Abstract

Disability is an important facet of diversity. Although diversity in clinical training in health service psychology has improved considerably, training often neglects accessibility and inclusion for individuals with sensory disabilities. The limited research to date documents that trainees with sensory disabilities (TSD) report extensive barriers and are consistently under-represented in clinical settings. Further, few resources have been developed to guide accommodating TSD in clinical training. Accordingly, our goals in this article are two-fold: (1) to highlight the barriers in clinical training faced by TSD and (2) to provide recommendations for trainees, supervisors, clinical leadership, and directors of clinical training to improve accessibility and inclusion for TSD. We offer vignettes to illustrate barriers faced by TSD and suggest guidelines to improve access for TSD.

Keywords: disability, trainees with disabilities, clinical training, professional practice, sensory disabilities

Guidelines to Address Barriers in Clinical Training for Trainees with Sensory Disabilities

Disability is often overlooked in discussions about diversity (Andrews, 2019). Yet, people with disabilities comprise one of the largest minority groups in the country and, according to the U.S. Census, constitute approximately 18.7% of the civilian non-institutionalized population (Brault, 2012). Sensory disabilities, defined as significant sensory impairments, including blindness/low vision and identifying as Deaf/deaf or hard of hearing, present with unique challenges to access. About 2.3% of the US population reports a visual disability and 3.6% report a hearing disability (Kraus, 2017, p. 11). Available estimates suggest <1% of psychology doctoral students report being blind/visually-impaired or deaf/hard of hearing (Andrews & Lund, 2015; Omitted, In Press), suggesting significant underrepresentation in health service psychology (HSP; i.e. professionals from clinical, counselling, and school psychology programs). This underrepresentation exists despite comparable quantitative credentials (e.g. GPA); moreover, graduate students with disabilities experience higher attrition rates than those without a disability (Callahan et al., 2018). Although other dimensions of diversity (e.g. race and sexual orientation) have shown increasing representation in HSP, disability representation has actually decreased (Andrews & Lund, 2015). As global rates of disability increase (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019) and rates of psychology students with disabilities increase (American Psychological Association Report, 2009), it is critical for HSP training programs to adequately accommodate the training needs of all trainees in order to help build the necessary workforce, particularly given the need for psychology professionals is expected to grow 14% by 2028 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019).

Because disability encompasses a wide and heterogeneous set of experiences, this paper limits its focus to trainees with sensory disabilities (TSD). Although physical (i.e. motor), cognitive, and psychiatric disabilities are important areas of emphasis, these are beyond the scope of this paper and are characterized by different needs and experiences in training settings (Hauser et al., 2000b; Joshi, 2006; Wilbur et al., 2019). Our focus on TSD is especially important given data suggesting sensory disability is among the most underrepresented disabilities in psychology (Andrews & Lund, 2015).

The American Psychological Association’s Strategic Plan (APA; American Psychological Association, 2019) prioritizes diversity and inclusion and disability issues are upheld with other inclusion initiatives. Like other areas of diversity, disability identity is tied to a unique culture that warrants similar cultural sensitivity and humility (Andrews et al., 2013); however integrating disability into such initiatives has been slow (Olkin & Pledger, 2003). highlighting the need for increased inclusion on disability issues in HSP. APA has created general resources for steps to improve inclusion for trainees with disabilities, such as a guide for graduate students (American Psychological Association, 2008); American Psychological Association, 2009), guidelines for reasonable accommodations in assessment (American Psychological Association, 2011), and a mentorship program (American Psychological Association, 2008). These resources, however, tend to be overly broad and may not be adequately tailored to TSD.

One area where few guidelines exist is on the clinical training needs of TSD (Andrews et al., 2013;Wilbur et al., 2019). Barriers to training opportunities encountered by TSD include stigma, bias, and discrimination; lack of education and awareness by program faculty and supervisors, and lack of accessibility and inadequate provision of accommodations by clinical leadership and institutions (American Psychological Association, 2009; Hauser et al., 2000; Joshi, 2006; Lund et al., 2016, 2019). In addition to research and coursework requirements, HSP students are required to gain competency in clinical training, including clinical interviewing, diagnostics, assessment, and treatment. Assessment training may pose particular barriers to TSD, including the need to follow standardized testing protocols, inaccessible computer-based scoring and administration software packages, challenges with the physical testing environment, and a lack of adaptive equipment at various practicum locations. What programs may not know is that many of the barriers faced by TSD are surmountable but require modification, or accommodation, along with close collaboration between the trainee, supervisors, and program faculty..

Practica/internships, required for HSP trainees, often lack access, accommodations and support (Lund, Andrews, et al., 2020b). Surveying 120 practica/internship sites in the greater San Francisco Bay Area Olkin (2002) found that, among the responding sites (46%), more than 50% involved travel to less accessible secondary sites; only 16% had Braille signage; 38% had emergency alarms with both visible and audible warnings; and 78% provided no TTD [Telecommunication Device for the Deaf]. Disparities are noted in internship match rates: trainees without a disability have a match rate of 81%, whereas the match rate for blind/visually impaired trainees is 67% and for deaf/hard of hearing trainees is 75% (Andrews et al., 2013).

