Abstract

The American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes convened a panel to update the previous consensus statements on the management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes in adults, published since 2006 and last updated in 2019. The target audience is the full spectrum of the professional healthcare team providing diabetes care in the USA and Europe. A systematic examination of publications since 2018 informed new recommendations. These include additional focus on social determinants of health, the healthcare system and physical activity behaviours including sleep. There is a greater emphasis on weight management as part of the holistic approach to diabetes management. The results of cardiovascular and kidney outcomes trials involving sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, including assessment of subgroups, inform broader recommendations for cardiorenal protection in people with diabetes at high risk of cardiorenal disease. After a summary listing of consensus recommendations, practical tips for implementation are provided.

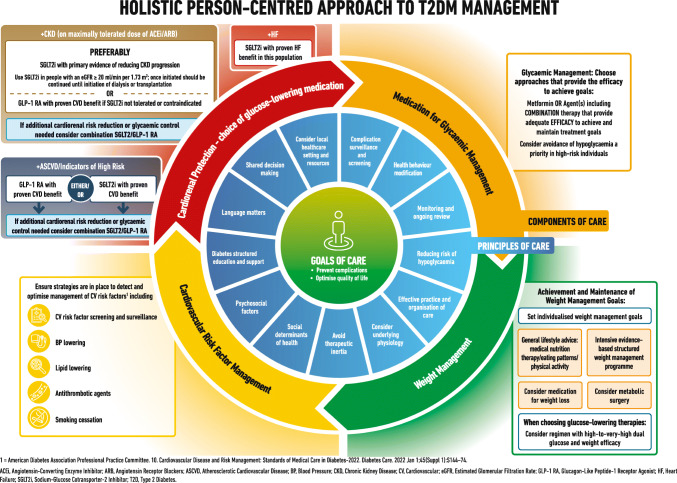

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00125-022-05787-2) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Chronic kidney disease, Glucose-lowering therapy, Guidelines, Heart failure, Holistic care, Person-centred care, Social determinants of health, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Weight management

Introduction

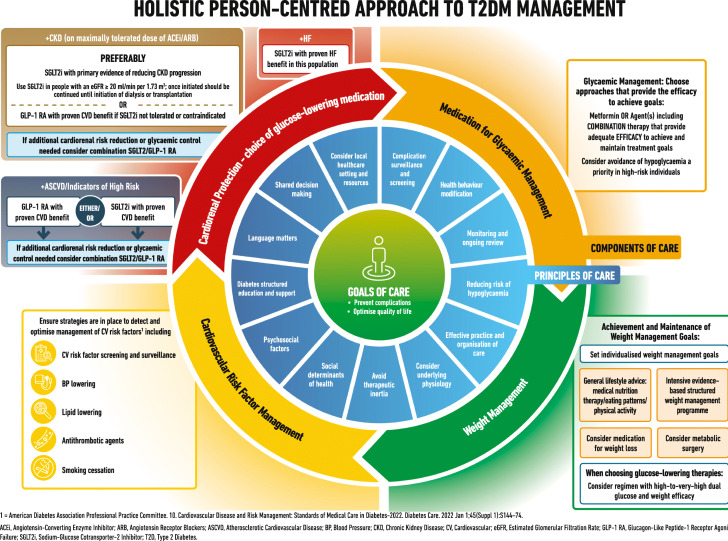

Type 2 diabetes is a chronic complex disease and management requires multifactorial behavioural and pharmacological treatments to prevent or delay complications and maintain quality of life (Fig. 1). This includes management of blood glucose levels, weight, cardiovascular risk factors, comorbidities and complications. This necessitates that care be delivered in an organised and structured way, such as described in the chronic care model, and includes a person-centred approach to enhance engagement in self-care activities [1]. Careful consideration of social determinants of health and the preferences of people living with diabetes must inform individualisation of treatment goals and strategies [2].

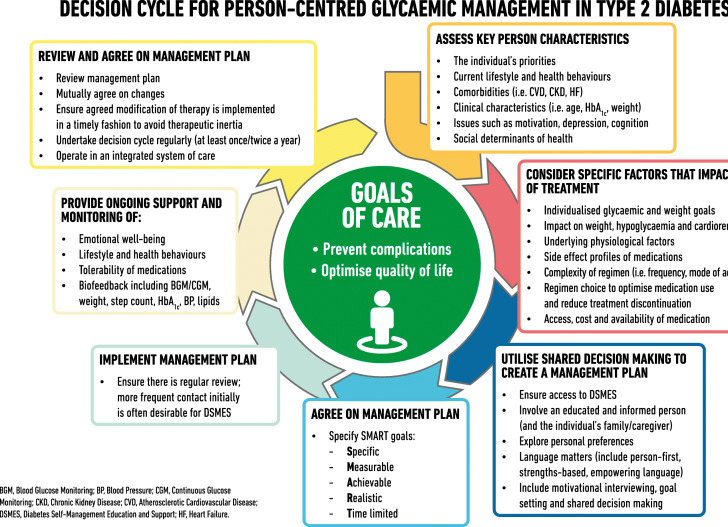

Fig. 1.

Decision cycle for person-centred glycaemic management in type 2 diabetes. Adapted from [5] with permission from Springer Nature, © European Association for the Study of Diabetes and American Diabetes Association, 2018

This consensus report addresses the approaches to management of blood glucose levels in non-pregnant adults with type 2 diabetes. The principles and approach for achieving this are summarised in Fig. 1. These recommendations are not generally applicable to individuals with diabetes due to other causes, for example monogenic diabetes, secondary diabetes and type 1 diabetes, or to children.

Data sources, searches and study selection

The writing group members were appointed by the ADA and EASD. The group largely worked virtually with regular teleconferences from September 2021, a 3 day workshop in January 2022 and a face-to-face 2 day meeting in April 2022. The writing group accepted the 2012 [3], 2015 [4], 2018 [5] and 2019 [6] editions of this consensus report as a starting point. To identify newer evidence, a search was conducted on PubMed for RCTs, systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in English between 28 January 2018 and 13 June 2022; eligible publications examined the effectiveness or safety of pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions in adults with type 2 diabetes. Reference lists in eligible reports were scanned to identify additional relevant articles. Details of the keywords and the search strategy are available at https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/h5rcnxpk8w/2. Papers were grouped according to subject and the authors reviewed this new evidence. Up-to-date meta-analyses evaluating the effects of therapeutic interventions across clinically important subgroup populations were assessed in terms of their credibility using relevant guidance [7, 8]. Evidence appraisal was informed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines on the formulation of clinical practice recommendations [9, 10]. The draft consensus recommendations were evaluated by invited reviewers and presented for public comment. Suggestions were incorporated as deemed appropriate by the authors (see Acknowledgements). Nevertheless, although evidence based with stakeholder input, the recommendations presented herein reflect the values and preferences of the consensus group.

The rationale, importance and context of glucose-lowering treatment

Fundamental aspects of diabetes care include promoting healthy behaviours, through medical nutrition therapy (MNT), physical activity and psychological support, as well as weight management and tobacco/substance abuse counselling as needed. This is often delivered in the context of diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES). The expanding number of glucose-lowering interventions—from behavioural interventions to pharmacological interventions, devices and surgery—and growing information about their benefits and risks provide more options for people with diabetes and providers but complicate decision making. The demonstrated benefits for high-risk individuals with atherosclerotic CVD, heart failure (HF) or chronic kidney disease (CKD) afforded by the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA) and sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) provide important progress in treatment aimed at reducing the progression and burden of diabetes and its complications. These benefits are largely independent of their glucose-lowering effects. These treatments were initially introduced as glucose-lowering agents but are now also prescribed for organ protection. In this consensus report, we summarise a large body of recent evidence for practitioners in the USA and Europe with the aim of simplifying clinical decision making and focusing our efforts on providing holistic person-centred care.

Attaining recommended glycaemic targets yields substantial and enduring reductions in the onset and progression of microvascular complications [11, 12] and early intervention is essential [13]. The greatest absolute risk reduction comes from improving very elevated glycaemic levels, and a more modest reduction results from near normalisation of plasma glucose levels [2, 14]. The impact of glucose control on macrovascular complications is less certain but is supported by multiple meta-analyses and epidemiological studies. Because the benefits of intensive glucose control emerge slowly while the harms can be immediate, people with longer life expectancy have more to gain from early intensive glycaemic management. A reasonable HbA1c target for most non-pregnant adults with sufficient life expectancy to see microvascular benefits (generally ∼10 years) is around 53 mmol/mol (7%) or less [2]. Aiming for a lower HbA1c level than this may have value if it can be achieved safely without significant hypoglycaemia or other adverse treatment effects. A lower target may be reasonable, particularly when using pharmacological agents that are not associated with hypoglycaemic risk. Higher targets can be appropriate in cases of limited life expectancy, advanced complications or poor tolerability or if other factors such as frailty are present. Thus, glycaemic treatment targets should be tailored based on an individual’s preferences and characteristics, including younger age (i.e. age <40 years), risk of complications, frailty and comorbid conditions [2, 15–17], and the impact of these features on the risk of adverse effects of therapy (e.g. hypoglycaemia and weight gain).

