Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common cancers of the digestive tract, and patients with advanced-stage cancer have poor survival despite the use of multidrug conventional chemotherapy regimens. Intra-tumor heterogeneity of cancerous cells is the main obstacle in the way to effective cancer treatments. Therefore, we are looking for novel approaches to eliminate just cancer cells including nanoparticles (NPs). PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were successfully synthesized through a portable method. The characterization of transmission electron microscopy (TEM), Fourier-Transformed infrared spectrometer, and X-ray powder diffraction have further proved successful preparation of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. NIR irradiation was used to test the photothermal properties of NPs and an infrared camera was used to record their temperature. The direct effects of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on colorectal cancer cell DLD1 were assessed using CCK8, plate clone, transwell, flow cytometry, and western blotting in CRC cell. The effect of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on neoplasm growth in nude mice was evaluated in vivo. This study demonstrated that PPy@ Fe3O4 NPs significantly inhibit the growth, migration, and invasion and promote ferroptosis to the untreated controls in colorectal cancer cells. Mechanical exploration revealed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibit the multiplication, migration, and invasion of CRC cells in vitro by modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Importantly, Ferroptosis inhibitors Fer-1 can reverse the changes in metastasis-associated proteins caused by NPs treatment. Collectively, our observations revealed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were blockers of tumor progression and metastasis in CRC. This study brought new insights into bioactive NPs, with application potential in curing CRC or other human disorders.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, nanoparticles, metastasis, NF-κB, ferroptosis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks among the most common and devastating diseases of the digestive system globally (Bray et al., 2018; Siegel et al., 2021). There is no effective regime against this aggressive malignancy besides early surgical resection (Brenner et al., 2014). When patients are diagnosed with colorectal cancer, 15%–25% have liver metastases, and another 15%–25% develop them after radical resection of the primary tumor (Engstrand et al., 2018). However, radical resection of liver metastases is not possible in 80%–90% of cases (Modest et al., 2019). Among the reasons for this grim prognosis are the lack of obvious symptoms and reliable biomarkers for early diagnosis, as well as aggressive metastatic spread that leads to a poor response to treatment. Metastatic disease occurs in approximately 50% of diagnosed patients (Xu et al., 2019; Rebersek, 2020). Patients with advanced and metastatic cancer are generally treated with chemotherapy (Fan et al., 2021). The combination of radiation with chemotherapy is another option for treating unresectable, metastatic cancers (Koppe et al., 2005). Even so, both approaches are mainly aimed at improving survival rates and reducing symptoms of cancer (Aggarwal et al., 2013; Biller and Schrag, 2021).

With the rapid development of nanotechnology, nanoparticles (NPs) have provided a new approach for studying tumor therapies in recent years (Guan et al., 2022a; Zheng et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2022b). Nanomaterials refer to materials with at least one dimension ranging from 1 to 100 nm (Zheng et al., 2022). Due to their special dimensions, they have different optical, electromagnetic, biological, and thermal properties than general materials, making them more plastic (Sun et al., 2014; Enriquez-Navas et al., 2015; Duan et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). The field has broad application prospects. Currently, nanomaterials treatment for cancer is mainly aimed at direct destruction of tumors, but in clinical treatment, high mortality rates of cancer are caused by the proliferation and metastasis of tumors, not the primary tumor site (Jiang et al., 2015; El-Toni et al., 2016). At present, the killing of tumors by nanoparticles mainly revolves around the photothermal properties and chemodynamic therapy of nanomaterials (Baek et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2019), and nanoparticles’ direct effect on tumor cells has been little studied. Revealing the specific mechanism of nanoparticles’ effects on tumor cells is beneficial to promote the further application of nanoparticles in the human body.

Polypyrrole (PPy) is a kind of organic photothermal agent and photosensitizer, which can not only ablate cancer cells under infrared irradiation, and improve the effect of chemotherapy, but also has good biocompatibility, which can regulate cell adhesion, migration, protein secretion, and DNA synthesis as well as other processes under electric stimulation (Zhou et al., 2017; Liang et al., 2021; Miar et al., 2021). Human bodies require iron (Fe) as an essential trace element. Early studies found that the concentration of Fe in the body is negatively correlated with colorectal cancer. Therefore, people have high hopes for Fe treatment of tumors (Torti et al., 2018; Torti and Torti, 2020). There are also numerous studies that prove Fe supplementation can inhibit colorectal cancer development (Aksan et al., 2021; Phipps et al., 2021; Ploug et al., 2021). Whereas, some scholars believe that excess iron contributes to oxidative stress-induced colon damage and amplifies oncogenic signals. Therefore, the clinical application of Fe-containing drugs is limited (Padmanabhan et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2018). It is possible to deliver nanoparticles to tumors through enhanced permeability and retention effect (EPR), and decompose iron ions directly in the tumor-specific microenvironment, which can avoid harming the normal colon.

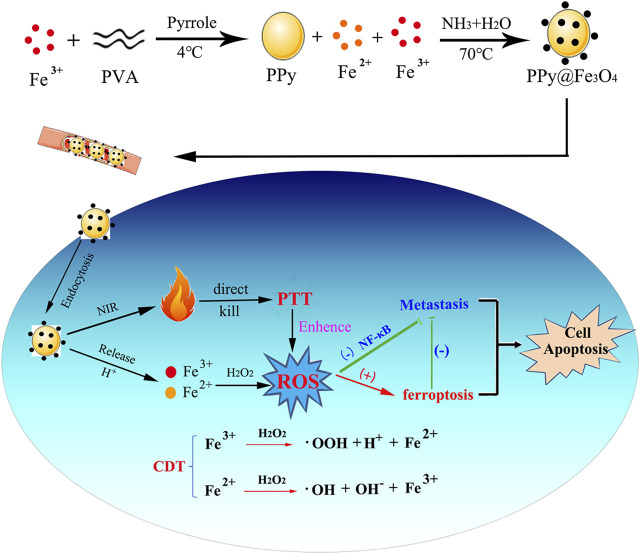

Our study design and manufacture a novel composite nanomaterial PPy@Fe3O4 and demonstrate that it can directly kill tumors through photothermal therapy (PPT) and chemodynamic therapy (CDT). As well as evaluating the basic properties and biosafety of PPy@ Fe3O4 NPs, we observed their effects on colorectal cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion in vivo and in vitro (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Scheme of the synthesis process and therapeutic mechanism of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs

Dissolve 0.75 g of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) in 10 ml of deionized water. Heated to 95°C, after dissolving PVA, 0.373g ferric chloride powder (FeCl3 2.30 mmol) was added to the above solution and stirred magnetically for an hour. Then the mixed solution was kept at 4°C and 69.2 μl pyrrole monomer (0.9970 mmol) was added slowly. After 4 h of stirring, the mixture was poured into a bowl. A dark green solution was produced, which indicated the successful synthesis of polypyrrole NPs. Then, 2.5 ml of the reaction solution was directly removed from the above steps, and then 15 ml of deionized water and 2 ml of ethanol were evenly mixed. Under the condition of full agitation, the temperature was rapidly heated to 70°C, and 1 ml of 1.0wt% ammonia solution was immediately dropped. After 30 min, inject another 1 ml 1.0wt% ammonia solution and keep the mixture at the same temperature for another 30 min. Centrifugation by separation (11,000 RPM; 50 min) PPy@Fe3O4 nanoparticles were collected and centrifuged (11,000 RPM; 50 min), washed three times with deionized water to remove impurities, and collected and dispersed in deionized water.

Characterization of PPy@ Fe3O4 NPs and photothermal effect evaluation

The morphologies of NPs were evaluated via transmission electron microscopy (TEM). In order to determine the characteristics of NPs and their crystal structures, Fourier-Transformed Infrared (FTIR) spectrometers and X-ray powder diffraction methods were used. We then irradiated PPy@ Fe3O4 NPs with NIR lasers at different wavelengths (100, 200, and 400 μg/ml) at different concentrations. A thermal imaging camera was used to monitor and record the temperature changes of the solution during the heating and cooling process to calculate the photothermal conversion efficiency (η).

Culture of the cancer cell lines

DLD1-1, SW480, and FHC colorectal cancer cell lines were purchased from ATCC. DLD1 and SW480 were colorectal cancer cells, and FHC was a normal colorectal epithelial cell. All cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, United States). All media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and cells were grown in an incubator at 37°C and supplied with 5% CO2.

Biosafety and flow cytometry analysis

In advance, DLD1, SW480, and FHC cells were plated in 96-well plates at 1*104 cells per well and cultured for 24 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. At various concentrations, PPy@Fe3O4 was added to the culture media for 24 h, followed by 18 h of incubation. In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, relative cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, Yeasen, China).

Transwell migration assay

Transwell migration assays were conducted in Corning-Costar migration chambers with a pore size of 8 mm for studying CRC cell migration in transfected suspensions. As soon as possible, transfected cells were seeded into an FBS-free medium and conditioned DMEM containing 10% FBS was poured into the lower chamber. In the following 48 h, we removed the cells on the upper membrane surface and fixed and stained the cells on the bottom membrane surface with methanol and crystal violet. We photographed cells from five random fields (×40 magnifications) under the light microscope.

Western blotting

Equal amounts of samples were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. Blocking membranes with 5% non-fat milk in TBST for 1 h, primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C, followed by secondary antibodies at room temperature for 90 min. The immunoreactive bands were visualized using a ChemiLucent ECL kit (Millipore) and the ImageJ program (National Institutes of Health).

Determination of intracellular ROS

In accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, chloro-dihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) was used to determine intracellular ROS. Briefly, DLD1 cells were incubated with NPs (200 µg/ml−1) at pH 6.5 for 3.5 h, followed by 30 min of incubation with H2O2 (100 mM, 200 µl). The cells were placed on an ice box at 4°C. Then the medium was replaced by 1 ml DCFH-DA (10 µM).

Animal experiments

All experiments on animals were conducted in accordance with “China National Standards for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Renji Hospital Affiliated with Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine. In order to establish colorectal cancer xenograft model, 20 male BALB/c athymic nude mice (4 weeks old) were randomly divided into four groups (n = 5) and injected subcutaneously with 1.0*107 stable colorectal cells DLD1. A variety of intravenous preparations were administered: Control (groups 1), NIR(groups 2), NPs (200 µg/ml−1) (groups 3), NIR + NPs (groups 4). We used an 808 nm laser (1.0 W cm−2) to irradiate Groups 2 and 4 for 10 min respectively after 8 h and monitored temperature change by a thermal imaging camera. Prior to the mice being killed, tumor growth was monitored and measured with micrometer calipers every other day. After 28 days of treatment, immediately after harvest, organs and tumors were preserved in paraformaldehyde for further IHC testing and hematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E-stained).

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed with the χ2 test or the Student's t-test (two-tailed unpaired). All the data were analyzed using Origin and Graphpad. Moreover, p < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

