Abstract

Introduction:

Tobacco-free oral nicotine products (ONPs) are an emerging class of non-combustible nicotine products. ONP sales have increased since 2016, though little research has investigated consumer awareness, use, or correlates of ONP use. The purpose of this analysis was to assess prevalence and correlates of ONP awareness and use.

Methods:

This paper is a cross-sectional analysis of 2,507 U.S. participants from Wave 3 (February–June 2020) of the International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, a population-based survey of current and former cigarette smokers and nicotine vaping product (NVP) users in the U.S. ONP awareness and use prevalence was compared to heated tobacco products. Analyses conducted in late 2021 assessed correlates of ONP awareness and use such as demographic characteristics, tobacco use (cigarettes, NVPs, smokeless tobacco), and tobacco quit attempts.

Results:

Almost 1 in 5 respondents claimed to have heard of ONPs, 3.0% reported ever use, and 0.9% were current users, all of which were lower than for heated tobacco products. Ever use of ONP was more common among younger adults (e.g., 18–24 years), males, and current users of smokeless tobacco. ONP prevalence was higher among those who reported having made attempts to stop smoking or vaping.

Conclusions:

ONP use was low among current and former smokers and NVP users. ONP users were demographically similar to individuals who smoke/vape and also use smokeless tobacco. Future studies are needed to understand emerging ONPs, particularly whether they are being used as product supplements (dual use), replacements (switching), or cessation aids (quitting).

INTRODUCTION

Modern oral nicotine products (ONPs) are an emerging class of non-combustible nicotine products. These products include both pouches and lozenges and are intended for oral consumption similar to snus or nicotine replacement therapy lozenges. ONPs differ from traditional smokeless tobacco products (SLT) because they do not contain any tobacco leaf. ONPs come in a variety of nicotine concentrations and flavors, and some manufacturers claim to use ‘pharmaceutical-grade’ nicotine (e.g., synthetic) while others use tobacco-derived nicotine.1 The use of synthetic nicotine was expected to create regulatory challenges for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products, which has the authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing, and distribution of tobacco products (e.g., containing tobacco or tobacco-derived nicotine).2 However, President Biden signed H.R. 2471 on March 15, 2022, that will allow the U.S. FDA to regulate tobacco products containing nicotine from any source (including synthetic nicotine) effective on April 14, 2022.3 ONPs are marketed for use anywhere and as alternatives to other tobacco products that are restricted in public places.4 Because ONPs do not burn tobacco or involve inhalation of chemicals into the airway, they are potentially less harmful products compared to cigarettes, other combusted tobacco products, and perhaps nicotine vaping products (NVPs) and heated tobacco products (HTPs). Laboratory studies of ONPs show that they have a similar pharmacokinetic profile to existing smokeless tobacco products5 and may have lower abuse liability than cigarettes.6–8 These products also may contain low levels of toxicants, with a toxicant profile similar to nicotine replacement therapies.9

Popular brands of ONPs include ZYN (Swedish Match), On! (Altria), and Velo (Reynolds American). In addition, several new brands of ONPs have recently appeared in the marketplace, both at retail and online (i.e., NIIN, Frē, Lucy, Rogue). Modern ONPs were first test marketed in Colorado in 2014 (ZYN), became more widely available in 2016, and captured 4% of the smokeless tobacco market by 2019,10 suggesting their increased popularity. Indeed, pouch sales had reached at least $216,886,819 by June 2020 (per Nielsen data).11 Despite growth in the modern ONP market, limited research has assessed use prevalence and correlates in population surveys.

A small body of literature exists regarding prevalence, use patterns, and potential health effects of modern ONPs. One report from the International Tobacco Control survey found that 0.7% of U.S. adults who currently smoke and recent former smokers had used ONPs in the past month.12 A survey of current and former smokers and vapers in the UK estimates that 15.9% had heard of ONPs and 2.7% currently used them.13 However, less is known about who is using ONPs and how they are being used, particularly in the U.S. A recent study reported on a panel of ZYN-naïve consumers and ZYN users.14 Among naïve consumers, ZYN was attractive to a majority of SLT and dual cigarette-SLT users, but a minority of never and former tobacco users. The ZYN user panel consisted mostly of former tobacco users and current SLT users. ZYN users reported using the product to help quit/reduce cigarette smoking, reduce harm to health, and for ease/discretion of use. Most ZYN users were daily users and preferred mint/wintergreen flavors in the higher nicotine content. When asked about reasons for using ONPs, ‘to help quit tobacco use’ was a commonly reported reason; therefore, it is assessed in this study as well.

The purpose of this study was to report the level of awareness and use of ONPs and correlates of awareness and use among current and former smokers and vapers in the U.S. in 2020. Additionally, an aim in this paper was to assess correlates, such as sociodemographics and tobacco use characteristics, of awareness and lifetime use of ONPs.

