Abstract

The nucleoid-associated proteins H-NS and StpA in Escherichia coli bind DNA as oligomers and are implicated in gene regulatory systems. There is evidence for both homomeric and heteromeric H-NS–StpA complexes. The two proteins show differential turnover, and StpA was previously found to be subject to protease-mediated degradation by the Lon protease. We investigated which regions of the H-NS protein are able to prevent degradation of StpA. A set of truncated H-NS derivatives was tested for their ability to mediate StpA stability and to form heteromers in vitro. The data indicate that H-NS interacts with StpA at two regions and that the presence of at least one of the H-NS regions is necessary for StpA stability. Our results also suggest that a proteolytically stable form of StpA, StpAF21C, forms dimers, whereas wild-type StpA in the absence of H-NS predominantly forms tetramers or oligomers, which are more susceptible to proteolysis.

The H-NS protein of Escherichia coli is a major component of the bacterial nucleoid and has been shown to affect several cellular processes, such as gene expression, recombination, transposition, and phage transposition (reviewed in references 1 and 24). The H-NS protein binds DNA in a relatively nonspecific manner but with some preference for curved sequences, and high overexpression of H-NS causes a detrimental compaction of the chromosome (3, 6, 20, 21, 26). The H-NS protein negatively regulates expression from the cryptic bgl operon, probably by binding to an AT-rich nucleation site near the bgl promoter where a nucleoprotein complex is formed. The site extends over the bgl promoter and thereby abolishes expression (16). An H-NS paralogue, StpA, has 58% identity to H-NS and is able to functionally substitute for H-NS in several cases, although it also displays unique properties of its own (19, 27, 28). Recent findings suggest that H-NS and StpA stimulate the expression of stringently regulated genes by their effect on local DNA topology (10). The extensive identity between H-NS and StpA suggests that they are able to form heteromers, and Williams et al. (25) were able to cross-link StpA with the 64 N-terminal amino acids of H-NS. Functionally, the interaction between the StpA protein and the H-NS64 peptide was important for silencing of the bgl operon, and the StpA protein was suggested to function as a molecular adapter (7). Recently, we found that the StpA protein, in the absence of H-NS, was susceptible to Lon protease proteolysis, whereas StpA was stable in the presence of H-NS (12). This suggests that StpA is present mainly in heteromeric form with H-NS in the cell.

In this study, we investigated what parts of H-NS are able to mediate StpA stability. We present evidence that the protease-susceptible wild-type StpA protein (StpAwt) forms tetramers and oligomers in the absence of H-NS, whereas the stable mutant protein StpAF21C predominantly forms dimers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The strains used in this study were described before (11, 12): BSN26 (MC4100 trp::Tn10), BSN27 (MC4100 trp::Tn10, Δhns), BSN29 (MC4100 trp::Tn10 Δhns stpA60::Kmr), JGJ212 (MC4100 zfi-3143::Tn10 Kmr StpAwt), JGJ213 (MC4100 zfi-3143::Tn10 Kmr StpAF21C), JGJ214 (MC4100 zfi-3143::Tn10 Kmr StpAwt hns::Cmr), JGJ215 (MC4100 zfi-3143::Tn10 Kmr StpAF21C hns::Cmr), JGJ221 (Δhns), and JGJ223 (Δhns lon).

Growth media and culture conditions.

The different strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (2) at 37°C with vigorous shaking (220 rpm). Growth was monitored by measuring Klett units on a Klett-Summerson colorimeter, where 50 Klett units corresponds approximately to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.4. Where necessary, the following antibiotics (Sigma) were used: carbenicillin, 50 μg/ml; kanamycin, 25 or 50 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml; and tetracycline, 7.5 μg/ml. Plates containing 40 μg of the chromogen β-glucoside 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (Sigma)/ml were used to monitor the Bgl phenotype expressed by the different hns deletion derivatives. Activity of the bgl operon was determined by the color of single colonies, where blue colonies represent full derepression.

Construction of plasmids.

