Abstract

Objective

This qualitative study sought to uncover factors that influence decisions to offer curative-intent surgery for patients with advanced-stage (stage IIIB/IV) non–small cell lung cancer.

Methods

A trained interviewer conducted open-ended, semistructured telephone interviews with cardiothoracic surgeons in the United States. Participants were recruited from the Thoracic Surgery Outcomes Research Network, with subsequent diversification through snowball sampling. Four hypothetical clinical scenarios were presented, each demonstrating varying levels of ambiguity with respect to international guideline recommendations. Interviews continued until thematic saturation was reached. Interview transcripts were coded using inductive reasoning and conventional content analysis.

Results

Of the 27 participants, most had been in practice for ≤20 years (n = 23) and were in academic practice (n = 18). When considering nonguideline-concordant surgeries, participants were aware of relevant guidelines but acknowledged their limitations for unique scenarios. Surgeons perceived that a common barrier to offering surgery is incomplete nonsurgeon physician understanding of surgical capabilities or expected morbidity; and that improved education is necessary to correct these misperceptions. Surgeons expressed concern that undertaking a controversial resection for an individual patient could fracture trust built in long-term professional relationships. Surgeons may face pressure from patients to operate despite a low expectation of clinical benefit, leading to emotional turmoil for the patient and surgeon.

Conclusions

This qualitative study generates the hypothesis that the scope of current guidelines, availability of clinical trial protocols, perceived surgical knowledge among nonsurgeon colleagues, interprofessional relationships, and emotional pressure all influence a surgeon's willingness to offer curative-intent surgery for patients with advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer.

Key Words: surgical decision-making, disparities, multidisciplinary, qualitative

Abbreviations and Acronyms: NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; ThORN, Thoracic Surgery Outcomes Research Network

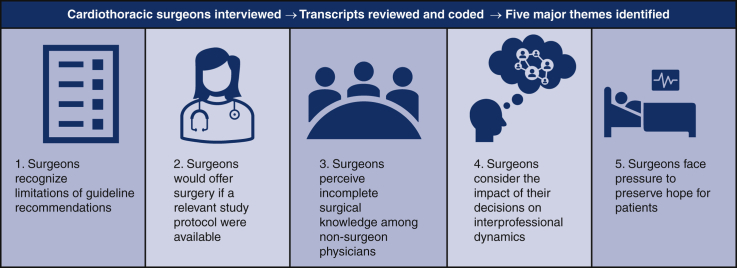

Graphical abstract

Surgical decision-making for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC is influenced by a complex network of factors.

Surgical decision-making in advanced-stage NSCLC is subject to multifactorial influence.

Central Message.

A surgeon's decision to offer resection for advanced-stage NSCLC is subject to multifactorial influences, including current guidelines, clinical trial availability, and interpersonal dynamics.

Perspective.

There is a paucity of surgical literature exploring the initial decision to offer resection for presentations without definitive guideline recommendations. This study uncovers factors that impact a surgeon's decision to offer resection for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC. Increased awareness of these factors may serve to mitigate undue influence on the surgical decision-making process.

Non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains the leading cause of cancer death in the United States, with 44% and 35% 2-year lung-cancer-specific survival for women and men, respectively.1,2 Approximately 78% of patients with NSCLC are found to suffer from regional or distant disease at diagnosis, likely due in part to poor understanding and use of proper screening practices.2,3 Furthermore, treatment differences contribute to disparate survival between patients with advanced NSCLC of the same stage.4,5 A recent propensity-matched analysis found increasing rates of no treatment for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC and determined that inferior survival outcomes among untreated patients are not attributable solely to selection bias.4 While surgical treatment for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC has decreased, studies have also suggested improved overall survival for patients who receive surgery compared with same-stage counterparts who receive nonsurgical treatment only or no treatment at all.5, 6, 7

The potential for therapeutic surgical intervention in advanced-stage NSCLC will likely expand with continued improvements in systemic therapy.8 As more patients with advanced-stage NSCLC experience stable disease following improved systemic therapy, new questions will arise regarding the role of surgical intervention. To ensure appropriate surgical evaluation in this modern evolution of care for advanced-stage NSCLC, it is critical to consider how treatment decisions are influenced by patient- and physician-level factors, including race, socioeconomic status, and referral patterns.9, 10, 11, 12, 13

The surgical community has taken a growing interest in reevaluating communication strategies to safeguard patient treatment preferences, but there is a paucity of research describing the thought processes underlying a surgeon's initial decision to offer resection, particularly for patient presentations beyond the scope of current guidelines.14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Moreover, a recent qualitative study revealed ambivalence among cardiothoracic surgeons toward health services research and existing guidelines for advanced-stage NSCLC.19 Our study is the first to thoroughly explore the nuances of surgical decision-making in cardiothoracic surgeons evaluating and treating patients with advanced-stage (stage IIIB/IV) NSCLC.

Methods

Between December 1, 2017, and April 30, 2018, a single trained interviewer performed open-ended telephone interviews lasting 45 to 60 minutes with cardiothoracic surgeons in the United States. Interview recordings were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were deidentified before analysis. A brief demographic survey was administered with the interview. Participants were recruited from the Thoracic Surgery Outcomes Research Network (ThORN), a multi-institutional group that supports health services and outcomes research in general thoracic surgery.20 Snowball sampling was used to diversify the participant pool; interviewees were asked to identify other surgeons whom they felt might offer an interesting perspective.21 Given that most ThORN members are general thoracic surgeons and practice at academic centers, prospective participants who differed from this typical practice profile were of particular interest. Surgeons were invited to participate via a maximum of 3 emails. Communication with all potential participants was tracked. Participating surgeons were given a $100 gift card after completing the interview. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. This study was deemed exempt by the University of California, Davis institutional review board.

The interview was conducted in 3 phases exploring (1) previous experiences treating patients with advanced-stage NSCLC; (2) 4 hypothetical case-based clinical scenarios (stage IIIB/IV NSCLC); and (3) the participant's views on treatment guidelines and health services research (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). Contemporaneous treatment recommendations for NSCLC during the interview time frame were published in version 5.2017 of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.22 Responses from all 3 sections were analyzed via inductive reasoning.23,24 Seven researchers individually reviewed all interview transcripts and generated codes to categorize recurring content. Team members then convened to review the interview data using conventional content analysis.25 Consensus codes were developed to represent thematic elements pertaining to surgical decision-making for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC, with theoretical constructs being developed using the grounded theory method. It was typical for >50% of the research team to be in agreement when reaching consensus. Participants were recruited until the research team determined that thematic saturation was achieved, defined as the absence of newly emerging themes alongside the regular appearance of previously noted constructs.21 Data analysis was organized using NVivo 12 (QSR International).

