This study aims to determine whether top surgery improves chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image in transgender and nonbinary adolescents and young adults designated female at birth.

Key Points

Question

Does gender-affirming top surgery improve chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image in transmasculine and nonbinary adolescents and young adults?

Findings

This nonrandomized, multicenter, prospective, control-matched study showed that top surgery was associated with statistically significant improvement in chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image at 3 months postsurgery. Surgical complications were minimal.

Meaning

This study suggests that gender-affirming top surgery is associated with improved chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image in this age group.

Abstract

Importance

Transgender and nonbinary (TGNB) adolescents and young adults (AYA) designated female at birth (DFAB) experience chest dysphoria, which is associated with depression and anxiety. Top surgery may be performed to treat chest dysphoria.

Objective

To determine whether top surgery improves chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image in TGNB DFAB AYA.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This is a nonrandomized prospective cohort study of patients who underwent top surgery between December 2019 and April 2021 and a matched control group who did not receive surgery. Patients completed outcomes measures preoperatively and 3 months postoperatively. This study took place across 3 institutions in a single, large metropolitan city. Patients aged 13 to 24 years who presented for gender-affirming top surgery were recruited into the treatment arm. Patients in the treatment arm were matched with individuals in the control arm based on age and duration of testosterone therapy.

Exposures

Patients in the surgical cohort underwent gender-affirming mastectomy; surgical technique was at the discretion of the surgeon.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Patient-reported outcomes were collected at enrollment and 3 months postoperatively or 3 months postbaseline for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the Chest Dysphoria Measure (CDM). Secondary outcomes included the Transgender Congruence Scale (TCS) and Body Image Scale (BIS). Baseline demographic and surgical variables were collected, and descriptive statistics were calculated. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to estimate the association of top surgery with outcomes. Probability of treatment was estimated using gradient-boosted machines with the following covariates: baseline outcome score, age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, insurance type, body mass index, testosterone use duration, chest binding, and parental support.

Results

Overall, 81 patients were enrolled (mean [SD] age, 18.6 [2.7] years); 11 were lost to follow-up. Thirty-six surgical patients and 34 matched control patients completed the outcomes measures. Weighted absolute standardized mean differences were acceptable between groups with respect to body mass index, but were not comparable with respect to the remaining demographic variables baseline outcome measures. Surgical complications were minimal. IPTW analyses suggest an association between surgery and substantial improvements in CDM (–25.58 points; 95% CI, –29.18 to –21.98), TCS (7.78 points; 95% CI, 6.06-9.50), and BIS (–7.20 points; 95% CI, –11.68 to –2.72) scores.

Conclusions and Relevance

Top surgery in TGNB DFAB AYA is associated with low complication rates. Top surgery is associated with improved chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image satisfaction in this age group.

Introduction

Recent studies estimate that up to 9% of adolescents and young adults (AYA) identify as transgender or nonbinary (TGNB).1 Many TGNB youth designated female at birth (DFAB) experience chest dysphoria, defined as distress related to the development of breasts.2 Chest dysphoria can lead to negative physical and emotional consequences, such as lack of participation in exercise and sports, chest-binding practices that can be physically harmful when not performed safely, psychosocial distress, functional limitations, and suicidal ideation.2,3,4 A retrospective review by our group of 156 TGNB DFAB AYA aged 12 to 18 years found that chest dysphoria was associated with greater anxiety and depression independent of gender dysphoria, degree of appearance congruence, and social transition status.5 TGNB youth may perform chest binding to relieve gender dysphoria, improve social acceptance, and reduce misgendering.3 However, chest binding may cause skin irritation, musculoskeletal pain, and shortness of breath.6 Prior research has shown that most TGNB youth who perform chest binding desire definitive top surgery.3

Top surgery (ie, mastectomy or reduction) is a common gender-affirming surgery sought by TGNB DFAB individuals and has been shown to improve chest dysphoria and quality of life in adults.7,8,9 Top surgery among TGNB DFAB patients increased 15% in 2020 compared with 2019.10 While outcomes of top surgery in adults are well reported, outcomes in youth are not well described.11,12,13 A qualitative study of 30 TGNB DFAB AYA reported that patients who underwent top surgery experienced near or total resolution of chest dysphoria, lack of surgical regret, and improved quality of life and functioning.4 The Chest Dysphoria Measure (CDM) was recently introduced to assess chest dysphoria in TGNB patients, and youth who had not received top surgery had CDM scores nearly 10 times higher than those who did receive top surgery.2 Despite these promising findings, these studies are limited by their retrospective design. There is a need for robust prospective studies in TGNB youth to guide evidence-based practices, especially with increasing proposed legislation to criminalize gender-affirming health care for minors.

