SUMMARY

The ability of poly(l-lysine)-conjugated and methylphosphonate-modified synthetic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides to protect susceptible host cells from the cytopathic effects of HIV-1 infection was studied. The abundance of viral antigens in oligomer-treated cultures indicated that the oligomers did not significantly affect viral infectivity. Similarly, no significant effects on relative viral RNA accumulation were apparent. The presence of poly(l-lysine)-modified oligomer complementary to the HIV-1 splice donor site resulted in a significant reduction in the production of viral structural proteins and virus titre in infected cultures. In addition, these cells were protected from HIV-1-mediated cytopathic effects while the other cultures rapidly succumbed to the cytotoxic effects of HIV-1 infection. The presence of poly(l-lysine)-conjugated oligomer resulted in the establishment of a persistent HIV-1 infection characterized by a highly productive virus infection in the absence of cell death while treatment of persistently infected cells with phorbol ester resulted in renewed cytopathicity. These results demonstrate the ability of synthetic antisense oligonucleotides to protect susceptible host cells from the cytopathic effects of HIV-1 infection.

INTRODUCTION

The depletion of circulating helper T lymphocytes following infection with the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is proposed to account for the susceptibility to opportunistic infections observed in AIDS patients. This is supported by the profound cytopathic effects exerted by HIV-1 on human CD4+ T lymphocytes in vitro (Barré-Sinoussi et al., 1983; Levy et al., 1984; Lifson et al., 1986a, b; Zagury et al., 1986). One obvious therapeutic strategy is to devise agents which specifically interfere with virus-mediated killing and prevent the depletion of the helper T lymphocyte population in AIDS patients. A novel approach to the prevention of HIV-1-induced cytopathicity lies in the use of antisense viral genes to interfere directly with virus replication and suppress the cytolytic effects of viral infection. Initial studies on prokaryotes (Coleman et al., 1985) and eukaryotes (Izant & Weintraub, 1984, 1985) have demonstrated that antisense RNAs, generated by the transcription of sequences inserted in reverse orientation relative to various promoters, could be used for the specific regulation of gene expression. The majority of studies demonstrating the regulatory potential of antisense RNAs have transcribed antisense sequences from transiently expressed recombinant plasmids (Izant & Weintraub, 1984, 1985) or from stably integrated vectors (Kim & Wold, 1985). As an alternative approach, synthetic antisense oligodeoxynucleotides have attracted interest as potential anti-viral agents. Methylphosphonate oligodeoxyribonucleotides complementary to the NS protein initiation codon of vesicular stomatitis virus (Agris et al., 1986) or to the splice acceptor site of herpes simplex virus type 1 pre-mRNA (Smith et al., 1986) were able to reduce virus titres dramatically in infected cells although high concentrations, 150 μm and 75 μm respectively, were required for the inhibitory effect. Synthetic oligonucleotides complementary to HIV-1 have now been used to inhibit virus replication and expression of viral antigens in infected cultured cells (Zamecnik et al., 1986) although the possible protective effects of the oligomers against viral cytopathic effects were not discussed. Conjugation of oligodeoxyribonucleotides to the ε-amino groups of poly(l-lysine) apparently increases the efficiency with which the conjugated oligomers reach the target such that concentrations as low as 100 nm in the culture medium inhibit vesicular stomatitis virus protein synthesis and virus replication (LeMaitre et al., 1987).

We have compared the ability of poly(l-lysine)- and methylphosphonate-conjugated oligomers complementary to HIV-1 splice donor sequences to confer protection from viral cytopathic effects on susceptible host cells in culture. We demonstrated that poly(l-lysine)-conjugated oligomers have far greater protective properties against HIV-1-mediated cytopathicity than similar methylphosphonate-conjugated or unmodified antisense sequences. We have also demonstrated that restriction of viral replication using antisense sequences leads to a highly productive non-cytopathic HIV-1 infection which may complicate their effectiveness in the treatment of AIDS.

METHODS

Synthesis of oligonucleotides.

Antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides complementary to the viral long terminal repeat (LTR) splice donor sequence (nucleotides 180 to 198; S.D. oligomers) (Wain-Hobson et al., 1985) and to the first exon of the bipartite tat gene (nucleotides 5878 to 5896) were synthesized and deprotected on an Applied Biosystems DNA synthesizer using 1 μm column supports and phosphoroamidite chemistry, essentially as described by Schott (1985). The synthesized product was dried, rehydrated in 10 mm-triethylamine bicarbonate buffer (TEAB pH 7.5), and purified on a Sephadex G-50 column. The column fractions were monitored at 260 nm and the fractions containing the oligonucleotide were pooled and dehydrated.

