Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic (and its aftermath) highlights a critical need to communicate health information effectively to the global public. Given that subtle differences in information framing can have meaningful effects on behavior, behavioral science research highlights a pressing question: Is it more effective to frame COVID-19 health messages in terms of potential losses (e.g., “If you do not practice these steps, you can endanger yourself and others”) or potential gains (e.g., “If you practice these steps, you can protect yourself and others”)? Collecting data in 48 languages from 15,929 participants in 84 countries, we experimentally tested the effects of message framing on COVID-19-related judgments, intentions, and feelings. Loss- (vs. gain-) framed messages increased self-reported anxiety among participants cross-nationally with little-to-no impact on policy attitudes, behavioral intentions, or information seeking relevant to pandemic risks. These results were consistent across 84 countries, three variations of the message framing wording, and 560 data processing and analytic choices. Thus, results provide an empirical answer to a global communication question and highlight the emotional toll of loss-framed messages. Critically, this work demonstrates the importance of considering unintended affective consequences when evaluating nudge-style interventions.

Keywords: Message framing, Anxiety, Nudges, COVID-19

Managing the COVID-19 pandemic (and its aftermath) hinges in part on effectively communicating health messages to the global public. One critical question is how to frame such messages, given widespread evidence from psychology and related fields that the way in which information is framed can have meaningful effects on behavior, even when the core information is essentially the same across distinct frames (for reviews, see Gallagher & Updegraff, 2012; Rothman et al., 2020). Indeed, in their widely cited review recommending social and behavioral science applications for reducing the spread of COVID-19, Van Bavel et al. (2020) highlighted this very question: “Research is needed to determine whether a more positive [vs. negative] frame could educate the public and relieve negative emotions while increasing public health behaviors” (p. 462). More generally, Sunstein and Thaler (2003, p. 1182) have long argued that “In order to be effective, any effort to inform people must be rooted in an understanding of how people actually think. Presentation makes a great deal of difference: The behavioral consequences of otherwise identical pieces of information depend on how they are framed.” In their view, framing constitutes a potentially powerful nudge—i.e., a way of altering people’s behavior in a predictable way without changing the underlying incentives (Thaler & Sunstein, 2009; see also de Bruin & Bostrom, 2013; Downs, 2014).

In the case of COVID-19 health messaging, communicators could emphasize either (a) the benefits of compliance (i.e., gain framing) or (b) the costs of non-compliance (i.e., loss framing) with recommended actions. For example, as depicted in Fig. 1, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website (perhaps unintentionally) framed messages in terms of gains, asking the public to: “Wear a mask. Save lives” (CDC, 2021). However, an alternative loss framing might have said: “If you do not wear a mask, lives may be lost.”

Fig. 1.

An example of a public service announcement from the CDC. This public service announcement used gain-framed messages to encourage mask-wearing (image from May, 2021)

Given the ability of news media, national and international health organizations, and political leaders to reach wide audiences, message framing effects could save a substantial number of lives with limited implementation costs. With this possibility in mind, we conducted an experiment to test the effect of loss- versus gain-framing of COVID-19-related public health messages on behavioral intentions, policy attitudes, and information seeking among participants in 84 countries during the pandemic. Moreover, we sought to assess the potential benefit of changes on those outcomes against the potential emotional costs that loss (vs. gain) framing might elicit.1 Prior studies suggest that loss frames (versus gain frames) are associated with relatively more global negative than positive affect (Nabi et al., 2020; Gosling et al., 2020). Here, we chose to examine whether loss (versus gain) framing would increase participants’ anxiety, in particular, given that framing effects on anxiety have received little to no empirical attention and that anxiety has the potential to trigger significant health burdens.

Anxiety, “an emotion characterized by feelings of tension, worried thoughts, and physical changes like increased blood pressure” (American Psychological Association, 2021), may take the form of a temporary state, a chronic trait-like tendency, or a clinical disorder.2 Anxiety has been linked with leading causes of human morbidity and mortality. For example, heightened anxiety is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease mortality and morbidity (e.g., heart disease, stroke, and heart failure; Levine et al., 2021). It has also been linked to increased reactivity to losses (Hartley & Phelps, 2012; Xu et al., 2013) and increased stress hormone secretion (i.e., cortisol), which, when chronic, diminishes immune function and complicates individuals’ ability to cope with stress (for review, Taylor, 2021). Moreover, the effect of anxiety on stress hormone secretion may worsen with age (ó Hartaigh et al., 2012; Otte et al., 2005), potentially putting elderly individuals who already face heightened risks from COVID-19 in an even more vulnerable position. While the anxiety triggered by exposure to public health messages is likely mild compared to the levels associated with a clinical disorder, any potential behavioral benefit from message framing must still be weighed against a potential emotional cost (intended or otherwise).

Given the global nature of the pandemic, it is critical to assess the generalizability of message framing effects on a global scale. Traditionally, psychological research on human behavior includes sample populations in western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic societies (i.e., WEIRD societies; Henrich et al., 2010a, 2010b). However, extrapolating from studies conducted in only a single location may miss meaningful cross-regional variation in effects. Consequently, this can lead to incomplete—and even potentially detrimental—policy recommendations. Thus, rather than assume generalization from a single population, research that aims to inform global policy recommendations during COVID-19 should incorporate a global sample (c.f., Bauer, 2019).

Method

We launched a global participant recruitment effort between April and September 2020, collecting data in 48 languages from 15,929 participants in 84 countries.3 Participants were recruited by (1) research groups affiliated with the Psychological Science Accelerator (PSA; Moshontz et al., 2018) and (2) semi-representative research panels. The present experiment was bundled with another experiment—also conducted in collaboration with the PSA, but led by an independent research group—that assessed the relative effects of autonomy-supportive messages vs. controlling messages on motivation and behavioral intentions relevant to COVID-19. Participants completed both experiments in a randomized order after completing a pre-study survey that included demographic questions (for full wording of all questions from the pre-study survey and relevant descriptive statistics, see Table 1). The order of the study (first vs. second) did not have a main effect on any of the dependent variables, although there was one higher-order interaction with self-reported anxiety (described below). A third experiment investigated the effect of cognitive reappraisal, an emotion regulation strategy, and was conducted concurrently by the PSA with a different sample of participants (Wang et al., 2021).

Table 1.

Questions, response format, and relevant descriptive statistics of measures in the pre-study survey

| Question text | Response format | Relevant descriptives |

|---|---|---|

| In the past seven days, how many times did you go out of your home or residence? | Open numeric | M = 7.42, SD = 7.1 |

| In the past seven days, what were your reasons for going out of your home or residence? Please check all that apply. | Multiple choice | Work: 41%; Health visits: 16%; Groceries: 70% Non-essential goods: 21%; Visiting family and friends: 34%; Outdoor physical activity: 32%; Animal care: 12%; Other: 15 |

| Of the places that you visited in the past seven days, how many would you characterize as being crowded? Crowded here means that you could not maintain a 6-feet/2-meter distance between you and other people. | Numeric (1 = None of them; 6 = All of them) | M = 3.32, SD = 1.26 |

| When you have gone out in the past seven days, how often have you worn a mask for your face? | Numeric (1 = Never; 6 = All the time) | M = 4.44, SD = 1.64 |

| If you wore a mask when going outside your home, what type did you most frequently wear? | Forced choice | Cloth mask: 39%; Surgical mask: 33%; N95/FFP1/P100/other respirator: 6%; Homemade/makeshift mask: 4%; Unsure: 2%; None: 13%; Not applicable: 4% |

| In the past seven days, where have you most frequently directed your coughs and sneezes? | Forced choice | Air: 4%; Palms: 8%; Tissue/handkerchief: 10%; Elbow: 42%; Mask: 9%; Not applicable: 28% |

| Different cities and regions around the world are placing different levels of restrictions on their residents to slow the spread of COVID-19. Which of these options best describes the restrictions that are currently in place in your area? | Forced choice | Total lockdown: 12%; Partial lockdown: 60%; No lockdown: 28% |

| How difficult do you find the level of restrictions in your area to manage? | Numeric (1 = Not at all difficult, 5 = Extremely difficult) | M = 2.24, SD = 1.12 |

| I live in a country where the central government provides honest and helpful guidance about issues related to public health. | Numeric (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) | M = 4.67, SD = 1.91 |

| I live in a city or region where the local government provides honest and helpful guidance about issues related to public health. | Numeric (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree) | M = 4.74, SD = 1.78 |

| To what degree are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the current policies of your national government to slow the spread of COVID-19? | Numeric (1 = Extremely dissatisfied, 7 = Extremely satisfied) | M = 4.24, SD = 1.72 |

| Have you ever been tested for COVID-19? | Forced choice | Yes, tested positive: 1%; Yes, tested negative, but diagnosed positive: 1%; Yes, tested negative, not diagnosed positive: 7%; No, diagnosed positive: 3%; No: 88% |

| Are you currently self-isolating due to flu-like or cold-like symptoms? | Forced choice | Yes: 5%; No: 95% |

| To the best of your knowledge, have you been exposed to anyone known or suspected of having COVID-19 within the past two weeks? | Forced choice | Yes: 7%; No: 93% |

| How confident are you about your understanding of how COVID-19 spreads? | Numeric (1 = Not at all confident, 5 = Extremely confident) | M = 3.6, SD = 1 |

| Based on your current daily routine, how confident are you that you can prevent yourself from catching or spreading COVID-19? | Numeric (1 = Not at all confident, 5 = Extremely confident) | M = 3.32, SD = 1.05 |

