Abstract

For patients diagnosed with ovarian, uterine, or cervical cancer, race impacts expected outcome, with Black women suffering worse survival than White women for all three malignancies. Moreover, outcomes for Black women have largely worsened since the 1970s. In this narrative review, we first provide an updated summary of the incidence and survival of ovarian, uterine, and cervical cancer, with attention paid to differences between White and Black patients. We then offer a theoretical framework detailing how racial disparities in outcomes for each of the gynecologic malignancies can be explained as the sum result of smaller White-Black differences in experience of preventive strategies, implementation of screening efforts, early detection of symptomatic disease, and appropriate treatment. Much research has been published regarding racial disparities in each of these domains and with this review, we seek to curate the relevant literature and present an updated understanding of disparities between Black and White women with gynecologic malignancies.

Precis

Gaps in outcome exist between Black and White women with gynecologic cancers. These are explained in this narrative review as the accrual of more subtle disparities along the timeline of cancer development, diagnosis, and treatment.

Introduction

Nearly 20 years ago, the National Academy of Medicine (formerly IOM) published Unequal Treatment, an extensive review of the contemporaneous data on race- and ethnicity-based disparities in care delivered within the United States’ health system1. The report illustrated the pervasive inequities between the medical care delivered to Black and White patients in our country. Among them were disturbing findings spanning all fields of medicine: Black patients are less likely to receive standard cardiovascular care, less likely to be added to a renal transplant list, and less likely to receive appropriate intensive care compared to their White peers, even when presenting with the same severity of disease and after controlling for health and insurance status1–5. The difference in treatment given, problematic in and of itself, is not the only issue at hand; there are also race-based disparities in the incidence and natural history of many diseases, driven by a complex interplay of social, economic, political, and biological factors. For example, Black women are at least twice as likely as White women to deliver prematurely and nearly four times as likely to die of pregnancy-related complications6–8. This likely reflects an intricate relationship between racial predisposition to pregnancy-related illness like hypertension, perhaps caused or aggravated by social stressors experienced more acutely by Black women, and intensified by economic marginalization driven by policies that have disproportionately harmed Black people.

Given what is known of other fields of medicine, it is perhaps not surprising there exist race-based disparities in outcomes of women with gynecologic cancers. In this narrative review, we first aim to present data from the American Cancer Society (ACS) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) databases detailing the trends in incidence and outcomes for the three most common gynecologic cancers (uterine, ovarian, and cervical) over the past half century in the US, with a focus on how these compare between Black and White women. As part of the second aim of this review, we incorporate the theoretical framework described below to better explain how these disparities in gynecologic cancer outcomes between Black and White women might be perpetuated.

Racial disparities in the natural history of cancer: a theoretical framework

The natural history of cancer has several critical junctures: prevention (HPV vaccination), risk factor acquisition (obesity), screening (cervical cytology), diagnosis (endometrial biopsy for postmenopausal bleeding), and treatment (appropriate surgery by appropriate provider). Racial variation at any point along this course might contribute to minor disparate outcomes, while even subtle inequities at multiple nodes might accumulate to create more glaring gaps in outcome. It is through the lens of this framework that we present the many factors resulting in the differences between Black and White women with gynecologic cancers.

Methods

All statistics on cancer incidence and outcome were obtained from publicly available databases accessed online on the ACS and SEER websites. Due to the breadth of the topic, a comprehensive systematic review was not deemed feasible. A subjective curation of the available literature was performed with the goal of producing a single-source, narrative overview of the current state and knowledge of disparities in gynecologic malignancies. To identify relevant literature, PubMed was queried for publications including the Medical Search Headings (MeSH) term “racial disparities” in combination with terms specific to each subtopic (“HPV vaccination,” “cervical cancer screening,” “postmenopausal bleeding,” “endometrial cancer OR uterine cancer,” “ovarian cancer,” “cervical cancer,” and “clinical trials”). Abstracts of returned articles were reviewed to determine relevance. To limit the number of references, where multiple articles addressed the same study question, a single publication was chosen unless it was thought multiple references would meaningfully enhance the understanding of the topic.