The present study evaluates the association of top surgery with chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image in TGNB DFAB AYA. We hypothesize that top surgery will significantly improve chest dysphoria compared with patients who do not undergo top surgery. To our knowledge, this is the first and only prospective matched cohort study evaluating top surgery in youth to date.

Methods

Study Sample and Design

This is a multicenter, prospective, matched cohort study, in which TGNB DFAB AYA were recruited between December 2019 and April 2021 to 1 of 2 study arms: patients undergoing surgical mastectomy (treatment group) or patients not undergoing surgical mastectomy (control group). There was no attempt to randomize patients. Patients in the treatment group were recruited from Northwestern Memorial Hospital, The University of Illinois at Chicago, or Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago at their preoperative consults for top surgery. Inclusion criteria for treatment patients were 13 to 24 years of age at the time of surgery, transmasculine or nonbinary gender identity, DFAB, and English speaking. Gender-affirming hormone therapy was not a requirement in order to recruit patients who may not be interested in hormones but were interested in top surgery.14 Control patients were recruited from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago’s Gender and Sex Development Program. Inclusion criteria for control patients were 13 to 24 years of age, presenting for gender-affirming care, transmasculine or nonbinary gender identity, DFAB, and English speaking.

Multicenter institutional review board approval was obtained. Oral and written informed consent were obtained from patients older than 18 years, and from parents when patients were younger than 18 years. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guidelines were followed.

Intervention and Matching

All patients in the treatment arm were assessed for surgical readiness according to World Professional Association for Transgender Health guidelines Standards of Care version 7.15 Health care professionals tailored surgical techniques to each individual’s presentation and preferences. Preoperative and postoperative care protocols varied by institution, and no attempt to standardize surgical technique or protocol was made. Patients in the control group did not receive surgical intervention for chest dysphoria during the study period. Control patients who underwent top surgery during the study period were removed from the study. Two control patients were matched to each treatment patient; the 2:1 matching rate was chosen to account for expected control patient attrition, with a goal of a final 1:1 matching rate for analysis. Patients were matched by age (±1 year) and duration of testosterone therapy (±1 year) at the time of surgery.

Study Variables and Baseline Measures

Demographic variables, date of testosterone therapy initiation, and surgical details were collected via patient medical record review. Race and ethnicity information was obtained from the patient medical record; categories for these variables are provided by the electronic medical record. Age, gender identity, sex designated at birth, and chest binding practices at initial presentation were collected with a survey distributed through Research Electronic Data Capture hosted at Northwestern University.

Parental Support of Gender Variance—Child/Youth

The Parental Support of Gender Variance (PSGV-CY) is a 21-item questionnaire assessing the respondent’s perception of their relationship with their parents and perceived support for their gender identity.16 Items are scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater parental support. The PSGV-CY score was only measured at baseline assessment.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Patient-reported outcomes were obtained via Research Electronic Data Capture preoperatively as a baseline and 3 months postoperatively for surgery patients or postbaseline for control patients. The 3-month time frame was chosen as a period beyond immediate postsurgical pain and euphoria, while remaining in proximity to the study intervention.

Chest Dysphoria

The primary outcome measure of this study is the CDM. The CDM is a 17-item questionnaire that measures aspects of chest dysphoria.2 It is the only validated instrument published to date that measures chest dysphoria in TGNB AYA patients. Questions assess physical functioning, hygiene, exercise, intimate partnerships, and disruption of plans. Items are rated on a 4-point scale (0 = never, 3 = all the time) and summed, with higher scores indicating greater chest dysphoria (range, 0-51). This measure has high internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.79 for postsurgical patients, and α = 0.89 for nonsurgical patients).2

Gender Congruence

The Transgender Congruence Scale (TCS) is a 12-item questionnaire that evaluates congruence between gender identity and life experience. The TCS comprises 2 subscales, appearance congruence (TCS-AC) and gender identity acceptance (TCS-GIA). The 9-item TCS-AC measures the degree to which respondents feel their external appearance represents their gender identity. The 3-item TCS-GIA measures the degree to which patients accept their self-identified gender identity rather than the gender identity designated by society. Items are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) and summed, with higher scores representing favorable gender congruence. The TCS has strong internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.94 for TCS-AC, α = 0.77 for TCS-GIA, and α = 0.92 for TCS).17