The 3′-OH end of the synthetic oligodeoxyribonucleotide was modified by the addition of pCp by T4 RNA ligase and the 3′ phosphate was removed with alkaline phosphatase. Oxidation of the 3′-terminal ribose was achieved with sodium metaperiodate, and conjugation of the 3′-terminal ribose with poly(l-lysine) by sodium cyanoborohydride reduction as described by LeMaitre et al. (1987). The final product was purified over a Sephadex G-50 column, equilibrated and eluted with 10 mm-TEAB buffer. The sample was quantified by absorbance at 260 nm. The synthesis and characterization of oligodeoxyribonucleotide methylphosphonates was carried out by previously described methods (Murakami et al., 1985).

Cell culture and virus propagation and infection.

MT4 cells [human T cell leukaemia virus type 1 (HTLV-I)-transformed human leukaemic CD4+ cell line] were maintained at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 in RPMI 1640 (Gibco) supplemented with 15% foetal bovine serum, 7 mm-l-glutamine, 2 mm-HEPES, penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

The LAV-N1T strain of HIV-1 (Casareale et al., 1987) was maintained and purified as described previously (Stevenson et al., 1987). Cells harvested at the exponential growth phase were infected by addition of virus-containing medium [1 × 106 reverse transcriptase (RT) units/ml] at a 1:10 dilution (106 cells/ml). After 1 h at 37 °C, cells were washed and resuspended at approximately 2 × 105 cells/ml in fresh medium containing antisense oligomers. At designated time intervals, culture samples were removed to determine cell count, viability (trypan blue exclusion), HIV-1 antigen expression (immunofluorescence assay), and RT activity in culture supernatants. The m.o.i. used typically results in HIV-1 antigen expression in 10 to 20% of CEM cells 2 days post-infection (p.i.).

Immunofluorescence staining.

Infected cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), spotted on glass slides, dried and fixed in acetone at −20 °C for 15 min. The fixed cells were reacted with serum from an asymptomatic HIV-1 seropositive haemophiliac (antibody titre 1:5120). After 30 min at 37 °C, cells were reacted with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-human IgG and virus antigen-positive cells were counted under epifluorescence illumination.

Cell surface marker analysis.

Cell samples (5 × 105) were washed with PBS and incubated at 4 °C for 30 min in the presence of unlabelled monoclonal T cell markers OKT4A, OKT4 (Ortho), or Leu-1 (Becton-Dickinson) followed by fluorescein-conjugated second antibody. Cell fluorescence was examined with an Ortho model 50H cytofluorograph.

Reverse transcriptase assay.

One ml samples of infected cell supernatants were filtered (0·8 μm) and pelleted at 4 °C for 2 h at 12000 g in a JA20 rotor. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of a reaction buffer containing 1 mm-Tris–HCl (pH 7·5), 0·2% Triton X-100, 5 mm-dithiothreitol, 60 mm-KCl, 10 mm-MgCl2, 50 μg/ml poly(A), 6 μg of oligo(dT)12–18 (Collaborative Research) and 5 μCi of [3H]TTP (60 to 80 Ci/mmol; Amersham). After 1 h at 37 °C, the reaction mixture was spotted onto 0·45 μm filters (type HA; Millipore) and washed with 1% Na2HPO4/2·5% trichloroacetic acid, then with 70% ethanol, air dried and counted.

RNA/DNA isolation and analysis.

Total cellular RNA and genomic DNA were prepared by the CsCl–guanidine thiocyanate procedure (Chirgwin et al., 1979) and analysed as described previously (Stevenson et al., 1988).

Solution RNA hybridizations.

Quantification of HIV-1 RNA in infected cells was performed by a modified ribonuclease protection assay essentially as described by Pellegrino et al., (1987). Single-stranded antisense HIV-1 RNA probes of high specific activity were generated using T7 polymerase from a HindIII-linearized transcription plasmid (pGEM; Promega) containing the HIV-1 LTR enhancer/TAR sequences. Probe was purified by passage over a 1 ml Sephadex G50–150 column and hybridized to infected cell lysates in 5 m-guanidine thiocyanate under conditions of probe excess.

Immunoprecipitation analysis.

Infected cultures were 35S-labelled and cleared cell extracts immunoprecipitated as outlined previously (Stevenson et al., 1988).

RESULTS

Protection of infected MT4 cells from virus-mediated cytopathic effects

To examine the protective effects of the synthesized oligomers on HIV-1-infected cells in culture we chose the HTLV-I-transformed human cord line MT4 (Miyoshi et al., 1982) as the susceptible host cell. MT4 cells are characterized by their extreme sensitivity to viral cytopathic effects following HIV-1 infection, a property which has enabled their application in a quantitative viral plaque assay (Harada et al., 1985). Virus obtained from filtered supernatants of productively infected CEM cells (LAV N1T strain) (Casareale et al., 1985) was added to the MT4 cells for 1 h at 37 °C, then virus-containing medium was removed and replaced with medium containing the synthetic antisense deoxyribonucleotides.

The susceptibility of MT4 cells to HIV-1-mediated cytopathic effects was reflected in the rapid loss of viability following infection. At 2 days p.i., control MT4 cells were 50% virus antigen positive (Fig. 1a) while cell viability was approximately 20% (Table 1). By 4 days p.i., no viable cells remained in the infected cultures (Table 1) which had completely succumbed to viral cytopathicity.

