Abstract

Abstract

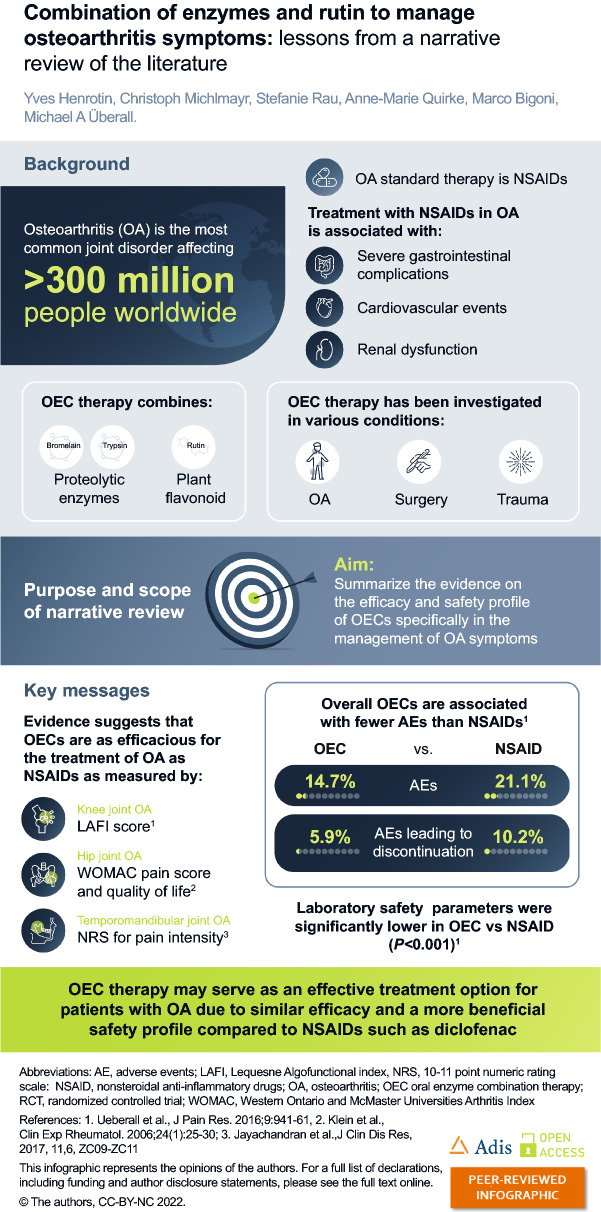

Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disorder affecting over 300 million people worldwide. It typically affects the knees and the hips, and is characterized by a loss in normal joint movement, stiffness, swelling, and pain in patients. The current gold standard therapy for osteoarthritis targets pain management using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are associated with several potentially serious side effects, the most common being gastrointestinal perforation and bleeding. Owing to the side effects, NSAID treatment doses need to be as low as possible and should be continued for the shortest duration possible, which is problematic in a chronic condition like osteoarthritis, which requires long-term management. Numerous clinical trials have examined oral enzyme combinations as a potential new approach in managing pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Oral enzyme combinations containing bromelain in combination with trypsin, both proteolytic enzymes, as well as the plant flavonoid rutin, may be an effective alternative to typical NSAIDs. The aim of this narrative review is to summarize and discuss the evidence on the efficacy of oral enzyme combinations compared to the gold standard (NSAID) in the management of osteoarthritis symptoms. Nine randomized controlled trials identified in this review assessed the efficacy and safety of the oral enzyme combination containing bromelain, trypsin, and rutin in patients with osteoarthritis. Most of the studies assessed the impact of the oral enzyme combination on the improvement of the Lequesne Algofunctional index score, treatment-related pain intensity alterations and adverse events compared to patients receiving NSAIDs. Although largely small scale, the study outcomes suggest that this combination is as effective as NSAIDs in the management of osteoarthritis, without the adverse events associated with NSAID use.

Infographic

Keywords: Alpha-2-macroglobulin, Bromelain, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Oral enzyme combination, Osteoarthritis, Rutin, Trypsin

Key summary points

| Oral enzyme combination (OEC) therapy is being studied to treat a variety of conditions, including inflammation, oncology, and trauma. |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most prescribed pharmaceutical treatment for the most common joint disorder worldwide – osteoarthritis (OA). |

| The long-term use of NSAIDs in osteoarthritis is associated with several potentially serious side effects. |

| Study outcomes following use of an OEC therapy combination containing the proteolytic enzymes bromelain and trypsin in addition to the plant flavonoid rutin in patients with OA suggest that this OEC is as effective as NSAIDs but with a superior side effect profile. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including an infographic, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.20058908.

Introduction

Inflammation is the body’s natural immune response to a variety of harmful stimuli, including tissue injury and progressive diseases. Even if chronic and acute forms of inflammation are clinically burdensome for patients owing to the pain, swelling, and functional limitations, inflammation is also an important step that contributes to the healing process. Without the inflammation step, the healing process may be incomplete [1]. During inflammation, cytokines are released in the affected area, with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines playing a central role in balancing the inflammatory responses [2]. Acute inflammatory conditions can result from sports injuries or following surgery [3–6]. In some instances, inflammation may become unregulated and develop into a chronic condition such as osteoarthritis (OA).

Inflammatory conditions such as OA are commonly managed using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [7–9]. However, long-term use of NSAIDs is associated with several adverse events [10] and a link between NSAID use and progression of radiographic knee OA has recently been suggested [11], limiting treatment options even further. NSAIDs may further disrupt the resolution (e.g., active healing) process of inflammation by, for example, blockade of cyclooxygenase (COX-2), which prevents the release of specialized pro-resolving mediators [12]. Complementary therapy including systemic enzyme therapy or oral enzyme combination (OEC) is a potential new approach in managing inflammatory conditions. The scientific evidence underlining the efficacy of OECs in the treatment of patients with OA includes nine small-scale clinical trials (with up to 268 subjects) and a systematic literature review with a pooled individual patient-level meta-analysis of data from six randomized controlled trials (RCT), comparing OEC to the NSAID diclofenac in patients with OA of the knee [13].

In this narrative review, we will summarize the evidence of the efficacy of existing enzyme therapy treatments and specifically focus on efficacy in OA. This paper includes a search in PubMed using the following terms ‘osteoarthritis’, ‘systemic enzyme therapy’, ‘oral enzyme combination’, and ‘proteolytic enzymes’ with relevant literature selected for review. Animal or in vitro studies were included to enhance the understanding of the mode of action of oral proteolytic enzyme combinations and the flavonoid rutin (or rutoside). This paper is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Enzyme Therapy History

The administration of plant extracts with high proteolytic enzyme content (systemic enzyme therapy) originates from the use of traditional medicine in Central and South America [14]. It is currently being studied to treat a variety of conditions, including those associated to oncology, trauma, and inflammation [13–16]. In 1902, John Beard published a scientific article in The Lancet proposing enzymatic treatment of patients with cancer. He then published the scientific rationale of systemic enzyme therapy in 1911, ‘The Enzyme Treatment of Cancer and its Scientific Basis’ [17]. However, his work had been largely forgotten until the 1950s when Max Wolf and Helene Benitez developed the concept of systemic enzyme therapy for oncology [14]. They observed that systemic enzyme therapy, including a combination of plant and animal proteinases, exerted anti-cancer effects by restoring the reduced cytotoxic activity of patients’ sera [18].

The systematic enzyme therapy combination most frequently used in oncology has consisted of a combination of papain, trypsin, and chymotrypsin [14]. A review of a number of RCTs in Germany using systematic enzyme therapy as an adjunctive treatment with radiotherapy and chemotherapy highlighted how systematic enzyme therapy can reduce the severity adverse effects caused by radiotherapy and chemotherapy [14].

OEC therapy was also investigated in low-grade inflammation and in the treatment of delayed-onset muscle soreness [19, 20]. An open trial conducted by Kameníček et al. [16] demonstrated the superiority of an OEC containing bromelain and trypsin combined with rutin as active ingredients, over escin-based anti-edematous drugs, in the prophylaxis of post-surgical edema following osteosynthesis of the long bones of the extremities. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial investigating the same OEC reported significant favorable effects on fatigue, muscle soreness, and damage, as well as on immunological and metabolic biomarkers in healthy active adults after exhaustive eccentric exercise [19].

