Background:

Scarring that results in eyebrow loss is a cosmetic problem that can result in severe psychological distress. Although hair transplantation is increasingly used for eyebrow restoration, graft loss may occur, preventing achievement of desired results. Single-hair follicle transplantation, however, may be effective. The authors describe outcomes of a standardized method of eyebrow reconstruction, involving single-hair follicle transplantation combined with follicular unit extraction, in patients with absent eyebrows because of scarring.

Methods:

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Nanfang Hospital and all patients provided written informed consent before surgery. The medical records of patients who underwent eyebrow reconstruction from 2012 to 2019 for eyebrow loss caused by scar formation were reviewed retrospectively. Outcomes evaluated included satisfaction, graft survival rate, and long-term complications. A nine-step standardized operating procedure was established for eyebrow reconstruction in patients with eyebrow absence attributable to scarring.

Results:

During the study period, 167 patients (205 eyebrows) underwent eyebrow reconstruction. Following the first stage of reconstruction, 95 percent of patients were highly satisfied with the density and natural appearance of their eyebrows. The average graft survival rate was 85 percent (range, 70 to 90 percent), significantly higher than the 75 percent survival rate previously reported. Fewer than 5 percent of patients underwent the second stage of reconstruction, with these patients expressing satisfaction with their outcomes. No obvious complications were observed.

Conclusion:

This standardized method may optimize outcomes in patients with eyebrow absence attributable to scarring.

CLINICAL QUESTION/LEVEL OF EVIDENCE:

Therapeutic, IV.

Scarring-associated hair loss in eyebrows, usually caused by severe burns, trauma, tumor resection, local flap formation, or tattooing, has negative physical and psychological effects on patients. Absent eyebrows are usually restored by a superficial temporal artery island scalp flap, composite skin graft, and hair transplantation.1–6 Use of a superficial temporal artery island scalp flap has several drawbacks, in that the restored hair is denser and thicker than before scarring, having a brush-like appearance with sharp boundaries.7–9 In addition, these procedures require extensive dissection, which is complex and time-consuming. This method has therefore been recommended for the reconstruction of male, but not female, eyebrows.9,10 Furthermore, these methods often result in unfavorable outcomes, including scarring and new defects. Hair transplantation can overcome these drawbacks, possibly producing more natural eyebrows with optimal hair density and proper orientation, with methods based on follicular unit transplantation and follicular unit extraction techniques resulting in patient satisfaction. In contrast to follicular unit transplantation, follicular unit extraction involves the direct extraction from donor sites of hair grafts that match the color and diameter of the original eyebrow, without scarring. Although combination of follicular unit extraction and prosthesis implantation in a patient with eyebrow and orbital defects attributable to burst injury resulted in patient satisfaction, the study lacked long-term follow-up data.11 In addition, leg hairs obtained by follicular unit extraction have been used to thicken the density of sparse eyebrows.12 We have assessed the ability of hair grafts extracted from the hairline or frontal-temporal triangle and divided into single-hair grafts to restore eyebrows in patients with partially lost or sparse eyebrows.13 We found that this method of eyebrow restoration achieved better results than follicular unit grafting, as determined by patient satisfaction with survival rate and natural appearance.13

Eyebrow restoration, including attainment of ideal shape and appearance, is more difficult in patients with eyebrow absence attributable to scarring, owing to poor blood supply and stiffness. Moreover, the direction in which hairs must be transplanted changes frequently in different situations. Hair transplantation in these patients requires fully evaluating scar quality and balancing ideal eyebrow density and sufficient blood supply at recipient sites. We have focused on methods of restoring these scarred eyebrows to their original appearance and maximizing graft survival rate. Based on our experience, postoperative follow-up, and evaluation of its effect, we have developed a comprehensive standardized operating procedure for restoration of complete unilateral and bilateral eyebrow defects.

