Abstract

Introduction

Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is defined as the loss of two or more conceptions before 24 weeks gestation. Despite extensive diagnostic workup, in only 25%–40% an underlying cause is identified. Several factors may increase the risk for miscarriage, but the chance of a successful pregnancy is still high. Prognostic counselling plays a significant role in supportive care. The main limitation in current prediction models is the lack of a sufficiently large cohort, adjustment for relevant risk factors, and separation between cumulative live birth rate and the success chance in the next conception. In this project, we aim to make an individualised prognosis for the future chance of pregnancy success, which could lead to improved well-being and the ability managing reproductive choices.

Methods and analysis

In this multicentre study, we will include both a prospective and a retrospective cohort of at least 931 and 1000 couples with RPL, respectively. Couples who have visited one of the three participating university hospitals in the Netherlands for intake are eligible for the study participation, with a follow-up duration of 5 years. General medical and obstetric history and reports of pregnancies after the initial consultation will be collected. Multiple imputation will be performed to cope for missing data. A Cox proportional hazards model for time to pregnancy will be developed to estimate the cumulative chance of a live birth within 3 years after intake. To dynamically estimate the chance of an ongoing pregnancy, given the outcome of earlier pregnancies after intake, a logistic regression model will be developed.

Ethics and dissemination

The Medical Ethical Research Committee of the Leiden University Medical Center approved this study protocol (N22.025). There are no risks or burden associated with this study. Participant written informed consent is required for both cohorts. Findings will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presentations at international conferences.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Reproductive medicine, Maternal medicine, EPIDEMIOLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

A prognostic model that estimates the chance of a live birth within 3 years in couples with recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) will be developed using the Cox proportional hazards method.

Logistic regression modelling enables dynamically updating live birth chances given the outcome of pregnancies after intake.

A large cohort will be used for the development of a robust model, using the Prediction model study Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool as a guide to control bias.

The retrospective cohort could be prone to response and recall bias.

Primary prediction model will not be able to distinguish between different associated RPL factors.

Introduction

Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is defined as the loss of two or more conceptions before 24 weeks of gestation.1 This condition affects approximately 1%–3% of all fertile couples.2 3 RPL is a highly heterogeneous condition with multiple known maternal risk factors, varying from autoimmune diseases (antiphospholipid syndrome, antithyroid antibodies), parental balanced chromosomal translocations and congenital uterine abnormalities to advanced maternal age, maternal smoking and alcohol consumption. In addition to these maternal factors, a potential contribution of paternal factors (such as male age, lifestyle factors and DNA fragmentation) has been recognised to add to the risk for miscarriages.4–6

Despite extensive diagnostic workup offered to couples with RPL, underlying risk factors can be identified in only 25%–40% of couples.7 8 Limited understanding of mechanisms underlying RPL has the consequence that effective treatment options are often lacking. When no evidence-based therapeutic options are available for couples with RPL, clinical management is primarily focused on providing supportive care. Supportive care and intensive pregnancy surveillance in the first weeks of gestation are assumed to be of influence in the prevention of new pregnancy loss.9

Part of this supportive care is counselling on the prognosis and live birth rate of subsequent pregnancies in couples with RPL. Recently, we conducted a systematic search to identify and assess the methodological quality of existing prediction models.10 This review included the two most frequently used models which provide an estimate of subsequent chance of ongoing pregnancy/live birth in couples with unexplained RPL.11 12 The model of Lund et al is actually not suitable for individual risk assessment, as stated by the authors themselves.12 The model of Brigham et al has been implemented in RPL care in the Netherlands and the UK.11 13 14 These studies; however, did not follow the nowadays recommended Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) guideline in the development and reporting of the model.15 For example, neither of the models were internally nor externally validated and this could influence the validity and performance of the model. Recently, we showed that the Brigham prediction model has poor performance in a Dutch RPL cohort, possibly due to a low number of patients included and a substantial change of the RPL population since 1999, in light of changes in defining unexplained RPL.16

