Abstract

Low surface energy and hydrophobicity of polymethyl methactylate (PMMA) are the main disadvantages of this biomaterial. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of a new coating process on the surface characteristics and properties of PMMA. A combination of temperature and pressure was used for deposition of titanium dioxide (TiO2) on the surface of PMMA. The PMMA coated with TiO2 thin films and prepared by sputtering and non-coated PMMA were considered as control groups. The surface wettability, functional group, and roughness were determined by contact angle measurement, Fourier transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and 3D laser scanning digital microscopy, respectively. The flexural strength of coated and non-coated samples was measured using three-point bending test. The cell proliferation, attachment, and viability were determined using 3-(4,5-dimethyldiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, live and dead assay, scanning electron microscope (SEM), and DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining. The antifungal activity of TiO2 was also determined by examining the biofilm attachment of Candida albicans. The obtained results showed that TiO2 was successfully coated on PMMA. The contact angle measurement shows a significant increase of hydrophilicity in TiO2-coated PMMA. FTIR and roughness analysis revealed no loss of TiO2 from coated specimens following sonication. The cell viability after 7 days culturing on TiO2-coated specimens was more than the cell viability on the control groups. SEM images and DAPI staining showed that the total number of the cells increased after 7 days of seeding on TiO2-coated group, whereas it decreased gradually in both control groups. C. albicans attachment also decreased by 63% to 77% on the coated PMMA surface. Overall, this research suggested a new way for developing surface energy of PMMAs for biomedical applications.

Keywords: Hydrophilic PMMA, Coating, TiO2, Cell attachment, Antifungal activity

1. Introduction

Poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) is a synthetic polymer with a good biocompatibility, optical properties and a long-term mechanical stability used widely In the bone cement1, intraocular lenses2, artificial corneal Implants (keratopristhesis)3, bone substitutes4 and mandibular reconstruction5. For such applications, integration of the implant through interaction with the host cells is demanded. Failure to biointegrate and poor interaction between PMMA and cells can create a weak point at the tissue-implant interface which predisposes to development of complications such as infections, fibrotic tissue formation around implant and, therefore, implant failure6. Modification of the surface with bioactive molecules and chemicals is a promising approach to improve surface interactions. The cells can attach to the surface by interaction between the functional chemical groups of such bioactive chemicals and the membrane proteins of the cells. 7

Different coating materials and techniques were applied for modification of the PMMA surface. 8, 9 Hydrophilic behavior, antimicrobial activity, biocompatibility, appropriate thermal resistance, and electrical conductivity of titanium dioxide (TiO2) make it a suitable candidate for improving the surface properties of PMMA. TiO2 is widely used in orthopedic implants, keratoprosthesis,10 neural biosensor, and dental applications 8, 9. These coatings have additionally pulled in an incredible interest in terms of the potential for practical application proffered by their antimicrobial characteristics through different mechanisms. 11–13 TiO2 affects integrity and permeability of microbial membranes by generating reactive oxygen species and inhibits the microbial growth by reducing the expression of soluble protein and synthesis of nucleic acids.14 TiO2 also incites oxidization on excitation by UV irradiation 15–17. Moreover, TiO2 can improve hydrophilicity of the surfaces which causes them to be more resistant to microbial adhesion.8, 9

Different techniques have been applied for coating TiO2 including dip coating, DC magnetron sputter deposition18, electron beam evaporation19, filtered arc deposition20, and wet chemical method21. Stability and durability of coated TiO2 or the complexity of coating procedure are one of the main challenges of TiO2 coating in applying different techniques. Poor adhesion of coating can cause gradual cell detachment and thereby loss of implants. In this study, a procedure has been developed to coat TiO2 on the PMMA by applying pressure and temperature which can improve the TiO2 coating stability and durability. To the best of our knowledge, no TiO2 coatings have been reported on PMMA produced by applying pressure and temperature simultaneously. Here, after coating the TiO2 on PMMA, the stability, biocompatibility, antifungal effect, and cell adhesion to the surface were examined to detect the efficiency of the developed coating procedure.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Sample preparation

PMMA sheets (Plexiglas®, Arkema, USA) were punched into specimens (10 mm × 10 mm × 6 mm) and (5 mm × 5 mm ×6 mm). PMMA specimens were coated using two different procedures.

In the first procedure of titanium oxide coated 1 (TiO2-coated 1), thin films of TiO2 were coated on the specimen according to the previously published protocol. 22 Briefly, TiO2 films were prepared in a planar type of magnetron sputtering equipment (Yarenikane saleh-DRS320) on a circular plate of PMMA. the chamber was evacuated (3 × 10−6 Torre) prior to deposition. The distance of target and substrate was 25 mm. The titanium target was bombarded under a mixed atmosphere of argon (working gas), nitrogen and oxygen (O2) under a working pressure of 1.5 × 10−6 Torr. The substrate temperature increased to 150°C during deposition due to particle bombardment of the substrate. The specimens were then sputtered for 15 minutes and produced 300 nm of TiO2 thin films. In the second procedure of titanium oxide coated 2 (TiO2-coated 2), the specimens were put on a thick layer of TiO2 powder on the aluminum stub. Then a pressure about 980 N/m2 were applied on them in 80 °C for 60 minutes. Then the pressure was removed, and the temperature lets to decrease gradually from 80 °C to ambient temperature. The PMMA specimens without any treatment were considered as control group.

2.2. Sample characterization

2.2.1. Contact Angle Measurement

The hydrophilicity of the PMMA surface, TiO2-coated 1, and TiO2-coated 2 specimens was measured by sessile drop method. The average value of contact angle of three deionized water droplets was described with standard error (θ ± SE).

2.2.2. FTIR Spectroscopy

After sonication, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed to detect the chemistry of the coated and non-coated specimens using a spectrometer (Nicolet™ iS™ 5 FTIR Spectrometer) over a range of 4000–400 cm−1.

