Abstract

Background

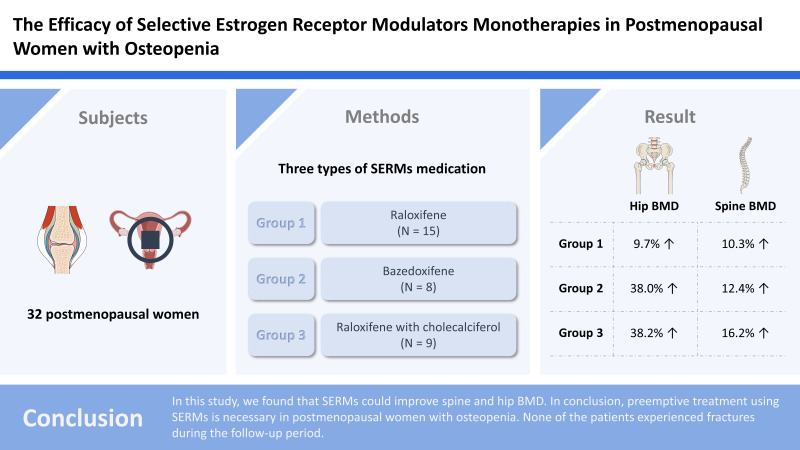

The impact of osteopenia as a risk factor for fractures is underrecognized. Moreover, the efficacy of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in postmenopausal women with osteopenia is limited. This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of SERMs in postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

Methods

Thirty-two postmenopausal women with osteopenia were treated with 3 types of SERMs medication: raloxifene (group I, N=15), bazedoxifene (group II, N=8), and raloxifene with cholecalciferol (group III, N=9). Bone mineral density (BMD) was measured using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry scans before treatment to after 3 years of treatment once a year.

Results

Patients in group I showed significant increases in hip BMD, −1.93 to −1.73 and spine BMD, −1.85 to −1.67. In addition, patients in groups II and III showed significant increases in hip BMD, −1.93 to −1.69 and −2.22 to −1.86, respectively and spine BMD, −2.1 to −1.3 and −2.22 to −1.37, respectively. The BMD increased in the hip and spine by 9.7% and 10.3%, respectively in group I, 38.0% and 12.4%, respectively in group II, and 38.2% and 16.2%, respectively in group III.

Conclusions

In this study, we found that SERMs could improve spine and hip BMD. In conclusion, preemptive treatment using SERMs is necessary for postmenopausal women with osteopenia. None of the patients experienced fractures during the follow-up period.

Keywords: Postmenopause, Raloxifene hydrochloride, Selective estrogen receptor modulators, Vitamin D

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Osteoporosis is a systemic and progressive skeletal disease characterized by reduced bone density, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and long-term fracture risk.[1] Due to the increase in mortality rate after osteoporotic fractures, those are emerging as a socioeconomic problem.[2] Osteopenia is a precursor of osteoporosis and is defined as a bone mineral density (BMD) between 1.0 and 2.5 standard deviations below the mean of peak bone mass in healthy, young normal people (T-score between −1.0 and −2.5).[3] The prevalence of osteopenia ranges from 27.1% to 51.6%, with a reportedly high prevalence among postmenopausal women in Asian countries, where the population is aging rapidly.[4–6] Compared with osteoporosis, the impact of osteopenia as a risk factor for fractures is under-recognized. A recent study suggests that osteopenia is also a significant risk factor for fragility fractures in older women.[7] Moreover, a large community-based study in the U.S. reported that about half of all fragility fractures occur in women who were diagnosed osteopenia.[8,9] For osteoporosis patients, selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are widely used and their efficacy has been proven.[10–12] However, medication efficacy of SERMs for postmenopausal women with osteopenia is limited. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of SERMs in postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

METHODS

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at our hospital (IRB no. 2022-07-003). From January 2012 to May 2019, 97 postmenopausal osteopenia women patients were enrolled. Women with BMD between 1.0 and 2.5 standard deviations below peak bone mass for healthy premenopausal women were included, regardless of the presence of prevalent vertebral fractures. Among them with following conditions were excluded, (1) current bone disorders other than postmenopausal osteoporosis; (2) history of endometrial hyperplasia or gynecological diseases that could be adversely affected by SERMs; (3) history of cancer in the last 5 years; (4) active venous thromboembolic disease, and endocrine disorders requiring pharmacologic therapy, except type II diabetes.