Uterine cancer

Epidemiology

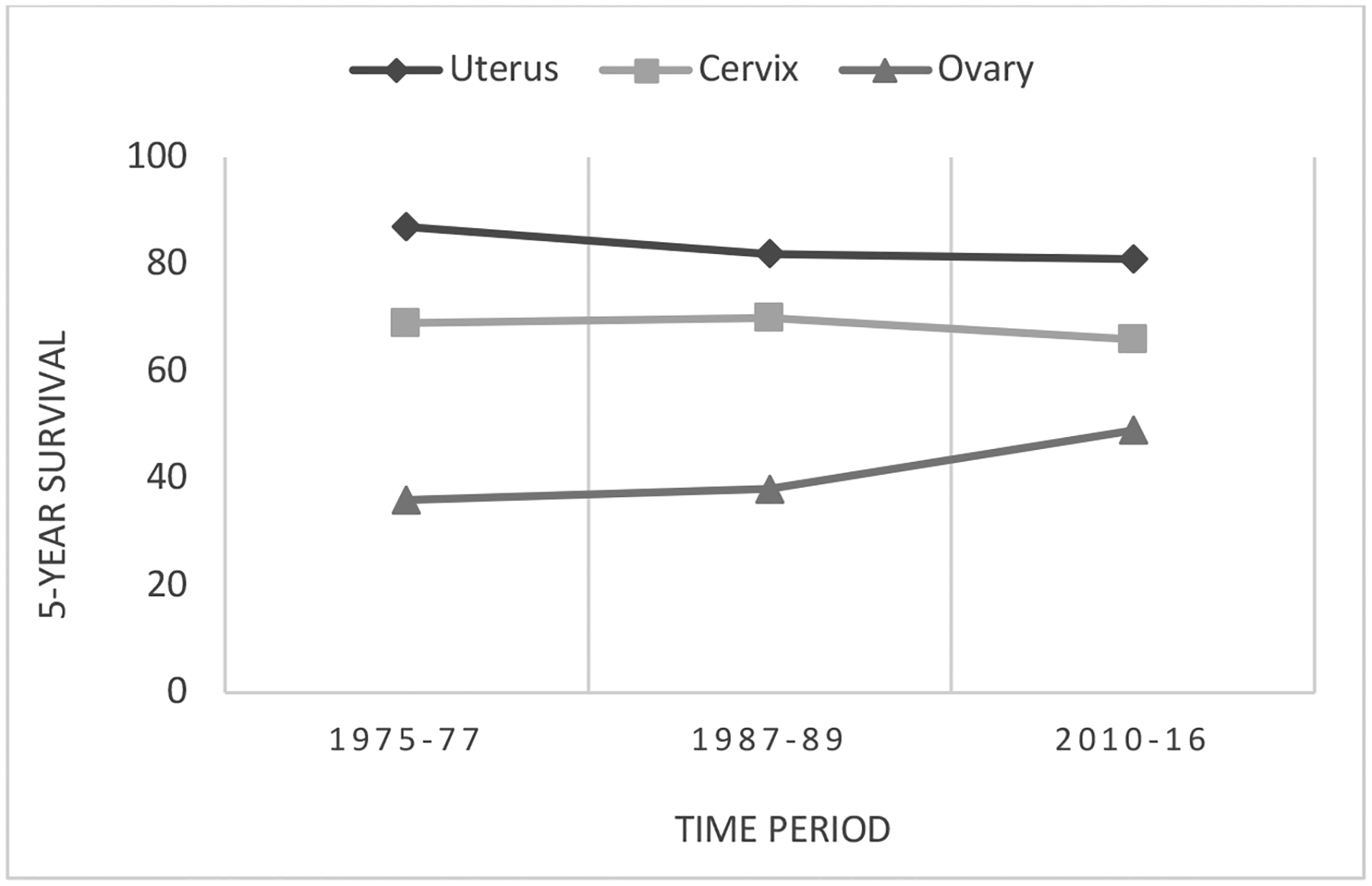

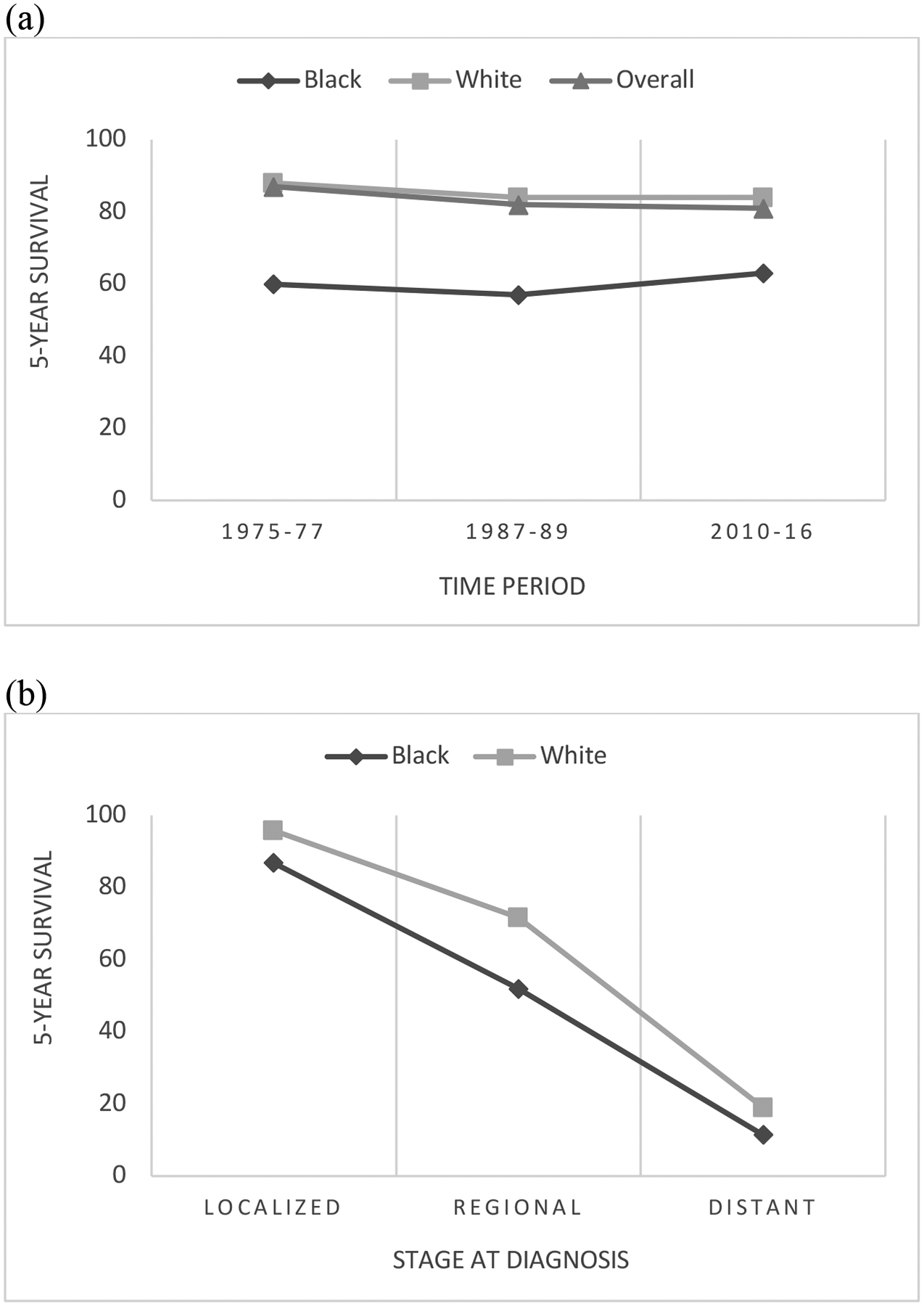

There will be nearly 66,000 new diagnoses of cancer of the uterine corpus in 2022, with the overall incidence slowly rising since the beginning of this century after a period of decline from the 1970s to 1990s9,10. The vast majority of these will be found within the endometrium, 80% of which will be of the endometrioid histologic subtype11. In 2018, the incidence for all races was 28.5 per 100,000 and while the incidence for White women remained stable for the second year in a row, at 28.6 per 100,000, the incidence among Black women rose, as it has every year for the past 20 years, to 29.8 per 100,0009. Though it exists within the entire population of endometrial cancer patients, the disparity is most striking in women with carcinosarcoma; over the past several decades, the racial breakdown of patients with this rare subtype has changed significantly, with White women comprising 86% of cases in the 1980s and 60.5% of cases in the mid 2010s. Black women, meanwhile, now account for 20.3% of cases, compared with 11.9% a few decades prior.12 This is proposed to reflect the changing demographics of the United States, which has experienced increases in both Black and aging populations.12 Since 1975, the 5-year survival for uterine cancer of all stages has declined slightly (Figure 1). Throughout this period, survival has been 19–28 percentage points higher in White women compared to Black9. Taking disease stage at time of diagnosis into account, White women continue to have a higher 5-year survival relative to Black women13. These findings are represented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Trends in 5-year relative survival for uterine, cervical, and ovarian cancer in the United States.

Data source: American Cancer Society

Figure 2.

Trends in 5-year relative survival for uterine cancer in White and Black women in the United States, across all disease stages from 1975–2016 (a) and based on stage at time of diagnosis from 2011–2017 (b).

Data source: American Cancer Society, SEER database

Stage at diagnosis

Local disease is associated with a 95% 5-year survival, but the survival rate decreases to 17% in the setting of distant disease.14 Black women with endometrial cancer present with localized disease 54% of the time and with regional or distant metastases 39% of the time, compared with 71% and 26% amongst White women, respectively.15 This difference in stage at presentation contributes to the mortality gap between racial groups.16 It might be proposed that women of lower socioeconomic status, who are disproportionately Black, face more obstacles accessing health care and, as a result, experience a delay in timely evaluation of the hallmark abnormal uterine bleeding of endometrial cancer. However, research examining whether there exists a racial disparity in the timing of symptom onset to treatment has not demonstrated a significant difference.17 One study did find medical providers were less likely to recognize and appropriately evaluate concerning symptoms of endometrial cancer in Black women, and older Black women were least likely to receive guideline-concordant evaluation.18 These studies are seemingly contradictory and highlight the need for further research examining the question of symptom recognition and workup. Nevertheless, access to a healthcare provider who can evaluate postmenopausal bleeding cannot alone explain the racial gap in stage at diagnosis of endometrial cancer.