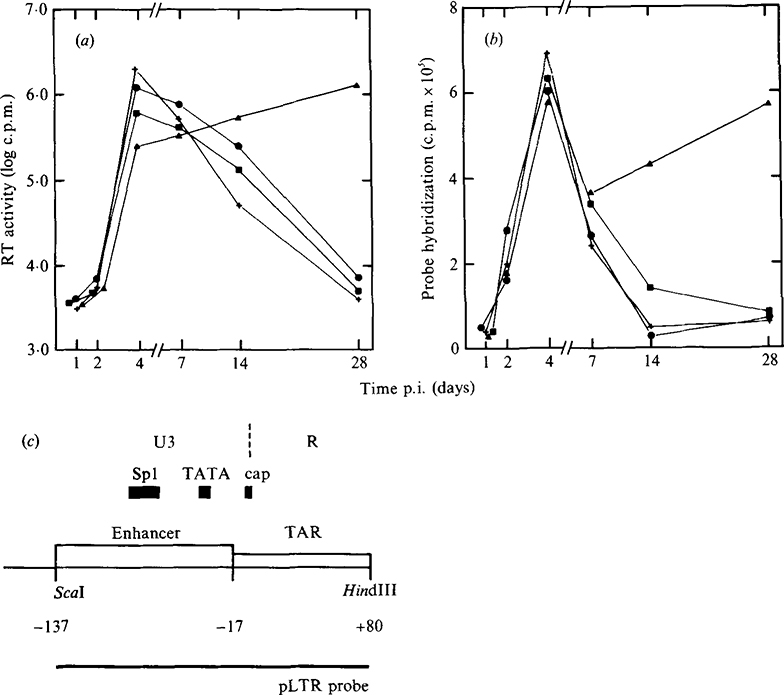

Fig 1.

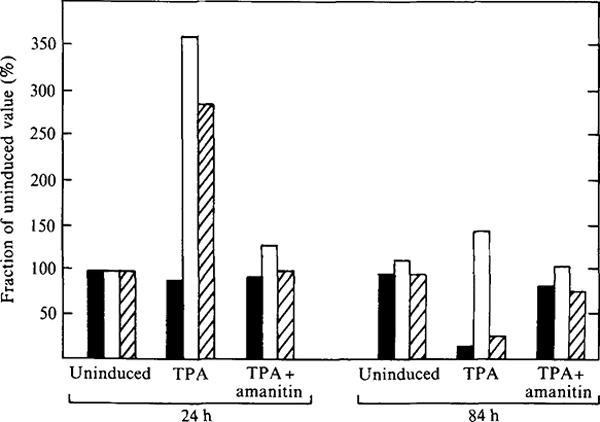

Kinetics of viral replication in infected MT4 cells in the presence of antisense oligomers. MT4 cells were infected with HIV-1 and incubated with antisense oligomers as described in Methods. At the indicated times following infection, aliquots of culture supernatant and infected cells were removed for analysis of RT activity (a) and viral RNA levels by solution RNA hybridization (b) using single-stranded RNA probes generated from the LTR region of HIV-1 as shown in (c). +, Cells cultured without oligomer; ●, cells plus unmodified S.D. oligomer; ■, cells plus methylphosphonate-modified S.D. oligomer; ▲, cells plus poly(l-lysine)-modified S.D. oligomer.

Table 1.

Protective effect of synthetic poly(l-lysine)-conjugated oligomers

|

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oligodeoxyribonucleotide | Concentration (nM)* | Viral binding site | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 14‡ | 28 |

| None | –§ | – | 50 | 50 | 60 | – | – | – | 22 | 5 | 0 | – | – | – |

| S.D. HIV-1 poly(l-lysine) | HIV splice donor site | >50 | >50 | 75 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 40 | 40 | 30 | 15 | 30 | 100 | |

| 5′-GCGTACTCACAGTCGCC-3′ | 200 | 281–298‖ | ||||||||||||

| tat HIV-1 poly(l-lysine) | 5′ End of HIV tat first exon | 50 | 50 | 60 | 60 | 80 | – | 40 | 20 | 15 | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| 5′-TCTAGGATCTACTGGCTG-3′ | 200 | 5378–5396‖ | ||||||||||||

| S.D. HIV-1 methylphosphonate | 1750 | – | – | >50 | >60 | – | – | – | – | 20 | 14 | 0 | – | |

| 200 | – | – | >50 | >60 | – | – | – | – | 20 | 5 | 0 | – | ||

| S.D. HIV-1 unmodified | 1750 | – | – | >50 | >50 | – | – | – | – | 10 | 8 | 0 | – | |

| 200 | – | – | >50 | >70 | – | – | – | – | 5 | 2 | 0 | – | ||

| Parvovirus H-1 poly(l-lysine) | 1000 | Parvovirus H-1 promoter | – | – | >50 | >70 | – | – | – | – | 15 | 10 | 0 | – |

| 5′-GGGGGGGTGGG-3′ | 200 | 4980–4991¶ | – | – | >50 | >70 | – | – | – | – | 20 | 10 | 0 | – |

A single dose of oligodeoxyribonucleotide was added 1 h after infection with HIV.

