plasmid preparations (47) of the different transformants. In some experiments, iron bioavailability in the medium was manipulated by the addition of iron (25 μM FeCl3) or the iron-specific chelator 2,2-dipyridyl (500 μM for Trypticase soy broth [TSB] or 50 μM for 1/10 TSB).

Planktonic cultures were grown in TSB at 37°C in a rotary shaker at 300 rpm. Culture volumes did not exceed 10% of the flask volume to ensure maximum aeration. Biofilms were cultured using a drip flow reactor system previously described by Huang et al. (31) and included 316L stainless steel slides (1.3 by 7.6 cm) as the substratum. Briefly, 10 ml of 1/10 TSB was added to each chamber (four chambers per reactor), followed by inoculation with 1 ml of stationary-phase culture of the test strain grown in TSB. The reactor was then incubated horizontally at 37°C for 24 h to allow bacterial attachment to the substratum. Following the attachment period, the reactor was inclined 10° and a constant drip of 1/10 TSB was allowed to flow over the slides at a rate of 50 ml · h−1. Biofilms were cultured in a 37°C incubator. To achieve this, the sterile 1/10 TSB contained in the external carboy was preequilibrated to 37°C prior to entry into the drip flow reactor. To accomplish this, the medium was first preheated to 42°C by pumping through masterflex silicone tubing coiled in a 42°C water bath fixed atop the incubator chamber. The feed tubing leaving the 42°C water bath was foam insulated (to reduce thermal loss) and channeled through the heat vent hole of the culture incubator. A mercury thermometer was attached to the medium flow tubing via aluminum tape, providing for isothermic association with the tubing and verifying that the temperature of medium was 37°C as it entered the incubator chamber. A final temperature equilibration step designed to guarantee appropriate temperature involved additional coiling (3-m flow length) of the feed tubing in distilled water (2-liter beaker) that was equilibrated at 37°C within the chamber. This ensured a final medium temperature of 37°C prior to entry into the drip flow reactor. Silicone tubing exiting each reactor chamber was used to pump the waste out of the chamber and into external waste carboys.

Cell extract preparation, nondenaturing gel electrophoresis, and enzyme and reporter activity.

Nondenaturing gel electrophoresis methods were as described by Hassett et al. (26). Briefly, cell extracts were prepared from cultures harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Bacteria were washed twice in ice-cold 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) and sonicated in an ice water bath for 30 s. The sonicate was clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Extract protein content was estimated by the Bradford assay (2). SOD activity stains in nondenaturing gels were used to semiquantatively follow induction of Mn-SOD and to assess its activity separately from the constitutively expressed Fe-SOD (coded by sodB) (26). Gel images were computer scanned and stored as Powerpoint image files. LacZ reporter enzyme expression was measured as β-galactosidase activity as previously described by Miller (38).

RESULTS

Mn-SOD regulation.

Initial experiments compared Mn-SOD levels in the P. aeruginosa wild-type strain PAO1 and the lasI mutant PAO-JP1. In PAO1, Mn-SOD activity was detectable in stationary-phase cells (t = 12 h) (Fig. 1A), which correlates with the production and accumulation of the QS autoinducer molecule PAI-1 (27). Mn-SOD was absent from stationary-phase TSB cultures of the lasI mutant JP1, which cannot synthesize PAI-1 (44), and the lasR mutant PAO-R1, which lacks the regulatory protein essential to QS (12, 13) (results not shown). All of these observation were consistent with our previous findings, which showed that Mn-SOD production is controlled by QS in this organism (27).

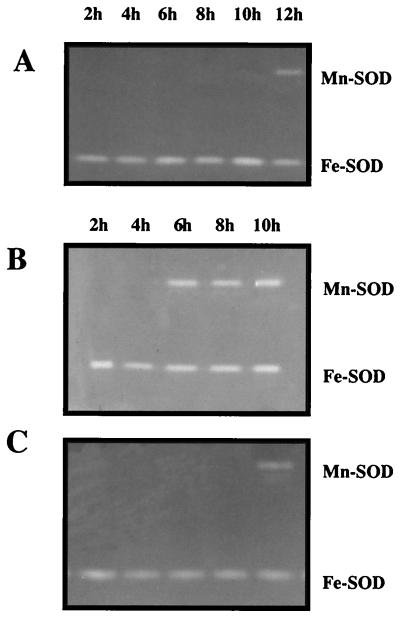

FIG. 1.