It is known that Black women are more likely to be diagnosed with a more aggressive histologic subtype of endometrial cancer compared to their White peers, which logically contributes to more advanced disease at the time of diagnosis.15 However, statistically controlling for tumor grade and histology does not eliminate the increased risk of disease spread in Black women, implying there are other factors involved.19

It should be noted that the standard workup of postmenopausal bleeding may inadvertently lend itself to discrimination against Black women. Transvaginal ultrasonography is accepted and employed ubiquitously as a tool for evaluating women with postmenopausal bleeding, as a means of determining who requires endometrial sampling, based off the understanding that the most common histologic subtype of endometrial cancer (endometrioid) is associated with an increased sonographic endometrial thickness. Most centers utilize a cutoff of 4 mm to prompt endometrial sampling. The quality of the imaging study can be affected by structural abnormalities within the uterus, including leiomyoma, which are more common in Black women. Additionally, a normal endometrial thickness does not rule out endometrial cancer of the less common and more aggressive subtypes, which are not associated with endometrial hyperplasia. Together, these aspects of the test pose a significant problem for Black women presenting with postmenopausal bleeding: the standard initial test is more likely to be falsely negative. Indeed, one simulated retrospective cohort study compared the standard endometrial thickness cutoff between White and Black women and found that while the sensitivity of the 4 mm cutoff for detecting endometrial cancer in White women was 87.9%, it was only 47.5% for Black women.20 Given that Black women are more likely to have a more aggressive histologic subtype, this underperforming screening test certainly may contribute to the gap in stage at diagnosis.

Genetic characteristics

Tumor histology significantly impacts survival and there are racial differences in endometrial cancer tumor characteristics. Uterine carcinosarcoma, a rare high-grade histologic subtype of endometrial cancer, is three times more common in Black women.21 Mutations in the tumor suppressor gene p53 are associated with more aggressive tumor behavior and have been found to be three times more common in Black women with endometrial cancer.22 Even within early-stage endometrial cancer, p53 mutations remain more common in Black women and portend a worse prognosis.23 Similarly, the HER2-neu proto-oncogene, which encodes a transmembrane receptor that binds to cellular growth factors and triggers tissue growth, is more likely to be mutated in Black women. Mutations leading to over-expression of the receptor are seen more frequently within the serous histology and just like p53, are present three times more frequently in Black women with endometrial cancer compared to White women, even among patients with serous histology.24 Meanwhile, mutations in the PTEN tumor suppressor gene, which feature more heavily in endometrioid histology and predict more favorable outcomes, are seen more frequently in the tumors of White women than those of Black women.25 While concerning, this difference in tumor biology is actionable, as HER2-neu is targeted with the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab; the drug is included in the National Cancer Center Guidelines for the treatment of advanced HER2-positive cancer. No studies were identified addressing whether there is a race-based discrepancy in how trastuzumab is offered or administered to women with HER2-positive uterine cancer. This would be an important area of investigation, as failure to routinely incorporate this into the treatment of patients with this disease subtype is an opportunity to improve outcomes.

The degree to which inherent differences in tumor biology contribute to observed survival disparities between White and Black women with endometrial cancer is unclear. One group examining single-institution data found no difference in survival after controlling for the more aggressive histologic subtypes seen in Black women.26 However, a contradictory analysis of SEER data determined that survival among Black women was worse within each histologic subtype.27 Notably, neither report controlled for genetic mutations, but rather the histologic subtypes commonly associated with certain mutations. As previously mentioned, even amongst women with a serous histologic subtype, Black women are more likely to have mutations within the Her2-neu proto-oncogene, therefore controlling for histologic subtype alone will fail to truly determine the effect differential tumor biology has on disparate survival outcomes.

Treatment

Contrary to those with ovarian cancer, Black women with uterine cancer are more likely to have surgical treatment at a high-volume institution, suggesting access to a gynecologic oncologist may not contribute to disparate outcomes.28 Perhaps this reflects differences in how these malignancies present; uterine cancer is typically a known diagnosis preoperatively, allowing for referral to appropriate institutions, while ovarian cancer is more likely to present with acute surgical complications, such as bowel obstruction. Conversely this finding may simply reflect the heterogeneity of literature on these subjects.

Despite having more access to high-volume institutions, Black women (as well as Hispanic and American Indian women) have a significantly lower likelihood of receiving NCCN guideline-concordant care compared with White women.29 From the time of diagnosis, Black women have a 5% increased rate of receiving no cancer treatment compared with White women (9% vs 4%).30 When surgery is pursued, Black women are less likely to be offered standard surgical treatment (hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, lymph node evaluation) and more likely to receive upfront radiation, even when diagnosed with locoregional disease.30,31 One study of women with endometrial cancer noted that the most common reason cited for not performing a hysterectomy on a patient was “contraindicated”; this perhaps reflects a difference in comorbidities, which are reported to be higher in Black women.19

