Key Points

Question

What is the incidence of severe COVID-19 illness following vaccination and booster with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines?

Findings

This retrospective cohort study included 1 610 719 participants receiving care at Veterans Health Administration facilities, followed up for 24 weeks (July 1, 2021, to May 30, 2022) after completing a COVID-19 vaccination series and booster. Overall, the incidence of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death was 8.9 per 10 000 persons.

Meaning

In a US cohort, there was a low incidence of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death following vaccination and booster during a period of Delta and Omicron variant predominance.

Abstract

Importance

Evidence describing the incidence of severe COVID-19 illness following vaccination and booster with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines is needed, particularly for high-risk populations.

Objective

To describe the incidence of severe COVID-19 illness among a cohort that received vaccination plus a booster vaccine dose.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of adults receiving care at Veterans Health Administration facilities across the US who received a vaccination series plus 1 booster against SARS-CoV-2, conducted from July 1, 2021, to May 30, 2022. Patients were eligible if they had received a primary care visit in the prior 2 years and had documented receipt of all US Food and Drug Administration–authorized doses of the initial mRNA vaccine or viral vector vaccination series after December 11, 2020, and a subsequent documented booster dose between July 1, 2021, and April 29, 2022. The analytic cohort consisted of 1 610 719 participants.

Exposures

Receipt of any combination of mRNA-1273 (Moderna), BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), and Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson) primary vaccination series and a booster dose.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes were breakthrough COVID-19 (symptomatic infection), hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia and/or death, and hospitalization with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and/or death. A subgroup analysis of nonoverlapping populations included those aged 65 years or older, those with high-risk comorbid conditions, and those with immunocompromising conditions.

Results

Of 1 610 719 participants, 1 100 280 (68.4%) were aged 65 years or older and 132 243 (8.2%) were female; 1 133 785 (70.4%) had high-risk comorbid conditions, 155 995 (9.6%) had immunocompromising conditions, and 1 467 879 (91.1%) received the same type of mRNA vaccine (initial series and booster). Over 24 weeks, 125.0 (95% CI, 123.3-126.8) per 10 000 persons had breakthrough COVID-19, 8.9 (95% CI, 8.5-9.4) per 10 000 persons were hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia or died, and 3.4 (95% CI, 3.1-3.7) per 10 000 persons were hospitalized with severe pneumonia or died. For high-risk populations, incidence of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death was as follows: aged 65 years or older, 1.9 (95% CI, 1.4-2.6) per 10 000 persons; high-risk comorbid conditions, 6.7 (95% CI, 6.2-7.2) per 10 000 persons; and immunocompromising conditions, 39.6 (95% CI, 36.6-42.9) per 10 000 persons. Subgroup analyses of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia or death by time after booster demonstrated similar incidence estimates among those aged 65 years or older and with high-risk comorbid conditions but not among those with immunocompromising conditions.

Conclusions and Relevance

In a US cohort of patients receiving care at Veterans Health Administration facilities during a period of Delta and Omicron variant predominance, there was a low incidence of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death following vaccination and booster with any of BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or Ad26.COV2.S vaccines.

This retrospective cohort study assesses incidence of breakthrough COVID-19 and hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death among adults who received a vaccination series plus 1 booster against SARS-CoV-2.

Introduction

Vaccination against COVID-19 is highly effective at reducing hospitalization and death.1 Prior studies have also demonstrated that boosted populations are less likely to experience breakthrough infections.2 However, surveillance studies of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness have demonstrated that waning immunity and variants of SARS-CoV-2 are associated with reduced effectiveness of messenger RNA (mRNA)–based and viral vector–based vaccines over time.3,4,5,6,7 Until the recent availability of newer bivalent mRNA vaccines, booster doses had been recommended beginning 5 months after completion of the initial series following evidence of effectiveness against infection, hospitalization, and death compared with unboosted populations.8 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other agencies had recommended a shorter interval of at least 3 months between the initial series and booster for individuals who are immunocompromised.9 Although there is broad consensus that boosters protect against severe clinical outcomes, the incidence of severe COVID-19 illness following vaccination and booster with BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech), mRNA-1273 (Moderna), and Ad26.COV2.S (Janssen/Johnson & Johnson) vaccines is unknown, particularly as it pertains to high-risk and immunocompromised populations.

The US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) allows for creation of a national cohort of fully vaccinated, boosted participants. This study was conducted to estimate the incidence of infection (breakthrough COVID-19) and severe illness (hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death) following vaccination and booster with BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines among a large national cohort.

Methods

The institutional review board of the University of California, San Francisco, approved this study and waived requirement for patient consent as it involved no more than minimal risk to participants.

Study Design, Setting, and Data Sources

This was a retrospective cohort study of adults receiving care at VHA facilities who were fully vaccinated and boosted against SARS-CoV-2. The cohort was constructed using the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse10 and COVID-19 Shared Data Resource.11 The VHA operates a national health system with co-localized services, including COVID-19 vaccination, laboratory testing, outpatient and inpatient services, and reporting that tabulates veteran data from other health systems. The VHA began administering the initial series of COVID-19 vaccinations to participants after December 11, 2020. The health system distributed to facilities the initial series of either mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2 vaccines based on local access to cold chain capacity and geography. All facilities received viral vector Ad26.COV2.S vaccines. Booster doses became available on July 1, 2021, and at the time, higher-risk groups, particularly immunocompromised individuals, were among the first to receive a third dose.

Participants

Adults receiving care at VHA facilities were eligible for inclusion if they had documented receipt of all US Food and Drug Administration–authorized doses of the initial vaccination series of an mRNA vaccine or viral vector vaccine and subsequently had documented receipt of a booster dose between July 1, 2021, and April 29, 2022. The cohort was restricted to participants who had a primary care visit during the prior 2 years to ensure adequate baseline data on health status. Participants who did not have a record of vaccination, did not receive the second mRNA dose within 6 weeks of the first dose, had no record of a booster dose or type, received their last mRNA vaccine dose within 5 months or last Ad26.COV2.S vaccine dose within 2 months of a prior dose,9 received hospice care within 2 years, resided in a nursing home or domiciliary within 2 years, or had a history of COVID-19 from 90 days before until 13 days after the booster were excluded (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Participants who had received a booster vaccination dose were followed up until May 30, 2022, the date of final follow-up. The observation period included predominance by both Delta and Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants.12

Measurements

Exposure was receipt of any combination of initial vaccination series followed by a booster dose. Vaccine-specific data included timing, type, and manufacturer. Vaccination data were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse.