Body Image

The Body Image Scale (BIS) is a 30-item questionnaire that assesses satisfaction with various body parts, rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very satisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied) and summed.18,19 The BIS includes primary sex characteristics, secondary sex characteristics, and neutral (nonsex-related) body parts.18,20 The BIS includes subscales based on 6 primary, 14 secondary, and 10 neutral characteristics. The BIS has moderate internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.65 for primary characteristics, α = 0.84 for secondary characteristics, and α = 0.81 for neutral characteristics).20

Data Collection and Analysis

Primary (CDM) and secondary (TCS, BIS) outcomes were analyzed with inverse probability treatment weighting (IPTW) propensity score analysis with linear regression adjustments. As robustness checks, we also estimated association of top surgery with outcomes via nearest-neighbor and poststratification matching, linear regression analysis with covariate adjustment, sensitivity analyses, and analysis of gain scores (secondary analyses).

The IPTW propensity score analysis was performed to improve balance of covariates between surgery groups and control groups on baseline measures.21 The propensity score analysis first involved estimating the probability of receiving surgery using a gradient boosted machine as a function of the following covariates: race, ethnicity, baseline outcome scores for outcomes of interest, age, insurance type, body mass index, testosterone use duration, chest binding, and parental support of gender variance score. Probability of treatment was computed based on propensity scores, and IPTW analyses used weights inversely proportional to the probability of treatment. Balance was checked among covariates with unweighted absolute standardized mean differences (SMDs) and weighted absolute SMDs after matching. To minimize the association of remaining imbalance between the surgery and control groups after weighting, our final IPTW analysis used (weighted) linear adjustments for covariates that did not exhibit satisfactory balance after weighting. Prior to IPTW analysis, we excluded control patients with low chest dysphoria (CDM score <19), high transgender congruence (TCS score >50), and low body image dissatisfaction (BIS score <50) to better ensure that the surgery and control groups were comparable. The final cohort for IPTW analysis included 25 control patients and 35 surgical patients. Methods describing the secondary analyses are available in the online supplement (eMethods in the Supplement).

Subgroup analysis was conducted for patients younger than 18 years. This was done because the age of 18 is often used as an arbitrary cutoff for insurance companies for reimbursing care. The same covariates were used in these models, except for age. IPTW propensity score analysis was recalculated for the subgroup and outliers were removed in a similar fashion. The final cohort for IPTW subgroup analysis included 9 control patients and 15 surgical patients. All analyses were performed using R (The R Project) version 4.0.1 and RStudio (The R Project) version 1.3.959.22

Results

Table 1 compares baseline characteristics between surgery and control groups (mean [SD] age, 18.6 [2.7] years), with unweighted absolute SMDs and weighted absolute SMDs after propensity score matching. There were 36 patients in the surgery group and 34 patients in the control group. The planned 2:1 matching rate resulted in the anticipated 1:1 final matched rate; recruitment of control patients was difficult given the limited number of available patients and lack of testosterone-matched and age-matched controls for some surgical patients. Eleven patients were lost to follow-up (6 surgical patients and 5 control patients). Drop-out patients had significantly greater median (IQR) baseline CDM (52.0 [46.0-53.0] vs 29.0 [23.0-35.8]) and BIS (103.0 [91.5-109] vs 87.0 [75.3-96.8]) compared with retained patients. Reasons for dropping out of the study are unknown. After propensity score matching, most absolute SMDs improved with weighting, but did not achieve desired balance of less than 0.1 for all covariates.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics.

| Variable | No. (%) | Absolute standardized mean difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 70) | Control (n = 34) | Surgical (n = 36) | |||

| Unweighteda | Weightedb | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 18.6 (2.7) | 18.3 (2.3) | 18.8 (3.1) | 0.092 | 0.232 |

| Gender identityc | |||||

| Transgender man | 59 (84) | 27 (79) | 32 (89) | 0.134 | 0.133 |

| Nonbinary/genderqueer | 9 (13) | 6 (18) | 3 (8) | 0.134 | 0.133 |

| Other | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | NA | NA |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.0 (6.7) | 26.8 (6.8) | 25.3 (6.7) | 0.307 | 0.089 |

| Raced | |||||

| African American | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | 0.343 | 0.423 |

| Asian | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | NA | NA |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | NA | NA |

| White | 62 (89) | 32 (94) | 30 (83) | 0.343 | 0.423 |

| Ethnicityd | |||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 13 (19) | 8 (24) | 5 (14) | 0.343 | 0.175 |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 56 (80) | 25 (74) | 31 (86) | 0.343 | 0.175 |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | ||

| Smoking statusc | |||||

| Current smoker | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0.269 | 0.278 |

