Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to assess the clinical efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) for treating hemothorax caused by chest trauma.

Materials and Methods

Between 2015 and 2019, 68 patients (56 male; mean age, 58.2 years) were transferred to our interventional unit for selective TAE to treat thoracic bleeding. We retrospectively investigated their demographics, angiographic findings, embolization techniques, technical and clinical success rates, and complications.

Results

Bleeding occurred mostly from the intercostal arteries (50%) and the internal mammary arteries (29.5%). Except one patient, TAE achieved technical success, defined as the immediate cessation of bleeding, in all the other patients. Four patients successfully underwent repeated TAE for delayed bleeding or increasing hematoma after the initial TAE. The clinical success rate, defined as no need for thoracotomy for hemostasis after TAE, was 92.6%. Five patients underwent post-embolization thoracotomy for hemostasis. No patient developed major TAE-related complications, such as cerebral infarction or quadriplegia.

Conclusion

TAE is a safe, effective and minimally invasive method for controlling thoracic wall and intrathoracic systemic arterial hemorrhage after thoracic trauma. TAE may be considered for patients with hemothorax without other concomitant injuries which require emergency surgery, or those who undergoing emergency TAE for abdominal or pelvic hemostasis.

Keywords: Embolotherapy, Hemothorax, Interventional Radiology, Thoracic Injuries, Thoracotomy

Abstract

목적

흉부 외상에 의해 발생한 혈흉에 대해 동맥 색전술의 임상적 효용성을 보고하고자 한다.

대상과 방법

2015년부터 2019년까지 68명의(남자 56명; 평균 나이 58.2세) 흉부 출혈에 대한 동맥색전술을 시행 받은 환자가 포함되었다. 후향적으로 환자군의 특징, 혈관조영술 소견, 색전술에 사용한 기법, 기술적 및 임상적 성공률과 합병증을 조사하였다.

결과

출혈 부위는 늑간동맥(50%)이 가장 많았고, 그다음은 내흉동맥(29.5%)이었다. 한 명을 제외한 나머지 환자에서는 즉각적인 출혈 정지로 정의된 기술적 성공을 획득할 수 있었다. 첫 동맥 색전술 이후 네 명의 환자에서 지연 출혈 또는 혈흉의 증가 소견이 있었고, 이에 대해 반복적 동맥 색전술을 시행하여 성공적인 결과를 얻었다. 동맥 색전술 후 지혈 목적의 개흉술이 필요하지 않은 것으로 정의된 임상적 성공은 92.6%로 보고되었다. 다섯 명의 환자는 지혈을 위해 색전술 후 개흉술을 시행하였다. 뇌경색이나 사지 마비와 같은 동맥 색전술과 관련한 주요 합병증은 발생하지 않았다.

결론

외상성 흉벽 및 흉곽 내 장기 손상에 의한 동맥 출혈에 대해 시행하는 동맥 색전술은 안전하고 효과적인 최소 침습적 시술이다. 외상성 혈흉 환자에서 응급 수술을 필요로 하지 않는 혈흉만 있거나, 또는 동반된 복부나 골반 손상의 지혈을 위해 응급 동맥 색전술을 시행하는 경우, 흉부 영역의 동맥 색전술을 고려할 수 있다.

INTRODUCTION

Thoracic injury is an important cause of mortality in American trauma centers and accounts for about 25% of trauma-related deaths (1). Thoracic injuries occur in approximately 60% of polytrauma cases, amounting to an estimated 300000 traumatic hemothorax cases per year in the US (2). According to the practice management guidelines of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma, the primary indication of thoracotomy in traumatic massive hemothorax is the patient's physiology (level 2 recommendation). And also, we should consider surgical exploration when the chest tube drainage is over 1500 mL during 24 hours (3).

Transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) is becoming the treatment of choice for hemorrhage in traumatic splenic, hepatic, renal, and pelvic injuries (4). However, there are no guidelines and also limited reports about embolization following traumatic thoracic injury. There are two main causes of traumatic hemothorax: one is an intrathoracic artery injury and the other is a thoracic wall artery injury that involves the intercostal arteries. To date, only a few studies suggest that the embolization of an intercostal artery or the internal mammary artery is a valuable therapeutic option for controlling hemorrhage arising from the chest wall and mediastinum (5,6,7,8,9,10). In addition, there have been no reports on the TAE of traumatic intrathoracic systemic artery injury in our knowledge.

Most cases of traumatic hemothorax can be successfully treated with a thoracotomy, but TAE has several advantages: It is a minimally invasive procedure, can be performed immediately in an emergency situation, and simultaneously with TAE for abdominal or pelvic bleeding.

In this study, we aimed to identify conditions that are amenable to TAE in patients with traumatic hemothorax, and we report on our experience with TAE of several thoracic blood vessels.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

We retrospectively reviewed the electronic medical records of all patients (n = 76) who underwent TAE for traumatic thoracic hemorrhage from 2015 to 2019 at our regional trauma center. Computed tomography (CT) was used to assess and diagnose injury and hemorrhage in all patients. Contrast-enhanced multiphase CT scans were performed with a 256-slice scanner (Revolution, GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). We defined traumatic thoracic hemorrhage as contrast extravasation from arteries in the thoracic area with or without hemothorax and/or hemomediastinum on these preprocedural CT scans. Of these patients with traumatic thoracic hemorrhage, patients with direct bleeding or injury at aorta, heart, main subclavian artery or the arteries of pulmonary circulation were not included because they are not an indication of TAE.

Eight patients who died within 48 hours in whom we could not assess the hemostatic effect of TAE were excluded. Most of these patients died from central nervous system injury, including brain hemorrhage.

Thus, 68 patients were enrolled in this study. We recorded the mechanism of injury, initial systolic blood pressure, heart rate, level of hemoglobin, amount of transfusion within the first 24 hours and injury severity score (ISS). ISS is a sum of the squares of the three highest scores in six body areas of abbreviated injury scale, which classifies the body region into six places (head/neck, face, chest, abdomen, extremities and external), and evaluates life threatening by the injury in each area, ranging from a minor score of 1 to a maximal score of 6. A major trauma is defined as the ISS > 15 (11). And we recorded time interval from admission to the emergency room to TAE, and period of hospitalization. Furthermore, details of embolotherapy, such as the targeted arteries, angiographic findings, embolic agents used, and complications after TAE were reviewed and recorded. The technical and clinical success were analyzed.

This study has been approved by the Institutional Review Committee of Pusan National University Hospital that waived informed consent of patients because of the retrospective nature of this study (IRB No. H-1807-008-068). All procedures have been conducted according to the principles embodied in the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments.

INTERVENTIONS

All patients underwent transfemoral arterial catheterization. Digital subtraction angiography of the thoracic aorta was performed using a 5.0-Fr pigtail catheter, followed by selective angiography of the targeted arteries to identify the bleeding site on a uniplanar angiography suite (Infinix-i, Canon Medical Systems Corporation, Tochigi, Japan; or AXIOM Artis Zee; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using a 5-Fr Rösch hepatic, Cobra, or Simmons catheter (Cook Medical Technologies, Bloomington, IN, USA) or Gifu right bronchial catheter (Terumo Clinical Supply, Gifu, Japan). Microcatheters with a 2.0-Fr (Progreat; Terumo Medical Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) or 1.7-Fr (Veloute; Asahi Intecc, Aichi, Japan) or 1.68-Fr (Radiostar; TaeWoong Medical Co., Gimpo, Korea) tip were inserted additionally and advanced as far distal as possible to prevent complications.

The angiographic findings of ongoing bleeding from a vessel are as follows: petechial hemorrhage, a pseudoaneurysm, sudden cutoff of a vessel, and contrast extravasation. The petechial hemorrhage appears as tiny prolonged contrast spot, which means bleeding from a small artery. When the authors observed several of these findings at once from one classification of blood vessel in a patient, the most severe and dominant finding was selected as an angiographic finding of the vessel classification in the patient. And also, the authors did not add the number of injured vessels in a single classification of blood vessel in a patient. For an example, if a patient had vessel injuries at five intercostal, both internal mammary and one bronchial arteries, the recorded injured vessels are one intercostal, one internal mammary and one bronchial arteries. In summary, one angiographic finding was selected in each classification of bleeding vessel in a patient.