OA

OA is a chronic inflammatory disease that is often referred to as a degenerative joint disease. In addition to wear and tear, OA is also characterized by abnormal remodeling of the joint, bone, cartilage, ligaments, fat, and the synovium, caused by a number of inflammatory mediators within the affected joint [21]. The main hallmarks of OA recognized by the patient include a loss of normal joint movement, stiffness, swelling, and pain [22]. Clinical OA is defined by features in the patient’s clinical history and on medical examination, with the classification of idiopathic OA of the knee including joint pain in addition to at least three of the following criteria: age over 50 years, stiffness for more than 30 min, crepitus, bony tenderness, bony enlargement, or no palpable warmth [23, 24]. Subjective OA relies on the assessment of the patient as to whether the disease is present, with a poor correlation to radiographic structural changes [23].

The prevalence of OA is rising owing to the increase in risk factors, particularly ageing, and a rise in obesity due to a sedentary lifestyle [25]. The global number of people aged 65 years or older is projected to more than double, reaching over 1.5 billion persons by 2050 [26], consequently leading to an expected increase in OA cases. Knee OA accounts for 83% of the total OA burden and is the most common OA localization in persons aged 40 years and over; symptomatic knee OA is highly prevalent among people aged over 50 years, affecting more than 250 million people worldwide [27, 28].

Chronic inflammation is linked to the onset and development of OA and can be caused by long-term tissue exposure to stressors [29, 30]. There are two types of stressors involved in joint tissue damage that links obesity and OA—the direct effect of mechanical load, and the effect of adipocytes inducing micro-inflammatory processes when the adipose tissue is ectopic [31]. Some of the hallmarks of ageing such as age-related inflammation (also known as inflammaging) and cellular senescence (including the senescence-associated secretory phenotype [SASP]) could also contribute to the development of OA [32–34]. The production of pro-inflammatory cytokines is one of the key features of SASP [34–36]. The potency of senescent cells in shortening health- and lifespan was indicated in an animal study in which transplantation of senescent cells into older mice resulted in persistent physical dysfunction, as well as spreading cellular senescence to host tissue and reducing survival [37].

As OA is a progressive disease that spans decades of a patient’s life, with varying degrees of severity, the long-term management of OA usually includes several pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions. Currently available treatments aim to reduce symptoms of inflammation (particularly pain), maintain joint mobility, and limit the loss of function [22, 38]. The reduction of pain and inflammation in patients with OA can increase compliance and participation in exercise programs, further contributing to improved quality of life [39].

Symptoms of OA are commonly managed using NSAIDs [7–9]. Existing treatment guidelines from prominent professional societies for patients with OA recommend oral NSAIDs but limit their use for patients with certain risk factors [22, 40–43]. The risk factors for the most important toxicity of NSAIDs—gastrointestinal bleeding, include older age, medical comorbidities and concomitant use of corticosteroids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and anticoagulants [41, 44]. In addition, individuals with cardiovascular comorbidities are at risk for myocardial infarction, hypertension and heart insufficiency, while those with a renal condition are at risk of renal toxicity [40, 41].

Long-term use of NSAIDs is associated with several adverse effects, including alterations in renal function, effects on blood pressure, hepatic injury, and platelet inhibition, which may result in increased bleeding [10]. Although doses are recommended to be as low as possible, and NSAID treatment is continued for as short a time as possible [22], these treatment schedules do not serve as a valid option for long-term inflammation management as needed in OA. The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) guidelines suggest limiting non-selective NSAID use to a maximum of 7 days in patients with cardiovascular risk factors, with the Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) guidelines recommending against the use of any NSAID in these patients [45]. Guidelines advise prescribing proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) to alleviate gastrointestinal side effects, but not other intestinal-related risks [41, 46]; however, longer-term intake of PPIs is also associated with adverse effects, e.g., small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and potentially increased risk for gastrointestinal malignancies [47]. The American Geriatrics Society recommends avoiding chronic use in patients over 65 years old, the typical age group for clinically relevant OA [48]. Selective COX-2 inhibitors should be limited to less than 30 days of use and the risk of hospitalization due to heart failure is reportedly doubled by all NSAID regimens including COX-2 inhibitors, according to the ESCEO [46]. The OARSI strongly advises against using COX-2 inhibitors in individuals with cardiovascular comorbidities [41]. Opioids as a final pharmacological treatment before surgery are either weakly or not at all recommended, owing to their unfavorable efficacy and/or safety profile [45] and were found to increase the risk of all-cause mortality [49].

As there is currently no cure for OA, affected patients face symptomatic and even worsening flares in the long term, and the most widespread therapy options have multiple limitations, particularly concerning adverse treatment effects. Coexistence of comorbidities is also frequent among patients with OA; up to 85% of patients present with one or more comorbidities, the most common ones being cardiovascular/blood diseases [50], emphasizing the need for an effective and well-tolerated anti-inflammatory treatment alternative to prevent OA progression and improve OA symptoms.

Treatments harboring complementary properties, including anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects that can improve mobility in patients with OA, such as OECs, have been proposed as valuable alternative options for patients with acute or chronic inflammation, with relatively mild adverse event profiles [13]. One well-researched OEC comprising a protease–flavonoid combination contains the proteolytic enzymes bromelain – a plant cysteine protease enzyme, and trypsin – an animal serine protease, combined with the plant flavonoid rutin (rutin trihydrate, or rutoside). This OEC has been proposed to reduce inflammation by helping to control the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines as outlined in the following sections, consequently improving symptoms associated with common inflammatory conditions.

Oral Proteolytic Enzyme Combination with Trypsin and Bromelain

Proteolytic enzymes do not suppress the inflammatory response but support and accelerate the controlled physiological progression of the immune response and inflammatory processes. In addition, they have a more favorable side-effect profile than NSAIDs [13]. Several potentially beneficial mechanisms underlying the effect of proteolytic enzymes in OECs have been proposed in animal models and in vitro (Table 1).

Table 1.

Potential modes of action underlying the effect of proteolytic enzymes following oral application in animal models and in vitro

| Protease effects after oral application | Mechanisms of the effects |

|---|---|

| In vitro | |

| Effect on cytokines operating locally and systemically | Systemic proteolytic enzymes can help to accelerate the clearance of specific cytokines. When a cytokine is bound to alpha-2-macroglobulin (an anti-protease) linked to a protease, a stable bond is formed, which inactivates the cytokine. Consequently, the whole complex (protease–anti-protease–cytokine) is quickly eliminated by phagocytosis [15, 51, 52] |

| Effect on direct proteolytic activity | Proteolytic enzymes may take part in specific activation, regulation and degradation of a whole range of factors associated with an inflammatory response. Removal of surface receptors such as CD44, CD45RA and CD6 by bromelain is associated with enhanced T cell–monocyte aggregation and enhanced CD2-mediated T-cell activation [54] |

| Effect on activation of macrophages/monocytes | Bromelain activates murine macrophages and natural killer cells in the presence of IFN gamma in vitro, indicating a potential role in the priming of innate immune responses against infectious agents [105] |

| Effect on decreasing neutrophil migration | Bromelain was shown to decrease neutrophil migration in vitro to sites of inflammation, demonstrating a potential to decrease acute responses to inflammatory stimuli [106] |

| Effect on decreasing secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines | Bromelain decreases secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in inflamed colon tissue in vitro [53] |

| Effect on AGEs by exogenous proteolytic enzymes | In vitro experiments demonstrated that the proteolytic enzyme trypsin can reduce the concentration of AGEs, which are linked to increased formation of oxygen radicals and synthesis of cytokines, growth factors, and adhesion molecules [55] |

| Animal models | |

| Effect on fibrinolytic activities in dissolving fibrin clots and reducing platelet aggregation | Bromelain has been shown to exhibit fibrinolytic activities in dissolving fibrin clots in rats and reduces platelet aggregation, which can lead to a significant reduction in pain and edema [107] |

| Antioxidant effects, improved microcirculation | Proteolytic enzyme formulations containing rutin, trypsin, and bromelain demonstrate antioxidant effects in rabbit skeletal muscle, which may be attributed to the bioflavonoid rutin and protease-mediated improved microcirculation [108] |

| Both in vitro and animal models | |

| Effect by means of PARs | Through the protease–PAR interaction, proteolytic enzymes such as trypsin may act as key modulators of immune and inflammatory responses. Potential PAR activation may help maintain normal inflammatory processes and blood flow [109, 110] |

AGE advanced glycation end product, CD cluster of differentiation, IFN interferon, PAR protease-activated receptor

In vitro experiments have shown how OEC binding and activation of alpha-2-macroglobulin (alpha-2 M) cause the irreversible binding of excess cytokines, which are central to the inflammatory response in OA [15, 51, 52]. Secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines decreased in the presence of bromelain [53]. Cell surface receptors such as CD44 associated with the inflammatory response in OA were shown to be removed by bromelain [54]. In addition, trypsin can reduce the concentration of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) [55], which have been found to accumulate in aged joints and are associated with OA [56] (Table 1).

