Abstract

Processivity clamps tether DNA polymerases to DNA, allowing their access to the primer-template junction. In addition to DNA replication, DNA polymerases also participate in various genome maintenance activities including translesion synthesis (TLS). However, due to the error-prone nature of TLS polymerases, their association with clamps must be tightly regulated. Here we show that fork-associated ssDNA binding protein (SSB) selectively enriches the bacterial TLS polymerase Pol IV at stalled replication forks. This enrichment enables Pol IV to associate with the processivity clamp and is required for TLS on both the leading and lagging strands. In contrast, clamp-interacting proteins (CLIPs) lacking SSB binding are spatially segregated from the replication fork, minimally interfering with Pol IV-mediated TLS. We propose that stalling-dependent structural changes within clusters of fork-associated SSB establish hierarchical access to the processivity clamp. This mechanism prioritizes a subset of CLIPs with SSB-binding activity and facilitates their exchange at the replication fork.

Editor summary:

E. coli SSB enriches Pol IV polymerase at lesion-stalled replication forks, promoting TLS. Loss of this enrichment increases repriming of DNA synthesis, revealing a pivotal role of SSB in the pathway choice of stalled replication forks.

Introduction

Cells use a host of factors to either tolerate or repair DNA damage. However, inappropriate use of these factors can cause genome instability. During translesion synthesis (TLS), a damage tolerance mechanism, TLS polymerases extend primers past DNA lesions that block replicative polymerases1. Given their low replication fidelity, access of TLS polymerases to the primer-template (P/T) junction must be tightly regulated.

Many DNA polymerases and repair factors are tethered to their DNA substrates through interaction with processivity clamps2,3. These clamps are multimeric, ring-shaped molecules4,5 that encircle DNA and have binding sites for clamp interacting proteins (CLIPs) that specifically interact with clamp binding motifs (CBMs) within CLIPs6,7. In E. coli, along with many factors involved in DNA replication, genome arrangement, and mismatch repair8–11, all five DNA polymerases interact with the β2 processivity clamp3,8, which has two CLIP binding sites.

Clamp binding ensures CLIPs act at proper sites in cells, yet how a large pool of CLIPs compete for a limited number of clamps remains unclear. CLIP occupancy on the clamp may be largely determined by the relative abundance and binding affinities to the clamp. However, this does not explain how high-abundance CLIPs do not prevent the clamp binding of low-abundance CLIPs12. Intriguingly, most CLIPs also interact with other factors and/or specific DNA structures8,13,14, and these additional interactions may facilitate clamp binding of select CLIPs at distinct replication and repair sites. A subset of CLIPs, including all three TLS polymerases, interacts with the tetrameric single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) binding protein (SSB4; hereafter denoted as SSB)(Fig. 1a)14–16. Besides the lagging strand during processive replication, ssDNA is also generated as an intermediate during damage repair and tolerance. SSB promotes these genome maintenance processes by binding to ssDNA and interacting with a host of SSB interacting proteins (SIPs)17.

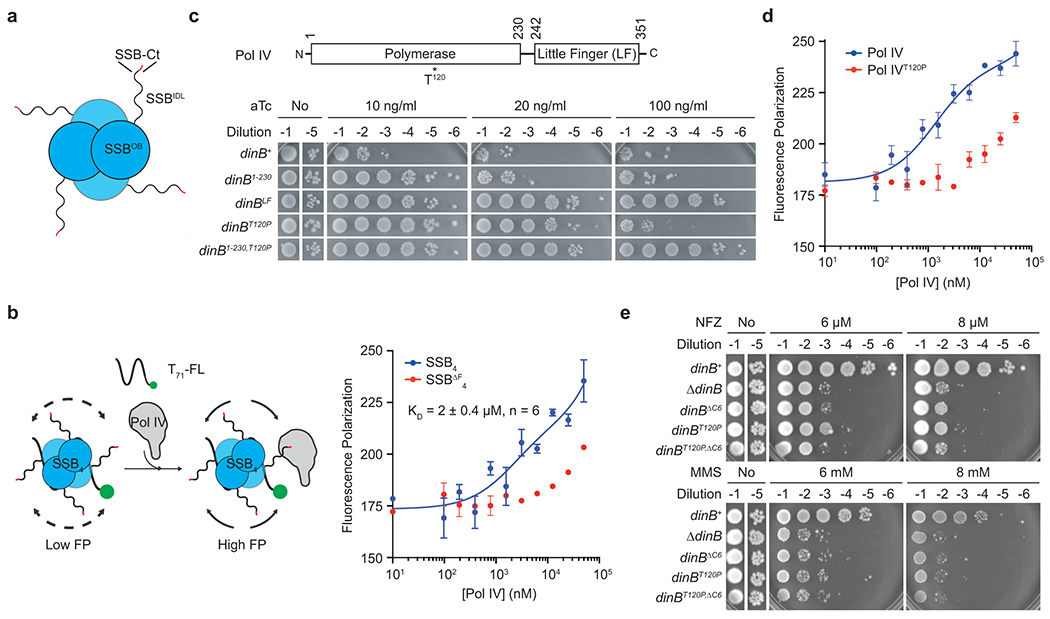

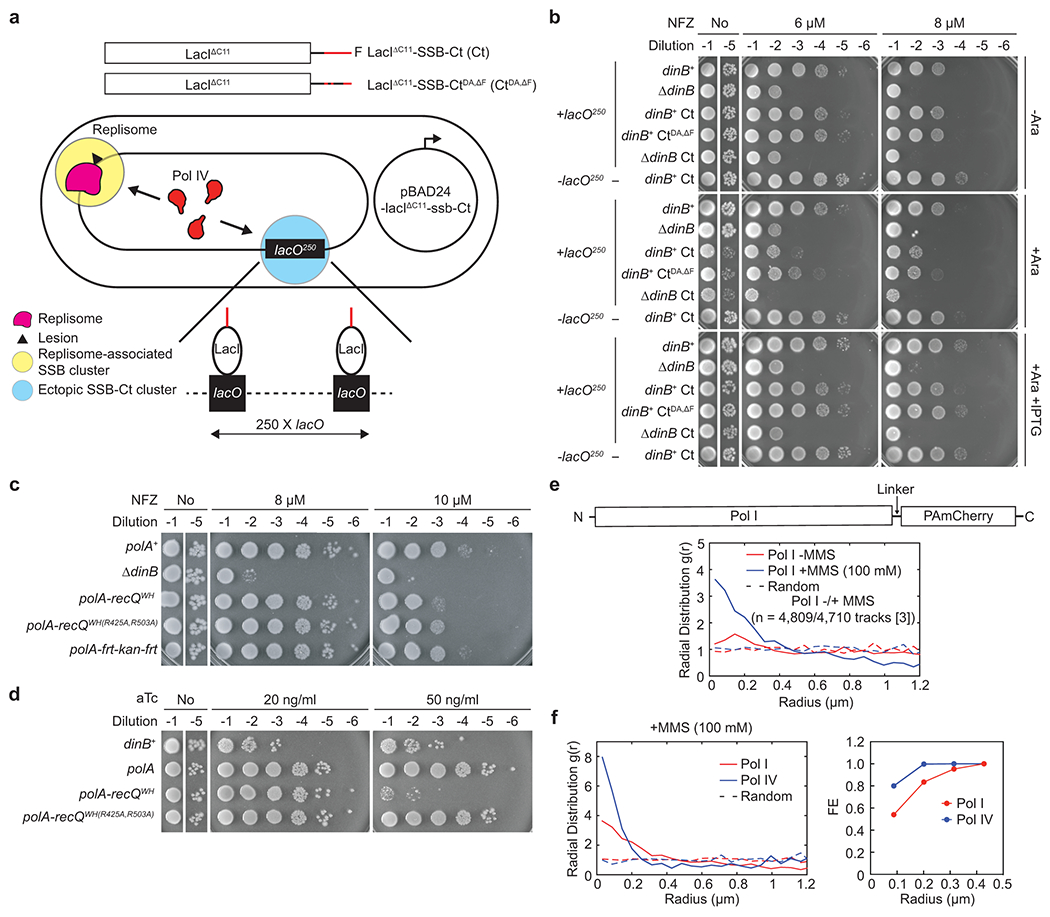

Fig. 1. An SSB-binding mutation within Pol IV.

a. E. coli SSB tetramer (SSB4). SSBOB, N-terminal OB domain; SSBIDL, intrinsically disordered linker; SSB-Ct, C-terminal peptide (MDFDDDIPF) with the conserved phenylalanine in red.

b. (Left) An FP-based binding assay scheme. T71-FL, 3′ fluorescein (FL)-labeled ssDNA of 71 repeats of dTMP. (Right) Interaction between purified Pol IV and SSB4-T71-FL or SSBΔF4-T71-FL measured by changes in FP. SSBΔF, SSB lacking the conserved phenylalanine. Means ± ranges of duplicate measurements; n, number of independent duplicate measurements.

c. Overexpression-induced cell death by Pol IV and its variants. Indicated gene products were expressed from a tetracycline-inducible expression cassette on the genome. aTc, anhydrotetracycline.

d. Interaction of purified Pol IV or Pol IVT120P with SSB4-ssDNA was measured as described in Fig. 1b. Means ± ranges of duplicate measurements.

e. Sensitivity of E. coli strains bearing indicated dinB alleles to NFZ and MMS. dinB, gene encoding Pol IV; dinBΔC6, Pol IV lacking C-terminal clamp binding motif.

In this study, we demonstrate that the interaction of E. coli TLS polymerase Pol IV with replication fork-associated SSB is required for TLS on both the leading and lagging strands. While the intrinsic binding affinity of Pol IV to SSB is low, the formation of a cluster of SSB molecules within a stalled replication fork promotes the interaction, enriching Pol IV. Locally concentrated Pol IV can associate with the β2 clamp by overcoming the gatekeeping mechanism of the Pol III replicative polymerase18 and perform TLS. By promoting TLS, the Pol IV-SSB interaction suppresses the resolution of lesion-stalled replisomes through the recombination-dependent damage avoidance pathway, revealing a critical role of SSB in resolution pathway choice. Unlike Pol IV, Pol I, an abundant CLIP without SSB-binding activity19, is only weakly enriched at stalled forks. However, endowing Pol I with SSB binding activity attenuates Pol IV-mediated TLS presumably by competitively inhibiting the association of Pol IV with the β2 clamp at the fork. Our results demonstrate that fork-associated SSB spatially segregates Pol IV and Pol I, which helps define selective clamp access among CLIPs at stalled replication forks.

Results

Identification of an SSB binding defective mutant Pol IV

SSB interacts with Pol IV14 and most SIPs through its conserved C-terminal peptide (SSB-Ct)17 (Fig. 1a). Deleting the ultimate phenylalanine of SSB-Ct severely compromises these interactions17,20,21. At the replication fork, SSB exists as a nucleoprotein complex with ssDNA (SSB-ssDNA). In a fluorescence-polarization (FP)-based assay, Pol IV could interact with SSB in SSB-ssDNA and this interaction is mediated through SSB-Ct because the interaction was ablated upon deletion of the conserved phenylalanine (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a). However, to investigate the role of the Pol IV-SSB interaction in TLS, it was necessary to identify SSB-binding mutations within Pol IV to avoid pleiotropic effects associated with mutating SSB-Ct17. Notably, we found that over-expression of many SIPs caused cell death and SSB-binding mutations attenuated this lethality (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Given that Pol IV also causes similar over-expression toxicity22 (Fig. 1c), we hypothesized that SSB-binding mutations within Pol IV would diminish this cytotoxicity. Furthermore, the binding site(s) for SSB-Ct likely resides in the polymerase domain because the polymerase domain alone was responsible for Pol IV over-expression toxicity (Fig. 1c). From a collection of point mutations within Pol IV that attenuate overexpression toxicity23, we identified the dinBT120P mutation in the polymerase domain as a promising candidate because Thr120 is surface exposed and away from catalytic and clamp-interacting residues (Extended Data Fig. 1c).

Binding of Pol IVT120P to SSB4-ssDNA was too weak to be reliably estimated (Fig. 1d), indicating that the dinBT120P mutation abolished the Pol IV-SSB interaction. Importantly, Pol IVT120P retains wild-type polymerase and clamp binding activities23, yet the dinBT120P mutation severely sensitized cells to nitrofurazone (NFZ) and methyl methanesulfonate (MMS)23, Pol IV cognate damaging agents24,25 (Fig. 1e). This increased sensitivity likely results from compromised Pol IV-mediated TLS because dinBΔC6, which completely compromises Pol IV-mediated TLS26, was epistatic to the dinBT120P mutation (Fig. 1e). Thr120 likely makes direct contact with SSB because mutation of Thr120 to other residues including alanine also sensitized cells to NFZ and MMS to varying degrees (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We could not directly measure expression levels of Pol IVT120P due to the lack of quality Pol IV antibodies, but the dinBT120P mutation is unlikely to influence expression because Pol IVT120P largely retained wild-type folding as measured by circular dichroism and thermal stability (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Therefore, these results suggest that the Pol IV-SSB interaction is critical for regulating Pol IV in cells.