Most studies only concentrate on the outcome of the first pregnancy after intake as primary outcome of the model, which lacks future perspective for couples with RPL. In addition, all earlier prediction models focused on the unexplained RPL population and on maternal predictors. None of them incorporated different causes for RPL, nor did they include paternal factors to establish a prediction specific to individual couples.17 Furthermore, obstetric complications after RPL are not part of these models.18 19

Individual couples with RPL now have an unclear prognosis of future success in terms of having a live birth. The aim of the current project is therefore to develop a prediction model that is able to provide tailormade estimates of pregnancy success in couples with both unexplained and explained RPL, and secondarily to develop a dynamic model that adjusts future chances based on pregnancies after intake.

Study objectives

Primary objective

To predict the chance of a live birth within 3 years after intake in couples with unexplained RPL.

Secondary objectives

To predict the chance of an ongoing pregnancy (>12 weeks) in the next pregnancy in couples with unexplained RPL.

To predict the chance of a complicated pregnancy in couples with unexplained RPL (pre-eclampsia, HELLP, eclampsia, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, preterm birth, low birth weight).

To predict the chance of a live birth dynamically given the outcome of a previous pregnancy after intake.

To predict the chance of above outcomes in couples with a known cause for RPL.

Methods and analysis

Study design

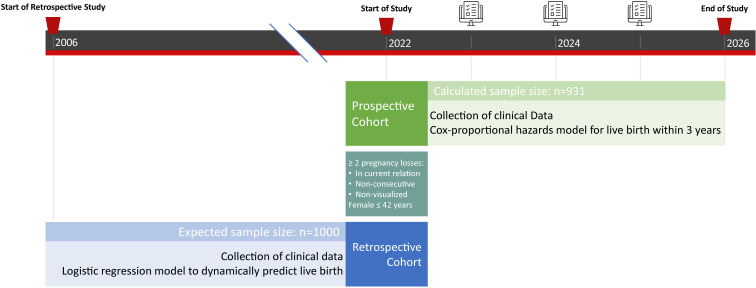

A multicentre hospital-based prospective and retrospective cohort study to develop a prediction model. This study has a total expected duration of 5 years (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of study design.

Eligibility criteria

Couples with the following criteria at intake visit will be included:

-

RPL in the current relationship: defined as the loss of ≥2 preceding pregnancies. These pregnancy losses include following:

All pregnancy losses before the 24th week of gestation verified by ultrasonography or uterine curettage and histology.

Non-visualised pregnancies (including biochemical pregnancy losses and/or resolved and treated pregnancies of unknown location), verified by positive urine or serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).

Both consecutive and non-consecutive pregnancy losses.

Dutch or English speaking by either the male or the female of the couple.

Couples with females aged ≤42 years.

Couples will be excluded in case of mental or legal incapability of either male or female, or in case of <2 pregnancies in current relationship.

Study population and recruitment

RPL couples that visit the RPL outpatient clinic of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC), or early pregnancy unit of the Erasmus University Medical Center (Erasmus MC) or Amsterdam University Medical Center will be assessed for eligibility. The LUMC is the coordinating centre. After referral, couples will have an intake at one of the aforementioned centers, where they will be invited to participate in this study. If eligibility criteria are met, and in case of consent, couples will be selected for inclusion. In addition to this prospective inclusion of patients, couples who have visited the aforementioned clinics between 2006 and 2021 will be included retrospectively.

Couples will receive written information about both the prospective and retrospective cohort, and a concomitant informed consent form. The informed consent consists of a request to obtain data from their medical records for this study, together with a request to obtain data from other medical professionals in case pregnancies were monitored in other centres. Study information underlines that participation is voluntary, and that couples are free to withdraw from the study at any time point without any consequences.

Study inclusion started in April 2022 in the LUMC. The start of inclusions in other participating centres is pending. The estimated date of completion in each centre is 5 years after the first inclusion. General medical history, lifestyle data and obstetric history will be collected for all couples (see table 1). Data will be collected during the initial intake visit. Uniformity in data collection between the participating centres will be ensured through templates. Digital surveys will be sent to participating couples to obtain additional data. All information will be stored in the electronic data capture software Castor EDC (Electronic Data Capture).

