Abstract

In this systematic review, we aimed to identify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children/adolescents with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The protocol was registered on PROSPERO CRD42021255848. Articles were selected from PubMed, Embase, and LILACS according to these characteristics: patients from zero to 18 years old, exposed to the COVID-19 pandemic, impact on social communication/interaction and restricted/repetitive behavior domains. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was used to assess methodological quality and the risk of bias. Of the 351 articles initially identified, 26 were finally included with information on 8,610 patients. Although the studies were heterogeneous, they indicated that the pandemic-related issues experienced by patients with ASD were mostly manifested in their behavior and sleep patterns.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40489-022-00344-4.

Keywords: Neurodevelopmental disorder, Autism, Pediatrics, SARS-CoV-2, Coronavirus

The pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), known as COVID-19, was so officially declared by the World Health Organization on March 11, 2020 (Ghebreyesus, 2020). Thereafter, classic public health measures were mandated to quell viral contamination and its spread (World Health Organization, 2020). Among these are measures such as isolation and quarantine, social distancing, and community containment (Wilder-Smith & Freedman, 2020).

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder known for its wide range of symptoms, which include poor social-emotional reciprocity, restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior, limited interests, atypical sensory sensitivity, and behavioral issues. Maintaining routines is crucial for the functioning and well-being of patients with ASD (Lindor et al., 2019). Owing to the fast spread of SARS-CoV-2, necessary measures were taken to protect the worldwide population by minimizing viral infections spread by person-to-person contact. These preventative measures were particularly harmful to ASD patients, especially children and adolescents, because their abruptly disrupted routines are integral to their well-being (Amorim et al., 2020; Nuñez et al., 2021).

Several studies have examined how pandemic restrictions have influenced ASD patients regarding relevant aspects of their daily lives, such as changes in routines, behavior, socialization, autonomy, therapies, sleep, eating, and distance learning (Amorim et al., 2020; Colizzi et al., 2020; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021). Considering the available information, it is of great interest how these patients and their families have coped with the pandemic.

The social restriction imposed on children and adolescents with ASD affected their daily routines and access to therapies, which likely influenced the main domains affected by this disorder (behavior, communication, socialization, and autonomy) (Bhat, 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021).

Therefore, this work aimed to identify, through a systematic review (SR), the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the main domains affected in children/adolescents with ASD.

Given that routine is crucial to the well-being of patients with ASD, and that the restrictions imposed during the pandemic disrupted routines, we hypothesize that the consequences thereof likely include increased behavioral issues, restricted socialization, decreased autonomy, reduced communication abilities, and worse sleeping patterns.

Methods

This SR was performed in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic reviews (https://training.cochrane.org/handbook) and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2015). The review protocol is registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021255848).

Search Strategy

Eligible articles were selected from two online databases, PubMed and Embase on May 7, 2021, and then updated on December 1, 2021, when the LILACS database was added. The following PECO framework was implemented (1) Patient: ASD patients; (2) Exposure: COVID-19 pandemic; (3) Comparison: none; (4) Outcome: social communication/interaction and restricted/repetitive behavior. Inclusion criteria were clinical trials, and cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. The outcomes were selected based on previous literature reports and on the domains affected in ASD as reported in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM V) (American Association Psychiatric, n.d.). Exclusion criteria were case series and case reports, paper reviews, debates, editorials, letters to the editor, experts’ opinions, and studies that did not conform to the PECO framework developed for this SR. Filters added to the search strategy were language: English, Portuguese, and Spanish; publication date: since December 2019; and age: from zero to 18 years old.

The databases were queried as follows. Pubmed: (("covid 19"[All Fields] OR "sars cov 2"[All Fields]) AND (("english"[Language] OR "portuguese"[Language] OR "spanish"[Language]) AND ("infant"[MeSH Terms] OR "child"[MeSH Terms] OR "adolescent"[MeSH Terms])) AND "autism spectrum disorder"[All Fields]) AND ((english[Filter] OR portuguese[Filter] OR spanish[Filter]) AND (allchild[Filter])); Embase: autism' AND ('severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2' OR 'coronavirus disease 2019') AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [infant]/lim OR [newborn]/lim OR [preschool]/lim OR [school]/lim) AND ([english]/lim OR [portuguese]/lim OR [spanish]/lim); and LILACS: (autism spectrum disorder) AND (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) OR (covid 19) AND (db:("LILACS") AND mj:("Autistic Disorder") AND la:("pt" OR "en" OR "es")).

Screening and Eligibility

All articles resulting from the three database searches were imported into Rayyan (https://rayyan.qcri.org). After these were merged, duplicates were selected by the software and excluded once the titles and authors were confirmed. In a second step, papers were screened based on their titles and abstracts. Any study that clearly did not assess the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to children and adolescents with ASD was excluded. In the third step, full-text articles were imported into the Mendeley bibliographic software package for full reading and data extraction. To maximize consistency, both selection phases were performed independently by one of three pairs of reviewers. Any disagreements about study inclusion or exclusion during this process were resolved in consensus discussions with a seventh reviewer.

Data Extraction

The same three reviewer pairs extracted data from the included papers into an Excel spreadsheet. All extractions were discussed with a seventh reviewer. The following data were extracted from every study: article characteristics (authors, publication year, journal name, DOI, title, objective, and study design); and sample characteristics (sample size, gender, age, country of origin, comparison periods and comparisons between groups of participants, ASD level, evaluations applied, and outcomes).

Methodological Quality Assessment

Two adapted versions of the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for longitudinal (Wells et al., 2000) and cross-sectional studies (Modesti et al., 2016) were used to assess the methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies. The NOS for longitudinal studies was adapted to our study needs, reaching a total of eight stars. We excluded the follow-up period since it is not known how long-term the patients with ASD are expected to show differences in outcomes. The question concerning the adequacy of follow-up was graded according to sample loss. Studies were categorized as high quality when they met ≥ 90% of the criteria, medium between 50 and 90%, and low when < 50% (Viner et al., 2022). The hypotheses were confirmed when articles with high- or medium-quality evidence showed an increase in behavioral issues, restricted socialization, decreased autonomy, reduced communication abilities, and worse sleeping patterns.

Variables Studied

The variables analyzed in this SR are domains affected in ASD, such as patients’ routines, behavior, and therapies; habits (e.g., sleep, eating); abilities (e.g., communication, socialization, autonomy); and whether there were changes in the time spent on screen use and how patients dealt with distance learning during this period. Questions were dichotomic, multiple choices or open-ended.

Results

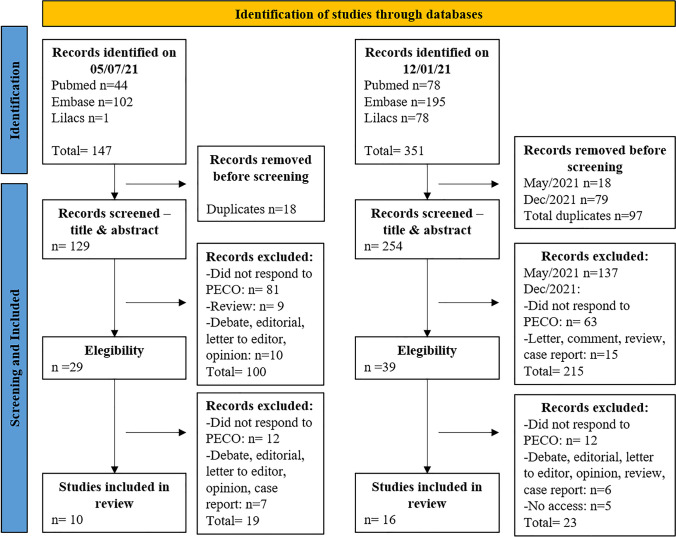

A total of 147 studies were identified from the PubMed and Embase databases in May 2021, 10 of which were included in this SR. An updated search performed in December 2021 that also included the LILACS database revealed an additional 177 papers. At this point, 351 articles were identified, and 16 new articles were included for analysis, resulting in a total sample of 26 papers. The PRISMA flow chart below depicts the steps involved in the development of this SR (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of systematic article search and selection process

Characteristics of Studies

All 26 observational studies included were published between 2020 and 2021. Eighteen (69%) were longitudinal (5 prospective, 13 retrospective) and 8 (31%) were cross-sectional studies. According to NOS, 16 (62%) articles were low quality and 10 (38%) medium quality.