The 3 primary outcomes were (1) breakthrough COVID-19 (symptomatic infection); (2) hospitalization with any diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia and/or all-cause death within 30 days after breakthrough infection; and (3) hospitalization with severe COVID-19 pneumonia and/or all-cause death within 30 days after breakthrough infection. Breakthrough COVID-19 was defined as a postbooster, laboratory-confirmed, symptomatic COVID-19 diagnosis. Documented infections were ascertained using the VA’s COVID-19 National Surveillance Tool, which identified infections outside of the VA health care system.13,14 Symptom status was ascertained using the VA’s COVID-19 Shared Data Resource.15

COVID-19–related hospitalization as a potential outcome was evaluated by drawing a random sample of 50 hospitalized participants within 30 days of postbreakthrough infection who did not have COVID-19 pneumonia. The outcome of hospitalization for COVID-19 pneumonia was chosen because many hospitalizations after a confirmed SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection are not primarily related to COVID-19 infection. Participants are tested for SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection as part of the admission process; thus, infection may be incidental to the cause of hospitalization. COVID-19 pneumonia was a clearly definable outcome related to SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 infection.

The outcome of COVID-19 pneumonia was verified through a combination of text processing–assisted chart review and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). Hospitalizations that were flagged by the chart review team as having an unclear diagnosis (eg, admission note mentioned pneumonia as a possible diagnosis, but pneumonia was never referred to again during hospitalization) were reviewed by 2 clinicians (J.D.K. and S.K.) and consensus was reached via discussion. Among the cases that were not flagged as having an unclear diagnosis, 10% were reviewed in duplicate by study staff. Agreement between the 2 reviewers was 95%. Hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia was defined as a diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia using ICD-10 code J12.84 in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse16 or documented by the clinical care team during hospitalization in the chart. Severe COVID-19 pneumonia was defined as hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia and receipt of mechanical ventilation.

Covariates were age, sex, race and ethnicity, marital status, urban or rural residence, geographic region (eFigure 2 in the Supplement), body mass index, comorbid conditions, history of SARS-CoV-2 infection, receipt of home-based primary care, and calendar time for vaccine series. Individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups and individuals from marginalized racial and ethnic populations have experienced more adverse COVID-19 outcomes than other populations17,18; acquisition of race and ethnicity data in the VHA occurred from patient or proxy self-report based on prespecified categories defined in VHA Handbook 1601A.01.19,20

Comorbid conditions associated with poor COVID-19 clinical outcomes in the literature (hospitalization and mortality) included hypertension, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, diabetes, stroke or transient ischemic attack, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or bronchiectasis, cirrhosis, dementia, spinal cord injury, immunocompromised status in the past year, chronic kidney disease, severe chronic kidney disease, dialysis, and cancer (solid organ, hematologic malignancies [lymphoma/leukemia], or other). Behavioral risk factors were current smoking, alcohol use disorder, and any non–alcohol-related or non–smoking-related substance use disorder. Social risk factors were housing problems (use of housing services in past year) and veteran priority score (a surrogate for income status). Reinfection was defined as 2 SARS-CoV-2 positive test results and/or COVID-19 diagnoses greater than 90 days apart. (See eAppendix 2 in the Supplement for full definitions.)

Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of the boosted cohort are described, stratified into 5 categories of vaccine booster type: 3 doses of mRNA-1273, 3 doses of BNT162b2, 2 doses of Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, same combinations of mRNA vaccines (3 doses), and different combinations of mRNA and Ad26.COV2.S vaccines.

Breakthrough COVID-19 and hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death or severe pneumonia or death were daily outcome events. The Kaplan-Meier estimator21 was used to calculate cumulative incidence as the probability (risk) of the outcome from the day of booster dose until end of follow-up and to generate cumulative incidence curves. For each person, follow-up started on the day of booster dose and ended on the day of outcome of interest, at death, 168 days (24 weeks) after baseline, or at the end of the study period (May 30, 2022), whichever happened first. Participants who died prior to developing breakthrough COVID-19 were censored on the date of death.

Within categories of vaccine booster type, a subgroup analysis was conducted for high-risk populations (age ≥65 years, high-risk comorbid conditions, immunocompromising conditions) against average-risk populations, then further subdivided into 3 nonoverlapping subgroups: (1) age 65 years or older without any high-risk conditions, (2) high-risk comorbid conditions (nonimmunocompromising and not cancer), and (3) immunocompromising conditions (including cancer). These subgroups were compared with adjusted Cox proportional hazards models. The proportionality assumption was tested with a log-log plot and was met (see Measurements section for confounders listed as covariates). The Cox models estimated cumulative incidence ratios. Findings were considered statistically significant if the confidence interval did not cross the null value or if the 2-sided P value was P < .05.

Although the general population (those who were not immunocompromised) was not eligible to receive the fourth vaccine dose until April 4, 2022, a small proportion (7.1%) of the overall cohort received a fourth dose before the end of follow-up (May 30, 2021). Given that some individuals received a fourth dose, a sensitivity analysis that censored follow-up time on the date of the fourth dose was conducted. Regardless of whether follow-up was censored based on the fourth dose, similar results were obtained among the overall cohort with and without censoring follow-up time on the date of fourth dose (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

Using an interaction P value cutoff of P = .20, interactions were evaluated by Delta variant and Omicron variant eras and by time after booster dose (1-50 days, 51-100 days, and 101-150 days). Missing data were handled as a “missing” category for the variable and not imputed in analyses. All analyses were conducted in R version 1.2.5019 (R Foundation), including the coxph package.

Results

From an initial group of 6 029 864 participants, the analytic cohort consisted of 1 610 719 participants who received an initial COVID-19 vaccination series, followed by a booster dose (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Among these participants, 1 100 280 (68.4%) were aged 65 years or older and 132 243 (8.2%) were female; 1 133 785 (70.4%) had high-risk comorbid conditions and 158 684 (9.9%) had immunocompromising conditions (Table 1; eTable 2 in the Supplement). The largest amount of missingness (8%) occurred with the body mass index variable.

Table 1. Characteristics of the Boosted Cohort by Combination of Vaccination Seriesa.

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 1 610 719) | Vaccine | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 (n = 793 712) | 3 Doses of BNT162b2 (n = 674 167) | 2 Doses of Ad26.COV2.S (n = 26 358) | Combinations | |||

| mRNA (n = 68 025)b | Ad26.COV2.S and mRNA (n = 48 457)c | |||||

| Sex, No. (%) | ||||||

| Female | 132 243 (8.2) | 57 854 (7.3) | 59 450 (8.8) | 2707 (10.3) | 7012 (10.3) | 5220 (10.8) |

| Male | 1 478 476 (91.8) | 735 858 (92.7) | 614 717 (91.2) | 23 651 (89.7) | 61 013 (89.7) | 43 237 (89.2) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 71 (61-76) | 72 (63-77) | 71 (61-75) | 65 (56-73) | 67 (56-74) | 62 (53-71) |

| No. (%) | ||||||

| 18-64 | 510 439 (31.7) | 218 183 (27.5) | 221 793 (32.9) | 13 037 (49.5) | 29 603 (43.5) | 27 823 (57.4) |