METHODS

Study Sample

The data for this paper come from the 2020 International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey Wave 3 (ITC-4CV3)15 conducted in the U.S. between February–June 2020.16 The online survey sample consisted of (1) recontact smokers, former smokers, and vapers who had participated in Wave 2; and (2) newly recruited current smokers, former smokers, current vapers, and HTP users from country-specific panels. Participants were recruited from Canada, England, the U.S., and Australia. Methodological details for each country are available via the ITC website (https://itcproject.org/methods) and also in the paper by Thompson et al. 2019.17 The full cross-sectional sample consisted of 11,522 respondents. All participants consented to participate and survey protocols and materials were cleared by appropriate ethics boards.

The sample for this paper is limited to U.S. adults who are current or former cigarette smokers or vapers (n=2,507). No respondents in the sample are never tobacco users. This sample differs from that of Li et al. (2021)12 by including individuals with NVP experience, rather than only current and recent former smokers. Demographic and tobacco use characteristics for the sample are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Weighted Sample Characteristics (%) and Prevalence of Awareness, Lifetime Use, and Current Use of ONPs (%) by Sample Characteristics

| ONP prevalence |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total (%) | Awareness (%) | p-value | Lifetime use (%) | p-value | Current use (%) | p-value |

|

| |||||||

| Age, years | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| 18–24a | 10.0 | 28.3 | 7.2 | 2.3 | |||

| 25–39 | 32.8 | 20.5 | 4.4 | 1.5 | |||

| 40–54 | 27.3 | 20.8 | 1.9 | 0.3 | |||

| ≥55 | 29.9 | 13.1 | 0.4 | 0.0 | |||

| Sex | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.015 | ||||

| Male | 56.1 | 21.0 | 4.2 | 1.1 | |||

| Female | 43.9 | 17.3 | 1.3 | 0.5 | |||

| Income | 0.007 | <0.001 | 0.066 | ||||

| Low | 48.3 | 17.1 | 2.0 | 0.7 | |||

| Moderate | 34.9 | 19.8 | 2.2 | 0.6 | |||

| High | 16.8 | 21.2 | 4.4 | 1.3 | |||

| Education | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Low | 48.3 | 17.2 | 2.0 | 0.5 | |||

| Moderate | 34.9 | 20.9 | 2.7 | 0.6 | |||

| High | 16.8 | 22.6 | 6.0 | 2.5 | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.20 | 0.81 | 0.96 | ||||

| White | 70.9 | 18.7 | 2.9 | 0.8 | |||

| Nonwhiteb | 29.1 | 20.4 | 3.0 | 0.8 | |||

| Smoke/Vape status | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Exclusively smoke | 58.9 | 17.4 | 2.1 | 0.2 | |||

| Exclusively vape | 11.0 | 29.7 | 2.4 | 0.7 | |||

| Dual use | 11.5 | 30.2 | 9.6 | 4.5 | |||

| Non-current | 18.6 | 13.8 | 1.9 | 0.8 | |||

| SLT use past 30 days | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 3.7 | 40.3 | 21.0 | 13.3 | |||

| No | 96.3 | 18.5 | 2.3 | 0.4 | |||

Notes: p-values for Pearson chi-square tests indicated in italics.

4.0% of sample was 18‒20 years of age.

Nonwhite ethnicity prevalence: Black Non-Hispanic (14.0%); Other Non-Hispanic (2.4%); Hispanic (9.0%); Multiple Races Non-Hispanic (3.6%).

ONP, oral nicotine product; SLT, smokeless tobacco.

Measures

ONPs were described in the survey with the statement “There are tobacco-free nicotine pouches or pods that you put into your mouth, sometimes called ‘white pouches’ (e.g., Zyn, On!, Verv, Dryft, Lyft, Skruf). These products do NOT contain tobacco; they are smokeless and spit-free.” Participants were then asked if they had heard of ONPs (awareness), ever used (lifetime use), and used in the past 30 days (current use). Current ONP users also were asked about their frequency of use.

HTP awareness was used as a comparator for ONP. HTPs were described as “Heated tobacco products (HTPs, or heat-not-burn products) heat ACTUAL TOBACCO to create an aerosol that is inhaled.” Similar questions to ONPs were asked to assess awareness, lifetime use, and current use of HTPs.

Participants were asked about their age, sex, ethnicity, education, and income. Age was categorized as 18–24, 25–39, 40–54, and ≥55 years. Sex was a derived variable that is dichotomized as male or female based on self-reported sex and gender identity. Ethnicity was a derived variable that dichotomized as White or non-White. Education was categorized into 3 levels: low (≤high school), moderate (technical/community college, some university), or high (>university degree). Income was categorized into 3 levels based on annual income: low (≤$29,999), moderate ($30,000-$59,999), and high (≥$60,000).