METHODS

Standardized Operating Procedure

Evaluation of Scar Properties

Subjective and objective evaluations of scar properties are essential before reconstruction. Subjective evaluations of scar quality include visual, sensory, and tactile assessments. Visual assessments include scar color, height, and surface appearance, whereas sensory assessments include itching and pain, which represent scar instability. In general, mature scars are pale, flat, soft, and nontender, whereas immature scars are red, stiff, itchy, painful, and at a level above surrounding tissue.14 Tactile assessments include pliability and elasticity, with good pliability regarded as smooth movements of scars in various directions and good elasticity as the scar being more than 50 percent of the height of surrounding healthy tissue.15 Objective evaluations include assessments of blood supply, performed by puncturing subcutaneous tissue with a needle and determining whether bleeding occurs. Two other objective methods are available to evaluate blood supply. The first, a trichoscopy device, which is portable and noninvasive, evaluates capillary structure through optic magnification and can also be used to distinguish hypertrophic scars from keloids.16 The other method is the capillary filling test.17,18 Scars suitable for hair implantation must be in a stable state with certain elasticity and pliability, as well as adequate vascularity to ensure graft survival.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients were included if (1) they had different degrees of eyebrow defects attributable to scar formation; (2) the scar was in a stable state, ideally with some subcutaneous tissue, and pliable; (3) there was no obvious infection or inflammation; and (4) the blood supply in the recipient bed was sufficient. Patients were excluded if (1) they had keloid scars; (2) the scars were close to or directly attached to bone; (3) donor hairs were tightly curled or of a thicker caliber than before scarring; (4) they had psychological abnormalities; (5) they were unable to accept regular eyebrow trimming; or (6) they had uncontrolled hypertension and/or hyperglycemia.

Donor Area Assessment and Management

Hair donor areas included the lower occipital hairline adjoining the neck, the posterior auricular hairline area, and the frontal-temporal triangle area, as hairs in these regions are soft and thin. Before surgery, hair caliber in the original eyebrow and in these three candidate donor areas was measured by trichoscopy, and the area with hair diameter closest to that of the original eyebrow was selected. If the hairs in all three areas were of similar diameter, the lower occipital and posterior auricular hairlines were preferred to the frontal-temporal triangle area. If the entire eyebrow had been lost, the area with hair diameter of 0.04 to 0.08 mm was chosen. Donor hairs were trimmed to a length of 3 to 5 mm before grafting to obtain a better immediate postoperative effect and estimate the long-term postoperative effect.

Graft Preparation

Hair grafts were harvested through the follicular unit extraction technique with a 1.5 or 2.5 loupe that minimized transection. Follicular unit extraction hollow needles with an outer diameter of 1.0 mm were recommended for unskilled physicians, whereas needles of 0.8 mm and 0.9 mm diameter were recommended for experienced physicians. These needles were able to extract hair grafts in the direction of hair growth at a speed of 3500 to 4000 rpm. Thinner grafts consisting of follicles containing one or two hairs were selected, with the number of hairs harvested being dependent on the hair density of the original area or the shape of the redesigned area.