Table 1.

Collection of clinical characteristics

| Female | Date of birth, female age, alcohol consumption, smoking, caffeine intake, drugs intake, exercise pattern, education, BMI, blood pressure, general medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, surgeries, earlier blood transfusions), use of medication, ethnicity and family history. |

| Male | Date of birth, male age, alcohol consumption, smoking, caffeine intake, drugs intake, exercise pattern, education, BMI, general medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, surgeries, etc), use of medication, ethnicity and family history. |

| Obstetric history | Parity, no of miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies or induced abortions, mode of conception, mode of delivery of previous births, gestational age at previous births, birth weight of children of previous births. |

| RPL examination | Presence of antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin IgG and IgM, β2 glycoprotein I antibodies IgG and IgM, and lupus anticoagulant), thyroid function (thyroid-stimulating hormone), presence of thyroid antibodies, parental chromosomal abnormalities and presence of congenital uterine anomalies. |

BMI, body mass index; RPL, recurrent pregnancy loss.

Couples participating in the prospective cohort will be followed for a total of 5 years after initial visit. Annual questionnaires will be digitally sent to obtain data of new pregnancies and/or changes in health or lifestyle. If follow-up has taken place in one of the participating centres, couples will not have to fill in these questionnaires, but data will rather be obtained during consultation. Couples participating in the retrospective cohort will receive an online questionnaire in case of missing data.

Control of bias

According to the PROBAST-tool,20 risk of bias in prediction model development studies can be divided into four domains: participants, predictors, outcome and analysis. Study population is clearly defined, minimising selection bias in the participants domain. As clinicians in the participating centres perform intakes in a semi-standardised manner, predictors will be assessed in a similar way for all participants. The outcome is clearly defined and determined: urine or serum hCG measurement or heartbeat on ultrasound determine an ongoing pregnancy. To ensure that the analysis domain is not at risk of bias, the PROBAST-items of that domain will be followed. For the retrospective cohort, there is a risk of recall bias. Since intake visits are semistructured, information at baseline is moderately similar across all inclusions. For additional information that has to be collected retrospectively, we aim to minimise recall bias by avoiding recall periods longer than 5 years.

Sample size calculation

The method of Riley et al is used for the calculation of the required size in prediction models for the prospective cohort.21 This method consists of four steps and four different sample sizes, after which the largest one is selected as the study sample size. The four steps ensure a precise estimate of the overall outcome risk, predicted values with a small mean error across all individuals, a small required shrinkage of predictor effects and a small optimism in apparent model fit. Using an anticipated outcome proportion of 0.65 (live birth), 12 predictor parameters, a shrinkage of 0.9 and an anticipated R2cs of 0.1089, the largest sample size and thus this study’s prospective cohort sample size is 931. The expected retrospective cohort size is 1000, based on a retrospective study period between 2006 and 2021 (approximately 200 patients per year for every participating centre). This results in a minimum cohort size of 1931 RPL couples.

Study outcomes

The following predictors were selected based on current literature, and will be assessed at intake8 11 12 22–24:

Female age as a continuous variable.

Male age as a continuous variable.

Female body mass index (BMI) as a continuous variable.

Male BMI as a continuous variable.

Current female smoking as a categorical variable.

Current male smoking as a categorical variable.

Number of pregnancy losses as a categorical variable (2, 3, 4 and 5 or more).

Heartbeat on ultrasound in obstetrical history as a binary variable.

Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) in previous pregnancies as a binary variable.

Identification of an associated RPL factor as a binary variable.

The following outcomes will be studied:

Live birth within 3 years after initial intake visit (defined as the birth of a living child after 24 weeks gestation).

Pregnancy outcomes since intake.

Time to pregnancy since intake.

Time between pregnancies since intake.

-

Pregnancy complications since intake, for example,

Pre-eclampsia.

HELLP syndrome (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelets).

Eclampsia.

Gestational diabetes.

Gestational hypertension.