Cigarette smoking and NVP use were categorized as current use (daily or nondaily), or nonuse (former or never). Nondaily use for both products included weekly, monthly, or less than monthly product users). Former smokers reported smoking ≥100 lifetime cigarettes and having quit smoking completely. Former vapers reported previous NVP use occasionally or at least weekly. Never smokers reported having smoked <100 lifetime cigarettes and never vapers reported trying NVPs 1 or fewer times. The current sample did not include never users of both cigarettes and NVPs. Current use and nonuse of cigarettes and NVPs were combined to create a single variable for Smoking/Vaping Status, with categories of exclusive smokers (current cigarette and NVP nonuse), exclusive vapers (cigarettes nonuse and current NVP), dual users (current cigarette and current NVP) or non-current users (cigarettes and NVP nonuse).

SLT use was dichotomized as current (past 30-day use) or non-user (no past 30-day use).

Those who reported current smoking or vaping were asked separate questions about their quit attempts and interest. Quit attempts were dichotomized as whether a smoker/vaper reported attempting to quit in the past 24 months (i.e., since the previous wave). Quit interest was asked differently to those who smoked and vaped, but both were categorized into interested, unsure, or uninterested. For those who smoked, quit interest was categorized as interested (plan to quit in next month or 1–6 months), unsure (sometime in future beyond 6 months) or uninterested (no plans to quit). For those who vaped, quit interest was categorized as interested (probably or definitely plan to stop vaping in the foreseeable future), unsure (might or might not continue), or uninterested (probably or definitely continue).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were weighted to the ‘rescaled cross-sectional weight for all – main sample.’ Variance was estimated using Taylor Series Linearization. All survey items included refused and don’t know response options that were treated as missing in analyses. Pearson’s chi-squared analyses were used to test for unadjusted differences in the prevalence of awareness, lifetime use, and current use of ONPs by demographic characteristics, smoking/vaping status, and quit variables. Binary logistic regressions were used to assess correlates of ONP awareness and lifetime use (current use excluded due to low prevalence). Predictor variables included age group (ref= ≥55), gender (ref=female), income (ref=high), education (ref=high), ethnicity (ref=non-White), smoking/vaping status (ref=non-current user), and SLT use (ref=no). Cases with missing data for regressions were deleted listwise. Tests were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Analyses were conducted in Stata 17 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

