Abstract

Background

Thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion (TL‐IVDE) is the most common cause of acute paraparesis and paraplegia in dogs; however, guidelines on management of the condition are lacking.

Objectives

To summarize the current literature as it relates to diagnosis and management of acute TL‐IVDE in dogs, and to formulate clinically relevant evidence‐based recommendations.

Animals

None.

Methods

A panel of 8 experts was convened to assess and summarize evidence from the peer‐reviewed literature in order to develop consensus clinical recommendations. Level of evidence available to support each recommendation was assessed and reported.

Results

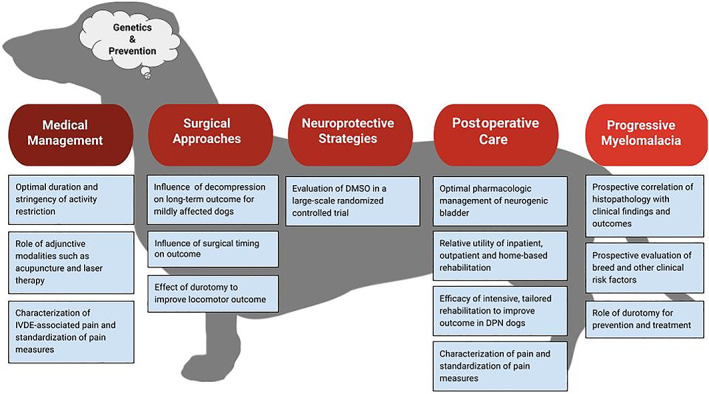

The majority of available literature described observational studies. Most recommendations made by the panel were supported by a low or moderate level of evidence, and several areas of high need for further study were identified. These include better understanding of the ideal timing for surgical decompression, expected surgical vs medical outcomes for more mildly affected dogs, impact of durotomy on locomotor outcome and development of progressive myelomalacia, and refining of postoperative care, and genetic and preventative care studies.

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Future efforts should build on current recommendations by conducting prospective studies and randomized controlled trials, where possible, to address identified gaps in knowledge and to develop cost effectiveness and number needed to treat studies supporting various aspects of diagnosis and treatment of TL‐IVDE.

Keywords: dog, intervertebral disc herniation, paralysis, spinal cord injury

Abbreviations

- 3D FSE

3‐dimensional fast spin‐echo

- ACVIM

American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- CT

computed tomography

- CTR

cutaneous trunci reflex

- CUSA

cavitronic ultrasonic surgical aspirator

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DPN

deep pain negative

- DPP

deep pain positive

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- EHLD

extensive hemilaminectomy and durotomy

- FGF4

fibroblast growth factor 4

- GI

gastrointestinal

- HASTE

half‐Fourier acquisition single‐shot turbo spin‐echo

- IVDE

intervertebral disc extrusion

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- MPSS

methylprednisolone sodium succinate

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MT

magnetization transfer

- NMES

neuromuscular electrical stimulation

- NP

nucleus pulposus

- NSAID

nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug

- PEMF

pulsed electromagnetic field

- PLDA

percutaneous laser disc ablation

- PMM

progressive myelomalacia

- PROM

passive range of motion

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- SCI

spinal cord injury

- STIR

short Tau inversion recovery

- T1W

T1‐weighted

- T2W

T2‐weighted

- TENS

transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation

- TL

thoracolumbar

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- UWTM

underwater treadmill

1. INTRODUCTION

In chondrodystrophic dog breeds, expression of an fibroblast growth factor 4 (FGF4) retrogene on chromosome 12 is associated with dramatically accelerated intervertebral disc degeneration. 1 In these dogs, early chondroid metaplasia, degeneration, and mineralization of the nucleus pulposus (NP) occur with ultimate failure of the intervertebral disc unit and extrusion of mineralized material into the vertebral canal. 2 , 3 This process, called Hansen type I intervertebral disc extrusion (IVDE), also occurs in non‐chondrodystrophic breeds at a much lower frequency, and unassociated with the FGF4 retrogene. As a consequence of contusion and compression of the spinal cord and nerve roots, thoracolumbar (TL‐) IVDE causes pain, paresis, or paralysis and retention incontinence. Affected dogs are managed medically or surgically and, although outcomes are usually successful, substantial nursing challenges remain. Thoracolumbar IVDE has been recognized since the 1880s and is the most common cause of acute paraparesis and paraplegia in dogs because of the popularity of chondrodystrophic dog breeds. 4 , 5 As a result, there is much literature available, the majority describing observational studies. Notably, guidelines on management of the condition are lacking. In this consensus statement on TL‐IVDE, we sought to review the available literature, weigh evidence, and generate recommendations for management and highlight areas in need of study. The paucity of high‐level evidence for many aspects of managing this condition limits the power of our recommendations, which should be viewed as guidelines and not as standards of care.

2. METHODS

A Qualtrics survey of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM)‐Neurology membership was distributed in October 2020 to gather priorities related to a consensus statement on diagnosis and management of acute TL‐IVDE in dogs. Eleven topics were identified, and subtopics were developed within them (Table 1). The consensus panel formed subgroups for systematic review of the literature in each area, and recommendations were formulated. A modified Delphi method was applied to the recommendations, where a combination of face‐to‐face videoconferencing and online anonymous voting was used to modify the statements toward consensus. Complete consensus was achieved for all statements.

TABLE 1.

Topics addressed by the ACVIM Neurology consensus panel on canine thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion

| Topic | Associated subtopics | No. papers included |

|---|---|---|

| Decision making in medical vs surgical management | Expected surgical vs medical outcomes based on severity, influence of level of pain on decision making, influence of recurrence on decision making | 114 |

| Components of medical management | Duration of exercise restriction, use of anti‐inflammatory medications, analgesia in medical management, adjunctive treatments such as rehabilitation and acupuncture | 26 |

| Diagnostic approaches | Imaging modality of choice, standard MRI sequences, prognostic information and CT/myelogram/MRI sequences, novel or specialized MRI applications | 103 |

| Surgical management | Evidence to support 1 approach over another, reported complications by approach, influence of timing on outcome, cut‐off time point beyond which recovery is unlikely | 88 |

| Fenestration | Fenestration of an affected disc intra‐op, fenestration of adjacent discs intra‐op, risk vs benefit, impact of approach and technique on success, percutaneous laser disc ablation | 38 |

| Neuroprotective strategies | Impact of published treatments on locomotor outcome, adverse effects | 46 |

| Postoperative pain management | Current knowledge about postoperative pain, efficacy for published treatments, adverse effects | 84 |

| Urination | Current knowledge about recovery of urination, features of optimal management, expected outcomes, prevention and treatment of UTI | 33 |

| Rehabilitation therapy | Inclusion as standard therapy, timing of initiation and duration, exercises and modalities to include, cage rest and the balance with rehabilitation, use of mobility aids | 21 |

| Progressive myelomalacia | Clinical and histopathologic features, predisposing and protective factors, ante mortem diagnostic approaches | 33 |

Note: Based on ACVIM membership responses to an initial Qualtrics survey, the consensus panel identified 10 topic areas and framed associated subtopics and questions around those to guide a systematic review of the veterinary literature.

Abbreviations: CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; No, number; UTI, urinary tract infection.

PubMed, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and CAB Direct were used along with the following search terms to identify relevant articles: Dog OR canine, intervertebral disc OR intervertebral disk, extrusion OR herniation OR disease OR Hansen type 1, TL. The group also added additional subtopic‐relevant terminology. Only peer‐reviewed studies containing original data were reviewed by the group. Although not included in the literature review, review articles were used to identify additional relevant papers not captured in the original searches. Papers were excluded if they were published only in abstract form, were not available in English, did not address TL‐IVDE, or did not report initial severity of signs or outcome in an understandable way. Level of evidence provided by individual studies was defined by a standard approach (https://www.elsevier.com/__data/promis_misc/Levels_of_Evidence.pdf). For each recommendation developed, the overall body of evidence supporting it was categorized as low, medium, or high level according to panel vote (Table 2). Recommendations are displayed in gray boxes throughout the manuscript, along with their level of evidence.

TABLE 2.