Hair Follicle Preservation and Refinement

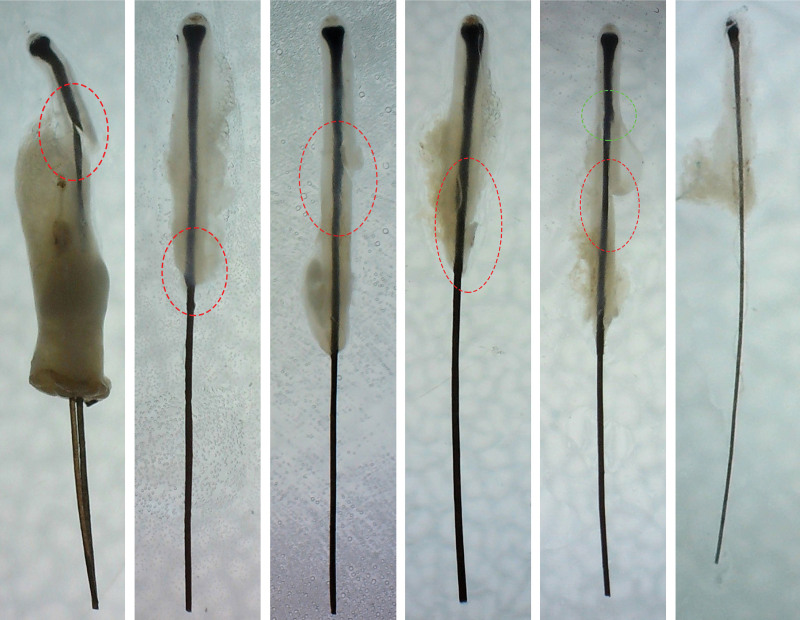

The harvested hair grafts were stored immediately at 0 to 4ºC in Ringer solution for no more than 2 hours. Storage in platelet-rich plasma or serum may also help preserve hair cells and avoid ischemia–reperfusion injury after implantation. The grafts were placed on a tongue depressor and dissected into single hair follicles (Fig. 1) using a surgical knife with a number 11 round blade parallel to the hair shaft to avoid follicular transection. These procedures were performed under stereomicroscope. Any superfluous epithelium or subcutaneous fat was removed. Grafts were divided into three types: vellus hair, thin hair, and mediate hair (Fig. 1). In addition, damaged hair follicles, including those with partial or complete shaft transaction, were discarded, as were grafts with an impaired hair bulb or bulge region (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Hair grafts and hair follicular units were divided into single hair follicles and classified into three types: mediate hair (above), thin hair (center), and vellus hair (below).

Fig. 2.

Grafts needing to be discarded included (from left to right) ones with (left) graft transection, (second image) damaged bulge area, (third and fourth images) dermal sheath damage, (fifth image) crush injury of hair follicle (green) or dermal sheath damage (red), or (right) hair in poor quality.

Eyebrow Design

In patients with unilateral eyebrow defects, the reconstructed eyebrow was shaped similar to that of the contralateral intact eyebrow (Figs. 3 and 4). Some patients with a sparse or unsatisfactory contralateral eyebrow also required an increase in hair density and an adjustment of eyebrow shape (Figs. 3 and 4). In patients with bilateral eyebrow defects, reconstruction of new eyebrows had to consider the facial symmetry of each individual (Figs. 5 and 6). In men, eyebrows are generally uniform and flat and are designated sword eyebrows. Arches are higher in women than in men. Generally, the widths of eyebrow peaks are approximately 1 cm in men and 0.8 cm in women, and the lengths and widths of eyebrows are 5.5 cm and 0.8 cm, respectively, in men and 5 cm and 0.6 cm, respectively, in women. Most eyebrow shapes in the current study were designed to be similar to the Anastasia style.19 Previous studies have also noted that Anastasia was the most preferred shape among patients of different ages and occupations.20 The medial end extended vertically through the nostrils, the arch was on a line drawn from the center of the nose through the center of the pupil, and the line between the lateral end of the eyebrow and the edge of the corresponding nasal ala ran through the lateral canthus (Figs. 7 and 8). The distance from the midpupil to the top of the eyebrow was 2 to 2.5 cm. Although the head, tail, and peak position of the eyebrow were designed based on these parameters and reference lines, these measures and lines were not fixed and were adjusted based on personal preferences and face shape. Five basic eyebrow shapes have been identified, including curved, sharp angled, soft angled, rounded, and flat eyebrows.21 In general, sharp angled eyebrows are preferred for individuals with round faces, rounded eyebrows for people with heart-shaped faces, and flat eyebrows for individuals with long faces. All eyebrow shapes are suitable for people with an oval face. The designed eyebrow outline was marked on the patient’s face using methylene blue.

Fig. 3.

Outcomes in a 22-year-old man with partial right eyebrow loss attributable to skin grafting following tumor excision 2 years earlier (left). The right eyebrow was restored with 237 single-hair follicles. To ensure consistent appearance of both eyebrows, 169 single-hair follicles were implanted into his left eyebrow. Six months later (right), the reconstructed eyebrow presented a bionic appearance.

Fig. 4.