High platelet count is associated with OA [57]. Animal models investigating inflammation have shown that bromelain can dissolve fibrin clots and reduce platelet aggregation [103]. In addition, animal models have demonstrated that enzyme formulations containing rutin, trypsin, and bromelain have antioxidant effects [104] (Table 1).

Pharmacodynamics of Orally Administered Enzymes

Alpha-2 M Activation by Proteases

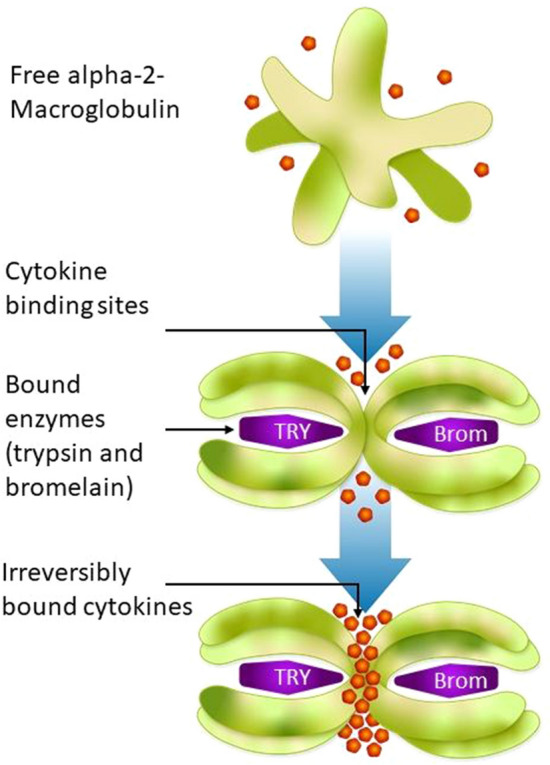

Alpha-2 M is a plasma proteinase inhibitor with inflammatory properties that regulates the distribution and activity of many cytokines [58–62]. Though the exact mechanism is not known, animal models and human studies have demonstrated that proteolytic enzymes, such as trypsin and bromelain, are absorbed as physiologically intact molecules [63–65]. In the blood, these proteases bind to alpha-2 M, inducing a structural change that activates it. Cytokine-binding sites at the shoulder region of activated alpha-2 M are then exposed, allowing the irreversible binding of excess cytokines, such as interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and IL-1 beta, restoring the balance necessary for suppressing inflammatory responses (Fig. 1) [51, 63, 66, 67]. Hypochlorite production in inflammation is considered an important switch mechanism to increase binding to pro-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors including IL-6, and decrease binding to cytokines and growth factors with anti-inflammatory in addition to pro-inflammatory roles such as transforming growth factor beta [51, 63]. When cytokines are bound to activated alpha-2 M, their activity is abolished [58]. This leads to a reduction of active cytokines in the blood. The enzyme–alpha-2 M–cytokine complexes are then degraded via macrophages and Kupffer cells. Proteolytic enzymes could therefore play a role in reducing inflammation by helping to restore the balance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Clinical evidence from a small number of healthy volunteers shows that ingestion of proteinases triggers the formation of an intermediate (enzyme-activated) form of alpha-2 M in blood plasma with preferential binding to the growth factor chosen [15]. Additionally, a significant reduction of IL-6 serum concentration was reported in a randomized, double-blind controlled trial after a 4-week intake of OEC in humans with subclinical inflammation [20]. A significant reduction of IL-1 beta and TNF-alpha was also observed in the serum of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had been treated with an OEC in an open-label trial [68]. At present, there are ongoing investigations to determine the mechanism of action of this OEC in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial in patients with OA (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05038410) [69].

Fig. 1.

Proposed mode of action of enzymes in inflammation. Brom bromelain, TRY trypsin

Bromelain

Bromelain is a cysteine protease enzyme derived from pineapples [70]. It is an anti-inflammatory enzyme that reduces pro-inflammatory prostaglandin E2 and COX-2 synthesis [71]. Bromelain is used to treat OA and many other conditions, in addition to being used as an analgesic agent to treat muscular, arthritic and perineal pain, and pain from an episiotomy [72]. The analgesic effects of bromelain are believed to be caused by its direct effect on pain mediators, such as bradykinin [73, 74]. Downregulation of inflammatory cytokines and hence chondroprotective effects have been demonstrated in vitro in a porcine cartilage explant model and synovial sarcoma cell line [75].

At present, there are no large-scale RCTs investigating the benefits of bromelain as a single agent for the treatment of OA. In a randomized, single-blind, active-controlled, small pilot study where 40 patients with mild-to-moderate OA of the knee were randomized to receive oral bromelain (500 mg/day), or the NSAID diclofenac (gold standard therapy; 100 mg/day), there were similar reductions in the total Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) pain score and ratings for quality of life, as determined from the 36-item Short Form score, in the bromelain and diclofenac groups after 4 weeks; however, with the non-inferiority margin set at − 12%, the trial was inconclusive. These results suggest that bromelain was well tolerated, although two patients given diclofenac had adverse effects leading to discontinuation [76].

A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of six RCTs in third-molar surgery compared bromelain versus placebo or no treatment, and revealed that bromelain is an effective and safe adjuvant treatment for the control of post-operative pain [77]. The anti-inflammatory and analgesic characteristics of bromelain as an alternative to NSAIDs for post-operative pain control indicate its potential in the treatment of several chronic inflammatory disorders such as OA.

Trypsin

Trypsin is a serine protease enzyme isolated from porcine pancreatic juice and binds primarily to the specific anti-protease α1-antitrypsin, potentially increasing the bioavailability of plasmin for fibrinolysis and, through raised levels of anti-proteases, facilitates faster healing in combination with chymotrypsin [78]. Trypsin is transferred from its complex with α1-antitrypsin to alpha-2 M in vivo [79]. Oral trypsin may exhibit analgesic effects in arthritis patients through vagal mediation [80] and has shown anti-phlogistic effects [81] as demonstrated in mouse models. There are no RCTs investigating trypsin as single agent to treat OA, yet anti-inflammatory and analgesic synergistic effects of trypsin have been reported when used as a component of OECs [14, 78, 82, 83].

Rutin

Rutin (other names: rutoside or rutin trihydrate), a plant flavonoid, has a number of pharmacological benefits including antioxidant effects, and has demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties in a rat model of acute and chronic inflammation [84–86]. Rutin is frequently used in combination with proteolytic enzymes in OECs to treat OA [14, 82, 83].

The plant flavonoid quercetin, a derivative of rutin, is currently under investigation as a senolytic drug. Senolytics are a class of drugs that specifically target senescent cells by inducing their apoptosis [87]. Quercetin has been reported to inhibit the development of senescent cells in pre-clinical studies and in an ongoing clinical study (in patients with chronic kidney disease) [36, 37, 88, 89]. Collectively, these studies of the senolytic properties of quercetin indicate the potential for this plant flavonoid in the treatment of OA.

Clinical Effect of an Oral Enzyme and Rutin Combination on OA

The OEC with the most available evidence for the treatment of OA comprises bromelain (450 International Pharmaceutical Federation [FIP] units; an internationally accepted unit to measure enzymatic activity), trypsin (1440 FIP units/24 µkat) and 100 mg of rutin.1 This OEC has also been investigated to treat other types of inflammation (due to acute injuries), such as surgical trauma and soft tissue sports injuries [16, 19, 90]. Clinical studies on the efficacy and safety of the OEC with these doses of bromelain, trypsin, and rutin relative to the NSAID diclofenac are included in this review (Table 2) [13, 91–96]. Though there are other OECs that contain different enzyme components, or even only a combination of trypsin and chymotrypsin, these alternative combinations will not be discussed in this review due to lack of evidence.

Table 2.