| 65-74 | 598 729 (37.2) | 300 167 (37.8) | 253 742 (37.6) | 9054 (34.4) | 21 646 (31.8) | 14 120 (29.1) |

| 75-84 | 379 402 (23.6) | 205 736 (25.9) | 152 523 (22.6) | 3428 (13.0) | 12 470 (18.3) | 5245 (10.8) |

| ≥85 | 122 149 (7.6) | 69 626 (8.8) | 46 109 (6.8) | 839 (3.2) | 4306 (6.3) | 1269 (2.6) |

| Race, No. (%)d | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 10 656 (0.7) | 5082 (0.6) | 4364 (0.6) | 226 (0.9) | 392 (0.8) | 592 (0.9) |

| Asian | 23 253 (1.4) | 10 051 (1.3) | 10 555 (1.6) | 304 (1.2) | 1148 (2.4) | 1195 (1.8) |

| Black or African American | 323 215 (20.1) | 133 845 (16.9) | 161 568 (24.0) | 5408 (20.5) | 12 698 (18.7) | 9696 (20.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 14 622 (0.9) | 6908 (0.9) | 6198 (0.9) | 253 (1.0) | 537 (1.1) | 726 (1.1) |

| White | 1 130 160 (70.2) | 586 123 (73.8) | 444 463 (65.9) | 18 308 (69.5) | 48 011 (70.6) | 33 255 (68.6) |

| ≥1 Race | 13 084 (0.8) | 6160 (0.8) | 5551 (0.8) | 267 (1.0) | 463 (1.0) | 643 (0.9) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnicity (regardless of race), No. (%)d | 116 271 (7.2) | 59 514 (7.5) | 46 458 (6.9) | 1701 (6.5) | 5040 (7.4) | 3558 (7.3) |

| Currently married, No. (%) | 939 120 (58.3) | 478 001 (60.2) | 386 535 (57.3) | 13 750 (52.2) | 37 729 (55.5) | 23 105 (47.7) |

| Urban residence, No. (%)e | 1 113 757 (69.1) | 502 105 (63.5) | 519 241 (77.3) | 15 375 (58.6) | 47 209 (69.8) | 29 827 (62.1) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 29 (26.01-33.34) | 29 (26.01-33.34) | 29 (26.06-33.39) | 29.8 (26.25-34.06) | 29.7 (26.15-34.01) | 29.5 (26.12-33.60) |

| No. (%) | ||||||

| <18.5 | 10 681 (0.7) | 5151 (0.7) | 4450 (0.7) | 237 (1) | 462 (0.8) | 381 (0.9) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 244 136 (15.2) | 120 198 (17.5) | 102 562 (17.3) | 3840 (16.6) | 10 230 (17.1) | 7306 (17.1) |

| 25-29.9 | 511 067 (31.7) | 251 340 (36.6) | 216 216 (36.4) | 7773 (33.5) | 21 272 (35.5) | 14 466 (33.9) |

| ≥30 | 641 482 (39.8) | 310 919 (45.2) | 270 762 (45.6) | 11 325 (48.9) | 27 956 (46.7) | 20 520 (48.1) |

| Comorbidities associated with severe COVID-19 illness, No. (%) | ||||||

| Hypertension | 990 693 (61.5) | 504 921 (63.6) | 407 188 (60.4) | 15 086 (57.2) | 37 795 (55.6) | 25 703 (53.0) |

| Diabetes | 530 433 (32.9) | 271 408 (34.2) | 217 655 (32.3) | 8116 (30.8) | 20 036 (29.5) | 13 218 (27.3) |

| Chronic kidney diseasef | 357 989 (22.2) | 188 127 (23.7) | 143 583 (21.3) | 4959 (18.8) | 13 534 (19.9) | 7786 (16.1) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 273 273 (17) | 144 279 (18.2) | 109 860 (16.3) | 3626 (13.8) | 9776 (14.4) | 5732 (11.8) |

| COPD bronchiectasis | 187 954 (11.7) | 100 751 (12.7) | 72 260 (10.7) | 2969 (11.3) | 6895 (10.1) | 5079 (10.5) |

| Heart failure | 93 014 (5.8) | 47 612 (6.0) | 38 216 (5.7) | 1285 (4.9) | 3633 (5.3) | 2268 (4.7) |

| Immunocompromisedg | 91 965 (5.7) | 46 058 (5.8) | 38 932 (5.8) | 1291 (4.9) | 3208 (4.7) | 2476 (5.1) |

| Cancer, solid organh | 56 464 (3.5) | 27 772 (3.5) | 24 815 (3.7) | 699 (2.7) | 1928 (2.8) | 1250 (2.6) |

| Severe chronic kidney diseasei | 47 438 (2.9) | 25 912 (3.3) | 17 646 (2.6) | 678 (2.6) | 1861 (2.7) | 1341 (2.8) |

| Stroke or TIA | 43 817 (2.7) | 21 510 (2.7) | 18 755 (2.8) | 627 (2.4) | 1766 (2.6) | 1159 (2.4) |

| Dementia | 30 318 (1.9) | 15 642 (2.0) | 12 173 (1.8) | 339 (1.3) | 1493 (2.2) | 671 (1.4) |

| Cirrhosis | 25 706 (1.6) | 11 559 (1.5) | 11 901 (1.8) | 411 (1.6) | 1044 (1.5) | 791 (1.6) |

| Cancer, lymphoma/leukemiah | 19 109 (1.2) | 10 070 (1.3) | 8022 (1.2) | 184 (0.7) | 533 (0.8) | 300 (0.6) |

| Dialysis | 10 009 (0.6) | 4787 (0.6) | 4438 (0.7) | 75 (0.3) | 512 (0.8) | 197 (0.4) |

| Cancer, otherh | 9993 (0.6) | 4639 (0.6) | 4738 (0.7) | 122 (0.5) | 283 (0.4) | 211 (0.4) |

| Date of first dose of vaccination series, by 3-mo period, No. (%) | ||||||

| December 2020 to February 2021 | 996 958 (61.9) | 535 848 (67.5) | 422 641 (62.7) | 2 (<0.1) | 37 580 (55.2) | 887 (1.8) |

| March 2021 to May 2021 | 578 447 (35.9) | 249 380 (31.4) | 240 788 (35.7) | 21 484 (81.5) | 28 946 (42.6) | 37 849 (78.1) |

| June 2021 to August 2021 | 31 821 (2) | 7807 (1.0) | 9729 (1.4) | 4202 (15.9) | 1371 (2.0) | 8712 (18.0) |

| September 2021 to November 2021 | 3274 (0.2) | 677 (0.1) | 1009 (0.1) | 588 (2.2) | 128 (0.2) | 872 (1.8) |

| December 2021 to February 2022 | 219 (<0.1) | 0 | 0 | 82 (0.3) | 0 | 137 (0.3) |

