Abstract

파킨슨병은 중뇌 흑질에 위치한 도파민성 신경세포의 퇴행성 소실로 인해 발생하는 이상운동질환이다. 최근 다양한 자기공명영상기법의 발전으로 파킨슨병에서 일어나는 병리생태학적인 변화를 반영하는 여러 영상 소견들이 보고되었다. 여러 연구에서 이러한 영상 소견들은 파킨슨병의 진단 및 비정형 파킨슨증과의 감별 등에 유의미한 도움을 줄 수 있는 것이 밝혀졌다. 본 종설에서는, 파킨슨병에서 일어나는 흑질선조체 변성의 병태생리를 나타낼 수 있는 나이그로좀 영상 및 뉴로멜라닌 영상 등을 포함한 자기공명영상기법들과 각 영상에서 나타나는 소견에 대하여 자세히 다루었다.

Keywords: Parkinson Disease, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Substantia Nigra

Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a movement disorder that develops due to degenerative loss of dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra of the midbrain. Recent advances in MRI techniques have demonstrated various imaging findings that can reflect the underlying pathophysiological processes occurring in Parkinson’s disease. Many imaging studies have shown that such findings can assist in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and its differentiation from atypical parkinsonism. In this review, we present MRI techniques that can be used in clinical assessment, such as nigrosome imaging and neuromelanin imaging, and we provide the detailed imaging features of Parkinson’s disease reflecting nigrostriatal degeneration.

서론

파킨슨병(Parkinson’s disease)은 느린 움직임(bradykinesia), 강직(rigidity)과 안정시 떨림(resting tremor), 자세 불안정성(postural instability) 등을 특징으로 나타내는 이상운동 질환의 하나로, 알츠하이머병(Alzheimer’s disease)에 이어 흔하게 발생하는 퇴행성 신경질환(neurodegenerative disease)이다. 파킨슨병의 원인은 운동을 제어하는 역할을 하는 중뇌(midbrain)의 흑질(substantia nigra) 내에 위치하는 도파민성(dopaminergic) 신경세포의 퇴행성 변성 및 소실로, 대부분 특발성(idiopathic)으로 발병한다. 파킨슨병의 발병에는 알파-시누클레인(α-synuclein)이라는 신경세포 내 단백질의 축적 및 응집이 연관되어 있는 것으로 알려졌고, 이러한 알파-시누클레인 단백질의 응집은 특발성 파킨슨병(idiopathic Parkinson’s disease)을 포함하는 알파-시누클레인병증(α-synucleinopathy)이라고 불리는 다양한 퇴행성 신경질환과 연관되어 있는 것이 밝혀졌다.

한편, 파킨슨병과 유사한 증상을 나타내는 비정형 파킨슨증(atypical parkinsonism)은 파킨슨병 증상 이외에도 추가적인 증상들을 나타낼 수 있으며, 진행성핵상마비(progressive supranuclear palsy), 피질기저핵변성(corticobasal degeneration), 다계통위축(multiple system atrophy; 이하 MSA) 및 루이소체치매(dementia with Lewy bodies) 등이 이 질환군에 속한다. 파킨슨증은 이차적인 원인으로도 나타날 수 있으며, 대표적으로는 약물유발성 파킨슨증(drug-induced parkinsonism)과 혈관성 가성파킨슨증(vascular pseudo-parkinsonism) 등이 있다. 또한, 파킨슨병과 유사하게 떨림을 증상으로 보이는 대표적 질환으로는 본태성 떨림(essential tremor)이 있는데, 상기 이차성 파킨슨증과 유사 질환들에서는 중뇌 흑질의 도파민성 세포 변성 및 소실이 나타나지 않는 것으로 알려져, 특발성 파킨슨병과 그 병태생리학적인 원인에서 차이를 나타낸다.

이에 따라, 자기공명영상(이하 MRI)에서 중뇌 흑질의 병적인 변화를 나타내어 파킨슨병의 병태생리학적인 변화를 알아내고자 하는 많은 연구들이 이어지고 있다. 특히 영상기술의 발전에 따라 중뇌 흑질 변성을 알 수 있는 다양한 MRI 영상기법들이 등장하였고, 각 영상기법에 따른 특이적인 영상 소견들이 제시되었다. 이런 영상 소견들은 파킨슨병의 신경병적인 퇴행이 중뇌 흑질 영역에 어떠한 변화를 가져오는지 시각화할 수 있을 뿐만 아니라, 파킨슨병의 진단과 특발성 파킨슨병과 비정형 파킨슨증 혹은 이차성 파킨슨증을 감별하는 데에 도움을 주며, 나아가서는 파킨슨병의 진행 정도를 파악할 수 있게 해주는 것으로 알려졌다.

본 종설에서는 흑질선조체 변성(nigrostriatal degeneration)을 중심으로 파킨슨병 평가에 많이 사용되고 있는 MRI 기법들에 대해 서술하고, 특징적인 영상 소견들과 그와 연관된 병태생리 및 임상적 의의에 대해 기술하고자 한다.

파킨슨병 연관 신경학적 구조물

MRI는 다음과 같은 파킨슨병의 신경병리학적인 변화와 그와 관계된 구조물의 영상화를 가능하게 한다.

나이그로좀(Nigrosome) 소실

중뇌 흑질은 흑질치밀부(substantia nigra pars compacta)와 흑질망상부(substantia nigra pars reticulata)로 구성된다. 대부분의 도파민성 신경세포는 흑질치밀부 내에 위치하는데, 이 중 약 60%는 선조체흑질 구심성 섬유(striatonigral afferent fiber)가 풍부한 흑질기질(nigral matrix)에 있고, 나머지 40%는 선조체흑질 구심성 섬유가 드문 위치에 뭉쳐서 존재한다(1). 이렇게 도파민성 신경세포가 뭉쳐서 존재하는 구조물을 나이그로좀(nigrosome)으로 명명하며, 5개의 세부구조물(나이그로좀 1–5)이 큰 3차원적 구조물을 형성한다(1). 파킨슨병에서 흑질선조체 신경경로(nigrostriatal pathway)의 변성에 따르는 도파민성 세포의 소실은 주로 나이그로좀에서 일어나는 것으로 밝혀졌으며, 특히 나이그로좀 구조물 중 가장 큰 부피를 차지하는 나이그로좀-1에서부터 변화가 시작하는 것으로 알려졌다(2).

뉴로멜라닌(Neuromelanin) 탈침착

뉴로멜라닌(neuromelanin)은 카테콜라민(catecholamine) 합성 과정에서 만들어지는 단백질 중합체이다. 뉴로멜라닌의 생성은 도파민성 신경경로 및 노르아드레날린성(noradrenergic) 신경 경로에서 일어나며, 이에 따라 주로 중뇌 흑질치밀부 및 청반(locus coeruleus)에 위치한다(3). 따라서, 파킨슨병의 도파민성 신경세포의 소실은 뉴로멜라닌을 포함하는 신경세포의 감소를 가져오며, 이런 현상은 MRI에서 흑질과 청반에서의 뉴로멜라닌의 탈침착(depigmentation)을 나타낼 수 있다(4).

철(Iron) 침착

뇌조직 내 철(iron)은 90% 이상 페리틴(ferritin)의 형태로 존재한다. 뇌내 철은 정상적으로 기저핵(basal ganglia) 및 중뇌 흑질 등에 침착되어 있으며, 노화에 따라 철 침착이 증가하는 것으로 알려져 있다(5). 파킨슨병에서는 비정상적인 철 대사과정이 동반되는데, 도파민성 신경세포는 이런 과정에 취약하여 이로 인해 사멸이 촉진된다. 따라서 파킨슨병 환자들은 흑질치밀부에 비정상적인 철 침착을 나타낼 수 있다(6).

백질(White Matter) 변성

혈관성으로 생기는 뇌내 백질(white matter)의 허혈성 병변이 파킨슨병에서의 이상운동 및 인지기능장애 등과 같은 증상과 연관될 수 있다는 연구들이 보고되었다(7). 또한 허혈성 백질 병변 이외에도 흑질선조체 신경경로를 이루는 도파민성 신경세포 축삭의 미세구조 변화와 변성, 이에 따른 신경망(neural network)의 비정상적 단절이 생길 수 있다(8). 이렇게 변성된 백질 내에는 유리수(free water; 이하 FW)의 양이 많아지는데, 이런 현상은 MRI를 통해 측정이 가능하며 파킨슨병에서도 변성으로 인한 소견이 나타나게 된다.

파킨슨병의 MRI 기법

파킨슨병을 평가하는 나이그로좀 영상, 뉴로멜라닌 영상, 철-민감 영상(iron-sensitive MRI) 및 확산텐서영상(diffusion tensor imaging; 이하 DTI)을 설명하고, 특히 1) 파킨슨병 진단을 위한 흑질선조체 변성 유무의 판단, 2) 증상의 중등도 및 질병 진행과의 연관성, 3) 비정형 파킨슨증과의 감별, 그리고 4) 파킨슨병 전구단계에서의 질병전환(phenoconversion) 예측에 있어 각 영상의 장단점을 기술하고자 한다.