Data from 8610 patients with ASD were analyzed, of whom 6856 (80%) were male. Five papers (19%) compared ASD patients with 1046 neurotypical children/adolescents as controls, of whom 725 (69%) were male. Two studies did not describe the number of participants, while three papers did not describe the gender distribution among the patients included. Six out of 26 studies (23%) described the ASD level of the participants, while three (11%) only described the communication level.

Concerning the period of the COVID-19 pandemic studied, 10 articles (38%) compared before with during the pandemic (Bhat, 2021; Cardy et al., 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020; Garcia et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022; Kawabe et al., 2020; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Mutluer et al., 2020; Vasa et al., 2021), 12 (47%) defined specific pandemic periods (e.g., before versus during quarantine, confinement, or lockdown) (Amorim et al., 2020; Berard et al., 2021; Bruni et al., 2021, 2022; Levante et al., 2021; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2020), while the final four (15%) compared different pandemic moments.

General information on the eligible papers is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

General data extraction from eligible articles

| Article data and country sample | Groups comparison | Gender F/M (%) | Age (years) ± SD (or range or IQR) | ASD levels | Study design | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amorim et al., 2020 Portugal | ASD vs. Control, before vs. during quarantine | ASD: 5/38 (12/ 88) Control: 26/30 (46/ 54) | 9.86 ± 3.08 | not described | Cross-sectional | 3/10 (low quality) |

| Berard et al., 2021 France | Before vs. during confinement | 49/190 (20/80) | 9.11 ± 4.0 | ADOS severity: 7.24 SD: 1.82 | Cross-sectional | 5/10 (medium quality) |

| Bhat et al., 2021 USA | Before vs. during pandemic | 1235/5158 (19/81) | 1.58–18 years | not described | Cross-sectional | 6/10 (medium quality) |

| Bruni et al., 2021 Italy | ASD vs. Control, before vs. during lockdown | ASD: 16/84 (16/84) Control: 58/282 (17/83) | 4–18 | not described | Longitudinal | 4/8 (medium quality) |

| Bruni et al., 2022 Italy | Before vs. during lockdown | 18/93 (16/84) | 4–18 | not described | Cross-sectional | 4/10 (low quality) |

| Cardy et al., 2021 Canada | Before vs. during pandemic | 99/28 (78/22) | 11.7 ± 4.06 | 83% communicate verbally | Longitudinal | 4/8 (medium quality) |

| Colizzi et al., 2020 Italy | Before vs. during pandemic | not described | 13 ± 8.1 | not described | Longitudinal | 4/8 (medium quality) |

| Corbett et al., 2021 USA | ASD vs. Control, before vs. during lockdown | ASD: 15/46 (33/67) Control: 26/35 (74/26) | ASD: 13.23 ± 1.16 Control: 13.38 ± 1.20 | ADOS severity: 7.13 SD (2.03) | Longitudinal | 5/8 (medium quality) |

| Garcia et al., 2021 USA | Before vs. during pandemic | 1/8 (11/89) | 16.87 ± 1.36 | not described | Longitudinal | 2/8 (low quality) |

| Hosokawa et al., 2021 Japan | ASD vs. Control, before vs. during pandemic | ASD: 21/63 (25/75) Control:: 90/271 (25/75) | 11.06 ± 3.01 | not described | Cross-sectional | 7/10 (medium quality) |

| Jacques et al., 2021 Canada | Before vs. during pandemic | 9/46 (16/82) and one non-binary | 5.75–18 | not described | Cross-sectional | 3/10 (low quality) |

| Kawabe et al., 2020 Japan | ASD vs. Control, before vs. during pandemic | ASD 21/63 (25/75) Control: 90/271 (25/75) | 11.6 ± 3.1 | not described | Cross-sectional | 4/10 (low quality) |

| Lugo-Marín et al., 2021 Spain | Before vs. during lockdown | 5/32 (13/87) | 10.7 ± 3.4 | Level 1: 70.3% Level 2: 29.7% | Longitudinal | 2/8 (low quality) |

| Mete Yesil et al., 2021 Turkey | Before vs. during pandemic | 5/27 (16/84) | 4.97 ± 0.74 | not described | Longitudinal | 1/8 (low quality) |

| Morris et al., 2021 UK | 1st lockdown vs. return to school | not described | 3–12 | not described | Longitudinal | 3/8 (low quality) |

| Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021 Spain | Before vs. during quarantine | 11/36 (23/77) | 7.3 ± 3.4 | not described | Cross-sectional | 3/10 (low quality) |

| Mutluer et al., 2020 Turkey | Before vs. during pandemic | 15/72 (17/83) | 13.96 ± 6 | Mild n: 39/81, 48% Moderate n: 22/81, 27% Severe n: 21/81, 26% | Longitudinal | 3/8 (low quality) |

| Nuñez et al., 2021 Chile | First peak pandemic outbreak | 24/94 (20/80) | 6 (IQR, 4–8) | not described | Cross-sectional | 5/8 (medium quality) |

| Panjwani et al., 2021 USA | Stay at home orders | 47/150 (24/76) | 7.7 (2–17) | not described | Longitudinal | 2/8 (low quality) |

| Polónyiová et al., 2021 Slovakia | ASD vs. Control, first vs. second wave of lockdown | 1st wave: ASD 15/69 (18/82); Control 42/53 (44/56) 2nd wave: ASD 18/53 (25/75); Control 38/44 (46/54) | 1st wave: 7.73 ± 4.73 2nd wave: 9.72 ± 4.48 | majority verbal, without difficulties | Longitudinal | 2/8 (low quality) |

| Rabbani et al., 2021 Bangladesh | Monitored ASD vs. Not-monitored ASD, before vs. during vs. after extended lockdown | 61/ 239 (20/80) | 2–9 years | not described | Longitudinal | 1/8 (low quality) |

| Sergi et al., 2021 Italy | Beginning of lockdown vs. end of lockdown vs. 3 months after resumption of ABA treatment | not described (homogeneous among the sample) | 1.11 ± 0.41 | Level 1: 100% | Longitudinal | 1/8 (low quality) |

| Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021 Israel | Before x during lockdown | 3/22 (12/88) | 5.11 (4.11–6.11) | Level 1 (need support): 9 Level 2 (need substantial support): 8 Level 3 (need very substantial support): 8 | Longitudinal | 2/8 (low quality) |

| Türkoğlu et al., 2020 Turkey | Confinement vs. non-confinement | 8/38 (17.3/ 82.6) | 7.89 (4–17) | not described | Longitudinal | 2/8 (low quality) |

| Türkoğlu et al., 2021 Turkey | Confinement vs. non-confinement | 8/38 (17/ 83) | 7.89 (4–17) | not described | Longitudinal | 4/8 (medium quality) |

| Vasa et al., 2021 USA | Before vs. during pandemic | 50/207 (19/81) | 9.12 ± 3.80 | Single words: n: 49/255, 19.2% Short phrases n: 81/255, 31.8% Fluent: n: 125/255, 49.0% | Longitudinal | 4/8 (medium quality) |

| ASD: 1753/ 6856 (20/80) Control: 321/ 725 (31/69) | mean age: 9.46 y based on 19 studies that presented mean age of patients | cross-sectional: 8 longitudinal: 16 | low quality: 16 (62%) medium quality: 10 (38%) |

The 26 eligible articles and data concerning variables studied (routines, behaviors, and therapies; habits as sleep and eating) are presented below (Table 2). Abilities, including communication, socialization, and autonomy; and screen use and distance learning, are described in Table 3.

