To the Editor: Cases of recurrence of clinical symptoms of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) after completion of treatment with nirmatrelvir–ritonavir have been reported by researchers1 and in a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Advisory.2 The frequency and clinical implications of potential recurrence of coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) are unknown.

We present data on the occurrence of viral load rebound from a phase 2–3, double-blind, randomized, controlled trial (EPIC-HR3), which enrolled 2246 symptomatic, unvaccinated outpatient adults at high risk for progression to severe coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) within 5 days after symptom onset. Trial recruitment and sampling were performed from July 2021 through December 2021. Patients received nirmatrelvir (300 mg) plus ritonavir (100 mg) or placebo every 12 hours for 5 days. Over an average of 27 days, the patients in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group had a risk of Covid-19–related hospitalization or death from any cause that was 88% lower than that in the placebo group; there were no deaths in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and 13 deaths in the placebo group through day 34.

Nasopharyngeal swab samples were collected on the first day of enrollment (baseline) and then on trial days 3, 5, 10, and 14. (Details regarding sample collection are provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.) Recurrence of Covid-19 was defined according to prespecified criteria for viral load rebound: a half-log increase in viral load on day 10 or day 14 if only one value was available or on days 10 and 14 if both values were available. This definition was developed to evaluate resistance to nirmatrelvir.

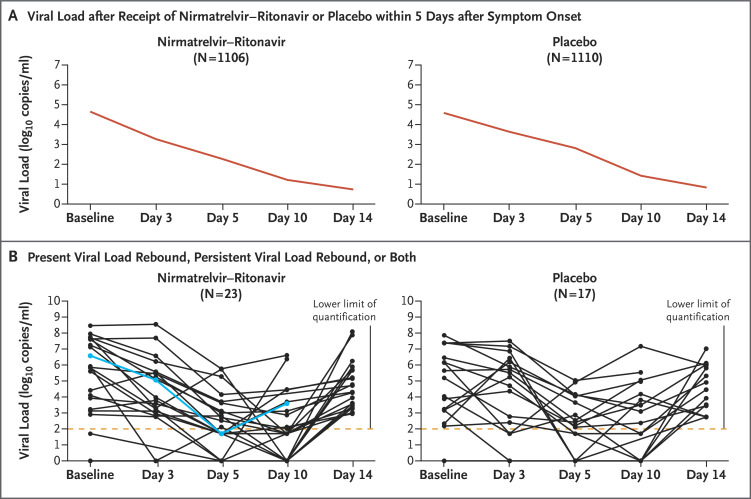

Data from patients who had viral load measurements at baseline and at least once after the administration of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir or placebo were available for 1106 patients in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and for 1110 patients in the placebo group (Figure 1A). By the data cutoff in December 2021, data from patients who had viral load measurements on day 5 and during the rebound period were available for 990 patients in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and for 980 patients in the placebo group. From baseline through day 14, viral load rebound occurred in 23 of 990 patients (2.3%) in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and in 17 of 980 (1.7%) in the placebo group (Figure 1B and Table S2). Results regarding viral load rebound were similar in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and the placebo group in analyses of the presence of coexisting illnesses, nirmatrelvir exposure, recurrence of moderate-to-severe Covid-19 symptoms (Fig. S1), the occurrence of hospitalization or death, baseline SARS-CoV-2 serologic status, and nirmatrelvir resistance (as assessed by SARS-CoV-2 Mpro gene or cleavage mutations). One patient in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group who had been admitted to the hospital had viral load rebound after being discharged. No hospitalizations occurred among the patients with viral load rebound in the placebo group, and no deaths were observed in either group with rebound.

Figure 1. Viral Load Rebound after Covid-19.

Shown are changes in the mean viral load among the study patients who received a course of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir or placebo within 5 days after the onset of symptoms of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection (Panel A). Also shown are data for patients with present or persistent viral load rebound in the two groups (Panel B). In Panel B, the lower limit of quantification of the reverse-transcriptase–polymerase-chain-reaction assay was 2 log10 copies per milliliter; the blue line indicates hospitalization of the patient.

Thus, the incidence of viral load rebound was similar in the nirmatrelvir–ritonavir group and the placebo group. The occurrence of viral load rebound was not retrospectively associated with low nirmatrelvir exposure, recurrence of moderate-to-severe symptoms, or development of resistance to nirmatrelvir. One potential limitation of this analysis is that the clinical trial was conducted during a period of the pandemic when most infections were caused by the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. However, more recent data indicate that nirmatrelvir–ritonavir is also effective against B.1.1.529 (omicron) variants.4 Another limitation of this analysis is the focus on identifying potential nirmatrelvir resistance. Viral load as determined by polymerase-chain-reaction assay does not translate directly to the presence of infectious virus and is not perfectly correlated with current or new clinical symptoms. Finally, omicron recurrence has also been observed in untreated patients.5 In the ACTIV-2/A5401 study, rebounds in viral load and clinical symptoms were relatively common among participants who had not received any antiviral agents.6 Our findings suggest that viral load rebound may be a feature of some SARS-CoV-2 infections and that the natural history of Covid-19 requires continued study.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on September 7, 2022, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Supported by Pfizer.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Gupta K, Strymish J, Stack G, Charness M. Rapid relapse of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection following early suppression with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. April 26, 2022. (https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-1588371/v1/48342d2c-b3ea-4228-b600-168fca1fded7.pdf?c=1650977883). preprint.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Alert Network. COVID-19 rebound after Paxlovid treatment. May 24, 2022 (https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2022/pdf/CDC_HAN_467.pdf).

- 3.Hammond J, Leister-Tebbe H, Gardner A, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir for high-risk, nonhospitalized adults with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1397-1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong CKH, Au ICH, Lau KTK, Lau EHY, Cowling BJ, Leung GM. Real-world effectiveness of molnupiravir and nirmatrelvir/ritonavir against mortality, hospitalization, and in-hospital outcomes among community-dwelling, ambulatory COVID-19 patients during the BA.2.2 wave in Hong Kong: an observational study. May 26, 2022. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.05.26.22275631v1). preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Stegger M, Edslev SM, Sieber RN, et al. Occurrence and significance of omicron BA.1 infection followed by BA.2 reinfection. February 22, 2022. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.02.19.22271112v1). preprint.

- 6.Deo R, Choudhary MC, Moser C, et al. Viral and symptom rebound in untreated COVID-19 infection. August 2, 2022. (https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2022.08.01.22278278v1). preprint.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.