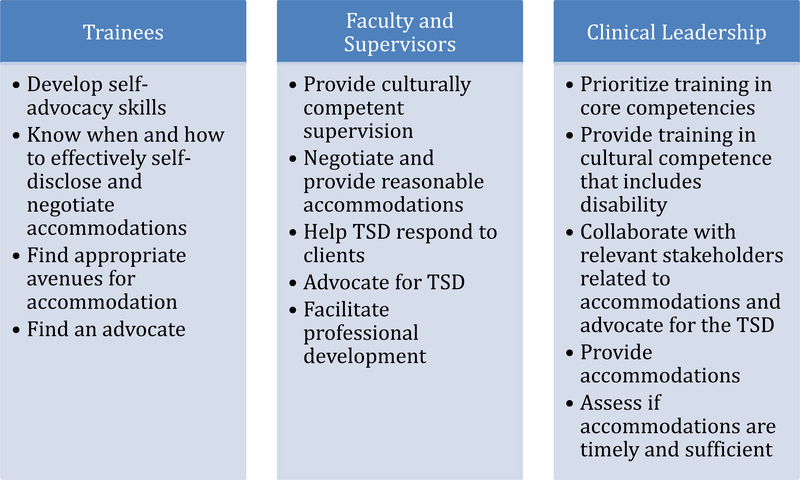

The goal of our paper is to highlight barriers in clinical training faced by TSD and recommend guidelines for achievable means to increase access and inclusion to support TSD. We begin by offering a series of vignettes to illustrate how relevant stakeholders - trainees, program faculty and supervisors, and clinical leadership – contribute to access and inclusion for TSD in clinical training. We then provide recommendations across levels and relevant stakeholders by applying the framework of training in cultural competency and sensitivity to the topic of disability (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Guidelines to mitigate barriers faced by TSD.

Case Examples

Below we offer sample interactions to highlight common diverse ways in which sensory disability is handled in clinical training.

Case Example #1: Frank

Frank is a TSD identifying as deaf. He can read the lips of close friends and family; however, he relies on a sign language interpreter in professional contexts. Frank worked with his clinic leadership and received a sign language interpreter for all sessions when a student clinician in his graduate training clinic. As an advanced trainee, Frank pursued an external practicum. Frank did not disclose details about his disability or accommodation needs during the application process based on prior experiences of discrimination. Instead, he focused on his qualifications and fit. Frank was interviewed by phone and was able to use assistive technology (i.e. TTY) to communicate with his interviewer. Once offered a position, Frank disclosed that he needed a sign language interpreter due to his hearing disability.

Frank made his initial accommodation requests to his supervisor at the external practicum training site. His supervisor appeared annoyed, expressing her belief it was not the responsibility of the site to pay for a sign language interpreter. Frank met with his director of clinical training, who indicated it was not their responsibility to provide accommodations for an external site. Frank then contacted multiple offices at his practicum site, including human resources. Because Frank was not a hired employee, the external practicum site encouraged Frank to find his own interpreter. Frank was able to find a volunteer to provide signed interpretation for his clinical work; however, the practicum director expressed concern over the confidentiality of protected health information with the volunteer (i.e. unpaid and informal), stating “Not just any interpreter will do.” After months of discussion with the site, Frank could not negotiate reasonable accommodations and sought an experience at an alternate training site. Because there was a lengthy delay during the accommodation negotiation process, only one site still had availability. Even though the opportunities at this site were not aligned with his long-term goals, Frank needed a site willing and able to provide an interpreter. At the end of this practicum, Frank had far fewer clinical hours and experiences than his peers.

Commentary on Case Example #1: Frank

Trainees like Frank are often forced to compromise their training goals based on accessibility. There are multiple barriers that could have been addressed by Frank, his supervisor, or the program’s clinical leadership in order to facilitate more equitable access to training. First, Frank could have chosen to disclose his disability in his applications. It is possible he would have received fewer offers; however, it is also possible that Frank would only then choose from sites that could provide the necessary accommodations, resulting in accumulating a greater number of clinical hours and experiences before applying to internship. Second, Frank legally deserved accommodations, however his lack of power led to the dismissal of his needs. Others with relatively more power, such as his supervisor or training director, could have intervened to advocate for Frank. Leadership from his home institution could also have intervened and advocated on Frank’s behalf with the practicum site or the university’s student disabilities services office. His program director could have explained to the practicum site how they navigated confidentiality with signed interpretation services. Third, an approved plan could have been developed by Frank and his supervisor in collaboration with human resources at the practicum site with input from Frank’s DCT to ensure they understood the rules and regulations around signed interpretation services. Frank expended time and effort securing a volunteer interpreter that was ultimately deemed unsuitable, and this could have been avoided by having the institution take a more collaborative approach to problem-solving. This case illustrates the multiple pathways by which suitable accommodations and modifications could be accomplished, but also highlights the need for close (and willing) collaboration between students, their training programs, universities, and practicum sites and underscores the need for training directors to advocate for their students.

Case Example #2: Sofia

Sofia is a TSD experiencing low vision. Her impairment is sometimes visible because she uses a white identification cane, but most of the time Sofia navigates public spaces without visible assistive technology. During her initial coursework in psychological assessment, Sofia was able to master the essential skills by using a combination of large-print materials and technology such as video recording to help her keep track of responses and make additional behavioral observations following testing. When assigned an assessment case, Sofia discovered it would not be feasible for her to administer the required neuropsychological tests due to changes in her vision and the lack of access to video recording technology. Further, Sofia had difficulty adapting testing material to be accessible while maintaining standardization and sought guidance on how to accommodate the assessment process.