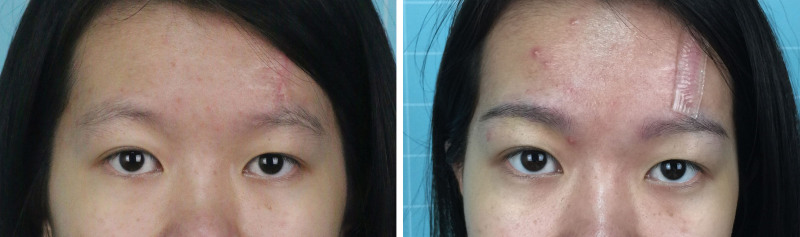

Outcomes in a 20-year-old woman with partial left eyebrow loss attributable to trauma from a car accident 3 months earlier (left). Her left eyebrow was restored with 192 single-hair follicles. To ensure consistent appearance of both eyebrows, 167 single-hair follicles were implanted into her right eyebrow. Seven months later (right), the reconstructed eyebrows had a satisfactory survival rate and a bionic appearance.

Fig. 5.

Outcomes in a 39-year-old woman who lost both eyebrows as a result of total brow resection 2 months earlier (left). Her eyebrows were restored with 215 single-hair grafts on the right side and 230 single-hair grafts on the left side. Seven months later (right), her reconstructed eyebrows presented a bionic appearance.

Fig. 6.

Outcomes in a 19-year-old man who sustained a facial burn 17 years earlier and underwent skin grafting 1 year earlier, resulting in bilateral eyebrow loss. His eyebrows were restored with 215 single-hair follicles on the right side and 203 single-hair follicles on the left side. After 23 months (right), only one stage showed satisfactory density and a natural appearance.

Fig. 7.

The eyebrow design method for women. The reconstructed eyebrow was 0.6 cm in width, 5.0 cm in length, and 0.8 cm in peak width. The distance from the center of the pupil to the top of the eyebrow was 2.5 cm, with the black axes determining the locations of the head, tail, and arch. Eyebrow shapes vary in women, with the flat shape being the most preferred; moreover, arches are higher and peaks slightly lower in women than in men.

Fig. 8.

The eyebrow design method for men. The reconstructed eyebrow was 0.8 cm in width, 5.5 cm in length, and 1.0 cm in peak width. The distance from the center of the pupil to the top of the eyebrow was 2.5 cm, with the black axes determining the locations of the head, tail, and arch. Sword-shaped eyebrows were always designed for men.

Recipient Site Anesthesia

Patients were shifted from the prone to the supine position and their faces were washed three times with chlorhexidine. The recipient site was anesthetized locally by slowly injecting a solution containing 2% lidocaine and 0.1% epinephrine subcutaneously into the superficial dermis using a 1 ml syringe and 32-gauge needle. Higher concentrations of epinephrine were administered as necessary to reduce intraoperative bleeding and avoid bruising. After injection, proper pressure and an ice compress were applied for 5 minutes to promote infiltration of anesthetic. Each injected area was no more than 1.5 ml in volume.

Graft Implantation

Holes were made in the marked area by punching with a 23-gauge needle at an angle of 5 to 10 degrees, depending on the direction of original hair growth. Other protocols were used in specific patients, as follows. (1) Because the bed in patients with stiff scars is characterized by tight adhesion of skin and muscle, making the recipient area brittle and easy to spilt, the microholes should not be too dense. These patients may therefore require two or more sessions to restore desired eyebrow density, and the angle between the needle and skin may require adjustment to ~10 to 20 degrees. (2) Because beds in patients who previously underwent flap transplantation are characterized by thicker subcutaneous fat, reduced tension, and a loose base, it has been recommended that the grafts be inserted at a smaller angle than in normal tissues. Because grafts tend to spread around and appear to have a low density after implantation, the density and orientation may require adjustment 6 months after the operation. (3) The presence of extensive adhesion scars in the superciliary arch area may result in a need to move the upper eyelid upward to the original eyebrow position. If the bed is characterized by thin skin with less subcutaneous fat, eyebrow restoration might require graft insertion at a small angle to the skin near flat. In addition, contracture deformities such as eyelid ectropion should be released before hair transplantation.

