Abstract

The basis of specificity between pore-forming colicins and immunity proteins was explored by interchanging residues between colicins E1 (ColE1) and 10 (Col10) and testing for altered recognition by their respective immunity proteins, Imm and Cti. A total of 34 divergent residues in the pore-forming domain of ColE1 between residues 419 and 501, a region previously shown to contain the specificity determinants for Imm, were mutagenized to the corresponding Col10 sequences. The residue changes most effective in converting ColE1 to the Col10 phenotype are residue 448 at the N terminus of helix VI and residues 470, 472, and 474 at the C terminus of helix VII. Mutagenesis of helix VI residues 416 to 419 in Col10 to the corresponding ColE1 sequence resulted in increased recognition by Imm and loss of recognition by Cti.

Colicin-producing bacteria protect themselves by producing immunity proteins that exert an inhibitory role through protein-protein interactions with the activity domain of their cognate colicin (3, 4, 6). Immunity proteins active against the pore-forming colicins are localized in the cytoplasmic membrane (2, 7), where they inhibit channel-formation during the process of colicin association with the membrane.

The pore-forming colicins, including E1, A, B, Ia, Ib, N, 10, 5, and K, are composed of three major domains, including the C-terminal channel domain that forms a voltage-gated ion channel in the cytoplasmic membrane sufficiently conductive to depolarize and kill the cell. The structure of the soluble channel-forming domain of colicins A, E1, and Ia have been determined by using X-ray crystallography and shown to form a 10-helix bundle composed of eight α-helices surrounding a central hydrophobic helical hairpin (5, 13, 19). Upon membrane binding, the outer helices extend into a flexible, two-dimensional helical net embedded in the interfacial or lipid headgroup region of the membrane (12, 20). Application of a voltage induces the hydrophobic hairpin, helix VI, and a variable upstream region to adopt a transmembrane orientation, leading to the formation of the open channel (10, 16).

The immunity protein for colicin E1 (ColE1), Imm, is a 13-kDa integral membrane protein, composed of three transmembrane helices (18). imm+ Escherichia coli are resistant to a titer of purified ColE1 that is 104 to 105 greater than is needed to kill imm strains. Although it is known that the immunity protein of the pore-forming colicins interacts with the C-terminal channel domain (2, 8, 15), neither the structure of this inhibitory complex nor the specific residues which determine the colicin-immunity interaction are understood. A key aspect of the colicin-immunity interaction is that the different channel-forming colicins are recognized to different extents by immunity proteins cognate to other colicins. In previous studies, creation of hybrid proteins between related colicins has been used to identify regions that determine immunity recognition between the A-type colicins, ColA and ColB (8), and also between two E-type colicins, Col5 and Col10 (15). Prior to the identification of Col10 (14), no colicin had been identified with sufficient sequence similarity to ColE1 to use this approach for the identification of residues involved in ColE1 association with Imm.

Extensive structural and genetic analyses have been conducted on the enzymatic colicins (i.e., E7 and E9) which are cosynthesized with soluble immunity proteins that bind to the colicin activity domain within the producing cell. Like the pore-forming colicins, enzymatic colicins exhibit a high degree of specificity in binding their immunity proteins. Mutagenesis and thermodynamic studies have revealed that, while many residues conserved between ColE7 and ColE9 are involved in binding their respective immunity proteins as predicted here, it is the divergent residues that determine the specificity of the colicin-immunity interaction (4, 11).

Substitution of residues 419 to 501 in ColE1 with the corresponding region from Col10 reverses recognition by Imm and Cti.

The channel-forming domains of ColE1 and Col10 share 62% amino acid identity (Fig. 1) but are “recognized” to different degrees by Imm and Cti, the immunity proteins for ColE1 and Col10. Colicin activity is generally assayed using spot tests wherein sensitive indicator cells (E. coli K17), with or without genes for immunity protein, are grown to mid-log phase and spread on agar plates, and dilutions of colicins are deposited on the dried surface. Such tests reveal that imm+ E. coli are >105-fold more resistant (or immune [“Im”] in Table 1) to ColE1 than E. coli lacking immunity protein. cti+ E. coli shows similar levels of resistance to Col10. However, unlike imm+ E. coli that has little if any resistance to Col10, cti+ E. coli is resistant to an at least 103-fold-higher titer of ColE1 than E. coli without immunity. Thus, the immunity protein for Col10 confers some resistance to ColE1, but the immunity protein for ColE1 provides no detectable immunity against Col10 (Table 1, section A, and Fig. 2).