Table 2.

Data extraction of the domains routines, behavior, therapies, sleep and feeding in patients with ASD during pandemic

| Article data and country sample | Routines | Behavior | Therapies | Sleep | Feeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amorim et al., 2020 Portugal |

# ASD in which routines were maintained had significantly higher adaptability skills than ASD without routines maintained (7.72 ± 1.84 vs. 5.25 ± 2.75); # ASD without routines significantly had higher levels of anxiety than TD that maintained routines (8.75 ± 0.96 vs. 5.36 ± 2.71) |

# ASD had significantly higher changes in behavior vs. no changes in control children; # Causes for behavior change were: anxiety (n: 13/32, 41.7%); irritability (n: 5/30, 16.7%); obsession (n: 3/27, 11.1%); hostility (n: 2/36, 5.6%); and, impulsivity (n: 1/36, 2.8%); # ASD had significantly negative impact on emotional management vs. positive or no impact on controls (n: 24/42, 55.8% vs. n: 40/55 71.4%) |

|||

| Berard et al., 2021 France |

# Increase in challenging behavior during confinement was reported for most parents (n: 152/236, 64.4%); # Change in stereotyped behaviors was reported by parents (n: 90/218, 41%), there were more worsening than improvement |

# Changes (n = 107/239, 45.5%). There more worsening than improvement | # No change in nutrition behaviors (n: 169, 71.6%), one fifth reported worsening | ||

| Bhat et al., 2021 USA |

# Services disruption had significant negative impact and increased ASD severity, such as impairments in cognition, language, motor function, as well as repetitive behavior severity; # Parents of children with greater repetitive behavior severity significantly reported greater negative impact on their child’s emotional and mental health; # Repetitive behavior severity significantly correlated with potential benefits of online services indicating that parents of children with greater repetitive behavior severity expressed some confidence about benefiting from online services in the future |

# Therapies interrupted due to pandemic: - speech-language (n: 3824/6396, 59.8%) - physical/occupational therapy (n: 2993/6396, 46.8%) - ABA/behavioral therapies (n: 2353/6396, 36.8%) - mental health (n: 809/6396, 21.9%) # Small number of families reported benefits of online services and about equal numbers found it highly beneficial (14%) or not beneficial (19%); |

|||

| Bruni et al., 2021 Italy |

Significance between ASD vs. controls - more controls had bedtime on weekdays during lockdown between 10-11p.m.; - more ASD had risetime on weekdays during lockdown before 7 a.m. and after 10 a.m.; - more controls had risetime on weekdays during lockdown between 8 and 9 a.m.; - more ASD had sleep duration for less than 7 h on weekdays before lockdown; - more controls had sleep duration between 7 and 8 h and 7–8 h on weekdays before lockdown; - more ASD had sleep duration for less than 7 h on weekdays during lockdown # Significance of sleep disorders ASD vs. controls -more ASD had difficulties in falling asleep, restless sleep, snoring /apneas, sleep terrors and daytime sleepiness during lockdown; -more ASD had anxiety at bed time, hypnic jerks, rhythmic movement disorders, more than 2 night awakenings and sleep walking before and during lockdown |

||||

| Bruni et al., 2022 Italy |

# Significance during lockdown: - increased the number of children with latency to sleep more than 30 min on weekdays and more than 60 min on weekends; - reduction in the number of children with sleep duration between 7 and 8 h on weekdays and increase in the number of those who slept 6–7 h on weekends |

||||

| Colizzi et al., 2020 Italy | # Difficulties in managing: child’s meals (n = 148/525, 28.1%); free time (n = 411/526, 78.1%); and, structured activities (n = 394/519, 76.2%) |

# Behavior problems more intense (n: 183/515, 35.5%) and more frequent (n: 216/520, 41.5%); # ASD with vs. without behavioral problems: the 1st were significantly more likely to show symptoms more intensely (2.16 times) and frequently (1.67 times) than the 2nd; # Living with a separated or single parent and being older showed reduction in exhibiting more intense behavioral problems; # ASD that were not receiving indirect school support during pandemic tended to have more intense behavioral problems |

# Child receiving private therapy before pandemic (342/516, 66.2%) # School or private therapist support since pandemic (n: 250/341, 73.3%) # Usefulness of private therapist during COVID-19 (n: 209/331, 63%) # Emergency contact with the child’s neuropsychiatrist required (n: 100/524, 19.1%) |

||

| Corbett et al., 2021 USA |

# Youth ASD when compared to control had: - a tendence to show higher stress on responses to stress questionnaire (p: 0.06); - significantly higher stress according to parent’s perception, also when controlling for experiences with COVID-19; - greater concern regarding COVID-19 illness, symptoms, access to healthcare, and the news; - significantly less 1ry and 2ry control coping (active cognitive strategies); - significantly more disengagement coping (avoidance, denial, and wishful thinking); - significantly more involuntary engagement (i.e., emotional arousal, impulse action, intrusive thoughts, physiological arousal, and rumination); - significantly more involuntary disengagement (i.e., cognitive interference, emotional numbing, escape, and inaction) - significantly more trait anxiety, but not state of anxiety |

||||

| Garcia et al., 2021 USA |

# Significantly greater number of practicing days of physical activity prior pandemic (p = 0.0006); # Significantly higher engagement in activities prior pandemic; (p = 0.007) |

# Going to bed later than usual during pandemic (n: 4/9, 44%) and waking up later (n: 3/4, 75%) | |||

| Hosokawa et al., 2021 Japan | # ASD change of daily routine (n: 34/84, 40.5%) |

# Significancy ASD x control: - ASD more frustrated due to change in schedule because of COVID-19; - ASD less adequate understanding of COVID-19; - Controls spent more time at home since schools were closed; - ASD spent less time studying since schools were closed # Significant stress factors ASD x control: - ASD prohibited from playing outside; - ASD washing hands; - Controls no stress reported # Significant behavioral changes associated with ASD characteristics due to stress: increased restricted and repetitive behavior |

# ASD change on sleep pattern (n: 34/84, 40.5%) | # Significant change in eating habits associated with ASD characteristics due to stress | |

| Jacques et al., 2021 Canada |

# Pandemic facilitating factors: - establishing a routine with child (n: 73/109,67%); - possibility of spending time together (n: 67/109, 61,47%) # Pandemic difficulting factors: - access to electronic devices (n: 61/109, 55.96%) - isolated from our loved ones (n: 60/109, 55.05%) - child focusses on his particular interests (n: 53/109, 48.62%) - child has too much free time (n: 52/109, 47.71%) |

# Children stressful with pandemic (n: 44/56, 78.6%) # Parents identified elevated stress in their child (n: 88/109,80.7%) |

|||

| Kawabe et al., 2020 Japan | # ASD and control children reported stress due to the pandemic, difference between groups were not significant (n: 64/84, 76.2% vs. n: 281/361, 77.8%) | # During pandemic the number of visits to private education or rehabilitation centers in ASD and controls significantly decreased (n = 26/84, 31% vs. n = 280/361, 77.6%) | |||

| Lugo-Marín et al., 2021 Spain | # Anxiety: worse (n: 13/34, 38%); better or no change (n: 23/72, 32%) | # Changes in pharmacological treatment after lockdown onset due to deterioration of clinical status ASD Level 1 (n: 4/26, 15%), ASD Level 2: (n: 3/11, 27%) | # Sleep quality: no changes (n: 13/34, 38%) |

