Abstract

Qualitative research methods, primarily interviews, have become more common in the field of addiction research. Other data sources were often neglected, although sources such as social media can offer insights into the realities of people, since social media also plays a relevant role in today's living environments. This article examines the use of online forums as an underutilized data source in contrast to telephone interviews, to identify methodological opportunities and challenges. We analyzed nine discussion threads and seven interviews about ‘alcohol consumption during pregnancy’. Discursive comparison of the results was performed with a focus on sampling issues, comparability and risks for participants and researchers. Key issues were present in both data sources. People with different opinions were openly hostile in forums, while tolerance was more often expressed in interviews. The interviews showed a rather mild communication style, which could be attributed to social desirability. In the forum discussions, the participants often expressed themselves very directly. To comprehensively grasp the subject matter of the research, it is important to recognize the types of communication promoted by different data sources. These results have implications for research about female substance use. Knowledge of the issues will bestow a valuable contribution to researchers working in the field of substance use to help develop appropriate research approaches, as they engage in research into this highly stigmatized and controversial area.

Keywords: qualitative research, methods of data collection, online data, data sources, grounded theory, alcohol consumption, pregnancy, stigma

Introduction

Researching Alcohol Consumption During Pregnancy

Consumption of alcohol is common in many societies and related to various occasions, especially in the context of leisure and festivities. At the same time, alcohol consumption and drunkenness are policed and can be problematized and stigmatized. Research has shown that female intoxication and addiction are policed more harshly (Dragišić Labaš, 2016; Eldridge, 2010). This is also mirrored in higher self-stigmatization among women with alcohol dependence in comparison to men (Melchior et al., 2019; Moore et al., 2020). When it comes to women and pregnancy, public stigma is particularly intense (Corrigan et al., 2018).

In some areas, such as in some parts of South Africa where there is a high rate of alcohol dependence (19.1%) and alcohol abuse (6.0%) among women (Andersson et al., 2018), these alcohol use disorders are important causes (among others) of alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Fletcher et al., 2018; Watt et al., 2014). It should be noted, however, that many women who continue to consume alcohol during pregnancy (in regions of the world with the greatest proportion of middle and high income) show no patterns of use outside of pregnancy that can be classified as addictive or harmful (Kiefer et al., 2021; Mårdby et al., 2017; May et al., 2013; Popova et al., 2018). When pregnancy occurs, the assessment of consumption behaviour changes from both a medical and a social perspective in that consumption is judged more harshly. The medical perspective which informs the current guidelines in Germany(Koletzko et al., 2018), and many countries(Graves et al., 2020; Leppo et al., 2014; UK Department of Health, 2016) is that of recommending abstinence during pregnancy, while moderate amounts of alcohol consumed before pregnancy are classified as safe or unproblematic.

From a medical perspective, alcohol consumption during pregnancy can lead to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) (Hoyme et al., 2016; Popova et al., 2018). From this point of view, complete abstinence is recommended during pregnancy in order to minimize risks for the unborn child (Bailey & Sokol, 2008; Carson et al., 2017). However, it should be noted that FASD is only theoretically completely avoidable. This is due to the fact that the reasons for consumption during pregnancy are complex and multifaceted. In addition, many external and environmental factors play a role, so that in reality complete control over and/or improvement of these circumstances is desirable but never 100% achievable. And even well-intentioned FASD prevention measures have the potential to increase public stigma of women who have consumed alcohol during pregnancy, as well as of individuals with FASD, and their biological mothers (Corrigan et al., 2017; Key & Vaughn, 2019) and other caregivers (Roozen et al., 2020).

Germany is one of the countries with the highest per capita alcohol consumption in the world (Manthey et al., 2019). Compared to its European neighbours, Germany is above the average in terms of per capita consumption of alcohol (World Health Organization, 2019). In Germany, according to the maternity guidelines, at the beginning of a pregnancy women are supposed to be informed about the risks associated with alcohol consumption and about the recommendation for abstinence. The documentation takes place in the maternity records (Gemeinsamer Bundesauschuss, 2022). However, a qualitative study from Germany showed that gynaecologists do not, or only superficially, address the topic of alcohol consumption for various reasons such as fear of stigmatization or lack of knowledge about how to deal with consumption during pregnancy (Stiegler et al., 2016). At the same time, there are ongoing, also in part media-led debates about the evidence regarding the risks from low alcohol consumption during pregnancy (McCallum & Holland, 2018) and about how the recommendations derived from this (recommendation of abstinence, as no safe consumption amount has been scientifically proven) are communicated to women (Furtwængler & de Visser, 2013). The issues are further complicated by the alcohol industry as it frames information in support of its own interests. A study showed that alcohol industry-funded websites omit and misrepresent the evidence related to the primary risks of drinking alcohol during pregnancy (Lim et al., 2019).

Social norms and the socio-cultural understanding of motherhood have changed in recent decades, which has a further impact on the alcohol consumption behaviour of pregnant women and mothers. (Sudhinaraset et al., 2016). Social media interactions among mothers and expectant mothers are growing in popularity to share information and to cope with the burdens of pregnancy and motherhood (Harpel, 2018; Lupton, 2016; Wallwiener et al., 2016). A relatively new phenomenon is the wine-mom culture, in which the spread of shared norms and beliefs surrounding alcohol and motherhood via social media also plays a major role (Adams et al., 2022; Harding et al., 2021). The associated common themes related to alcohol use include the unattainable expectations attributed to motherhood, drinking as a form of empowerment and to help reduce the stress of daily demands (Crawford et al., 2020). Harding and colleagues found that wine consumption served to represent modern motherhood and was socially accepted as self-care. At the same time, consumption was seen as an act of active resistance against traditional role models and the expectations of motherhood (2021). In an ethnographic study, Killingsworth found that alcohol has taken on a symbolic character to balance women's desires between the independent living that they enjoyed before they became mothers and the new identity and changes that come with motherhood (2006). In another qualitative study of mothers who use substances, the women were found to have two models of motherhood: One view being an idealized view of motherhood as rewarding, satisfying which is consistent with social expectations and norms. The other is a model of the ‘deviant good mother’ which appears more in conformity with the experienced realities of this ideal. Both models influence the way these mothers perceive their substance consumption and how they see themselves in their role as a mother (Couvrette et al., 2016).

Still, historically (Bock, 1983; Schmacks, 2020; Weyrather, 2015) and currently (Giesselmann et al., 2018) in Germany a socio-cultural context exists in which strong and sometimes ambivalent maternal ideologies often go hand in hand with high normative standards. The philosopher Hilge Landweer classifies the ‘joy of sacrifice’ as a typical German construct in her historical reconstruction work on the ‘normative behavioural pattern “maternal love”’(Landweer, 1989). A German study found a significant and steady decrease in average maternal psychological well-being after a woman’s first birth (Giesselmann et al., 2018). At the same time, motherhood in Germany comes with more economic disadvantages than in other European countries. For example, the motherhood wage penalty in Germany is high (−8%) compared to other European Countries, while in France it is close to zero (Cukrowska-Torzewska & Matysiak, 2020). Another study also found greater declines in income after the first child among women as opposed to their partners in Germany compared to both the United States and the United Kingdom (Musick et al., 2020). This is in line with expectations in Germany, as the male breadwinner model persists both in terms of political orientation and in the form of a continuously high level of public acceptance. In Germany, mothers often work part-time and have major gaps in their careers as a result of childcare issues (Gash, 2009). There is evidence that German women with many years of education in particular delay motherhood in order to consolidate their careers in the hope of suffering less career costs (Romeu Gordo, 2009).

