Abstract

Background: Informal payments limit equitable access to healthcare. Despite being a common phenomenon, there is a need for an in-depth analysis of informal charging practices in the Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) context. We conducted a systematic literature review to synthesize existing evidence on the prevalence, characteristics, associated factors, and impact of informal payments in SSA.

Methods: We searched for literature on PubMed, African Index Medicus, Directory of Open Access Journals, and Google Scholar databases and relevant organizational websites. We included empirical studies on informal payments conducted in SSA regardless of the study design and year of publication and excluded reviews, editorials, and conference presentations. Framework analysis was conducted, and the review findings were synthesized.

Results: A total of 1700 articles were retrieved, of which 23 were included in the review. Several studies ranging from large-scale nationally representative surveys to in-depth qualitative studies have shown that informal payments are prevalent in SSA regardless of the health service, facility level, and sector. Informal payments were initiated mostly by health workers compared to patients and they were largely made in cash rather than in kind. Patients made informal payments to access services, skip queues, receive higher quality of care, and express gratitude. The poor and people who were unaware of service charges, were more likely to pay informally. Supply-side factors associated with informal payments included low and irregular health worker salaries, weak accountability mechanisms, and perceptions of widespread corruption in the public sector. Informal payments limited access especially among the poor and the inability to pay was associated with delayed or forgone care and provision of lower-quality care.

Conclusions: Addressing informal payments in SSA requires a multifaceted approach. Potential strategies include enhancing patient awareness of service fees, revisiting health worker incentives, strengthening accountability mechanisms, and increasing government spending on health.

Keywords: Informal payments, health, Sub-Saharan Africa, review

Introduction

The health financing gap in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) persists 1 . LMICs accounted for only 20% of the global spending on health in 2016 despite being home to over 80% of the world’s population and bearing the greatest disease burden 1 . The low government spending in LMICs contributes to out-of-pocket payments (OOPs) becoming a major source of health financing 2, 3 , accounting for almost half of the total health expenditure 4, 5 . OOPs are payments made directly to healthcare providers by individuals at the point of care and this excludes prepayment mechanisms such as health insurance or taxes 3 . OOPs, represent direct costs of care associated with disease management 6, 7 and they can be officially stipulated fees and sometimes unofficial or what is referred to as informal payments 2 .

Informal payment can be defined as, “a direct contribution, which is made in addition to any contribution determined by the terms of entitlement, in cash or in-kind, by patients or others acting on their behalf, to health care providers for services that the patients are entitled to” 8 . Some of the difficulties associated with studying informal payments include being deemed illegal in some countries thus making them a sensitive research topic 9, 10 . This is compounded by the fact that some patients are unable to differentiate between official and unofficial fees 9, 10 , while others refuse to respond to questions on informal payments 9, 10 . All these factors make it challenging to estimate the magnitude and frequency of informal payments 9 .

Despite the challenges of measuring informal payments, evidence shows that they are a common phenomenon in many countries 9, 10 . They comprise a significant share of OOPs, accounting for 10% to 45% of total OOPs for healthcare in low-income countries 10, 11 . Informal payments have also been reported to account for a substantial proportion of health financing resources in countries in transition 10 . They have been argued to impede healthcare reforms 9, 11 , and reduce the efficiency and quality of care 9, 12 . They also limit access to care especially among the poorest and can result in catastrophic healthcare expenditure that pushes households into poverty 10, 13 . The occurrence of informal payments has been linked to various factors. On the supply side, informal payments have been associated with inadequate funding of the health sector 9 , limited transparency and accountability 10, 14 , and low/irregular remuneration of staff 10, 15 . On the demand side, patients pay informally to access care 16, 17 , jump queues 18 , and receive better quality services 17, 19 . Contextual factors such as perceptions of high levels of corruption in the public sector 14 , distrust in public institutions 10, 11 , and norms of gift-giving also influence informal payments 10, 14 .

Informal payments are common in almost all African countries 13 . The 2016/18 Afrobarometer survey - a nationally representative survey that provides data on citizens' experiences and perceptions of corruption across African countries - showed that more than one in four people who sought public services such as health services and education paid a bribe. This amounted to approximately 130 million people in 35 African countries 20 . The nature and level of informal payments can be quite specific to the health system, socio-cultural, economic, and political context. While several reviews have sought to synthesize evidence on informal payments 10, 12, 21 , none provide a comprehensive review of informal payment practices in the SSA context.

This systematic literature review aimed to synthesize the existing evidence on the prevalence, characteristics, reasons, associated factors, and the impact of informal payments for healthcare in SSA. Findings from this review may help policymakers to gain a better understanding of informal payments and point to a range of factors they could address when developing interventions to curb informal payments. This is crucial as many SSA countries implement strategies to enhance financial risk protection as they progress towards attaining universal health coverage (UHC). This article is reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 22 .

Methods

Search strategy

To identify relevant literature, we searched PubMed, African Index Medicus, Directory of Open Access Journals, and Google Scholar databases. The search terms were developed with reference to the search strategies used in recent literature reviews on informal payments for healthcare 10, 12, 21 . The main search term was “informal payment/fee/charge/expenditure” and its synonyms, that is, unofficial, illegal, illicit, envelope, under-the-table, under-the-counter, and solicited payments/fee/charge/expenditure, or bribe or corruption. These terms were combined with “health” and the list of SSA countries where applicable. The databases were last searched in August 2021. The search strategies for each database can be found as extended data 22 .

Bibliographies of included articles were also searched to identify any relevant articles. Additionally, grey literature was searched for using free text searches on Google and websites of organizations that publish on various aspects of corruption in the health sector such as Transparency International, World Bank, World Health Organization, United Nations Development Fund, and Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were any empirical studies on informal payments conducted in SSA, regardless of the study design, published in any year, and in the English language. The exclusion criteria entailed reviews, editorials, and conference presentations. EK screened the articles at all levels: title, abstract and full text. Articles selected for inclusion in the review were discussed and agreed upon in consultation with the co-authors.

Quality appraisal of included studies

The quality of qualitative studies was appraised using the critical appraisal skills program (CASP) checklist for qualitative research 23 ; while the quality of quantitative studies was assessed using the appraisal tool for cross-sectional studies (AXIS) 24 . Mixed methods studies were appraised using both appraisal tools.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted using tables in Microsoft Excel version 16 and this entailed general study characteristics ( Table 1) and findings. Due to the variation in approaches to measuring the prevalence of informal payments across countries, a meta-analysis of quantitative data was not appropriate. We, therefore, conducted a narrative synthesis of the findings, exploring similarities and differences across the studies and contexts 25 . A modified framework analysis approach was conducted for qualitative studies. This entailed familiarisation with the data, identification of themes, indexing data based on the themes, charting the data for comparisons, interpreting the data while exploring for relationships between concepts 26 .