| Current smoker, No. (%) | 333 972 (20.7) | 160 482 (20.2) | 135 378 (20.1) | 7851 (29.8) | 15 446 (22.7) | 14 815 (30.6) |

| Alcohol use disorder, No. (%)j | 115 625 (7.2) | 52 909 (6.7) | 49 103 (7.3) | 2464 (9.3) | 5813 (8.5) | 5336 (11.0) |

| Substance use disorder, No. (%)k | 72 189 (4.5) | 31 986 (4.0) | 31 258 (4.6) | 1622 (6.2) | 3587 (5.3) | 3736 (7.7) |

| Housing problems, No. (%)l | 70 394 (4.4) | 30 777 (3.9) | 30 234 (4.5) | 1748 (6.6) | 3724 (5.5) | 3911 (8.1) |

| Follow-up time, median (IQR), d | 168 (166.0-168.0) | 168 (166.0-168.0) | 168 (168.0-168.0) | 168 (158.0-168.0) | 168 (146.0-168.0) | 161 (130.0-168.0) |

| Time elapsed between initial dose and booster, median (IQR), d | 270 (245.0-295.0) | 280 (258.0-302.0) | 258 (237.0-282.0) | 238 (205.0-262.0) | 284 (258.0-312.0) | 250 (218.0-283.0) |

| High-risk populations, No. (%) | 1 489 300 (92.5) | 744 518 (93.8) | 619 359 (91.9) | 23 611 (89.6) | 59 883 (88.0) | 41 929 (86.5) |

| Aged >65 y and no high-risk comorbid conditions, No. (%) | 196 831 (12.2) | 100 751 (12.7) | 83 998 (12.5) | 2141 (8.1) | 6654 (9.8) | 3287 (6.8) |

| High-risk comorbid conditions (nonimmunocompromising), No. (%)m | 1 133 785 (70.4) | 564 250 (71.1) | 467 581 (69.4) | 19 387 (73.6) | 47 795 (70.3) | 34 772 (71.8) |

| Immunocompromising conditions, No. (%) | 158 684 (9.9) | 79 517 (10.0) | 67 780 (10.1) | 2083 (7.9) | 5434 (8.0) | 3870 (8.0) |

| Aged <65 y and no comorbid conditions, No. (%) | 61 067 (3.8) | 23 876 (3.0) | 28 063 (4.2) | 1321 (5.0) | 4430 (6.5) | 3377 (7.0) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Full version of this table is available as eTable 2 in the Supplement.

Combination mRNA included all possible combinations in which mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 were received.

This combination group received Ad26.COV2.S first then either mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2, or vice versa.

Race and ethnicity were assessed using self-identified data found in Veterans Health Administration records.

Urban or rural residence was defined based on the Rural-Urban Commuting Area categories developed by the Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services Health Resource and Services Administration.

Chronic kidney disease was defined as having a glomerular filtration rate between 30 and 60 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Immunocompromised was defined based on medications and history of cancer (see eAppendix 3 of the Supplement for list of medications).

Cancer was defined based on diagnosis codes (2 outpatient diagnosis codes or 1 inpatient diagnosis code in the Veterans Health Administration) (eAppendix 3 of the Supplement).

Severe chronic kidney disease was defined as having a glomerular filtration rate less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

Alcohol use disorder was defined as 1 outpatient or 1 inpatient diagnosis code within 2 years of index.

Including cannabis, opioids, and inhalants.

Housing problems were defined as homelessness, inadequate housing, and other problems related to housing and economic circumstances.

As defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, older adults, people with medical conditions who are immunocompromised, and pregnant and recently pregnant people.

Of 1 610 719 participants, 95.9% received their initial vaccination series between December 2020 and April 2021. Between July 1 and November 30, 2021 (Delta variant period), 61.8% received boosters, and the remaining 614 465 participants (38.2%) received boosters after December 1, 2021 (Omicron variant period). Most (1 467 879[ 91.1%]) received the same type of mRNA vaccines (initial and booster). Among high-risk populations, 12.4% were aged 65 years or older, 70.4% had high-risk comorbid conditions, and 9.9% had immunocompromising conditions.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Over a 24-week follow-up period, 20 138 of 1 610 719 individuals had breakthrough COVID-19 (125.0 events [95% CI, 123.3-126.8] per 10 000 persons), 1435 were hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia or died (8.9 events [95% CI, 8.5-9.4] per 10 000 persons), and 541 were hospitalized with severe pneumonia or died (3.4 events [95% CI, 3.1-3.7] per 10 000 persons) (Table 2; eTable 3 in the Supplement). These cumulative incidence estimates were similar regardless of vaccination and booster combination.

Table 2. Incidence of Breakthrough COVID-19, Hospitalization With COVID-19 Pneumonia, Hospitalization With Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia, and Death Following Vaccination and Booster.

| COVID-19 outcomes by vaccination and booster | High-risk population (n = 1 489 300) | Average-risk population (n = 121 419) | Overall cohort (n = 1 610 719) | High-risk population vs average-risk population (reference), cumulative incidence ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | Cumulative incidence over 24 wk (95% CI), events per 10 000 personsa | No. of events | Cumulative incidence over 24 wk (95% CI), events per 10 000 personsa | No. of events | Cumulative incidence over 24 wk (95% CI), events per 10 000 personsa | ||

| Breakthrough COVID-19 (n = 20 138) | |||||||

| Overall | 18 437 | 123.8 (122-125.6) | 1701 | 140.1 (133.6-146.9) | 20 138 | 125.0 (123.3-126.8) | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | 8071 | 108.4 (106-110.8) | 641 | 130.3 (120.5-140.7) | 8712 | 109.8 (107.5-112.1) | 0.8 (0.7-0.8) |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | 8882 | 143.4 (140.5-146.4) | 832 | 151.8 (141.7-162.4) | 9714 | 144.1 (141.3-147) | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) |

| 2 Doses of Ad26.COV2.S | 426 | 180.4 (163.8-198.2) | 46 | 167.5 (122.9-222.7) | 472 | 179.1 (163.4-195.8) | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) |

| Combination mRNAb | 633 | 105.7 (97.7-114.2) | 107 | 131.4 (107.8-158.6) | 740 | 108.8 (101.1-116.9) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) |

| Combination Ad26.COV2.S and mRNAc | 425 | 101.4 (92.0-111.4) | 75 | 114.9 (90.5-143.8) | 500 | 103.2 (94.4-112.6) | 0.8 (0.6-1.0) |

| Hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death (n = 1435)d | |||||||

| Overall | 1424 | 9.6 (9.1-10.1) | 11 | 0.9 (0.5-1.6) | 1435 | 8.9 (8.5-9.4) | 3.8 (2.2-6.7) |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | 614 | 8.2 (7.6-8.9) | 5 | 1 (0.3-2.4) | 619 | 7.8 (7.2-8.4) | 3.2 (1.4-7.2) |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | 714 | 11.5 (10.7-12.4) | 5 | 0.9 (0.3-2.1) | 719 | 10.7 (9.9-11.5) | 4.7 (2.0-11.0) |