The choice of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) (Histoacryl; B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany), microcoils (Tornado; Cook Medical Technologies; or Concerto; ev3, Covidien Vascular Therapies, Irvine, CA, USA; or Interlock; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA), gelatin sponge particles (Cutanplast; Mascia Brunelli SPA, Milano, Italy; or EGgel; Engain Co., Ltd., Seongnam, Korea), and polyvinyl alcohol particles (Contour, Boston Scientific) was not standardized but left to the attending interventional radiologist's decision in the individual case.

TECHNICAL AND CLINICAL SUCCESS ASSESSMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

Technical success was defined as the cessation of bleeding on completion angiography. Clinical success was defined as the cessation of thoracic bleeding with no need to perform thoracotomy to achieve hemostasis. Complications were defined according to the Society for Interventional Radiology categories (12). Any complication that required extended hospitalization, an advanced level of care, or resulted in permanent adverse sequelae or death was considered to be a major complication, whereas all of the remaining ones were considered as minor complications.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We used descriptive statistics to describe the characteristics of our patient cohort and the outcomes. We presented normally distributed continuous data as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and non-normally distributed continuous data as the median with the range. All statistical analyses were performed with MedCalc Statistical Software for Windows, version 19 (MedCalc Software Ltd., Ostend, Belgium).

RESULTS

BASELINE PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 68 patients are described in Table 1. The mean age of patients was 58.2 ± 17.1 years, and the 82.4% were males. The most frequent injury mechanism was a fall from height. The initial median systolic blood pressure was 90 mm Hg, and the median heart rate was 97.5 beats per minute. The median initial hemoglobin was 8.95 g/dL (3.9–16.3), requiring a median of four units of blood transfusion with a wide range (0–38) during the first 24 hours. The median ISS was 25 with range (4–50), that the majority of patients suffered a major trauma. The average period of hospitalization was 49.0 days (SD, 62.4). The average time interval between the patients' emergency room visit and the TAE procedure was 490 minutes (SD, 1561).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Thoracic Injury (n = 68).

| Parameter | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.2 ± 17.1 | |

| Male/female, n (%) | 56/12 (82.4/17.6) | |

| Mechanism of injury, n (%) | ||

| Fall | 26 (38.2) | |

| Pedestrian traffic accident | 15 (22.1) | |

| Blunt force | 8 (11.8) | |

| Motor vehicle accident | 7 (10.3) | |

| Motorcycle accident | 6 (8.8) | |

| Slipping | 4 (5.9) | |

| Stabbing | 2 (2.9) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)* | 90 (40–190) | |

| Heart rate (beats per minute)* | 97.5 (60–203) | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL)* | 8.95 (3.9–16.3) | |

| 24-hour transfusion volume (units)* | 4 (0–38) | |

| Injury Severity Score* | 25 (4–50) | |

| Time interval from ER to TAE (minutes) | 490 ± 1561 | |

| Period of hospitalization (days) | 49.0 ± 62.4 | |

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation except where indicated otherwise.

*Value is the median with the full range in parenthesis.

ER = emergency room, TAE = transcatheter arterial embolization

CHARACTERISTICS OF EMBOLIZATION AND TECHNICAL OUTCOMES

The characteristics of the different TAE procedures performed are summarized in Table 2. We embolized 88 injured target arteries in 68 patients. The most common artery that was actively bleeding was the intercostal artery (n = 44) followed by the internal mammary artery (n = 26). The lateral thoracic, bronchial, superior thoracic, thoracoacromial, thyrocervical, and inferior phrenic arteries were only infrequently concerned. As embolic agents, gelatin sponge particles were used in 47.7% of patients, gelatin sponge particles with microcoils in 19.3%, and NBCA in 12.5%. All other combinations and polyvinyl alcohol particles were used less frequently.