2.2.3. Surface roughness

To determine the stability of TiO2 coverings coated through procedure 1 and 2, the three coated specimens of each procedure were exposed to sonication in the Branson Ultrasonics at maximum power in 37°C for 1 hour. Then, their surface topography was analyzed using laser scanning confocal microscope (LEXT 3D MEASURING LASER MICROSCOPE OLS4000, USA). Using an objective lens X50, 405-nm laser beam spot combined with 0.5 nm z-axis resolution and a photomultiplier of 16-bit, surface profile and roughness data were obtained. Profile roughness was determined by measuring the arithmetical mean height of a line (Ra) and root mean square (RMS) (Rq). To determine an overall measure of the texture comprising the surfaces, parameters including the arithmetical mean height (Sa) and Root Mean Square Roughness (Sq) were analyzed. Roughness was measured on three specimens for every group of PMMA, TiO2-coated 1, and TiO2-coated 2.

2.2.4. Mechanical properties

The flexural strength of PMMA, TiO2-coated 1, and TiO2-coated 2 PMMA specimens with 10 × 5 × 6 mm3 (n=3) dimension was measured using three-point bending test using an Autograph AGS-X Series Precision Universal Tester (SHIMADZU; USA). The crosshead speed was adjusted at a 1 mm/min, then the flexural strength (σ) was calculated using following formula:

| (1) |

Where F is the applied maximum force, L, w, and d represent the length, width, and depth of the samples, respectively. The flexural strength was described with standard error (σ ± SE).

2.2.5. Biocompatibility assays

The viability of fibroblast cells on the bared PMMA and the TiO2-coated 1 and TiO2-coated 2 samples was studied using MTT assay. Briefly, the primary oral fibroblast extracted from normal human gingival tissues were cultured on the prepared specimens in 96-well microtiter plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/sample. The cell group cultured on the bared PMMA was considered as the control group. At predetermined time points, the cell culture medium was removed, and samples were washed with 1xPBS and incubated with 100 μL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT dye solution (SigmaAldrich, Cat. R8755) for 3 hours at 37 °C. Then, supernatant was discarded, and the formed formazan crystals were dissolved in 100 μL of DMSO, and the optical densities (OD) of the solutions were then analyzed using a Synergy HTX multi-mode reader (BioTek, USA) at 570 nm. The specimens without cells on them were considered as negative control. To eliminate the effect of titanium coating on producing dye, the results were normalized with the aforementioned negative control groups.

The percentage of live and dead cells of human fibroblast cells was determined using LIVE/DEAD ® Viability/Cytotoxicity Kit for mammalian cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Briefly, the specimens with 5 × 5 ×6 mm3 diameter were sterilized in ethanol 70% and washed with 1xPBS. Then, 104 viable fibroblast cells were seeded on each specimen. After one day of culturing the cells in the basal medium, the cells were washed with 1x PBS and exposed to the mixture solution of EthD-1 (4 μM) and calcein AM (2 μM) according to manufacturer’s instruction. After incubation, the cells sat at room temperature for 30 minutes and then the pictures were taken from the stained cells using the fluorescence microscope (EVOS FL Auto, life technologies, USA). The number of live and dead cells were detemined using ImageJ software on the images taken by fluorescence microscope.

2.2.6. DAPI staining

To determine the stability of cell attachment to the surface of different coated specimens, after a given time, the cells were washed with 1x PBS and stained with 4’,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole (DAPI) dye. After washing the specimens three times with 1x PBS, the images were prepared using the fluorescence microscope.

2.2.7. Morphology study

The surface morphology of the PMMA, TiO2-coated PMMA specimens and the cells cultured on them was characterized using scanning electron microscope with Energy Dispersive Spectrometer and Network Analyzer (JEOL USA Scanning Electron Microscopes). The uniformity dispersion of TiO2 on the surface of both TiO2-coated 1 and TiO2-coated 2 specimens was determined by detecting the existence of titanium (Ti). To prepare the specimens for microscopy, the samples were coated with gold and palladium using a sputter coater. To determine the morphology and distribution of the cells on the coated and non-coated PMMA samples, after culturing the cells for 7 days on them, they were washed with PBS1X and were fixed with Karnovsky’s Fixative at 4°C overnight. The samples were then dehydrated in graded ethanol solutions. After the samples were put on aluminum stub, the gold–palladium sputtered on their surface. The Images were then taken at an accelerating voltage of 15 kV using a scanning electron microscope.

2.2.8. Antimicrobial test

Candida albicans (ATCC 90028) was used for this test and the attachment and biofilm formation was measured. Briefly, after growing C. albicans on Sabouraud Agar (SDA), the suspension with a single colony of C. albicans was prepared in 1mL of Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (SDB) medium. Then, the cells were washed twice with 1X PBS, and centrifuged for 5 minutes. Subsequently, the pellet of the cells was resuspended in an appropriate fresh SDB to obtain OD of 9.5×10−2 at 625 nm. The attachment of C. albicans was examined by culturing 104 cells of C. albicans in 1 mL of SDB on the different specimens (n=3) in 12-well plates. The plate was placed on an orbital shaker and incubated at 37°C for 6 hours. Then, the specimens were rinsed in 1X PBS to obtain the non-adherent C. albicans cells from surfaces of the specimens. The non-adherent C. albicans cells in washing solution was then cultured on SDA at 37°C for 12 hours. Then, the number of viable C. Albicans was determined using plate-counting method.23, 24

The biofilm formation of C. albicans was examined by adding 3 mL of SDB to each well contained washed specimens and incubated at 37°C in aerobic conditions. The specimens after 12 hours were washed in 1X PBS and sonicated in deionized water for 30 seconds. The harvested non adherent C. albicans cells was then cultured on SDA at 37°C for 12 hours. Then, the number of viable C. Albicans was determined using plate-counting method.23, 24

