SUMMARY

A chemically revertible bioconjugation strategy featuring a new bioorthogonal dissociative reaction employing enamine N-oxides is described. The reaction is rapid, complete, directional, traceless, and displays a broad substrate scope. Reaction rates for cleavage of fluorophores from proteins are on the order of 82 M−1s−1, and the reaction is relatively insensitive to common aqueous buffers and pHs between 4 and 10. Diboron reagents with bidentate and tridentate ligands also effectively reduce the enamine N-oxide to induce dissociation and compound release. This reaction can be paired with the corresponding bioorthogonal hydroamination reaction to afford an integrated system of bioorthogonal click and release via an enamine N-oxide linchpin with a minimal footprint. The tandem associative and dissociative reactions are useful for the transient attachment of proteins and small molecules with access to a discrete, isolable intermediate. We demonstrate the effectiveness of this revertible transformation on cells using chemically cleavable antibody-drug conjugates.

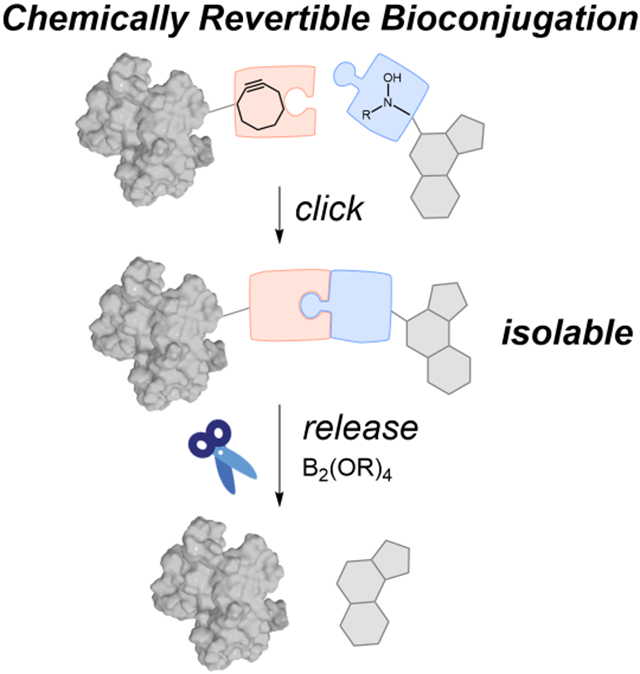

Graphical Abstract

eTOC Blurb

A paired set of associative and dissociative bioorthogonal transformations that directly interface with one another has been developed. A bioorthogonal hydroamination reaction is employed to conjugate a small molecule to a protein. This bioconjugate, linked via an enamine N-oxide linker, can be cleaved by diboron reagents to reverse the bioconjugation event in a rapid, complete, directional, and traceless manner. We have applied this revertible conjugation strategy to the attachment and release of drug from antibody-drug conjugates.

INTRODUCTION

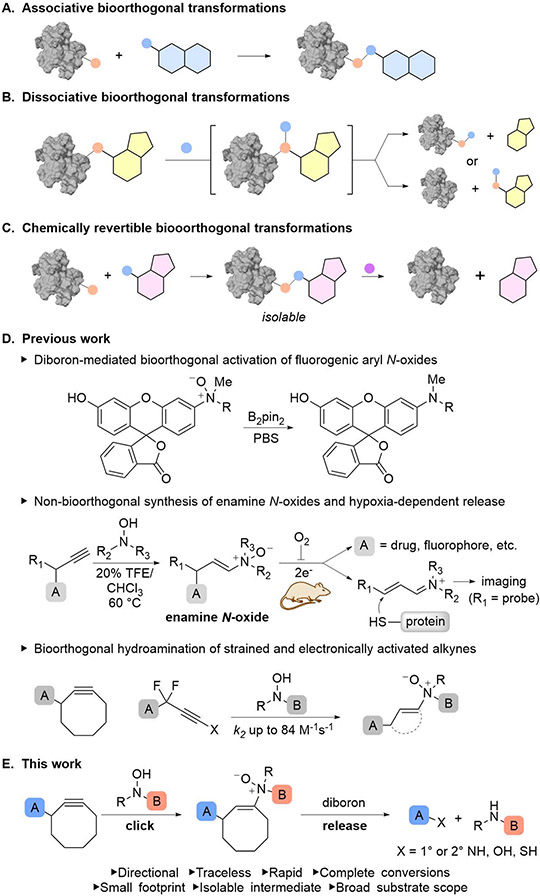

Bioorthogonal chemistry offers a powerful mechanism for chemically interfacing with biomolecules.1-3 For much of the past two and a half decades, a primary focus of this field has been the development of associative transformations highlighted by bioorthogonal ligation or “click” reactions4 facilitating the attachment of probes, drugs, affinity handles to proteins, sugars, lipids, and other primary and secondary metabolites (Figure 1A).5-7 These reactions have enabled the exploration of natural biological processes and the assembly of biologics for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. The impact of these highly chemoselective transformations extends beyond complex biological systems to highly constrained chemical environments in materials science and organic synthesis.8,9 Bioorthogonal dissociative reactions have been slower to develop, but their impact has been no less significant (Figure 1B).10-12 Underpinning transformational technologies such as Illumina sequencing,13 these reactions have also been used for cellular protein activation/inactivation10-12,14,15 and in the development of therapeutics.16-18

Figure 1.

Bioorthogonal chemistry. (A) Associative bioorthogonal transformations. (B) Dissociative bioorthogonal transformations. (C) Chemically revertible bioconjugation. (D) Previous work. (E) Rapid and complete sequential bioorthogonal hydroamination and traceless release of biomolecules via enamine N-oxides.

Recent studies have described extraordinary advances in the rapidly expanding field of dissociative bioorthogonal chemistry.10,19 Following the pioneering work of Meggers and co-worker in 2006 describing the ruthenium-mediated deallylation of allylcarbamates in cells,20 an eclectic mix of biologically compatible noble metal-mediated deallyl-, propargyl-, allenyl-, and benzylation processes has been reported.21,22 Combined with ring closing metathesis and copper-mediated oxidative cleavage methods, the ability to remove protecting groups on proteins or prodrugs has enabled the field to place diverse biological processes under chemical control.10-12,14,15,23 In 2008, Robillard and co-workers ushered in a new period of active bioorthogonal reaction development with the introduction of click-to-release strategies. First with the Staudinger reduction,24 and later with the tetrazine ligation,25 they demonstrated that bond formation can be relayed into bond cleavage by adaptation of classic bioorthogonal ligation reactions.26,27 Driven by its reactivity and versatility, tetrazine has since been implemented in numerous approaches as either activator or activated component25,28 alongside geometrically16,17,25,28-32 or electronically activated alkenes,33,34 alkynes,35 or isonitriles.36 Notably, the tetrazine-trans-cyclooctene (TCO) inverse electron demand Diels–Alder (IEDDA) reaction has proven indispensable as a drug release mechanism in therapeutic modalities ranging from antibody-drug conjugates16,17,25,28 to hydrogel-based prodrug activation,18 the latter of which is being evaluated in clinical trials.

Despite the success of existing technologies, continued chemical and functional development are essential. Bioorthogonal cleavage reactions that feature rapid, complete, directional, and traceless release of payloads with broad substrate scope, although achievable in part, are not yet wholly attainable. Improving the stability and accessibility of reagents are also goals worthy of continued pursuit.28,37 Even for the tetrazine-TCO reaction, which is at the vanguard of these cleavage transformations, investigations by Robillard and Weissleder have detailed the significant tradeoffs that exist between release rate and conversion.28,29,32 These twin challenges can be negotiated to remarkable effect using C2-symmetric TCOs as Carlson and Mikula elegantly demonstrated;31 however, these gains come at the cost of directionality. For applications valuing not just the dissociation event but the identity of the dissociated components, an adequate solution does not yet exist.