# Weight: no changes (n: 21/35, 60%) # Feeding quality: better (n: 17/35, 49%) |

|

| Mete Yesil et al., 2022 Turkey |

# Daily Routine: worsened (n: 24/32, 77.4%) # Overall activities duration: increased (n: 13/32, 43.3%) # Daily play duration: no change (n: 15/32, 46.9%); increased (n: 13/32, 40.6%) # Reading books duration: no change (n: 12/32, 42.9%); decreased (n: 10/32, 37.5%) # Physical activities duration: no change (n: 12/32, 40.0%); increased (n: 11/32, 36.7%) # Development: continues (n: 15/32, 46.9%); no change (n: 12/32, 37.5%); regression (n: 5/32, 15.6%) |

# Increase or emergence of behavioral problems: - crying attacks (n: 10/32, 31.3%); - restlessness, hyperactivity and screaming (n: 9/32, 28.1%); - clinginess (n: 8/32, 25.0%) |

# Sleep habits: worsened (n: 16/32, 51.6%); no effect (n: 15/32, 48.4%) | # Feeding habits: no effect (n: 22/32, 88%) and improved (n: 7/32, 21.9%) | |

| Morris et al., 2021 UK | # Significant increase in physical activity during the course of the first half-term of 2020/2021 academic year, in comparison to the course of lockdown |

# Self-regulation skills: - during the lockdown: worsened (n: 61/109, 56.5%); no change: (n: 28/109, 25.6%); - during the 1st half term of 2020/2021 academic year: no change (n: 23/54, 42.6%); worsened (n: 21/54, 38.6%); *No significant difference in self-regulation skills between periods # Co-operation skills: - during the lockdown: worsened (n: 54/109, 49.7%); no change (n: 38/109, 35.2%); - during the 1st half term of 2020/2021 academic year: no change (n: 27/54, 50.0%); worsened (n: 18/54, 33.54%); *No significant difference in co-operation skills between periods |

|||

| Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021a Spain |

# Kids missing: - going for a walk or to the park (n: 14/47, 29.8%) - seeing their relatives (grandparents, cousins) (n: 6/47, 12.8%) - attending extracurricular activities such as dancing classes (n: 6/47, 12.8%) - playing with their friends (n: 5/47, 10.6%) - going on trips or hiking (n: 3/47, 6.4%) # Children/adolescents involved in more family routines and activities (n: 19/47, 40.4%) |

# Children were happier and calmer than before quarantine (n: 19/47, 40.4%) # Children were more irritable than before quarantine (n: 11/47, 23.4%) # Children were sadder and more disconnected than before quarantine (n: 4/47, 8.5%) # New stereotypies such as speaking with a louder tone of voice during quarantine (n: 2/47, 4.3%) # New stereotypies such as pulling own ears (n: 3/47, 6.4%) |

# Psychological support before quarantine (n: 108/127, 85.1%) and during quarantine (n: 36/127, 76.6%) | ||

| Mutluer et al., 2020 Turkey |

#Stereotyped behaviors increased significantly (n: 12/87, 14%) #Aggression behavior increased (n: 48/87, 55%) #Tics increased or new tics emerged (n: 23/87, 26%) #Hyperactivity increased significantly (n: 49/87, 56%) #Hypersensitivity increased significantly (n: 12/87, 14%) |

# Parents reported sleep changes (n: 38–87, 44%): - sleep latency increased, not significantly - sleep disturbance increased significantly - sleep duration decreased significantly - sleep quality increased significantly |

# Appetite increased (n: 10/87, 12%) # Appetite decreased (n: 18/87, 21%) Appetite changes: 33%—decreased (n: 18/87, 21%) | ||

| Nuñez et al., 2021 Chile |

# Behavioral difficulties significantly increased in: - frequency or intensity (n: 53/118, 45%); - those who had parent with mental health problems (n: 18/30, 60%); - those who had a family member hospitalized with COVID-19 (n: 17/24, 70.8%) |

||||

| Panjwani et al., 2021 USA |

# Impact on overall behavior: none to small (n: 51/200, 25.6%); moderate to large (n: 148/200, 74.3%) # Distractibility and arguing or stubbornness: increased (n: 140/200 (70%) # Hyperactivity, increased (n: 120/200 (60%) |

||||

| Polónyiová et al., 2022 Slovakia |

# During the first and second lockdown waves: - internalizing maladaptive behavior significantly increased for ASD; - externalizing maladaptive behavior significantly decreased for controls |

# Significant decrease in therapy attendance during 1st and 2st lockdown waves – higher attendance on 2nd wave, but still significantly decreased |

# ASD significantly had later bedtime than controls during 1st lockdown wave # Partial stabilization in sleep routines back to the pre-COVID-19 state during 2st lockdown wave |

||

| Rabbani et al., 2021 Bangladesh |

Pre-lockdown × lockdown × post-lockdown data # Positive impact of the lockdown (improved): - self-injurious behavior (frequency and intensity); - inflexible to change # Negative impact of the lockdown (worsened): - aggressive behavior (how often); - intense interest in objects/parts of objects; - hyperactive; - lack of concentration |

Pre-lockdown vs. lockdown vs. post-lockdown data # Negative impact of lockdown on sleep problems (worsened) |

|||

| Sergi et al, 2021 Italy | # "Sharing and search for the other" significantly increased and improved during lockdown; # Hyperactivity and inattention and, stereotyped behavior and ritualization significantly increased after lockdown and resumption of ABA treatment for 3 months | ||||

| Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021 Israel | # Descriptions of boredom and lack of ability to entertain oneself were common |

# The lack of mean and space for children to expend energy, lead to various levels of psychomotor agitation # A link is made between the absence of speech therapy and increase of repetitive behaviors |

# Many children found it difficult to fall asleep and/or suffered from frequent awakenings and night terrors | # Worsening of food-related unusual behaviors as food selectivity and/or restriction, binge eating and taking more time for a meal | |

| Türkoğlu et al., 2020 Turkey | # significantly more eveningness type during home confinement (Children’s Chronotype Questionnaire) | # significantly increase of autistic symptoms during home confinement (Autism Behavior Checklist) | # Significantly increase in sleep problems during home confinement period—bedtime resistance, delay in falling asleep, sleep duration, night wakings (Children’s Sleep Habits Questionnaire) | ||

| Türkoğlu et al., 2021 Turkey |

# Significantly increase in all Autism Behavior Checklist subscale scores during home confinement- sensory, relating, body and object use, language, and social and self- help # Significantly increase in Affective Reactivity Index- Parent Report (irritability) during home confinement |

||||

| Vasa et al., 2021 USA |

# ASD with increase in psychiatric problems (n = 151/257, 59%) # Worsening of psychiatric problems in those with a previous one (n: 67/164, 41%); # Most common new symptoms were in children with pre-existing psychiatric status: irritability (46/164, 28%), anxiety (20/164, 12%), and disruptive behavior (18/164, 11%) # New symptoms of psychiatric problems in those without previous one (n: 39/136, 29%) # Most common new symptoms were in children without pre-existing psychiatric status: irritability (36/136, 26%), anxiety (30/136, 22%), and disruptive behavior (26/136, 19%) |

# Children with pre-existing psychiatric problems developed new sleep problems symptoms (39/164, 24%) # Children without pre-existing psychiatric problems developed sleep problems (26/136, 19%) |

Table 3.