Summary of the findings of clinical trials (including a meta-analysis of six clinical trials) on the efficacy and safety of the oral enzyme combination of bromelain, trypsin, and rutin relative to the NSAID diclofenac

| References | Design | Country | Number of subjects | Duration | Clinical target | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ueberall et al. [13] | Meta-analysis of six comparator-controlled trials from 1998–2015 | Germany | 774 | 3–12 weeks | Joint health (knee) | As effective as diclofenac; significantly fewer adverse events and safety profile regarding liver and hematology significantly better than diclofenac |

| Boltena et al. 2015 [92] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparator trial | Germany | 150 | 12 weeks | Joint health (knee) | Placebo group integrated; as effective as diclofenac, with few side effects as placebo, and lower intake of rescue medication with the oral enzyme combination |

| Akhtara et al. [91] | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group (comparator) | Germany | 103 | 6 weeks | Joint health (knee) | Non-inferior efficacy in OEC compared to diclofenac demonstrated |

| Singera et al. [96] | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group (comparator) | Germany | 63 | 3 weeks, plus 4 weeks observation | Joint health (knee) | As effective as diclofenac, but longer-lasting effect even after end of treatment |

| Klein and Kullicha [94] | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group (comparator) | Germany | 73 | 3 weeks | Joint health (knee) | As effective as diclofenac |

| Herreraa [93] | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group (comparator) | Mexico | 59 | 3 weeks | Monoarticular gonarthritis (knee) | The LAFI scores and the sum score of the symptoms were equivalent in both treatment groups at the end of the study; however, the pre-calculated number of patients was too low for statistical proof of equivalence |

| Roth and Staudera [95] | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group (comparator) | 268 | 6 weeks | Joint health (knee) | ||

| Tilwe et al. [98] | Randomized, single-blind, parallel-group (comparator) | Germany | 50 | 3 weeks, plus 4 weeks follow-up | Joint health (knee) | As effective as diclofenac overall; OEC significantly better than diclofenac in terms of joint tenderness |

| Klein et al. [99] | Randomized, double-blind, parallel-group (comparator) | Germany | 90 | 6 weeks | Joint health (hip) | Evidence of non-inferiority in OEC compared to diclofenac demonstrated with regard to the WOMAC dimensions of pain, stiffness and physical function, the LAFI score, the investigator and patients’ assessments of efficacy, and the responder rates based on pain and physical function |

| Jayachandran and Khobre [100] | Randomized comparator-controlled trial | India | 30 | 10 days | Temporomandibular joint OA | The OEC was as effective as diclofenac. A combination of OEC as an adjunctive treatment with diclofenac was demonstrated to significantly improve pain management (P < 0.05) compared to OEC or diclofenac alone |

LAFI Lequesne Algofunctional index, OA osteoarthritis, OEC oral enzyme combination therapy, WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index

aClinical trials included in Ueberall meta-analysis [13]

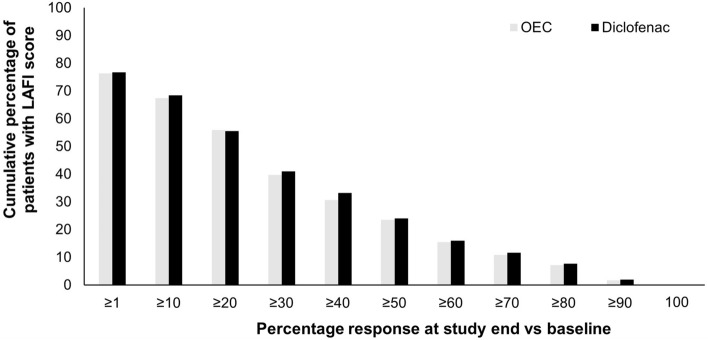

Clinical studies on the effect of this OEC in OA have reported positive treatment outcomes using the following outcome instruments: The Lequesne Algofunctional index (LAFI)—an internationally used, validated patient questionnaire for the self-assessment of OA-related joint pain and functional disability in daily life; the WOMAC scores; and the 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS11) for pain intensity. The LAFI and the numeric rating scale (NRS) are recommended by the European Medicines Agency [97]. A meta-analysis on individual raw patient data (N = 774) pooled from six RCTs compared OEC with the NSAID diclofenac in patients with knee OA [13]. The duration of treatment in the trials varied: 3 weeks in three trials, 6 weeks in two trials, and 12 weeks in one trial. The primary efficacy endpoint was the decrease in LAFI score. The OEC was demonstrated to have comparable efficacy to diclofenac in improving functional disability, mobility, and pain (Table 2) [13]. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) LAFI scores improved from 12.6 ± 2.4 at baseline to 9.1 ± 3.9 at study end (P < 0.001) and from 12.7 ± 2.4 to 9.1 ± 4.2 (P < 0.001) in the OEC and diclofenac groups, respectively. The absolute pain intensity (NRS11) differences at study end compared to baseline were also comparable: –3.5 ± 4.2 and –3.6 ± 4.3 in the OEC and diclofenac groups, respectively (not significant for either parameter) (Table 3) [13]. In addition, the proportions of patients reporting distinct LAFI response rates compared to baseline were comparable between the two treatment groups (Fig. 2) [13].

Table 3.

Primary efficacy endpoint parameters from pooled reanalysis of patient reported data from prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group studies in adult patients with moderate to severe osteoarthritis of the knee treated with an oral combination therapy or the gold standard nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug [13]

| Intention-to-treat population | OEC (n = 348) | Diclofenac (n = 349) | Difference (OEC therapy/diclofenac) |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAFI | |||

| At baseline, mean (SD) | 12.6 (2.4) | 12.7 (2.4) | Not significant |

| At end of treatment, mean (SD) | 9.1 (3.9) | 9.1 (4.2) | Not significant |

| Absolute difference, mean (SD) | –3.5 (4.2) | –3.6 (4.3) | Not significant |

| Relative difference (%), mean (SD) | –27.8 (30.8) | –28.3 (32.1) | Not significant |

| Effect size (Cohen’s d)a | 0.9 | 0.88 | Not significant |

| Significance of LAFI at baseline vs. study end within treatment groups | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| ≤ 7b at baseline, n (%) | 3 (0.9) | 4 (1.1) | Not significant |

| ≤ 7 at end of treatment, n (%) | 115 (33) | 117 (33.5) | Not significant |

| Difference in LAFI ≤ 7 at baseline vs. study end, absolute (relative), n (%) for each treatment | 112 (31) | 113 (32.1) | Not significant |

| Significance of the difference in LAFI ≤ 7 at baseline vs. study end within treatment groups | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |

| Relief ≥ 30%, n (%) | 138 (39.7) | 143 (41) | Not significant |

| Relief ≥ 50%, n (%) | 82 (23.6) | 84 (24.1) | Not significant |

| Relief ≥ 3 points, n (%) | 185 (53.2) | 192 (55) | Not significant |

LAFI Lequesne Algofunctional index, OEC oral enzyme combination therapy, SD standard deviation

aThis Cohen’s d effect size is the standardized mean difference in LAFI for OEC vs. diclofenac

bA LAFI ≤ 7 indicates only minor/mild OA impairment

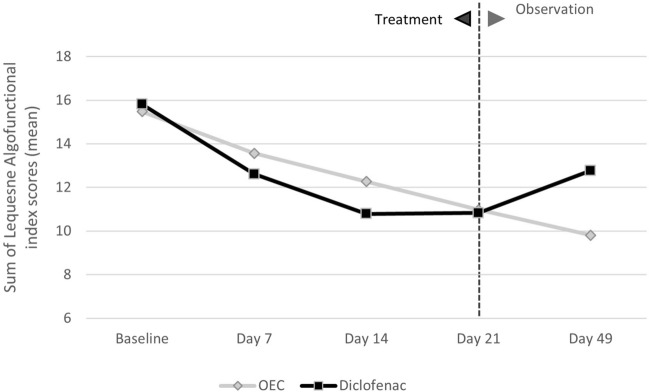

Fig. 2.

LAFI scores from pooled reanalysis of patient-reported data from prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group studies in adult patients with moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis of the knee, treated with an oral enzyme combination or diclofenac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Corresponding relative relief/improvement rates for the OEC vs. diclofenac. Data given for the intent-to-treat population (modified from Ueberall et al. 2016) [13]. LAFI Lequesne Algofunctional index, OEC oral enzyme combination

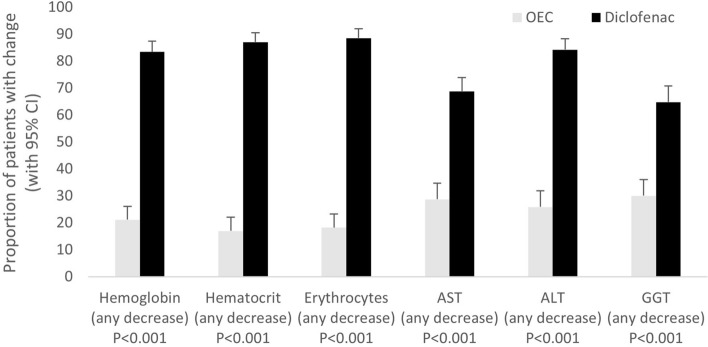

There was also a significant decrease (P < 0.001) in red blood count in 86.3% of the patients in the diclofenac group (vs. 18.8% of the OEC) and a significant increase (P < 0.001) in the mean of the values for liver enzymes aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and gamma-glutamyl transferase in 72.6% patients in the diclofenac group (vs. 28.2% of the OEC; Fig. 3) [13]. The meta-analysis revealed significantly fewer adverse events in the OEC group compared to the diclofenac group (14.7% vs. diclofenac 21.1%); treatment-emergent adverse events leading to discontinuations were seen in 5.9% in the OEC group and 10.2% in the diclofenac group [13].