Notwithstanding recent developments in cyclization-based bioorthogonal release methods,35 Click-to-release reactions comprise heterolytic bond cleavage processes featuring 1,2-, 1,4-, and 1,6-elimination of caged nucleofuges from aminals,13 enamines16,17,25,28,29,31,32,36/enolsilanes,15 and aminobenzyl constructs,38 respectively, with enamines proving popular for these transformations. Most applications access these enamines via tautomerization of the corresponding imine. While imine formation is rapidly achieved by click reaction in click-to-release applications, issues of poor regiocontrol, slow tautomerization rates, undesired intramolecular cyclization, and sensitivity to local or environmental pH in the subsequent enamine formation step have proven challenging.28,29,32 We were thus motivated to find a means of generating an enamine directly.

Furthermore, as we explored the development of new bioorthogonal reactions, we wondered whether a set of reactions could be developed in a way that they could be interwoven to achieve a complex operation. In the broad context of organic chemistry, chemical synthesis involves a carefully choreographed sequence of bond forming and bond breaking events that enable chemists to design complexity and function into molecules. Short sequences of these events frequently used in tandem form compound operations that add to the sophistication of our synthetic lexicon. For instance, use of directing group chemistry is an operational unit that involves the traceless attachment and detachment of a prosthetic group operationally flanking a chemoselective transformation. In the more nascent subfield of bioorthogonal chemistry, transformations have largely developed as a collection of independent, stand-alone transformations with specific functions of ligation or cleavage. Building the sophistication of these fundamental operations within a larger strategic framework of bioorthogonal chemical synthesis is our goal (Figure 1C).

We previously reported that diboron reagents react rapidly and bioorthogonally with tertiary arylamine N-oxides;39 that introduction of unsaturation on amine N-oxides produces an enamine N-oxide motif capable of converting a reductive chemical stimulus into an immolative event;40 and that enamine N-oxides can be constructed bioorthogonally by hydroamination of strained41 or push-pull-activated linear alkynes with N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines (Figure 1D).42 Importantly, our application of these compounds to the synthesis of hypoxia prodrugs and imaging agents demonstrated that while these molecules undergo selective reduction and activation by hemeproteins under oxygen-deficient conditions both in vitro and in vivo, the enamine N-oxide motif is otherwise stable and suitable for use as a chemically cleavable unit in a broader biological context.40 Taken together, these findings furnish the essential components for the sequential arrangement of two discrete and functionally opposing bioorthogonal transformations of click and release (Figure 1E).

Herein, we investigate the scope of the click and release reactions mediated by enamine N-oxides. We elucidate the structure-activity relationships for the hydroxylamine, diboron, and enamine N-oxide components, characterize the kinetics of linker cleavage, evaluate substrate scope, explore the stability of reaction components both experimentally and computationally, and deploy this tool in an application involving chemically cleavable antibody-drug conjugates. We will demonstrate that the cleavage reaction is rapid, quantitative, directional, traceless, and has broad substrate scope. Its integration with our bioorthogonal hydroamination reaction, which is likewise rapid and regioselective, forms a self-contained operational unit with a small footprint capable of formation and deconstruction of a discrete protein-small molecule adduct.

RESULTS

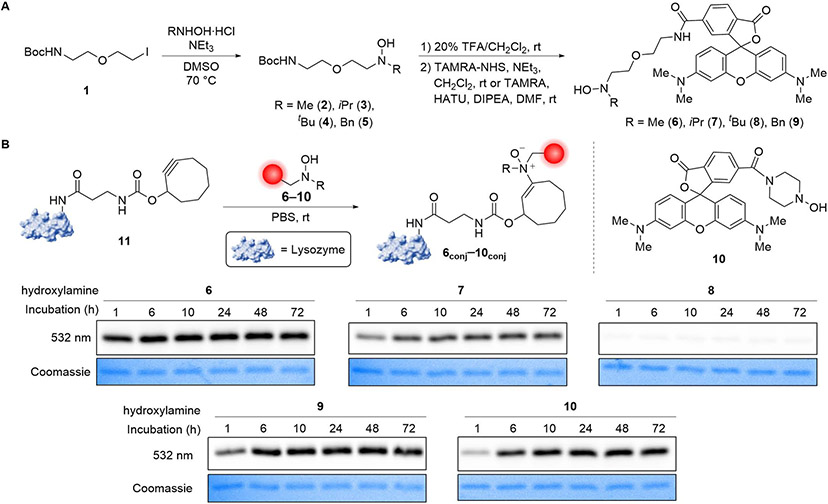

Integration of two independent bioorthogonal ligation and cleavage reactions into a single unified transformation featuring chemical revertibility requires the coordinated optimization of each. We initiated our studies by investigating the substrate scope of the lead hydroamination reaction43 with the expectation that sterics might play a major role in balancing the biological stability of the resulting enamine N-oxide and the reaction rates of both click and release. A series of N,N-dialkylhydroxylamine probes were thus synthesized by nucleophilic displacement of alkyl iodide 1 with N-methyl, benzyl, isopropyl, and tert-butyl hydroxylamine hydrochloride and triethylamine in DMSO at 70 °C. Trifluoroacetic acid-mediated Boc deprotection and HATU coupling of 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) or coupling of TAMRA-NHS ester to the resulting amine produced TAMRA-hydroxylamine conjugates 6–9 (Figure 2A). A cyclic N-hydroxypiperazinyl-TAMRA conjugate 10 was also prepared. Separately, lysozyme-cyclooctyne conjugate (Lys-COT) 11 was produced by acylation of lysine residues with cyclooctyne-modified 3-aminopropanoic acid via the corresponding N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester.

Figure 2.

Evaluating the impact of hydroxylamine substituents on the bioorthogonal retro-Cope elimination reaction. (A) Synthetic route for accessing TAMRA-hydroxylamine conjugates 6–9. (B) Lysozyme-cyclooctyne conjugate 11 (10 μM) was incubated with TAMRA-hydroxylamine conjugates 6conj–10conj (200 μM) in PBS at room temperature for 1–72 h then analyzed by in-gel fluorescence. Gels for all substrates were imaged together on the fluorescence imager. Coomassie stain serves as loading control. See also Figure S1.

The relative rates of hydroamination between TAMRA-hydroxylamines 6–10 (200 μM) and Lys-COT 11 (10 μM) were evaluated by monitoring the extent of lysozyme labeling over 1–72 h in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature by in-gel fluorescence (Figure 2B and S1). N-Methylhydroxylamine 6 displayed the fastest reaction rate, nearly reaching complete conversion in 1 h. The benzyl and piperazinyl variants 9 and 10 demonstrated a marginally slower, yet still rapid, retro-Cope elimination reaction, reaching completion within 6 and 10 h, respectively. For all three of these substrates, the labeling proved durable over 72 h, indicating the general stability of the resulting enamine N-oxides. Surprisingly, we found that the more sterically encumbered hydroxylamines 7 and 8 featuring α-branching exhibited poor labeling.