2.3. Statistical analysis

The data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. To determine the significant variation between the cells cultured on different specimens, one-way ANOVA was used. The p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sample characterization

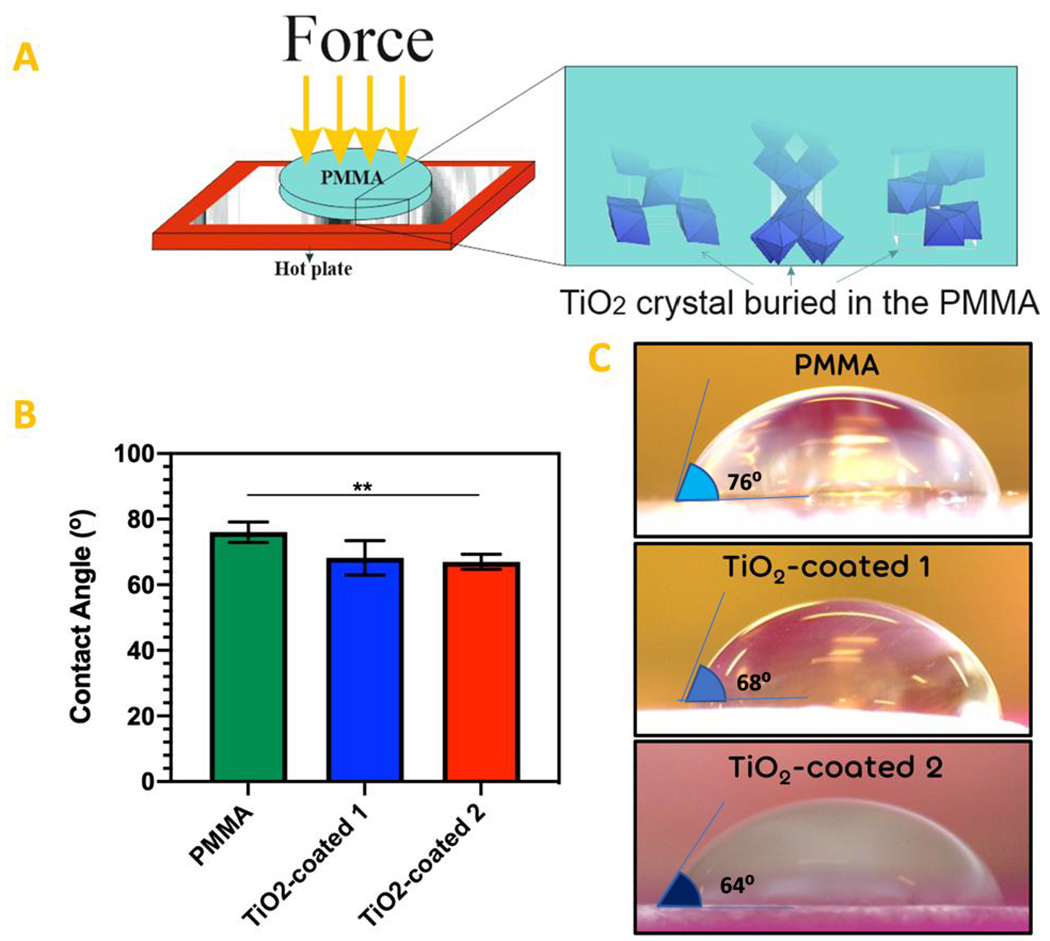

Contact angle measurements showed that the hydrophilicity of PMMA increased after TiO2 coating through both procedure 1 and 2. However, the difference of average contact angle value on PMMA is significant just in comparison to PMMA after coating through TiO2-coated2 procedure (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic procedure of TiO2 coating on the PMMA. (b) The results of contact angle measurement performed on the surface of the PMMA, TiO2-coated 1 and 2 specimens. (c) The images of contact angle droplets on the surface of the PMMA, TiO2-coated 1 and 2 specimens.

(** P value < 0.01)