Principles of care

Language matters

Communication between people living with type 2 diabetes and healthcare team members is at the core of integrated care, and clinicians must recognise how language matters. Language in diabetes care should be neutral, free of stigma and based on facts; be strengths-based (focus on what is working), respectful and inclusive; encourage collaboration; and be person-centred [18]. People living with diabetes should not be referred to as ‘diabetics’ or described as ‘non-compliant’ or blamed for their health condition.

Diabetes self-management education and support

DSMES is a key intervention, as important to the treatment plan as the selection of pharmacotherapy [19–21]. DSMES is central to establishing and implementing the principles of care (Fig. 1). DSMES programmes usually involve face-to-face contact in group or individual sessions with trained educators, and key components of DSMES are shown in Supplementary Table 1 [19–24]. Given the ever-changing nature of type 2 diabetes, DSMES should be offered on an ongoing basis. Critical junctures when DSMES should be provided include at diagnosis, annually, when complications arise, and during transitions in life and care (Supplementary Table 1) [22].

High-quality evidence has consistently shown that DSMES significantly improves knowledge, glycaemic levels and clinical and psychological outcomes, reduces hospital admissions and all-cause mortality and is cost-effective [22, 25–30]. DSMES is delivered through structured educational programmes provided by trained diabetes care and education specialists (termed DCES in the USA; hereafter referred to as ‘diabetes educators’) that focus particularly on the following: lifestyle behaviours (healthy eating, physical activity and weight management), medication-taking behaviour, self-monitoring when needed, self-efficacy, coping and problem solving.

Importantly, DSMES is tailored to the individual’s context, which includes their beliefs and preferences. DSMES can be provided using multiple approaches and in a variety of settings [20, 31] and it is important for the care team to know how to access local DSMES resources. DSMES supports the psychosocial care of people with diabetes but is not a replacement for referral for mental health services when they are warranted, for example when diabetes distress remains after DSMES. Psychiatric disorders, including disordered eating behaviours, are common, often unrecognised and contribute to poor outcomes in diabetes [32].

The best outcomes from DSMES are achieved through programmes with a theory-based and structured curriculum and with contact time of over 10 h [26]. While online programmes may reinforce learning, a comprehensive approach to education using multiple methods may be more effective [26]. Emerging evidence demonstrates the benefits of telehealth or web-based DSMES programmes [33] and these were used with success during the COVID-19 pandemic [34–36]. Technologies such as mobile apps, simulation tools, digital coaching and digital self-management interventions can be used to deliver DSMES and extend its reach to a broader segment of the population with diabetes and provide comparable or even better outcomes [37]. Greater HbA1c reductions are demonstrated with increased engagement of people with diabetes [35, 38]. However, data from trials of digital strategies to support behaviour change are still preliminary in nature and quite heterogeneous [22, 37].

Individualised and personalised approach

Type 2 diabetes is a very heterogeneous disease with variable age at onset, related degree of obesity, insulin resistance and tendency to develop complications [39, 40]. Providing person-centred care that addresses multimorbidity and is respectful of and responsive to individual preferences and barriers, including the differential costs of therapies, is essential for effective diabetes management [41]. Shared decision making, facilitated by decision aids that show the absolute benefit and risk of alternative treatment options, is a useful strategy to determine the best treatment course for an individual [42–45]. With compelling indications for therapies such as SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA for high-risk individuals with CVD, HF or CKD, shared decision making is essential to contextualise the evidence on benefits, safety and risks. Providers should evaluate the impact of any suggested intervention in the context of cognitive impairment, limited literacy, distinct cultural beliefs and individual fears or health concerns. The healthcare system is an important factor in the implementation, evaluation and development of the personalised approach. Furthermore, social determinants of health—often out of direct control of the individual and potentially representing lifelong risk—contribute to medical and psychosocial outcomes and must be addressed to improve health outcomes. Five social determinants of health areas have been identified: socioeconomic status (education, income and occupation), living and working conditions, multisector domains (e.g. housing, education and criminal justice system), sociocultural context (e.g. shared cultural values, practices and experiences) and sociopolitical context (e.g. societal and political norms that are root cause ideologies and policies underlying health disparities) [46]. More granularity on social determinants of health as they pertain to diabetes is provided in a recent ADA review [47], with a particular focus on the issues faced in the African American population provided in a subsequent report [48]. Environmental, social, behavioural and emotional factors, known as psychosocial factors, also influence living with diabetes and achieving satisfactory medical outcomes and psychological well-being. Thus, these multifaceted domains (heterogeneity across individual characteristics, social determinants of health and psychosocial factors) challenge individuals with diabetes, their families and their providers when attempting to integrate diabetes care into daily life [49].

Current principles of, and approaches to, person-centred care in diabetes (Fig. 1) include assessing key characteristics and preferences to determine individualised treatment goals and strategies. Such characteristics include comorbidities, clinical characteristics and compelling indications for GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i for organ protection [6].

Weight reduction as a targeted intervention

Weight reduction has mostly been seen as a strategy to improve HbA1c and reduce the risk for weight-related complications. However, it was recently suggested that weight loss of 5–15% should be a primary target of management for many people living with type 2 diabetes [50]. A higher magnitude of weight loss confers better outcomes. Weight loss of 5–10% confers metabolic improvement; weight loss of 10–15% or more can have a disease-modifying effect and lead to remission of diabetes [50], defined as normal blood glucose levels for 3 months or more in the absence of pharmacological therapy in a 2021 consensus report [51]. Weight loss may exert benefits that extend beyond glycaemic management to improve risk factors for cardiometabolic disease and quality of life [50].

Glucose management: monitoring

Glycaemic management is primarily assessed with the HbA1c test, which was the measure used in trials demonstrating the benefits of glucose lowering [2, 52]. As with any laboratory test, HbA1c measurement has limitations [2, 52]. There may be discrepancies between HbA1c results and an individual’s true mean blood glucose levels, particularly in certain racial and ethnic groups and in conditions that alter erythrocyte turnover, such as anaemia, end-stage kidney disease (especially with erythropoietin therapy) and pregnancy, or if an HbA1c assay insensitive to haemoglobin variants is used in someone with a haemoglobinopathy. Discrepancies between measured HbA1c levels and measured or reported glucose levels should prompt consideration that one of these may not be reliable [52, 53].

Regular blood glucose monitoring (BGM) may help with self-management and medication adjustment, particularly in individuals taking insulin. BGM plans should be individualised. People with type 2 diabetes and the healthcare team should use the monitoring data in an effective and timely manner. In people with type 2 diabetes not using insulin, routine glucose monitoring is of limited additional clinical benefit while adding burden and cost [54, 55]. However, for some individuals, glucose monitoring can provide insight into the impact of lifestyle and medication management on blood glucose and symptoms, particularly when combined with education and support [53]. Technologies such as intermittently scanned or real-time continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) provide more information and may be useful for people with type 2 diabetes, particularly in those treated with insulin [53, 56].

When using CGM, standardised, single-page glucose reports, such as the ambulatory glucose profile, can be uploaded from CGM devices. They should be considered as standard metrics for all CGM devices and provide visual cues for management opportunities. Time in range is defined as the percentage of time that CGM readings are in the range 3.9–10.0 mmol/l (70–180 mg/dl). Time in range is associated with the risk of microvascular complications and can be used for assessment of glycaemic management [57]. Additionally, time above and below range are useful variables for the evaluation of treatment regimens. Particular attention to minimising the time below range in those with hypoglycaemia unawareness may convey benefit. If using the ambulatory glucose profile to assess glycaemic management, a goal parallel to an HbA1c level of <53 mmol/mol (<7%) for many is time in range of >70%, with additional recommendations to aim for time below range of <4% and time at <3.0 mmol/l (<54 mg/dl) of <1% [2].

Treatment behaviours, persistence and adherence

Suboptimal medication-taking behaviour and low rates of continued medication use, or what is termed ‘persistence to therapy plans’ affects almost half of people with type 2 diabetes, leading to suboptimal glycaemic and CVD risk factor control as well as increased risks of diabetes complications, mortality and hospital admissions and increased healthcare costs [58–62]. Although this consensus report focuses on medication-taking behaviour, the principles are pertinent to all aspects of diabetes care. Multiple factors contribute to inconsistent medication use and treatment discontinuation among people with diabetes, including perceived lack of medication efficacy, fear of hypoglycaemia, lack of access to medication and adverse effects of medication [63]. Focusing on facilitators of adherence, such as social/family/provider support, motivation, education and access to medications/foods, can provide benefits [64]. Observed rates of medication adherence and persistence vary across medication classes and between agents; careful consideration of these differences may help improve outcomes [61]. Ultimately, individual preferences are major factors driving the choice of medications. Even when clinical characteristics suggest the use of a particular medication based on the available evidence from clinical trials, preferences regarding route of administration, injection devices, side effects or cost may prevent use by some individuals [65].

Therapeutic inertia

Therapeutic (or clinical) inertia describes a lack of treatment intensification when targets or goals are not met. It also includes failure to de-intensify management when people are overtreated. The causes of therapeutic inertia are multifactorial, occurring at the levels of the practitioner, person with diabetes and/or healthcare system [66]. Interventions targeting therapeutic inertia have facilitated improvements in glycaemic management and timely insulin intensification [67, 68]. For example, the involvement of multidisciplinary teams that include non-physician providers with authorisation to prescribe (e.g. pharmacists, specialist nurses and advanced practice providers) may reduce therapeutic inertia [69, 70].