Data extraction of communication, socialization, and autonomy abilities, screen use, and distance learning in patients with ASD during the pandemic

| Article data and country sample | Communication | Socialization | Autonomy | Screen use | Online/distance learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amorim et al., 2020 Portugal |

# Parents reported negative impact of confinement on learning of their children (n: 20/43, 46.5%) # Remote school classes was the main challenges for children during the quarantine (n: 3/43, 7.1%) |

||||

| Berard et al., 2021 France | # No change (n: 135/239, 57.2%), Progess (n: 68/236, 28.8%) | ||||

| Bhat, 2021 USA |

# The severity of language delays significantly correlated with impact on services disruptions and with the benefits of online services # Greater language delay was significantly associated with less perceived impact on child’s emotional and mental health |

# Child’s school was closed during the pandemic (n: 7.267/9.027, 80.5%) # Disruptions were reported at school (n: 6.960/9.027, 77.1%) and special education (n: 5.118/9.027, 56.7%) |

|||

| Cardy et al., 2021 Canada | # ASD significantly lost more time than controls on social interactions because of screen time |

# Significant increase on screen time use during pandemic, average of 6.9 h # ASD group had significantly higher screen time use before and during the pandemic on weekdays and weekends # Longest screen time durations were reported in this order, watching videos, playing video games and engaging in online learning # Significant higher likelihood of negative perceived impact was associated with increased screen time on weekdays and weekends, and the number of hours playing video games and watching videos on weekends |

# Most benefit for children were online education (n: 69/127, 54%) | ||

| Colizzi et al., 2020 Italy | No greater difficulties in managing child’s autonomies as compared to before COVID-19 (n: 372/524, 71%) |

# School Support: Direct support as, calls, videocalls (n: 342/488, 70.1%) Indirect support as, text messages, homework assignments (n:403/480, 84%) Useful (n: 289/464, 62.3%) |

|||

| Garcia et al., 2021 USA | # Significantly less hours/day watching television prior pandemic; (p = 0.004) | ||||

| Hosokawa et al., 2021 Japan | # ASD did not have fewer opportunities to visit institutions for special needs children (n: 55/78, 70.5%) | ||||

| Jacques et al., 2021 Canada |

# For children and adolescents lack of socialization was an important barrier during pandemic (n: 62/109, 57.1%); # Socialization (with parents, families and peers) was the main source of help when feeling stressful (n: 32/109, 29%); |

# Pandemic facilitating factors:—child being able to take care of himself (n: 57/95, 52.29%) | # Electronics use made children feel good (n: 52/56, 92.9%) | # Pursuing academic goals at a distance was one of the biggest barriers in pandemic (n: 56/109, 51.38%) | |

| Kawabe et al., 2020 Japan |

# Pre-pandemic internet/digital media were significantly longer in ASD than controls (median [quartile]) (3 h/day [2–5] vs. 2 h/day [1.5–3]) # During pandemic: - internet use significantly increased in both groups; - internet use significantly increased more in controls than ASD children (5 h/day [0–2] vs. 2 h/day [1–3]) |

||||

| Lugo-Marín et al., 2021 Spain | # Reducement of social initiations indicated by caregivers (n: 18/36, 49%) was benefic for ASD level 1 children | ||||

| Mete Yesil et al., 2021 Turkey | # Toilet habits: no effect (n: 21/32, 72.4%); worsened (n: 8/32, 27.6%) | # Screen time duration: no change (n: 12/32, 41.4%); increased (n: 9/32, 31.0%); decreased (n: 8/32, 27.6.0%)—not significant | |||

| Morris et al., 2021 UK | # No significant difference in communication skills between lockdown and 1st half term of 2020/2021 academic year |

# Child did not regularly attend school during lockdown (n: 158/176, 89.8%) # Child return to school after summer (September/20) (n: 44/54, 81.5%) # Felt they hadn’t sufficient support from school during the lockdown (n: 98/176, 55,7%) # Felt they had sufficient support from school after return (n: 35/54, 64,8%) |

|||

| Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021 Spain | # More communicative with parents (n: 9/47, 19.2%) |

# Families had more time to teach autonomy skills related to the child independence (55.3%) # Children have participated in family choice making decisions during quarantine (n: 35/47, 74.5%) |

# Development of new strategies such as creating school or academic activities to better manage quarantine with their children (31.9%) # Online classes and sending specific activities for students to work at home (n: 29/47, 61.7%) |

||

| Mutluer et al., 2020 Turkey |

# Deteriorated (n: 25/87, 29%) # Inappropriate speech significantly worsened |

# Receiving special education before pandemic (n: 73/87, 84%) # Discontinuity in children’s special education during pandemic (n: 78/87, 92%) |

|||

|

Rabbani et al., 2021 Bangladesh |

Pre-lockdown vs. lockdown vs. post-lockdown data # Positive Impact of lockdown (improved) - fails to express basic needs # Negative impact of lockdown (worsened) - response to name - avoids eye contact - understands personal care routine |

Pre-lockdown vs. lockdown vs. post-lockdown data # Negative impact of lockdown (worsened) - initiate social interactions - maintain social interactions - use of social smile |

# 186/300, 61.9% were active smartphone users (app users) | ||

| Sergi et al, 2021 Italy | # significant improvement in communication at the end of lockdown when comparing to the beginning, through VABS scale | # Significant improvement in socialization at the end of lockdown when comparing to the beginning, through VABS scale | # Significant improvement in personal autonomy at the end of lockdown when comparing to the beginning, through VABS scale | ||

| Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021 Israel |

# There was a group of children who were able to expand and/or develop their skill set (abundance of free time) # Few examples of an improvement across physical, linguistic and social domains |

Routines

Of the 26 papers added in this work, 10 addressed the routines of children/adolescents with ASD during the pandemic (Amorim et al., 2020; Colizzi et al., 2020; Garcia et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2020). A medium level of evidence was reached in two papers, Colizzi et al., 2020 and Hosokawa et al., 2021. A change in routine was described in eight articles (Amorim et al., 2020; Colizzi et al., 2020; Garcia et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021), and was considered positive in two, since families had more time to spend together (Jacques et al., 2022; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021), but also negative, due to a general worsening in routine according to 77.4% of respondents (Jacques et al., 2022) and, as indicated by 55% of respondents, being isolated from loved ones (Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021).

Regarding changes in routines, the most commonly cited were physical and overall activities; and free time. Two papers observed that patients significantly used to exercise more frequently prior to the pandemic (Garcia et al., 2021; Morris et al., 2021), while another 40% of respondents did not observe changes (Mete Yesil et al., 2022). Considering overall activities, one article found a significantly higher engagement in activities prior to the pandemic (Garcia et al., 2021), which is in contrast with two papers that observed an increase in overall activity duration (43.3%) (Mete Yesil et al., 2022), and more involvement in activities during the pandemic (Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021). Free time also increased for 47.71 to 78.1% of respondents (Colizzi et al., 2020; Jacques et al., 2022).

An interesting finding was reported in one paper that showed patients who had their routines maintained had significantly higher adaptability skills than those without routines. Moreover, ASD patients without routines had significantly higher levels of anxiety than the controls who maintained their routines (Amorim et al., 2020).

Behavior

The domain behavior was addressed in 22 articles, all of which described changes in behavior (Amorim et al., 2020; Berard et al., 2021; Bhat, 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020; Corbett et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022; Kawabe et al., 2020; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Mutluer et al., 2020; Nuñez et al., 2021; Panjwani et al., 2021; Polónyiová et al., 2022; Rabbani et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2020, 2021; Vasa et al., 2021). Medium level of evidence was observed in eight papers (Berard et al., 2021; Bhat, 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020; Corbett et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Nuñez et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2021; Vasa et al., 2021) and the hypothesis of worsening behavior was confirmed by six articles, Bhat, 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020; Corbett et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Nuñez et al., 2021; and Türkoğlu et al., 2021. Most articles (n = 13) observed an resurgence of previous behavioral problems (Berard et al., 2021; Bhat, 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Mutluer et al., 2020; Nuñez et al., 2021; Panjwani et al., 2021; Polónyiová et al., 2022; Sergi et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2020, 2021; Vasa et al., 2021), while others (n = 5) observed the emergence of new behavioral issues (Corbett et al., 2021; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Mutluer et al., 2020; Vasa et al., 2021).