Table 1. General description of studies included in the review.

| Category | Sub-category | No. | Study reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication type | Journal article

Report |

20

3 |

13,

31–

35,

36–

49

20, 50, 51 |

| Year of publication | After 2015

2011–2015 2006–2010 2001–2005 1995–2000 |

10

7 5 0 1 |

13,

20,

32,

34,

37,

46–

50

31, 38, 40– 42, 44, 51 33, 35, 36, 39, 45 43 |

| Data collection year | After 2015

2011–2015 2006–2010 2001–2005 1995–2000 Not clear |

4

7 5 2 4 4 |

20,

34,

48,

49

13, 32, 34, 44, 46, 47, 51 13, 35, 37, 41, 42 31, 39 31, 33, 43, 50 36, 38, 40, 45 |

| Country income level (2021 World

Bank classification) |

Low-income

Lower-middle-income Upper-middle-income |

10

15 3 |

13,

20,

31,

39,

40,

43,

44,

46,

47,

50

13, 20, 32– 38, 41, 42, 45, 48, 49, 51 13, 20, 31 |

| Number of countries in each study | Single country

Multi-country |

20

3 |

32–

51

13, 20, 31 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa Region | East Africa

West Africa Central Africa Southern Africa |

12

8 4 5 |

13,

20,

31,

34,

35,

39,

41–

43,

45,

49,

51

13, 20, 32, 36, 40, 44, 47, 50 13, 20, 37, 46 13, 20, 31, 33, 48 |

| Type of study design | Quantitative

Qualitative study Mixed methods |

11

7 5 |

13,

20,

35–

37,

39–

41,

48,

49,

51

32– 34, 42, 44, 45, 50 31, 38, 43, 46, 47 |

| Study participants | Healthcare workers

Patients Households General public/ community members Policymakers |

16

8 7 5 2 |

31–

34,

36–

38,

40–

47,

49

32, 33, 36, 37, 41, 43, 48, 50 13, 20, 31, 35, 36, 39, 51 31, 33, 40, 43, 44 38, 44 |

Results

Search results

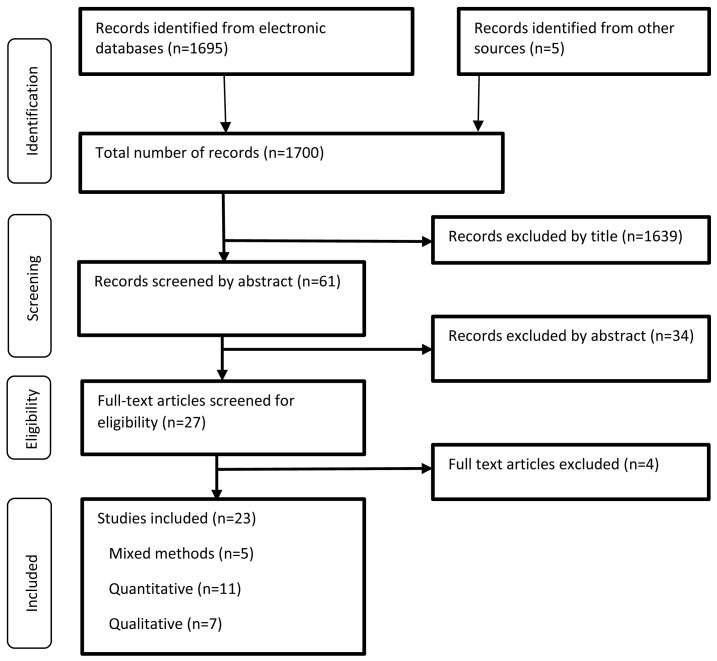

The literature search retrieved a total of 1700 articles which were exported into Endnote X7. Articles were screened and excluded by title, abstract, and full text respectively. Articles excluded after full text review focused on other forms of corruption other than informal payments 27– 29 , or informal payments were combined with other payments 30 . Overall, 23 articles were included in this review; 20 peer-reviewed articles and three grey literature. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process.

Figure 1. Study selection process adapted from the PRISMA 2009 flow diagram 52 .

Study characteristics

The majority of studies (n=12) were conducted in East Africa while Central Africa had the least number of studies (n=4) ( Table 1). Three of the studies were conducted in multiple countries; one study used data from round 3 and 5 of the Afrobarometer survey conducted in 18 and 33 countries, respectively 13 , while the second study reported findings from rounds 6 and 7 of the Afrobarometer survey conducted in 36 and 35 countries, respectively 20 . The third multi-country study was conducted in seven countries of which two were from Africa (Uganda and South Africa) 31 . Most studies (n=7) were conducted between 2011 and 2015. Five studies used mixed methods, eleven were quantitative, and seven were qualitative. The studies were conducted with a diverse group of participants with the majority being healthcare workers, patients, and households. Most studies assessed informal payments for health services in general while seven studies looked at informal payments for specific services, that is, maternal and child health services 32– 35 , emergency services 50 , malaria treatment 36 , and HIV services 37 .

Prevalence of informal payments in SSA

Informal payments are a common phenomenon across East, West, Central, and Southern Africa but there was a notable variation in the prevalence across these regions ( Table 2).

Table 2. Prevalence of informal payments reported in cross-sectional studies.

| Author & country | Data

collection year |

Sample size and study

population |

Metric | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papers based on Afrobarometer surveys | ||||

| Pring & Vrushi

20

; 35 African

countries |

2016–2018 | 47,000 households | The proportion that gave a gift/paid a bribe/did a favor to get services

at a public health center or clinic in the past 12 months |

1.0–50.0%

mean:14.0% |

| Kankeu & Ventelou

13

; 33 African

countries |

2011–2013

2005–2006 |

51,605 households (33

countries) 25,397 households (18 countries) |

The proportion that paid a bribe, gave a gift or did a favor to

government officials to get treatment at a local health clinic or hospital in the past 12 months |

0.4-51.3%

2.9-47.8% |

| Studies based on patient/household reports | ||||

| Masiye et al. 48 ; Zambia | 2018 | 1900 patients | The proportion that made any payments for healthcare services

received at public primary health facilities on the survey day |

6.2% |

| Oduor 51 ; Kenya | 2012 | 183 households | The proportion that paid informal payments at public health facilities | 10.0% (inpatient care)

8.0% (outpatient care) |

| Kruk et al. 35 ; Tanzania | 2007 | 1322 women | The proportion that paid provider payments for free facility delivery

services at government health facilities within the 5 years before the survey |

84.6% (dispensary)

35.7% (health centers) 30.0% (hospitals) |

| Lindkvist 41 ; Tanzania | 2007 | 3494 patients | The proportion that reported that healthcare workers at public and

faith-based facilities accept informal payments |

12.0% |

| Kankeu et al. 37 ; Cameroon | 2006–2007 | 1637 HIV patients | The proportion that made informal payments for consultation with a

doctor at public and private facilities on the survey day |

3.1% |

| Paredes-Solís

et al.