Definitions of levels of evidence used by the consensus panel

| Level of evidence | Definition applied |

|---|---|

| High | Multiple randomized controlled trials with concordant findings that find the same thing. The evidence strongly supports the conclusions. |

| Medium | Multiple retrospective studies with concordant findings, controlled trials, or single, small placebo‐controlled trials that provide good evidence for a specific defined population, but not the wider population. The evidence suggests findings are likely to be real. |

| Low | Isolated or small retrospective studies, single non‐controlled trials. The evidence suggests findings might be real. |

Note: These definitions were used to qualify the body of literature available to support individual recommendations. Once the literature was synthesized to develop a summary document for each topic, and the subtopics that fell within it, the group was asked to vote on the strength of the evidence available to support each developed recommendation.

3. DIAGNOSTIC APPROACHES

Diagnosis of TL‐IVDE in dogs is made using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), CT‐myelography, or myelography. These imaging modalities also facilitate surgical planning and prognostication. Each modality differs with respect to diagnostic accuracy, cost, availability, and adverse effects.

3.1. Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging has a diagnostic sensitivity >98.5%, 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 with enhanced diagnostic performance over CT in dogs with peracute signs, and when differentiating disc extrusion from protrusion. 8 , 10 , 11 , 12 Residual compression after surgery also can be detected. 13 , 14

An additional benefit of MRI is prognostication. Presence and extent of intramedullary T2 hyperintensity, T2 hypointensity, and attenuation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) signal on HASTE/T2* sequences have been variably associated with worse locomotor outcome 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 and development of progressive myelomalacia (PMM). 23 , 24 , 25 However, magnet strength, image plane, and observer might influence reliability of T2 hyperintensity as a prognostic indicator. 8 , 18 Bladder and urinary outcomes are not associated with cross‐sectional severity of spinal cord compression, length of spinal cord compression or focal vs extensive pattern of disc extrusion on MRI studies. 21 , 26 , 27 , 28

Limitations of MRI include prolonged acquisition time, 29 , 30 availability, and cost. 31 Standard protocols always include T2‐weighted (T2W) images and can be abbreviated to focus on sagittal sequences, 32 , 33 , 34 but diagnostic accuracy suffers without transverse images. 32 The HASTE/T2* or short Tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences might complement T2W images, 34 , 35 whereas inclusion of post‐contrast imaging does not improve diagnostic accuracy or treatment planning in most cases. 36 , 37 It remains to be determined if half‐Fourier acquisition single‐shot turbo spin‐echo (HASTE) is complementary or additive to T2W images or only worthwhile if the T2W images do not show evidence of hyperintensity. Novel 3‐dimensional fast spin‐echo (3D FSE) MRI protocols might offer decreased scan time while preserving accuracy. 38 Although there is emerging evidence in dogs with acute TL‐IVDE that specialized MRI applications, including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and magnetization transfer (MT), can provide information about injury severity and prognosis, they prolong scan time and require additional expertise, software and post‐acquisition processing.

A minimum of T2W sagittal and transverse images should be acquired. HASTE and short Tau inversion recovery (STIR), T1‐weighted (T1W) and T1W post‐contrast sequences might be considered but do not serve as replacements for standard T2W imaging sequences. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

3.2. Computed tomography

Computed tomography provides the benefit of rapid acquisition, lower cost and a diagnostic sensitivity of 81% to 100% in specific subgroups, namely chondrodystrophic dogs with mineralized discs. 9 , 12 , 29 , 31 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 It also can distinguish acute from chronically extruded mineralized disc material, 41 , 44 where evidence for this feature with MRI is limited. 37 It is less accurate in older (>5 years) and smaller dogs (<7 kg). 8 , 10 , 11 , 12 Computed tomography does not provide insight into the severity of parenchymal injury, and prognostic utility is therefore limited, but multilevel IVDE seen on CT had a worse prognosis than focal IVDE in 1 study. 45 Although MRI might predict a greater craniocaudal extent of extradural material compared to CT, both modalities provide similar ability to identify the length of compressive material. 6 , 8 , 9 , 27 , 45

3.3. Myelography/CT‐myelography

Diagnostic sensitivity of myelography or CT‐myelography is 53% to 97%, and myelography is less accurate than other modalities for determining correct lateralization of extrusion for surgical planning. 6 , 7 , 29 , 40 , 42 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 Myelography also carries a risk of seizures, especially in large dogs or those receiving larger intrathecal contrast volumes. 53 , 54 , 55 Extensive 56 , 57 spinal cord swelling and infiltration of contrast medium within the spinal cord 58 are poor prognostic factors on myelographic studies.

Magnetic resonance imaging, CT, CT‐myelography or myelography are reasonable modalities for diagnosing TL‐IVDE. When extruded material is mineralized, especially in young to middle‐aged adult, chondrodystrophic dogs, CT is sensitive in diagnosis and treatment planning. It therefore can be recommended as a first‐line advanced imaging modality when acute TL‐IVDE is suspected, with a low likelihood of missing a compressive surgical lesion and the added benefit of shorter scan time and lower cost (compared to MRI). Magnetic resonance imaging provides definition of intramedullary lesions which can inform surgical approach and prognostication for dogs with severe injuries and has superior ability to make diagnoses other than IVDE. When considering cases outside this typical clinical presentation, there is evidence to support the highest diagnostic sensitivity for high field MRI and higher risk of adverse events with myelography or CT‐myelography.

There is insufficient evidence to make recommendations regarding the role of imaging in dictating the type of decompressive surgery that should be performed (i.e., hemilaminectomy vs other) and if 1 imaging modality should be pursued over another for dogs with an inappropriate recovery shortly after decompressive surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging might be useful in guiding some treatment decisions (e.g., how long should the decompression be extended, whether to perform durotomy in deep pain‐negative (DPN) dogs). Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

Magnetic resonance imaging (over CT or myelography) can provide prognostic information in paraplegic dogs, especially paraplegic DPN dogs. Standard sequences, notably T2 sagittal and transverse, might be sufficient but inclusion of the HASTE can also provide prognostic information. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

4. MEDICAL VS SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Treatment of TL‐IVDE can be medical (conservative) or surgical. Medical management involves restricted activity and analgesia, whereas surgical management most commonly involves spinal cord decompression by hemilaminectomy, with or without disc fenestration. Decision‐making regarding selecting medical or surgical management depends on many factors. Conclusions related to this topic were drawn from a systematic review of cases published after 1983, 59 with data published before 1983 also considered, particularly in the context of medical management.

4.1. Outcomes for medically vs surgically managed dogs

Expected outcomes for dogs with TL‐IVDE managed medically or surgically are summarized in Table 3. Recurrence rates for medical management range from 15% to 66% compared with much lower rates for dogs managed by both hemilaminectomy and fenestration (covered in more detail under fenestration). 60 , 61 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66 , 72 There is a group of dogs that present with severe spinal pain and lameness because of lateral extrusion of disc material into the intervertebral foramen for which little is currently published. 65 These dogs represent a unique group that might not respond to medical management.

TABLE 3.

Outcome of dogs managed medically or surgically, based on severity of presenting signs

| Injury severity | Medical outcome | Surgical outcome | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal pain only and ambulatory PP | 80% (115 dogs) | 98.5% (336 dogs) | Lateral extrusion of disc material may lead to reduced response to medical management. | 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70 |

| Non‐ambulatory paraparesis | 81% (131 dogs) | 93% (341 dogs) | Level of recovery of non‐ambulatory dogs was less complete with conservative management. | 59, 60, 64, 69 |

| Paraplegia DPP | 60% (67 dogs) | 93% (548 dogs) | Recovery with medical management is prolonged and less complete compared to surgery | 59, 64 |

| Paraplegia DPN | 21% (48 dogs) | 61% (502 dogs) | None | 59, 64 |

Note: Literature prior to 1983 reports large numbers of dogs that were managed medically but frequently fails to separate paraplegia based on presence of deep pain perception. Rather, paraplegic dogs were grouped according to the presence or absence of “tonus”; these data were not included in this table. However, it is noted that 102 (65%) of 156 dogs that were paraplegic with tonus recovered with medical management, while 0 of 88 paraplegic without tonus dogs recovered. 60 , 67 , 69 , 71

Abbreviations: DPN, deep pain negative; DPP, deep pain positive; PP, paraparesis.

Ambulatory dogs can be managed successfully medically; however, consideration should be given to risk of recurrence. Surgical management might be considered in a young, active dog with multiple mineralized discs, particularly with recurrent events. Surgical decompression can be considered when neurologic signs are progressive, unimproved or pain is persistent despite appropriate medical management. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

Although non‐ambulatory paraparetic or paraplegic deep pain‐positive (DPP) dogs can be managed successfully medically, success rates, rate of recovery and chance of recurrence are more likely to be improved with surgery. Surgical management for these dogs is recommended. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

In paraplegic DPN dogs, success with medical management is largely poor with an increase in the frequency of PMM. Surgical management is recommended. Supported by moderate to high‐level evidence.