Results

Construction and physical characterization of PPy@Fe3O4

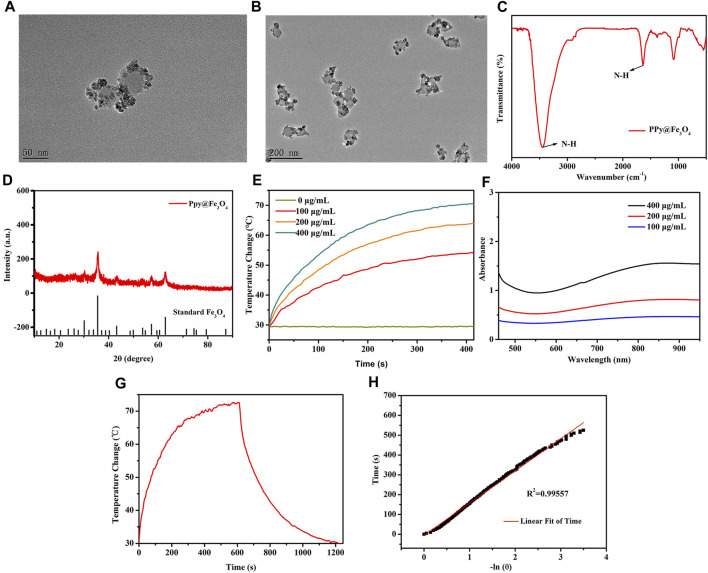

The PPy nanoparticles were firstly prepared, followed by ammonia addition at 70°C to convert Fe ions into Fe3O4 crystals. The Fe3O4 crystals were dispersed on the surface of PPy nanoparticles, forming PPy@Fe3O4 NPs with a size of ∼70 nm, as shown in Figures 2A,B. Each PPy nanoparticle incorporated many Fe3O4 crystals. The FTIR spectrum confirmed the successful formation of PPy by showing the characteristic absorption peaks (Figure 2C). Fe3O4 crystal structures were confirmed by X-ray diffractograms (XRD) of NPs (Figure 2D). These results illustrated that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs have been successfully synthesized.

FIGURE 2.

The characterization and photothermal properties of the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs. (A,B) High and Low TEM images of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs; (C) FTIR spectra of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs; (D) XRD spectra of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs; (E) UV-Vis-NIR absorption spectra of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs at different concentrations; (F) Temperature change curve with various concentrations of NPs; (G) Temperature curve of rising with irradiation and naturally cooling; (H) Linear regression curve of cooling process (red).

Since PPy was introduced to Fe3O4 NPs, they demonstrated a strong and broad absorption spectrum from the visible to near-infrared (Figure 2E). As the NPs concentration increase, the temperature also increases gradually under NIR irradiation (Figure 2F). Based on the temperature changes of the solution during heating/cooling process, we determined the photothermal conversion efficiency (ŋ value) of NPs (Figures 2G,H). The ŋ value was significantly higher than that of traditional PPT agents at 52%. The above results showed that the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs have excellent photothermal effects, which endowed good performance for PTT.

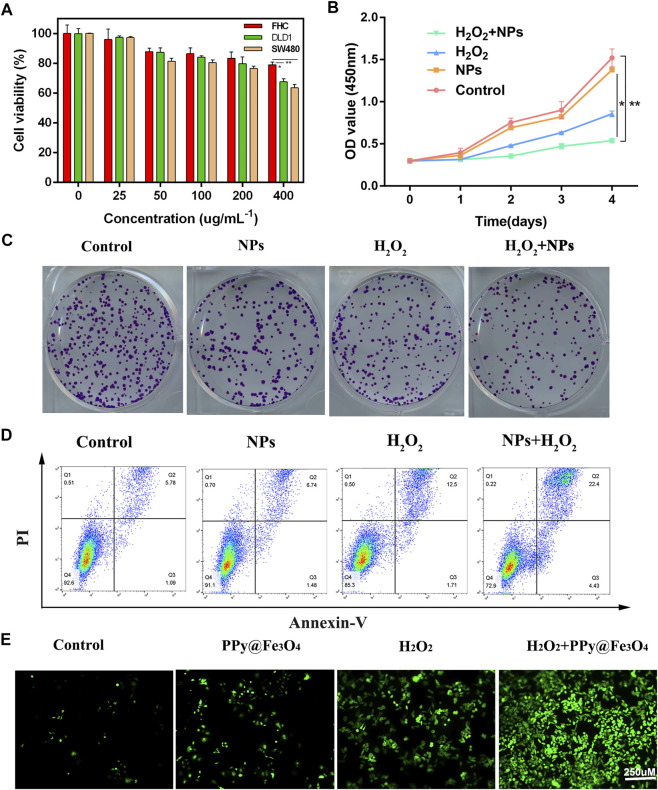

PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibited growth and produced ROS in vitro

Biological applications of nanoparticles depend on their good biocompatibility. To evaluate its cytotoxicity, we used standard CCK-8 methods in DLD1, SW480, and FHC cells. As shown in Figure 3A, NPs exhibited excellent biocompatibility, except for NPs (400 ug/ml−1), with mildly stronger cytotoxicity due to their chemodynamic reactions. To simulate the tumor microenvironment in vitro, we added the appropriate amount of hydrogen peroxide during cell treatment. Therefore, colorectal cancer cells were divided into 4 groups: 1) Control, (b)H2O2, (C) NPs, (d)NPs + H2O2. DLD1 cells proliferation was significantly decreased by treatments with NPs and H2O2 in plating colony and CCK8 assays demonstrating that PPy@Fe3O4 functions biologically in colorectal cancer (Figures 3B,C). For cell apoptosis assay, NPs and H2O2 treated group promoted apoptosis in DLD1 cells (Figure 3D). To verify the ROS production of NPs in DLD1, we observe dichloro-dihydrofluorescein diacetate staining (DCFH-DA) under confocal microscopic conditions, ROS levels were significantly augmented in cells treated with NPs and H2O2, indicating a promoting effect on ROS generation (Figure 3E).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs on regulating colorectal cancer cell growth, clone formation apoptosis and ROS generation. (A) Cell viability of the DLD1, SW480 and FHC cells after co-culture with NPs at different concentrations. (B) Cell viability CCK-8 assay in different groups. (C) Colony formation assay. Duplicated cells were subjected to the tumour cell colony formation assay in different groups. (D) Flow cytometric apoptosis assay. Colorectal cancer cell lines DLD1 were treated with H2O2, NPs, NPs + H2O2 or control, respectively, and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis. (E) Fluorescence images of DLD1 cells with various groups (Control, H2O2, NPs and NPs + H2O2). Scale bar: 250 µm **p < 0.01.