Table 2. Data on Transcatheter Arterial Embolization in Patients (n = 68) with Hemothorax.

| Parameter | Intervention, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted injured artery | 88 | |

| Intercostal artery | 44 (50.0) | |

| Internal mammary artery | 26 (29.5) | |

| Lateral thoracic artery | 8 (9.1) | |

| Bronchial artery | 3 (3.4) | |

| Superior thoracic artery | 2 (2.3) | |

| Thoracoacromial artery | 2 (2.3) | |

| Thyrocervical artery | 2 (2.3) | |

| Inferior phrenic artery | 1 (1.1) | |

| Angiographic findings | ||

| Extravasation | 39 (44.3) | |

| Petechial hemorrhage | 33 (37.5) | |

| Pseudoaneurysm | 11 (12.5) | |

| Cutoff sign | 5 (5.7) | |

| Embolic agents | ||

| GS | 42 (47.7) | |

| GS + microcoils | 17 (19.3) | |

| NBCA | 11 (12.5) | |

| NBCA + GS | 6 (6.8) | |

| NBCA + GS + microcoils | 5 (5.7) | |

| Microcoils | 4 (4.5) | |

| Polyvinyl alcohol particles | 2 (2.3) | |

| Technical failure | 1 (1.1) | |

GS = gelatin sponge particles, NBCA = N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate

In one patient, it was impossible to catheterize the left superior thoracic artery, and the patient was recorded as a technical failure. We terminated the TAE procedure, and the patient underwent external compression of the left superior thoracic artery area. This resulted in hemostasis without any further problems. Consequently, the technical success rate of TAE with immediate cessation of bleeding was 98.5% in our patients (67/68).

DELAYED BLEEDING

Among the patients who had been technically successfully treated, four patients showed delayed active bleeding and/or increasing hematoma. They consequently underwent repeated TAE with success. The average time interval between the two TAE procedures was about 3.5 days. In two patients, the bleeding occurred on the same side of the thorax, where the first TAE had been performed. In the other two patients, bleeding recurred on the opposite side. All four patients had been confirmed to have multilevel intercostal artery injury during the first TAE. In one of the two patients with delayed bleeding on the same side, the bleeding occurred in the right 7th intercostal artery, where no clear findings of active bleeding had been established during the first TAE. In the other patient, delayed bleeding occured in the left 10th and 11th intercostal arteries, which had been embolized with gelatin sponge particles during the first TAE.

CLINICAL OUTCOMES AND COMPLICATIONS

The clinical success rate was 92.6% (63/68), with five patients having to undergo thoracotomy for hemostasis. Four of them had a severe thoracic injury with flail chest, and the fifth had bleeding from an intercostal artery above the level of the previously embolized intercostal artery.

We could not observe any major TAE-related complications, such as infarction or quadriplegia.

DISCUSSION

Several authors have reported the successful non-operative management of traumatic hemothorax with TAE. Whigham et al. (8) described a clinical success rate of 91.6% and Stampfl et al. (9) a rate of 78.9% based on our clinical success definition. In our patients, clinical success was achieved in 92.6%. The five patients with a clinical failure underwent thoracotomy for hemostasis after TAE. Thoracotomy was either performed for the internal fixation of rib fractures and hematoma removal during which bleeding was discovered, or to treat active bleeding found during the follow up CT or an increasing hematoma after TAE. Four of these patients had severe thoracic injuries, resulting in considerable lung laceration and contusion. In these patients, the main focus of bleeding was the pulmonary artery branch on the site of the laceration. Therefore, if thoracic trauma is severe with prominent lung parenchymal injury on the initial CT, the possibility of bleeding from the pulmonary artery branch should be considered in addition to bleeding from the systemic artery. The more severe the injury of the lung parenchyma, the more likely there is bleeding from the pulmonary artery, which may cause the clinical failure of TAE.