| Former smoker | 7 (10) | 1 (3) | 6 (17) | NA | NA |

| Never smoker | 60 (86) | 31 (91) | 29 (81) | 0.269 | 0.278 |

| Unknown | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | NA | NA |

| Performs chest binding | 26 (37) | 9 (27) | 17 (47) | 0.278 | 0.227 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| ADHD | 10 (14) | 8 (24) | 2 (6) | 0.445 | 0.436 |

| Anxiety | 21 (30) | 10 (30) | 11 (31) | 0.165 | 0.166 |

| Asthma | 7 (10) | 2 (6) | 5 (14) | 0.114 | 0.116 |

| Depression | 27 (39) | 15 (44) | 12 (33) | 0.200 | 0.200 |

| Diabetes | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0.064 | 0.063 |

| Using testosteronec | 67 (96) | 32 (94) | 35 (97) | 0.236 | 0.228 |

| Testosterone use in months, mean (SD) | 20.1 (9.3) | 22.4 (7.7) | 18.1 (10.3) | 0.371 | 0.236 |

| PSGV total score, mean (SD) | 78.9 (17.0) | 76.3 (18.3) | 81.23 (17.1) | 0.405 | 0.251 |

| Insurance type | |||||

| Commercial/managed care | 51 (73) | 23 (68) | 28 (78) | 0.444 | 0.318 |

| Medicaid | 16 (23) | 11 (32) | 5 (14) | 0.444 | 0.318 |

| Self-pay | 3 (4) | 0 (0) | 3 (8) | ||

| Days between surveys, mean (SD)c | 94.7 (40.1) | 97.9 (45.8) | 91.7 (34.2) | 0.226 | 0.218 |

| Baseline, mean (SD) | |||||

| CDM | 28.8 (9.4) | 25.7 (10.6) | 31.8 (6.9) | 0.202 | 0.314 |

| TCS | 37.9 (8.8) | 40.7 (9.4) | 35.3 (7.5) | 0.284 | 0.257 |

| BIS | 87.2 (17.0) | 88.3 (19.4) | 86.2 (14.6) | 0.459 | 0.387 |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; BMI, body mass index; BIS, Body Image Scale; CDM, Chest Dysphoria Measure; NA, not applicable; PSGV, Parental Support of Gender Variance; TCS, Transgender Congruence Scale.

Unweighted standardized mean differences were calculated for the entire cohort.

Weighted standardized mean differences were calculated after excluding patients with CDM scores less than 19, TCS scores more than 50, and BIS scores less than 50.

Indicates covariate was not used in propensity score matching.

Race and ethnicity were self-identified.

Average age was comparable in the treatment and control groups. Most patients in both groups identified as transmasculine, were White, were not Hispanic/Latinx, and were never smokers (Table 1). Testosterone use in months was comparable in both groups; eFigure 1 in the Supplement illustrates testosterone use vs age for the surgical and control groups. Two patients in the control group and 1 patient in the surgical group were not taking testosterone. Seventeen surgical patients reported performing chest binding, while 9 control patients reported binding. Complete case analysis was performed comparing demographic variables between complete and incomplete patient medical records. There were no statistically significant findings between complete and incomplete cases.

The most common surgical technique was double incision mastectomy with nipple areolar complex grafting (n = 24 [67%]), followed by nipple-sparing mastectomy (n = 10 [28%]), and periareolar mastectomy (n = 2 [ 6%]). The resection weight was calculated as the average value of both breasts. Median (IQR) resection weight in grams was 329.5 (111.9-552.8). Seven patients (19%) received concomitant liposuction and 29 patients (81%) received drains. Median (IQR) drain duration was 8.3 (7.0-9.0) days. Complications were minimal, with 1 hematoma (3%), 2 seromas (6%), and 1 instance of nipple loss (3%). There were no incidences of infection or delayed wound healing.

