Abstract

Purpose

To estimate the prevalence of computer vision syndrome (CVS) among university medical students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, after establishing remote learning during COVID-19 pandemic and to compare settings of electronic device usage and patterns of CVS protective measures applied by students before and during this pandemic.

Methods

This is an observational descriptive cross-sectional study which included 1st to 5th year medical students who were actively enrolled at the governmental colleges of medicine in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, during the COVID-19 lockdown. The sample size was estimated to be 287 medical students. Participants were asked to volunteer and fill an electronic online questionnaire.

Results

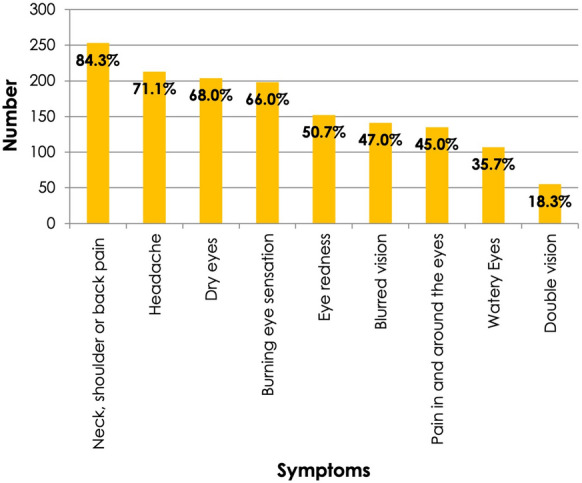

A total of 300 medical students were included in this study. 94.0% reported at least one symptom of CVS, while 67% reported having more than three symptoms. The most frequently reported symptoms were musculoskeletal pain (84.3%), headache (71.1%) and dry eyes (68%). Thirty-eight percent of the students experienced more severe symptoms, while 48% experienced more frequent symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk factors for having three or more symptoms were being a female (p < 0.001) and using electronic devices for longer periods (6.8 h ± 2.8) during COVID-19 lockdown (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

CVS prevalence during COVID-19 era among medical students is high. This necessitates increasing the awareness of CVS and its preventive measures.

Keywords: Computer vision syndrome, Electronic devices, Medical students, COVID-19

Introduction

Nowadays, looking at electronic screens has become an inseparable part of our lives. This was more exaggerated ever since the beginning of the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. In March 2020, The Saudi government announced a lockdown; thus, the Ministry of Education directed all universities to shift teaching to remote learning [1].

Extended hours of studying and spending leisure time on electronic screens may lead to increased prevalence of computer vision syndrome (CVS) which is known as digital eye strain. It is defined by the American Optometric Association as “a group of eye-and vision-related problems that result from prolonged computer, tablet, e-reader and cell phone use” [2]. The most common manifestations of CVS are eye strain, headache, blurred vision, dry eyes as well as neck and shoulder pain. Additionally, poor lighting, glaring at digital screens, improper viewing distances and poor sitting posture may exacerbate and worsen these symptoms.

A study published from Al-Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia, prior to the pandemic concluded that the prevalence of visual symptoms related to computer use was 54.8% among university students [3]. Another study conducted in Nepal has estimated the prevalence of CVS in medical students to be 71.6% [4]. Furthermore, a study in Chennai, India, found that 78.6% of medical students had CVS [5]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, few studies assessed the prevalence of CVS among students. Two studies conducted in India and one in Pakistan showed a high prevalence of CVS with 88%, 93.6% and 98.7% of their participants, respectively, had at least one eye symptom [6–8].

In our study, we aim to estimate the prevalence of CVS among university medical students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, after establishing remote learning during COVID-19 pandemic. We also compared settings of electronic devices used and patterns of CVS protective measures applied by the students before and during COVID-19 pandemic. The symptoms severity and frequency were reported.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This is an observational descriptive questionnaire-based cross-sectional study. The participants were 1st to 5th year male and female medical students of any age. All students were actively enrolled in remote learning at one of the governmental colleges of medicine in Riyadh: King Saud University (KSU), King Saud Bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences (KSAUHS), Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) and Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman University (PNU).

