Abstract

During sporulation in diploid Saccharomyces cerevisiae, spindle pole bodies acquire the so-called meiotic plaque, a prerequisite for spore formation. Mpc70p is a component of the meiotic plaque and is thus essential for spore formation. We show here that MPC70/mpc70 heterozygous strains most often produce two spores instead of four and that these spores are always nonsisters. In wild-type strains, Mpc70p localizes to all four spindle pole bodies, whereas in MPC70/mpc70 strains Mpc70p localizes to only two of the four spindle pole bodies, and these are always nonsisters. Our data can be explained by conservative spindle pole body distribution in which the two newly synthesized meiosis II spindle pole bodies of MPC70/mpc70 strains lack Mpc70p.

In the absence of nitrogen and in the presence of a nonfermentable carbon source, Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells of the MATa/MATα constitution undergo meiosis, a process that results in the formation of four haploid spores. In baker's yeast, both meiotic divisions occur within a single continuous nuclear envelope. Spore formation begins late during the second meiotic division (meiosis II). At that stage, the nuclear envelope assumes a four-lobed structure. One meiosis II spindle pole body is located at each tip of the four lobes and one haploid genome equivalent is segregated into each of the lobes (9). The so-called prospore membrane forms on the cytoplasmic side of each spindle pole body, extends like a pouch around the lobes of each nucleus, and eventually fuses with itself to enclose a haploid nucleus (5, 6, 9, 10).

In S. cerevisiae, the spindle pole bodies are functionally equivalent to centrosomes in higher eukaryotes. In mitotic cells, the spindle pole bodies coordinate the segregation of chromosomes and nuclear migration through interaction with intra- and extranuclear microtubules, respectively (4, 13, 14). Meiotic spindle pole bodies nucleate the formation of spores in addition to coordinating the segregation of chromosomes during both meiotic divisions. This sporulation-specific function of spindle pole bodies is executed during the second meiotic division. Ultrastructural studies have revealed a sporulation-specific modification of spindle pole bodies late in meiosis: they acquire the so-called meiotic plaque on their cytoplasmic side. This modification of spindle pole bodies is a key prerequisite for spore formation (2, 9). Mutations that impair the formation of meiotic plaques result in the absence of prospore membranes on the respective spindle pole bodies (5, 11, 16). Similarly, the formation of two-spored (instead of four-spored) asci in diploid wild-type cells is a direct consequence of the failure to synthesize meiotic plaques on all four spindle pole bodies (2).

Mpc70p is a meiotic plaque protein and is therefore essential for spore formation (5). We show here that MPC70/mpc70 heterozygotes most often produce two spores instead of four and that these are always nonsisters. The distribution of Mpc70p to only two of the four spindle pole bodies in MPC70/mpc70 heterozygotes suggests that Mpc70p is present in limiting amounts and is distributed to the spindle pole bodies by a conservative mechanism.

Dosage of MPC70 is critical for the efficiency of spore formation.

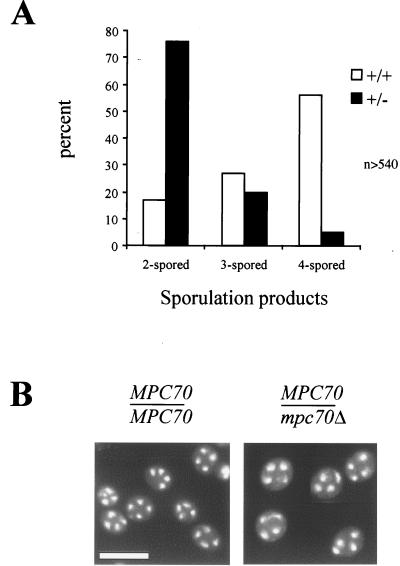

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. When a culture of wild-type cells is transferred from rich medium (2% glucose [12]) to sporulation medium (1% potassium acetate, 0.02% raffinose), the final sporulation products are, as expected, primarily tetrads. However, about one-third of the terminal sporulation products in a wild-type cell population consist of triads and dyads (Fig. 1A) despite the fact that the majority of cells display a tetranucleate staining pattern during spore formation (Fig. 1B). To visualize DNA in a sporulating culture, ethanol-fixed cells were incubated with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at a concentration of 0.4 mg/liter and then viewed with a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope equipped with Openlab software. Pictures were captured using a Hamamatsu digital camera (C4742–95). We dissected triads and dyads of a wild-type culture and found that the spores gave rise to haploid progeny and that auxotrophic markers segregated as expected for a diploid undergoing meiosis. These data suggest that the triads and dyads found in wild-type culture result from a failure to form spores even though the meiotic divisions were typically complete.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| WAY627 | ura3/ura3 leu2::hisG/LEU2 his3::hisG/his3::hisG TRP1/trp1::hisG lys2/lys2 ho::LYS2/ho::LYS2 |