In general, hair grows in different directions. The head and lower part of the eyebrows were restored by inserting grafts in the superolateral direction, whereas the tail and upper part of the eyebrows were restored by inserting grafts in the inferolateral direction. Holes were punched to a depth of about 4 to 5 mm, followed immediately by placement in the hole of a hair in the same direction as the extracted needle. Hairs at the margins were implanted first, followed by filling of the area with the grafts and adjustment of their density. The medial area was restored with smaller caliber and lighter-color hairs, whereas the middle-lateral area was restored with wider caliber hairs to assure that they looked denser. Uniform density and symmetry were optimized relative to the untreated side. [See Video (online), which demonstrates the eyebrow reconstruction procedure presented in this study.] Following surgery, patients assessed their postoperative appearance and reported whether they were satisfied with their new eyebrows and whether they required adjustment.

Video. This video demonstrates the eyebrow reconstruction procedure presented in this study.

Postoperative Care

The recipient site was left open and coated with antibiotic ointment such as chlortetracycline or mupirocin twice daily for 5 days, protecting the transplanted hairs from friction. Patients were allowed to wash their faces as usual after 2 postoperative days, with washing of the recipient area following the direction of eyebrow flow. To avoid tissue swelling, ice compresses could be applied for 3 to 5 days. Patients were re-examined 7 to 10 days after surgery. Hair length was maintained by trimming at 5- to 7-day intervals. Graft survival rates were measured after 6 months.

Outcomes Measures

Postoperative complications were recorded at 7 days. The number of implanted grafts and the number of surviving grafts after 6 months were counted and the average graft survival rate was calculated. Because FACE-Q was considered a valid method for assessing patient satisfaction with facial aesthetic procedures,22,23 we assessed patient satisfaction using a questionnaire based on the original FACE-Q (Table 1). Procedure-specific sections were added, except for the generic part. Patients were asked to complete questionnaires at 6 months postoperatively. To increase the objectivity of the evaluation, three evaluators (a dermatologist, a plastic surgeon, and a nurse) compared photographs taken preoperatively and 6 months after the operation. Observers and patients rated items on a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 to 10, with 0 representing high dissatisfaction with the outcome and 10 representing high satisfaction with the outcome.

Table 1.

Modified FACE-Q Questionnaire for the Outcome Satisfaction Evaluation

| Questionnaire Items | Answers (score based on VAS) |

|---|---|

| Patient assessments | |

| Satisfaction with appearance (natural, covers the scar) | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Satisfaction with density | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Satisfaction with shape | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Satisfaction with symmetry | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Satisfaction with decision | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Social function | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Psychological well-being | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Early life impact | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Observer assessments | |

| Satisfaction with all the appearance (overall evaluation based on preoperative and 6-month postoperative photographs) | |

| Observer 1 | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Observer 2 | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

| Observer 3 | 0 (very dissatisfied) to 10 (very satisfied) |

RESULTS

From 2012 to 2019, 167 patients with eyebrow defects were admitted to Nan Fang Hospital. These patients included 99 women and 68 men (mean age, 26.43 years; range, 16 to 42 years). Eyebrow defects resulted from scalding burns in 62 patients, trauma in 87, local flap transfer in 12, and skin grafting in six. Sixty-seven patients underwent partial eyebrow reconstruction, 62 underwent unilateral eyebrow reconstruction, and 38 underwent bilateral eyebrow reconstruction (Table 2). Donor sites included the lower occipital area in 90 percent, the posterior auricular area in 10 percent, and the frontal-temporal triangle area in 10 percent. An average of 600 single hair follicles was required for complete eyebrow reconstruction, and the amount was lower in women than in men. The duration of surgery was 2 to 4 hours.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Characteristics | Values (n = 167) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 68 |