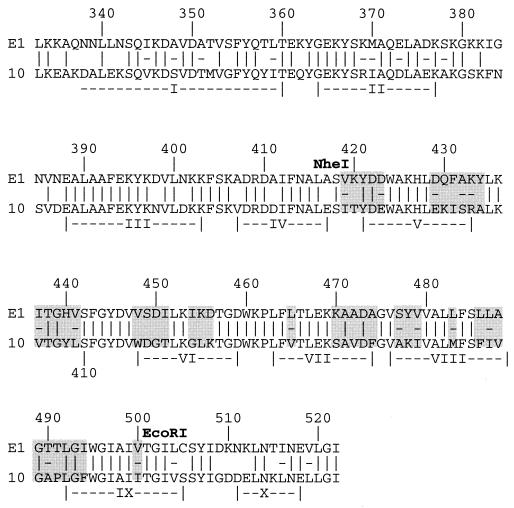

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of the channel domains of ColE1 and Col10. The locations and identities of the α-helices identified from the X-ray crystal structure of soluble ColE1 (7) are indicated. Identical residues are indicated (|), and similar residues are marked as well the (-). Residues mutagenized simultaneously are outlined with shaded boxes. Restriction sites used in the construction of the mutations are indicated.

TABLE 1.

Relative activities of ColE1, Col10, Col10, and mutagenized ColE1 on E. coli in the absence of immunity protein or on E. coli expressing Imm or Cti

| Section | Colicin

|

Relative activities on E. coli expressinga:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Mutation result | No protein | Imm | Cti | |