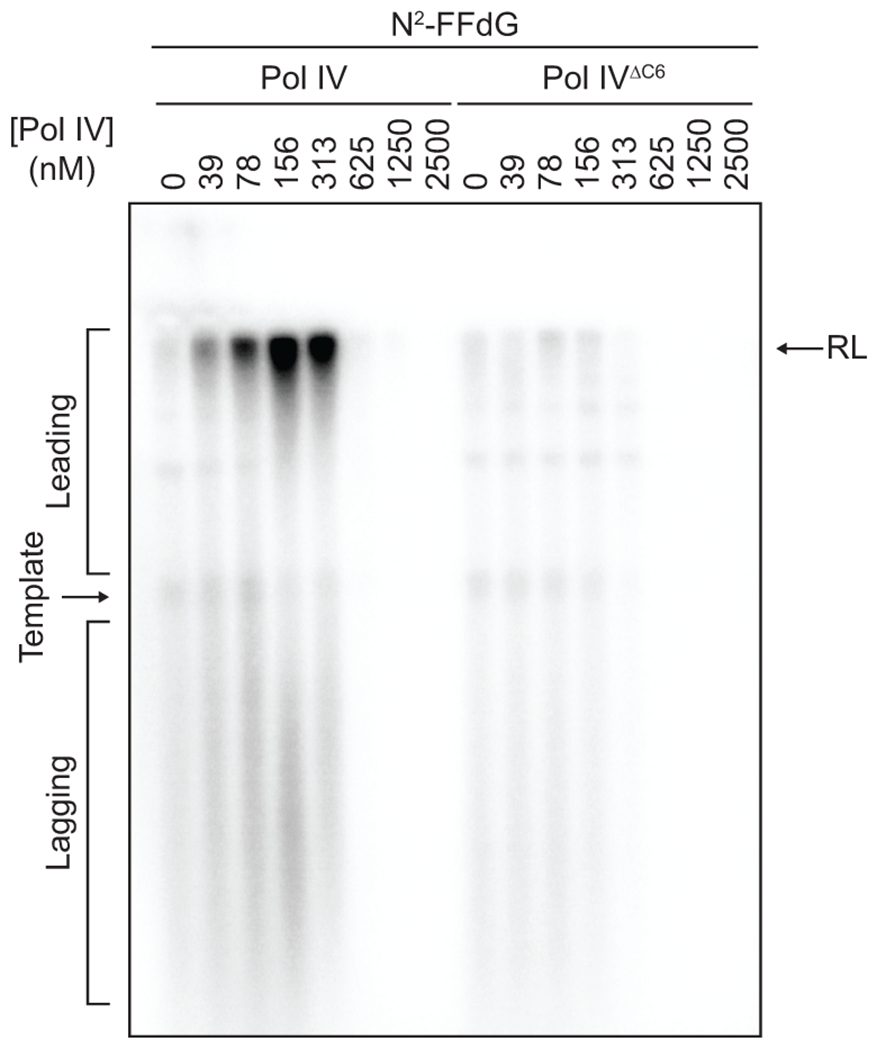

SSB facilitates access of Pol IV to lesion-stalled forks

To investigate if the compromised cellular TLS in the dinBT120P strain is due to ablation of the Pol IV-SSB interaction, we reconstituted Pol IV-mediated TLS within the E. coli replisome on rolling circle DNA templates that bear on the leading strand template a single N2-FFdG or 3meA (Fig. 2a)18. These lesions are structural analogs of DNA adducts created in NFZ or MMS-treated E. coli24,27 and inhibited both leading and lagging strand synthesis (Fig. 2b and d). Pol IV restored synthesis of both strands with maximum synthesis around 100 (N2-FFdG) or 150 nM (3meA) before completely inhibiting replication at higher concentrations (Fig. 2b and d)18,28. The accumulation of resolution-limited (RL) leading strand replication products results from multiple passages through blocking lesions, indicating efficient Pol IV-mediated TLS without strand discontinuities (Extended Data Fig. 2)18. Pol IVT120P similarly restored replication and achieved comparable maximum synthesis (Fig. 2b) but notably required 2- to 3-fold higher concentrations compared with Pol IV. The reduced potency of Pol IVT120P suggests that the dinBT120P mutation slows down TLS. Indeed, Pol IVT120P mediated TLS slower than Pol IV did (Fig. 2c), resulting in persistent stalling at the lesion (Supplementary Fig. 2a).

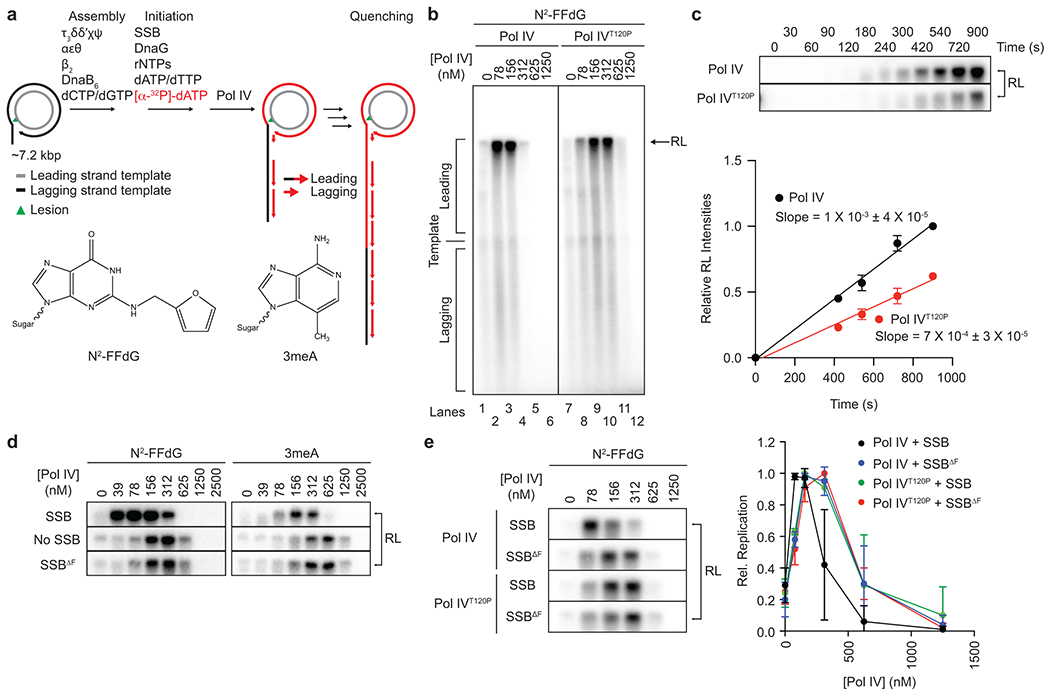

Fig. 2. SSB promotes access of Pol IV to stalled replication forks.

a. Lesion-containing rolling circle DNA templates and in vitro reconstitution of Pol IV-mediated TLS within the E. coli replisome. Replication products were separated on an alkaline agarose gel and visualized by autoradiography. Long leading strand replication products accumulate as a band at the resolution limit (RL) of the gel (~45 kilonucleotides); short lagging strand replication products run as diffusive bands below the unreplicated substrate (see Fig. 2b). N2-FFdG, N2-furfuryl dG; 3meA, 3-deaza-3-methyladenine.

b. The N2-FFdG-containing template was replicated in the presence of indicated concentrations of Pol IV or Pol IVT120P.

c. The N2-FFdG-containing template was replicated in the presence of Pol IV or Pol IVT120P (78 nM), and the reactions were sampled at indicated times. (Top) Replication products at the RL. (B) Quantification of replication products at the RL shown in the top. Means ± SDs of three independent experiments. Lines are linear fits with indicated slopes. Refer to Supplementary Fig. 2a for the entire gel.

d. The N2-FFdG- or 3meA-containing template was replicated in the presence of indicated concentrations of Pol IV with SSB or SSBΔF or without SSB. Refer to Supplementary Fig. 2b and c for the entire gels.

e. The N2-FFdG-containing substrate was replicated in the presence of indicated concentrations of Pol IV or Pol IVT120P with SSB or SSBΔF. (Left) Replication products at the RL. (Right) Quantification of leading strand replication products shown left. Rel. Replication, relative band intensities to the peak band intensities for indicated pairs of Pol IV and SSB. Means ± SDs (n = 3). Lines are linear connections between adjacent means. Refer to Supplementary Fig. 2e for the entire gel.

Conversely, when SSB was omitted, TLS over N2-FFdG or 3meA required 2- to 3-fold higher concentrations of Pol IV (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 2d). Importantly, replacing SSB with SSBΔF, which has a reduced affinity to Pol IV (Fig. 1b) but retains ssDNA binding (Extended Data Fig. 1a), made Pol IV less potent. This reduced potency was comparable to the reduction upon omitting SSB (Fig. 2d), ruling out that ssDNA binding activity potentiates Pol IV. Moreover, SSBΔF did not further reduce the potency of Pol IVT120P (Fig. 2e), indicating that the reduced potency resulted from its defective interaction with SSB, not other components of the E. coli replisome. Collectively these results suggest that SSB promotes TLS by locally concentrating Pol IV at the fork.

dinBT120P abolishes fork enrichment of Pol IV in cells

Eliminating the Pol IV-SSB interaction results in defective in vitro TLS that can be rescued with a relatively modest increase (2 to 3-fold) in Pol IV concentration whereas loss of the Pol IV-β2 clamp interaction cannot be similarly rescued (Extended Data Fig. 3). Yet, loss of either the Pol IV-SSB or Pol IV-β2 clamp interaction severely compromises TLS in cells. To address this apparent discrepancy, we examined the potential role of the Pol IV-SSB interaction in localizing Pol IV to stalled forks. To locate individual Pol IV molecules in cells, we employed single-particle tracking Photoactivated Localization Microscopy (sptPALM)29,30. Imaging strains expressed a C-terminal fusion of Pol IV or its variants to the photoactivatable fluorescent protein PAmCherry from the dinB locus and SSB-mYPet from the lacZ locus in the presence of native wild-type SSB (Fig. 3a, top, and b)29. To assess the colocalization of Pol IV with replisomes, we first located replisomes using SSB-mYPet (Fig. 3b)29. Subsequently, static Pol IV-PAmCherry molecules were located by PALM (Fig. 3b) and the distance of each static Pol IV molecule to the nearest SSB focus was determined29.

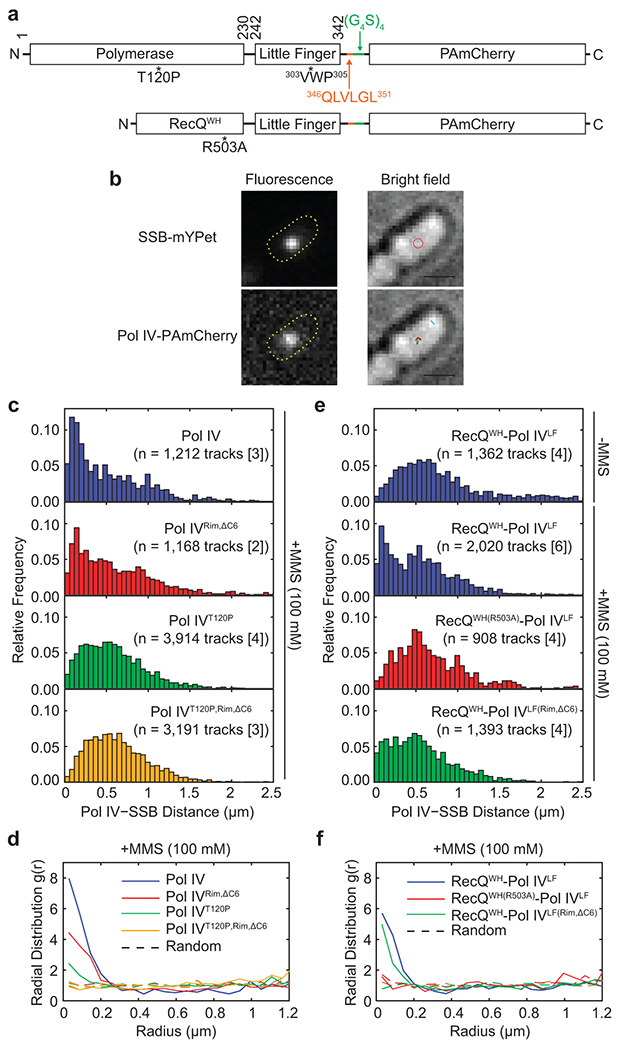

Fig. 3. SSB enriches Pol IV at lesion-stalled replication forks.

a. Schematic diagrams of PAmCherry fusions of Pol IV and RecQWH-Pol IVLF and their variants. Pol IVLF, Little Finger domain of Pol IV; 303VWP305, rim interacting residues; 346QLVLGL351, the CBM of Pol IV (orange); (G4S)4, a flexible linker (green); RecQWH, Winged-Helix domain of RecQ

b. (Left) Representative fluorescence micrographs of an MMS-treated cell. An SSB-mYPet focus composed of multiple SSB-mYPet molecules (top) and a representative single photoactivated Pol IV-PAmCherry molecule (bottom) with overlays showing the cell outlines. (Right) Corresponding brightfield micrographs with overlays showing the position of the SSB focus (red circle, top) or all detected static Pol IV tracks (colored dots, bottom) (Scale bars: 1 μM). Refer to Supplementary Fig. 3a for similar micrographs of a cell containing two SSB foci.

c. Distributions of the mean distance between each static Pol IV track and the nearest SSB focus for Pol IV and mutants in MMS-treated cells.

d. Radial distribution functions g(r) for Pol IV and mutants in MMS-treated cells. Also shown are random g(r) functions for each data set (dotted lines). Values of g(r) greater than 1 indicate enrichment.

e. Distributions of the mean distance between each static RecQWH-Pol IVLF track and the nearest SSB focus for RecQWH-Pol IVLF and mutants in untreated or MMS-treated cells.

f. Radial distribution functions g(r) for RecQWH-Pol IVLF and mutants in MMS-treated cells. Also shown are random g(r) functions for each data set (dotted lines).

