Abstract

Introduction:

Persons living with HIV (PLWH) are at increased risk for osteoporosis and fracture. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) has been associated with higher rates of bone mineral density (BMD) loss, osteoporosis and fracture. Few studies have studied the impact among PLWH in Asia.

Methods:

We analyzed retrospectively patients from the outpatient HIV clinic of a large tertiary hospital in Beijing, China, from March 2007 to May 2016. Patients who had dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry testing prior to antiretroviral initiation, and at 48 and/or 96 weeks after initiation were included in this analysis.

Results:

A total of 136 patients were included (mean age 36.0±10.6 years) and over 90% participants were male and Han Chinese ethnicity. We observed greater declines in BMD at the spine from baseline to week 48 (−2.94% vs. −0.74%) and at the hip from baseline to week 96 (−4.37% vs.−2.34%) in the TDF group compared with the non-TDF group. With regards to HIV-specific parameters, longer duration since HIV diagnosis and undetectable viral load over time were associated with lower BMD at the hip [Relative risk (RR) 0.97, 95% confidence index (CI) (0.95, 0.99) per 1 year increase and RR 0.96, 95%CI (0.94, 0.99), respectively] and femoral neck [RR 0.97, 95%CI (0.95, 0.99) per 1 year increase and RR 0.97, 95%CI (0.95, 0.998), respectively] over 96 weeks.

Conclusions:

This is the first study to report changes in BMD among PLWH after initiation of TDF-based antiretroviral therapy in China. Our findings provide important knowledge for the long-term clinical management of PLWH from this region.

Keywords: Human immunodeficiency virus, bone mineral density, fracture, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, protease inhibitors

Summary

This is the first study to report changes in BMD and related risk factors among Chinese patients with HIV after initiation of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)-containing antiretroviral therapy. Greater bone mineral density (BMD) loss was observed in patients treated with TDF, compared to those on non-TDF-containing regimens. Our findings provide important knowledge regarding the risk factors in the long-term clinical management of patients with HIV in China.

INTRODUCTION

Persons living with HIV (PLWH) are at increased risk for low bone mineral density (BMD) and osteoporosis [1], due to a combination of traditional risk factors, HIV infection itself and antiretroviral therapy (ART) [2,3]. Certain antiretrovirals, such as tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), a nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor widely used globally as the backbone of combined ART, have been associated with higher rates of BMD loss, osteoporosis and fracture [4,5]. Studies examining mechanisms of TDF-induced BMD loss have identified alterations in urinary phosphate wasting due to renal proximal tubulopathy [6] potential alteration of vitamin D metabolism or bioavailability leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism [7,8], and potential direct effects of TDF on osteoblasts, the cells responsible for bone formation [9], in addition, recent studies have suggested that inflammation [10] and immune regenerative events associated with CD4+ T cell reconstitution are important drivers of bone loss associated with all ART, including TDF [11–13].

Longitudinal studies in upper-income countries have found that TDF-based ART regimens lead to 1–3% greater decline compared with other ART regimens containing abacavir (ABC), maraviroc, and tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) [14–18]. However due to its excellent efficacy for HIV treatment, and low cost compared to newer agents, TDF remains the cornerstone of HIV treatment and pre-exposure prophylaxis regimens in many settings. An estimated 850,000 individuals are infected with HIV in China, and incidence of newly diagnosed cases continues to rise, particularly in high risk groups such as men who have sex with men [19]. The China National Free AIDS Treatment Program (NFATP) provides antiretroviral therapy free of charge to Chinese patients with a confirmed HIV diagnosis [20], and since 2012, the first line regimen has consisted of TDF, combined with lamivudine (3TC) and efavirenz (EFV).

Only one study to date has reported longitudinal BMD changes among persons with HIV in China [21], and none have evaluated BMD among patients treated with TDF-based regimens. Previous biomarker studies have suggested that Chinese patients treated with tenofovir-based regimens experience pronounced increases in bone metabolism (as reflected by bone turnover markers) during the two years after ART initiation, particularly in bone resorption [7,8]. Additionally, a small pharmacokinetic study by Du et al., observed higher plasma exposure [as measured by Cmax and area under the curve (AUC)]and slower rates of elimination of TDF compared with studies from Caucasian or African populations [22–24]. Therefore, understanding the impact of tenofovir on clinical outcomes such as bone mineral density and fracture among Chinese patients with HIV is highly important.

To address this gap, we retrospectively analyzed medical records data from patients receiving care for HIV at a large tertiary-care hospital in Beijing, China and evaluated change in BMD over 96 weeks after ART initiation and potential associations with clinical and HIV-associated characteristics. We hypothesized that patients receiving tenofovir-based regimens would demonstrate more pronounced change in BMD compared with patients on non-TDF containing regimens.

METHODOLOGY

Study Design & Population

We performed a retrospective analysis of data from patients seen at the outpatient HIV clinic of Peking Union Medical College Hospital in Beijing, China from March 2007 to May 2016. All outpatient clinic records were screened and patients were considered for inclusion if they had ever received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry test in the past. Those who had BMD evaluations at baseline, 48 and/or 96 weeks were included in this analysis. For the purposes of this analysis, we excluded patients who had significant renal, hepatic, thyroid or parathyroid dysfunction; malignancies; a history of wasting syndrome; use of systemic glucocorticoids; and use of anti-osteoporotic agents as these factors may independently influence BMD measures. This study was reviewed and exempt by the institutional review board of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China.

Measures

We collected data from each patient’s medical record regarding age, sex, body mass index (BMI), ethnicity, current smoking, current alcohol use, HIV route of transmission, HIV diagnosis date, ART treatment history, number of years since HIV diagnosis, baseline hepatitis surface B antigen and hepatitis C antibody status, viral load (log10 copies/ml) over time, and CD4+ T-cell count (cells/mm3) over time. If the patient had a history of fracture(s) since initiation of ART, data regarding location of the fracture and the nature of the fracture (traumatic v. non-traumatic) were noted in the medical record.

Combination ART regimens of patients included in the analysis reflected the different available antiretrovirals in China over the course of the study period[25], and were composed of:

Stavudine (d4T; Desano, Shanghai, China), zidovudine (AZT; Northeast General Pharmaceutical Factory, China) or TDF (Gilead Sciences Inc, USA); plus

Lamivudine (3TC; GlaxoSmithKline, UK); plus

Nevirapine (NVP; Desano, Shanghai, China), efavirenz (EFV; MSD, Australia), lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r; AbbVie Inc., USA), raltegravir (RAL; MSD, Australia) or dolutegravir (DTG; GlaxoSmithKline, UK).

Patients were categorized into the TDF-group if they consistently received TDF from the time of treatment initiation through the time of their last dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan, and into the non-TDF group if they did not meet the criteria.

All BMD measures at the lumbar spine (L1-L4), total hip, and femoral neck were measured at PUMCH by DXA using a GE Lunar Prodigy Advance PA+ 300388 machine (GE Healthcare, USA). All measurements were interpreted using GE Lunar software (enCORE version 10.50.086).