31

; Uganda and

South Africa |

1998

2003 |

18,412 households (Uganda)

5,490 households (South Africa) |

The proportion that made payments directly to healthcare workers at

government health facilities |

28.0%

1.0% |

| Hunt 2010 39 ; Uganda | 2002 | 12,000 households | The proportion that had paid a bribe at a public or private health

facility in the past three months |

17.0% (public sector)

11.0% (private sector) |

| Studies based on health workers reports | ||||

| Binyaruka et al ;Tanzania 49 | 2019 | 432 health workers | The proportion that had ever asked for/been given informal payment/

bribe from clients at public primary care facilities |

27.1% |

| Maini

et al.

46

; Democratic Republic

of Congo (DRC) |

2014 | 406 nurses | The proportion that received informal payments/gifts from patients at

public primary care facilities in the last month |

16.8% |

| Bertone & Lagarde 47 ; Sierra Leone | 2013–2014 | 266 health workers | The proportion that received gifts and payments from patients in the

past month at public primary care facilities |

74.0% |

| Akwataghibe et al. 38 ; Nigeria | not stated | 69 healthcare workers | The proportion that accepted gifts and informal payments from

patients at public health facilities in exchange for priority treatment |

33.4% |

Prevalence from Afrobarometer studies. The most comprehensive data comes from a series of Afrobarometer surveys 13, 20 . Round 7 (2016-18) conducted in 35 African countries showed that between 1% (Botswana) and 50% (Sierra Leone) of survey respondents had given a gift/paid a bribe/done a favor to get services at a public health center or clinic in the 12 months preceding the survey. Southern Africa countries accounted for more than half (8/15) of the countries with a prevalence of informal payments that was less than 10% while most of the countries with a prevalence above 20% were from Western Africa (4/10) followed by Central Africa (3/10) 20 . Consecutive rounds of the Afrobarometer survey showed indications of increasing prevalence over time in over half (18/30) of the SSA countries that took part in both round 6 (2014-15) and round 7 20 . Similar trends were seen in perceptions of general corruption in the public sector, with 55% of citizens surveyed in 35 African countries in round 7 feeling that corruption was getting worse.

Prevalence from other studies. Other cross-sectional studies also demonstrated considerable variation in the prevalence of informal payments across 9 settings in terms of both the proportion of patients reporting paying them and the proportion of health workers reporting receipt ( Table 2).

Characteristics of informal payments

These entailed who initiated, the type, the timing, and the amount of informal payment paid.

Initiation of informal payments. Both healthcare workers and patients initiated informal payments. Most studies where households or patients were interviewed reported that healthcare workers usually made demands for informal payments 13, 31, 32, 43, 51 . However, in Angola, some women offered informal payments to receive pregnancy and childbirth services before demands were made hoping it would reduce the amount of money paid informally or to ensure in-kind payments would suffice 33 . A qualitative study conducted with healthcare workers in Tanzania also reported that informal payments were initiated more often by patients than providers because patients felt they needed to pay informally to receive quality services 45 .

Type of informal payments. Informal payments made in cash 33, 36– 39, 42, 43, 45 were more common than those made in kind 33, 38, 46, 47 . Informal payments were charged in addition to other fees or as standalone fees 43 . For example, in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), in-kind payments came often in form of food, soap, or fabric 46 , and in Sierra Leone, this comprised poultry, food, and charcoal 47 .

Timing of informal payments. Informal payments were made before 32, 50 or after service delivery 33, 42, 50 . For example, relatives of patients seeking emergency services in Niger reported making informal payments before service provision following demands from healthcare workers and after service provision as a sign of gratitude 50 . Some women in Angola reported that they would have preferred if the midwives delivered care first before asking for informal payments 33 .

The amount of informal payment. In total, eight studies assessed the amount of informal payments made. These studies were based on reports made by patients (n=2), households (n=2), healthcare workers (n=2), both household and patients (n=1), and the community (n=2) 46, 47 . Regarding health worker reports, a survey conducted in DRC showed that they earned a mean income of $9 per month from informal payments 46 while in Sierra Leone informal payments accounted for 5% of total revenues for community health assistants and nurses ($11.8) and maternal and child health aides ($8.2) and 3% for community health officers ($9.42) per month 47 . In terms of patient reports, for example, informal payments were the second key contributor to healthcare costs after transport costs in Tanzania accounting for 26.6% (1668 TZS (95% confidence interval [CI]: 931–2405)) of facility delivery costs at government facilities despite deliveries being exempt from user fees 35 .

Regarding the type of service, in Kenya for example, informal payments varied depending on the family planning method. Despite being officially free, informal payments were required, with higher amounts charged for long-acting methods 34 . Similarly, in Angola, informal payments were higher for cesarean sections compared to normal deliveries, even though cesarean sections were exempt from user fees 33 .

Reasons for paying informal payments

Patients or their relatives made informal payments for treatment to be initiated 32, 50 , to receive both minor services such as bedpans 42 , injections 51 , or vaccinations 33 ; and major services, such as surgeries 32, 42 . Informal payments were also made to receive drugs that were supposed to be provided for free 32– 34, 42, 44, 48, 51 , and to obtain medical record books and reports 48 . In Tanzania, some healthcare providers feigned stockouts of commodities and sought money from patients disguising to purchase the commodities from the private market on their behalf 42 . Informal payments were also made to enable patients to skip queues 33, 42, 45 in an effort to get services more quickly 33, 45, 51 . Some patients made informal payments hoping to receive higher quality services in return 32, 43, 45, 51 . In extreme cases, informal payments were made to enable patients to gain access to the health facility in Niger 50 , to obtain meals in Kenya 51 , and for family members to see the newborn baby for the first time in Benin 32 . Informal payments were also made to express gratitude in Angola, Tanzania, and Nigeria 33, 34, 38, 42, 43 . Qualitative studies showed that some healthcare workers in Nigeria and Tanzania perceived informal payments as an acceptable practice and as gifts to show appreciation for their work 38, 42 .