Little is known about alcohol consumption during pregnancy and how it is related to perceptions of motherhood in Germany. In very recent literature reviews which centred on alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Hammer & Rapp, 2022) and self-reported reasons for alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Popova et al., 2022), no studies from Germany were found. Apart from the study by our research group, we are also not aware of any studies (neither qualitative nor quantitative) from Germany. Our group published the empirical results (based on the content level) of our study in 2020 (Binder et al., 2020) and is the basis for the methodological results in this article. In addition, we are only aware of one attempt to carry out a qualitative interview study in 2013 and 2014 as part of a forerunner project by our department, which failed because too few participants were found (N = 5, but not all consumed alcohol in their pregnancy) or not enough interviewees could be recruited, so they switched to expert interviews with gynecologists and later to focus-groups with gynecologists (Stiegler et al., 2016). The lack of research interest so far, as well as the difficulties in recruiting could be understood as an indication – against the historical and socio-cultural background in Germany – that the topic is more taboo than in other European countries.

There is some body of research knowledge stemming from other countries. In an Australian study (Meurk et al., 2014) 10 (out of 40) participants stated that they had consumed alcohol in the last pregnancy. Some women in this study indicated that alcohol was significant for maintaining social activities or their enjoyment of the taste of wine led them to continue drinking alcohol (albeit at reduced levels) during pregnancy. Meurk et al. (2014) state that their findings, as well as other qualitative research on Australian women's drinking practices, show that ‘alcohol consumption is used in the construction and use of positive, highly feminine identities’(Killingsworth, 2006).

Aims

In our study, we focus on a deeper understanding of possible reasons for continued alcohol consumption during pregnancy. The aim of this paper is to reflect on the process of data collection while researching self-perceptions and experiences of women in Germany who consume alcohol during pregnancy. The aim of this article is to identify characteristic potentials and limitations of two different types of data sources that were used to carry out research on alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

The following sub-objectives are to be achieved:

What can we learn from our research process for future research with regard to the strengths, weaknesses and potential biases of two different data sources and the potential associated risks for research participants and researchers?

Methods

Reflexivity

Our multiple identities shaped the research process as a whole (Olukotun et al., 2021). Neither the connected positionalities, nor the research process are determined and static, but need to be reflected in all the steps involved (Malterud, 2001; Palaganas et al., 2017). Reflexivity is a process of self-consciousness considered to be crucial in qualitative research in general (Malterud, 2001), but is of particular relevance in the context of sensitive topics in order to diminish re-stigmatization of women during the research process and through publications who, for example, consume alcohol during pregnancy. To reflect positionalities, the researchers locate themselves in relation to (1) the subject, (2) the participants and (3) the research process (Savin-Baden & Howell-Major, 2013). We aspire to represent these relations as follows: (1) in the following, (2) in section Potential risks for participants and researchers and (3) throughout the whole paper.

As researchers, we are situated in the fields of addiction and substance use research, and health services research, in Germany in which quantitative research methods are widespread. Among the qualitative research methods, qualitative interviews play a predominant role, also in our own research. As researchers, we also have a desire and need for ‘good’ data – rich in the dimensions of interest, easy accessibility, with no harm and minimal constraint to the participants. The health care professionals among us work with patients who have a medical indication of substance use or addiction. As such, we have first-hand experience of the medical and social consequences of substance use and addiction. We have a strong interest in improving patient care and preventing ‘theoretically’ preventable disabilities for which alcohol consumption during pregnancy is seen as one important risk factor (Harris et al., 2017) – even though it is obvious that alcohol consumption during pregnancy has complex causes and origins, the resulting disabilities from the FASD spectrum can never be completely avoided. All members of the research team are aware of this; however, along with the ambitious theoretical considerations involved in developing preventive measures, we sometimes run the risk of neglecting this aspect and then (possibly) slipping into a stigmatizing attitude. In this context, we also work with categorizations such as ‘(un)problematic consumption pattern’, ‘addiction’ or ‘risk groups’. Furthermore, the term ‘substance abuse’ (instead of ‘substance use’ or ‘consumption’) is very common in our field. The women with and without children among us embody various types and concepts of motherhood. All team members have their individual consumer behaviour with regards to alcohol. The feminists amongst us focus on female agency, but also understand consumption patterns, risk groups and motherhood as social constructs and processes.

The Project as a Whole and Context of the Study Design

This comparative study arose from a qualitative part of the ‘IRIS plus’ project. IRIS is an acronym that stands for individualized, risk-adapted internet-based intervention program to reduce alcohol and tobacco consumption in pregnant women (in German: Individualisierte, risikoadaptierte internetbasierte Intervention zur Verringerung des Alkohol- und Tabakkonsums bei Schwangeren). Virtual platforms are important for pregnant women to gather information and share their experience with their peer-group (Lagan et al., 2010; Lagan et al., 2006; Wallwiener et al., 2016). The aim of the intervention program is to support pregnant women who habitually consume alcohol and/or tobacco in their daily lives. IRIS addresses all women as it considers alcohol consumption during pregnancy per se as potentially harmful, independent of the medical categorization of consumer behaviour outside of pregnancy. The intervention does not address women with alcohol addiction. The aim of the project was to revise the already existing intervention and better adapt it to the target group. To achieve this, a mixed-methods approach was carried out. The quantitative approach included an online questionnaire with the aim of a deeper understanding of the target group (pregnant women) and their needs during pregnancy. At the same time, the quantitative part of the study should serve as a ‘door opener’ for the interview study and thereby reach the largest possible pool of potential interview participants. The qualitative approach was used to explore opinions and views on the subject of ‘alcohol and tobacco consumption during pregnancy’. For this purpose, discussions from forums and telephone interviews were analyzed. Even though the project and the associated study were located at the Addiction Medicine and Addiction Research Section of the Psychiatric Clinic of the University Hospital (City), the focus here is on low to moderate amounts of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and not on alcohol dependency in pregnant women. In the analyses presented here, however, we only focused on researching alcohol consumption during pregnancy and on methodological questions. The results of the analysis of the forum discussions have been published elsewhere (Binder et al., 2020).

Study Design

Initially, we designed this study to be based on interviews, but switched to a triangulation of qualitative data in order to enrich the data and to understand ostensible frictions in data (Denzin, 1970; Flick, 2004; Morse, 2015; Morse et al., 2016). We were aware from our work as health care professionals and through previous research in the IRIS project (in which a face-to-face interview study was canceled due to recruitment difficulties in a previous phase of the project) that re-stigmatization of women can occur through the research process itself. In light of this background, we screened discussions in online forums for pregnant women to first gain insights and ideas for developing a sensitive and informed interview guideline for telephone interviews. However, the online discussions turned out to be so rich in perspectives rarely addressed in studies in our field, that we decided to include them as a data source of their own. This was not planned from the beginning, but resulted in a highly informative data source and a new approach in our field, since interviews are the predominant data source in the field of qualitative substance use and addiction research in Germany (Binder & Preiser, 2021). In a second step, we conducted the interviews to focus on individual biographies and personal concepts. We approached this step with the idea of making a comparative analysis on a methodological level. Both data sets were analysed separately using Grounded Theory Methodology (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser Barney & Strauss Anselm, 1967; Strübing, 2014). Subsequently, both the process of data collection and the results were compared. Thus, the following results represent the comparison of the two data sources on a methodological level.