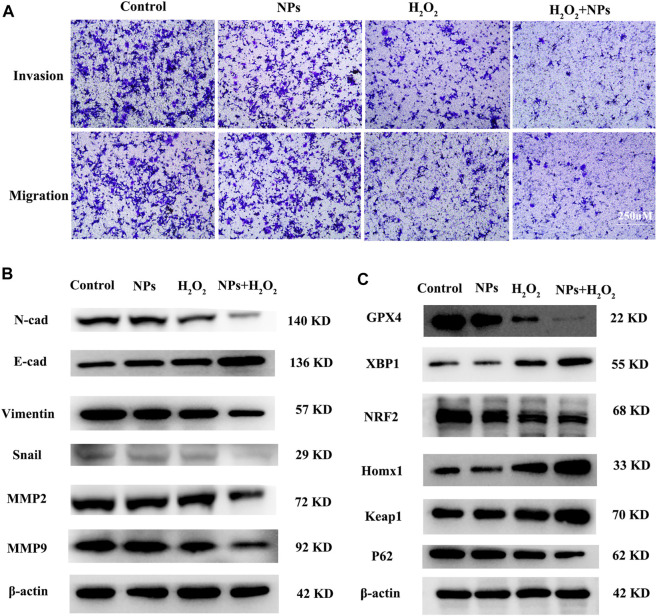

PPy@Fe3O4 NPs suppressed metastasis and promoted ferroptosis in CRC cells

Transwell migration and invasion assays indicated that NPs and H2O2 treated group decreased the ability of migration and invasion (Figure 4A). Since epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) plays a vital role in tumorigenesis, the relationship between NPs and EMT in CRC cells warranted further investigation. EMT biomarkers were used to identify whether NPs treated in CRC were related to EMT. The WB results showed that NPs inhibited the expression of the mesenchymal markers N-cadherin, Vimentin, Snail, MMP2, and MMP9, but induced the expressions of the epithelial marker E-cadherin (Figure 4B). Therefore, we inferred that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibited tumor metastasis through inhibiting the EMT process.

FIGURE 4.

PPy@Fe3O4 NPs suppress cell migration and invasion, and promote cell ferroptosis in vitro. (A) Transwell migration and invasion assays of DLD1 cell with different treatment groups. (B) WB assays showed that metastasis-related proteins (E-Cadherin, N-Cadherin,Snail, MMP2, MMP9 and Vimentin) expression changed in different groups. (C) Ferroptosis-related proteins (GPX4, XBP1, NRF2, HOMX1 and Keap1) expression changed in the control group and other treated groups.

In addition, studies also shown that the role of ROS in tumor cells is closely related to ferroptosis (Su et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2021a), and PPy@ Fe3O4 nanomaterials not only generate ROS in tumors, but also the constant conversion of Fe2+ and Fe3+ through the Fenton reaction, which also affects the iron ions metabolism. We speculated that NPs are associated with ferroptosis in tumor cells. Our data showed that PPy@Fe3O4 induced the expression of Xbp1, Homx1, and Keap1, but inhibited the expressions of GPX4 and NRF2 (Figure 4C). In addition, hydrogen peroxide has been reported to induce ferroptosis, which is consistent with our findings. Therefore, we inferred that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs can promote ferroptosis in CRC cells.

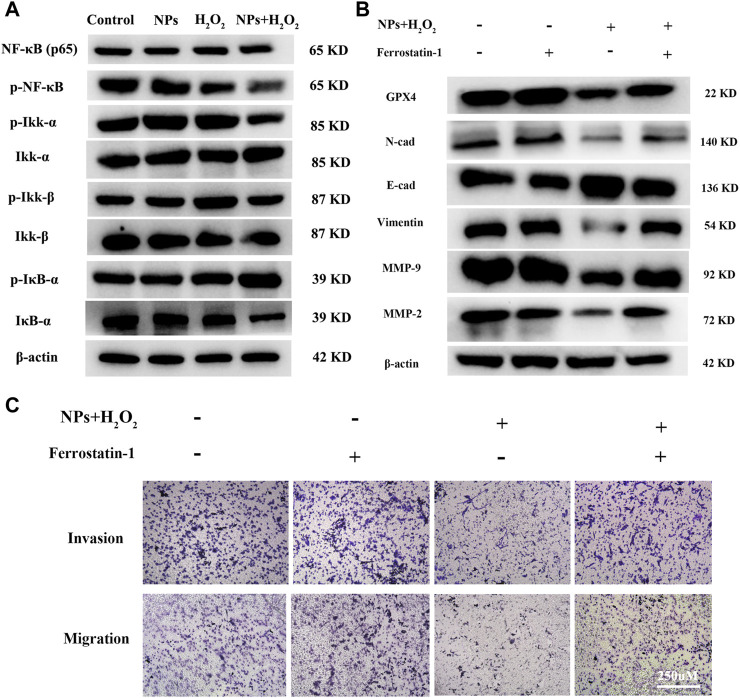

PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibited EMT via the NF-κB signaling pathway

NF-κB is involved in many cancer-related processes, including cell proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and metastasis in colorectal cancer (Vaiopoulos et al., 2013; Patel et al., 2018). A previous study reported excessive ROS can reduce NF-κB activation by inhibiting IκB protein degradation (Morgan and Liu, 2011). So we hypothesized whether PPy@Fe3O4 inhibits tumor cell metastasis by inhibiting NF-κB signaling. As part of this study, we measured the expression and activity of NF-κB in CRC cells treated with NPs. There was a decrease in the levels of p-IKKα and p-IKKβ in DLD1, as well as an increase in the amounts of p-IκBα after treatment with NPs and H2O2. P65 levels did not change significantly, but phospho-p65 expression decreased. We discovered that the expression of phosphorylated (p)p65, p-IKKα, p-IKKβ, and IκBα, which are essential for activating the NF-κB signaling pathway, were downregulated by NPs with H2O2 in DLD1 cells (Figure 5A).

FIGURE 5.