Values indicate percentage of positive MT4 cells as determined by indirect immunofluorescence.

Cells cultured without oligomer from this point.

– Not done.

Map position according to Wain-Hobson et al. (1985).

Map position from Rhode & Paradiso (1983).

The protective effects of the antisense oligomers was shown by their ability to prolong the viability of the infected MT4 cells. The most pronounced protective effect was observed in infected MT4 cells cultured with 200 nM-antisense oligomer complementary to the splice donor sequences (Table 1). The presence of the antisense oligomer did not prevent HIV-1 infection as shown by the high percentage of cells expressing HIV-1 antigens (Table 1) and the abundance of viral RNA in the infected culture (Fig. 1b). Despite being fully positive for viral antigens, cell viability was greater than 40% at days 2 and 3 p.i. and 30% by day 4. At this time, control cultures had completely succumbed to viral c.p.e. By day 7 p.i., 15% of the infected cells remained viable. Similar protective effects were observed in infected cells cultured in the presence of antisense oligomers complementary to the 5′ region of the HIV-1 tat first exon (Table 1). The specificity of oligomer action was confirmed by including a poly(L-lysine)-conjugated oligomer complementary to the parvovirus H-1 promoter of the 3′ non-translated region. The presence of this oligomer did not affect HIV-1 replication at concentrations as high as 1 μM (Table 1). In the case of HIV-1 S.D. oligomers, maximal protection from HIV-1-mediated cytopathicity was observed at 2 to 3 days p.i., after which time the protective effect was gradually lost. The transient nature of the protective effects of the oligomers probably reflects the half-life of the oligomers in culture since in the intracellular environment poly(l-lysine)-conjugated oligomers were partially degraded as early as 90 min after addition to cells in culture (results not shown). By comparison, splice donor oligomers conjugated with methylphosphonate or unmodified oligomer had relatively modest protective effects on infected MT4 cells. At concentrations of 1750 and 200 nM, infected MT4 cells rapidly succumbed to viral cytopathic effects resulting in complete destruction of the infected cell culture by 14 days p.i. However, untreated cells were destroyed by 4 days p.i. whereas oligomer treatment did afford a modest degree of protection to the infected cells.

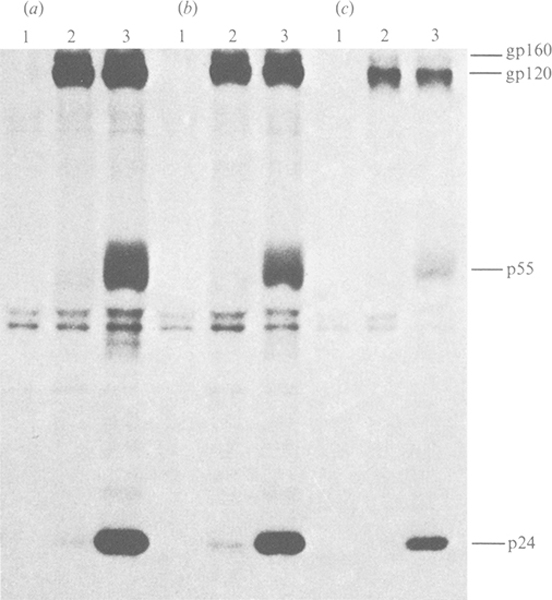

Effect of antisense oligomers on virus replication and production

At designated time points following infection of MT4 cells, the increase in intracellular viral RNA genomes and the release of progeny virus into culture supernatants were monitored by quantitative solution RNA hybridization and RT assay, respectively. The rapid increase in viral antigen-positive cells following HIV-1 infection (Table 1) was reflected by similar increases in viral RNA in the infected cells (Fig. 1a) and RT activity in the culture supernatants (Fig. 1b). In cultures incubated with poly(l-lysine)-conjugated S.D. oligomer a modest reduction in the relative levels of viral RNA in the initial days of infection was observed (Fig. 1a) while no similar effects could be observed with unmodified or methylphosphonate-modified sequences. Immunoprecipitation analysis of viral proteins at 4 days p.i. demonstrated that production of viral structural proteins was greatly reduced in the presence of poly(l-lysine)-conjugated antisense oligomer (Fig. 2). When compared with cultures treated with parvovirus H-1 poly(l-lysine)-conjugated oligomer (1 μM) (Fig. 2a), the levels of viral envelope glycoprotein (gp 120/160) and core proteins (p55/24) were greatly reduced in the presence of 200 nM-poly(l-lysine) S.D. oligomer (Fig. 2c). By comparison, a modest reduction was observed with similar concentrations of methylphosphonate-conjugated S.D. oligomer (Fig. 2b). The reduction in viral protein was accompanied by a significant decrease in virus production from cells cultured with poly(l-lysine) antisense S.D. oligomers (Fig. 1b). However, by 14 days p.i., RT levels in these cultures were similar to those observed in control cultures at maximal virus production (4 days p.i.). Again, significant inhibition of virus release was observed only in cultures containing poly(l-lysine)-modified oligomers and not in unmodified or methylphosphonate-conjugated oligomers.