Preterm birth.

Low birth weight.

Statistical analysis plan

For the primary objective (live birth within 3 years after intake), we will develop a Cox proportional hazards model for time to pregnancy, including couples without full 3-year or 5-year outcome information. For the secondary objective, a logistic regression model for the binary outcome live birth in couples who conceived after their RPL intake will be developed. This will be used to dynamically predict live birth, given the outcome of pregnancies after intake.

We will consider both simple linear and non-linear (restricted cubic splines) functions for continuous variables. The best fitting model is selected based on the Akaike information criterion which reflects the trade-off between information and model complexity (variable selection). Measurement of the Area Under the Curve (AUC), the Brier score and calibration of the model will be performed (model performance). Internal validation will be performed using the bootstrapping method.

To cope with missing values (missing at random, missing completely at random), multiple imputation will be performed. Once the dataset is complete, cross-validation of the previously selected variables will be performed, variables with a low predictive strength will be excluded.

External validation will be performed using data of hospitals which have not participated in this study.

Patient and public involvement

The Dutch association for patients with fertility problems (Freya) was consulted during the development of the study protocol. Study information will be published on their website, and information on progress and results will be presented to patients during meetings organised by Freya.

Ethics and dissemination

This study will be conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Medical Research Ethics Committee of the LUMC provided ethical approval for this study (N22.025). There are no risks or burden involved in this study. Participant informed consent will be required for both the prospective and retrospective cohort. All data will be collected during regular hospital visits or via questionnaires. Eligible couples will have sufficient time to decide on participating in this study, after having received written information. The Castor EDC database of the OPAL study will contain all clinical and survey data. This database will not include directly traceable patient data. The findings of this study will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publications and presentations at international conferences.

Discussion

The perspective of a live birth is one of the most important aspects of RPL. Prognostic counselling plays a very important role in the RPL clinical practice, especially in the absence of an underlying risk factor and with the lack of treatment options. Different prognostic tools exist and are implicated in RPL care in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, but these tools are often of low quality.10

In order to enable prediction of a live birth within 3 years after initial intake visit, or to dynamically predict the chance of a live birth, a long follow-up period is necessary. In this study proposal, we will, therefore, include our patients not only prospectively, but also retrospectively. Retrospective inclusion is however prone to recall bias. The initial intake visit is according to a semistructured interview, thus minimising differences between data across the retrospective cohort. In case of missing data, we will aim to minimise recall bias by avoiding recall periods longer than 5 years.

Another limitation of this study regards the predictors included in the model. There are various factors that are associated to RPL (such as sperm DNA fragmentation), which could possibly improve model performance, but we currently lack data to include these factors in a prediction model.25 We intend to update the prediction model when new evidence suggests that these predictors should be included in the counselling of RPL couples. Second, the predictor ‘identification of an associated RPL factor’ does not specify the associated factor, something that would help counselling RPL couples. Of course, as there are several factors that could be categorised, the sample size needed for the inclusion of these factors would be much higher.