PPy@Fe3O4 NPs suppress CRC cells metastasis by promoting cell ferroptosis and inhibiting NF-κB signaling pathway. (A) Western blot. Colorectal cancer cell line DLD1 was treated with various groups (Control, H2O2, NPs and NPs + H2O2), and then subjected to Western blot analysis of the key proteins of the NF-KB signaling pathway (Ikk-β, p-Ikk-β, ikk-α, p-Ikk-α, NF-κβ, p-NF-κβ, IκB-α and p-IκB-α). (B) Effects of the ferroptosis inhibitor Ferrostatin-1 on PPy@Fe3O4 NPs-induced metastasis-related proteins expression. (C) Transwell showed that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs-induced cell migration and invasion were abolished after addition of the ferroptosis inhibitor Ferrostatin-1 in CRC cell.

Some studies have reported that there is an interaction between EMT and ferroptosis (Chen et al., 2020; Guan D. et al., 2022). GPX4, which is a negative regulator of ferroptosis, knockdown can enhance tumor cell oncogenic and metastatic activity (Huang et al., 2022). We suppose ferroptosis was increased after PPy@Fe3O4 treatment, and the metastatic ability of colorectal cancer cells was inhibited by increased GPX4 expression. After inhibition of tumor cell ferroptosis with ferroptosis inhibitors Ferrostatin-1 (Fer-1), western-blot analysis and transwell assays revealed increased metastatic potential of colorectal cancer cells, and the expression of EMT-related proteins was distinctly altered, with N-cadherin, Vimentin, Snail, MMP2 and MMP9 upregulated and E-cadherin downregulated (Figures 5B,C). These results demonstrated that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibit CRC cells’ metastasis by promoting cell ferroptosis and inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway.

In vitro cell experiment

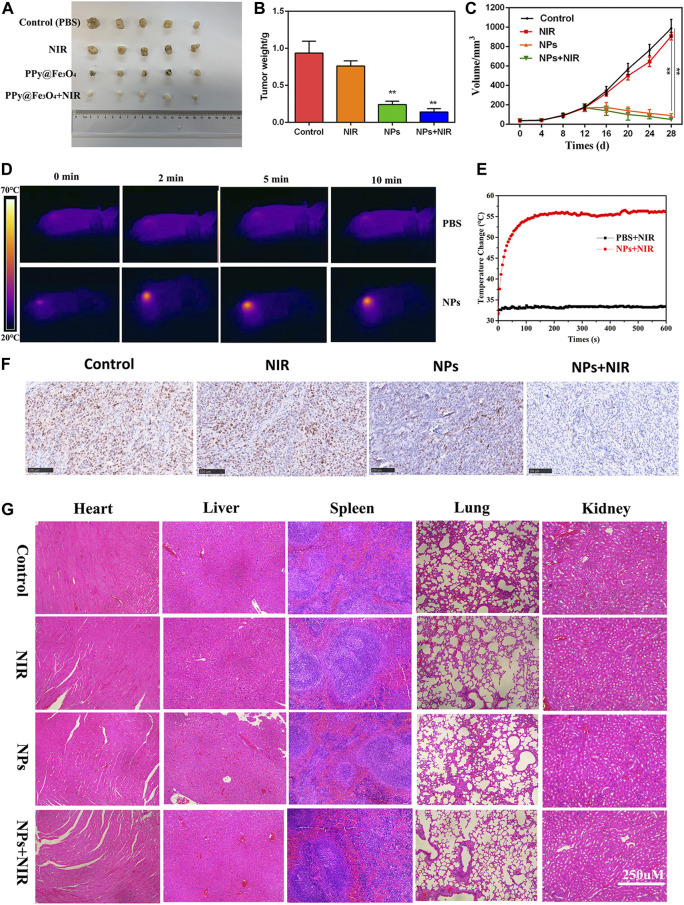

In order to investigate the roles of PPy@Fe3O4 NPs in vivo, a nude mouse xenograft model of colorectal cancer was constructed. Tumor volume was monitored every other day throughout the experiment. As a result of NPs treatment, tumor growth was significantly inhibited (Figures 6A–C). There was no difference in tumor growth between the NIR and control groups, demonstrating that NIR alone cannot inhibit tumor growth. However, due to the synergistic effects of PTT and CDT, the tumor growth in the NPs + NIR group was significantly inhibited. NIR group mice were irradiated with an 808 nm laser while their infrared thermal image and temperature were recorded simultaneously. Laser irradiation rapidly increased the temperature of the tumor in the NPs group to 55°C. It has been reported that apoptosis and necrosis of cancer cells can be induced when the temperature around the tumor is above 42°C (Sun et al., 2019). In contrast, the control group only experienced a very weak rise, less than 35°C (Figures 6D,E). In the colorectal tumor model, Ki-67, a marker of cell proliferation, was significantly downregulated in NPs + NIR groups after IHC analysis (Figure 6F). These results explicitly demonstrated that NPs with NIR could effectively prevent tumor growth in vivo. H&E staining of various treatment groups was carried out for the purpose of assessing the biosafety of NPs. According to the data, neither the control group nor other treatment groups showed obvious organ damage (Figure 6G), which further validated the PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were safe.

FIGURE 6.

Anti-tumour activity of PPy@ Fe3O4 NPs in nude mouse tumour cell xenografts. (A) Images of subcutaneous xenograft tumors of DLD1 cells. (B) The final tumor weight of DLD1 cells was shown. (C) The tumor volume and change of different groups. (D) The temperature change and (E) infrared thermal imaging of the mice injected with PBS, NPs under laser irradiation. (F) Ki67 staining of the tumors in the control group and other treated groups. (scale bar: 100 μm). (G) H&E staining of the main organs from the control and treatment groups. (scale bar: 250 μm). **p < 0.01.

Discussion

PPy@Fe3O4 NPs were successfully synthesized by an facile method. They exhibited an excellent photothermal effect and could produce abundant ROS for CDT in the tumor microenvironment. Furthermore, NPs are adequate to modulate cellular response on their own (Setyawati and Leong, 2017; Cen et al., 2021). First, we used CCK8 to detect the viability of normal cells and tumor cells exposed to different concentrations of NPs to judge the biosafety of NPs. We then demonstrated in vitro that NPs can restrain the accretion and metastasis of CRC cells and promote ferroptosis. Finally, we found that NPs inhibit CRC cells growth by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting NF-κB pathway. In vivo experiment results further confirmed the inhibition of NPs on tumor growth.