Plasma CD4+ and CD8+ cell counts were measured with three‑color flow cytometry (Beckman‑Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). For viral load (VL) measurements, the Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan real‑time RT‑PCR Assay (Roche, CA, USA) was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Definitions

For postmenopausal women and men aged 50 years or above, we used the World Health Organization categorization approach for bone mineral density based upon T-scores, which represent a standard deviation score of the patient’s BMD compared to BMD from a young healthy population (reflecting peak bone mass) of a reference population. Using this system, osteoporosis is defined as a T score ≤−2.5, and osteopenia as T-scores between −2.5 to −1.0. For pre-menopausal women and men younger than 50 years, we used Z-scores, which compare a young individual’s BMD to the mean of an age-, gender-, and ethnicity-matched reference population. Z-scores above −2.0 are considered within the normal range for age, and those below −2.0 are defined as “below the expected range for age” [26]. For the purposes of our analysis, we categorized patients as having low BMD if they had a T-score indicating osteoporosis or osteopenia, or Z-score “below the expected range for age” depending on which score was most appropriate to apply for that patient. Undetectable HIV viral load was imputed as the value of the lower limit of detection (20 copies/ml).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data were tabulated and reported using simple means, standard deviations, medians, interquartile ranges (IQR), and frequencies. The Student’s t-test for parametric continuous variables, Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric continuous variables, and the Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables were used to compare the clinical characteristics of patients in the TDF group versus non-TDF group. For evaluations of percent change in BMD over 96 weeks, stratification of patients in the TDF group was performed to enable comparison of those treated with TDF+3TC/EFV (EFV group) and those with TDF+3TC/LPV/r (LPV/r group).

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE analysis) was utilized to analyze the impact of covariates [age, sex, current smoking, current alcohol use, BMI, Han ethnicity, hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection, route of HIV transmission, years since HIV diagnosis, baseline CD4+ T-cell count, baseline HIV viral load, CD4+ T-cell count over time (categorized as <200, 200–500, and ≥500 cells/mm3), HIV viral load over time (dichotomized as undetectable and detectable HIV RNA results) and TDF exposure] per unit increase (g/cm2) in lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck BMD over time. Factors associated with p<0.20 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariable model.

The incidence rate of low BMD per 1000 person-years (PYs) during the observation period was calculated. Cox regression analysis was used to estimate hazard ratios, incorporating the same covariates in the model as included in the GEE analysis. Patients with low BMD at baseline were excluded and events were defined as incident low BMD by DXA at either 48 or 96 weeks. Factors associated with p<0.20 in the univariate analysis were entered into the multivariable model.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA) and Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). For all tests, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

From a total of 481 outpatients in the HIV clinic who had at least one DXA scan in the past, 136 patients were identified who met the criteria for inclusion in this analysis. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. The mean age was 36.0±10.6 years and mean BMI was 22.9±3.2 kg/m2, 91.2% of participants were male and 94.1% of participants were Han Chinese. The proportion of patients with HBV and HCV coinfection were 7.4% and 0.7% respectively. Mean CD4+ T-cell count was 256±186 cells/mm3, and HIV viral load was 4.7±0.7 log10 copies/ml.

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

| Characteristic | Total (N=136) | ART Regimen Group* |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TDF group (n=82) | Non-TDF group (n=40) | p | ||

|

| ||||

| Age (years) | 36.0±10.6 | 34.8±9.8 | 36.4±10.9 | 0.41 |

| ≥50 years | 18 (13.2%) | 9 (11.0%) | 5 (12.5%) | 0.80 |

| Male | 124 (91.2%) | 79 (96.3%) | 35 (87.5%) | 0.06 |

| Current smoking | 16 (11.8%) | 11 (13.4%) | 3 (7.5%) | 0.35 |

| Current alcohol use | 32 (23.5%) | 24 (29.3%) | 3 (7.5%) | 0.01 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 22.9±3.2 | 22.9±3.3 | 22.7±3.3 | 0.83 |

| Han ethnicity | 128 (94.1%) | 75 (91.5%) | 39 (97.5%) | 0.21 |

| HBsAg+ | 10 (7.4%) | 9 (11.0%) | 1 (2.5%) | 0.11 |

| Hepatitis C antibody+ | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (1.2%) | 0 | 1.00 |

| Route of HIV transmission | 0.01 | |||

| Homosexual | 102 (75.0%) | 70 (85.4%) | 26 (65.0%) | |

| Heterosexual | 15 (11.0%) | 7 (8.5%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Blood-borne | 4 (2.9%) | 1 (1.2%) | 1 (2.5%) | |

| Unknown | 15 (11.0%) | 4 (4.9%) | 10 (25%) | |

| Years since HIV diagnosis (years) | 0.8±1.9 | 0.7±1.7 | 0.4±1.6 | 0.44 |

| CD4+ cell count (cells/mm3) | 256±186 | 299±178 | 193±198 | 0.01 |

| Viral load (log10 copies/ml) | 4.7±0.7 | 4.7±0.7 | 4.8±0.7 | 0.13 |

| Spine BMD (g/cm2) | 1.19±0.14 | 1.21±0.15 | 1.16±0.13 | 0.11 |

| Spine Z-score | 0.32±1.14 | 0.41±1.20 | 0.16±1.09 | 0.29 |

| Total hip BMD (g/cm2) | 1.04±0.15 | 1.06±0.16 | 1.03±0.14 | 0.29 |

| Total hip Z-score | 0.54±1.26 | 0.73±1.25 | 0.48±0.96 | 0.28 |

| Femoral neck BMD (g/cm2) | 1.01±0.16 | 1.03±0.17 | 0.99±0.15 | 0.22 |

| Femoral neck Z-score | 0.62±1.13 | 0.65±1.38 | 0.39±1.08 | 0.31 |

The data for 14 patients are not shown, as they were on a combination of TDF-containing and non-TDF-containing regimens over the two-year follow-up period.

Results are shown as n(%) or mean ± standard deviation unless otherwise specified. Abbreviations: TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; HBsAg, hepatitis B virus surface antigen; BMD, bone mineral density.

Eighty-two patients (TDF group) were treated consistently using TDF-containing regimens, including 51 patients treated with TDF+3TC/EFV, 7 patients treated with TDF+3TC/RAL, 7 patients treated with TDF+3TC/LPV/r, 10 patients treated with TDF+3TC/LPV/r/RAL, and 7 patients who, for various clinical reasons, experienced a change in the specific composition of their TDF-containing regimen during the period between their first and last DXA scan. Forty patients (Non-TDF group) were initiated on non-TDF-containing regimens with different combinations of the agents listed above. The remaining fourteen patients had a change in their ART regimens during the first two years of therapy (with TDF use for a mean of 11.4 ± 5.8 months).