Chest Dysphoria

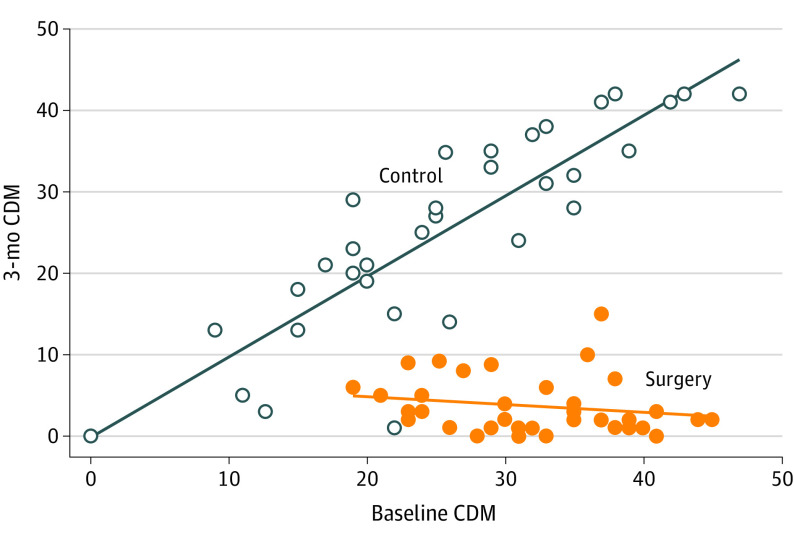

An exploratory data analysis was performed. Covariates including age, body mass index, and testosterone use in months appeared normally distributed. Table 2 outlines IPTW analysis results for the primary and secondary outcomes of interest. Summary statistics for 3-month outcomes scores in each group are also reported. eFigure 2 in the Supplement illustrates boxplot distribution of propensity scores for each group. eFigure 3 in the Supplement illustrates mean and standard deviation of propensity scores across quintiles for each group. The IPTW model estimated a 25.58 (95% CI, –29.18 to –21.98) point decrease in CDM for the surgery group relative to the control group. The Figure illustrates 3-month CDM as a function of baseline CDM. Three-month CDM scores for all surgery patients were low, regardless of baseline CDM score. The mean (SD) difference between baseline and 3-month scores in the treatment group was –28.12 (8.32). In contrast, among control patients, CDM scores did not appear to change significantly at 3 months. The mean (SD) difference between baseline and 3-month scores in the control group was –0.52 (6.29). Table 3 outlines subgroup analysis of outcomes among patients under 18 years. The IPTW model estimated a 25.48 (95% CI, –32.85 to –18.11) point decrease in CDM for the surgery group relative to the control group.

Table 2. Inverse Probability Treatment Weighting Propensity Score Model Results for Entire Cohorta.

| Outcome | Unweighted mean (SD) | Weighted PS model (surgery estimate [95% CI]) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 25) | Surgery (n = 35) | ||

| Primary outcome | |||

| 3-mo CDM score | 30.50 (8.37) | 3.80 (3.47) | – 25.58 (– 29.18 to – 21.98) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| 3 month | |||

| TCS | 36.90 (4.25) | 44.40 (3.59) | 7.78 (6.06-9.50) |

| TCS AC | 26.80 (4.64) | 33.50 (3.23) | 7.11 (5.44-8.79) |

| BIS | 91.90 (15.80) | 77.00 (13.00) | – 7.20 (– 11.68 to – 2.72) |

| BIS secondary | 38.50 (8.08) | 34.10 (7.37) | – 0.11 (– 2.27 to 2.05) |

Abbreviations: AC, appearance congruence; BIS, Body Image Scale; CDM, Chest Dysphoria Measure; PS, Propensity Score; TCS, Transgender Congruence Scale.

Summary statistics and models were calculated after excluding patients with CDM scores less than 19, TCS scores more than 50, and BIS scores less than 50.

Figure. Baseline vs 3-Month Chest Dysphoria Measure (CDM) Scores Among Surgery and Control Patients.

The x-axis represents the baseline or preoperative CDM score and the y-axis represents the 3-month CDM score. A higher CDM score indicates worsening chest dysphoria. Three-month CDM scores for all surgery patients were low, regardless of baseline CDM score. Surgery patients with high baseline CDM scores experienced greater decreases in CDM scores after top surgery, as indicated by the cluster of points at the bottom right of the graph. Among control patients, there appears to be a linear trend in baseline CDM scores vs 3-month CDM scores, indicating that CDM scores remained unchanged or increased at 3 months.

Table 3. Inverse Probability Treatment Weighting Propensity Score Model Results for the Younger Than 18 Years Cohort.

| Outcome | Mean (SD) | Weighted PS model (surgery estimate [95% CI]) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 9) | Surgery (n = 15) | ||

| Primary outcome | |||

| 3-mo CDM score | 32.80 (8.89) | 3.47 (3.14) | –25.48 (–32.85 to –18.11) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| 3 month | |||

| TCS | 38.10 (3.06) | 45.30 (3.92) | 5.36 (0.47-10.24) |

| TCS AC | 27.30 (2.4) | 34.40 (3.83) | 5.41 (0.83-10.00) |

| BIS | 97.30 (14.20) | 79.90 (12.40) | –7.83 (–13.98 to –1.67) |

| BIS secondary | 40.00 (7.30) | 35.20 (6.58) | 0.99 (–2.52 to 4.51) |

Abbreviations: AC, appearance congruence; BIS, Body Image Scale; CDM, Chest Dysphoria Measure; PS, propensity score; TCS, Transgender Congruence Scale.