| How worried are you that your physical well-being will get worse over the next two weeks? | Numeric (1 = Not at all worried, 5 = Extremely worried) | M = 1.99, SD = 1.08 |

| How worried are you that your emotional well-being will get worse over the next two weeks? | Numeric (1 = Not at all worried, 5 = Extremely worried) | M = 2.23, SD = 1.24 |

| How did you receive this survey? | Forced choice | Research agency: 20%; University pool: 29%; Friends or family: 17%; Social media: 27%; Other: 7% |

| How would you describe your current employment? | Forced choice | Employed with current income: 46%; Employed without current income: 6%; Not employed with current income: 15%; Not employed without current income: 32% |

| If you are employed, would you describe your current employment as providing an essential service during the pandemic? Essential services include roles for which interruptions would pose a danger to community health and safety. | Forced choice | Yes: 21%; No: 36%; Not employed: 43% |

| How old are you, in years? | Open numeric | M = 33.59, SD = 14.51 |

| What is your gender? | Forced choice | Female: 62%; Male: 37%; Other: 0%; Decline: 0% |

| What is the highest degree or level of school you have completed? If currently enrolled, please indicate highest level received. | Forced choice | Less than high school: 2%; High school: 27%; Some college: 14%; Two year degree: 16%; Four year degree: 27%; Professional degree: 12%; Doctorate: 2%; Unknown: 0% |

| How would you describe the community where you're staying? | Forced choice | Urban: 56%; Suburban: 28%; Rural: 16% |

| Including you, how many members are there in your residence or household? | Open numeric | M = 3.68, SD = 2.45 |

| Of all the members, including you, how many have existing health conditions, such as heart or lung disease, diabetes, or a chronic illness? | Open numeric | M = 1.63, SD = 1.52 |

| On which rung would you place yourself on this [socioeconomic status] ladder? | Numeric (1 = lowest, 10 = highest) | M = 5.76, SD = 1.8 |

In the present experiment, participants were randomly assigned to read COVID-19 health recommendations adapted from World Health Organization (WHO) advisories (e.g., social distancing, mask wearing) that were framed in terms of losses (e.g., “if you do not practice these four steps, you can endanger yourself and others”) or gains (e.g., “if you practice these four steps, you can protect yourself and others”). To ensure that any observed effects arose from meaningful conceptual differences (as opposed to particular wording; see Wells & Windschitl, 1999), we also examined three variations of the framed messages (described below). These variations of the framed messages were designed to assess generalizability of loss vs. gain framing across different wordings. As such, the differences in wording are relatively minor compared to the more central manipulation of loss vs. gain framing. Thus, participants were randomly assigned to one of six between-subjects experimental conditions that varied both the framing and wording/version of the COVID-19 health recommendation.

Following the message framing manipulation, we measured four outcome variables: (1) behavioral intentions to follow guidelines to prevent COVID-19 transmission, (2) attitudes toward COVID-19 prevention policies, (3) whether participants chose to seek more information about COVID-19, and (4) self-reported anxiety. Seeking to create conditions under which one might detect any systematic effect of framing, we selected scale responses concerning behavioral intentions and information seeking as outcome variables. We selected attitudes toward COVID-19 prevention policies because garnering citizen support for public policies is a critical ingredient in successfully combating the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, we measured self-reported anxiety to assess the extent to which message framing may trigger unintended affective consequences, beyond traditional behavioral or policy outcomes.

Psychological Science Accelerator (PSA) COVID-19 Rapid Project

We conducted the present experiment as part of a larger PSA COVID-19 Rapid Project, which involved one pre-study general survey and three experiments related to COVID-19 (Forscher et al., 2020). The study and the experiments were presented online through the formR survey platform (Arslan et al., 2020). The present experiment was bundled with another experiment, both of which participants completed in random order after completing the pre-study general survey that included questions about beliefs and behaviors related to COVID-19.

Participants

Sample size was primarily determined by the availability of resources among members of the PSA. Nevertheless, results from an a-priori power simulation estimating power as a function of number of countries, number of participants per country, intraclass correlations, effect sizes, and between-country variability in effect sizes can be found at https://osf.io/m6q8f/. After excluding data from participants who (a) had corrupted data due to technical difficulties, (b) did not provide responses to our outcomes of interest, or (c) did not indicate their country of origin, we were left with data from 15,929 participants (62% female, 37% male, 1% other or non-response, < 1% other; Mage = 33.70 , SDage = 14.45), who lived in 84 different countries and completed the survey in a total of 48 languages. Participants were recruited either through semi-representative research panels (n = 5,555) or by PSA research groups (n = 10,374; see Forscher et al., 2020, for more details on sampling and translations). The survey was conducted during the Spring and Summer of 2020.

Procedure

Independent Variables

Participants were randomly assigned to view loss- or gain-framed versions of four recommendations related to COVID-19 adapted from the WHO in Spring 2020. These recommendations related to (1) staying home (unless absolutely necessary), (2) avoiding all shops other than necessary ones (such as for food), (3) wearing a mouth and nose covering in public at all times, and (4) completely isolating if exposed to COVID-19. All participants viewed four similarly worded recommendations—but were randomly assigned to view either a loss- or gain-framed message. To examine whether our conclusions generalize across multiple variants of framed messages, we created three different versions of each frame (see Wells & Windschitl, 1999, for more information on the importance of this stimulus sampling approach). Thus, the experiment took the form of a 2 (Framing: gain, loss) × 3 (Version: Version 1, Version 2, Version 3) between-subjects factorial design, featuring the following messages:

Gain/Version 1: “There is so much to gain. If you practice these four steps, you can protect yourself and others.”

Gain/Version 2: “You have so much to gain. You can protect yourself and others if you practice these four steps.”

Gain/Version 3: “There is so much to gain. Practicing these four steps can help you stay healthy and protect the health of others.”

Loss/Version 1: “There is so much to lose. If you do not practice these four steps, you can endanger yourself and others.”

Loss/Version 2: “You have so much to lose. You can endanger yourself and others if you do not practice these four steps.”

Loss/Version 3: “There is so much to lose. You can get sick and endanger the health of others if you do not practice these four steps.”

The four recommendations and dependent variables were displayed for all participants, with the message frame and version type varied by condition. The manipulated message appeared at the top of the pages displaying each recommendation and instructions when completing the outcome variables.

Manipulation Check

At the end of the survey, participants completed a manipulation check. We asked participants which of the following phrases, if any, they recalled reading during the survey: (a) There is so much to gain. You can stay healthy and protect others by...; (b) There is so much to lose. You can avoid losing your health and avoid endangering others by...”; or (c) neither. Exact wording varied to match the precise wording across the six conditions.

Dependent Variables

After reading the four recommendations (with message framing varied by condition), participants completed three self-report questionnaires: behavioral intentions to follow guidelines to prevent COVID-19 transmission, attitudes toward COVID-19 prevention policies, and self-reported anxiety (described below). Afterwards, participants completed a behavioral measure, wherein they indicated whether they would be interested in learning more information about safe practices regarding COVID-19 (and were thus directed to the WHO website). Full wording of all items are presented in Table 2. While the questions themselves were identical across conditions, participants received different instructions depending on their randomly-assigned condition. For example, for the behavioral intention questionnaire, participants in the gain/version 1 condition saw: “Stay healthy and protect others. There is so much to gain. We are interested in how you yourself will respond in the coming week in order to stay healthy and protect others.” Participants in the loss/version 1 condition saw: “Avoid losing your health and avoid endangering others. We are interested in how you yourself will respond in the coming week in order to avoid losing your health and avoid endangering others.” The presentation order of the dependent variables was held constant for all participants.

Table 2.

Outcome variables, question text, and response format for the main survey

| Outcome variable | Item | Response format |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Intentions | In the coming two weeks, if there is an order to stay at home at all times except times deemed essential, how likely are you to follow that order? | 7-point scale with the following points: Extremely unlikely, moderately unlikely, slightly unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, slightly likely, moderately likely, extremely likely |

| Behavioral Intentions | In the coming two weeks, if you are taking care of someone who is sick with COVID-19, how likely are you to wear a mouth and nose covering (such as a mask) in public at all times? | 7-point scale with the following points: Extremely unlikely, moderately unlikely, slightly unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, slightly likely, moderately likely, extremely likely |

| Behavioral Intentions | In the coming two weeks, if you notice yourself coughing and sneezing, how likely are you to wear a mouth and nose covering (such as a mask) in public at all times? | 7-point scale with the following points: Extremely unlikely, moderately unlikely, slightly unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, slightly likely, moderately likely, extremely likely |

| Behavioral Intentions | In the coming two weeks, if you think you may have been exposed to COVID-19, how likely are you to completely isolate yourself? | 7-point scale with the following points: Extremely unlikely, moderately unlikely, slightly unlikely, neither likely nor unlikely, slightly likely, moderately likely, extremely likely |

| Policy support (individual autonomy) | Government health officials should allow individuals to determine how best to deal with the present COVID-19 pandemic | 7-point scale with the following points: Strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, neither agree nor disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, strongly agree |

| Policy support (individual autonomy) | Individuals, not governments, should decide how best to act during the COVID-19 pandemic | 7-point scale with the following points: Strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, neither agree nor disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, strongly agree |

| Policy support (government power) | Government health officials should authorize law enforcement to fine anyone who violates restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 | 7-point scale with the following points: Strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, neither agree nor disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, strongly agree |

| Policy support (government power) | Government health officials should do everything in their power to address the spread of COVID-19, even if it severely limits daily activities for citizens | 7-point scale with the following points: Strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, neither agree nor disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, strongly agree |

| Policy support (government power) | Government health officials should decide how long social distancing practices stay in place | 7-point scale with the following points: Strongly disagree, moderately disagree, slightly disagree, neither agree nor disagree, slightly agree, moderately agree, strongly agree |

| Anxiety | To what extent do you feel anxious when considering these recommendations? | 5-point scale with the following points: not at all, slightly, moderately, very much, extremely |

| Anxiety | To what extent do you feel afraid when considering these recommendations? | 5-point scale with the following points: not at all, slightly, moderately, very much, extremely |

| Anxiety | To what extent do you feel fearful when considering these recommendations? | 5-point scale with the following points: not at all, slightly, moderately, very much, extremely |

| Information seeking | At the end of the study today, would you like to learn the latest reliable information about COVID-19? | binary response: yes, no |