Short‐term hospitalization for 1‐2 days should be considered in dogs with progressive signs managed medically, to monitor for deterioration in neurological status. Supported by low‐level evidence.

When dogs cannot be treated surgically, a medical treatment attempt is reasonable for all grades of injury severity unless there is clinical evidence of PMM. Supported by low to moderate‐level evidence.

4.2. Components of medical management

Core components of medical management include activity restriction, pain management, treatment of retention incontinence, and prevention and treatment of skin damage and decubital ulcers as needed. Few studies evaluate these components critically, making it impossible to generate evidence‐based recommendations. Although treatment failures often are blamed on inadequate restriction, no published literature directly addresses this issue, and published recommendations for confinement range from absolute cage rest to “room rest” or “restricted activity” without details. Frequency and timing of re‐evaluation are important considerations, but the literature here also is lacking. Pain management strategies have been studied more rigorously in the postoperative setting, the results of which might also be relevant for medical management.

4.3. Duration of exercise restriction

Because of a lack of critical literature, many clinicians advise a period of decreased activity based on anecdote or institutional convention. Among studies that clearly state the duration of rest, several report a minimum but not total or average duration. 61 , 73 , 74 Others state a defined period of restriction, such as 4 weeks, but report variable degrees such as “absolute cage rest” and “room rest.” 64 In a retrospective case series in 223 dogs, duration of restricted activity ranging from none to >4 weeks was not associated with outcome. 63

A least 4 weeks of restricted activity is recommended, putatively to promote healing of the annulus fibrosus. This period should include confinement to a restricted area (crate ideally, or a small room without furniture) except for when performing rehabilitation exercises or outdoor toileting. There should be no off‐leash walking, no jumping on or off furniture and no access to stairs during this time. Supported by low‐level evidence.

4.4. Use of anti‐inflammatory medications

Several retrospective studies include a subgroup of dogs treated with anti‐inflammatory doses of corticosteroids but do not report the effect of this treatment on outcome. 61 , 64 , 67 , 73 , 74 , 75 , 76 , 77 However, there is limited evidence that corticosteroid use is associated with poorer outcome and decreased quality of life 63 as well as a higher rate of recurrence compared to nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in ambulatory dogs managed medically. 62 Despite insufficient evidence to support corticosteroid use for neuroprotective purposes in dogs with TL‐IVDE, anti‐inflammatory doses of corticosteroids may be of benefit in some cases with ongoing spinal pain potentially related to epidural inflammation. 66

Corticosteroids are not recommended for routine use in medical management of the acute phase of presumptive TL‐IVDE. In the chronic phase, a short course of anti‐inflammatory doses of corticosteroids may be of benefit for some dogs. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

No studies specifically evaluate the influence of NSAIDs on outcome of medical management of TL‐IVDE, but several studies include dogs treated with NSAIDs as part of their management plan. 60 , 62 , 63 , 64 , 77 In a retrospective study, dogs receiving NSAIDs had higher quality of life scores than those receiving corticosteroids. 63 Additional detail on potential adverse effects associated with both corticosteroids and NSAIDs is available in the context of postoperative pain management.

The use of NSAIDs for at least 5‐7 days is recommended in dogs managed medically for TL‐IVDE, provided there is no specific contraindication. Requirement for analgesia beyond this time period, despite appropriate activity restriction, should be considered as a possible indication for further investigation and potentially surgical management. The use of concurrent corticosteroids or multiple NSAID formulations in combination should be avoided. Supported by low to moderate‐level evidence.

4.5. Recommendations regarding analgesia

Most published information focuses on pain management in the postoperative setting.

Appropriate options for management of pain in dogs with TL‐IVDE managed medically include an NSAID, gabapentin or pregabalin for neuropathic pain and potentially muscle relaxants such as diazepam or methocarbamol. For dogs with pain severe enough to merit treatment with opioids, hospitalization should be recommended until that pain is controlled adequately. Supported by low‐level evidence.

4.6. Adjunctive treatments such as rehabilitation and acupuncture

Several studies investigate acupuncture for treatment of TL‐IVDE, with substantially variability in methodology, as well as lack of details on outcome measures and control group management protocol. These studies suggest that electroacupuncture could be associated with improved outcomes compared to medical management alone. 73 , 74 , 76 , 77 One study on electroacupuncture reported vomiting or diarrhea in 5 (16%) of 43 dogs, although dogs also received anti‐inflammatory doses of prednisolone for 7 to 12 days 73 ; most other studies do not report adverse event monitoring. 74 , 76 , 77

A study including 82 dogs of variable injury severity identified a tendency toward improved outcome in conservatively treated dogs undergoing physical rehabilitation. 75 Most recent research into rehabilitation in dogs with TL‐IVDE pertains to postoperative management. 78 , 79 , 80 Although frequency of adverse events associated with physical rehabilitation is low, 80 injury prevention is mandatory when considering a rehabilitation program.

Although there is a low level evidence to support the use of acupuncture as a component of medical management of TL‐IVDE, this treatment option currently is not recommended as an alternative to surgical management. Despite limited evidence to support the use of physical rehabilitation in medically treated dogs, basic rehabilitation exercises are recommended as an additional treatment (e.g., passive range of motion exercises and massage), with an emphasis on restricted activity for at least 4 weeks, followed by increased levels of physical activity. Supported by low‐level evidence.

5. SURGERY

Several surgical approaches for dogs with TL‐IVDE have been published. These include hemilaminectomy, mini‐hemilaminectomy/pediculectomy, dorsal laminectomy, partial corpectomy, fenestration of the intervertebral disc with or without concurrent laminectomy for removal of extruded disc material, and laminectomy with concurrent durotomy. Few studies provide direct comparisons of 1 surgical technique to another. 13 , 81 , 82 , 83 , 84 Descriptions of the various techniques and their associated benefits and complications have been summarized previously. 85

In addition, several authors recently have reported minimally invasive techniques to address intervertebral disc herniation in dogs. To date, most published veterinary studies are cadaver studies describing specific approaches, and only a few report outcomes in the clinical setting without employing a control group 86 , 87 , 88 , 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 ; however, there is a growing body of literature supporting their potential utility, which might gain future popularity.

The rationale for the addition of durotomy at the time of surgical decompression is a topic of re‐emerging interest and stems initially from experimental literature suggesting that durotomy could improve spinal cord blood flow, that the procedure was safe and that functional recovery in dogs with spinal cord injury (SCI) might be better with the addition of durotomy as compared to laminectomy alone. 93 , 94 , 95 Several veterinary clinical studies have evaluated the impact of durotomy on spinal cord perfusion or on outcome for dogs with TL‐IVDE that underwent laminectomy with durotomy, with mixed results. 96 , 97 , 98 , 99 One recent study retrospectively reported the outcomes of 51 paraplegic DPN dogs treated by hemilaminectomy with durotomy compared to 65 dogs treated by hemilaminectomy alone. 98 In that study, dogs that underwent durotomy were 3.32 times more likely to regain ambulation compared those treated by hemilaminectomy alone. No cases of PMM were observed in the durotomy group, but 21.5% of dogs treated with hemilaminectomy alone died of presumed PMM. An additional recent study prospectively described a cohort of 26 consecutive paraplegic dogs presented with loss of deep pain sensation treated by laminectomy and durotomy, for which 22 had postoperative follow‐up. Sixteen (72%) of 22 dogs recovered independent ambulation and only 1 (5%) dog developed PMM. 99 These more recent veterinary studies, along with the ongoing DISCUS trial (https://discus.octru.ox.ac.uk) in humans highlight renewed interest in the role of durotomy to improve outcome after SCI.