Participant Information and Safety, Ethical Considerations and Ethic’s Committee Vote

During the recruitment process, the potential participants received a brief written explanation of the interview study. This included the information that the interviews were focused on personal experiences on the topics of health during pregnancy, information sources about health topics during pregnancy, as well as alcohol consumption and smoking during pregnancy. Those interested in participating, received detailed written information and a consent form before the interview. In addition to the written information, at the beginning of the interview participants were again informed (verbally) about the possibility to end the interview at any time or to refrain from answering questions, and also about data protection, including pseudonymization.

At the end of the interview, participants were asked whether they needed to talk about the potentially stressful topics discussed outside of the research interview (either with the interviewer or via referral to a therapist in the department). The information and consent form that participants received before the interview did not contain any references to counseling centres that could be contacted in the event of stress.

The online forums whose content we used is freely accessible on the Internet (without registration, etc.). While the contributors did not expressly consent to use of their statements for research purposes, due to their contribution on a public forum the authors are considered to be aware that posted content is publicly available, freely accessible and therefore in principle disposable for any purpose. We explicitly decided not to use forums requiring mandatory registration for (reading) access, since we assumed that at least some participants preferred to privately express themselves in this more protected framework. This view is also shared by authors who consider ethical aspects of using online data for research purposes (Bruckman, 2002; Harriman & Patel, 2014), according to whose considerations we oriented our approach. For reasons of data protection, the nicknames of participants were not included in the analysis and removed for displaying the results. All references to the identity of the participants have been removed or modified.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Tübingen on November 29, 2018 (project number 852 / 2018B02).

Data Analysis

The analyses of the data sets were carried out independently and according to Grounded Theory. Coding is defined here as a procedure to develop concepts and theories by processing and interpreting the empirical data (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser Barney & Strauss Anselm, 1967; Strübing, 2014). The steps of open, axial and selective coding were carried out in an iterative process, with interim results being regularly discussed in the research team (consisting of 4 psychologists and 2 physicians) in order to ensure the intersubjectivity and thus the quality of the interpretation. Here, agreements between and deviations from our own ideas of the role of mother and of consumption and abstinence during pregnancy were identified, with the goal of integrating our knowledge as researchers and/or medical experts and those as mothers and/or feminists. The resulting tensions were examined more closely. Personal experiences in the context of pregnancy and motherhood also flowed into the discussions and reflections during the analysis. We tried to benevolently question and understand the reasons and motives for consumption during pregnancy, also from a therapeutic point of view, as most members of our research team also have a psychotherapeutic background.

During the open coding phase, a small-scale interpretation of selected data sections was carried out by the research team in order to identify first phenomena and categories. Individual passages were interpreted word by word and the meaning of the linguistically fixed phenomena was discussed. As part of the axial coding, we identified connections between the categories step by step and enriched them by continuous comparison. We derived more global core phenomena from the initial codes during this process. This step was carried out by (author 1. To ensure quality of analysis, selected text passages were discussed at weekly meetings in the research team and coded together. In addition, selected parts of the data material were discussed with other researchers (outside the research team) at various points during the analysis process in the ‘Qualitative Methods Research Workshop’ of the Centre of Public Health and Health Services Research at the University Hospital Tübingen, under the direction of author 2). The results of these discussions were then integrated into the further analysis process.

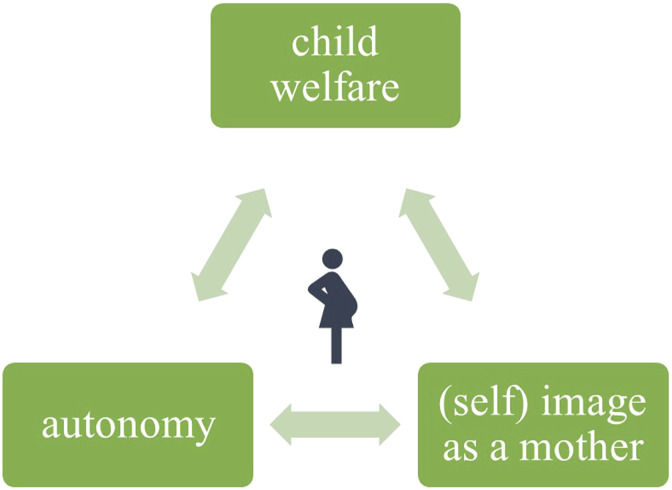

During the steps of open and axial coding, the mother role or the ‘mother image’ emerged as the central concept for the theory formation. In this case, the ‘mother image’ is comprised of a normatively expected (self-) image and a definition of motherhood in relation to the social role . The tension between autonomy, child welfare and the (self) image as a mother (Illustrated in Figure 1) and the roles of these different aspects were worked out in the process of analysis as central elements.

Figure 1:

Core Concept of the GT Analysis showing the tension between different aspects of the dimensions of motherhood found in the analysis. The analysis showed that the attitude towards alcohol consumption during pregnancy was clearly shaped by self-perception as a (expectant) mother and by the personal idea of the mother's role. The redefinition of one's own role seems to be a dynamic process, especially for women in their first pregnancy. It became clear that pregnant women, in the process of redefining their own role, found themselves in a triangle of tension between the well-being of the child, individual self-image and the needs that arose from the new role as mother-to-be. Depending on which aspect dominated in the pregnant woman, different reasons were identified which led to single or multiple occurrences of alcohol consumption (Binder et al., 2020).

In the step of selective coding (carried out by author.1), material with a focus on this central concept was partially (re-) coded, whereby an integration of previously developed topic complexes and a validation of the relationships found was achieved. The recoding was discussed at weekly meetings in the research team to ensure intersubjectivity. The comparison at the methodological level, upon which this article is based, was made discursively in the research team (consisting of all authors except author 2) and in the ‘qualitative methods’ research workshop (under the direction of author 2). The focus for the comparison of the data sources was devised in the research team after its members had analyzed the content of the data. We recognized the focal points, and decided that these aspects should be compared in thorough and explicit manner. For this purpose, author 1 created analytical memos – that is, short notes about the thoughts, ideas and questions that came to the researcher's mind as she compared the two processes of data collection and analysis. These were enriched by the respective material which was generated during the process (memos from the recruiting phase, quotes from the participants, etc.) and presented for discussion in the formats mentioned above. The results of the discussions were documented. New aspects then determined the focus of the next comparison and analysis steps. In addition, in all phases of the comparison process, results were compared with findings from the method literature.

Translation

The data were analysed in German, and the citations listed in the results section were subsequently translated from German into English by the research team. In a second step, a backward-forward translation was performed by a professional translator who is a native speaker. The translated texts were then adjusted accordingly.

Important to mention is that in both the contributions from the forum discussions and from the interviews, there were many original passages that were not expressed correctly in German in regard to the grammar or wording. Therefore, it must be noted that translation is not a purely technical process, but also a form of analysis. This means that translation necessarily aims at revealing the conscious or unconscious features of what is said or written, used by the researchers and understood by the translator as the content to be conveyed. In this sense, the translations in this study – at least for some passages – can be considered free translations, which means they included some degree of interpretation.