Ovarian cancer

Epidemiology

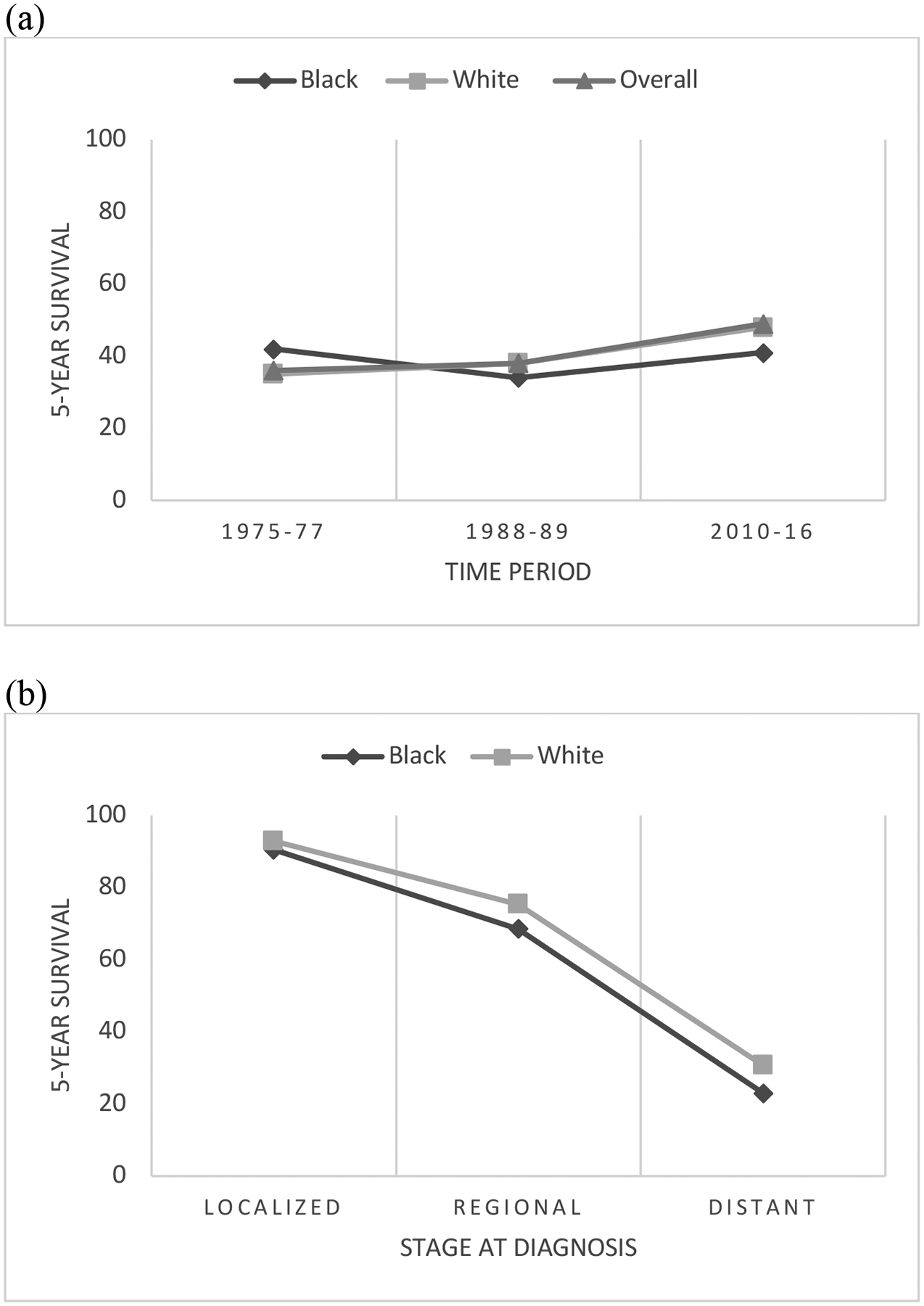

Since 1975, the incidence of ovarian cancer in the US has steadily declined, from 16.3 to 10.5 per 100,000 as of 201713. In 2022, there will be an estimated 20,000 new cases.10 Data from the past 20 years demonstrate the incidence decreased in both Black women (10.3 to 8.6 per 100,000) and White women (15.3 to 10.5 per 100,000)9. Over the past several decades, efforts to improve survival in patients with ovarian cancer have been fruitful (Figure 1). The 5-year survival for all stages of ovarian cancer has improved since 1975 from 36% to 49%13. This improvement in survival was not seen in the Black population. In 1975, 42% of Black women diagnosed with ovarian cancer could be expected to live 5 years, compared with 35% of White women13. Today, a Black woman has a 41.3% chance of surviving 5 years from the time of her diagnosis, while a White woman has a 49% chance, indicating Black women account for none of the survival gains in ovarian cancer seen over the past several decades9. These findings are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Trends in 5-year relative survival for ovarian cancer in White and Black women in the United States, across all disease stages from 1975–2016 (a) and based on stage at time of diagnosis from 2011–2017 (b).

Source: American Cancer Society, SEER database

Stage at diagnosis

Survival in patients with ovarian cancer is heavily influenced by stage at diagnosis: disease confined to the ovary confers an 85% five-year survival rate, which drops to 25% once the cancer has spread beyond the pelvis. For a variety of reasons, ovarian cancer is most often detected at an advanced stage in both White and Black women.32 However, it should be noted that one study employing a retrospective analysis of the California Cancer Registry did find Black race was associated with a statistically significant reduction in the odds of early-stage diagnosis.33

Treatment

Amongst patients with ovarian cancer, Black women are less likely to have access to a high-volume surgeon with gynecologic oncology training and are instead more likely to have their surgery completed by a benign gynecologist or a general surgeon in a more rural setting.34 Surgery by a gynecologic oncologist, as opposed to a benign gynecologist or general surgeon, offers improved survival outcomes for patients with ovarian cancer and increased likelihood of adherence to adjuvant treatment guidelines.35 Nearly 100% of cancer surgeries performed by gynecologic oncologists are properly and completely staged, compared with only 52% of those done by benign gynecologic surgeons and 35% of those done by general surgeons.36 Bristow and colleagues found Black race was associated with a decreased likelihood of hysterectomy, colon resection, lymphadenectomy, and treatment by a high-volume surgeon.37 Aranda et al. also observed that Black women were less likely to have their surgery performed by a high-volume surgeon, even after controlling for insurance status and income.38

More disturbingly, Black women are less likely than White women to be offered the standard of care, and less likely to be treated according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, which correlates with survival.39,40 This is not purely explained by rurality: in one study, Black women being treated in the same facility as White women – most commonly a teaching hospital with a cancer program – were more likely to be treated with surgery alone (for early stage) or chemotherapy alone (for late stage) ovarian cancer, rather than a combined treatment approach.41 A recent analysis by Matthews et al. found Black women with stage II or III ovarian cancer were over twice as likely as White women to not receive adjuvant chemotherapy after their primary debulking surgery.42 Amongst a cohort of elderly women, Black race was associated with a delay in initiation of chemotherapy, which predicted an increase in mortality.43 There is no clear explanation for this, though a combination of medical comorbidities, lack of economic flexibility, and both patient and physician beliefs regarding risks, goals of care, and prognosis likely all contribute. An analysis of non-Medicare patients in an equal-access care setting found Black women undergoing systemic chemotherapy treatment for ovarian cancer were more likely to have dose reductions, delays in therapy and early discontinuation of therapy. Within this cohort, Black women had the worst survival, even after adjusting for cumulative chemotherapy dose intensity.44 The authors of this study acknowledged that while information was not available to assess for all possible chemotherapy-associated toxicities to explain this discrepancy, they did not find neutropenia to be more severe in the Black population.44 Better understanding why Black women are more like to receive reduced and abbreviated courses of chemotherapy is a critical area for future research.