| Female | 99 |

| Age, yrs, mean (range) | 26.43 (16–42) |

| Eyebrow defect | |

| Unilateral | 62 |

| Bilateral | 38 |

| Partial | 67 |

| Cause | |

| Burn and scald | 62 |

| Trauma | 87 |

| Skin grafting | 6 |

| Local flap | 12 |

Donor and recipient areas of all patients were well healed, with none having pigmentation around the grafted hairs. Of these 167 patients, 159 were highly satisfied, seven were satisfied, and one was dissatisfied, with none being highly dissatisfied. The mean graft survival rate at recipient sites was 85 percent (range, 70 to 90 percent). Eight patients required a second operation to increase hair density, such that the new eyebrow completely camouflaged the scar. No patient developed hematoma, infection, folliculitis, hemorrhage, or any other complication (Table 3).

Table 3.

Standardized Operating Procedure Measurement

| Measurements | Values (n = 167) |

|---|---|

| Survival rate, %, mean (range) | 85 (70–90) |

| Satisfaction level | |

| High satisfaction | 159 |

| Satisfaction | 7 |

| Dissatisfaction | 1 |

| High dissatisfaction | 0 |

| Complications | |

| Hematoma | 0 |

| Infection | 0 |

| Hemorrhage | 0 |

| Folliculitis | 0 |

| Pigmentation | 0 |

| Underwent encryption | 8 |

DISCUSSION

The eyebrows are a very significant aesthetic feature of the face and are involved in facial expressions. Appropriate eyebrow shape and density are particularly important for facial appearance. Because previous outcomes have not always been satisfactory, with low survival rates and unnatural appearances, transplantation is increasingly used in eyebrow restoration. The current study describes comprehensive operating procedures based on the authors’ experience, improved technology, and surgical skills to achieve good outcomes. This standardized operating procedure resulted in naturally appearing eyebrows with a relatively high survival rate. Graft survival rates were satisfactory even in patients who experienced complete hair loss after 2 years. The average graft survival rate among patients was 85 percent—higher than the average 78 percent survival rate in patients with traumatic scars.24 Jung et al.1 reported that the survival rate of grafts that did not completely cover scars was less than 60 percent. The grafts in the current study completely covered previous scars.

Several novel aspects of this procedure may improve graft survival rates and help obtain natural appearance. First, the indications for this method are strictly controlled and scar quality is well assessed. Before implementation of this procedure, careful evaluation of scar stability and vascularity were important to enhance graft survival rate. Subjective measurements of stability have shown moderate to high correlations with objective methods.25–29 Because successful hair transplantation requires reestablishment of the microcirculation, methods are needed to evaluate blood perfusion accurately in the scar area. Morphologic imaging is a precise and objective method that can evaluate the formation of new blood vessels and further determine blood flow perfusion. However, morphologic imaging equipment is expensive.30 Therefore, the current study used three feasible and objective methods. Second, selection of the optimal donor site is crucial in making the reconstructed eyebrow appear more natural. Using trichoscopy, we chose an eyebrow shape closest in diameter to the original eyebrow. Third, hair direction and density should be adjusted when reconstructing eyebrows in several special situations. Moreover, single hair grafts are smaller and have lower metabolic requirements for survival than grafts containing two or three hairs, consistent with original eyebrows composed of a single hair per follicle unit. Finally, the method used to harvest hair follicles has been adjusted, from follicular unit transplantation to follicular unit extraction, resulting in no scarring in the donor area and fewer complications. This procedure has minimal surgical risk and a rapid effect, allowing patients to recover quickly, usually in 2 to 4 days. In addition, the follicular unit extraction technique has made the donor area unrestricted, allowing grafts to be taken from any site in the body, such as the head, beard, and legs.12,31,32