| WAY622 | MATα ura3 leu2::hisG his3::hisG lys2 ho::LYS2 |

| WAY690 | ura3/ura3 leu2::hisG/LEU2 his3::hisG/his3::hisG TRP1/trp1::hisG lys2/lys2 ho::LYS2/ho::LYS2 mpc70::his5/mpc70::his5 |

| WAY683 | ura3/ura3 leu2::hisG/LEU2 his3::hisG/his3::hisG TRP1/trp1::hisG lys2/lys2 ho::LYS2/ho::LYS2 mpc70::his5/MPC70 |

| WAY1022 | ura3/ura3 leu2::hisG/LEU2 his3::hisG/his3::hisG TRP1/trp1::hisG lys2/lys2 ho::LYS2/ho::LYS2 MPC70:3HA/mpc70::his5 |

| WAY1030 | ura3/ura3 leu2::hisG/LEU2 his3::hisG/his3::hisG TRP1/trp1::hisG lys2/lys2 ho::LYS2/ho::LYS2 MPC70:3HA/MPC70 |

FIG. 1.

The level of MPC70 is critical for the efficiency of spore formation. Wild-type (+/+) and MPC70/mpc70 (+/−) cultures were subjected to sporulation for 32 h. (A) The numbers of two-, three-, and four-spored terminal sporulation products were determined microscopically and expressed as percentages of the total (sum of dyads, triads, and tetrads). At least 540 individual terminal products were considered. Wild-type cells mainly produced tetrads as terminal sporulation products, while MPC70/mpc70 cells mainly yielded dyads. (B) DAPI staining of wild-type (MPC70/MPC70) and heterozygous (MPC70/mpc70) mutants subjected to sporulation medium for 7 h. The majority of cells in both cultures displayed a tetranucleate staining pattern. Bar, 10 μm.

mpc70/mpc70 mutants complete the meiotic divisions, but no spores are formed (15; our unpublished observations). A culture of the MPC70/mpc70 heterozygote, however, routinely yielded more than 70% of the terminal sporulation products as dyads (Fig. 1A), corresponding to a fivefold increase in dyad formation compared to wild-type cells. The increased formation of dyads was not a consequence of failed meiotic divisions, because the vast majority of MPC70/mpc70 cells displayed a tetranucleate staining pattern during spore formation (Fig. 1B). Consistent with this, spores from dyads and triads of a culture of MPC70/mpc70 cells gave rise to haploid progeny, and the auxotrophic markers in the cross segregated as expected for a diploid undergoing meiosis. Spores recovered from dyads of MPC70/mpc70 cultures contained either wild-type MPC70 or the mutant mpc70 allele. Thus, MPC70 is haploinsufficient for tetrad formation but does not act in a spore-autonomous way.

Using the centromere-linked trp1 auxotrophic marker, we found that dyads from both wild-type and MPC70/mpc70 cultures consisted of nonsister spores (one TRP1 and one trp1). Chi-square analysis was performed with the null hypothesis being that dyads were generated randomly (two-thirds should be nonsister dyads and one-third should be sister dyads). The resulting P value of less than 0.01 indicates that dyads generated in wild-type and MPC70/mpc70 heterozygotes are most likely not the result of random failure of spore formation among four nuclei in any given ascus. Together, our results indicate that Mpc70p is a limiting component during spore formation and that reduced levels of MPC70 result in an increased frequency of nonsister dyad formation. However, we found that the introduction of additional copies of MPC70 in a wild-type strain did not increase the efficiency of tetrad formation. Therefore, MPC70 is necessary but not sufficient for the efficient packaging of all four spores.

Mpc70p is distributed to the spindle pole bodies by a conservative mechanism.