Fig 2.

Inhibition of HIV-1 protein production in the presence of antisense oligomers. MT4 cells were infected and cultured with 1 μM parvovirus H-1 poly(l-lysine) oligomer (a); 200 nM-methylphosphonate-modified S.D. oligomer (b); and 200 nM-poly(l-lysine) S.D. oligomer (c). At 4 days p.i., cells were labelled for 3 h with [35S]methionine and [35S]cysteine and the viral proteins were immunoprecipitated with sera from a seronegative subject (lane 1) or sera from two HIV-1-seropositive asymptomatic haemophiliacs (lane 2,3) with titres of 5120 and 2560 respectively.

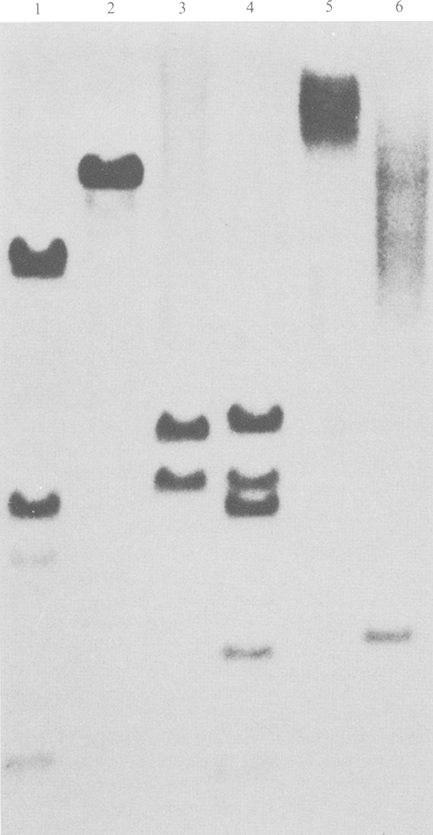

Induction of highly productive persistent infection by poly(l-lysine)-modified oligomers

By 14 days p.i., only cultures containing poly(l-lysine)-modified oligomers contained viable cells, which in the case of S.D. oligomer-treated cells resulted in outgrowth of MT4 cells. These cells were virus antigen-positive but apparently resistant to c.p.e. (Table 1), while transmission electron microscopy demonstrated a productive viral infection characterized by large amounts of budding and cell-associated viral particles (results not shown). Analysis of cellular DNA by Southern blot hybridization demonstrated the presence of large amounts of integrated viral DNA (Fig. 3). Use of the enzyme EcoRI which cuts the LAV N1T genome twice (Stevenson et al., 1988) allowed analysis of bridging fragments at the site of proviral integration. The presence of multiple hybridizing fragments in EcoRI DNA digests demonstrated multiple proviral integration sites indicating that the persistently infected cell line did not result from outgrowth of a single cell. By solution RNA hybridization analysis the relative levels of viral mRNA in the persistently infected host cells approximated that obtained from lytically infected MT4 cells at the peak of RT activity (Fig. 1b). This was reflected by high RT activity in the supernatants of persistently infected MT4 cells (0·8 × 106 to 1·0 × 106 c.p.m./ml). Virus released from persistently infected MT4 cells was able to induce a rapid cytopathic infection when added to fresh MT4 cultures demonstrating that the virus was not attenuated and retained full biological activity.

Fig. 3.

Southern blot analysis of HIV-1 DNA in persistently infected MT4 cells. Total cellular DNA was extracted from MT4 cells persistently infected with HIV-1, digested with BglII, HindIII, KpnI, PvuII, XbaI and EcoRI (lanes 1 to 6 respectively), blotted and hybridized with an HIV-1-specific genomic-length DNA probe.