Patient factors associated with informal payments

These comprised socioeconomic characteristics, health status, and social connections ( Table 3).

Table 3. Patient factors associated with informal payments.

| Patient factors | Number of

citations |

Study reference |

|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic characteristics | ||

| Age | 2 | 37, 48 |

| Marital status | 1 | 37 |

| Employment status | 1 | 37 |

| Income/wealth | 7 | 13, 33, 37, 39– 41, 46 |

| Household head | 1 | 31 |

| Residence (rural/urban) | 3 | 36, 37, 48 |

| Distance to the health facility | 1 | 48 |

| Awareness of service entitlements and fees | 3 | 32, 34, 46 |

| Health status | ||

| Self-rated health | 1 | 37 |

| Change in health status e.g. during pregnancy/labor | 1 | 33 |

| Social connections | ||

| Absence of connections with health facility staff | 1 | 50 |

Socioeconomic characteristics. People who were not aware of service entitlements and fees 32, 34, 46 , married people 37 , and those from male-headed households, which were probably less vulnerable than female-headed households 31 , were more likely to make informal payments while older people 37 were less likely to pay informally. Regarding the amounts paid, the employed 37 , older patients, people traveling long distances to health facilities 48 , and those living in urban areas incurred higher amounts of informal payments 36, 37 . However, in Zambia patients who sought services at rural compared to urban primary health facilities paid higher amounts of informal payments 48 .

There were mixed findings on whether informal payments were more common among the rich or the poor. However, there seemed to be stronger evidence to support the latter. The prevalence was higher among the poor in almost all of the 33 countries that took part in round 5 of the Afrobarometer survey as evidenced by concentration indices ranging from -0.356 to 0.099 13 . Nonetheless, two nationally representative surveys conducted in Uganda and Cameroon 37, 39 reported that the rich were more likely to pay informal payments than the poor. Data from round 3 of the Afrobarometer survey conducted in 18 African countries also showed that healthcare workers demanded informal payments from the poor more than the rich (concentration indices ranging from -0.277 to 0.083) 13 . However, a quantitative study that used a rating scale ranging between 0 (not at all acceptable) and 10 (completely acceptable) showed that in Togo, physician requests for informal payments were perceived to be more acceptable when patients were wealthy (Median (M)=6.35) than when they were poor (M=1.73) 40 . Women taking part in focus group discussions (FGDs) in Angola reported that midwives did not solicit informal payments from the possibly well-off because they feared being reported 33 .

Regarding awareness, qualitative findings from Benin showed that pregnant women who were not aware of the cesarean section user fee exemption policy were charged to access those services 32 . In DRC nurses were less likely to charge informal payments in communities where people were aware of user fees out of fear of being reprimanded 46 .

Health status. Patient survey data from Cameroon showed that the incidence and amount of informal payments were higher among people living with HIV (PLWHA) who reported not taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) (7.31%) and having “poor” health status (7.24%) with the latter possibly aimed at receiving more attention from healthcare workers compared to PLWHA who reported taking ART (1.57%) and having “good” health status (1.57%) 37 . Similarly, FGD participants in Angola reported that the amount of informal payments demanded increased remarkably if a pregnancy or labor changed from normal to complicated to the extent of forcing families to sell assets, borrow money, or beg to receive treatment 33 .

Social connections. Only one study reported on social connections. This qualitative study conducted in Niger showed that in the absence of connections (relatives, friends, and acquaintances) at the health facility, patients or their relatives had to pay informal payments to various cadres and non-clinical staff to access services 50 .

Supply-side factors associated with informal payments

These entailed healthcare workers, health facility, and system-level characteristics ( Table 4).

Table 4. Supply-side factors associated with informal payments.

| Supply-side factors | Number of

citations |

Study reference |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare worker characteristics | ||

| Age | 2 | 46, 49 |

| Cadre | 7 | 32, 33, 38, 42, 45, 49, 50 |

| Health facility manager/in-charge/head of department | 2 | 47, 49 |

| Consultation venue i.e. health facility/healthcare workers residence | 1 | 43 |

| Salary (amount and timeliness) | 8 | 32– 34, 37, 40, 45, 49, 50 |

| Absence of allowances e.g. transport, risk | 1 | 45 |

| Health facility characteristics | ||

| Level of facility | 5 | 34– 36, 47, 48 |

| Facility ownership (public/private for profit/private non-profit) | 4 | 34, 37, 39, 42 |

| Facility location (rural/urban) | 2 | 47, 48 |

| Waiting times | 3 | 31, 37, 48 |

| Task shifting | 1 | 37 |

| Poor working conditions | 1 | 45 |

| Number of healthcare workers | 2 | 45, 46 |

| Lack of/stock out of essential drugs | 2 | 13, 48 |

| Presence/absence of official charging policies | 3 | 39, 43, 50 |

| Accountability mechanisms for user fees | 1 | 46 |

| Supervision/oversight over health worker behavior | 2 | 33, 49 |

| Poor health facility management | 1 | 41 |

| Engagement in informal charging/corruption by senior staff/facility managers | 2 | 34, 45 |

| Action against corrupt practices | 1 | 32 |

| System-level characteristics | ||

| Corruption among top health sector management | 1 | 45 |

| Wide-spread corruption in the public sector | 2 | 40, 45 |

| Health worker post rotations | 1 | 44 |

Healthcare worker characteristics. Healthcare workers of all cadres charged informal payments from specialists 42, 45, 49 , doctors 42, 45, 49 , nurses 33, 42, 45 , midwives 32, 33 to community health extension workers 38 , medical assistants 42, 45 and medical students 50 . In Sierra Leone, health facility managers/in-charges were almost three times more likely to receive gifts from patients compared to other staff (odds ratio [OR]=2.731 (1.139) P<0.05) 47 . Similarly, in Tanzania, departmental heads were more likely to engage in informal charging (adjusted OR [AOR] 1.72 (CI: 1.15–2.57) P<0.001) 49 . Doctors and specialists in Tanzania also had a higher likelihood of charging informal payments 49 and were reported to charge higher amounts compared to nurses or medical assistants 42, 45 . In Uganda, higher amounts were paid if patients went to consult healthcare workers at their place of residence 43 . Informal payments were less likely among health workers who were older compared to younger ones 46, 49 .