Therapeutic options: lifestyle and healthy behaviour, weight management and pharmacotherapy for the treatment of type 2 diabetes

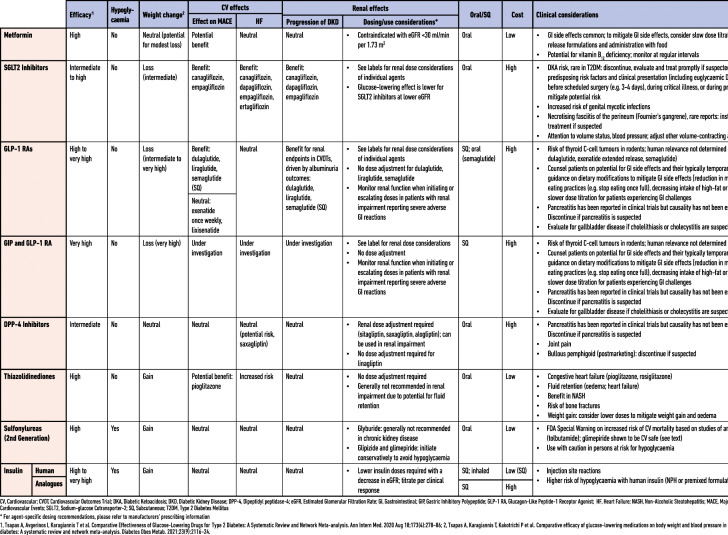

This section summarises the lifestyle and behavioural therapy, weight management interventions and pharmacotherapy that support glycaemic management in people with type 2 diabetes. Specific pharmacological treatment options are summarised in Table 1. Additional details are available in the previous ADA/EASD consensus report and update [5, 6] and the ADA’s 2022 Standards of medical care in diabetes [71].

Table 1.

Medications for lowering glucose, summary of characteristics

Nutrition therapy

Nutrition therapy is integral to diabetes management, with goals of promoting and supporting healthy eating patterns, addressing individual nutrition needs, maintaining the pleasure of eating and providing the person with diabetes with the tools for developing healthy eating [22]. MNT provided by a registered dietitian/registered dietitian nutritionist complements DSMES, can significantly reduce HbA1c and can help prevent, delay and treat comorbidities related to diabetes [19]. Two core dimensions of MNT that can improve glycaemic management include dietary quality and energy restriction.

Dietary quality and eating patterns

There is no single ratio of carbohydrate, proteins and fat intake that is optimal for every person with type 2 diabetes. Instead, individually selected eating patterns that emphasise foods with demonstrated health benefits, minimise foods shown to be harmful and accommodate individual preferences with the goal of identifying healthy dietary habits that are feasible and sustainable are recommended. A net energy deficit that can be maintained is important for weight loss [5, 6, 22, 72–74].

A network analysis comparing trials of nine dietary approaches of >12 weeks’ duration demonstrated reductions in HbA1c from −9 to −5.1 mmol/mol (−0.82% to −0.47%), with all approaches compared with a control diet. Greater glycaemic benefits were seen with the Mediterranean diet and low carbohydrate diet [75]. The greater glycaemic benefits of low carbohydrate diets (<26% of energy) at 3 and 6 months are not evident with longer follow-up [72]. In a systematic review of trials of >6 months’ duration, compared with a low-fat diet, the Mediterranean diet demonstrated greater reductions in body weight and HbA1c levels, delayed the requirement for diabetes medication and provided benefits for cardiovascular health [76, 77]. Similar benefits have been ascribed to vegan and vegetarian diets [78].

There has been increased interest in time-restricted eating and intermittent fasting to improve metabolic variables, although with mixed, and modest, results. In a meta-analysis there were no differences in the effect of intermittent fasting and continuous energy restriction on HbA1c, with intermittent fasting having a modest effect on weight (−1.70 kg) [79]. In a 12 month RCT in adults with type 2 diabetes comparing intermittent energy restriction (2092–2510 kJ [500–600 kcal] diet for 2 non-consecutive days/week followed by the usual diet for 5 days/week) with continuous energy restriction (5021–6276 kJ [1200–1500 kcal] diet for 7 days/week), glycaemic improvements were comparable between the two groups. At 24 months’ follow-up, HbA1c increased in both groups to above baseline [80], while weight loss (−3.9 kg) was maintained in both groups [81]. Fasting may increase the rates of hypoglycaemia in those treated with insulin and sulfonylureas, highlighting the need for individualised education and proactive medication management during significant dietary changes [82].

Non-surgical energy restriction for weight loss

An overall healthy eating plan that results in an energy deficit, in conjunction with medications and/or metabolic surgery as individually appropriate, should be considered to support glycaemic and weight management goals in adults with type 2 diabetes [5, 22]. Structured nutrition and lifestyle programmes may be considered for glycaemic benefit and can be adapted for specific cultural indications [83–87].

The Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) demonstrated greater remission of diabetes with a weight management programme than with usual best practice care in adults with type 2 diabetes within 6 years of diagnosis. The structured, primary care-led intensive weight management programme involved total diet replacement (3452–3569 kJ/day [825–853 kcal/day] for 3–5 months) followed by stepped food reintroduction and structured support for long-term weight loss maintenance. In the whole study population, remission directly varied with degree of weight loss [88]. At the 2 year follow-up, sustained remission correlated with extent of sustained weight loss. In the whole study population, of those maintaining at least 10 kg weight loss, 64% achieved diabetes remission. However, only 24% of the participants in the intervention group maintained at least 10 kg weight loss, highlighting both the potential and the challenges of long-term durability of weight loss [89].

The Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes (Look AHEAD) trial on the longer-term effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention in adults who were overweight/obese with type 2 diabetes showed improvements in diabetes control and complications, depression, physical function and health-related quality of life, sleep apnoea, incontinence, brain structure and healthcare use and costs, with positive impacts on composite indices of multimorbidity, geriatric syndromes and disability-free life-years. This should be balanced against potential negative effects on body composition, bone density and frailty fractures [90, 91]. Although there was no difference in the primary cardiovascular outcome or mortality rate between the intervention and the control groups, post hoc exploratory analyses suggested potential benefits in certain groups (e.g. in those who achieved at least 10% weight loss in the first year of the study). Progressive metabolic benefits were seen with greater degrees of weight loss from >5% to ≥15%, with an overall suggestion that ≥10% weight loss may be required to see benefits for CVD events and mortality rate and other complications such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis [50, 90, 92–95].

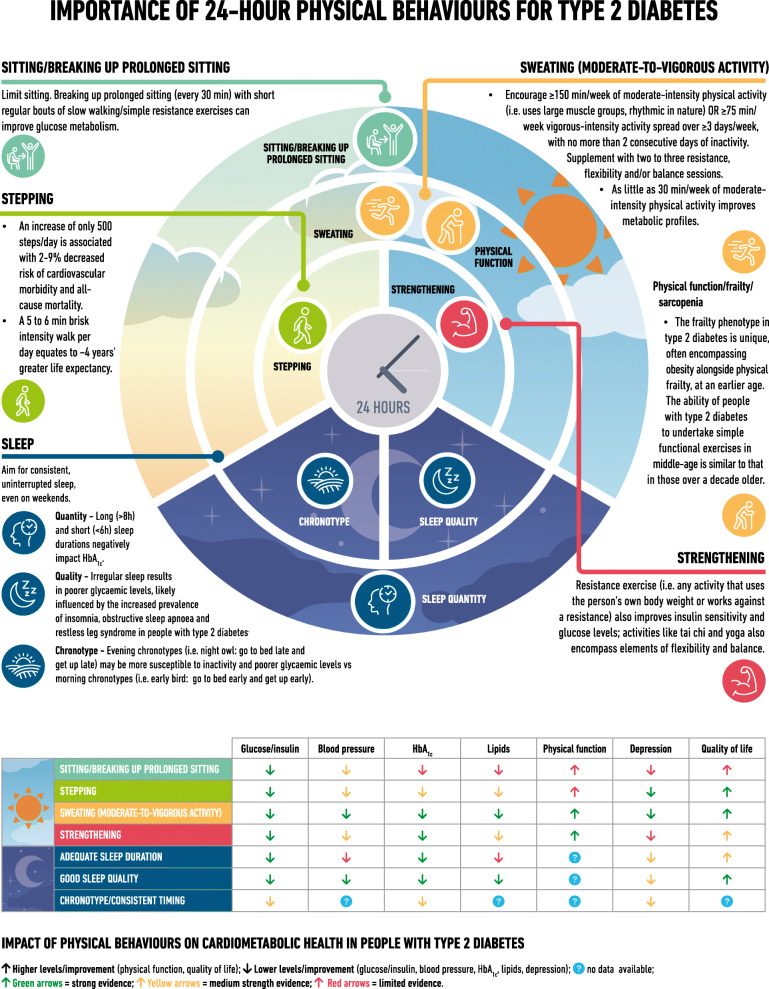

Physical activity behaviours including sleep

Physical activity behaviours significantly impact cardiometabolic health in type 2 diabetes (Fig. 2) [96–117]. Regular aerobic exercise (i.e. involving large muscle groups and rhythmic in nature) improves glycaemic management in adults with type 2 diabetes, resulting in less daily time in hyperglycaemia and reductions of ~7 mmol/mol (~0.6%) in HbA1c [118], and induces clinically significant benefits in cardiorespiratory fitness [101, 110, 119]. These glycaemic effects can be maximised by undertaking activity during the postprandial period and engaging in activities for ≥45 min [101, 120]. Resistance exercise (i.e. using your own body weight or working against a resistance) also improves blood glucose levels, flexibility and balance [101, 110]. This is important given the increased risk of impaired physical function at an earlier age in type 2 diabetes [112].