Each disc extrusion is different and therefore requires unique consideration for the best approach. Hemilaminectomy and mini‐hemilaminectomy (with or without concurrent fenestration) typically are considered the surgical approaches of choice because of increased ability to access and remove compressive disc material. Durotomy for dogs with severe neurologic signs may improve outcome and lessen risk of PMM, although further evaluation in a large cohort of dogs is needed. Lateral corpectomy has utility for more chronic or very ventrally located disc extrusions. Fenestration alone, without decompression, is not recommended for dogs with severe (non‐ambulatory paraparesis or worse) IVDE. Minimally invasive approaches appear safe and feasible but require further evaluation before they can be routinely adopted. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

5.1. Timing of surgical decompression

Whether urgent surgical decompression improves neurologic recovery in dogs with TL‐IVDE has been controversial for decades. There are several challenges with the currently available literature addressing this question. First, a positive outcome usually is defined dichotomously and simply as the ability to ambulate without support (or not), rather than assessing residual neurologic deficits using finer locomotor scoring systems. Second, dogs with the most severe disc‐associated SCI (paraplegic DPN) represent a small number in any given study and frequently are grouped with less severe injuries. Third, the extent of time delay before presentation often is not well reported by owners, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions on timing of onset of signs, particularly loss of deep pain perception. Interpretation of the current literature is complicated further by the fact that outcome also might be influenced by the rate of onset and features of the injury itself, independent of timing of decompression. Finally, study design and definition of successful outcome differ across studies, making it difficult to make comparisons.

Several retrospective and prospective case series have reported neurologic outcome and its association with surgical timing. 15 , 100 , 101 , 102 , 103 , 104 , 105 , 106 , 107 , 108 , 109 , 110 Taken individually, each study represents relatively low‐level evidence to inform clinical practice, and overall, the literature provides mixed evidence with respect to the influence of timing of surgical decompression on outcome in dogs with less severe injury, where most larger and more recent studies suggest a lack of association (Table 4). The suggestion that surgical decompression must be performed within 24 hours for paraplegic DPN dogs (a time‐point sometimes treated as a “cut‐off” by clinicians), in order to achieve a possibility of return of ambulation has been addressed by several studies. Although 1 study reported that no dogs in a very small group that had been DPN for >24 hours recovered ambulation, 105 a number of dogs reported elsewhere to have been paraplegic DPN for as much as a week or more before surgery went on to recover ambulation. 15 , 104 , 108 Publications addressing this topic generally are limited by their retrospective or prospective observational nature, because a prospective randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating timing of surgical decompression, particularly in paraplegic DPN dogs, might be viewed as unethical.

TABLE 4.

Studies presenting data regarding the influence of surgical timing on outcome in dogs with thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion

| Studies suggesting no influence | Studies suggesting possible influence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ref | N | Study design/outcome | Ref | N | Study design/outcome |

| 111 | 98 |

|

112 | 22 |

|

| 101 | 71 |

|

113 | 99 |

|

| 102 | 70 |

|

114 | 187 |

|

| 103 | 112 |

|

57 | 46 |

|

| 104 | 30 |

|

32 |

|

|

| 15 | 77 |

|

46 |

|

|

| 116 | 36 |

|

28 |

|

|

| 108 | 78 |

|

107 | 197 |

|

| 107 | 197 |

|

109 | 273 |

|

| 117 | 131 |

|

110 | 1501 |

|

Note: The literature provides mixed evidence with respect to the influence of timing of surgical decompression on outcome in dogs with less severe injuries, where the predominance of larger and more recent studies suggest a lack of association.

Abbreviations: DPN, deep pain negative; DPP, deep pain positive; N, number; PMM, progressive myelomalacia.

The pathogenesis of IVDE‐induced SCI supports that surgical decompression ought to be performed as early as possible for dogs with substantial neurologic deficits. However, taken as a whole, the current literature does not generally support the use of a specific timeline for urgent surgical decompression, even for DPN dogs that are paraplegic at the time of presentation. Some evidence suggests that delayed decompression may result in a longer time to achieve postoperative ambulation, which requires further investigation. The influence of surgical timing on locomotor outcome should be considered independently of its influence on development of PMM. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

Surgical treatment should not be declined simply because the dog has been paralyzed for an extended period, because the literature documents that recovery of ambulation may occur for dogs that present with DPN status and have been paralyzed > 1 week before surgery. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

6. FENESTRATION

Prophylactic fenestration refers to removing disc material in situ with the goal of preventing future extrusion. When first described as a surgical technique, fenestration was used as a means of treating disc extrusion without concurrent laminectomy; however, fenestration is now most commonly performed at the site of extrusion, along with decompression, to lessen further extrusion through the ruptured annulus in the early postoperative period. Fenestration also may be performed at adjacent disc spaces, typically between T11 and L4, as a prophylactic measure. Fenestration is an advanced procedure that requires excellent skill and knowledge of local anatomy to perform effectively and safely. Several surgical approaches and techniques have been described but direct comparisons are challenging because methods for reporting recurrence vary among studies and recurrences are not always confirmed by imaging or surgery. Finally, surgeon experience is likely to influence outcome, and RCTs in this area are difficult to design. The evidence for fenestration can be considered in the context of minimizing further extrusion of an already extruded disc, and in preventing future extrusion of non‐ruptured discs.

6.1. Fenestration of an already extruded disc at the time of decompressive surgery

Early recurrence has been reported within the first month after decompression and is almost exclusively caused by extrusion of additional disc material at the site of previous decompression. 71 , 118 , 119 , 120 Although some studies report few early recurrences without fenestration, 100 , 121 most published studies support that fenestration of the extruded disc at the time of decompression prevents early recurrence. 72 , 118 , 119 , 122 , 123 , 124 , 125 The overall low rate of recurrence at the site of decompression regardless of fenestration status may be related to much of the disc having extruded and been removed by decompression, differences in length and quality of follow‐up, how the definition of recurrence is applied and confirmed, and what endpoints are used.

Fenestration of the herniated disc space at the time of surgical decompression is recommended to minimize risk of recurrence at the site of herniation. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

6.2. Prophylactic fenestration of adjacent or distant, non‐extruded discs

A separate consideration is the impact of fenestration on future extrusion at new disc spaces, which is reported in up to 19% of all dogs undergoing decompressive surgery. 72 , 100 , 118 , 121 , 123 , 124 , 125 Most (87.5%) of these late recurrences develop within 1 to 2 disc spaces of the original extruded disc, 121 , 124 with rates of recurrence being higher for dachshunds (25% 121 ) and French bulldogs (44% 126 ). Although more extensive prophylactic fenestration remains controversial, several studies have identified a protective effect. 72 , 123 , 124 , 127 For instance, recurrence rates have been reported to be 17.89% with single site fenestration and 7.45% with multiple site fenestration, 124 where dogs with single site fenestration were 2.7 times as likely to develop confirmed recurrence than those with multiple fenestration. 124 The odds of recurrence at a non‐fenestrated disc space were 5.86 times that of a fenestrated site, 123 and the recurrence rate at a non‐fenestrated site was 11 times that of a fenestrated site. 124 Similarly, other authors reported that the prevalence of recurrence at non fenestrated discs was 26.2 times that of fenestrated discs. 127 Additional considerations for prophylactic fenestration include breed, where dachshunds 121 , 123 and French bulldogs 126 are more prone to recurrences than other breeds. The presence and number of mineralized discs at the time of decompression also are positively associated with rate of recurrence. 121 , 124 , 128

How many, and which, additional discs to fenestrate is difficult to address based on the currently available literature. Several studies support fenestrating adjacent mineralized discs accessible through the same incision because most recurrences develop within 1 to 2 disc spaces of the original extrusion. 121 , 124 This consideration may be particularly relevant for at‐risk breeds. Mineralized discs cannot be specifically identified on MRI, but discs that appear degenerate on MRI have increased risk of recurrence if not fenestrated. 128

Fenestration of adjacent, degenerated but non‐ruptured disc spaces, should be considered. In breeds predisposed to IVDE such as dachshunds and French bulldogs, fenestration is recommended even if the discs are not mineralized. The decision to fenestrate must take into account the status of the dog, surgical time, and other relevant factors. In situations where decompression is not performed, prophylactic fenestration could be considered. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

6.3. Adverse events, approach, and technique

Potential arguments against fenestration include the possibility of additional surgical trauma, increased anesthetic time, and associated costs. Risks or complications associated with fenestration that have been reported in the veterinary literature include extrusion of additional disc into the vertebral canal at the site of extrusion, 127 , 129 the potential to induce vertebral instability, 130 , 131 increased morbidity when performed at L5‐6 & L6‐7, 124 , 132 pneumothorax 68 , 123 , 133 , 134 or hemothorax (chemonucleolysis 123 ), neuromuscular complications secondary to trauma to the peripheral nerve or nerve root, 124 , 134 hemorrhage from the sinus or vertebral artery, 68 , 124 and development of spondylosis deformans. 135 Additionally, and specific to laser disc ablation, abscess and discospondylitis have been reported. 134 The overall reported complication rate associated with various fenestration techniques is quite low, and a recent survey of the literature reported a published complication rate of 0.01%, or only 15 instances in over 1100 published cases. 85 Cost benefit analysis of the additional anesthetic and surgical time required for fenestration and the clinical relevance of any additional tissue trauma is not addressed by the currently available literature.