Results

The two methods of data collection were compared on several levels. The focus was on the following points:

• Sampling issues and recruitment

• Comparability of the results regarding themes and wording

• Potential influencing factors and bias

• Potential risks for participants and researchers

We selected illustrative citations to provide insight into the material. For reasons of data protection, the nicknames were removed for the presentation of the results. We removed or modified any indications of the identity. The discussion threads and interviews were each numbered consecutively. The letter stands for interview (I) or discussion (D). The first number stands for the numbering (e.g. I2_32). In addition, the discussions and interviews were divided into individual sections of text, which were also numbered consecutively. The second number represents the number of the text section within a text (e.g. D3_7).

Sampling Issues and Recruitment

Data collection and the sample are presented here in a common section, since the processes involved in data collection and, respectively, recruitment had a major impact on the actual sample and it therefore did not seem sensible to present them separately. Since the comparison of the processes is a main result, we have presented the recruitment and sampling process of the two sources here (instead of in the methods section) and directly attached the presentation of the comparative analysis.

Discussions From Online Forums

Online forums also attract readers who ‘lurk’ and do not actively engage in content creation (Fullwood et al., 2019). Initially, we were ‘lurking’ in German-speaking online forums for pregnant women in order to design an appropriate interview guide. In these forums, discussion threads were created and used by participants independent of our research project. The online forums were openly accessible. We were among the silent readers of public content and did not write any contributions to the discussion. We found material highly relevant to our research interest and decided to extend the study design. The discussion threads that we eventually included in the data corpus were selected on the basis of theoretical sampling according to Glaser and Strauss, for which the interaction between data generation and evaluation is of central importance (Glaser et al., 1968). Accordingly, a first online research phase was initially carried out in order to gain an overview. The first selected threads (from a highly frequented German mothers' forums) were presented in a workshop for qualitative research methods. There, the threads were analyzed by the group sentence by sentence, and at times word by word. In this process, the first concepts for the prevailing mother images were developed, and at the same time the researchers freely associated what might be missing in the (self-) representations in these threads. For example, it was noticed that own needs of women and pleasure were rejected or not discussed in these threads. It was assumed that an opposite attitude might be found on feminist forums. Therefore, in the next step (by author 1), a search for forums with a feminist background was pursued and a deeper search for threads on those forums concerning the subject of alcohol consumption during pregnancy was carried out. As a result, such discussions were also found in two feminist online forums. Based on this process, particularly relevant threads from different forums were selected discursively that contained many important aspects (e.g. top mom performance, a feminist view on pregnancy or the attribution of the expert role on medical staff) and controversial opinions of various discussion participants. In parallel to the analysis process of those first threads and the identification of the first relevant topic complexes, further threads were selected, which depicted the topics but rather as expanded or contrary views. The selection aimed to present the broadest possible range of opinions. Additional threads were added to the data corpus during the entire analysis process until no new coding or relevant new aspects for the existing coding resulted from the other threads viewed, for instance, until a theoretical saturation occurred (Charmaz, 2006; Conlon et al., 2020; Strauss, 1998; Strübing, 2014).

A total of 14 threads were viewed, nine of which were included in the data corpus. Threads in which similar topics were discussed, such as in threads that had already been included in the study, were excluded. The nine discussion threads stemmed from five different forums and blogs on the subject of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and comprised a total of 115 discussion participants. The individual contributions to the discussion varied in length from 4 to 636 words. There was no access to socio-demographic data such as age, number of children or educational level of the discussion participants.

Telephone Interviews

As part of an online survey (on the subject of perspectives on health in pregnancy) conducted for the IRIS plus project, the participants were asked whether they were available for a telephone interview (which also covers the issues of alcohol consumption and smoking during pregnancy). Telephone interviews were chosen for recruitment reasons, in order to reach people from all over Germany and thereby be able to have the largest possible pool of potential interview candidates. The use of telephones in Germany continues to be more common than other forms of virtual communication such as video conferencing services, so we chose telephone interviews as an easily accessible method of communication. In addition, we presumed that telephone interviews would increase the sense of anonymity and thereby have a positive effect on the discussion of sensitive topics. In contrast to other forms of interviews (face-to-face or digital) in which a participant is visible to their counterpart, via telephone the risk of losing face in front of researchers would minimized (Niederberger & Ruddat, 2012). As an incentive for participating in an interview, 50 euros were offered. A total of 1784 persons started the survey, but only 234 completed it. 182 of the women were included because they stated in the self-disclosure that they were pregnant. In total, 96 out of the included participants agreed to participate in an interview, which results in a share of 52.7%. In total, only 15 people indicated having consumed alcohol during pregnancy. Almost half of them (n = 7) were ready for the interview and had provided an email address to be contacted by the research team. However, it turned out that it was especially difficult to eventually conduct the interview. In some cases, the interview appointments were canceled at short notice, or the participants could not be reached by phone at the agreed time. We therefore assume that after initially agreeing (perhaps spontaneously) to an interview, the persons had consciously or unconsciously dealt with the underlying topic in the second step. In doing so, they may have become aware on a rational level that they indeed did not want to talk about this topic. We can also imagine that some women may have felt increasingly uncomfortable in the time preceding the interview during which they were completely unaware of the process – and yet they may have declined the interview in order to avoid consciously raising the issue.

Thus, only four interviews, primarily with women who had consumed only during early pregnancy, came about in this way. It should be noted here that the prior knowledge from the forum analysis, namely, that there must also be women who actively, consciously and out of personal conviction decided to consume, meant that the recruitment process was not terminated here, but that an active search was conducted for women who met these criteria. Since recruiting via the online survey proved insufficient, additional recruiting channels were chosen. Women who had consumed alcohol were specifically invited through postings in several Facebook groups. The search was explicitly for consumption after early pregnancy. In this way we reached two more women. One of them came up with a one-time consumption of alcohol in pregnancy for reasons of enjoyment/pleasure, the other several times during the course of pregnancy, for the same motivation. In addition, a chance contact was made through a person from the research workshop who enabled private contact with a woman who had made a conscious decision to consume alcohol during pregnancy. This one woman also agreed to take part in an interview.

Since the interviews were part of a larger study, the topics of healthy living during pregnancy (exercise and nutrition), as well as smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy were addressed. The interview guide was developed by the research team. It contained introductory questions, follow-up questions and further inquiries. Overall, the guide aimed to generate and maintain free narratives relating to personal experiences and attitudes about defined, specific subject areas. Characteristic for the interviews is that the focus is on the individual with his or her experiences and personal views.

Because alcohol consumption during pregnancy is a sensitive topic, the guide was structured in such a way that less sensitive topics were placed at the beginning of the interview. The intention was to create a trusting atmosphere for the participants before the sensitive topic would be addressed. Likewise, with the questions about alcohol consumption, general questions were initially asked before the questions were approximated to the interviewees’ own consumption experiences. See Table 1 for example questions from the interview guide.