나이그로좀 영상

고해상도 MRI를 이용하면 중뇌 흑질 내 나이그로좀 구조물을 시각적으로 확인할 수 있다. 나이그로좀은 흑질치밀부에 위치하고, 주변의 흑질망상부 및 적핵(red nucleus)에 비해 정상적인 철 침착이 적다. 이런 성질을 이용하여, T2*-weighted gradient-recalled echo (GRE) 영상 및 자화율 강조영상(susceptibility-weighted imaging; 이하 SWI)에서 나이그로좀 구조물의 정상적인 소견을 시각화한 다양한 연구들이 보고되었다(9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16). 특히 SWI의 발전으로 3T MRI에서 나이그로좀을 평가할 수 있게 되어, 실제 임상적인 영역에서 파킨슨병의 평가를 위한 사용이 가능해졌다. 최근에는 SWI에서 일반적으로 사용하는 highpass filtering된 위상정보(phase) 대신, 위상정보로부터 복원한 quantitative susceptibility mapping (이하 QSM) 영상을 정합하는 후처리 기법이 개발되어, 인공물이 적고 영상 왜곡이 적은 susceptibility-map weighted imaging (이하 SMWI) 영상을 얻는 것도 가능하다(17).

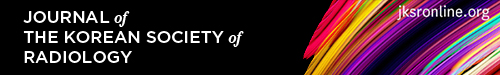

정상적인 나이그로좀-1은 적핵의 아래 1/3 레벨에 해당하는 부위에서 저신호강도의 흑질 내측(medial)에 고신호강도의 함입된 지점(indentation)으로 보인다. 좀 더 미측(caudal)의 레벨에서는 두 겹의 흑질 저신호강도 사이에서 길쭉한 고신호강도로 보여, 특징적인 3층(trilaminar)의 모습을 나타낸다(Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Normal appearance of nigrosome 1 (A-D), from cranial to caudal. 3T susceptibility-weighted imaging of a 52-year-old healthy male shows nigrosome 1 (arrows) as a focal indentation at the lower red nucleus level and as a linear hyperintensity between two layers of the substantia nigral hypointensity at the more caudal level.

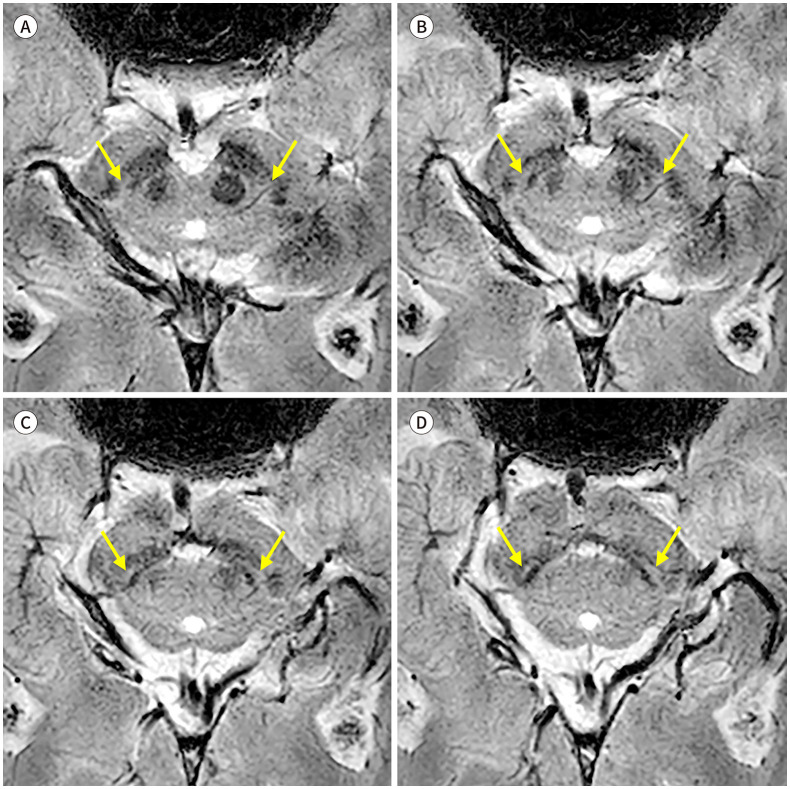

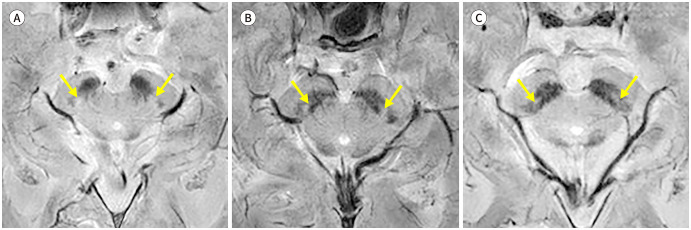

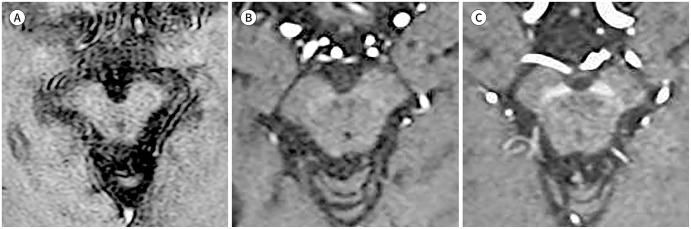

파킨슨병에서는 도파민성 신경세포의 소실과 이에 따른 철 침착으로, 정상적인 나이그로좀의 고신호강도가 소실된다(Fig. 2A). 7T의 고자장 영상은 나이그로좀-1에서 시작하여 -2, -4, -3, -5의 순서로 진행하는 나이그로좀의 신호 소실을 나타낸다(18). 3T SWI에서 해당 구조물을 모두 검출하는 것은 어려울 수 있으나, 나이그로좀-1과 -4는 확인이 가능하고, 실제로 3T SMWI를 이용한 한 연구에서 나이그로좀-1의 신호 소실에 뒤이어 -4의 소실이 진행됨을 확인하였다(Fig. 2B) (19). 많은 연구에서 나이그로좀의 신호 소실은 파킨슨병의 진단에 높은 성능을 나타낸다는 것을 보고하였고, 최근 발표된 메타분석(meta-analysis)에 따르면 종합적으로 92%의 민감도와 90%의 특이도가 확인되었다(20). 파킨슨병에서의 나이그로좀 신호 소실은 임상 증상과 연관성을 보여서(14) 파킨슨병의 특징인 비대칭적인 운동 증상과 부합하는 비대칭적인 나이그로좀 신호 소실을 나타낸다(Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Nigrosome imaging in Parkinson’s disease.

A. 3T SWI from a 65-year-old male patient diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease shows loss of nigral hyperintensity created by the nigrosome 1.

B. An 85-year-old female patient shows bilateral loss of nigrosome 1 hyperintensity upon susceptibility-map weighted imaging, but the hyperintense presumed nigrosome 4 (arrows) at the level of the lower red nucleus that is medial to the nigrosome 1 can be identified.

C, D. 3T SWI from a 75-year-old female patient shows intact nigral hyperintensity in the right side (arrow) and loss of nigral hyperintensity in the left side, which is correlated with her unilateral right-side motor symptom. Her 123I-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-N-(3-fluoropropyl)-nortropane single photon emission computed tomography (123I-FP-CIT SPECT) shows the corresponding asymmetric dopamine transporter uptake in the left striatum.

SWI = susceptibility-weighted imaging

전통적으로 파킨슨병에서 도파민성 신경경로의 시냅스전(presynaptic) 도파민 운반체(dopamine transporter) 영상이 사용되어 왔고, 특히 123I-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-N-(3-fluoropropyl)-nortropane (123I-FP-CIT)와 같은 방사성 리간드를 사용하는 단일광자방출단층촬영(single photon emission computed tomography; 이하 SPECT) 영상이 널리 이용되었다(21). 이런 가운데 나이그로좀 영상은 도파민성 신경세포의 유지 여부를 MRI로 알 수 있게 하여, 실제 진료환경에서 큰 역할이 기대되는 바이다. 특히 일부 연구에서는 파킨슨병에서 나타나는 123I-FP-CIT SPECT에서의 도파민 운반체 흡수율의 감소와 MRI의 나이그로좀 신호 소실이 연관된다고 보고되었다(Fig. 2D) (14). 추가 연구를 통해 두 영상 검사에서 나타나는 비정상 소견의 시간적인 선후 관계를 밝혀내는 것이 필요하겠다.