The most common changes were observed in patients’ anxiety (Amorim et al., 2020; Corbett et al., 2021; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Vasa et al., 2021), irritability (Amorim et al., 2020; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2021; Vasa et al., 2021); hyperactivity (Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Mutluer et al., 2020; Panjwani et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021), stress (Corbett et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022; Kawabe et al., 2020), and aggressive behavior (Mutluer et al., 2020; Rabbani et al., 2021) levels. Eight papers (Berard et al., 2021; Bhat, 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Mutluer et al., 2020; Sergi et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021) reported worsening or the emergence of new stereotyped behaviors, including speaking in a louder tone of voice, pulling their ears, and tics (Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Mutluer et al., 2020). Compared with control children, patients showed significantly higher changes in behavior (Amorim et al., 2020; Corbett et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Polónyiová et al., 2022).

Therapies

Five articles described therapies received or missed during the pandemic, such as speech-language, physical/occupational, and behavioral therapies (Bhat, 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Polónyiová et al., 2022). Of those, only two reached the medium evidence quality level (Bhat, 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020). Two authors observed that around 75% of families received some support from their school or private therapists during the pandemic (Colizzi et al., 2020; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021). While another two observed a reduction (Bhat, 2021; Polónyiová et al., 2022). One paper mentioned changing medications due to patients’ symptoms worsening during lockdown (Lugo-Marín et al., 2021).

Sleep

Sleep was addressed in 13 papers (Berard et al., 2021; Bruni et al., 2021, 2022; Garcia et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Mutluer et al., 2020; Polónyiová et al., 2022; Rabbani et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2020; Vasa et al., 2021), all of which reported problems or changes to sleep behaviors, varying from 19 to 51.6%, except for one in which 38% of parents did not report changes in their children (Lugo-Marín et al., 2021). Four articles reached a medium level of evidence (Berard et al., 2021; Bruni et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Vasa et al., 2021) and confirmed our hypothesis regarding increased sleep problems.

Sleep disturbances encompass sleep duration, latency to sleep, bedtime resistance, anxiety at bedtime, and difficulty falling asleep were addressed. Sleeping duration varied among the articles. While some observed a significant decrease (Mutluer et al., 2020) and significant increase (Türkoğlu et al., 2020) in sleep duration, others had significant reduction of children sleeping 7–8 h/day on weekdays and (n: 24/109, 22%) with a significant increase in those sleeping 6–7 h (n: 17/109, 15.6%) on weekends, with no-significant increase in other periods studied, both on weekdays and weekends (Bruni et al., 2022).

When children with ASD were compared with controls, significance was found in ASD children with sleep duration of fewer than 7 h on weekdays before and during lockdown and on controls with sleep duration > 10 h on weekdays during lockdown (Bruni et al., 2021). Increased latency to sleep was reported by two authors (Bruni et al., 2022; Mutluer et al., 2020), significance was reached in the first, where latency to sleep exceeded 30 min on weekdays and was more than 60 min on weekends (Bruni et al., 2022).

Bedtime resistance significantly increased in one paper (Türkoğlu et al., 2021), three others had significantly later bedtimes, 44% and 57.8% of the population studied during the pandemic (Garcia et al., 2021) and during lockdown, respectively (Bruni et al., 2022). Another paper showed that patients with ASD had later bedtimes than controls during the first lockdown wave (Polónyiová et al., 2022). Anxiety at bedtime increased during the lockdown (from 10.8 to 22.5%) (Bruni et al., 2022) and also higher in patients with ASD than in controls (Bruni et al., 2021). Difficulty falling asleep reached significancy in three out of four articles (Bruni et al., 2021, 2022; Türkoğlu et al., 2021) and also more frequent in patients with ASD than in controls (Bruni et al., 2021). Two papers (Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021; Türkoğlu et al., 2020) examined increases in night waking’s, statistical significance was reached in one (Rabbani et al., 2021).

Eating

The findings regarding eating behaviors from six papers (Berard et al., 2021; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Mutluer et al., 2020; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021) varied, and only the first two qualified as medium-quality evidence, Berard et al., 2021 and Hosokawa et al., 2021. In two articles, most parents described no changes in eating habits (Berard et al., 2021; Mete Yesil et al., 2022), while the other four observed some changes such as better eating quality (Lugo-Marín et al., 2021); a decrease in appetite (Mutluer et al., 2020); worse food selectivity and/or restriction, binge eating, and taking more time for a meal (Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021); and changes associated with stress (Hosokawa et al., 2021).

Communication

Communication was investigated in eight papers (Berard et al., 2021; Bhat, 2021; Morris et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Mutluer et al., 2020; Rabbani et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021), two of which reached a medium level of evidence, Berard et al., 2021; and Bhat, 2021. Improved communication skills were observed in two articles (Sergi et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021), while worsening or delay (Bhat, 2021; Mutluer et al., 2020; Rabbani et al., 2021) and no changes were reported in three of the eight (Berard et al., 2021; Morris et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021).

Socialization

Five eligible papers addressed socialization abilities and agreed that the differences observed were due to distancing from school, therapies, or relatives (Cardy et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022; Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Rabbani et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021); however, only one achieved a medium quality level of evidence, Cardy et al., 2021. Two papers identified positive aspects of decreased socialization during the pandemic (Lugo-Marín et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021), while others described the lack of socialization as a barrier during the pandemic (Jacques et al., 2022) or observed negative impacts on the children (Cardy et al., 2021; Rabbani et al., 2021).

Autonomy

Five papers collected information regarding patients’ autonomy during the pandemic; however, only the first cited contained medium-quality evidence (Colizzi et al., 2020; Jacques et al., 2022; Mete Yesil et al., 2022; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021). Three papers described positive changes, such as having more time to teach autonomy skills and displaying more autonomous behaviors (Jacques et al., 2022; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021). In two articles, no changes were observed (Colizzi et al., 2020; Mete Yesil et al., 2022).

Screen Use

Screen use was evaluated in six articles, and only one achieved a medium quality of evidence, Cardy et al., 2021. Three described screen use as increasing during the pandemic (Cardy et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2021; Kawabe et al., 2020). Both patients and controls showed increased screen use during the pandemic; however, ASD patients showed higher screen use than controls before pandemic and the opposite was observed during the pandemic (Kawabe et al., 2020). Other papers showed that patients were active users (Rabbani et al., 2021), while another described electronics as comforting for children during this period (Jacques et al., 2022). One article observed no significant changes in this domain (Mete Yesil et al., 2022).

Online/Distance Learning

Distance learning was examined in nine articles (Amorim et al., 2020; Bhat, 2021; Cardy et al., 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020; Hosokawa et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022; Morris et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Mutluer et al., 2020), and four had a medium quality of evidence, Bhat, 2021; Cardy et al., 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020; and Hosokawa et al., 2021.

Two papers described positive aspects of online learning (Cardy et al., 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020) as the benefit of distance learning for their children or the support received from their school. Others reported negative aspects, such as not having enough support (Morris et al., 2021), that pursuing academic goals at a distance was the main challenge for their kids (Jacques et al., 2022), and the negative impact of confinement on children’s learning (Amorim et al., 2020).

Discussion

In this SR, we aimed to identify the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the main domains affected in children/adolescents with ASD. The data obtained from the studies included in this review were heterogeneous and the results were often conflicting. Regardless, two of our hypotheses were supported, namely that the behavioral issues and sleep disturbances associated with ASD worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Among ASD patients, adherence to routines serves as an effective strategy for avoiding uncertainty, preventing unexpected events, and controlling their environment (Lidstone et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2012). In addition to an intolerance of uncertainty (Boulter et al., 2014), the absence of routine (Lidstone et al., 2014; Rodgers et al., 2012) may exacerbate emotional dysregulation (Vasa et al., 2018), repetitive behaviors, and other aspects of ASD; for example, anxiety, which is particularly common among young patients (Wood et al., 2020) and two times higher in frequency in ASD patients than controls (Cardy et al., 2021; Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021). Corroborating these findings, in this SR, we observed that the behavior domain was the most affected during the pandemic, specifically parents reporting an increase in old behavioral patterns.