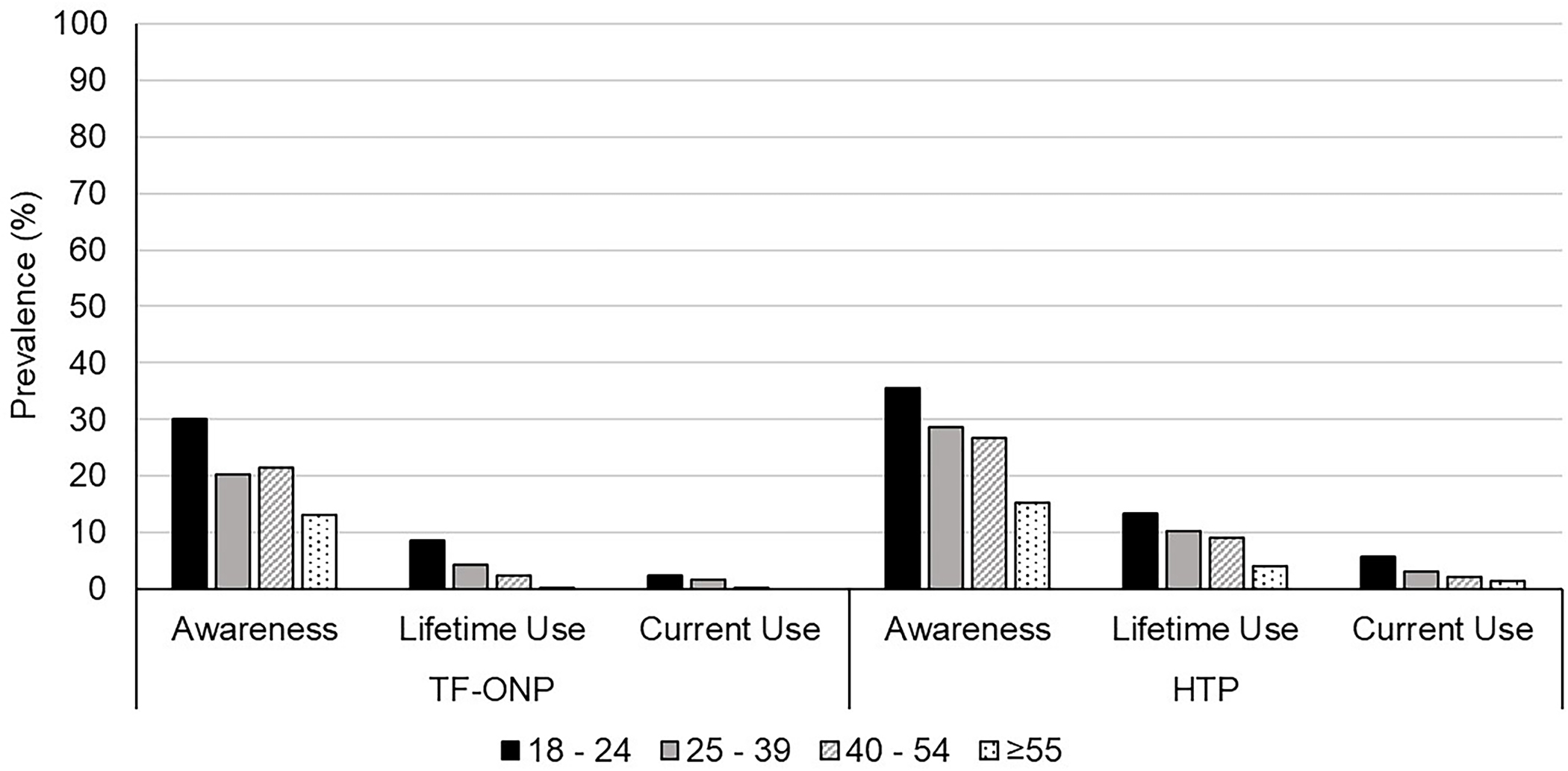

Figure 1 depicts awareness and use prevalence of ONPs and HTPs by age group. Awareness of ONPs and HTPs were 19.5% and 24.8% of the sample, respectively. Lifetime use was 3.0% for ONPs and 8.4% for HTPs. Current use was 0.9% for ONPs and 2.5% for HTPs Generally, awareness and use were higher among younger ages than older ages for both products. Among current ONP users, 65.1% reported daily use, 16.5% weekly use, and 18.5% less than weekly use.

Figure 1.

Weighted awareness, lifetime use, and current use prevalence (%) for tobacco free oral nicotine products (ONPs) and heated tobacco products (HTPs) among those who currently and formerly smoke and vape by age group.

Table 1 shows the unadjusted prevalence of ONP awareness, lifetime use, and current use by demographic characteristics and tobacco use status. Table 2 summarizes the multivariable models exploring correlates of ONP awareness and ever use. There were increased odds of ONP awareness for 18–24 year olds (OR=2.28, 95% CI=1.51, 3.45) and 40–54 year olds (OR=1.62, 95% CI=1.13, 2.32) compared to ≥55 years (OR=1.46, 2.28), exclusive vapers (OR=2.49, 95% CI=1.35, 4.59) and dual users (OR=2.75, 95% CI=1.50, 5.05) compared to non-current users, and current SLT users (OR=2.29, 95% CI=1.30, 4.00). No significant effects were observed for gender, income, education, or ethnicity.

Table 2.

Weighted Logistic Regressions to Predict ONP Awareness and Lifetime Use

| ONP awareness | ONP lifetime use | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Predictors | AOR (95% CI) | p-value | AOR (95% CI) | p-value |

|

| ||||

| Age group, years | ||||

| 18‒24 | 2.28 (1.51, 3.45) | <0.001 | 31.21 (9.24, 105.41) | <0.001 |

| 25‒39 | 1.46 (0.99, 2.15) | 0.055 | 14.69 (4.32, 49.96) | <0.001 |

| 40‒54 | 1.62 (1.13, 2.32) | 0.008 | 7.39 (2.18, 25.05) | 0.001 |

| ≥55 | ref | ref | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.22 (0.91, 1.66) | 0.18 | 3.61 (1.85, 7.02) | <0.001 |

| Female | ref | ref | ||

| Income | ||||

| Low | 0.83 (0.59, 1.20) | 0.33 | 0.74 (0.32, 1.70) | 0.48 |

| Moderate | 1.06 (0.74, 1.52) | 0.74 | 0.76 (0.32, 1.81) | 0.53 |

| High | ref | ref | ||

| Education | ||||

| Low | 0.73 (0.49, 1.09) | 0.12 | 0.32 (0.14, 0.73) | 0.007 |

| Moderate | 0.92 (0.64, 1.32) | 0.64 | 0.36 (0.14, 0.91) | 0.03 |

| High | ref | ref | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1.01 (0.71, 1.43) | 0.94 | 1.22 (0.60, 2.48) | 0.56 |