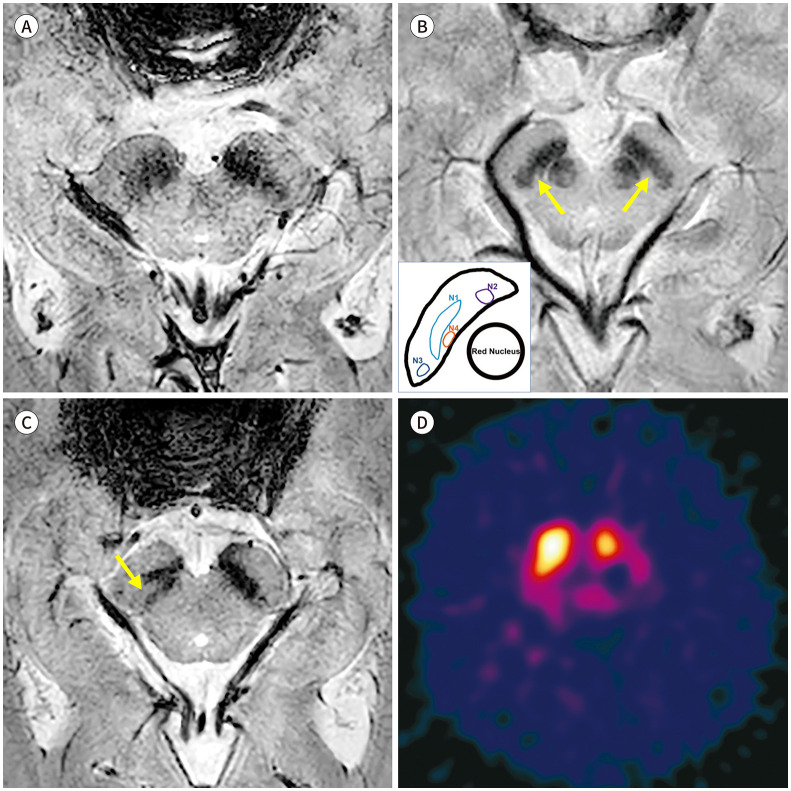

비정형 파킨슨증에서도 나이그로좀의 신호 소실이 있다. 진행성핵상마비에서 3T SWI를 시행한 연구에서 특발성 파킨슨병에서와 유사한 나이그로좀의 신호 소실을 보고하였다(Fig. 3A) (14). 다계통위축의 경우 선조체를 침범하며 파킨슨 증상을 주로 나타내는 MSA with predominant parkinsonism (이하 MSA-P)에서는 특발성 파킨슨병에서와 마찬가지로 나이그로좀의 신호 소실이 두드러지나(Fig. 3B), 소뇌 증상이 두드러지는 MSA with predominant cerebellar ataxia (이하 MSA-C)에서는 흑질선조체 신경경로의 침범 여부에 따라 나이그로좀 신호가 유지되기도 하고 소실되기도 한다(Fig. 3C, D) (14,16). 한편 본태성 떨림, 약물유발성 파킨슨증 및 혈관성 가성파킨슨증과 같이 선조체 혹은 흑질선조체 신경경로를 침범하지 않는 이상운동질환의 경우, 3T SWI에서 나이그로좀의 고신호강도가 유지되는 것이 밝혀졌다(Fig. 4) (22,23,24). 이에 나이그로좀 영상을 이용하여 상기 질환들과 파킨슨병을 높은 진단능으로 감별할 수 있겠다(Table 1).

Fig. 3. Nigrosome imaging in atypical parkinsonism.

A. SMWI from a 67-year-old male patient diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy shows bilateral loss of the nigrosome 1 hyperintensity.

B. SMWI from a 61-year-old male patient diagnosed with MSA with predominant parkinsonism also shows bilateral loss of the nigrosome 1 hyperintensity.

C. A 62-year-old male patient diagnosed with MSA-C shows intact bilateral nigrosome 1 hyperintensity (arrows) upon SMWI.

D. On the other hand, a 68-year-old male patient diagnosed with MSA-C shows loss of bilateral nigrosome 1 hyperintensity.

MSA = multiple system atrophy, MSA-C = MSA with predominant cerebellar ataxia, SMWI = susceptibility-map weighted imaging

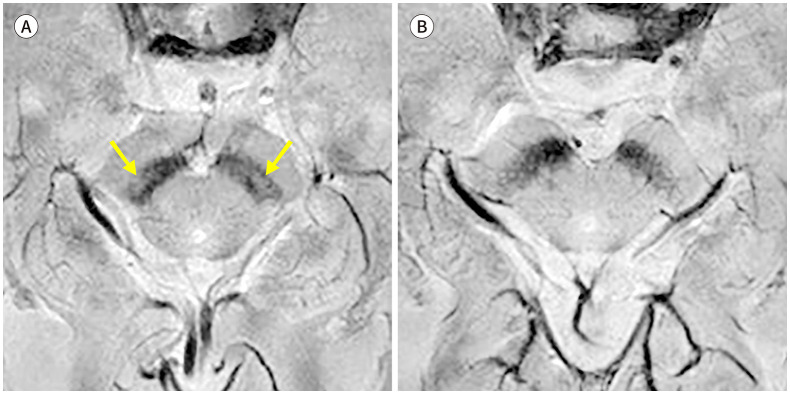

Fig. 4. Nigrosome imaging in other movement disorders.

A-C. Susceptibility-map weighted imaging from (A) a 72-year-old female patient with essential tremor, (B) a 58-year-old female patient diagnosed with drug-induced parkinsonism, and (C) a 73-year-old female patient diagnosed with vascular pseudo-parkinsonism all show intact bilateral hyperintensity of the nigrosome 1 (arrows).

Table 1. Summary of MR Imaging Findings in Parkinson’s Disease and Other Parkinsonian Syndromes.

| Disease | Nigrosome Imaging | Neuromelanin Imaging | Iron-Sensitive MRI | Diffusion Tensor Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPD | Loss of nigral hyperintensity | Decreased signal and area of neuromelanin-rich SN | Increased iron deposition in the SN and striatum | Decreased FA and/or increased MD in the SN Increased FW in the SN |

| PSP | Loss of nigral hyperintensity | Decreased signal and area of neuromelanin-rich SN | Prominent iron deposition in the SN and red nucleus | Decreased FA in the midbrain including SN Increased FW in the SN |

| MSA-P | Loss of nigral hyperintensity | Decreased signal and area of neuromelanin-rich SN | Prominent iron deposition in the putamen | Decreased FA in the SN, caudate nucleus, and putamen Increased FW in the SN |

| MSA-C | Nigral signal, either intact or lost | Needing further studies | Increased iron deposition in dentate nuclei | Decreased FA in the cerebellum |

| iRBD | Nigral signal, either intact or lost | Neuromelanin-area, either normal or decreased | Increased iron deposition in the SN in some patients | Possible decrease in the FA in the SN Increased FW in the SN |

| Other movement disorders* | Intact nigral hyperintensity | Intact neuromelanin-rich signal and area | Increased iron deposition in the SN and globus pallidus in ET | |

*Other movement disorders denote conditions which do not damage nigral dopaminergic neurons, such as ET, drug-induced parkinsonism, and vascular pseudoparkinsonism.

ET = essential tremor, FA = fractional anisotropy, FW = free-water, IPD = idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, iRBD = isolated rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder, MD = mean diffusivity, MSA-C = multiple system atrophy with predominant cerebellar ataxia, MSA-P = multiple system atrophy with predominant parkinsonism, PSP = progressive supranuclear palsy, SN = substantia nigra

나이그로좀 영상은 파킨슨병의 전구단계 질환에서도 유용하게 임상 적용할 수 있다. 고립성 렘수면행동장애(isolated rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder; 이하 iRBD)는 추후 파킨슨병, 다계통위축, 루이소체치매 등 알파시누클레인병증으로 진행하는 전구단계로 알려진 질환이다. 나이그로좀의 정상신호강도의 소실은 파킨슨병이 발병하기 전 전구질환단계에서부터 나타날 수 있는 것으로 알려졌다(Table 1, Fig. 5) (25,26). 이러한 나이그로좀의 신호 소실은 도파민 운반체 영상에서 보이는 흑질선조체 변성과 연관되어 나타났고, 이에 나이그로좀 신호가 정상인 전구질환 환자보다 나이그로좀 신호가 소실된 전구질환 환자에서 파킨슨병으로의 질병전환(phenoconversion)의 위험이 높을 가능성이 제시되었다(26). 역시 추후 대단위 코호트 연구가 필요하며 나이그로좀 영상의 넓은 임상 적용 가능성이 기대되는 결과이다.

Fig. 5. Nigrosome imaging in iRBD.