Results

Among the 27 cardiothoracic surgeons interviewed in this study, the majority were ≤50 years old (n = 19) and male (n = 15) (Table 1). In this cohort, 13 participants had been in practice for 0-10 years, 10 participants for >10-20 years, 3 participants for >20-30 years, and 1 participant for >30 years. Most participants reported that they practiced in an academic setting (n = 18), had a focus in general thoracic surgery (n = 23), and attended weekly tumor board (n = 21). A minority of participants (n = 10) were practicing at a National Comprehensive Cancer Network member institution at the time of the interview. Five major themes pertaining to the complex dynamics of surgical decision-making were discovered after thorough review of the interview data. Each theme is supported by quotes from interviews.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cardiothoracic surgeon interview participants

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Participants (total) | 27 (100) |

| Age, y | |

| <35 | 1 (3.7) |

| 35-50 | 18 (66.7) |

| >51 | 8 (29.6) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 15 (55.6) |

| Female | 12 (44.4) |

| Years in practice | |

| 0-10 | 13 (48.2) |

| >10-20 | 10 (37.0) |

| >20-30 | 3 (11.1) |

| >30 | 1 (3.7) |

| Practice type | |

| Academic | 18 (66.7) |

| Mixed | 2 (7.4) |

| Other | 7 (25.9) |

| National Comprehensive Cancer Network | |

| Member institution | 10 (37.0) |

| Nonmember institution | 17 (63.0) |

| Clinical focus | |

| General thoracic | 23 (85.2) |

| Nongeneral thoracic | 4 (14.8) |

| Tumor board attendance | |

| Weekly | 21 (77.8) |

| Biweekly | 4 (14.8) |

| Monthly | 1 (3.7) |

| Other | 1 (3.7) |

Theme 1. Surgeons Who Make the Decision to Operate When It Deviates From Guideline-Based Recommendations Often Do So Not Because They Are Unaware of Them, but Rather Because They Disagree With or Recognize the Limitations of These Guidelines

Participants expressed that treatment guidelines provide a reasonable framework to direct surgical decision-making for most patients with NSCLC; however, participants also acknowledged that it may be appropriate to deviate from guideline recommendations for unique patient presentations (Table 2). While offering guideline-concordant care for most patients with NSCLC, one surgeon indicated a readiness to offer nonguideline-concordant care “when the patient comes in with a scenario that [is] a little bit unusual or doesn't fit into [an] established treatment paradigm.” Another participant shared this perspective, suggesting that guidelines should not be viewed as “the rule or the law” and that surgeons must instead exercise “clinical judgment” for patients with NSCLC cases that deviate from the norm. Nevertheless, participants were also quick to highlight the value of guidelines, describing the recommendations as “very well thought out,” “evidence-based,” and “reasonable.” In this way, surgeons were supportive of offering guideline-concordant treatment but emphasized that recommendations fail to encompass the full spectrum of appropriate surgical options for patients with unusual presentations. As one provider described it, “most patients should be treated with guideline-concordant care” but not all patients “[fit] into a nice little category all the time.”

Table 2.

Surgeons’ perceived limitations in treatment guidelines

| Theme 1. Surgeons who make the decision to operate when it deviates from guideline-based recommendations often do so not because they are unaware of them, but rather because they disagree with or recognize the limitations of these guidelines. | |

|---|---|

| Interpretation | Examples |

| NCCN guidelines may not reflect all options for surgical management of patients with advanced-stage NSCLC. | “Nine out of ten times, I think we're offering guideline-concordant care. It's when the patient comes in with a scenario that [is] a little bit unusual or doesn't fit into [an] established treatment paradigm where we get away from using NCCN guidelines.” |

| “In general, the NCCN guidelines […] are very well thought out […] For the most part, I try to follow guidelines as much as I can. You know, no doubt there are times where you know they are guidelines, so they're not the rule or the law—so you still have to have your clinical judgment.” | |

| “I think that most patients should be treated with guideline-concordant care. They're very well thought out evidence-based guidelines. That said, not everyone fits into a nice little category all the time where you can say, ‘You have X, you get Y, and your outcome is going to be Z.’” | |

| “I used to sit on the NCCN, so I was part of the folks that made those guidelines […] In general, I think they are reasonable guidelines to follow. There's a lot of nuance about the construction of these guidelines. I mean, most of them are recommendations from […] groups that treat a lot of cancer, so it's not unreasonable, but they're guidelines—they're not something that's set in stone.” | |

Interview responses revealed that surgeons perform nonguideline concordant operations with acknowledgement of NCCN guideline limitations. This theme is supported by quotes from participant interviews. NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer.

Theme 2. Surgeons Indicate They Would Be Open to Operating on Patients for Whom They Would Not Offer Surgery if a Relevant Clinical Trial Protocol Were Available

Surgeons who were hesitant to offer resection for patients presented in the hypothetical clinical scenarios expressed willingness to perform the operation if conducted under a clinical trial protocol (Table 3). One participant noted such a surgery would be feasible only if “I had a protocol and if that was something like an envelope we were trying to push or at least we were trying to study.” Another indicated that a nonevidence-based resection would need to provide some degree of scientific value, stating it could be considered “only on a study protocol, so that it’s not being done in a cowboy fashion—but actually advancing our understanding and knowledge.” Contemplating resection for a patient with multistation N2 disease, one participant stated more explicitly, “I think it's totally justifiable to do it under protocol, but […] I don't think it's justifiable for me to do it out of protocol.” Collectively, these statements suggest that study protocols offer critical justification for surgeons to operate in the absence of expected therapeutic benefit. Aptly summarizing the ethical concerns of such resections, one participant stated bluntly, “I can't justify doing it off protocol […] because it's not standard of care.”

Table 3.

Surgeons are more open to performing controversial resections under protocol

| Theme 2. Surgeons indicate they would be open to operating on patients for whom they would not offer surgery if a relevant clinical trial protocol were available. | |

|---|---|

| Interpretation | Examples |

| Surgeons feel more justified performing nonevidence-based resections in the context of a clinical trial protocol. | “I would say we don't know there's benefit; there's no data to show that. We don't know that there isn't, but that's where I can't justify doing it off protocol. If I had a protocol and if that was something like an envelope we were trying to push or at least we were trying to study, […] I would have offered it to her in a heartbeat, but we don't. And so, I couldn't justify doing that […] It would be, on some level, a malpractice because it's not standard of care.” |

| “I would say that the recommended treatment is chemotherapy alone and that surgery would not routinely be used. […] [I would consider] surgical intervention only on a study protocol, so that it’s not being done in a cowboy fashion—but actually advancing our understanding and knowledge while potentially providing him some benefit but with no guarantees.” | |

| “I might even contemplate [surgical resection] if she had multi-station N2 disease […] Assuming that the mediastinal disease is now negative […] I think it's totally justifiable to do it under protocol, but we don't have such a protocol here. So, I don't think it's justifiable for me to do it out of protocol.” | |

| “By NCCN guidelines, this patient is not a surgical candidate for resection or for cure. There is a novel therapy […] under a protocol, we would do a right lower lobectomy, do a pleurectomy, and do a hyperthermic pleural lavage […] There's very little data on that. There have actually been a couple of studies that were actually negative, but it is probably the only therapy that has any chance at all of giving this young man a chance at survival.” | |