Molecular genetic manipulations were performed essentially as described elsewhere (15). Primer hns-up2 (5′-CCCGAATTCCCTCAACAAACC-3′), binding upstream of the hns gene and containing an EcoRI restriction enzyme site, was used together with either primer hns-Δ60 (5′-TTATCAATATTGCTGCAGCTTACG-3′), coding for the first 60 amino acids, primer hns-Δ80c (5′-TTATCAACGTTCGTTCGTTAACGACAAC-3′), coding for the first 80 amino acids, or primer 8 (5′-CAAATAAAGCAAATAAAG-3′), binding downstream of the hns gene and thereby coding for a full-length H-NS protein. These three primer combinations were used on a wild-type hns sequence (pHMG409) (9), creating pJOB101 (wild type), pJOB103 (N60), and pJOB104 (N80), respectively. Furthermore, primer hns-up2, together with either primer hns-Δ80 or primer 8, was used on a construct lacking an NruI fragment of the hns sequence, creating an in-frame deletion of 21 codons; the resulting constructs were named pJOB105 (N80Δ39–60) and pJOB107 (Δ39–60), respectively. The QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) was used to create the amino acid substitution mutant C21F (pJOB108), containing a phenylalanine instead of a cysteine at position 21. Wild-type plasmid (pJOB101) was used as the template. Primers hns-O (5′-GCGCAGGCAAGAGAATTCACACTTGAAACGCTGG-3′) and hns-U (5′-CCAGCGTTTCAAGTGTGAATTCTCTTGCCTGCGC-3′) were used to create the desired base pair substitution. The PCR fragments were digested with EcoRI, cloned into the EcoRI/SmaI site of pCL1921 (13), and then sequenced. Subsequently, the constructs were digested with EcoRI/BamHI and cloned into the EcoRI/BamHI site of the IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside)-inducible plasmid pMMB66EH (8). Strains BSN26, BSN27, and BSN29 were transformed with the constructs. In order to analyze the presence and stability of the truncated versions of H-NS, strains containing the different constructs were grown to 50 Klett units in the presence of 10−5 M IPTG, and protein synthesis was inhibited by the addition of 100 mg of spectinomycin/ml. Extracts were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and silver staining, and the constructs were found to be stable (see Fig. 1B). These results are in keeping with the finding by Ueguchi et al. (22), who found that several truncated forms of H-NS are stable.

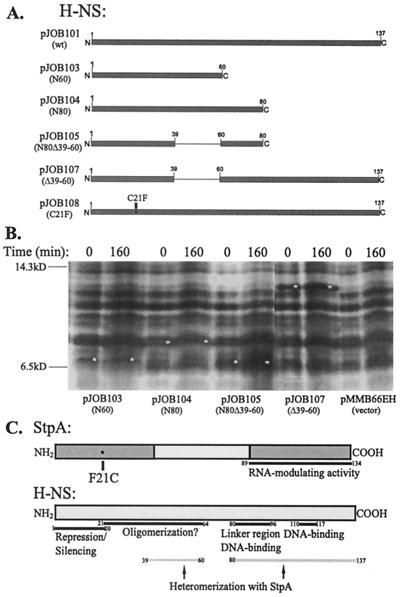

FIG. 1.

(A). Overview of the truncated H-NS peptides used in this study. The numbers above the lines indicate the amino acid positions. (B) Gel electrophoretic analysis of the presence and stability of the truncated versions of H-NS. Strains containing the different constructs were grown to 50 Klett units in the presence of 10−5 M IPTG, and protein synthesis was inhibited by the addition of 100 mg of spectinomycin/ml at 50 Klett units. Extracts were analyzed by SDS–20% PAGE and silver staining. White stars indicate bands that represent the H-NS peptide synthesized from plasmids pJOB103, pJOB104, pJOB105, and pJOB107. (C). Schematic representation of StpA and H-NS. Black horizontal bars show suggested functional domains based on earlier findings (4, 7, 17, 18, 22, 23, 25). Grey horizontal bars below H-NS show regions implicated in heteromerization as deduced from this study. Numbers indicate amino acid positions, where 1 is the N-terminal methionine.

Gel electrophoresis and Western blotting.