Gender Congruence

The IPTW model estimated a 7.78 (95% CI, 6.06-9.50) point increase in TCS for the surgery group relative to the control group (Table 2). Results for the TCS-AC subscore were similar (Table 2).

Table 3 reports results for the cohort of individuals younger than 18 years. The IPTW model estimated a 5.36 (95% CI, 0.47- 10.24) point increase in TCS for the surgery group relative to the control group. Results for the TCS-AC subscore were similar (Table 3).

Body Image Dissatisfaction

The IPTW model estimated a 7.20 (95% CI, –11.68 to –2.72) point decrease in BIS for the surgery group relative to the control group (Table 2), indicating reduced body dissatisfaction. Results for the BIS secondary subscore did not demonstrate a significant association between surgery and score improvement (Table 2).

Table 3 reports results for the younger than 18 years cohort. The IPTW model estimated a 7.83 (95% CI, –13.98 to –1.67) point decrease in BIS for the surgery group relative to the control group. Results for the BIS secondary subscore did not demonstrate a significant association between surgery and score improvement (Table 3).

Secondary Analyses

Results for the secondary analyses are available in the eResults in the Supplement. eTables 1 through 3 in the Supplement present these results, which are similar to those of the IPTW analysis.

Discussion

To our knowledge, we present the first and largest prospective matched study evaluating quantitative outcomes of top surgery among TGNB DFAB AYA. We found that top surgery was associated with significant improvement in chest dysphoria (measured by the CDM) 3 months postoperatively; patients receiving surgery exhibited substantial decreases in CDM from presurgery to postsurgery and their reductions in CDM were significantly greater than those for patients who did not undergo top surgery. Top surgery also led to significant improvements in gender congruence (TCS) and body image satisfaction (BIS) at 3 months postoperatively. Surgical complications were minimal and comparable with those in adult patients.23,24,25,26,27,28

Chest dysphoria can be treated with top surgery, and patients with minimal or no chest dysphoria may not require or desire top surgery. We removed participants with baseline CDM scores of less than 19 from the control group prior to conducting our primary analysis; this was the lowest CDM score in the surgery group. We acknowledge that several control patients with low CDM scores have not sought top surgery because of minimal chest dysphoria. Surgeons should consider treating patients with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria and who experience the negative mental and physical health effects of chest dysphoria.

In our practice, there is no predetermined timeline for gender-affirming medical or surgical treatment; patients are assessed individually by a multidisciplinary team for readiness. There is no evidence to support delaying surgery for eligible patients based on age. With all other covariates remaining equal, patients’ baseline outcome score was significantly associated with improvement in the 3-month outcome score in the IPTW models. For all outcome measures, the effect size of improvement was less than 1 point, and the clinical significance of this finding is minimal. This does not support the notion that dysphoria will improve over time without intervention. Treatment patients demonstrated significant improvement and a greater effect size in all measures after surgery compared to control patients.

TGNB youth frequently encounter systemic barriers to care. Obtaining insurance coverage for top surgery is a common problem; while World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care version 7 do not recommend a specific age for top surgery, many insurance plans deny coverage for patients younger than 18 years.29 Medicolegal barriers exist as many states have ratified legislation prohibiting, and even criminalizing, medical and surgical therapy in TGNB minors.30,31 This can lead to delays in care and health care avoidance, which result in worsening mental health burden.32 The American Academy of Pediatrics and the Pediatric Endocrine Society have issued statements in support of providing gender-affirming medical and surgical care to TGNB minors, contending that it is effective, safe, the standard of care, and should be covered by insurers.33,34,35 In this study, patients younger than 18 years demonstrated parallel trends of improved CDM, TCS, and BIS compared with the entire cohort, demonstrating the robustness of our findings in this age subgroup. Findings from this study can help dispel misconceptions that gender-affirming treatment is experimental and support evidence-based practices of top surgery. Our retrospective review demonstrated associations between chest dysphoria and anxiety and depression; top surgery can improve chest dysphoria, thereby leading to improvements in quality of life.5 Our results also corroborate studies that gender-affirming therapy improves mental health and quality of life among TGNB youth.