*[i], tracks were acquired from the “i” number of independent experiments.

Consistent with our prior observations29, MMS treatment led to decreases in Pol IV-SSB distances compared with untreated cells (Pol IV in Fig. 3c), indicative of more Pol IV molecules colocalizing with replisomes. To quantify the enrichment of Pol IV near the fork, we calculated a radial distribution function, g(r), which expresses the likelihood of Pol IV being found within a distance r from the nearest SSB focus to random cellular localizations (Supplementary Fig. 3b). In MMS-treated cells, Pol IV was about 8-fold enriched (g(r) ~ 8) near forks relative to random localization (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3c and d), whereas it was barely enriched in untreated cells29. In contrast, upon MMS treatment, the distance distribution between Pol IVT120P and SSB foci barely shifted to shorter distances (Fig. 3c), and consequently, Pol IVT120P was only about 2-fold enriched (Fig. 3d) despite comparable expression of Pol IV and Pol IVT120P (Supplementary Fig. 3e). Collectively, our imaging experiments suggest that fork-associated SSB plays the dominant role in localizing Pol IV near stalled replisomes.

SSB binding is sufficient for the fork enrichment of Pol IV

Besides SSB and the β2 clamp, Pol IV also interacts with other factors31–34. To examine if the Pol IV-SSB interaction is sufficient for the enrichment of Pol IV near lesion-stalled replisomes, we replaced the polymerase domain of Pol IV with the SSB-interacting winged helix domain of E. coli RecQ (RecQWH)20, creating a chimeric protein, RecQWH-Pol IVLF, which was expressed from the native dinB locus as a C-terminal fusion to PAmCherry (Fig. 3a, bottom). Like Pol IV, this chimeric protein bears both SSB and clamp binding activities, but it is unlikely to interact with other Pol IV-interacting factors. Like wild-type Pol IV, the chimeric protein was highly enriched (g(r) ~ 6) near forks in MMS-treated cells but not in untreated cells (Fig. 3e and f). Furthermore, the SSB-binding mutation (RecQWH(R503A))20 nearly abolished the enrichment (Fig. 3e and f). In contrast, the β2 clamp-interacting mutation (Pol IVLF(Rim,ΔC6)) barely reduced the enrichment (Fig. 3e and f). These results demonstrate that interaction of Pol IV with fork-associated SSB is primarily responsible for localizing Pol IV to lesion-stalled forks and interactions with other factors are not required.

Given Pol IVLF is not necessary for the fork localization of Pol IV, the higher enrichment of Pol IV (g(r) ~ 8) compared to Pol IVRim,ΔC6 (g(r) ~ 5) (Fig. 3d) suggests that Pol IVLF contributes to retaining Pol IV at the fork after SSB-mediated fork localization. Pol IVLF is the primary β2 clamp binding domain and the Pol IVLF-β2 clamp interaction is cooperatively enhanced by the Pol IV-P/T junction interaction35. However, in contrast to Pol IV, RecQWH-Pol IVLF is unlikely to form a stable complex with the β2 clamp because it cannot bind the P/T junction. Thus, the higher enrichment of Pol IV compared with that of RecQWH-Pol IVLF likely represents a fraction of fork-localized Pol IV molecules that form a stable complex with the β2 clamp. Consistent with this notion, the enrichment of Pol IVRim,ΔC6 was similar to that of RecQWH-Pol IVLF (Fig. 3d and f) and catalytically defective Pol IV29. These results suggest that SSB-mediated fork enrichment of Pol IV is necessary for the Pol IV-β2 clamp interaction at the fork. Moreover, it remains possible that following localization to stalled forks, the association of Pol IV with the β2 clamp is modulated by other Pol IV-interacting factors31–34.

Enrichment enables Pol IV to overcome Pol III gatekeeping

The interaction between the ε subunit of Pol III core and the β2 clamp acts as a molecular gate to prevent Pol IV from binding to the β2 clamp18. Therefore, we hypothesized that enrichment of Pol IV near stalled replisomes is required for Pol IV to compete with the ε subunit for clamp binding. In this case, weakening the ε-clamp interaction would potentiate Pol IVT120P. Indeed, when the ε-cleft interaction was weakened by the dnaQ(εQ) mutation36 (Extended Data Fig. 4a), which reduces the TLS-inhibitory activity of the ε subunit (αεθ vs αεQθ for Pol IV in Fig. 4a)18, Pol IVT120P mediated TLS at 2- to 3-fold lower concentrations compared with the wild-type replisome (αεθ) (αεθ vs αεQθ for Pol IVT120P in Fig. 4a). Conversely, strengthening the ε-cleft interaction by the dnaQ(εL) mutation (Extended Data Fig. 4a), which modestly suppresses Pol IV-mediated TLS (αεθ vs αεLθ for Pol IV in Fig. 4b)18, resulted in Pol IVT120P barely mediating TLS (αεθ vs αεLθ for Pol IVT120P Fig. 4b). Consistent with this in vitro synthetic suppression, the strain bearing both the dnaQ(εL) and dinBT120P was as severely sensitized to NFZ as the ΔdinB strain (Fig. 4c)18.

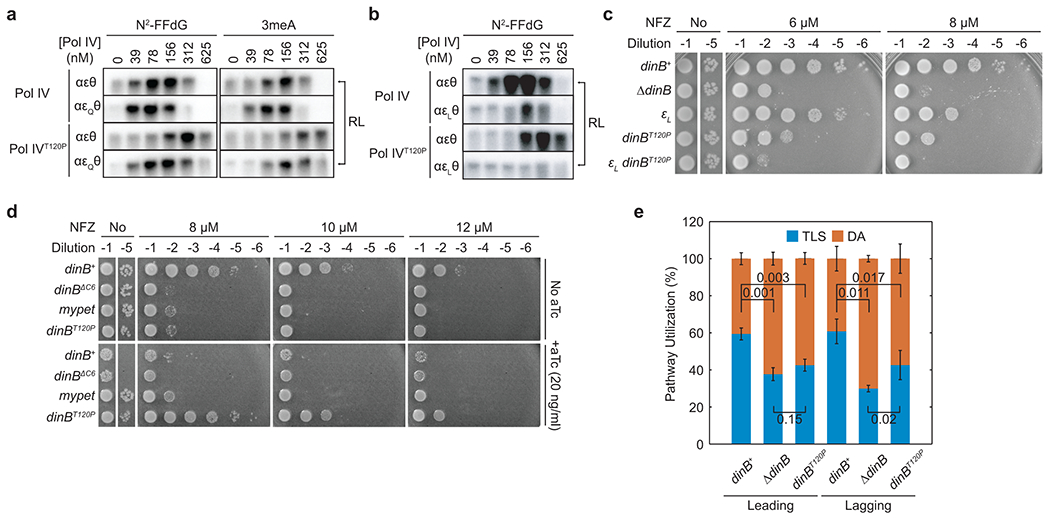

Fig. 4. Enrichment of Pol IV at stalled forks promotes TLS.

a. Lesion-containing templates were replicated with the αεθ or αεQθ-containing replisome in the presence of indicated concentrations of Pol IV or Pol IVT120P. RL, resolution-limited replication products. Refer to Supplementary Fig. 4a for the entire gels.

b. The N2-FFdG containing template was replicated with the αεθ or αεLθ-containing replisome in the presence of indicated concentrations of Pol IV or Pol IVT120P. Refer to Supplementary Fig. 4b for the entire gel.

c. Sensitivity of indicated strains to NFZ. εL, dnaQ(εL).

d. Sensitivity of ΔdinB strains to NFZ upon induction of indicated genes from a Tet-inducible genomic expression cassette. dinBΔC6, dinB lacking clamp binding motif; mypet, a coding sequence for monomeric Ypet fluorescent protein, a negative control.

e. Pathway choice of N2-FFdG-stalled replisomes in indicated dinB strains. Leading and Lagging, the template strand bearing N2-FFdG. TLS, translesion synthesis pathway; DA, damage avoidance pathway. Means ± SDs (n = 5 for dinBT120P, lagging strand; n = 3 for all the others; n, number of independent experiments). The statistical significance of the difference between the indicated pairs was determined by two-tailed Welch’s t-test; numbers, p values.

These results also suggest that elevating the expression level of Pol IVT120P in cells would normalize TLS because global increases of Pol IVT120P could recapitulate SSB-mediated local enrichment of Pol IV at stalled forks. Indeed, ectopic over-expression of Pol IVT120P in ΔdinB restored nearly wild-type tolerance to NFZ (Fig. 4d). Collectively, these results demonstrate that SSB-mediated fork enrichment of Pol IV enables Pol IV to overcome the ε kinetic barrier and mediate TLS.

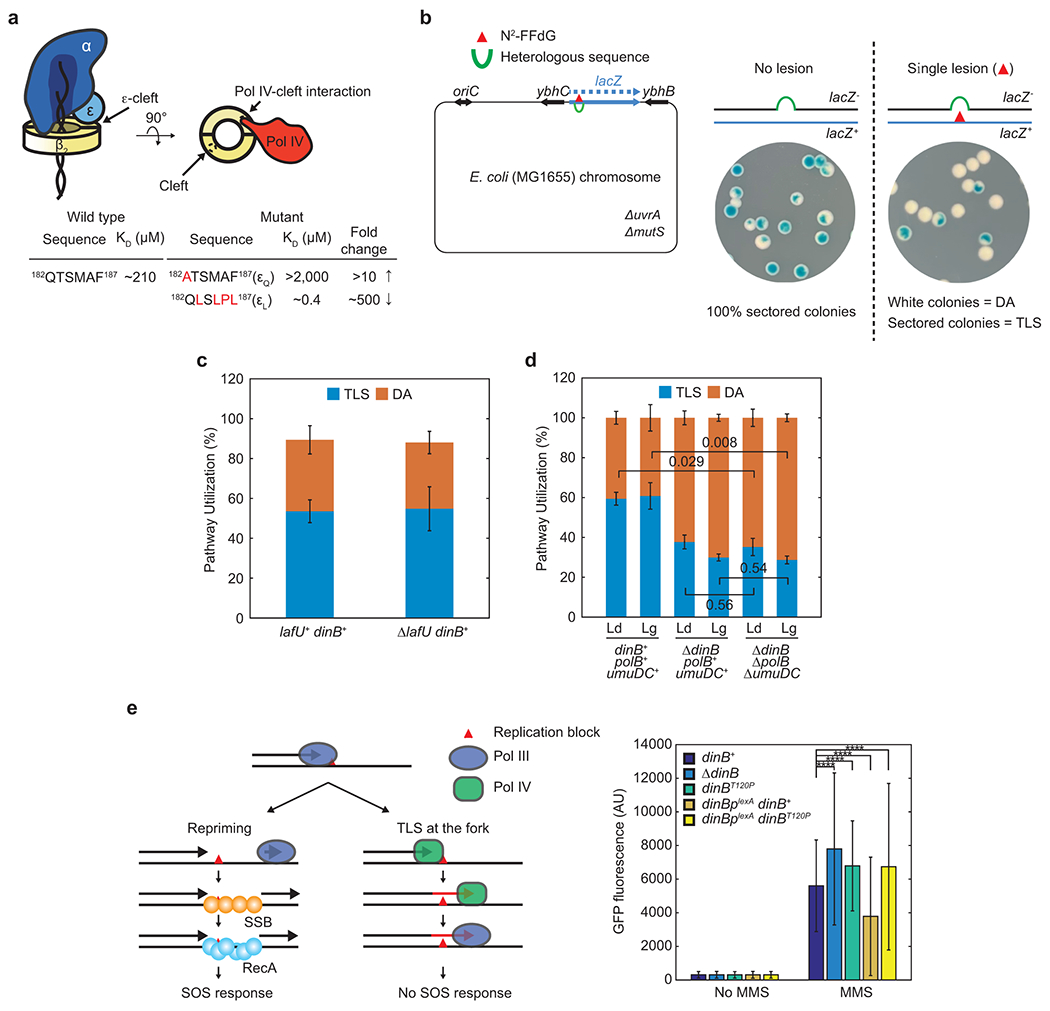

SSB regulates the pathway choice of lesion-stalled forks

To assess the impact of the Pol IV-SSB interaction on resolution pathway choice of lesion-stalled replisomes, we employed a cell-based assay that quantitatively measures fractions of lesion-stalled replisomes resolved through either TLS or homology-dependent damage avoidance (DA) pathways37. Assay strains that contain a single N2-FFdG lesion site-specifically introduced into the genome express functional LacZ only when lesion-stalled replication is resolved by TLS, resulting in the formation of blue-sectored colonies on X-gal containing plates (Extended Data Fig. 4b).