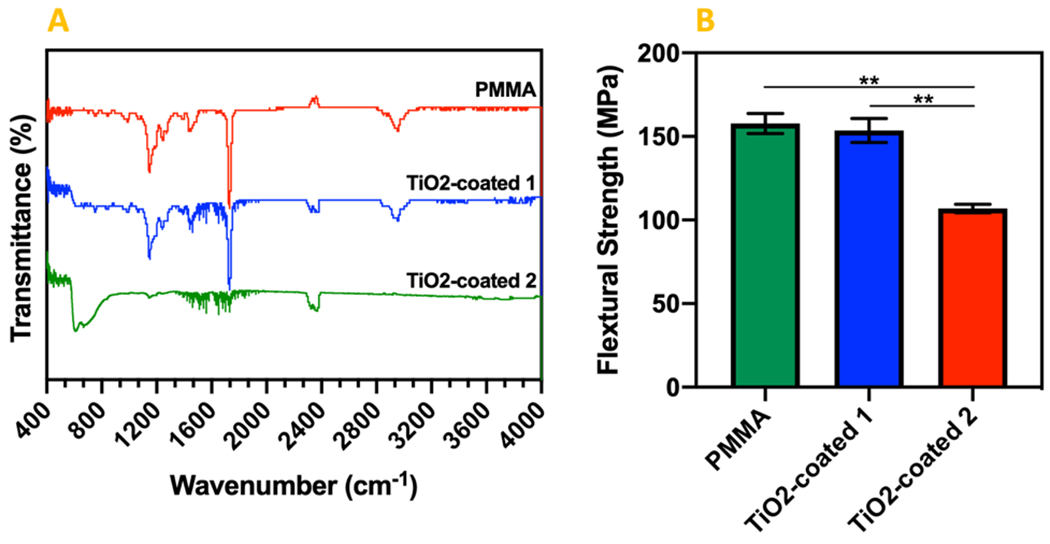

After exposing to sonication, the FTIR spectra of the non-coated PMMA, TiO2-coated PMMA through procedure 1 and 2, are depicted in Fig. 2. For PMMA, absorption bands were observed at 2993 cm−1 and 1730 cm−1, which are characteristic bands for PMMA. In TiO2-coated 1 samples, the strength of the peaks in these bands decreased, and there is not any peak at these absorption bands in TiO2-coated 2 samples. It may be due to covering the PMMA by TiO2. Vibrations of Ti-O and Ti-O-Ti framework was observed at 600 cm−1 in TiO2-coated 1 and with a stronger peak in TiO2-coated 2. The 2948 cm−1 peak in the TiO2-coated 1 and more intensely in TiO2-coated 2 decreases by increasing the TiO2 coating thickness25, 26. The stretching of (C-O) of the ester group was observed at 1140 cm−1. The peaks became flattened in TiO2-coated 2. It is due to binding CO to TiO2, and that caused the peak flattening25, 26.

Figure 2.

(a) FTIR Spectra for PMMA and TiO2-coated specimens through procedure 1 and 2. (b) The results of three-point bending test performed on the PMMA, TiO2-coated 1 and 2 specimens.

(** P value < 0.01)

The flexural strength of PMMA before and after TiO2 coating using procedure 1 was measured as 157.79 ± 5.99 MPa, and 153.54 ± 7.12 MPa, respectively (Fig. 2b). However, the difference was not statistically significant. The flexural strength of PMMA after coating using procedure 2 decreased significantly to 106.94 ± 2.54 MPa. The coating procedure 2 yields a thick layer of TiO2 particle on the surface which increased the depth (d) of the sample about 1 mm, whereas this thick coating layer is composed of particles which don’t have strong interaction with each other. Moreover, in procedure 2, some parts of TiO2 particles penetrate the PMMA sheet which can eliminate the integrity of the PMMA sheet in some regions near the surface. These alterations in the PMMA specimens can cause such a decrease in the flexural strength after TiO2 coating through procedure 2.

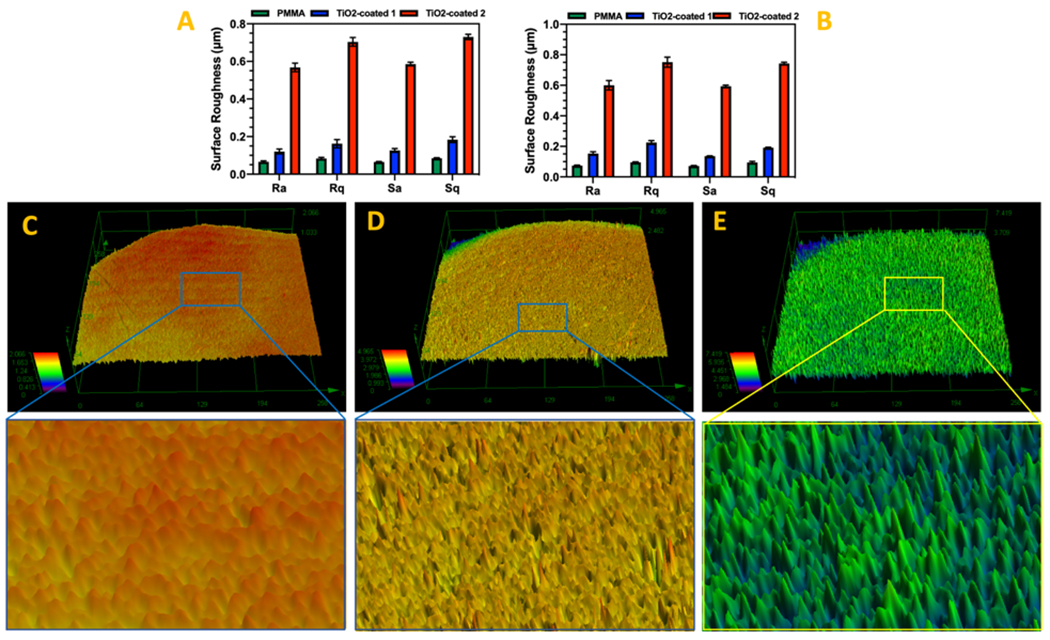

The roughness measurement showed that the roughness of specimens coated with TiO2 through procedure 2 is significantly more than TiO2-coated 1 and PMMA specimens. Moreover, the surface roughness of TiO2-coated 1 specimen was more than PMMA specimens. In fact, the mechanical characteristics and biological properties of the coatings could be constrained by the roughness of the coatings without impacting chemical structure of the substrate 27, 28. The surface roughness (Ra) changes for PMMA, PMMA TiO2-coated 1 and 2 specimens was measured (Fig. 3) before and after sonication. The mean surface roughness and RMS (Ra and Rq) of the different specimens did not change significantly after sonication. These results demonstrated that TiO2-coatings through both procedure 1 and 2 were able to stay stable after tension was applied on the surface of PMMA. The results confirmed the superior stability of coating 2 comparing to coating 1.

Figure 3.

Surface roughness changes of PMMA and TiO2-coated PMMA before (a) and after (b) sonication. The laser microscopy images taken from (c) PMMA, (d) TiO2-coated 1, and (e) TiO2-coated 2 specimens.