Informal social networks within and across cadres facilitated informal charging in some health facilities in Tanzania and Benin. Healthcare workers in Tanzania for example reported that informal payments were shared mainly across cadres. In some instances, there was overt cooperation across cadres to solicit informal payments 42 . Similarly, women who paid informally for cesarean section services in Benin reported that the midwives told them they would share the money with the other midwives, doctors, and other healthcare workers 32 . However, in one Tanzanian study, most healthcare workers felt that informal payments were not allocated fairly 42 . In this case and in the absence of rules on how to share informal payments, healthcare workers especially lower cadres, bargained to increase their share of the informal payment by lowering the quality of care, for example by giving less attention to patients who had bribed doctors 42 .

Informal payments were common among healthcare workers who received low 32– 34, 37, 40, 45 and irregular salaries 33, 34, 50 and less likely with increased health worker perception that benefits and entitlements were provided on time 49 . Healthcare workers reported that their salaries were inadequate to meet their basic needs 34, 45 and for the level of effort and skill required of them 34 . Laypeople and health professionals in Togo found it more acceptable (M=4.89) for physicians to request informal payments when they were underpaid than when they were well paid (M=3.06) 40 . The latter is supported by FGD findings from Tanzania where healthcare workers reported that informal payments were a coping strategy for their low salaries and lack of allowances 45 . Some women in Angola also acknowledged that the prolonged civil war which worsened everyone’s socioeconomic situation contributed to the charging of informal payments by midwives. However, some of the women also felt that their continued compliance with demands for informal payments perpetuated the practice 33 .

Despite complaints of low salaries, some healthcare workers in Tanzania perceived charging of informal payments as a form of corruption 42 which would damage their reputation and that of the health facility 45 . Some healthcare workers were also discouraged from charging informal payments because patients felt empowered to manipulate them after paying a bribe and this made healthcare workers feel humiliated and enslaved to patients 52 . This was in addition to some patients expecting to receive better treatment during subsequent visits 42 . In Kenya, healthcare providers acknowledged that charging informal payments was bad practice but some did not perceive informal payments as a challenge as long as the healthcare provider was willing to forgo the payment and offer health services if they discerned the patient did not have the ability to pay 34 . Healthcare providers were conflicted between meeting their basic needs for survival while also taking into account the financial hardship of the patients 34 .

Health facility characteristics. In terms of facility management, informal payments were more likely to be made at facilities that lacked official charging policies 39, 50 and oversight over healthcare workers behaviors’ 33 , and where senior staff and facility managers were reported to be corrupt or to engage in charging of informal payments 34, 45 . Informal charging was also more likely to take place at facilities with poor working conditions, staff 45 and medicine shortages 13 , long waiting times 31, 37, 48 , facilities that did not implement task shifting practices 37 , and urban facilities 47, 48 . With regards to waiting times and task shifting practices (delegation of subsequent consultations from doctors to nurses), patient survey data from Cameroon showed that patients seeking HIV care at facilities with long waiting times had a higher risk of paying informally (AOR 95% CI 3.68 (1.27–10.68)) P ≤ 0.05 while task-shifting of HIV services reduced the risk of incurring informal payments (AOR 95% CI 0.31 (0.11–0.90)) P ≤ 0.05 37 .

Informal payments were less likely to be made at facilities where patients paid official fees 39, 43 , facilities with accountability mechanisms for the user fees 46 , supervision throughout 49 and where action was taken against corrupt practices 32 . The likelihood of paying informally was also less at facilities with more staff 46 and those reported to be well-managed 41 .

In terms of facility ownership, there were mixed findings on whether informal payments were more prevalent in the public or private sector. In Uganda, the prevalence (17%) and amount of bribes ($6.06) paid by individuals in the public health sector were higher than the prevalence (11%) and the amount paid ($5.26) in the private sector (non-mission facilities) 39 . Similarly, healthcare providers in Kenya reported that informal payments were more likely to occur in government facilities partly due to lower wages in the public sector and lower risk of facing consequences if found charging informal payments 34 . On the contrary, a survey done with PLWHA in Cameroon showed that the incidence and amount of informal payments charged in private for-profit facilities were higher than in both public hospitals and non-profit hospitals 37 .

There were mixed findings regarding informal payments across different levels of healthcare. For example, a patient survey done in Zambia found that informal payments were more common at public hospitals (9.7%) compared to public health centers (5.8%) 48 . On the other hand, in Tanzania, informal payments were higher at government dispensaries (84.6%) compared to government health centers (35.7%) and hospitals (30.0%) 35 . In terms of amount, surveys done in Nigeria 36 and Zambia 48 showed that informal payments for malaria treatment and primary health services respectively were higher in public hospitals compared to healthcare centers. However, in Sierra Leone healthcare providers working in higher-level primary health care (PHC) facilities (community health centers and community health posts) received less income from gifts compared to those working in lower-level PHC facilities (maternal and child health posts) 47 .

System-level characteristics. Corruption in the public sector and staff transfers were reported to encourage the charging of informal payments. Some of the healthcare workers taking part in FGDs in Tanzania reported that corruption among officials at the top management level in the health sector and widespread corruption in the entire public sector promoted the charging of informal payments 45 . These findings are supported by a study done in Togo where laypeople and health workers found it more acceptable (M=4.47) for physicians to ask for informal payments when it was a common practice in other local public institutions than when the practice was rare (M=3.61) 40 .

In terms of human resource management practices, FGDs in Sierra Leone showed that routine rotations of healthcare workers across facilities led to an increase in charges with the new healthcare workers reintroducing charges for free health care 44 .

Impact of informal payments on the quality of care

Informal payments were associated with negative patient experiences with health services 31, 39 . For example, household survey data from Uganda showed that patients who paid informally were less likely to report that they were satisfied with the health services they received (AOR 0.27, 95% CI 0.24-0.29) 31 . Paying informally was associated with longer health facility visits with patients and members of the public who used government services and paid bribes reporting having spent more time to get the services needed (AOR, 2.04, 95% CI 1.89-2.22) 31 . In Tanzania, direct observation of healthcare workers during consultation showed that those who had a higher probability of accepting informal payments put in less effort for patients who were classified as weak in comparison to other healthcare workers. This indicated that they did not vary their effort based on the patient’s medical condition and therefore did not provide care based on patients’ needs 41 .

In terms of safety, in Tanzania, FGDs with healthcare workers revealed that some of their colleagues deliberately prolonged waiting times for surgeries. This was aimed at making patients desire to pay for quicker services at the public facility or the doctor’s private practice 42 . Such delays could potentially put the patient’s life at risk. Furthermore, some healthcare workers claimed that some of their colleagues provided very low-quality care, first, to hint to the patients that the quality of care would be very low if they did not give informal payments; and secondly when they felt that there was an unfair allocation of informal payments 42 .