Cervical cancer

Epidemiology

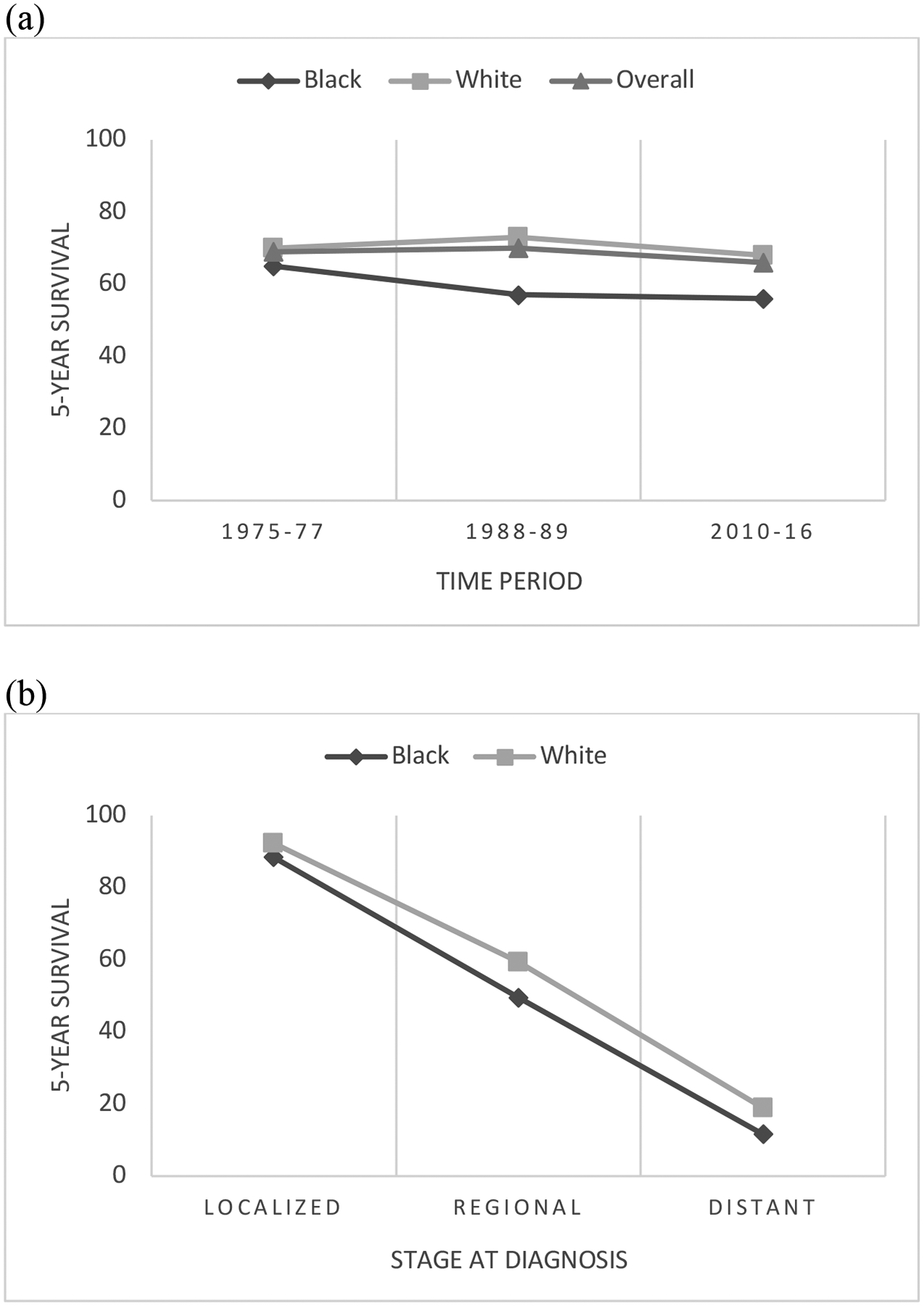

Approximately 14,000 new cervical cancer cases will be diagnosed in 2022.10 Between 2013–2017, the annual incidence of cervical cancer in the US was 7.2 per 100,000 in White women and 9 per 100,000 in Black women, with an overall incidence of 7.6 per 100,00013. Cervical cancer survival has decreased very slightly since 1975 (Figure 1). There are differences between Black and White women, both in survival outcomes, as well as how these outcomes have changed over time (Figure 4). The disparity in outcomes is greater at present than it was in the 1970s. Today, White women are 12% more likely than Black women to be alive 5 years after a cervical cancer diagnosis and the death rate from cervical cancer for Black women is 70% higher than in their White counterparts13,45. Even after controlling for confounding factors, such as age, histology type, and disease stage, Black women have a 19% increased risk of dying from their disease46.

Figure 4.

Trends in 5-year survival for cervical cancer in White and Black women in the United States, across all disease stages from 1975–2016 (a) and based on stage at time of diagnosis from 2011–2017 (b).

Source: American Cancer Society, SEER database

HPV vaccination

Cervical cancer is one of the few malignancies for which there exists a direct and effective prevention method in the HPV vaccine. Currently, Gardasil 9 (®Merck), a nonavalent recombinant vaccine, is the only HPV vaccine used in the US Most studies examining the efficacy of HPV vaccination have focused on the endpoints of HPV16/18 immunogenicity or incident infection, as nearly 70% of all cervical cancer cases are attributable to these two viral strains47. Data regarding Gardasil 9’s ability to prevent HPV16/18 infection are extrapolated from studies of its immunogenicity against these strains, which suggest a response comparable to its quadrivalent predecessor, Gardasil. Studies of the original Gardasil demonstrated a 96% reduction in short-term HPV16/18 infection and a 98% reduction in CIN2 related to those same strains47.

Data regarding HPV vaccination rates among different racial groups have been conflicting. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that across several studies, minority adolescents were significantly more likely to have provider-verified initiation of the HPV vaccination schedule compared to their White peers but were significantly less likely to complete the series48. Notably, the same meta-analysis found an inverse pattern of patient-reported rates of vaccine initiation; White patients were more likely to report having initiated the vaccine series compared with those in a racial minority group. This perhaps identifies an opportunity for patient education surrounding what vaccines have been given and what disease(s) they are intended to prevent.

Poverty is a significant independent predictor of non-adherence to the HPV vaccination schedule49, which might explain some degree of disparity in vaccine series completion. With poverty comes social and economic factors (social determinants of health) that drive lack of access to reliable transportation, childcare, ability to take time off work, etc. These factors may correspondingly impact a patient’s ability to follow through on receiving a complete vaccine series.

Cancer screening & early detection

Cervical cancer is unique among the gynecologic malignancies in that it lends itself to accessible, cost-effective, and relatively non-invasive screening. Moreover, screening is designed to detect an intermediary lesion, which can be treated to avert development of invasive disease. There appears to be no difference in screening rates between White and Black patients in the US; instead, lack of a regular source of healthcare and rurality are both factors associated with a lower cervical cancer screening rate.50,51 However, Black and other racial and ethnic minority women have a longer time between initial abnormal screening and final diagnosis, as well as higher rates of loss to follow-up of abnormal pap smears.52,53 One recent cross-sectional examination of the association between socioeconomic status and cervical cancer incidence in New York City found residing in the lowest socioeconomic status neighborhoods conferred a 73% higher likelihood of cervical cancer, suggesting it is not specifically distance to a healthcare facility which limits appropriate evaluation, but other socioeconomic factors.54

Stage at diagnosis

For patients with cervical cancer, 5-year survival with malignancy confined to the cervix is 92% but drops to 17% with metastatic disease.14 Possibly due to the aforementioned difference in follow-up of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests, Black women have a slightly higher rate of presenting with metastatic disease compared with White women (17% vs 14%) and are less likely to have disease confined to the cervix (36.4% vs 44.7%).55 This likely plays a major role in the disparate rates of 5-year survival seen between White and Black women with cervical cancer.