Sofia communicated to her supervisor that she would be unable to administer the required testing materials. The supervisor was unsure how to proceed and contacted the clinical director. The clinical director, Sofia, and her supervisor discussed potential options. The clinical director reviewed the core competencies of assessment training and determined that the most important experiences for the trainee were to interpret the results of testing and write integrated reports. Therefore, a fellow graduate student who was also training at the practicum site was brought in to serve as an assistant for assessments Sofia was unable to administer and score herself. This solution enabled Sofia to complete her assessment, albeit with considerable limitations that presented her with logistical, professional, and personal challenges. For example, scheduling became a major obstacle. The fellow graduate student often complained to Sofia of “not having any time,” which made Sofia feel guilty for making additional requests for assistance with scoring measures and created a sense of forced indebtedness to her peer.

Commentary on Case Example #2: Sofia

Sofia was vocal about her needs, which allowed for a discussion about accommodations and training goals early on. Although the use of a graduate student psychometrician was a feasible way for Sofia to complete assessment cases, it also was not ideal given the dual relationship; this accommodation come at the cost of her relationship with her peer. Further, although the arrangement represented a “stopgap” solution to the immediate situation, it ended up being a missed opportunity for feedback. If the supervisor or clinical director had known about the difficulties Sofia was experiencing, another solution may have been implemented. For example. Sofia’s supervisor, other program faculty, or another peer not directly involved in the practicum site but who had the requisite skills to administer the assessments may have administered the assessment battery in order to preserve the relationship dynamic between Sofia and her peer. As Sofia will need to continue gaining competency in psychological assessment, identifying the optimal accommodations early in her clinical training and continuing to problem-solve as her training progresses will afford Sofia with further training opportunities while minimizing stress once situations requiring accommodations arise. To this end, Sofia may have also consulted with the supervisor ahead of time to determine if certain accommodations to the testing materials could be made which would not break standardization but would preserve Sofia’s ability to participate in aspects of the assessment (e.g., having large print versions of verbal and working memory test protocols that Sofia could read to the examinee without changing test administration).

Case Example #3: Josie

Josie is blind and has no functional vision. Josie was excited to begin clinical training though nervous for how her disability would impact clinical work. Before beginning clinical training, Josie’s clinical director scheduled a meeting to discuss needs and accommodations. The clinical director stated that she has introductory meetings with all incoming students to discuss how student identities influence their clinical work and how the program can support each individual trainee’s needs.

During this initial meeting, Josie and her clinical director brainstormed the ways her disability may impact her clinical training. Josie raised that she was particularly concerned about self-disclosure with clients and how she would work with clients on shared materials, such as therapy homework. The training director and Josie collaboratively established a plan for self-disclosure, which included role-plays. They identified a potential solution for shared access to therapy materials; Josie would ask clients to read therapy homework aloud. The training director made a point to ask Josie every few months about if the accommodations provided were meeting her needs. During one of these meetings, Josie expressed feeling limited by only hearing her clients’ homework during sessions. Josie wondered if there was a way for her to access clients’ therapy materials after sessions for notetaking and treatment planning. The training director worked with Josie to identify a secure means of accessing her client’s materials with her Braille reader and a screen reader. This accommodation required a clinic staff member to scan materials, and the training director took responsibility for ensuring the provision of this accommodation given the relative position of power compared to Josie.

Commentary on Case Example #3: Josie

Because the clinical director asked all students about their individual needs, Josie did not feel as though she was a burden or different from her peers highlighting the advisability of such practices for ensuring accommodation and inclusion. The clinical director and Josie worked collaboratively, which made Josie feel as though she has the power to make direct requests to improve her training experience. The clinical director advocated on behalf of Josie to the clinic staff to ensure reasonable accommodations were in place to make her therapy work more accessible and continued to follow-up to ensure provided accommodations were adequate and refine any elements of the plan needing improvement. Although institutions vary based on their access to resources for accommodations, clinical leadership can continue to advocate for resources necessary for TSD. This example also exemplifies that many accommodations necessary for TSDs are relatively straightforward, but do require some flexibility, planning and problem solving, and a willingness to be creative and attentive to the needs of all trainees.

Summary of Case Examples

Although not exhaustive, these case examples shed light on some common barriers faced by TSD and training programs. Frank, Sofia, and Josie had differing levels of openness and support in the accommodation process. Frank encountered the diffusion of responsibility for providing reasonable accommodations that had consequences on his training. He was isolated, disempowered, and inevitably had to compromise his training experience due to lack of access. Josie benefitted tremendously from having the clinical director ask openly to all trainees about their individual needs, as this reduced her sense of internal shame and stigma. Her clinical director took the time to work with her to brainstorm solutions, which helped Josie feel valued. Josie and the training director regularly reviewed the status of her accommodations and needs, which enabled for iterative improvement. Sofia’s experience highlights how often trainees are unaware what accommodations they will need until beginning clinical training and the difficulties training programs sometimes encounter in identifying equitable solutions to difficulties encountered in clinical work by TSD. Although her clinical leadership was largely responsive to her needs, Sofia did not receive the same level of support and follow-up as was provided to Josie, nor did her program faculty consider how the longer-term negative impact of the identified solution. These examples highlight structural barriers including limited experience or guidelines for training programs; inaccessibility (for Frank and Sofia), stigma (for Frank and Sofia) and discrimination (for Frank); and aspects of the position of relative lack of power both as a trainee and as a student with a marginalized identity. These case examples also demonstrate ways in which trainees, program faculty and supervisors, and clinical leadership can improve access and inclusion for TSD.