Fig. 3.

Change in safety-relevant laboratory parameters when treated with an OEC from pooled reanalysis of patient-reported data from prospective, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group studies in adult patients with moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis of the knee treated with an OEC or the gold-standard nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (modified from Ueberall et al. 2016) [13]. Proportion (+ 95% confidence interval) of patients who presented with a decrease in hemoglobin, hematocrit, or erythrocytes, or an increase in AST, ALT, or GGT at study end versus baseline. Data given for the laboratory population and patients treated either with the OEC (white columns) or with diclofenac (black columns). AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, CI confidence interval, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase, OEC oral enzyme combination

The median number of rescue medication (paracetamol) tablets consumed was significantly lower in the OEC group compared to the diclofenac group (P < 0.05) in a randomized, double-blind, placebo- and comparator (diclofenac)-controlled trial investigating 150 patients with moderate to severe OA of the knee over a 12-week duration that was included in the meta-analysis [92]. Another study, also part of the meta-analysis, measured the difference in LAFI scores between the OEC and diclofenac groups at 7, 14, and 21 days of treatment from baseline, and reported no significant difference (P values for the difference in LAFI score between the two groups: 0.356, 0.219, 0.918, respectively). However, a clinical benefit of OEC compared with diclofenac was observed 4 weeks after the end of active treatment, with further reductions in LAFI score (P values for the difference in LAFI score: 0.033; Fig. 4) and overall pain symptoms in the OEC group (P = 0.024), while the parameters increased in the diclofenac group in this observation-only period (Fig. 4) [96]. In a double-blind, randomized, prospective, 6-week study included in the meta-analysis in 103 patients with OA of the knee, the subjective assessment of treatment tolerability was equivalent for both treatment groups: it was reported as “very good” or “good” by physicians and most patients in the OEC treatment group (89.2 and 84.2%, respectively) and in the diclofenac treatment group (86.0 and 86.0%, respectively) [91].

Fig. 4.

Sum of the Lequesne Algofunctional index score (average values over the treatment period) in a randomized, double-blind trial comparing an OEC or the gold-standard nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee [96]. No significant differences were observed at baseline, 7, 14, or 21 days; P = 0.0165 at 49 days (observation period). OEC oral enzyme combination

Tilwe et al. [98] demonstrated the efficacy of the OEC versus diclofenac after a 3-week treatment period and a follow-up period 4 weeks after treatment for pain at rest, pain on movement, joint tenderness and swelling in 50 patients with OA of the knee (Table 2). Pain at rest and pain on movement were assessed subjectively. Joint tenderness was evaluated after applying finger pressure to the knee and joint swelling was recorded with measuring tape. At the end of the 3-week treatment period and during the 4-week follow-up period after treatment stopped, there was a reduction in pain joint tenderness (percentage change of 51.2 and 51.2% for OEC, and 19.5 and 27.8% for diclofenac, respectively), swelling (percentage change of 4.5 and 4.6% for OEC, and 2.1 and 1.0% for diclofenac, respectively) and in pain at rest (percentage change of 42.9 and 50.0% for OEC, and 25.8 and 32.2% for diclofenac, respectively) and pain on movement (percentage change of 39.6 and 37.5% for OEC, and 36.3 and 41.2% for diclofenac, respectively) (Table 2). The reduction in joint tenderness was significantly greater in the patients treated with OEC (P < 0.05) compared to patients treated with diclofenac [98].

Non-inferiority of oral administration of the OEC was also investigated compared to diclofenac (100 mg) in a randomized, double-blind trial of 90 patients with OA of the hip (Table 2) [99]. Within the 6-week treatment period, there were significant improvements in symptoms in both treatment groups based on LAFI score and on all WOMAC subscales (pain, joint stiffness, and physical function). The mean adjusted decreases from baseline to 6 weeks (difference ± standard error of the mean) were: WOMAC pain subscale (OEC – 10.3 ± 1.2; diclofenac – 9.5 ± 1.2), WOMAC joint stiffness subscale (OEC – 3.9 ± 0.5; diclofenac: – 3.6 ± 0.5), WOMAC physical function subscale (OEC – 31.7 ± 3.5; diclofenac: –29.7 ± 3.5) and LAFI score (OEC –2.9 ± 0.5; diclofenac: –2.3 ± 0.5). The global investigator assessments of treatment efficacy were reported as “very good” or “good” in 72.1% of the OEC group versus 61.4% of the diclofenac group (test of non-inferiority: P = 0.001). For most patients, the tolerability of both treatments was judged as “very good” or “good” (62.8% OEC vs. 50.0% diclofenac). This trial revealed significant evidence of non-inferiority of treatment with an OEC versus diclofenac after 6 weeks in patients with OA of the hip with regard to the WOMAC dimensions of pain, stiffness and physical function, LAFI score, the investigator and patients’ assessments of efficacy, and the responder rates based on pain and physical function.

A randomized clinical trial of 30 patients with temporomandibular joint (TMJ) OA examined the effectiveness of the OEC combined with the NSAID diclofenac sodium (50 mg) given to patients twice daily (b.i.d.) for 10 days. There were three treatment groups in this trial: patients were treated with the OEC and diclofenac combined (n = 10), OEC alone (n = 10) or diclofenac alone (n = 10). Pain scoring in this study utilized the NRS system [100]. The mean NRS pain score reduced from a mean score of 7.70 (SD 1.5) on day 1 to 2.8 (SD 1.2) by day 10 for the OEC group and from a mean of 8.80 (SD 1.2) to 3.40 (SD 1.4) by day 10 for the diclofenac group. In the adjunctive therapy patient group with diclofenac and OEC, the mean NRS pain score had notably reduced from a mean of 7.0 (SD 1.6) on day 1 to 0 by day 10. All treatment groups exhibited a decrease in pain from 7.8 ± 1.6 (mean ± SD) on day 1 to a mean of 2.1 ± 1.8 on day 10. There was no significant difference in pain management between the patients treated with OEC or diclofenac alone (P > 0.05). However, for the adjunctive therapy patient group treated with diclofenac and OEC, significantly improved pain management (P < 0.05) in patients with TMJ OA was reported compared to patients treated with NSAID or OEC alone (Table 2) [100].

Considering the positive outcomes of proteolytic enzymes in the treatment of OA, the efficacy and safety of bromelain has also been evaluated with the vegetal proteolytic enzyme papain (extracted from papaya fruits) for the treatment of lower back pain. In an RCT, 20 patients with lumbar spine OA were treated with the standard treatment—the NSAID aceclofenac (100 mg tablet b.i.d.) and 20 patients were treated with the NSAID (100 mg tablet b.i.d.) supplemented with bromelain and papain enzyme (250 mg b.i.d., unknown activity) [101]. Pain intensity measurements included the visual analogue scale (VAS). After 6 weeks of treatment, both groups reported significantly less pain (aceclofenac only: VAS 7.5 ± 1.1 to 7.0 ± 1.0; added enzyme combination: VAS 7.1 ± 1.3 to 5.9 ± 1.5; P = 0.001), and improvement in the Oswestry low back pain questionnaire (aceclofenac only: 54 ± 8.1 to 51 ± 8.5; added enzyme combination: from 56.2 ± 8.7 to 51.6 ± 8.1; P = 0.000) compared to baseline, and improved quality of life among other significant benefits [101]. However, no pre-defined non-inferiority margin was set to measure these similar effects. The safety of the proteolytic enzyme combination was confirmed by examining the effects on patients’ vital signs (no change, P > 0.05) and by the significant reduction of previously elevated liver/kidney enzyme alkaline phosphatase (210.0 ± 55.2 reduced to 196.9 ± 51.0; P = 0.054) and serum creatinine (1.0 ± 0.2 reduced to 0.9 ± 0.1; P = 0.035) values towards the normal range [101].

Discussion

OA is a highly prevalent disease [102] often affecting older people with comorbidities. Comorbidities are a limiting factor for using NSAIDs in the management of pain in these patients with OA. Therefore, it is important to establish a pharmacological alternative to manage OA symptoms in combination with the recommended non-pharmacological modalities. Complementary approaches such as OECs could potentially lead to an improved quality of life in patients with OA as they can lead to the reduction of NSAID use in the OA population and decrease the risk of NSAID-induced cardiovascular and gastrointestinal adverse events.