Interview responses revealed that surgeons feel more comfortable performing controversial resections under a clinical trial protocol. This theme is supported by quotes from participant interviews. NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Theme 3. Surgeons Believe Resection Is Often Not Considered as a Treatment Option Due to an Overestimation of Surgical Morbidity or Incomplete Understanding of Surgical Capabilities Among Colleagues in Other Disciplines

Participants perceived some nonsurgical colleagues as having an incomplete understanding of modern surgical capabilities, which ultimately precludes deliberation of surgical intervention for patients who may benefit from resection (Table 4). One surgeon explained, “There's nothing more frustrating than having a patient be told that they're not a surgical candidate by their primary care doctor or their medical oncologist.” Another participant hypothesized that nonsurgical colleagues who never refer patients for surgery believe they are ensuring surgeons “[do not] hurt their patients by doing surgery,” even though the surgical team would have considered these patients to be good surgical candidates had they been evaluated. To overcome this barrier, surgeons indicated that it is critical to educate nonsurgical colleagues and promote appropriate discussion about surgical intervention. As one participant explained, addressing this issue requires “educating the group about what is surgically possible” and that “it takes a surgeon to really say that, ‘This, I can take out. That, I can't take out.’”

Table 4.

Surgeons perceive incomplete understanding of surgical scope among nonsurgeon physicians

| Theme 3. Surgeons believe surgery is often not considered as a treatment option due to an overestimation of surgical morbidity or incomplete understanding of surgical capabilities among colleagues in other disciplines. | |

|---|---|

| Interpretation | Examples |

| Surgeons believe they need to educate nonsurgical colleagues regarding patients' true surgical candidacy. | “There are other oncologists who never ever send patients to us, even ones that—had we seen them—we would have said that they were surgical candidates. They thought that they knew what a good surgical candidate was and preferred to make that decision for us so that we didn't hurt their patients by doing surgery.” |

| “A lot of it is educating the group about what is surgically possible […] It takes a surgeon to really say that, ‘This, I can take out. That, I can't take out.’ To have the radiation oncologist or the medical oncologist or the pulmonologist making that decision basically undertreats a lot of patients because they overestimate the morbidity of surgery.” | |

| “Particularly in the stage 3 and 4 patients, I think a lot of those patients get treated with chemotherapy and radiation […] without a surgeon's opinion […] Surgeons are [commonly] not involved in the decision-making for stage 3 and 4 patients unless there's a specific question—it's identified by an oncologist or radiation oncologist that maybe we should get surgery to see it. In that case, it's harder to control because then you have to educate your medical oncologist and radiation oncologist.” | |

| “There's nothing more frustrating than having a patient be told that they're not a surgical candidate by their primary care doctor or their medical oncologist […] There's that level of understanding about the nuances of lung surgery that those people have no concept about […] There's those nuances that I think academic surgeons may have a better handle on.” | |

Interview responses revealed that surgeons believe therapeutic resection is underused often due to an inaccurate understanding among nonsurgeon colleagues regarding surgical capabilities or expected morbidity. This theme is supported by quotes from participant interviews.

Theme 4. When Deciding if They Will Offer Surgery, Surgeons Consider Not Only the Risks and Benefits for the Patient at Hand but Also How This Decision Will Impact Professional Trust and Relationships With Their Colleagues

Participants indicated that they consider the impacts their surgical decisions may have on long-term interprofessional relationships (Table 5). Surgeons expressed apprehension that performing controversial resections would compromise their reputation and fracture trust with colleagues. One participant noted that surgeons who develop a reputation for operating “with little discrimination as to who is appropriate” ultimately lead their colleagues in medical and radiation oncology to “filter who they actually let get to [the surgeons'] door,” to protect patients from perceived recklessness. However, participants also indicated that earning a reputation as a thoughtful decision-maker could have an inverse, beneficial effect on professional relationships. One surgeon described how colleagues are “much more willing to have the conversation about the benefit of the patient instead of being constantly focused on the surgical risk to the patient,” if the individual is known as a judicious surgeon. Another participant echoed this sentiment, stating, “If you are careful in your assessment and you are clear […] about the elements that were considered in your decision-making,” then colleagues “begin to trust that you are using evidence” and “trust that you'll do the right thing.”

Table 5.

Surgeons consider the impact of surgical decisions on professional relationships

| Theme 4. When deciding if they will offer surgery, surgeons consider not only the risks and benefits for the patient at hand, but how this decision will impact professional trust and relationships with their colleagues. | |

|---|---|

| Interpretation | Examples |

| Surgeons are reluctant to perform controversial resections that may compromise the trust colleagues have in them. | “Part of dealing with that is making good decisions about who we operate on and not thinking that we can get anybody through anything, because that's obviously not true. I would say if people know that about you, then they are much more willing to have the conversation about the benefit of the patient instead of being constantly focused on the surgical risk to the patient.” |

| “One of my mentors was […] definitely a proponent of offering people radical surgery because he felt they didn't have other options […] Certainly, I think that that thinking can get you into trouble […] I think other surgeons might feel that I was being reckless or risky […] Some med-onc providers I think would be concerned that I would be ‘killing their patients’.” | |

| “If you are careful in your assessment and you are clear […] about the elements that were considered in your decision-making as far as whether they could be operated on or not—and you document your conversation with the patient well—I think people begin to trust that you are using evidence […] and patient-specific variables to make those decisions. It's going to be a much more collaborative process and you will be able to participate in a broader spectrum of patients because they'll trust that you'll do the right thing as far as understanding if the patient is too risky or not.” | |

| “In a situation where you have a surgeon that operates on everyone who walks through their door with little discrimination as to who is appropriate or not, I think the medical and radiation oncologists will begin to filter who they actually let get to your door.” | |

Interview responses revealed that surgeons reflect on the potential effects on professional relationships when considering a controversial resection. This theme is supported by quotes from participant interviews. Med-onc, Medical oncology.

Theme 5. Even When They Believe Resection Will Offer No Benefit, Surgeons Face Pressure to Offer Surgery to Preserve Hope for Patients Who View It as a Favorable Treatment Option and/or Those Who Have No Therapeutic Alternatives

Participants shared that they experience profound emotional pressure to offer surgery, even for patients with low expectation of benefit from resection (Table 6). Describing a previous patient experience, one participant recounted, “She was bawling and kept screaming at me to take it out. But I mean, I honestly debated doing it […] because it was [so] heart-wrenching.” At the core of this emotional turmoil, as one surgeon explained, is that “patients view surgery relatively favorably” and that it “can be quite psychologically devastating to patients” when resection is not a viable treatment option. Another participant contemplated the extent to which patients’ wishes should “push [surgeons] in one direction or another” with respect to surgeries that have no evidentiary basis but would not be classified as “egregious professional practices.” When choosing not to offer resection, surgeons are therefore challenged both with acknowledging their own sense of powerlessness and with preserving hope in patients for whom a psychologically favorable treatment option has been deemed unviable.

Table 6.