SOD activity in planktonic cells cultured in TSB. Cell extracts (50 μg of protein per lane) of each strain were prepared at different time points corresponding to different growth stages, 6 h (mid-log phase) and 10 h (early stationary phase). SOD activity stains of wild-type strain PAO1 cultured in TSB (A), PAO1 in TSB amended with the iron-specific chelator 2,2-dipyridyl (B), and the lasI mutant PAO-JP1 in TSB amended with the iron-specific chelator 2,2-dipyridyl (C) were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Results are of one of three independent experiments demonstrating this response.

Assessment of iron effects on QS-controlled gene expression was initiated in experiments where either TSB was supplemented with 25 μM FeCl3 or 500 μM 2,2-dipyridyl was added to render the iron unavailable. In wild-type cells cultured to stationary phase in iron-supplemented TSB, no Mn-SOD activity was observed in native gels (results not shown). When 2,2-dipyridyl was included in the culture medium, Mn-SOD was evident in mid-log-phase and stationary-phase PAO1 cells (Fig. 1B), but only in stationary phase in the lasI mutant PAO-JP1 (Fig. 1C) and the lasR mutant PAO-R1 (results not shown). The iron-sensitive Mn-SOD activity in PAO1 is consistent with prior work demonstrating iron-dependent sodA expression (23–25) and demonstrated that either excess or limiting iron can override QS control of sodA expression in P. aeruginosa.

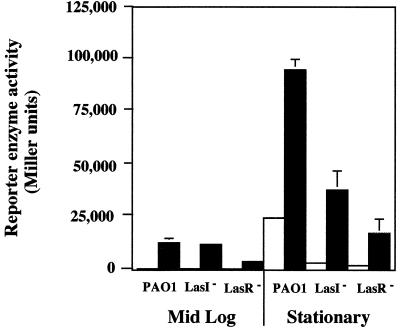

To establish whether the iron effect on Mn-SOD levels occurs at the transcriptional level, a plasmid containing a sodA::lacZ transcriptional fusion was transformed into PAO1, PAO-JP1, and PAO-R1, and the above experiments were repeated. As shown in Fig. 2, iron limitation increased sodA expression in PAO1 mid-log-phase cells. Iron limitation also caused equivalent levels of sodA up-regulation in mid-log-phase cells of PAO-JP1 (Fig. 2), even though the isozyme was not apparent in activity stains of JP1 cell extracts (Fig. 1C). Reporter gene activity was also increased in iron-starved mid-log-phase cells of PAO-R1, but the increase was smaller than in strain PAO1 or PAO-JP1 (Fig. 2). In stationary-phase cells, up-regulation of sodA in response to iron starvation also occurred. β-Galactosidase reporter enzyme levels measured in PAO1, PAO-JP1, and PAO-R1 were approximately 4-, 11-, and 7-fold greater, respectively, under iron-limiting growth conditions compared to cells with ample iron. The reporter gene results with both mid-log and stationary-phase cells again demonstrated that QS control of sodA could be overridden by the iron starvation response but also showed that the autoinducer PAI-1 and the regulatory protein LasR were still required for maximal sodA expression, regardless of iron availability. Further, these studies suggested that Mn-SOD activity in the lasI mutant was attenuated by abnormal posttranscriptional activity because iron starvation-based induction of sodA in mid-log-phase cells did not result in increased Mn-SOD levels in native gel SOD activity stains.

FIG. 2.

Transcription of sodA in mid-log-phase and stationary-phase cells of PAO1, PAO-JP1, and PAO-R1 as affected by iron limitation. Relative transcription levels were determined by measuring the reporter enzyme β-galactosidase as described by Miller (38) in planktonic cells harvested at mid-log (6 h) and late stationary (16 h) phases. Open bars, cells grown in TSB; filled bars, cells grown in TSB containing the iron-specific chelator 2,2-dipyridyl. The data represent the mean of three independent experiments (two to three cultures per experiment). Where visible, error bars denote 1 standard error.

Effects of iron concentration on lasI expression.

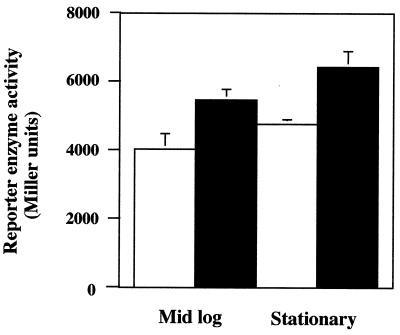

Additional experiments were conducted to determine if the iron starvation effect on sodA expression could be linked to las gene expression. Over three independent experiments, iron limitation increased lasI expression in the wild-type strain by approximately 30 to 35% (Fig. 3). The increase, while relatively small, was highly reproducible and statistically significant. However, no increase in lasI::lacZ reporter activity (range, 90 to 150 Miller units) could be measured under the same culture conditions for the lasI mutant and the lasR mutant (results not shown), implying again that the iron-based response appeared to require LasR and PAI-1 for the maximal effect to be observed. The lack of an iron effect on lasI induction in the LasI− mutant also demonstrated that potential alternative autoinducers were most likely not participating in the iron stress response under the conditions used for cell culture in these experiments.