| 2 Doses of Ad26.COV2.S | 22 | 9.3 (5.8-14.1) | 1 | NC | 23 | 8.7 (5.5-13.1) | NC |

| Combination mRNAb | 52 | 8.7 (6.5-11.4) | 0 | NC | 52 | 7.6 (5.7-10) | NC |

| Combination Ad26.COV2.S and mRNAc | 22 | 5.2 (3.3-7.9) | 0 | NC | 22 | 4.5 (2.8-6.9) | NC |

| Hospitalization with severe COVID-19 pneumonia or death (n = 541) d , e | |||||||

| Overall | 537 | 3.6 (3.3-3.9) | 4 | 0.3 (0.1-0.8) | 541 | 3.4 (3.1-3.7) | 3.4 (1.4-8.3) |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | 234 | 3.1 (2.8-3.6) | 2 | NC | 236 | 3 (2.6-3.4) | NC |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | 266 | 4.3 (3.8-4.8) | 2 | NC | 268 | 4 (3.5-4.5) | NC |

| 2 Doses of Ad26.COV2.S | 5 | 2.1 (0.7-4.9) | 0 | NC | 5 | 1.9 (0.6-4.4) | NC |

| Combination mRNAb | 22 | 3.7 (2.3-5.6) | 0 | NC | 22 | 3.2 (2-4.9) | NC |

| Combination Ad26.COV2.S and mRNAc | 10 | 2.4 (1.1-4.4) | 0 | NC | 10 | 2.1 (1-3.8) | NC |

Abbreviation: NC, not calculable.

Booster to 24 weeks, using model to make predictions at 24 weeks.

Combination mRNA included all possible combinations in which mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 were received.

This combination group received Ad26.COV2.S first then either mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2, or vice versa.

Death due to all causes within 30 days of breakthrough COVID-19 infection.

Severe pneumonia was defined as having mechanical ventilation or an intubation procedure during hospitalization.

Among 122 028 boosted participants with average risk (aged ≤65 years with no high-risk conditions), 1701 had breakthrough COVID-19 (140 events [95% CI, 133.6-140.7] per 10 000 persons), 11 had COVID-19 pneumonia or died (0.9 events [95% CI, 0.5-1.6] per 10 000 persons), and 4 developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia or died (0.3 events [95% CI, 0.1-0.8] per 10 000 persons) (Table 2). Hospitalization with mild, moderate, or severe disease occurred almost exclusively among high-risk populations. Among these hospitalized participants, 212 (15%) died.

In a random sample of 50 hospitalized participants within 30 days of postbreakthrough infection who did not have COVID-19 pneumonia, 15 patients (30%) were diagnosed by the care team as having COVID-19–related hospitalization (eAppendix 2 in the Supplement).

High-Risk Subgroups

Among high-risk populations (aged ≥65 years, with high-risk comorbid conditions, or with immunocompromising conditions), the 24-week cumulative incidence of hospitalization with pneumonia or death was 9.6 (95% CI, 9.1-10.1) per 10 000 persons (Table 2). Incidence of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death was as follows: among those aged 65 years or older, 1.9 (95% CI, 1.4-2.6) per 10 000 persons; for those with high-risk comorbid conditions, 6.7 (95% CI, 6.7-7.2) per 10 000 persons; and for those with immunocompromising conditions, 39.6 (95% CI, 36.6-42.9) per 10 000 persons (Table 3).

Table 3. Incidence of Breakthrough COVID-19, Hospitalization With COVID-19 Pneumonia, Hospitalization With Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia, and Death Following Vaccination and Booster in High-Risk Subgroups.

| COVID-19 outcomes by vaccination and booster | Persons with immunocompromising conditions (n = 158 684)a | Persons with high-risk nonimmunocompromising comorbid conditions (n = 1 133 785)b | Persons aged ≥65 y with no high-risk conditions (n = 196 831) | Immunocompromising conditions vs aged >65 y with no high-risk conditions (reference), cumulative incidence ratio (95% CI) | High-risk comorbid conditions vs aged >65 y with no high-risk conditions (reference), cumulative incidence ratio (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of events | Cumulative incidence in a 24-week period (95% CI), events per 10 000 persons | No. of events | Cumulative incidence in a 24-week period (95% CI), events per 10 000 persons | No. of events | Cumulative incidence in a 24-week period (95% CI), events per 10 000 persons | |||

| Breakthrough COVID-19 (n = 20 138) | ||||||||

| Overall | 3977 | 250.6 (243.0-258.4) | 13 083 | 115.4 (113.4-117.4) | 1377 | 70.0 (66.3-73.7) | 2.7 (2.4-2.9) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | 1776 | 223.3 (213.2-233.9) | 5641 | 100 (97.4-102.6) | 654 | 64.9 (60.0-70.1) | 2.5 (2.2-2.9) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | 1952 | 288.0 (275.5-300.9) | 6286 | 134.4 (131.2-137.8) | 644 | 76.7 (70.9-82.8) | 2.8 (2.5-3.3) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) |

| 2 Doses of Ad26.COV2.S | 64 | 307.2 (237.4-390.7) | 345 | 178 (159.8-197.6) | 17 | 79.4 (46.3-126.8) | 2.2 (1.1-4.5) | 1.6 (0.9-2.7) |

| Combination mRNAc | 115 | 211.6 (175.0-253.5) | 477 | 99.8 (91.1-109.1) | 41 | 61.6 (44.3-83.5) | 2.6 (1.5-4.7) | 1.2 (0.7-1.7) |

| Combination Ad26.COV2.S and mRNAd | 70 | 180.9 (141.3-228.0) | 334 | 96.1 (86.1-106.9) | 21 | 63.9 (39.6-97.5) | 2.3 (1.5-3.4) | 1.2 (0.9-1.6) |

| Hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death (n = 1435)e | ||||||||

| Overall | 629 | 39.6 (36.6-42.9) | 757 | 6.7 (6.2-7.2) | 38 | 1.9 (1.4-2.6) | 15.7 (11.4-21.6) | 2.6 (1.9-3.6) |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | 286 | 36.0 (31.9-40.4) | 314 | 5.6 (5.0-6.2) | 14 | 1.4 (0.8-2.3) | 20.4 (11.4-36.6) | 3.0 (1.8-5.1) |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | 314 | 46.3 (41.4-51.7) | 378 | 8.1 (7.3-8.9) | 22 | 2.6 (1.6-4.0) | 13.1 (8.5-20.1) | 2.3 (1.5-3.6) |

| 2 Doses of Ad26.COV2.S | 4 | 19.2 (5.2-49.1) | 18 | 9.3 (5.5-14.7) | 0 | NC | NC | NC |