In some Tanzanian health facilities, the provision of high-quality services was perceived to have resulted from having received informal payments. This could have forced non-corrupt healthcare workers to lower the quality of care to protect themselves from being labeled as corrupt 42 .

Impact of informal payments on equity

Demands and actual payment of informal fees disproportionately affect the poor according to rounds 3 and 5 of the Afrobarometer survey 13 . Informal payments perpetuated health inequities in access to care. Qualitative findings from Uganda, Angola, and Kenya showed that some people were forced to delay 34 or forgo care because they could not afford to pay informal payments 33, 43 , leading to unintended consequences such as unwanted pregnancies 34 . Informal payments also prevented access to specialized services at public hospitals in urban areas in Tanzania 45 . The high prevalence of informal charges at dispensaries in a rural district in Tanzania was also thought to contribute to low facility delivery rates (40%) 35 .

Respectful service delivery was dependent on an individual’s ability to pay informally 33, 43 . For example, community members in Uganda reported that the inability to pay informal payments led to healthcare workers being reluctant and impolite 43 while in Angola it led to negligence or denial of care and in extreme cases obtaining “labor on credit” by pledging to pay later 33 . In Uganda, the ability to pay informally led to obtaining cooperation from healthcare workers 43 and getting “royal treatment” in Angola 33 .

In some instances, informal payments led to the development of negative attitudes towards healthcare workers. For example, FGD participants in South Africa and Uganda reported feeling angry 31 while women in Angola reported feeling anxious when healthcare workers demanded informal payments 33 . Healthcare workers in Kenya reported that informal payments could demoralize patients, especially where they incur costs for services they are aware should be provided for free 34 . Being cognizant that informal payments were an access barrier to the poor, some healthcare workers in Tanzania and DRC reported feeling uncomfortable charging informal fees 45, 46 .

Discussion

Several studies ranging from large-scale nationally representative surveys to in-depth qualitative studies have shown that informal payments for healthcare are a common phenomenon in SSA regardless of the health service, facility level, and sector. Informal payments have also been reported to be prevalent in other regions such as Central and Eastern Europe, Asia, and South America 10, 12, 21 .

Informal payments limited access with the inability to pay associated with disrespectful care 33, 43 , delayed care-seeking 34 , and foregone care 33, 43 . Informal payments also incentivized some healthcare providers to lower their quality of care to induce patients to pay informally to receive better services 42 . The negative impact is of particular concern especially for the poor because they bear the greatest burden of informal payments 13 . Evidence from both low and high-income countries shows that informal payments are inequitable and regressive 53 . They have been reported to lead to delayed hospitalization, use of savings, borrowing, and sale of assets to acquire resources to pay informally in countries such as Tajikistan, Hungary, Poland, and Romania 53– 55 .

Mostly, healthcare workers rather than the patients initiated informal payments 13, 31, 32, 43, 51 . Patients paid informally, before care, mainly to access drugs and services, many of which should have been provided for free 32– 34, 42, 48, 51 . Some patients also made informal payments after service delivery as gifts to express gratitude 42, 50 . Most informal payments were made in cash 33, 36– 39, 42, 43, 45 rather than kind 33, 38, 46, 47 . It has been argued that it is difficult to differentiate voluntary gifts from solicited payments in the health sector. This is compounded by the fact that some patients may offer gifts out of fear of not receiving good healthcare services 8 .

From the demand side, low socio-economic status 13 and lack of awareness of user fees 32, 34, 46 were some of the key characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of paying informal payments. Other than a socio-economic disadvantage, inequities in informal payments in most African countries have been attributed to disparities in supply-side factors, such as lack of drugs, long waiting times, shortage of doctors, and regional differences within countries that disadvantage the poor forcing them to make informal payments to obtain better quality care 13 .

Some of the notable supply-side factors that increased the likelihood of paying informally were low healthcare worker salaries 32– 34, 37, 40, 45, 49, 50 , absence of official fees 39, 50 , and perceptions of widespread corruption in the public sector 40, 45 . Low and irregular healthcare worker salaries could be associated with low government spending on health. For example, per capita, government health expenditure was very low in countries with the highest prevalence of informal payments, Sierra Leone ($23), Liberia ($11), and DRC ($7) compared to countries with a low prevalence of informal payments, Botswana ($564) and Eswatini ($427) 56 . Low healthcare worker salaries have also been linked with the charging of informal payments in transition countries such as the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and Georgia due to economic difficulties that led to reduced government spending on health 8, 57– 59 . Informal payments were less likely at health facilities where patients paid official fees 39, 43 . Similar findings have been reported in transition countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Cambodia, and the Kyrgyz Republic where informal payments reduced following the introduction of co-payments alongside other initiatives 14, 60, 61 . However, user fees reduce the utilization of health services especially among the poor 62, 63 , and therefore formalization of user fees in SSA would also require the implementation of effective exemption policies for the poor and other vulnerable groups 64 . The effectiveness of formalization of user fees in reducing informal payments also warrants further investigation since the effects were not sustained in some transition countries such as Kyrgyzstan 61 .

This review identifies some distinctive features of informal payments in SSA. First, regional differences observed in the occurrence of informal payments can partly be associated with variation in the level of perceived corruption in the public sector. In countries with the highest prevalence of informal payments, a higher proportion of households reported paying a bribe to use public services compared to countries with the lowest prevalence 20 . Secondly, the presence of political instability appeared to contribute to the variation in the prevalence of informal payments in SSA. Countries with the highest prevalence of informal payments, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and DRC had also faced political instability in recent years. Constant conflict and insecurity in DRC have been linked with underfunding of public services and this might have encouraged informal charging 20 . Third, two qualitative studies revealed the existence of informal social networks that promote informal charging among and across cadres. Informal social networks have been linked to the development of strong moral obligations such as expectations to assist others within the network and to return favors that may surpass any existing formal rules 65 . If left unchecked informal social networks among healthcare workers may continue to promote the charging of informal payments.

Limitations

This review had some limitations. One, the literature search was limited to studies published in English. Secondly, due to the vast nature of grey literature, some insights on informal payments in SSA might have been missed. Thirdly, these findings can only be applied to similar low and middle-income countries with caution since factors affecting informal payments vary across contexts.

Some gaps were identified in the literature. There was limited information on the amount of informal payments incurred, variations in informal payments across various levels of care, and strategies used to tackle informal payments and their effectiveness. These are all potential areas for future research. There is also a need for further investigation on informal payments across all SSA regions because of the changes in health financing as countries strive to achieve UHC.