Exclusion criteria included students with known ocular pathology like glaucoma, strabismus, severe trauma, undergone refractive surgery for vision correction within the last 6 months or other ocular or eyelid surgeries that may affect the ocular surface health. Also, students with underlying systemic illness like hypertension, diabetes, autoimmune disorders or using medications that have known visual side effects like (isotretinoin, bisphosphonates, cyclosporine, tetracyclines, hydroxychloroquine, anti-tuberculosis and anticholinergics) and those who apply topical eye drops other than artificial tears (corticosteroids, antibiotics, antivirals, glaucoma medications, anesthetics or mydriatics) were excluded from the study.

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the College of Medicine, King Saud University (approval No. E-21-5842) and in accordance with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Sample size estimation

The sample size of the study was estimated based on the average prevalence of computer vision syndrome among medical students (75.1%) [4, 5], with a precision of ± 5%, and 95% confidence interval. The minimal sample size required was calculated to be 287 participants. However, considering an additional 20% participants to have an adequate sample size and to enhance the generalizability of the results, the final sample size was estimated to be 345 participants.

Data collection tool

The data of the study were collected through a questionnaire which was adapted from two validated questionnaires of previously published papers [9, 10]. The final questionnaire consisted of 3 sections: first section collected demographic and basic information such as gender, age, use of medications that might affect vision and any ocular diseases [9]. The second section assessed the awareness, frequency (never, occasionally, often, always) and severity (no symptoms, mild, moderate, severe) of eye symptoms such as headache, burning eye sensation, eye dryness and musculoskeletal pain before and during COVID-19 pandemic [10].

However, the last section inquired about the patterns of CVS protective measures applied and settings of electronic devices used for studying before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, we have asked the participants to answer questions regarding the pre-pandemic times, and the same questions regarding the last 3 months during the pandemic. Those questions were about the time spent on electronic devices, total hours of studying per day, taking breaks, screen location during studying, screen brightness and room illumination [10].

The developed questionnaire was then reviewed by two senior faculty members, an ophthalmologist consultant and a public health faculty member. They have reviewed the questions accuracy and arranged them in a sequential manner.

A pilot study was conducted on 15 students to assess their understanding and the time needed to complete the questionnaire. No language or understanding difficulties were noted, the average time needed to complete the survey was five minutes.

Data collection

Data collection was carried out in the period from April to May 2021 through an electronic self-administered questionnaire distributed to medical students through the medical students’ council of every college and social media platforms.

An online informed consent form appeared on the first page of the electronic questionnaire; the informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The participants had a clear explanation of the benefits of their participation and any potential risks. The participation in the study was completely voluntary and the participants had the right not to complete the study at any time. Confidentiality and privacy of each participant have been assured. The participants’ details have been completely anonymous, and they have been used for data analysis only.

Statistical analysis

Data were collected, managed and coded in a spreadsheet using Microsoft Excel 2010® software and they were analyzed using SPSS® version 21.0 (IBM Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Descriptive analysis was done, where categorical variables were presented in the form of frequencies and percentages. Data exploration using Shapiro–Wilk test was done for the continuous variables where the data were found to be normally distributed. Mean ± SD [Range] was reported, otherwise median (interquartile range) (IQR) was reported. Independent t test and paired samples t test were used for comparisons between two groups for the continuous variables and Chi-squared test for comparing proportions among the studied groups. Any output with a p below 0.05 was interpreted as an indicator of statistical significance.