Replisomes stalled at N2-FFdG on either the leading- or lagging-strand template were resolved by a combination of TLS and DA (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 4c). About 60% of cells that tolerated the N2-FFdG lesion on either the leading or lagging strands were blue-sectored, indicating that stalled replication was primarily resolved by TLS. Deleting dinB (ΔdinB) reduced resolution through TLS on both the leading and lagging strand templates to 30 – 40% with concomitant increases in the utilization of the DA pathway (Fig. 4e). The residual TLS in the ΔdinB background is likely due to inefficient Pol III-mediated TLS over N2-FFdG18 because deleting the remaining TLS polymerases (Pol II and V) did not further reduce the utilization of TLS (Extended Data Fig. 4d).

In the dinBT120P background, about 40% of stalled replisomes on the leading strand template were resolved by TLS, which was statistically indistinguishable from the ΔdinB background (Fig. 4e), demonstrating that the dinBT120P mutation severely compromises Pol IV-mediated TLS. Notably, TLS on the lagging strand was similarly reduced by the dinBT120P mutation. In addition, the SOS DNA damage response, which reflects repriming and thus the DA pathway in cells (Extended Data Fig. 4e, left)18, was more highly induced in the background of dinBT120P compared with dinB+ (Extended Data Fig. 4e, right). Collectively, these results indicate that fork-associated SSB controls pathway utilization on both strands.

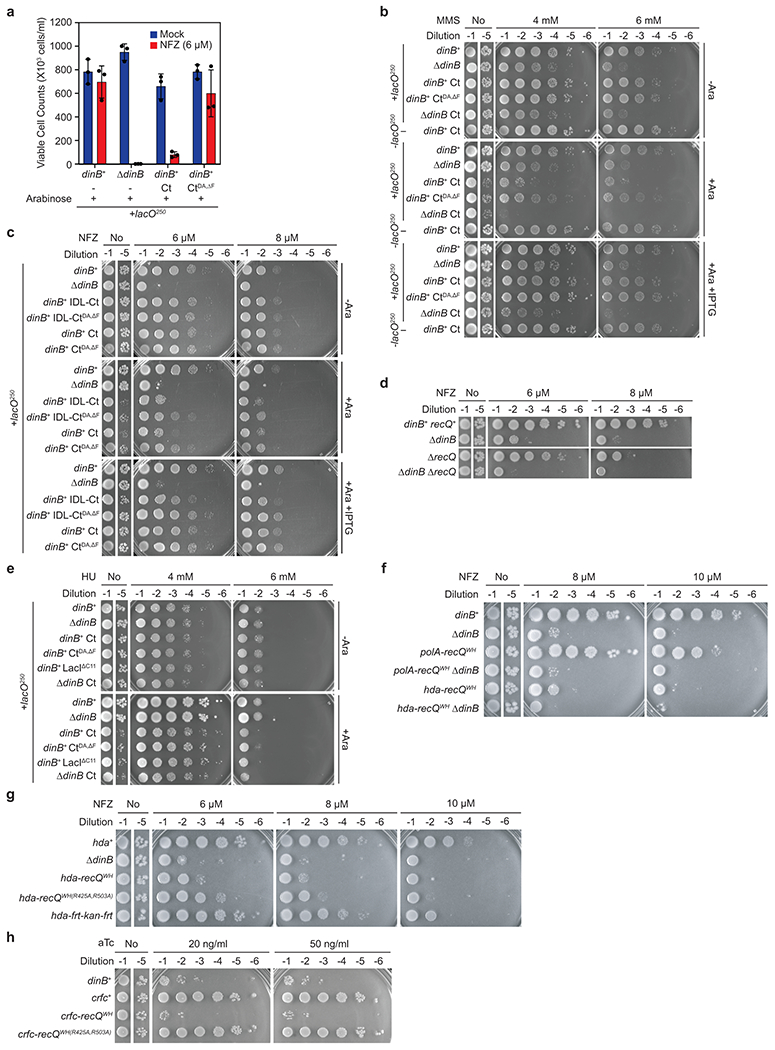

Localization of Pol IV to clustered SSB

Given the weak binding affinity of Pol IV to SSB (micromolar KD) (Fig. 1b), cellular concentrations of Pol IV38–40 do not seem not high enough to drive the high fork enrichment of Pol IV (Fig. 3d). However, unlike the in vitro binding assays, Pol IV likely interacts with a cluster of SSB at stalled forks41. To investigate if this clustering of SSB promotes the Pol IV-SSB interaction, we constructed E. coli strains, in which an SSB-Ct cluster is formed at an ectopic genomic location (Fig. 5a). In these strains, SSB-Ct was expressed as a C-terminal fusion to LacIΔC11 (LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct) (Fig. 5a, top) in the presence of a genomic lacO array (lacO250) that contains 250 repeats of LacI binding sites (lacO) within a 10 kilobase pair region (Fig. 5a, bottom)42. This ectopic SSB-Ct cluster would sequester Pol IV and presumably other SIPs that are normally enriched near replication forks (Fig. 5a, bottom), compromising Pol IV-mediated TLS. Indeed, expression of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct sensitized cells to NFZ and MMS (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 5a-c) while only slowing down cell growth in the absence of damaging agents (Supplementary Fig. 5a). Formation of the ectopic SSB-Ct cluster also further sensitized ΔdinB to both NFZ and MMS (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 5b), implying that the action of other SIPs is possibly inhibited as well. For example, similar additive sensitization was observed for ΔdinB and ΔrecQ (Extended Data Fig. 5d). In contrast, the ectopic SSB-Ct cluster barely sensitized cells to hydroxyurea (HU) (Extended Data Fig. 5e), which causes replication stalling and cell death at millimolar concentrations43. Given Pol IV does not play an appreciable role in tolerating HU, sensitization by the ectopic SSB-Ct cluster seems selective to Pol IV-cognate blocking lesions. In addition, mutating SIP-interacting residues (CtDA,ΔF) within SSB-Ct substantially reduced the sensitization (Fig. 5b and Extended Data Fig. 5a–c). These results suggest that LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct compromises Pol IV-mediated TLS by preventing the Pol IV-SSB interaction.

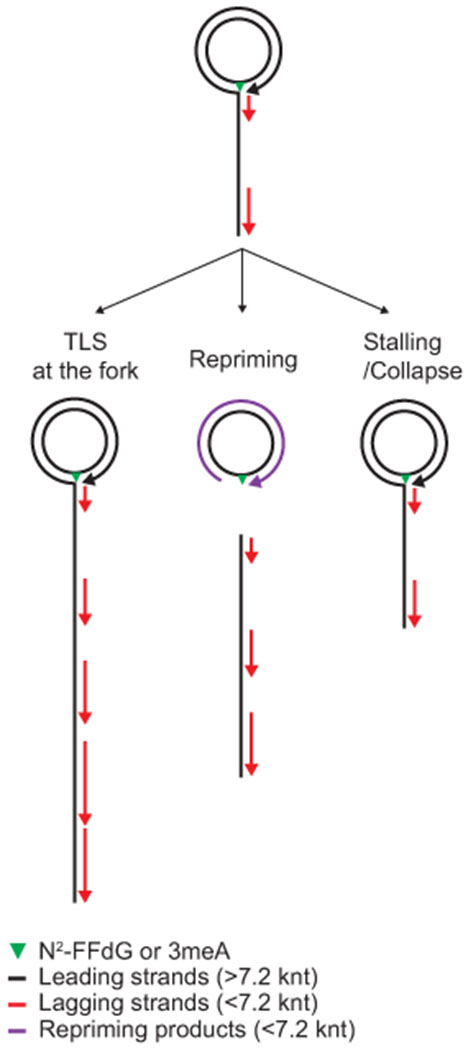

Fig. 5. SSB-driven ectopic localization of Pol IV or Pol I.

a. Use of modified LacIΔC11 and a genomic lacO array (lacO250) to create an ectopic SSB-Ct cluster outside of replication forks. (Top) LacIΔC11 with SSB-Ct (Ct) or SSB-CtDA,ΔF (CtDA,ΔF) at the C-terminal end. (Bottom) An assay strain bearing the genomic lacO250 (+lacO250) and pBAD24 that expresses LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct or LacIΔC11-SSB-CtDA,ΔF from an arabinose-inducible promoter. Assay strains lacking lacO250 (-lacO250) are otherwise isogenic to the +lacO250 strain. In experiments presented in Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 5, expression of LacI variants was induced by 0.2% arabinose (Ara) unless otherwise indicated. When indicated, 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside) was added.

b. Sensitivity of indicated assay strains to NFZ upon induction of Ct or CtDA,ΔF.

c. Sensitivity of the indicated strains to NFZ. polA-recQWH or WH(R425A,R503A), the coding sequence for Pol I-RecQWH or WH(R425A,R503A); polA, polA control allele with frt-kan-frt at the 3’ end of polA.

d. Sensitivity to over-expressed Pol I-RecQWH and its SSB-binding mutant. Expression of indicated genes was induced from a Tet-inducible genomic expression cassette. aTc, anhydrous tetracycline.

e. Localization of Pol I in cells. (Top) Schematic diagrams of a PAmCherry fusion of Pol I. (Bottom) Radial distribution functions (g(r)) for Pol I in untreated or MMS-treated cells. Also shown are random g(r) functions for each data set (dotted lines). *[i], tracks were acquired from the “i” number of independent experiments.

f. Pol I is primarily localized outside of replication forks. (Left) Radial distribution functions g(r) for Pol IV and Pol I in MMS-treated cells. Also shown are random g(r) functions for each data set (dotted lines). The same data for Pol IV in Fig. 3d and Pol I in Fig. 5e is reproduced here for comparison. (Right) Fractional enrichment (FE) of Pol I (red) and Pol IV (blue). FE, ratios of integrated g(r) values over 1 (random g(r)) between 0 and indicated radii to the total integrated g(r).

This sensitization requires clustering of SSB-Ct on DNA because the addition of IPTG, which weakens the LacI-lacO interaction, or removal of the lacO250 array prevented over-expressed LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct from sensitizing cells to damaging agents (Fig. 5b, Extended Data Fig. 5b and c, and Supplementary Fig. 5b–e). Therefore, experiments with the artificial, ectopic SSB-Ct cluster demonstrate that clustering of SSB-Ct at the fork promotes the Pol IV-SSB interaction in cells, highly enriching Pol IV near lesion-stalled forks.