For the outcome variables, we created ad-hoc face-valid measures and relied on exploratory analyses to assess internal consistency and convergent validity (see “Results” section).4 Participants first indicated their intentions to engage in a variety of COVID-19 preventative behaviors (adapted from WHO recommendations at the time of survey launch in Spring 2020). Specifically, participants indicated how likely they were to (1) stay at home at all times unless absolutely necessary, (2) avoid all shops other than necessary ones (such as for food), (3) wear a mouth and nose covering (such as a mask) in public at all times, and (4) completely isolate themselves if they think they have been exposed to COVID-19. The four questions were presented in a randomized order and all responses were on a 7-point scale (1 = Extremely unlikely to 7 = Extremely likely).

Of note, we observed an unexpected J-shaped distribution in behavioral intentions—wherein a large majority of participants indicated very strong intentions to engage in protective behaviors (M = 6.47, SD = 0.91 on a 7-point scale). In the SI, we discuss potential explanations for, and additional analyses regarding, the restriction of range. Despite the restriction of range (and thus smaller-than-expected variation in the measure), behavioral intentions were still correlated with other variables in the convergent validity analyses (rs from .04 to .35; described in “Results” section below). Furthermore, we did not observe a restriction of range in the other continuous outcomes: attitudes about policies that empower individuals (M = 3.46, SD = 1.93 on a 7-point scale), attitudes about policies that extend government power (M = 5.67, SD = 1.31 on a 7-point scale), and anxiety (M = 2.44, SD = 1.17 on a 5-point scale). Concerns about restrictions of range also were not applicable to the measure of information seeking (25% no, 75% yes).

After responding to the behavioral intention items, participants reported their attitudes toward five statements regarding COVID-19 prevention policies. The policy attitude items focused on trade-offs between individual rights and collective security. Two statements emphasized individual rights and autonomy (e.g., “Individuals, not governments, should decide how best to act during the COVID-19 pandemic”), whereas the other three statements emphasized collective security (e.g., “Government health officials should do everything in their power to address the spread of COVID-19, even if it severely limits daily activities for citizens”). The five questions were presented in a randomized order and all responses were on a 7-point scale (1 = Strongly disagree to 7 = Strongly agree).

Next, the survey asked participants to indicate the extent to which they felt anxious, afraid, and fearful when considering the COVID-19 health recommendations. The three questions were presented in a randomized order and all responses were on 5-point scales (1 = Not at all to 5 = Extremely).

Last, participants were asked if they would like to learn more information about COVID-19. (All participants, regardless of stated preference, received additional information about COVID-19 at the end of the study.) A one-item question asked participants: “At the end of the study today, would you like to learn the latest reliable information about COVID-19?” The dependent variable was assessed as a binary variable (Yes, No).

Ethics

All participating research groups either obtained approval from their host institution’s ethics committee, indicated that their institution did not require approval to conduct this type of experiment, or indicated that the experiment was covered by a preexisting ethics approval. All participants provided informed consent.

Results

First, we report a set of preliminary analyses concerning the manipulation check, internal consistency of scales, and convergent validity among variables. Next, we report the results of our inferential analyses. Finally, we report additional exploratory analyses regarding anxiety. Data, code, materials, power simulation details, and the pre-registered analysis plan for this experiment are available at https://osf.io/m6q8f/.

Preliminary Analyses

Manipulation Check

Results revealed that 73% of participants correctly identified their condition from among three different response options (gain message, loss message, or neither). In order to be conservative, and to keep with our pre-registration plan, we reported results with the full (Intent to Treat) sample even though 27% of participants did not correctly identify which treatment they received. Importantly, however, the pattern of results was similar when we restricted the sample to just the portion of the sample that passed the manipulation check (see SI for more information).

Internal Consistency of Outcome Measures

Internal consistency for both the four-item behavioral intention and three-item self-reported anxiety measures was appropriate (α > .78, average inter-item r > .47). The internal consistency of the five-item policy support measure, however, was lower than expected (α = .67; average inter-item r = .29). Thus, per our pre-registration plan, we performed an exploratory factor analysis. This exploratory factor analysis used varimax rotation and a minimal residual factoring method to identify two distinct subgroups of items: support for (1) policies that empower individuals to make decisions about COVID-19 (two items; α = .74; average inter-item r = .59), and (2) policies that extend governments’ ability to stop the spread of COVID-19 (three items; α = .77; average inter-item r = .53). These two scales were weakly and negatively correlated (r = − .15, p < .001), and we analyzed the two subscales separately. Our behavioral measure of information-seeking was a single item and thus internal consistency analyses are not applicable.

Convergent Validity of Outcome Variables

We examined the extent to which our outcome measures were associated with conceptually-related variables. To do so, we (a) post-hoc identified conceptually-related variables from the pre-study general survey, and (b) examined the extent to which they were associated with the outcome variables. Notably, these general survey items were administered before the present study (and thus were not affected by participants’ experience in the study). In all cases, we observed associations in the anticipated direction (ps < .001) that ranged from very small (|r| = .04) to medium (|r| = .35) in size. For example, behavioral intentions were positively associated with the self-reported number of times that participants had recently worn a mask (r = .28, p < .001; see SI for more detail).

Inferential Analyses

We first modeled each outcome variable using linear (for continuous variables) or logistic (for dichotomized variables) mixed-effects regression with message framing entered as an effect-coded factor, country-level random intercepts, and country-level random slopes. For all outcomes besides behavioral intentions, country-level random slopes led to singular fits and were subsequently removed. These convergence issues provided preliminary evidence that the estimated effects of message framing on our outcomes of interest were consistent across countries. To facilitate comparisons across outcomes, we also estimated the overall message framing effects using random-effects meta-analysis. For the meta-analysis, we used Cohen’s d as the effect size index, wherein positive values indicated higher levels of the outcome variables in the loss- (vs. gain-) framed conditions.5

Effects on Behavioral Intentions, Policy Support, and Information Seeking

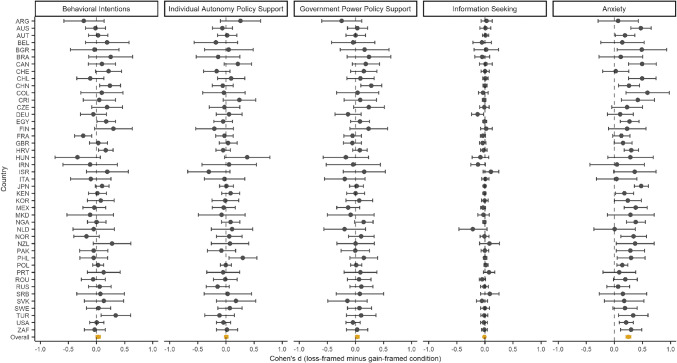

Our first set of analyses tested the effect of message framing on behavioral intentions, attitudes toward two types of policies, and information seeking. Results indicated that framing messages in terms of losses vs. gains had extremely small, non-significant effects on (1) intentions to engage in protective behavior a 0.03 increase on a 7-point scale; F(1, 35.17) = 2.70, p = .110, d = 0.03, 95% CI [− 0.01, 0.07], τ2 = 0.005; (2) support for policies that empower individuals to make decisions about COVID-19 a 0.01 increase on a 7-point scale; F(1, 15871) = 0.05, p = .826, d = 0.004, 95% CI [− 0.03, 0.04], τ2 ≈ 0; (3) support for policies that extend governments’ ability to stop the spread of COVID-19 a 0.04 increase on a 7-point scale; F(1, 15877) = 3.46, p = .063, d = 0.03, 95% CI [0.002, 0.06], τ2 ≈ 0; and (4) the probability that participants sought additional information about COVID-19 (a 1.2% point decrease; z = − 1.80, p = .071, d = − 0.008, 95% CI [− 0.02, 0.004], τ2 ≈ 0). Notably, the low τ2 values suggest that the estimated effects of message framing on our outcomes of interest were consistent across countries (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Loss-framed vs. gain-framed messages regarding COVID-19 influenced anxiety but not behavioral intentions, policy support, or information seeking. Cohen’s d was used as the effect size, with positive values indicating higher levels of the outcome variable in the loss-framed vs. gain-framed condition. Dots and bars represent the effect size estimates and 95% confidence intervals respectively. Country-level effect size estimates are denoted in black and overall effect size estimates are denoted in yellow. Country names are denoted by their International Organization for Standardization codes. To improve the viewability of the x-axis, 40 countries with fewer than 30 participants per group (i.e., relatively wide error bars) are removed from the plot. Nevertheless, these countries are still included in the overall effect size estimates

While we found little evidence of between-country heterogeneity in the effects of message framing on behavioral intentions, attitudes, and information seeking, we next examined whether these estimated effects were moderated by methodological features of the study, such as (a) the version of the framed message (versions 1–3), (b) the sampling pool (panel, non-panel), and (c) the order in which participants completed the two bundled studies (present experiment first, present experiment second). To do so, we separately added each moderator-of-interest and its higher-order interaction with message framing as effect-coded factors in the mixed-effects models described above. Results did not indicate that the message framing effects interacted with any of the moderators of interest (ps > .138).