| Combination mRNAc | 18 | 33.1 (19.6-52.3) | 32 | 6.7 (4.6-9.5) | 2 | NC | NC | NC |

| Combination Ad26.COV2.S and mRNAd | 7 | 18.1 (7.3-37.2) | 15 | 4.3 (2.4-7.1) | 0 | NC | NC | NC |

| Hospitalization with severe COVID-19 pneumonia or death (n = 541) e , f | ||||||||

| Overall | 265 | 16.7 (14.8-18.9) | 261 | 2.3 (2.0-2.6) | 11 | 0.6 (0.3-1.0) | 20.8 (12.0-36.1) | 3.0 (1.6-5.4) |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | 118 | 14.8 (12.3-17.8) | 110 | 1.9 (1.6-2.3) | 6 | 0.6 (0.2-1.3) | 18.2 (8.5-38.6) | 2.7 (1.1-5.2) |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | 135 | 19.9 (16.7-23.6) | 126 | 2.7 (2.2-3.2) | 5 | 0.6 (0.2-1.4) | 23.1 (9.6-55.9) | 3.1 (1.3-7.7) |

| 2 Doses of Ad26.COV2.S | 0 | NC | 5 | 2.6 (0.8-6.0) | 0 | NC | NC | NC |

| Combination mRNAc | 7 | 12.9 (5.2-26.5) | 15 | 3.1 (1.8-5.2) | 0 | NC | NC | NC |

| Combination Ad26.COV2.S and mRNAd | 5 | 12.9 (4.2-30.1) | 5 | 1.4 (0.5-3.4) | 0 | NC | NC | NC |

Abbreviation: NC, not calculable.

Immunocompromised was defined based on medications and history of cancer (see eAppendix 3 of the Supplement for list of medications).

As defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, older adults, people with medical conditions who are immunocompromised, and pregnant and recently pregnant people.

Combination mRNA included all possible combinations in which mRNA-1273 and BNT162b2 were received.

This combination group received Ad26.COV2.S first then either mRNA-1273 or BNT162b2, or vice versa.

Death due to all causes within 30 days of breakthrough COVID-19 infection.

Severe pneumonia was defined as having mechanical ventilation or an intubation procedure during hospitalization.

Compared with the subgroup of individuals aged 65 years or older with no high-risk conditions, the cumulative incidence ratio of hospitalization with pneumonia or death was larger among the subgroup of individuals with immunocompromising conditions (cumulative incidence ratio, 15.7 [95% CI, 11.4-21.6]) than among those with high-risk comorbidities (cumulative incidence ratio, 2.6 [95% CI, 1.9-3.6]). There were sufficient outcomes of hospitalization with pneumonia or death to compare high-risk subgroups within vaccination and booster groups who received 3 doses of mRNA-1273 and those who received 3 doses of BNT162b2, and these subgroup analyses showed similar cumulative incidence ratios as observed in the overall cohort. Other estimates of cumulative incidence in the 24-week period were described for those who received 2 doses of Ad26.COV2.S, a combination of mRNA vaccines, and a combination of Ad26.COV2.S and mRNA vaccines in Table 3.

Interaction of Incidence of Hospitalization With COVID-19 Pneumonia or Death With Time Since Vaccine Dose

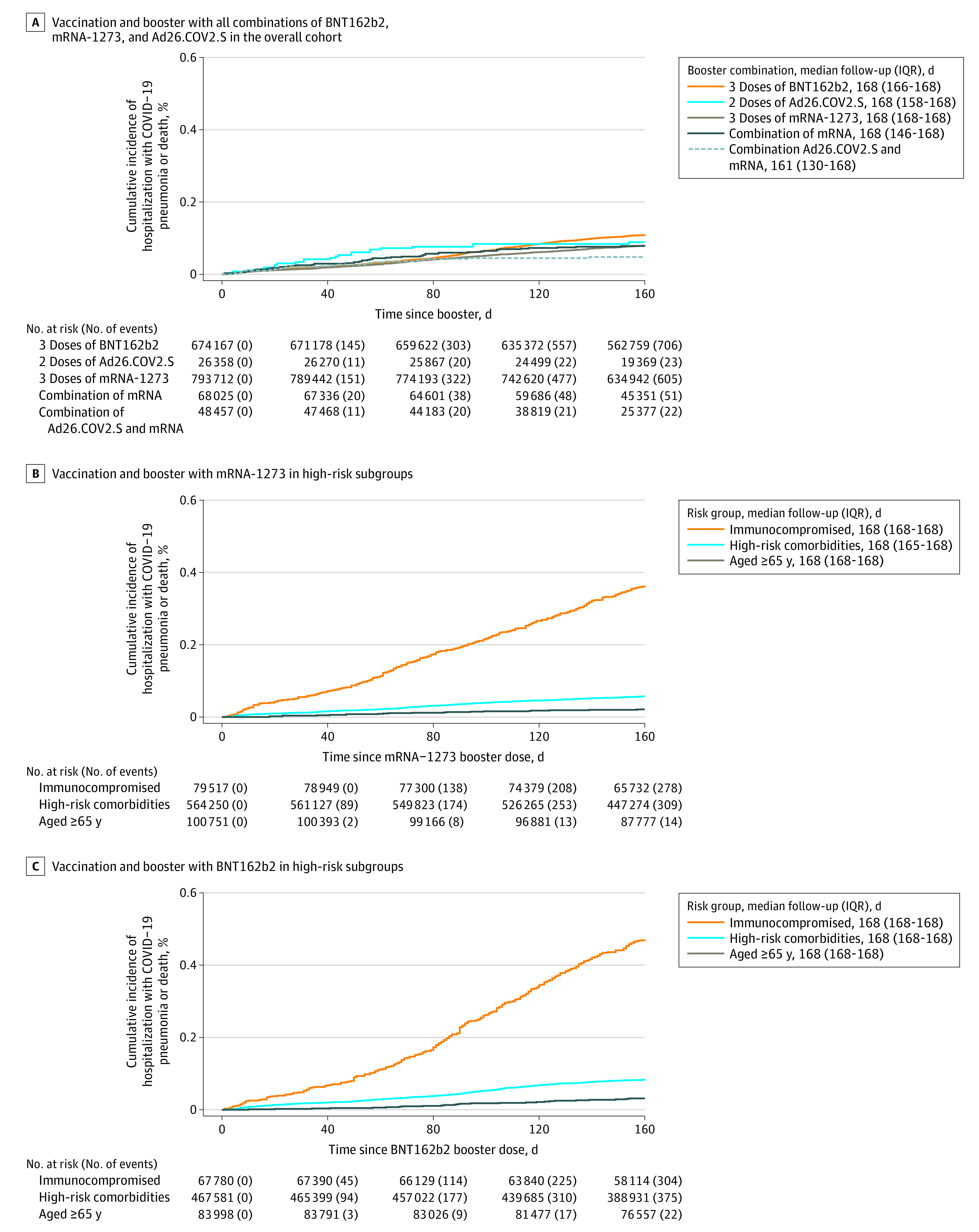

Cumulative incidence of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death over the 24-week period is shown in the Figure, demonstrating the low incidence among all vaccine and booster combinations in the overall cohort (Figure, A).