Multi‐site fenestration is associated with an overall very low complication rate, rarely leading to clinically relevant morbidity when performed by experienced surgeons. Reported complications associated with fenestration cranial to the L4‐5 disc are limited and are not a threat to life or mobility. Caudal to L3‐4, fenestration carries increased risk; therefore, routine fenestration of L4‐5 and more caudal sites is not recommended. Fenestration at T10‐11 and above usually is not recommended due to the low rate of disc extrusion at these sites. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

Some evidence supports that surgical approach influences retrieval of disc material, with a ventral or lateral approach providing better success than a dorsolateral approach. 135 , 136 , 137 However, most of these studies involved fenestration alone. Thus, the practicality of a dorsolateral approach for fenestration must be considered when a decompressive laminectomy also is being performed.

Technique has been shown to influence yield of disc material during fenestration, where power‐assisted fenestration resulted in more complete removal of the NP compared to manual fenestration. 119 , 122 However, these studies involved a single surgeon and therefore the results potentially are user dependent. Cavitronic ultrasonic surgical aspirator (CUSA) and vacuum aspiration also are described as options in the literature. 132 , 138 Importantly, the literature suggests that complete removal of the NP is not achieved by any technique or approach, but that the effectiveness of fenestration is governed by the amount of NP removed at surgery. 139 Additionally, an inflammatory reaction that might be hypothesized to dissolve the remaining nucleus does not occur. 139 The void created by fenestration and the annulus defect heals relatively quickly (4‐16 weeks) by invasion of fibrocartilage after fenestration. 140 Although some fenestration techniques may result in more removed NP, the clinical relevance of such differences with respect to recurrence has yet to be evaluated.

Insufficient evidence exists to support a single surgical approach to fenestration over another, and surgical approach tends to be dictated by the decompressive procedure and surgeon experience. Creating a fenestration without subsequently curetting NP from the disc space does not lead to removal of disc material by an inflammatory response. Although power fenestration has been shown to improve yield over manual (blade) fenestration, complete fenestration is not achieved by any technique, and the relationship between increased NP removal and recurrence after fenestration has not been explored. Supported by low‐level evidence.

With respect to percutaneous laser disc ablation (PLDA) as a unique approach, the group made the following recommendation: 134 , 141 , 142

Percutaneous laser disc ablation (PLDA) appears to be safe and, based on a low‐level of evidence in a large number of dogs, may limit recurrent disc extrusion. Supported by low to moderate‐level evidence.

7. NEUROPROTECTIVE STRATEGIES

Evaluation of cell‐based treatments was considered beyond the scope of this discussion. Many neuroprotective strategies have been proposed to mitigate secondary injury or promote recovery of neuronal function or functional connectivity. A subset of these strategies evaluated in the veterinary clinical setting have evidence suggesting a lack of effectiveness to improve locomotor outcome (Table 5); their routine use therefore is not currently advocated.

TABLE 5.

Neuroprotective strategies not currently recommended for routine treatment of TL‐IVDE

| Intervention | References | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy | 143, 144 |

|

| Electroacupuncture (EA) | 73, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151 |

|

| Photobiomodulation/Laser | 78, 116, 152, 153, 154 | |

| Polyethylene glycol (PEG); intravenous | 155, 156 |

|

| GM6001 (MMP inhibitor) | 157, 158 |

|

| Dexamethasone | 159, 160, 161 |

|

| Methylprednisolone sodium succinate (MPSS) | 155, 159, 162, 163, 164 |

|

| Other steroid (eg, prednisone) | 82, 107, 108, 159, 165 |

Note: Existing veterinary clinical evidence suggests these are not effective at improving locomotor outcome. Some may have evidence supporting their utility in other aspects of thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion (noted where applicable).

Abbreviations: NSAID, nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory; PMM, progressive myelomalacia; SCI, spinal cord injury.

Despite conflicting findings, in a double‐blind RCT in paraplegic DPN dogs undergoing concurrent surgical decompression, dogs treated with the matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) inhibitor GM6001 with a dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) carrier or DMSO alone showed significantly improved locomotor outcome compared to those treated with a saline control. Although these findings suggest that DMSO might be the primary influence on improved outcome, group sizes were small and no dogs in the saline‐treated group recovered locomotor function. 157 , 166

When used in combination with decompressive surgery for dogs that are paraplegic DPN at the time of presentation, DMSO might improve locomotor outcome. Routine administration of DMSO, although currently not recommended as standard adjunctive neuroprotective treatment for acute TL‐IVDE, deserves further evaluation in a larger cohort. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

8. PAIN MANAGEMENT

It is accepted that both TL‐IVDE and its surgical treatment cause pain. Nociceptive pain (perception of a noxious stimulus processed by a normally functioning somatosensory system) is caused by both the disc extrusion and decompressive surgery and is the primary target of many treatment strategies. Neuropathic pain, caused by a lesion that leads to damage or dysfunction of the somatosensory system, 167 also is known to be a common phenomenon in people after SCI; however, limited data are available on its occurrence in dogs. Pain after TL‐IVDE has been quantified in dogs using ordinal pain scores, frequency of rescue medication use, and mechanical sensory thresholds (MST). 143 , 144 , 145 , 146 , 168 , 169 , 170 , 171 , 172 , 173 , 174 , 175

8.1. Postoperative pain

The prevalence and time course for resolution of paraspinal pain in dogs after surgical decompression treated using a standard postoperative analgesic protocol (opioids, anti‐inflammatory drugs and gabapentin) have been quantified prospectively. 176 This analgesic protocol controlled immediate postoperative pain based on ordinal pain scales. However, MSTs were decreased for up to 6 weeks in the vicinity of the surgical wound. These values normalized by 6 months in 85% of dogs, but 15% had persistent hyperesthesia suggesting chronic neuropathic pain. 176

Dogs can experience surgical site discomfort for up to 6 weeks after hemilaminectomy and a small percentage might develop chronic neuropathic pain. The need for prolonged treatment of pain is unclear, but veterinarians should evaluate dogs for pain at the time of first re‐evaluation and advise owners to observe for signs of pain (e.g., vocalizing, reluctance to do certain activities, flinching when touched) for up to 6 weeks. Supported by low‐level evidence.

8.2. Management of postoperative pain

No standardized protocol for postoperative pain management is available, but based on studies that report specific protocol details, combinations of opioids and anti‐inflammatory drugs are used frequently. 28 , 91 , 97 , 102 , 119 , 144 , 176 , 177 , 178 The impact of adding various additional treatments to an existing analgesic protocol has been examined in RCTs and case cohort retrospective studies (Table 6). No studies compare NSAIDs, corticosteroids or different opioids. Numerous other treatments commonly are used, many of which have no published data on efficacy in the context of TL‐IVDE. (Table 7).

TABLE 6.

Details of studies investigating different intra‐ and postoperative pain therapies

| Paper | Design | Treatment | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 171 | RCT, n = 26 | Epidural morphine | Better postoperative (48 h) pain control |

| 168 | RCT, n = 12 | ||

| 172 | RCT, n = 30 | Epidural morphine & dexmedetomidine & hydromorphone | |

| 174 | Retrospective case cohort study n = 114 | Erector spinae block | Better intra‐ and postoperative (48 h) pain control |

| 175 | RCT, n = 30 | Better intra‐ and postoperative (24 h) pain control | |

| 169 | Prospective, n = 10 | Fentanyl patch | Plasma levels therapeutic, pain control adequate (72 h) |

| 173 | RCT, n = 46 | Adjunctive Pregabalin 4 mg/kg q8h | Better pain control for 5‐d postop |

| 170 | RCT, n = 63 | Adjunctive Gabapentin 10 mg/kg q12h | No benefit over placebo for 5‐d postop |

| 145 | RCT, n = 15 | Postoperative electroacupuncture | No benefit for 3‐d postop |

| 146 | RCT, n = 24 | Preoperative acupuncture | Reduced intraoperative need for fentanyl, reduced pain on recovery from anesthesia |

| 144 | RCT, n = 16 | Pulsed electromagnetic fields | Reduced postoperative pain from 2 to 6 wk |

| 143 | RCT, n = 53 | Pulsed electromagnetic fields | Reduced postoperative pain for 6 wk |

| 178 | RCT, n = 20 | Harmonic blade for surgical approach | Reduced postoperative pain for 30 d |

| 91, 92 |

a: Controlled trial (normal dogs) n = 6, b: case report, n = 1 |

Minimally invasive surgery |

Reduced need for opioids postoperatively Reduced postoperative pain for 7 d |

Note: Various analgesic protocols have been examined in RCT and case cohort retrospective studies.

