Abstract

Background

Elderly people with presbycusis are at higher risk for dementia and depression than the general population. There is no information regarding consequences of presbycusis in dogs.

Objective

Evaluate the relationship between cognitive function, quality of life, and hearing loss in aging companion dogs.

Animals

Thirty‐nine elderly companion dogs.

Methods

Prospective study. Hearing was evaluated using brainstem auditory evoked response (BAER) testing. Dogs were grouped by hearing ability. Owners completed the canine dementia scale (CADES) and canine owner‐reported quality of life (CORQ) questionnaire. Cognitive testing was performed, and cognitive testing outcomes, CADES and CORQ scores and age were compared between hearing groups.

Results

Nineteen dogs could hear at 50 dB, 12 at 70 dB, and 8 at 90 dB with mean ages (months) of 141 ± 14, 160 ± 16, and 172 ± 15 for each group respectively (P = .0002). Vitality and companionship CORQ scores were significantly lower as hearing deteriorated (6.6‐5.4, 50‐90 dB group, P = .03 and 6.9‐6.2, 50‐90 dB group, P = .02, respectively). Cognitive classification by CADES was abnormal in all 90 dB group dogs and normal in 3/12 70 dB group and 11/19 50 dB group dogs (P = .0004). Performance on inhibitory control, detour and sustained gaze tasks decreased significantly with hearing loss (P = .001, P = .008, P = .002, respectively). In multivariate analysis, higher CADES score was associated with worse hearing (P = .01).

Conclusions and Clinical Importance

Presbycusis negatively alters owner‐pet interactions and is associated with poor executive performance and owner‐assessed dementia severity.

Keywords: canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome, CCDS, cognitive testing, dementia, presbycusis

Abbreviations

- BAER

brainstem auditory evoked response

- CADES

Canine Dementia Scale

- CCDS

canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome

- CMI

clinical metrology instruments

- CORQ

canine owner reported quality of life

- CVM

College of Veterinary Medicine

- dB

decibel

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- QoL

quality of life

1. INTRODUCTION

Age‐related hearing loss, or presbycusis, is a common condition in the elderly human population with serious consequences. It is estimated that one‐third of people over the age 65 experience presbycusis. 1 The rate of cognitive decline is approximately 30% to 40% faster in people with presbycusis 2 and the risk for dementia was highest for people with age‐related hearing loss when compared to other risk factors including hypertension, obesity, and poorer education. 3 The sensory deprivation caused by hearing loss is associated with social isolation and depression, which can lead to a decreased quality of life (QoL) for many elderly individuals. 4 , 5 , 6 However, the use of hearing aids and cochlear implants can counteract progression of presbycusis and help mitigate many of the changes seen with cognitive decline and depression in the elderly population. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10

Presbycusis is also a common phenomenon in the aging process of dogs starting at approximately 8 to 10 years of age, with significant hearing loss occurring in middle to high frequencies when compared to low frequencies. 11 Changes in audiograms can be assessed using brainstem auditory evoked response (BAER) testing. 12 Certain histopathological changes in the human cochlea have been associated with loss of hearing on audiogram profiles. These changes typically are divided into 6 different categories: sensory, neural, metabolic, cochlear conductive, mixed, and indeterminate. 13 Most cases of presbycusis in humans are categorized as mixed although approximately 25% of cases are classified as indeterminate. 13 , 14 , 15 Similarly, sensory, neural, metabolic, and mixed changes have been reported in dogs with presbycusis. 12 , 16 , 17

The consequences of presbycusis in companion animals have not yet been thoroughly studied. A previous study found that owner‐assessed sensory impairment, including hearing loss, resulted in a higher number of problematic behaviors that may reflect canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome (CCDS), 18 but limited information is available regarding the effect of presbycusis on QoL and cognitive function via testing. Various validated methods have been developed to evaluate both QoL and cognitive function in dogs including clinical metrology instruments (CMI) completed by owners and cognitive testing. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 Quality of life is 1 of the most important factors for pet owners when considering end of life decisions. 25 , 26 Previous research has focused on QoL assessment related to treatments or diseases, but no data have been published regarding owner perception of the effect of presbycusis on their pet's QoL. 27 , 28 , 29 Evaluation of cognitive function and QoL in dogs with presbycusis warrants further investigation to improve our understanding and treatment of aging dogs, and to explore the relationship between sensory loss and cognition.

The purpose of our study was to evaluate the relationships among aging, cognitive function, QoL, and hearing loss in old companion dogs. We hypothesized that hearing, as evaluated by BAER testing, would be positively associated with cognitive performance and with the owner's assessment of QoL in aging companion dogs.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study population

Ours was a cross‐sectional study of prospectively recruited companion dogs at the North Carolina (NC) State University College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). Dogs were recruited by contacting owners in the local community and the NC State CVM through emails and postings on the NC State CVM clinical trials website. Dogs were recruited from January 2019 through May 2021. Dogs had to be in the last 25% or beyond their expected lifespan according to American Kennel Club breed standards to participate. 30 Dogs in the last 25% of their expected lifespan were considered senior dogs and dogs beyond their expected lifespan were considered geriatric. American Kennel Club lifespans were determined for mixed breed dogs by matching them to the breed that they most closely resembled within their weight class. To be included in the study, dogs had to be systemically healthy, temperamentally suited to cognitive testing, and food motivated for completion of cognitive and hearing testing. Exclusion criteria included congenital or acquired deafness for genetic or other reasons before reaching the senior age category, recent initiation (defined as <4 weeks) of psychoactive medications that might alter behavioral testing, and severe mobility or visual impairment that would prevent cognitive testing. All protocols were reviewed and approved by the NC State University Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee and all owners reviewed and signed an informed consent form.

2.2. Clinical examination

All dogs underwent general physical, orthopedic, and neurological examinations by a veterinarian, and a CBC, serum biochemistry panel, and urine analysis were performed.