| Nonwhite | ref | ref | ||

| Smoke/Vape status | ||||

| Exclusively smoke | 1.59 (0.90, 2.80) | 0.11 | 1.46 (0.33, 6.49) | 0.62 |

| Exclusively vape | 2.49 (1.35, 4.59) | 0.003 | 0.72 (0.13, 4.04) | 0.72 |

| Dual use | 2.75 (1.50, 5.05) | 0.001 | 3.85 (0.83, 17.83) | 0.085 |

| Non-current | ref | ref | ||

| SLT use | ||||

| Yes | 2.29 (1.30, 4.00) | <0.001 | 5.35 (2.41, 11.87) | <0.001 |

| No | ref | |||

Note: Boldface indicated statistical significance (p<0.05).

ONP, oral nicotine product; SLT, smokeless tobacco.

There were increased odds of ONP lifetime use for all age groups compared to ≥55 years (OR range=7.39–31.21), males (OR=3.61, 95% CI=1.85, 7.02), and current SLT users (OR=5.35, 95% CI=2.41, 11.87). Reduced odds of ONP lifetime use were associated with low (OR=0.32, 95% CI=0.14, 0.73) and moderate education (OR=0.36, 95% CI=0.14, 0.91) compared to high. No significant effects were observed for income or ethnicity.