To probe the robustness of the estimated effects of message framing on behavioral intentions, attitudes, and information seeking, we performed exploratory multiverse analyses (also sometimes described as a specification-curve analysis; Simonsohn et al., 2020; Steegen et al., 2016).6 The present multiverse analyses examined how 398 justifiable approaches to data processing and modeling affected our conclusions. Most approaches indicated that message framing did not impact intentions to engage in protective behavior (87% of models) or support for COVID-19-related policies (67% of models). In the scenarios where the estimated message framing effects were significant, the magnitudes were extremely small (i.e., less than a 0.06 change on a 7-point behavioral intentions measure; less than a 0.20 change in a 7-point policy support measure). Many justifiable data processing and analysis approaches did indicate that framing messages in terms of losses (vs. gains) decreased information seeking (80% of models). However, in these scenarios, the magnitude was small (i.e., less than a 4% point decrease in the probability of seeking information; see SI for more information).

Effects on Self-Reported Anxiety

The next set of analyses examined whether loss-framed vs. gain-framed messages had a differential impact on self-reported anxiety. Results indicated that participants reported higher levels of anxiety after being exposed to loss- (M = 2.58, SD = 1.18) vs. gain-framed (M = 2.30, SD = 1.14) messages, F(1, 15881) = 253.67, p < .001, d = 0.25, 95% CI [0.21, 0.29], τ2 = 0.007. Once again, the low τ2 value suggests that the estimated effect of message framing on anxiety was consistent across countries (see Fig. 2).

To assess these anxiety results in terms of practical perspective, we estimated the association between (a) self-reported personal exposure to COVID-19 (a presumably anxiety-producing event that was measured as a binary variable in the pre-study survey), and (b) experienced anxiety after the framing manipulation. The estimated effect of message framing on anxiety was nearly 1.5 times the size of the estimated association between actual exposure to COVID-19 and anxiety (which was associated with a 0.19 increase on the 5-point anxiety measure). Thus, in practical terms, the effect of message framing on anxiety appeared substantial. That being said, comparing the size of these relationships could be complicated by the fact that people who were exposed to COVID-19 and avoided negative outcomes could have decreased (rather than increased) anxiety.7 Future research is needed to further benchmark the relative size of loss- vs. gain-framing on self-reported anxiety.

Similar to the analyses of the other outcome variables, we next examined whether the estimated effect of framing on anxiety was moderated by methodological features of the study. Results did not indicate that the effect of message framing on anxiety was moderated by the version of the message (p = .368) or the sampling pool (p = .799). This implies that the underlying construct itself (loss vs. gain framing), rather than the particular wording associated with any instantiation of it, drives the effects. Inconsequentially, the message framing effect was moderated by the order in which participants completed the study, F(1, 15880) = 4.35, p = .037. Follow-up contrasts indicated that the effect of framing on anxiety was slightly larger when participants completed our study second (where message framing led to a 0.32 shift on the 5-point anxiety measure) vs. first (where message framing led to a 0.24 shift in the anxiety measure). It could be the case that completing the other study first (which also asked participants to read COVID-19 health messaging) heightened attention to COVID-19, and thus magnified the anxiety effects observed in the present data. Importantly, however, the observed effect of message framing on anxiety was significant regardless of the order of the studies (both ps < .0001) and the moderation by study order was relatively inconsequential in size compared to the overall effect of loss- vs. gain-framing.

Finally, we conducted a multiverse analysis to examine how 162 justifiable approaches to data processing and modeling affected our conclusions about anxiety. Strikingly, all 162 justifiable data processing and modeling approaches examined in the multiverse analysis indicated that framing messages in terms of losses (vs. gains) significantly increased anxiety (all ps < .001; all mean differences > 0.21). These results suggest that the inferences regarding the effects of message framing on anxiety are robust across a wide variety of justifiable analytic decisions.

Additional Analyses Regarding Pre-Study Worry

Our analyses to this point have examined anxiety in response to the framed messages. However, the pre-study survey also included two items assessing anxiety-relevant states: worry regarding one’s physical and emotional health. Both items were moderately correlated (r = .58) and answered on 5-point scales (1 = Not at all worried, 5 = Extremely worried). For simplicity, we averaged the two items and refer to this combined index as pre-study worry. (Statistical significance of results remains unchanged when we analyze the two items separately.)

In order to be maximally comprehensive, we conducted a set of exploratory (post-hoc) analyses concerning whether loss (vs. gain) framing would exert differential effects on any of the four outcome variables for individuals higher (vs. lower) on pre-study worry. That is, we tested whether pre-study worry moderated any of the message framing effects documented above. To test this possibility, we modeled each outcome variable with (a) frame entered as an effect-coded factor, (b) pre-study worry entered mean-centered, (c) their higher-order interaction, and (d) random intercepts for country. For behavioral intentions, policy support, and post-study anxiety, we used linear mixed-effect models; for information seeking, we used a logistic mixed-effect model. For all outcomes, there was not a significant interaction between message framing and pre-study worry (p > .43), suggesting that the effect of message framing did not depend on levels of pre-study worry.

Summary

While framing messages in terms of loss (versus gain) conferred little-to-no measured benefits, such loss framing exerted moderately sized and extremely consistent costs in terms of increased state anxiety (see Fig. 2). Moreover, the results for anxiety appeared consistent across countries, message wording, sampling pool, study order, and analytic choices—increasing confidence about generalizability.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic (and its aftermath) highlights a critical need to effectively communicate health information to the global public. It also highlights the importance of rapidly testing psychological interventions on a global scale. We experimentally tested the differential effects of framing messages in terms of losses vs. gains on COVID-19-related behavioral intentions, policy attitudes, information seeking, and experienced anxiety.

Results indicated that message framing had little-to-no measurable benefit for behavioral intentions, policy attitudes, or information seeking, but did have a significant emotional cost in terms of increased anxiety. These results were consistent across 84 countries, three variations of the message framing wording, across semi-representative and non-representative samples, across survey order, and across 560 data processing and analytic choices. Taken together, these results imply that the conceptual difference between loss- and gain-framing accounts for its effect on anxiety (rather than any particular phrasing of stimuli, culturally specific connotation, methodological feature, or data analytic approach).

The effect of message framing on anxiety when reading loss- vs. gain-framed health recommendations was nearly 1.5 times the size of the association between self-reported personal exposure to COVID-19 and anxiety when reading the health messages, revealing the important practical impact of loss framing. Because heightened anxiety has been associated with major causes of morbidity and mortality, diminished coping abilities, and neuroendocrine dysregulation, the heightened levels of anxiety under loss-framed messages represent an important outcome. Of course, the anxiety triggered in our study was relatively mild compared to acute levels associated with clinically-diagnosable anxiety disorders. Indeed, the average post-treatment anxiety was quite low in both framing conditions (2.58/5 and 2.30/5 for the loss and gain conditions, respectively). Nevertheless, public health communicators should benefit from learning that gain-framed messages COVID-19 messages are at least as effective as loss-framed messages in their impact on behavioral intentions, policy attitudes, and information seeking behavior—but induce significantly less anxiety at a population level.

While some commentators have urged organizations to “scare people” when communicating COVID-19 health information (e.g., in the New York Times; Rosenthal, 2020), the present results cast doubt on the wisdom of reminding people how much they stand to lose during the pandemic. Despite eliciting higher levels of anxiety, loss-framed (vs. gain-framed) messages did not meaningfully change behavioral intentions, information seeking behavior, or policy attitudes in the context of COVID-19. Admittedly, literature on fear appeals is nuanced (e.g., Kok et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2018). But because the present study is the largest and most globally representative study ever conducted on message framing and anxiety, there is compelling evidence that triggering anxiety through COVID-19 messaging does not improve behavioral intentions, attitudes, or actual behavior—at least in this context.

More generally, the present results contribute to a nascent literature broadening the scope of behavioral decision (nudge-style) interventions beyond strictly behavioral outcomes. Fields such as public health and health psychology have long considered affective states to be crucial outcome variables in and of themselves (e.g., Epel et al., 2018; Mikels et al., 2016; Taylor, 2021). The field of communication has also begun to consider affect as both an outcome itself and as a mediator of behavioral outcomes (Hameleers, 2021; Wong et al., 2013; Nabi et al., 2020). In the present work, we build both on these fields, and on emerging literature in behavioral decision research (Allcott & Kessler, 2019; Haushofer et al., 2021; Zlatev & Rogers, 2020), to propose that emotional consequences should be considered when evaluating the costs vs. benefits of nudge-style interventions (c.f., Glaeser, 2005).8 In the present case, under an expanded cost-benefit analysis that includes emotional consequences (c.f. Dukes et al., 2021), messages framed in terms of gains appear superior (for related discussion, see Loewenstein & O'Donoghue, 2006).