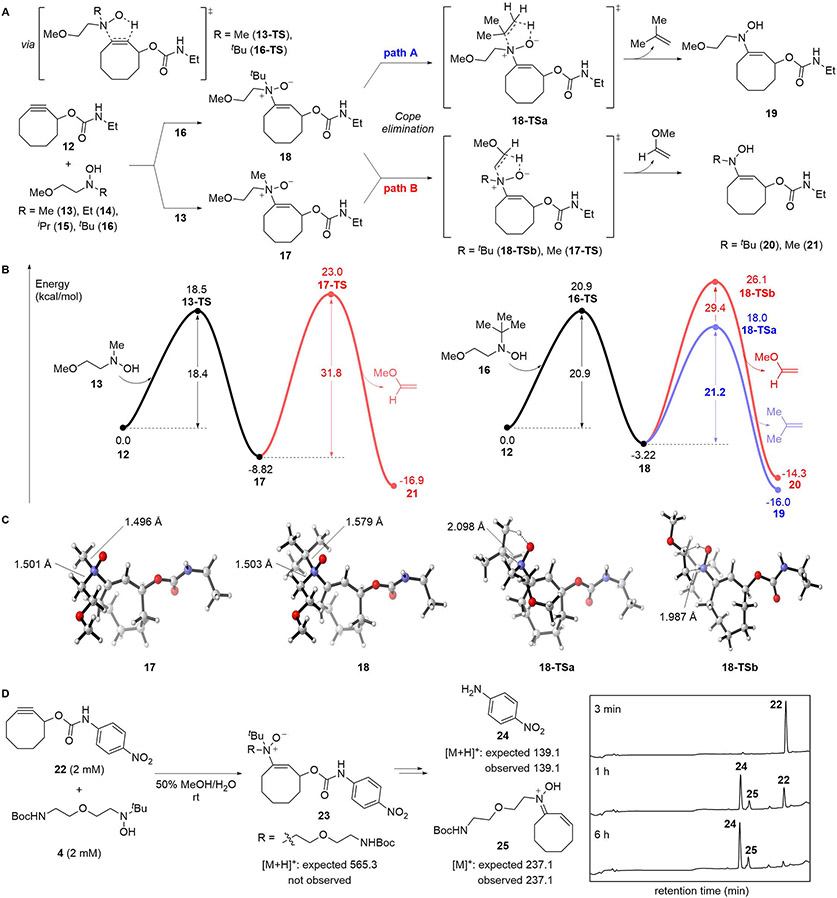

To determine whether the poor labeling were the result of retarded hydroamination or enamine N-oxide product instability, we explored these processes computationally. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations performed at the M06-2X/6-31G(d,p) level of theory yielded activation free energies of 17.7–20.9 kcal/mol for the initial ligation step between N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines 13–16 and cyclooctyne ethylcarbamate 12 (Figures 3A, 3B, S18). Increasing steric load on the hydroxylamine reagent was met with just a modest increase in activation barrier across the range of substrates examined (R = Me, Et, iPr, tBu), indicating that even the most sterically demanding tert-butylhydroxylamine 16 should undergo rapid hydroamination at room temperature.

Figure 3.

Computational studies investigating the formation and degradation of enamine N-oxide structures. Geometries were optimized at the M06-2X/6-31G(d,p) level of theory and single point energies were computed at the M06-2X/6-311G(2d,p) level of theory. (A) Computational reaction model exploring the effect of steric hindrance on the hydroamination and Cope elimination reactions. (B) Calculated Gibbs free energies and free energies of activation. Reaction coordinates for Paths A and B are in blue and red, respectively. (C) Three-dimensional structures of 17 and 18 and Path A and B transition state structures 18-TSa and 18-TSb. (D) Reaction between cyclooctyne 22 (2 mM) and hydroxylamine 4 (2 mM) was monitored by A220 absorbance on LCMS. See also Figures S5 and S18.

In contrast, hydroxylamine sterics appeared to hold dramatically more sway over product stability. We evaluated two different degradation pathways, one involving loss of the variable alkyl substituent via Cope elimination (Path A), the other involving loss of the methoxyethylene mock linker (Path B). In each case where Path B was evaluated, it appeared inoperative at room temperature, size of the alkyl substituent notwithstanding. The activation free energy (ΔG†) for this pathway proved consistently high across substrates, 31.8 kcal/mol for the N-methyl substrate to 29.4 kcal/mol for the tert-butyl (Figure 3B). In contrast, Path A proved more sensitive to steric environment, featuring ΔG† as low as 21.2 kcal/mol for the most sterically hindered tert-butyl substrate 18. With an activation energy comparable to that for hydroamination, the tert-butyl substrate is likely to undergo rapid Cope elimination even at room temperature.

Consistent with the calculated Gibbs free energies, the computed ground state structure of the N-tert-butyl enamine N-oxide 18 exhibited a significantly elongated C─N bond between the tert-butyl substituent and the N-oxide. The 1.579 Å bond length is >5% longer than the C─N bond involving the methoxyethylene appendage or either of the two N-alkyl substituents in the less sterically hindered N-methyl enamine N-oxide 17. The long C·N distance of the dissolving C─N bond in Path A is particularly notable when juxtaposed against the analogous C··N distance for Path B (Figure 3C). In aggregate, calculations suggest that while Cope elimination is not problematic for sterically unencumbered unbranched linkers, increasing the steric environment around the enamine N-oxide significantly facilitates Cope elimination favoring loss of the larger substituent provided that a β-hydrogen is available and accessible.

We wished to validate these computational observations experimentally, so we monitored two analogous reactions by LCMS (Figures 3D, S5). Hydroxylamines 3 and 4 (2 mM) were introduced to p-nitroaniline cyclooctyne carbamate 2241 (2 mM) in 50% MeOH/H2O, and in each case, the cyclooctyne was fully and rapidly consumed over the course of 6 h. Specifically in the case of N-isopropylhydroxylamine 3, LCMS analysis indicated the fast formation, plateauing, and persistence of the desired enamine N-oxide along with the released p-nitroaniline and the corresponding Cope elimination byproduct over that time period. Distinctly, in the case of tert-butylhydroxylamine 4, enamine N-oxide product 23 could not be detected by LCMS as consumption of starting material was accompanied by immediate and concomitant formation of p-nitroaniline (24) and corresponding Cope elimination byproduct 25. Consistent with our computational studies, Path A-based byproducts were exclusively observed for reactions involving both isopropyl and tert-butyl compounds.

The instability of enamine N-oxides 23 and S15 was unexpected given our previous observations that the α- and α,α'-branched N,N-ethylisopropyl and N,N-dicyclohexylhydroxylamines produce readily isolable anti-Markovnikov hydroamination products from terminal alkynes;40 however, it was consistent with our prior report that the hydroamination of dibenzoazacyclooctyne (DIBAC) by N,N-diethylhydroxylamine generates an unstable adduct that evades isolation.41 In contrast to the hydroamination of terminal alkynes, the bioorthogonal strain-promoted variant introduces geminal substitution on the resulting olefin with attendant A(1, 2)-like strain. Consequently, cyclooctyne hydroamination appears to be much more sensitive to steric crowding around the N-oxide moiety, and degradation is significantly enhanced by alkyl branching and/or cyclooctyne arylation.

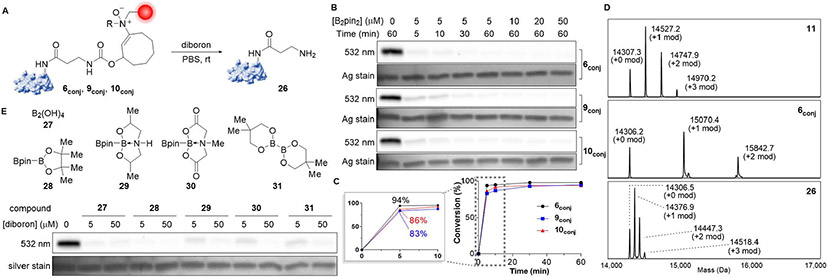

Based on these insights, we proceeded to evaluate the influence of substituent effects on bioorthogonal release with reagents featuring methyl, benzyl, and piperazinyl substituents, which for lack or inaccessibility of β-hydrogens proved stable (Figure S2). Lysozyme-TAMRA conjugates 6conj, 9conj, and 10conj (480 nM) were each treated with a range of bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2pin2) concentrations (5–50 μM) in PBS for 1 h (Figure 4A).44-46 Complete reductive removal was observed for each substrate and concentration as indicated by the complete loss of signal in the in-gel fluorescence experiment. Reaction kinetics were then monitored by quenching the reaction at various time points with excess trimethylamine N-oxide. Impressively, the efficacy of reductive cleavage was fairly general and broadly tolerant of structure (Figure 4B). Employing 5 μM diboron, all reactions displayed >80% completion by 5 min and were observably complete by 30 min with methyl-substituted enamine N-oxide 6conj cleaving the fastest. It displayed 94% cleavage by the first time point (Figures 4C, S4). The quantitative nature of both click and release operations were then characterized by intact protein mass spectrometry. Lysozyme-cyclooctyne conjugate 11, possessing 0–3 cyclooctyne linker modifications, was treated with 200 μM hydroxylamine 6, 9, or 10 then cleaved with 25 μM B2pin2 for 30 min. ESI-MS of each transformation showed clean and complete bioorthogonal hydroamination and cleavage (Figures 4D, S6).

Figure 4.