Compared with patients in the non-TDF group, patients in the TDF group had higher CD4+ T-cell counts at baseline (299 vs. 193 cells/mm3, p=0.01) (Table 1), which is consistent with the changes in Chinese national treatment guidelines in 2012 making TDF+3TC/EFV the first-line regimen of the Chinese National Free AIDS Treatment Program, and in 2015 removing the CD4+ T cell count threshold for ART initiation. More patients in the TDF group were men who have sex with men (MSM, 85.4% vs. 65.0%, p=0.01) and reported current alcohol use (29.3% vs. 7.5%, p=0.01). Other clinical parameters were similar between the two groups.

Changes in BMD over 96 weeks

Lumbar Spine

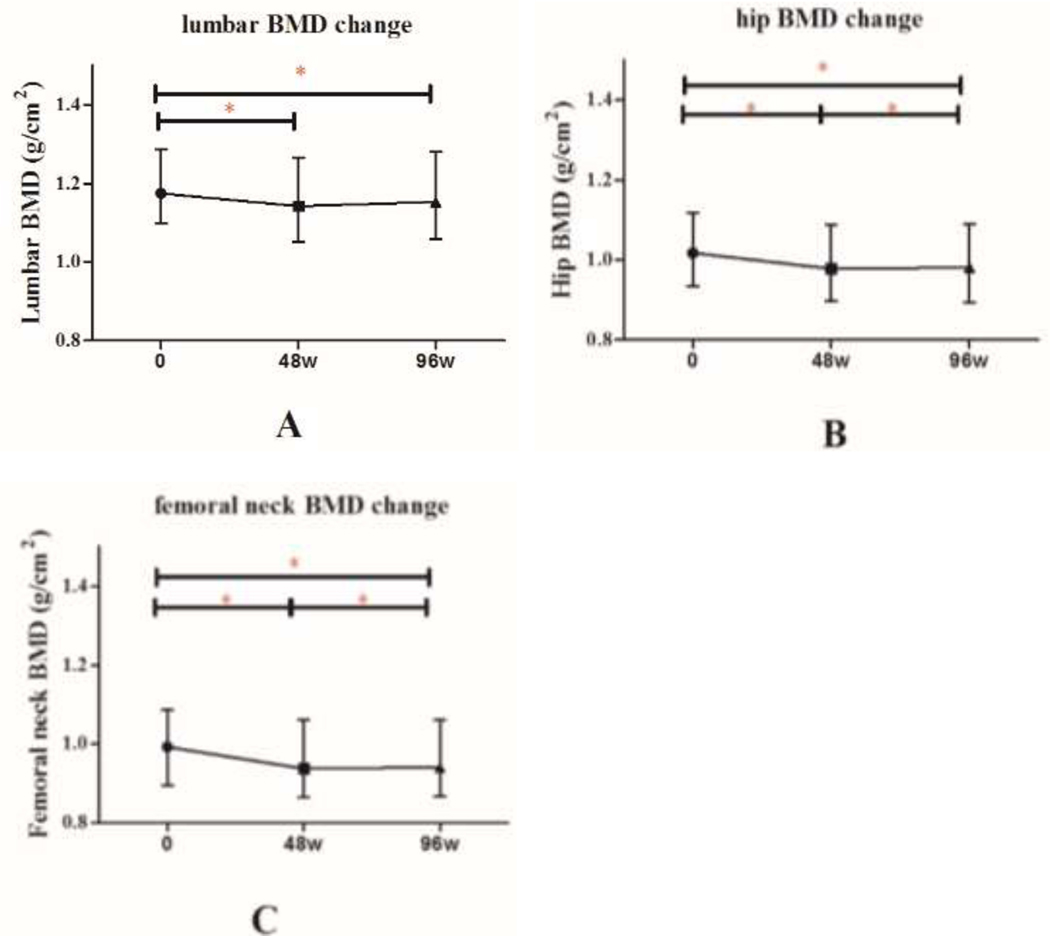

Among the 136 patients, mean absolute BMD of the lumbar spine decreased significantly from baseline to 48 weeks after initiation of ART (1.19 ±0.14 g/cm2 vs. 1.16±0.14 g/cm2, p<0.001), and remained stable from week 48 to 96 (Figure 1). Median percentage change in lumbar spine BMD was −1.93% (IQR: −5.64, 0.56) from baseline to week 48, compared with −1.97% (IQR: −5.62, 0.31) from week 48 to week 96 (p=0.63).

Figure 1. Mean absolute change in BMD over 96 weeks, by DXA site.

*denotes p<0.05.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; DXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry.

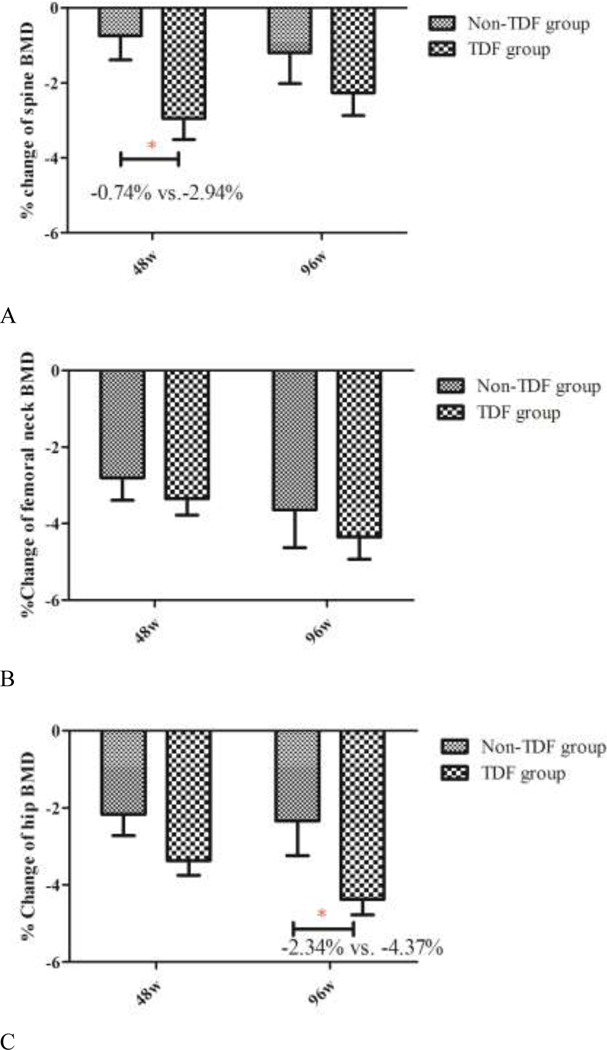

There were no significant differences in absolute lumbar spine BMD and Z-scores between the TDF and non-TDF groups at any of the three time points (Table 2). The TDF group showed greater percent change in lumbar spine BMD than the non-TDF group from baseline to week 48 (−2.94% vs. −0.74%; p=0.02) (Figure 2), but this difference was not statistically significant at the lumbar spine from baseline to week 96 (−2.26% vs.−1.20%; p=0.30) or from week 48 to week 96 (1.04% vs.−0.06%; p=0.14).

Table 2.