2.3. Auditory testing

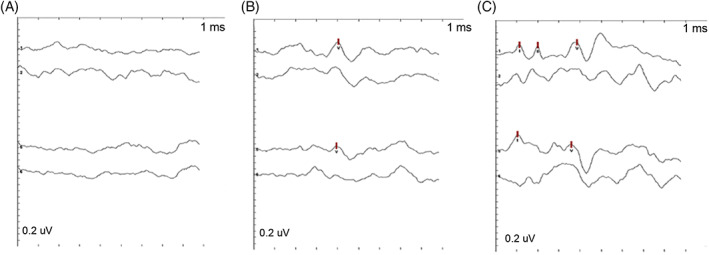

Hearing was assessed in a quiet room using brainstem auditory evoked potentials (Nicolet VikingQuest, Middleton, Wisconsin). Before recording, the external ear canal was examined, and excessive debris was removed manually. Dogs unable to sit still throughout the BAER examination received sedation appropriate for the dog's demeanor and underlying health status. Dogs received either 1 to 7 mg/kg trazodone PO (Teva Laboratories, Pliva, Zagreb, Croatia), 0.01 mg/kg acepromazine IV (Covetrus, Dublin, Ohio), 0.2 mg/kg butorphanol IV (Hospira, Lake Forest, Illinois), 3 μg/kg dexmedetomidine IV (Zoetis, Kalamazoo, Michigan), 20 mg/kg gabapentin PO (Zydus Pharmaceuticals, Pennington, New Jersey), or a combination of these medications before BAER evaluation. The presence of wave V was used to determine whether a dog could hear at a particular decibel (dB) level. Wave V was defined as the wave immediately preceding the deepest trough that occurred approximately 3.5 to 5 ms after stimulation according to normal convention. 31 Wave V is the last waveform to disappear with decreasing stimulus levels and therefore was chosen as the marker of hearing in our study. 32 Reference electrodes were inserted SC over the mastoid process at the base of the vertical ear canal bilaterally. The recording electrode was inserted SC at the vertex. Finally, a ground electrode was inserted SC dorsal to the first cervical vertebra. The electrodes were connected to a preamplifier with 0.15 to 3 kHz bandpass filtering. Tubal inserts with earplugs were seated in both external ear canals to deliver the stimuli. Click stimuli were delivered monaurally at a stimulation rate of 11.4 Hz using an alternating polarity starting at 70 dB. The response to 1000 clicks was recorded and averaged for each recording. A masking noise at 40 dB was used in the non‐stimulated ear in all examinations. If a clear wave V was identified in testing of either ear, the intensity of stimulus was decreased to 50 dB and testing was repeated. If no waveforms were identified at 70 dB, the intensity of stimulus was increased to 90 dB and testing was repeated (Figure 1). Testing was started at 70 dB rather than 50 dB to minimize the number of trials required for testing (3 rather than 2). The veterinarians assessing dogs' hearing were not blinded to the results of the questionnaire scores or performance on cognitive tasks.

FIGURE 1.

Representative brainstem auditory evoked response tracings of a dog. There is an absent wave V at 50 dB (A), however, wave V is identifiable at 70 dB (B) and 90 dB (C).

2.4. Questionnaires

Owners were asked whether they believed their dogs had any hearing problems before BAER evaluation. Owners also were asked to provide any relevant medical history and to include current medications that their dogs were receiving. None of the dogs were noted to have otitis externa that required topical aural treatment at the time of enrollment. Additionally, owners filled out an adapted canine owner‐reported quality of life (CORQ) questionnaire. This scale was validated to measure QoL in dogs being treated for cancer. 24 The questionnaire includes 17 questions assigned to 4 domains which include vitality, companionship, pain, and mobility. One change made to the questionnaire was related to question 5: “My dog's treatment interfered with his/her enjoyment of life.” Instead, the word “treatment” was replaced with “anxiety.” All other questions were related to general changes seen with aging and not specific to cancer treatment or course of disease (Data S1). Each item was scored from 0 to 7 based on the number of days in the past week that the owner witnessed a specific behavior such as decreased appetite, difficulty lying down, or sleeping well at night. The items were scored such that higher scores were associated with a more positive response. The scores for each domain were calculated by averaging the scores of all questions pertaining to the domain. The overall score was the average of all item responses, and all scores ranged from 0 to 7.

To assess cognitive dysfunction, owners completed the canine dementia scale (CADES) questionnaire within 2 weeks of evaluation (Data S2). The CADES questionnaire is a validated CMI used to assess the severity of CCDS based on the owners' perceptions of behavior at home. 19 Owners are asked to answer 17 items related to behavioral changes that evaluate 4 domains—spatial orientation, social interaction, sleep‐wake cycles, and house soiling. Dogs then were assigned different clinical stages of CCDS based on their total score: normal cognitive function (0‐7), mild (8‐23), moderate (24‐44), and severe (45‐95) cognitive impairment.

2.5. Cognitive testing

Clinical cognitive testing was performed at the NC State CVM comparative behavior laboratory. Cognitive testing was performed within 4 weeks of BAER testing. Testing was performed in the same testing room with the same dog handler and was recorded by 2 digital video cameras for future analyses. Cognitive tests including warm‐ups, social cue (pointing), working memory, cylinder tasks (inhibitory control and detour), and sustained gaze methodology are described in Supporting Information (Data S3). All test methods have been described previously. 22 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP15 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Dogs were grouped based on the lowest dB reading with an identifiable wave V (50, 70, or 90 dB) and summary data were generated for each group for age, breed, weight, sex, CORQ, CADES, and cognitive testing. Data for pointing cue and cylinder tasks were expressed as a percentage of correct choices. Data for sustained attention were expressed as the mean timespan (s) of 3 trials. Canine dementia scale was expressed both as a numerical score and as a category, and working memory was expressed as a category. Continuous data are presented as median and range (if not normally distributed) and mean and SD (if normally distributed). Categorical data are expressed as numbers and percentages.

Kruskal‐Wallis tests were used to compare age, outcomes from cognitive testing, and CORQ scores between hearing groups. Chi square analyses were used to compare sex, working memory categories, and CADES categories between hearing groups. The relative risk of dementia in dogs with and without hearing loss was calculated by dividing the proportion of dogs identified as having moderate or severe CCDS on CADES in the 90 dB group by the proportion of dogs in the same CADES categories in the 50 and 70 dB groups. All outcomes that were significant using the Kruskal‐Wallis tests were assessed by pairwise comparisons. Effect sizes were determined using Cohen's d for pairwise comparisons.