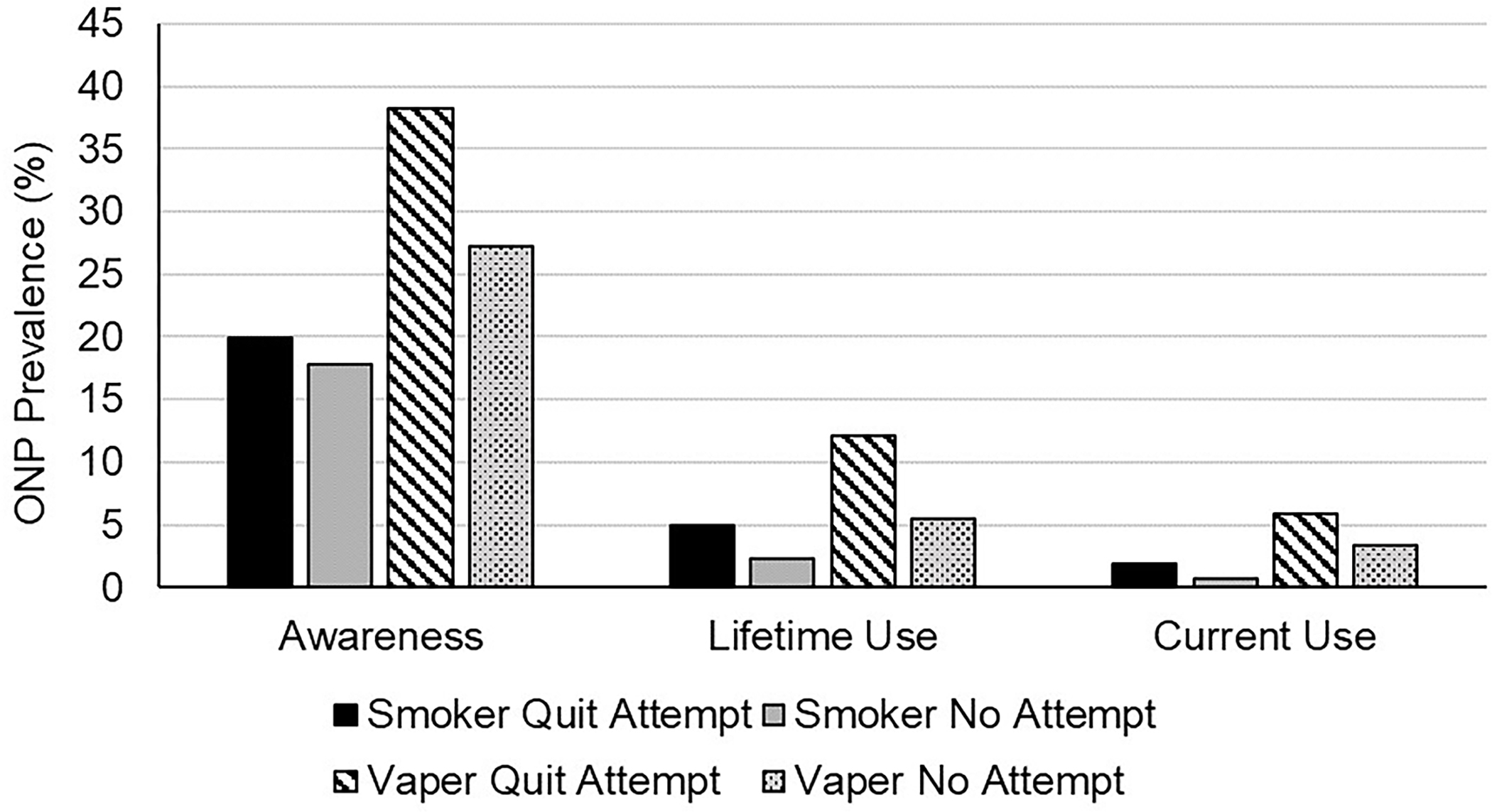

Figure 2 depicts ONP awareness and use for smokers and vapers who did and did not make quit attempts in the past 2 years. ONP awareness did not differ by smokers who did versus did not attempt to quit (p=0.32), though prevalence was higher among those who made a quit attempt for both lifetime use (4.9% vs 2.3%, p=0.008) and current use (1.9% vs 0.7%, p=0.043). However, no smokers who successfully quit cigarettes in the past 2 years were currently using ONPs. ONP awareness differed between NVP users who did (38.3%) versus did not (27.2%) attempt to quit (p=0.015). A similar trend was observed for lifetime use (12.1% vs 5.4%, p=0.01), but not significantly for current use (p=0.25).

Figure 2.

ONP awareness, lifetime use, and current use prevalence (%) for those who smoke and vape who did and did not make a quit attempt in the past 24 months.

ONP, oral nicotine products.

ONP awareness did not differ based on interest in quitting smoking (p=0.61). However, ONP lifetime use was highest among smokers interested in quitting (5.5%), followed by unsure (3.2%), and uninterested (1.9%, p=0.012). Current ONP use did not differ by smoker quit interest (p=0.18). This pattern of results differed for vapers. ONP awareness was highest in vapers uninterested in quitting (37.0%) followed by those who were interested (27.2%) and unsure (23.6%, p=0.016). Lifetime ONP use followed this same pattern, being highest among vapers uninterested in quitting (10.0%) followed by interested (6.6%) and unsure (2.7%, p=0.026). Current ONP use was highest among vapers uninterested in quitting (7.2%) followed by unsure (1.7%) and interested in quitting (1.5%, p=0.016).

DISCUSSION

Among U.S. adults with a history of smoking and/or vaping, almost one-fifth were aware of ONPs, though lifetime use was 3% and current use was below 1%. These estimates are similar to results among current and recent former smokers in the U.S.,12,18 though lifetime prevalence was lower in the ITC sample others have reported.18 Prevalence was also similar to other countries with commercially available ONPs such as the Netherlands19 and the UK,13 though prevalence of current use among smokers and vapers in the U.S. (0.9%) was lower than in the UK (2.7%). ONPs are increasing in unit sales11 and taking an increasing share of the SLT market,10 and though use prevalence remains low among those who exclusively smoke or vape, it was much more common among dual users and current SLT users in the current sample. ONP awareness was slightly lower than HTP awareness, though lifetime use was substantially lower. Most current ONP users were daily users, as observed in a previous ZYN consumer panel.14

Several demographic trends in ONP awareness and use were observed. ONP awareness or use were more prevalent among younger age groups and men, which is consistent with a previous consumer panel of ZYN users14 and other surveys of tobacco users.13,18 These results also mirror the primary demographic profile of smokeless tobacco users,20–21 suggesting that ONPs may be appealing to similar groups as SLT. This consistency between ONPs and SLT users is reinforced by higher awareness and use of ONPs by SLT users compared to nonusers, which again is consistent with previous survey research.14,18 However, in contrast to other tobacco products, ONP use was associated with individuals who have higher income and education, as observed in similar surveys outside of the U.S.13,19; though, one survey of people who smoke in the U.S. found the opposite pattern for education.18 Many who smoke are misinformed about the relative safety of SLT,22 though smokers with higher education better understand the relative safety of SLT.23 Thus, higher education may be associated with a better understanding of the tobacco ‘continuum of harm’, for which ONPs likely lay on the lower end.9

ONP awareness and use were much more prevalent among dual users (i.e., cigarettes and NVPs) compared to exclusive users and non-current users, as seen in a UK survey,13 though the association with lifetime ONP use did not remain in adjusted models. This pattern may reflect the increasing prevalence of polytobacco use in the U.S.,20 which is particularly common among NVP users24 and pouched SLT users.21 Exclusive smokers had the lowest prevalence of ONP use, leading to questions about the appeal of ONPs to regular smokers. It is possible that ONPs may mimic the trajectory of snus in the U.S., which has been an unsuccessful cigarette substitute25 and regular adoption remains low.26–28 Indeed, poor adoption also was observed with previous dissolvables,29 such as Camel sticks, strips, and orbs. However, these products may still be adopted by polytobacco and SLT users. The extent to which ONPs replace versus supplement other tobacco products is essential to determining their public health impact.