Absolute change in BMD over weeks, by TDF exposure group

| TDF group N=82 | Non-TDF group N=40 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| L1-L4 Spine | |||

| BMD at baseline (g/cm2) | 1.21 ± 0.15 | 1.16 ± 0.13 | 0.11 |

| BMD at week 48 (g/cm2) | 1.17 ± 0.15 | 1.16 ± 0.12 | 0.84 |

| BMD at week 96 (g/cm2) | 1.20 ± 0.17 | 1.14 ± 0.14 | 0.16 |

| Z score at baseline | 0.41 ± 1.20 | 0.16 ±1.09 | 0.29 |

| Z score at week 48 | 0.04 ± 1.18 | 0.10 ± 1.00 | 0.80 |

| Z score at week 96 | 0.20 ± 1.31 | −0.01 ±1.05 | 0.50 |

| Total Hip | |||

| BMD at baseline (g/cm2) | 1.06 ± 0.16 | 1.03 ± 0.14 | 0.29 |

| BMD at week 48 (g/cm2) | 1.01 ± 0.17 | 1.01 ± 0.13 | 0.88 |

| BMD at week 96 (g/cm2) | 1.02 ± 0.16 | 1.00 ± 0.15 | 0.61 |

| Z score at baseline | 0.73 ± 1.25 | 0.48 ± 0.96 | 0.28 |

| Z score at week 48 | 0.38 ± 1.28 | 0.40 ± 0.96 | 0.93 |

| Z score at week 96 | 0.42 ± 1.17 | 0.37 ± 0.96 | 0.86 |

| Femoral neck | |||

| BMD at baseline (g/cm2) | 1.03 ± 0.17 | 0.99 ± 0.15 | 0.22 |

| BMD at week 48 (g/cm2) | 0.99 ± 0.19 | 0.97 ± 0.14 | 0.51 |

| BMD at week 96 (g/cm2) | 1.01 ± 0.16 | 0.96 ± 0.15 | 0.23 |

| Z score at baseline | 0.65 ± 1.38 | 0.39 ± 1.08 | 0.31 |

| Z score at week 48 | 0.30 ± 1.53 | 0.25 ± 1.03 | 0.88 |

| Z score at week 96 | 0.37 ± 1.29 | 0.19 ± 1.09 | 0.54 |

Abbreviation: BMD, bone mineral density; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Figure 2. Mean percent change in BMD over 96 weeks, by site and treatment group.

*denotes p<0.05.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

In the GEE multivariable analysis (Table 3), risk factors significantly associated with the lumbar spine BMD over time included BMI [relative risk (RR) 1.02, 95% CI (1.01, 1.02), per 1 kg/m2 increase, p<0.001] and route of HIV transmission [MSM RR 1.17, 95% CI (1.07, 1.28), p=0.001; heterosexual RR 1.15, 95% CI (1.03, 1.27), p=0.009, reference = blood borne]. No significant associations were found between baseline CD4+ T-cell count, baseline HIV viral load, CD4+ T-cell count over time, HIV viral load over time and use of a TDF-containing regimen with change in lumbar spine BMD during the observation period.

Table 3.

General Estimating Equations Analysis: Association of sociodemographic and clinical risk factors associated with change in BMD (g/cm2) over 96 weeks, by BMD site.

| Variable | Lumbar Spine Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Total Hip Adjusted RR (95% CI) | Femoral Neck Adjusted RR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age ≥50 (years) | 0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 0.94 (0.85, 1.03) | 0.86 (0.79, 0.95)$ |

| Male | NA | NA | 1.05 (0.90, 1.21) |

| current smoking | 0.93 (0.87, 1.00) | 0.92 (0.85, 0.996)* | 0.91 (0.85, 0.98)* |

| current alcohol use | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 0.95 (0.88, 1.02) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): per 1-kg/m2 increase | 1.02 (1.01, 1.02)※ | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03)※ | 1.01 (1.01, 1.02)$ |

| Han Ethnicity | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | NA | NA |

| HBsAg+ | 1.05 (0.93, 1.19) | 1.11 (0.96, 1.27) | 1.09 (0.96, 1.24) |

| Route of HIV transmission | |||

| Homosexual | 1.17 (1.07, 1.28)$ | 1.11 (0.98, 1.25) | 1.04 (0.89, 1.21) |

| Heterosexual | 1.15 (1.03, 1.27)$ | 1.09 (0.95, 1.24) | 1.03 (0.90, 1.18) |

| Blood-borne | Reference | reference | reference |

| Years since HIV diagnosis (years): per 1-year increase | NA | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99)$ | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99)$ |

| Undetectable HIV viral load over time | NA | 0.96 (0.94, 0.99)$ | 0.97 (0.95, 0.998)* |

denotes p<0.001;

denotes p<0.01

denotes p<0.05; NA denotes p value >0.20 in the univariate analysis. In the univariate analysis, p value of baseline CD4+ cell count, baseline viral load, CD4+ cell count over time and TDF regimen associated with BMD change were >0.20.

Abbreviations: BMD, bone mineral density; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; NA, not available; HBsAg, hepatitis B virus surface antigen; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Total Hip

Among the 136 patients, mean absolute BMD of the total hip decreased significantly from baseline to week 96 after initiation of ART (1.04 ±0.15 g/cm2 vs. 1.00±0.15 g/cm2, p<0.01 respectively) (Figure 1). There were significant differences in the percentage change in total hip BMD [(−2.59%, IQR: −5.00, −0.82) from baseline to week 48 vs. (−3.71%, IQR: −5.43, −1.91) from baseline to week 96, p=0.003]

There were no significant differences in absolute BMD and Z-scores at the total hip between the TDF and non-TDF containing groups at the three time points (Table 2). Percent change in total hip BMD in the TDF group was similar to that observed in the non-TDF group from baseline to week 48 (−3.37% vs. −2.17%; p=0.07) (Figure 2) and from week 48 to week 96 (−1.56% vs. −0.43%; p=0.18), but the TDF group showed greater changes of total hip BMD than the non-TDF group from baseline to week 96 (−4.37% vs.−2.34%; p=0.047).

In the multivariable analysis, risk factors significantly associated with the hip BMD over time included BMI [RR 1.02, 95% CI (1.01, 1.03) per 1 kg/m2 increase, p<0.001], current smoking [RR 0.92, 95% CI (0.85, 0.996), p=0.04], undetectable VL over time [RR 0.96, 95% CI (0.94, 0.99), p=0.005], and years since HIV diagnosis [RR 0.97, 95%CI (0.95, 0.99) per 1 year increase, p=0.001] (Table 3). No significant associations were found in baseline CD4+ cell count, baseline HIV VL, CD4+ cell count over time, and TDF regimen with change in total hip BMD during the observation period.

Femoral Neck

Absolute BMD at the femoral neck decreased significantly in the 136 patients from baseline to week 96 after initiation of ART (1.01 ±0.16 g/cm2 vs. 0.97±0.16 g/cm2, p<0.01) (Figure 1). There were significant differences observed in percent change in femoral neck BMD [(−3.18%, IQR: −5.33, −0.72) from baseline to week 48 vs. (−4.32%, IQR: −6.98, −1.10) from baseline to week 96, p=0.005].