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. Analyses omit 11 patients whose outcomes were not measured due to attrition. Furthermore, we acknowledge that patients in the treatment group who were able to access surgery may have greater socioeconomic status and parental support, possibly introducing sampling bias. Patients in the control group may have desired top surgery but were unable obtain it due to both medical and nonmedical barriers; this could not be controlled during analysis. We were unable to achieve a high degree of balance on baseline measures between surgery and control groups, even after propensity score adjustments. Weighted SMDs exceeded 0.1 for many covariates, rendering analyses susceptible to confounding. As a sensitivity analysis, we computed E-values in the Supplement to quantify the potential effect of confounding; reported E-values suggest an extremely high degree of confounding would need to be present to negate estimated treatment effects. We acknowledge that there may be differences between groups and intrinsic differences in the gender experience that are unmeasurable. In the future, control patients should be better matched to treatment patients, with matching using several demographic variables and baseline outcome measures. This will permit estimation of a causal effect on subsequent analyses. Some insurance plans require testosterone therapy for 1 year prior to surgery; this may negatively affect nonbinary patients who do not undergo testosterone therapy and may have limited inclusion of this patient population in our cohort.2 Nonbinary patients continue to be underrepresented in the literature; subgroup analysis of nonbinary patients was not possible due to small sample size and future studies should focus on this population. One-year follow up data are currently being collected to determine the long-term effect of top surgery on chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image satisfaction.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, we present the first prospective study evaluating the association of top surgery with chest dysphoria and gender congruence in TGNB DFAB AYA. Top surgery in this age group is associated with improved chest dysphoria, gender congruence, and body image satisfaction.

eMethods.

eResults.

eTable 1. Matching Propensity Score Model Results

eTable 2. Analysis of Covariance Model Results with Sensitivity Analysis

eTable 3. Analysis of Gains Model Results

eFigure 1. Testosterone Use in Months versus Patient Age in Years. The x-axis represents the testosterone use (in months) prior to surgery and the y-axis represents patient age (in years). The black and red lines indicate regression lines (black is the control group, red is the surgery group). Both the surgery group and the control group appear to be balanced in terms of testosterone use. Those who have testosterone use at zero reported not using testosterone.

eFigure 2. Boxplots of Estimated Propensity Scores per Group

eFigure 3. Mean Propensity Scores by Group Across Quintiles

References

- 1.Kidd KM, Sequeira GM, Douglas C, et al. Prevalence of gender-diverse youth in an urban school district. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020049823. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-049823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olson-Kennedy J, Warus J, Okonta V, Belzer M, Clark LF. Chest reconstruction and chest dysphoria in transmasculine minors and young adults: comparisons of nonsurgical and postsurgical cohorts. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(5):431-436. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.5440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Julian JM, Salvetti B, Held JI, Murray PM, Lara-Rojas L, Olson-Kennedy J. The impact of chest binding in transgender and gender diverse youth and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(6):1129-1134. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehringer JE, Harrison JB, Quain KM, Shea JA, Hawkins LA, Dowshen NL. Experience of chest dysphoria and masculinizing chest surgery in transmasculine youth. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020013300. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-013300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sood R, Chen D, Muldoon AL, et al. Association of chest dysphoria with anxiety and depression in transmasculine and nonbinary adolescents seeking gender-affirming care. J Adolesc Health. 2021;68(6):1135-1141. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peitzmeier SM, Silberholz J, Gardner IH, Weinand J, Acevedo K. Time to first onset of chest binding-related symptoms in transgender youth. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e20200728. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rachlin K, Green J, Lombardi E. Utilization of health care among female-to-male transgender individuals in the United States. J Homosex. 2008;54(3):243-258. doi: 10.1080/00918360801982124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Grift TC, Elaut E, Cerwenka SC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Kreukels BPC. Surgical satisfaction, quality of life, and their association after gender-affirming surgery: a follow-up study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2018;44(2):138-148. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2017.1326190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poudrier G, Nolan IT, Cook TE, et al. Assessing quality of life and patient-reported satisfaction with masculinizing top surgery: a mixed-methods descriptive survey study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(1):272-279. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000005113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Society of Plastic Surgeons . 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2020/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2020.pdf

- 11.Skordis N, Butler G, de Vries MC, Main K, Hannema SE. ESPE and PES international survey of centers and clinicians delivering specialist care for children and adolescents with gender dysphoria. Horm Res Paediatr. 2018;90(5):326-331. doi: 10.1159/000496115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez CM, Solomon D, Boulware SD, Christison-Lagay ER. Trends in the use of puberty blockers among transgender children in the United States. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2018;31(6):665-670. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2018-0048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delahunt JW, Denison HJ, Sim DA, Bullock JJ, Krebs JD. Increasing rates of people identifying as transgender presenting to Endocrine Services in the Wellington region. N Z Med J. 2018;131(1468):33-42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal Treatment Strategies Tailored to Non-Binary Transgender Individuals. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):E1609. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. Int J Transgenderism. 2012;13(4):165-232. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forbes C, Banisaba B. Trans Youth Parental Support Measure. [Unpublished]. Published online 2010.