Treatment

When adjusting for disease stage, Black and White women with cervical cancer receive different treatment.56 Black women with cervical cancer are less likely to be offered the standard of radical hysterectomy for early disease, as well as less likely to receive radiation for locally advanced disease.30 Among those who receive radiation, Black women have a longer time to initiation of therapy.57 Multiple studies have determined Black women are less likely than White women to receive brachytherapy, which is associated with improved oncologic outcomes when utilized as part of a multimodal treatment approach.58–60 In a small analysis of 50 cervical cancer patients undergoing radiation treatment, mean time from diagnosis to completion of external beam radiation therapy was approximately 18 days longer in Black women vs White.61 The authors found no significant difference in side effects from treatment, but found public insurance status to be predictive of longer time to completion. The authors reported non-compliance, insurance coverage issues, and incarceration as the causes for treatment delay, acknowledging the so-called “non-compliance” was often due to inability to obtain childcare or transportation. Though this was a small pilot study, the findings highlight the interconnectedness of socioeconomic needs and health outcomes.

Clinical trial representation

Clinical trials are of utmost importance in ensuring disease pathophysiology and treatment modalities are explored. Minority representation in clinical trials ensures genetic variances, such as mutations in p53 or HER2-neu, and socioeconomic factors are studied further, to better understand their impact on patient outcomes and ideally identify more appropriate treatment options. Minorities are not well represented in clinical trials broadly, especially in the US. Of the trials which led to FDA approval of new drugs in 2018, 4% of participants were Black, despite their comprising 13.4% of the general US population. This pattern is echoed in gynecologic oncology. One group examined the proportion of White and Black participants in NRG Oncology (formerly known as Gynecologic Oncology Group- GOG) publications from the past 30 years to the ‘ideal’ composition if each race were represented according to their relative cancer prevalence. NRG Oncology trials did not publish racial breakdowns prior to 1994, so only 170 out of 445 total publications could be analyzed. For every gynecologic malignancy, there was a significant deficiency in Black patient representation. For ovarian cancer, the difference was 15-fold, for uterine cancer 10-fold, and for cervical cancer 4.5-fold.62

The reasons for this inadequate clinical trial representation are likely complex. Possibly patient distrust, borne of the memory of numerous historical research injustices such as the Tuskegee Syphilis trials, prevents Black patients from choosing to enter clinical trials. Survey data suggest Black patients have a higher fear of being experimented upon compared with White patients, but they nevertheless report themselves as likely to participate in clinical trials as their White colleagues.63,64 In a qualitative study in which Niranjan et al. interviewed various stakeholders at 5 US cancer centers, many clinicians and research staff reported negative perceptions regarding minority interest in, qualification for, and compliance with clinical trials. Participants felt it was more difficult to communicate with minorities regarding enrollment in clinical trials and minorities would be less likely to be able or willing to comply with the requirements of the trials. Because of these perceptions, some reported feeling less inclined to offer clinical trial participation to minorities. Notably, some participants felt it was helpful to directly address past instances of minority abuse in the name of research, whereas others felt it was preferable to be “colorblind” when screening and enrolling patients for clinical trials.65

Discussion

In this narrative review, we present literature we judged most salient in both illustrating the Black-White outcome gap in gynecologic cancers and proposing explanations for the findings. With our goal of highlighting an exceptionally broad area of active research, we did not endeavor to complete a systematic review of all published literature on the subjects. We believe each subtopic discussed in this review would be appropriate as an individual systematic review and encourage such efforts. Certainly, the non-systematic approach we used is prone to bias, no matter how we endeavored to remain objective in our assessment of articles. Moreover, there is exceptional heterogeneity among the articles referenced, with inconsistent levels of scientific rigor and variable inclusion/exclusion criteria. While we acknowledge these limitations, we feel the general inference remains the same: Black women fare worse with gynecologic cancers, likely due to a culmination of small disparities in multiple arenas.

The current situation is not beyond rectification. In GOG clinical trials for ovarian cancer, when women are randomized to treatment groups irrespective of race, disparities in outcomes between Black and White women disappear.66 The same is true for uterine carcinosarcoma.21 An examination of patients in the military, where access to and coverage for medical care is homogeneous, found there were no racial differences in age or stage at diagnosis of cervical cancer. Likewise, there was no difference in treatment approach. In this setting, where women were screened equally, cancer was detected at equivalent stages, and all were treated in the same manner, survival outcomes between the two races were equivalent.67 Similarly, when Black women receive standard of care brachytherapy with external beam radiation therapy, racial disparities in survival of cervical cancer are resolved.58

Unfortunately, even in the context of a controlled clinical setting, Black women with endometrial cancer seem to fare worse than White women, with lower treatment response rates, shorter periods of remission, and lower rates of survival.68,69 Examination of a military population by Park et al. found even within that equal-access setting, Black women with endometrial cancer had higher mortality rates, despite adjusting for histologic subtype.70 Huang et al. examined whether adherence to endometrial cancer treatment guidelines resolved the gap in outcomes between Black and White women and found even perfect adherence to treatment recommendations did not yield equivalent survival rates for Black women.71 Notably, Ruah-Hain et al. determined within a Medicare population, survival differences between Black and White women with endometrial cancer are eliminated after adjusting for treatment, socioeconomic factors, comorbidities, and histologic subtype, suggesting there are perhaps certain populations for whom equivalent outcomes are possible.72

These findings emphasize the effect of genetic variances between Black and White women on endometrial cancer behavior, as well as the potential influence of socioeconomic factors and comorbidities on survival. This represents a critical opportunity for further research, both into molecular genetic pathophysiology and treatment strategies, as well as the role of coexisting health and environmental factors on disease response and survival. Here again, the importance of diverse representation in clinical trials is underlined.

The cause of existing disparities is multifaceted, and so will be the solution. As the World Health Organization clearly states, cervical cancer can be eradicated through addressing several main pillars: ensuring equal access and ready availability of the HPV vaccine to vulnerable populations, stressing the importance of cervical cancer screening, facilitating follow-up of abnormal cytology results, and employing guideline-concurrent therapies in the treatment of cervical cancer.73 Similarly, adherence whenever possible to evidence-based guidelines would likely diminish disparities in survival amongst ovarian cancer patients.

While endometrial cancer presents unique challenges, there are clear opportunities for improved practice. Physicians must be vigilant about counseling patients on the importance of reporting postmenopausal bleeding to their physicians. Physicians should in turn have a high level of suspicion when evaluating Black women, particularly of an older age, with abnormal uterine bleeding, knowing current evaluation algorithms may offer significantly lower sensitivity for cancer in this population.