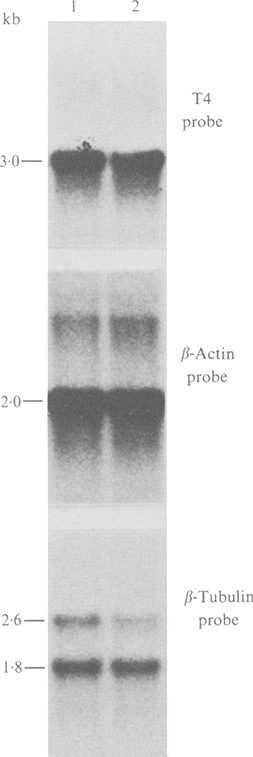

Induction of cytopathic effect in persistently infected MT4 cells

The CD4 molecule is the receptor by which HIV-1 gains entry into the host cell (Dalgleish et al., 1984; Maddon et al., 1986). HIV-1 down-regulates the CD4 receptor resulting in a complete loss of expression of this cell surface antigen in certain persistently infected cell lines (Hoxie et al., 1986; Stevenson et al., 1987, 1988). Flow cytofluorimetric analysis of persistently infected MT4 cells demonstrated loss of expression of the CD4 receptor as visualized by OKT4 and OKT4a monoclonal antibodies. Reactivity with OKT4 and OKT4A monoclonal antibodies was reduced by almost 90% in persistently infected MT4 cells while reactivity with a marker common to all T cells (Leu-1) was unaffected (results not shown). Since the OKT4 antibody, which recognizes a CD4 epitope distinct from the HIV-1-binding epitope, did not react with persistently infected MT4 cells, blocking of the CD4 receptor on the cell surface by simple virus binding could not account for the observed loss of CD4 expression. In agreement with our previous findings (Stevenson et al., 1987, 1988), infected MT4 cells had abundant levels of CD4 mRNA as detected by Northern blot analysis of total cellular RNA from uninfected and persistently infected MT4 cells (Fig. 4) indicating a post-transcriptional mechanism for CD4 down-regulation. The use of β-tubulin and β-actin probes on duplicate filters confirmed the presence of equimolar amounts of RNA in each sample (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Northern blot analysis of the CD4 mRNA levels in uninfected (lane 1) and persistently infected (lane 2) MT4 cells. Total cellular RNA (20 μg/lane) was denatured and electrophoresed through agarose gels containing formaldehyde and transferred to nylon membranes. The T4 probe was 3·0 kb cDNA pT4B (Maddon et al., 1986) containing the translated portion of the CD4 gene. β-Actin (Gunning et al., 1983) and β-tubulin (Hall et al., 1983) probes demonstrate equivalent amounts of RNA analysed in each lane.

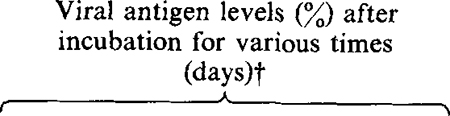

We next wanted to determine whether c.p.e. could be induced in the highly productive, persistently infected MT4 cells. The tumour-promoting agent 12-myristate 13-acetate (TPA) greatly enhances HIV-1 replication and c.p.e. (Harada et al., 1986) and directly stimulates transcription from the viral LTR (Kaufman et al., 1987). Addition of 1 ng/ml TPA to persistently infected MT4 cells resulted in a transient fivefold increase in virus production by 24 h after TPA addition (Fig. 5). The increase in virus production was reflected by a similar increase in viral RNA as determined by solution RNA hybridization using the HIV-1 LTR probe (Fig. 5). TPA induction of virus replication resulted in renewed cytopathic effect in infected MT4 cells, and by 84 h post-TPA addition almost 80% of the infected culture was dead or dying (Fig. 5) as determined by permeability to trypan blue. At the concentration used, TPA did not greatly affect the viability of uninfected MT4 cells (Fig. 5) although concentrations in excess of 5 ng/ml were toxic to both infected and uninfected MT4 cells. The effects of TPA were inhibited in the presence of 1 μg/ml α-amanitin (Fig. 5). α-Amanitin is a specific inhibitor of RNA polymerase II (Lindell et al., 1970) upon which the promoter elements of retroviruses are dependent. Thus the ability of TPA to stimulate virus replication and subsequent cell death was not due to secondary effects on membrane stability by TPA.

Fig. 5.

TPA-mediated stimulation of HIV-1 replication and cytotoxicity in persistently infected MT4 cells. Persistently infected cells were incubated with 1 ng/ml TPA plus α-amanitin (1 μg/ml) for 24 h followed by analysis of viability (trypan blue exclusion, shaded), RT (unshaded) and viral RNA (hatched) levels at 24 h and 84 h post-TP A addition. Values are expressed relative to those obtained from cultures incubated without TPA.

DISCUSSION

The results described here demonstrate that poly(l-lysine)-conjugated antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides can confer substantial protection from HIV-1-mediated c.p.e. on a cell line which is normally very sensitive to HIV-1-induced cytolysis. By comparison, methylphosphonate-modified oligomers or unmodified sequences had little effect on the response of infected MT4 cells to HIV-1 infection. The differences in ability of the antisense oligomers to protect infected cells from virus-mediated killing may be a function of their permeability to cells in culture. This may be affected by active uptake by the cell but is also probably a function of the relative lipid solubility imparted by the poly(l-lysine) moiety. Alteration in lipid solubility imparted by an attached poly(l-lysine) or methylphosphonate moiety would affect both the ability of the oligomer to permeate the cell membrane and its intracellular distribution. A consequence of the latter would be the binding of the oligomer to lipid-rich regions of the cell thus reducing the effective intracellular concentration of oligomer available for biological effect. However, selective localization of oligomer within regions of viral protein synthesis may serve to increase the likelihood of interaction between the antisense oligomer and its viral RNA target.