Diboron-mediated enamine N-oxide reduction and payload release. (A) Enamine N-oxide-bearing lysozyme-TAMRA conjugates 6conj, 9conj, and 10conj were treated with diboron reagents in PBS at room temperature to induce the release of the fluorophore. (B) Concentration-dependent cleavage of lysozyme-TAMRA conjugates 6conj, 9conj, and 10conj (480 nM) at room temperature over 1 h with B2pin2 (5–50 μM) was analyzed together with time-dependent cleavage over 5–60 min with 5 μM B2pin2 by in-gel fluorescence. Silver stain is provided as loading control. (C) Quantification of the fluorescence in the bands from the time-dependent diboron-induced cleavage experiment. (D) Complete conjugation and removal of TAMRA from lysozyme was observed using intact mass spectrometry. Lys-COT 11 (10 μM) featuring 0–3 modifications was combined with hydroxylamine 6 (200 μM) in PBS at room temperature for 6 h. The adduct 6conj (R=Me) was cleaved with B2pin2 (25 μM) for 30 min at room temperature. (E) Structurally diverse diboron reagents 27–31 (5 or 50 μM) were incubated with N-methyl lysozyme-TAMRA conjugate 6conj (240 nM) for 60 min at room temperature then analyzed for loss of the fluorophore by in-gel fluorescence analysis. See also Figures S3, S4, and S6.

We next explored the impact of boron ligands on the dissociation reaction. Ligands play a significant role in determining the physicochemical properties of boron reagents and is expected to influence the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics properties of these molecules in in vivo settings. We were particularly interested to see whether the reductive cleavage reaction would tolerate variations in the boron ligand and whether preformation of coordinately saturated electron-rich boron complexes would facilitate N-oxide reduction. We evaluated five different diboron reagents including unliganded tetrahydroxydiboron, diol liganded bis(pinacolato)diboron, and two mixed ligand diboron structures featuring bis(2-hydroxypropyl)amine47 or methyliminodiacetic acid48 (Figure 4E and S3). Lysozyme-TAMRA conjugate 6conj was treated with 5 or 50 μM of each diboron reagent in PBS and analyzed by in-gel fluorescence after 1 h. Excitingly, we discovered that the diboron-induced cleavage of enamine N-oxides was relatively agnostic to the ligand, tolerating even the most sterically demanding bidentate and tridentate ligands. Complete cleavage was observed for all reagents at 50 μM concentrations. Tetrahydroxydiboron and bis(pinacolato)diboron stood out amongst the five, displaying the greatest reactivities and allowing the reaction to reach completion by 1 h even at 5 μM concentrations. While just perceptibly incomplete, the other three reactions were still rapid, exhibiting >95% completion at the same concentration in 1 h.

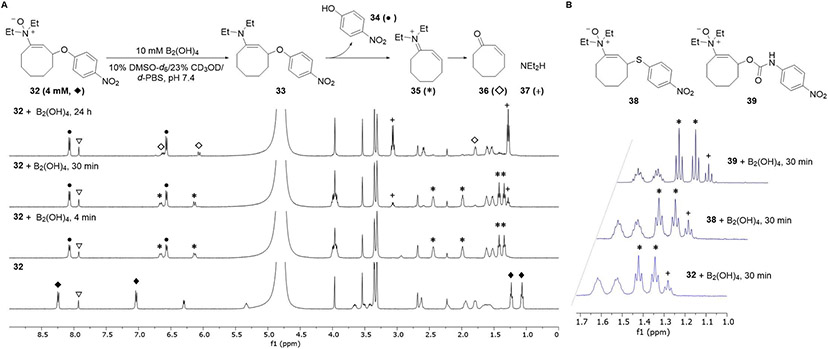

Diboron reagents and enamine N-oxide structures in hand, we sought to characterize the reaction kinetics and explore the substrate scope for the cleavage reaction. We first obtained a series of chromogenic probes 32, 38, and 39 featuring a representative series of nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur-bearing leaving groups. Each probe was synthesized from cyclooct-2-ynol either by Mitsunobu reaction or carbamoylation with the corresponding p-nitro(thio)phenol or p-nitrophenyl isocyanate followed by hydroamination with N,N-diethylhydroxylamine. We first verified the formation of the intended products by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figures 5A, S7, S8). We found that when p-nitrophenyl ether 32 was treated with 10 mM B2(OH)4 in 10% DMSO-d6/23% CD3OD/d-PBS, pH 7.4, the first spectrum obtained at 4 min demonstrated both complete reduction of the N-oxide as well as quantitative formation of the released payload p-nitrophenol (34) together with the α,β-unsaturated iminium ion 35. Over the course of 24 h, iminium ion 35 hydrolyzed to cyclooctenone 36 and diethylamine 37. The other substrates reacted analogously with the same quantitative formation of iminium ion 35 at the initial time point (Figure 5B). Importantly, while we could not ascertain whether reduction or elimination were rate limiting under these conditions, the experiment placed an upper limit on the half-life of enamine 33 at a few minutes.

Figure 5. Characterization of the diboron-mediated reductive cleavage of enamine N-oxides.

(A) Progress of the reaction between 4 mM p-nitrophenol-derived enamine N-oxide 32 and 10 mM B2(OH)4 in a mixture of 10% DMSO-d6, 23% CD3OD, and 67% d-PBS (pH 7.4) was monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy over 24 h. Key peaks for each species are denoted as follows: 32 (♦), 34 (●), 35 (*), 36 (♢), and 37 (+). Caffeine (▽) was included as an internal standard.

(B) Analogous reactions using p-nitrophenyl thioether 38 and p-nitrophenylcarbamate 39 produced highly similar reaction profiles with the formation of identical intermediates after cleavage. A representative inset from the 1H NMR spectra of each reaction at 30 min is provided.

See also Figures S7 and S8.

The chromogenic probes we prepared were intended for stopped flow kinetics experiments using UV-vis spectroscopy; however, our NMR studies precluded the use of one of these compounds for this purpose. Specifically, carbamate 39 resulted in release of 4-nitrophenylcarbamic acid, which persisted as a discrete intermediate on a timescale longer than that for either reduction or release before undergoing decarboxylation. Since a change in UV absorbance is contingent on p-nitroaniline formation, we were unable to use this or analogous carbamate-based chromogenic or fluorogenic outputs as accurate proxies for product release. Instead, we turned to a fluorescence polarization assay. Fluorescence polarization measurements are directly responsive to the presence or absence of a direct interaction between protein and small molecule and are capable of reporting on a bond cleavage event with great fidelity. Furthermore, performing the cleavage reaction on proteins would provide an accurate representation of the reaction kinetics in a biological setting.