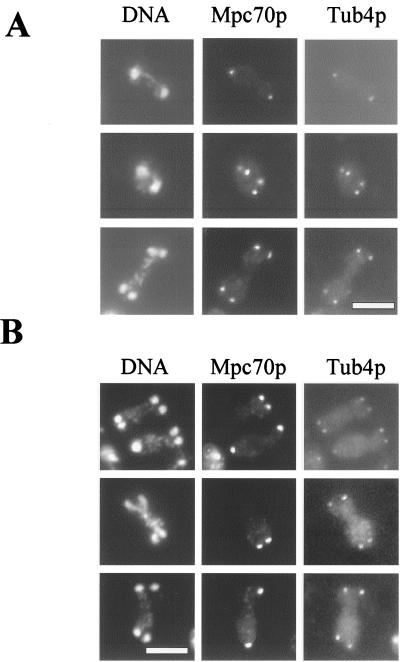

To determine when in the sequence of meiotic divisions Mpc70p is recruited to spindle pole bodies, we localized both Mpc70p and Tub4p (gamma tubulin) in sporulating wild-type strains. Colocalization would signal recruitment of Mpc70p to the spindle pole bodies because yeast gamma tubulin is an intrinsic component of this organelle (7, 15). Diploids with one genomic copy of wild-type MPC70 replaced by an MPC70-HA allele, where a triple hemagglutinin antigen (HA) tag was fused in-frame 249 nucleotides downstream of the start codon of MPC70, were sporulated and processed for immunofluorescence (17). Anti-gamma tubulin (Tub4p [3]) and anti-Mpc70p (HA) antibodies were added and visualized using rhodamine- and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-coupled secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.), respectively. No cross-reactivities of the secondary antibodies were observed, and no FITC signal was detected in cells lacking the MPC70-HA construct. DNA was visualized using DAPI contained within the mounting medium (Vectashield, Burlingame, Calif.).

Prior to the first meiotic division, we detected Tub4p but not Mpc70p on the spindle pole bodies. This is consistent with the absence of MPC70 mRNA early in meiosis (1). As the spindle pole bodies duplicated and the meiosis I spindles formed, we frequently detected mononucleate and binucleate cells with Mpc70p on both meiosis I spindle pole bodies. As meiosis proceeded, Mpc70p was associated with all spindle pole bodies of binucleate cells both before and after the two meiosis I spindle pole bodies duplicated (Fig. 2A). After completion of the second meiotic division (as indicated by tetranucleate cells), Mpc70p remained associated with all four spindle pole bodies (Fig. 2A). Thus, in the majority of wild-type cells, Mpc70p localized to all spindle pole bodies throughout both meiotic divisions.

FIG. 2.

Localization of Mpc70p to only one spindle pole body of each meiosis II spindle in MPC70/mpc70 mutants and colocalization of Mpc70p with Tub4p to spindle pole bodies during meiotic divisions. Cells were sporulated, fixed, and processed for immunofluorescence of Mpc70p and Tub4p. DNA was visualized with DAPI. (A) In wild-type cells, Mpc70p localizes to all spindle pole bodies of binucleate cells both before and after the duplication of meiosis I spindle pole bodies, as well as to all four spindle pole bodies of tetranucleate cells. (B) In heterozygous MPC70/mpc70 mutants, however, Mpc70p localizes to only two of the four spindle pole bodies. Importantly, the Mpc70p-positive spindle pole bodies are always associated with nonsister genomes. Bar, 5 μm.

Since Mpc70p is essential for spore formation and a reduced level of MPC70 results in the formation of nonsister dyads (Fig. 1), we determined the Mpc70p localization pattern in sporulating MPC70/mpc70 heterozygotes carrying an HA-tagged allele as the sole functional copy of MPC70. Cells were processed for immunolocalization of Mpc70-HAp and Tub4p as described above. We found that Mpc70p localizes to both meiosis I spindle pole bodies in both mononucleate and binucleate cells. As meiosis proceeds, in the majority of MPC70/mpc70 cells, unlike the situation in wild-type cells, Mpc70p is associated with only two of the four meiosis II spindle pole bodies (Fig. 2B). Remarkably, the two Mpc70p-positive spindle pole bodies were always associated with nonsister genomes, which was inferred from comparison of the spindle orientation with Mpc70p staining (Fig. 2B). This observation is consistent with our genetic findings that a culture of MPC70/mpc70 heterozygous mutants predominantly forms nonsister dyads. Moreover, it demonstrates directly that only Mpc70p-positive spindle pole bodies are competent for spore formation.

Mpc70p is limiting for spore formation.