Our team has long been committed to the practical application of photothermal technology. PTT and CDT of nanoparticles have enormous potential in cancer treatment (Huang et al., 2019; Zheng et al., 2021). CDT/PTT has demonstrated to be highly effective and relatively safe, and it can directly ablate cancer cells as well. Additionally, photothermal effects during PTT can speed up the Fenton-based process’ reaction rate and enhance CDT (Yu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022). With the development of nanotechnology, various targeted and multifunctional nanoparticles have been reported, which can deliver drugs and directly or indirectly activate the immune system to kill cancer cells (Hooftman and O'Neill, 2022; Luo et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). Although some nanomaterials have been used clinically in recent years, most of them have not achieved ideal clinical effects. In monotherapy, the continuing effects and biosafety of NPs on tumor cells require further study.

There is a new type of cell death called ferroptosis that differs from apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy, which are all iron-dependent cell deaths (Chen et al., 2021b; Tang et al., 2021). As a metabolic disorder resulting from iron, ROS, and polyunsaturated fats, ferroptosis is characterized by deranged iron metabolism. Iron, lipid, and energy metabolism play a significant role in the sensitivity of tumor cells to ferroptosis (Lee et al., 2020; Li and Li, 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). Nanomedicine has become a new direction in the application of ferroptosis. Ultra-small PEG@ SiO2 NPs induce ferroptosis and limit tumor growth in starving cancer cells by mediating iron overuptake (Ma et al., 2017). In addition, p53 plasmid-coated metal-organic network NPs lead to ferroptosis and tumor growth inhibition by blocking GSH synthesis (Zheng et al., 2017). In our study, we found that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs restrained CRC cells’ growth and metastasis by promoting cell ferroptosis, and the exact mechanism needs to be further studied.

In normal physiology processes, NF-κB pathway coordinates the inflammatory process and participates in the regulation of various steps of the cell cycle and survival (DiDonato et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017). Binding to an inhibitory protein in the cytoplasm keeps it inactive. In response to the signal, its inhibitor is phosphorylated and proteolytically degraded, and NF-κB is translocated vigorously to the nucleus, where it promotes transcription of target genes (Vaiopoulos et al., 2013). Numerous pieces of evidence indicate that NF-κB has a key role in the initiation and propagation of CRC. Furthermore, the NF-κB signaling activation has been identified as a recognized event in the EMT process (Min et al., 2008). Liu et al. found that DCLK1 facilitates EMT via the NF-κB signaling pathway in CRC cells (Liu et al., 2018). Moreover, previous studies have shown that NF-κB regulates Vimentin and Snail expression directly by binding their promoters (Wu et al., 2004), which is consistent with our WB results. Herein, our study demonstrated that PPy@Fe3O4 NPs inhibit CRC cell proliferation and metastasis by blocking the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Overall, we exhibited the suppressive role of NPs in the progression of CRC in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, our results revealed that PPy@Fe3O4 has an excellent photothermal effect and photostability under NIR irradiation. PPy@Fe3O4 NPs can not only be used for PPT and CDT but also can inhibit the growth and metastasis of tumor cells by regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway. Therefore, a therapeutic strategy based on PPy@Fe3O4 NPs to attenuate tumor development may be a potential approach for CRC treatment.

Conclusion

PPy is a common non-toxic conductive polymer that is slightly soluble in water, other nanomaterials loaded with PPy can significantly improve their photothermal effect. In this study, we developed an NPs (PPy@Fe3O4) based on PPy to enhance the effect of PTT/CDT in CRC. The NPs displayed a high photothermal conversion efficiency of 52% because of PPy, which was much higher than that of traditional PPT agents. Besides, NPs were responsively decomposed in the tumor microenvironment to release the Fe ions of different valences, which promoted the generation of toxic OH from H2O2 for CDT. More importantly, we discovered a direct effect of NPs on colorectal cancer cells. PPy@Fe3O4 NPs can inhibit the growth and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells through the NF-κB signaling pathway, and promote cell ferroptosis.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Scientific Center Project (No. 62088101) and the Industry-University-Research Innovation Fund in Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (No. 2018A01013).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee of Renji Hospital Affiliated with Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine.