FIG. 3.

Expression of lasI in response to iron deprivation. Wild-type strain PAO1 was transformed with pPCS223, which contains the lasI::lacZ reporter fusion (50), and then cultured to mid-log or stationary phase in TSB (open bars) or TSB amended with the iron-specific chelator 2,2-dipyridyl (filled bars). The data represent the average of the means of three independent experiments (two cultures per experiment). Error bars, where visible, represent 1 standard error of the three experimental means. Differences between iron treatments for each culture stage are statistically significantly different (P = 0.01).

Production of Mn-SOD in biofilms.

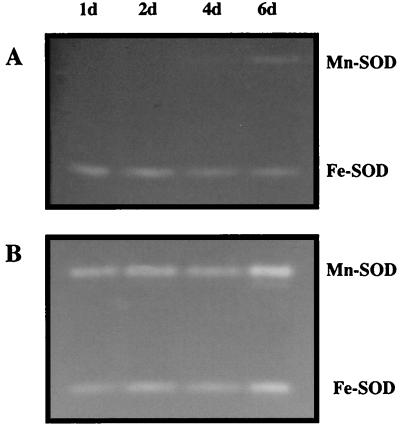

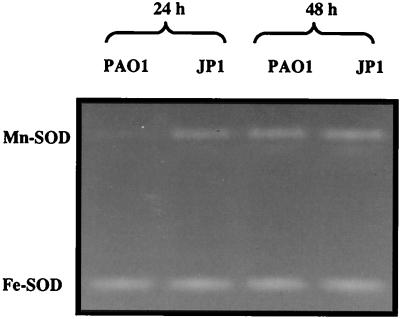

An additional important motivation for this study was to investigate potential differences in gene expression and regulation between biofilm cells and planktonic cells. The combination of mutants and the use of Mn-SOD as a native reporter enzyme provided an opportunity to assess the same regulatory issues when the cells were grown as biofilms and to determine if protein expression patterns were different. Surprisingly different Mn-SOD expression patterns were encountered between wild-type and QS mutant biofilms. Mn-SOD was observed only in mature (6-day) PAO1 biofilms (Fig. 4A), whereas it was expressed within the first 24 h of lasI mutant biofilm formation (Fig. 4B). In identical biofilm experiments with the lasR mutant, Mn-SOD levels were the same as observed with the lasI mutant (results not shown). Additional biofilm experiments were then conducted to assess whether biofilm cells would respond to iron manipulation as was observed with planktonic cultures. When 2,2-dipyridyl was included in the biofilm flow medium, Mn-SOD was evident in PAO1 biofilms; Mn-SOD activity stains obtained from 24-h biofilm cell extracts appeared weak, but by day 2, they were roughly equivalent to the lasI and lasR mutant biofilms (Fig. 5) in the other experiments. Given the apparent constitutive sodA expression in lasI and lasR biofilms, further biofilm experiments sought to establish whether sodA expression in JP1 and PAO-R1 biofilms was still sensitive to environmental iron concentrations. This was confirmed by supplementing the biofilm medium with iron (25 μM FeCl3). When iron was provided at such ample levels, Mn-SOD was absent in biofilms of wild-type and both mutant strains for the duration of the experiments (up to 6 days [results not shown]). During the course of all biofilm experiments, no apparent changes in the Fe-SOD activity band occurred (results not shown).

FIG. 4.

SOD activity stains of cell extracts (50 μg of protein per lane) of the wild-type strain PAO1 (A) and the lasI mutant PAO-JP1 (B) obtained from biofilms cultured with 1/10 TSB for up to 6 days (6d). The data are representative of duplicate experiments, and locations of the Mn-SOD and Fe-SOD bands are as shown.

FIG. 5.

Mn-SOD expression in PAO1 biofilms as affected by iron starvation. SOD activity was detected using activity stains as described in Materials and Methods. Cell extracts (50 μg per lane) were obtained from PAO1 biofilms grown for 1 or 2 days in 1/10 TSB containing the iron-specific chelator 2,2-dipyridyl and from 1- and 2-day PAO-JP1 biofilms grown in 1/10 TSB. The data are representative of duplicate experiments, and locations of the Mn-SOD and Fe-SOD bands are as shown.