The influence of age on relevant cognitive testing, CADES CCDS scores and CORQ scores was examined using simple linear regression. Given the influence of age on cognitive performance and CORQ scores, linear regression models were constructed to incorporate age into multivariate analysis of cognitive testing results, CADES CCDS scores, CORQ scores, and hearing levels. Effect sizes for significant correlations were determined using Cohen's f 2. P values ≤.05 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Dogs

Thirty‐nine dogs (25 spayed females and 14 castrated males) participated in the study. Breeds represented include Labrador retriever (n = 5), beagle (n = 3), border collie (n = 2), golden retriever (n = 2), dachshund (n = 2), American Staffordshire terrier (n = 2), German shepherd dog (n = 1), Jack Russell Terrier (n = 1), Brittany spaniel (n = 1), Siberian husky (n = 1), Bernese mountain dog (n = 1), West Highland white terrier (n = 1), German short‐haired pointer (n = 1), hound (n = 1), and mixed breed (n = 16). The median age of dogs in the study was 156 months (range, 115‐197 months).

All dogs had essentially normal physical examinations, although age‐related changes such as osteoarthritis were common. All dogs were independently mobile, visual, and able to respond to commands. One dog had residual signs of peripheral vestibular disease, 1 dog had a vestibular quality ataxia, and 1 dog had new onset of seizures during enrollment. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) did not identify any structural disease in the dog with ataxia or the dog with seizures. No other dogs had any clinical signs of focal intracranial neurological disease. Otoscopic examination of the external ear canal did not identify any obvious cause for conductive hearing loss in any of the dogs.

Blood testing was performed within 1 week of cognitive testing in 30 dogs and the remaining dogs had blood tests performed within 6 months before testing. The most common findings included mild non‐regenerative anemia, evidence of mild to moderate mixed hepatopathies, and urinary tract infections (all dogs had cultures performed and were treated with antibiotics as necessary before participation). A summary of the results of CBC, biochemistry, and urinalyses for all dogs are provided in Supporting Information (Data [Link], [Link], respectively).

3.2. Auditory testing

Brainstem auditory evoked response testing was completed successfully in all dogs. To complete the BAER test, 15 dogs did not require any form of sedation, whereas the remaining 24 dogs were given some sedation with the drug choice depending on their health status and level of anxiety. Eighteen dogs received trazodone, 2 dogs received dexmedetomidine, 1 dog received gabapentin, 2 dogs received trazodone and dexmedetomidine, and 1 dog received trazodone, acepromazine, and butorphanol. Nineteen dogs had wave V at 50 dB, 12 at 70 dB, and 5 at 90 dB. Two dogs that had no waveforms at 70 dB but were not tested at 90 dB were placed in the 90 dB group, as well as 1 dog that had no waveforms at 90 dB in either ear, to form a group with decreased to absent hearing for statistical analysis. For the dogs in the 50 dB group, 17% of owners thought their dogs had hearing problems, compared with 75% of owners in both the 70 and 90 dB groups. Summary statistics for age, weight, and sex in each hearing group are provided in Table 1. A significant difference in age (P = .0002) was found between hearing groups but not for sex (P = .35) or weight (P = .5). On pairwise comparison between the groups, dogs were significantly older in the 70 and 90 dB groups compared to the 50 dB group (P = .004, d = .54 and P = .0003, d = .73, respectively) but no significant difference in age was found between the 70 and 90 dB groups.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of sex, age, and body weight between hearing groups

| 50 dB group | 70 dB group | 90 dB group | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of dogs | 19 | 12 | 8 | |

| Sex | m = 9, f = 10 | m = 3, f = 8 | m = 2, f = 7 | .35 |

| Age (mean, SD) (m) | 141.1 ± 14.04 | 160.3 ± 15.56 | 172 ± 15.04 | .0002 |

| Weight (mean, SD) (kg) | 21.8 ± 9.54 | 20.89 ± 9.25 | 17.3 ± 7.2 | .5 |

Abbreviations: dB, decibel; f, females; m, males; m, months.

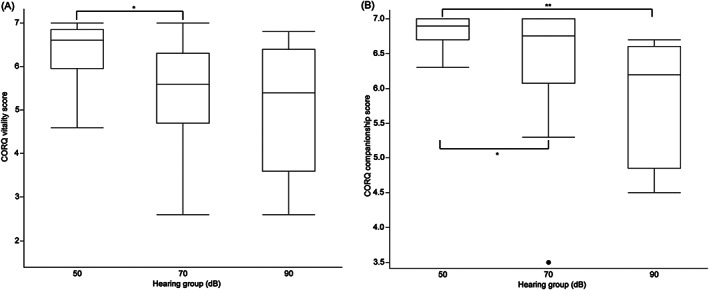

3.3. Quality of life assessment

The CORQ was completed by 35/39 (89.7%) of owners. Three of the dogs without a CORQ were in the 90 dB group and the remaining dog was in the 50 dB group. No significant difference in total CORQ scores was found between hearing groups (Table 2). Of the 4 CORQ domains, a significant difference was found between hearing groups in the domains of vitality (P = .03) and companionship (P = .02) with both vitality and companionship scores decreasing as hearing thresholds increased (hearing loss; Table 2). Pairwise comparisons between groups identified significantly higher CORQ vitality scores for dogs in the 70 and 90 dB groups compared to the 50 dB groups (P = .02, d = .43 and P = .004, d = .59, respectively; Figure 2A). Similarly, a significantly higher CORQ companionship score was found for dogs in the 50 dB group compared to the 90 dB group (P = .004, d = 1.44; Figure 2B). No differences in scores for pain (P = .05) and mobility (P = .17) domains were found between hearing groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Canine Owner‐Reported Quality of Life questionnaire results between hearing groups

| 50 dB group | 70 dB group | 90 dB group | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORQ total (median) (range) | 6.62 (4.88‐7) | 5.91 (3.47‐6.82) | 6 (3.12‐6.82) | .06 |

| CORQ vitality (median) (range) | 6.6 (4.6‐7) | 5.6 (2.6‐7) | 5.4 (2.6‐6.8) | .03 |

| CORQ comp (median) (range) | 6.9 (6.3‐7) | 6.75 (3.5‐7) | 6.2 (4.5‐6.7) | .02 |

| CORQ pain (median) (range) | 6.5 (4‐7) | 5.25 (3.5‐7) | 5.5 (3.5‐7) | .05 |

| CORQ mobility (median) (range) | 6.63 (3‐7) | 5.5 (1.5‐7) | 5.5 (0.5‐7) | .17 |

Note: Higher CORQ scores indicate better perceived quality of life.