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its global scope, the present experiment features some methodological limitations. First, it remains unknown whether sustained framing interventions (rather than single shot) could have stronger effects. Given that the measures rely on self-report and that the anxiety effects are measured immediately (rather than over time), it is unclear to what extent such effects would persist outside of the specific experimental context. Second, the behavioral intentions variable exhibited restriction of range, which may have contributed to diminishing a message framing effect. However, behavioral intentions had sufficient variance to correlate with other expected predictors in the study (e.g., self-reported mask wearing), providing some evidence that the range was not sufficiently limited to preclude the detection of meaningful relationships. Moreover, we did not observe restrictions of range on policy attitudes and information seeking (variables that we similarly did not find affected by message framing).

A few future directions merit note. Most centrally, future research is needed to understand the lack of differential effects of loss vs. gain message framing on behavioral intentions, policy support, and information seeking. Perhaps the strongest explanation for why loss-gain framing shows substantial effects in other contexts—but not here—is because the present set-up differs substantially from classic loss-gain work on risk preferences. In canonical risk preference paradigms (e.g., Dorison & Heller, 2022; Kahneman & Tversky, 1979; Ruggeri et al., 2020; Tversky & Kahneman, 1991), participants are confronted with choices between a sure option and a risky gamble. Importantly, probabilities for each option are provided. Prior research identifies a robust effect that generalizes across contexts: people are typically risk-averse when the choice options are presented as losses but risk-seeking when choice options are presented as gains. Our paradigm intentionally deviated from this large body of research on loss-gain framing effects on risk preferences. In the present paradigm, probabilities were unknown and participants were not presented with a choice between a sure option and a risky gamble because it would have been unrealistic to provide known probabilities about the pandemic. Thus, the present paradigm follows more directly from research in the health psychology literature that compares health actions associated with gains (e.g., wearing sunscreen to clear skin) vs. inaction associated with losses (e.g., not wearing sunscreen to skin cancer). This literature has yielded mixed results (Rothman & Salovey, 1997; Rothman & Sheeran, 2021) for the effects of framing, suggesting that key moderators remain to be identified (for reviews, see Levin et al., 1998; van’t Riet et al., 2016).

There is at least one study, however, that used a reasonably comparable paradigm but which found divergent results: Abhyankar et al. (2008) found a loss-frame advantage on intentions to obtain the MMR vaccine for one’s child. It could be the case that the effects of loss- vs. gain-message framing differ when assessing health intentions for oneself vs. another person, especially when the other person is a child under one’s care. Additional possibilities include that there may be something specific about an unfolding (and highly uncertain) pandemic that blunted such effects or that the gain/loss manipulations were weaker in the present study.

Four additional future directions merit note. First, following from the point above, while we found limited heterogeneity by country, future research could explore heterogeneity in the effect of message framing across other dimensions (e.g., such as the tightness vs. looseness of the culture; Gelfand et al., 2021; Uskul et al., 2009). Indeed, it could be the case that our operationalization of country was limited by the manner in which we sampled participants. Second, while we also found limited heterogeneity in the effect of message framing across the different versions of loss and gain framing, future research could examine additional versions of these messages (e.g., self- vs. other-focused messages). Third, while we conducted an initial set of analyses with the pre-study survey (focused on pre-study worry), future research could test a more comprehensive set of hypotheses using these data. Finally, while the present work expanded the scope of nudge-style outcomes beyond behavior to include anxiety, future research is needed to further integrate emotional outcomes (both immediate and long-term) into cost-benefit calculations for implementing nudge-style interventions (e.g., framing). Not only does the subjective experience of emotion matter in and of itself (anxiety creates suffering) but also the myriad effects of emotion on health (e.g., Emdin et al., 2016; Kubzansky & Kawachi, 2020) and health behavior (e.g., Dorison, Wang et al., 2020; Dorison, Klusowski et al., 2020; Ferrer et al., 2020) matter as well.

Conclusion

In a global experiment spanning 84 countries and nearly 16,000 participants, loss vs. gain message framing had a widespread effect on self-reported anxiety while exerting no notable effects on cognitive and behavioral outcomes related to the COVID-19 pandemic. To the extent that policymakers and health organizations aim to minimize anxiety during a pandemic that has engendered high levels of stress and illness, our results provide evidence that gain framing may be superior to loss framing in communicating COVID-19 prevention messages. The results hold theoretical implications for multiple literatures, including research on health message framing, social influence, affective science, and public policy. More generally, the results underscore the lesson that, for policymakers and health organizations, large-scale collaborations can provide empirical answers to global questions (Coles et al., 2022; Forscher et al., in press), freeing communicators from having to rely on either intuition or speculation about applications of theory in particular contexts (c.f., Haushofer & Metcalf, 2020).

Additional Information

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the following sources: National Science Foundation (SES-1559511; J.S. Lerner); National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (RO1-CA-224545; V.W. Rees; also J.S. Lerner); European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, grant agreement No 769595 (Z. Chen); JSPS KAKENHI 16H03079, 17H00875, 18K12015, and 20H04581 (Y. Yamada); Research Grant EDUHK 28611118 awarded to W. Law by the Research Grant Council, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China; the Japanese Psychological Association, Grant for research and practical activities related to the spread of the novel coronavirus to (T. Ishii; K. Ihaya); Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (# 950-224884; T. Gill); Program FUTURE LEADER of Lorraine Université d’Excellence within the program Investissements Avenir (ANR-15-IDEX-04-LUE) operated by the French National Research Agency (S. Massoni); the Portuguese National Foundation for Science and Technology (UID/PSI/03125/2020; R.R. Ribeiro); the Australian Research Council (DP180102384; R.M. Ross); a PhD grant from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (PD/BD/150570/2020; R. Oliveira); a French National Research Agency ―Investissements d’avenir‖ program grant (ANR-15-IDEX-02) awarded to Hans IJzerman (supporting P.S. Forscher); VIDI Grant 452-17-013 from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (P.M. Isager); Slovak Research and Development Agency APVV-20-0319 (P. Kačmár); the Slovak Research and Development (project number APVV-17-0418; P. Babinčák); the Portuguese National Foundation for Science and Technology (UID/PSI/03125/2020; P. Arriaga); the Huo Family Foundation (N. Johannes); the research program ―Dipartimenti di Eccellenza‖ from MIUR to the Department of General Psychology of the University of Padua (N. Cellini; G. Mioni); CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), number PNPD 3002010037P0 – MEC/CAPES (M.A. Varella); Charles University Research Programme "Progres" Q18 (M. Vranka); Polish National Science Center & DFG Beethoven grant (2016/23/G/HS6/01775; M. Parzuchowski); the Foundation for Polish Science (; A. Groyecka-Bernard); the National Science Centre (2020/36/T/HS6/00256; M. Misiak; 2020/36/T/HS6/00254; A. Groyecka-Bernard); IDN Being Human Lab, University of Wroclaw (M. Misiak, A. Sorokowska, P. Sorokowski); Slovak Research and Development Agency APVV-18-0140 (M. Martončik); Slovak Research and Development Agency APVV-17-0596 (M. Hruška); Slovak Research and Development Agency APVV-20-0319 (M. Adamkovič); Rubicon Grant (019.183SG.007) from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (K. van Schie); the National Science Centre, Poland (UMO-2019/35/B/HS6/00528; K. Barzykowski); the statutory funds of the Institute of Psychology, Jagiellonian University (M. Kossowska, P. Szwed, G. Czarnek), ANID Millennium Science Initiative /Millennium Institute for Research on Depression and Personality-MIDAP ICS13_005 FONDECYT 1221538 (J.R. Silva); Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (2016:0229; J.K. Olofsson); the Slovak Research and Development Agency APVV-15-0662 (J.Benka); the Sherwin Early Career Professor in the Rock Ethics Institute (J.A. Soto); Penn State's Office of the Senior Faculty Mentor (J.A. Soto); German National Academic Foundation (J. Berkessel); the Scientific Grant Agency of the Slovak Republic under the grant No. VEGA 1/0748/19 (J. Bavolar); Chair for Public Trust in Health, Grenoble Ecole de Management (I. Ziano); PRIMUS/20/HUM/009 (I. Ropovik); Tufts University (H. Urry); the National Institute of Mental Health T32MN018931 (H. Moshontz); APVV-17-0418 (G. Banik); J. William Fulbright Program (F. Azevedo); the Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Veni from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research—Division for the Social Sciences 451-15-028 (E.S. Smit); AWS Imagine Grant (E.M. Buchanan); the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (D. Grigoryev); the Basic Research Program at HSE University, RF (D.Dubrov). Contract no. APVV-18-0140 (D. Dubrov); the Research Council of Norway 288083, 223273 (C. Tamnes); the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority 2020023 (A.D. Askelund); the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority 2019069, 2021070, 500189 (C. Tamnes); EFOP-3.6.1.-16-2016-00004 and NKFIH PD 137588 (A.N. Zsido); Faculty Development Grant from Dominican University (A.J. Krafnick); Portuguese National Foundation for Science and Technology SFRH/BD/126304/2016 (A.C. Santos); the statutory funds of the University of Wroclaw (A. Sorokowska); Internal funding from Kingston University (A. Gourdon-Kanhukamwe); the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contract no. APVV-17-0596 (A. Findor); Pacifica and the ANRT through the CIFRE grant 2017/0245 (A. Bran); Portuguese National Foundation for Science and Technology UIDP/4950/2020 (I. Almeida, A. Ferreira, D. Sousa); PhD grant co-funded by the Portuguese National Foundation for Science and Technology and the European Social Fund 2020.08597.BD (A. Ferreira); European Project H2020 Grant agreement ID 731827 STIPED - Transcranial brain stimulation as innovative therapy for chronic pediatric neuropsychiatric disorders (D. Sousa); a special grant from the Association for Psychological Science (to the Psychological Science Accelerator); an in-kind purchase from the Leibniz Institute for Psychology (protocol 10.23668/psycharchives.3012); a fee waiver from Prolific, Inc. Further financial support was provided by the Psychological Science Accelerator. We thank the Leibniz Institute for Psychology (ZPID) for help with data collection via the organization and implementation of semi-representative panels. Funders had no other roles in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Data and materials are available here: https://osf.io/m6q8f/.