Engineered SSB binding localizes Pol I to forks

SSB-mediated fork enrichment of Pol IV may allow it to outcompete CLIPs lacking SSB-binding, such as Pol I. To test this idea, we examined if engineering SSB binding activity into Pol I by appending the RecQWH (Pol I-RecQWH, Supplementary Fig. 5f) would interfere with Pol IV-mediated TLS. Replacing polA with polA-recQWH indeed sensitized cells to NFZ (Fig. 5c) and ΔdinB was epistatic to polA-recQWH (Extended Data Fig. 5f), indicating that Pol I-RecQWH inhibits Pol IV-mediated TLS. SSB binding is required for this inhibition as an SSB-binding mutation (polA-recQWH(R425A,R503A))20 diminished the sensitization (Fig. 5c). We also made similar observations with Hda, another CLIP lacking SSB binding (Extended Data Fig. 5f and g)44,45. Together these results suggest that forced fork localization of CLIPs interferes with the actions of other CLIPs at the fork. In addition, over-production of Pol I-RecQWH, but not Pol I, caused cell death, which was attenuated with an SSB-binding mutation (Fig. 5d), and similar observations were also made with Crfc, another CLIP (Extended Data Fig. 5h)44,45. Given that this cytotoxicity likely results from displacement of Pol III from the β2 clamp22,28, these results support our model that SSB binding is required for CLIPs to access the clamps at the fork.

To investigate the localization of Pol I in cells, we employed sptPALM with an imaging strain that expressed a C-terminal PAmCherry fusion of Pol I from the native polA locus (Fig. 5e, top)30. Similar to Pol lV29, Pol I was marginally enriched near replication forks in untreated cells (Fig. 5e, bottom). However, in contrast to Pol IV, whose peak enrichment is coincident with SSB foci29, Pol I was most enriched between 0.1 and 0.15 μm off the center position. Presumably this off-center enrichment results from Pol I molecules acting on the junctions between Okazaki fragments, which are a few to several kilobase pairs away from the replication fork46. Upon MMS treatment, Pol I was further enriched over wide distances from the fork (~0.5 μm) (Fig. 5e, bottom), but the enrichment was distinct from that of Pol IV. While nearly 80% of enriched Pol IV colocalized with replication forks (within 0.1 μm from forks), only ~50% of enriched Pol I was localized within this distance (Fig. 5f). This enrichment of Pol I is likely due to the increase in the number of Okazaki fragments, which result from frequent replisome stalling47–49. Collectively, these results indicate that Pol I in MMS-treated cells is primarily enriched outside of stalled replication forks. We propose that upon lesion stalling, CLIPs lacking SSB-binding activity are largely excluded from the replication fork due to the disproportionate enrichment of SSB-interacting CLIPs, such as Pol IV.

Discussion

As TLS polymerases are error-prone, it is critical to prevent inappropriate use of these polymerases. How TLS polymerases are enriched near lesion-stalled replication forks while largely excluded from the fork during processive replication has remained unclear29. Previously, we showed that the ε subunit of Pol III acts as a molecular gate to limit the access of Pol IV and presumably other CLIPs to the β2 clamp18. Here, we demonstrate that replisome-associated SSB enriches Pol IV near replisomes only upon lesion stalling, and this increase in local concentration is required for Pol IV to overcome gatekeeping of Pol III and interact with the β2 clamp.

TLS-competent SSB clusters localize Pol IV to stalled forks

We demonstrated that most of the Pol IV enriched near lesion-stalled replisomes results from Pol IV interacting with fork-associated SSB. Paradoxically, SSB is always present at the replication fork through its association with the lagging strand template, yet Pol IV is barely enriched near moving replisomes29. What are the changes in fork-associated SSB upon stalling that enable this switch? In a moving replisome, a steady-state level of multiple SSB molecules are associated with the lagging strand template (Fig. 6a), forming a cluster of SSB-Ct that promotes processive replication50,51. However, individual SSB molecules in this cluster are present only transiently due to their rapid displacement by lagging strand synthesis52,53. This short resident time may localize only a small number of Pol IV molecules to replication forks.

Fig. 6. Roles of SSB in pathway choice and fork compartmentalization.

a. Lesion stalling of the leading strand polymerase and subsequent events – TLS vs Repriming. For simplicity, the lagging strand polymerase is omitted.

b. Compartmentalization of a replication fork by SSB. A circle surrounding the replication fork represents the TLS-competent SSB-Ct cluster, where Pol IV and possibly other SIPs, are enriched upon replication stalling at a leading strand lesion.

However, upon lesion-stalling, either a new pool of stably associated SSB on the leading strand template (for leading strand stalling) or reduced turnover of SSB on the lagging strand template (for lagging strand stalling) may form a stable SSB-Ct cluster (Fig. 6a). Our experiments with an ectopic SSB-Ct cluster argue that such a stable SSB-Ct cluster can highly enrich Pol IV near forks possibly because locally concentrated SSB-Ct repeatedly captures Pol IV through an avidity effect, preventing Pol IV from diffusing away. These features allow Pol IV to kinetically overcome gatekeeping of Pol III at stalled forks while minimizing access of Pol IV to moving replisomes.

Roles for SSB in resolution pathway choice

Lesion-stalling of the leading strand polymerase results in uncoupling of the DnaB helicase (Fig. 6a). The uncoupled helicase continues to unwind duplex DNA but at a substantially reduced rate, generating a growing stretch of ssDNA on the leading strand template48, which is likely bound by SSB molecules (i to ii in Fig. 6a). Stalling of the lagging strand polymerase results in a stable association of SSB molecules with a ssDNA gap between a blocking lesion and the downstream Okazaki fragment.

Modest enrichment of Pol IV by a small cluster of SSB shortly after stalling may be sufficient for TLS past easy lesions, such as N2-FFdG29, and such rapid TLS may result in recoupling of the helicase (ii to iii in Fig. 6a). In contrast, persistent stalling at difficult lesions, such as 3meA and benzopyrene (BaP)54, may generate a relatively larger SSB cluster, further enriching Pol IV (ii in Fig. 6a). This relatively high enrichment of Pol IV may be required for TLS past strong blocks.

Failure of TLS at the fork eventually results in repriming18, which leaves a long ssDNA gap (>200 nucleotides)55 (ii to iv in Fig. 6a). SSB associated with this gap is replaced with RecA56,57, resulting in a concomitant drop in local Pol IV concentration (iv in Fig. 6a). These gaps are primarily filled in by Homology-Dependent Gap Repair (HDGR) (iv to v in Fig. 6a) while a small fraction is filled in by post-replicative TLS58,59 (iv to vi in Fig. 6a). The minor utilization of TLS at the gap may be partly due to weak enrichment of Pol IV near the gap, which is insufficient to overcome the ε kinetic barrier18. Consistent with this model, the majority of BaP-stalled replisomes are resolved by HDGR18 whereas N2-FFdG-stalled replisomes are predominantly resolved by TLS (Fig. 4e).

Resolution pathway choice of lesion-stalled replisomes60 determines the extent of damage-induced mutagenesis. TLS at the fork enables a replisome to directly replicate a lesion-containing template without creating an ssDNA gap, and thus mutagenesis is likely limited to the vicinity of the lesion18. Moreover, errors made by TLS polymerases may be corrected by the proofreading activity of the replicative polymerase, which switches back upon completion of TLS61,62. In contrast, gaps resulting from repriming can be filled in by the combined actions of replicative and TLS polymerases in a highly mutagenic manner58. Compared with the localized mutagenesis by TLS at the fork, this widespread mutagenesis is more likely to result in functionally consequential genetic alterations. In this study, we demonstrate that SSB facilitates Pol IV-mediated TLS at the fork, suppressing repriming. Consistent with TLS at the fork being less mutagenic than TLS at the gap, MMS-induced mutagenesis is highly elevated in a dinBT120P strain compared with a dinB+ strain due to Pol V-mediated gap filling23. As Pol V also interacts with SSB15, SSB may also localize Pol V to gaps during post-replicative TLS.

Spatial segregation of CLIPs

Given that CLIPs interact with the β2 clamp via a common binding site, competitive clamp binding among CLIPs would interfere with the action of each other. Therefore, there may be additional structural signals, such as factors and specific DNA structures, that enable access of a subset of CLIPs to the β2 clamp at distinct DNA replication and repair intermediates. A subset of CLIPs including TLS polymerases interact with SSB whereas others do not. As demonstrated with Pol IV, SSB binding activity may serve as a fork-localization signal for SSB-interacting CLIPs (Fig. 6b), and consequently, CLIPs lacking SSB-binding activity are largely excluded from lesion-stalled replication forks. Such SSB-dependent spatial segregation may minimize interference among CLIPs at the fork.

Conversely, CLIPs that act at the junction between Okazaki fragments, such as Pol I and LigA8,44, may not be inhibited by CLIPs with SSB binding activity. As the ssDNA gaps between immediate Okazaki fragments are filled in by Pol III during Okazaki fragment synthesis, SSB molecules on the lagging strand are rapidly displaced and the DNA/RNA junction, which is ligated by the coordinated actions of Pol I and LigA, becomes spatially separated from the fork by a long stretch of dsDNA (Fig. 6b). This lack of stably associated SSB may result in CLIPs with SSB binding activity, such as Pol IV, being only marginally enriched near the DNA/RNA junction. We propose that CLIPs need to be first locally enriched to gain access to the β2 clamp and this hierarchical recruitment requires interactions with additional factors, such as SSB or specific DNA structures, that enrich CLIPs near their sites of action.

Methods

Purified proteins

αεθ, αεQθ, αεLθ, α, DnaB, clamp loader complex (τ3δδ’χψ), β2 clamp, DnaG, and SSB were purified as previously described63–65. Wild-type Pol IV and its variants were expressed in BL21(DE3) pLysS lacking the native dinB and purified as previously described66. His6-LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct and CtDA,ΔF were purified using Ni-NTA resin. Protein concentrations were determined by both the Bradford method and measuring absorbance at 280 nm. Concentrations and stoichiometries of complexes were determined by measuring the intensities of Coomassie-stained bands in SDS-PAGE gels with separately run individual purified subunits as standards67.

Reagents

N2-furfuryl dG-containing oligomer (5′-CTACCT/N2-furfuryl-dG/TGGACGGCTGCGA-3′) was provided by Deyu Li (Univ. of Rhode Island)66. The 3-deaza-methyl dA-containing oligomer (GCTCGTCAGACG/3-deaza-3-methylA/TTTAGAGTCTGCAGTG)68 and 3′ FAM-conjugated ssDNA of 71 repeats of dTMP (T71-FAM) were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies (IA, USA).

Chemicals

Anhydrotetracycline (aTc, TaKaRa, 631310), Hydroxyurea (HU, Sigma, H8627), Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS, Sigma, 129925), and Nitrofurazone (NFZ, Fluka, PHR1196)

Fluorescence polarization (FP)-based binding assays

Binding assays were performed in binding buffer (BB, 50 mM Hepes-HCl pH7.5/200 mM NaCl/0.05% Tween20/10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). Fluorescence polarization (FP) of fluorescein was measured at 25 °C using a SpectraMax M5 (Molecular Devices).

In direct binding assays with fluorescein-conjugated ssDNA (T71-FAM), to preform the SSB-T71-FAM complex, SSB or SSBΔF and T71-FAM were incubated at a 1.2:1 ratio in BB at room temperature (RT) before incubated with Pol IV or Pol IVT120P (Extended Data Fig. 1a). Then Pol IV or Pol IVT120P was incubated with preformed SSB-T71-FAM (50 nM) in BB at RT, and fluorescence polarization (FP) was measured at 25 °C. The equilibrium dissociation constants were determined by fitting the following model to measured FP values; F = Fmax X C/(KD + C) + NS X C + Background, wherein F is FP, Fmax is the maximum FP, C is the concentration of Pol IV or Pol IVT120P, KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant, NS is the slope of nonspecific binding and Background is the amount of nonspecific binding.

For competition binding assays with LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct or CtDA,ΔF, purified Pol IV (30 μM) was incubated with preformed SSB-T71-FAM (50 nM) in BB to form Pol IV-SSB-T71-FAM complex. Then LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct or CtDA,ΔF was incubated with Pol IV-SSB-T71-FAM complex in BB at RT, and FP was measured at 25 °C. To obtain IC50, the following model was fitted to measured FP values; F = Fbottom + (Ftop – Fbottom)/(1 + 10(C-logIC50)), wherein Ftop and Fbottom are plateaus in FP, C is the concentration of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct or CtDA,ΔF, and IC50 is the concentration of a competitor that displaces 50% of bound FL-SSB-Ct. Then the IC50 was used to calculate the equilibrium dissociation constant for the interaction between Pol IV and LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct or CtDA,ΔF by log(IC50) = log(10logKi X (1 + C/KD)), wherein Ki is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the interaction between Pol IV and LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct or CtDA,ΔF, C is the concentration of Pol IV, and KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the interaction between Pol IV and SSB-T71-FAM complex. Prism (GraphPad) was used for the fittings.