In the fifth patient with clinical failure, we had embolized the 9th intercostal artery on the left, and bleeding was observed from the left 8th intercostal artery during the thoracotomy two days after TAE. And there were two patients with clinical success who underwent repeated TAE because of delayed bleeding on the same side of the thorax, where the first TAE had been performed. So, it should be considered that delayed bleeding may occur after the first TAE, although no active bleeding was seen upon the completion of angiography, or embolization was performed at the site.

Additionally, based on the two patients in whom delayed bleeding occurred on the opposite side during repeated TAE, we recommend that thoracic aortography should principally be performed during the first TAE. Furthermore, the opposite hemithorax, which might have experienced a relatively minor trauma, should be as carefully examined as the side with the suspected bleeding.

The most frequently injured chest wall arteries are the intercostal arteries, which supply most of the chest wall, including its anterior and posterior parts. Their injury is the most important cause of hemothorax. The posterior intercostal arteries originate from the aorta, and the anterior intercostal arteries originate from the internal mammary artery and musculophrenic branches, forming anastomoses with each other during their course in each intercostal space (13).

As a consequence of the anatomical characteristics of the chest wall vessels, hemostasis can conveniently be achieved during the internal fixation of rib fractures. However, if there is no indication for emergency thoracotomy other than a massive hemothorax, or when emergency TAE of abdominal or pelvic arteries is needed, then the TAE for the hemothorax can also be considered. This also has the advantage of avoiding general anesthesia in critically ill patients.

In this study, there was a tendency to use gelatin sponge particles over NBCA or microcoils. The half of injured arteries were intercostal artery, and there were many cases of multiple intercostal artery injuries in a patient. The authors working at the regional trauma center considered the medical costs that burden the patient. The use of gelatin sponge particles is more cost-effective than using the detachable, pushable microcoils or NBCA with multiple microcatheters. Only one patient had delayed bleeding of occluded artery after arterial embolization with gelatin sponge particles.

When performing TAE of an intercostal artery, the blood supply to the spinal cord must first be confirmed by angiography. The spinal cord is supplied through spinal branches of the intercostal arteries at various levels. The artery of Adamkiewicz, the largest anterior medullary branch, supplies the lower two-thirds of the spinal cord and is in 74% found between T9 and T12 and in 15% between T5 and T8. In around 80% of people, it originates as a single artery from the left side of the aorta (14). During intercostal artery embolization, major complications such as paraplegia or quadriplegia can occur if embolic material enters the spinal branches, for example, the artery of Adamkiewicz. Therefore, the more reliable anatomy should be confirmed first by digital subtraction angiography using a power injector at the origin of the targeted intercostal artery (15). After that, TAE should be performed as far distally from the origin of the intercostal artery as possible, using a 1.7-Fr or 2.0-Fr microcatheter. With this precaution, we could not observe spinal complications in our patients.

The internal mammary artery originates from the first portion of the subclavian artery, from where it travels down the medial pleura. In the 6th intercostal space, it ends by branching into the superior epigastric and musculophrenic artery (16). During its course along the lateral side of the sternum, it can easily be injured by blunt trauma with sternal fractures or penetrating injuries around the sternum. The mediastinum and pericardium possess a rich collateral network with the internal mammary artery. As a consequence, injury to this artery may lead to a mediastinal hematoma, pericardial effusion and tamponade, or hemothorax. On the other hand, because the collateral supply to the chest wall and mediastinum is abundant, the possibility of tissue infarction is low, even with embolization of these blood vessels during treatment (8). Therefore, TAE may be particularly useful when hemothorax or hemomediastinum occurs in connection with injury to the parasternal or retrosternal area, even more so since these areas are relatively difficult to access surgically compared to other locations. There were 26 cases of bleeding from the internal mammary artery in this study, and TAE was performed without any complications.