Ethics Approval

All participating research groups either obtained approval from their host institution’s ethics committee, explicitly indicated that their institution did not require approval to conduct this type of experiment, or explicitly indicated that the experiment was covered by a preexisting ethics approval.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Code Availability

Code is available here: https://osf.io/m6q8f/.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided informed consent.

Contribution Statement

Conceptualization: C. A. Dorison, J. S. Lerner, B. H. Heller, A. J. Rothman, I. I. Kawachi, K. Wang, V. W. Rees, B. P. Gill, N. Gibbs, N. A. Coles

Data Curation: P.S. Forscher, E.M. Buchanan

Formal Analysis: N. A. Coles, C. A. Dorison

Funding Acquisition: P.S. Forscher, H. IJzerman, C. Chartier, E.M. Buchanan

Investigation: Z. Vally, Z. Tajchman, A.N. Zsido, Z. Chen, I. Ziano, C.D. Ceary, Y. Lin, Y. Kunisato, Q. Xiao, X. Jiang, E. Yao, J. Wilson, W. Jimenez-leal, W. Law, W. Collins, K.L. Richard, W. Vranka, V. Ankushev, V. Schei, U.S. Tran, S. Yeung, W. Hassan, T.J. Lima, T. Ostermann, T. Frizzo, T.E. Sverdrup, T. House, T. Gill, T. Jernsäther, Koptjevskaja-tamm, T.J. Hostler, T. Ishii, A. Studzinska, S.M. Janssen, S.E. Schulenberg, S. Tatachari, S. Azouaghe, P. Sorokowski, A. Sorokowska, X. Song, D. Grigoryev, S. Daches, S.N. Geniole, S. Vračar, S. Massoni, S. Zorjan, E. Sarıoğuz, S.G. Alves, S. Pöntinen, S. Álvarez Solas, S. Ordoñez-Riaño, S. Batić Očovaj, S. Onie, S. Lins, S. Çoksan, A. Sacakli, S. Ruiz-Fernández, S. Fatahmodares, R.B. Walczak, R. Vilar, R. Cárcamo, R.M. Ross, R. Mccarthy, T. Ballantyne, E.C. Westgate, R. Afhami, D. Ren, R.P. Monteiro, U.-D. Reips, N. Reggev, R.J. Calin-jageman, R. Oliveira, M. Nedelcheva-Datsova, R.-M. Rahal, T. Radtke, R. Searston, P. Zdybek, S. Chen, J.T. Perillo, P. Kačmár, P. Macapagal, P. Szwed, P. Hanel, P.AG. Forbes, P. Arriaga, K. Papachristopoulos, P.S. Correa, C. Ogbonnaya, O. Bialobrzeska, N. Kiselnikova, N. Simonovic, N. Nock, N. Albayrak-Aydemir, N. Say, N. Levy, N. Torunsky, N. Van Doren, N. Sunami, N.R. Rachev, N.M. Majeed, N.S. Corral-Frías, N. Ouherrou, M.Y. Lucas, M. Pantazi, M.R. Vasilev, M. Ortiz, M.M. Butt, R. Muda, M.M. Tejada Rivera, M. Sirota, M. Seehuus, M. Parzuchowski, M. Toro, M. Hricova, M. Marszalek, M. Karekla, G. Mioni, M. Westerlund, M. Vdovic, M. Bialek, M. Anne, M. Misiak, M. Grinberg, M.F. Espinoza Barría, M.C. Mensink, M. Harutyunyan, M. Khosla, M. Adamkovič, M.F. Ribeiro, M. Terskova, M. Hruška, M. Martončik, M. Voracek, M. Frias-Armenta, M. Kowal, M. Roczniewska, M. Braun Kohlová, M. Paruzel-Czachura, M. Romanova, M. Papadatou-Pastou, M.V. Jones, M.S. Ortiz, M. Manavalan, M. Kossowska, M.A. Varella, M.F. Colloff, M. Bradford, L. Vaughn, L. Eudave, L. Vieira, L. Calderón Pérez, L.B. Lazarevic, L.M. Jaremka, E. Kushnir, G. Lins De Holanda Coelho, L. Ahlgren, L. Volz, L. Boucher, L. Javela Delgado, L. Beatrix, K. Yu, J. Wachowicz, K. Desai, K. Barzykowski, L. Kozma, K. Evans, M.A. Koehn, K. Wolfe, K. Klevjer, K. Vezirian, K. Damnjanović, K. Schmidt, K. Moon, J. Kielińska, J.E. Cruz Vásquez, J. Vargas-nieto, J.T. Roxas, J. Taber, J. Urriago-Rayo, J.M. Pavlacic, J. Bavolar, J.A. Soto, J.K. Olofsson, J.K. Vilsmeier, J. Czamanski-cohen, J. Boudesseul, J. Kamburidis, J. Zickfeld, J.F. Miranda, E. Hristova, J. Milosevic Djordjevic, J.V. Valentova, J. Antfolk, J. Berkessel, J. Schrötter, J. Urban, J. Röer, J.O. Norton, J.R. Silva, J. Uttley, J.R. Kunst, I.L. Ndukaihe, A. Iyer, I. Vilares, A. Ivanov, I. Ropovik, I. Sarieva, I. Prusova, I. Pinto, I.A. Almeida, I. Dalgar, I. Zakharov, A.I. Arinze, K. Ihaya, I.D. Stephen, B. Gjoneska, H. Brohmer, H. Flowe, H. Godbersen, H. Kocalar, M.V. Hedgebeth, H. Manley, G. Kaminski, G. Nilsonne, G. Anjum, G.A. Travaglino, G. Feldman, G. Pfuhl, G.M. Marcu, G. Hofer, G. Banik, G. Bijlstra, F. Verbruggen, F.Y. Kung, F. Foroni, G. Singer, F. Mosannenzadeh, E. Marinova, E. Štrukelj, E. Baskin, E. Luis Garcia, E. Musser, E. Ahn, E. Pronizius, E.A. Jackson, E. Manunta, E. Agadullina, D. Šakan, O. Dujols, D. Dubrov, M. Willis, M. Tümer, I. Djamai, D. Vega, H. Du, D. Mola, W.E. Davis, D. Holford, D. Lewis, D.C. Vaidis, D. Hausman Ozery, D. Zambrano Ricaurte, D. Storage, D. Sousa, D. Serrato Alvarez, A. Dalla Rosa, D. Marko, D. Moreau, C. Reeck, R.C. Correia, C.M. Whitt, C. Lamm, C. Singh Solorzano, C.C. von Bastian, C.A.M. Sutherland, C.L. Aberson, C. Karashiali, C. Noone, F. Chiu, C. Karaarslan, N. Cellini, C. Esteban-serna, C. Reyna, C. Batres, C. Grano, J. Carpentier, C.H. Fu, B. Jaeger, C. Bundt, T. Bulut Allred, A. Bokkour, N. Bogatyreva, W.J. Chopik, B. Antazo, B. Behzadnia, M. Becker, W. Chou, H. Bai, B. Balci, P. Babinčák, B.J.W. Dixson, A. Mokady, H.B. Kappes, M. Atari, J. Aruta, A. Domurat, N.C. Arinze, A. Vatakis, A. Adiguzel, K. Ait El Arabi, A.A. Özdoğru, A. Olaya Torres, A. Theodoropoulou, A.P. Kassianos, A. Findor, A. Hartanto, A. Thibault Landry, A. Ferreira, A.C. Santos, A. De La Rosa-Gomez, A. Gourdon-Kanhukamwe, A. Karababa, A. Janak, A. Bran, A.M. Tullett, A.O. Kuzminska, A.J. Krafnick, A. Urooj, A. Khaoudi, A. Ahmed, A. Groyecka-Bernard, A. Askelund, A. Adetula, A. Belaus, A.C. Charyate, A.L. Wichman, A. Stoyanova, A. Greenburgh, A. Thomas, A. Arvanitis, P.S. Forscher, J.K. Miller, H. Urry, H. IJzerman, E.M. Buchanan, M.A. Primbs

Methodology: C. A. Dorison, J. S. Lerner, B. H. Heller, A. J. Rothman, I. I. Kawachi, K. Wang, V. W. Rees, B. P. Gill, N. Gibbs, N. A. Coles

Project Administration: C.R. Ebersole, Y. Yamada, M. Vranka, V. Kriţanić, S.C. Lewis, S. Meir Drexler, S. Morales Izquierdo, N. Reggev, R. Habte, P. Hanel, P. Arriaga, B. Paris, M.R. Vasilev, M. Alarcón Maldonado, M.A. Silan, M. Martončik, M. Oosterlinck, C.A. Levitan, L. Volz, L. Kozma, K. Barzykowski, K. Kirgizova, K. Thommesen, J.W. Suchow, J.E. Beshears, J. Antfolk, I. Sula, I.L. Pit, I. Dalgar, B. Gjoneska, H. Chuan-Peng, M. Sharifian, H. Azab, G. Kaminski, G.M. Marcu, F. Azevedo, E. Štrukelj, E. Pronizius, J.L. Beaudry, D. Dunleavy, F. Chiu, N. Cellini, B. Ishkhanyan, L. Bylinina, T. Bulut Allred, M. Becker, A. Szabelska, A.P. Kassianos, A. Gourdon-Kanhukamwe, A. Todsen, A. Urooj, A. Ahmed, A. Askelund, A. Adetula, P.S. Forscher, P.R. Mallik, N.A. Coles, J.K. Miller, H. Moshontz, H. Urry, H. IJzerman, D.M. Basnight-brown, C. Chartier, E.M. Buchanan, M.A. Primbs.