Abbreviations: comp, companionship; CORQ, Canine Owner‐Reported Quality of Life; dB, decibel.

FIGURE 2.

Box plots showing Canine Owner‐Reported Quality of Life of the (A), vitality and (B), companionship domain scores for dogs in the 50, 70, and 90 dB hearing groups. The horizontal line within the boxplot represents the median, the ends of the box represent the interquartile range, the upper and lower whisker extend 1.5 × interquartile range from the top and bottom of the box. Lines labeled with * denote a significance of P < .05 between hearing group and lines labeled with ** denote a significance of P < .01 between hearing groups.

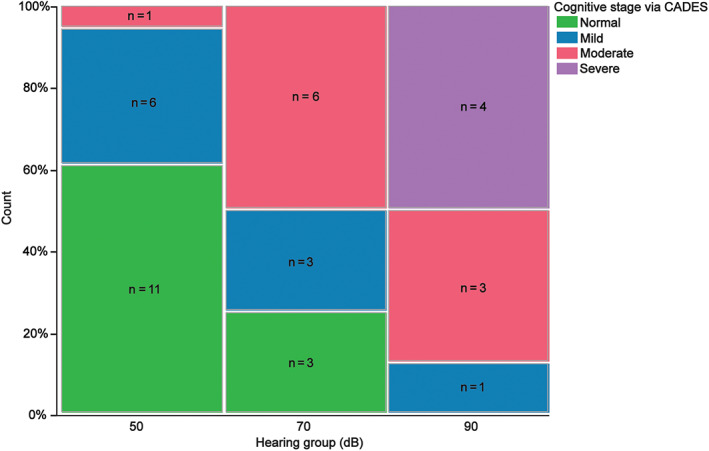

3.4. Cognitive dysfunction assessment by CADES

Owner‐completed CADES scoring classified 4 dogs as having severe CCDS, 10 dogs as having moderate CCDS, 11 dogs as having mild CCDS, and 13 dogs as normal. One owner of a dog in the 50 dB group did not fill out the CADES questionnaire. All dogs identified as severe CCDS fell into the 90 dB group. Of the normal dogs, 11/13 (84.6%) could hear at 50 dB whereas the other 2 could hear at 70 dB (Figure 3). A significant difference in CADES scores was found across hearing groups (P = .0004; Table 3). The relative risk for dogs in the 90 dB group to be identified as moderate or severe CCDS on CADES was 3.88.

FIGURE 3.

Clinical stage of cognitive dysfunction syndrome as assessed by Canine Dementia Scale for dogs in each hearing group. Green stacked bars show the relative count of dogs that were identified as normal, blue stacked bars show the relative count of dogs that were identified as mildly affected, red stacked bars show the relative count of dogs that were identified as moderately affected, and purple stacked bars show the relative count of dogs that were identified as severely affected.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of CADES scoring and cognitive testing results between hearing groups

| 50 dB group | 70 dB group | 90 dB group | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CADES score (range) | 6 (0‐40) | 26.5 (3‐44) | 41 (21‐70) | .0004 |

| Pointing cue (avg % of correct choices) (range) | 83 (17‐100) | 87.5 (58‐100) | 92 (83‐100) | .74 |

| Working memory (Grade 1, <20 s), (Grade 2, 20‐60 s), (Grade 3, >60 s) | Grade 1, n = 5 | Grade 1, n = 2 | Grade 1, n = 2 | .80 |

| Grade 2, n = 7 | Grade 2, n = 5 | Grade 2, n = 3 | ||

| Grade 3, n = 4 | Grade 3, n = 1 | Grade 1, n = 1 | ||

| Inhibitory control (avg % of correct trials) (range) | 100 (63‐100) | 88 (13‐100) | 50 (0‐88) | .001 |

| Detour (avg % of correct trials) (range) | 75 (0‐100) | 38 (0‐75) | 13 (0‐50) | .008 |

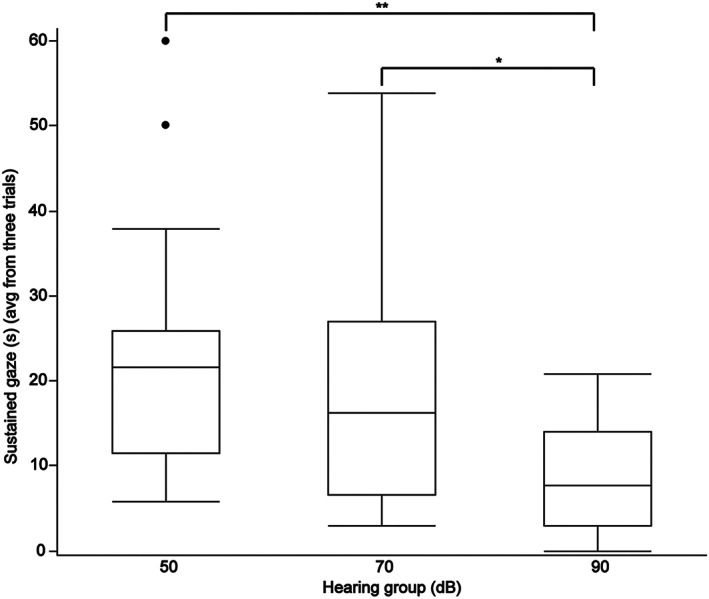

| Sustained gaze (avg from three trials) (range) (s) | 21.72 (5.83‐60) | 16.23 (2.99‐53.8) | 7.7 (0‐20.75) | .02 |

Abbreviations: CADES, Canine Dementia Scale; dB, decibel; s, seconds.