Author contributions

ZY and ST: Wrote the manuscript, In vivo and in vitro models. CW and ZW: Data curation, methodology; YY and SW: supervision, project administration; KJ: funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Aggarwal C., Meropol N. J., Punt C. J., Iannotti N., Saidman B. H., Sabbath K. D., et al. (2013). Relationship among circulating tumor cells, CEA and overall survival in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 24 (2), 420–428. 10.1093/annonc/mds336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksan A., Farrag K., Aksan S., Schroeder O., Stein J. (2021). Flipside of the coin: Iron deficiency and colorectal cancer. Front. Immunol. 12, 635899. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.635899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek S., Singh R. K., Khanal D., Patel K. D., Lee E. J., Leong K. W., et al. (2016). Smart multifunctional drug delivery towards anticancer therapy harmonized in mesoporous nanoparticles. Nanoscale 7 (34), 14191–14216. 10.1039/c5nr02730f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biller L. H., Schrag D. (2021). Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: A review. JAMA 325 (7), 669–685. 10.1001/jama.2021.0106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R. L., Torre L. A., Jemal A. (2018). Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 68 (6), 394–424. 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner H., Kloor M., Pox C. P. (2014). Colorectal cancer. Lancet 383 (9927), 1490–1502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen D., Ge Q., Xie C., Zheng Q., Guo J., Zhang Y., et al. (2021). ZnS@BSA nanoclusters potentiate efficacy of cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Mat. 33 (49), e2104037. 10.1002/adma.202104037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P., Li X., Zhang R., Liu S., Xiang Y., Zhang M., et al. (2020). Combinative treatment of β-elemene and cetuximab is sensitive to KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Theranostics 10 (11), 5107–5119. 10.7150/thno.44705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Kang R., Kroemer G., Tang D. (2021b). Broadening horizons: The role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 18 (5), 280–296. 10.1038/s41571-020-00462-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Li J., Kang R., Klionsky D. J., Tang D. (2021a). Ferroptosis: Machinery and regulation. Autophagy 17 (9), 2054–2081. 10.1080/15548627.2020.1810918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDonato J. A., Mercurio F., Karin M. (2012). NF-κB and the link between inflammation and cancer. Immunol. Rev. 246 (1), 379–400. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01099.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan X., Chan C., Lin W. (2019). Nanoparticle-Mediated immunogenic cell death enables and potentiates cancer immunotherapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (3), 670–680. 10.1002/anie.201804882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Toni A. M., Habila M. A., Labis J. P., ALOthman Z. A., Alhoshan M., Elzatahry A. A., et al. (2016). Design, synthesis and applications of core-shell, hollow core, and nanorattle multifunctional nanostructures. Nanoscale 8 (5), 2510–2531. 10.1039/c5nr07004j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrand J., Nilsson H., Strömberg C., Jonas E., Freedman J. (2018). Colorectal cancer liver metastases - a population-based study on incidence, management and survival. BMC Cancer 18 (1), 78. 10.1186/s12885-017-3925-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriquez-Navas P. M., Wojtkowiak J. W., Gatenby R. A. (2015). Application of evolutionary principles to cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 75 (22), 4675–4680. 10.1158/0008-5472.can-15-1337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan A., Wang B., Wang X., Nie Y., Fan D., Zhao X., et al. (2021). Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: Current achievements and future perspective. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 17 (14), 3837–3849. 10.7150/ijbs.64077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan D., Zhou W., Wei H., Wang T., Zheng K., Yang C., et al. (2022c). Ferritinophagy-Mediated ferroptosis and activation of keap1/nrf2/HO-1 pathway were conducive to EMT inhibition of gastric cancer cells in action of 2,2'-Di-pyridineketone hydrazone dithiocarbamate butyric acid ester. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 3920664. 10.1155/2022/3920664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan S., Liu X., Fu Y., Li C., Wang J., Mei Q., et al. (2022a). A biodegradable "Nano-donut" for magnetic resonance imaging and enhanced chemo/photothermal/chemodynamic therapy through responsive catalysis in tumor microenvironment. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 608 (1), 344–354. 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.09.186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan S., Liu X., Li C., Wang X., Cao D., Wang J., et al. (2022b). Intracellular mutual amplification of oxidative stress and inhibition multidrug resistance for enhanced sonodynamic/chemodynamic/chemo therapy. Small 18 (13), e2107160. 10.1002/smll.202107160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooftman A., O'Neill L. A. J. (2022). Nanoparticle asymmetry shapes an immune response. Nature 601 (7893), 323–325. 10.1038/d41586-021-03806-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G., Ma L., Shen L., Lei Y., Guo L., Deng Y., et al. (2022). MIF/SCL3A2 depletion inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of colorectal cancer cells via the AKT/GSK-3β pathway and cell iron death. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 26 (12), 3410–3422. 10.1111/jcmm.17352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X., Deng G., Han Y., Yang G., Zou R., Zhang Z., et al. (2019). Right Cu 2− x S@MnS core–shell nanoparticles as a photo/H 2 O 2 -responsive platform for effective cancer theranostics. Adv. Sci. (Weinh). 6 (20), 1901461. 10.1002/advs.201901461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W. G., Sanders A. J., Katoh M., Ungefroren H., Gieseler F., Prince M., et al. (2015). Tissue invasion and metastasis: Molecular, biological and clinical perspectives. Semin. Cancer Biol. 35, S244–S275. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2015.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Stockwell B. R., Conrad M. (2021). Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22 (4), 266–282. 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppe M. J., Bleichrodt R. P., Oyen W. J., Boerman O. C. (2005). Radioimmunotherapy and colorectal cancer. Br. J. Surg. 92 (3), 264–276. 10.1002/bjs.4936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Zandkarimi F., Zhang Y., Meena J. K., Kim J., Zhuang L., et al. (2020). Energy-stress-mediated AMPK activation inhibits ferroptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 22 (2), 225–234. 10.1038/s41556-020-0461-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D., Li Y. (2020). The interaction between ferroptosis and lipid metabolism in cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 5 (1), 108. 10.1038/s41392-020-00216-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X., Li W., Wang M., Liao Z. (2021). Magnetic nanoparticles for cancer theranostics: Advances and prospects. J. Control. Release 335, 437–448. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.05.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y., Mitriashkin A., Lim T. T., Goh J. C. (2021). Conductive polypyrrole-encapsulated silk fibroin fibers for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials 276, 121008. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Wang S., Sun Q., Yang Z., Liu M., Tang H. (2018). Retracted: DCLK1 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the PI3K/akt/NF-κB pathway in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 142 (10), 2068–2079. 