Bacteria were pelleted and resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The different samples were subsequently subjected to SDS-PAGE (10, 15, or 20% polyacrylamide). For immunoblot detection the gel was blotted onto a 0.2-mm-pore-size polyvinylidene difluoride transfer membrane (Bio-Rad) by use of a semidry blotting apparatus. Polyclonal rabbit antiserum directed against StpA was used as the primary antibody. Further visualization and quantification were done using chemifluorescent detection as described previously (11) or using the ECL-plus kit as described by the manufacturer (Amersham Pharmacia). All data are averages of at least two independent experiments.

In vivo protein stability experiment.

To determine the intracellular stability of the StpA and H-NS proteins, we followed a previously described method (12). Protein stability was monitored after the protein synthesis had been inhibited by the addition of spectinomycin (100 μg ml−1) to bacterial cultures grown to 50 Klett units in LB medium containing 10−5 M IPTG at 37°C. Samples to be analyzed by Western blotting were removed at various time points.

Protein-protein cross-linking.

The peptides were cross-linked with dimethyl suberimidate (DMS; Sigma) by a method described by Ueguchi et al. (23). Cells for cross-linking were harvested from 5 ml of the culture, washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), and subsequently freeze-thawed in the same buffer. Thereafter, the cells were resuspended in cross-linking buffer (1 M triethanolamine-HCl [pH 8.5], 0.25 M NaCl, and 5 mM dithiothreitol). The cell extracts were sonicated and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 30 min, and the supernatants were incubated at room temperature without or with DMS (1 mg ml−1). After incubation for 30 or 60 min, the samples were precipitated with trichloroacetic acid and then resuspended in SDS-PAGE buffer.

RESULTS

Truncated versions of H-NS stabilize StpA.

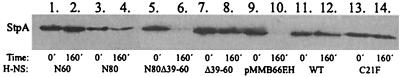

In a previous study we showed that the StpA protein was unstable in the absence of H-NS, whereas it remained stable in the presence of H-NS (12). In order to get further insight into the molecular interactions between H-NS and StpA, we wanted to analyze what regions of the H-NS protein mediated this stability. To do so, genes encoding truncated versions of H-NS (Fig. 1A) were constructed (see Materials and Methods) and cloned behind an IPTG-inducible tac promoter. Since the StpA protein is unstable in the absence of H-NS, the protein stability experiment was performed in the hns strain (BSN27) containing plasmid constructs encoding the truncated versions of the hns gene. The strains were grown to 50 Klett units in LB medium containing 10−5 M IPTG prior to the addition of spectinomycin, and samples were removed at various time points. The results (Fig. 2) clearly demonstrated that strains containing the pJOB101 (wild type), pJOB103 (N60), pJOB104 (N80), and pJOB107 (Δ39–60) plasmids retained similar levels of StpA 160 min after the addition of spectinomycin. In the case of the N80 peptide there was some reduction, but levels of at least 50% were retained after 160 min. This suggests that these H-NS peptides were able to prevent proteolysis of StpA. In contrast, strains containing the vector plasmid or the construct pJOB105 (N80Δ39–60) did not contain detectable levels of StpA 160 min after the addition of spectinomycin, indicating that these plasmids were unable to prevent StpA proteolysis.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of stability of the StpA protein. The level of StpA was measured in an hns mutant strain (BSN27) expressing different H-NS derivatives encoded on plasmids pJOB101 (lanes 11 and 12), pJOB103 (lanes 1 and 2), pJOB104 (lanes 3 and 4), pJOB105 (lanes 5 and 6), pJOB107 (lanes 7 and 8), and pMMB66EH (lanes 9 and 10). These strains were grown to 50 Klett units in LB medium containing 10−5 M IPTG, and protein synthesis was subsequently inhibited by the addition of spectinomycin. Samples were removed at indicated time points. Processing and Western blotting were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

Previously, we showed that a single amino acid change (phenylalanine to cysteine at position 21 [Fig. 1C]) within StpA made the protein stable (12). Interestingly, a cysteine is present at that position in H-NS, and to test if this particular residue was essential for the stability of H-NS and/or for the interaction between H-NS and StpA we constructed an inducible plasmid (pJOB108) that encoded an H-NS protein with an amino acid change from cysteine to phenylalanine at position 21 (see Materials and Methods). When tested in a stability experiment (using strain BSN27/pJOB108), the H-NSC21F mutant protein was as stable as the wild-type protein (data not shown). As seen in Fig. 2 (lanes 13 and 14), the H-NSC21F protein was still able to prevent proteolysis of StpA under the conditions tested.