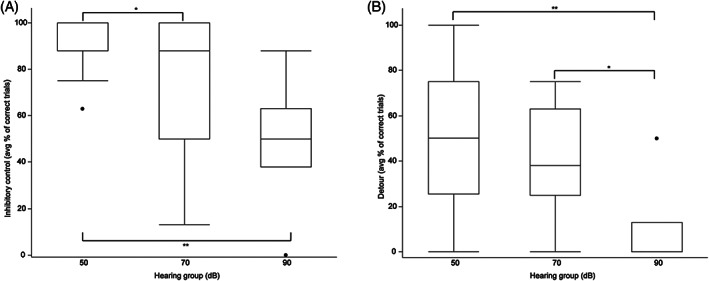

3.5. Cognitive test results

Thirty‐one of 39 dogs passed the warm‐up criteria for pointing and working memory tasks. Of the 8 dogs that failed the warm‐up tasks, 4 were in the 90 dB group, 2 were in the 70 dB group, and the remaining 2 dogs were in the 50 dB group. Six of the dogs that did not pass the warm‐ups failed to meet the threshold criteria. The 2 other dogs displayed anxious behaviors such as avoiding treats and seeking the door. The performance outcomes of each hearing group for each cognitive test are provided in Table 3. Performance on the pointing cue and working memory tasks was not significantly different among the hearing groups but a significant decrease in performance was observed on inhibitory control (P = .001), detour (P = .01), and sustained gaze (P = .02) tasks as hearing deteriorated (Table 3).

Thirty‐five of 39 dogs passed the warm‐up criteria for cylinder tasks. Of the 4 dogs that failed, 2 were in the 50 dB group, 1 was in the 70 dB group, and 1 was in the 90 dB group. One of the dogs in the 50 dB group was too anxious to approach the unfamiliar cylinder despite repeated familiarization trials; the remaining dogs could not understand the objective and did not retrieve the treat during familiarization trials. All dogs completed the sustained gaze task. Pairwise comparisons among groups further emphasized the deterioration in task performance among groups for inhibitory control (Figure 4A), detour (Figure 4B), and sustained gaze (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Box plots showing results of testing of (A), inhibitory control, and (B), detour in the 50, 70, and 90 dB hearing groups. The horizontal line within the boxplot represents the median, the ends of the box represent the interquartile range, the upper and lower whisker extend 1.5 × interquartile range from the top and bottom of the box. Lines labeled with * denote a significance of P < .05 between hearing groups and lines labeled with ** denote a significance of P < .01 between hearing groups.

FIGURE 5.

Box plots showing results of testing of sustained gaze, in the 50, 70, and 90 dB hearing groups. The horizontal line within the boxplot represents the median, the ends of the box represent the interquartile range, the upper and lower whisker extend 1.5 × interquartile range from the top and bottom of the box. Lines labeled with * denote a significance of P < .05 between hearing groups and lines labeled with ** denote a significance of P < .01 between hearing groups.

3.6. Relationships among hearing threshold, age, CORQ, CADES, and cognitive testing

Multivariate analysis was performed for CORQ vitality and companionship scores, CADES scores, inhibitory control, and detour performance, with age and hearing groups as covariates (Table 4). Higher CADES score was significantly associated with worse hearing (P = .01, f 2 = 1.5). Higher CADES score, worse CORQ domain scores, and worse inhibitory control performance all were associated with higher age (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Summary of multivariate analysis of relevant CORQ scores, CADES, and cognitive testing outcomes with hearing groups and age as covariates

| CORQ vitality | CORQ comp | CADES score | Inhibitory control | Detour | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hearing group | P = .65 | P = .66 | P = .01 | P = .12 | P = .08 |

| Age | P = .007 | P = .02 | P = .01 | P = .05 | P = .36 |

Abbreviations: CADES, Canine Dementia Scale; CCDS, canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome; Comp, companionship; CORQ, Canine Owner‐Reported Quality of Life.

4. DISCUSSION

We investigated the relationships among presbycusis, QoL, owner‐quantified CCDS and cognitive testing performance in dogs. Similar to previous findings, 11 , 12 , 16 , 37 our study suggests that presbycusis is prevalent in aging companion dogs. Owner assessment of QoL in the domains of vitality and companionship were both significantly associated with hearing loss, as were CCDS (as determined by CADES) and age. Specific executive control tasks were associated with hearing loss, whereas other tasks such as pointing cue (considered a social cue task) and working memory were not. Once the effect of age was taken into account in multivariate analysis, the significant association between CCDS severity and hearing loss was maintained.

Dog owners often are aware of changes in hearing as their pets age. Owners identified deficits in hearing in 75% of dogs in the 70 and 90 dB groups. By contrast, 83% of owners whose dogs tested in the 50 dB group believed their dogs' hearing was normal. However, the impact of presbycusis on QoL can be more challenging to assess. Quality of life in dogs is measured by a human proxy through interpretation of the pet's behavior. Our results show that scores of the vitality and companionship domains were significantly lower in dogs with hearing loss. These findings suggest that the quality of interactions between dogs and their owners declines as dogs' hearing declines. This change in perceived QoL is similar to findings in people with presbycusis. Moreover, the use of hearing aids in people experiencing presbycusis produces significant improvements in QoL. 7 , 9 , 10 , 38 In the absence of using hearing aids to assess improvements in QoL, a longitudinal study to track changes in hearing and owner‐assessed QoL domains is warranted.