| A | |||||

| ColE1 | 4 (5)∗ | Im | 1∗∗ | ||

| Col10 | 4 (5) | 4 (5) | Im | ||

| ColE1-Col10(419–503) | 3 (5) | 3 (4) | Im | ||

| ColE1 mutants | |||||

| B | 419 VK--Db | IT--E | 4 (5) | Im | 1 (2) |

| 429 DQFAKY | EKISRA | 4 (5) | Im | 1 | |

| 437 I--HV | V--YL | 4 (5) | Im | 1 (2) | |

| 448 VSDI | WDGT | 4 (5) | 2 | (1)c | |

| 448 VSDI--IKD | WDGT--GLK | 4 (5) | 2 | (1) | |

| 454 IKD | GLK | 4 (5) | Im | 1 | |

| 465 L----K-A-A | V----S-V-F | 4 (5) | Im | (1) | |

| 470 K-A-A | S-V-F | 4 (5) | Im | (1) | |

| 477 S-Y-V | A-K-I | 4 (5) | Im | 1 (2) | |

| 483 L--LLA-TT--I | M--FIV-AP--F | 4 | Im | 1 | |

| 486 LLA-TT--I-----V | FIV-AP--F-----I | 4 | Im | 1 | |

| C | 448 V | W | 4 (5) | 2 | 1 |

| 449 S | D | 4 (5) | Im | 1 | |

| 450 D | G | 4 (5) | Im | 1 | |

| 451 I | T | 4 (5) | Im | 1 | |

| 449 SDI--IKD | DGT--GLK | 4 (5) | Im | (1) | |

| D | 448 V | Y | 4 (5) | 2 | (1) |

| 448 V | R | 4 (5) | 2 | 2 (3) | |

| E | 448 VSDI--IKD/ | WDGT--GLK/ | 4 | 2 | (1) |

| 419 VK--D | IT--E | ||||

| 448 VSDI--IKD/ | WDGT--GLK/ | 3 (4) | 1 (2) | Im | |

| 429 DQFAKY | EKISRA | ||||

| 448 VSDI--IKD/ | WDGT--GLK/ | 4 | 1 | Im | |

| 437 I--HV | V--YL | ||||

| 448 VSDI--IKD/ | WDGT--GLK/ | 4 | 2 | Im | |

| 470 K-A-A | S-V-F | ||||

| 448 VSDI--IKD/ | WDGT--GLK/ | 4 (5) | 2 | (1) | |

| 486 LLA-TT--I | FIV-AP--F | ||||

The amount of protein used for each assay was adjusted to yield similar levels of activity toward E. coli pT7-7, although the cytotoxicity per milligram of protein varied. The ColE1-Col10(419–503) mutant exhibited a 20-fold reduction relative to wild-type ColE1 and Col10. The mutants listed in sections B, C, D, and E exhibited reductions in cytotoxicity relative to the wild type of 2- to 5-fold, 0, 0, and 7- to 10-fold, respectively. ∗ and ∗∗, 104-fold-diluted (105-fold-diluted in parentheses) and 10-fold-diluted, respectively, colicin samples yielded a clear (slightly turbid) zone on indicator plates; Im, immune phenotype in which no indication of zone clearing with undiluted colicin was detected.

The residue number of the first mutagenized amino acid in each series is indicated on the left. The locations of unmutagenized amino acids are indicated by hyphens.

The sample yielded slightly turbid spots at 0- and 10-fold dilutions.

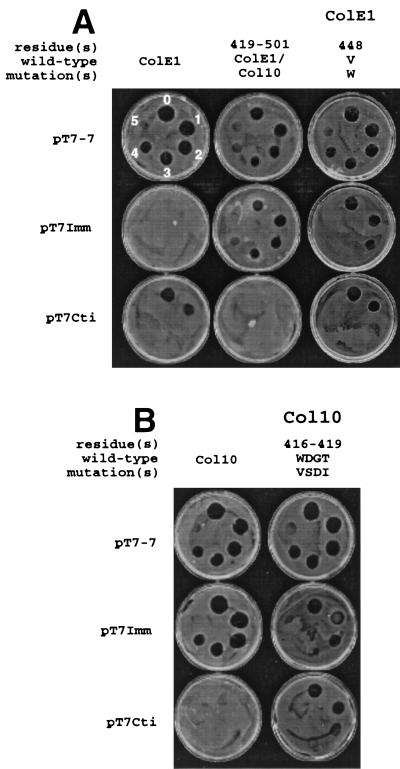

FIG. 2.

Colicin activity tests on E. coli K17(DE3) indicator cells containing pT7-7, pT7Imm, or pT7Cti. Undiluted colicin was spotted onto the indicator cells at the top center of each plate with serial dilutions applied to the plate in a clockwise fashion where “1” represents a 10-fold dilution, “2” represents a 102-fold dilution, etc., with the starting concentration adjusted so as to yield equivalent levels of cytotoxicity on E. coli (pT7-7). Relative activities are displayed for wild-type ColE1, the ColE1-Col10 hybrid colicin with residues 419 to 501 derived from Col10, and ColE1 carrying the V448W mutation (A) and for wild-type Col10 and Col10 mutagenized to the ColE1 sequence at residues 416 to 419 (B). The locations of the mutations, the wild-type sequence, and the sequence in the mutagenized version are indicated above each column of activity tests. Locations of unmutagenized residues within the given regions are indicated (−). Each test was repeated a minimum of three times, and a representative example is shown.

In preparation for the construction of mutants with altered immunity recognition, cti was amplified from pHP10 by PCR and cloned into pT7ColE1-Imm to create pT7ColE1-Imm-Cti. Following insertion of a novel NheI site into the codons for ColE1 residues 417 to 418, the codon region from residues 419 to 501 in Col10 was amplified, and the product was cloned into the Nhe and EcoRI sites of colE1. The hybrid colicin, ColE1-Col10(419–501), produced by this clone was found to have relative activity levels toward imm+ and cti+ E. coli comparable to that of wild-type Col10 (Table 1, section A, and Fig. 2A). For these experiments, imm and cti were cloned into pT7-7 and expressed constitutively, providing the indicator cells with a level of resistance to wild-type ColE1 and Col10 comparable to that afforded by original pColE1 and pCol10 plasmids.