Table 1:

Example Questions From the Alcohol/Tabaco Part of the Interview Guideline

| Topic | Key questions | Maintenance questions (optional) | Specifying questions (optional) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General opinion on alcohol / tobacco consumption during pregnancy | • What do you think in general about the consumption of alcohol or tobacco during pregnancy? • Do you know people who see things differently and what is their opinion? |

Feel free to tell us anything that comes to your mind on this topic. | • What do you think are the reasons for not drinking or smoking during pregnancy? • In your opinion, are there also possible reasons for drinking or smoking during pregnancy? Can you imagine what could lead to this? |

| Personal experiences with consumption / abstinence during pregnancy | • How did you feel about this topic during your own pregnancy (pregnancies)? • Were there any particular challenges or difficulties? |

Can you tell me a little more about that? In particular, please tell me about your own experiences and perhaps episodes from your pregnancy on the subject. |

• If the women stated consumption: Were there specific situations, occasions or reasons for you to smoke/drink? • If the women stated no consumption: Do you remember situations or phases in which you found it particularly difficult to maintain your decision to abstain? |

| Use of support services and experience with healthcare professionals | • Have you ever looked for information, help or support on the subject? • Have you received any information or offers of support? |

Do you remember when that was the case? Was it in certain phases of pregnancy or for a specific reason? |

• If yes: How did you find the information/help/support you received? Did that help you? Or would you have needed something else? • If not: Why not? What would have made you seek information/help/support? Would you have liked to have been offered information/help/support? |

A total of 7 women were interviewed. They were between 27 and 38 years old. Five participants were pregnant at the time of the interview. The others had given birth within the last year. Two of the pregnant women were expecting their first child. Five women had one or two children. All participants had completed vocational training, of which three of the participants had a university degree. Five participants had only consumed alcohol in early pregnancy (first trimester), most of them before they knew they were pregnant or before receiving a positive test while trying to get pregnant. Only two women actively chose to consume alcohol throughout pregnancy. The telephone interviews were recorded and then transcribed into written text.

Comparison of the Sample

The discussion forums were easily accessible as only public forums were used that did not require registration to read the posts. By including threads from various forums, different perspectives on the topic could be included in the analysis. All contributors to the threads authored input using nicknames. Assumptions about the participants could only be generated through the linguistic explanations of the contributions to the discussion and content-related information. In the general forums, the posts more often contained spelling and grammatical errors. This is not necessarily related to demographics such as educational and socioeconomic background. Nevertheless, it meant that the contributors created a space in which linguistic skills were not important. In the feminist-influenced forums, the texts were more linguistically sophisticated. In addition, they contained references to English studies, suggesting at least advanced language skills. Furthermore, the content of the threads indicates that most contributors identified as women either in their first pregnancy or with (a) young child(ren). Thus, we assume that the sample of this study part consists of women in their early twenties to mid-forties, from various educational and economic backgrounds who had the means and ability to eloquently express themselves in written German language. In conclusion, the data were easily accessible and rich in themes, but the background information about the actual contributors were sparse.

Recruiting interviewees proved to be difficult. Only a few participants from the online questionnaire agreed to be interviewed by phone. Primarily we were able to reach the group of women who had consumed alcohol in an early stage of pregnancy before the positive pregnancy test, even if the pregnancy was planned. We knew from the forum analysis that there must be women that actively and consciously decided to consume during pregnancy (i.e. not due to an addiction or a lack of knowledge of the risks). We were able to find three women who did so and were willing to tell their stories. One of them was a chance contact through a person from the research workshop. Other researchers have shown that researchers’ multiple identities and positionalities have a major influence on the sample, sampling and quality of dialogue (Manohar et al., 2017). In our study, too, the potential participants in the study and most researchers in our team showed similarities when it came to the most relevant dimensions: cisgender heterosexual white women in their late twenties to late thirties with a middle to high educational status.

Themes Addressed

In both the forums and the interviews, the women indicated that they consumed small amounts and had occasional drinks. Many key issues were present in both data sources. In both data sources, it occurred that the self-image as a mother and the individual understanding of the mother role contributed significantly to the opinion held on alcohol consumption during pregnancy. The framework for redefining one's own role was found in a triangle of tension between the child's well-being, the individual self-image, and the needs arising from the new role as the mother-to-be (see Figure 1). Different reasons for consumption of alcohol were identified depending on which aspect dominated the self-image of the pregnant woman as a mother (for a more detailed analysis see (Binder et al., 2020). There were major differences between the different mother images that were drawn. These existed within each data source. In contrast, there were no major differences between the data sources in the different mother images that were found. The portrayal of a perfect, disciplined mother is one of these images, as these quotes show:

“So, I haven't drunken alcohol since I wanted to have children!” (31_D4)

“And then it [pregnancy test] was actually positive and from that day on it put an end to alcohol.” (100_I4)

“I also believe that this is not an option at all. The child is defenseless and, in fact, a responsible mother should be so concerned about the health of her baby that she without question renounces anything that could be harmful.” (81_D7)

“And I just think that a responsible pregnant woman should definitely avoid it [alcohol]. And for me, this also includes a little champagne. Well, I just think that you really should, if you know: I'm pregnant - you shouldn't do that under any circumstances. And I would also find it grossly negligent for someone who was once pregnant to say to the other person: Ah yes, a glass of sparkling wine didn't harm mine [my child] either.” (27_I11)

Another image centred around the autonomy of mothers as women. Here, constant external control and suppression through health care professionals and society were addressed:

“The rights and needs of pregnant women, on the other hand, hardly count anymore; rather, as a potential danger to that 'life to be', they are subject to increased scrutiny and discipline.” (6_D8)

“Mothers and especially pregnant women have to follow strict rules” (7_D2)

„So I dealt with it relatively intensively beforehand, because there are quite a lot of rules and regulations about what you are allowed to ingest during the pregnancy and also what you rather shouldn't. And in the end, I actually adopted relatively little of that for myself.” (32_I12)

“And it's not just the medical profession, it's also our environment that's keeping an eye on us.” (17_D9)

“So I can tell that people are confused or have sometimes asked something like: Hey, you're pregnant. How does that work actually? Well, not only with alcohol, but also somehow with meat or cheese. Like with such things that are typically associated with abstinence during pregnancy.” (76_I12)

These images were found in both data sources. However, it should be noted that some aspects such as alcohol consumption for pleasure motives could only be presented in the interviews with prior knowledge and increased recruitment effort. It became clear that the results differed only slightly in terms of content, but in some cases strongly differed in terms of wording.

Wording

Attitudes towards women who think or act differently were expressed much more frequently in the forums. As in other studies, more drastic formulations were chosen (Rier, 2007). Terms such as ‘never’, ‘at any time’, ‘no one’, ‘everyone’, ‘absolute no go!’ or ‘under any circumstances’ were used frequently across all nine threads when it came to alcohol consumption and pregnancy and early motherhood. The following quote illustrates this:

In any case, very important for everyone who says: Oh, you can have a drink! … NOT an option AT ALL! (18-19_D6)

Less openly judgemental statements were made about the same content in the interviews, for example, when absolute terms were embedded in statements of tolerance. Tolerance was rarely expressed in the forums, sometimes only when talking about very small amounts of alcohol, for example, alcohol in sauces or sweets. Moralizing appeals were given primarily in the forums. The women who were interviewed emphasized openness and tolerance more often. There were statements about the lack of addressing the topic or lack of clarification by medical professionals. Negative experiences in the personal environment or with medical specialists (primarily gynaecologists and midwifes) were described in the interviews, but usually then relativized or excused. In the online forums, however, negative experiences with healthcare professionals were expressed very openly. Illustrative passages from the forums and interviews are shown in Table 2.