It is imperative to acknowledge the role biases, explicit or implicit, held by physicians and other healthcare providers might play in those providers’ evaluation and treatment of patients. Very little research on this subject has been done specifically in gynecologic oncology. Liang et al. detected an implicit provider prejudice against cervical cancer patients compared with ovarian cancer patients; providers associated cervical cancer, more than ovarian cancer, with feelings of anger and frustration and with high-risk patient behavior.74 The authors also found prior participation in some variation of training in cultural competency or implicit bias was associated with a less pronounced, though still present, prejudice against cervical cancer patients. Some other early evidence supports the notion that such training positively impacts patient health outcomes, though certainly additional research is warranted, specifically within the field of gynecologic cancer.75

Conclusion

It is clear there exist stark disparities between Black and White women in the incidence, severity of disease, and outcomes of gynecologic cancers. There is no one solution to this problem with multiple medical, social, and political domains. However, actively working towards acknowledging, understanding, and resolving the disparities at each point on the cancer pathway is what can and must be done. Certainly no one intervention or change in practice will do this; the culmination of thoughtful adjustments in patterns of vaccination, screening, diagnosis, and treatment of gynecologic cancers in Black women, as well as physician and other care provider acknowledgement of internal biases against patients that might impact medical decision-making, will be necessary to close the gap.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute, Grant Number P20CA233304 (to MS, DM, JK, DR). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc 2002;94(8):666–8. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12152921). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hannan EL, van Ryn M, Burke J, et al. Access to coronary artery bypass surgery by race/ethnicity and gender among patients who are appropriate for surgery. Med Care 1999;37(1):68–77. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10413394). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation--clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med 2000;343(21):1537–44, 2 p preceding 1537. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg PP, Diener-West M, Powe NR. Reducing racial disparities in transplant activation: whom should we target? Am J Kidney Dis 2001;37(5):921–31. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11325673). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ayanian JZ, Weissman JS, Chasan-Taber S, Epstein AM. Quality of care by race and gender for congestive heart failure and pneumonia. Med Care 1999;37(12):1260–9. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10599607). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: Final Data for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2018;67(1):1–55. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29775434). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaaf JM, Liem SM, Mol BW, Abu-Hanna A, Ravelli AC. Ethnic and racial disparities in the risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Perinatol 2013;30(6):433–50. DOI: 10.1055/s-0032-1326988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creanga AA, Syverson C, Seed K, Callaghan WM. Pregnancy-Related Mortality in the United States, 2011–2013. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130(2):366–373. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 9 Registries. National Cancer Institute; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin 2022;72(1):7–33. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu KH, Broaddus RR. Endometrial Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine 2020;383(21):2053–2064. DOI: 10.1056/nejmra1514010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsuo K, Ross MS, Machida H, Blake EA, Roman LD. Trends of uterine carcinosarcoma in the United States. J Gynecol Oncol 2018;29(2):e22. DOI: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Cancer Society. Cancer Statistics Center. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18 Registries. In: Institute NC, ed. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long B, Liu FW, Bristow RE. Disparities in uterine cancer epidemiology, treatment, and survival among African Americans in the United States. Gynecol Oncol 2013;130(3):652–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doll KM, Winn AN, Goff BA. Untangling the Black-White mortality gap in endometrial cancer: a cohort simulation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):324–325. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu JR, Conaway M, Rodriguez GC, Soper JT, Clarke-Pearson DL, Berchuck A. Relationship between race and interval to treatment in endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86(4 Pt 1):486–90. DOI: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00238-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doll KM, Khor S, Odem-Davis K, et al. Role of bleeding recognition and evaluation in Black-White disparities in endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;219(6):593 e1–593 e14. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2018.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madison T, Schottenfeld D, James SA, Schwartz AG, Gruber SB. Endometrial cancer: socioeconomic status and racial/ethnic differences in stage at diagnosis, treatment, and survival. Am J Public Health 2004;94(12):2104–11. DOI: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doll KM, Romano SS, Marsh EE, Robinson WR. Estimated Performance of Transvaginal Ultrasonography for Evaluation of Postmenopausal Bleeding in a Simulated Cohort of Black and White Women in the US. JAMA Oncol 2021;7(8):1158–1165. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell MA, Filiaci VL, Hensley ML, et al. Randomized Phase III Trial of Paclitaxel and Carboplatin Versus Paclitaxel and Ifosfamide in Patients With Carcinosarcoma of the Uterus or Ovary: An NRG Oncology Trial. J Clin Oncol 2022:JCO2102050. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.21.02050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohler MF, Berchuck A, Davidoff AM, et al. Overexpression and mutation of p53 in endometrial carcinoma. Cancer Res 1992;52(6):1622–7. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1540970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clifford SL, Kaminetsky CP, Cirisano FD, et al. Racial disparity in overexpression of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in stage I endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;176(6):S229–32. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9378(97)70380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santin AD, Bellone S, Siegel ER, et al. Racial differences in the overexpression of epidermal growth factor type II receptor (HER2/neu): a major prognostic indicator in uterine serous papillary cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192(3):813–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maxwell GL, Risinger JI, Hayes KA, et al. Racial disparity in the frequency of PTEN mutations, but not microsatellite instability, in advanced endometrial cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6(8):2999–3005. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10955777). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smotkin D, Nevadunsky NS, Harris K, Einstein MH, Yu Y, Goldberg GL. Histopathologic differences account for racial disparity in uterine cancer survival. Gynecol Oncol 2012;127(3):616–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman ME, Devesa SS. Analysis of racial differences in incidence, survival, and mortality for malignant tumors of the uterine corpus. Cancer 2003;98(1):176–86. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.11484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Armstrong K, Randall TC, Polsky D, Moye E, Silber JH. Racial differences in surgeons and hospitals for endometrial cancer treatment. Med Care 2011;49(2):207–14. DOI: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182019123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez VE, LeBron AMW, Chang J, Bristow RE. Racial-Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Guideline-Adherent Treatment for Endometrial Cancer. Obstet Gynecol 2021;138(1):21–31. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collins Y, Holcomb K, Chapman-Davis E, Khabele D, Farley JH. Gynecologic cancer disparities: a report from the Health Disparities Taskforce of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Gynecol Oncol 2014;133(2):353–61. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Randall TC, Armstrong K. Differences in treatment and outcome between African-American and white women with endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21(22):4200–6. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2003.01.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 21 Registries. In: Institute NC, ed. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morris CR, Sands MT, Smith LH. Ovarian cancer: predictors of early-stage diagnosis. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21(8):1203–11. DOI: 10.1007/s10552-010-9547-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Terplan M, Smith EJ, Temkin SM. Race in ovarian cancer treatment and survival: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2009;20(7):1139–50. DOI: 10.1007/s10552-009-9322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Earle CC, Schrag D, Neville BA, et al. Effect of surgeon specialty on processes of care and outcomes for ovarian cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98(3):172–80. DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djj019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGowan L, Lesher LP, Norris HJ, Barnett M. Misstaging of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 1985;65(4):568–72. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3982731). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bristow RE, Zahurak ML, Ibeanu OA. Racial disparities in ovarian cancer surgical care: a population-based analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2011;121(2):364–8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.12.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aranda MA, McGory M, Sekeris E, Maggard M, Ko C, Zingmond DS. Do racial/ethnic disparities exist in the utilization of high-volume surgeons for women with ovarian cancer? Gynecol Oncol 2008;111(2):166–72. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bristow RE, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, et al. Disparities in ovarian cancer care quality and survival according to race and socioeconomic status. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105(11):823–32. DOI: 10.1093/jnci/djt065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bristow RE, Chang J, Ziogas A, Campos B, Chavez LR, Anton-Culver H. Sociodemographic disparities in advanced ovarian cancer survival and adherence to treatment guidelines. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(4):833–842. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parham G, Phillips JL, Hicks ML, et al. The National Cancer Data Base report on malignant epithelial ovarian carcinoma in African-American women. Cancer 1997;80(4):816–26. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9264366). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matthews BJ, Qureshi MM, Fiascone SJ, et al. Racial disparities in non-recommendation of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II-III ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2022;164(1):27–33. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.10.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wright J, Doan T, McBride R, Jacobson J, Hershman D. Variability in chemotherapy delivery for elderly women with advanced stage ovarian cancer and its impact on survival. Br J Cancer 2008;98(7):1197–203. DOI: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bandera EV, Lee VS, Rodriguez-Rodriguez L, Powell CB, Kushi LH. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Ovarian Cancer Treatment and Survival. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22(23):5909–5914. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Vital Statistics System. 2020. ed2020.