It must be stressed that the concentrations of poly(l-lysine)-conjugated oligomer required for an inhibitory effect were extremely low (200 nM). Although methylphosphonate-modified sequences were relatively ineffective at 1·75 μM, this is still 50 to 100 times lower than the concentration of methylphosphonate-modified antisense oligomers required to reduce titres of herpes simplex virus type 1 (Smith et al., 1986) or vesicular stomatitis virus (Agris et al., 1986) in infected cells.

The results presented here suggest that the antisense oligomers specifically interfere with protein translation. Significant reductions in viral protein production and virus titres were not reflected by similar effects on viral RNA accumulation. This may either indicate a ‘hybrid arrest’ mechanism for antisense oligomer action or a decreased stability of RNA/RNA hybrids formed after binding of antisense oligomers.

One can only speculate as to whether the ability of antisense oligomers to initiate persistence in HIV-1-infected CD4 cells will frustrate their therapeutic potential. The results presented here demonstrate that direct inhibition of virus replication by antisense oligomers inhibits the cytocidal properties of HIV-1 but leads to a persistent productive virus carrier state. Similar events may occur in vivo where prevention of cell killing using antisense oligonucleotides may lead to a highly infectious carrier state, which could be converted to a renewed cytocidal state following virus activation by, for example, a second virus infection or a change in the immunological status of the patient. One possible therapeutic application of the antisense oligonucleotide inhibition approach may be to restrict virus replication and thus retard subsequent T cell depletion sufficiently to allow a second treatment strategy which directly attacks the infected lymphocytes. In view of the ability of poly(l-lysine)-modified oligomers to prevent virus-mediated cytopathic effects at concentrations as low as 200 nM, novel modifications which further increase the efficacy of the antisense oligomer warrant investigation so as to make the antisense inhibition approach more feasible in the treatment of AIDS.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Rhode and G. Zon for assistance in synthesis of oligodeoxyribonucleotides, C. Meier and A. Wasiak for technical assistance, R. Wilson and C. Smith for electron micrographs and T. Chaudry and R. Springhorn for manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- AGRIS CH, BLAKE KR, MILLER PS, REDDY MP & TS’O POP (1986). Inhibition of vesicular stomatitis virus protein synthesis and infection by sequence-specific oligodeoxyribonucleoside methylphosphonates. Biochemistry 25, 6268–6275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARRÉ-SINOUSSI F, CHERMAN JC, REY R, NUGEYERE MT, CHAMARET S, GRUEST J, DAUGUET C, AXLER-BLIN C, BRUN-VEXINET F, ROUZIOUX C, ROZENBAUM W & MONTAGNIER L (1983). Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 220, 868–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASAREALE D, DEWHURST S, SONNABEND J, SINANGIL F, PURTILO D & VOLSKY DJ (1985). Prevalence of AIDS-associated retrovirus and anti-bodies among male homosexuals at risk for AIDS in Greenwich Village. AIDS Research 1, 407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CASAREALE D, STEVENSON M, SAKAI K & VOLSKY DJ (1987). A human T-cell line resistant to cytopathic effects of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1). Virology 156, 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIRGWIN JM, PRYZBYLA AE, MCDONALD RJ & RUTTER WJ (1979). Isolation of biologically active ribonucleic acid from sources enriched in ribonuclease. Biochemistry 18, 5294–5299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLEMAN J, HIRASHIMA A, INOKUCHI Y, GREEN PJ & INOUYE M (1985). A novel immune system against bacteriophage infection using complementary RNA (mic RNA). Nature, London 315, 601–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DALGLEISH AG, BEVERLEY PCL, CLAPHAM PR, CRAWFORD DR, GREAVES MF & WEISS RA (1984). The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature, London 312, 763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUNNING P, PONTE P, OKAYAMA H, ENGEL J, BLAU H & KEDDES L (1983). Isolation and characterization of full-length cDNA clones for human α, β, and γ-actin mRNAs: skeletal but not cytoplasmic actins have an aminoterminal cysteine that is subsequently removed. Molecular and Cellular Biology 3, 787–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL JL, DUDLEY L, DOBNER P, LEWIS SA & COWAN NJ (1983). Identification of two human β-tubulin isotypes. Molecular and Cellular Biology 3, 854–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARADA S, KOYONAGI Y & YAMAMOTO N (1985). Infection of HTLV-III/LAV in HTLV-I-carrying cells MT-2 and MT-4 and application in a plaque assay. Science 229, 563–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARADA S, KOYANAGI Y, NAKASHIMA H, KOBAYASHI N & YAMAMOTO N (1986). Tumor promoter, TPA, enhances replication of HTLV-III/LAV. Virology 154, 249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOXIE JA, ALPERS JD, RACKOWSKI JL, HUEBNER K, HAGGARTY BS, CEDARBAUM AJ & REED JD (1986). Alterations in T4 (CD4) protein and mRNA synthesis in cells infected with HIV-1. Science 234, 1123–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZANT JG & WEINTRAUB H (1984). Inhibition of thymidine kinase gene expression by antisense RNA: a molecular approach to genetic analysis. Cell 36, 1007–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IZANT JG & WEINTRAUB H (1985). Constitutive and conditional suppression of exogenous and endogenous genes by antisense RNA. Science 229, 345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUFMAN JD, VALANDRA G, RODERIQUEZ G, BUSHAR G, GIRI C & NORCROSS A (1987). Phorbol ester enhances human immunodeficiency virus-promoted gene expression and acts on a repeated 10-base pair functional enhancer element. Molecular and Cellular Biology 7, 3759–3766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM SK & WOLD BJ (1985). Stable reduction of thymidine kinase activity in cells expressing high levels of antisense RNA. Cell 42, 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEMAITRE M, BAYARD B & LEBLEU B (1987). Specific antiviral activity of a poly(l-lysine)-conjugated oligodeoxyribonucleotide sequence complementary to vesicular stomatitis virus N protein mRNA initiation site. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 84, 648–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVY JA, HOFFMAN AD, KRAMER SM, LANDIS JA, SHIMABUKURO JM & OSKIRO LS (1984). Isolation of lymphocytopathic retroviruses from San Francisco patients with AIDS. Science 225, 840–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIFSON JD, FEINBERG MB, REYES GR, RABIN L, BANAPOUR B, CHAKRABARTI S, MOSS B, WONG-STAAL F, STEIMER KS & ENGLEMAN EG (1986a). Induction of CD4-dependent cell fusion by the HTLV-III/LAV envelope glycoprotein. Nature, London 323, 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIFSON JD, REYES GR, MCGRATH MS, STEIN BJ & ENGLEMAN EG (1986b). AIDS retrovirus induced cytopathology: giant cell formation and involvement of the CD4 antigen. Science 232, 1123–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LINDELL TJ, WEINBERG F, MORRIS PW, ROEDER RG & RUTTER WJ (1970). Specific inhibition of nuclear RNA polymerase II by α-amanitin. Science 170, 447–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADDON PJ, DALGLEISH AG, MCDOUGAL IS, CLAPHAM PR, WEISS RA & AXEL R (1986). The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell 47, 333–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MIYOSHI I, TAGUCHI H, KUBONISHI I, YOSHIMOTO S, OHRAUKI Y, SHIRAISHI Y & AKAGI T (1982). Type-C virus producing cell lines derived from adult T-cell leukemia. Japanese Journal of Cancer Research 28, 219–228. [Google Scholar]