A. Nigrosome 1 hyperintensity (arrows) is preserved in a 74-year-old female patient diagnosed with iRBD.

B. On the other hand, nigrosome 1 hyperintensity is lost bilaterally in another 82-year-old male patient with iRBD.

iRBD = isolated rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder

뉴로멜라닌 영상

뉴로멜라닌은 철과 결합하여 상자성(paramagnetic)의 성질을 가진다. 상자성을 띠는 멜라닌 침착(pigmentation)은 T1-감소(shortening) 효과를 가져올 수 있으므로, T1-강조영상(T1-weighted imaging)에서 신호강도가 증가되어 보일 수 있다. 뉴로멜라닌 영상은 이와 같은 T1-감소 효과를 증대시킨 3T 고해상도 T1강조영상을 기반으로 얻어지며, 멜라닌 침착을 포함하지 않은 주변 조직을 포화(saturation)시켜 신호를 나오지 않게 하는 자기화전달파(magnetic transfer pulse)를 함께 사용하면 신호간 대조도를 높여서 뉴로멜라닌-포함 영역을 효과적으로 영상화할 수 있다(27).

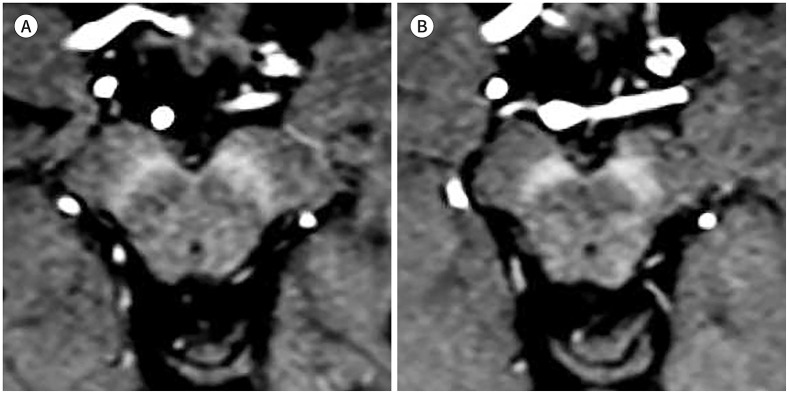

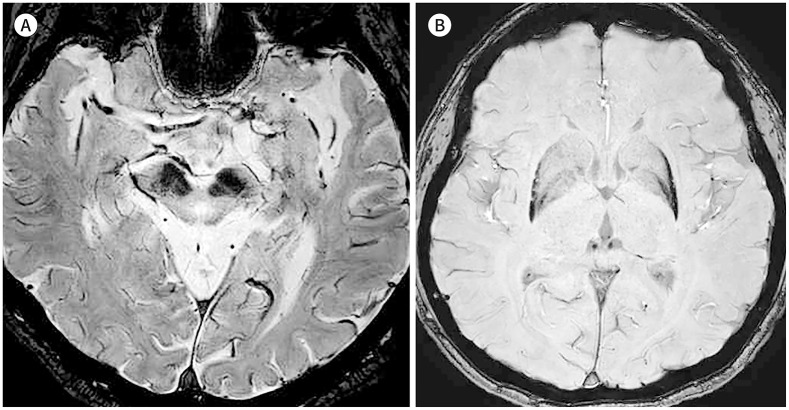

정상인의 뉴로멜라닌 영상에서는 뉴로멜라닌을 많이 포함하는 흑질치밀부의 신호강도가 증가되어 보이고, 주변 흑질망상부는 낮은 신호강도로 보인다(Fig. 6) (28). 자기화전달파를 사용한 고해상도 MRI에서는 청반 영역의 뉴로멜라닌 침착까지도 고신호강도로 확인할 수 있는 것으로 알려져 있다(29).

Fig. 6. Normal appearance of the neuromelanin-high signal area in the substantia nigra (A, B, from cranial to caudal).

3T neuromelanin imaging of a 78-year-old female without parkinsonism shows a T1-high signal neuromelanin-rich area in the substantia nigra.

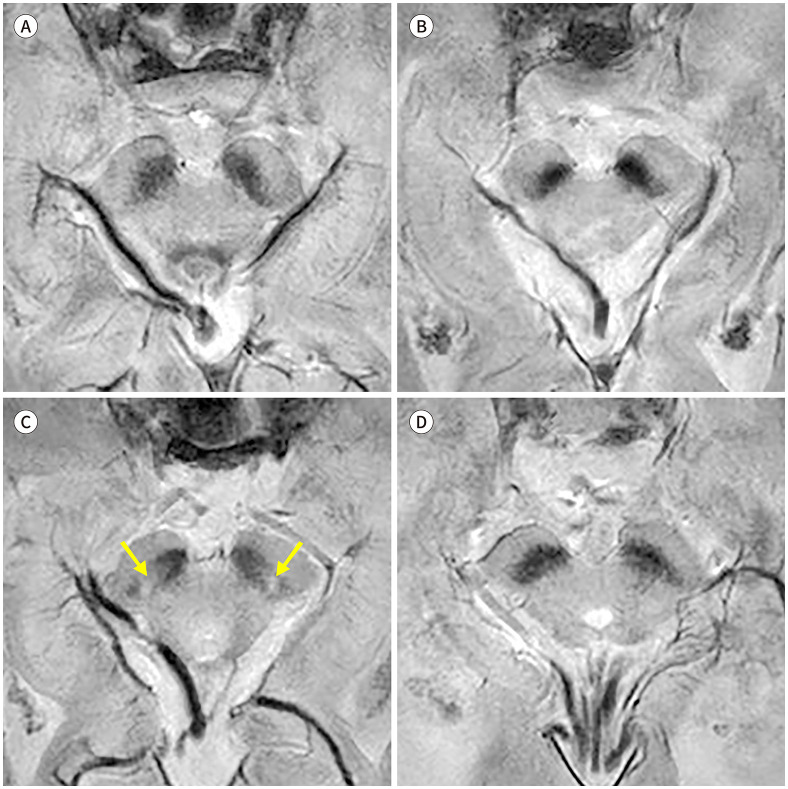

파킨슨병에서는 흑질치밀부의 도파민성 세포의 사멸과 청반의 세포 사멸에 따라 뉴로멜라닌이 감소하고, 이에 중뇌 흑질 및 청반에서 보이는 특징적인 T1-고신호강도 영역의 크기가 감소하며 그 신호강도의 정도도 감소한다(Fig. 7A) (30). 뉴로멜라닌 영역의 크기 감소는 파킨슨병의 기간이 오래될수록 진행하는 것으로 알려져 있고, 질병의 심각도와도 관련이 있어 파킨슨병의 임상적인 지표인 Hoehn and Yahr 단계(stage)가 높을수록 영역의 감소가 큰 것으로 밝혀졌다(Fig. 7B) (28,31). 따라서 뉴로멜라닌 신호강도의 소실은 파킨슨병의 진단을 위하여 사용될 수 있다. 최근 수행된 한 메타분석에서 뉴로멜라닌의 진단능은 89%의 민감도 및 83%의 특이도를 나타내는 것으로 보고되었고, 특히 파킨슨병의 기간이 오래될수록 진단능이 높았으며, 뉴로멜라닌의 고신호강도 영역의 전체 부피 변화를 이용하여 진단하는 것이 신호강도를 측정하여 진단하는 것보다 수행 능력이 높았다(30). 중뇌 흑질에서의 뉴로멜라닌 신호의 소실은 파킨슨병의 임상 증상을 평가하는 Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale part III (이하 UPDRS-III) 점수와 유의한 상관관계를 나타내며, 나이그로좀 신호 소실과 마찬가지로 비대칭적인 이상운동 증상이 있을 때 연관된 방향성을 보이면서 나타나는 것으로 알려졌다(32). 따라서 파킨슨병의 임상적인 평가에 뉴로멜라닌 영상이 유의미한 기여를 할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다.

Fig. 7. Neuromelanin imaging in Parkinson’s disease.

A. An 82-year-old male patient diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease shows a lower signal and area of the T1-high signal neuromelanin-rich area in the bilateral substantia nigra compared to the control subject (Fig. 6). His symptom duration was 1 year.

B. Another 67-year-old male patient diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease with a longer symptom duration of 5 years also shows a bilaterally decreased neuromelanin-rich area with a weaker signal than the patient described in (A).