Surgeons contend with emotional pressure to offer resection

| Theme 5. Even when they believe resection will offer no benefit, surgeons face pressure to offer surgery to preserve hope for patients who view it as a favorable treatment option and/or those that have no therapeutic alternatives. | |

|---|---|

| Interpretation | Examples |

| Deciding not to offer surgery can cause significant emotional burden for surgeons. | “You don't want him to die, but you can't operate on him […] It's just the worst thing because you can't be on his team […] You can't save him with your scalpel […] You feel like a limp noodle, like the most impotent, helpless feeling in the world.” |

| “For the most part, patients view surgery relatively favorably […] It can be quite psychologically devastating to patients when you say, ‘you're not a candidate for surgery because you're just medically unfit’ or ‘I think surgery is not going to help you.’” | |

| “Sometimes there are things where you say, ‘I don't really feel good about this. I don't think it's a good idea. The evidence is kind of pointing me away from doing it’—but you would not necessarily be […] classified as being engaging in egregious professional practices for doing it. So, you have that: Based on the evidence and experience, it's probably not a good idea. To what extent will a patient's desires—after explaining everything—push you in one direction or another?” | |

| “When she woke up from her [mediastinoscopy], she knew immediately because she didn't have any chest pain [that] she didn't have the resection. Literally spent the entire rest of the day […] crying with her. She was bawling and kept screaming at me to take it out. But I mean, I honestly debated doing it […] because it was [so] heart-wrenching.” | |

Interview responses revealed that surgeons are often pressured to offer surgical resection for patients for whom there is no expected therapeutic benefit. This theme is supported by quotes from participant interviews.

Discussion

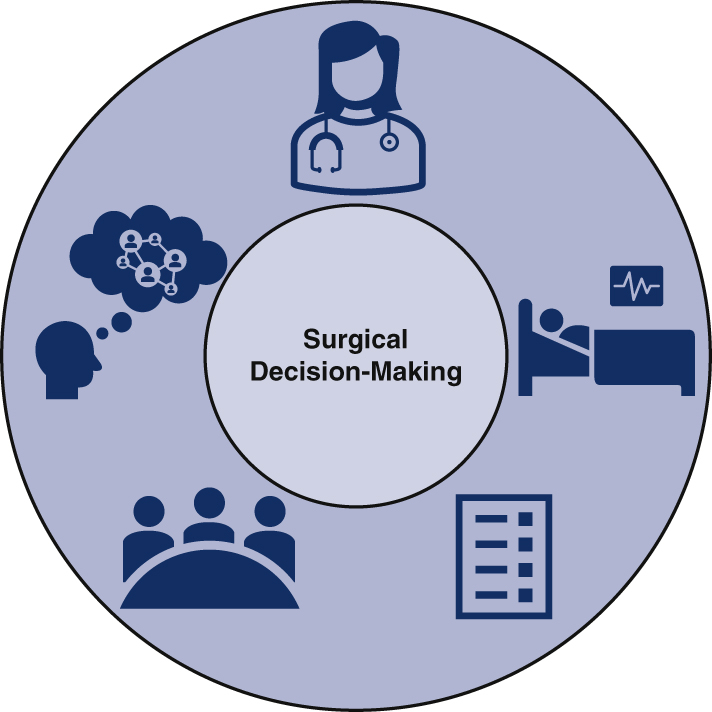

Our study demonstrates that multiple individual and interpersonal factors influence whether cardiothoracic surgeons choose to offer curative-intent resection for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC (Figure 1 and Video 1). As with any procedure, surgeons must first evaluate several essential elements, including but not limited to the expected risks and benefits according to current literature, the patient's anticipated ability to tolerate the intervention, and the patient's wishes regarding treatment.26 Risk calculators and patient-facing tools, while far from standalone solutions, are meant to facilitate shared decision-making by addressing these factors.15 However, this study reveals that surgical decision-making in the context of advanced-stage NSCLC is impacted by complexities far beyond identifying the guideline-concordant treatment, assessing surgical candidacy, and discussing a singular plan with patients. When unique patient presentations fall beyond the scope of current guidelines, surgeons are left with ambiguous clinical scenarios and difficult decisions.

Figure 1.

Surgical decision-making for patients with advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer is influenced by a complex network of factors.

Clinical judgment may indeed represent the core of a surgeon's thought processes, but whether surgery is offered may be profoundly influenced by fears of unintended consequences such as fracturing long-term trust with colleagues and thereby hindering future patient care. Surgeons frame these decisions with the knowledge that developing a reputation for being “reckless or risky” will cause nonsurgeon providers to “filter” who they refer to surgery as a means of protecting patients (Theme 4). The capacity for relationships with colleagues to influence treatment decisions has been described in oncology, but the interdisciplinary dynamics involved in surgical decision-making for advanced-stage NSCLC have yet to be explored.27 It is also possible surgeons fear they will inadvertently aggravate inaccurate and negative perceptions of surgery among nonsurgeon colleagues (Theme 3) if patients experience poor outcomes after controversial resections.

In this way, the constructs described in Theme 3 and Theme 4 may be intertwined in that surgeons contemplating controversial resections believe they risk not only their own professional reputation but confidence in surgeons more broadly. Perhaps the oncologists who “thought that they knew what a good surgical candidate was and preferred to make that decision” developed a negative bias after perceiving irresponsible conduct in surgeons predating the interviewee who shared this observation. While surgeons acknowledge the importance of educating colleagues about “what is surgically possible” to ensure all patients are appropriately evaluated for therapeutic resection, they may also experience an added responsibility to improve perceptions of surgery as a field by consistently making “good decisions about who we operate on and not thinking that we can get anybody through anything.” These conversations can be especially challenging in the context of advanced-stage NSCLC where the definition of resectable disease can be unclear and highly variable between institutions.28 This implicit charge to simultaneously consider the current patient, the trust of colleagues, and the reputation of the field may be a subconscious but heavy burden that increases the complexity of decision-making for surgeons evaluating and treating patients with advanced-stage NSCLC.

In contrast, some participants described clinical trial protocols as providing surgeons with critical justification when offering resections without proven benefit (Theme 2). One surgeon suggested that study protocols ensure surgeries will at least contribute to medical knowledge, even with “no guarantees” of benefit for the patients. This participant also explained that clinical trial protocols indicate the resections are “not being done in a cowboy fashion,” implying an apprehension of otherwise appearing heedless or overaggressive. The image of the “cowboy surgeon” is far from romanticized in this context, with one participant characterizing an unproven resection as, “on some level, a malpractice.” In this way, study protocols may provide surgeons with some comfort when offering nonevidence-based resections by reducing the risk of compromising colleagues’ trust in their clinical judgment (Theme 4) or exacerbating negative perceptions of surgery more broadly (Theme 3). For patients and their families, the decision to participate in a clinical trial may be influenced by factors such as perceived risk of the intervention, understanding of the procedure, and trust in the healthcare team.29

Furthermore, clinical trial protocols may allow surgeons to avoid the emotional burden of denying surgery to patients who have unresectable disease but still view resection as their best chance for cure. Surgeons can experience tremendous guilt when choosing not to offer surgery and feel as though they are extinguishing a patient's already waning hope (Theme 5), whereas clinical trial protocols provide an opportunity to preserve optimism; lamenting the absence of a relevant study protocol, one participant stated, “I would have offered [surgery] to her in a heartbeat, but we don't [have one].” Nevertheless, it is critical to acknowledge that surgeons may not consider surgery to be the best option for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC, even if relevant clinical trial protocols were available.