DISCUSSION

Nutritional override of QS.

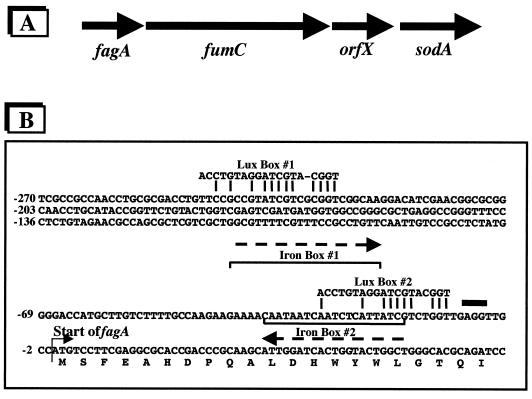

It is clear that HSLs are critical for activation of the QS regulatory circuitry in P. aeruginosa. However, prior to the discovery of QS in this organism, the production of several gene products now known to be QS regulated was initially found to be up-regulated by nutritional factors. An example of overlap between a nutrient limitation response and QS-regulated activity in P. aeruginosa is pyocyanin production. This exoproduct is typically observed in stationary-phase cells and is controlled by QS (4) but can also be induced by phosphate starvation (20). The effects of other nutrients such as iron have been observed more frequently. Elastase synthesis has been shown to be QS controlled (41, 53); however, its production occurs maximally when P. aeruginosa is iron limited but is restricted in the presence of iron (1, 32, 49). Expression of sodA was also previously shown to be iron regulated (23–25) and then later found to be controlled by QS (27). Reporter experiments in the present study established that sodA can be induced by iron limitation in either log-phase or stationary-phase cells of the wild-type strain (Fig. 1A, 1B, and 2) and QS mutants (Fig. 2). However, relative to the wild-type strain, maximal iron stress-dependent sodA induction was much lower in mid-log-phase lasR cells and in stationary-phase cells of both las mutants (Fig. 2). This implies that the autoinducer PAI-1 and the LasR regulatory protein were still required for maximum iron-starved sodA induction under these experimental conditions. This was particularly apparent in stationary-phase cells, where QS is thought to be most active in gene regulation. It is perhaps important that even though relatively quite low, sodA::lacZ expression in the LasR− and LasI− mutants was still inducible by iron starvation (Fig. 2). This suggests the possibility that QS-targeted promoters such as that governing the fagA-fumC-orfX-sodA operon can still be binding targets for RNA polymerase in the absence of positive regulatory complexes (such as LasR–PAI-1), if the repressor protein is also not present.

In addition, we bring attention to the observation that apparent wild-type sodA transcription occurred in mid-log-phase cells of the LasI− mutant (Fig. 2), but it did not translate into mature Mn-SOD enzyme as measured by activity stains in native gels (Fig. 1C). While activity stains in native gels are only semiquantitative, cell extract sample loading in these experiments was adequate to detect meaningful SOD enzyme levels, provided for reasonable strain and growth condition comparisons, and allowed for sensitive detection of this isozyme in a wild-type background. This basic observation implies that posttranscriptional processing of the sodA mRNA was altered in the las mutants. Further, it suggests that LasI, or the autoinducer it synthesizes (PAI-1), is involved in some as yet unknown but essential cellular activity at low cell densities.

