BACKGROUND:

“Moral distress” describes the psychological strain a provider faces when unable to uphold professional values because of external constraints. Recurrent or intense moral distress risks moral injury, burnout, and physician attrition but has not been systematically studied among neurosurgeons.

OBJECTIVE:

To develop a unique instrument to test moral distress among neurosurgeons, evaluate the frequency and intensity of scenarios that may elicit moral distress and injury, and determine their impact on neurosurgical burnout and turnover.

METHODS:

An online survey investigating moral distress, burnout, and practice patterns was emailed to attending neurosurgeon members of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Moral distress was evaluated through a novel survey designed for neurosurgical practice.

RESULTS:

A total of 173 neurosurgeons completed the survey. Half of neurosurgeons (47.7%) reported significant moral distress within the past year. The most common cause was managing critical patients lacking a clear treatment plan; the most intense distress was pressure from patient families to perform futile surgery. Multivariable analysis identified burnout and performing ≥2 futile surgeries per year as predictors of distress (P < .001). Moral distress led 9.8% of neurosurgeons to leave a position and 26.6% to contemplate leaving. The novel moral distress survey demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach alpha = 0.89).

CONCLUSION:

We developed a reliable survey assessing neurosurgical moral distress. Nearly, half of neurosurgeons suffered moral distress within the past year, most intensely from external pressure to perform futile surgery. Moral distress correlated with burnout risk caused 10% of neurosurgeons to leave a position and a quarter to consider leaving.

KEY WORDS: Attrition, Burnout, Futile surgery, Moral distress, Moral injury, Neurosurgery

ABBREVIATION:

- OLBI

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory.

“Moral distress” describes the psychological strain a healthcare provider faces when unable to uphold professional values because of external constraints.1 The fundamental tension is the frustration of the provider from inability to act consistent with professional values because of interpersonal, administrative, or legal barriers.2 The distress is not associated with shame or negative self-judgment because failure is not the provider's “fault.”3,4 At the extreme lies “moral injury,” a combat trauma term applicable when many recurrent distresses or several extraordinary challenges lead an individual to develop shame, guilt, mistrust, and anger in their role and doubt about their personal values.5

Since its conceptualization, “moral distress” has exploded as a field of inquiry in health care. However, only 4% of studies investigate moral distress among physicians.6 Although physicians experience distress less frequently than nurses or social workers, the intensity of distress is as great or greater,2 suggesting moral injury may be of special concern. In particular, overly aggressive end-of-life care has been identified as a crucial source of distress.7 The consequences of moral distress are significant and include attrition7-10 and physician burnout,9,11,12 which risk negative healthcare outcomes such as medical errors,13 patient noncompliance,14 decreased care quality,15,16 malpractice litigation,17 and a healthcare cost of $4.6 billion per year.18

Neurosurgeons regularly treat patients in dire conditions, engage in end-of-life care, and face performing surgeries that have a little likelihood of meaningful neurological recovery. Although moral distress is acknowledged as an issue for neurosurgeons,19,20 the incidence and severity of its impact has not been systematically studied. The goal of this study was to examine the state and consequences of moral distress among actively practicing US neurosurgeons, identify how end-of-life care contributes to moral injury, and introduce a moral distress measurement to facilitate this analysis.

METHODS

Survey Design

This was a US national survey of actively practicing neurosurgeons. A 34-question online survey evaluating demographics, burnout, and moral distress was created using Qualtrics software (https://www.qualtrics.com). In November 2020, an email with the study purpose and survey link was sent to 3000 active neurosurgeons of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons with 3 reminders over the course of 2 months. One survey could be completed per email address. Responses were anonymous, voluntary, and without incentive. Consent for participation was obtained at the survey outset. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Moral Distress