Fig. 2.

Importance of 24-hour physical behaviours for type 2 diabetes

A wide range of physical activities, including leisure time activities, can significantly reduce HbA1c levels [5, 22, 121, 122]. Even small, regular changes can make a difference to long-term health, with an increase of only 500 steps/day associated with 2–9% decreased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and all-cause mortality rates [105–107]. Beneficial effects are evident across the continuum of human movement, from breaking prolonged sitting with light activity [103] to high-intensity interval training [123].

Sleep

Healthy sleep is considered a key lifestyle component in the management of type 2 diabetes [124], with clinical practice guidelines promoting the importance of sleep hygiene [113]. Sleep disorders are common in type 2 diabetes and cause disturbances in the quantity, quality and timing of sleep and are associated with an increased risk of obesity and impairments in daytime functioning and glucose metabolism [114, 115]. Additionally, obstructive sleep apnoea affects over half of people with type 2 diabetes and its severity is associated with blood glucose levels [115, 116].

The quantity of sleep is known to be associated (in a ‘U’ shaped manner) with health outcomes (e.g. obesity and HbA1c), with both long (>8 h) and short (<6 h) sleep durations having negative impacts [97]. By extending the sleep duration of short sleepers, it is possible to improve insulin sensitivity and reduce energy intake [117, 125]. However, ’catch-up’ weekend sleep alone is not enough to reverse the impact of insufficient sleep [126].

Weight management beyond lifestyle interventions

Medications for weight loss in type 2 diabetes

Weight loss medications are effective adjuncts to lifestyle interventions and healthy behaviours for management of weight and have also been found to improve glucose control in people with diabetes [127].

Newer therapies have demonstrated very high efficacy for weight management in people with type 2 diabetes. In the Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with Obesity (STEP) 2 trial, subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg once a week as an adjunct to a lifestyle intervention performed better than either semaglutide 1.0 mg or placebo, with weight loss of 9.6% (6.2% more than with placebo and 2.7% more than with semaglutide 1.0 mg). More than two thirds of participants in the semaglutide 2.4 mg arm achieved an HbA1c level of ≤48 mmol/mol (≤6.5%) [128]. However, the weight loss was less pronounced than the 14.9% weight loss (vs 2.4% with placebo) seen in the STEP 1 trial in adults with overweight or obesity without diabetes [129]. Tirzepatide, a novel glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 RA, at weekly doses of 5 mg, 10 mg and 15 mg reduced body weight by 15%, 19.5% and 20.9%, respectively, compared with 3.1% with placebo at 72 weeks in people with obesity but without diabetes; however, tirzepatide has not yet been approved for weight management by regulatory authorities [130]. Studies in adults with overweight or obesity suggest that withdrawing treatment with semaglutide leads to increases in body weight [131], highlighting the chronic nature of, and need for, obesity/weight management.

Metabolic surgery

Metabolic surgery should be considered as a treatment option in adults with type 2 diabetes who are appropriate surgical candidates [127, 132]. Metabolic surgery also appears to be effective for diabetes remission in people with type 2 diabetes and a BMI ≥25 kg/m2, although efficacy for both weight loss and diabetes remission appears to vary by surgical type [133–135]. One mixed-effects meta-analysis model has estimated a 43% diabetes remission rate (95% CI 34%, 53%) following metabolic surgery in people with type 2 diabetes and a BMI <30 kg/m2 [136], significantly higher than that achieved with traditional medical management [137]. However, there is a strong association between duration of diabetes and the likelihood of postoperative diabetes remission. People with more recently diagnosed diabetes are more likely to experience remission after metabolic surgery, and the likelihood of remission decreases significantly with duration of diabetes longer than about 5–8 years [138]. Even in people with diabetes who do not achieve postoperative diabetes remission, or relapse after initial remission, metabolic surgery is associated with better metabolic control than medical management [137, 139]. In the Surgical Treatment and Medications Potentially Eradicate Diabetes Efficiently (STAMPEDE) trial, metabolic surgery was also associated with improvements in patient-reported outcomes related to physical health; however, measures of social and psychological quality of life did not improve [140]. It is important to note that many of these estimates of benefit included data from non-randomised studies and compared outcomes with medical treatments for obesity that were less effective than those available today.

Medications for lowering glucose

Cardiorenal-protective glucose-lowering medications

Sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors

The SGLT2i are oral medications that reduce plasma glucose by enhancing urinary excretion of glucose. They have intermediate-to-high glycaemic efficacy, with lower glycaemic efficacy at lower eGFR. However, their scope of use has significantly expanded based on cardiovascular and renal outcomes studies [5, 141]. Cardiorenal outcomes trials have demonstrated their efficacy in reducing the risk of composite major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, hospitalisation for heart failure (HHF) and all-cause mortality and improving renal outcomes in individuals with type 2 diabetes with an established/high risk of CVD. This is discussed in the section on ‘Personalised approach to treatment based on individual characteristics and comorbidities: recommended process for glucose-lowering medication selection’. Evidence supporting their use is summarised in Table 1 [141, 142].

Recent data have increased confidence in the safety of the SGLT2i drug class [141, 142]. Their use is associated with increased risk for mycotic genital infections, which are reported to be typically mild and treatable. While SGLT2i use can increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), the incidence is low, with a modest incremental absolute risk [142]. The SGLT2i cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs) have reported DKA rates of 0.1–0.6% compared with rates of <0.1–0.3% with placebo [143–147], with very low rates in the HF [148–151] and CKD [152, 153] outcomes studies. Risk can be mitigated with education and guidance, including education on signs and symptoms of DKA that should prompt medical attention, and temporary discontinuation of the medication in clinical situations that predispose to ketoacidosis (e.g. during prolonged fasting and acute illness, and perioperatively, i.e. 3 days prior to surgery) [154–158]. The Dapagliflozin in Respiratory Failure in Patients With COVID-19 (DARE-19) RCT demonstrated a low risk of DKA (0.3% vs 0% in dapagliflozin-treated vs placebo-treated participants) with structured monitoring of acid–base balance and kidney function during inpatient use in adults admitted with COVID-19 and at least one cardiometabolic risk factor without evidence of critical illness [159].

While early studies brought attention to several safety areas of interest (acute kidney injury, dehydration, orthostatic hypotension, amputation and fractures) [5, 6], longer-term studies that have prospectively assessed and monitored these events [160, 161] have not seen a significant imbalance in risks. Analyses of SGLT2i outcomes trial data also suggest that people with type 2 diabetes and peripheral arterial disease derive greater absolute outcomes benefits from SGLT2i therapy than those without peripheral arterial disease, and without an increase in risk of major adverse limb events [162]. In post hoc analyses, SGLT2i use has been associated with reduced incidence of serious and non-serious kidney-related adverse events in people with type 2 diabetes and CKD, and greater full recovery from acute kidney injury [163].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

GLP-1 RA augment glucose-dependent insulin secretion and glucagon suppression, decelerate gastric emptying, curb post-meal glycaemic increments and reduce appetite, energy intake and body weight [5, 6, 164]. Beyond improving HbA1c in adults with type 2 diabetes, specific GLP-1 RA have also been approved for reducing risk of MACE in adults with type 2 diabetes with established CVD (dulaglutide, liraglutide and subcutaneous semaglutide) or multiple cardiovascular risk factors (dulaglutide) (Table 1) and for chronic weight management (subcutaneous liraglutide titrated to 3.0 mg once daily; subcutaneous semaglutide titrated to 2.4 mg once weekly). This is discussed in the sections on ‘Medications for weight loss in type 2 diabetes’ and ‘Personalised approach to treatment based on individual characteristics and comorbidities: recommended process for glucose-lowering medication selection’. GLP-1 RA are primarily available as injectable therapies (subcutaneous administration), with one oral GLP-1 RA now available (oral semaglutide) [165].

The recent higher dose GLP-1 RA studies have indicated incremental benefits for glucose and weight at higher doses of GLP-1 RA, with greater proportions of people achieving glycaemic targets and the ability of stepwise dose escalation to improve gastrointestinal tolerability. The Assessment of Weekly AdministRation of LY2189265 (dulaglutide) in Diabetes (AWARD)-11 trial evaluated higher doses of dulaglutide (3.0 mg and 4.5 mg weekly) compared with 1.5 mg weekly, demonstrating superior HbA1c reductions (−19.4 vs −16.8 mmol/mol [−1.77 vs −1.54%], estimated treatment difference [ETD] −2.6 mmol/mol [−0.24%]) and weight loss (−4.6 vs −3.0 kg, ETD −1.6 kg) with dulaglutide 4.5 mg compared with 1.5 mg at 36 weeks in people with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin [166]. Likewise, the SUSTAIN FORTE trial studied higher doses of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide (2.0 mg) compared with the previously approved 1.0 mg dose, reporting a mean change in HbA1c from baseline to week 40 of −23 vs −21 mmol/mol (−2.1 vs −1.9%; ETD −2 mmol/mol [−0.18%]) and weight change of −6.4 kg with semaglutide 2.0 mg and −5.6 kg with semaglutide 1.0 mg (ETD −0.77 kg [95% CI −1.55, 0.01]) [167].