ONP use prevalence was higher among those who smoke and vape who had made a quit attempt in the past 2 years, supporting reports of ONP use to reduce/quit smoking14 and consistent with findings that interest in ONPs was higher among smokers who planned to quit within 6 months.18 ONP use also was higher among smokers interested in quitting, but interestingly, the opposite pattern was found for vapers. This finding could suggest that some people who smoke are seeking a less harmful alternative when trying to quit,14 while people who vape who are not planning to quit may be more inclined to engage in dual/poly use with ONPs. Indeed, dual users had the highest prevalence of ONP use in this sample. Future research should continue to parse apart ONP perceptions and reasons for use among users of different tobacco products.

Limitations

The current study was limited to simple assessments of awareness and use of ONPs in the U.S. Self-reporting product use is a potential limitation that may lead to misclassification, particularly if consumers were not aware of certain brand names (e.g., Lyft, Skruf are not common brands in the U.S.), or mistook ONPs for other variants of SLT. An important limitation of this study is that the sample consists of adults with a history of smoking and/or vaping, so use among youth and non-tobacco users is unknown. Additionally, the cross-sectional approach limits the ability to assess changes over time and to what extent these products are being used as a tobacco product replacement, supplement, or cessation aid. How tobacco and non-tobacco users are using ONPs is an essential question to assess the public health impact of ONPs.

CONCLUSIONS

Ever use of ONPs was more common among younger adults (e.g., 18–24 years), males, dual cigarette/NVP users, and current users of SLT. ONPs appear to be growing in popularity, thus future research should continue to monitor consumer awareness. It will be important to monitor ONP use by people who smoke, who may benefit from them as cigarette substitutes, and non-tobacco users, for whom use should be discouraged. Research is needed to study these products more comprehensively, measuring use behaviors and characteristics such as brand, form (pouch vs lozenge), flavor, nicotine content, and pH. Continued market and survey research are necessary to understand the proliferation of these emerging products, including their global impact outside of the U.S. Additionally, independent studies are needed to assess ONP abuse liability, substitutability for other tobacco products, and the degree to which it influences smoking and/or vaping cessation or leads to dual use. There also is a need for understanding the toxicological profile and health effects of these products, particularly among tobacco users who replace or supplement with ONPs. While the current prevalence of ONPs remains relatively low, the market is growing, and tobacco regulatory scientists should begin addressing these research questions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The survey protocols and all materials of Wave 3 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, including the survey questionnaires, were cleared for ethics by Office of Research Ethics, University of Waterloo, Canada (ORE#20803/30570, ORE#21609/30878); Research Ethics Office, King’s College London, UK (RESCM-17/18–2240); Human Research Ethics, Cancer Council Victoria, Australia (HREC1603) and, Human Ethics, Research Management Office, University of Queensland, Australia (2016000330/HREC1603); and IRB Medical University of South Carolina (waived due to minimal risk). All participants provided consent to participate.

The ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey was supported by grants from the U.S. National Cancer Institute (P01 CA200512).

Maciej L. Goniewicz has received a research grant from Pfizer and served on a scientific advisory board to Johnson & Johnson, pharmaceutical companies that manufacture smoking cessation medications. Geoffrey T. Fong has served as an expert witness or consultant on behalf of governments in litigation involving the tobacco industry. K. Michael Cummings serves as a paid expert witness in litigation filed against cigarette manufacturers. No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robichaud MO, Seidenberg AB, Byron MJ. Tobacco companies introduce ‘tobacco-free’ nicotine pouches. Tob Control. 2020;29:e145–e146. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.HHS, Food and Drug Administration. Deeming Tobacco Products To Be Subject to the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as Amended by the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (2016). 81 FR 28973. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/rules-regulations-and-guidance/fdas-deeming-regulations-e-cigarettes-cigars-and-all-other-tobacco-products. Published September 1, 2021. Accessed May 3, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. New law clarifies FDA authority to regulate synthetic nicotine. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USFDA/bulletins/30f82ff. Accessed April 11, 2022.