Results

A total of 300 respondents out of 375 medical students were included in this study. Seventy-five responses were excluded after applying the exclusion criteria. The majority of respondents were females, (58.6%). (Table 1). When assessing the awareness of CVS, 76.3% of our participants never heard of the syndrome. Ninety-four percent of the participants reported at least one symptom of CVS, while 67% of them reported more than three CVS symptoms. The most frequently reported symptoms in our study were musculoskeletal: neck, shoulder and back pain (84.3%), headache (71.1%) and dry eyes (68%). (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean ± SD [Range], median (IQR) | 21.5 ± 1.9 (18–29), 21 (20–33) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 124 (41.3) |

| Female | 176 (58.7) |

| Ocular diseases | |

| Nearsightedness (myopia) | 111 (37.0) |

| Astigmatism | 41 (13.7) |

| Farsightedness (hyperopia) | 22 (7.3) |

| Vision corrective surgery within the last 6 months; like LASIK | 1 (0.3) |

| None | 164 (54.7) |

| Artificial tears use | |

| Yes | 132 (44) |

| Corrective lens use | |

| Yes | 161 (53.7) |

| Type of corrective lens (n = 161) | |

| Eye glasses | 151 (93.8) |

| Contact lens | 10 (6.2) |

Fig. 1.

The most frequently reported symptoms

The risk factors for experiencing three or more symptoms of CVS were more prevalent among females (p value < 0.001) OR 3.29 [2.00–5.43] 95% CI and students who used electronic devices for longer periods (6.8 h ± 2.8) during COVID-19 (p value < 0.001) OR 1.21 [1.09–1.35] 95% CI. Refractive errors: myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism were all non-significant factors to have more CVS symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Risk factors of having more than 3 symptoms

| Risk factor | ≤ 3 symptoms (n = 99) n (%) | > 3 symptoms (n = 201) n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male (n = 124) | 60 (48.4) | 64 (51.6) | < 0.001* |

| Female (n = 176) | 39 (22.2) | 137 (77.8) | |

| Myopia | |||

| Yes (n = 111) | 35 (31.5) | 76 (68.5) | 0.678 |

| No (n = 189) | 64 (33.9) | 125 (66.1) | |

| Hyperopia | |||

| Yes (n = 22) | 6 (27.3) | 16 (72.7) | 0.553 |

| No (n = 278) | 93 (33.5) | 185 (66.5) | |

| Astigmatism | |||

| Yes (n = 41) | 11 (26.8) | 30 (73.2) | 0.366 |

| No (n = 259) | 88 (34.0) | 171 (66.0) | |

| Use of corrective lens | |||

| Yes (n = 161) | 50 (31.1) | 111 (68.9) | 0.441 |

| No (n = 139) | 49(35.3) | 90 (64.7) | |

| Duration of device use in hours pre-COVID-19 Mean ± SD | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 5.3 ± 2.1 | 0.164 |

| Duration of device use in hours during COVID-19 Mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 2.3 | 6.8 ± 2.8 | < 0.001* |

| P value | 0.023* | < 0.001* | |

*Statistically significant at 5% level of significance

Our study explored the frequency and severity of CVS symptoms among study participants. During the COVID-19 pandemic, symptoms were reported to be more severe and more frequent by 38% and 48.3% of students, respectively, as compared to pre-pandemic levels (Table 3). Medical students, who reported longer duration of use, experienced more severe and frequent symptoms (p value < 0.001) (Table 4). On the other hand, the association between taking breaks and severity and frequency of symptoms was not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Frequency and severity of eye symptoms

| Question | n (%) |

|---|---|

| How often do you experience these symptoms during/after the use of electronic devices, in the last 3 months? | |

| Always (symptoms occurring almost everyday) | 26 (8.7) |

| Often (symptoms occurring 2–3 times a week) | 94 (31.3) |

| Occasionally (symptoms in occurring sporadic episodes or once a week) | 141 (47.0) |

| Never | 39 (13.0) |

| In comparison with pre-COVID-19 era, have you noticed the symptoms listed above becoming more severe during COVID-19 pandemic than before? | |

| They became more severe | 115 (38.3) |

| No change in severity | 168 (56.0) |

| They became less severe | 17 (5.7) |

| In comparison with pre-COVID-19 era, have you noticed the symptoms listed above becoming more frequent during COVID-19 pandemic than before? | |

| They became more frequent | 145 (48.3) |

| No change in frequency | 147 (49.0) |

| They became less frequent | 8 (2.7) |

Table 4.