The overall iron effect on lasI expression (Fig. 3) was small relative to increases in lasI transcription previously observed in stationary-phase cells (35), but we note that the increase was highly reproducible and thus directly links the iron stress response with QS circuitry. Integration of QS with nutrient availability should not be unexpected, and it is perhaps no coincidence that QS-based regulation is most often observed in stationary-phase cultures when cell densities approach levels that represent a significant nutrient sink and indeed growth rates are declining due to limitation of some nutrient(s). Nutrients such as iron are subject to biotic and abiotic redox reactions, typically yielding insoluble precipitates under aerobic conditions. Thus, the bioavailability of such nutrients can be sparingly low regardless of local biological demand. In biofilms where cell densities can approach 1010 to 1012 cells per cm3 (6), low nutrient bioavailability coupled with high localized nutrient demand could result in a nutrient stress response. Lazazzera (36) has recently reviewed a similar concept for Bacillus subtilis, and there are other reports that suggest QS and nutrient sensing in gram-negative bacteria are integrated. Kjelleberg and colleagues have connected carbon starvation, QS, and the stringent response in a marine Vibrio isolate (14, 16, 39, 50). Other, similar interactions integrating nutrient limitation, cell-to-cell communication, and the stringent response have also been reported for Myxococcus xanthus (19, 33, 34, 48) and thus serve to further demonstrate the complexity of cell-to-cell signaling systems. When possible strategies for manipulating QS for controlling bacterial infections are considered, the effects of multiple control mechanisms or nutritionally based regulatory override systems must be recognized. The onset of QS-regulated gene expression relative to the accumulation of autoinducers or to other metabolites, and the timing of their accumulation relative to changes in the cell nutritional state, represents a critical area of research. To account for the observations made in this work, we examined the promoter region of the operon that contains sodA (Fig. 6). Iron boxes (Fur-Fe2+ binding sites [24]) and putative LasR–PAI-1 binding sites (designated Lux boxes) were found and are located such that under high iron conditions, the Fur repressor protein would bind as a dimer to the iron boxes, inhibiting binding and thereby reducing transcriptional activation by the LasR–PAI-1 complex. The occurrence of two (or more) regulatory elements in the promoter region of other QS-regulated genes has not been studied but represents an important issue for understanding and manipulating QS in bacteria.

FIG. 6.

A potential mechanism for dual control of sodA by iron-sensitive and QS circuitry. (A) Gene arrangement of the fagA-fumC-orfX-sodA operon. (B) DNA sequence directly upstream of fagA, which is promoter proximal in the depicted operon (24, 25). The Fur regulatory protein (encoded by fur, which is itself regulated by iron availability) utilizes Fe2+ as a corepressor (23). The Fe(II)-Fur complex directly binds to the promoter region of genes that contain a specific regulatory sequence known as the iron box (9). Sequence analysis suggests the presence of iron boxes (orientation of each shown as a dashed line), which is the binding site for Fe(II)-Fur. Note that Mn-SOD production is elevated in fur mutants (25). Iron boxes are located at nucleotide positions -18 to -37 and -21 to -42. Positions of putative Lux boxes, the binding site for the PAI-1–LasR complex, are also shown at -11 to -29 and at -228 to -247. Nucleotide positions that are homologous with the consensus Vibrio Lux box are indicated by the connecting lines. Under high iron conditions, binding of the iron box by the Fe(II)-Fur complex would inhibit the LasR–PAI-1 complex from binding to the Lux box 2 region and would also inhibit transcription possibly originating upstream due to potential activation from binding at Lux box 1. Upon iron starvation, the Fe(II)-Fur complex would not be present, and thus the LasR–PAI-1 complex would be free to activate transcription. The bold thick line indicates a potential ribosome binding site.

Biofilm gene expression.

Another important issue addressed in this study included P. aeruginosa biofilm cell physiology. The use of defined regulatory mutants and an endogenous reporter enzyme that had been shown to be controlled by both QS and nutritional effects presented an opportunity to assess basic protein expression in biofilms and make relevant comparisons to planktonic cells. P. aeruginosa has been used as a model organism for studying biofilm behavior and for the development of biofilm control strategies (7), and though recent progress has been significant, P. aeruginosa biofilm cell physiology is still only poorly understood. Particularly lacking is information regarding gene expression and regulation. Gradients in metabolic activity have been shown to exist in P. aeruginosa biofilms, and some information regarding adaptive gene regulation has also been recently published (31). These studies examined P. aeruginosa gene regulation in response to environmental stress, showing, for example, that induction of phoA in response to phosphate limitation occurred only in the upper region (ca. 20%) of the biofilm (31).

In the present study, differences in Mn-SOD levels between wild-type and QS mutant biofilms were significant. Whereas Mn-SOD activity was not detected in wild-type biofilms until after 6 days, it was detectable within the first 24 h of biofilm formation by both las mutants. The notable lack of Mn-SOD in wild-type biofilms implies that the cells were not limited for iron and is consistent with an analysis of iron availability under these growth conditions. Chemical analysis of TSB showed an iron concentration of 15 μM. The iron content in the 1/10 TSB used for biofilm experiments would be proportionately lower, but the constant flow would continuously deliver fresh medium over the developing biofilm. Over the course of such experiments, the total iron made available to the developing biofilm would exceed batch conditions at least eightfold, while total biomass generated in the different growth modes would be similar (T. R. McDermott and D. J. Hassett, unpublished data). The appearance of Mn-SOD in 6-day-old wild-type biofilms likely represents iron limitation resulting from the reduced iron in 1/10 TSB being insufficient for the high cell numbers accumulated during this time period (∼5.0 × 1010 total on the stainless steel slide) and/or potential diffusion limitations.