(Ra and Rq: The profile roughness parameters and Sa and Sq: The area roughness parameters)

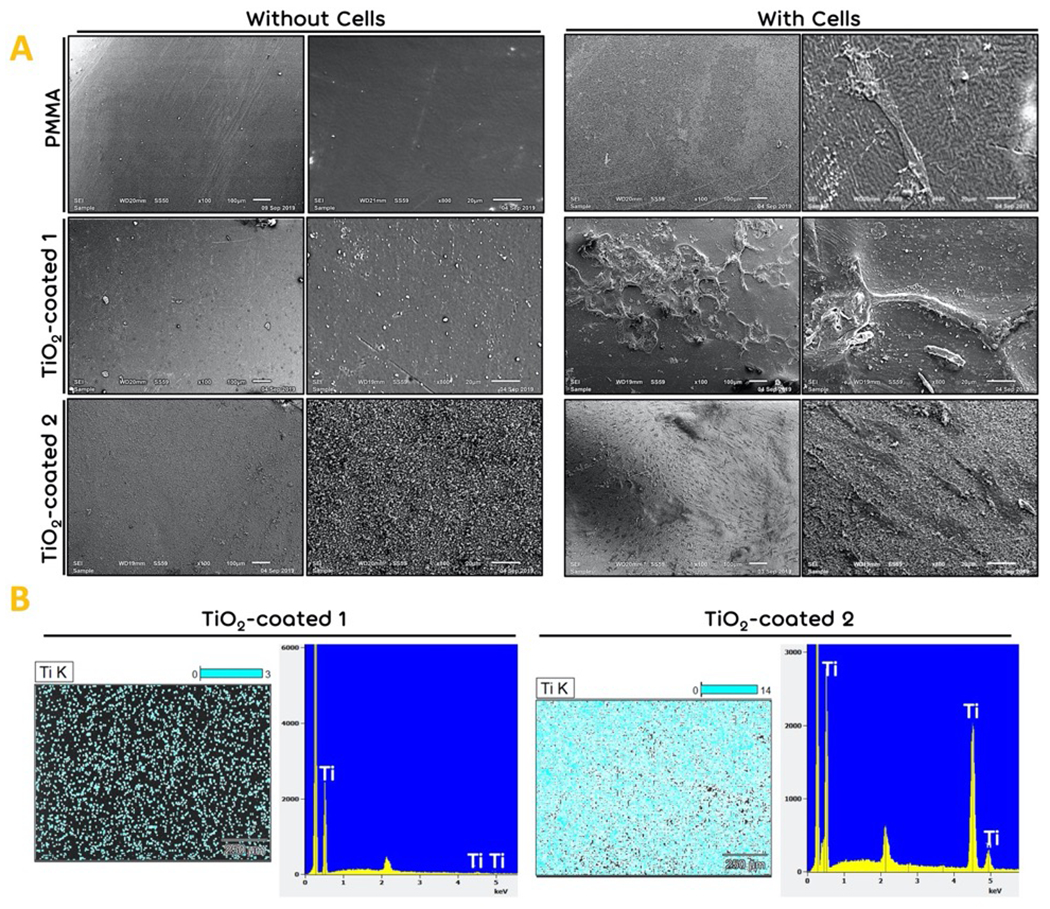

3.2. SEM/EDS observations

The SEM images of the TiO2-coated and non-coated PMMA surfaces showed in Fig. 4. As shown in Fig. 1, the cells could barely maintain their attachment to the surface after 7 days of cell culturing. In TiO2-coated 1 samples, the roughness of the surface is more detectable than bared PMMA. Here, although the cells showed stronger attachment compared with bared PMMA, they started to detach from the edges, and it seems that the cells distribution was not uniform all over the surface of TiO2-coated 1 samples. The roughness of the surface in TiO2-coated 2 samples is obviously more detectable than TiO2-coated 1 samples. Moreover, the cells uniformly distributed throughout the surface of the TiO2-coated 2 samples, and the cells spread and attached to the surface. EDS mapping showed the uniform distribution of elements related to TiO2 coating (Fig. 4b).

Figure 4.

The morphology analysis. (a) The SEM images of the bared PMMA (Control), TiO2-coated 1 and TiO2-coated 2 samples before and after fibroblast cell seeding for 14 days of cell culturing. (b) The EDS mapping of TiO2 coating. Blue dots demonstrated titanium.