Substitution of all divergent residues in ColE1 between residues 419 and 501 reveals two regions involved in immunity protein recognition.

Comparison of the ColE1 and Col10 sequences reveals the presence of 34 divergent amino acids between residues 419 and 501 (Fig. 1), the locations of which suggest several candidate regions for immunity recognition. The segment in the sequence corresponding to helix VI in the X-ray crystal structure (5) is an obvious candidate since it encompasses the region of highest divergence between both ColE1 and Col10, as well as between Col10 and Col5. Construction of reciprocal hybrid proteins from Col10 and Col5 has confirmed that candidate recognition determinants include this region (15). Divergent residues between 470 and 480 are also potential recognition determinants (22), as are divergent residues in the turn region from residues 484 to 494 of the hydrophobic hairpin (8, 17).

To evaluate the involvement of these regions, as well as the potential roles of the other divergent residues in the interaction of ColE1 with Imm and Cti, nonconserved residues in ColE1 were mutagenized to the corresponding sequences in Col10 using the PCR-based “megaprimer” method (1). Plasmids were purified using standard techniques, and sequencing was performed by the Purdue Center for DNA Sequencing. Wild-type and mutagenized ColE1 were purified as previously described (21) and quantitated using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.).

The majority of the introduced mutations did not cause any change in the activity of ColE1 toward cells expressing Imm or Cti relative to cells lacking immunity protein (Table 1, section B). These included mutations in residues 429 to 434 in helix V, where the sequence was changed from 429 DQFAKY to 429 EKISRA and the helix V-VI loop (changed to 437 V--YL), as well as those in the hydrophobic hairpin and the interhelical loop (changed to 483 M--FIV-AP--F-----I). The only region for which substitution of Col10 sequences led to increased (102 to 103-fold) activity toward imm+ E. coli was the N-terminal half of helix VI (changed to 448 WDGT) (Table 1, section B). In addition to showing increased activity on imm+ E. coli, ColE1 carrying the 448 WDGT mutation exhibited a subtle but reproducible decrease in activity toward cti+ E. coli as manifested by increased turbidity at the dilutions at which ColE1 is active. A similar decrease in relative activity toward cti+ E. coli was observed for ColE1 carrying the mutations 470 S-V-F (Table 1, section B). Activity for the various mutants is presented in relative terms, since levels of cytotoxicity toward E. coli lacking immunity varied, with reductions in cytotoxicity generally correlated to the number of mutations that had been introduced. The initial hybrid colicin, ColE1-Col10(419–501) was 20-fold less cytotoxic toward E. coli lacking immunity than ColE1, while the mutants described in this section (Table 1, section B) exhibited 2- to 5-fold reductions in cytotoxicity.

Mutagenesis of V448 alters ColE1 recognition by Imm and Cti.

Specific sites in helix VI involved in recognition by Imm and Cti were identified by individually mutagenizing residues 448 to 451 to their corresponding Col10 sequences. ColE1 carrying the V448W mutation showed enhanced activity toward imm+ E. coli similar to that observed for the 448 WDGT mutation (Table 1, section C, and Fig. 2A), while the S449D, D450G, and I451T mutations had no effect on activity relative to wild type ColE1 (Table 1, section C). When activity levels toward cti+ E. coli were evaluated, none of the mutations caused an increase in recognition by Cti relative to wild-type ColE1 (Table 1, section C), suggesting that the increased turbidity observed for ColE1 448 WDGT on cti+ E. coli is determined by two or more residues. Residues in the 474 S-V-F region, at the C terminus of helix VII (5), were also mutagenized individually, but none led to an increase in Cti recognition relative to wild-type ColE1, indicating that the increased turbidity observed for ColE1 474 S-V-F on cti+ E. coli is similarly determined by two or more residues (data not shown).