Guidelines

We expand on these case examples by offering concrete guidelines for TSD, program faculty and supervisors, and clinical leadership. A summary of these guidelines are displayed in Figure 1.

Guidelines for Improvement: Trainees with sensory disabilities

The ADA prohibits employers from inquiring about disability status. Therefore, the TSD must self-identify and communicate their needs and be proactive in arranging accommodations (Donohue, 2015). In graduate training, however, seeking accommodations can present potential challenges given the roles of TSD throughout training, the need to weigh pros and cons and timing of self-disclosure, and navigating inherently hierarchical and evaluative relationships. Advocacy from training directors, mentors, and supervisors is necessary to overcome these barriers (Lund, Wilbur, et al., 2020). Below are strategies for TSD navigating disclosure or barriers to training opportunities.

Develop self-advocacy skills

Given ADA guidelines, self-advocacy requests are central to equitable access to accommodations (Lund et al., 2016, 2020). In a survey of doctoral HSP psychologists with disabilities, less than half had received formal accommodations and nearly one quarter only received informal accommodations (Lund et al., 2014). For TSD, self-advocacy involves discerning when, to whom, and how to disclose and advocate for disability-related needs. But there are risks: early disclosure can lead to blatant discrimination, including inappropriate interview questions and position denial (Andrews et al., 2013; Hauser et al., 2000a; Vande Kemp et al., 2003a). At the same time, disclosure and self-advocacy may be necessary and ethical (e.g., APA Ethics Code General Principle A, Sections 2.06, 3.04, and 7.04, (American Psychological Association, 2017) as many disabilities impact the completion of required courses, training, and the provision of clinical services. Moreover, disabilities also differ in their visibility and hence, need for disclosure. Invisible forms of sensory disabilities place the onus on the TSD to make decisions about self-disclosure (Davis, 2005). Yet, studies show additional challenges of those with these invisible forms, including suspicion, assumptions, denial of accommodations, and forgetfulness about disability (Lund et al., 2016; Lund, Andrews, et al., 2020a; Wilbur et al., 2019).

Negotiation and assertiveness skills are essential for TSD’s self-advocacy related to accommodation requests. Regardless of visibility, training leadership (i.e., program directors, faculty, supervisors) may still have limited knowledge about sensory disabilities and the burden may again fall to the TSD to educate others and assert needs (Lund et al., 2016, 2020). This may add another layer of difficulty, given the hierarchical and evaluative relationships of TSD and their program faculty, supervisors, and clinical leadership (Vande Kemp et al., 2003b). This may lead to few if any opportunities to voice concerns, build momentum towards change, and limit access to practical changes, such as providing appropriate accommodations (Lund et al., 2016). Developing self-advocacy skills can also help TSD partner with their training program and identify those who can advocate to ensure access to accommodations. TSD experiencing difficulties with assertiveness or who have limited experience requesting accommodations may benefit from consultation and support from specialized services at the institutional level. Self-advocacy is difficult for any trainee identifying as a minority, yet it is directly tied to clinical responsibilities, ethical competencies, and professionalism.

Find avenues for advocating for accommodations

Academic institutions often have a disabled students’ program which provides support services and reasonable accommodations to ensure equitable access to and benefits from educational experiences. They have been critical for improving access to educational opportunities for students with disabilities (Scott, 2010). Yet, these offices serve mostly undergraduate students and may be less familiar with graduate training needs (Lund, Andrews, et al., 2020b). They often provide necessary accommodations for accessing course content (e.g., assistive technology or note-takers), but may be less facile with clinical training for HSP (Lund, Andrews, et al., 2020b; Taube & Olkin, 2011). Thus, advocacy from program faculty, supervisors and clinical leadership is necessary for TSD accommodations. It may help for program advocates to emphasize that clinical and practica training are a required component of their degree program. Parallels may be drawn to other academic programs with a practice component, such as medicine, nursing, or law.

Similarly, accommodations may be required at clinical practica and internship sites. Although practicum sites, like hospitals, have human resources offices that provide disability-related accommodations, these are for employees. Practicum students may not be viewed as employees. Moreover, practicum sites often have byzantine organizational structures that should not be navigated by the TSD alone (Vande Kemp et al., 2003b). Beyond this, organizations view accommodations as too costly or burdensome, despite evidence to the contrary (Hernandez & McDonald, 2007). Therefore, for practica TSD should request guidance from their home institution, such as advocacy by a training director. For internship, training directors from both the home institution and internship site might collaborate. This is likely the most efficient and straightforward way towards advocating for required accommodations. If training directors face barriers, they might consult with a larger network of training directors to determine the best way to pursue advocacy efforts.