The most common side effects of GLP-1 RA are gastrointestinal in nature (nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea) and tend to occur during initiation and dose escalation and diminish over time. Gradual up-titration is recommended to mitigate gastrointestinal effects [164, 168, 169]. Education should be provided when initiating GLP-1 RA therapy. GLP-1 RA promote a sense of satiety, facilitating reduction in food intake. It is important to help people distinguish between nausea, a negative sensation, and satiety, a positive sensation that supports weight loss. Mindful eating should be encouraged: eating slowly, stopping eating when full and not eating when not hungry. Smaller meals or snacks, decreasing intake of high-fat and spicy foods, moderating alcohol intake and increasing water intake are also recommended. Slower or flexible dose escalations can be considered in the setting of gastrointestinal intolerance [168, 169].

Data from CVOTs on other safety areas of interest (pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer and medullary thyroid cancer) indicate that there is no increase in these risks with GLP-1 RA. GLP-1 RA are contraindicated in people at risk of the rare medullary thyroid cancer [164], that is, those with a history or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, due to thyroid C-cell tumours seen in rodents treated with GLP-1 RA in preclinical studies. Increased retinopathy complications seen in the SUSTAIN 6 CVOT appear attributable to the magnitude and rapidity of HbA1c reductions in individuals with pre-existing diabetic retinopathy and high glycaemic levels, as has been seen in previous studies with insulin [170, 171]. GLP-1 RA are also associated with higher risks of gallbladder and biliary diseases [172].

Other glucose-lowering medications

Metformin

Because of its high efficacy in lowering HbA1c, minimal hypoglycaemia risk when used as monotherapy, weight neutrality with the potential for modest weight loss, good safety profile and low cost, metformin has traditionally been recommended as first-line glucose-lowering therapy for the management of type 2 diabetes. However, there is ongoing acceptance that other approaches may be appropriate. Notably, the benefits of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i for cardiovascular and renal outcomes have been found to be independent of metformin use and thus these agents should be considered in people with established or high risk of CVD, HF or CKD, independent of metformin use [173–175]. Early combination therapy based on the perceived need for additional glycaemic efficacy or cardiorenal protection can be considered at treatment initiation to extend the time to treatment failure [176]. Metformin should not be used in people with an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and dose reduction should be considered when the eGFR is <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2 [177]. Metformin use may result in lower serum vitamin B12 concentrations and worsening of symptoms of neuropathy; therefore, periodic monitoring and supplementation are generally recommended if levels are deficient, particularly in those with anaemia or neuropathy [178, 179].

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4i) are oral medications that inhibit the enzymatic inactivation of endogenous incretin hormones, resulting in glucose-dependent insulin release and a decrease in glucagon secretion. They have a more modest glucose-lowering efficacy and a neutral effect on weight and are well tolerated with minimal risk of hypoglycaemia. CVOTs have demonstrated the cardiovascular safety without cardiovascular risk reduction of four DPP-4i (saxagliptin, alogliptin, sitagliptin and linagliptin) [141]. Reductions in risk of albuminuria progression were noted with linagliptin in the Cardiovascular and Renal Microvascular Outcome Study With Linagliptin (CARMELINA) trial [180]. While generally well tolerated, an increased risk of HHF was found with saxagliptin, which is reflected in its label, and there have been rare reports of arthralgia and hypersensitivity reactions with the DPP-4i class [16].

The high tolerability and modest efficacy of DPP-4i may mean that they are suitable for specific populations and considerations. For example, in a 6 month open-label RCT comparing a DPP-4i (linagliptin) with basal insulin (glargine) in long-term care and skilled nursing facilities, mean daily blood glucose was similar, with fewer hypoglycaemic events with linagliptin compared with insulin [181]. Treatment of inpatient hyperglycaemia with basal insulin plus DPP-4i has been demonstrated to be effective and safe in older adults with type 2 diabetes, with similar mean daily blood glucose but lower glycaemic variability and fewer hypoglycaemic episodes compared with the basal–bolus insulin regimen [182].

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist

In May 2022, the FDA approved tirzepatide, a GIP and GLP-1 RA, for once-weekly subcutaneous administration to improve glucose control in adults with type 2 diabetes as an addition to healthy eating and exercise. In the Phase III clinical trial programme, tirzepatide demonstrated superior glycaemic efficacy to placebo [183, 184], subcutaneous semaglutide 1.0 mg weekly [185], insulin degludec [186] and insulin glargine [187]. For HbA1c, placebo-adjusted reductions of 21 mmol/mol (1.91%), 21 mmol/mol (1.93%) and 23 mmol/mol (2.11%) were demonstrated with tirzepatide 5, 10 and 15 mg weekly, respectively, and mean weight reductions of 7–9.5 kg were seen [183]. Additional metabolic benefits included improvements in liver fat content and reduced visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue volume [188]. Based on meta-analysis findings, tirzepatide was superior to its comparators, including other long-acting GLP-1 RA, in reducing glucose and body weight, but was associated with increased odds for gastrointestinal adverse events, in particular nausea [189]. Similar warnings and precautions are included in the prescribing information for tirzepatide as for agents in the GLP-1 RA class. Additionally, current short-term data from RCTs suggest that tirzepatide does not increase the risk of MACE vs comparators; however, robust data on its long-term cardiovascular profile will be available after completion of the SURPASS-CVOT trial [190]. Tirzepatide has received a positive opinion in the EU.

Sulfonylureas

As per the previous consensus report and update, sulfonylureas are assessed as having high glucose-lowering efficacy, but with a lack of durable effect, and the advantages of being inexpensive and accessible [5, 6]. However, due to their glucose-independent stimulation of insulin secretion, they are associated with an increased risk for hypoglycaemia. Sulfonylureas are also associated with weight gain, which is relatively modest in large cohort studies [191]. Use of sulfonylureas or insulin for early intensive blood glucose control in the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) significantly decreased the risk of microvascular complications, underscoring the importance of early and continued glycaemic management [192]. Adverse cardiovascular outcomes with sulfonylureas in some observational studies have raised concerns, although findings from systematic reviews have found no increase in all-cause mortality rates compared with other active treatments [191]. The incidence of cardiovascular events was comparable in those treated with a sulfonylurea or pioglitazone in the Thiazolidinediones Or Sulfonylureas and Cardiovascular Accidents Intervention Trial (TOSCA.IT) [193], and no difference in the incidence of MACE was found in people at high cardiovascular risk treated with glimepiride or linagliptin [194], a medication whose cardiovascular safety was demonstrated in a population at high cardiovascular and renal risk [195].

Thiazolidinediones

Thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are oral medications that increase insulin sensitivity and are of high glucose-lowering efficacy [5, 6]. TZDs have a high durability of glycaemic response, most likely through a potent effect on preserving beta cell function [196]. In the PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events (PROactive) in adults with type 2 diabetes and macrovascular disease, a reduction in secondary cardiovascular endpoints was seen, although significance was not achieved for the primary outcome [197]. In the Insulin Resistance Intervention After Stroke (IRIS) study in adults without diabetes but with insulin resistance (HOMA-IR >3.0) and recent history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack, there was a lower risk of stroke or myocardial infarction with pioglitazone vs placebo [198, 199]. Beneficial effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) have been seen with pioglitazone [200, 201]. However, these benefits must be balanced against possible side effects of fluid retention and congestive HF [196, 197, 202], weight gain [196–198, 202, 203] and bone fracture [204, 205]. Side effects can be mitigated by using lower doses and combining TZD therapy with other medications (SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA) that promote weight loss and sodium excretion [199, 206].