Because the V448W mutation significantly altered the interaction of ColE1 with Imm, the effects of substituting alternative residues at this site were tested. Both the mutations V448Y and V448R in ColE1 resulted in an increase in activity toward imm+ E. coli comparable to that of ColE1 carrying the V448W mutation. Introduction of V448Y to ColE1 resulted in decreased activity toward cti+ E. coli relative to ColE1 V448W (Table 1, section D). In contrast, the V448R mutation led to a 102-fold enhancement of activity toward cti+ E. coli relative to ColE1 V448W (Table 1, section D). No reduction in cytotoxicity toward E. coli lacking immunity was observed for ColE1 carrying mutations at a single site. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the identity of residue 448 can alter interactions between ColE1 and both immunity proteins even though the V448W mutation alone does not confer enhanced recognition by Cti.

Although ColE1 448 WDGT and ColE1 V448W exhibit an increase in activity toward imm+ cells and, in the case of ColE1 448 WDGT, a slight decrease in activity toward cti+ E. coli, these mutations caused only a partial conversion to the Col10 phenotype. To determine whether mutagenesis of additional regions of ColE1 448 WDGT--GLK would produce a phenotype more closely resembling that of Col10, the 419 IT--E, 429 EKISRA, 437 V--YL, 470 S-V-F, and 486 FIV-AP--F mutations were individually introduced into ColE1 448 WDGT--GLK. ColE1 carrying the combined mutations exhibited 7- to 10-fold decreases in cytotoxicity toward E. coli lacking immunity, but none showed an increase in relative activity toward imm+ E. coli equivalent to that observed for Col10. However, addition of 470 S-V-F to 448 WDGT--GLK resulted in loss of the small amount of residual activity observed for ColE1 with 448 WDGT--GLK toward cti+ E. coli (Table 1, section E). A similar loss in activity toward cti+ E. coli was observed when 437 V--YL was added to 448 WDGT--GLK, although this change was paralleled by a loss in activity on imm+ E. coli as well (Table 1, section E). These results suggest that while residue 448 is the predominant determinant governing association between ColE1 and Imm, multiple residue changes in both the N terminus of helix VI and the C terminus of helix VII are required to induce complete recognition of ColE1 by Cti.

Substitution of Col10 residues 416 to 419 with residues 448 to 451 from ColE1 causes loss of recognition by Cti and increased recognition by Imm.

The structural gene for Imm was introduced into pHP10, the expression plasmid for Col10, and residues 416 to 419, predicted to be at the N terminus of helix VI in Col10 (Fig. 1), were mutagenized to VSDI, the corresponding sequence from ColE1 (Fig. 1). Wild-type and mutagenized Col10 were purified as described elsewhere (15). The resulting protein was found to have a 103-fold increase in activity toward cti+ E. coli and a 102-fold decrease in activity toward imm+ E. coli relative to wild-type Col10 (Fig. 2B), thus confirming that residues at the N terminus of helix VI are important for immunity protein recognition in Col10 as well as ColE1.

The result obtained here support and extend the model previously proposed by Pilsl and Braun that inactivation of E-type colicins by their immunity proteins occurs via interaction between the voltage-gated regions of colicin and the transmembrane helices in immunity proteins (15). Studies of the membrane-bound, closed-channel state indicate that helix VI is positioned within the headgroup region, parallel to the plane of the membrane (20). As such, it would be accessible only to the small periplasmic loop of immunity protein, deletion of which has been shown to have no effect on the colicin-immunity association (9). However, upon voltage-gating, helix VI adopts a transmembrane orientation, placing it proximal to the transmembrane helices of immunity protein which have been shown, in the Col10 and Col5 systems, to contain colicin recognition determinants (15). The C terminus of helix VII, containing residues 470 to 474 and implicated in recognition by Cti, is believed to become part of transmembrane helix VIII upon membrane binding (5), placing residues 470 to 474 proximal to the transmembrane helices of immunity protein. Future studies on the interaction of ColE1 and Imm will focus on biochemical and biophysical evaluation of the association between wild-type or mutagenized ColE1 and Imm in artificial vesicles, as well as mutagenesis of the immunity protein residues likely to be positioned at a depth similar to that of ColE1 residue 448.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Braun for providing pHP10 and K. Takahashi of the Kyowa Hakko Kogyo Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan, for the kind gift of mitomycin C.