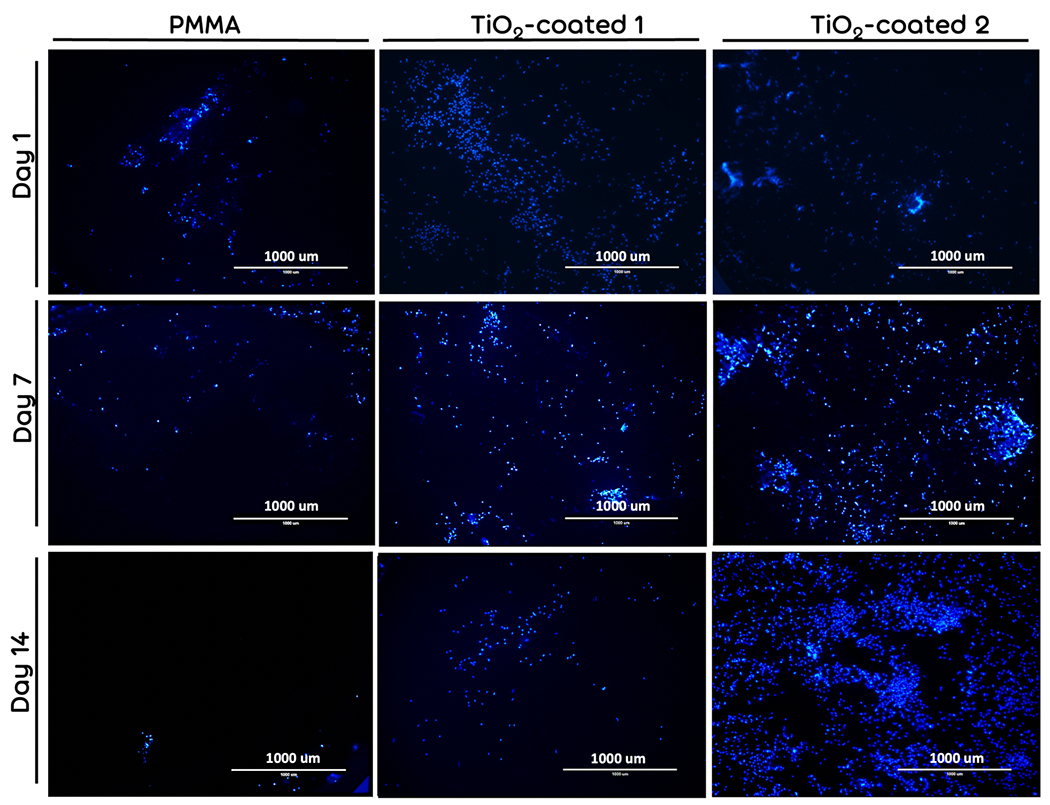

3.3. Stability of cell attachment assessment

DAPI staining showed that the total number of the cells decreased gradually on the bared PMMA and TiO2-coated 1 samples (Fig. 5). However, the total number of the cells increased after 7 day of cell culturing in TiO2-coated 2 samples. These results confirmed the results of SEM which may be due to a higher stability of the TiO2 on the surface coated through procedure 2 compared with procedure 1.

Figure 5.

The nucleous DAPI staining of fibroblast-seeded bared PMMA (Control), TiO2-coated 1, and TiO2-coated 2 specimens after 1 and 7, and 14 days of cell culturing.

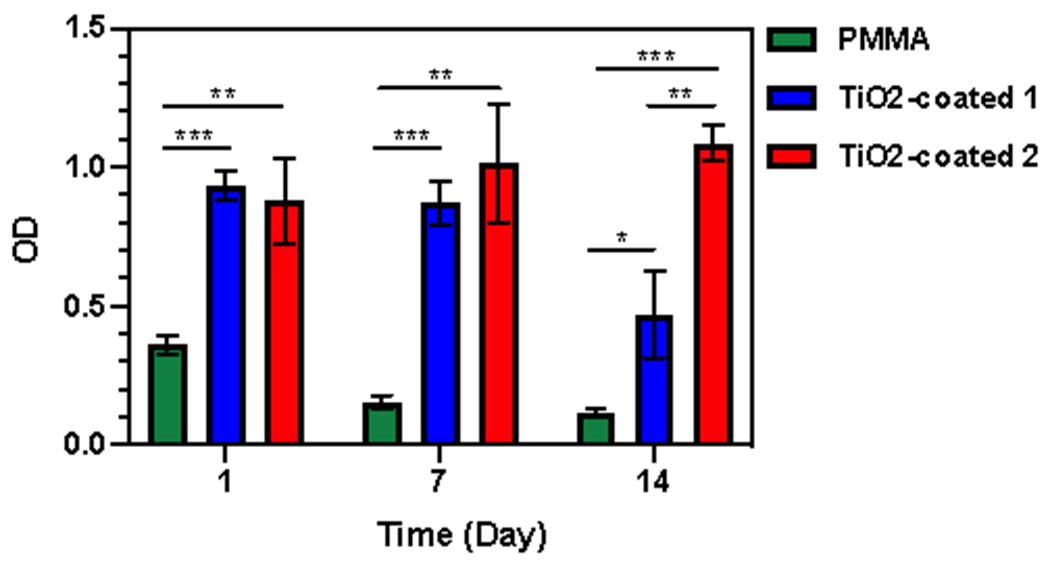

3.4. Biocompatibility study

The biocompatibility of the TiO2-coated specimens was examined by MTT assay. As the results show (Fig. 6), the viability of fibroblast cells cultured on the TiO2-coated and TiO2-coated 2 specimens was similar at 5 hours post cell seeding (day 0). On day 3, the viability of the cells on TiO2-coated 1 samples is less than TiO2-coated 2 samples, but the difference was not significant. On day 7, this difference became significant between TiO2-coated 1 and TiO2-coated 2 samples. These results confirm the results of SEM and DAPI staining which may be occurred because of a lower stability of coated TiO2 using TiO2-coating procedure 1. However, the cells cultured on bared PMMA showed a significant lower active metabolism on days 0, 3, and 7 compared to TiO2-coated groups. It might be because of the lower cell attachment characteristic of the bared PMMA compared with the TiO2-coated groups.

Figure 6.

Fibroblast cells viability on days 0, 3, and 7 days on bared PMMA (Control), TiO2-coated 1, and TiO2-coated 1. (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001)

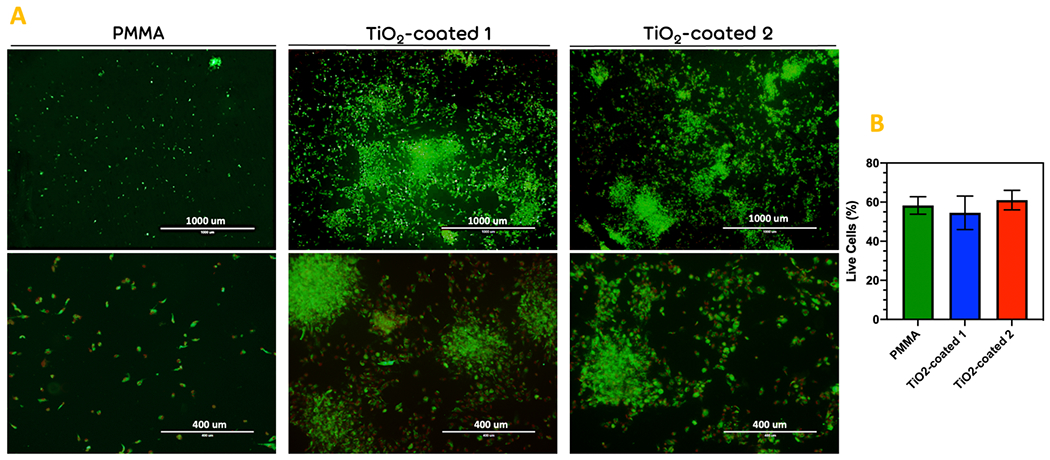

The effect of different coating procedures on viability of the fibroblast cells was determined using live and dead assay. the fibroblast seeded on the bared PMMA was determined as control group. The primary number of the cells seeded on the specimen was similar. As it has been shown in Fig. 7A, the total number of the cells after 1 day decreased significantly on the bared PMMA. It seems that because of the loose cell attachment on the bared PMMA, they detached from the surface during washing with 1X PBS. However, after washing, the viability of the cells was not significantly different (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