Policy considerations

Curbing informal payments calls for a multi-faceted approach with various short and long-term strategies because individual strategies alone cannot address the complexity of associated factors. Drivers of informal payments highlighted in this review provide some suggestions that policymakers in SSA could take into consideration and monitor to assess their effectiveness. In the short term, there is a need to enhance public awareness about official user fees, and services and population groups that are exempt from user fees. Accountability mechanisms at health facilities should also be strengthened. This could entail the establishment of safe and effective whistle-blower mechanisms for patients to report informal payment incidences and enhanced supportive supervision of health facilities. SSA governments should also increase their political commitment to fighting corruption in the health sector. In the medium to long term, there is a need for better remuneration for healthcare workers. This should be implemented alongside alternative incentive programs such as the provision of bonuses, better working conditions, and opportunities for career advancement. Increased government spending on health is also crucial as this would address healthcare worker shortages, poor working conditions, and drug stock-outs which were reported among the factors that encouraged informal payments. Equitable geographical distribution of health resources should also be ensured.

Conclusions

Informal payments are a common phenomenon in SSA, and the highest prevalence was reported in conflict and post-conflict countries and countries where corruption was perceived to be widespread in the public sector. Various patient and supply-side factors were associated with informal payments. Patients paid informally mainly to access services and drugs which were supposed to be provided for free. There was little evidence to suggest that paying informal payments led to the provision of higher quality care. Informal payments limited access and utilization of care especially among the poor and the inability to pay led to the provision of lower-quality care.

Some of the potential strategies that policymakers can consider when developing interventions to address informal payments include enhancing patient awareness about service fees, revisiting health worker incentive schemes, strengthening accountability mechanisms, and increasing government spending on health.

Data availability

Underlying data

All data underlying the results are available as part of the article and no additional source data are required.

Extended data

Harvard Dataverse: The hidden financial burden of healthcare: a systematic literature review of informal payments in Sub-Saharan Africa. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NMQCSF 22 .

This project contains the following extended data:

-

-

Characteristics of studies included in the review_table.docx

-

-

DataReadme_Kabia_et_al_review.txt

-

-

Search_strategy.docx

Reporting guidelines

Harvard Dataverse: PRISMA checklist for ‘The hidden financial burden of healthcare: a systematic literature review of informal payments in Sub-Saharan Africa’. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NMQCSF 22 .

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Funding Statement

This research was supported by Wellcome [212489, <a href=https://doi.org/10.35802/212489>https://doi.org/10.35802/212489</a>; to EK).

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

[version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 2 approved with reservations]