During the TAEs performed at our center, bleeding from the superior thoracic, lateral thoracic, thoracoacromial, thyrocervical, or inferior phrenic artery was observed in 20.5% of targeted arteries (Fig. 1). These vessels are located in the superior, lateral, and inferior aspects of the thorax, respectively, supplementing the blood supply provided by the intercostal arteries. Only a few case reports of hemothorax caused by bleeding from these arteries exist (17,18,19), and these arteries are not necessarily initially suspected as a source of bleeding. However, if no clear bleeding is identified from the other arteries described above during angiography, bleeding from these arteries should be considered. On the other hand, if subclavian arteriography is routinely performed after embolization of other arteries in the thoracic area, and does not show any abnormalities, bleeding from these arteries can be excluded.

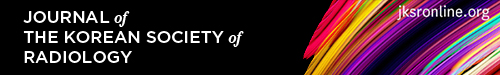

Fig. 1. An 80-year-old male presented with right chest pain after slipping.

A. Contrast-enhanced axial CT image shows multiple rib fractures, subcutaneous emphysema or hematoma with an inserted chest tube, and hemothorax in the right lung.

B. Right lateral thoracic arteriography shows multiple small pseudoaneurysms (arrows).

C. Right subclavian arteriography after embolization with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, microcoil, and gelatin sponge particle shows no active bleeding.

D. The 13-day follow-up axial CT image shows improvement in the hemothorax and the extent of subcutaneous emphysema or hematoma. Internal fixations were performed for multiple rib fractures. The treatment was clinically successful.

The sites of TAE described above are all concern arteries in the chest wall. However, three of our patients underwent TAE for bleeding from the bronchial artery, an intrathoracic systemic artery. The anatomy of the bronchial artery is very diverse but usually associated with arterial supply to the pulmonary artery, mediastinum, esophagus, and pericardium. The bronchial artery can arise either directly from the aorta or originate from the common intercostobronchial trunk. In more than 90% of people, it originates from the bottom of the ligamentum arteriosum at the level of the T5–6 vertebral bodies (14,20).

In this study, the bronchial artery was embolized with either gelatin sponge particles or polyvinyl alcohol particles as a permanent embolic material. The possibility of complications, such as bronchial stenosis or infarction, should be considered for embolization of the bronchial artery supplying the tracheobronchial tree. However, according to Woo et al. (21), no evidence of ischemic changes in any tissue, including the aorta, bronchus, and lung parenchyma, was found after embolization of the bronchial artery, even when NBCA, which has the lowest reperfusion rate after embolization, was used. In our study, we also did not observe any complications after bronchial artery embolization.

In bleeding from a bronchial artery, treatment is urgent because, unlike in thoracic wall artery bleeding, blood can be aspirated into the lung and cause hemoptysis or hypoxia. In this study, three patients underwent bronchial artery embolization, two of them with gelatin sponge particles after bleeding was confirmed in the initial emergency angiography. The third patient underwent thoracotomy for hemostasis. Intrathoracic bleeding was found on the initial CT. After thoracotomy, serial follow-up chest radiographs showed an increase in the opacity of the left lung. In addition, hemoptysis occurred, and bleeding was confirmed during bronchoscopy. Eventually, angiography was performed five days after the thoracotomy and demonstrated multiple small contrast extravasations of the bronchial artery (Fig. 2). The performance of TAE to treat bronchial artery bleeding after thoracotomy has the advantage that further surgery can be avoided. Moreover, the bronchial artery is more difficult to approach with a thoracotomy than the thoracic wall arteries, increasing the importance of TAE as an alternative. If a patient with thoracic trauma has some combinations of clues such as tracheobronchial injury on CT, massive hemoptysis, unexplained hypoxia and confirmed hemorrhage during bronchoscophy, then the bronchial artery angiography may help to identify suspected intrathoracic systemic arterial bleeding.