Measuring the damage-induced SOS response

The DNA damage-induced SOS response was measured as previously described65. Briefly, SOS reporter strains were cultured in Luria Broth (LB) at 37 °C with aeration until OD600 reached ~0.3. Cultures were treated with MMS (7 mM final) and further incubated at 37 °C with aeration for an additional 1 (Extended Data Fig. 4e) or 1.5 (Supplementary Fig. 5e) hour. Then cells were fixed with formaldehyde (4%), thoroughly washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), and finally resuspended in PBS. GFP fluorescence from individual cells was measured by flow cytometry using an Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences). More than 90 X 103 individual cells were analyzed for each condition using BD Accuri C6 software. Expression of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct in SOS reporter strains bearing the lacO250 array was pre-induced overnight in the presence of 0.2% arabinose and the same concentration of arabinose was present in the cultures during treatments with MMS. When needed, IPTG (1 mM) was also added to the overnight cultures and the cultures during treatments with MMS.

Measuring sensitivity to HU, MMS, NFZ, and overproduced proteins

Overnight cultures were diluted in LB to OD600 = 1.0 and serially diluted by 10 to 106 fold. Serially diluted cultures were spotted on LB agar plates containing indicated concentrations of aTc, MMS, NFZ, or HU. For sensitivity assays with strains for ectopic SSB-Ct clusters, indicated concentrations of arabinose were added to LB agar plates. When indicated, plates also contained 1 mM IPTG. To keep pBAD24, 100 or 50 μg/ml of ampicillin was added to liquid cultures or LB agar plates respectively. Plates were photographed after a 20-hour incubation at 37 °C.

Viable cell counting

LB containing 100 μg/ml ampicillin was inoculated with assay strains for ectopic SSB-Ct clusters and cultured overnight on a roller drum at 37 °C. Overnight cultures were appropriately diluted and plated on LB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg/ml ampicillin, 20% arabinose, and 6 μM NFZ (or dimethylformamide). Plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours and colonies were counted.

E. coli strains and plasmids

Refer to Supplementary Table 1 and 2 for E. coli strains and plasmids used in this study.

Construction of E. coli strains

General approach

Strains were constructed as previously described65. Briefly, mutations including insertions were introduced into the E. coli genome by lambda Red recombinase-mediated allelic exchange69. frt-flanked antibiotic selection markers were used to either disrupt a gene or to create a linkage to an allele of interest for P1 transduction.

Strains bearing a tetracycline-inducible (ptet) expression cassette

The Z2 locus, which bears expression cassettes for tetR and lacIq8 was transferred to MG1655 by P1 transduction. In the resulting strain (MG1655 Z2 (JEK522), refer to Supplementary Table 1), a tetracycline-inducible expression cassette (t1ccctatcagtgatagagattgacatccctatcagtgatagagatactgagcactac tagagaaagaggagaaatactagatggactacaaagacgatgacgacaaggaattctagtgctagtgtagatcgctactagagccaggcatcaaataaaacgaaaggctcagtcgaaagactgggcctttcgttttatctgttgtttgtcggtgaacgctctc220tactagag; two tetO sites (1-54), a RBS (63-74), a FLAG epitope coding sequence (81-107), EcoR I site (108-113), T1 terminator of the E. coli rrnB (141-220)) followed by frt-kan-frt was inserted between 621 and 658 nucleotides of lamB by lambda Red recombinase-mediated allelic exchange, generating MG1655 ΔlamB::ptet-frt-kan-frt. To insert a coding sequence to be induced into the expression cassette, the kan cassette was first flipped out by transiently expressing flippase in MG1655 ΔlamB::ptet-frt-kan-frt, resulting in MG1655 ΔlamB::ptet-frt. Then, the remaining frt and flanking elements were replaced with the coding sequence of interest either with N-terminal flag or without flag followed by frt-kan-frt through lambda Red recombinase-mediated allelic exchange. Tet-inducible expression strains created in this way lack T1 terminator. Various alleles of interest were also introduced into the inducible strains by P1 transduction.

Making deletion strains

Corresponding genes were replaced with frt-cm-frt or frt-kan-frt by lambda Red recombinase-mediated allelic exchange.

Making endogenous fusions to the RecQWH domain of the E. coli recQ

The sequence for linker-recQWH-frt-kan-frt was inserted in frame to the 3’ end of the last coding sequence of a host gene in the E. coli genome by lambda Red recombinase-mediated allelic exchange (Supplementary Fig. 5k). Linker, SAGSAAGSGEF71; RecQWH, amino acid number 408 to 523 of RecQ.

Making strains for ectopic SSB-Ct clusters

All the strains were based on AB1157 and AB1157 bearing the lacO250 array (IL05). To knock out dinB in AB1157 and IL05, dinB was replaced with frt-cm-frt by lambda Red recombinase-mediated allelic exchange. These strains were transformed with pBAD24, pBAD24-lacI, pBAD24-lacIΔC11, pBAD24-lacIΔC11-ssbIDL-Ct, pBAD24-lacIΔC11-ssb-ct, pBAD24-lacIΔC11-ssbIDL-CtDA,ΔF or pBAD24-lacIΔC11-ssb-ctDA,ΔF. lacIΔC11 is a coding sequence for LacI that lacks C-terminal 11 amino acids. ssbIDL is a coding sequence for SSBIDL (a.a. 113 to 168 of SSB). ssb-ct is a coding sequence for C-terminal 11 amino acids of E. coli SSB (PPMDFDDDIPF). ssb-ctDA,ΔF is a coding sequence for mutated SSB-Ct (PPMAFAAAIP).

Making imaging strains

dinB::dinB-PAmCherry-frt-kan-frt and its dinB variants were created in MG1655 as previously described72 and transferred into MG1655 ΔlacZ::ssb-mypet-frt lexA51 sulA211 (JEK762) by P1 transduction. polA::polA-PAmCherry-frt-kan-frt in AB115771 was transferred into JKE762 by P1 transduction. The sequence encoding a linker (SAGSAAGSGEF) is inserted between polA and PAmCherry.

Rolling circle replication

Construction of control and lesion-containing rolling circle DNA templates

Rolling circle templates were constructed as previously described65. Briefly, a lesion-containing oligomer (N2-furfuryl dG, 5’-CTACCT/N2-furfuryl dG/TGGACGGCTGCGA-3’; 3-deaza-methyl dA, GCTCGTCAGACG/3-deaza-3-methylA/TTTAGAGTCTGCAGTG)68,73 was ligated into EcoRI-linearized M13mp7L2, generating a lesion-containing closed circular ssDNA. This circular ssDNA was converted into 5’-tailed dsDNA by T7 DNA polymerase-catalyzed extension of a primer (N2-furfuryl dG, T36GAATTTCGCAGCCGTCCACAGGTAGCACTGAATCATG; 3-deaza-methyl dA, T36-TTCACTGCAGACTCTAAATCGTCTGACGAGCCACTGA) that was annealed over the lesion-containing region of the circular ssDNA. Control templates were constructed in the same way but with lesion-free oligomers of the same sequences.

Rolling circle replication

Rolling circle replication was performed as previously described65 (Fig. 2a). Briefly, the E. coli replisome was reconstituted on either a control or a lesion-containing rolling circle template with purified replisome components. To assemble replisomes, a mixture of a rolling circle template (1 nM), τ3δδ’χψ (20 nM), Pol III core (20 nM), β2 clamp (20 nM), DnaB6 (50 nM), ATPγS (50 μM) and dCTP/dGTP (60 μM) was prepared in HM buffer (50 mM Hepes-KOH pH 7.9, 12 mM Mg(OAc)2, 0.1 mg/mL BSA and 10 mM DTT) on ice and then incubated at 37 °C for 6 min. After the assembly, replication reactions were initiated by adding a 10X initiation mixture (1 mM ATP, 250 μM each CTP/GTP/UTP, 60 μM each dATP/dTTP, [α−32P]-dATP, 500 μM SSB4, 100 nM DnaG). After incubation at 37 °C for 12 min, unless otherwise indicated, replication reactions were quenched by adding EDTA (25 mM final). All the concentrations are final concentrations in the replication reactions.

Replication products were separated in a 0.6% alkaline denaturing alkaline agarose gel and visualized by autoradiography. Radioactive signals were quantified using ImageJ. Leading strand synthesis was quantified by integrating signals above the template or at the resolution limit when indicated. These values for the lesion-containing template were defined as “in vitro TLS”. Relative band intensities were calculated with respect to the maximal band intensity in the presence of Pol IV.

Western blot

The expression levels of different Pol IV-PAmCherry fusion proteins were measured by Western blot as previously described72. Cell lysates of imaging strains expressing different C-terminally FLAG-tagged Pol IV-PAmCherry variants were probed with an anti-FLAG antibody or an anti-RpoA antibody for Pol IV-PAmCherry-FLAG and RpoA, a loading control, respectively.

Cultures were grown in 50 mL volumes following the same growth procedure as in imaging experiments. Cells were harvested at OD600nm ≈ 0.15, resuspended in 1 mL chilled DI H2O, and pelleted again. The cell pellet was resuspended and lysed in B-PER Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific, #78248) supplemented with lysozyme (EMD, #5950), Benzonase nuclease (Novagen, #70746), and EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, #04693159001).

Samples were run on an SDS-PAGE gel (Bio-Rad #4561086: 4-15 Mini-PROTEAN TGX) along with BioReagents EZ-Run Prestained Rec Protein Ladder (Fisher #BP3603), then transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PerkinElmer, #NEF1002001PK: PolyScreen PVDF Hybridization Transfer Membrane). After blocked in TBST containing 5% skim milk, one membrane was probed with a 1:5,000 dilution of a rabbit anti-FLAG antibody raised against the antigen Ac-C(dPEG4)DYKDDDDK-OH (a gift of Johannes Walter, Harvard Medical School) and the other was probed with a 1:5,000 dilution of a mouse anti-RpoA monoclonal antibody (BioLegend, #663104; Clone 4RA2, Isotype Mouse IgG1). A goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, #111-035-003) and a rabbit anti-mouse IgG-HRP antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, #315-035-003) were used at 1:20,000 dilutions as secondary antibodies for the anti-FLAG and the anti-RpoA blots respectively. The membranes were visualized using an Amersham Imager 600 with HyGLO chemiluminescent HRP antibody detection reagent (Denville Scientific, #E2400).

To determine the expression levels of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct and Ct-DA,ΔF, overnight cultures were diluted to OD600nm ≈ 0.1 and incubated at 37 °C with aeration for 2 hours before cells were harvested. The expression of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct and Ct-DA,ΔF was induced as described above (see “Measuring the damage-induced SOS response”). Based on OD600nm at the time of harvest, an equal number of cells were loaded for SDS PAGE. The expression levels of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct and Ct-DA,ΔF were measured by Western blot with a 1:2,000 dilution of a rabbit polyclonal antibody against LacI (Antibodies-online, ABIN964896) as described above.

Circular Dichroism

The protein storage buffer for purified Pol IV and Pol IVT120P was exchanged for 10 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) with Micro Bio-Spin P-30 Chromatography Columns (Bio-RAD) right before the measurements. Circular dichroism of the buffer-exchanged Pol IV and Pol IVT120P at 1 μM was measured using a CD spectropolarimeter (Jasco J-815) with a Peltier temperature controller. To monitor thermal denaturation, dichroic activities of Pol IV and Pol IVT120P at 222 nm were recorded at varying temperatures.

In vivo TLS assays

In vivo TLS assay strains

All in vivo TLS assay strains are derivatives of strains FBG151 and FBG15274,75. Various dinB, polB, and umuDC alleles were introduced to the in vivo TLS assay strains by P1 transduction and selected for linked-selection markers, and then selection markers were flipped out by transient expression of flippase. The in vivo TLS assay strains used in this study also carry the plasmid pVP135, which allows IPTG-inducible expression of the int–xis genes for site-specific genomic integration of lesion-containing or control plasmids.

In vivo assay to measure TLS

In vivo assays were performed as previously described75. 40 μL of electrocompetent cells were transformed with 1 ng of the lesion-containing plasmid mixed with 1 ng of pVP146 (internal control for transformation efficiency) by electroporation using a GenePulser Xcell (BioRad) at 2.5 kV, 25 μF and 200 Ω. Transformed cells were first resuspended in 1 mL of super optimal broth with catabolic repressor (SOC), and then 500 μL of the cell resuspension was transferred into 2 mL LB containing 0.2 mM IPTG. This cell suspension was incubated for 45 min at 37 °C. A part of the culture was plated on LB-agar containing 10 μg/mL tetracycline to measure the transformation efficiency of plasmid pVP146, and the rest was plated on LB containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin and 80 μg/mL X-gal to select for integrants (AmpR) and detect TLS events (lacZ+ phenotype). Following the site-specific integration, the N2-furfuryl dG lesion is located either in the lagging strand (FBG151 derived strains) or in the leading strand (FBG152 derived strains). Cells were diluted and plated using the automatic serial diluter and plater EasySpiral Dilute (Interscience). Colonies were counted using the Scan 1200 automatic colony counter (Interscience). The integration rate was about 2,000 clones per picogram of a plasmid for a wild-type strain. Transformed cells were plated before the first cell division, and therefore, following the integration of the lesion-containing plasmid, blue-sectored colonies represent TLS events and pure white colonies represent damage avoidance (DA) events. The relative integration efficiencies of lesion-containing plasmids compared with their lesion-free equivalent and normalized by the transformation efficiency of pVP146 plasmid in the same electroporation experiment, allow the overall rate of lesion tolerance to be measured.