There were no significant differences in absolute BMD and Z-scores at the femoral neck between the TDF- and non-TDF groups at the three time points (Table 2). The TDF group showed similar percent change in femoral neck BMD compared with the non-TDF group from baseline to week 48 (−3.35% vs. −2.80%; p=0.45), from week 48 to week 96 (−1.58% vs.−0.64%; p=0.38) and from baseline to week 96 (−4.35% vs.−3.64%; p=0.50) (Figure 2).

In the GEE multivariable analysis (Table 3), risk factors significantly associated with change in femoral neck BMD over time included age ≥50 years [RR 0.86, 95% CI (0.79, 0.95), p=0.003], current smoking [RR 0.91, 95% CI (0.85, 0.98), p=0.01], BMI [RR 1.01, 95%CI (1.01, 1.02) per 1 kg/m2 increase, p=0.003], undetectable VL over time [RR 0.97, 95%CI (0.95, 0.998), p=0.04], and years since HIV diagnosis [RR 0.97, 95%CI (0.95, 0.99) per 1 year increase, p=0.001]. No significant associations were found in baseline CD4+ cell count, baseline HIV VL, CD4+ cell count over time, and TDF regimen with change in femoral neck BMD during the observation period.

Sub-Analysis among Patients Treated with TDF

Subgroup analysis of change in BMD among 51 patients treated with TDF+3TC/EFV (TDF+EFV group) compared with 17 patients treated with TDF+3TC/LPV/r (±RAL) (TDF+LPV/r group) showed no significant differences in absolute BMD or Z-scores of the lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck at the three time points (data not shown). The TDF+LPV/r group and TDF+EFV group showed a similar percent change in BMD at the lumbar spine and femoral neck from baseline to week 96, but the TDF+LPV/r group demonstrated greater percent change in total hip BMD from baseline to week 48 (−5.38% vs. −2.99%; p=0.02) and baseline to week 96 (−6.07% vs. −3.87%; p=0.04).

Compared with the non-TDF group, the TDF+LPV/r group showed greater percent change in total lumbar spine BMD from baseline to week 48 (−5.69% vs. −0.74%; p=0.001) and baseline to week 96 (−4.88 % vs. −1.20 %; p=0.04), and similar results were found in the percent change in hip BMD from baseline to week 48 (−5.38% vs. −2.17%; p=0.006) and baseline to week 96 (−6.07% vs. −2.34 %; p=0.04).

Prevalence and Incidence of Low BMD

At baseline, seven patients (5.1%) had low BMD (osteopenia by T- score or below the expected range for age by Z-score). Six of these individuals were over 50 years of age, and one was aged 27 years.

Among 129 patients with normal BMD for age at baseline, six patients developed incident osteopenia (all six were over 50 years of age) at the spine, hip or femoral neck during the two years following ART initiation. Of those, four patients were in the TDF group (incidence rate 33.7 (95% CI:0–66.2) per 1000 PYs), and two patients were in the non-TDF group (incidence rate 33.3 (95% CI:0–78.2) per 1000 PYs). No patients met criteria for osteoporosis at any of the time points evaluated.

Univariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that age was significantly associated with the incidence of low BMD, while TDF regimen and duration of TDF therapy were not independently associated with the incidence of low BMD. In the multivariable Cox regression model Supplementary Table 1, age ≥50 years correlated with incidence of low BMD [adjusted HR 71.75, 95% CI:8.61–598.1 p<0.001], while HIV-related factors such as route of HIV transmission, years since HIV diagnosis, baseline CD4+ T cell count and viral load and TDF exposure were not independent risk factors.

Self-Reported Fractures

Among the study population, two patients experienced a fracture during the first two years of ART. These included one 63 year-old female patient with a traumatic fracture of the right wrist and osteopenia at week 48 who was treated with TDF for nine months (later due to the renal toxicity, ART regimen switched to ABC+3TC+LPV/r); and a 50 year-old male patient with unilateral traumatic fracture of the hip and normal BMD at week 48 who was treated with 3TC+D4T (6 months later D4T was switched to AZT)+NVP.

Discussion

Our study uniquely reports changes in BMD and related risk factors among Chinese PLWH during the initial 96-weeks of treatment with TDF-containing ART. When compared with patients in the non-TDF group, those in the TDF group had greater absolute BMD loss at the lumbar spine and at the total hip from baseline to week 96, as well as greater percent change in BMD over 48 weeks at the lumbar spine and 96 weeks at the total hip. Risk factors for decline in BMD over 96 weeks included lower BMI (associated with change in BMD at all sites), current smoking (associated with lower hip and femoral neck BMD) and age over 50 years (associated with change in BMD at the total hip). With regards to HIV-specific parameters, longer duration since HIV diagnosis and undetectable VL over time were associated with lower hip and femoral neck BMD over 96 weeks. Analysis of a small subset of patients on TDF+LPV/r suggested that this combination may be associated with greater BMD loss over 96 weeks among Chinese patients with HIV.

We found a greater percentage of BMD loss at the lumbar spine from baseline through week 48 (−2.94%) and the total hip from baseline through week 96 (−4.37%) in patients treated with TDF-containing versus non-TDF-containing regimens. These findings are consistent with other reports in the literature showing percent BMD loss in the lumbar spine at week 48 ranging from −2.35% to −3.62% [18,15], and percent BMD loss in the total hip over 96 weeks from −2.4% to −4.0% [14,27] among patients receiving TDF-based regimens. In addition, the general pattern of bone loss seen among patients after ART initiation, with earlier stabilization of BMD loss at the lumbar spine compared with the total hip and femoral neck was also consistent with previous studies following patients for up to 96-weeks after initiation of ART [28].

As in previous studies, we found associations between BMD and both traditional and HIV-associated risk factors for osteoporosis. For example, in our study population, age over 50 years was independently associated with low femoral neck BMD, and an independent risk factor for incidence of low BMD. Low BMI was consistently associated with low BMD across all DXA sites. Current smoking status was associated with lower hip and femoral neck BMD over 96 weeks. Previous studies have demonstrated that increasing age was an independent risk factor for decreased BMD at both the lumbar spine [3] and femoral neck [3,29], and fracture incidence is approximately two times higher among HIV infected men above 50 years old [30]. In our study longer duration since HIV diagnosis was also independently associated with lower hip and femoral neck BMD over 96 weeks of ART, which is similar to other reports [31–33]. The bone mineral density sub-study of the INSIGHT Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Treatment (START) trial [31] found that time since HIV diagnosis was associated with lower hip BMD among ART-naïve patients. Another study from Spain found that longer time since HIV diagnosis was independently associated with risk for vertebral fracture [32]. Current international guidelines for screening of osteoporosis and fracture risk in HIV-infected patients recommend, for patients ages 40–50 years, using the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX), which is an online, validated tool which allows estimation of the 10-year probability of hip fracture and major osteoporotic fracture (spine, hip, humerus or forearm). For men aged ≥50 years and postmenopausal women, BMD measurement via dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is recommended, where available [34,35]. However, it is important to note that data for these international guidelines largely rely on studies from outside of Asia, and no guidelines currently exist in Asia regarding osteoporosis and fracture prevention among patients with HIV. Because DXA may not be universally available in China, and may exist in treatment availability and options, studies such as ours are critical to support the evidence-based development of region-specific recommendations.