Thirty-two postmenopausal women, who were diagnosed with osteopenia, were allocated to one of 3 treatment groups and monitored for 3 years. All patients were treated by SERMs and 3 types of medication were used: raloxifene (60 mg/day; group I, N=15), bazedoxifene (20 mg/day; group II, N=8) and raloxifene (60 mg/day) with cholecalciferol (8 mg/day; group III, N=9). BMD was measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan (Horizon DXA system; Hologic Inc., Marlborough, MA, USA), from before treatment to after 3 years of treatment once a year.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for the determination of data normality. Comparisons of variables between time points within each group were performed using a Wilcoxon signed rank test according to the number of comparisons. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was set at P value less than 0.05.

RESULTS

The average follow-up duration was 40.1 months (range, 36–78). The mean age of the patients was 60.3 years (range, 48–72) with a mean body mass index of 23.1±4.1 kg/m2. The time from menopause was a mean of 7.3 years (range, 3.3–11.3). The mean period of treatment was 3.7 years (range, 3–5). The drug adherence rate for group I was 87.3% (standard deviation [SD], 11.0) the rate for group II was 88.7% (SD, 5.7) and the rate for group III was 85.3% (SD, 7.4). There was no significant difference between the 3 groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic data for participants

| Group I (N=15) | Group II (N=8) | Group III (N=9) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 60.8±5.4 | 52.2±4.3 | 67±6.2 | 0.611 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.9±1.1 | 19.8±1.3 | 19.4±0.9 | 0.642 |

| Drug adherence rate (%) | 87.3±11.0 | 88.7±5.7 | 85.3±7.4 | 0.211 |

BMI, body mass index.

Patients in group I showed significant increases in hip BMD, −1.93 to −1.73 and spine BMD, −1.85 to −1.67. Also, patients in group II and group III showed significant increases in hip BMD, −1.93 to −1.69, −2.22 to −1.86 and spine BMD, −2.1 to −1.3, −2.22 to −1.37 (Table 2). In group I, BMD increased in the hip and spine by 9.7% (P=0.035) and 10.3% (P=0.021). In group II, were increased 38.0% (P=0.046) and 12.4% (P=0.032), in group III, were increased 38.2% (P=0.048) and 16.2% (P=0.002) in hip and spine, respectively. In group III, BMD was increased the larger than other groups (Table 3). All patients did not have any fractures during the follow-up period.

Table 2.

Changes in BMD during treatment

| Baseline | 3 years after | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip BMD | |||

| Group I | −1.93±0.25 | −1.73±0.33 | 0.018 |

| Group II | −1.93±0.32 | −1.69±0.20 | 0.034 |

| Group III | −2.22±0.19 | −1.86±0.17 | 0.042 |

|

| |||

| Spine BMD | |||

| Group I | −1.85±0.31 | −1.67±0.22 | <0.001 |

| Group II | −2.10±0.22 | −1.30±0.27 | 0.023 |

| Group III | −2.22±0.20 | −1.37±0.24 | 0.031 |

BMD, bone mineral density.

Table 3.

Percentage changes in BMD from baseline at 3 years

| Characteristics | Group I | Group II | Group III |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hip BMD | 9.7±1.0 | 38.0±4.2 | 38.2±4.5 |

| P-value | 0.035 | 0.046 | 0.048 |

|

| |||

| Spine BMD | 10.3±1.1 | 12.4±1.2 | 16.2±1.3 |

| P-value | 0.021 | 0.032 | 0.002 |

BMD, bone mineral density.