We observed that during the pandemic, stress was associated with changes in behavior (Lugo-Marín et al., 2021) and patients were also considered more stressful according to their parents’ perception (Garcia et al., 2021; Jacques et al., 2022). Previous studies (Corbett et al., 2010; Spratt et al., 2012) describe a neurobiological predisposition to stress in ASD patients, which could be an explanation for this finding during the pandemic.

Studies have reported that 26% of ASD patients share a history of trauma and 67% meet the full criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Mehtar & Mukaddes, 2011). Symptoms compatible with PTSD and the COVID-19 pandemic have been observed in ASD patients, suggesting the pandemic is a traumatic event (Mutluer et al., 2020). Among such symptoms are new behavioral difficulties, increased stereotypies, greater distractibility/hyperactivity, worsening social-communication impairments, changes in sleep, and a decline in self-help skills (Peterson et al., 2019). Long-term symptoms may also develop from a decline in adaptive functioning, predominantly in the socialization domain after 6 months to 1 year after the traumatic event (Valenti et al., 2012). Data extracted in this work describe symptoms shared by patients who went through a PTSD event and those who endured the COVID-19 pandemic. This is a matter of concern since the scientific community is still seeking information on how the pandemic may have affected patients with ASD around the world and how long the symptomatology changes due to restrictions imposed by the pandemic will influence patients’ well-being.

Sleep was the second most common domain in which eligible articles reported changes, mostly as worsening. This is of particular interest since sleep is a problem among 65% of patients with ASD (Elrod & Hood, 2015). The reason is a low sensory threshold, resulting in sensory hyperreactivity and patients' over-reaction to stimuli, leading to difficulty falling or staying asleep (Souders et al., 2017). Furthermore, sleep deprivation has long-term deleterious consequences (e.g., cognition) (Gregory & Sadeh, 2012; Touchette et al., 2007) and may influence other symptoms (e.g., behavioral problems) (Hodge et al., 2014).

Social interaction is an important issue for patients with ASD since difficulty with socialization is one of the core symptoms of this condition (Lindor et al., 2019). According to the authors, the suspension of regular schools, special education, and therapies during pandemic may lead to devastating consequences for children's development (Amorim et al., 2020), which might underlie why some families preferred their kids to continue to attend school (Bhat, 2021; Morris et al., 2021), while most opted for confinement.

Despite the difficulties imposed by the pandemic, some families were able to focus the confinement period and time together in stimulating their children in improving abilities such as communication and autonomy, or teaching new tasks (Mumbardó-Adam et al., 2021; Sergi et al., 2021; Tokatly Latzer et al., 2021). Support received from schools, private therapists, and healthcare services throughout the pandemic seem to have helped families with ASD children cope with the restrictions imposed during this period.

Although information concerning patients with ASD during the pandemic is presented in this SR, the design of these studies must be taken into consideration. The majority of the articles referenced in this SR are cross-sectional, observational studies. In these papers, surveys were applied to parents or caregivers, thereby introducing bias and reducing the quality of the evidence collected, which represents a limitation of this work. Additionally, except for one paper, no correlation between the findings and the severity of the ASD diagnosis was made. This should have been considered in all of the papers, since ASD is characterized as a spectrum disorder, and previous studies have established associations between ASD symptom severity and domains such as behavior and sleep (Jang et al., 2011; Lindor et al., 2019; Tudor et al., 2012).

The studies selected for this SR largely describe the short-term impact of pandemic-associated social restrictions on the routines of patients with ASD. Studies that include long-term follow up to establish the real impact suffered by this population.

However, it is important to notice that families that were able to organize their routines and received support had better managed the consequences of the pandemic. Resources such as online psychological support and school support were useful for families and patients to cope with difficulties during the pandemic (Bhat, 2021; Colizzi et al., 2020). Additionally, telemedicine or hybrid service models may enhance interventions and enable more beneficial outcomes for these patients.

In conclusion, taken together, the data available in the literature collectively supports that patients with ASD were affected by the pandemic and this has impacted primarily in the behavior and sleep domains.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Janise Dal Pai, Email: dalpai.janise@edu.pucrs.br.

Magda Lahorgue Nunes, Email: mlnunes@pucrs.br.

References

- American Association Psychiatric. (n.d.). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi-org.ezproxy.frederick.edu/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. 03/10/2022

- Amorim, R., Catarino, S., Miragaia, P., Ferreras, C., Viana, V., & Guardiano, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on children with autism spectrum disorder. Revista de Neurologia, 71(8), 285–291. 10.33588/RN.7108.2020381. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berard M, Rattaz C, Peries M, Loubersac J, Munir K, Baghdadli A. Impact of containment and mitigation measures on children and youth with SD during the COVID-19 pandemic: Report from the ELENA cohort. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021;137:73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A. Analysis of the SPARK study COVID-19 parent survey: Early impact of the pandemic on access to services, child/parent mental health, and benefits of online services. Autism Research. 2021;14(11):2454–2470. doi: 10.1002/aur.2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulter C, Freeston M, South M, Rodgers J. Intolerance of uncertainty as a framework for understanding anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014;44(6):1391–1402. doi: 10.1007/s10803-013-2001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, O., Breda, M., Ferri, R., & Melegari, M. G. (2021). Changes in sleep patterns and disorders in children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorders and autism spectrum disorders during the covid-19 lockdown. Brain Sciences, 11(9). 10.3390/brainsci11091139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bruni O, Melegari MG, Breda M, Cedrone A, Finotti E, Malorgio E, Doria M, Ferri R. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on sleep in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine : JCSM : Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2022;18(1):137–143. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardy RE, Dupuis A, Anagnostou E, Ziolkowski J, Biddiss EA, Monga S, Brian J, Penner M, Kushki A. Characterizing changes in screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures in Canada and its perceived impact on children with autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12(August):1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.702774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, Ciceri ML, Bovo C, Zoccante L. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder: An online parent survey. Brain Sciences. 2020;10(6):341. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10060341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Muscatello RA, Klemencic ME, Schwartzman JM. The impact of COVID-19 on stress, anxiety, and coping in youth with and without autism and their parents. Autism Research. 2021;14(7):1496–1511. doi: 10.1002/aur.2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett BA, Schupp CW, Simon D, Ryan N, Mendoza S. Elevated cortisol during play is associated with age and social engagement in children with autism. Molecular Autism. 2010;1(1):13. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elrod MG, Hood BS. Sleep differences among children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing peers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2015;36(3):166–177. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JM, Lawrence S, Brazendale K, Leahy N, Fukuda D. Brief report: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health behaviors in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Disability and Health Journal. 2021;14(2):101021. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghebreyesus, T. A. (2020). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. WHO Director-General’s Speeches. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020. 03/10/2022