뉴로멜라닌 영상과 123I-FP-CIT SPECT와 같은 도파민 운반체 영상의 상관관계가 잘 정립되어 있다. 뉴로멜라닌 영상과 도파민 운반체 영상은 각각 흑질치밀부의 도파민성 신경세포 내의 뉴로멜라닌 및 선조체의 도파민성 신경세포 축삭종말단의 기능을 반영하므로, 흑질선조체 변성이 일어나는 파킨슨병에서 두 영상지표가 연관되어 변화될 것으로 예상된다. 실제로 여러 연구에서 중뇌 흑질치밀부의 고신호강도 영역의 크기 및 신호대비도가 도파민 운반체 흡수율과 유의한 양의 상관관계(positive correlation)를 가지는 것이 나타났다(33,34). 다만 선조체의 도파민 운반체 흡수율 감소는 질병 초기부터 나타나는 반면, 실제 중뇌 흑질의 도파민성 신경세포 변성은 질병의 진행과 함께 뚜렷해진다고 알려져, 파킨슨병의 초기 진단 및 평가에는 선조체 대상의 도파민 운반체 영상이 유리하고, 진행된 파킨슨병의 평가에는 뉴로멜라닌 영상이 유리할 수 있겠다(34). 실제로 한 연구에서 운동동요(motor fluctuation)가 있는 파킨슨병 환자에서는 운동동요가 없는 환자에 비해 흑질치밀부의 뉴로멜라닌 고신호강도 영역의 크기는 의미 있게 감소하였지만, 선조체의 도파민 운반체 흡수율에는 큰 차이가 없음이 보고되었다(34). 따라서 상기 두 영상 검사의 상호 보완적인 사용이 필요할 것으로 보인다.

비정형 파킨슨증에서도 중뇌 흑질에서 뉴로멜라닌 고신호강도의 소실이 일어날 수 있다(Table 1). 진행성핵상마비와 다계통위축, 특히 MSA-P에서 모두 흑질치밀부의 뉴로멜라닌 고신호영역의 신호강도 및 크기 감소가 일어난다고 알려져 있다(Fig. 8A, B) (35,36). 반면 흑질선조체 변성을 동반하지 않는 본태성 떨림의 뉴로멜라닌 영상에서는 정상인과 비교하였을 때 유의미한 흑질 내 뉴로멜라닌의 변화가 보이지 않았다(Fig. 8C) (37).

Fig. 8. Neuromelanin imaging in atypical parkinsonism and other movement disorders.

A. A 77-year-old male patient diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy shows a marked decrease in the neuromelanin-rich signal in the bilateral substantia nigra. Note the atrophy in the midbrain and severe motion artifact.

B. A 69-year-old male patient diagnosed with multiple system atrophy with predominant parkinsonism also shows decreased signal and area of the neuromelanin-rich region in both sides.

C. On the other hand, neuromelanin imaging of a 73-year-old male patient diagnosed with essential tremor demonstrates relatively well-preserved neuromelanin-rich areas.

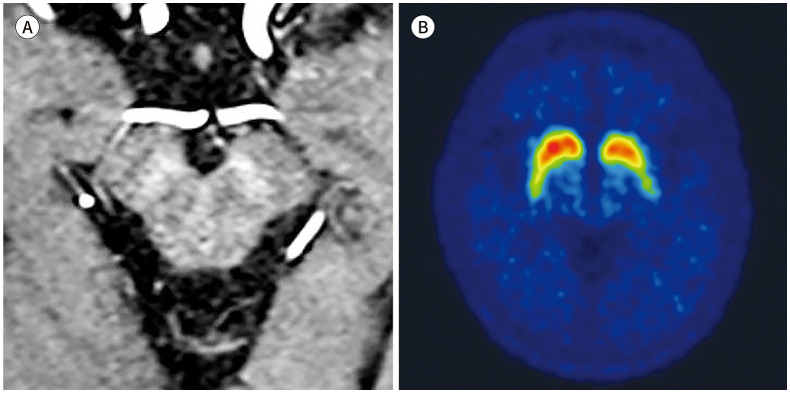

파킨슨병의 전구질환인 iRBD에서도 중뇌 흑질 내 뉴로멜라닌 고신호강도의 소실이 보고되었다(Table 1, Fig. 9) (38). 최근 발표된 딥러닝(deep learning) 기법을 이용하여 흑질치밀부의 뉴로멜라닌 고신호강도를 자동분할(automated segmentation)한 논문에 따르면, 정상인에 비해 전구질환 환자에서 뉴로멜라닌 신호강도 및 영역의 부피가 감소하였고 그 정도가 파킨슨병 환자에 비해서는 약하여, 전구질환에서의 뉴로멜라닌 신호 소실은 정상과 파킨슨병의 중간 정도임이 제시되었다(38). 이 결과는 크게 두 가지 임상적인 의의를 제시할 수 있는데, 첫째, 중뇌 흑질의 뉴로멜라닌 고신호강도 분석에 딥러닝 기법의 자동분할 방법을 적용할 수 있다는 점과, 둘째, 뉴로멜라닌 영역의 평가는 전구질환과 파킨슨병의 발병에 있어 질병 진행과 연관되는 정량적 평가를 제시할 수 있다는 점이다.

Fig. 9. Neuromelanin imaging in iRBD.

A, B. Neuromelanin imaging (A) and 18F-FP-CIT PET (B) of a 76-year-old male patient diagnosed with iRBD show a decreased neuromelanin signal in the left side, possibly correlated with dopamine transporter uptake upon PET.

iRBD = isolated rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder

철-민감 영상

파킨슨병에서 흑질 및 선조체에 비정상적으로 침착되는 철은 다양한 방법의 철-민감 영상으로 검출하거나 정량화할 수 있다. 뇌조직 내 철이 침착되면 자화감수성(susceptibility)이 변화하여 조직의 T2 혹은 T2* 이완(relaxation) 시간이 단축되고, 이는 R2 혹은 R2*를 측정하거나 위상(phase) 값을 이용한 정량화 자화감수성 영상(QSM)을 통해 측정할 수 있다. 철 이외의 칼슘, 지방 등과 같은 상자성 물질에 영향을 받을 수 있는 R2 혹은 R2* mapping 기법에 비해, QSM은 철 침착에 의한 자화감수성의 변화를 가장 민감하게 정량화할 수 있는 영상 기법으로 받아들여지고 있다(39).

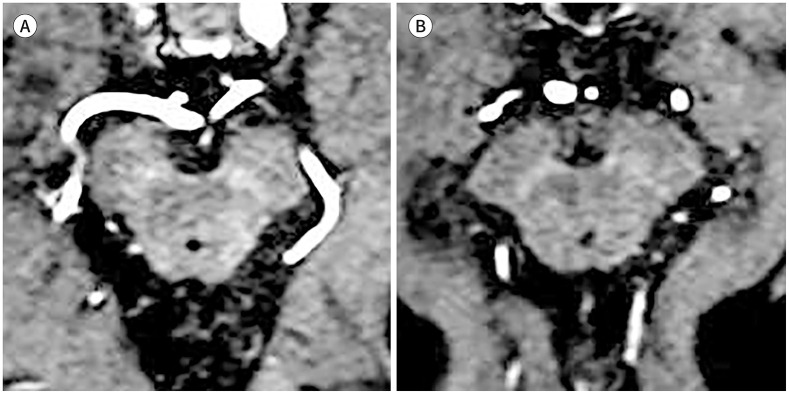

파킨슨병에서 중뇌 흑질치밀부와 선조체에 침착한 철의 양은 질병 중증도를 나타내는 UPDRS-III 점수와 연관되는 것으로 알려졌다(40). 흑질에서 측정한 R2* 값은 정상인과 비교하여 파킨슨병 환자에서 높게 나타나고, R2* 값이 파킨슨병의 질병 진행 정도를 반영할 수 있다(41). 특히 보행동결(freezing of gait)이 이른 시기에 나타나는 파킨슨병 환자의 경우 R2* 값의 변화 폭이 더 크다는 보고도 있어(42), R2* 값과 파킨슨병의 임상 증상과의 연관성을 더욱 시사하였다. QSM으로 자화율값(susceptibility value)을 측정하였을 때에도 비슷한 결과가 보고되었고(Fig. 10), 특히 R2*를 사용했을 때보다 QSM을 사용했을 때 파킨슨병의 진단능이 높았다(43). 이런 자화율의 변화는 파킨슨병의 초기부터 나타났고, 떨림 및 강직의 증상 정도와 유의한 연관성을 보였다(44). 특히 질병기간과 레보도파(levodopa) 사용량과도 유의하게 연관됨이 밝혀져(45), QSM 영상을 이용한 파킨슨병 평가의 임상적인 유용성을 시사한다.

Fig. 10. QSM in Parkinson’s disease.

A, B. Representative cases of QSM in a (A) 70-year-old female without parkinsonism and (B) 69-year-old male patient diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease are shown. The measured QSM values in the substantia nigra pars compacta were 73 ppb versus 116 ppb.

QSM = quantitative susceptibility mapping

흑질 및 선조체의 자화율값과 123I-FP-CIT SPECT의 연관성에 대한 한 연구에 따르면, 선조체에서 측정한 자화율값은 선조체의 도파민 운반체 흡수율과 유의한 연관성을 보이지만, 중뇌 흑질에서 측정한 자화율값은 선조체의 도파민 운반체 흡수율과 연관성이 발견되지 않았다(46). 이에 대해서는 추가적인 연구가 필요할 것으로 보인다.