Resources: A.N. Zsido, M. Zrimsek, Z. Chen, Z. Gialitaki, Y. Kunisato, Y. Yamada, X. Jiang, X. Du, E. Yao, W. Cyrus-lai, W. Law, M. Vranka, V. Schei, V. Kriţanić, V.H. Kadreva, V. Cubela Adoric, R. Houston, T.E. Sverdrup, M. Fedotov, T. Jernsäther, M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm, T. Ishii, B. Szaszi, S. Adamus, L. Suter, S. Habib, A. Studzinska, D. Stojanovska, S. Stieger, S. Azouaghe, S.C. Lewis, S. Sinkolova, S. Meir Drexler, S. Massoni, E. Sarıoğuz, S. Morales Izquierdo, S.G. Alves, S. Pöntinen, S. Çoksan, A. Sacakli, S. Ruiz-Fernández, S.J. Geiger, R. Betlehem, R. Vilar, R.P. Monteiro, U.-D. Reips, N. Reggev, R. Pourafshari, R. Oliveira, M. Nedelcheva-datsova, R.R. Ribeiro, R. Habte, S. Chen, P.G. Maturan, P. Kačmár, P. Hanel, P. Arriaga, B. Paris, O. Kácha, M. Bernardo, O. Campos, O. Niño Bravo, O.J. Galindo-Caballero, O. Bialobrzeska, N. Cohen, N. Johannes, N. Say, N. Sunami, N.R. Rachev, N. Schmidt, K. Nadif, M. Pantazi, M.R. Vasilev, M. Kabir, M. Parzuchowski, M. Alarcón Maldonado, M. Marszalek, G. Mioni, M.J. Bosma, M. Westerlund, M. Vdovic, M. Bialek, M.A. Silan, M. Capizzi, M. A. Kurfali, M. Harutyunyan, M. Korbmacher, M. Adamkovič, M. Hruška, M. Čadek, M. Kowal, M. Topor, M. Roczniewska, M. Oosterlinck, M. Paruzel-Czachura, M. Lund, M. Antoniadi, A. Muminov, M. Kossowska, M. Friedemann, M. Wielgus, L. Vieira, L. Sanabria Pineda, E. Kushnir, L. Anton-boicuk, G. Lins De Holanda Coelho, L. Ahlgren, C.A. Levitan, L. Micheli, L. Volz, M. Stojanovska, L. Samojlenko, L. Kaliska, L. Beatrix, L. Warmelink, L. Rojas-Berscia, J. Wachowicz, K. Barzykowski, L. Kozma, K. Kirgizova, B.B. Agesin, T. Korobova, K. Klevjer, K. Van Schie, K. Vezirian, K. Thommesen, K. Filip, K. Grzech, K. Hoyer, K. Rana, K. Janjić, J. Kielińska, J. Beitner, J. Vargas-Nieto, J. Bavolar, J. Messerschmidt, J. Czamanski-cohen, J. Lee, J. Kamburidis, J. Zickfeld, J.P.H. Verharen, E. Hristova, J.E. Beshears, J. Milosevic Djordjevic, J. Bosch, J. Antfolk, J. Berkessel, J. Schrötter, J. Vintr, J.R. Kunst, I. Ropovik, I. Sula, I. Metin-orta, A. Bozdoc, I.L. Pit, I. Dalgar, I. Zakharov, K. Ihaya, B. Gjoneska, H. Kocalar, H. Chuan-Peng, M. Sharifian, H. Akkas, H. Azab, G. Kaminski, G. Nilsonne, G. Czarnek, G.M. Marcu, G. Banik, G.A. Adetula, F. Muchembled, F. Azevedo, F. Mosannenzadeh, E. Marinova, E. Štrukelj, Z. Etebari, I.M.M. van Steenkiste, E. Pronizius, E. Manunta, D. Šakan, P. Dursun, O. Dujols, D. Dubrov, M. Tümer, J.L. Beaudry, D. Popović, D. Dunleavy, I. Djamai, D. Krupić, D. Vega, D. Zambrano Ricaurte, D. Serrato Alvarez, A. Dalla Rosa, D. Krupić, D. Marko, R.C. Correia, C. Singh Solorzano, C.C. von Bastian, C. Overkott, C. Wang, F. Chiu, C. Picciocchi, C. Karaarslan, N. Cellini, R. Li, C. Grano, C. Tamnes, B. Ishkhanyan, T. Bulut Allred, A. Bokkour, N. Bogatyreva, B. Antazo, M. Becker, B. Cocco, B. Hubena, B. Ţuro, B. Aczel, E. Baklanova, A. Mokady, A. Szala, A. Szabelska, J. Aruta, A. Domurat, A. Modena, A. Adiguzel, A. Monajem, K. Ait El Arabi, A.A. Özdoğru, A. Penić Jurković, A.P. Kassianos, A. Findor, A. Thibault Landry, A.C. Santos, A. Gourdon-Kanhukamwe, A. Todsen, A. Karababa, A. Bran, A. Khaoudi, A. Ahmed, A. Groyecka-Bernard, A. Askelund, A. Adetula, A. Stoyanova, E.M. Buchanan

Supervision: C.R. Ebersole, K. Thommesen, J.W. Suchow, M. Sharifian, A. Todsen, P.S. Forscher, P.R. Mallik, N.A. Coles, J.K. Miller, H. Moshontz, H. Urry, H. IJzerman, D.M. Basnight-brown, C. Chartier, E.M. Buchanan, M.A. Primbs

Writing - Original Draft: C. A. Dorison, J. S. Lerner, B. H. Heller, A. J. Rothman, I. I. Kawachi, K. Wang, V. W. Rees, B. P. Gill, N. Gibbs, N. A. Coles