- Gregory AM, Sadeh A. Sleep, emotional and behavioral difficulties in children and adolescents. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2012;16(2):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge D, Carollo TM, Lewin M, Hoffman CD, Sweeney DP. Sleep patterns in children with and without autism spectrum disorders: Developmental comparisons. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35(7):1631–1638. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosokawa R, Kawabe K, Nakachi K, Yoshino A, Horiuchi F, Ueno S Ichi. Behavioral affect in children with autism spectrum disorder during school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: A case-controlled study. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2021;46(4):288–297. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2021.1939350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques C, Saulnier G, Éthier A, Soulières I. Experience of autistic children and their families during the pandemic: From distress to coping strategies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2022;52(8):3626–3638. doi: 10.1007/s10803-021-05233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J, Dixon DR, Tarbox J, Granpeesheh D. Symptom severity and challenging behavior in children with ASD. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(3):1028–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe, K., Hosokawa, R., Nakachi, K., Yoshino, A., Horiuchi, F., & Ueno, S.-I. (2020). Excessive and problematic internet use during the coronavirus disease 2019 school closure: Comparison between Japanese youth with and without autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Public Health | Www.Frontiersin.Org, 8, 609347. 10.3389/fpubh.2020.609347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Levante, A., Petrocchi, S., Bianco, F., Castelli, I., Colombi, C., Keller, R., Narzisi, A., Masi, G., & Lecciso, F. (2021). Psychological impact of Covid-19 outbreak on families of children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing peers: An online survey. Brain Sciences, 11(6). 10.3390/brainsci11060808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lidstone J, Uljarević M, Sullivan J, Rodgers J, McConachie H, Freeston M, Le Couteur A, Prior M, Leekam S. Relations among restricted and repetitive behaviors, anxiety and sensory features in children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2014;8(2):82–92. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2013.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindor E, Sivaratnam C, May T, Stefanac N, Howells K, Rinehart N. Problem behavior in autism spectrum disorder: Considering core symptom severity and accompanying sleep disturbance. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2019;10(JULY):1–10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Marín J, Gisbert-Gustemps L, Setien-Ramos I, Español-Martín G, Ibañez-Jimenez P, Forner-Puntonet M, Arteaga-Henríquez G, Soriano-Día A, Duque-Yemail JD, Ramos-Quiroga JA. COVID-19 pandemic effects in people with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers: Evaluation of social distancing and lockdown impact on mental health and general status. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2021;83:101757. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehtar M, Mukaddes NM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in individuals with diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011;5(1):539–546. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2010.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mete Yesil A, Sencan B, Omercioglu E, Ozmert EN. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with special needs: A descriptive study. Clinical Pediatrics. 2022;61(2):141–149. doi: 10.1177/00099228211050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modesti, P. A., Reboldi, G., Cappuccio, F. P., Agyemang, C., Remuzzi, G., Rapi, S., Perruolo, E., Parati, G., Agostoni, P., Barros, H., Basu, S., Benetos, A., Ceriello, A., Prato, S. Del, Kalyesubula, R., Kilama, M. O., O’Brien, E., Perlini, S., Picano, E., … Okechukwu, O. S. (2016). Panethnic differences in blood pressure in Europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 11(1), 1–21. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews. 2015;4(1):1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris, P. O., Hope, E., Foulsham, T., & Mills, J. P. (2021). Parent-reported social-communication changes in children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 0(0), 1–15. 10.1080/20473869.2021.1936870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mumbardó-Adam, C., Barnet-López, S., & Balboni, G. (2021). How have youth with autism spectrum disorder managed quarantine derived from COVID-19 pandemic? An approach to families perspectives. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 110(Mar). 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mutluer, T., Doenyas, C., & Genc, H. A. (2020). Behavioral implications of the Covid-19 process for autism spectrum disorder, and individuals’ comprehension of and reactions to the pandemic conditions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 561882. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.561882, https://Www.Frontiersin.Org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nuñez A, Le Roy C, Coelho-Medeiros ME, López-Espejo M. Factors affecting the behavior of children with ASD during the first outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurological Sciences. 2021;42(5):1675–1678. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05147-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W. H. (2020). Situation report: World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), 2019(February), 11. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331475/nCoVsitrep11Mar2020-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y%0Ahttps://pandemic.internationalsos.com/2019-ncov/ncov-travel-restrictions-flight-operations-and-screening%0Ahttps://www.who.int/docs/default-source. 03/10/2022

- Panjwani AA, Bailey RL, Kelleher BL. COVID-19 and behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder: Disparities by income and food security status. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2021;115:104002. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Earl RK, Fox EA, Ma R, Haidar G, Pepper M, Berliner L, Wallace AS, Bernier RA. Trauma and autism spectrum disorder: Review, proposed treatment adaptations and future directions. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma. 2019;12(4):529–547. doi: 10.1007/s40653-019-00253-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polónyiová K, Belica I, Celušáková H, Janšáková K, Kopčíková M, Szapuová Ž, Ostatníková D. Comparing the impact of the first and second wave of COVID-19 lockdown on Slovak families with typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2022;26(5):1046–1055. doi: 10.1177/13623613211051480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbani, M., Haque, M., Das Dipal, D., Zarif, M., Iqbal, A., Schwichtenberg, A., Bansal, N., Soron, T., Ahmed, S., & Ahamed, S. (2021). An mCARE study on patterns of risk and resilience for children with ASD in Bangladesh. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 21342. 10.1038/s41598-021-00793-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rodgers J, Glod M, Connolly B, McConachie H. The relationship between anxiety and repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(11):2404–2409. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1531-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sergi L, Mingione E, Ricci MC, Cavallaro A, Russo F, Corrivetti G, Operto FF, Frolli A. Autism, therapy and COVID-19. Pediatric Reports. 2021;13:35–44. doi: 10.3390/pediatric13010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souders, M. C., Zavodny, S., Eriksen, W., Sinko, R., Connell, J., Kerns, C., Schaaf, R., & Pinto-Martin, J. (2017). Sleep in children with autism spectrum disorder. In Current Psychiatry Reports (Vol. 19, Issue 6). Current Medicine Group LLC 1. 10.1007/s11920-017-0782-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spratt EG, Nicholas JS, Brady KT, Carpenter LA, Hatcher CR, Meekins KA, Furlanetto RW, Charles JM. Enhanced cortisol response to stress in children in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(1):75–81. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TokatlyLatzer I, Leitner Y, Karnieli-Miller O. Core experiences of parents of children with autism during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. Autism. 2021;25(4):1047–1059. doi: 10.1177/1362361320984317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touchette E, Petit D, Séguin JR, Boivin M, Tremblay RE, Montplaisir JY. Associations between sleep duration patterns and behavioral/cognitive functioning at school entry. Sleep. 2007;30(9):1213–1219. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor ME, Hoffman CD, Sweeney DP. Children with autism: Sleep problems and symptom severity. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2012;27(4):254–262. doi: 10.1177/1088357612457989. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu S, Uçar HN, Çetin FH, Güler HA, Tezcan ME. The relationship between chronotype, sleep, and autism symptom severity in children with ASD in COVID-19 home confinement period. Chronobiology International. 2020;37(8):1207–1213. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1792485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Türkoğlu, S., Halit, Uçar, N., Fatih, Çetin, H., Hasan, Güler, A., Mustafa, & Tezcan, E. (2021). The relationship between irritability and autism symptoms in children with ASD in COVID-19 home confinement period. Int J Clin Pract, 75, e14742. 10.1111/ijcp.14742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Valenti M, Ciprietti T, Egidio CD, Gabrielli M, Masedu F, Tomassini AR, Sorge G. Adaptive response of children and adolescents with autism to the 2009 earthquake in L’Aquila, Italy. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(6):954–960. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1323-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasa RA, Kreiser NL, Keefer A, Singh V, Mostofsky SH. Relationships between autism spectrum disorder and intolerance of uncertainty. Autism Research. 2018;11(4):636–644. doi: 10.1002/aur.1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasa RA, Singh V, Holingue C, Kalb LG, Jang Y, Keefer A. Psychiatric problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research. 2021;14(10):2113–2119. doi: 10.1002/aur.2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner, R., Russell, S., Saulle, R., Croker, H., Stansfield, C., Packer, J., Nicholls, D., Goddings, A.-L., Bonell, C., Hudson, L., Hope, S., Ward, J., Schwalbe, N., Morgan, A., & Minozzi, S. (2022). School closures during social lockdown and mental health, health behaviors, and well-being among children and adolescents during the first COVID-19 wave. JAMA Pediatrics, 1–10.10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.5840. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wells, G., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., & Peterson, J. (2000). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. 03/10/2022

- Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: Pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2020;27(2):1–4. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Kendall PC, Wood KS, Kerns CM, Seltzer M, Small BJ, Lewin AB, Storch EA. Cognitive behavioral treatments for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(5):473–484. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.