H-NS constructs able to prevent proteolysis of StpA also interact with StpA.

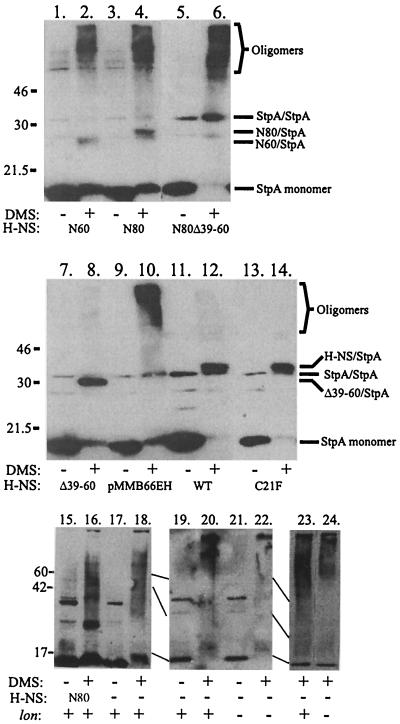

A possible explanation for the stabilization of StpA by the N60, N80, and Δ39–60 H-NS constructs would be that the StpA protein could directly interact with the H-NS polypeptides and thereby be protected from Lon-mediated proteolysis. In order to test this hypothesis, we grew the hns strain (BSN27) containing plasmid constructs encoding the truncated versions of the hns gene to 50 Klett units in LB medium containing 10−5 M IPTG, prior to performing a cross-linking experiment. Protein extracts were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis as shown in Fig. 3. Half of the samples were exposed to DMS, whereas the other half were untreated (Materials and Methods). The results clearly suggested that strains containing pJOB101, pJOB103, pJOB104, pJOB107, or pJOB108 produced H-NS polypeptides able to interact and cross-link with StpA as heterodimers. The results of experiments illustrated in Fig. 2 and 3 suggest that H-NS interacts with StpA at two separate domains, one situated in the middle portion and the other located in the C terminus of the H-NS protein. Also, the prevention of StpA proteolysis requires at least one of these domains.

FIG. 3.

Interaction between StpA and different H-NS derivatives. Chemical cross-linking was performed with an hns mutant strain (BSN27) expressing different H-NS derivatives encoded on plasmids pJOB101 (lanes 11 and 12), pJOB103 (lanes 1 and 2), pJOB104 (lanes 3, 4, 15, and 16), pJOB105 (lanes 5 and 6), pJOB107 (lanes 7 and 8), and pMMB66EH (lanes 9, 10, 17, and 18). BSN27 strains were grown to 50 Klett units in LB medium containing 10−5 M IPTG prior to sampling and cross-linking with DMS (Materials and Methods). Positions of different presumed StpA forms were revealed by Western blotting using anti-StpA antisera. Cross-linking experiments with strains JGJ221 (lanes 19, 20, and 23) and JGJ223 (lanes 21, 22, and 24) were performed to test how a lon mutation might influence StpA multimer formation. The strains were grown in LB medium, and samples were subjected to DMS treatment as in the case of BSN27 derivatives. Lanes 1 to 14 show results from 60-min DMS treatment, and lanes 15 to 24 show results from 30-min DMS treatment. The gel used in lanes 23 and 24 was 10%, whereas 15% gels were used in all other cases. Positions of molecular size markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left.

Interestingly, whereas both the wild type and the Δ39–60 peptide, seemed to “trap” the StpA protein in a dimer conformation (Fig. 3, lane 8 and 12), the N60 and the N80 peptides could mediate such trapping only partially. Instead, several bands migrating more slowly appeared in these wells (Fig. 3, lane 2 and 4). We believe that these bands are oligomeric forms of StpA (tetramers and oligomers). The relative amounts of multimeric forms appeared to differ somewhat between different constructs. Shorter cross-linking treatments emphasized the difference, and an example is shown by N80 (in comparison with its vector control) in Fig. 3, lanes 16 to 18. The N80-StpA heterodimer was evidently the multimer present in most significant quantity. In contrast, the N80Δ39–60 peptide was not able to form heterodimers with StpA. In this case the StpA protein formed predominantly oligomers, with some dimer formation as well (Fig. 3, lane 6).