Writing - Review and Editing: C. A. Dorison, J. S. Lerner, B. H. Heller, A. J. Rothman, I. I. Kawachi, K. Wang, V. W. Rees, B. P. Gill, N. Gibbs, N. A. Coles, C.R. Ebersole, Z. Vally, Z. Tajchman, A.N. Zsido, M. Zrimsek, Z. Chen, I. Ziano, Z. Gialitaki, C.D. Ceary, Y. Jang, Y. Lin, Y. Kunisato, Y. Yamada, Q. Xiao, X. Jiang, X. Du, E. Yao, J. Wilson, W. Cyrus-Lai, W. Jimenez-Leal, W. Law, W. Collins, K.L. Richard, M. Vranka, V. Ankushev, V. Schei, V. Kriţanić, V.H. Kadreva, V. Cubela Adoric, U.S. Tran, S. Yeung, W. Hassan, R. Houston, T.J. Lima, T. Ostermann, T. Frizzo, T.E. Sverdrup, T. House, T. Gill, M. Fedotov, T. Jernsäther, M. Koptjevskaja-Tamm, T.J. Hostler, T. Ishii, B. Szaszi, S. Adamus, L. Suter, S. Habib, A. Studzinska, D. Stojanovska, S.M. Janssen, S. Stieger, S.E. Schulenberg, S. Tatachari, S. Azouaghe, P. Sorokowski, A. Sorokowska, X. Song, S.C. Lewis, S. Sinkolova, D. Grigoryev, S. Meir Drexler, S. Daches, S.N. Geniole, S. Vračar, S. Massoni, S. Zorjan, E. Sarıoğuz, S. Morales Izquierdo, S.G. Alves, S. Pöntinen, S. Álvarez Solas, S. Ordoñez-Riaño, S. Batić Očovaj, S. Onie, S. Lins, S. Çoksan, A. Sacakli, S. Ruiz-Fernández, S.J. Geiger, S. Fatahmodares, R.B. Walczak, R. Betlehem, R. Vilar, R. Cárcamo, R.M. Ross, R. Mccarthy, T. Ballantyne, E.C. Westgate, R. Afhami, D. Ren, R.P. Monteiro, U.-D. Reips, N. Reggev, R.J. Calin-jageman, R. Pourafshari, R. Oliveira, M. Nedelcheva-Datsova, R. Rahal, R.R. Ribeiro, T. Radtke, R. Searston, R. Habte, P. Zdybek, S. Chen, P.G. Maturan, J.T. Perillo, P.M. Isager, P. Kačmár, P. Macapagal, P. Szwed, P. Hanel, P.A.G. Forbes, P. Arriaga, B. Paris, K. Papachristopoulos, P.S. Correa, O. Kácha, M. Bernardo, O. Campos, O. Niño Bravo, O.J. Galindo-caballero, C. Ogbonnaya, O. Bialobrzeska, N. Kiselnikova, N. Simonovic, N. Cohen, N. Nock, N. Johannes, N. Albayrak-Aydemir, N. Say, N. Levy, N. Torunsky, N. Van Doren, N. Sunami, N.R. Rachev, N.M. Majeed, N. Schmidt, K. Nadif, N.S. Corral-Frías, N. Ouherrou, M. Pantazi, M.Y. Lucas, M.R. Vasilev, M. Ortiz, M.M. Butt, M. Kabir, R. Muda, M.M. Tejada Rivera, M. Sirota, M. Seehuus, M. Parzuchowski, M. Toro, M. Hricova, M. Alarcón Maldonado, M. Marszalek, M. Karekla, G. Mioni, M.J. Bosma, M. Westerlund, M. Vdovic, M. Bialek, M.A. Silan, M. Anne, M. Misiak, M. Grinberg, M. Capizzi, M.F. Espinoza Barría, M. A. Kurfali, M.C. Mensink, M. Harutyunyan, M. Khosla, M. Korbmacher, M. Adamkovič, M.F. Ribeiro, M. Terskova, M. Hruška, M. Martončik, M. Voracek, M. Čadek, M. Frias-Armenta, M. Kowal, M. Topor, M. Roczniewska, M. Oosterlinck, M. Braun Kohlová, M. Paruzel-Czachura, M. Romanova, M. Papadatou-Pastou, M. Lund, M. Antoniadi, M.V. Jones, M.S. Ortiz, M. Manavalan, A. Muminov, M. Kossowska, M. Friedemann, M. Wielgus, M.A. Varella, M.F. Colloff, M. Bradford, L. Vaughn, L. Eudave, L. Vieira, L. Sanabria Pineda, L. Calderón Pérez, L.B. Lazarevic, L.M. Jaremka, E. Kushnir, L. Anton-boicuk, G. Lins De Holanda Coelho, L. Ahlgren, C.A. Levitan, L. Micheli, L. Volz, M. Stojanovska, L. Boucher, L. Samojlenko, L. Javela Delgado, L. Kaliska, L. Beatrix, L. Warmelink, L. Rojas-berscia, K. Yu, J. Wachowicz, K. Desai, K. Barzykowski, L. Kozma, K. Evans, K. Kirgizova, B.B. Agesin, M.A. Koehn, K. Wolfe, T. Korobova, K. Klevjer, K. Van Schie, K. Vezirian, K. Damnjanović, K. Thommesen, K. Schmidt, K. Filip, K. Grzech, K. Hoyer, K. Moon, K. Rana, K. Janjić, J.W. Suchow, J. Kielińska, J.E. Cruz Vásquez, J. Beitner, J. Vargas-Nieto, J.T. Roxas, J. Taber, J. Urriago-Rayo, J.M. Pavlacic, J. Bavolar, J.A. Soto, J.K. Olofsson, J.K. Vilsmeier, J. Messerschmidt, J. Czamanski-cohen, J. Boudesseul, J. Lee, J. Kamburidis, J. Zickfeld, J.F. Miranda, J.P. Verharen, E. Hristova, J.E. Beshears, J. Milosevic Djordjevic, J. Bosch, J.V. Valentova, J. Antfolk, J. Berkessel, J. Schrötter, J. Urban, J. Röer, J.O. Norton, J.R. Silva, J.S. Pickering, J. Vintr, J. Uttley, J.R. Kunst, I.L. Ndukaihe, A. Iyer, I. Vilares, A. Ivanov, I. Ropovik, I. Sula, I. Sarieva, I. Metin-orta, I. Prusova, I. Pinto, A. Bozdoc, I.A. Almeida, I.L. Pit, I. Dalgar, I. Zakharov, A.I. Arinze, K. Ihaya, I.D. Stephen, B. Gjoneska, H. Brohmer, H. Flowe, H. Godbersen, H. Kocalar, M.V. Hedgebeth, H. Chuan-Peng, M. Sharifian, H. Manley, H. Akkas, H. Azab, G. Kaminski, G. Nilsonne, G. Anjum, G.A. Travaglino, G. Feldman, G. Pfuhl, G. Czarnek, G.M. Marcu, G. Hofer, G. Banik, G.A. Adetula, G. Bijlstra, F. Verbruggen, F.Y. Kung, F. Foroni, G. Singer, F. Muchembled, F. Azevedo, F. Mosannenzadeh, E. Marinova, E. Štrukelj, Z. Etebari, E. Baskin, E. Luis Garcia, E. Musser, I.M.M. van Steenkiste, E. Ahn, E. Pronizius, E.A. Jackson, E. Manunta, E. Agadullina, D. Šakan, P. Dursun, O. Dujols, D. Dubrov, M. Willis, M. Tümer, J.L. Beaudry, D. Popović, D. Dunleavy, I. Djamai, D. Krupić, D. Vega, H. Du, D. Mola, W.E. Davis, D. Holford, D. Lewis, D.C. Vaidis, D. Hausman Ozery, D. Zambrano Ricaurte, D. Storage, D. Sousa, D. Serrato Alvarez, A. Dalla Rosa, D. Krupić, D. Marko, D. Moreau, C. Reeck, R.C. Correia, C.M. Whitt, C. Lamm, C. Singh Solorzano, C.C. von Bastian, C.A.M. Sutherland, C. Overkott, C.L. Aberson, C. Wang, C. Karashiali, C. Noone, F. Chiu, C. Picciocchi, C. Karaarslan, N. Cellini, C. Esteban-serna, C. Reyna, C. Batres, R. Li, C. Grano, J. Carpentier, C. Tamnes, C.H. Fu, B. Ishkhanyan, L. Bylinina, B. Jaeger, C. Bundt, T. Bulut Allred, A. Bokkour, N. Bogatyreva, W.J. Chopik, B. Antazo, B. Behzadnia, M. Becker, B. Cocco, W. Chou, B. Hubena, B. Ţuro, B. Aczel, E. Baklanova, H. Bai, B. Balci, P. Babinčák, B.J.W. Dixson, A. Mokady, H.B. Kappes, M. Atari, A. Szala, A. Szabelska, J. Aruta, A. Domurat, N.C. Arinze, A. Modena, A. Vatakis, A. Adiguzel, A. Monajem, K. Ait El Arabi, A.A. Özdoğru, A. Olaya Torres, A. Theodoropoulou, A. Penić Jurković, A.P. Kassianos, A. Findor, A. Hartanto, A. Thibault Landry, A. Ferreira, A.C. Santos, A. De La Rosa-gomez, A. Gourdon-Kanhukamwe, A. Todsen, A. Karababa, A. Janak, A. Bran, A.M. Tullett, A.O. Kuzminska, A.J. Krafnick, A. Urooj, A. Khaoudi, A. Ahmed, A. Groyecka-Bernard, A. Askelund, A. Adetula, A. Belaus, A.C. Charyate, A.L. Wichman, A. Stoyanova, A. Greenburgh, A. Thomas, A. Arvanitis, P.S. Forscher, P.R. Mallik, J. K. Miller, H. Moshontz, H. Urry, H. IJzerman, D.M. Basnight-brown, C. Chartier, E.M. Buchanan, M.A. Primbs.

Contributions listed here reflect reported contributions to the project. People who helped with translation are listed as Resources contributors; people who helped with data collection are listed as Investigation contributors.

The final list of authors is roughly organized in 3 tiers, with the first tier (Dorison to Gibbs) being the lead scientific team, the third tier (Forscher to Coles) being the lead administration team, and all else contributing primarily to data collection, translation, methodology, and administrative tasks. Within the first tier, authorship order corresponds to the amount of contribution. Within the second and third tiers, authorship order is largely arbitrary.

There were additional contributors to this project who declined to be included as authors because they felt their contribution did not merit authorship or did not reply to requests to provide information and approval. These people served in various roles, including Resources, Project Administration, Methodology, and Investigation.

Footnotes

Although behavioral decision researchers studying loss vs. gain framing have traditionally examined emotional states to understand their influence on behaviors and attitudes (for reviews, Dorison, Klusowski et al., 2020; Lerner et al., 2015), they have tended to omit emotion as an outcome in nudge-style interventions (i.e., interventions that encourage desirable behavior without restricting choice or introducing economic incentives; Thaler & Sunstein, 2009). For counter-examples, see Allcott & Kessler, 2019; Loewenstein & O'Donoghue, 2006; Zlatev & Rogers, 2020.

Anxiety disorders are ranked as the sixth largest contributor to non-fatal health loss globally and appear in the top 10 causes of years of healthy life lost in all WHO Regions (World Health Organization, 2021). We chose anxiety not only because it was a focal emotional state heightened by the pandemic (Aknin et al., 2021), but also because of its association with negative downstream consequences for coping and for overall health.

For country classification, we relied on standards promoted by the International Organization for Standardization. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the presence of ongoing territory disputes that are not reflected in these standards.

Unfortunately, due to the time pressure to launch this international data collection effort at the onset of the global pandemic, we did not have time to pretest the stimuli for the study.

For dichotomous outcomes (i.e., information seeking), we converted log odds ratios to Cohen’s ds (Borenstein et al., 2009). Countries without at least one observation in each of the conditions were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Such multiverse analyses acknowledge that (1) there are often many justifiable approaches to processing and modeling data, (2) justifiable differences in the processing and modeling of data can change the inferences one might draw from the data, (3) examining different data processing and modeling approaches helps probe the robustness of a set of results, and (4) reporting how different data processing and modeling approaches impact results can improve the transparency and credibility of research findings (Lebel et al., 2018). In the main text, we describe the results of multiverse analysis models that converged. Nevertheless, we describe the results of additional analytic approaches that yielded model convergence issues in the SI.

We thank the review team for this point.

This idea is not new. Economist Jeremy Bentham’s original (1879) conception of utility emphasized happiness as “the greatest good” (for discussion, see Lerner et al., 2022).

Erin M. Buchanan and Nicholas A. Coles contributed equally to this work.

References