The live and dead cell viability assay. (a) The images taken after staining of the fibroblast-seeded bared PMMA (Control), TiO2-coated 1, and TiO2-coated 2 specimens after 1 day of cell culturing. (b) the diagram of the percentage of live cells in the different groups. Scale bar= 400μm. (* p < 0.05)

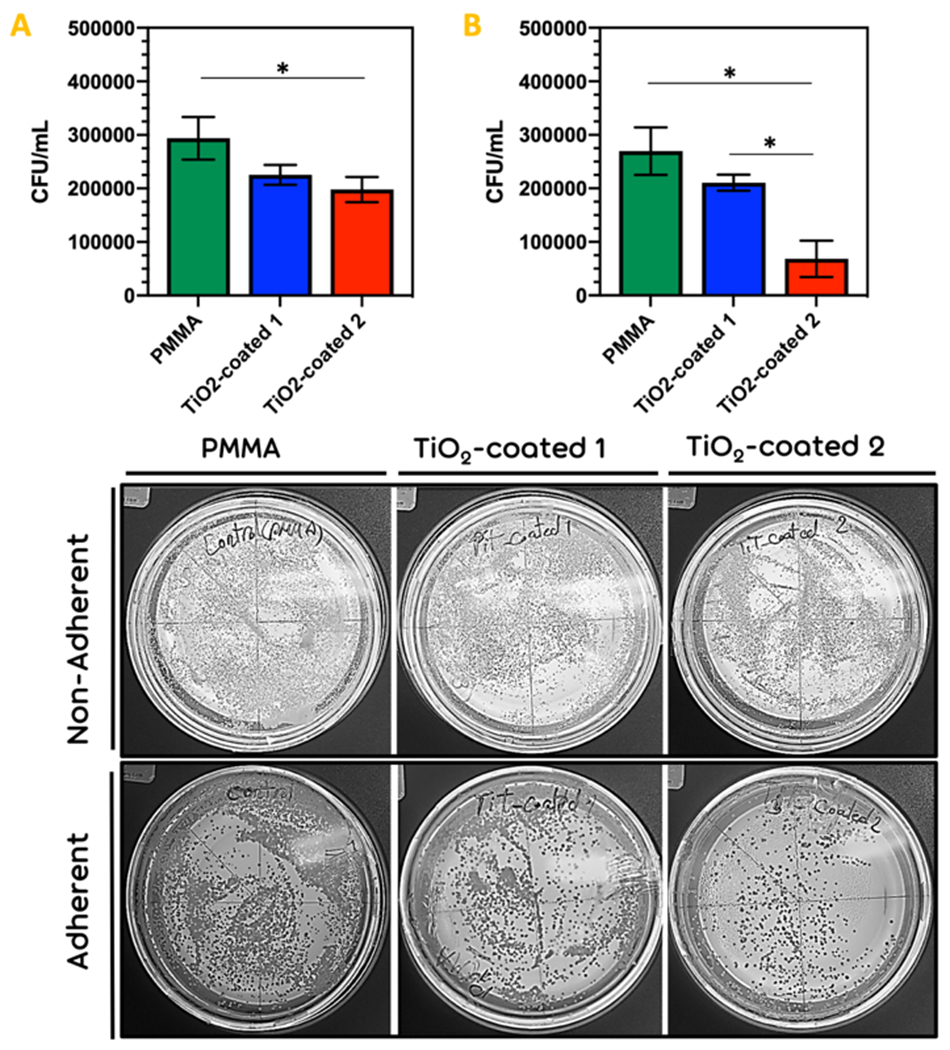

3.5. Antibacterial activity

In this research, antimicrobial activity was observed with the TiO2-coated PMMA surface in comparison with PMMA as the control group. A significant reduce (p < 0.05) in the number of viable attached cells of C. albicans was declared with the TiO2-coated 2 specimens compared to the PMMA control group (Fig. 8a). Also, a statistical reduction in the viable attached biofilm cells of C. albicans) was observed between PMMA and TiO2-coated 1 (p < 0.05) and TiO2-coated 2 (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8b).

Figure 8.

The (a) adherence and (b) non-adherence (biofilm formation) of C. albicans on group PMMA and group TiO2-PMMA. (* p < 0.05)

The high super-hydrophilicity of TiO2-coated PMMA samples (TiO2-coated 1 and TiO2-coated 2) may prompt less adherence of C. albicans for presenting the hydrophobic proteins in the C. albicans cell wall.29 It is worth mentioning that the improved hydrophilicity of the surface of the TiO2-coated specimens decreases the initial attachment of C. albicans. Also, TiO2 coating could give a smooth, low porous surface and unrivaled wear resistance, which may additionally decrease the diffusion of pathogens into the acrylic resin, adherence of biofilm, and colonization of microorganisms on PMMA.

4. Conclusions

In summary, contact angle results ascertained that the hydrophilicity of PMMA enhanced after TiO2 coatings (contact angle decreased after TiO2 coatings). The roughness analysis demonstrated that the roughness of the samples coated with TiO2 through procedure 2 is significantly more than TiO2-coated 1 and PMMA samples. DAPI staining revealed that the total number of the cells reduced gradually on the bared PMMA and TiO2-coated 1. The antimicrobial activity test revealed a significant decrease in the number of viable attached cells of C. albicans with the TiO2-coated 2 specimens compared to the PMMA control group. Also, a statistical reduction in the viable attached biofilm cells of C. albicans was confirmed between PMMA and TiO2-coated 1 and TiO2-coated 2. The hydrophilicity of TiO2-coated PMMA samples could prompt less adherence of C. albicans for presenting the hydrophobic proteins in the C. albicans cell wall. Also, TiO2 coating could give a smooth, low porous surface and unrivaled wear resistance, which may reduce the diffusion of pathogens into the acrylic resin, adherence of biofilm, and colonization of microorganisms on PMMA. Lastly, the obtained experimental results denoted that the procedure of TiO2 coating on PMMA developed in this research can be a promising method to improve a durable cell attachment to PMMA and resulted in a stable antifungal coating.