Dogs have been shown to respond differently based on tones of human voices 39 , 40 and our findings suggest that the interaction between dogs and their owners is affected by hearing loss. However, dogs in all 3 hearing categories performed similarly on the pointing task, which is a test of social cue recognition and does not require hearing. It is possible that dogs' use of visual cues may mitigate some of the impact of hearing loss, but owners did perceive a reduction in QoL regarding companionship in dogs with hearing loss, suggesting a similar impact on social functioning as encountered by people with hearing loss. 41

We found a significant association between hearing loss and severity of CCDS as defined by CADES scoring in both univariate and multivariate analyses. The risk factors for CCDS currently are not well established. In contrast, numerous risk factors for dementia have been established in people including, but not limited to, hearing loss, level of education, hypertension, excessive alcohol consumption, obesity, smoking, depression, and systemic disease (ie, diabetes). 3 The only potential risk factors previously identified in dogs for developing CCDS as assessed by CADES were aging and eating an uncontrolled diet (table scraps, mixture of diets, or low‐quality commercial food), whereas other factors such as weight, sex, reproductive status, and housing type were not significantly associated with cognitive impairment. 42 Another study, which used the canine cognitive dysfunction rating scale to assess for cognitive impairment in dogs >7 years old, did not find any significant differences in normal dogs and dogs with CCDS with factors such as age, breed, sex, body weight, reproductive status, nutrition, and medications. 43 We believe that presbycusis could be a newly identified risk factor in dogs for development of CCDS based on CADES scoring and reduction in executive function test performance. However, we recognize that there may be an inherent bias in owner‐reported CADES for dogs with hearing loss because some behaviors observed at home may be solely caused by presbycusis rather than representing true cognitive dysfunction. Unfortunately, without the use of hearing aids in dogs with presbycusis to observe for any immediate changes in behavior, it may be very difficult to determine the degree of owner reported bias when filling out the CADES questionnaire. Therefore, future studies should track changes in hearing and CADES longitudinally to investigate this relationship further.

The CADES questionnaire captures observations of owners on behavioral changes in their dogs at home, but does not quantify performance in specific cognitive domains. To determine which cognitive domains might be affected by hearing loss, we performed testing of executive function, response to social cues and working memory with these dogs in our laboratory. One cognitive domain impacted by age‐related hearing loss in people is proficiency on working memory tests, especially those administered by verbal stimuli. 6 , 44 The use of hearing aids improves performance on memory tasks and slows decline in memory task performance for tests that rely on verbal stimuli. 8 , 45 In contrast, we did not find a significant difference between performance on working memory and hearing ability. One explanation is that our testing relied almost entirely on visual stimuli to test for working memory. Performance on short term memory tests that rely on visual stimuli in people are not always associated with degree of hearing loss. 46 , 47 , 48 The differences between outcomes using visual and auditory focused working memory tests might be explained by the cognitive load hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, people with hearing loss devote more cognitive resources to understand speech, which in turn diverts available resources away from other processes such as a working memory task. 49 Therefore, tests that rely on hearing for memory testing may be more affected by presbycusis than tests that rely on visual changes. Studies with working memory tests that use different forms of stimuli may help elucidate how presbycusis affects memory in dogs.

Executive function testing by means of the cylinder task (impulse control and detour tasks) disclosed significant differences among hearing groups and performance in univariate analysis. In pairwise analysis, a significant change in performance was found for dogs that fell in the 50 dB category and those that did not. This observation may indicate that a threshold in hearing loss exists that is associated with poorer performance on executive function tasks. In multivariate analyses with age as a covariate, age was the only variable significantly associated with inhibitory control performance, suggesting that a larger population of participants is required to explore the relationships among executive control, aging, and hearing in dogs further. Data about the relationship between peripheral presbycusis and executive control is mixed in humans. Some reports indicate that hearing loss is not associated with decline in executive functions. 48 , 50 People with hearing aids, however, experience improvements in executive functioning tasks. 6 , 8

Poorer hearing was associated with worse performance on another test of executive function, the sustained attention task, although this association was not significant on a multivariate analysis. This finding mirrors observations in humans in which cognitive decline is associated with poor performance on attention tasks. 50 One confounding factor for performance on the sustained attention task is the influence of external noises on the ability to maintain concentration. Although trials with obvious distractions were excluded, the room in which testing was performed could not be completely sound proofed. In this instance, presbycusis could mitigate distractions and potentially improve performance on this test. Despite this, the dogs with hearing loss performed worse, and the potential relationship between attention and hearing loss deserves further evaluation in a larger population of dogs. The results of our cognitive testing data suggest that using different strategies for interactions at home (such as visual or physical cues) may help dogs with hearing loss in slowing their cognitive decline and this possibility should be further investigated in future studies.

Our study had some limitations. Firstly, our study was cross‐sectional in nature. The role of hearing loss in development of cognitive decline in dogs should be investigated in a longitudinal study to track for changes in hearing and observe whether these changes occur before, concurrent with, or after cognitive decline. Furthermore, the effect of hearing loss on cognition in people can be evaluated readily by use of hearing aids. Middle ear implants have been used experimentally in 3 aged dogs with presbycusis and did improve their hearing. 51 However, such implants are not readily available, and hearing aids for dogs are not used commonly, in part because they are poorly tolerated. This is likely to change in the future and the introduction of well‐tolerated, affordable hearing aids for dogs will enhance our understanding of the effects of presbycusis on cognition and QoL in dogs.

Second, our study assessed the integrity of the peripheral and brainstem structures in the hearing pathway, but not cortical perception. Increasing evidence in humans indicates that processing of speech can be affected not only by peripheral presbycusis, which is assessed by BAER, but also by central presbycusis. A recent task force defined central presbycusis as age‐related changes in the auditory portions of the central nervous system negatively impacting auditory perception, speech communication performance, or both. 52 Central presbycusis also may increase the risk of development of Alzheimer's disease and progression of dementia. 53 A reliable test of the central pathways that mediate a conscious response to auditory stimuli in pet dogs is needed. Although late BAER waveforms represent pathways projecting to the thalamus and cortex, they are difficult to quantify reliably. We recorded owner assessments of their dogs' hearing with the hope it might provide insight into central presbycusis when paired with BAER results. A subset of owners of dogs in the 50 dB group felt their dogs had a hearing problem without any evidence of presbycusis on BAER testing. Common complaints by these owners included failure of the dog to respond to its name, especially when outdoors, which often can be considered a noisy environment. Further work on the relationship between cognitive function and failure to respond to commands in the absence of diminished BAER is required for evaluation of central presbycusis in dogs.