- 17.Kozee HB, Tylka TL, Bauerband LA. Measuring transgender individuals’ comfort with gender identity and appearance: development and validation of the transgender congruence scale. Psychol Women Q. 2012;36(2):179-196. doi: 10.1177/0361684312442161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindgren TW, Pauly IB. A body image scale for evaluating transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav. 1975;4(6):639-656. doi: 10.1007/BF01544272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuper LE, Stewart S, Preston S, Lau M, Lopez X. Body dissatisfaction and mental health outcomes of youth on gender-affirming hormone therapy. Pediatrics. 2020;145(4):e20193006. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van de Grift TC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Steensma TD, et al. Body satisfaction and physical appearance in gender dysphoria. Arch Sex Behav. 2016;45(3):575-585. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0614-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Austin PC, Stuart EA. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34(28):3661-3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Core Team . A language and environment for statistical computing. Accessed August 24, 2022. http://www.R-project.org/

- 23.McEvenue G, Xu FZ, Cai R, McLean H. Female-to-male gender affirming top surgery: a single surgeon’s 15-year retrospective review and treatment algorithm. Aesthet Surg J. 2017;38(1):49-57. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjx116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cuccolo NG, Kang CO, Boskey ER, et al. Masculinizing chest reconstruction in transgender and nonbinary individuals: an analysis of epidemiology, surgical technique, and postoperative outcomes. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019;43(6):1575-1585. doi: 10.1007/s00266-019-01479-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agarwal CA, Scheefer MF, Wright LN, Walzer NK, Rivera A. Quality of life improvement after chest wall masculinization in female-to-male transgender patients: a prospective study using the BREAST-Q and Body Uneasiness Test. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71(5):651-657. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2018.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van de Grift TC, Elfering L, Bouman M-B, Buncamper ME, Mullender MG. Surgical indications and outcomes of mastectomy in transmen: a prospective study of technical and self-reported measures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(3):415e-424e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van de Grift TC, Kreukels BPC, Elfering L, et al. Body image in transmen: multidimensional measurement and the effects of mastectomy. J Sex Med. 2016;13(11):1778-1786. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson SC, Morrison SD, Anzai L, et al. Masculinizing top surgery: a systematic review of techniques and outcomes. Ann Plast Surg. 2018;80(6):679-683. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuper LE, Rider GN, St Amand CM. Recognizing the importance of chest surgery for transmasculine youth. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029710. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyman B; Montgomery Advertiser . Alabama Senate approves bill banning transgender youth treatments amid protests at state Capitol. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://www.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/2021/03/02/alabama-senate-approves-bill-banning-transgender-youth-treatments/6867380002/

- 31.Freedom for All Americans . Legislative tracker: anti-transgender Medical Care bans. Accessed August 24, 2022. https://freedomforallamericans.org/legislative-tracker/medical-care-bans/

- 32.Park BC, Das RK, Drolet BC. Increasing criminalization of gender-affirming care for transgender youths—a politically motivated crisis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(12):1205-1206. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walch A, Davidge-Pitts C, Safer JD, Lopez X, Tangpricha V, Iwamoto SJ. Proper care of transgender and gender diverse persons in the setting of proposed discrimination: A policy perspective. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(2):305-308. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rafferty J; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child And Family Health; Committee on Adolescence; Section on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health and Wellness . Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(4):e20182162. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turban JL, Kraschel KL, Cohen IG. Legislation to criminalize gender-affirming medical care for transgender youth. JAMA. 2021;325(22):2251-2252. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.

eResults.

eTable 1. Matching Propensity Score Model Results

eTable 2. Analysis of Covariance Model Results with Sensitivity Analysis

eTable 3. Analysis of Gains Model Results

eFigure 1. Testosterone Use in Months versus Patient Age in Years. The x-axis represents the testosterone use (in months) prior to surgery and the y-axis represents patient age (in years). The black and red lines indicate regression lines (black is the control group, red is the surgery group). Both the surgery group and the control group appear to be balanced in terms of testosterone use. Those who have testosterone use at zero reported not using testosterone.

eFigure 2. Boxplots of Estimated Propensity Scores per Group

eFigure 3. Mean Propensity Scores by Group Across Quintiles