Know when and how to disclose and discuss with clients

It may at times, be necessary to disclose or discuss the TSD’s disability with clients. Although TSD may worry about the impact of disclosure on rapport, there are effective ways to communicate the possible impacts of their disability on clinical care that is judicious, appropriate in content and level of intimacy, and is catered to the client’s needs and preferences (Knox & Hill, 2003; Pearlstein & Soyster, 2019). When and how to disclose or discuss a disability depends on the effect that disability has on clinical care. A student with low vision may need to communicate to the client that they are unable to read standard print materials and will need the client to read responses to worksheets aloud. A student with hearing loss may need to explain the use of a signed interpreter and how principles of confidentiality still apply. Disclosure and discussion of disabilities is essential for explaining to the client its impact on clinical care, but the timing of disclosure should be considered. Early disclosure may provide clients with opportunities to express concerns, foster trust and intimacy during the earliest stage of a therapeutic relationship, and model open communication, but it may also lead to premature termination. Late disclosure could lead to an opportunity to build rapport but the later disclosure could also lead to a a rupture in that relationship. Regardless of when a trainee chooses to disclose, clinical judgment and effective communication still apply. For example, when a client is struggling with a new diagnosis and incorporating this into their self-concept, TSD may choose to express their own experience accepting their disability and subsequently finding meaning and identity. Ineffective self-disclosure, on the other hand, overfocuses on the clinician, detracting from the client’s experience and treatment goals, which clients may find invalidating (Andrews et al., 2013). TSD should seek out supervision to consult about appropriate disclosure and role-play effective disclosure. Because supervisors may lack experience working with therapists with disabilities and may hold biases that hinder open discussion, TSD may need to seek additional consultation outside of a primary supervisor.

Guidelines for Improvement: Program Faculty and Supervisors

Training programs may, at times, feel unequipped to address the needs of TSD (Wilbur et al., 2019). They may lack familiarity, education, prior training, open discussion, or prior experiences mentoring or supervising TSD. They may avoid conversations out of fear of using the wrong language. It may be helpful to view approaching needs of TSD as any other aspect of diversity and using principles of cultural humility. Below are guidelines for program faculty and supervisors to assess TSD clinical training needs, provide individualized supervision and training plans, including reasonable accommodations and guidance around disclosure and discussion of disabilities in clinical work, and facilitate the trainee’s development (e.g. establishment of an individual style and connection with mentors). In addition to guidelines offered below, we recommend the APA resources for enhancing interaction with people with disabilities (American Psychological Association, 2000) and advocacy on behalf of TSD to create a disability-affirmative training environment (Lund, Wilbur, et al., 2020).

Advocate for TSD

Advocacy by training leadership is essential. Program faculty and supervisors should take an active role early, often, and in an going manner to advocate for TSD and promoting disability-affirmative training environments in order to minimize barriers faced by TSD (Lund, Wilbur, et al., 2020). Program faculty and supervisors can serve as advocates by supporting TSD, arguing for reasonable accommodations and inclusive practices for TSD, and modeling and encouraging a strengths-based perspective and creative problem-solving (Lund, Wilbur, et al., 2020). Such advocacy efforts are likely to have long-standing impacts in improving the program overall and meeting the needs of future TSD in the program. It will also bolster effectiveness in working with clients, research participants, undergraduate students with sensory disabilities.

Provide culturally competent supervision

Supervisors of TSD can approach disability as an element of culturally competent supervision (Andrews et al., 2013). Supervisors should ask all trainees about their culture and how it influences their clinical work and provide an opportunity to discuss relevant aspects of diversity and culture, including disability. It may be helpful to include such discussion points about diversity, especially disability status, in a supervision contract that may be used at the outset of a supervisory relationship. Culturally sensitive supervisors are not expected to have competency in all aspects of diversity, but supervisors can alleviate the burden placed on TSD by learning about disability culture and demonstrating cultural humility (Andrews et al., 2013). Disability culture has its own core values (e.g. use of disability humor, appreciation of diversity, acceptance of vulnerability and interdependence, shared language and terminology) and specific language and behaviors (see (Andrews et al., 2019; Andrews & Kuemmel, 2016). Just like other cultural identities, disability culture is heterogeneous and a curious attitude by mentors, supervisors, and leadership will help to individually tailor their effectiveness with TSD.

Culturally competent supervision can be achieved practically in several ways. First, supervisors can regularly inquire of all trainees whether any accommodations are required, regardless of whether a disability is apparent. Next, supervisors can also ask trainees how to best provide accommodations in supervision and empowers the trainee to assess and assert individual needs. Such discussions will likely be ongoing conversation, with check-ins, as appropriate, on the status of accommodations and whether they are sufficient and adequate. Finally, supervision has specific supervision aims. It is not professional or appropriate for supervisors to probe trainees about their disabilities for their own curiosity (Andrews et al., 2013). These three steps will can empower TSD and reduce fears of disclosure, stigma, and discrimination.

Help TSD respond to clients

As noted above, supervisors can help TSD understand and respond to clients’ reactions to the trainee’s disability in a way that is clinically appropriate and comfortable for the trainee (Andrews et al., 2013). TSD will often need to self-disclose or discuss their disability and accommodations during clinical work. Many TSD, such as the example of Josie, experience anxiety about navigating self-disclosure. Supervisors should be prepared and willing to process and problem-solve reactions to disability in supervision. To this end, it can be helpful to role-play with the trainee various ways to disclose their disability or respond to clients’ reactions. Similar to other forms of self-disclosure, supervisors may help TSD discern when such disclosures may be appropriate or inappropriate.