Association between severity and frequency of symptoms and duration of device use

| More severe (n = 115) | Remains same or less severe (n = 185) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of device use in hours pre-COVID-19 Mean ± SD | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 5.0 ± 2.2 | 0.055 |

| Duration of device use in hours during COVID-19 Mean ± SD | 7.5 ± 2.8 | 5.8 ± 2.5 | < 0.001* |

| P value | < 0.001* | 0.001* |

| More frequent (n = 145) | Remains same or less frequent (n = 155) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of device use in hours pre-COVID-19 Mean ± SD | 5.3 ± 1.9 | 4.9 ± 2.2 | 0.094 |

| Duration of device use in hours during COVID-19 Mean ± SD | 7.1 ± 2.8 | 5.9 ± 2.4 | < 0.001* |

| P value | < 0.001* | < 0.001* |

*Statistically significant at 5% level of significance

In comparing the settings of electronic device usage before and during COVID-19 pandemic, one quarter (26%) of the respondents reported spending 8 h or more on electronic devices pre-COVID-19. During the pandemic, the percentage increased up to 56.7% (p value < 0.001). Also, the average of total studying hours on devices was 5.1 h pre-COVID-19 had increased to 6.4 h during the pandemic (p value < 0.001). The preferred monitor brightness and room illumination variance before and during the pandemic was not statistically significant (Table 5).

Table 5.

Settings of electronic device usage before and during COVID-19 pandemic

| Variable | Group | Pre-COVID-19 n (%) | During COVID-19 n (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In general, how many hours do you spend on electronic devices a day? | Less than 2 Hours | 6 (2.0) | 3 (1.0) | 0.314 |

| 2 < 4 Hours | 21 (7.0) | 2 (0.7) | < 0.001* | |

| 4 to < 6 Hours | 96 (32.0) | 24 (8.0) | < 0.001* | |

| 6 to < 8 Hours | 99 (33.0) | 101 (33.7) | 0.856 | |

| 8 h or more | 78 (26.0) | 170 (56.7) | < 0.001* | |

| On average, total hours of studying hours per day, mean ± SD [range], median (IQR) | 5.1 ± 2.1 (1–15), 5 (4–6) | 6.4 ± 2.7 (1–20), 6 (5–8) | < 0.001* | |

| Which of the following is the most device you use? | Desktop | 18 (6.0) | 21 (7.0) | 0.620 |

| Laptop | 41 (13.7) | 55 (18.3) | 0.125 | |

| iPad/tablets | 137 (45.7) | 155 (51.7) | 0.142 | |

| Smartphone | 104 (34.7) | 69 (23.0) | 0.002* | |

| What is your preferred monitor brightness? | High brightness | 39 (13.0) | 35 (11.7) | 0.629 |

| Moderate brightness | 159 (53.0) | 165 (55.0) | 0.623 | |

| Low brightness | 102 (34.0) | 100 (33.3) | 0.856 | |

| How well illuminated is the room during your usage of electronic devices? | Highly illuminated | 58 (19.3) | 61 (20.3) | 0.759 |

| Moderately illuminated | 161 (53.7) | 157 (52.3) | 0.731 | |

| Slightly illuminated | 81 (27.0) | 82 (27.3) | 0.934 |

*Statistically significant at 5% level of significance

Minute differences were found in application of CVS protective measures before and during COVID-19 pandemic with no statistical significance as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Pattern of CVS protective measures before and during COVID-19 pandemic

| Phrase | Groups | Pre-COVID-19 | During COVID-19 | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| You take short breaks every 20 min for 20 s and looking at objects that are at least 20 feet away (20–20-20 rule) | Always | 5 | (1.7) | 9 | (3.0) | 0.294 |