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

TABLE 7.

Therapies for postoperative pain reported but not investigated for efficacy

Given the breadth of analgesic options published for use in dogs, coupled with variability in study designs and outcome assessments, it is difficult to compare findings across studies. However, the following postoperative analgesic protocol is proposed: IV or SC opioids for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively (longer if needed), fentanyl patch for 3 to 5 days postoperatively, NSAIDs for 7 days postoperatively in addition to or instead of a fentanyl patch. A medication for neuropathic pain such as pregabalin at a dosing interval of q8h might be added to the suggested protocol to improve pain control. A similar positive effect could not be shown for gabapentin administered q12h. Gabapentin might be beneficial at a dosing interval of q8h, although evidence to support that assumption currently is lacking. In addition, pre‐ and intraoperative interventions such as erector spinae block, epidural morphine as well as postoperative pulsed electromagnetic field therapy (PEMF) have been proven to decrease intra‐ and postoperative pain and their use can be considered. Supported by low‐level evidence.

8.3. Adverse effects of pain medications

Medications used for pain control are known to have potential adverse effects. However, it is difficult to determine the relative contribution of pain medications to the development of complications in the setting of disc‐associated SCI, hospitalization, anesthesia, and surgery. 182

Many dogs with IVDE treated with corticosteroids alone or in combination with NSAIDs develop subclinical or clinical adverse gastrointestinal (GI) effects such as diarrhea, gastritis, GI ulceration, regurgitation and pancreatitis. 159 , 170 , 183 , 184 , 185 , 186 , 187 , 188 They occur at comparable rates in dogs treated with NSAIDs or corticosteroids alone, but at higher rates if these drug classes are combined. 182 However, fatal colonic perforations have been described in dogs treated with high doses of dexamethasone, 189 , 190 , 191 and dogs treated with dexamethasone are more likely to develop urinary tract infections (UTIs) and diarrhea than those treated with other or no glucocorticoids. 159 Although high doses of methylprednisolone sodium succinate (MPSS) cause GI bleeding on endoscopy, 162 1 RCT did not encounter a higher rate or severity of GI signs in dogs receiving high dose MPSS when compared with 2 other study arms, although dogs that already had received an NSAID or other corticosteroid were excluded from this trial. 155 Different Gl protectants have been used to decrease or prevent GI signs, but studies suggest that these are not effective. 182 , 185

Opioids can increase the risk of gastro‐esophageal reflux and regurgitation, 192 , 193 as can medications that cause sedation such as gabapentin and pregabalin. Vomiting and regurgitation are risk factors for aspiration pneumonia, which has been reported in up to 6.8% of dogs treated surgically for IVDE. 20 , 194

Gastrointestinal mucosal lesions are common in dogs with IVDE, but often are subclinical. It is not known if these lesions are caused by the disease itself, the medications used or a combination of both. Life‐threatening GI lesions have been reported in dogs treated with high doses of dexamethasone or with combinations of NSAIDs and glucocorticoids. If GI signs are present, NSAIDs or glucocorticoids should be discontinued. The use of opioids should be considered as a potential contributing factor to regurgitation. Supported by low‐level evidence.

9. MANAGEMENT OF URINATION

One of the most challenging consequences of TL‐IVDE is loss of voluntary urination and the resulting retention incontinence. This complication negatively impacts overall recovery and the quality of life of both dogs and owners. 195 , 196

9.1. Recovery of voluntary urination

Data that summarize the rate and success of recovery of voluntary urination are provided in Table 8. Ultrasonography and cystometrography indicate that recovery of normal bladder function lags behind the initial appearance of voiding and still can be suboptimal 6 weeks after motor recovery. 158 , 198

TABLE 8.

Studies describing timing and level of recovery of voluntary urination

| Paper | Design | Outcomes | Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing and quality of recovery of voiding | ||||||

| 198 | Prospective (n = 15) | Voiding efficiency via US |

|

|||

| 197 | Prospective (n = 26) | Onset of urination |

|

|||

| 158 | Prospective case (n = 20), cohort (n = 10) | Cystometry |

|

|||

| 199 | Retrospective (n = 48 T3‐L3, 48 L4‐S3) | Urination recovery |

|

|||

| 28 | Retrospective (n = 57) | Urination recovery |

|

|||

| 144 | PEMF RCT (n = 16) | DPN dogs, urination recovery |

|

|||

| Rate of long‐term urinary and fecal incontinence | ||||||

| 102 | Retrospective (n = 64) | Long‐term incontinence, DPN dogs |

37 dogs recovered deep pain perception: 32%—UI & FI; 41%—FI 18 dogs persistent DPN: 100%—UI & FI |

|||

| UI | FI | Both | ||||

| 125 | Retrospective (n = 709) | Presence of long‐term incontinence | Amb: 270 | 15/5.6% | 9/3.3% | 6/2.2% |

| Non‐amb PP: 171 | 9/5.3% | 5/2.9% | 3/1.8% | |||

| DPP: 158 | 26/16.5% | 14/9% | 10/6% | |||

| DPN: 110 | 42/38.2% | 20/18.2% | 16/14.5% | |||

Abbreviations: DP, deep pain; DPN, deep pain negative; DPP, deep pain positive; FI, fecal incontinence; n, number; PP, paraparetic; UI, urinary incontinence; US, ultrasound.

Paraplegic dogs cannot urinate voluntarily, whereas dogs with motor function and pain perception can. As voiding recovers, it is commonly incomplete for a period of weeks post‐injury, resulting in urine retention. This complication places dogs at higher risk than usual for development of UTI. Dogs with severe injury, even if they recover pain perception and motor function, might have suboptimal continence. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

9.2. Bladder evacuation

Techniques used for bladder evacuation include manual expression and intermittent and indwelling catheterization. Efficacy of manual expression varies widely with a mean of 50% bladder emptying. 200 Although the method of bladder evacuation used does not influence the frequency of UTI, prolonged placement of indwelling catheters might delay recovery of voluntary urination and increase the risk of UTI. 201 , 202 No information is available on the impact of technique on factors such as pain or distress or regarding complications such as urethral or bladder damage.

Bladder expression technique chosen should be tailored to the dog, the clinician and the technicians caring for the dog. Placement of an indwelling urinary catheter is an effective and low risk management method in the short term; however, duration of indwelling catheterization should be minimized whenever possible because of increased risk of UTI. As voluntary urination returns, the bladder should be palpated, or ultrasonography performed, to ensure adequate emptying has been achieved. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

9.3. Pharmacologic intervention

Use of drugs to relax urethral sphincters is common practice, but literature on efficacy is extremely limited. Details provided in clinical trials and retrospective studies were used to summarize standard protocols for dogs undergoing manual expression. 144 , 158 , 197 , 199 , 203 These protocols aim to relax the internal and external urethral sphincters using 1 or both of an alpha‐adrenergic antagonist (eg, prazosin, phenoxybenzamine, alfuzosin, tamsulosin) and a centrally acting muscle relaxant (eg, diazepam). Experimental studies characterize the effects of alpha‐adrenergic antagonists on urethral tone, but clinical relevance in dogs with alterations in urethral tone is difficult to establish. 204 Apart from a single retrospective study, 205 no data validate clinical efficacy. Although hypotension is a possible adverse effect of alpha‐adrenergic antagonists, no reports of clinically relevant hypotension in this population have been published. Based on the literature, bethanechol is not used to enhance detrusor activity routinely in dogs recovering from acute TL‐IVDE. Some panel members noted anecdotally that unwanted adverse cholinergic effects can occur at doses that induce detrusor contraction.

Although evidence is lacking to guide use of medications to relax the urethral sphincters in dogs with TL‐IVDE, use of an alpha‐adrenergic antagonist to relax the internal urethral sphincter with or without a centrally acting muscle relaxant such as diazepam to relax the external sphincter is recommended in dogs in which the bladder cannot be manually expressed easily. These drugs should be continued until voluntary urination has been re‐established. Long‐term use of these medications usually is not necessary in chronically paralyzed dogs. Supported by low‐level evidence.