Negotiate and provide reasonable accommodations

Accommodations range from small modifications to institutional supports and can affect many areas. For supervision, the traditional format may shift depending on TSD accommodations. For example, if a trainee is hard of hearing, supervisors may need to speak loudly, annunciate clearly, and face the trainee so nonverbal communication is visible. For assessments, if a trainee cannot administer certain tests or subtest due to standardization requirements, the supervisor and TSD may brainstorm alternatives to delivering tests (e.g. psychometrician) and focus training on core clinical competencies like test selection and interpretation. Alternatively, the test itself might need to be or already have been adapted. For example, a blind student may be able to give a verbal memory test to a patient if it was translated into Braille or a version that has been adapted (e.g., Montreal Cognitive Assessment) might be used instead. Training directors, faculty and supervisors are best equipped to advocate for the TSD with institutional officers and services, if necessary, given their relative familiarity with the institutional resources. If accommodations are denied, program faculty and supervisors might emphasize the required nature of clinical training. Identifying and implementing reasonable accommodations for TSD can be complex; faculty and supervisors may also seek consultation with clinical leadership, resources provided by the APA, and wider training networks.

Clinical research, similar to practica or internship sites, may be another area where clarification of roles and clear advocates is necessary. Many disability services or offices believe clinical research training activities are beyond their purview. Thus, TSD may need to coordinate with multiple offices and advocating faculty or supervisors to obtain necessary accommodations in clinical and research settings. TSD and program faculty may consider exploring these possibilities upon admission in order to identify potential difficulties in securing accommodations and begin navigating them early. Another important consideration is whether a particular clinical research area is well-suited to the TSD’s individual needs and abilities, which may also require mentorship. TSD and program advocates may benefit from consultation with a wider faculty network, who include faculty with disabilities at other institutions.

Enhance professional development

As supervisors and program faculty are instrumental during early phases of training for fostering and cultivating a professional identity, supervisors should assist TSD to develop their own style for coping with systemic and attitudinal barriers, such as microaggressions from clients, supervisors, faculty, and peers. Additionally, supervisors can facilitate growth by connecting trainees with other mentors. Even the most empathetic and culturally competent mentors may lack the shared experience of persons with disabilities, making establishing connections with fellow professionals with disabilities extremely important.

Guidelines for Improvement: Clinical Leadership

Prioritize training in core competencies

TSD may be unable to complete every single aspect of training and still able to develop all core competences. For example, the APA has documented one of the major barriers to clinical training is providing reasonable accommodations for testing and assessment, as it is often difficult to obtain accessible versions of materials and many disabilities interfere with the clinician’s ability to administer and score assessments according to standardized protocols (American Psychological Association, 2011b). Clinical leadership, such as training directors, who are well versed in core competencies can work with TSD towards prioritizing training in the required competencies, such as the assessment example provided above. Clinical leadership can work with the trainee to determine which are necessary to achieve core competencies and career goals.

Provide training in cultural competence that incorporates disability

Clinical leadership can ensure that their training program, supervisors, and students incorporate disability as one of the many forms of diversity. Cultural competence trainings and requirements should include disability status in order to increase awareness and acknowledgement of diversity in all of its forms—in students, supervisors, and clients. Such trainings should incorporate cultural humility, that is, recognizing the limitations of one’s knowledge, competence as an ongoing and continual learning process, and openness to feedback.

Collaborate with TSD and relevant stakeholders to determine reasonable accommodations

Clinical leadership can work closely with TSD to determine the types of training and reasonable accommodations to achieve the necessary core competencies and the trainee’s career and programmatic goals so that abilities and limits are discussed rather than assumed. This would ideally result in a collaboratively determined set of reasonable accommodations. Once accommodations are clarified, their implementation will need ongoing support. For example, a common accommodation for TSD is extended or flexible time. In the classroom, extended time for assignments and standardized testing has become a norm; however, in clinical training, restructuring timelines and programmatic requirements is less systematized and few precedents may exist. An often overlooked but profound consequence of disability is functional differences in time, known as “crip time” (Kuppers, 2014). “Crip time” is a disability culture term that refers to a flexible approach to normative time and encompasses the invisible and often time-consuming labor people with disabilities must do to achieve equal access (Hannam-Swain, 2018). Adhering to and accommodating “crip time” means individualizing clinical training for the flexibility in timing required across classes, meetings, milestones, or practica. In some cases, solutions may be as straightforward as providing additional time to access materials or complete program milestones. In other cases, it may be necessary to discuss options such as remaining at a particular practicum site for longer in order to accrue sufficient clinical experiences or having realistic conversations about the amount of time necessary to achieve certain benchmarks. TSD who rely on public transportation may also benefit from not needing to travel to secondary sites. In collaboration with relevant stakeholders, clinical leadership can identify reasonable adjustments to training for TSD and advocate on their behalf.

Provide accommodations in graduate psychology training clinics

Graduate training clinics (i.e. university clinics) teach the fundamentals of treatment and assessment and model for TSD about which accommodations reasonable in clinical settings. As they may be smaller and more flexible than other clinical settings, these clinics also offer a relatively safe environment for TSD to practice making accommodation requests, self-disclosing to clients, and determining options for accommodations. Working with TSD can be viewed as opportunities for clinical leadership to learn about whether their clinical environment is inclusive for trainees and clients alike and improve the delivery of care and training in an accessible way. Clinic policies should be reviewed for their ability to provide accessible services and training to all clients, trainees, and supervisors.