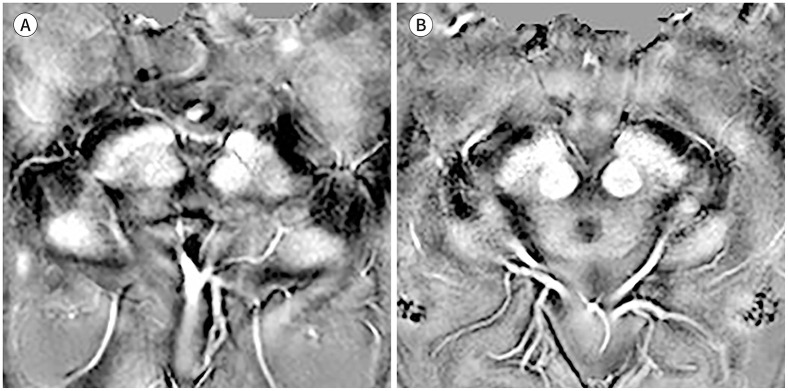

비정형 파킨슨증인 진행성핵상마비와 다계통위축의 경우, 중뇌 흑질뿐만 아니라 여러 부위에서 뚜렷한 철 침착을 보인다(47). 진행성핵상마비에서는 파킨슨병이나 MSA-P에서보다 중뇌 흑질 및 적핵의 철 침착이 두드러지고(48), MSA-P의 경우에는 주로 선조체 조가비핵(putamen)의 철 침착이 뚜렷하게 보이는 것으로 알려졌다(Table 1, Fig. 11). 하지만 파킨슨병과 다계통위축을 비교할 때 중뇌 흑질에서 QSM으로 측정한 자화율값에 큰 차이가 없다는 연구 결과가 발표되었다(49). 한편 흑질선조체 변성을 동반하지 않는 본태성 떨림 환자에서도 정상인에 비해 중뇌 흑질 및 창백핵(globus pallidus)에 철 침착이 증가한다는 연구도 있었다(50). 따라서 비록 철-민감 영상이 파킨슨병의 병태생리를 반영해 감별 진단에 도움을 줄 수도 있겠으나, 나이 등 철 대사에 영향을 끼칠 만한 여러 임상 요인들의 영향을 받을 수 있으므로, 관련 요인들을 모두 고려한 종합적인 평가가 필요하겠다.

Fig. 11. Pattern of iron deposition in atypical parkinsonism.

A. A 77-year-old male patient diagnosed with progressive supranuclear palsy shows prominent iron deposition in the bilateral substantia nigra and red nucleus. Note the markedly decreased distance between the red nucleus and substantia nigra.

B. A 50-year-old female patient diagnosed with multiple system atrophy with predominant parkinsonism shows characteristic atrophy of the bilateral posterior putamen with prominent iron deposition.

나이그로좀 영상이나 뉴로멜라닌 영상에 비해, 파킨슨병 전구질환에서 철 침착의 정도를 파악한 연구의 수는 적다. 하지만 파킨슨병 발병 전 i RBD 환자에서 중뇌 흑질의 철 침착 정도가 증가했다는 보고가 있어(51) 전구단계에서부터 흑질 도파민 신경세포의 변성과 함께 철 침착이 늘어날 수 있음을 시사하였다(Table 1).

확산텐서영상

확산텐서영상은 조직 내 물 분자의 운동을 측정할 수 있는 영상 기법으로, 뇌내 백질의 상태에 대한 정량화를 가능하게 한다. 확산텐서영상에서 측정할 수 있는 값들 중 많이 사용되는 것은 분할비등방도(fractional anisotropy; 이하 FA)와 평균확산도(mean diffusivity; 이하 MD)이다. FA는 물 분자 운동의 방향성을 반영하는 수치로, 1에 가까우면 비등방성(anisotropic) 운동에 가까워지고, 이에 정상적인 뇌내 백질은 1에 가까운 수치를 나타낸다. 반면 신경다발(neural bundle)에 손상이 있으면 0에 가까운 수치를 보인다. MD의 경우 뇌조직 내 유리 물 분자의 확산을 정량화하고, 조직의 변성에 의한 손상이 있을 때 값이 증가하게 된다(52). 따라서 확산텐서영상을 이용하면 신경조직의 변성 정도를 정량화할 수 있다.

확산텐서영상을 파킨슨병의 중뇌 흑질 영역에 적용하여 흑질 변성 정도를 알아본 많은 시도들이 있었다. 다양한 연구들이 정상인과 비교하여 파킨슨병 환자에서 흑질 내 FA의 감소 및 MD의 증가가 있음을 보고하였고, 파킨슨병의 초기 단계에서도 같은 결과가 있었다(53,54). 이런 변화는 특히 흑질의 미측(caudal)에서 더욱 뚜렷하여 도파민 신경세포의 변성을 반영하는 것으로 보이고, 파킨슨병의 진단에 매우 높은 성능을 보였다(55). 확산텐서영상의 측정치는 파킨슨병의 임상 증상을 나타내는 UPDRS-III 점수와 연관성을 보였고, 특히 흑질에서의 변화는 느린 움직임뿐만 아니라 인지 장애를 잘 반영하여 경도인지장애를 가진 파킨슨병 환자에서는 인지가 정상인 환자보다 흑질의 FA 값이 감소한다는 보고가 있었다(56,57).

최근 multi-shell diffusion-weighted imaging 기반의 자유수영상(free-water imaging; 이하 FWI)이 퇴행성 뇌질환의 평가에 있어 주목받고 있다(58). FWI는 기존 DTI 영상에 two-compartment model 분석을 접목하여, 조직 내 세포 외 물 분자(extracellular free-water)의 효과를 배제한 FW의 측정을 가능하게 한다(58,59). 이를 이용하여 신경조직의 퇴행성 변성과 주로 세포 외 물 분자가 증가하는 염증 혹은 부종을 구별할 수 있다(59). 파킨슨병에서는 정상인에 비해 후방 흑질의 FW 값이 증가한다는 여러 보고가 있다(60,61). FW 값 역시 UPDRS-III 점수와 연관성을 보였고, 특히 파킨슨병의 진행과 함께 FW 값도 증가한다는 것이 밝혀졌다(60,62,63).

철-민감 영상과 마찬가지로 확산텐서영상과 123I-FP-CIT SPECT의 연관성은 아직 많이 연구되지는 않았다. 한 연구에서 확산텐서 측정치와 선조체 도파민 운반체의 흡수율 사이에는 유의한 상관관계가 없다고 보고하여(64), 앞으로 더 많은 연구가 필요하겠다.

비정형 파킨슨증에서 중뇌 흑질과 기저핵 및 소뇌에서 확산텐서값의 변화가 보고되었다(53). 후방 흑질의 FA 값을 비교한 한 연구에 따르면, 해당 측정치는 정상에서보다 파킨슨병 및 진행성핵상마비와 MSA-P에서 낮았다. 후방 꼬리핵(caudate nucleus)에서의 FA 값은 MSA-P가 진행성핵상마비보다 낮아서 이를 이용한 감별 진단의 가능성을 보였다. 특히 MSA-P의 경우 꼬리핵뿐만 아니라 가리비핵에서의 FA의 감소와 MD의 증가가 파킨슨병보다 유의하게 높았고, MSA-C의 경우 소뇌에서 측정한 FA 값에 유의미한 차이가 있었다. 진행성핵상마비의 경우 중뇌에서 측정한 확산텐서값의 변화가 두드러졌다. 따라서 확산텐서영상은 비정형 파킨슨증의 감별 진단에 도움이 되는 특이적인 변화를 반영할 수 있겠다(Table 1). 특히, 진행성핵상마비와 다계통위축에서도 파킨슨병과 마찬가지로 흑질의 FW 값이 증가하나, 파킨슨병과는 달리 기저핵, 시상, 소뇌 등 흑질 이외의 구조물에도 전반적인 증가 소견을 보이는 것으로 알려졌다(65,66).

정상인과 비교하여 iRBD 환자에서 중뇌 흑질의 FA가 유의미하게 감소한다는 보고가 있었고, 최근에 후방 흑질의 FW 값이 유의하게 증가한다는 연구가 발표되었다(Table 1) (67,68). 이는 중뇌의 도파민성 신경 변성이 전구질환 단계에서부터 일어나는 것을 반영하는 결과로 해석된다. 다만 상기 확산텐서값의 변화는 흑질선조체 신경경로 이외에도 뇌의 다양한 구조물에서도 보고되어, 신경 변성의 프로세스가 전구질환 단계부터 광범위할 가능성도 제시된다.