References

- 1. World Health Organization: Public spending on health: a closer look at global trends. Geneva. World Health Organization.2018; [Accessed 2021-10-11]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization: Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva. World Health Organization. [accessed 2021-08-12]. Reference Source [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization: Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report. Geneva. World Health Organization.2015; [accessed 2021-08-10]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization: The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance. Geneva. World Health Organization. [Accessed 2021-08-12]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 5. Normand C, Poletti T, Balabanova D, et al. : Towards universal coverage in low-income countries: what role for community financing? Health Systems Development Programme. 2006. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boccuzzi SJ: Indirect health care costs. Cardiovascular health care economics: Springer, 2003;63–79. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yousefi M, Arani AA, Sahabi B, et al. : Household health costs: direct, indirect and intangible. Iran J Public Health. 2014;43(2):202–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gaal P, Belli PC, McKee M, et al. : Informal payments for health care: definitions, distinctions, and dilemmas. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2006;31(2):251–93. 10.1215/03616878-31-2-251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stepurko T, Pavlova M, Gryga I, et al. : Empirical studies on informal patient payments for health care services: a systematic and critical review of research methods and instruments. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:273. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Khodamoradi A, Ghaffari MP, Daryabeygi-Khotbehsara R, et al. : A systematic review of empirical studies on methodology and burden of informal patient payments in health systems. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33(1):e26–e37. 10.1002/hpm.2464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Belli P, Gotsadze G, Shahriari H: Out-of-pocket and informal payments in health sector: evidence from Georgia. Health Policy. 2004;70(1):109–23. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meskarpour Amiri M, Bahadori M, Motaghed Z, et al. : Factors affecting informal patient payments: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Health Governance. 2019;24(2):117–132. 10.1108/IJHG-01-2019-0006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kankeu HT, Ventelou B: Socioeconomic inequalities in informal payments for health care: An assessment of the 'Robin Hood' hypothesis in 33 African countries. Soc Sci Med. 2016;151:173–86. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lewis M: Informal payments and the financing of health care in developing and transition countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007;26(4):984–97. 10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu T, Sun M: Informal payments in developing countries' public health sectors. Pacific Economic Review. 2012;17(4):514–24. 10.1111/j.1468-0106.2012.00597.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Killingsworth JR, Hossain N, Hedrick-Wong Y, et al. : Unofficial fees in Bangladesh: price, equity and institutional issues. Health Policy Plan. 1999;14(2):152–63. 10.1093/heapol/14.2.152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission: Sectoral perspectives on corruption in Kenya: the case of the public health care delivery. Nairobi. Kenya Anti-Corruption Commission,2010; [accessed 2021-21-01]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kankeu HT, Boyer S, Fodjo Toukam R, et al. : How do supply-side factors influence informal payments for healthcare? The case of HIV patients in Cameroon. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2016;31(1):E41–57. 10.1002/hpm.2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mæstad O, Mwisongo A: Informal payments and the quality of health care in Tanzania: results from qualitative research.2007. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 20. Coralie Pring, Vrushi J: Global corruption barometer Africa 2019: citizen's views and experiences of corruption.Berlin: Transparency International,2019. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pourtaleb A, Jafari M, Seyedin H, et al. : New insight into the informal patients’ payments on the evidence of literature: a systematic review study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):14. 10.1186/s12913-019-4647-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kabia E, Goodman C, Balabanova D, et al. : The hidden financial burden of healthcare: a systematic literature review of informal payments in Sub-Saharan Africa.Harvard Dataverse, V1.2021. 10.7910/DVN/NMQCSF [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: CASP Qualitative research checklist.2018; [accessed 2021-1-20]. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 24. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. : Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ open. 2016;6(12):e011458. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ryan R, Consumers C, Communication Review Group : Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group: data synthesis and analysis. 2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 26. Srivastava A, Thomson SB: Framework analysis: a qualitative methodology for applied policy research. 2009. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rispel LC, De Jager P, Fonn S: Exploring corruption in the South African health sector. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(2):239–49. 10.1093/heapol/czv047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kagotho N, Bunger A, Wagner K: "They make money off of us": a phenomenological analysis of consumer perceptions of corruption in Kenya’s HIV response system. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):468. 10.1186/s12913-016-1721-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bouchard M, Kohler JC, Orbinski J, et al. : Corruption in the health care sector: A barrier to access of orthopaedic care and medical devices in Uganda. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2012;12(1):5. 10.1186/1472-698X-12-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaiser JL, McGlasson KL, Rockers PC, et al. : Out-of-pocket expenditure for home and facility-based delivery among rural women in Zambia: a mixed-methods, cross-sectional study. Int J Womens Health. 2019;11:411–430. 10.2147/IJWH.S214081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paredes-Solís S, Andersson N, Ledogar RJ, et al. : Use of social audits to examine unofficial payments in government health services: experience in South Asia, Africa, and Europe. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S12. 10.1186/1472-6963-11-S2-S12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lange IL, Kanhonou L, Goufodji S, et al. : The costs of ‘free’: Experiences of facility-based childbirth after Benin's caesarean section exemption policy. Soc Sci Med. 2016;168:53–62. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pettersson KO, Christensson K, Da Gloria Gomes De Freitas E, et al. : Strategies applied by women in coping with ad-hoc demands for unauthorized user fees during pregnancy and childbirth. A focus group study from Angola. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(3):224–46. 10.1080/07399330601179885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tumlinson K, Gichane MW, Curtis SL: "If the Big Fish are Doing It Then Why Not Me Down Here?": Informal Fee Payments and Reproductive Health Care Provider Motivation in Kenya. Stud Fam Plann. 2020;51(1):33–50. 10.1111/sifp.12107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kruk ME, Mbaruku G, Rockers PC, et al. : User fee exemptions are not enough: out-of-pocket payments for 'free' delivery services in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(12):1442–51. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02173.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Onwujekwe O, Dike N, Uzochukwu B, et al. : Informal payments for healthcare: differences in expenditures from consumers and providers perspectives for treatment of malaria in Nigeria. Health Policy. 2010;96(1):72–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kankeu HT, Boyer S, Fodjo Toukam R, et al. : How do supply-side factors influence informal payments for healthcare? The case of HIV patients in Cameroon. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2016;31(1):E41–E57. 10.1002/hpm.2266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Akwataghibe N, Samaranayake D, Lemiere C, et al. : Assessing health workers’ revenues and coping strategies in Nigeria—a mixed-methods study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):387. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hunt J: Bribery in health care in Uganda. J Health Econ. 2010;29(5):699–707. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2010.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kpanake L, Dassa SK, Mullet E: Is it acceptable for a physician to request informal payments for treatment? Lay people’s and health professionals’ views in Togo. Psychol Health Med. 2014;19(3):296–302. 10.1080/13548506.2013.819438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lindkvist I: Informal payments and health worker effort: a quantitative study from Tanzania. Health Econ. 2013;22(10):1250–71. 10.1002/hec.2881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mæstad O, Mwisongo A: Informal payments and the quality of health care: mechanisms revealed by Tanzanian health workers. Health Policy. 2011;99(2):107–15. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McPake B, Asiimwe D, Mwesigye F, et al. : Informal economic activities of public health workers in Uganda: implications for quality and accessibility of care. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(7):849–65. 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00144-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pieterse P, Lodge T: When free healthcare is not free. Corruption and mistrust in Sierra Leone's primary healthcare system immediately prior to the Ebola outbreak. Int Health. 2015;7(6):400–4. 10.1093/inthealth/ihv024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stringhini S, Thomas S, Bidwell P, et al. : Understanding informal payments in health care: motivation of health workers in Tanzania. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7(1):53. 10.1186/1478-4491-7-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maini R, Hotchkiss DR, Borghi J: A cross-sectional study of the income sources of primary care health workers in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Hum Resour Health. 2017;15(1):17. 10.1186/s12960-017-0185-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bertone MP, Lagarde M: Sources, determinants and utilization of health workers’ revenues: evidence from Sierra Leone. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(8):1010–9. 10.1093/heapol/czw031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Masiye F, Kaonga O, Banda CM: Informal payments for primary health services in Zambia: Evidence from a health facility patient exit survey. Health Policy OPEN. 2020;1:100020. 10.1016/j.hpopen.2020.100020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Binyaruka P, Balabanova D, McKee M, et al. : Supply-side factors influencing informal payment for healthcare services in Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2021;36(7):1036–1044. 10.1093/heapol/czab034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hahonou EK: Juggling with the norms: Informal payment and everyday governance of health care facilities in Niger. 2015. 10.4324/9781315723365-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Odour C: Integrity in the public health sector service delivery in Busia county. Nairobi: Institute of Economic Affairs;2013. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 52. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. : The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Gaál P, Jakab M, Shishkin S, et al. : Strategies to address informal payments for health care. Implementing health financing reform: lessons from countries in transition.Copenhagen: World Health Organization.2010:327–60. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gaal PA: Informal payments for health care in Hungary.London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine;2004. 10.17037/PUBS.04646519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jakab M, Kutzin J: Improving financial protec-tion in Kyrgyzstan through reducing informal payments.WHO Health Policy Analysis Research Paper.2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Micah AE, Chen CS, Zlavog BS, et al. : Trends and drivers of government health spending in sub-Saharan Africa, 1995– 2015. BMJ global health. 2019;4(1):e001159. 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lewis MA: Who is paying for health care in Eastern Europe and Central Asia?World Bank Publications;2000. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ensor T: Informal payments for health care in transition economies. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(2):237–46. 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00007-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Thompson R, Witter S: Informal payments in transitional economies: implications for health sector reform. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2000;15(3):169–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Barber S, Bonnet F, Bekedam H: Formalizing under-the-table payments to control out-of-pocket hospital expenditures in Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(4):199–208. 10.1093/heapol/czh025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Falkingham J, Akkazieva B, Baschieri A: Trends in out-of-pocket payments for health care in Kyrgyzstan, 2001– 2007. Health Policy Plan. 2010;25(5):427–36. 10.1093/heapol/czq011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Nanda P: Gender dimensions of user fees: implications for women’s utilization of health care. Reprod Health Matters. 2002;10(20):127–34. 10.1016/s0968-8080(02)00083-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pokhrel S, Hidayat B, Flessa S, et al. : Modelling the effectiveness of financing policies to address underutilization of children's health services in Nepal. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(5):338–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Hussman K: How to Note: Addressing Corruption in the Health Sector.London, UK: Department for International Development,2010:2–3. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 65. Baez-Camargo C, Passas N: Hidden agendas, social norms and why we need to re-think anti-corruption.2017. Reference Source [Google Scholar]