Clinical leadership can facilitate reasonable accommodations for TSD by aiding in access to learning, spaces, and materials. Access to learning may include facilitating the use of a signed interpreter in clinical settings. Access to spaces may include ensuring training clinics are equipped with automatic doors, Braille signage, and other reasonable accommodations. Access to materials may include accommodating material formats (e.g. providing digital or large print materials) and when necessary, seeking support from University disability programs. Clinical leadership can also ensure processes and systems for clinical documentation are accessible (e.g., progress notes, treatment plans, and diagnostic evaluations). Many electronic medical records (EMR) software are not accessible or are not user friendly for some TSDs. In these cases, collaboration with the TSD can lead to developing thoughtful, alternative approaches (e.g., sending the note or report directly to the staff who can upload the documentation or sitting with the trainee to help them navigate and work efficiently within the EMR system).

Assess whether accommodations to training are timely and sufficient

As noted above, ongoing review adequacy of accommodations is necessary. As novice clinicians, TSD may not be aware which accommodations are working best for them. Disabilities are also not static and may have differential effects over time (e.g. relapses or progression). Regular check-ins and consultation with knowledgeable others can lead to creative solutions for insufficient accommodations. Getting reasonable accommodations ‘right’ should be viewed as an iterative and ongoing refinement process. Working proactively before problems arise is essential, such as making textbooks available ahead of when the term begins.

Conclusion and Implications

TSD in HSP face many barriers and this likely contributes to the widespread underrepresentation of people with disabilities in our field. TSD report many barriers including stigma, bias, and discrimination; lack of education and awareness; lack of access; and difficulty due to power dynamics impacting TSD. We outline guidelines for TSD, program faculty and supervisors, and clinical leadership to enhance the likelihood that TSD will succeed in our field. All have their part to play. TSD must find appropriate avenues for accommodation requests, develop necessary assertiveness skills, and learn clinical judgment and intuition for effective discussions with clients. Program faculty and supervisors can engage in culturally sensitive practices to enhance the experience of TSD by evaluating their own biases, open-mindedly assessing trainees’ needs for accommodations, continuing to discuss these needs as training unfolds, flexibly delivering supervision based on trainees’ needs, and helping trainees navigate discussion of disability in session. Clinical leadership, such as clinic directors and training directors can collaborate with TSD to discuss needs and career goals, ensure achievement of core competencies through reasonable accommodations, and facilitate access to learning, spaces, materials, and institutional resources for TSD. Leadership can continue to learn about the needs of TSD and advocate for change. Although TSD face substantive barriers to professional opportunities, trainees, program faculty and supervisors, and clinical leadership have the ability to mitigate the interference caused by these barriers and improve the representation of our field. We hope the guidelines offered here facilitate greater access to clinical training for TSD.

Public Health Statement:

People with sensory disabilities are underrepresented in clinical training programs, and this may be in part because clinical trainees with sensory disabilities have distinct training needs. This paper illustrates the barriers faced by trainees with sensory disabilities and offers recommendations for improving access and inclusion across relevant stakeholders, including trainees, faculty and supervisors, and clinical leadership.

Acknowledgments

The first author was supported by the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program and the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01 MH110477-04S1).

References

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective June 1, 2010, and January 1, 2017). https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

- American Psychological Association. (2000). Enhancing Your Interactions With People With Disabilities. https://www.apa.org/pi/disability/resources/publications/enhancing

- American Psychological Association. (2008). Disability Mentoring Program. https://www.apa.org/pi/disability/resources/mentoring/index

- American Psychological Association. (2009). Barriers to Students with Disabilities in Psychology Training. https://www.apa.org/pi/disability/dart/survey-results.pdf

- American Psychological Association. (2011a). Resource guide for psychology graduate students with disabilities. http://www.apa.org/pi/disability/resources/publications/second-edition-guide.pdf

- American Psychological Association. (2011b). Training Students with Disabilities in Testing and Assessment. 10.1002/ejoc.201200111 [DOI]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. American Psychologist, 57(12), 1–20. 10.1037/0003-066X.57.12.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2019). Impact: APA and APA Services Inc. Strategic Plan. https://www.apa.org/about/apa/strategic-plan/impact-apa-strategic-plan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Andrews EE (2019). Disability As Diversity: Developing Cultural Competence. In New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews EE, Forber-Pratt AJ, Mona LR, Lund EM, Pilarski CR, & Balter R (2019). #SaytheWord: A Disability Culture Commentary on the Erasure of “Disability.” Rehabilitation Psychology, February. 10.1037/rep0000258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews EE, & Kuemmel A (2016). Fostering a Disability-Affirmative Training Environment and Providing Culturally Competent Supervision to Trainees with Disabilities. APPIC Membership Conference. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews EE, Kuemmel A, Williams JL, Pilarski CR, Dunn M, & Lund EM (2013). Providing culturally competent supervision to trainees with disabilities: In rehabilitation settings. Rehabilitation Psychology, 58(3), 233–244. 10.1037/a0033338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews EE, & Lund EM (2015). Disability in psychology training: Where are we? Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 9(3), 210–216. 10.1037/tep0000085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brault MW (2012). Americans with disabilities 2010. Current Population Reports, U.S. Census Bureau. http://www.census.gov/prod/2012pubs/p70-131.pdf

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, U. S. D. of L. (2019). Occupational Outlook Handbook (Pilot M (ed.)).