Although a population of wild-type cells yields primarily asci with four spores (tetrads) as the final sporulation product, dyads are always recovered from such cultures. Previous studies have shown that generation of these dyads in wild-type culture is not the result of random death of spores (2). Rather, the spores recovered from those dyads always contained nonsister genomes. That is, only one haploid genome of each meiosis II spindle was recovered and only one spindle pole body of each of the meiosis II spindles carried a meiotic plaque. On the basis of these observations, it has been proposed that duplication of spindle pole bodies occurs in a conservative manner (that is, preexisting spindle pole bodies serve as templates for the synthesis of new spindle pole bodies) and that certain proteins essential for meiotic plaque formation may be limiting in wild-type cells (2).

Mpc70p is a meiotic plaque protein (5). We show here that MPC70/mpc70 strains that have only one of the two copies of MPC70 yield primarily dyads and that those dyads are always composed of nonsister spores. Thus, the molecular basis for dyad formation in MPC70/mpc70 mutants is likely the same nonrandom process that yields dyads in wild-type culture: the presence of only one meiotic plaque per meiosis II spindle. This conclusion is supported by the finding that in the majority of MPC70/mpc70 heterozygotes, Mpc70p localized to only two of the four meiosis II spindle pole bodies and, importantly, those spindle pole bodies were associated with nonsister genomes. Thus, only Mpc70p-positive spindle pole bodies are competent for spore formation.

What is the function of Mpc70p on the spindle pole bodies? Mpc70p may provide a meiosis-specific scaffold for the assembly of other proteins on spindle pole bodies, which themselves may assist prospore membrane assembly. Consistent with this, Mpc70p, like other structural components of the spindle pole body, contains a coiled-coil domain that can engage in both homotypic and heterotypic interactions (5; our unpublished observations). Alternatively, as Mpc70p is a component of the meiotic plaques of spindle pole bodies, it may directly bind prospore membrane vesicles and thereby control prospore membrane formation on spindle pole bodies.

The effects of mpc70 mutation differ from other parameters and mutations that alter the number of spores resulting from meiosis. For example, nutrient availability and temperature can influence the ratio between tetrads, triads, and dyads (8). In addition, mutations can lead to the formation of only dyads, even though meiotic divisions are complete. For example, one such mutation (hfd1-1) produces dyads consisting of nonsister spores (11) whereas other mutations (cyr1-1, spo3) mainly produce dyads consisting of random spores (16). It is important to realize, however, that in those cases the dyads were formed at a high frequency only if the mutation was present in a homozygous configuration. This behavior is unlike that observed for MPC70, where nonsister dyads are formed preferentially in cultures of MPC70/mpc70 heterozygous mutants and mpc70/mpc70 mutants fail to form spores altogether.

The behavior of MPC70/mpc70 heterozygotes is consistent with a conservative distribution of Mpc70p.

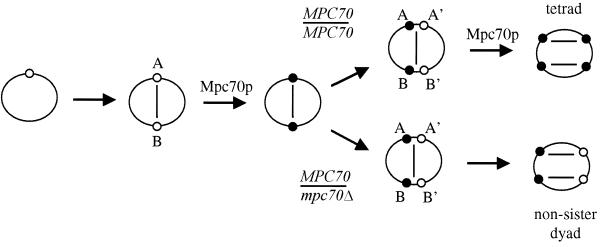

The localization of Mpc70p in MPC70/MPC70 diploids and in MPC70/mpc70 diploids suggests that the sequence of conservative spindle pole body duplication and modification is fully sufficient to explain the formation of dyads if Mpc70p is limiting (Fig. 3). Mpc70p localized to spindle pole bodies only at a time when the meiosis I spindle had already formed. We later observed Mpc70p on all four meiosis II spindle pole bodies in wild-type cells. This sequence suggests that spindle pole body duplication and Mpc70p-dependent plaque formation alternate during both meiotic divisions and that, under normal circumstances, newly synthesized meiosis II spindle pole bodies without meiotic plaques are short-lived. As a consequence, in wild-type cells, all four spindle pole bodies carry meiotic plaques and thus tetrads are formed.

FIG. 3.