| Usually | 19 | (6.3) | 20 | (6.7) | 0.843 | |

| Sometimes | 51 | (17.0) | 42 | (14.0) | 0.310 | |

| Rarely | 76 | (25.3) | 78 | (26.0) | 0.845 | |

| Never | 149 | (49.7) | 151 | (50.3) | 0.883 | |

| You locate the screen to be 20–28 inches from the eyes (more than arm & forearm length) | Always | 18 | (6.0) | 20 | (6.7) | 0.725 |

| Usually | 31 | (10.3) | 36 | (12.0) | 0.509 | |

| Sometimes | 63 | (21.0) | 57 | (19.0) | 0.541 | |

| Rarely | 87 | (29.0) | 88 | (29.3) | 0.936 | |

| Never | 101 | (33.7) | 99 | (33.0) | 0.856 | |

| You locate the screen to be at the level of your face | Always | 40 | (13.3) | 38 | (12.7) | 0.827 |

| Usually | 51 | (17.0) | 61 | (20.3) | 0.300 | |

| Sometimes | 84 | (28.0) | 85 | (28.3) | 0.935 | |

| Rarely | 67 | (22.3) | 58 | (19.3) | 0.366 | |

| Never | 58 | (19.3) | 58 | (19.3) | 0.998 | |

| While using electronic devices, your seating position is up right with a straight back | Always | 16 | (5.3) | 18 | (6.0) | 0.711 |

| Usually | 53 | (17.7) | 57 | (19.0) | 0.681 | |

| Sometimes | 95 | (31.7) | 98 | (32.7) | 0.793 | |

| Rarely | 92 | (30.7) | 90 | (30.0) | 0.852 | |

| Never | 44 | (14.7) | 37 | (12.3) | 0.390 | |

| While using electronic devices, you use your corrective lens (contact lenses/glasses)? | Always | 82 | (27.3) | 87 | (29.0) | 0.644 |

| Usually | 30 | (10.0) | 31 | (10.3) | 0.903 | |

| Sometimes | 29 | (9.7) | 30 | (10.0) | 0.902 | |

| Rarely | 27 | (9.0) | 21 | (7.0) | 0.367 | |

| Never | 132 | (44.0) | 131 | (43.7) | 0.941 | |

Discussion

The Ministry of Education of Saudi Arabia directed the universities and schools to shift to remote learning, so students can attend all their classes from home via electronic platforms like blackboard, ZOOM and Microsoft Teams to ensure their safety and health. But the continuation of E-learning during the COVID-19 era has some drawbacks.

High prevalence of CVS was observed. In our study, 282 students reported at least one symptom (94%). This is consistent with the prevalence reported during COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan (98.7%) and India (88%). [6, 7] This was also similar to the prevalence in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, before the pandemic (97.3%) [11]. However, in the previous study, there was no exclusion of students with ocular or systemic illness or to those applying medications with known visual side effects. However, in our study, all those confounders were eliminated.

Moreover, 67% of our participants reported having more than three symptoms of CVS. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has calculated the prevalence based on having more than three symptoms. We believe this percentage might be more precise to estimate the prevalence of CVS syndrome.

In the current study, the most reported symptoms were neck, shoulder and back pain, headache and dry eyes, which is similar to what was reported in a previous study before the pandemic among business and medical college students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia [10], but with a higher percentage in our study, it could be explained by the increase in duration of electronic devices usage during COVID-19 pandemic.

In our study, being a female increased the risk of having three or more symptoms with a statistical significance. It is matching with what was reported in multiple studies done in Majmaah and Jeddah between 2018 and 2020 [3, 9, 11]. This could be attributed to the higher prevalence of dry eyes, cosmetics use among females [12] and to the gender difference in response to pain [13].