Acknowledgment

Part of the research reported in this paper was supported by National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number R15DE027533, 3R15DE027533-01A1W1 and 1R56 DE029191-01A1.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Zivic F, Babic M, Grujovic N, et al. Effect of vacuum-treatment on deformation properties of PMMA bone cement. Journal of the Mechanical behavior of Biomedical Materials 2012; 5: 129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knorz MC, Lang A, Hsia T-C, et al. Comparison of the optical and visual quality of poly (methyl methacrylate) and silicone intraocular lenses. Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery 1993; 19: 766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dohlman CH, Schneider HA and MGJAjoo Doane. Prosthokeratoplasty. 1974; 77: 694–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Socol G, Macovei A, Miroiu F, et al. Hydroxyapatite thin films synthesized by pulsed laser deposition and magnetron sputtering on PMMA substrates for medical applications. Materials Science and Engineering: B 2010; 169: 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goodger N, Wang J, Smagalski G, et al. Methylmethacrylate as a space maintainer in mandibular reconstruction. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery 2005; 63: 1048–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lye KW, Tideman H, Wolke JC, et al. Biocompatibility and bone formation with porous modified PMMA in normal and irradiated mandibular tissue. Clinical oral implants research 2013; 24: 100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren X, Feng Y, Guo J, et al. Surface modification and endothelialization of biomaterials as potential scaffolds for vascular tissue engineering applications. Chemical Society Reviews 2015; 44: 5680–5742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshijima Y, Murakami K, Kayama S, et al. Effect of substrate surface hydrophobicity on the adherence of yeast and hyphal Candida. Mycoses 2010; 53: 221–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujimoto K, Tadokoro H, Ueda Y, et al. Polyurethane surface modification by graft polymerization of acrylamide for reduced protein adsorption and platelet adhesion. Biomaterials 1993; 14: 442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ament JD, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Dohlman CH, et al. The Boston Keratoprosthesis: comparing corneal epithelial cell compatibility with titanium and PMMA. 2009; 28: 808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akiba N, Hayakawa I, Keh E-S, et al. Antifungal effects of a tissue conditioner coating agent with TiO2 photocatalyst. Journal of medical and dental sciences 2005; 52: 223–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cavalheiro A, Bruno J, Saeki M, et al. Effect of scandium on the structural and photocatalytic properties of titanium dioxide thin films. Journal of materials science 2008; 43: 602–608. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prakash J, Sun S, Swart HC, et al. Noble metals-TiO2 nanocomposites: from fundamental mechanisms to photocatalysis, surface enhanced Raman scattering and antibacterial applications. Applied Materials Today 2018; 11: 82–135. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang X, Lv B, Wang Y, et al. Bactericidal mechanisms and effector targets of TiO2 and Ag-TiO2 against Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of medical microbiology 2017; 66: 440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelizzetti E and Minero C. Mechanism of the photo-oxidative degradation of organic pollutants over TiO2 particles. Electrochimica acta 1993; 38: 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang R, Hashimoto K, Fujishima A, et al. Light-induced amphiphilic surfaces. Nature 1997; 388: 431–432. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujishima A and Honda K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. nature 1972; 238: 37–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tomaszewski H, Poelman H, Depla D, et al. TiO2 films prepared by DC magnetron sputtering from ceramic targets. Vacuum 2002; 68: 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang T-S, Shiu C-B and Wong M-S. Structure and hydrophilicity of titanium oxide films prepared by electron beam evaporation. Surface Science 2004; 548: 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borrero-López O, Hoffman M, Bendavid A, et al. Mechanical properties and scratch resistance of filtered-arc-deposited titanium oxide thin films on glass. Thin Solid Films 2011; 519: 7925–7931. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu T, Wen C, Lu J, et al. Sol-gel derived TiO2 coating on plasma nitrided 316L stainless steel. Vacuum 2012; 86: 1402–1407. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nemati A, Saghafi M, Khamseh S, et al. Magnetron-sputtered TixNy thin films applied on titanium-based alloys for biomedical applications: Composition-microstructure-property relationships. Surface and Coatings Technology 2018; 349: 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marra J, Paleari AG, Rodriguez LS, et al. Effect of an acrylic resin combined with an antimicrobial polymer on biofilm formation. Journal of Applied Oral Science 2012; 20: 643–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su W, Wang S, Wang X, et al. Plasma pre-treatment and TiO2 coating of PMMA for the improvement of antibacterial properties. Surface and Coatings Technology 2010; 205: 465–469. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alrahlah A, Fouad H, Hashem M, et al. Titanium Oxide (TiO2)/Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) Denture Base Nanocomposites: Mechanical, Viscoelastic and Antibacterial Behavior. Materials 2018; 11: 1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chatterjee A Properties improvement of PMMA using nano TiO2. Journal of applied polymer science 2010; 118: 2890–2897. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu W, Liu S and Wang L. Surface modification of biomedical titanium alloy: micromorphology, microstructure evolution and biomedical applications. Coatings 2019; 9: 249. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bose S, Robertson SF and Bandyopadhyay A. Surface modification of biomaterials and biomedical devices using additive manufacturing. Acta biomaterialia 2018; 66: 6–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuoka J, Wu G, Glee PM, et al. Inhibition of Candida albicans attachment to extracellular matrix by antibodies which recognize hydrophobic cell wall proteins. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 1999; 24: 421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]