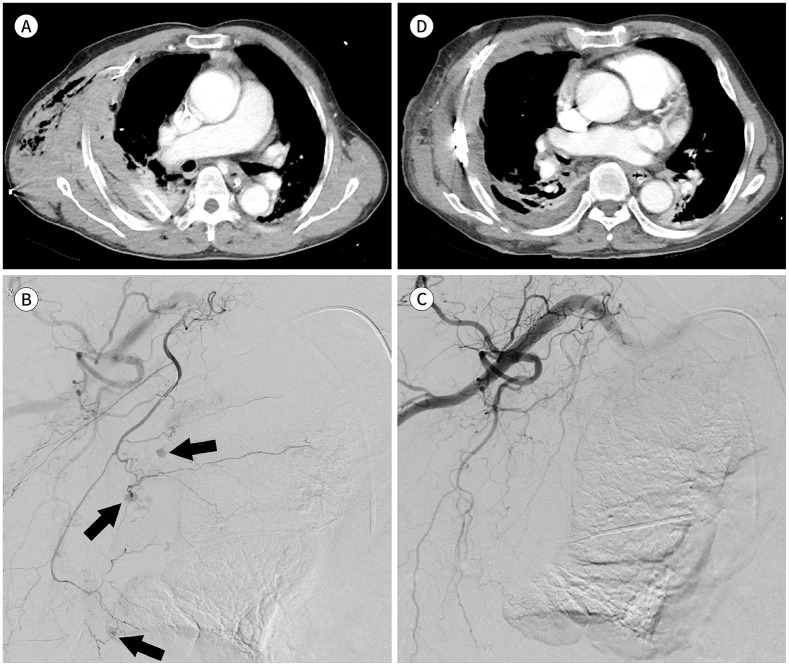

Fig. 2. A 65-year-old male presented with left chest pain after a pedestrian traffic accident.

A. Contrast-enhanced axial CT image shows contrast leakage (arrow) with a traumatic pseudocyst in the left lung.

B. Serial chest radiographs show increasing opacity of the left lung at one, two, three, and five days after thoracotomy for hemostasis.

C. Left bronchial arteriography shows multiple small contrast extravasations (arrows).

D. Arteriography after polyvinyl alcohol particle embolization shows no active bleeding.

E. The one-day follow-up axial CT image shows decreased hemothorax with a newly inserted chest tube and no contrast leakage.

F. The 44-day follow-up chest radiograph shows decreased opacity of the left lung than that in the preintervention image.

Our study has several limitations. The study is a non-randomized study of a patient group that has undergone TAE for traumatic hemothorax, and was investigated in a retrospective manner using clinical data. And next, every vessel classifications of bleeding artery in all patients were investigated, but the number of injured artery for each classification was not counted. And also, angiographic findings in each classification was limited to one most severe and dominant finding. Through this, it is possible to know the vessel classification that is the focus of bleeding, but it was difficult to understand the injury severity of each patient.

In conclusion, TAE to control thoracic wall and intrathoracic systemic arterial hemorrhage after thoracic trauma is a safe and minimally invasive procedure. TAE may be attempted when a patient has only a hemothorax without concomitant injuries requiring emergency surgery or undergoes emergency TAE for hemostasis of other internal injuries, e.g., in the abdomen.

Clinicians need to be aware that arterial bleeding after thoracic trauma may not only involve the intercostal arteries but also those that supply the superior, lateral, and inferior aspect of thoracic wall and the parasternal area. Performing angiography of an artery relevant to the trauma site based on the anatomy is recommended for successful TAE. Embolization of the bronchial artery may be considered when bleeding persists after thoracotomy has been performed for hemostasis.

Footnotes

- Conceptualization, J.C.H.

- data curation, L.C.M., J.C.H., L.R.

- formal analysis, L.C.M., J.C.H., B.M.

- investigation, L.C.M., J.C.H., L.R.

- methodology, L.C.M., J.C.H.

- validation, all authors.

- visualization, L.C.M., J.C.H.

- writing—original draft, L.C.M., J.C.H.

- writing—review & editing, all authors.

Conflicts of Interest: Chang Ho Jeon has been an Editorial Board Member of Journal of the Korean Society of Radiology since 2021; however, he was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. Otherwise, no other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Funding: This work was supported by clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital in 2020.