Previous results showed that the Lon protease was involved in the turnover of StpA (12). It was therefore of interest to find out if StpA formed dimers or larger oligomers in a lon hns mutant strain. Samples of strains JGJ221 (hns lon+) and JGJ223 (hns lon) were accordingly subjected to cross-linking tests as described above. As shown in Fig. 3, lanes 19 to 24, there was no indication of increased StpA dimer formation in the lon mutant derivative but the majority of StpA seemed to be present in relatively large oligomers.

The interaction between the H-NS derivatives and StpA mediates bgl silencing.

Free et al. (7) reported results suggesting that the StpA protein was able to function as a molecular adapter for an H-NS protein lacking DNA-binding function in the repression of the bgl operon. Intriguingly, Ohta et al. (14) could not repeat that experiment, but as discussed by those authors (14), this anomaly may be due to different strain backgrounds, since Free et al. (7) used an MC4100 derivative whereas Ohta et al. (14) used a CSH26 background. We wanted to analyze our truncated H-NS derivatives for their ability to repress bgl expression and therefore used three different strains derived from MC4100, a wild-type (BSN26), an hns (BSN27), and an hns stpA (BSN29) strain containing our constructs. As seen in Table 1, the results indicate that the heterodimers formed between StpA and the H-NS derivatives in the hns strain (BSN27) were also able to repress bgl expression. The results also suggest that StpA is able to function as a molecular adapter for truncated H-NS, since no repression of the bgl expression could be monitored in an hns stpA strain (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effect of H-NS derivatives on the Bgl phenotypea

| H-NS construct or strain | Wild type (BSN26) | hns (BSN27) | hns stpA (BSN29) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | − | +++ | +++ |

| N60 | − | (+) | +++ |

| N80 | − | − | +++ |

| N80Δ39–60 | − | +++ | +++ |

| Δ39–60 | − | − | +++ |

| Wild type | − | − | − |

The strains containing the constructs were grown in the presence of 10−5 M IPTG on solid medium. −, negative Bgl phenotype; (+), +++, maximal Bgl phenotype. The experiments were repeated three times with identical results.

In this context we also note that bgl expression was not repressed in the hns lon mutant strain (JGJ223) as judged by tests on indicator plates.

The StpAF21C protein predominantly forms dimers.

Our previous finding that the StpAF21C protein was proteolytically stable, even in the absence of H-NS (12), prompted us to compare the ability of StpAwt and StpAF21C to multimerize. To investigate this, we used both hns+ and hns mutant strains containing either stpAwt or the stpAF21C allele. The strains were grown to 50 Klett units in LB medium before they were subjected to cross-linking experiments with DMS (Materials and Methods). In the presence of H-NS, both StpAwt and StpAF21C predominantly formed heterodimers together with H-NS (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 4), since no oligomers could be detected under such conditions. However, in the absence of H-NS, the proteolytically unstable StpAwt protein predominantly formed oligomers (Fig. 4A, lane 6). Quantitative measurements showed that more than 60% of the StpAwt protein was present as oligomers and about 20% each was present as monomers and dimers (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, only a small fraction (<10%) of the stable StpAF21C protein formed oligomers in the absence of H-NS. Instead, most of the StpAF21C protein was detected as monomers and dimers after cross-linking (Fig. 4A, lane 8, and 4B).

FIG. 4.

Formation of StpA monomers, dimers, and oligomers. (A) Western blot analysis of StpA after chemical cross-linking using DMS. Lanes 1 and 2, hns+ stpAwt (JGJ212); lanes 3 and 4, hns+ stpAF21C (JGJ213); lanes 5 and 6, hns stpAwt (JGJ214); and lanes 7 and 8, hns stpAF21C (JGJ215). The bacterial strains were grown to 50 Klett units in LB medium prior to sampling (Materials and Methods). Positions of presumed StpA forms and positions of molecular weight markers are indicated beside the gel. (B) The relative amounts of the different forms of StpA from panel A were monitored as described in Materials and Methods. ∗, not detected.