Figure. 24-Week Cumulative Incidence of Hospitalization With COVID-19 Pneumonia or Death Following Vaccination and Booster.

When considering the high-risk subgroups over time, there was graphical and statistical evidence of interaction of immunocompromising conditions with 50-day periods after receipt of booster (Figure, B-C; Table 4). Those with immunocompromising conditions had an additional risk of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death at 51 to 100 days and 101 to 150 days after receipt of booster compared with 1 to 50 days after receipt of booster compared with those without immunocompromising conditions (1-50 days vs 51-100 days: P = .004; 1-50 days vs 101-150 days: P < .001). This trend was consistently observed among those who received 3 doses of mRNA-1273 and 3 doses of BNT162b2. There was no significant interaction comparing populations with high-risk nonimmunocompromising comorbid conditions against those without these conditions over postbooster time.

Table 4. Subgroup Analysis of Hospitalization With COVID-19 Pneumonia Following Vaccination and Booster by Time Since Boostera.

| Time since booster, d | Events per 10 000 persons (No. of boosted individuals) | Cumulative incidence ratio (95% CI) | Interaction P valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunocompromising conditions | Nonimmunocompromising conditions | Immunocompromising conditions vs nonimmunocompromising conditions (reference) | ||

| Overall | ||||

| 1-50 | 9.0 (158 684) | 1.9 (1 452 035) | 3.1 (2.6-3.8) | |

| 51-100 | 14.3 (156 503) | 2.0 (1 435 757) | 4.6 (3.5-6.0) | .004 |

| 101-150 | 13.9 (151 662) | 1.5 (1 393 029) | 6.0 (4.4-8.0) | <.001 |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | ||||

| 1-50 | 8.9 (79 517) | 1.6 (714 195) | 3.8 (2.7-5.3) | |

| 51-100 | 12.7 (78 464) | 1.7 (706 613) | 4.9 (3.3-7.4) | .22 |

| 101-150 | 11.9 (76 188) | 1.2 (687 032) | 6.8 (4.5-10.4) | .006 |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | ||||

| 1-50 | 8.9 (67 780) | 1.9 (606 387) | 2.8 (2.2-3.8) | |

| 51-100 | 16.7 (67 039) | 2.4 (601 096) | 4.4 (3.0-6.4) | .02 |

| 101-150 | 17.5 (62 255) | 2.2 (585 770) | 5.1 (3.6-7.4) | .002 |

| High-risk nonimmunocompromising comorbid conditions | Aged ≥65 y and no high-risk comorbid conditions | High-risk nonimmunocompromising comorbid conditions vs aged ≥65 y and no high-risk comorbid conditions (reference) | ||

| Overall | ||||

| 1-50 | 2.2 (1 133 785) | 0.5 (196 831) | 2.7 (1.2-5.7) | |

| 51-100 | 2.4 (1 120 244) | 1.0 (195 426) | 1.3 (0.5-3.2) | .12 |

| 101-150 | 1.8 (1 085 313) | 0.4 (192 232) | 2.4 (0.8-7.0) | .86 |

| 3 Doses of mRNA-1273 | ||||

| 1-50 | 1.8 (564 250) | 0.5 (100 751) | 2.1 (0.8-5.7) | |

| 51-100 | 2.1 (557 893) | 0.7 (100 007) | 1.7 (0.5-6.2) | .72 |

| 101-150 | 1.4 (541 665) | 0.4 (99 811) | 4.0 (0.7-22.7) | .47 |

| 3 Doses of BNT162b2 | ||||

| 1-50 | 2.4 (467 581) | 0.5 (83 998) | 2.7 (0.8-9.2) | |

| 51-100 | 2.9 (463 190) | 1.3 (83 591) | 1.2 (0.3-4.7) | .25 |

| 101-150 | 2.7 (450 865) | 1.1 (82 486) | 2.0 (0.5-8.8) | .69 |

Results presented are drawn from fully adjusted Cox proportional hazards models that included an interaction term between risk group and an indicator variable for 50-day period since receipt of booster dose. Overall group includes all vaccination and booster combinations. Groups receiving 2 doses of Ad26.COV2.S, combination mRNA, and combination Ad26.COV2.S and mRNA were omitted from subgroup analyses due to insufficient sample sizes.

Calculated via 2-point comparison (51-100 days vs 1-50 days and 101-150 days vs 1-50 days) for the interaction of days and immunocompromising or nonimmunocompromising conditions.

The risk of breakthrough COVID-19 and hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death was higher during Omicron-predominant than Delta-predominant periods, although the magnitude of effect was attenuated in hospitalized participants (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this national US cohort of adults receiving care at VHA facilities, the overall risk of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death was low across vaccine and booster types. The 24-week observation period occurred while a series of SARS-CoV-2 variants were predominant in the US, including the Delta variant and the Omicron BA.1, BA.2, and BA.2.12.1 variants,22 suggesting that boosters continued to provide protection against severe illness despite viral evolution.

Previous studies have demonstrated evidence of booster effectiveness,7 but data on severe COVID-19 illness among high-risk populations has been lacking. Although high-risk populations in this study were more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia or die than average-risk populations, immunocompromised individuals accounted for much of the risk associated with the high-risk populations. After 50 days, incidence of hospitalization disproportionately increased among the immunocompromised population; protection against severe illness waned in this high-risk subgroup but did not wane in other populations, including those aged 65 years or older and those with high-risk comorbid conditions. A second booster dose within this study period of 24 weeks would have been unlikely to provide additional protection against severe illness except perhaps among immunocompromised populations, who may have received a benefit as early as 50 days after the first booster dose.

This study focused on COVID-19 pneumonia as a specific outcome, which was verified by ICD-10 code and chart review. Although almost all COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness studies use hospitalization together with a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 as an indicator of severe COVID-19 disease,3,4,23 this outcome has limited specificity, putting its value in question. In US hospitals and the public setting, SARS-CoV-2 testing has become part of routine screening for many reasons, including preoperative protocols, vaccine exemptions, and hospital admission; and determining whether a SARS-CoV-2–positive test was related to the reason for hospitalization has led to uncertainty in the classification of severe COVID-19 disease.