The relation between refractive errors and developing CVS has conflicting results in the literature. In our study, we found that having refractive errors as myopia, hyperopia or astigmatism is not a risk factor for having more than three symptoms of CVS. This is almost similar to a national study conducted in Jeddah which found that myopia and hyperopia were not associated with CVS, but astigmatism showed significant association with more symptoms [9]. In contrast, in another national study in Al-Qassim region, there was a significant relation between myopia and CVS, especially those corrected with contact lenses reported more severe symptoms [14]. On the international level, a systematic review concluded that those who have refractive errors are at a higher risk to develop CVS or suffer from more severe symptoms of CVS [15]. Moreover, a study conducted in Nepal found that students who have myopia corrected with glasses are at higher risk to develop CVS. However, the study did not find a statistically significant difference between students who had high myopia and those who had low and moderate myopia in regard to developing CVS [16]. Differences might be due to sample size variation, or the variable use of corrective lenses while using electronic devices among the study populations.

Along with the increased dependence on online education during the pandemic, safe habits in digital device use have been recommended especially in regard to the duration of device usage as we found it to be one of the most statistically significant factors in our study. We found out that students who used electronic devices for longer durations during COVID-19 (6.8 h ± 2.8) reported 3 or more symptoms of CVS with p value (< 0.001). The percentage of our respondents who reported spending 8 h or more using electronic devices increased significantly from only 26% pre-COVID-19 to 56.7% during the pandemic (p value < 0.001). Also, the average total studying hours increased from a mean of 5.1 h reported pre-pandemic to a mean of 6.4 h during this era with p value (< 0.001).

The increase in symptoms due to longer device use is corresponding with previous studies that have reported participants experiencing more symptoms after using devices for more than six hours a day [17, 18].On the opposite side, one study reported that there is no association between the duration of usage of the device and the number of symptoms [11]. This could be explained by the fact that all previous studies relied on recalling subjective information rather than objective measurements of digital devices usage.

The patterns of CVS protective measures applied by our participants remained unchanged pre and during COVID-19. The majority of the study population were not following preventive measures such as using the 20–20–20 rule, locating the screen at 20–28 inch from your eyes, reducing hours of use, appropriate room illumination and monitor the brightness.

These results correlated with the poor level of awareness among our study participants. As 76.3% of our participants never heard of the syndrome. More awareness campaigns to educate the population about CVS protective measures and the proper use of electronic devices are needed.

Recommendations and limitations

Our study highlights a high prevalence of CVS among medical students which was expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown and shifting to online education. Therefore, we encourage future researchers to perform larger community-based studies as there is an expected increase in digitalization for educational and recreational purposes as well.

In our study, we addressed the pre-pandemic data by asking the participants to recall their experience prior to the pandemic in regard to frequency and severity of CVS symptoms. In addition, they were also asked to recall information about the sittings of electronic devices usage and pattern of CVS protective measures application in the 3-month period prior to the study. We believe this method may affect the accuracy and reliability of the results due to recall bias. Therefore, we encourage future researchers to follow more objective ways for assessment.

We encourage future researchers to address any chronic musculoskeletal pain or primary headache to eliminate them as they work as confounders.

Conclusion

A high prevalence of CVS symptoms during COVID-19 pandemic was reported. The most commonly reported symptoms were musculoskeletal pain, headache and dry eyes. Risk factors for having three or more symptoms were being a female and using electronic devices for more than 6.8 h. The increased duration of electronic device usage during COVID-19 pandemic was associated with more frequent and severe CVS symptoms. The percentage of students spending 8 h or more on electronic devices doubled during the pandemic. Our study results reflected the need to increase the awareness of CVS and its protective measures through introducing the subject in university’s curriculum and frequent awareness campaigns.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Abdullah N. Almousa, Email: anmousa@ksu.edu.sa

Munirah Z. Aldofyan, Email: Munirah.Aldofyan@gmail.com

Bushra A. Kokandi, Email: Bushrakokandi@gmail.com

Haneen E. Alsubki, Email: haneen.alsubki@gmail.com

Rawan S. Alqahtani, Email: ra1.s.alqahtani@gmail.com

Priscilla Gikandi, Email: pgikandi.c@ksu.edu.sa.