- 46.del Carmen MG, Montz FJ, Bristow RE, Bovicelli A, Cornelison T, Trimble E. Ethnic differences in patterns of care of stage 1A(1) and stage 1A(2) cervical cancer: a SEER database study. Gynecol Oncol 1999;75(1):113–7. DOI: 10.1006/gyno.1999.5543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harper DM, DeMars LR. HPV vaccines - A review of the first decade. Gynecol Oncol 2017;146(1):196–204. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spencer JC, Calo WA, Brewer NT. Disparities and reverse disparities in HPV vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2019;123:197–203. DOI: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeudin P, Liveright E, Del Carmen MG, Perkins RB. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting human papillomavirus vaccination rates. Clin Ther 2014;36(1):24–37. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White A, Thompson TD, White MC, et al. Cancer Screening Test Use - United States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(8):201–206. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6608a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buskwofie A, David-West G, Clare CA. A Review of Cervical Cancer: Incidence and Disparities. J Natl Med Assoc 2020;112(2):229–232. DOI: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Benard VB, Lawson HW, Eheman CR, Anderson C, Helsel W. Adherence to guidelines for follow-up of low-grade cytologic abnormalities among medically underserved women. Obstet Gynecol 2005;105(6):1323–8. DOI: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000159549.56601.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tabnak F, Muller HG, Wang JL, Zhang W, Howell LP. Timeliness and follow-up patterns of cervical cancer detection in a cohort of medically underserved California women. Cancer Causes Control 2010;21(3):411–20. DOI: 10.1007/s10552-009-9473-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cham S, Li A, Rauh-Hain JA, et al. Association Between Neighborhood Socioeconomic Inequality and Cervical Cancer Incidence Rates in New York City. JAMA Oncology 2021. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.5779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matz M, Weir HK, Alkhalawi E, Coleman MP, Allemani C, Group UCW. Disparities in cervical cancer survival in the United States by race and stage at diagnosis: An analysis of 138,883 women diagnosed between 2001 and 2014 (CONCORD-3). Gynecol Oncol 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fleming S, Schluterman NH, Tracy JK, Temkin SM. Black and white women in Maryland receive different treatment for cervical cancer. PLoS One 2014;9(8):e104344. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramey SJ, Asher D, Kwon D, et al. Delays in definitive cervical cancer treatment: An analysis of disparities and overall survival impact. Gynecol Oncol 2018;149(1):53–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boyce-Fappiano D, Nguyen KA, Gjyshi O, et al. Socioeconomic and Racial Determinants of Brachytherapy Utilization for Cervical Cancer: Concerns for Widening Disparities. JCO Oncol Pract 2021;17(12):e1958–e1967. DOI: 10.1200/OP.21.00291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bruce SF, Joshi TV, Chervoneva I, et al. Disparities Among Cervical Cancer Patients Receiving Brachytherapy. Obstet Gynecol 2019;134(3):559–569. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alimena S, Yang DD, Melamed A, et al. Racial disparities in brachytherapy administration and survival in women with locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2019;154(3):595–601. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Petersen SS, Doe S, Buekers T. Definitive radiation therapy for cervical cancer: Non-white race and public insurance are risk factors for delayed completion, a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol Rep 2018;25:102–105. DOI: 10.1016/j.gore.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scalici J, Finan MA, Black J, et al. Minority participation in Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) Studies. Gynecol Oncol 2015;138(2):441–4. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Kressin NR, et al. The Tuskegee Legacy Project: willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2006;17(4):698–715. DOI: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Katz RV, Green BL, Kressin NR, Claudio C, Wang MQ, Russell SL. Willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical studies: confirmatory findings from a follow-up study using the Tuskegee Legacy Project Questionnaire. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99(9):1052–60. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17913117). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Niranjan SJ, Martin MY, Fouad MN, et al. Bias and stereotyping among research and clinical professionals: Perspectives on minority recruitment for oncology clinical trials. Cancer 2020;126(9):1958–1968. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.32755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Farley JH, Tian C, Rose GS, Brown CL, Birrer M, Maxwell GL. Race does not impact outcome for advanced ovarian cancer patients treated with cisplatin/paclitaxel: an analysis of Gynecologic Oncology Group trials. Cancer 2009;115(18):4210–7. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.24482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Farley JH, Hines JF, Taylor RR, et al. Equal care ensures equal survival for African-American women with cervical carcinoma. Cancer 2001;91(4):869–73. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11241257). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Maxwell GL, Tian C, Risinger J, et al. Racial disparity in survival among patients with advanced/recurrent endometrial adenocarcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 2006;107(9):2197–205. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.22232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maxwell GL, Tian C, Risinger JI, Hamilton CA, Barakat RR, Gynecologic Oncology Group S. Racial disparities in recurrence among patients with early-stage endometrial cancer: is recurrence increased in black patients who receive estrogen replacement therapy? Cancer 2008;113(6):1431–7. DOI: 10.1002/cncr.23717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Park AB, Darcy KM, Tian C, et al. Racial disparities in survival among women with endometrial cancer in an equal access system. Gynecol Oncol 2021;163(1):125–129. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Huang AB, Huang Y, Hur C, et al. Impact of quality of care on racial disparities in survival for endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020;223(3):396 e1–396 e13. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rauh-Hain JA, Buskwofie A, Clemmer J, Boruta DM, Schorge JO, Del Carmen MG. Racial disparities in treatment of high-grade endometrial cancer in the Medicare population. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125(4):843–851. DOI: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Global strategy to accelerate the elimination of cervical cancer as a public health problem. Geneva: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liang J, Wolsiefer K, Zestcott CA, Chase D, Stone J. Implicit bias toward cervical cancer: Provider and training differences. Gynecol Oncol 2019;153(1):80–86. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Torres TK, Chase DM, Salani R, Hamann HA, Stone J. Implicit biases in healthcare: implications and future directions for gynecologic oncology. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.12.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]