This work was supported by NIH grant GM-18457.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barik S. Site-directed mutagenesis by double polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biotech. 1995;3:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02821329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop L J, Bjes E S, Davidson V L, Cramer W A. Localization of the immunity protein-reactive domain in unmodified and chemically modified COOH-terminal peptides of colicin E1. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:237–244. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.237-244.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cramer W A, Heymann J B, Schendel S L, Deriy B N, Cohen F S, Elkins P A, Stauffacher C V. Structure-function of the channel-forming colicins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1995;24:611–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bb.24.060195.003143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cramer W A, Lindeberg M, Taylor R. The best offense is a good defense. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:295–297. doi: 10.1038/7520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elkins P, Bunker A, Cramer W A, Stauffacher C V. A mechanism for protein insertion into the membranes is suggested by the crystal structure of the channel-forming domain of colicin E1. Structure. 1997;5:443–458. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Espesset D, Piet P, Lazdunski C, Geli V. Immunity proteins to pore-forming colicins: structure-function relationships. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geli V, Baty D, Lazdunski C. Use of a foreign epitope as a “tag” for the localization of minor proteins: the case of the immunity protein to colicin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:689–693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geli V, Lazdunski C. An α-helical hydrophobic hairpin as a specific determinant in protein-protein interaction occurring in Escherichia coli colicin A and B immunity systems. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6432–6437. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6432-6437.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heymann J B. Channel formation of colicin E1 and purification and modeling of its immunity protein. Ph.D. thesis. West Lafayette, Ind: Purdue University; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kienker P K, Qiu X-Q, Slatin S L, Finkelstein A, Jakes K S. Transmembrane insertion of the colicin Ia hydrophobic hairpin. J Membr Biol. 1997;157:27–37. doi: 10.1007/s002329900213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleanthous C, Hemmings A M, Moore G R, James R. Immunity proteins and their specificity for endonuclease colicins: telling right from wrong in protein-protein recognition. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:227–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindeberg M, Zakharov S D, Cramer W A. Unfolding pathway of the colicin E1 channel protein on a membrane surface. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:679–692. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker M W, Postma P M, Pattus F, Tucker A D, Tsernoglou D. Refined structure of the pore-forming domain of colicin A at 2.4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 1992;224:639–657. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90550-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pilsl H, Braun V. Novel colicin 10: assignment of four domains to TonB- and TolC-dependent uptake via the Tsx receptor and to pore formation. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:57–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pilsl H, Braun V. Evidence that the immunity protein inactivates colicin 5 immediately prior to the formation of the transmembrane channel. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6966–6972. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.23.6966-6972.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qui X-Q, Jakes K S, Kienker P K, Finkelstein A, Slatin S L. Major transmembrane movement associated with colicin Ia channel gating. J Gen Physiol. 1996;107:313–328. doi: 10.1085/jgp.107.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smajs D, Pilsl H, Braun V. Colicin U, a novel colicin produced by Shigella boydii. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4919–4928. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4919-4928.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song H Y, Cramer W A. Membrane topography of the colE1 gene products: the immunity protein. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2935–2943. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2935-2943.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiener M, Freymann D, Ghosh P, Stroud R M. Crystal structure of colicin Ia. Nature. 1997;385:461–464. doi: 10.1038/385461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zakharov S D, Lindeberg M, Griko Y, Salamon Z, Tollin G, Prendergast F G, Cramer W A. Membrane-bound state of the colicin E1 channel domain as an extended two-dimensional helical array. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4282–4287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y-L, Cramer W A. Constraints imposed by protease accessibility on the trans-membrane and surface topography of the colicin E1 ion channel. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1666–1676. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y-L, Cramer W A. Intramembrane helix-helix interactions as a basis of inhibition of the colicin E1 ion channel by its immunity protein. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:10176–10184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]