10.1002/ijc.31232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L., Li X., Zhang J., Zhu C., Jiang M., Luo Z., et al. (2021). Enhanced immune memory through a constant photothermal-metabolism regulation for cancer prevention and treatment. Biomaterials 270, 120678. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.120678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma P., Xiao H., Yu C., Liu J., Cheng Z., Song H., et al. (2017). Enhanced cisplatin chemotherapy by iron oxide nanocarrier-mediated generation of highly toxic reactive oxygen species. Nano Lett. 17 (2), 928–937. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miar S., Ong J. L., Bizios R., Guda T. (2021). Electrically stimulated tunable drug delivery from polypyrrole-coated polyvinylidene fluoride. Front. Chem. 9, 599631. 10.3389/fchem.2021.599631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min C., Eddy S. F., Sherr D. H., Sonenshein G. E. (2008). NF-κB and epithelial to mesenchymal transition of cancer. J. Cell. Biochem. 104, 733–744. 10.1002/jcb.21695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modest D. P., Pant S., Sartore-Bianchi A. (2019). Treatment sequencing in metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 109, 70–83. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M. J., Liu Z. G. (2011). Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Res. 21 (1), 103–115. 10.1038/cr.2010.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan H., Brookes M. J., Iqbal T. (2015). Iron and colorectal cancer: Evidence from in vitro and animal studies. Nutr. Rev. 73 (5), 308–317. 10.1093/nutrit/nuu015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel M., Horgan P. G., McMillan D. C., Edwards J. (2018). NF-κB pathways in the development and progression of colorectal cancer. Transl. Res. 197, 43–56. 10.1016/j.trsl.2018.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps O., Brookes M. J., Al-Hassi H. O. (2021). Iron deficiency, immunology, and colorectal cancer. Nutr. Rev. 79 (1), 88–97. 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploug M., Kroijer R., Qvist N., Lindahl C. H., Knudsen T. (2021). Iron deficiency in colorectal cancer patients: A cohort study on prevalence and associations. Colorectal Dis. 23 (4), 853–859. 10.1111/codi.15467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebersek M. (2020). Consensus molecular subtypes (CMS) in metastatic colorectal cancer -personalized medicine decision. Radiol. Oncol. 54 (3), 272–277. 10.2478/raon-2020-0031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setyawati M. I., Leong D. T. (2017). Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as an antitumoral-angiogenesis strategy. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 9 (8), 6690–6703. 10.1021/acsami.6b12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D., Fuchs H. E., Jemal A. (2021). Cancer statistics, 2021. Ca. A Cancer J. Clin. 71 (1), 7–33. 10.3322/caac.21654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L. J., Zhang J. H., Gomez H., Murugan R., Hong X., Xu D., et al. (2019). Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 1–13. 10.1155/2019/5080843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun T., Zhang Y. S., Pang B., Hyun D. C., Yang M., Xia Y. (2014). Engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer therapy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53 (46), 12320–12364. 10.1002/anie.201403036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W., Ge K., Jin Y., Han Y., Zhang H., Zhou G., et al. (2019). Bone-targeted nanoplatform combining zoledronate and photothermal therapy to treat breast cancer bone metastasis. ACS Nano 13 (7), 7556–7567. 10.1021/acsnano.9b00097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Zhang Y., Li J., Park K. S., Han K., Zhou X., et al. (2021). Amplifying STING activation by cyclic dinucleotide-manganese particles for local and systemic cancer metalloimmunotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16 (11), 1260–1270. 10.1038/s41565-021-00962-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang D., Chen X., Kang R., Kroemer G. (2021). Ferroptosis: Molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 31 (2), 107–125. 10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Liu Y., He M., Bu W. (2019). Chemodynamic therapy: Tumour microenvironment-mediated Fenton and fenton-like reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (4), 946–956. 10.1002/anie.201805664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torti S. V., Manz D. H., Paul B. T., Blanchette-Farra N., Torti F. M. (2018). Iron and cancer. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 38, 97–125. 10.1146/annurev-nutr-082117-051732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torti S. V., Torti F. M. (2020). Iron and cancer: 2020 vision. Cancer Res. 80 (24), 5435–5448. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaiopoulos A. G., Athanasoula K. C., Papavassiliou A. G. (2013). NF-κB in colorectal cancer. J. Mol. Med. 91 (9), 1029–1037. 10.1007/s00109-013-1045-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson M. J., Harlaar J. J., Jeekel J., Schipperus M., Zwaginga J. J. (2018). Iron therapy as treatment of anemia: A potentially detrimental and hazardous strategy in colorectal cancer patients. Med. Hypotheses 110, 110–113. 10.1016/j.mehy.2017.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Diab I., Zhang X., Izmailova E. S., Zehner Z. E. (2004). Stat3 enhances vimentin gene expression by binding to the antisilencer element and interacting with the repressor protein, ZBP-89. Oncogene 23, 168–178. 10.1038/sj.onc.1207003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Fan J., Qin X., Cai J., Gu J., Wang S., et al. (2019). Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of colorectal liver metastases (version 2018). J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 145 (3), 725–736. 10.1007/s00432-018-2795-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu N., Qiu P., Ren Q., Wen M., Geng P., Macharia D. K., et al. (2021). Transforming a sword into a knife: Persistent phototoxicity inhibition and alternative therapeutical activation of highly-photosensitive phytochlorin. ACS Nano 15 (12), 19793–19805. 10.1021/acsnano.1c07241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Forgham H., Shen A., Qiao R., Guo B. (2022). Recent advances in single Fe-based nanoagents for photothermal-chemodynamic cancer therapy. Biosens. (Basel) 12 (2), 86. 10.3390/bios12020086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q., Lenardo M. J., Baltimore D. (2017). 30 Years of NF-κB: A blossoming of relevance to human pathobiology. Cell 168 (1-2), 37–57. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D. W., Lei Q., Zhu J. Y., Fan J. X., Li C. X., Li C., et al. (2017). Switching apoptosis to ferroptosis: Metal-organic network for high-efficiency anticancer therapy. Nano Lett. 17 (1), 284–291. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b04060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N., Wang Q., Li C., Wang X., Liu X., Wang X., et al. (2021). Responsive degradable theranostic agents enable controlled selenium delivery to enhance photothermal radiotherapy and reduce side effects. Adv. Healthc. Mat. 10 (10), e2002024. 10.1002/adhm.202002024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N. N., Kong W. Y., Huang Z., Liu X. J., Liang S. H., Deng G. Y., et al. (2022). Novel theranostic nanoagent based on CuMo2S3-PEG-Gd for MRI-guided photothermal/photodynamic/chemodynamic therapy. Rare Met. 41 (1), 45–55. 10.1007/s12598-021-01793-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Yang A., Huang Z., Yin G., Pu X., Jin J. (2017). Enhancement of neurite adhesion, alignment and elongation on conductive polypyrrole-poly (lactide acid) fibers with cell-derived extracellular matrix. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 149, 217–225. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Feng W., Chang J., Tan Y. W., Li J., Chen M., et al. (2016). Temperature-feedback upconversion nanocomposite for accurate photothermal therapy at facile temperature. Nat. Commun. 7, 10437. 10.1038/ncomms10437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.