The use of COVID-19 pneumonia as the primary outcome in this study helped to minimize potential misclassification bias. Furthermore, pneumonia represents the most frequent cause of COVID-19–related hospitalization, resulting in severe illness, acute respiratory distress syndrome, mechanical ventilation, and death.24 Capturing this outcome over various COVID-19 surges and vaccine combinations may provide a consistent understanding of vaccine effectiveness.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, unboosted or unvaccinated populations were not included because a robust body of evidence has demonstrated the effectiveness of vaccine boosters, and there is a risk of measurement error and bias to the null given the possibility that unreported vaccination and boosters can occur. Second, potential confounders such as COVID-19 exposure behaviors could not be measured. Third, subgroups such as nursing home residents were excluded so that the findings could have greater generalizability to community-dwelling individuals living in the US. However, the boosted study population comprised predominantly White men, so even though there were substantial absolute numbers of boosted women and African American and Latino participants, inferences to subpopulations (eg, sex, race, and ethnicity) should be approached with caution. Fourth, VHA distributed mRNA vaccine types based on facility-specific factors. Fifth, it is unknown how these results might apply to emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2 or to the new bivalent booster vaccines.

Conclusions

In a US cohort of patients receiving care at Veterans Health Administration facilities during a period of Delta and Omicron variant predominance, there was a low incidence of hospitalization with COVID-19 pneumonia or death following vaccination and booster with any of BNT162b2, mRNA-1273, or Ad26.COV2.S vaccines.

eAppendix 1. COVID-19 Pneumonia Ascertainment Using a Combination Text-Processing Facilitated Chart Review and ICD Codes

eAppendix 2. Reasons for Hospitalization

eAppendix 3. Variable Definitions

eFigure 1. Cohort Selection in a Study of U.S. Veterans Who Received Booster Vaccination for COVID-19

eFigure 2. Map of VA Regions

eTable 1. Incidence of Hospitalization With COVID-19 Pneumonia/Death Following Vaccination and boosters With Follow-up Time Ending on Date of 4th Dose, by Overall Cohort and Immunocompromised Subgroup

eTable 2. Characteristics of the Boosted Cohort by Combination of Vaccination Series

eTable 3. Characteristics of Cohort by Outcome

eTable 4. Incidence of Outcomes Following Vaccination and Booster With mRNA-1273 x3, BNT162b2 x3, and Ad26.COV2.S x2 by Delta Variant vs Omicron Variant Eras

References

- 1.Tenforde MW, Self WH, Adams K, et al. ; Influenza and Other Viruses in the Acutely Ill (IVY) Network . Association between mRNA vaccination and COVID-19 hospitalization and disease severity. JAMA. 2021;326(20):2043-2054. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.19499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tai CG, Maragakis LL, Connolly S, et al. Association between COVID-19 booster vaccination and Omicron infection in a highly vaccinated cohort of players and staff in the National Basketball Association. JAMA. 2022;328(2):209-211. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.9479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Raddad LJ, Chemaitelly H, Ayoub HH, et al. Effect of mRNA vaccine boosters against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection in Qatar. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(19):1804-1816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2200797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dickerman BA, Gerlovin H, Madenci AL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines in US veterans. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(2):105-115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2115463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bajema KL, Dahl RM, Prill MM, et al. ; SUPERNOVA COVID-19 Surveillance Group; Surveillance Platform for Enteric and Respiratory Infectious Organisms at the VA (SUPERNOVA) COVID-19 Surveillance Group . Effectiveness of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines against COVID-19–associated hospitalization—five Veterans Affairs medical centers, United States, February 1–August 6, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(37):1294-1299. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Britton A, Fleming-Dutra KE, Shang N, et al. Association of COVID-19 vaccination with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection by time since vaccination and Delta variant predominance. JAMA. 2022;327(11):1032-1041. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Accorsi EK, Britton A, Fleming-Dutra KE, et al. Association between 3 doses of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and symptomatic infection caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants. JAMA. 2022;327(7):639-651. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Use of COVID-19 vaccines in the United States: interim clinical considerations. Updated February 10, 2021. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinical-considerations.html

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccines including boosters. Updated April 1, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/booster-shot.html

- 10.US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development . VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure Corporate Data Warehouse. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm

- 11.DuVall S, Scehnet J. Introduction to the VA COVID-19 Shared Data Resource and its use for research. US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development. April 22, 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/cyberseminars/catalog-upcoming-session.cfm?UID=3810

- 12.Coronavirus in the US: latest map and case count. New York Times. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html

- 13.VA Phenomics Library of the Department of Veterans Affairs . COVID-19: ORDCovid Case Detail. May 25, 2022. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3814

- 14.Chapman AB, Peterson KS, Turano A, Box TL, Wallace KS, Jones M. A natural language processing system for national COVID-19 surveillance in the US Department of Veterans Affairs. ACL Anthology. Published 2020. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://aclanthology.org/2020.nlpcovid19-acl.10.pdf

- 15.VA Phenomics Library of the Department of Veterans Affairs . COVID-19 Shared Data Resource. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3814

- 16.US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development . VA Information Resource Center (VIReC): Corporate Data Warehouse domain descriptions. August 2019. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.virec.research.va.gov/

- 17.Simon P, Ho A, Shah MD, Shetgiri R. Trends in mortality from COVID-19 and other leading causes of death among Latino vs White individuals in Los Angeles County, 2011-2020. JAMA. 2021;326(10):973-974. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.11945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schwandt H, Currie J, von Wachter T, Kowarski J, Chapman D, Woolf SH. Changes in the relationship between income and life expectancy before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, California, 2015-2021. JAMA. 2022;328(4):360-366. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.10952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development . VIReC database and methods seminar: assessing race and ethnicity in VA data. April 5, 2021. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/cyberseminars/catalog-upcoming-session.cfm?UID=3965

- 20.US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development . Assessing race and ethnicity in VA data. Accessed September 19, 2022. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars/archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=3784

- 21.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457-481. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID data tracker: United States: variant proportions. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#nowcast-heading

- 23.Madhi SA, Kwatra G, Myers JE, et al. Population immunity and Covid-19 severity with Omicron variant in South Africa. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(14):1314-1326. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Attaway AH, Scheraga RG, Bhimraj A, Biehl M, Hatipoğlu U. Severe covid-19 pneumonia: pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ. 2021;372(436):n436. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. COVID-19 Pneumonia Ascertainment Using a Combination Text-Processing Facilitated Chart Review and ICD Codes

eAppendix 2. Reasons for Hospitalization

eAppendix 3. Variable Definitions

eFigure 1. Cohort Selection in a Study of U.S. Veterans Who Received Booster Vaccination for COVID-19

eFigure 2. Map of VA Regions

eTable 1. Incidence of Hospitalization With COVID-19 Pneumonia/Death Following Vaccination and boosters With Follow-up Time Ending on Date of 4th Dose, by Overall Cohort and Immunocompromised Subgroup

eTable 2. Characteristics of the Boosted Cohort by Combination of Vaccination Series

eTable 3. Characteristics of Cohort by Outcome

eTable 4. Incidence of Outcomes Following Vaccination and Booster With mRNA-1273 x3, BNT162b2 x3, and Ad26.COV2.S x2 by Delta Variant vs Omicron Variant Eras