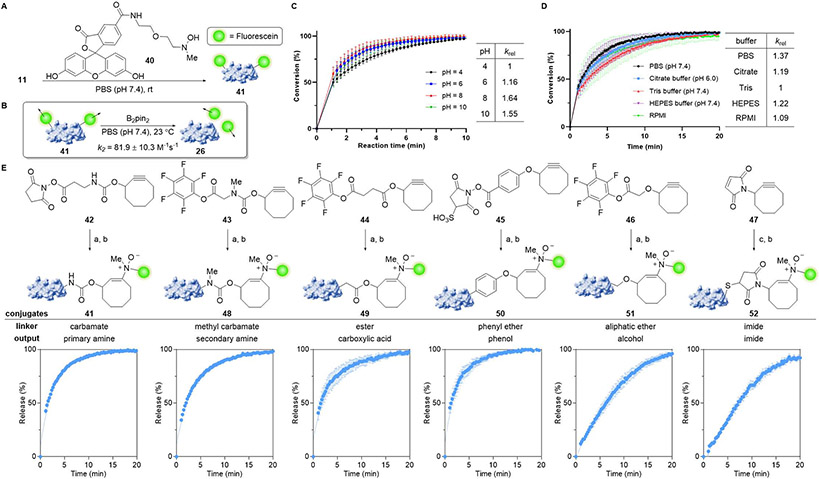

To this end, we synthesized hydroxylamine-linked fluorescein 40 and used it to functionalize lysozyme-cyclooctyne conjugate 11 by retro-Cope elimination (Figure 6A). 500 nM fluorescein-lysozyme conjugate 41 was then treated with excess B2pin2 (25–200 μM) in PBS, pH 7.4, at 23 °C, and we determined that the reaction rate is first order in diboron reagent at this concentration range. The second order rate constant for this reaction was found to be 81.9 M−1s−1 (Figure 6B). We next examined the kinetics of the reaction at various pH’s to determine whether N-oxide protonation under acidic conditions or diboronate formation under basic conditions would adversely impact reactivity. Fortunately, we found the reaction to be relatively insensitive to solvent pH in the examined range and the reaction to be only marginally faster at pH 10 than at pH 4 (Figure 6C). The diboron-mediated cleavage was also compatible with a full range of common aqueous buffers including PBS (pH 7.4), citrate buffer (pH 6.0), Tris buffer (pH 7.4), HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), and RPMI growth medium. Importantly, buffer content had minimal impact on reactivity, testifying to the generality of this method. Irrespective of the specific solvent conditions, all reactions were >99% complete within 5–20 min when 50 μM B2pin2 was employed (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Investigating the reaction scope and kinetics of payload release for the diboron-mediated cleavage of enamine N-oxides. (A) Lysozyme-fluorescein conjugate 41 was produced by hydroamination of Lys-COT 11 with fluorescein hydroxylamine 40 in PBS at 23 °C. (B) Kinetics of diboron-mediated enamine N-oxide cleavage was determined by fluorescence polarization under pseudo-first order conditions. Lysozyme-fluorescein conjugate 41 (500 nM) was treated with B2pin2 (25–200 μM) in PBS at 23 °C. (C) Influence of buffer pH on cleavage rates. Lysozyme-fluorescein conjugate 41 (500 nM) was reduced with B2pin2 (100 μM) in PBS, pH 4–10, and conversion was measured by fluorescence polarization. (D) Influence of buffer composition on cleavage rates.

Lysozyme-fluorescein conjugate 41 (500 nM) was reduced with B2pin2 (50 μM) in several buffers, and conversion was measured by fluorescence polarization. (E) Influence of leaving group composition on cleavage rates. Lysozyme-fluorescein conjugates 41, 48–52 featuring different functional groups as linkers were generated by lysine or cysteine functionalization followed by hydroamination with hydroxylamine 40. Lysozyme-fluorescein conjugates 41, 48–52 (500 nM) were reduced with B2pin2 (50 μM) in PBS, pH 7.4 at 23 °C. Conditions: (a) lysozyme, PBS, pH 7.4. (b) 40, PBS, pH 7.4. (c) lysozyme, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, PBS, pH 7.4, 1 h, rt, then 47, PBS, pH 7.4. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). See also Figures S9-S11.

Additionally, crude biological conditions did not perturb the reaction kinetics appreciably. Whether the reaction was performed in the presence of HEK293T cell lysate (1 mg/mL), human liver microsomes (1 mg/mL), or human serum (10% v/v) in PBS, the reduction of fluorescein-lysozyme conjugate 41 by B2pin2 was >90% complete within 5–20 min (Figure S10A). The diboron-mediated cleavage proceeded just as rapidly even in solutions of mouse heart, kidney, intestine, liver, or spleen tissue homogenates (1 mg/mL) in PBS (Figure S10B). Amidst the robust performance of these reactions in a broad range of crude biological media, we observed that the cleavage reactions were most impacted by both human and mouse liver tissues. While the precise origins of this perturbation could not be ascertained, we note that diboron reagents react rapidly with cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide and superoxide (Figure S17). Perhaps high levels of ROS could interfere with the diboron-mediated reaction in some cellular contexts. This reactivity notwithstanding, our results together with prior use of diboron49 and enamine N-oxide40 compounds in in vivo applications reflect favorably on the broad biological compatibility of this dissociative transformation.

To further demonstrate the versatility of the diboron-mediated dissociative transformation, we evaluated the bond cleavage kinetics for enamine N-oxide conjugates linked by different functional groups. We started with the synthesis of cyclooctynes 42–47 featuring primary and secondary amine carbamates, an ester, phenyl and alkyl ethers, and an imide as leaving groups (Figure 6E and S9). With the exception of imide 47,50 which was conjugated to a cysteine residue by Michael addition, each of these compounds were attached to lysine residues on lysozyme via activated (sulfo)NHS or pentafluorophenyl esters. Fluorescein hydroxylamine 40 was subsequently ligated onto these cyclooctynes by hydroamination to generate enamine N-oxide-linked adducts, which were then reduced using 50 μM B2pin2 in PBS, pH 7.4. Progress of payload release was monitored by fluorescence polarization. Not surprisingly, the reaction profiles were nearly identical for substrates 41, 48–50. We had already determined above that N-oxide reduction is rate limiting for the primary amine carbamate 41 at these diboron concentrations; this is likely true of the other three substrates containing activated leaving groups. Gratifyingly, the reaction kinetics were rapid with each reaction achieving >90% product release within 10 min and full conversion being obtained by 20 min. In contrast, we observed that the less activated alkyl alcohol and imide leaving groups displayed a markedly different reaction profile reflective of their slower release rates and likely shift in the rate determining step. Nonetheless, despite the slower elimination rates, alkyl alcohols and imides also exhibited >96% and 92% product release within 20 min, respectively.

Finally, we corroborated the influence of diboron structure on the rate of enamine N-oxide reduction for diboron reagents 27–31 using the same fluorescence polarization-based kinetics assay (Figure S11). We also verified that the release reaction would work well on intracellular proteins in live cells with each of these reagents. HeLa cells transiently transfected with cytosolic GFP-HaloTag protein were treated with cyclooctyne-chloroalkane ligand S22, washed, then conjugated with TAMRA-hydroxylamine 6 by bioorthogonal hydroamination. Clear co-localization of GFP and TAMRA signals was observed. TAMRA labeling could be completely ablated by treating the cells with diboron reagents 27–31 (Figure S12).

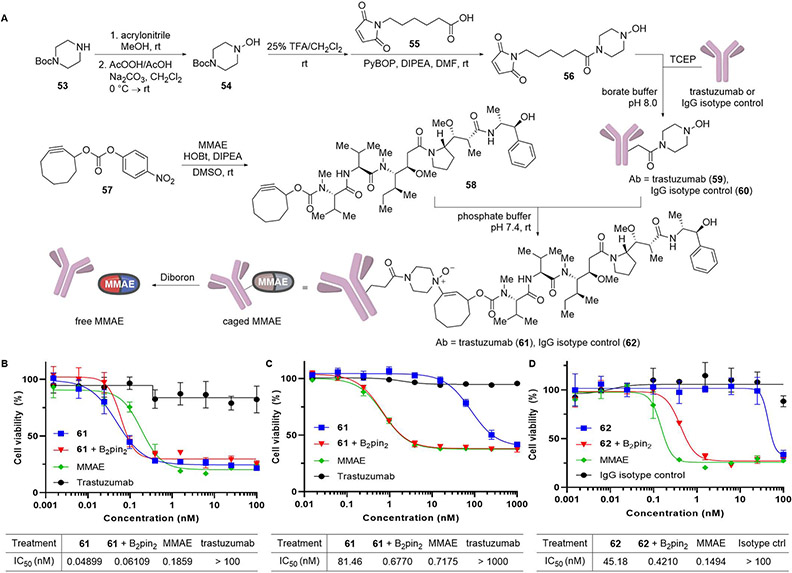

Having developed the independent components of click and release, we sought to integrate them in an application involving the ligation and cleavage of a small molecule to and from a protein. Antibody-drug conjugates presented the perfect platform as dissociative reactions provide a chemically induced mechanism of drug release independent of cellular catabolic processes. We highlight how both parts of our reactions can be used for forming and cleaving these conjugates. Our work commenced with the synthesis of hydroxylamine-bearing antibodies. 1-Hydroxypiperazine 54 was rapidly synthesized by alkylation of N-Boc-piperazine (53) with acrylonitrile in methanol followed by N-oxidation and Cope elimination of the resulting N-oxide. Trifluoroacetic acid-mediated Boc deprotection and PyBOP-mediated amide coupling with 6-maleimidohexanoic acid (55) produced maleimide 56, which could be appended to either trastuzumab or human IgG isotype control antibodies by conjugate addition of cysteine residues generated by TCEP-mediated reduction of the hinge disulfides on IgG. Separately, cyclooctyne-modified cytotoxin monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE-COT, 58) was obtained by carbamylation of MMAE with cyclooctynyl p-nitrophenyl carbonate 57. With each component in hand, the ligation of MMAE-COT onto either 1-hydroxypiperazine-modified trastuzumab 59 or IgG isotype control 60 was carried out by bioorthogonal hydroamination in PBS at room temperature to afford ADCs 61 and 62, respectively (Figure 7A and S13).