Relevant to patients in settings where access to ART are limited to certain nationally approved regimens, we observed in our subgroup analysis that greater BMD loss at the total hip (−6.07%) occurred among patients treated with TDF+3TC/ LPV/r (±RAL). One recent multicenter study conducted among 328 patients from the United States demonstrated that patients with TDF+FTC/PIs had a greater decline in the lumbar spine (−3.8%) and total hip BMD (−3.7%) at week 96, compared with patients treated with TDF+FTC/RAL [27]. In a sub-study of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group from the United States, lumbar spine BMD loss among patients treated with TDF+FTC/atazanavir/ ritonavir at 96 weeks, was greater than that seen with TDF+FTC/EFV (−3.1% vs. −1.7%, p=0.035) [14]. A recent meta-analysis exploring the efficacy and safety of boosted versus un-boosted TDF [(compared with boosted and un-boosted TAF, the pro-drug formulation of tenofovir] suggested that patients treated with ritonavir-boosted TDF demonstrated higher risk of bone fracture and greater declines in BMD compared with un-boosted TDF [36]. Pharmacologic studies have suggested that that the AUC of tenofovir is 32% higher when combined with LPV/r [37], which can potentially exacerbate renal or bone adverse events of TDF. These findings are consistent with our prior data showing an approximately 60% increase in the bone resorption marker C-terminal cross-linking telopeptide of type-1 collagen (CTX) after two years of treatment with TDF/3TC/LPV/r [7]. Given Chinese patients may have increased plasma concentrations of tenofovir when compared with Western populations [24], this finding warrants investigation in future larger studies.

Despite the differences seen in percent change in BMD between the TDF and non-TDF groups, our GEE analysis did not find an independent association between TDF use and change in BMD over 96 weeks. Prior studies from outside of Asia have also shown conflicting results with some longitudinal studies showing a lack of association between TDF exposure and bone parameters among HIV-infected young patients who were followed up with the comparatively long duration of HIV infection [38,39]. However a Japanese observational cohort of HIV-infected adults with mean age of 40.0 years for male and 41.2 years for female patients, study showed an association between TDF exposure (> 5 years) and osteoporosis-related fracture [40]. A retrospective cohort study carried out in the United States by Bedimo et al. also found that cumulative exposure to TDF was an independent risk factor for osteoporotic fracture [5]. Our study was limited to 96 weeks of follow up, therefore additional studies are warranted to examine the effects of longer-term TDF exposure on bone health in this population.

Although CD4+ T cell counts were not observed to correlate with bone loss in our study, former studies from the United States have reported that lower CD4+ T cell counts at baseline and magnitude of CD4+ T cell recovery, correlates with bone loss [11–13]. The finding that TDF and non-TDF groups were both lymphopenic (CD4+ T cell count <300 cells/mm3) may in part explain the apparent lack of correlation between CD4+ cell count and bone loss. Differences in ethnicity of the study populations may also explain this discrepancy. This requires further elucidation in future studies.

Finally, although we did not systematically assess for fracture as part of this study, we encountered two patients who had self-reported fractures, both of whom were over 50 years of age, and one of whom had a normal BMD at the time of fracture. This underscores the fact while BMD remains one of the most useful and widespread tools available for identifying patients with osteoporosis, it is not a perfect predictor of fractures. A recent study from Spain reported asymptomatic vertebral fracture in 20% HIV-infected patients over 50 years, without evidence for osteoporosis based upon DXA, or high 10-year risk for fracture based upon FRAX[32]. The authors raised the consideration of performing routine lumbar spine x-rays in this vulnerable population, however more studies are needed. Our study suggests that for Chinese PLWH, more attention should be given to bone adverse events in those 50 years or older, and avoidance of drugs such as TDF (particularly when combined with LPV/r) may be warranted for these individuals. No studies to date have systematically examined fracture rates among Chinese PLWH.

A number of international studies have evaluated different aspects of the continuum with regards to fracture prevention, including adaptation or implementation of fracture risk assessment tools[41], DXA or other modes of bone density screening[6], calcium and vitamin D supplementation[34], and bisphosphonate therapy either as treatment of osteoporosis [42] or as prophylaxis [43,44]. More research is needed to understand the efficacy, effectiveness and feasibility of these interventions in the context of China, where HIV care is often provided in infectious diseases hospitals or CDC health centers and access to DXA or osteoporosis specialists may be limited. Such studies will help inform the development of country-specific guidelines for this important problem.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a single center retrospective study and therefore the study findings are not necessarily generalizable to all Chinese patients with HIV. However, the results reflect longitudinal BMD data from Asia, a region in which there is comparatively scarce literature on this topic. Second, we did not measure levels of bone turnover markers or other markers relevant to bone metabolism (e.g. parathyroid hormone, 25-OH vitamin D) which would have provided an additional valuable dimension to our findings. Third, the number of patients over 50 years of age in our sample was limited, so our results should be interpreted with caution, and future studies should include more older patients. Finally, this was a retrospective chart review, we were not able to systematically collect data regarding calcium and vitamin D supplement use in our study, so were not able to analyze this as a covariate. We suspect that the proportion of patients using calcium and vitamin D are generally low given the lack of national guidelines recommending supplementation for PLWH[45], and if anything, we would expect that use of calcium and vitamin D in our sample would underestimate the magnitude of our findings.

In conclusion, in this retrospective study of patients with HIV, greater BMD loss was found in Chinese PLWH treated with TDF-containing regimens. This may be especially the case among those treated with TDF+LPV/r, but this requires confirmation in larger studies. Furthermore, we found that risk is increased among those aged 50 and above, as well as those with low BMI or longer disease duration. As in many resource-limited regions of the world, formal guidelines for bone health in HIV that take into account limitations in ART options and lack of access to DXA, do not exist in Asia. This is important to consider in China, where almost 16.5% of new cases in 2018 occurred among patients ≥60 years of age, however training and capacity for diagnosis and management of chronic co-morbidities associated with HIV is severely lacking. Therefore, our findings provide important knowledge regarding the risk factors to consider in the long-term clinical management of patients with HIV from this region, and highlight the importance of future prospective multi-center studies to better measure the relative contributions of traditional and HIV-associated risk factors for Asian patients with HIV.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for their participation and support during this study. This study was funded by the National Key Technologies Research & Development Program for the 13th Five-year Plan (2017ZX10202101) and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CAMS-12M) (2017-12M-1-014). Dr. Hsieh is supported by NIH/Fogarty International Center K01TW009995. and the Rheumatology Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was reviewed and exempt by the institutional review board of the Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China.