References

- 1.Manlulu AV, Lee TW, Thung KH, Wong R, Yim AP. Current indications and results of VATS in the evaluation and management of hemodynamically stable thoracic injuries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;25:1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson JD, Miller FB, Carrillo EH, Spain DA. Complex thoracic injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1996;76:725–748. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(05)70477-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mowery NT, Gunter OL, Collier BR, Diaz JJ, Jr, Haut E, Hildreth A, et al. Practice management guidelines for management of hemothorax and occult pneumothorax. J Trauma. 2011;70:510–518. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820b5c31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Padia SA, Ingraham CR, Moriarty JM, Wilkins LR, Bream PR, Jr, Tam AL, et al. Society of interventional radiology position statement on endovascular intervention for trauma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31:363–369.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2019.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chemelli AP, Thauerer M, Wiedermann F, Strasak A, Klocker J, Chemelli-Steingruber IE. Transcatheter arterial embolization for the management of iatrogenic and blunt traumatic intercostal artery injuries. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1505–1513. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagiwara A, Yanagawa Y, Kaneko N, Takasu A, Hatanaka K, Sakamoto T, et al. Indications for transcatheter arterial embolization in persistent hemothorax caused by blunt trauma. J Trauma. 2008;65:589–594. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318181d56a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husted JW, Stock JR, Manella WJ. Traumatic anterior mediastinal hemorrhage: control by internal mammary artery embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1982;5:268–270. doi: 10.1007/BF02565410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whigham CJ, Jr, Fisher RG, Goodman CJ, Dodds CA, Trinh CC. Traumatic injury of the internal mammary artery: embolization versus surgical and nonoperative management. Emerg Radiol. 2002;9:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s10140-002-0226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stampfl U, Sommer CM, Bellemann N, Kortes N, Gnutzmann D, Mokry T, et al. Emergency embolization for the treatment of acute hemorrhage from intercostal arteries. Emerg Radiol. 2014;21:565–570. doi: 10.1007/s10140-014-1231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagiwara A, Iwamoto S. Usefulness of transcatheter arterial embolization for intercostal arterial bleeding in a patient with burst fractures of the thoracic vertebrae. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:489–491. doi: 10.1007/s10140-008-0780-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Copes WS, Champion HR, Sacco WJ, Lawnick MM, Keast SL, Bain LW. The injury severity score revisited. J Trauma. 1988;28:69–77. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198801000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacks D, McClenny TE, Cardella JF, Lewis CA. Society of Interventional Radiology clinical practice guidelines. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2003;14:S199–S202. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000094584.83406.3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Clinically oriented anatomy. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. pp. 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown AC, Ray CE. Anterior spinal cord infarction following bronchial artery embolization. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2012;29:241–244. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown DB, Papadouris DC, Davis RV, Jr, Vedantham S, Pilgram TK. Power injection of microcatheters: an in vitro comparison. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:101–106. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000141718.12025.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McVay CB. Anson and McVay surgical anatomy. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Ltd; 1984. pp. 347–349. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pontell M, Scantling D, Babcock J, Trebelev A, Nunez A. Lateral thoracic artery pseudoaneurysm as a result of penetrating chest trauma. J Radiol Case Rep. 2017;11:14–19. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v11i1.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aoki M, Shibuya K, Kaneko M, Koizumi A, Murata M, Nakajima J, et al. Massive hemothorax due to inferior phrenic artery injury after blunt trauma. World J Emerg Surg. 2015;10:58. doi: 10.1186/s13017-015-0052-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamanashi K, Nakao S, Idoguchi K, Matsuoka T. A case of delayed hemothorax with an inferior phrenic artery injury detected and treated endovascularly. Clin Case Rep. 2015;3:660–663. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lopez JK, Lee HY. Bronchial artery embolization for treatment of life-threatening hemoptysis. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23:223–229. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-948759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo S, Yoon CJ, Chung JW, Kang SG, Jae HJ, Kim HC, et al. Bronchial artery embolization to control hemoptysis: comparison of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and polyvinyl alcohol particles. Radiology. 2013;269:594–602. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13130046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]