Figure 7.

Synthesis and cellular evaluation of chemically cleavable enamine N-oxide-linked antibody-drug conjugates. (A) Synthesis of ADCs 61 and 62. (B) Cell viability assay of trastuzumab-derived ADC 61 in the presence or absence of 50 μM B2pin2 on SK-BR-3 HER2+ breast cancer cells. (C) Cell viability assay of trastuzumab-derived ADC 61 in the presence or absence of 50 μM B2pin2 on MDA-MB-231 HER2− breast cancer cells. (D) Cell viability assay of IgG isotype control-derived ADC 62 in the presence or absence of 50 μM B2pin2 on SK-BR-3 HER2+ breast cancer cells. Error bars represent standard deviation (n = 3). See also Figures S13-S15.

After confirming the cellular compatibility of our diboron reagents (IC50 > 500 μM, Figures S14, S15) and verifying the stability of piperazinyl enamine N-oxide-linked IgG conjugates in both RPMI + 5% human serum (Table S1) and conditioned media from SK-BR-3 breast cancer cell lines (<3% release over 42 h, Table S2), we proceeded to evaluate the efficacy of our chemistry in inducing drug release from ADCs by measuring its impact on cell viability. SK-BR-3 cells were treated with 1.5 pM–100 nM trastuzumab-MMAE 61 in the presence or absence of 50 μM B2pin2, cultured for 72 h, and assayed using the CellTiter-Glo cell viability assay. Unsurprisingly, the IC50 of the ADC was insensitive to the presence or absence of diboron and recapitulated the IC50 of MMAE alone. This was expected as SK-BR-3 is a HER2-positive cell line and drug release can be induced through internalization and lysosomal degradation of the ADC. The IC50 of ADC 61 alone (0.04899 nM) was comparable to that of ADC with diboron (0.06109 nM). Each recapitulated the toxicity of MMAE alone (IC50 = 0.1859 nM). Unmodified trastuzumab was found to have little activity at these concentrations (Figure 7B).

In contrast, when the same experiment was performed on the triple negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 lacking HER2 amplification, a marked difference was observed in the cell viability curves after 96 h for trastuzumab-MMAE 61 alone (IC50 = 81.46 nM) or in combination with 50 μM diboron (IC50 = 0.6770 nM). Only when diboron was employed did the ADC reproduce the toxicity of MMAE (IC50 = 0.7175 nM) (Figure 7C). As further control, we replaced trastuzumab with a human IgG isotype control, employing ADC 62. Unable to undergo receptor-mediated internalization and drug release in the SK-BR-3 cell line, the ADC exhibited a 107-fold enhancement in cell toxicity when used in combination with the diboron reagent versus without. Importantly, the diboron-induced drug release mechanism exhibited comparable effects on cell viability as MMAE alone consistent with significant release of the drug (Figure 7D). This N-oxide-based drug delivery platform provides a convenient mechanism for loading drugs onto antibodies as well as an appealing alternative to existing methods for the fast and complete release of drug molecules from their carriers.

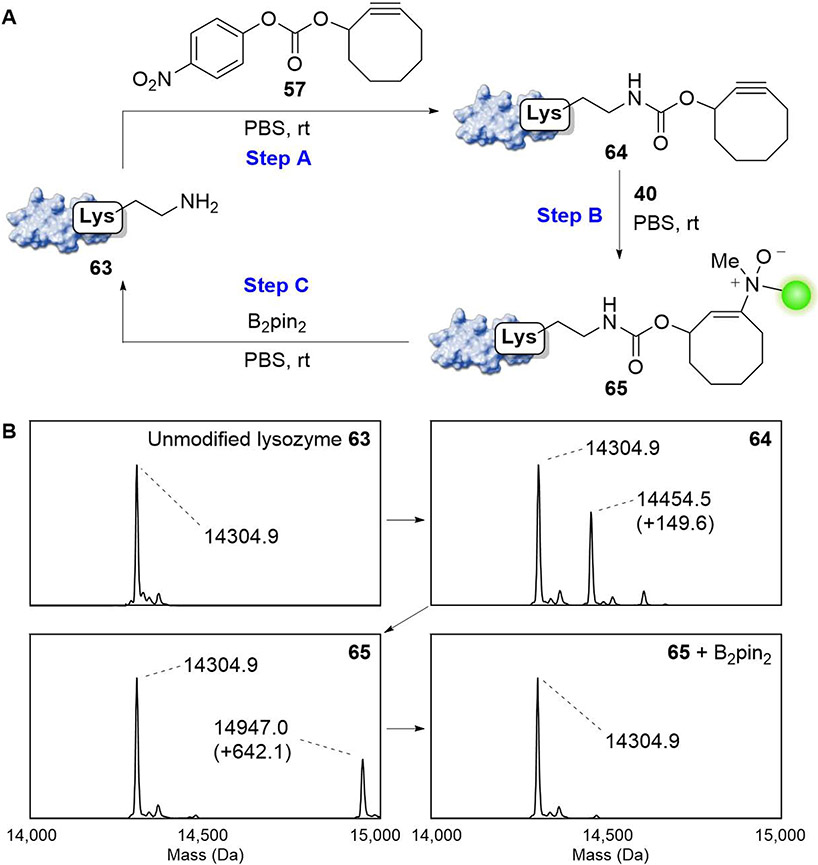

The chemically revertible bioconjugation reaction that we have described is both directional and traceless. In the antibody-drug conjugate application, we demonstrated the quantitative release of the small molecule MMAE. There, the drug was released in its native form without derivatization. When the traceless modification of a protein is desired instead, it is possible to easily reverse the polarity of the chemical handles to remove any residual modifications on the protein. We demonstrate this powerful feature through the functionalization and chemical reversion of lysozyme (Figure 8A and S16).

Figure 8.

Demonstration of traceless and revertible protein modification using enamine N-oxide chemistry. (A) Schematic illustration of sequential conjugation and removal of small molecules on lysozyme. Lysozyme (5 mg/mL) was incubated with cyclooctynyl p-nitrophenyl carbonate 57 (2.6 mM) in PBS for 1 h (Step A). The resulting conjugate 64 (0.60 mg/mL) was treated with fluorescein-hydroxylamine 40 (200 μM) for 6 h (Step B). This discrete adduct is tracelessly removed with B2pin2 (25 μM) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature (Step C). (B) Clean and complete click and release was observed by intact mass spectrometry. See also Figure S16.