DISCUSSION

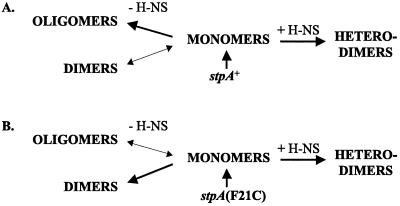

In this work we compared the multimerizing ability of the StpAwt and StpAF21C proteins. Our results suggest that in the absence of H-NS, the StpAwt protein forms dimers to a much lesser extent than the StpAF21C protein, which traps the StpA molecule in a dimeric form. Instead, most of the StpAwt can be found as oligomers (tetramers and oligomers) (Fig. 4). The results of this study (Fig. 3 and 4) together with earlier findings (12) suggest the following model (Fig. 5). The StpAwt protein is unable to form stable dimers and instead forms oligomers that are susceptible to degradation by the Lon protease. In contrast, the StpAF21C protein predominantly forms stable dimers, which are not degraded. The StpAF21C protein has probably undergone a conformational change revealing a dimerization site that is normally “masked” in StpAwt but is available in H-NS.

FIG. 5.

Schematic summary of how different molecular forms of wild-type (A) and F21C mutant (B) StpA may appear in the presence or absence of H-NS.

Our results also suggest that the StpA protein is largely protected from proteolysis in the presence of three truncated H-NS derivatives (Fig. 2) and that the protection is mediated by a direct interaction between the StpA protein and the H-NS peptide (Fig. 3). We also show evidence demonstrating that such an interaction functionally represses bgl expression in a strain lacking normal H-NS (Table 1). The present data suggest that the H-NS protein is able to interact with the StpA protein at two distinct domains, one situated between amino acids 39 and 60 and the other located between amino acid 80 and the C terminus (Fig. 1C). Previous reports have also identified C-terminally deleted H-NS as being able to interact with StpA (7, 25) and to repress bgl expression in the presence of StpA (7). However, we also show here that an H-NS molecule lacking the middle portion of the protein is still able to interact with, and prevent degradation of, StpA. This StpA-Δ39–60 complex can also repress bgl expression in the absence of H-NS. Previously, the oligomerization domain of H-NS has been suggested to reside within the N-terminal or middle portion of the protein, whereas the C-terminal part has been suggested to mediate DNA binding (18, 22, 24). Williams et al. (25) discussed the possibility of an alteration of the nucleic acid binding after heteromerization between H-NS and StpA. Our results do not contradict this, but they may indeed indicate a possible difference between H-NS–H-NS homomerization and H-NS–StpA heteromerization. Perhaps the C-terminal interaction between H-NS and StpA alters the DNA-binding ability of the proteins and thereby causes a change in the DNA motif recognized.

The physiological roles of different H-NS–StpA complexes are not yet known. The findings that there are both differential expression and turnover of the proteins suggest that levels of homomeric and heteromeric complexes can be regulated (12, 19). Furthermore, it will be of interest to find out if other proteins with similarities to H-NS in the C-terminal domain (5) might also be involved in complex formation with H-NS and/or StpA.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Monica Persson for assistance with the experiments. We thank Carlos Balsalobre for valuable suggestions.