A total of 300 - 1500 colonies was counted in triplicate measurements for each strain, and such measurements were independently repeated at least three times. From these measurements, means and standard deviations were determined, and statistical comparisons between indicated samples were performed by two-tailed Welch’s t-test.

PALM Imaging

Sample preparation for microscopy and MMS treatment

Samples were prepared for microscopy following previously reported procedures72. In brief, glycerol stocks were streaked on LB plates containing 30 μg/mL kanamycin when appropriate. The day before imaging, a 3 mL “overday” LB culture was inoculated with a single colony and incubated for approximately 8 h at 37 °C on a roller drum. An overnight culture was prepared in 3 mL M9 medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 1 mM thiamine hydrochloride, 0.2% casamino acids, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM CaCl2, and 0.5 mM IPTG to induce expression of ssb-mypet. This overnight culture was inoculated with a 1:1,000 dilution of the overday culture and incubated overnight on a roller drum at 37 °C. On the day of imaging, 50 mL cultures in supplemented M9 medium were inoculated with a 1:200 dilution of the overnight culture and incubated at 37 °C shaking at 225 rpm. Previously we demonstrated that the induction of SSB-mYPet had no impact on cell growth72.

Cells were harvested for imaging in early exponential phase when OD600nm ≈ 0.15. Aliquots were removed and concentrated by centrifugation, then the concentrated cell suspension was deposited on an agarose pad sandwiched between cleaned coverslips. The coverslip in the optical path was cleaned by two 30 min cycles of sonication in ethanol and 1 M KOH and stored in deionized water. Agarose pads were prepared by heating 3% GTG agarose (NuSieve) in M9 medium supplemented with 0.4% glucose, 2 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM CaCl2, then casting a 500 μL volume of molten agarose between two cleaned 25 × 25 mm coverslips. For MMS treatment, MMS was added to the molten agarose at 100 mM immediately before casting the pad. Cells were incubated on the MMS agarose pad in a humidified chamber at RT for 20 min before imaging.

Microscopy

Imaging was performed on a customized Nikon TE2000 microscope described previously72. Briefly, 405 nm (Coherent OBIS, 100 mW) and 561 nm (Coherent Sapphire, 200 mW) laser excitation was used to activate and excite PAmCherry, and 514 nm (Coherent Sapphire, 150 mW) laser excitation was used to excite mYPet. Imaging was carried out with highly inclined thin illumination76, or near-TIRF illumination, by focusing the beams to the back focal plane of a Nikon CFI Apo 100X/1.49 NA TIRF objective. The microscope was equipped with Chroma dichroic and emission filters (91032 Laser TIRF Cube containing a ZT405/514/561rpc dichroic filter, ZET442/514/561m emission filter, and ET525lp longpass filter). A Hamamatsu ImageEM C9100-13 EMCCD camera running HCIMage Live software was used to record images with 250 ms exposure time. For all two-color PALM movies, the excitation sequence commenced with a high-power pre-bleaching period of 50 frames (~ 120 W cm−2 561 nm excitation) was followed by 10 frames of low-power pre-bleaching (~ 12.5 W cm−2 561 nm power). Then 10 frames were recorded to image SSB-mYPet (~ 0.4 W cm−2 514 nm power). Finally, PAmCherry fusions were activated and excited by continuous 405 nm (starting at ~ 2.5 mW cm−2 power and increasing to ~ 17.5 mW cm−2 power) and 561 nm (~ 12.5 W cm−2 power) illumination. Excitation sequences were automated using LabVIEW (National Instruments) software. White light transillumination was used for the acquisition of brightfield images of cells. All imaging experiments were repeated for at least three biological replicates (imaging cultures) on at least two different days.

Image analysis

As described previously72, image analysis was performed in MATLAB using MicrobeTracker77 for cell segmentation, u-track for spot detection and tracking78, and custom codes for other analyses. The point source detection algorithm79 in u-track was used to detect mYPet and PAmCherry fusions and to fit them to 2D Gaussian point spread functions (PSFs). For PAmCherry fusions, a significance threshold of α = 10−6 was applied. Static tracks were identified by comparing the mean width of the PSF to the distribution in fixed cells; mobile molecules have broader PSFs due to motion blurring71. Tracks with mean PSF width between 85.5 and 211.0 nm were determined to be static based on previous measurements72. A small number of cells containing PAmCherry localizations in the first PALM frame were excluded from analysis as a precaution against cross-talk from the mYPet channel. For SSB-mYPet, the first 5 frames of 514 nm excitation were averaged and analyzed with a significance threshold of α = 10−5. To remove a small number of poorly-fit foci, detected spots with a background level below the camera offset level (1,500 counts) were rejected. Other analysis parameters are as described previously72.

Colocalization analysis between SSB-mYPet foci and PAmCherry fusions to Pol IV and RecQWH-Pol IVLF variants was performed as previously described72. In brief, the mean distance between each static Pol IV (or RecQWH-Pol IVLF) track and the closest SSB focus was measured for each cell. These raw distances were aggregated across all cells and plotted. Additionally, radial distribution function analysis80,81 was used to determine the increased likelihood of localization at a distance r from the centroid of an SSB focus relative to random localization in the cell. For each cell, the raw Pol IV-SSB distances were measured; then random Pol IV-SSB distances were calculated by generating the same number of random Pol IV localizations within the same cell outline and keeping the same SSB centroid positions. After repeating this procedure for all cells, the experimental distance distribution was normalized by the random distribution, yielding the radial distribution function g(r). This approach was repeated 100 times and the resulting g(r) curves were averaged to give the final result. Additionally, an independent random Pol IV-SSB distance distribution was generated, and 100 random g(r) curves were averaged in the same way to give a mean random g(r) curve. Values of the experimental g(r) curves greater than 1 indicate enrichment relative to a random distribution, whereas deviations of the random g(r) curves from 1 indicate errors due to the finite sample size. This procedure and representative mean g(r) and replicates are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3b–d.

Statistics and Reproducibility

All the results presented here were reproduced at least three times with independently prepared samples unless indicated otherwise. For imaging experiments, a small number of individual cells were excluded from analysis following the criteria specified in the “Methods” section. There was no blinding during imaging data collection and analysis because procedures were standardized and automated using computer code. For in vivo TLS assays, no results were excluded from analysis.

Extended Data

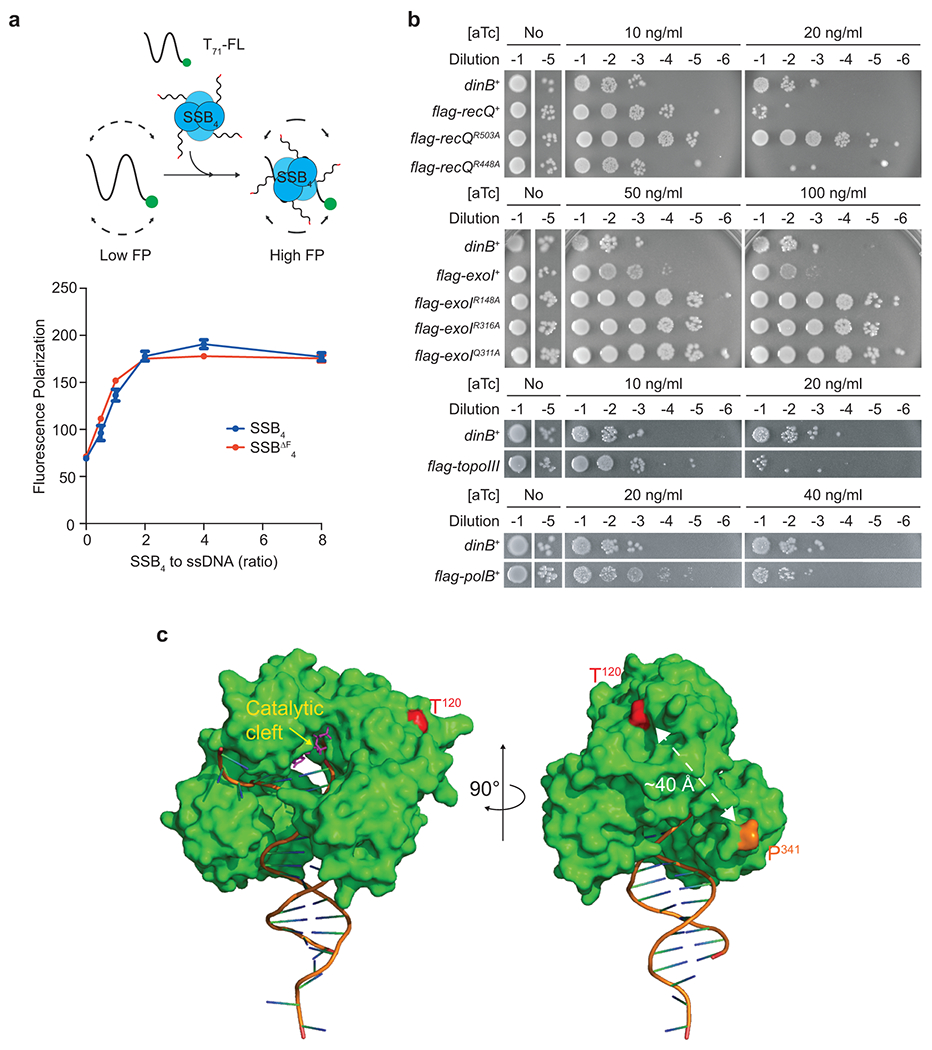

Extended Data Fig. 1. An SSB-binding defective mutant Pol IV.

a. Formation of nucleoprotein complexes between SSB4 or SSBΔF4 and ssDNA. (Top) An FP-based binding assay scheme. (Bottom) Interaction of T71-FL with SSB4 or SSBΔF4 was measured by changes in FP. Means ± ranges of duplicate measurements. Similar results were reproduced twice.

b. Over-expression-induced cell death by RecQ, Exonuclease I, Topoisomerase III, Pol II, or their variants. R503A of RecQ, and R418A, R316A, and Q311A of Exonuclease I, SSB-binding mutations; R448A of RecQ, a negative control mutation; flag, N-terminal FLAG epitope; exoI, topoIII, and polB, coding sequences for exonuclease I, topoisomerase III, and Pol II respectively.

c. Location of T120 within Pol IV. (Left) A front view showing the location of T120 relative to the catalytic cleft (yellow arrow). (Right) A side view showing the location of T120 relative to the C-terminal end (P341). C-terminal unstructured region (a.a. 342–351) containing the clamp interacting motif (a.a. 346–351) is missing in the structure. A crystal structure of E. coli Pol IV (PDB 4q43) is modified.

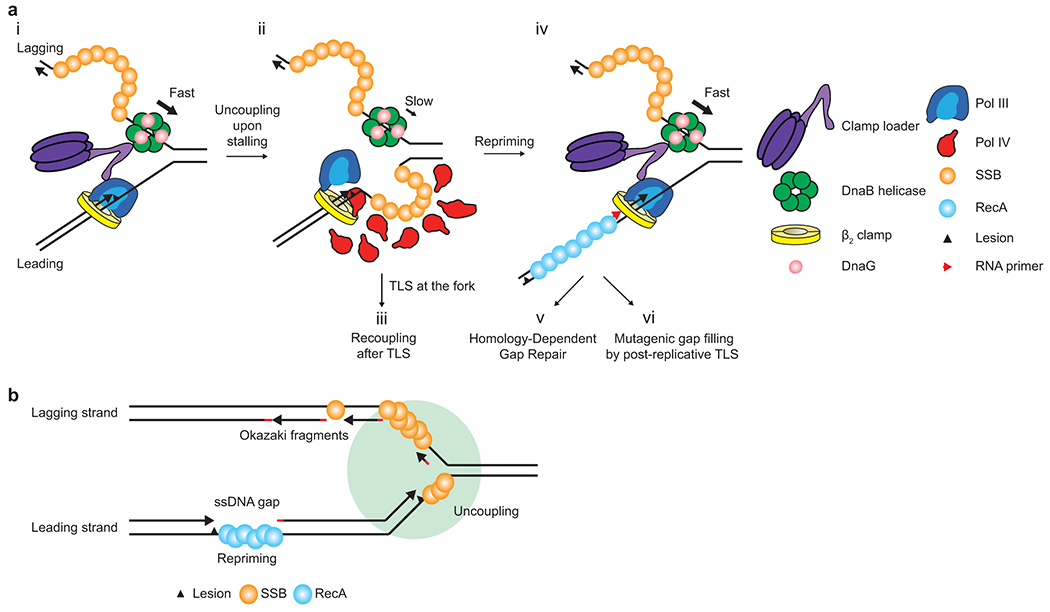

Extended Data Fig. 2. Fates of stalled replication and associated replication products in our rolling circle replication-based assays.