The ultimate goal of this study is to accurately predict outcomes of future pregnancies, in order to aid expectation management, and provide a perspective for RPL couples. The outcomes of this study will provide tailor-made and individual prognostic assessments of live birth in couples with RPL, and will have to be externally validated to ensure generalisability.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: AY, EL and M-LvdH drafted the protocol. NvG and RvE contributed to the statistical analysis plan. All authors (AY, MG, EL, AM, MAJS, M-LvdH, RvE, NvG, JMMvL and MvW) contributed to the writing and reviewing of this article and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.ESHRE Guideline Group on RPL, Bender Atik R, Christiansen OB, et al. ESHRE guideline: recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod Open 2018;2018:hoy004. 10.1093/hropen/hoy004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jauniaux E, Farquharson RG, Christiansen OB, et al. Evidence-Based guidelines for the investigation and medical treatment of recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod 2006;21:2216–22. 10.1093/humrep/del150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rai R, Regan L. Recurrent miscarriage. Lancet 2006;368:601–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69204-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McQueen DB, Zhang J, Robins JC. Sperm DNA fragmentation and recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril 2019;112:54–60. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nybo Andersen AM, Wohlfahrt J, Christens P, et al. Maternal age and fetal loss: population based register linkage study. BMJ 2000;320:1708–12. 10.1136/bmj.320.7251.1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venners SA, et al. Paternal smoking and pregnancy loss: a prospective study using a biomarker of pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:993–1001. 10.1093/aje/kwh128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaslow CR, Carney JL, Kutteh WH. Diagnostic factors identified in 1020 women with two versus three or more recurrent pregnancy losses. Fertil Steril 2010;93:1234–43. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youssef A, Lashley L, Dieben S, et al. Defining recurrent pregnancy loss: associated factors and prognosis in couples with two versus three or more pregnancy losses. Reprod Biomed Online 2020;41:679–85. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liddell HS, Pattison NS, Zanderigo A. Recurrent miscarriage--outcome after supportive care in early pregnancy. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 1991;31:320–2. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1991.tb02811.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youssef A, van der Hoorn M-LP, van Lith JMM, et al. Prognosis in unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: a systematic review and quality assessment of current clinical prediction models. F S Rev 2022;3:136–45. 10.1016/j.xfnr.2022.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brigham SA, Conlon C, Farquharson RG. A longitudinal study of pregnancy outcome following idiopathic recurrent miscarriage. Hum Reprod 1999;14:2868–71. 10.1093/humrep/14.11.2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lund M, Kamper-Jørgensen M, Nielsen HS, et al. Prognosis for live birth in women with recurrent miscarriage: what is the best measure of success? Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:37–43. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823c0413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NVOG . Herhaalde Miskraam, 2007. Available: www.nvog-documenten.nl/richtlijn/doc/download.php?id=750

- 14.RCOG . The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent Firsttrimester and second-trimester miscarriage, 2011

- 15.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMC Med 2015;13:1. 10.1186/s12916-014-0241-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Youssef A, van der Hoorn MLP, Dongen M. External validation of a frequently used prediction model for ongoing pregnancy in couples with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum Reprod 2021. 10.1093/humrep/deab264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.du Fossé NA, van der Hoorn M-LP, de Koning R, et al. Toward more accurate prediction of future pregnancy outcome in couples with unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss: taking both partners into account. Fertil Steril 2022;117:144–52. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasmark Roepke E, Christiansen OB, Källén K, et al. Women with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss are a high-risk population for adverse obstetrical outcome: a retrospective cohort study. J Clin Med 2021;10. 10.3390/jcm10020179. [Epub ahead of print: 06 01 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ticconi C, Pietropolli A, Specchia M, et al. Pregnancy-Related complications in women with recurrent pregnancy loss: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Med 2020;9. 10.3390/jcm9092833. [Epub ahead of print: 01 09 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moons KGM, Wolff RF, Riley RD, et al. PROBAST: a tool to assess risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2019;170:W1–33. 10.7326/M18-1377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riley RD, Ensor J, Snell KIE, et al. Calculating the sample size required for developing a clinical prediction model. BMJ 2020;368:m441. 10.1136/bmj.m441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.du Fossé NA, Lashley EELO, van Beelen E, et al. Identification of distinct seminal plasma cytokine profiles associated with male age and lifestyle characteristics in unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss. J Reprod Immunol 2021;147:103349. 10.1016/j.jri.2021.103349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sugiura-Ogasawara M, Ozaki Y, Kitaori T, et al. Live birth rate according to maternal age and previous number of recurrent miscarriages. Am J Reprod Immunol 2009;62:314–9. 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2009.00741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kling C, Magez J, Hedderich J, et al. Two-Year outcome after recurrent first trimester miscarriages: prognostic value of the past obstetric history. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2016;293:1113–23. 10.1007/s00404-015-4001-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.du Fossé NA, van der Hoorn M-LP, van Lith JMM, et al. Advanced paternal age is associated with an increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update 2020;26:650–69. 10.1093/humupd/dmaa010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.