Lysozyme was first modified with a cyclooctyne using cylooctynyl p-nitrophenylcarbonate 57 to afford the cyclooctyne-modified protein 64, which was suitable for bioconjugation. In this proof-of-principle experiment, we conjugated fluorescein via the corresponding hydroxylamine 40. Finally, both the fluorescein and cyclooctyne handle could be removed completely using 25 μM B2pin2 in PBS to restore the original lysine residue. The traceless sequence of chemical operations was verified by ESI-MS (Figure 8B). Although lysozyme was modified by reaction with carbonate 57 in this particular example, the described method of traceless click and release is agnostic to the method of cyclooctyne incorporation. We anticipate that when combined with existing methods of site-specific incorporation such as with unnatural amino acids,51 this bioorthogonal reaction sequence can potently enable the precise modification and manipulation of proteins.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we described the revertible chemical modification of proteins and small molecules using bioorthogonal transformations. We found that N,N-dialkylhydroxylamines without α-branching provide stably linked enamine N-oxides, which otherwise undergo Cope elimination and premature product release. Bioorthogonal hydroamination is rapid, complete, and regioselective, even affording a diastereospecific transformation when N-hydroxypiperazine linkers are employed. We paired this associative transformation with an opposing dissociative transformation in which reductive cleavage of enamine N-oxides was accomplished using diboron reagents. We found diboron reagents liganded with either bidentate or tridentate ligands to be similarly effective in achieving rapid reduction, paving the way for further optimization of ligands along physicochemical, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics parameters in future in vitro and in vivo studies. Kinetics evaluation of diboron-mediated product release revealed the N-oxide reduction step to be rate limiting with a second-order rate constant in the range of 82 M−1s−1 when carbamate substrates are employed alongside diboron reagents at concentrations of 200 μM or lower. The reaction is insensitive to solvent pHs between 4 and 10 and common aqueous buffers, and the cleavage reaction displays broad substrate scope, enabling carbamates (of primary and secondary amines), esters, ethers (aryl and alkyl), and imides to be rapidly and completely released on the timescale of a few minutes using micromolar concentrations of diboron. Importantly, we demonstrated that this transformation fully reverses the associative event that preceded it, releasing either small molecules or proteins in a traceless manner. It is distinct from click-to-release reactions in providing a discrete adducted intermediate with which further operations can be conducted. We employed this reaction in an antibody-drug conjugate setting, demonstrating that the cytotoxin MMAE can be released efficiently and can impact cell viability in a reagent dependent manner. Given our prior demonstration of oxygen-dependent enamine N-oxide cleavage,40 perhaps diboron and tumor hypoxia could even work synergistically to enhance drug release in certain cancers.

The key to this reaction is its simplicity. With a minimal chemical profile and featuring both impressive ligation and release properties, the described reactions alone or in concert are an important contribution to bioorthogonal reactivity. A general, rapid, chemically revertible bioconjugation strategy provides a mechanism for the transient modification of biomolecules in a complex biological setting, and we envision this fundamental operational unit of click and release to enable diverse applications such as the introduction of directing groups in a biological setting to facilitate the site- and chemoselective functionalization of proteins, nucleic acids, and much more. The need to both form and break bonds are fundamental chemical operations, and we expect that these reactions could have impact in areas of chemistry beyond the chemistry-biology interface.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Justin Kim (Justin_Kim@dfci.harvard.edu).

Materials availability

All materials generated in this study are available from the lead contact.

Data and code availability

All data relevant to this paper has been provided in the supplemental information; any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Supplementary Material

Bigger Picture.

Bioorthogonal chemistry provides an important mechanism by which chemists can interface with biological systems. Both bioorthogonal ligation and cleavage reactions have undergone intense development over the past two decades; however, these developments have focused on either associative or dissociative transformations independently. Here, we provide a paired set of associative and dissociative bioorthogonal transformations that interface with one another and can be used in tandem to achieve the revertible attachment of two molecules in complex biological contexts. The bioconjugates that we formed through the initial hydroamination reaction could be dissociated in a subsequent transformation that was rapid, directional, complete, and compatible with a wide range of complex biological media. This transformation can be used for the rapid on-demand release of drugs or other small molecules from biomacromolecules as we demonstrated using antibody-drug conjugates.

Highlights.

Integrated suite of associative and dissociative bioorthogonal transformations

Dissociative reaction is directional, traceless, rapid, and complete

Reactions tolerate a broad range of buffers, pH’s, and complex biological media

Revertible bioconjugation reactions can be used for drug delivery

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Scott Ficarro and the DFCI Blais Proteomics Center for assistance with protein mass spectrometry. This research was supported by the NIH NIEHS (1DP2ES030448) and the Claudia Adams Barr Program for Innovative Cancer Research.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