Consent to participate

All study participants provided written informed consent at the time of enrollment, and all procedures were performed in compliance with the ethical standards of The Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to publication

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

Fuping Guo, Xiaojing Song, Yanling Li, Wenmin Guan, Wei Pan, Wei Yu, Taisheng Li and Evelyn Hsieh declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Reference

- 1.Smit M, Brinkman K, Geerlings S, Smit C, Thyagarajan K, Sighem A, de Wolf F, Hallett TB, cohort Ao (2015) Future challenges for clinical care of an ageing population infected with HIV: a modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis 15 (7):810–818. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00056-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran CA, Weitzmann MN, Ofotokun I (2017) Bone Loss in HIV Infection. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis 9 (1):52–67. doi: 10.1007/s40506-017-0109-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cervero M, Torres R, Agud JL, Alcazar V, Jusdado JJ, Garcia-Lacalle C, Moreno S (2018) Prevalence of and risk factors for low bone mineral density in Spanish treated HIV-infected patients. PLoS One 13 (4):e0196201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerri-Fernandez R, Molina-Morant D, Villar-Garcia J, Herrera S, Gonzalez-Mena A, Guelar A, Trenchs-Rodriguez M, Diez-Perez A, Knobel H (2017) Bone Density, Microarchitecture, and Tissue Quality After Long-Term Treatment With Tenofovir/Emtricitabine or Abacavir/Lamivudine. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 75 (3):322–327. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedimo R, Maalouf NM, Zhang S, Drechsler H, Tebas P (2012) Osteoporotic fracture risk associated with cumulative exposure to tenofovir and other antiretroviral agents. AIDS 26 (7):825–831. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835192ae [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casado JL, Santiuste C, Vazquez M, Banon S, Rosillo M, Gomez A, Perez-Elias MJ, Caballero C, Rey JM, Moreno S (2016) Bone mineral density decline according to renal tubular dysfunction and phosphaturia in tenofovir-exposed HIV-infected patients. AIDS 30 (9):1423–1431. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsieh E, Fraenkel L, Xia W, Hu YY, Han Y, Insogna K, Yin MT, Xie J, Zhu T, Li T (2015) Increased bone resorption during tenofovir plus lopinavir/ritonavir therapy in Chinese individuals with HIV. Osteoporos Int 26 (3):1035–1044. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2874-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh E, Fraenkel L, Han Y, Xia W, Insogna KL, Yin MT, Zhu T, Cheng X, Li T (2016) Longitudinal increase in vitamin D binding protein levels after initiation of tenofovir/lamivudine/efavirenz among individuals with HIV. AIDS 30 (12):1935–1942. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbieri AM, Chiodini I, Ragni E, Colaianni G, Gadda F, Locatelli M, Lampertico P, Spada A, Eller-Vainicher C (2018) Suppressive effects of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, an antiretroviral prodrug, on mineralization and type II and type III sodium-dependent phosphate transporters expression in primary human osteoblasts. J Cell Biochem 119 (6):4855–4866. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deeks SG (2009) Immune dysfunction, inflammation, and accelerated aging in patients on antiretroviral therapy. Top HIV Med 17 (4):118–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ofotokun I, Titanji K, Vunnava A, Roser-Page S, Vikulina T, Villinger F, Rogers K, Sheth AN, Lahiri CD, Lennox JL, Weitzmann MN (2016) Antiretroviral therapy induces a rapid increase in bone resorption that is positively associated with the magnitude of immune reconstitution in HIV infection. AIDS 30 (3):405–414. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ofotokun I, Titanji K, Vikulina T, Roser-Page S, Yamaguchi M, Zayzafoon M, Williams IR, Weitzmann MN (2015) Role of T-cell reconstitution in HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy-induced bone loss. Nat Commun 6:8282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grant PM, Kitch D, McComsey GA, Dube MP, Haubrich R, Huang J, Riddler S, Tebas P, Zolopa AR, Collier AC, Brown TT (2013) Low baseline CD4+ count is associated with greater bone mineral density loss after antiretroviral therapy initiation. Clin Infect Dis 57 (10):1483–1488. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McComsey GA, Kitch D, Daar ES, Tierney C, Jahed NC, Tebas P, Myers L, Melbourne K, Ha B, Sax PE (2011) Bone mineral density and fractures in antiretroviral-naive persons randomized to receive abacavir-lamivudine or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-emtricitabine along with efavirenz or atazanavir-ritonavir: Aids Clinical Trials Group A5224s, a substudy of ACTG A5202. J Infect Dis 203 (12):1791–1801. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mills A, Crofoot G Jr., McDonald C, Shalit P, Flamm JA, Gathe J Jr., Scribner A, Shamblaw D, Saag M, Cao H, Martin H, Das M, Thomas A, Liu HC, Yan M, Callebaut C, Custodio J, Cheng A, McCallister S (2015) Tenofovir Alafenamide Versus Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate in the First Protease Inhibitor-Based Single-Tablet Regimen for Initial HIV-1 Therapy: A Randomized Phase 2 Study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 69 (4):439–445. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sax PE, Zolopa A, Brar I, Elion R, Ortiz R, Post F, Wang H, Callebaut C, Martin H, Fordyce MW, McCallister S (2014) Tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in single tablet regimens for initial HIV-1 therapy: a randomized phase 2 study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 67 (1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeJesus E, Haas B, Segal-Maurer S, Ramgopal MN, Mills A, Margot N, Liu YP, Makadzange T, McCallister S (2018) Superior Efficacy and Improved Renal and Bone Safety After Switching from a Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate- to a Tenofovir Alafenamide-Based Regimen Through 96 Weeks of Treatment. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 34 (4):337–342. doi: 10.1089/AID.2017.0203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taiwo BO, Chan ES, Fichtenbaum CJ, Ribaudo H, Tsibris A, Klingman KL, Eron JJ, Berzins B, Robertson K, Landay A, Ofotokun I, Brown T, Team ACTGAS (2015) Less Bone Loss With Maraviroc- Versus Tenofovir-Containing Antiretroviral Therapy in the AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5303 Study. Clin Infect Dis 61 (7):1179–1188. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Regular press conference: Progress in the prevention and treatment of AIDS in China. http://ncaidschinacdccn/xxgx/yqxx/201811/t20181123_197488htm.