This study has several limitations, including those inherent to qualitative methodologies. A specific challenge associated with conventional content analysis is the potential failure to understand the full context of participant responses. In this study, a single professional interviewer with dedicated training in qualitative research methods used to standardize the format and quality of the interviews, posing additional questions to ensure sufficient context for participant responses. Furthermore, member-checking methods were used to ensure interpretations of participant responses appropriately considered the context of the discussion from which the representative quotation was extracted. Given that the interviews were performed between December 1, 2017, and April 30, 2018, it is possible that certain themes have grown less relevant with the evolution of evaluation and treatment practices since these conversations first took place. The PACIFIC trial is a notable example of such recent advancement in the lung cancer research domain; simultaneously, its impact on surgical decision-making and on the validity of the themes uncovered in the present study is uncertain, particularly when considering the questions that have been raised with respect to how unresectability was defined in this trial.30

Certain aspects of our study represent differences in the intrinsic goals of qualitative versus quantitative research and therefore may be better described as perceived, rather than true, limitations. For example, a common criticism of qualitative research is the use of small sample sizes. However, a smaller number of participants is necessary for researchers to comprehensively examine thought processes and social constructs, which is the core objective of qualitative research; in this way, a larger group of participants may have detracted from a thorough study of the selected population.21 Rather than rely on a predetermined sample size, recruitment was appropriately continued until thematic saturation was achieved. In addition, we elected not to use the procedures outlined in the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ), which have been described as overly reductionist and antithetical to the purpose of qualitative research without the benefit of added rigor.21,23,31, 32, 33

While questions of generalizability are often raised regarding qualitative research, the objective of this methodology is to examine thematic elements in a well-defined group at a specific point in time. With recruitment occurring primarily via ThORN, the limited diversity among participants impedes the generalizability of the findings described in this study to a general population. However, these findings can be generalized to a population similar to the study participants, ie, those practicing in tertiary or quaternary settings. Thus, the present study may have benefitted from greater representation from surgeons who are >50 years old, practice in nonacademic settings, and do not have a general thoracic focus, but the constructs uncovered in the recruited sample remain valid nonetheless. Elfenbein and Schwarze23 described this concept poignantly, noting that qualitative research seeks to achieve resonance as opposed to generalizability. Readers can evaluate whether the constructs presented in qualitative literature are relevant for other populations, and investigators can subsequently employ quantitative methods to assess theories proposed in these studies.34 Acknowledging that qualitative research is hypothesis-generating, rather than hypothesis-testing, is critical for understanding and assessing its value in creating opportunity for future research.

Conclusions

Surgical decision-making for resection of the primary tumor presents profound challenges for cardiothoracic surgeons evaluating patients with advanced-stage NSCLC. This qualitative study generates the hypothesis that a surgeon's willingness to offer curative-intent surgery for patients with advanced-stage NSCLC is influenced by the scope of current treatment guidelines, perceived nonsurgeon understanding of modern surgical capabilities, availability of relevant study protocols, interprofessional relationship dynamics, and the emotional pressure to preserve hope for patients who wish to have surgery. These factors, both individually and as part of a complex network, ultimately require further evaluation using quantitative methods to characterize their impact on clinical practice. Specifically, it is critical to develop an objective understanding of how often the 5 themes described in this study result in changes to surgical treatment decisions and what provider or patient-level factors are predictive of such changes. Future research will use survey-based models and focus groups to investigate how readily physicians, including surgeons, medical oncologists, etc, deviate from the treatment plans most consistent with their independent clinical judgment and current guidelines due to social pressures from patients and colleagues. In addition, a follow-up survey of the same 27 participants interviewed in this study could offer a valuable investigation of changes in perspectives over time. In considering the findings of the present qualitative study, surgeons may seek to reflect on the impact these factors may have in their own decision-making process; by striving to maintain an active awareness of the potential implications in their unique practice setting, surgeons may help to reduce undue influence on treatment decisions. Surgical decision-making in such complex scenarios can likely be improved not only by gaining experience at the provider-level but by facilitating family discussions and seeking input from senior partners. By developing a quantitative understanding of how specific interpersonal factors influence surgical decision-making, continued research will provide a critical educational framework to promote appropriate surgical evaluation and treatment for all patients with advanced-stage NSCLC.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

The Journal policy requires editors and reviewers to disclose conflicts of interest and to decline handling or reviewing manuscripts for which they may have a conflict of interest. The editors and reviewers of this article have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix 1. Interview Script

Next, I am going to ask for to consider several hypothetical scenarios. Please remember that there is no single right answer. I am interested in your professional opinion as a thoracic surgeon who might be involved with the care of the patient we describe in each situation.

Please look at slide 2 of the PDF file we sent you.

Scenario #1: Within Guidelines (5 Minutes)

Logan is a 62-year-old man. He has a T1aN0M1b right middle lobe adenocarcinoma with a biopsy proven right adrenal metastasis and no other known site of disease. His magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is negative for metastasis. His performance status is excellent and therapy. physiologically he would tolerate lobectomy. You are asked to offer an opinion on surgical therapy.

-

1.What would your recommendation be for this patient and how would you justify your recommendation?

-

a.Is there other information that you would need to know about this patient that would influence your decision? What might that be?

-

b.If they don't offer surgery: Is there any scenario in which you would recommend surgery for this patient?

-

a.

Scenario 2: Bone Metastases (8 Minutes)

The second scenario is about a 68-year-old woman named Jamie. She has a T1bN0M1b right upper lobe adenocarcinoma with 5 bone metastases that are all <1 cm. Her MRI of the brain is negative for metastasis. Her performance status is excellent and physiologically she would tolerate lobectomy or pneumonectomy. You are asked to offer an opinion on surgical therapy.

-

1.What would your recommendation be for this patient and how would you justify your recommendation?

-

a.If they don't bring up tumor board: Would you present this case at tumor board?

-

b.Is there other information that you would need to know about this patient that would influence your decision? What might that be?

-

c.If they don't offer surgery: Is there any scenario in which you would recommend surgery for this patient?

-

a.

-

2.What might be some benefits of lung resection for this patient?

-

a.How do these influence your recommendation?

-

a.

-

3.What are the harms of lung resection for this patient?

-

a.How do these influence your recommendation?

-

a.