This work was supported by grants from the J. C. Kempe Foundation, the Swedish Natural Science Research Council, the Swedish Medical Research Council, the Wenner-Gren Foundations, and the Göran Gustafsson Foundation for Research in Natural Sciences and Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atlung T, Ingmer H. H-NS: a modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3151679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertani G. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1951;63:293–300. doi: 10.1128/jb.62.3.293-300.1951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bracco L, Kotlarz D, Kolb A, Diekmann S, Buc H. Synthetic curved DNA sequences can act as transcriptional activators in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1989;8:4289–4296. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cusick E M, Belfort M. Domain structure and RNA annealing activity of the Escherichia coli regulatory protein StpA. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:847–857. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00848.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorman C J, Hinton J C D, Free A. Domain organization and oligomerization among H-NS-like nucleoid-associated proteins in bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:124–128. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durrenberger M, La Teana A, Citro G, Venanzi F, Gualerzi C O, Pon C L. Escherichia coli DNA-binding protein H-NS is localized in the nucleoid. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:373–380. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90106-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Free A, Williams R M, Dorman C J. The StpA protein functions as a molecular adapter to mediate repression of the bgl operon by truncated H-NS in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:994–997. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.994-997.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furste J P, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blocker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Göransson M, Sondén B, Nilsson P, Dagberg B, Forsman K, Emanuelsson K, Uhlin B E. Transcriptional silencing and thermoregulation of gene expression in Escherichia coli. Nature. 1990;344:682–685. doi: 10.1038/344682a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson J, Balsalobre C, Wang S Y, Urbonaviciene J, Jin D J, Sondén B, Uhlin B E. Nucleoid proteins stimulate stringently controlled bacterial promoters: a link between the cAMP-CRP and the (p)ppGpp regulons in Escherichia coli. Cell. 2000;102:475–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansson J, Dagberg B, Richet E, Uhlin B E. H-NS and StpA proteins stimulate expression of the maltose regulon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6117–6125. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6117-6125.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson J, Uhlin B E. Differential protease-mediated turnover of H-NS and StpA revealed by a mutation altering protein stability and stationary-phase survival of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10776–10781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerner C G, Inouye M. Low copy number plasmids for regulated low-level expression of cloned genes in Escherichia coli with blue/white screening capability. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4631. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.15.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohta T, Ueguchi C, Mizuno T. rpoS function is essential for bgl silencing caused by C-terminally truncated H-NS in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6278–6283. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6278-6283.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schnetz K, Wang J C. Silencing of the Escherichia coli bgl promoter: effects of template supercoiling and cell extracts on promoter activity in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:2422–2428. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.12.2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shindo H, Iwaki T, Ieda R, Kurumizaka H, Ueguchi C, Mizuno T, Morikawa S, Nakamura H, Kuboniwa H. Solution structure of the DNA binding domain of a nucleoid-associated protein, H-NS, from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:125–131. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00079-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shindo H, Ohnuki A, Ginba H, Katoh E, Ueguchi C, Mizuno T, Yamazaki T. Identification of the DNA binding surface of H-NS protein from Escherichia coli by heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1999;455:63–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00862-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sondén B, Uhlin B E. Coordinated and differential expression of histone-like proteins in Escherichia coli: regulation and function of the H-NS analog StpA. EMBO J. 1996;15:4970–4980. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spassky A, Rimsky S, Garreau H, Buc H. H1a, an E. coli DNA-binding protein which accumulates in stationary phase, strongly compacts DNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5321–5340. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka K, Muramatsu S, Yamada H, Mizuno T. Systematic characterization of curved DNA segments randomly cloned from Escherichia coli and their functional significance. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;226:367–376. doi: 10.1007/BF00260648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueguchi C, Seto C, Suzuki T, Mizuno T. Clarification of the dimerization domain and its functional significance for the Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J Mol Biol. 1997;274:145–151. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ueguchi C, Suzuki T, Yoshida T, Tanaka K, Mizuno T. Systematic mutational analysis revealing the functional domain organization of Escherichia coli nucleoid protein H-NS. J Mol Biol. 1996;263:149–162. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams R M, Rimsky S. Molecular aspects of the E. coli nucleoid protein, H-NS: a central controller of gene regulatory networks. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams R M, Rimsky S, Buc H. Probing the structure, function, and interactions of the Escherichia coli H-NS and StpA proteins by using dominant negative derivatives. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4335–4343. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4335-4343.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamada H, Muramatsu S, Mizuno T. An Escherichia coli protein that preferentially binds to sharply curved DNA. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1990;108:420–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang A, Belfort M. Nucleotide sequence of a newly-identified Escherichia coli gene, stpA, encoding an H-NS-like protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:6735. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.24.6735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang A, Rimsky S, Reaban M E, Buc H, Belfort M. Escherichia coli protein analogs StpA and H-NS: regulatory loops, similar and disparate effects on nucleic acid dynamics. EMBO J. 1996;15:1340–1349. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]