Table 2:

Selected Text Passages From the Forums and Interviews That Show Devaluation, Tolerance and Relativizing statements.

| Themes | Text passages from the online forums | Text passages from interviews |

|---|---|---|

| Examples of devaluation and condemnation |

I am also of the opinion that this is not at all possible. The child is defenseless, and actually a responsible mother should be so concerned about the health of her baby that, without question, she renounces everything that could be harmful. If you are not able to do without such things [as alcohol], you are actually not able to take care of a child, because if you can't get by without alcohol for 9 months, you certainly won't be able to be a responsible mother for 18 years… (81-82_D7) If I am not even able to let it [consuming alcohol] go when I want to have children, I feel that there is a certain dependency. (77_D4) Not possible at all. Not a little and not every now and then. I find that absolutely irresponsible and if you can't stop using drugs [the discussion is about alcohol], you shouldn't have children either, quite simply. Either/or is the motto. :-) (73_D7) |

And I'm also of the opinion, without wanting to condemn women who do that, well because they may also be dependent… Dependence is after all an addiction, and it's easy for someone like me to say: Just stop it. I know that, but nevertheless I am of the opinion that you should not under any circumstances - that is, alcohol - under no circumstances do that. (27_I11) |

| Examples of tolerance |

I don't judge anyone who thinks otherwise. (131_D3) [Topic: Alcohol in food, for example, in sauce or fruit] I think it's great when you try to expose your child to as few harmful substances as possible, but I don't want to drive myself crazy and I'm of the opinion that you can't control everything anyway. I think everyone has to decide for themselves how far they want to take it. (112-113_D3) |

So, I don't want to advise anyone in any way [on the subject of alcohol consumption during pregnancy]. I think this is such a very individual decision. (62_I12) |

| Experiences with healthcare professionals | During our visits to the doctor, we are measured but not properly informed. Instead of explaining how high which risks are with which consumption, complete bans are imposed upon us that deprive us of any freedom of choice and give us the feeling that the fetus in our womb is in perpetual mortal danger. (F9_13) |

Interviewer:

‘So the topic of nutrition, sport, alcohol wasn't at all … a more important topic [during the check-ups by the midwife]?’ Respondent: ‘Maybe it just wasn't that important to me at the time, and I just didn't ask about it. As far as I remember, the midwife didn't say anything of her own accord’. (57-58_I12) |

Potential Risks for Participants and Researchers

In addition to opportunities, qualitative research approaches also carry risks. This is true for both researchers (Bloor et al., 2010; Clark & Sousa, 2018) and participants (Cecchini, 2019; Mallon & Elliott, 2019). Some topics led to emotional engagement of the research team and were experienced to varying degrees as stressful. We recorded this in occasional memos. The following points stood out: With both data sources, individual persons involved in the research process experienced it as a burden to learn about consumption during pregnancy, the potential harm (to the baby) and the attitude towards it. When analysing the forums, it turned out to be stressful to find out about consumption or to experience extreme communication situations among the discussion participants without being able to intervene. What generally stood out in the interviews was the difficulty in dealing with differing attitudes. In particular, women on the research team, who had children or were planning to have children, appeared to be emotionally involved.

It should be noted here that the analysis was also carried out by people who, in addition to their role as researchers, are also active in psychotherapy. In this other role, they are accustomed to actively using therapeutic, supportive measures in their work. During the interviews, but also during the analysis of the forum discussions, they had to adopt a passive, observer role. As health professionals, most of us also have an attitude based on promoting health and preventing harm (toward both mothers and children). Ambivalence and stress could arise from the fact that this competes with other personal values such as self-determination and feminist perspectives on motherhood. While the researchers could draw from their experiences as trained interviewers and therapists in the interviews to stay professional, we designed the data analysis sessions as a safe space where these thoughts could be shared and discussed as part of the process.

Within the scope of the analysis of the already existing discussions on online forums, initially no direct risks for the discussion participants emerged through the research itself. This was because the material was created completely independently and thereby not coupled with the research process. The decision of the contributors to address the subject of ‘alcohol consumption during pregnancy’ arose out of an intrinsic motivation. Participants used pseudonyms. Real names, email addresses or other personal data could not be accessed. Against this background, we considered the data we eventually used as pseudonymized and quotable without adding risks to the discussion participants.

When conducting interviews, the participants were confronted with the subject due to the research process. Since the questionnaire study covered many topics, conceivably the participants did not know at the beginning that they would also be confronted with sensitive and/or constraining topics or to what degree the topics would be experienced as personally sensitive. There were indications that addressing the issues was difficult for some potential participants. This was expressed in the ambivalence regarding participation in the interviews during the recruitment process. Some participants even made appointments for interviews, but eventually canceled them or were not available at the agreed upon time. A potential participant later apologized by email for missing the appointment and canceling her participation, and additionally she stated that she was uncomfortable talking about the topic. The ambivalence might have been increased by the incentive (50 euros) for participating in the interview. The extrinsic motivation to deal with the issue may have been strengthened, while other inner parts of the person avoided addressing it. Social desirability seemed to play a certain role in the responses given during the telephone interviews. This was well illustrated by an answer from one participant:

Interviewer: “What do you think about the consumption of alcohol and / or tobacco during pregnancy, in general?”

Respondent: “In the end, both are technically a no-go. So, neither smoking nor alcohol should be consumed during pregnancy. I totally agree with you (laughs).” (83-84_I4)

Here the interviewer asked a question without expressing their own attitude toward this topic, neither during the interview, nor in the conversation beforehand. Nevertheless, the interviewee’s answer refers to a presumptive shared attitude. Here it becomes clear that the research participant made assumptions about the interviewer, both as an employee of the Addiction Research and Addiction Medicine Section and as a mother as well, which shape her reply and therefore also impact the data.

Discussion

Strengths and Challenges of Both Data Collection Methods

Most qualitative approaches in addiction and substance use research and health services research use interviews or focus-groups, especially in the German research context (Ullrich et al., 2022) This is also reflected in the two reviews that included qualitative studies using telephone interviews, face-to-face interviews or focus-groups (Hammer & Rapp, 2022; Popova et al., 2022). Only three studies by Toutain (2010, 2013,2017) from France used internet forums or chat groups as a data source. Some authors emphasize that more attention should be paid to other data like observational or visual data, as well as to written documents (Rhodes & Coomber, 2010). The latter frequently exist outside a research context in a broad range of forms such as letters, e-mails, diaries, blogs and online forum discussions.

In our study, we included both discussion threads from online forums and qualitative interviews. The online discussion forums already existed and were not connected to our research, whereas the qualitative interviews were conducted solely for the purpose of the research. Similar themes were generated in both data sets. This is partly the result of substantial effort in the recruitment process for the interviews, and from the knowledge gained from the analysis of the forums used as an additional basis for the recruitment. Discussion threads in online forums might be particularly useful in exploratory studies where little prior knowledge about the field of research is available, such as the reasons for continued alcohol consumption during pregnancy among women living in Germany. In other studies it could be determined that compared to interview studies on the same topic, analysis of pregnancy forums alone could produce other main topics as a result (Wexler et al., 2020). Interestingly enough, these investigations were not about sensitive subjects, but about general topics regarding pregnancy and the use of the Internet for pregnancy topics.

It became clear that the sampling for the interviews was much more time-consuming and that more prior knowledge was required to include multiple perspectives and experiences. The forums encouraged to persist on finding those perspectives. Furthermore, the interviews were more cost-intensive than the online data, as more effort was needed to generate interviews: They were more time-consuming for the researchers, required incentives for the interview partners, and incurred transcription costs. However, interviews allowed to gain in-depth and research-tailored accounts of individuals’ experiences and concepts which was not possible from the forums.