This procedure is not suitable for all eyebrows lost to scarring. These eyebrows may first require another treatment to create a good bed for implantation. [See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows a flowchart for reconstruction of individual scarred eyebrow based on scar quality, location, and type, http://links.lww.com/PRS/F388.] The scars resulting from eyebrow loss can be categorized as superficial, hypertrophic, atrophic, and keloid. Superficial scars are soft, with hair transplantation being as easy as in normal tissues. The tissue beds of hypertrophic and keloid scars are stiff and not on the same level as the surrounding skin, resulting in hair grafts at different depths and difficult insertion. Hypertrophic scars can be treated with corticosteroids to reduce inflammation and suppress hyperplasia,33 allowing hairs to be implanted when these scars soften. Keloid scars grow beyond the boundary of the previous wound and may require locally enlarged resection, resulting in a tissue bed insufficient for transplantation. None of the patients in the current study had hypertrophic or keloid scars on their eyebrows. Moreover, a study of 295 patients who underwent 414 thin scalp transplantations over 10 years found that none developed hypertrophic or keloid scars,34 indicating that pathologic scars rarely occur in the scalp or brow area. For atrophic scars, grafts should be inserted at an acute or near flat angle because the bed is very shallow. For hard scars, glucocorticoid or injection of autologous fat grafts can soften tissue. Autologous fat grafts consist primarily of adipose-derived stromal cells and stromal vascular fraction gel, which can minimize scar size and increase the quality and pliability of scars.35–42 Adipose stromal cells have been found to enhance skin neovascularization,43 allowing easy graft insertion and improving graft growth environments. Subcutaneous fat transplantation can also promote the regeneration of hair follicles in scarred areas, as good results were obtained when autologous fat grafts were used to treat atrophic scarring alopecia in eyebrows.41 Therefore, fat transplantation along with this standardized procedure is an alternative two-stage treatment for patients with stiff scars. Except for the abovementioned situations, scars that are relatively brittle or in the eyebrow arch may require more than two sessions to achieve a satisfactory density.

CONCLUSIONS

Because of the importance of eyebrows for facial aesthetics, it is necessary to restore cicatricial eyebrow loss. The method described in the current study is safe and practical for natural eyebrow reconstruction, with a high graft survival rate and ability to camouflage previous scars. Patients expressed high levels of postoperative satisfaction, even after a single session. This method is likely to be useful in the reconstruction of scarred eyebrows.

PATIENT CONSENT

Patients provided written informed consent for the use of their images.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

Related digital media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSJournal.com.

A Video Discussion by Sanusi Umar, M.D., accompanies this article. Go to PRSJournal.com and click on “Video Discussions” in the “Digital Media” tab to watch.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article. No funding was received for this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jung S, Oh SJ, Hoon Koh S. Hair follicle transplantation on scar tissue. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1239–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose P. The latest innovations in hair transplantation. Facial Plast Surg. 2011;27:366–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Fan J. Cicatricial eyebrow reconstruction with a dense-packing one- to two-hair grafting technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:1420–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mantero R, Rossi F. Reconstruction of hemi-eyebrow with a temporoparietal flap. Int Surg. 1974;59:369–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klingbeil KD, Fertig R. Eyebrow and eyelash hair transplantation: A systematic review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:21–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ergün SS, Sahinoğlu K. Eyebrow transplantation. Ann Plast Surg. 2003;51:584–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toscani M, Fioramonti P, Ciotti M, et al. Single follicular unit hair transplantation to restore eyebrows. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1153–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laorwong K, Pathomvanich D, Bunagan K. Eyebrow transplantation in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:496–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridgway EB, Pribaz JJ. The reconstruction of male hair-bearing facial regions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juri J. Eyebrow reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:1225–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karayazgan-Saracoglu B, Ozdemir A. Fabrication of an orbital prosthesis combined with eyebrow transplantation. J Craniofac Surg. 2017;28:479–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umar S. Use of body hair and beard hair in hair restoration. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:469–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miao Y, Fan ZX, Hu ZQ, Jiang JD. Single hair grafts of the hairline to aesthetically restore eyebrows by follicular unit extraction in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:1300–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poetschke J, Gauglitz GG. Current options for the treatment of pathological scarring. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016;14:467–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong SH, Koo SH, Han SK, Kim WK. An algorithmic approach for reconstruction of burn alopecia. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65:330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo MG, Kim IH. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: Characteristic vascular structures visualized by using dermoscopy. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26:603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Carnazzo AJ, Copes W, Fouty WJ. Trauma score. Crit Care Med. 1981;9:672–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Hannan DS, et al. Assessment of injury severity: The triage index. Crit Care Med. 1980;8:201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anastasia SA. Anastasia Beverly Hills, 1997. Available at: http://www.anastasia.net. Accessed December 31, 2013.