Shatha G. Alghaihb, Email: shathamed436@gmail.com

References

- 1.Saudi press agency https://www.spa.gov.sa/2044433. Accessed 21 Sep 2021

- 2.American Optometric Association. Computer vision syndrome: https://www.aoa.org/healthy-eyes/eye-and-vision-conditions/computer-vision-syndrome?sso=y. Accessed 28 Feb 2021

- 3.Sirajudeen MS, Muthusamy H, Alqahtani M, Waly M, Jilani AK. Computer-related health problems among university students in Majmaah region. Saudi Arabia Biomed Res. 2018;29(11):2405–2415. doi: 10.4066/biomedicalresearch.61-18-418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kharel SR, Khatri A. Knowledge, attitude and practice of computer vision syndrome among medical students and its impact on ocular morbidity. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2018;16(3):291–296. doi: 10.3126/jnhrc.v16i3.21426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logaraj M, Madhupriya V, Hegde S. Computer vision syndrome and associated factors among medical and engineering students in Chennai. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4(2):179–185. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.129028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noreen K, Ali K, Aftab K, Umar M. Computer vision syndrome (CVS) and its associated risk factors among undergraduate medical students in midst of COVID-19. Pak J Ophthalmol. 2021;37(1):102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah K, Desai S, Lo H, et al. COVID 19 and ophthalmic morbidity among college students attending online teaching. Indian J Forensic Med Toxicol. 2021;15(1):413–421. doi: 10.37506/ijfmt.v15i1.13442. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahkir FA, Grandee SS. Impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on digital device-related ocular health. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2020;68(11):2378–2383. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2306_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abudawood GA, Ashi HM, Almarzouki NK. Computer Vision syndrome among undergraduate medical students in King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah. Saudi Arab J Ophthalmol. 2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/2789376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al Tawil L, Aldokhayel S, Zeitouni L, Qadoumi T, Hussein S, Ahamed SS. Prevalence of self-reported computer vision syndrome symptoms and its associated factors among university students. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;30(1):189–195. doi: 10.1177/1120672118815110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Altalhi AA, Khayyat W, Khojah O, Alsalmi M, Almarzouki H. Computer vision syndrome among health sciences students in Saudi Arabia: prevalence and risk factors. Cureus. 2020;12(2):10–13. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blehm C, Vishnu S, Khattak A, Mitra S, Yee RW. Computer vision syndrome: a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2005;50(3):253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pieretti S, Di Giannuario A, Di Giovannandrea R, et al. Gender differences in pain and its relief. Ann dell’Ist Super Sanita. 2016;52(2):184–189. doi: 10.4415/ANN_16_02_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al Rashidi SH, Alhumaidan H. Computer vision syndrome prevalence, knowledge and associated factors among Saudi Arabia University students: is it a serious problem? Int J Health Sc. 2017;11(5):17–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan Z, Hu L, Chen H, Lu F. Computer vision syndrome: a widely spreading but largely unknown epidemic among computer users. Comput Hum Behav. 2008;24(5):2026–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2007.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy SC, Low CK, Lim YP, Low LL, Mardina F, Nursaleha MP. Computer vision syndrome: a study of knowledge and practices in university students. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2013;5(2):161–168. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v5i2.8707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahman ZA, Sanip S. Computer user: demographic and computer related factors that predispose user to get computer vision syndrome. Int J Bus Humanit Technol. 2011;1(2):84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohan A, Sen P, Shah C, Jain E, Jain S. Prevalence and risk factor assessment of digital eye strain among children using online e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: digital eye strain among kids (DESK study-1) Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(1):140–144. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2535_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]