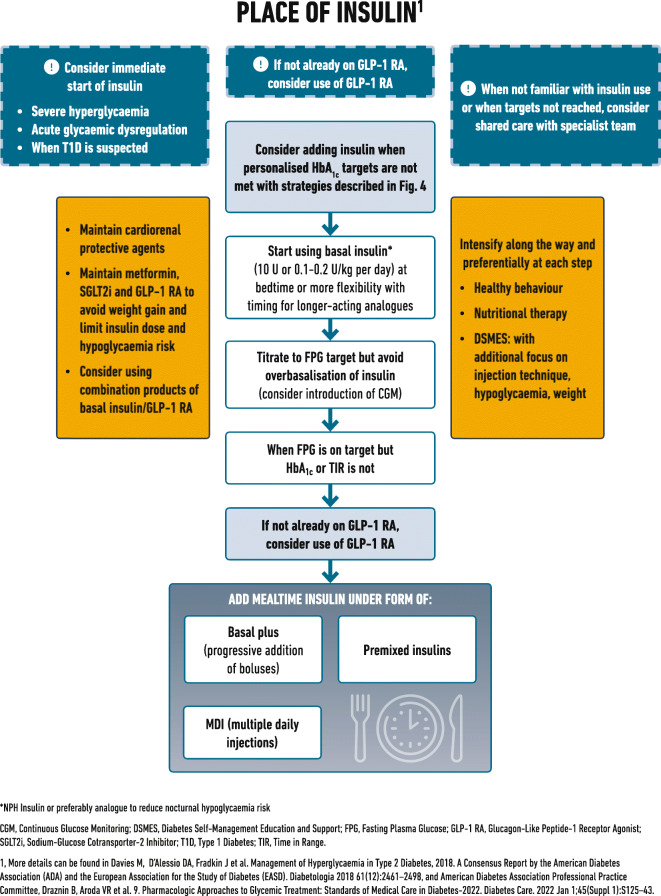

Insulin

The previous consensus report and update provide detailed descriptions of the different insulins [5, 6]. The primary advantage of insulin therapy is that it lowers glucose in a dose-dependent manner and thus can address almost any level of blood glucose. However, its efficacy and safety are largely dependent on the education and support provided to facilitate self-management [5, 6]. Careful consideration should be given to the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of the available insulins, and the matching of the dose and timing to an individual’s physiological requirements. Numerous formulations of insulin are available, with advances in therapy geared toward better mimicking physiological insulin release patterns. Challenges of insulin therapy include weight gain, the need for education and titration for optimal efficacy, risk of hypoglycaemia, the need for regular glucose monitoring, and cost. The approval of biosimilar insulins may improve accessibility at lower treatment costs. Both insulin glargine U100 and insulin degludec have demonstrated cardiovascular safety in dedicated CVOTs [207, 208]. Comprehensive education on self-monitoring of blood glucose, diet, injection technique, self-titration of insulin and prevention and adequate treatment of hypoglycaemia are of utmost importance when initiating and intensifying insulin therapy [5, 6]. Novel formulations and devices including prefilled syringes, auto-injectors and intranasal insufflators are now available to administer glucagon in the setting of severe hypoglycaemia and should be considered for those at risk [209].

Starting doses of basal insulin (NPH or analogue) are estimated based on body weight (0.1–0.2 U/kg per day) and the degree of hyperglycaemia, with individualised titration as needed. A modest but significant reduction in HbA1c and the risk of total and nocturnal hypoglycaemia has been observed for basal insulin analogues vs NPH insulin [210]. Longer-acting basal insulin analogues have a lower risk of hypoglycaemia than earlier generations of basal insulin, although may cost more. Concentrated insulins allow injection of a reduced volume [5]. Cost and access are important considerations and can contribute to treatment discontinuation. Short- and rapid-acting insulin can be added to basal insulin to intensify therapy to address prandial blood glucose levels. Premixed insulins combine basal insulin with mealtime insulin (short- or rapid-acting) in the same vial or pen, retaining the pharmacokinetic properties of the individual components. Premixed insulin may offer convenience for some but reduces treatment flexibility. Rapid-acting insulin analogues are also formulated as premixes, combining mixtures of the insulin with protamine suspension and the rapid-acting insulin. Analogue-based mixtures may be timed in closer proximity to meals. Education on the impact of dietary nutrients on glucose levels to reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia while using mixed insulin is important. Insulins with different routes of administration (inhaled, bolus-only insulin delivery patch pump) are also available [211–213].

Combination glucagon-like peptide-1/insulin therapy

Two fixed-ratio combinations of GLP-1 RA with basal insulin analogues are available: insulin degludec plus liraglutide (IDegLira) and insulin glargine plus lixisenatide (iGlarLixi). The combination of basal insulin with GLP-1 RA results in greater glycaemic lowering efficacy than the mono-components, with less weight gain and lower rates of hypoglycaemia than with intensified insulin regimens, and better gastrointestinal tolerability than with GLP-1 RA alone [214, 215]. In studies of people with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on basal insulin or GLP-1 RA, switching to a fixed-ratio combination of basal insulin and GLP-1 RA demonstrated significant improvements in blood glucose levels and achievement of glycaemic goals with fewer hypoglycaemic events than with basal insulin alone [216–220].

Less commonly used glucose-lowering medications

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors improve glycaemic control by reducing postprandial glycaemic excursions and glycaemic variability and may provide specific benefits in cultures and settings with high carbohydrate consumption or reactive hypoglycaemia [221, 222]. Other glucose-lowering medications (i.e. meglitinides, colesevelam, quick-release bromocriptine and pramlintide) are not commonly used in the USA and most are not licensed in Europe. There was no new evidence that impacts clinical practice.

Comparative efficacy of glucose-lowering agents

In a network meta-analysis of 453 trials assessing glucose-lowering medications from nine drug classes, the greatest reductions in HbA1c were seen with insulin regimens and GLP-1 RA [223]. A network meta-analysis comparing the effects of glucose-lowering therapy on body weight and blood pressure indicates that the greatest efficacy for reducing body weight is seen with subcutaneous semaglutide followed by the other GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i, and the greatest reduction in blood pressure is seen with the SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA classes [224]. As discussed above, the novel GIP and GLP-1 RA tirzepatide was associated with greater glycaemic and weight loss efficacy than semaglutide 1 mg weekly [185].

Combination therapy

The underlying pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes is complex, with multiple contributing abnormalities resulting in a naturally progressive disease and increasing HbA1c over time in many. While traditional recommendations have focused on the stepwise addition of therapy, allowing for clear delineation of positive and negative effects of new drugs, there are data to suggest benefits of combination approaches in diabetes care. Combination therapy has several potential advantages, including (1) increased durability of the glycaemic effect [225–227], addressing therapeutic inertia, (2) simultaneous targeting of the multiple pathophysiological processes characterised by type 2 diabetes, (3) impacts on medication burden, medication-taking behaviour and treatment persistence and (4) complementary clinical benefits (e.g. on glycaemic control, weight and cardiovascular risk profiles) [215, 228–244].

The Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes: A Comparative Effectiveness Study (GRADE) was a multicentre open-label RCT designed to test four different diabetes medication classes in people with type 2 diabetes and compare their ability to achieve and maintain HbA1c levels <53 mmol/mol (<7%). Eligible participants had their metformin therapy optimised and were randomly assigned to receive a sulfonylurea (glimepiride), a DPP-4 inhibitor (sitagliptin), a GLP-1 RA (liraglutide) or basal insulin (insulin glargine), with the primary outcome being the time to metabolic failure, defined as the time to an initial HbA1c level ≥53 mmol/mol (≥7%), if it was confirmed at the next visit to remain above that threshold. Starting with a mean baseline HbA1c level of 58 mmol/mol (7.5%) before the addition of one of the four medications, over 5 years of follow-up, 71% of the cohort reached the primary metabolic outcome. Insulin glargine and liraglutide were significantly, albeit modestly, more effective at achieving and maintaining HbA1c targets. Liraglutide exhibited a lower risk than the pooled effect of the other three medications on a composite cardiovascular outcome comprising MACE, revascularisation, or HF or unstable angina requiring hospitalisation [245, 246].

Personalised approach to treatment based on individual characteristics and comorbidities: recommended process for glucose-lowering medication selection

People with cardiorenal comorbidities

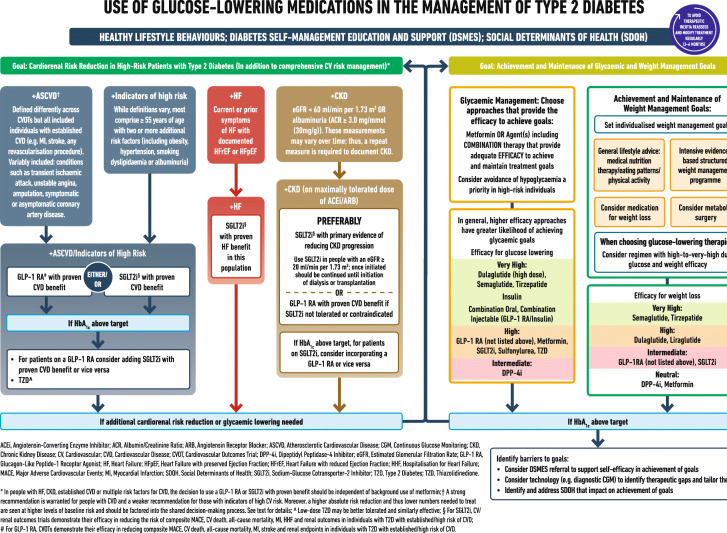

The 2018 ADA/EASD consensus report and 2019 update focused on the consideration of clinically important factors when choosing glucose-lowering therapy. In people with established CVD or with a high risk for CVD, GLP-1 RA were prioritised over SGLT2i. Given their favourable drug class effect in reducing HHF and progression of CKD, SGLT2i were prioritised in people with HF, particularly those with a reduced ejection fraction, or CKD. Since 2019, additional cardiovascular, kidney and HF outcomes trials have been completed, particularly with SGLT2i. In addition, updated meta-analyses have been published that compare subgroup populations based on clinically relevant characteristics, such as presence of CVD, use of background therapy with metformin, stage of CKD, history of HF and age. Collectively, this new evidence was systematically retrieved and appraised to be incorporated into these clinical practice recommendations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Use of glucose-lowering medications in the management of type 2 diabetes

New evidence from cardiorenal outcomes studies since the last consensus report

In the Evaluation of Ertugliflozin Efficacy and Safety CVOT (VERTIS CV), which recruited exclusively people with established CVD and type 2 diabetes, ertugliflozin was similar to placebo with respect to the primary MACE outcome and all key secondary outcomes (including a composite kidney outcome) except for HHF [146]. The Canagliflozin and Renal Endpoints in Diabetes with Established Nephropathy Clinical Evaluation (CREDENCE) study included adults with type 2 diabetes with an eGFR from 30 to <90 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and albuminuria (30–500 mg/mmol [300–5000 mg/g] creatinine) [152]. In CREDENCE, canagliflozin treatment significantly reduced the risk of a composite primary outcome of progression to renal replacement therapy, eGFR of <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2, a doubling of serum creatinine level or death from cardiovascular or kidney causes. The Dapagliflozin And Prevention of Adverse outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA-CKD) trial recruited participants with and without type 2 diabetes with an eGFR of 25–75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and a urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (UACR) of 20–500 mg/mmol [200–5000 mg/g] [153]. Results of the trial demonstrated a clear benefit of dapagliflozin on a composite kidney outcome, on individual kidney-specific outcomes and on cardiovascular death or HHF, both in the overall population and in the subgroup of people with diabetes (68% of participants). In CREDENCE, the SGTL2i was continued until initiation of dialysis or transplantation.