The constitutive presence of Mn-SOD in the las mutant biofilms reveals a potentially important behavior difference between wild-type and las mutant cells and an as yet undefined (but not necessarily unexpected) important characteristic of QS regulation. As implied by the Mn-SOD activity in the las mutant biofilms, the absence of normal QS regulatory components resulted in the apparent unrestricted expression of sodA, suggesting that in biofilm cells QS regulation may exert negative gene control. An alternative explanation is that developmentally immature biofilms have an increased iron requirement that results in an iron stress response. However, adding the iron-specific chelator 2,2-dipyridyl to the medium of wild-type biofilms resulted in the induction of Mn-SOD activity, implying that such biofilms were not otherwise iron limited (also see above). However, there are other potentially important issues to consider in assessing the constitutive expression of Mn-SOD in lasI mutant biofilms. There are alternative transcriptional start sites within fagA and fumC (24) that could result in sodA expression and represent biofilm-specific gene regulation, and it has been established that synthesis of the P. aeruginosa iron chelator pyoverdine is responsive to iron availability (46) and also under QS control (51). In the biofilm experiments conducted with the lasI mutant, lack of the iron chelator pyoverdine could conceivably result in significantly reduced iron acquisition by the mutant and thus result in an iron starvation-like response. Regardless, the constitutive presence of Mn-SOD in las mutant biofilms suggests that a biofilm-specific regulatory system that is independent of the Las system is present and can affect gene expression in the absence of LasR or PAI-1. This may be an important consideration when evaluating autoinducer analogs as an alternative chemotherapy for biofilm-related infections.

Of additional importance, the experiments in this study demonstrated that biofilm cells respond like planktonic cells to environmental effects—in this case, iron concentration. The addition of iron to the biofilm medium caused las mutant biofilms to predictably repress Mn-SOD levels, and likewise the addition of 2,2-dipyridyl to the medium caused wild-type biofilm cells to up-regulate Mn-SOD activity (Fig. 5). This suggests that at least in the case of sodA control, basic iron sensor-response circuitry is unchanged for cells growing in either setting. The basis for the apparent up-regulation of sodA in the QS mutant biofilms under conditions that are not obviously iron limiting is the focus of continuing experiments.