Another limitation was the constraints of working with senior and geriatric companion dogs. A primary concern of the study was to obtain useful hearing tests while avoiding the risks of heavy sedation or anesthesia in these dogs. Dogs only received the minimum amount of sedation required for completion of the BAER test and would only tolerate testing 2 or 3 times. Hence, dogs were only tested at 3 different dB levels, using a click rather than specific tones. Future studies may benefit from correlating cognitive testing and QoL with a complete audiogram. Additionally, analysis of the BAER tracings was simplified to ensure consistency categorizing by the presence or absence of wave V in a minimum of 1 ear. Subtle changes in auditory evoked potentials exist such as changes in latency and amplitude. In humans, although the latency of wave V increased insignificantly with aging, the amplitudes of all waves were substantially decreased. 54 Dogs of different breeds, however, have very different head and ear canal sizes and shapes. Our study featured a wide distribution of breeds and sizes of dogs. Some studies have identified a significant relationship between latency and amplitudes of certain waves and the size of the dog's head. 55 , 56 Fortunately, most of our test subjects have been enrolled in a longitudinal study, and the dogs will have repeated BAER examinations approximately every 6 months. Changes in latency and amplitude will be tracked over time for each dog and for each ear to improve our analysis. Finally, we used a QoL questionnaire developed for cancer patients that has not been validated for our population of dogs. A single question was specifically related to cancer and asked whether treatment had any effect on the pet's enjoyment of life. Because anxiety is commonly seen in dogs with CCDS and may impact life, we felt this substitution was reasonable. Otherwise, the questionnaire evaluated changes in domains (vitality, companionship, pain, and mobility) that are extremely relevant to changes associated with aging and therefore we felt it was reasonable to use it in our study.

In summary, aging is associated with hearing loss in companion dogs. Much like people who experience social isolation and depression with presbycusis, dog owners perceive a difference in particular aspects of their dog's QoL. Our data found that hearing loss was associated with severity of cognitive dysfunction as scored by CADES as well as poorer performance on certain cognitive tests of executive function. Hearing loss may be a field in which intervention could slow the progression of CCDS and therefore the relationships among presbycusis, aging, and dementia deserve further investigation in dogs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Approved by the North Carolina State University IACUC, protocol number 18‐109‐O.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Supporting information

Data S1 CORQ Scale

Data S2 CORQ Questionnaire

Data S3 Questionnaires and Plasma Biomarkers to Quantify Cognitive Impairment in an Aging Pet Dog Poulation

Data S4 CBC Findings for Study Dogs

Data S5 Chemistry Findings for Study Dogs

Data S6 Urinalysis Findings for Study Dogs

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Supported by the Dr. Kady M. Gjessing and Rhanna M. Davidson Distinguished Chair of Gerontology.

Fefer G, Khan MZ, Panek WK, Case B, Gruen ME, Olby NJ. Relationship between hearing, cognitive function, and quality of life in aging companion dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2022;36(5):1708‐1718. doi: 10.1111/jvim.16510