DISCUSSION

Fractures are a major complication of osteopenia and osteoporosis. The 10-year cumulative incidence of fragility fractures was 44.3% in women with osteoporosis.[7] Moreover, according to the 2020 report of the Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research, osteoporotic fractures are associated with functional limitation and excess mortality of 17%.[13] Osteopenia can progress to osteoporosis if left untreated. Baek et al. [7] reported that the 10-year cumulative incidence of fragility fractures was 37.5% in women with osteopenia. And more, they emphasized the risk of fracture in osteopenia as well as osteoporosis and the need for its treatment.

Estrogen deficiency can accelerate the loss of bone mass and cause deterioration of bone quality.[14] Hence, proper treatment is needed for postmenopausal women, who are more likely to develop osteopenia or osteoporosis.[14] SERMs provide the beneficial effects of estrogen on skeletal tissue without negative effects on other organs.[15] In an in vitro study, raloxifene, the SERMs used in treating osteoporosis, decreased the rate of bone remodeling and attenuated osteoclast activity but maintained osteoblast activity.[16] Moreover, some studies revealed that raloxifene was proven effective in reducing vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis.[17,18]

In this study, we could find that the SERMs can significantly improve the BMD in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. Hence, we assumed that SERMs treatment is decreased the risk of fractures in patients with osteopenia. However, in Korea, access to pharmaceutical intervention to prevent osteoporosis in patients with T-score in the osteopenic range is limited because the National Health Insurance (NHI) does not provide coverage for these patients. Postmenopausal women with osteopenia, had a 1.31-fold increased risk of overall fracture compared with women with normal BMD.[7] In a recent study, it was projected that if the NHI expanded its coverage to include drug therapy for osteopenic patients at high risk of fractures, the cumulative number of fractures that would have been prevented between 2011 and 2015 would have increased 2.3 times.[19] Moreover, in a societal perspective, the estimated incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for the base cases that had T-scores between −2.0 and −2.4 and began drug therapy at the age of 55, 60, or 65 years were $16,472, $6,741, and −$13,982 per quality-adjusted life year gained, respectively.[20] Hence, the prescription of SERMs in osteopenia patients through the expansion of Korean National Health Insurance coverage would help reduce the prevalence of fractures and save socioeconomic costs.

This study has several limitations. First, this study had a small sample size, and the study results need to be generalized with caution. Second, this study did not check bone turnover markers. Bjarnason et al. [11] reported that changes in bone turnover were related to fracture risk during 3 years of raloxifene therapy. Although bone quantity, as measured by DXA, is an important factor contributing to bone strength, bone quality is another component that is potentially important for bone strength and fracture risk. If bone turnover markers had been included in this study, efficacy of SERMs could have been more accurately assessed. Third, we may have selection bias. The baseline BMD of group III was relatively lower than other groups. It can be assumed that patients with relatively lower BMD were prescribed additional vitamin D based on the examiner’s preference. Fourth, low adherence to drugs are not only limited to SERMs therapy but it is also observed in other osteoporotic medications.[21–24] Ringe et al. [25] reported the rate of patients’ compliance with raloxifene as 80%. Similarly, we found that of medication was 87%. Kripalani et al. [26] suggested behavioral or informative interventions which were aimed to increase the adherence to drugs. In that study, Interventions could increase adherence. However, it did not change significantly the related clinical outcomes. If compliance can be increased through effective strategies, the effect of medication can be further maximized. Fifth, studies are conflicting regarding effect of vitamin D on BMD. Reid et al. [27] insisted that the benefit of using vitamin D to improve BMD is questionable. However, Liu et al. [28] suggested that the SERMs with vitamin D may have some additive effect on improving BMD. However, there are a few reports that assess the effect of SERMs with vitamin D. In this study, SERMs with vitamin D tended to have a larger increase of BMD than SERMs monotherapies. Hence, additional studies need to assess the effect of SERMs with vitamin D on BMD.

CONCLUSION

Osteopenia can progress to osteoporosis if left untreated. Moreover, osteopenia itself may increase the risk of overall fractures. In thais study, we could find that the SERMs improved spine and hip BMD. In conclusion, preemptive treatment using SERMs in postmenopausal women with osteopenia could be necessary.

Footnotes

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The retrospective study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 2022-07-003).