- 20.Zhao DC, Wen Y, Ma Y, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Wu YS, Liu X, Au E, Liu ZF, Zhang FJ (2012) Expansion of China’s free antiretroviral treatment program. Chin Med J (Engl) 125 (19):3514–3521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Su Y, Hsieh E, Xia W, Xie J, Han Y, Cao Y, Li Y, Song X, Zhu T, Li T, Yu W (2013) Bone turnover and bone mineral density in HIV-1 infected Chinese taking highly active antiretroviral therapy -a prospective observational study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiser JJ, Fletcher CV, Flynn PM, Cunningham CK, Wilson CM, Kapogiannis BG, Major-Wilson H, Viani RM, Liu NX, Muenz LR, Harris DR, Havens PL, Adolescent Trials Network for HIVAI (2008) Pharmacokinetics of antiretroviral regimens containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and atazanavir-ritonavir in adolescents and young adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52 (2):631–637. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00761-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lamorde M, Byakika-Kibwika P, Tamale WS, Kiweewa F, Ryan M, Amara A, Tjia J, Back D, Khoo S, Boffito M, Kityo C, Merry C (2012) Effect of Food on the Steady-State Pharmacokinetics of Tenofovir and Emtricitabine plus Efavirenz in Ugandan Adults. AIDS Res Treat 2012:105980. doi: 10.1155/2012/105980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du X, Kou H, Fu Q, Li Y, Zhu Z, Li T (2017) Steady-state pharmacokinetics of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in human immunodeficiency virus-infected Chinese patients. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 10 (7):783–788. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2017.1321480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao W, Hsieh E, Li T (2020) Optimizing Treatment for Adults with HIV/AIDS in China: Successes over Two Decades and Remaining Challenges. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 17 (1):26–34. doi: 10.1007/s11904-019-00478-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R, National Osteoporosis F (2014) Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25 (10):2359–2381. doi: 10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown TT, Moser C, Currier JS, Ribaudo HJ, Rothenberg J, Kelesidis T, Yang O, Dube MP, Murphy RL, Stein JH, McComsey GA (2015) Changes in Bone Mineral Density After Initiation of Antiretroviral Treatment With Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine Plus Atazanavir/Ritonavir, Darunavir/Ritonavir, or Raltegravir. J Infect Dis 212 (8):1241–1249. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoy JF, Grund B, Roediger M, Schwartz AV, Shepherd J, Avihingsanon A, Badal-Faesen S, de Wit S, Jacoby S, La Rosa A, Pujari S, Schechter M, White D, Engen NW, Ensrud K, Aagaard PD, Carr A, Group ISBMDS (2017) Immediate Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection Accelerates Bone Loss Relative to Deferring Therapy: Findings from the START Bone Mineral Density Substudy, a Randomized Trial. J Bone Miner Res. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinago W, Cotter AG, Sabin CA, Macken A, Kavanagh E, Brady JJ, McCarthy G, Compston J, Mallon PW, Group HUS (2017) Predictors of longitudinal change in bone mineral density in a cohort of HIV-positive and negative patients. AIDS 31 (5):643–652. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonciulea A, Wang R, Althoff KN, Palella FJ, Lake J, Kingsley LA, Brown TT (2017) An increased rate of fracture occurs a decade earlier in HIV+ compared with HIV- men. AIDS 31 (10):1435–1443. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr A, Grund B, Neuhaus J, Schwartz A, Bernardino JI, White D, Badel-Faesen S, Avihingsanon A, Ensrud K, Hoy J, International Network for Strategic Initiatives in Global HIVTSSG (2015) Prevalence of and risk factors for low bone mineral density in untreated HIV infection: a substudy of the INSIGHT Strategic Timing of AntiRetroviral Treatment (START) trial. HIV Med 16 Suppl 1:137–146. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Llop M, Sifuentes WA, Banon S, Macia-Villa C, Perez-Elias MJ, Rosillo M, Moreno S, Vazquez M, Casado JL (2018) Increased prevalence of asymptomatic vertebral fractures in HIV-infected patients over 50 years of age. Arch Osteoporos 13 (1):56. doi: 10.1007/s11657-018-0464-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cotter AG, Sabin CA, Simelane S, Macken A, Kavanagh E, Brady JJ, McCarthy G, Compston J, Mallon PW, Group HUS (2014) Relative contribution of HIV infection, demographics and body mass index to bone mineral density. AIDS 28 (14):2051–2060. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown TT, Hoy J, Borderi M, Guaraldi G, Renjifo B, Vescini F, Yin MT, Powderly WG (2015) Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis 60 (8):1242–1251. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biver E, Calmy A, Aubry-Rozier B, Birkhauser M, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Ferrari S, Frey D, Kressig RW, Lamy O, Lippuner K, Suhm N, Meier C (2019) Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of bone fragility in people living with HIV: a position statement from the Swiss Association against Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 30 (5):1125–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4794-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hill A, Hughes SL, Gotham D, Pozniak AL (2018) Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: is there a true difference in efficacy and safety? J Virus Erad 4 (2):72–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vitoria M, Hill AM, Ford NP, Doherty M, Khoo SH, Pozniak AL (2016) Choice of antiretroviral drugs for continued treatment scale-up in a public health approach: what more do we need to know? J Int AIDS Soc 19 (1):20504. doi: 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Unsal AB, Mattingly AS, Jones SE, Purdy JB, Reynolds JC, Kopp JB, Hazra R, Hadigan CM (2017) Effect of Antiretroviral Therapy on Bone and Renal Health in Young Adults Infected With HIV in Early Life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102 (8):2896–2904. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giacomet V, Maruca K, Ambrosi A, Zuccotti GV, Mora S (2017) A 10-year follow-up of bone mineral density in HIV-infected youths receiving tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Int J Antimicrob Agents 50 (3):365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.03.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Komatsu A, Ikeda A, Kikuchi A, Minami C, Tan M, Matsushita S (2018) Osteoporosis-Related Fractures in HIV-Infected Patients Receiving Long-Term Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate: An Observational Cohort Study. Drug Saf. doi: 10.1007/s40264-018-0665-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Sharma A, Shi Q, Anastos K, Cohen MH, Golub ET, Gustafson D, Merenstein D, Mack WJ, Tien PC, Nieves JW, Yin MT (2018) Improved fracture prediction using different fracture risk assessment tool adjustments in HIV-infected women. AIDS 32 (12):1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoy JF, Richardson R, Ebeling PR, Rojas J, Pocock N, Kerr SJ, Martinez E, Carr A, Investigators ZS (2018) Zoledronic acid is superior to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate-switching for low bone mineral density in adults with HIV. AIDS 32 (14):1967–1975. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ofotokun I, Titanji K, Lahiri CD, Vunnava A, Foster A, Sanford SE, Sheth AN, Lennox JL, Knezevic A, Ward L, Easley KA, Powers P, Weitzmann MN (2016) A Single-dose Zoledronic Acid Infusion Prevents Antiretroviral Therapy-induced Bone Loss in Treatment-naive HIV-infected Patients: A Phase IIb Trial. Clin Infect Dis 63 (5):663–671. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ofotokun I, Collins LF, Titanji K, Foster A, Moran CA, Sheth AN, Lahiri CD, Lennox JL, Ward L, Easley KA, Weitzmann MN (2019) Antiretroviral Therapy-induced Bone Loss is Durably Suppressed by a Single Dose of Zoledronic Acid in Treatment-naive Persons with HIV Infection: a Phase IIB Trial. Clin Infect Dis. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hsieh E, Fraenkel L, Bradley EH, Xia W, Insogna KL, Cui Q, Li K, Li T (2014) Osteoporosis knowledge, self-efficacy, and health beliefs among Chinese individuals with HIV. Arch Osteoporos 9:201. doi: 10.1007/s11657-014-0201-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.