9.4. Complications of retention incontinence

Urinary tract infections are the most common complication reported in the literature along with hematuria and bacteriuria. 197 No reports of bladder rupture in this population of dogs have been published, but because of the gravity of this complication, the panel felt it should be taken into consideration when managing retention incontinence. The literature on UTIs is challenging to summarize because of different exclusion criteria, definitions of UTI, and sample timing. Most studies define UTI as bacterial growth of >1000/mL, but distinguishing active infection from bacteriuria requires pyuria and documentation of clinical signs, which can be challenging if the dog is paralyzed. 206 Frequency of UTI ranges from 0% to 42% in the first postoperative week, 17% to 36% in the first 6 weeks and 15% at 3 months. 197 , 202 , 203 Escherichia coli is the most common isolate and frequently is associated with antibiotic resistance. 197 , 202 , 203 , 207

Risk factors for UTI include the severity of neurologic deficits, duration of retention incontinence and duration of indwelling catheterization. 197 , 202 , 203 Conflicting evidence exists on the effect of perioperative antibiotics on subsequent UTI frequency, 202 , 203 , 208 but good antibiotic stewardship guides veterinarians to avoid prophylactic use of antibiotics postoperatively. 209 Cranberry extract does not decrease the risk of UTI. 210

Antibiotics should not be used prophylactically to decrease the frequency of UTIs in dogs with TL‐IVDE and it is important to establish a specific diagnosis of UTI versus clinically insignificant bacteriuria. The risk of UTI can be minimized by limiting duration of indwelling catheterization, monitoring voiding efficiency, and using medications to relax urethral sphincters as needed. Supported by low‐level evidence.

10. PHYSICAL REHABILITATION

Physical rehabilitation is increasingly utilized as a component of the management plan for dogs diagnosed with TL‐IVDE, especially postoperatively.

Questions remain regarding the value of incorporating rehabilitation protocols, which populations benefit, as well as when to initiate protocols, how long to continue therapy and the optimal treatment regimens.

10.1. Efficacy of physical rehabilitation

In non‐ambulatory dogs with TL‐IVDE managed surgically, 2 RCTs provide evidence that in‐hospital, staged, intensive physical rehabilitation for 10‐14 days postoperatively is well‐tolerated but does not improve the recovery of ambulation compared to a control population receiving only basic rehabilitation in the form of passive range of motion (PROM) and assisted walking. 78 , 80 In dogs with incomplete injuries, rehabilitation also did not impact the rate of recovery of walking, walking coordination, proprioceptive placing or muscle mass. 80 One RCT excluded DPN dogs (80), and the other was not adequately powered to evaluate them; evidence is conflicting regarding the role for rehabilitation in these severely affected dogs. 78 , 79 , 152 , 211 , 212 , 213 , 214 , 215 , 216 Study populations and rehabilitation protocols vary widely, and control groups frequently are lacking. Intensive rehabilitation might enhance the recovery of ambulation in paraplegic DPN dogs. 212

Although not related to locomotor outcome, rehabilitation has been associated with weight loss and muscle mass gain in dachshunds during a 3‐month postoperative study period. 217 Therefore, rehabilitation could have positive implications for recovery of general mobility and overall well‐being, but such effects cannot be definitively attributed to the exercises performed.

In dogs with incomplete injuries, rehabilitation performed postoperatively is safe but fails to demonstrate benefit on the rate or extent of recovery of walking compared to dogs receiving only basic exercises (e.g., PROM, assisted walking). Although these findings suggest that more intensive, tailored rehabilitation protocols are not needed for all dogs with incomplete injuries to achieve a successful outcome (i.e., independent, coordinated ambulation), available evidence does support inclusion of basic exercises as standard components of routine postoperative care in all dogs regardless of severity. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

10.2. Rehabilitation protocols

Postoperative rehabilitation can be initiated safely as soon as 24 hours postoperatively without adverse consequences such as increased pain or neurologic deterioration, 78 , 80 , 216 but delayed initiation up to 2 weeks postoperatively still might benefit recovery. 79 When specified, hydrotherapy or underwater treadmill (UWTM) therapy is safely initiated anywhere from 3 (with incision protection) to 14 days postoperatively. 78 , 80 , 152 , 212 , 213 , 216 , 218 Among persistently paraplegic DPN dogs, earlier initiation of rehabilitation (at approximately 1 vs 3 weeks) might improve the likelihood of recovery of ambulation. 212

Reported duration of physical rehabilitation varies from initial hospitalization only to many months in some dogs. 75 , 78 , 79 , 80 , 152 , 212 , 217 , 218 Longer duration of rehabilitation (more days participating in rehabilitation, more sessions, more UWTM sessions) is associated with better improvement in neurologic status and shorter time to recovery of weight‐bearing stepping. 218

Rehabilitation protocols vary widely among studies, but exercises included as components of rehabilitation protocols for dogs recovering from TL‐IVDE are outlined in Table 9. Mechanistic or physiologic evidence to support inclusion of specific exercises generally is lacking, but a single cadaver‐based study proposed a neuroanatomic basis for performing specific mobilization stretching exercises targeting the TL spinal cord and nerve roots. 219 Reported frequency of exercises ranges from 1 to 3 times per day while hospitalized, 1 to 3 times per week for outpatient sessions, and 1 to 5 times per day for at‐home exercises, but frequency commonly is not specified.

TABLE 9.

Rehabilitation exercises with timeline of implementation described in the literature

| Rehabilitation Exercise | Timing of implementation and therapy duration | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cryotherapy (cold or warm packing) |

Initiation: 24 to 48 h postop Duration: 48 h (cold packing) ±1 to 4 wk (warm packing) |

75, 78, 79, 80, 143, 144 |

| Range of motion (passive and active stretching) and massage |

Initiation: 24 to 48 h postop Duration: 10 d to 6 wk or until ambulation or normal mobility |

75, 78, 79, 80, 116, 144, 152, 211, 212, 214, 216, 217, 218 |

| Sensory stimulation (eg, toe pinching, hair brushing, different flooring surfaces) |

Initiation: 48‐h to 3‐wk postop Duration: 10 d to 6 wk or until ambulation |

78, 116, 212, 215, 218 |

| Deep tendon reflex stimulation | Initiation and duration not specified | 213 |

| Assisted standing, weight shifting, sit‐to‐stand |

Initiation: 24 to 48 h postop, once able to bear some weight Duration: 5 d to 6 wk or until normal body weight support, ambulation or normal mobility |

75, 78, 79, 80, 116, 144, 212, 213, 215, 217, 218 |

| Assisted walking (over ground) |

Initiation: 24 to 48 h postop Duration: 4 to 6 wk or until ambulation |

75, 79, 80, 144, 212, 214, 215, 217, 218 |

| Land treadmill walking |

Initiation: 3 d to 3 wk postop Duration: 6 wk to 3 mo or normal mobility |

79, 214, 215 |

| Hydrotherapy (swimming or UWTM walking) |

Initiation: 2 (swimming) or 3 (UWTM) to 14 d postop, typically once able to bear weight or motor is present (for UWTM) Duration: 7 d to 3 mo or until ambulation or normal mobility |

78, 79, 80, 152, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 218 |

| Manual gait patterning (using land treadmill, UWTM or cart/lift‐assisted) |

Initiation: 3 d to 3 wk postop Duration: 6 wk to 3 mo or until ambulation or normal mobility |

79, 214, 215, 217, 218 |

| Balance exercises (eg, balance boards) |

Initiation: 3 d to 14 d, once able to stand Duration: 14 d to 3 mo or until ambulation or normal mobility |

79, 80, 152, 213, 214, 218 |

| Advanced gait & proprioception exercises (eg, cavaletti rails, variable terrain or inclines) |

Initiation: 7 to 14 d, not before ambulatory and added progressively Duration: 6 wk to 3 mo or until strong ambulation |

79, 152, 214, 215, 218 |

Abbreviation: UWTM, underwater treadmill.

Several additional modalities have been included under the umbrella of rehabilitation and are listed in Table 10. No specific evidence is available regarding the benefit of inclusion of neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) or infrared therapy, but the utility of photobiomodulation, PEMF and electroacupuncture is considered in the neuroprotective strategies section.

TABLE 10.