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin JT, Lane JM. Osteoporosis: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:126–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, et al. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517–22. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Prevention and management of osteoporosis: Report of a WHO scientific group. 2003. [cited by 2015 Aug 3 ]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42841.

- 4.Lo SS. Bone health status of postmenopausal Chinese women. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21:536–41. doi: 10.12809/hkmj154527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian L, Yang R, Wei L, et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis and related lifestyle and metabolic factors of postmenopausal women and elderly men: A cross-sectional study in Gansu province, Northwestern of China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e8294. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000008294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park EJ, Joo IW, Jang MJ, et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis in the Korean population based on Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), 2008–2011. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:1049–57. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2014.55.4.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baek YH, Cho SW, Jeong HE, et al. 10-year fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteopenia and osteoporosis in South Korea. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2021;36:1178–88. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2021.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siris ES, Simon JA, Barton IP, et al. Effects of risedronate on fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:681–6. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0493-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siris ES, Miller PD, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Identification and fracture outcomes of undiagnosed low bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: results from the National Osteoporosis Risk Assessment. JAMA. 2001;286:2815–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.22.2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ettinger B, Black DM, Mitlak BH, et al. Reduction of vertebral fracture risk in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis treated with raloxifene: results from a 3-year randomized clinical trial. Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (MORE) Investigators. JAMA. 1999;282:637–45. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.7.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bjarnason NH, Sarkar S, Duong T, et al. Six and twelve month changes in bone turnover are related to reduction in vertebral fracture risk during 3 years of raloxifene treatment in postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:922–30. doi: 10.1007/s001980170020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cosman F, Lindsay R. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: clinical spectrum. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:418–34. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.3.0371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korean Society for Bone Mineral Research . Policy brief for osteoporosis management in super-aged society. Seoul, KR: Korean Society for Bone Mineral Research; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ., 3rd A unitary model for involutional osteoporosis: estrogen deficiency causes both type I and type II osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and contributes to bone loss in aging men. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:763–73. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahiner T, Aktan E, Kaleli B, et al. The effects of postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy on sympathetic skin response. Maturitas. 1998;30:85–8. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taranta A, Brama M, Teti A, et al. The selective estrogen receptor modulator raloxifene regulates osteoclast and osteoblast activity in vitro. Bone. 2002;30:368–76. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00685-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, et al. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:125–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cauley JA, Norton L, Lippman ME, et al. Continued breast cancer risk reduction in postmenopausal women treated with raloxifene: 4-year results from the MORE trial. Multiple outcomes of raloxifene evaluation. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;65:125–34. doi: 10.1023/a:1006478317173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency . Developing Korea-specific assessment criteria for osteoporosis. Seoul, KR: National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwon JW, Park HY, Kim YJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions to prevent osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women with osteopenia. J Bone Metab. 2016;23:63–77. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2016.23.2.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCombs JS, Thiebaud P, McLaughlin-Miley C, et al. Compliance with drug therapies for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Maturitas. 2004;48:271–87. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kothawala P, Badamgarav E, Ryu S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world adherence to drug therapy for osteoporosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:1493–501. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(11)61093-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durden E, Pinto L, Lopez-Gonzalez L, et al. Two-year persistence and compliance with osteoporosis therapies among postmenopausal women in a commercially insured population in the United States. Arch Osteoporos. 2017;12:22. doi: 10.1007/s11657-017-0316-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faulkner DL, Young C, Hutchins D, et al. Patient noncompliance with hormone replacement therapy: a nationwide estimate using a large prescription claims database. Menopause. 1998;5:226–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ringe JD, Christodoulakos GE, Mellström D, et al. Patient compliance with alendronate, risedronate and raloxifene for the treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2677–87. doi: 10.1185/03007x226357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:540–50. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid IR, Bolland MJ, Grey A. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone mineral density: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2014;383:146–55. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu HJ, Kim SA, Shim DJ, et al. Influence of supplementary vitamin D on bone mineral density when used in combination with selective estrogen receptor modulators. J Menopausal Med. 2019;25:94–9. doi: 10.6118/jmm.19193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]