결론

최신 자기공명영상 기법의 발전은 파킨슨병의 기저 신경해부학적 변화 및 병태생리를 나타내는 다양한 영상 소견들을 제공할 수 있게 하였다. 그중에서도 흑질선조체 변성을 반영하는 나이그로좀 영상, 뉴로멜라닌 영상, 철-민감 영상 및 확산텐서영상은 파킨슨병의 진단율을 높이고, 비정형파킨슨증과의 감별 진단에 도움을 주며, 정량화를 통해 임상 증상과 연관시키고 질병 진행을 모니터링할 수 있게 한다(Table 2). 나아가 도파민 운반체 영상과도 유의미한 연관을 보이며, 특히 파킨슨병 발병 전의 전구질환 단계에서도 미리 흑질선조체 변성을 검출할 수 있는 방법을 제공한다. 따라서 각 영상 기법의 원리 및 특이적 영상 소견을 숙지하여, 임상적으로 파킨슨병의 평가에 적절하게 적용하는 것이 중요하겠다.

Table 2. Proposed Roles of MRI in Parkinson’s Disease.

| Techniques | Individual Diagnosis | Symptom Correlation | Quantification | Differential Diagnosis from Atypical Parkinsonism* | Correlation with Dopamine Transporter Imaging | Monitoring Disease Progression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nigrosome imaging | ++ | +† | − | +/− | ++‡ | − |

| Neuromelanin imaging | +§ | ++ | ++ | +/− | ++‡ | ++ |

| Iron-sensitive imaging | +|| | + | ++ | +/−|| | +¶ | + |

| Diffusion tensor imaging | − | + | ++ | +/− | − | + |

*Some features show overlap between Parkinson’s disease, progressive supranuclear palsy, and multiple system atrophy. But most of the findings can be used for the differentiation from the non-striatal disease.

†Loss of nigral hyperintensity has a good correlation with symptom asymmetry, but does not correlate with motor scores linearly.

‡Loss of nigral hyperintensity has a good positive correlation with the presence of reduced dopamine transporter uptake, but it should be noted that nigrosome imaging determines the presence or absence of nigral hyperintensity at the current stage. Meanwhile, the neuromelanin-rich signal and area are positively correlated with dopamine transporter uptake values in a quantitative manner.

§There can be overlap between the patients with Parkinson’s disease and the controls.

∥The pattern of the iron deposits in the substantia nigra including nigrosome and the basal ganglia can assist diagnosis, but the quantitative value itself cannot be used for the individual diagnosis for now.

¶Striatal susceptibility values are reversely correlated with dopamine transporter uptake values.

+ = possible, ++ = strongly possible, +/- = varying confidence

Footnotes

- Conceptualization, K.J., B.Y.J., C.B.S.

- methodology, B.Y.J.

- resources, K.J., B.Y.J., S.Y.S., N.Y., C.S.J., K.J.H.

- software, K.J., B.Y.J., S.Y.S., N.Y.

- supervision, K.J., B.Y.J., C.B.S., S.Y.S., K.J.H., K.S.E.

- validation, K.J., C.B.S., S.Y.S., N.Y., C.S.J., K.J.H.

- visualization, K.J., B.Y.J., C.B.S., S.Y.S., N.Y., K.S.E.

- writing—original draft, K.J., B.Y.J., C.B.S.

- writing—review & editing, all authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: This study was supported by grant No. 02-2021-0015 from the Seoul National University Bundang Hospital Research Fund.