Scenario #3: Stable Disease After 1 Year of Systemic Therapy (8 Minutes)

The third scenario is about a 72-year-old woman named Pat. She was diagnosed with a T2aN3M0 left upper lobe adenocarcinoma 14 months ago. Her MRI of the brain is negative for metastasis. Her performance status is fine and physiologically she would tolerate lobectomy or pneumonectomy. She was treated with chemoradiation and has been on maintenance therapy for the last 12 months. Her nodal disease has resolved on positron emission tomography/computed tomography, but there is persistent uptake in her Left upper lobe tumor. Her case is presented at thoracic tumor board and you are asked to offer an opinion on surgical therapy.

-

1.What would your recommendation to the tumor board be?

-

a.If surgery not recommended: Is there any scenario in which you would recommend surgery for this patient?

-

b.Is there any other information you would need about this patient that might influence your recommendation?

-

c.How does the type of resection required weigh into your decision to offer surgery?

-

a.

-

2.What are benefits of lung resection for this patient?

-

a.How do these influence your recommendation?

-

a.

-

3.What are the harms of lung resection for this patient?

-

a.How do these influence your recommendation?

-

a.

-

4.What would you tell the patient about the potential survival benefit of surgery?

-

a.Keeping the guidelines in mind, what would you tell the patient about her case and what her options are?

-

a.

-

5.

How do you think colleagues from other disciplines (medical oncology, radiation oncology) would react to your recommendation?

Scenario #4: Pleural Metastases (12 Minutes)

The fourth scenario is about a 45-year-old man named Taylor. He was diagnosed with a T2aN0M1a right lower lobe adenocarcinoma; he has a right pleural effusion which is positive for adenocarcinoma, and he has several focal areas of right pleural thickening. He never smoked and was a division 1 athlete in college. His MRI of the brain is negative for metastasis. His performance status is excellent and physiologically he would tolerate lobectomy or pneumonectomy. He has sought multiple opinions from various centers and wants to have surgery as part of his treatment regimen. His case is presented at thoracic tumor board and you are asked to offer an opinion on surgical therapy.

-

1.

What would your recommendation to the tumor board be?

-

2.Is there any scenario in which you would recommend surgery for this patient?

-

a.What are the benefits or harms of lung resection for this patient?

-

b.What would you tell the patient about the potential benefits of having surgery?

-

c.What would you tell the patient about how his case fits within the current guidelines?

-

d.Keeping the guidelines in mind, what would you tell the patient about his case and what his options are?

-

e.How does the type of resection required weigh into your decision to offer surgery?

-

a.

Appendix 2. Theme 1. Surgeons Who Make the Decision to Operate When it Deviates From Guideline-Based Recommendations Often Do So Not Because They Are Unaware of Them, but Rather Because They Disagree With or Recognize the Limitations of These Guidelines

Initial Set of Representative Quotations:

-

•

“Nine out of ten times, I think we're offering guideline-concordant care. It's when the patient comes in with a scenario that [is] a little bit unusual or doesn't fit into [an] established treatment paradigm where we get away from using National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines.”

-

•

“In general, the NCCN guidelines […] are very well thought out […] For the most part, I try to follow guidelines as much as I can. You know, no doubt there are times where you know they are guidelines, so they're not the rule or the law—so you still have to have your clinical judgment.”

-

•

“I think that most patients should be treated with guideline-concordant care. They're very well thought out evidence-based guidelines. That said, not everyone fits into a nice little category all the time where you can say, ‘You have X, you get Y, and your outcome is going to be Z.’”

-

•

“I used to sit on the NCCN, so I was part of the folks that made those guidelines […] In general, I think they are reasonable guidelines to follow. There's a lot of nuance about the construction of these guidelines. I mean, most of them are recommendations from […] groups that treat a lot of cancer, so it's not unreasonable, but they're guidelines—they're not something that's set in stone.”

-

•

“You either need to educate them or you need to come out with better guidelines that people can follow. It's not clear that guidelines are going to matter because it's not clear that anyone actually follows them.”

-

•

“The NCCN guidelines that suggest patients with IIIA and IIIB disease should be considered for just chemo-rads I think are not accurate, and the trials do suggest that there is benefit to offering surgery for some patients.”

-

•

“I think that if techniques like video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery aren't coming on mainline and sort of taking on 90% or 75% dominance in the country, then it's hard to imagine that people are going to be willing to change their feelings about IIIB disease because some society says so […] If people really were willing to do that, then I think [the conclusion] would be: Surgeons uniformly say they would change their practice patterns, so the onus is on the societies to come up with better guidelines […] If surgeons don't care about the guidelines, then the onus is on surgical education–not on guidelines, right?”

-

•

“Certain outcomes data can certainly help drive better understanding of guidelines–or knowing when there are gaps in the guidelines, [recognizing when] guidelines fall short, or clarifying certain parts of the guidelines.”

-

•

“It represents a violation of all surgical oncologic guidelines, but the tension is between the personal commitment to an individual patient and the overly aggressive application of surgery when there's really no good chance for cure. Because it sometimes leads to longer disease-free intervals, we keep doing it.”

Theme 2. Surgeons Indicate They Would Be Open to Operating on Patients for Whom They Would Not Offer Surgery if a Relevant Clinical Trial Protocol Were Available

Initial Set of Representative Quotations:

-

•

“I would say we don't know there's benefit; there's no data to show that. We don't know that there isn't, but that's where I can't justify doing it off protocol. If I had a protocol and if that was something like an envelope we were trying to push or at least we were trying to study, […] I would have offered it to her in a heartbeat, but we don't. And so, I couldn't justify doing that […] It would be, on some level, a malpractice because it's not standard of care.”

-

•

“I would say that the recommended treatment is chemotherapy alone and that surgery would not routinely be used. […] [I would consider] surgical intervention only on a study protocol, so that it’s not being done in a cowboy fashion–but actually advancing our understanding and knowledge while potentially providing him some benefit but with no guarantees.”

-

•

“I might even contemplate [surgical resection] if she had multistation N2 disease […] Assuming that the mediastinal disease is now negative […] I think it's totally justifiable to do it under protocol, but we don't have such a protocol here. So, I don't think it's justifiable for me to do it out of protocol.”

-

•

“By NCCN guidelines, this patient is not a surgical candidate for resection or for cure. There is a novel therapy […] under a protocol, we would do a right lower lobectomy, do a pleurectomy, and do a hyperthermic pleural lavage […] There's very little data on that. There have actually been a couple of studies that were actually negative, but it is probably the only therapy that has any chance at all of giving this young man a chance at survival.”

-

•

“If there were colleagues that I knew had protocols running […] I would 100% offer that—offer to refer them to those facilities or […] facilitate getting them enrolled in a protocol.”

Theme 3. Surgeons Believe Surgery Is Often Not Considered as a Treatment Option Due To an Overestimation of Surgical Morbidity or Incomplete Understanding of Surgical Capabilities Among Colleagues in Other Disciplines

Initial Set of Representative Quotations:

-

•

“There are other oncologists who never ever send patients to us, even ones that—had we seen them—we would have said that they were surgical candidates. They thought that they knew what a good surgical candidate was and preferred to make that decision for us so that we didn't hurt their patients by doing surgery.”