In summary, this study demonstrated that (i) the nutritional status of the cell must be taken into account when evaluating QS-based gene expression, (ii) QS-based gene regulation models based on studies with planktonic cells must be modified in order to explain biofilm gene expression behavior, and (iii) gene expression in biofilms is dynamic. In addition, the results from the las mutant biofilms implied that QS regulation can exert negative regulatory control. Determining physiological differences between biofilms and planktonic cultures is critical to the understanding and eventual treatment of P. aeruginosa infections such as that found in the cystic fibrosis lung or for removing problematic biofilms from industrial or environmental settings. Previous studies showed evidence that bacteria in lung tissue grow under iron-limited conditions (5, 10, 18). Further experiments aimed at understanding in situ conditions and gene expression, particularly as related to P. aeruginosa infections, should offer significant opportunity to improve our understanding of disease and its control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material is based on work supported by National Science Foundation Center for Biofilm Engineering Cooperative Agreement EEC-8907039 (T.R.M.) and National Institutes of Health grants AI-40541 (D.J.H.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bjorn M J, Sokol P A, Iglewski B H. Influence of iron on yields of extracellular products in Pseudomonas aeruginosa cultures. J Bacteriol. 1979;138:193–200. doi: 10.1128/jb.138.1.193-200.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun V, Schaffer S, Hantke K, Troger W. Regulation of gene expression by iron. In: Hauka G, Thauer R, editors. The molecular basis of bacterial metabolism. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1990. pp. 164–179. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brint J M, Ohman D E. Synthesis of multiple exoproducts in Pseudomonas aeruginosa is under the control of RhlR-RhlI, another set of regulators in strain PAO1 with homology to the autoinducer-responsive LuxR-LuxI family. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7155–7163. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7155-7163.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown M R W, Anwar H, Lambert P A. Evidence that mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the cystic fibrosis lung grows under iron-restricted conditions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1984;21:113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Characklis W G, Marshall K C, McFeters G A. The microbial cell. In: Characklis W G, Marshall K C, editors. Biofilms. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 131–160. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costerton J W, Lewandowski Z, Caldwell D E, Korbe D R, Lappin-Scott H M. Microbial biofilms. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:711–745. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.003431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davies D G, Parsek M R, Pearson J P, Iglewski B H, Costerton J W, Greenberg E P. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science. 1998;280:295–298. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5361.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Lorenzo V, Wee S, Herrero M, Neilands J B. Operator sequences of the aerobactin operon of plasmid ColV-K30 binding the ferric uptake regulation (fur) repressor. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2624–2630. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2624-2630.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emery T. Iron metabolism in humans and plants. Am Sci. 1982;70:626–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuqua C, Winans S C, Greenberg E P. Census and conscensus in bacterial ecosystems: the LuxR-LuxI family of quorum-sensing transcriptional regulators. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:727–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gambello M J, Iglewski B H. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa lasR gene: a transcriptional activator of elastase expression. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:3000–3009. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.3000-3009.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gambello M J, Kaye S, Iglewski B H. LasR of Pseudomoas aeruginosa is a transcriptional activator of the alkaline protease gene (apr) and an enhancer of exotoxin A expression. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1180–1184. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.4.1180-1184.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Givskov M, de Nys R, Manefield M, Gram L, Maximilien R, Eberl L, Molin S, Steinberg P D, Kjelleberg S. Eukaryotic interference with homoserine lactone-mediated prokaryotic signaling. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6618–6622. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6618-6622.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govan J R W, Deretic V. Microbial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis: mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:539–574. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.3.539-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gram L, de Nys R, Maximillen R, Givskov M, Steinberg P D, Kjelleberg S. Inhibitory effects of secondary metabolites from the red alga Delisea pulchra on swarming mobility of Proteus mirabilis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4284–4287. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4284-4287.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg E P. Quorum sensing in gram-negative bacteria. ASM News. 1997;63:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haas B, Kraut J, Marks J, Zanker S C, Castigenetti D. Siderophore presence in sputa of cystic fibrosis patients. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3997–4000. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.3997-4000.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris B Z, Kaiser D, Singer M. The guanosine nucleotide (p)ppGpp initiates development and A-factor production in Myxococcus xanthus. Genet Dev. 1998;12:1022–1035. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassett D J, Charniga L, Bean K A, Ohman D E, Cohen M S. Response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to pyocyanin: mechanisms of resistance, antioxidant defenses, and demonstration of a manganese-cofactored superoxide dismutase. Infect Immun. 1992;60:328–336. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.328-336.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassett D J, Woodruff W A, Wozniak D J, Vasil M L, Cohen M S, Ohman D E. Cloning and characterization of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa sodA and sodB genes encoding manganese- and iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase: demonstration of increased manganese superoxide dismutase activity in alginate-producing bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7658–7665. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.23.7658-7665.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hassett D J, Schweizer H P, Ohman D E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa sodA and sodB mutants defective in manganese- and iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase activity demonstrate the importance of the iron-cofactored form in aerobic metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6330–6337. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6330-6337.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hassett D J, Sokol P, Howell M L, Ma J-F, Schweizer H P, Ochsner U, Vasil M L. Ferric uptake regulator (Fur) mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa demonstrate defective siderophore-mediated iron uptake and altered aerobic metabolism. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3996–4003. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.3996-4003.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hassett D J, Howell M L, Ochsner U, Vasil M, Johnson Z, Dean G E. An operon containing fumC and sodA encoding fumarase C and manganese superoxide dismutase is controlled by the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: fur mutants produce elevated alginate levels. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1452–1459. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1452-1459.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hassett D J, Howell M L, Sokol P A, Vasil M L, Dean G E. Fumarase C activity is elevated in response to iron deprivation and in mucoid, alginate-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa: cloning and characterization of fumC and purification of the native FumC. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1442–1450. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1442-1451.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassett D J, Elkins J G, Ma D-J, McDermott T R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm sensitivity to biocides: use of hydrogen peroxide as a model antimicrobial agent for examining resistance mechanisms. Methods Enzymol. 1999;310:599–608. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)10046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassett D J, Ma J-F, Elkins J G, McDermott T R, Ochsner U A, West S E H, Huang C-T, Fredericks J, Burnett S, Stewart P S, McFeters G, Passador L, Iglewski B H. Quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa controls expression of catalase and superoxide dismutase genes and mediates biofilm susceptibility to hydrogen peroxide. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:1082–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassett, D. J., U. A. Ochsner, T. de Kievit, B. H. Iglewski, L. Passador, T. S. Livinghouse, J. A. Whitsett, and T. R. McDermott. Genetics of quorum sensing circuitry in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for control of pathogenesis, biofilm formation and antibiotic/biocide resistance. In U. Streips and R. Yasbin (ed.), Modern molecular genetics, in press. Wiley-Liss, New York, N.Y.