Rehabilitation treatment modalities with timeline of implementation described in the literature

| Rehabilitation treatment modality | Timing of implementation and duration of therapy | References |

|---|---|---|

| Photobiomodulation (ie, laser therapy) |

Initiation: <24 h to 5 d postop Duration: 5 d to 6 wk |

78, 79, 116, 152, 153 |

| Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (including inferential) |

Initiation: <24 h to 5 d postop Duration: up to 4 wk |

75, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216 |

| Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) |

Initiation: 1 to 7 d postop, prior to any motor function Duration: 5 to 10 d or until motor or ambulation present |

78, 80, 215, 218 |

| Functional electrical stimulation (FES) |

Initiated within 7 d postop. Duration: 2 wk |

215 |

| Infrared radiation treatment |

Initiated within 5 d post‐injury Duration: up to 4 wk |

75, 213 |

| Ultrasound therapy |

Initiated within 5 d post‐injury. Duration: up to 4 wk |

75 |

| Pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy |

Initiation: preop to 24 h postop Duration: 7 to 14 d (q2‐12hr treatment frequency) and 14 d to 4 wk (q12h treatment frequency) |

80, 143 |

| Acupuncture or electroacupuncture |

Initiation: preop to 3 d post‐presentation or surgery Duration: up to 72 h (pain control) or 1 wk to 6 mo (functional recovery) |

73, 74, 76, 77, 145, 146, 149, 150, 213, 220, 221, 222, 223 |

Although some studies did not use standardized exercise protocols, the RCTs described phased exercise combinations and indicated that pre‐defined recovery benchmarks can be used to establish standardized yet dynamic protocols that evolve over time as specific functions are regained. This approach includes information regarding which specific exercises and additional treatment modalities are indicated at what time points or functional status (eg, NMES is poorly tolerated once motor function returns) as part of an overall multimodal approach to recovery from TL‐IVDE. 75 , 78 , 80 , 217

Reasonable timing for postoperative rehabilitation in dogs consists of initiation within a 24‐hour to 14‐day window postoperatively and continuing for at least 2 to 6 weeks. However, it is possible that optimal timing might fall outside of this timeframe or might vary among patient subsets (e.g., based on severity of neurologic status). Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

The specific exercises and adjunctive modalities that should be included in an optimal postoperative rehabilitation regimen remain to be determined. At a minimum, a basic rehabilitation protocol can be recommended to include cryotherapy, PROM, massage, assisted standing and walking, which can be performed with no specialized equipment or training. Although more data are needed to evaluate precisely how such treatment protocols should be adapted over time, a stepwise approach with increasing intensity and incorporation of additional exercises can be tailored to the individual patient as neurologic status changes. Supported by low‐level evidence.

10.3. Activity restriction

Activity restriction, as described in the medical management section, also is important in postoperative care to allow healing of both the surgical site and the annulus fibrosus, and presumably to minimize the risk of early re‐extrusion at the surgical site. Although details are commonly poorly articulated, dogs strictly rested in a hospital setting for 2 weeks after surgery regained ambulation more quickly compared to historical controls recovering at home. 80 However, activity restriction also was recommended for dogs at home and several other factors could explain or have contributed to this increased rate of improvement.

Despite limited evidence, there is consensus agreement that confinement and activity restriction for a period of at least 4 weeks be recommended as a component of standard postoperative care for dogs with TL‐IVDE. Note that activity restriction does not mean avoidance of rehabilitation exercises. Supported by low‐level evidence.

11. PROGRESSIVE MYELOMALACIA

Progressive myelomalacia is a clinical syndrome characterized by progressive necrosis, ischemia and hemorrhage of the spinal cord that expands cranially and caudally from an initial site of insult. 224 Clinical signs reflect progressive tissue destruction, and include loss of pelvic limb reflexes, and pelvic limb, trunk, and abdominal muscle tone; cranial progression of the cutaneous trunci reflex (CTR) caudal border; and ultimately thoracic limb involvement and ventilatory failure. 24 , 225 , 226 , 227 Progressive myelomalacia usually develops within days (24 hours up to 14 days) of an acute IVDE‐associated injury to the TL spinal cord and is not always apparent at time of presentation. 227

The pathophysiology of PMM, although not completely understood, involves primary mechanical damage to and compression of the spinal cord, followed by secondary damage. 228 Increased pressure within the neuraxis might play a role in longitudinal propagation of damage 226 Studies focused on paraplegic DPN dogs report prevalence of PMM of 10% to 33% 102 , 229 ; however, development of PMM has been reported in a small number of dogs that presented with less severe injury and subsequently deteriorated. 23 , 227

11.1. Diagnosis of progressive myelomalacia

Although histopathologic examination presently is the gold standard for diagnosis of PMM, a presumptive antemortem diagnosis often is needed in the clinical setting. A combination of clinical findings and their evolution over time is reported in cases with histopathologic confirmation of PMM. 24 , 225 , 226 , 227 , 228 These include ascending paralysis, hypoventilation, loss of segmental spinal reflexes, cranial migration of the CTR caudal border, decreased abdominal tone, Horner syndrome, diffuse pain, thermodysregulation, and malaise. 24 , 225 , 226 , 227 , 228 Although the diagnostic accuracy of these clinical findings requires further study, additional literature describes clinical signs in DPN dogs with presumptive PMM (Table 11). Clinical suspicion can be further heightened by findings on MRI and by serum biomarker measurements (Table 12).

TABLE 11.

Clinical features suggestive of an ante mortem diagnosis of progressive myelomalacia in paraplegic DPN dogs with thoracolumbar intervertebral disc extrusion

| Clinical signs in DPN dogs | Reference | Predictive/diagnostic utility—for presumptive PMM |

|---|---|---|

| CTR cut‐off ≥1–2 spinal cord segments cranial to the site of IVDE | 155, 225 |

|

| 107 |

|

|

| Progressive CTR cut‐off advancement | 230 |

|

| Weak to absent patellar reflexes with a disc extrusion located cranial to the lumbar intumescence | 24 |

|

| 155 |

|

|

| 227 |

|

|

| Weak to absent anal tone and perineal reflex with a disc extrusion located cranial to the lumbar intumescence |

|

|

| Loss of abdominal tone |

|

|

| Difficulty retaining sternal recumbency | 227 |

|

| Thoracic limbs paresis or proprioceptive deficits in the absence of an explanatory lesion |

|

Note: Absence of these clinical signs does not preclude later development of PMM and progression of signs in the immediate postoperative period (1–7 days) is key to providing evidence of a clinical diagnosis.

Abbreviations: CTR. cutaneous trunci reflex, IVDE, intervertebral disc extrusion, PMM, progressive myelomalacia.

TABLE 12.

Imaging and clinical biomarkers evaluated in progressive myelomalacia (PMM)

| Feature | References | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| Serum [GFAP] | ||

| Serum (pNfH) | 233 |

|

| Myelography: diffuse intraparenchymal contrast | 58 |

|

| T2 hyperintensity length ratio > 4.57 | 23 |

|

| T2 hyperintensity length > 6 L2 | 24 |

|

| SSTSE CSF:L2 ratio > 7.4 | 25, 227 |

Note: In addition to clinical findings, ante mortem suspicion can be further heightened by findings on MRI and by serum biomarker measurements.

Abbreviations: GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; h, hours; OR, odds ratio; PMM: progressive myelomalacia; pNFH, phosphorylated neurofilament heavy protein.

A combination of clinical findings can support a high level of concern for PMM and, when further coupled with imaging findings and longitudinal monitoring for specific changes in the neurologic examination and serum biomarkers, can be even more highly suggestive of the condition. Supported by moderate‐level evidence.

11.2. Risk factors for PMM

Risk factors for PMM have been evaluated in retrospective studies. 23 , 107 , 229 Injury severity is the most important risk factor, with paraplegic DPN dogs at highest risk for developing PMM. 23 Lesion location also is important, with lumbar intumescence disc extrusions more likely to result in PMM than others. 23 , 107 A retrospective comparison between dachshunds and French bulldogs concluded that French Bulldogs had a higher risk of PMM; however, the study did not control for location of injury and the higher prevalence of lumbar intumescence IVDE in French bulldogs might explain the increased rate of PMM. 229

Dogs with IVDE of the lumbar intumescence, that progress to paraplegic DPN status might be at higher risk for the development of PMM compared to those with lesions at other sites in the thoracic and lumbar spinal cord. Supported low‐level evidence.

Although French bulldogs appear to have a higher incidence of PMM, the study that reported breed‐specific increased risk did not control for other factors that could have contributed to higher numbers of affected French bulldogs. Supported by low‐level evidence.

11.3. Prevention and treatment of progressive myelomalacia