Model of alternate spindle pole body duplication and modification. The model reinforces the assumption that spindle pole bodies duplicate in a conservative fashion during meiosis (2). That is, preexisting spindle pole bodies serve as templates for the synthesis of new spindle pole bodies. Early in meiosis, the sole spindle pole body duplicates to form the meiosis I spindle and Mpc70p is recruited to the two meiosis I spindle pole bodies (A and B) to form meiotic plaques. Novel unmodified meiosis II spindle pole bodies (A′ and B′) without meiotic plaques are then synthesized in a conservative way. In wild-type cells, Mpc70p is then recruited to the newly synthesized meiosis II spindle pole bodies (A′ and B′) to form the meiotic plaques. As a result, prospore membranes form on all four meiosis II spindle pole bodies. In MPC70/mpc70 mutants, however, all of the Mpc70p is consumed for meiotic plaque formation at the two meiosis I spindle pole bodies; therefore, no Mpc70p is left to be recruited to the newly synthesized meiosis II spindle pole bodies (A′ and B′). As a consequence, only one spindle pole body each from the two meiosis II spindles is modified (A and B), and only nonsister dyads form. Open and filled circles represent spindle pole bodies without and with meiotic plaques, respectively.

However, if a meiotic plaque protein such as Mpc70p becomes limiting prior to (or at) the duplication of meiosis I spindle pole bodies, cells end up with two newly synthesized meiosis II spindle pole bodies without meiotic plaques and with two (parental) meiosis II spindle pole bodies carrying meiotic plaques (Fig. 3). Our results suggest that this scenario occurs in the majority of MPC70/mpc70 cells: Mpc70p is consumed for meiotic plaque formation on the meiosis I spindle pole bodies and therefore no Mpc70p is available for meiotic plaque formation on the newly synthesized meiosis II spindle pole bodies. As a consequence, nonsister dyads are prevalent as terminal sporulation products.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant GM35010. G.R.F. is an American Cancer Society Professor of Genetics. A.W. was supported by grants from the Roche Research Foundation, the Novartis Fonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaft, and the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds.

This work was conducted at the W. M. Keck Foundation Biological Imaging Facility of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chu S, DeRisi J, Eisen M, Mulholland J, Botstein D, Brown P, Herskowitz I. The transcriptional program of sporulation in budding yeast. Science. 1998;282:699–705. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5389.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davidow L, Goetsch L, Byers B. Preferential occurrence of nonsister spores in two-spored asci of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: evidence for regulation of spore-wall formation by the spindle pole body. Genetics. 1980;94:581–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/94.3.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geissler S, Pereira G, Spang A, Knop M, Soues S, Kilmartin J, Schiebel E. The spindle pole body component Spc98p interacts with the gamma tubulin-like Tub4p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae at the sites of microtubule attachment. EMBO J. 1996;15:3899–3911. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knop M, Pereira G, Schiebel E. Microtubule organization by the budding yeast spindle pole body. Biol Cell. 1999;91:291–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knop M, Strasser K. Role of the spindle pole body of yeast in mediating assembly of the prospore membrane during meiosis. J Cell Biol. 2000;19:3657–3667. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynn R, Magee P. Development of the spore wall during ascospore formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1969;44:688–692. doi: 10.1083/jcb.44.3.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marschall L, Jeng R, Mulholland J, Stearns T. Analysis of Tub4p, a yeast gamma tubulin-like protein: implications for microtubule-organizing center function. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:443–454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller J. Sporulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Rose A H, Harrison J S, editors. The yeasts. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 489–550. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moens P, Rapport E. Spindles, spindle plaques and meiosis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Hansen) J Cell Biol. 1971;50:344–361. doi: 10.1083/jcb.50.2.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neiman A. Prospore membrane formation defines a developmentally regulated branch of the secretory pathway in yeast. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:29–37. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sherman F, Hicks J. Micromanipulation and dissection of asci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:21–37. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94005-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder M. The spindle pole body of yeast. Chromosoma. 1994;103:369–380. doi: 10.1007/BF00362281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sobel S. Mini review: mitosis and the spindle pole body in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Exp Zool. 1997;277:120–138. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-010x(19970201)277:2<120::aid-jez4>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spang A, Geissler S, Grein K, Schiebel E. Gamma tubulin-like Tub4p of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is associated with the spindle pole body substructures that organize microtubules and is required for mitotic spindle formation. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:429–441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uno I, Matsumoto K, Hirata A, Ishikawa T. Outer plaque assembly and spore encapsulation are defective during sporulation of adenylate cyclase-deficient mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1854–1862. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.6.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visentin R, Hwang E S, Amon A. Cfi1 prevents premature exit from mitosis by anchoring Cdc14 phosphatase in the nucleolus. Nature. 1999;398:818–823. doi: 10.1038/19775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]