The Effect of Sotagliflozin on Cardiovascular and Renal Events in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes and Moderate Renal Impairment Who Are at Cardiovascular Risk (SCORED) trial assessed sotagliflozin (a dual SGLT1i/SGLT2i, currently not approved for type 2 diabetes in the USA or the EU) in people with type 2 diabetes who had CKD and additional cardiovascular risk factors [147]. Sotagliflozin reduced the composite endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, HHF or urgent visits for HF compared with placebo, but had no effect on the composite kidney endpoint.

SGLT2i have been recently assessed in people with HF in dedicated HF outcome trials. In the Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure and a Reduced Ejection Fraction (EMPEROR-Reduced), empagliflozin reduced the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular mortality or HHF in people with HF and a reduced ejection fraction, irrespective of the presence of type 2 diabetes (50% of participants) [149]. Notably, this beneficial effect of empagliflozin regardless of diabetes status was consistently evident in those with a preserved ejection fraction (>40%), as demonstrated in the Empagliflozin Outcome Trial in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure and a Preserved Ejection Fraction (EMPEROR-Preserved) [151]. Additionally, the Effect of Sotagliflozin on Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Post Worsening Heart Failure (SOLOIST-WHF) trial showed that, in people with type 2 diabetes and worsening HF, sotagliflozin reduced the total number of cardiovascular deaths or hospitalisations or urgent visits for HF compared with placebo regardless of ejection fraction [150]. All these data corroborate the salutary drug class effects of SGLT2i on HF-related outcomes in the setting of HF, irrespective of ejection fraction or diabetes status.

Finally, among GLP-1 RA, the Effect of Efpeglenatide on Cardiovascular Outcomes (AMPLITUDE-O) trial demonstrated a beneficial effect of weekly efpeglenatide on MACE and on a composite kidney outcome (decrease in kidney function or severe albuminuria) [247]. Of note, an exploratory analysis suggested a possible dose–response effect of efpeglenatide on MACE. In a CVOT of an osmotic mini-pump delivering exenatide subcutaneously (ITCA 650) over 3–6 months, ITCA 650 had a neutral effect on MACE compared with placebo over 16 months [248]. Both trials recruited individuals with type 2 diabetes with an established, or high, risk for CVD. Neither efpeglenatide nor ITCA 650 have received marketing authorisation by the FDA or EMA. As mentioned previously, the cardiovascular effects of tirzepatide are being assessed in the ongoing SURPASS-CVOT trial, with dulaglutide as an active comparator.

Evidence is emerging regarding the potential benefits of combined treatment with both an SGLT2i and a GLP-1 RA on outcomes. A post hoc analysis of data from the EXenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering (EXSCEL) has suggested that the combination of exenatide once-weekly (EQW) plus open-label SGLT2i reduces all-cause mortality rates and attenuates the decline in eGFR compared with treatment with EQW alone [244]. Importantly, a prespecified exploratory analysis of the AMPLITUDE-O trial found comparable benefits of GLP-1 RA treatment in participants who were receiving an SGLT2i as background therapy (15% of the total trial population) and those who were not [241].

Results from evidence syntheses

Recent cardiovascular, kidney and HF outcomes trials have been incorporated in updated meta-analyses assessing SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA, both in the overall trial populations and in clinically relevant subgroups. Pairwise meta-analyses of SGLT2i CVOTs verified that SGLT2i reduced MACE, HHF and a composite kidney outcome in the overall population vs placebo [142, 249]. Regarding GLP-1 RA, a meta-analysis of relevant CVOTs demonstrated the favourable effect of GLP-1 RA vs placebo on MACE and its individual components including stroke, HHF and a composite kidney outcome including severe albuminuria [250, 251]. It should be noted, however, that the overall effect estimate for HHF seems to have been driven by CVOTs of albiglutide and efpeglenatide, which are not available for clinical use. Similarly, the overall effect estimate for the composite kidney outcome was most likely driven by the effect of GLP-1 RA on severe albuminuria only and not on hard kidney endpoints. Of note, the beneficial kidney effects of canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin were also evident for hard kidney outcomes including chronic dialysis and kidney transplantation [252]. When individual components of MACE were analysed separately, GLP-1 RA reduced all three outcomes, with a more pronounced effect on stroke followed by cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction [253, 254]. Conversely, SGLT2i, albeit reducing cardiovascular death, had a neutral effect on stroke [142, 255].

The applicability of data to support selection of subgroups has been questioned because of a lack of RCTs focusing on specific populations, such as those using vs those not using metformin. This has been examined in subgroup analyses of recent meta-analyses [6]. It should be noted that findings of subgroup analyses should not be regarded as conclusive, their credibility should always be formally assessed and, ideally, they should be complemented by findings from relevant RCTs [7, 8]. Recently published subgroup analyses have explored the role of background use of metformin as a potential effect modifier of cardiovascular benefit. For SGLT2i, no differences were observed in MACE, cardiovascular death or HHF, major kidney outcomes and mortality rates in those using vs those not using metformin [174]. Further, for GLP-1 RA, no differences were shown in MACE and mortality outcomes [256–258] in metformin users compared with non-users. The similarity of the direction and magnitude of the effect estimates between individual trials, the number of trials that contributed data, mostly to within-trial comparisons, and the statistical analyses implemented support the credibility of the conclusions favouring use of SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA in individuals with compelling indications independent of the use of metformin.

Similarly, other subgroup analyses have explored the role of baseline cardiovascular risk as a potential effect modifier regarding the effect of treatment on MACE, HHF or kidney outcomes. Consistency of findings from between-trial and within-trial comparisons, formal statistical testing verifying the absence of a subgroup effect and the similarity of baseline cardiovascular risk across different cardiovascular risk categories between individual CVOTs despite the use of seemingly different enrolment criteria suggest the benefits of the use of SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA in people with type 2 diabetes and established CVD and in those at high cardiovascular and/or kidney risk [142, 253]. Of note, the level of certainty in this recommendation is higher for the former subgroup, because some CVOTs recruited exclusively people with established CVD, while fewer events were recorded for participants with cardiovascular risk factors only in CVOTs that recruited both subgroup populations. In addition, the definition used for risk factors was not identical among CVOTs. However, in general it comprised age ≥55 years plus two or more additional risk factors (including obesity, hypertension, smoking, dyslipidaemia or albuminuria). Furthermore, in terms of absolute effects, the cardiovascular benefits of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i were less pronounced in people with three or more cardiovascular risk factors than in those with established CVD. This was shown in a network meta-analysis that estimated the absolute effects of treatment with GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i on cardiovascular and kidney outcomes for different categories of baseline cardiovascular risk by combining relative effect estimates with baseline risk estimates [259].

Subgroup meta-analyses based on participants’ kidney function indicated that the salutary effects of SGLT2i on MACE, cardiovascular death or HHF, and a composite kidney outcome (substantial loss of kidney function, end-stage kidney disease or death due to kidney disease) do not significantly differ among subgroups based on eGFR [142, 252]. Moreover, the overall effect on MACE and the kidney outcome seemed to be consistent across the three subgroups (normal urine albumin excretion rate [UACR <3.0 mg/mmol (<30 mg/g)], moderate albuminuria [UACR 3.0–30 mg/mmol (30–300 mg/g)] and severe albuminuria [UACR ≥30 mg/mmol (≥300 mg/g)]) [252]. In addition, no modification of the effect estimates for MACE, cardiovascular death or HHF, and the composite kidney outcome was observed for SGLT2i in subgroup meta-analyses based on history of HF [142]. Regarding GLP-1 RA, a subgroup meta-analysis found that their effect on MACE did not significantly differ between people with an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73m2 and those with an eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 [253]. Moreover, the effect on MACE did not appear to differ between people with lower and higher HbA1c at baseline, both for SGLT2i and for GLP-1 RA [142, 253]. Nevertheless, the conclusions of all subgroup analyses should be regarded with increased caution because of the small number of trials contributing data to within-trial comparisons, heterogeneity between individual trials or lack of formal statistical testing.