- 4.Czaplicki L, Patel M, Rahman B, Yoon S, Schillo B, Rose SW. Oral nicotine marketing claims in direct-mail advertising. Tob Control. In press. Online May 6, 2021. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunell E, Fagerstrom K, Hughes J, Pendrill R. Pharmacokinetic comparison of a novel non-tobacco-based nicotine pouch (ZYN) with conventional, tobacco-based Swedish snus and American moist snuff. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(10):1757–1763. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J, Wang J, Vansickel A, Edmiston J, Graff D, Sarkar M. Characterization of the abuse potential in adult smokers of a novel oral tobacco product relative to combustible cigarettes and nicotine polacrilex gum. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2021;10(3):241–250. 10.1002/cpdd.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rensch J, Liu J, Wang J, Vansickel A, Edmiston J, Sarkar M. Nicotine pharmacokinetics and subjective response among adult smokers using different flavors on on! nicotine pouches compared to combustible cigarettes. Psychopharmacology. 2021;238(11):3325–3334. 10.1007/s00213-021-05948-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McEwan M, Azzopardi D, Gale N, et al. A randomized study to investigate the nicotine pharmacokinetics of oral nicotine pouches and a combustible cigarette. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2022;47(2):211–221. 10.1007/s13318-021-00742-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azzopardi D, Liu C, Murphy J. Chemical characterization of tobacco-free “modern” oral nicotine pouches and their position on the toxicant and risk continuums. Drug Chem Toxicol. In press. Online May 25, 2021. 10.1080/01480545.2021.1925691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Miller Lo EJ, Wackowski OA. Examining market trends in smokeless tobacco sales in the United States: 2011–2019. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;ntaa239. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marynak KL, Wang X, Borowiecki M, et al. Nicotine pouch unit sales in the US, 2016–2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;326(6):566–568. 10.1001/jama.2021.10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li L, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Patterns of non-cigarette tobacco and nicotine use among current cigarette smokers and recent quitters: findings from the 2020 ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23(9):1611–1616. 10.1093/ntr/ntab040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brose LS, McDermott MS, McNeill A. Heated tobacco products and nicotine pouches: a survey of people with experience of smoking and/or vaping in the UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8852. 10.3390/ijerph18168852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Plurphanswat N, Hughes JR, Fagerstrom K, Rodu B. Initial information on a novel nicotine product. Am J Addict. 2020;29(4):279–286. 10.1111/ajad.13020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.ITC Project. (2020, October). ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, Wave 3 (4CV3, 2020) Preliminary Technical Report. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, United States; Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the University of Queensland, Australia; King’s College London, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, Hastings G, Hyland A, Giovino GA, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control. 2006;15(suppl 3):iii3–iii11. 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Boudreau C, et al. Methods of the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, Wave 1 (2016). Addiction. 2019;114(suppl 1):6–14. 10.1111/add.14528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hrywna M, Gonsalves NJ, Delnevo CD, Wackowski OA. Nicotine pouch product awareness, interest and ever use among US adults who smoke, 2021. Tob Control. In press. Online February 25, 2022. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-057156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havermans A, Pennings JLA, Hegger I, et al. Awareness, use and perceptions of cigarillos, heated tobacco products and nicotine pouches: a survey among Dutch adolescents and adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;229(Pt B):109136. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cornelius ME, Wang TW, Jamal A, Loretan CG, Neff LJ. Tobacco product use among adults - United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(46):1736–1742. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng YC, Rostron BL, Day HR, Stanton CA, Hull LC, Persoskie A, et al. Patterns of use of smokeless tobacco in US adults, 2013–2014. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(9):1508–1514. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borland R, Cooper J, McNeill A, O’Connor R, Cummings KM. Trends in beliefs about the harmfulness and use of stop-smoking medications and smokeless tobacco products among cigarette smokers: findings from the ITC four-country survey. Harm Reduct J. 2011;8:21. 10.1186/1477-7517-8-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Connor RJ, Hyland A, Giovino GA, Fong GT, Cummings KM. Smoker awareness of and beliefs about supposedly less-harmful tobacco products. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(2):85–90. 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanton CA, Sharma E, Edwards KC et al. Longitudinal transitions of exclusive and polytobacco electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use among youth, young adults, and adults in the USA: findings from the PATH Study Waves 1–3 (2013–2016). Tob Control. 2020;29(suppl 3):s147–s154. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatsukami DK, Severson H, Anderson A, et al. Randomised clinical trial of snus versus medicinal nicotine among smokers interested in product switching. Tob Control. 2016;25:267–274. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biener L, Roman AM, McInerney SA, et al. Snus use and rejection in the USA. Tob Control. 2016;25(4):386–392. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burris JL, Wahlquist AE, Alberg AJ, et al. A longitudinal, naturalistic study of U.S. smokers’ trial and adoption of snus. Addict Behav. 2016;63:82–88. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carpenter MJ, Wahlquist AE, Burris JL, et al. Snus undermines quit attempts but not abstinence: a randomised clinical trial among US smokers. Tob Control. 2017;26(2):202–209. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regan AK, Dube SR, Arrazola R. Smokeless and flavored tobacco products in the U.S.: 2009 Styles survey results. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(1):29–36. 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]