- Callahan JL, Smotherman JM, Dziurzynski KE, Love PK, Kilmer ED, Niemann YF, & Ruggero CJ (2018). Diversity in the professional psychology training-to-workforce pipeline: Results from doctoral psychology student population data. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 12(4), 273–285. 10.1037/tep0000203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Disability and Health Overview. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html#ref [Google Scholar]

- Davis NA (2005). Invisible Disability*. Invisible Disability Author Ann Davis Source: Ethics Ethics, 116(1), 153–213. 10.1086/453151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohue C (2015). No, I Cannot Hear You : The Impact of Disability on Professional Identity Development of a Psychology Doctoral Candidate with Severe to Profound Hearing Loss Colleen Donohue A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Chicago School of Professional Ps.

- Hannam-Swain S (2018). The additional labour of a disabled PhD student. Disability and Society, 33(1), 138–142. 10.1080/09687599.2017.1375698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser PC, Maxwell-McCaw DL, Leigh IW, & Gutman V. a. (2000a). Internship accessibility issues for deaf and hard-of-hearing applications: No cause for complacency. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31(5), 569–574. 10.1037/0735-7028.31.5.569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser PC, Maxwell-McCaw DL, Leigh IW, & Gutman VA (2000b). Internship accessibility issues for deaf and hard-of-hearing applicants: No cause for complacency. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 31(5), 569–574. 10.1037/0735-7028.31.5.569 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez B, & McDonald K (2007). Exploring the bottom line: A study of the costs and benefits of workers with disabilities.

- Joshi H (2006). Reducing Barriers to Training of Blind Graduate Students in Psychology. Doctoral Dissertation, Publicatio([Doctoral Dissertation, Alliant International University]), ProQuest Dissertation Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Knox S, & Hill CE (2003). Therapist self-disclosure: Research-based suggestions for practitioners. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(5), 529–539. 10.1002/jclp.10157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppers P (2014). Crip Time. Tikkun Magazine, 29(4), 29–31. 10.1215/08879982-2810062 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lund EM, Andrews EE, Bouchard LM, & Holt JM (2019). How Did We Help (or Not)? A Qualitative Analysis of Helpful Resources Used by Psychology Trainees With Disabilities. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1–25. 10.1037/tep0000270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lund EM, Andrews EE, Bouchard LM, & Holt JM (2020a). How Did We Help (or Not)? A Qualitative Analysis of Helpful Resources Used by Psychology Trainees With Disabilities. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 14(3), 242–248. 10.1037/tep0000270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lund EM, Andrews EE, Bouchard LM, & Holt JM (2020b). Left wanting: Desired but unaccessed resources among health service psychology trainees with disabilities. Training and Education in Professional Psychology. 10.1037/tep0000330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lund EM, Andrews EE, & Holt JM (2014). How we treat our own: The experiences and characteristics of psychology trainees with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 59(4), 367–375. 10.1037/a0037502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund EM, Andrews EE, & Holt JM (2016). A qualitative analysis of advice from and for trainees with disabilities in professional psychology. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 10(4), 206–213. 10.1037/tep0000125 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lund EM, Wilbur RC, & Kuemmel AM (2020). Beyond legal obligation: The role and necessity of the supervisor-advocate in creating a socially just, disability-affirmative training environment. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 14(2), 92–99. 10.1037/tep0000277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olkin R (2002). Could you hold the door for me? Including disability in diversity. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 8(2), 130–137. 10.1037/1099-9809.8.2.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olkin R, & Pledger C (2003). Can Disability Studies and Psychology Join Hands? American Psychologist, 58(4), 296–304. 10.1037/0003-066X.58.4.296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omitted. (n.d.). We Must Do Better: Trends in Disability Representation Among Pre-doctoral Internship Applicants.

- Pearlstein JG, & Soyster PD (2019). Supervisory Experiences of Trainees With Disabilities : The Good, the Bad, and the Realistic. 13(3), 194–199. 10.1037/tep0000240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scott J (2010). Disabled Student Programs & Services. https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/28863419/disabled-student-programs-services-california-community-

- Taube DO, & Olkin R (2011). When Is Differential Treatment Discriminatory? Legal, Ethical, and Professional Considerations for Psychology Trainees With Disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 56(4), 329–339. 10.1037/a0025449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Kemp H, Shiomi Chen J, Nagel Erickson G, & Friesen NL (2003a). ADA Accommodation of Therapists with Disabilities in Clinical Training. Women and Therapy, 26(1), 155–168. 10.1300/J015v26n01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vande Kemp H, Shiomi Chen J, Nagel Erickson G, & Friesen NL (2003b). ADA Accommodation of Therapists with Disabilities in Clinical Training. Women and Therapy, 26(1–2), 81–94. 10.1300/J015v26n01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur RC, Kuemmel AM, & Lackner RJ (2019). Who’s on first? Supervising psychology trainees with disabilities and establishing accommodations. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 13(2), 111–118. 10.1037/tep0000231 [DOI] [Google Scholar]