This narrative review compiles evidence demonstrating that OEC is effective in reducing pain as evaluated with an NRS and improving algofunctional status as assessed by the Lequesne index score of patients with knee OA. Interestingly, OEC is effective on both pain at rest and in motion. The OEC is fast acting, as demonstrated by a significant effect in as little as 10 days of treatment for TMJ OA, and just 3 weeks of treatment for knee and hip OA [93–96, 98–100]. In addition, the efficacy of OECs is comparable to that observed with NSAIDs in knee OA [91, 93–96, 98]. Further, this rapidity of action distinguishes OEC from drugs of the slow-acting symptomatic drug class, including glucosamine and chondroitin, which are clinically efficient after 6–8 weeks according to studies.

The evidence also suggests that OECs are as efficient as diclofenac in reducing pain and improving function, and have a lower risk of adverse events compared to NSAIDs. This could be explained by the differences in their mechanisms of action. NSAIDs act by inhibiting COX-2 activity while OEC undertakes a dual mechanism of action, affecting alpha-2 M via enzyme activity and quercetin, a derivate of rutin, through its antioxidant activity. Since we know that the majority of the NSAID-related adverse effects are associated with the inhibition of COX activities in the small intestine and kidney, we can explain the better safety of OEC compared to diclofenac by a different mode of action. The comparator diclofenac (dose 100–150 mg/day), used in most studies, is considered as efficacious as ibuprofen, naproxen, celecoxib and etoricoxib, and can therefore serve as representative of this group of pain relievers [103].

As movement or training is an important factor in the management of OA, enabling untrained, less mobile patients to adhere to their recommended increased activity by potentially decreasing delayed-onset muscle soreness could be another aspect of the benefits of OEC; however, further investigation is required.

Indeed, there are some limitations to the conclusions of this review: the absence of testing OEC efficacy in specific OA animal models; the number of studies investigating OEC; and the small sample size of the studies included in the meta-analysis [13]. Since the meta-analysis was performed on pooled individual patient-level data, this enlarged the total sample size to a more relevant size and streamlined the data-reporting and evaluation procedures that varied across the six individual trials [91–96].

Further limitations include the lack of an adequate placebo group (however, efficacy results of the active comparator diclofenac were in line with data published) and the relatively short trial duration (up to 12 weeks) in the available OA studies. However, one study demonstrated continued OEC efficacy at least up to 4 weeks after treatment [96]. Long-term OEC safety (up to 2 years) has been seen in other conditions such as multiple sclerosis [104]. OEC therapy in patients with OA is considered a potentially effective option for long-term use owing to the need for sustained pain relief as the disease progresses.

A better understanding of how the mechanism of action of OEC therapy resolves acute inflammation is crucial to aid our understanding of how OEC therapy can also impact chronic tissue inflammation, including fibrosis. Furthermore, the potential structure-modifying effect of OEC therapy on joint tissue has not been demonstrated and there is a need to evaluate OEC therapy on pre-clinical models mimicking mechanically induced, inflammatory-related, or ageing-associated OA. This could be helpful in establishing OEC as a disease-modifying therapy for OA. At present, a placebo-controlled trial to study the mechanism of action of bromelain, trypsin, and rutin versus placebo in patients with OA is ongoing (EudraCT 2020–003,154-80). Another key uncertainty that needs to be addressed is the advantage of combining OEC and flavonoids.

Conclusions

In conclusion, OEC may serve as an effective treatment option for patients with OA due to its similar efficacy and more beneficial safety profile compared to NSAIDs such as diclofenac; however, further research is required.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Sponsorship for this review and the Rapid Service Fee were funded by Nestlé.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors acknowledge Maria Haughton, MSci, CMPP of integrated medhealth communication (imc), UK, for critical review, which was funded by Nestlé.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; Stefanie Rau; data acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: Yves Henrotin, Christoph Michlmayr, Stefanie Rau, Anne-Marie Quirke, Marco Bigoni and Michael Ueberall; Writing – original draft preparation: Anne-Marie Quirke; Writing – review and editing: Yves Henrotin, Christoph Michlmayr, Stefanie Rau, Anne-Marie Quirke, Marco Bigoni and Michael Ueberall.

Disclosures

Yves E Henrotin is the founder and the Executive President of Artialis SA. He received consulting fees from Tilman SA, Laboratoires Expanscience, Nestlé, Naturex and Labrha Laboratories. Christoph Michlmayr has received consulting fees from Nestlé. Stefanie D Rau is the Global Medical Affairs Lead Wobenzym of Nestlé Health Science. Anne-Marie Quirke is a medical writer of imc for which writing support was funded by Nestlé Health Science. Marco Bigoni has received consulting fees from Nestlé. Michael A Ueberall is Medical Director of the Institute of Neurological Sciences, Vice President of the German Pain Association and President of the German Pain League. He receives consulting and honorary fees from AbbVie, Allergan, Allmirall, Amicus Therapeutics, Aristo Pharma, Dermapharm, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal, Kyowa-Kirin, Nestlé, Spectrum Therapeutics, Teva, and Trommsdorff.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Marketed under the brand name of Wobenzym® in Germany, Phlogenzym® for example in Czech Republic and Austria, and Wobenzym Plus.® in the USA, Spain, and Italy.

References

- 1.Constantinescu DS, Campbell MP, Moatshe G, Vap AR. Effects of perioperative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug administration on soft tissue healing: a systematic review of clinical outcomes after sports medicine orthopaedic surgery procedures. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(4):2325967119838873. doi: 10.1177/2325967119838873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang JM, An J. Cytokines, inflammation, and pain. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;45(2):27–37. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e318034194e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medzhitov R. Inflammation 2010: new adventures of an old flame. Cell. 2010;140(6):771–776. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunnumakkara AB, Sailo BL, Banik K, Harsha C, Prasad S, Gupta SC, et al. Chronic diseases, inflammation, and spices: how are they linked? J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s12967-018-1381-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L, Deng H, Cui H, Fang J, Zuo Z, Deng J, et al. Inflammatory responses and inflammation-associated diseases in organs. Oncotarget. 2017;9(6):7204–7218. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal BB, Van Kuiken ME, Iyer LH, Harikumar KB, Sung B. Molecular targets of nutraceuticals derived from dietary spices: potential role in suppression of inflammation and tumorigenesis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234(8):825–849. doi: 10.3181/0902-MR-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore N. Diclofenac potassium 12.5 mg tablets for mild to moderate pain and fever: a review of its pharmacology, clinical efficacy and safety. Clin Drug Investig. 2007;27(3):163–195. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200727030-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore N, Charlesworth A, Van Ganse E, LeParc JM, Jones JK, Wall R, et al. Risk factors for adverse events in analgesic drug users: results from the PAIN study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12(7):601–610. doi: 10.1002/pds.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moore N, Vanganse E, Leparc J, Wall R, Schneid H, Farhan M, et al. A large-scale, randomised clinical trial comparing the tolerability of aspirin, ibuprofen and paracetamol for short-term analgesia. Clin Drug Invest. 1999;18:89–98. doi: 10.2165/00044011-199918020-00001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ong CK, Lirk P, Tan CH, Seymour RA. An evidence-based update on nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Med Res. 2007;5(1):19–34. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2007.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perry TA, Wang X, Nevitt M, Abdelshaheed C, Arden N, Hunter DJ. Association between current medication use and progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60(10):4624–4632. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Micallef J, Soeiro T, Jonville-Béra AP. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, pharmacology, and COVID-19 infection. Therapie. 2020;75(4):355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2020.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueberall MA, Mueller-Schwefe GH, Wigand R, Essner U. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of an oral enzyme combination vs. diclofenac in osteoarthritis of the knee: results of an individual patient-level pooled reanalysis of data from six randomized controlled trials. J Pain Res. 2016;9:941–961. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S108563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leipner J, Saller R. Systemic enzyme therapy in oncology: effect and mode of action. Drugs. 2000;59(4):769–780. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauer D, Müller R, Cott C, Otto A, Naumann M, Birkenmeier G. Modulation of growth factor binding properties of a2-macroglobulin by enzyme therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;47(1):S4–S9. doi: 10.1007/s002800170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kameníček V, Holán P, Franĕk P. Systemic enzyme therapy in the treatment and prevention of post-traumatic and postoperative swelling. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2001;68(1):45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beard J. The enzyme treatment of cancer and its scientific basis. London: Chatto & Windus; 1911. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beuth J. Proteolytic enzyme therapy in evidence-based complementary oncology: fact or fiction? Integr Cancer Ther. 2008;7(4):311–316. doi: 10.1177/1534735408327251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marzin T, Lorkowski G, Reule C, Rau S, Pabst E, Vester JC, et al. Effects of a systemic enzyme therapy in healthy active adults after exhaustive eccentric exercise: a randomised, two-stage, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2016;2(1):e000191. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paradis M-E, Couture P, Gigleux I, Marin J, Vohl M-C, Lamarche B. Impact of systemic enzyme supplementation on low-grade inflammation in humans. PharmaNutrition. 2015;3(3):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.phanu.2015.04.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loeser RF, Goldring SR, Scanzello CR, Goldring MB. Osteoarthritis: a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):1697–1707. doi: 10.1002/art.34453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, et al. 2019 American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation Guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2020;72(2):149–162. doi: 10.1002/acr.24131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Litwic A, Edwards MH, Dennison EM, Cooper C. Epidemiology and burden of osteoarthritis. Br Med Bull. 2013;105:185–199. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palazzo C, Nguyen C, Lefevre-Colau MM, Rannou F, Poiraudeau S. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(3):134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2016.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United Nations - Department of Economic Social Affairs - Population Division. World population ageing 2019: Highlights. 2019 [Available from: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Highlights.pdf.