Moreover, with interviews contextual information is available for the interview participants, for example, socio-demographic data. In the discussion threads, background information about the contributors could only be assumed via the contents of their entries or through their use of language. There is a risk of selection bias in the recruitment process for qualitative interviews (Collier & Mahoney, 1996; Creswell & Miller, 2000; Heun et al., 1997; Maxwell, 2008), especially when it comes to sensitive topics. This would have been even more true for our interview study without prior knowledge and without the great effort to find pregnant women who had consciously consumed alcohol for reasons of pleasure. In general, this could result from the fact that people who know that the reality of their lives, (i.e. also their answers) does not correspond to the socially desirable norms, are not readily willing to participate in interviews. Or as in our study, there were participants that were initially willing but then declined. This may be because they consciously or unconsciously chose not to confront the stigmatized issue or did not want to be identifiable as someone who does not conform to the known socially desirable norms. Consequently, their worlds of experience and views are not available for consideration.

Communication on the Internet, for example, offers special opportunities through anonymity and other factors. On one hand, the possibility for embellished self-portrayal can be increased (Schlosser, 2020). This was mainly investigated in connection with the #fitspiration trend, which includes photographs or other material on social media platforms intended to provide motivation to exercise and be physically fit (Goldstraw & Keegan, 2016; Prichard et al., 2020). On the other hand, anonymous forms of communication can help participants to show their true selves (Bargh et al., 2002), for instance, to enable self-disclosure (Schlosser, 2020). It is often not possible to determine which aspect predominates in a discussion in an online forum, so it can be assumed that both phenomena are present generally and also in our data.

Online forum interactions can be a valuable source of advice and support, while allowing people to remain anonymous. Belonging to a virtual group like in an online forum enables the members to develop a feeling of identity and closeness to their virtual peer-group. At the same time, anonymous online forums are used for the social validation of health-related information and behaviour (Jessen & Jørgensen, 2012; Jucks & Thon, 2017). Self-portrayal also plays a role in the credibility of a statement. This can be seen in our data set by the absolute and drastic wording used by contributors. At the same time, a stable need for social recognition is a possible cause for self-presentation (Krumpal, 2013) – in any kind of social interaction.

Stiegler et al. (2016) reveal the shared silence between patients and physicians (in Germany) when it comes to addressing alcohol consumption during pregnancy. This can also be found in our data, even though the representation of negative experiences is more prominent. Some authors proclaim there could be an overrepresentation of negative experiences in online forums (Smedley & Coulson, 2021), which might be the case in our data with regard to negative experiences with medical staff but also with the harsh responses among contributors. Other authors argue that forums allow more openness to report negative experiences (Schlosser, 2020). Greater openness became apparent, for example, when online groups (as opposed to face-to-face groups) showed a greater spectrum and a greater variety of opinions or attitudes about a give topic (Schlosser, 2009). A wide range of possible reasons for continuing alcohol consumption during pregnancy was also shown in the online forums in our study (own article, names deleted)(2020).

In online discussions, the social awareness within a particular online community also influences discussion and response behaviour – depending on the context and participants (e.g. on feminist online platforms). It can be assumed that social desirability in general online forums plays a different, perhaps less important, role than in 1:1 interviews, since the range of expected attitudes on a topic is much larger. In interviews, social desirability might play a bigger role than in online forums. Some people hold back elements or bigger parts of their stories to avoid negative feelings of shame, embarrassment and loss of face in social interactions – this is especially the case with scary or sensitive topics (Schaeffer, 2000). Although studies show that there are no significant differences in content between face-to-face and telephone interviews (Sturges & Hanrahan, 2004), in telephone interviews researchers seem to tend to speak more and possibly be more dominant (Irvine, 2011), which could also have an impact on the response behaviour. In telephone interviews, participants were more likely to respond in a socially desirable manner than in face-to-face interviews (Holbrook et al., 2003). Telephone interviews were used in our study and there was clear evidence of socially desirable responses, which could have been reinforced by the incentive (50 Euros) and the resulting pressure to deliver a ‘good interview’. This might also be due to the fact that it is more difficult to build trust via telephone as non-verbal means of communication are missing.

It is suggested that data collectors should be trained to recognize and avoid their own prejudices and heuristics towards others that may reinforce social desirability (Bergen & Labonté, 2020). This is certainly an important strategy, but our study showed that the association of the study to the Addiction Research and Addiction Medicine Section, as well as age and gender of the interviewer, might also have had an influence on the socially desirable response tendencies. Therefore, we share the view of Bergen and Labonté (2020) that social desirability bias should not only be cited as a limitation, but should be accepted as a reality in qualitative research.

Potential Risks for Participants and Researchers

Qualitative research approaches investigate social phenomena; therefore, the research process is often accompanied by social interactions between researchers and participants, especially when interviews are used as a data source. An important ethical consideration when dealing with sensitive topics is whether it is at all appropriate to invite people for interviews and talk to them about sensitive topics? Can they be left alone afterwards to deal with the potentially stressful issues? For some, just the specific invitation to participate in an interview about a sensitive topic could itself create stress that cannot be mitigated by the research team. Particularly in the case of sensitive topics, participation or even just being invited to an interview may lead to unwanted preoccupation with this topic. This became clear in the recruitment process for the interviews. Many authors who have dealt with the possibility of reducing potential risks for study participants recommend that researchers use their intuition and break off the interview if the participant becomes too stressed (Allmark et al., 2009). However, this possibility does not apply if the burdens for potential participants arise in the recruitment process and contact cannot be maintained. It would therefore be advisable (which we did not do in our study without the relevant prior knowledge) to integrate references to psychological support centres or the like in the first step of the recruitment process to offer people a support option if mere confrontation with the topic leads to stress. This is because it is reasonable to assume that there may be psychologically destabilizing or stigmatizing experiences that researchers may not be able to accompany adequately, if at all. The socially desirable answers mentioned above, on the other hand, can also be interpreted as a resource of the participants to protect themselves.

In our study, we were silent readers in the online forums and did not add anything to the discussions. Writing and reading can result in burdens and risks for the contributors. However, in the context of this study design, they would have arisen even without the research concern. The analysis of freely accessible internet data does not require a separate declaration of consent, as it can be assumed that the post creator is aware that posted content is publicly available and freely accessible and could therefore be used for any purpose (Harriman & Patel, 2014; Samuel & Buchanan, 2020). Even if real names are often not used in forums, care must be taken when publishing information that could allow conclusions to be drawn about a person. Due to the structure of the data, we used from the forums (no real names, no accessible email addresses, no information that could identify individuals), we did not consider publication as risky. Nevertheless, the use of online data is continuously debated and perspectives and requirements can change, even within the time between designing and publishing the study.

Finally, the emotional burdens and risks for researchers when dealing with sensitive topics should also be considered. Due to the close engagement with the individuals involved in the research process and the resulting social interaction (e. g. during interviews), there are particular risks for researchers who investigate sensitive topics with qualitative methods (Dickson-Swift et al., 2007; Dickson-Swift et al., 2008; Mallon & Elliott, 2019). In our study, stress occurred both in direct interaction (interviews) and in the analysis of completed interactions from the online forums. It was mostly connected to our identities as health care professionals in the field of substance use and addiction, our own concepts of motherhood and our own perceptions of alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Here, the particular burden could arise less from what is heard/read itself, but much more from the passive role of the researchers, who are otherwise used to helping those affected in their role as therapists and (helping) to make them feel better. The role as a researcher limits the interviewer’s role as a therapist, so that a certain helplessness is experienced thereby causing stress. This observation suggests that qualitative research gets particularly close to the individuals involved in the research process. Qualitative research might lack the emotional distance that quantitative research approaches can create by abstracting data into numerical values. Self-care and exchange among colleagues in the team could be particularly important for the researcher. While the burdens of researchers focused on the topic of ‘alcohol consumption during pregnancy’ may be significantly lower than in other areas where violence or trauma are involved, the potential stress load should not be ignored completely.