In these rolling circle DNA templates, the lesion-containing closed circular DNA is the template for leading strand synthesis. During rolling circle DNA replication, the growing leading strand serve as the template for lagging strand synthesis.

Extended Data Fig. 3. Pol IV must bind to the β2 clamp to mediate TLS at the fork.

The N2-FFdG-containing template was replicated in the presence of indicated concentrations of Pol IV or Pol IVΔC6 as shown in Fig. 2a. Pol IVΔC6, a mutant Pol IV lacking the C-terminal clamp binding motif.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Monitoring resolution pathway choice in cells.

a. Clamp binding mutations of dnaQ. dnaQ(εQ), weakening mutation; dnaQ(εL), strengthening mutation.

b. (Left) Site-specific insertion of a single N2-FFdG adduct into the E. coli genome in either the leading or lagging strand template. (Right) Resolution of lesion-stalled replication through TLS leads to the formation of blue-sectored colonies. White colonies represent resolution through DA.

c. Deletion of lafU, which is replaced with an frt-kan-frt cassette as a dinB-linked marker for P1 transduction, does not influence pathway choice of N2-FFdG-stalled replisomes in cells. In all ΔlafU-containing strains, the kan cassette was flipped out. Means ± SDs (n = 6 for lafU+; n = 3 for ΔlafU; n, number of independent experiments).

d. TLS over N2-FFdG in cells is primarily mediated by Pol IV. Deleting dinB reduces the resolution of N2-FFdG-stalled replisomes through TLS from ~60 to ~30%. Additional deletion of both polB and umuDC does not further reduce resolution through TLS. The residual TLS (~30%) in the ΔdinB ΔpolB ΔumuDC background is presumably mediated by Pol III. However, as Pol IV outcompetes Pol III in mediating TLS over N2-FFdG, the actual contribution of Pol III to TLS in the dinB+ background is likely less than estimated in the ΔdinB background. Ld, leading strand lesion; Lg, lagging strand lesion. Means ± SDs (n = 3; n, number of independent experiments). The statistical significance of the difference between the indicated pairs was determined by two-tailed Welch’s t-test; numbers, p values.

e. Weakening the SSB-Pol IV interaction increases the MMS-induced SOS response. (Left) Resolution of stalled replication through repriming results in induction of the SOS damage response. TLS at the fork inhibits repriming. (Right) The MMS-induced SOS response in strains bearing indicated dinB alleles. The SOS reporter strains express green fluorescent protein (GFP) from a genomic expression cassette, in which the transcription of gfp is under the control of the sulA promoter (see “Methods” for details). dinBplexA, a LexA binding site mutant of the dinB promoter. Fluorescence intensities from single cells were measured for more than 90 X 103 cells using a flow cytometer. Means ± SDs (n > 90 X 103). The statistical significance of the difference between indicated pairs was determined by an unpaired t-test. ****, p<0.0001. Similar results were reproduced twice.

Extended Data Fig. 5. SSB-driven ectopic localization of CLIPs.

a. Viable cell counts for +lacO250 dinB+ or ΔdinB strains (Fig. 5a) upon induction of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct (Ct), LacIΔC11-ssb-CtDA,ΔF (CtDA,ΔF) or mock (−). Means ± SDs of triplicate measurements. Similar results were reproduced twice.

b. Sensitivity of indicated assay strains to MMS upon induction of Ct or CtDA,ΔF.

c. The C-terminal unstructured linker of SSB (SSBIDL in Fig. 1a) is not necessary for the formation of an ectopic SSB-Ct cluster that sensitizes cells to NFZ. Expression of LacIΔC11-SSB-Ct (Ct) or LacIΔC11-SSBIDL-Ct (IDL-Ct) comparably sensitized cells to NFZ. Addition of IPTG or binding mutations on SSB-Ct (CtDA,ΔF) eliminated this sensitization. SSBIDL-Ct, the entire C terminal unstructured linker of SSB including both SSBIDL and SSB-Ct.

d. Sensitivity of the indicated strains to NFZ. Similar results were reproduced twice.

e. Sensitivity of indicated assay strains to HU upon induction of Ct or CtDA,ΔF. Similar results were reproduced twice.

f. ΔdinB is epistatic to polA-recQWH or hda-recQWH in sensitivity to NFZ. Sensitivity of the indicated strains to NFZ. polA- or hda-recQWH, the coding sequence for Pol I- or Hda-RecQWH.

g. Sensitivity of indicated strains to NFZ. hda-recQWH or WH(R425A,R503A), the coding sequence for Hda-RecQWH or WH(R425A,R503A).

h. Over-production of Crfc-RecQWH results in massive cell death. Expression of indicated genes was induced from a Tet-inducible genomic expression cassette. crfc-recQWH or WH(R425A,R503A), the coding sequence for Crfc-RecQWH or WH(R425A,R503A). Similar results were reproduced twice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kelly Arnett (Center for Macromolecular Interactions, Harvard Medical School) for training and assistance in using a CD spectropolarimeter, James Keck (University of Wisconsin, Madison) for providing the fluorescein-conjugated SSB-Ct peptide, Deyu Li (University of Rhode Island) for providing the N2-FFdG-containing oligomer, James Kath (Harvard Medical School) for construction of tetracycline-inducible strains and Slobodan Jergic (University of Wollongong) for providing the various purified Pol III polymerase complexes and helpful discussions. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 GM114065 (to J.J.L.), The William F. Milton Fund (to S.C.), F32 GM113516 (to E.S.T.), and Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) Grant [GenoBlock ANR-14-CE09-0010-01] (to V.P.).

Footnotes

Code availability

The custom-written computer codes from the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review Information:

Nature Structural and Molecular Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

The data sets from the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. A structure of E. coli Pol IV was retrieved from the PDB with accession code 4q43 (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/4Q43). Source data are provided with this paper

References

- 1.Fuchs RP & Fujii S Translesion DNA synthesis and mutagenesis in prokaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5 a012682 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moldovan G-L, Pfander B & Jentsch S PCNA, the maestro of the replication fork. Cell 129 665–679 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalrymple BP, Kongsuwan K, Wijffels G, Dixon NE & Jennings PA A universal protein-protein interaction motif in the eubacterial DNA replication and repair systems. 98 11627–11632 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Georgescu RE et al. Structure of a sliding clamp on DNA. Cell 132 43–54 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krishna TS, Kong XP, Gary S, Burgers PM & Kuriyan J Crystal structure of the eukaryotic DNA polymerase processivity factor PCNA. Cell 79 1233–1243 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunting KA, Roe SM & Pearl LH Structural basis for recruitment of translesion DNA polymerase Pol IV/DinB to the beta-clamp. EMBO J. 22 5883–5892 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patoli AA, Winter JA & Bunting KA The UmuC subunit of the E. coli DNA polymerase V shows a unique interaction with the β-clamp processivity factor. BMC Struct. Biol 13 12 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.López de Saro FJ & O’Donnell M Interaction of the beta sliding clamp with MutS, ligase, and DNA polymerase I. 98 8376–8380 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurz M, Dalrymple B, Wijffels G & Kongsuwan K Interaction of the sliding clamp beta-subunit and Hda, a DnaA-related protein. Journal of Bacteriology 186 3508–3515 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozaki S et al. A replicase clamp-binding dynamin-like protein promotes colocalization of nascent DNA strands and equipartitioning of chromosomes in E. coli. CellReports 4 985–995 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeruzalmi D et al. Mechanism of processivity clamp opening by the delta subunit wrench of the clamp loader complex of E. coli DNA polymerase III. Cell 106 417–428 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan KW, Pham TM, Furukohri A, Maki H & Akiyama MT Recombinase and translesion DNA polymerase decrease the speed of replication fork progression during the DNA damage response in Escherichia coli cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 1714–1725 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pluciennik A, Burdett V, Lukianova O, O’Donnell M & Modrich P Involvement of the Clamp in Methyl-directed Mismatch Repair in Vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry 284 32782–32791 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furukohri A, Nishikawa Y, Akiyama MT & Maki H Interaction between Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV and single-stranded DNA-binding protein is required for DNA synthesis on SSB-coated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 6039–6048 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arad G, Hendel A, Urbanke C, Curth U & Livneh Z Single-stranded DNA-binding protein recruits DNA polymerase V to primer termini on RecA-coated DNA. J. Biol. Chem 283 8274–8282 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molineux IJ & Gefter ML Properties of the Escherichia coli in DNA binding (unwinding) protein: interaction with DNA polymerase and DNA. 71 3858–3862 (1974). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shereda RD, Kozlov AG, Lohman TM, Cox MM & Keck JL SSB as an organizer/mobilizer of genome maintenance complexes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol 43 289–318 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang S et al. A gatekeeping function of the replicative polymerase controls pathway choice in the resolution of lesion-stalled replisomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 116 25591–25601 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigal N, Delius H, Kornberg T, Gefter ML & Alberts B A DNA-unwinding protein isolated from Escherichia coli: its interaction with DNA and with DNA polymerases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 69 3537–3541 (1972). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shereda RD, Reiter NJ, Butcher SE & Keck JL Identification of the SSB binding site on E. coli RecQ reveals a conserved surface for binding SSB’s C terminus. J. Mol. Biol 386 612–625 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryzhikov M, Koroleva O, Postnov D, Tran A & Korolev S Mechanism of RecO recruitment to DNA by single-stranded DNA binding protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 39 6305–6314 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchida K et al. Overproduction of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase DinB (Pol IV) inhibits replication fork progression and is lethal. Mol. Microbiol 70 608–622 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scotland MK et al. A Genetic Selection for dinB Mutants Reveals an Interaction between DNA Polymerase IV and the Replicative Polymerase That Is Required for Translesion Synthesis. PLoS Genet. 11 e1005507 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarosz DF, Godoy VG, Delaney JC, Essigmann JM & Walker GC A single amino acid governs enhanced activity of DinB DNA polymerases on damaged templates. Nature 439 225–228 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bjedov I et al. Involvement of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase IV in tolerance of cytotoxic alkylating DNA lesions in vivo. Genetics 176 1431–1440 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heltzel JMH, Maul RW, Scouten Ponticelli SK & Sutton MD A model for DNA polymerase switching involving a single cleft and the rim of the sliding clamp. 106 12664–12669 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benson RW, Cafarelli TM, Rands TJ, Lin I & Godoy VG Selection of dinB alleles suppressing survival loss upon dinB overexpression in Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology 196 3023–3035 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Indiani C, Langston LD, Yurieva O, Goodman MF & O’Donnell M Translesion DNA polymerases remodel the replisome and alter the speed of the replicative helicase. 106 6031–6038 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thrall ES, Kath JE, Chang S & Loparo JJ Single-molecule imaging reveals multiple pathways for the recruitment of translesion polymerases after DNA damage. Nat Commun 8 2170 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uphoff S, Reyes-Lamothe R, Garza de Leon F, Sherratt DJ & Kapanidis AN Single-molecule DNA repair in live bacteria. 110 8063–8068 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godoy VG et al. UmuD and RecA directly modulate the mutagenic potential of the Y family DNA polymerase DinB. Mol. Cell 28 1058–1070 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sladewski TE, Hetrick KM & Foster PL Escherichia coli Rep DNA helicase and error-prone DNA polymerase IV interact physically and functionally. Mol. Microbiol 80 524–541 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen SE, Godoy VG & Walker GC Transcriptional modulator NusA interacts with translesion DNA polymerases in Escherichia coli. Journal of Bacteriology 191 665–672 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cafarelli TM, Rands TJ & Godoy VG The DinB•RecA complex of Escherichia coli mediates an efficient and high-fidelity response to ubiquitous alkylation lesions. Environ. Mol. Mutagen 55 92–102 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kath JE et al. Polymerase exchange on single DNA molecules reveals processivity clamp control of translesion synthesis. 111 7647–7652 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jergic S et al. A direct proofreader-clamp interaction stabilizes the Pol III replicase in the polymerization mode. EMBO J. (2013). doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagès V, Mazón G, Naiman K, Philippin G & Fuchs RP Monitoring bypass of single replication-blocking lesions by damage avoidance in the Escherichia coli chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 9036–9043 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]