- 29.Holden M T, Ram Chhabra S, de Nys R, Stead P, Bainton N J, Hill P J, Manefield M, Kumar N, Labatte M, England D, Rice S, Givskov M, Salmond G P, Stewart G S, Bycroft B W, Kjelleberg S, Williams P. Quorum-sensing cross talk: isolation and chemical characterization of cyclic dipeptides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1254–1266. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holloway B W. Genetics of Pseudomonas. Bacteriol Rev. 1969;33:419–443. doi: 10.1128/br.33.3.419-443.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang C-T, Xu K D, McFeters G A, Stewart P A. Spatial patterns of alkaline phosphatase expression within bacterial colonies and biofilm in response to phosphate starvation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:1526–1531. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.4.1526-1531.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iglewski B H, Rust L, Bever R. Molecular analysis of Pseudomonads elastase. In: Silver S, Chakrabarty A M, Iglewski B H, Kaplan S, editors. Pseudomonas: biotransformations, pathogenesis, and evolving biotechnology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 36–53. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuspa A, Kroos L, Kaiser D. Intercellular signaling is required for developmental gene expression in Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1986;117:267–276. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuspa A, Plamann L, Kaiser D. Identification of heat-stable A-factor from Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3319–3326. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.10.3319-3326.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Latifi A, Foglino M, Tanaka K, Williams P, Lazdunski A. A hierarchial quorum-sensing cascade in Pseudomonas aeruginosa links the transcriptional activators LasR and RhlR (VsmR) to expression of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:1137–1146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lazazzera B A. Quorum sensing and starvation: signals for entry into stationary phase. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mekalanos J J. Environmental signals controlling expression of virulence determinants in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1–7. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.1.1-7.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Östling J, Flärdh K, Kjelleberg S. Isolation of a carbon starvation regulatory mutant in a marine vibrio. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6978–6982. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6978-6982.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Östling J, Holmquist L, Kjelleberg S. Global analysis of the carbon starvation response of a marine vibrio disrupted in genes homologous to relA and spoT. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4901–4908. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.16.4901-4908.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Passador L, Cook J M, Gambello M J, Rust L, Iglewski B H. Expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes requires cell-to-cell communication. Science. 1993;260:1127–1130. doi: 10.1126/science.8493556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pearson J P, Gray K M, Passador L, Tucker K D, Eberhard A, Iglewski B H, Greenberg E P. Structure of the autoinducer required for expression of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:197–201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pearson J P, Passador L, Iglewski B H, Greenberg E P. A second N-acylhomoserine lactone produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1490–1494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearson J P, Everett C P, Iglewski B H. Roles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa las and rhl quorum-sensing systems in control of elastase and rhamnolipid biosynthesis genes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5756–5767. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5756-5767.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pesci E C, Milbank J B, Pearson J P, McKnight S, Kende A S, Greenberg E P, Iglewski B H. Quinolone signaling in the cell-to-cell communication system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:11229–11234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rombel I T, McMorran B J, Lamont I L. Identification of a DNA sequence motif required for expression of iron-regulated genes in pseudomonads. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;246:519–528. doi: 10.1007/BF00290456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fristch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Singer M, Kaiser D. Ectopic production of guanosine penta- and tetraphosphate can initiate early developmental gene expression in Myxococcus xanthus. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1633–1644. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.13.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sokol P A, Cox C D, Iglewski B H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants altered in their sensitivity to the effect of iron on toxin A or elastase yields. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:783–787. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.783-787.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srinivasan S, Ostling J, Charlton T, de Nys R, Takayama K, Kjellberg S. Extracellular signal molecule(s) involved in the carbon starvation response of marine Vibrio sp. strain S14. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:201–209. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.2.201-209.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van Delden C, Pesci E C, Pearson J P, Iglewski B H. Starvation selection restores elastase and rhamnolipid production in a Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum-sensing mutant. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4499–4502. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4499-4502.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whiteley M, Lee K M, Greenberg E P. Identification of genes controlled by quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13904–13909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Winson M K, Camara M, Latifi A, Foglino M, Chhabra S R, Daykin M, Bally M, Chapon V, Salmond G P, Bycroft B W, Lazdunski A, Stewart G S A B, Williams P. Multiple N-acyl-l-homoserine lactone signal molecules regulate production of virulence determinants and secondary metabolites in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9427–9431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]