J.K. and D.K. are inventors on a provisional U.S. patent application 63/170,705 based in part on this work. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sletten EM, and Bertozzi CR (2009). Bioorthogonal chemistry: Fishing for selectivity in a sea of functionality. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 48, 6974–6998. 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker CG, and Pratt MR (2020). Click Chemistry in Proteomic Investigations. Cell 180, 605–632. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takayama Y, Kusamori K, and Nishikawa M (2019). Click Chemistry as a Tool for Cell Engineering and Drug Delivery. Molecules 24, 172. 10.3390/molecules24010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolb HC, Finn MG, and Sharpless KB (2001). Click Chemistry: Diverse Chemical Function from a Few Good Reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 40, 2004–2021. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.George JT, and Srivatsan SG (2020). Bioorthogonal chemistry-based RNA labeling technologies: evolution and current state. Chem. Comm 56, 12307–12318. 10.1039/D0CC05228K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flores J, White BM, Brea RJ, Baskin JM, and Devaraj NK (2020). Lipids: chemical tools for their synthesis, modification, and analysis. Chemical Society Reviews 49, 4602–4614. 10.1039/D0CS00154F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agard NJ, and Bertozzi CR (2009). Chemical Approaches To Perturb, Profile, and Perceive Glycans. Accounts of Chemical Research 42, 788–797. 10.1021/ar800267j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xi W, Scott TF, Kloxin CJ, and Bowman CN (2014). Click Chemistry in Materials Science. Advanced Functional Materials 24, 2572–2590. 10.1002/adfm.201302847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moses JE, and Moorhouse AD (2007). The growing applications of click chemistry. Chemical Society Reviews 36, 1249–1262. 10.1039/b613014n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Wang X, Fan X, and Chen PR (2021). Unleashing the Power of Bond Cleavage Chemistry in Living Systems. ACS Central Science 7, 929–943. 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji X, Pan Z, Yu B, De La Cruz LK, Zheng Y, Ke B, and Wang B (2019). Click and release: bioorthogonal approaches to “on-demand” activation of prodrugs. Chem. Soc. Rev 48, 1077–1094. 10.1039/C8CS00395E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tu J, Xu M, and Franzini RM (2019). Dissociative Bioorthogonal Reactions. ChemBioChem 20, 1615–1627. 10.1002/cbic.201800810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, Hall KP, Evers DJ, Barnes CL, Bignell HR, et al. (2008). Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 456, 53–59. 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Yu J, Zhao J, Wang J, Zheng S, Lin S, Chen L, Yang M, Jia S, Zhang X, and Chen PR (2014). Palladium-triggered deprotection chemistry for protein activation in living cells. Nat. Chem 6, 352–361. 10.1038/nchem.1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Q, Wang Y, Ding J, Wang C, Zhou X, Gao W, Huang H, Shao F, and Liu Z (2020). A bioorthogonal system reveals antitumour immune function of pyroptosis. Nature 579, 421–426. 10.1038/s41586-020-2079-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossin R, Versteegen RM, Wu J, Khasanov A, Wessels HJ, Steenbergen EJ, Ten Hoeve W, Janssen HM, Van Onzen AHAM, Hudson PJ, and Robillard MS (2018). Chemically triggered drug release from an antibody-drug conjugate leads to potent antitumour activity in mice. Nat. Commun 9, 1484. 10.1038/s41467-018-03880-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossin R, Van Duijnhoven SMJ, Ten Hoeve W, Janssen HM, Kleijn LHJ, Hoeben FJM, Versteegen RM, and Robillard MS (2016). Triggered Drug Release from an Antibody-Drug Conjugate Using Fast “click-to-Release” Chemistry in Mice. Bioconjugate Chem. 27, 1697–1706. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mejia Oneto JM, Khan I, Seebald L, and Royzen M (2016). In Vivo Bioorthogonal Chemistry Enables Local Hydrogel and Systemic Pro-Drug To Treat Soft Tissue Sarcoma. ACS Central Science 2, 476–482. 10.1021/acscentsci.6b00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shieh P, Hill MR, Zhang W, Kristufek SL, and Johnson JA (2021). Clip Chemistry: Diverse (Bio)(macro)molecular and Material Function through Breaking Covalent Bonds. Chemical Reviews 121, 7059–7121. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streu C, and Meggers E (2006). Ruthenium-induced allylcarbamate cleavage in living cells. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 45, 5645–5648. 10.1002/anie.200601752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latocheski E, Dal Forno GM, Ferreira TM, Oliveira BL, Bernardes GJL, and Domingos JB (2020). Mechanistic insights into transition metal-mediated bioorthogonal uncaging reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev 49, 7710–7729. 10.1039/D0CS00630K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang M, Li J, and Chen PR (2014). Transition metal-mediated bioorthogonal protein chemistry in living cells. Chem. Soc. Rev 43, 6511–6526. 10.1039/C4CS00117F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pawlak JB, Gential GPP, Ruckwardt TJ, Bremmers JS, Meeuwenoord NJ, Ossendorp FA, Overkleeft HS, Filippov DV, and Van Kasteren SI (2015). Bioorthogonal deprotection on the dendritic cell surface for chemical control of antigen cross-presentation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 54, 5628–5631. 10.1002/anie.201500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Brakel R, Vulders RCM, Bokdam RJ, Grüll H, and Robillard MS (2008). A doxorubicin prodrug activated by the staudinger reaction. Bioconjugate Chem. 19, 714–718. 10.1021/bc700394s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Versteegen RM, Rossin R, Ten Hoeve W, Janssen HM, and Robillard MS (2013). Click to release: Instantaneous doxorubicin elimination upon tetrazine ligation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 52, 14112–14116. 10.1002/anie.201305969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blackman ML, Royzen M, and Fox JM (2008). Tetrazine ligation: Fast bioconjugation based on inverse-electron-demand Diels-Alder reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 13518–13519. 10.1021/ja8053805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saxon E, and Bertozzi CR (2000). Cell Surface Engineering by a Modified Staudinger Reaction. Science 287, 2007–2010. 10.1126/science.287.5460.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Onzen A, Versteegen RM, Hoeben FJM, Filot IAW, Rossin R, Zhu T, Wu J, Hudson PJ, Janssen HM, Ten Hoeve W, and Robillard MS (2020). Bioorthogonal Tetrazine Carbamate Cleavage by Highly Reactive trans-Cyclooctene. J. Am. Chem. Soc 142, 10955–10963. 10.1021/jacs.0c00531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Versteegen RM, ten Hoeve W, Rossin R, de Geus MAR, Janssen HM, and Robillard MS (2018). Click-to-Release from trans-Cyclooctenes: Mechanistic Insights and Expansion of Scope from Established Carbamate to Remarkable Ether Cleavage. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 57, 10494–10499. 10.1002/anie.201800402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu M, Tu J, and Franzini RM (2017). Rapid and efficient tetrazine-induced drug release from highly stable benzonorbornadiene derivatives. Chem. Commun 53, 6271–6274. 10.1039/C7CC03477F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilkovitsch M, Haider M, Sohr B, Herrmann B, Klubnick J, Weissleder R, Carlson JCT, and Mikula H (2020). Cleavable C2-Symmetric trans-Cyclooctene Enables Fast and Complete Bioorthogonal Disassembly of Molecular Probes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 142, 19132–19141. 10.1021/jacs.0c07922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson JCT, Mikula H, and Weissleder R (2018). Unraveling Tetrazine-Triggered Bioorthogonal Elimination Enables Chemical Tools for Ultrafast Release and Universal Cleavage. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 3603–3612. 10.1021/jacs.7b11217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H, Alexander SC, Jin S, and Devaraj NK (2016). A Bioorthogonal Near-Infrared Fluorogenic Probe for mRNA Detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc 138, 11429–11432. 10.1021/jacs.6b01625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lelieveldt L, Eising S, Wijen A, and Bonger KM (2019). Vinylboronic acid-caged prodrug activation using click-to-release tetrazine ligation. Org. Biomol. Chem 17, 8816–8821. 10.1039/C9OB01881F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zheng Y, Ji X, Yu B, Ji K, Gallo D, Csizmadia E, Zhu M, Choudhury MR, De La Cruz LKC, Chittavong V, et al. (2018). Enrichment-Triggered prodrug activation demonstrated through mitochondria-Targeted delivery of doxorubicin and carbon monoxide. Nat. Chem 10, 787–794. 10.1038/s41557-018-0055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tu J, Xu M, Parvez S, Peterson RT, and Franzini RM (2018). Bioorthogonal Removal of 3-Isocyanopropyl Groups Enables the Controlled Release of Fluorophores and Drugs in Vivo. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 8410–8414. 10.1021/jacs.8b05093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossin R, Van Den Bosch SM, Ten Hoeve W, Carvelli M, Versteegen RM, Lub J, and Robillard MS (2013). Highly reactive trans-cyclooctene tags with improved stability for diels-alder chemistry in living systems. Bioconjugate Chem. 24, 1210–1217. 10.1021/bc400153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo J, Liu Q, Morihiro K, and Deiters A (2016). Small-molecule control of protein function through Staudinger reduction. Nat. Chem 8, 1027–1034. 10.1038/nchem.2573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim J, and Bertozzi CR (2015). A Bioorthogonal Reaction of N-Oxide and Boron Reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 54, 15777–15781. 10.1002/anie.201508861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang D, Cheung ST, Wong-Rolle A, and Kim J (2021). Enamine N-Oxides: Synthesis and Application to Hypoxia-Responsive Prodrugs and Imaging Agents. ACS Cent. Sci 7, 631–640. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang D, and Kim J (2021). Bioorthogonal Retro-Cope Elimination Reaction of N,N-Dialkylhydroxylamines and Strained Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 143, 5616–5621. 10.1021/jacs.1c00885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kang D, Cheung ST, and Kim J (2021). Bioorthogonal Hydroamination of Push-Pull-Activated Linear Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 60, 16947–16952. 10.1002/anie.202104863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moran J, Gorelsky SI, Dimitrijevic E, Lebrun M-E, Bédard A-C, Séguin C, and Beauchemin AM (2008). Intermolecular Cope-Type Hydroamination of Alkenes and Alkynes using Hydroxylamines. Journal of the American Chemical Society 130, 17893–17906. 10.1021/ja806300r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu C, Wang R, and Falck JR (2012). Mild and Rapid Hydroxylation of Aryl/Heteroaryl Boronic Acids and Boronate Esters with N-Oxides. Organic Letters 14, 3494–3497. 10.1021/ol301463c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kokatla HP, Thomson PF, Bae S, Doddi VR, and Lakshman MK (2011). Reduction of Amine N-Oxides by Diboron Reagents. The Journal of Organic Chemistry 76, 7842–7848. 10.1021/jo201192c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carter CAG, John KD, Mann G, Martin RL, Cameron TM, Baker RT, Bishop KL, Broene RD, and Westcott SA (2002). Bifunctional Lewis Acid Reactivity of Diol-Derived Diboron Reagents. In Group 13 Chemistry/From Fundamentals to Applications, Shapiro PJ, and Atwood DA, eds. (American Chemical Society; ), pp. 70–87. 10.1021/bk-2002-0822.ch005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gao M, Thorpe SB, and Santos WL (2009). sp2–sp3 Hybridized Mixed Diboron: Synthesis, Characterization, and Copper-Catalyzed β-Boration of α,β-Unsaturated Conjugated Compounds. Organic Letters 11, 3478–3481. 10.1021/ol901359n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshida H, Seki M, Kageyuki I, Osaka I, Hatano S, and Abe M (2017). B(MIDA)-Containing Diborons. ACS Omega 2, 5911–5916. 10.1021/acsomega.7b01042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou Z, Feng S, Zhou J, Ji X, and Long Y-Q (2022). On-Demand Activation of a Bioorthogonal Prodrug of SN-38 with Fast Reaction Kinetics and High Releasing Efficiency In Vivo. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 65, 333–342. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagendorn T, and Bräse S (2014). A Route to Cyclooct-2-ynol and Its Functionalization by Mitsunobu Chemistry. European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2014, 1280–1286. 10.1002/ejoc.201301375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nikic I, Kang JH, Girona GE, Aramburu IV, and Lemke EA (2015). Labeling proteins on live mammalian cells using click chemistry. Nat. Protoc 10, 780–791. 10.1038/nprot.2015.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to this paper has been provided in the supplemental information; any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.