-

•

“A lot of it is educating the group about what is surgically possible […] It takes a surgeon to really say that, ‘This, I can take out. That, I can't take out.’ To have the radiation oncologist or the medical oncologist or the pulmonologist making that decision basically undertreats a lot of patients because they overestimate the morbidity of surgery.”

-

•

“Particularly in the stage 3 and 4 patients, I think a lot of those patients get treated with chemotherapy and radiation […] without a surgeon's opinion […] Surgeons are [commonly] not involved in the decision-making for stage 3 and 4 patients unless there's a specific question—it's identified by an oncologist or radiation oncologist that maybe we should get surgery to see it. In that case, it's harder to control because then you have to educate your medical oncologist and radiation oncologist.”

-

•

“There's nothing more frustrating than having a patient be told that they're not a surgical candidate by their primary care doctor or their medical oncologist […] There's that level of understanding about the nuances of lung surgery that those people have no concept about […] There's those nuances that I think academic surgeons may have a better handle on.”

-

•

“The pulmonologist said, ‘Hey, here's this guy with this tumor. It involves the carina, so it involves an area where a lot of surgeons would not resect and would have been declared unresectable in a lot of programs.’ I looked at the information that was available and said […], ‘He's a candidate for surgery physiologically; he has a tumor that [complete resection of] is likely to improve his chances of cure; and he will require a pretty good-sized operation […] but that's something I can do surgically.’”

-

•

“It depends on how educated [colleagues from medical or radiation oncology] are; how much lung cancer they've treated; what they've seen their surgeons do or not do; or what kind of mayhem they've seen. So, if what they've seen is, ‘Gee, my surgeon takes everyone to lobectomy. They infarcted. They have all kinds of problems […]’ They're not going to be very interested [in surgery].”

-

•

“If [the question is]: Why are people, in general, not operating on what most of us would consider straight-forward? Every surgeon says they should do it and they're not getting it, that means that we need to target the oncologist or the pulmonologist.”

-

•

“If there is a surgeon present at those [multidisciplinary] groups who is vocal about what they are capable of doing, describes their results […] [If] they're able to bring that kind of data to the table, then I think those groups are much more likely to be enthusiastic for surgical therapy.”

Theme 4. When Deciding if They Will Offer Surgery, Surgeons Consider Not Only the Risks and Benefits for the Patient at Hand but Also How This Decision Will Impact Professional Trust and Relationships With Their Colleagues

Initial Set of Representative Quotations:

-

•

“Part of dealing with that is making good decisions about who we operate on and not thinking that we can get anybody through anything, because that's obviously not true. I would say if people know that about you, then they are much more willing to have the conversation about the benefit of the patient instead of being constantly focused on the surgical risk to the patient.”

-

•

“One of my mentors was […] definitely a proponent of offering people radical surgery because he felt they didn't have other options […] Certainly, I think that that thinking can get you into trouble […] I think other surgeons might feel that I was being reckless or risky […] Some medical oncology providers I think would be concerned that I would be ‘killing their patients’.”

-

•

“If you are careful in your assessment and you are clear […] about the elements that were considered in your decision-making as far as whether they could be operated on or not–and you document your conversation with the patient well—I think people begin to trust that you are using evidence […] and patient-specific variables to make those decisions. It's going to be a much more collaborative process and you will be able to participate in a broader spectrum of patients because they'll trust that you'll do the right thing as far as understanding if the patient is too risky or not.”

-

•

“In a situation where you have a surgeon that operates on everyone who walks through their door with little discrimination as to who is appropriate or not, I think the medical and radiation oncologists will begin to filter who they actually let get to your door.”

-

•

“In a community [practice], you get fed by your people at tumor board. So, you have to be a little careful about how you talk about their opinions. I mean, ultimately, honestly, what you do is you kind of feed them what they want to hear […] In academics […] a lot of people have to consider, ‘Hey, that oncologist may never send me another patient again if I say blippity-blip.’”

-

•

“I was faculty at [institution] for almost ten years, and if you did any outside of the box thinking other than what was in the literature, they just thought you were like two-headed […] I mean, basically, they just followed party lines. And if you offered anything outside of that, you weren't really looked at very kindly.”

-

•

“At our tumor board, I think they would take [my recommendation to operate] reasonably well, but I think that's because we have a pretty good working relationship. I would say it exactly like I did—that it’s definitely outside of the box—and I would only do it if the multidisciplinary group thought it was a reasonable idea.”

-

•

“I think every one of these patients needs to go to a tumor board because you need everybody to buy in […] Even if […] I had this super strong view that this is the right thing to do, I think it has to go to tumor board. Your oncologist has to agree.”

-

•

“I would present [the patient] and then be sure that everyone clarified exactly what they meant […] I would want to get buy-in from everyone I knew.”

-

•

“Some institutions have a very overpowering, very prominent medical oncologist, so the surgeons have a hard time getting support for surgical therapy for stage IIIA versus in other places. For example, you may have a more pro-surgery medical oncologist that refers more and encourages more […] I think there's institutional variation that really plays a big role on the management of disease.”

-

•

“I think sometimes we get asked to operate not necessarily because the patient wants an operation, but because other providers are out of options or out of things to offer patients.”

-

•

“It depends on how educated [colleagues from medical or radiation oncology] are; how much lung cancer they've treated; what they've seen their surgeons do or not do; or what kind of mayhem they've seen. So, if what they've seen is, ‘Gee, my surgeon takes everyone to lobectomy. They infarcted. They have all kinds of problems […]’ They're not going to be very interested [in surgery].”

Theme 5. Even When They Believe Resection Will Offer No Benefit, Surgeons Face Pressure to Offer Surgery to Preserve Hope for Patients Who View it as a Favorable Treatment Option and/or Those Who Have No Therapeutic Alternatives

Initial Set of Representative Quotations:

-

•

“You don't want him to die, but you can't operate on him […] It's just the worst thing because you can't be on his team […] You can't save him with your scalpel […] You feel like a limp noodle, like the most impotent, helpless feeling in the world.”

-

•

“For the most part, patients view surgery relatively favorably […] It can be quite psychologically devastating to patients when you say, ‘you're not a candidate for surgery because you're just medically unfit’ or ‘I think surgery is not going to help you.’”

-

•

“Sometimes there are things where you say, ‘I don't really feel good about this. I don't think it's a good idea. The evidence is kind of pointing me away from doing it’ – but you would not necessarily be […] classified as being engaging in egregious professional practices for doing it. So, you have that: Based on the evidence and experience, it's probably not a good idea. To what extent will a patient's desires—after explaining everything—push you in one direction or another?”

-

•

“When she woke up from her [mediastinoscopy], she knew immediately because she didn't have any chest pain [that] she didn't have the resection. Literally spent the entire rest of the day […] crying with her. She was bawling and kept screaming at me to take it out. But I mean, I honestly debated doing it […] because it was [so] heart-wrenching.”