Comparative effectiveness data

While CVOTs and pairwise meta-analyses allow inferences about the overall efficacy and safety of novel glucose-lowering therapies, none of them directly compared SGLT2i with GLP-1 RA. However, the comparative effectiveness of the two drug classes has been assessed in three recent network meta-analyses, which found that, in people with type 2 diabetes, SGLT2i were superior to GLP-1 RA in reducing HHF and a composite kidney outcome, while GLP-1 RA seemed more efficacious in reducing the risk of stroke [223, 259, 260]. No important differences between the two drug classes were evident in terms of mortality rates and other cardiovascular outcomes. These conclusions are further supported by observational data from a large population-based cohort study in the USA, which showed that SGLT2i reduced HHF compared with GLP-1 RA in people both with CVD (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.64, 0.79) and without CVD (HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.56, 0.81). Differences between the two drug classes with regard to mortality rates and other cardiovascular outcomes were not clinically important [261].

In terms of differences among individual SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA, choice should be based on country-specific label indications and data on efficacy, safety and outcome benefits considering within-class heterogeneity. No CVOT is available focusing on people with type 2 diabetes who are at low cardiovascular risk. Some inferences about the effect of glucose-lowering medications as primary cardiovascular prevention in populations with low cardiovascular risk can be made from network meta-analyses, suggesting that no agent or drug class has a notable beneficial effect on cardiovascular events in low-risk individuals with diabetes [223, 259].

Additional clinical considerations

Age: older people with diabetes

Type 2 diabetes represents a model of accelerated biological ageing. As such, type 2 diabetes is associated with declines in physical capacity, underpinned by dysfunction within skeletal muscle. The ability of people with type 2 diabetes to undertake simple functional exercises in middle-age has been shown to be like those at least a decade older within the general population. Importantly, this places people living with type 2 diabetes at a high risk of impaired physical function and frailty, which in turn reduces quality of life and increases healthcare use. As such, frailty is increasingly recognised as a major complication of type 2 diabetes and an important target for treatment [112, 262].

Informed decisions regarding treatment of older (>65 years) adults with diabetes are limited by the under-representation of such participants in clinical trials. When older individuals have been studied, analyses from trials such as Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) suggested that more frail individuals have worse outcomes and benefit less from intensive control of blood glucose levels and blood pressure [263]. However, our confidence in selecting medications to improve outcomes has improved, in part because of regulatory requirements to include older people in trials to determine the efficacy and safety of new drugs for diabetes [264, 265]. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 11 large outcomes trials found that, in those aged 65 years or older, the cardiovascular and/or kidney outcomes benefits of GLP-1 RA or SGLT2i therapy were consistent with the effects seen in the overall trial population [266]. Therefore, recommendations for the selection of medications to improve cardiovascular and kidney outcomes do not differ for older people. Older age should not be an obstacle to treatment of individuals with established or high risk for CVD. However, medication choices for people who are frail or who have multiple comorbidities may require modification for safety and tolerability. People with diabetes should also understand and be able to appropriately modify use of their prescribed medications during times of illness. Frailty is associated with poorer prognosis, and some attenuation of benefit from intensive glucose-lowering and blood pressure-lowering treatments has been demonstrated in frail individuals [263]. Consideration of de-prescribing medication to avoid unnecessary medication or medication associated with harm, such as hypoglycaemia and hypotension, is important in such populations.

Age: younger people with diabetes

Rates of impaired glucose tolerance and/or impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes have increased significantly in the adolescent and young adult population, in concert with increases in obesity [267]. It is estimated that one in five adolescents and one in four young adults now have impaired glucose tolerance and/or impaired fasting glucose in the USA, which in turn increases the risks of progression to type 2 diabetes, CKD and cardiovascular complications [267]. Minority populations are particularly affected, with half or more of newly diagnosed cases of type 2 diabetes in childhood and adolescence occurring in Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, Asian/Pacific Islander and American Indian populations [268]. Affected young people have a more rapid deterioration in blood glucose levels, an attenuated response to diabetes medication and more rapid development of diabetes complications [269–273]. Early disease onset, higher levels of hyperglycaemia, and the multiple cardiometabolic risk factors found in adolescents and young adults with impaired glucose tolerance and/or impaired fasting glucose and diabetes all contribute to an increase in risk of adverse outcomes [267]. Most children and adolescents who develop type 2 diabetes will have microvascular complications by young adulthood [274]; in addition, a recently identified 25% increase in the risks of hyperglycaemic crises, acute myocardial infarction, stroke and lower extremity amputation over a 5 year period was most notable in people with diabetes aged 18–44 years [275]. Younger people with type 2 diabetes should be considered at very high risk for complications and treated correspondingly. Early use of combination therapy may be considered, as the Vildagliptin Efficacy in combination with metfoRmIn for earlY treatment of type 2 diabetes (VERIFY) trial findings suggest that this approach provides superior and more durable effects on blood glucose levels than metformin monotherapy in people with both early-onset (age <40 years) and later-onset diabetes [276]. Most of the evidence for health behaviour interventions, glucose-lowering approaches and the effectiveness of medications to improve cardiovascular and kidney outcomes in younger people with diabetes is poorly understood because of the very limited enrolment of this group in completed trials [15]. Beyond the scope of this statement, there are data emerging on the use of GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i in children that suggest glycaemic benefit; however, the durability of this effect and any impact on cardiorenal outcomes in children and young adults remain unknown.

Race and ethnicity

Although specific populations are disproportionately affected by diabetes, they are consistently under-represented in outcomes and other trials. A meta-analysis of six large cardiovascular and kidney outcomes trials found that non-White participants had higher rates of cardiovascular and other comorbidities than the White cohort but comprised only about 21% of the overall enrolled trial populations. Importantly, both non-White and White subgroups had significant reductions in the risk of cardiovascular death or HHF with SGLT2i therapy compared with placebo (OR 0.66 and 0.82, respectively) [277]. The increased burden of complications in under-represented populations with diabetes should be factored into personalised treatment plans, and beneficial medications should be used irrespective of race or ethnicity. Ongoing and future trials should recruit to be representative of the overall population of people with diabetes, so that the effects of interventions in understudied subgroups may be better ascertained [278, 279].

Sex differences

In women with reproductive potential, the use of highly effective contraception should be ensured, such as long-acting reversible contraception (intrauterine device or progesterone implant), prior to prescribing medications that may adversely affect a fetus. Diabetes significantly increases the risk of cardiovascular complications in both sexes, and CVD causes most hospitalisations and deaths in women and men with diabetes [280, 281]. In the general population, women are at lower risk for cardiovascular events than men of the same age; however, this vascular protection or advantage is reduced in women who develop type 2 diabetes [282, 283]. In fact, the increase in relative risk of CVD due to type 2 diabetes is greater in women than in men [284–286]. Despite this, women have been under-represented in recent CVOTs in diabetes, comprising between 28.5% and 35.8% of participants [287]. This analysis also described differing patterns of cardiovascular complications in women compared with men, and poorer management of cardiovascular risk factors in women [287]. Within-trial analyses and meta-analyses suggest that there are likely no between-sex differences in outcomes achieved with SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA therapy [288, 289]. Continued efforts should be made to enrol women in outcomes trials and to identify and address modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in women with diabetes.

Obesity and weight-related comorbidities, particularly NAFLD and NASH

The care of people with diabetes who have weight-related comorbidities such as NAFLD, HF with preserved ejection fraction or obstructive sleep apnoea should include strategies intended to result in weight loss. People with type 2 diabetes frequently have NAFLD and are at increased risk for progression to more severe stages of liver disease, including NASH, hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis [290]. The management of type 2 diabetes in people with NASH should include lifestyle modification with a goal of weight loss, including strong consideration of medical and/or surgical approaches to weight loss in those at higher risk of hepatic fibrosis [291]. Pioglitazone, GLP-1 RA therapy and metabolic surgery have all been shown to reduce NASH activity; pioglitazone therapy and metabolic surgery may also improve hepatic fibrosis [188, 292–298].

Although not licensed for this purpose, it has therefore been suggested that people with type 2 diabetes at intermediate to high risk of fibrosis should be considered for treatment with pioglitazone and/or a GLP-1 RA with evidence of benefit [291, 299]. Although SGLT2i therapy has also been shown to reduce elevated levels of liver enzymes and hepatic fat content in people with NAFLD, at this time there is less evidence to support use of this class of drug as treatment for NASH [300–302]. NAFLD, and in particular NASH, is also associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular complications; therefore, people with NAFLD should have their cardiovascular risk factors assessed and managed to minimise this risk [303].

SGLT2i have been shown to reduce incident obstructive sleep apnoea in two SGLT2i CVOTs based on adverse event reporting [304, 305]. However, it is not clear that the data collected on incident obstructive sleep apnoea in these trials were complete, or that the benefit is mediated through changes in weight.

Consensus recommendations

All people with type 2 diabetes should be offered access to ongoing DSMES programmes.

Providers and healthcare systems should prioritise the delivery of person-centred care.

Optimising medication adherence should be specifically considered when selecting glucose-lowering medications.

MNT focused on identifying healthy dietary habits that are feasible and sustainable is recommended in support of reaching metabolic and weight goals.

- Physical activity improves glycaemic control and should be an essential component of type 2 diabetes management.

- Adults with type 2 diabetes should engage in physical activity regularly (>150 min/week of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic activity) and be encouraged to reduce sedentary time and break up sitting time with frequent activity breaks.

- Aerobic activity should be supplemented with two to three resistance, flexibility and/or balance training sessions/week. Balance training sessions are particularly encouraged for older individuals or those with limited mobility/poor physical function.