- MURAKAMI A, BLAKE KR & MILLER PS (1985). Characterization of sequence-specific oligodeoxyribonucleotide methylphosphonates and their interaction with rabbit globin mRNA. Biochemistry 24, 4041–4046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PELLEGRINO MG, LEWIN M, MEYER WA, LANCIOTTI RS, BHADURI-HAUCK L, VOLSKY DI, SAKAI K, FOLKS TM & GILLESPIE D (1987). A sensitive solution hybridization technique for detecting RNA in cells: application to HIV-1 in blood cells. Biotechniques 5, 452–459. [Google Scholar]

- RHODE SL & PARADISO PR (1983). Parvovirus genome: nucleotide sequence of HI and mapping of its genes by hybrid arrested translation. Journal of Virology 45, 173–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOTT ME (1985). A simple manual method for oligonucleotide synthesis. American Synthesis Biotechnology Laboratory Jan/Feb. [Google Scholar]

- SMITH CC, AURELIAN L, REDDY MP, MILLER PS & TS’O POP (1986). Antiviral effect of an oligo(nucleoside methylphosphonate) complementary to the splice junction of herpes simplex virus type I immediate early pre-mRNAs 4 and 5. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 83, 2787–2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEVENSON M, MEIER C, MANN AM, CHAPMAN N & WASIAK A (1988). Envelope glycoprotein of HIV-1 induces interference and cytolysis resistance in CD4+ cells: mechanism for persistence in AIDS. Cell 53, 483–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAIN-HOBSON S, SONIGO P, DANOS O, COLE S & ALIZON M (1985). Nucleotide sequence of the AIDS virus, LAV. Cell 40, 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAGURY D, BERNARD J, LEONARD R, CHEYNIER R, FELDMAN M, SARIN PS & GALLO RC (1986). Long-term cultures of HTLV-III-infected T-cells: a model of cytopathology of T-cell depletion in AIDS. Science 231, 850–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZAMECNIK PC, GOODCHILD J, TAGUCHI Y & SARIN PS (1986). Inhibition of replication and expression of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type III in cultured cells by exogenous synthetic oligonucleotides complementary to viral RNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, U.S.A. 83, 4143–4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]