- 27.Felson DT, Naimark A, Anderson J, Kazis L, Castelli W, Meenan RF. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the elderly. The Framingham Osteoarth Study. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;30(8):914–918. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scarpellini E, Tack J. Obesity and metabolic syndrome: an inflammatory condition. Dig Dis. 2012;30(2):148–153. doi: 10.1159/000336664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marques-Rocha JL, Samblas M, Milagro FI, Bressan J, Martinez JA, Marti A. Noncoding RNAs, cytokines, and inflammation-related diseases. FASEB J. 2015;29(9):3595–3611. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-260323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duclos M. Osteoarthritis, obesity and type 2 diabetes: The weight of waist circumference. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(3):157–160. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frasca D, Blomberg BB, Paganelli R. Aging, obesity, and inflammatory age-related diseases. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1745. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rezus E, Cardoneanu A, Burlui A, Luca A, Codreanu C, Tamba BI, et al. The link between inflammaging and degenerative joint diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):614. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Loeser RF, Collins JA, Diekman BO. Ageing and the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(7):412–420. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis-McDougall FC, Ruchaya PJ, Domenjo-Vila E, Shin Teoh T, Prata L, Cottle BJ, et al. Aged-senescent cells contribute to impaired heart regeneration. Aging Cell. 2019;18(3):e12931. doi: 10.1111/acel.12931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hickson LJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA, Evans TK, Giorgadze N, Hashmi SK, et al. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of dasatinib plus quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine. 2019;47:446–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.08.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr JN, Weigand BM, Palmer AK, Weivoda MM, et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med. 2018;24(8):1246–1256. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0092-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bruyere O, Honvo G, Veronese N, Arden NK, Branco J, Curtis EM, et al. An updated algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(3):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Briani RV, Ferreira AS, Pazzinatto MF, Pappas E, De Oliveira Silva D, Azevedo FM. What interventions can improve quality of life or psychosocial factors of individuals with knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review with meta-analysis of primary outcomes from randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(16):1031–1038. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz JN, Arant KR, Loeser RF. Diagnosis and treatment of hip and knee osteoarthritis: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(6):568–578. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.22171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(11):1578–1589. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernandes L, Hagen KB, Bijlsma JWJ, Andreassen O, Christensen P, Conaghan PG, et al. EULAR recommendations for the non-pharmacological core management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(7):1125. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee—2nd Edition: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guideline 2013 [updated May 18, 2013 Available from: https://aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/osteoarthritis-of-the-knee/osteoarthritis-of-the-knee-2nd-editiion-clinical-practice-guideline.pdf.

- 44.Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):728–738. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arden NK, Perry TA, Bannuru RR, Bruyère O, Cooper C, Haugen IK, et al. Non-surgical management of knee osteoarthritis: comparison of ESCEO and OARSI 2019 guidelines. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(1):59–66. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00523-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruyère O, Honvo G, Veronese N, Arden NK, Branco J, Curtis EM, et al. An updated algorithm recommendation for the management of knee osteoarthritis from the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases (ESCEO) Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(3):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Freedberg DE, Kim LS, Yang YX. The risks and benefits of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: expert review and best practice advice from the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(4):706–715. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.The 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria® Update Expert Panel American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(4):674–694. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Solomon DH, Rassen JA, Glynn RJ, Lee J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. The comparative safety of analgesics in older adults with arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(22):1968–1976. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gustafsson K, Kvist J, Eriksson M, Dell'Isola A, Zhou C, Dahlberg LE, et al. Health status of individuals referred to first-line intervention for hip and knee osteoarthritis compared with the general population: an observational register-based study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(9):e049476. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-049476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cater JH, Wilson MR, Wyatt AR. Alpha-2-macroglobulin, a hypochlorite-regulated chaperone and immune system modulator. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:5410657. doi: 10.1155/2019/5410657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu SM, Patel DD, Pizzo SV. Oxidized alpha2-macroglobulin (alpha2M) differentially regulates receptor binding by cytokines/growth factors: implications for tissue injury and repair mechanisms in inflammation. J Immunol. 1998;161(8):4356–4365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Onken JE, Greer PK, Calingaert B, Hale LP. Bromelain treatment decreases secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by colon biopsies in vitro. Clin Immunol. 2008;126(3):345–352. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hale LP, Haynes BF. Bromelain treatment of human T cells removes CD44, CD45RA, E2/MIC2, CD6, CD7, CD8, and Leu 8/LAM1 surface molecules and markedly enhances CD2-mediated T cell activation. J Immunol. 1992;149(12):3809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiang G, Schinzel R, Simm A, Münch G, Sebekova K, Kasper M, et al. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs)-induced expression of TGF-beta 1 is suppressed by a protease in the tubule cell line LLC-PK1. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16(8):1562–1569. doi: 10.1093/ndt/16.8.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang C-Y, Lai K-Y, Hung L-F, Wu W-L, Liu F-C, Ho L-J. Advanced glycation end products cause collagen II reduction by activating Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 pathway in porcine chondrocytes. Rheumatology. 2011;50(8):1379–1389. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kwon YJ, Koh IH, Chung K, Lee YJ, Kim HS. Association between platelet count and osteoarthritis in women older than 50 years. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 2020;12:1759720x20912861. doi: 10.1177/1759720X20912861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.LaMarre J, Wollenberg GK, Gonias SL, Hayes MA. Cytokine binding and clearance properties of proteinase-activated alpha 2-macroglobulins. Lab Invest. 1991;65(1):3–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anderson RB, Cianciolo GJ, Kennedy MN, Pizzo SV. Alpha 2-macroglobulin binds CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and enhances their immunostimulatory properties by a receptor-dependent mechanism. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(2):381–392. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dalli J, Norling LV, Montero-Melendez T, Federici Canova D, Lashin H, Pavlov AM, et al. Microparticle alpha-2-macroglobulin enhances pro-resolving responses and promotes survival in sepsis. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6(1):27–42. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201303503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Federici Canova D, Pavlov AM, Norling LV, Gobbetti T, Brunelleschi S, Le Fauder P, et al. Alpha-2-macroglobulin loaded microcapsules enhance human leukocyte functions and innate immune response. J Control Release. 2015;217:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brooks B, Leishear K, Aronson R, Howell M, Khakshooy A, Pico M, et al. The use of alpha-2-macroglobulin as a novel treatment for patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;152(3):454–456. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lorkowski G. Gastrointestinal absorption and biological activities of serine and cysteine proteases of animal and plant origin: review on absorption of serine and cysteine proteases. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 2012;4(1):10–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Castell JV, Friedrich G, Kuhn CS, Poppe GE. Intestinal absorption of undegraded proteins in men: presence of bromelain in plasma after oral intake. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(1 Pt 1):G139–G146. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.1.G139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mai F, Maurer A, Bauer S, Roots I. Oral bioavailability of bromelain and trypsin after repeated oral administration of a commercial polyenzyme preparation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;50(6):548. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wald M, Honzikova M, M L. Systemic enzyme support: an overview Nutrition News 2008. http://www.medicinabiomolecular.com.br/biblioteca/pdfs/Biomolecular/mb-0514.pdf.

- 67.Wang S, Wei X, Zhou J, Zhang J, Li K, Chen Q, et al. Identification of α2-macroglobulin as a master inhibitor of cartilage-degrading factors that attenuates the progression of posttraumatic osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(7):1843–1853. doi: 10.1002/art.38576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mazourov VI, Lila AM, Klimko NN, Raimuev KV, Makulova TG. The efficacy of systemic enzyme therapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Immunother. 1997;13(3–4):85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 69.ClinicalTrials.gov. Identifier: NCT05038410, Study to Investigate the Mechanism of Action of an Oral Enzyme Treatment With Bromelain, Trypsin and Rutoside Versus Placebo in Subjects With OsTeoarthritis (WobeSmart): National Library of Medicine (US) 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT05038410.