Strengths and Limitations

The density of information in the material was characterized by the fact that the topics named were hardly found in existing literature and previous work of the working group, such as a feminist view on alcohol consumption during pregnancy, which included, for example, the rejection of the ‘alcohol ban’ during pregnancy, which was considered paternalistic, out of their own feminist convictions or for pleasure as a motive for consumption. In addition, there was a particular openness regarding the presentation of motives for alcohol consumption and negative experiences with medical professionals. At the same time, collective orientation patterns such as ‘mother images’ or the mother role including their role assignments were expressed to a particular extent.

It is well known that in online forums, in addition to the people who actively post, there are also many people who are just ‘silent readers’, which was first recognized by Hill et al. (1992). Some authors claim that up to 90% of the users are ‘silent readers’ (Nielsen, 2006). In the therapeutic context, there are increasing discussions of how and whether ‘lurkers’ can be encouraged to become more actively involved, or whether lurking is an appropriate and helpful way of using online forums (Bozkurt et al., 2020; Edelmann, 2013; Sun et al., 2014). From a methodological point of view for this study, it can be said that, similar to other data sources that require active input from the participants, it cannot be ruled out that these people would also have brought in other aspects of the research object if they had decided to disclose them. There are also parallels between the forum contributions and the interviews. While in general there are parallels between the forum contributions and the interviews, there is no degree of certainty about whether all aspects of the research object were represented due to the small number of participants in this study.

The results of our comparison relate to communication about alcohol consumption during pregnancy, the transferability to other sensitive topics has not been established.

Conclusion for Research Practice

The question of which method of data acquisition is the ‘right’ or better one cannot be answered across the board for all research questions. Rather, it is important to be aware that each data source harbors its unique benefits and risks and that the adequacy of the method for the given subject should be a central element in the decision-making process. Recruiting participants is a major challenge when it comes to sensitive and potentially stigmatizing research topics. Therefore, a more comprehensive picture of the research subject can only be achieved with a lot of effort and previous knowledge of the research field. In addition, the interaction with the researcher (or already during the recruitment process) can cause renewed stigmatization or stressful experiences in the participants. Data sources like online forums could be included in the development of the research approach or be used exclusively. In order to ensure the adequacy (Altheide & Johnson, 2011; Struebing et al., 2018) of the subject matter in the research process, researchers should remain open throughout the process and react reflexively to observations regarding the strengths and weaknesses of individual data sources in the survey and analysis process to adapt the design when and if necessary.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Annette Binder https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4253-3177

References

- Adams R. S., Ledingham E., Keyes K. M. (2022). Have we overlooked the influence of “wine-mom” culture on alcohol consumption among mothers? Addictive Behaviors, 124, 107119. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allmark P., Boote J., Chambers E., Clarke A., McDonnell A., Thompson A., Tod A. M. (2009). Ethical issues in the use of in-depth interviews: Literature review and discussion. Research Ethics, 5(2), 48–54. 10.1177/174701610900500203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altheide D. L., Johnson J. M. (2011). Reflections on interpretive adequacy in qualitative research. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research, 4, 581–594. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson L. M., Twum Antwi A., Staland Nyman C., van Rooyen D. (2018). Prevalence and socioeconomic characteristics of alcohol disorders among men and women in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Health & social care in the community, 26(1), Article e143–e153. 10.1111/hsc.12487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey B. A., Sokol R. J. (2008). Pregnancy and alcohol use: evidence and recommendations for prenatal care. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology, 51(2), 436–444. 10.1097/grf.0b013e31816fea3d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh J. A., McKenna K. Y., Fitzsimons G. M. (2002). Can you see the real me? Activation and expression of the “true self” on the Internet. Journal of social issues, 58(1), 33–48. 10.1111/1540-4560.00247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergen N., Labonté R. (2020). Everything Is Perfect, and We Have No Problems”: Detecting and Limiting Social Desirability Bias in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Health Research, 30(5), 783–792. 10.1177/1049732319889354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder A., Hanke S., Petersen K. U., Huber C., Banabak M., Preiser C., Batra A. (2020). Meinungen zum Alkoholkonsum in der Schwangerschaft und zur diesbezüglichen ExpertInnenrolle von medizinischem Fachpersonal. Zeitschrift für Geburtshilfe und Neonatologie, 225(03), 216–225. 10.1055/a-1299-2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder Annette, Preiser Christine. (2021). Kompetenter Einsatz qualitativer Methoden in der Suchtforschung: Theoretische, methodologische und ethische Voraussetzungen. Sucht, 67(5), 273–280. 10.1024/0939-5911/a000731 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloor M., Fincham B., Sampson H. (2010). Unprepared for the worst: Risks of harm for qualitative researchers. Methodological Innovations Online, 5(1), 45–55. 10.4256/mio.2010.0009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bock G. (1983). Racism and sexism in Nazi Germany: Motherhood, compulsory sterilization, and the state. Signs: journal of Women in Culture and Society, 8(3), 400–421. 10.1086/493983 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt A., Koutropoulos A., Singh L., Honeychurch S. (2020). On lurking: Multiple perspectives on lurking within an educational community. The Internet and Higher Education, 44, 100709. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckman A. (2002). Ethical guidelines for research online. Georgia Institute of Technology. [Google Scholar]

- Carson G., Cox L. V., Crane J., Croteau P., Graves L., Kluka S., Koren G., Martel M. J., Midmer D., Poole N., Senikas V., Wood R., Nulman I. (2017). No. 245-Alcohol use and pregnancy consensus clinical guidelines. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 39(9), Article e220–e254. 10.1016/j.jogc.2017.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini M. (2019). Reinforcing and Reproducing Stereotypes? Ethical Considerations When Doing Research on Stereotypes and Stereotyped Reasoning. Societies, 9(4), 79. 10.3390/soc9040079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Clark A. M., Sousa B. J. (2018). The mental health of people doing qualitative research: Getting serious about risks and remedies. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Sage CA. [Google Scholar]

- Collier D., Mahoney J. (1996). Insights and pitfalls: Selection bias in qualitative research. World Politics, 49(1), 56–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25053989 [Google Scholar]

- Conlon C., Timonen V., Elliott-O’Dare C., O’Keeffe S., Foley G. (2020). Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 947–959. 10.1177/1049732319899139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. W., Lara J. L., Shah B. B., Mitchell K. T., Simmes D., Jones K. L. (2017). The public stigma of birth mothers of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 41(6), 1166–1173. 10.1111/acer.13381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. W., Shah B. B., Lara J. L., Mitchell K. T., Simmes D., Jones K. L. (2018). Addressing the public health concerns of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: Impact of stigma and health literacy. Drug and alcohol dependence, 185, 266–270. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couvrette A., Brochu S., Plourde C. (2016). The “deviant good mother” motherhood experiences of substance-using and lawbreaking women. Journal of Drug Issues, 46(4), 292–307. 10.1177/0022042616649003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford E. C., Daniel E. S., Yakubova M., Peiris I. K. (2020). Connecting without connection: using social media to analyze problematic drinking behavior among mothers. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 41(2), 121–143. 10.1080/10641734.2019.1659195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]