- 20.Kim SK, Cha SH, Hwang K, et al. Brow archetype preferred by Korean women. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:1207–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alex JC. Aesthetic considerations in the elevation of the eyebrow. Facial Plast Surg. 2004;20:193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klassen A, Cano S, Scott A, et al. Measuring patient-reported outcomes in facial aesthetic patients: Development of the FACE-Q. Facial Plast Surg. 2010;26:303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klassen AF, Cano SJ, Schwitzer JA, Scott AM, Pusic AL. FACE-Q scales for health-related quality of life, early life impact, satisfaction with outcomes, and decision to have treatment: Development and validation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shao H, Hang H, Yunyun J, et al. Follicular unit transplantation for the treatment of secondary cicatricial alopecia. Plast Surg. 2014;22:249–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lye I, Edgar DW, Wood FM, Carroll S. Tissue tonometry is a simple, objective measure for pliability of burn scar: Is it reliable? J Burn Care Res. 2006;27:82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nedelec B, Correa JA, Rachelska G, Armour A, LaSalle L. Quantitative measurement of hypertrophic scar: Intrarater reliability, sensitivity, and specificity. J Burn Care Res. 2008;29:489–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Draaijers LJ, Tempelman FR, Botman YA, Kreis RW, Middelkoop E, van Zuijlen PP. Colour evaluation in scars: Tristimulus colorimeter, narrow-band simple reflectance meter or subjective evaluation? Burns 2004;30:103–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lau JC, Li-Tsang CW, Zheng YP. Application of tissue ultrasound palpation system (TUPS) in objective scar evaluation. Burns 2005;31:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloemen MC, van Gerven MS, van der Wal MB, Verhaegen PD, Middelkoop E. An objective device for measuring surface roughness of skin and scars. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:706–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deng H, Li-Tsang CWP. Measurement of vascularity in the scar: A systematic review. Burns 2019;45:1253–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umar S. Use of beard hair as a donor source to camouflage the linear scars of follicular unit hair transplant. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:1279–1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umar S. Eyebrow transplantation: Alternative body sites as a donor source. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:e140–e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogawa R. Keloid and hypertrophic scars are the result of chronic inflammation in the reticular dermis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farina JA, Jr, Freitas FAS, Ungarelli LF, et al. Absence of pathological scarring in the donor site of the scalp in burns: An analysis of 295 cases. Burns 2010;36:883–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brongo S, Nicoletti GF, La Padula S, Mele CM, D’Andrea F. Use of lipofilling for the treatment of severe burn outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:374e–376e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coleman SR. Structural fat grafts: The ideal filler? Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:111–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho SB, Roh MR, Chung KY. Recovery of scleroderma-induced atrophic alopecia by autologous fat transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:2061–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Liao Y, Xia J, et al. Mechanical micronization of lipoaspirates for the treatment of hypertrophic scars. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mojallal A, Lequeux C, Shipkov C, et al. Improvement of skin quality after fat grafting: Clinical observation and an animal study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:765–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klinger M, Marazzi M, Vigo D, Torre M. Fat injection for cases of severe burn outcomes: A new perspective of scar remodeling and reduction. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32:465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dini M, Mori A, Quattrini Li A. Eyebrow regrowth in patient with atrophic scarring alopecia treated with an autologous fat graft. Dermatologic Surg. 2014;40:926–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akdag O, Evin N, Karamese M, Tosun Z. Camouflaging cleft lip scar using follicular unit extraction hair transplantation combined with autologous fat grafting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:148–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheng L, Yang M, Li H, Du Z, Yang Y, Li Q. Transplantation of adipose stromal cells promotes neovascularization of random skin flaps. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2011;224:229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.