- 70.Heinicke RM, Gortner WA. Stem bromelain—a new protease preparation from pineapple plants. Econ Bot. 1957;11(3):225–234. doi: 10.1007/BF02860437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bhui K, Prasad S, George J, Shukla Y. Bromelain inhibits COX-2 expression by blocking the activation of MAPK regulated NF-kappa B against skin tumor-initiation triggering mitochondrial death pathway. Cancer Lett. 2009;282(2):167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chakraborty AJ, Mitra S, Tallei TE, Tareq AM, Nainu F, Cicia D, et al. Bromelain a potential bioactive compound: a comprehensive overview from a pharmacological perspective. Life (Basel) 2021;11(4):317. doi: 10.3390/life11040317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bodi T. The effects of oral bromelains on tissue permeability to antibiotics and pain response to bradykinin: double-blind studies on human subjects. Clin Med. 1966;73:61–65. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kumakura S, Yamashita M, Tsurufuji S. Effect of bromelain on kaolin-induced inflammation in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1988;150(3):295–301. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pothacharoen P, Chaiwongsa R, Chanmee T, Insuan O, Wongwichai T, Janchai P, et al. Bromelain extract exerts antiarthritic effects via chondroprotection and the suppression of TNF-α-Induced NF-κB and MAPK signaling. Plants (Basel). 2021;10(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Kasemsuk T, Saengpetch N, Sibmooh N, Unchern S. Improved WOMAC score following 16-week treatment with bromelain for knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(10):2531–2540. doi: 10.1007/s10067-016-3363-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mendes ML, do Nascimento-Júnior EM, Reinheimer DM, Martins-Filho PR. Efficacy of proteolytic enzyme bromelain on health outcomes after third molar surgery. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24(1):e61–e69. doi: 10.4317/medoral.22731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shah D, Mital K. The role of trypsin: chymotrypsin in tissue repair. Adv Ther. 2018;35(1):31–42. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0648-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pratt CW, Pizzo SV. In vivo metabolism of inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor and its proteinase complexes: evidence for proteinase transfer to alpha 2-macroglobulin and alpha 1-proteinase inhibitor. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;248(2):587–596. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lucena F, Foletto V, Mascarin LZ, Tonussi CR. Analgesic and anti-edematogenic effects of oral trypsin were abolished after subdiaphragmatic vagotomy and spinal monoaminergic inhibition in rats. Life Sci. 2016;166:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Adamkiewicz VW, Rice WB, Mc CJ. Antiphlogistic effect of trypsin in normal and in adrenalectomized rats. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1955;33(3):332–339. doi: 10.1139/o55-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wood G, Ziska T, Morgenstern E, Stauder G. Sequential effects of an oral enzyme combination with rutosid in different in vitro and in vivo models of inflammation. Int J Immunother. 1997;13:139–145. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ito C, Yamaguchi K, Shibutani Y, Suzuki K, Yamazaki Y, Komachi H, et al. Anti-inflammatory actions of proteases, bromelain, trypsin and their mixed preparation (author's transl) Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi. 1979;75(3):227–237. doi: 10.1254/fpj.75.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ganeshpurkar A, Saluja AK. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25(2):149–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2016.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ostrakhovitch EA, Afanas’ev IB. Oxidative stress in rheumatoid arthritis leukocytes: suppression by rutin and other antioxidants and chelators. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;62(6):743–7467. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(01)00707-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guardia T, Rotelli AE, Juarez AO, Pelzer LE. Anti-inflammatory properties of plant flavonoids. Effects of rutin, quercetin and hesperidin on adjuvant arthritis in rat. Il Farmaco. 2001;56(9):683–687. doi: 10.1016/S0014-827X(01)01111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T. Clinical strategies and animal models for developing senolytic agents. Exp Gerontol. 2015;68:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.ClinicalTrials.gov, Hickson L. Identifier: NCT02848131, Senescence in Chronic Kidney Disease: National Library of Medicine (US); 2021 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02848131.

- 89.Shao Z, Wang B, Shi Y, Xie C, Huang C, Chen B, et al. Senolytic agent Quercetin ameliorates intervertebral disc degeneration via the Nrf2/NF-κB axis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2021;29(3):413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2020.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Baumuller M. Therapie der Distorsion des oberen Sprunggelenks mit hydrolytischen Enzymen. Praktische Sport-Traumatol Sportmedizin. 1994;10:171–178. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Akhtar NM, Naseer R, Farooqi AZ, Aziz W, Nazir M. Oral enzyme combination versus diclofenac in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee–a double-blind prospective randomized study. Clin Rheumatol. 2004;23(5):410–415. doi: 10.1007/s10067-004-0902-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bolten WW, Glade MJ, Raum S, Ritz BW. The safety and efficacy of an enzyme combination in managing knee osteoarthritis pain in adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis. 2015;2015:251521. doi: 10.1155/2015/251521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Herrera EG. Phlogenzym in the treatment of a monoarticular painful gonarthritis: efficacy and tolerance 1998. https://www.wobenzym.cz/cdweb/mucos/pittompg.htm.

- 94.Klein G, Kullich W. Short-term treatment of painful osteoarthritis of the knee with oral enzymes. Clin Drug Investig. 2000;19(1):15–23. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200019010-00003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Roth SH, Stauder GM, editors. Oral enzyme therapy (Phlogenzym) in osteoarthritis: long-term comparative study against diclofenac. 65th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology; November 11–15, 2001; 2001; San Francisco, CA.

- 96.Singer F, Singer C, Oberleitner H. Phlogenzym® versus diclofenac in the treatment of activated osteoarthritis of the knee. A double-blind prospective randomized study. Int J Immunother. 2001;17:135–141. [Google Scholar]

- 97.European Medicines Agency. Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products used in the treatment of osteoarthritis. 2010 [updated January 20, 2010]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-used-treatment-osteoarthritis_en.pdf.

- 98.Tilwe GH, Beria S, Turakhia NH, Daftary GV, Schiess W. Efficacy and tolerability of oral enzyme therapy as compared to diclofenac in active osteoarthrosis of knee joint: an open randomized controlled clinical trial. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:617–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Klein G, Kullich W, Schnitker J, Schwann H. Efficacy and tolerance of an oral enzyme combination in painful osteoarthritis of the hip A double-blind, randomised study comparing oral enzymes with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24(1):25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jayachandran S, Khobre P. Efficacy of bromelain along with trypsin, rutoside trihydrate enzymes and diclofenac sodium combination therapy for the treatment of TMJ osteoarthritis—a randomised clinical trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(6):Zc09–zc11. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25771.9964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Naeem H, Naqvi SN, Perveen R, Ishaque F, Bano R, Abrar H, et al. Efficiency of proteolytic enzymes in treating lumbar spine osteoarthritis (low back pain) patients and its effects on liver and kidney enzymes. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2020;33(1 (Supplementary)):371–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(1):26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.van Walsem A, Pandhi S, Nixon RM, Guyot P, Karabis A, Moore RA. Relative benefit-risk comparing diclofenac to other traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s13075-015-0554-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Baumhackl U, Kappos L, Radue EW, Freitag P, Guseo A, Daumer M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral hydrolytic enzymes in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2005;11(2):166–168. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1132oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Engwerda CR, Andrew D, Murphy M, Mynott TL. Bromelain activates murine macrophages and natural killer cells in vitro. Cell Immunol. 2001;210(1):5–10. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2001.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fitzhugh DJ, Shan S, Dewhirst MW, Hale LP. Bromelain treatment decreases neutrophil migration to sites of inflammation. Clin Immunol. 2008;128(1):66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Livio M, Bertoni M, DeGaetano G. Effect of bromelain on fibrinogen level, prothrombin complex factors and platelet aggregation in the rat: a preliminary report. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1978;4:49. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Neumayer C, Fügl A, Nanobashvili J, Blumer R, Punz A, Gruber H, et al. Combined enzymatic and antioxidative treatment reduces ischemia-reperfusion injury in rabbit skeletal muscle. J Surg Res. 2006;133(2):150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.McLean PG, Aston D, Sarkar D, Ahluwalia A. Protease-activated receptor-2 activation causes EDHF-like coronary vasodilation: selective preservation in ischemia/reperfusion injury: involvement of lipoxygenase products, VR1 receptors, and C-fibers. Circ Res. 2002;90(4):465–472. doi: 10.1161/hh0402.105372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]