Margaret E. Gruen and Natasha J. Olby are joint senior authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shen Y, Ye B, Chen P, et al. Cognitive decline, dementia, Alzheimer's disease and presbycusis: examination of the possible molecular mechanism. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:1‐14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:293‐299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396:413‐446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ciorba A, Bianchini C, Pelucchi S, Pastore A. The impact of hearing loss on the quality of life of elderly adults. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:159‐163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BEK, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43:661‐668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ray J, Popli G, Fell G. Association of cognition and age‐related hearing impairment in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:876‐882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McArdle R, Chisolm TH, Abrams HB, Wilson RH, Doyle PJ. The WHO‐DAS II: measuring outcomes of hearing aid intervention for adults. Trends Amplif. 2005;9:127‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Castiglione A, Benatti A, Velardita C, et al. Aging, cognitive decline and hearing loss: effects of auditory rehabilitation and training with hearing aids and cochlear implants on cognitive function and depression among older adults. Audiol Neurootol. 2016;21:21‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Acar B, Yurekli MF, Babademez MA, Karabulut H, Karasen RM. Effects of hearing aids on cognitive functions and depressive signs in elderly people. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52:250‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lotfi Y, Mehrkian S, Moossavi A, Faghih‐Zadeh S. Quality of life improvement in hearing‐impaired elderly people after wearing a hearing aid. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:365‐370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ter Haar G, Venker‐van Haagen AJ, van den Brom WE, et al. Effects of aging on brainstem responses to toneburst auditory stimuli: a cross‐sectional and longitudinal study in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2008;22:937‐945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ter Haar G, de Groot JCMJ, Venker‐van Haagen AJ, et al. Effects of aging on inner ear morphology in dogs in relation to brainstem responses to toneburst auditory stimuli. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23:536‐543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schuknecht HF, Gacek MR. Cochlear pathology in presbycusis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:1‐16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gates GA, Mills JH. Presbycusis. Lancet. 2005;366:1111‐1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boettcher FA. Presbyacusis and the auditory brainstem response. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002;45:1249‐1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shimada A, Ebisu M, Morita T, et al. Age‐related changes in the cochlea and cochlear nuclei of dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 1998;60:41‐48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Knowles K, Blauch B, Leipold H, Cash W, Hewett J. Reduction of spiral ganglion neurons in the aging canine with hearing loss. J Vet Med. 1989;36:188‐199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Szabó D, Miklósi Á, Kubinyi E. Owner reported sensory impairments affect behavioural signs associated with cognitive decline in dogs. Behav Processes. 2018;157:354‐360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Madari A, Farbakova J, Katina S, et al. Assessment of severity and progression of canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome using the CAnine DEmentia Scale (CADES). Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2015;171:138‐145. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Salvin HE, McGreevy PD, Sachdev PS, et al. The canine cognitive dysfunction rating scale (CCDR): a data‐driven and ecologically relevant assessment tool. Vet J. 2011;188(3):331‐336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heckler MCT, Tranquilim MV, Svicero DJ, Barbosa L, Amorim RM. Clinical feasibility of cognitive testing in dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). J Vet Behav. 2014;9:6‐12. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bray EE, Gruen ME, Gnanadesikan GE, et al. Cognitive characteristics of 8‐to 10‐week‐old assistance dog puppies. Anim Behav. 2020;166:193‐206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bray EE, Maclean EL, Hare BA. Context specificity of inhibitory control in dogs. Anim Cognit. 2014;17:15‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giuffrida MA, Brown DC, Ellenberg SS, Farrar JT. Development and psychometric testing of the Canine Owner‐Reported Quality of Life questionnaire, an instrument designed to measure quality of life in dogs with cancer. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;252:1073‐1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oyama MA, Rush JE, O'Sullivan ML, et al. Perceptions and priorities of owners of dogs with heart disease regarding quality versus quantity of life for their pets. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;233:104‐108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reynolds CA, Oyama MA, Rush JE, et al. Perceptions of quality of life and priorities of owners of cats with heart disease. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:1421‐1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Silva NEOF, Luna SPL, Joaquim JGF, Coutinho HD, Possebon FS. Effect of acupuncture on pain and quality of life in canine neurological and musculoskeletal diseases. Can Vet J. 2017;58:941‐951. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Belshaw Z, Yeates J. Assessment of quality of life and chronic pain in dogs. Vet J. 2018;239:59‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schofield I, O'Neill DG, Brodbelt DC, et al. Development and evaluation of a health‐related quality‐of‐life tool for dogs with Cushing's syndrome. J Vet Intern Med. 2019;33:2595‐2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bartges J, Boynton B, Vogt AH, et al. AAHA canine life stage guidelines. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2012;48:1‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marshall AE. Brain stem auditory‐evoked response of the nonanesthetized dog. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:966‐973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Poncelet L, Deltenre P, Coppens A, Michaux C, Coussart E. Brain stem auditory potentials evoked by clicks in the presence of high‐pass filtered noise in dogs. Res Vet Sci. 2006;80:167‐174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. MacLean EL, Herrmann E, Suchindran S, Hare B. Individual differences in cooperative communicative skills are more similar between dogs and humans than chimpanzees. Anim Behav. 2017;126:41‐51. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bray EE, Gruen ME, Gnanadesikan GE, et al. Dog cognitive development: a longitudinal study across the first 2 years of life. Anim Cogn. 2021;3:311‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoel JA, Templeton GB, Fefer G, et al. Sustained gaze is a reliable in‐home test of attention for aging pet dogs. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:819135. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.819135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fefer G, Panek WK, Khan MZ, et al. Use of cognitive testing, questionnaires and plasma biomarkers to quantify cognitive impairment in an aging pet dog population. J Alzheimers Dis. 2022;87:1367‐1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Knowles KE, Cash WC, Blauch BS. Auditory‐evoked responses of dogs with different hearing abilities. Can J Vet Res. 1988;52:394‐397. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boi R, Racca L, Cavallero A, et al. Hearing loss and depressive symptoms in elderly patients. Geratr Gerontol Int. 2012;12:440‐445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Albuquerque N, Guo K, Wilkinson A, Savalli C, Otta E, Mills D. Dogs recognize dog and human emotions. Biol Lett. 2016;12:20150883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Scheider L, Grassmann S, Kaminski J, Tomasello M. Domestic dogs use contextual information and tone of voice when following a human pointing gesture. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fischer ME, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BEK, Klein R, Schubert CR, Wiley TL. Multiple sensory impairment and quality of life. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2009;16:346‐353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Katina S, Farbakova J, Madari A, et al. Risk factors for canine cognitive dysfunction syndrome in Slovakia. Acta Vet Scand. 2016;58:1‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ansari Mood M, Rafie SM, Masouleh MN, Aldavood SJ. Prevalence and risk factors of “cognitive dysfunction syndrome” in geriatric dogs in Tehran. J Vet Behav. 2018;26:61‐63. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rong H, Lai X, Jing R, Wang X, Fang H, Mahmoudi E. Association of sensory impairments with cognitive decline and depression among older adults in China. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Maharani A, Dawes P, Nazroo J, et al. Longitudinal relationship between hearing aid use and cognitive function in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:1130‐1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rönnberg J, Danielsson H, Rudner M, et al. Hearing loss is negatively related to episodic and semantic long‐term memory but not to short‐term memory. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2011;54:705‐726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Loughrey DG, Parra MA, Lawlor BA. Visual short‐term memory binding deficit with age‐related hearing loss in cognitively normal older adults. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rosemann S, Thiel CM. Neural signatures of working memory in age‐related hearing loss. Neuroscience. 2020;429:134‐142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Uchida Y, Sugiura S, Nishita Y, Saji N, Sone M, Ueda H. Age‐related hearing loss and cognitive decline — The potential mechanisms linking the two. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019;46:1‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Loughrey DG, Kelly ME, Kelley GA, Brennan S, Lawlor BA. Association of age‐related hearing loss with cognitive function, cognitive impairment, and dementia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:115‐126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. ter Haar G, Mulder JJ, Venker‐van Haagen AJ, et al. Treatment of age‐related hearing loss in dogs with the vibrant soundbridge middle ear implant: short‐term results in 3 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:557‐564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Humes LE, Dubno JR, Gordon‐Salant S, et al. Central presbycusis: a review and evaluation of the evidence. J Am Acad Audiol. 2012;23:635‐666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Panza F, Lozupone M, Sardone R, et al. Sensorial frailty: age‐related hearing loss and the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in later life. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2019;10:1‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Konrad‐Martin D, Dille MF, McMillan G, et al. Age‐related changes in the auditory brainstem response. J Am Acad Audiol. 2012;23:18‐35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Meij BP, Venker‐van Haagen AJ, van den Brom WE. Relationship between latency of brainstem auditory‐evoked potentials and head size in dogs. Vet Q. 1992;14:121‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pook HA, Steiss JE. Correlation of brain stem auditory‐evoked responses with cranium size and body weight of dogs. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51:1779‐1783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 CORQ Scale

Data S2 CORQ Questionnaire

Data S3 Questionnaires and Plasma Biomarkers to Quantify Cognitive Impairment in an Aging Pet Dog Poulation

Data S4 CBC Findings for Study Dogs

Data S5 Chemistry Findings for Study Dogs

Data S6 Urinalysis Findings for Study Dogs