-

•

“What that means is that you're too advanced, your condition is too advanced for surgery to really help you. I'm not saying that explicitly, but that's what I mean. I don't know if patients really truly understand that's what I mean.”

-

•

“The thing is not to be pedantic or nonpatient-centered or expert-biased, but it's kind of like telling a pilot what to do. In a way, right? Patient preference is very important, but—when it's something that you shouldn't be doing—should you really be letting that influence you […] pushing you in one direction or another, right?”

-

•

“I would say all I'm going to do is hurt you. And, you know, that's hard but you've got to look him in the eye and say that you have a very, very difficult problem, and I don't have anything that's going to help you.”

-

•

“Patients with cancer are desperate people, and you can really convince them of a lot of out-of-the-box treatments–and you have to hold yourself in check. Your heart goes out to them, but your knife should not.”

-

•

“That's always something that you have to work with patients in counseling. You know, trying to make them understand that surgery is for helping people, and surgery isn't going to help him. Sometimes, that's a hard role. Generally, if you have enough people involved telling him the same thing, they'll change their thought. That's where I think it's important to have physicians that are good communicators […] I mean, eventually, they'll find a surgeon that'll operate on them, but it's not going to benefit them.”

Supplementary Data

In this video, Terrance Peng, MPH, offers a brief overview of the objective, methodology, and significant findings of the study. Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2736(22)00200-5/fulltext.

References

- 1.Howlader N., Forjaz G., Mooradian M.J., Meza R., Kong C.Y., Cronin K.A., et al. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:640–649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cancer Stat Facts: Lung and Bronchus Cancer. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raz D.J., Wu G.X., Consunji M., Nelson R., Sun C., Erhunmwunsee L., et al. Perceptions and utilization of lung cancer screening among primary care physicians. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:1856–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David E.A., Daly M.E., Li C.S., Chiu C.L., Cooke D.T., Brown L.M., et al. Increasing rates of no treatment in advanced-stage non–small cell lung cancer patients: a propensity-matched analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.11.2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel A.P., Crabtree T.D., Bell J.M., Guthrie T.J., Robinson C.G., Morgensztern D., et al. National patterns of care and outcomes after combined modality therapy for stage IIIA non–small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:612–621. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David E.A., Canter R.J., Chen Y., Cooke D.T., Cress R.D. Surgical management of advanced non–small cell lung cancer is decreasing but is associated with improved survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:1101–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2016.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bott M.J., Patel A.P., Crabtree T.D., Morgensztern D., Robinson C.G., Colditz G.A., et al. Role for surgical resection in the multidisciplinary treatment of stage IIIB non–small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:1921–1928. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.David E.A., Andersen S.W., Beckett L.A., Melnikow J., Clark J.M., Brown L.M., et al. Survival benefits associated with surgery for advanced non–small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;157:1620–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.10.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bach P.B., Cramer L.D., Warren J.L., Begg C.B. Racial differences in the treatment of early-stage lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1198–1205. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groth S.S., Al-Refaie W.B., Zhong W., Vickers S.M., Maddaus M.A., D’Cunha J., et al. Effect of insurance status on the surgical treatment of early-stage non–small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1221–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wassenaar T.R., Eickhoff J.C., Jarzemsky D.R., Smith S.S., Larson M.L., Schiller J.H. Differences in primary care clinicians' approach to non–small cell lung cancer patients compared with breast cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:722–728. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3180cc2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawe D.E., Pond G.R., Ellis P.M. Assessment of referral and chemotherapy treatment patterns for elderly patients with non–small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2016;17:563–572.e562. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goulart B.H.L., Reyes C.M., Fedorenko C.R., Mummy D.G., Satram-Hoang S., Koepl L.M., et al. Referral and treatment patterns among patients with stages III and IV non–small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:42–50. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kruser J.M., Pecanac K.E., Brasel K.J., Cooper Z., Steffens N., McKneally M., et al. “And I think that we can fix it”: mental models used in high-risk surgical decision making. Ann Surg. 2015;261:678. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kopecky K.E., Urbach D., Schwarze M.L. Risk calculators and decision aids are not enough for shared decision making. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:3–4. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor L.J., Adkins S., Hoel A.W., Hauser J., Suwanabol P., Wood G., et al. Using implementation science to adapt a training program to assist surgeons with high-stakes communication. J Surg Educ. 2019;76:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kon A.A., Davidson J.E., Morrison W., Danis M., White D.B. Shared decision-making in intensive care units. Executive summary of the American College of Critical Care Medicine and American Thoracic Society policy statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:1334–1336. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0269ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper Z., Koritsanszky L.A., Cauley C.E., Frydman J.L., Bernacki R.E., Mosenthal A.C., et al. Recommendations for best communication practices to facilitate goal-concordant care for seriously ill older patients with emergency surgical conditions. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1–6. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shemanski K.A., Farias A., Lieu D., Kim A.W., Wightman S., Atay S.M., et al. Understanding thoracic surgeons’ perceptions of administrative database analyses and guidelines in clinical decision-making. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;161:807–816.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2020.08.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim A.W., David E.A., Cooke D.T. Thoracic surgery research on a “larger” scale. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:S485. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.03.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarze M.L., Kaji A.H., Ghaferi A.A. Practical guide to qualitative analysis. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:252–253. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.4385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ettinger D.S., Wood D.E., Aisner D.L., Akerley W., Bauman J., Chirieac L.R., et al. Non–small cell lung cancer, version 5.2017, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:504–535. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2017.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elfenbein D.M., Schwarze M.L. In: Dimick J., Lubitz C., editors. Springer; 2020. Qualitative research methods; pp. 249–260. (Health Services Research. Success in Academic Surgery). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondracki N.L., Wellman N.S., Amundson D.R. Content analysis: review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2002;34:224–230. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fried T.R. Shared decision making—finding the sweet spot. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:104–106. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1510020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glatzer M., Panje C.M., Sirén C., Cihoric N., Putora P.M. Decision making criteria in oncology. Oncology. 2020;98:370–378. doi: 10.1159/000492272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glatzer M., Leskow P., Caparrotti F., Elicin O., Furrer M., Gambazzi F., et al. Stage III N2 non–small cell lung cancer treatment: decision-making among surgeons and radiation oncologists. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10:1960–1968. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-20-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drury N.E., Menzies J.C., Taylor C.J., Jones T.J., Lavis A.C. Understanding parents' decision-making on participation in clinical trials in children's heart surgery: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e044896. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pass H.I. PACIFIC: time for a surgical IIIA uprising. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156:1249–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eakin J.M., Mykhalovskiy E. Reframing the evaluation of qualitative health research: reflections on a review of appraisal guidelines in the health sciences. J Eval Clin Pract. 2003;9:187–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2003.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barbour R.S. Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? BMJ. 2001;322:1115–1117. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7294.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuper A., Lingard L., Levinson W. Critically appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337 doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

In this video, Terrance Peng, MPH, offers a brief overview of the objective, methodology, and significant findings of the study. Video available at: https://www.jtcvs.org/article/S2666-2736(22)00200-5/fulltext.