References

- 1.Damier P, Hirsch EC, Agid Y, Graybiel AM. The substantia nigra of the human brain. I. Nigrosomes and the nigral matrix, a compartmental organization based on calbindin D(28K) immunohistochemistry. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 8):1421–1436. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.8.1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damier P, Hirsch EC, Agid Y, Graybiel AM. The substantia nigra of the human brain. II. Patterns of loss of dopamine-containing neurons in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 1999;122(Pt 8):1437–1448. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.8.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rispoli V, Schreglmann SR, Bhatia KP. Neuroimaging advances in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2018;31:415–424. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwarz ST, Xing Y, Tomar P, Bajaj N, Auer DP. In vivo assessment of brainstem depigmentation in Parkinson disease: potential as a severity marker for multicenter studies. Radiology. 2017;283:789–798. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langkammer C, Krebs N, Goessler W, Scheurer E, Ebner F, Yen K, et al. Quantitative MR imaging of brain iron: a postmortem validation study. Radiology. 2010;257:455–462. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10100495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guan X, Xu X, Zhang M. Region-specific iron measured by MRI as a biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33:561–567. doi: 10.1007/s12264-017-0138-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foo H, Mak E, Yong TT, Wen MC, Chander RJ, Au WL, et al. Progression of small vessel disease correlates with cortical thinning in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;31:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sang T, He J, Wang J, Zhang C, Zhou W, Zeng Q, et al. Alterations in white matter fiber in Parkinson disease across different cognitive stages. Neurosci Lett. 2022;769:136424. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2021.136424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blazejewska AI, Schwarz ST, Pitiot A, Stephenson MC, Lowe J, Bajaj N, et al. Visualization of nigrosome 1 and its loss in PD: pathoanatomical correlation and in vivo 7 T MRI. Neurology. 2013;81:534–540. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829e6fd2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarz ST, Afzal M, Morgan PS, Bajaj N, Gowland PA, Auer DP. The ‘swallow tail’ appearance of the healthy nigrosome-a new accurate test of Parkinson’s disease: a case-control and retrospective cross-sectional MRI study at 3T. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cosottini M, Frosini D, Pesaresi I, Donatelli G, Cecchi P, Costagli M, et al. Comparison of 3T and 7T susceptibility-weighted angiography of the substantia nigra in diagnosing Parkinson disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:461–466. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noh Y, Sung YH, Lee J, Kim EY. Nigrosome 1 detection at 3T MRI for the diagnosis of early-stage idiopathic Parkinson disease: assessment of diagnostic accuracy and agreement on imaging asymmetry and clinical laterality. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2015;36:2010–2016. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A4412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reiter E, Mueller C, Pinter B, Krismer F, Scherfler C, Esterhammer R, et al. Dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity on 3.0T susceptibility-weighted imaging in neurodegenerative Parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1068–1076. doi: 10.1002/mds.26171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bae YJ, Kim JM, Kim E, Lee KM, Kang SY, Park HS, et al. Loss of nigral hyperintensity on 3 tesla MRI of parkinsonism: comparison with (123) I-FP-CIT SPECT. Mov Disord. 2016;31:684–692. doi: 10.1002/mds.26584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao P, Zhou PY, Wang PQ, Zhang GB, Liu JZ, Xu F, et al. Universality analysis of the existence of substantia nigra “swallow tail” appearance of non-Parkinson patients in 3T SWI. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:1307–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JM, Jeong HJ, Bae YJ, Park SY, Kim E, Kang SY, et al. Loss of substantia nigra hyperintensity on 7 Tesla MRI of Parkinson’s disease, multiple system atrophy, and progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;26:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2016.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acosta-Cabronero J, Cardenas-Blanco A, Betts MJ, Butryn M, Valdes-Herrera JP, Galazky I, et al. The whole-brain pattern of magnetic susceptibility perturbations in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2017;140:118–131. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langley J, Huddleston DE, Sedlacik J, Boelmans K, Hu XP. Parkinson’s disease-related increase of T2*-weighted hypointensity in substantia nigra pars compacta. Mov Disord. 2017;32:441–449. doi: 10.1002/mds.26883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sung YH, Lee J, Nam Y, Shin HG, Noh Y, Shin DH, et al. Differential involvement of nigral subregions in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:542–553. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho SJ, Bae YJ, Kim JM, Kim HJ, Baik SH, Sunwoo L, et al. Iron-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2021;268:4721–4736. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10582-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tatsch K, Poepperl G. Nigrostriatal dopamine terminal imaging with dopamine transporter SPECT: an update. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1331–1338. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sung YH, Noh Y, Lee J, Kim EY. Drug-induced Parkinsonism versus idiopathic Parkinson disease: utility of nigrosome 1 with 3-T imaging. Radiology. 2016;279:849–858. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oustwani CS, Korutz AW, Lester MS, Kianirad Y, Simuni T, Hijaz TA. Can loss of the swallow tail sign help distinguish between Parkinson disease and the Parkinson-plus syndromes? Clin Imaging. 2017;44:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2017.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez Akly MS, Stefani CV, Ciancaglini L, Bestoso JS, Funes JA, Bauso DJ, et al. Accuracy of nigrosome-1 detection to discriminate patients with Parkinson’s disease and essential tremor. Neuroradiol J. 2019;32:395–400. doi: 10.1177/1971400919853787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Marzi R, Seppi K, Högl B, Müller C, Scherfler C, Stefani A, et al. Loss of dorsolateral nigral hyperintensity on 3.0 tesla susceptibility-weighted imaging in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:1026–1030. doi: 10.1002/ana.24646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae YJ, Kim JM, Kim KJ, Kim E, Park HS, Kang SY, et al. Loss of substantia nigra hyperintensity at 3.0-T MR imaging in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: comparison with 123I-FP-CIT SPECT. Radiology. 2018;287:285–293. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Pluijm M, Cassidy C, Zandstra M, Wallert E, de Bruin K, Booij J, et al. Reliability and reproducibility of neuromelanin-sensitive imaging of the substantia nigra: a comparison of three different sequences. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;53:712–721. doi: 10.1002/jmri.27384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kashihara K, Shinya T, Higaki F. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of nigral volume loss in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1093–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2010.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, Li Y, Huang Z, Wan W, Zhang Y, Wang C, et al. Neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging features of the substantia nigra and locus coeruleus in de novo Parkinson’s disease and its phenotypes. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:949–e73. doi: 10.1111/ene.13628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho SJ, Bae YJ, Kim JM, Kim D, Baik SH, Sunwoo L, et al. Diagnostic performance of neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging for patients with Parkinson’s disease and factor analysis for its heterogeneity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:1268–1280. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarz ST, Rittman T, Gontu V, Morgan PS, Bajaj N, Auer DP. T1-weighted MRI shows stage-dependent substantia nigra signal loss in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2011;26:1633–1638. doi: 10.1002/mds.23722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fabbri M, Reimão S, Carvalho M, Nunes RG, Abreu D, Guedes LC, et al. Substantia nigra neuromelanin as an imaging biomarker of disease progression in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7:491–501. doi: 10.3233/JPD-171135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuya K, Ogawa T, Shinohara Y, Ishibashi M, Fujii S, Mukuda N, et al. Evaluation of Parkinson’s disease by neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging and 123I-FP-CIT SPECT. Acta Radiol. 2018;59:593–598. doi: 10.1177/0284185117722812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Okuzumi A, Hatano T, Kamagata K, Hori M, Mori A, Oji Y, et al. Neuromelanin or DaT-SPECT: which is the better marker for discriminating advanced Parkinson’s disease? Eur J Neurol. 2019;26:1408–1416. doi: 10.1111/ene.14009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kashihara K, Shinya T, Higaki F. Reduction of neuromelanin-positive nigral volume in patients with MSA, PSP and CBD. Intern Med. 2011;50:1683–1687. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuura K, Maeda M, Yata K, Ichiba Y, Yamaguchi T, Kanamaru K, et al. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging in Parkinson’s disease and multiple system atrophy. Eur Neurol. 2013;70:70–77. doi: 10.1159/000350291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Huang Z, Li Y, Ye F, Wang C, Zhang Y, et al. Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI of the substantia nigra: an imaging biomarker to differentiate essential tremor from tremor-dominant Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;58:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaurav R, Pyatigorskaya N, Biondetti E, Valabrègue R, Yahia-Cherif L, Mangone G, et al. Deep learning-based neuromelanin MRI changes of isolated REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2022;37:1064–1069. doi: 10.1002/mds.28933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Rochefort L, Liu T, Kressler B, Liu J, Spincemaille P, Lebon V, et al. Quantitative susceptibility map reconstruction from MR phase data using bayesian regularization: validation and application to brain imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63:194–206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pyatigorskaya N, Sanz-Morère CB, Gaurav R, Biondetti E, Valabregue R, Santin M, et al. Iron imaging as a diagnostic tool for Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol. 2020;11:366. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ulla M, Bonny JM, Ouchchane L, Rieu I, Claise B, Durif F. Is R2* a new MRI biomarker for the progression of Parkinson’s disease? A longitudinal follow-up. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wieler M, Gee M, Camicioli R, Martin WR. Freezing of gait in early Parkinson’s disease: nigral iron content estimated from magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Sci. 2016;361:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Du G, Liu T, Lewis MM, Kong L, Wang Y, Connor J, et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping of the midbrain in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016;31:317–324. doi: 10.1002/mds.26417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.He N, Ling H, Ding B, Huang J, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, et al. Region-specific disturbed iron distribution in early idiopathic Parkinson’s disease measured by quantitative susceptibility mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:4407–4420. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langkammer C, Pirpamer L, Seiler S, Deistung A, Schweser F, Franthal S, et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uchida Y, Kan H, Sakurai K, Inui S, Kobayashi S, Akagawa Y, et al. Magnetic susceptibility associates with dopaminergic deficits and cognition in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2020;35:1396–1405. doi: 10.1002/mds.28077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee JH, Lee MS. Brain iron accumulation in atypical Parkinsonian syndromes: in vivo MRI evidences for distinctive patterns. Front Neurol. 2019;10:74. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azuma M, Hirai T, Nakaura T, Kitajima M, Yamashita S, Hashimoto M, et al. Combining quantitative susceptibility mapping to the morphometric index in differentiating between progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2019;406:116443. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2019.116443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mazzucchi S, Frosini D, Costagli M, Del Prete E, Donatelli G, Cecchi P, et al. Quantitative susceptibility mapping in atypical Parkinsonisms. Neuroimage Clin. 2019;24:101999. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Novellino F, Cherubini A, Chiriaco C, Morelli M, Salsone M, Arabia G, et al. Brain iron deposition in essential tremor: a quantitative 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging study. Mov Disord. 2013;28:196–200. doi: 10.1002/mds.25263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun J, Lai Z, Ma J, Gao L, Chen M, Chen J, et al. Quantitative evaluation of iron content in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2020;35:478–485. doi: 10.1002/mds.27929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C. Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor MRI. J Magn Reson B. 1996;111:209–219. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prodoehl J, Li H, Planetta PJ, Goetz CG, Shannon KM, Tangonan R, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of Parkinson’s disease, atypical parkinsonism, and essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1816–1822. doi: 10.1002/mds.25491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atkinson-Clement C, Pinto S, Eusebio A, Coulon O. Diffusion tensor imaging in Parkinson’s disease: review and meta-analysis. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;16:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vaillancourt DE, Spraker MB, Prodoehl J, Abraham I, Corcos DM, Zhou XJ, et al. High-resolution diffusion tensor imaging in the substantia nigra of de novo Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;72:1378–1384. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000340982.01727.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ofori E, Pasternak O, Planetta PJ, Li H, Burciu RG, Snyder AF, et al. Longitudinal changes in free-water within the substantia nigra of Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 8):2322–2331. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen F, Wu T, Luo Y, Li Z, Guan Q, Meng X, et al. Amnestic mild cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease: white matter structural changes and mechanisms. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0226175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pasternak O, Sochen N, Gur Y, Intrator N, Assaf Y. Free water elimination and mapping from diffusion MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2009;62:717–730. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoy AR, Koay CG, Kecskemeti SR, Alexander AL. Optimization of a free water elimination two-compartment model for diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2014;103:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guttuso T, Jr, Bergsland N, Hagemeier J, Lichter DG, Pasternak O, Zivadinov R. Substantia nigra free water increases longitudinally in Parkinson disease. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39:479–484. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ofori E, Krismer F, Burciu RG, Pasternak O, McCracken JL, Lewis MM, et al. Free water improves detection of changes in the substantia nigra in parkinsonism: a multisite study. Mov Disord. 2017;32:1457–1464. doi: 10.1002/mds.27100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Burciu RG, Ofori E, Archer DB, Wu SS, Pasternak O, McFarland NR, et al. Progression marker of Parkinson’s disease: a 4-year multi-site imaging study. Brain. 2017;140:2183–2192. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang J, Archer DB, Burciu RG, Müller MLTM, Roy A, Ofori E, et al. Multimodal dopaminergic and free-water imaging in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019;62:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Y, Wu IW, Buckley S, Coffey CS, Foster E, Mendick S, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging of the nigrostriatal fibers in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1229–1236. doi: 10.1002/mds.26251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Planetta PJ, Ofori E, Pasternak O, Burciu RG, Shukla P, DeSimone JC, et al. Free-water imaging in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Brain. 2016;139(Pt 2):495–508. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mitchell T, Archer DB, Chu WT, Coombes SA, Lai S, Wilkes BJ, et al. Neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging (NODDI) and free-water imaging in Parkinsonism. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:5094–5107. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pyatigorskaya N, Gaurav R, Arnaldi D, Leu-Semenescu S, Yahia-Cherif L, Valabregue R, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging biomarkers to assess substantia nigra damage in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2017;40:zsx149. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsx149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhou L, Li G, Zhang Y, Zhang M, Chen Z, Zhang L, et al. Increased free water in the substantia nigra in idiopathic REM sleep behaviour disorder. Brain. 2021;144:1488–1497. doi: 10.1093/brain/awab039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]