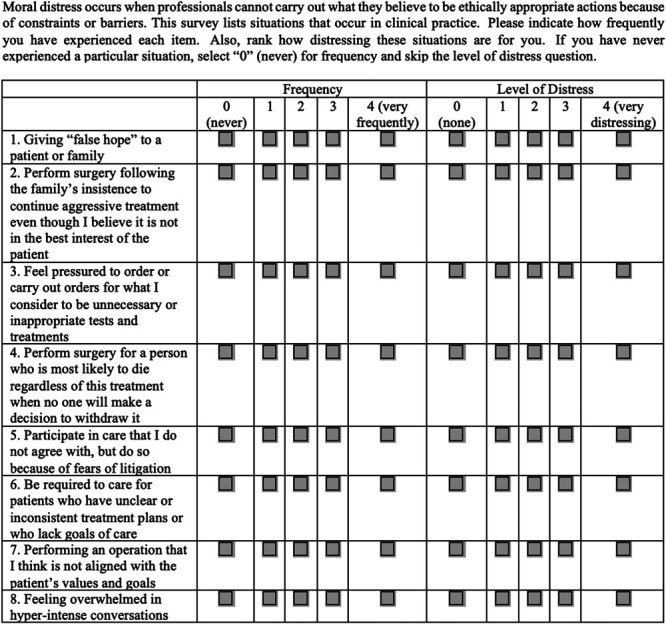

We measured moral distress through 8 items. Six were adapted from the validated measure of moral distress for the healthcare professionals.21 Items were selected to focus on moral distress specific to surgeons asked to provide what they perceived to be futile care. As part of the decision to proceed with surgery, we added 2 questions (7: “performing an operation that I think is not aligned with the patient's values and goals” and 8: “feeling overwhelmed in hyper-intense conversations”) to reflect a surgeon's bedside thought process. We asked respondents to report the frequency and intensity of each circumstance using ordinal scales of 0 to 4 (Figure). We defined neurosurgeons contemplating leaving a current position from the severity of moral distress as “morally injured.”

FIGURE.

Moral distress survey.

Burnout

Burnout is a syndrome resulting from chronic exposure to job-related stress (such as recurrent moral distress).22 We measured burnout using the Oldenburg Burnout Inventory, a publicly available 16-question assessment composed of 2 dimensions: exhaustion and disengagement. Consistent with the literature,23-25 we defined scores of ≥2.25 on exhaustion and ≥2.1 on disengagement as “high.” We designated respondents as “burned out” if responses indicated high exhaustion and high disengagement and designated them as “at risk” if scores were high on only 1 subscale.

Analysis

First, we tabulated provider and practice characteristics and moral distress survey responses and then investigated associations. Second, we investigated important cutoff scores on the moral distress survey for the outcome of potential attrition because of moral distress (ie, the “morally injured” neurosurgeon). Finally, we demonstrated validity support for the moral distress survey.

Statistics

SAS software (SAS Institute) was used for statistical calculation. Moral distress survey scores were reported as mean ± standard deviation. For nonparametric results, Kruskal–Wallis or Wilcoxon rank sum tests compared median scores (Q1-Q3). Multivariable linear regression analyzed characteristics independently associated with survey scores. Score cutoffs were examined for sensitivity/specificity in identifying neurosurgeons contemplating leaving their position. Cronbach alpha assessed the internal consistency of the survey scores. Spearman correlation examined the relationship between moral distress and each Oldenburg Burnout Inventory subscale and responses to self-assessment of moral injury. A P ≤ .05 was significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

Of 3000 survey invitations, there were 336 survey respondents; 173 completed the moral distress survey for a complete study response rate of 5.8%. Most respondents were male (76.2%), burned out (67.1%), in practice >10 years (65.5%), employed at a level I trauma/comprehensive stroke center (77.2%), and took >5 days of call per month (75.7%). One-fifth (20.2%) estimated performing >5 futile surgeries per year (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Respondent Demographics and Practice Characteristics

| Group | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 76.2 (128) |

| Female | 23.8 (40) |

| Years in practice | |

| <5 | 10.5 (18) |

| 5-10 | 24.0 (41) |

| 11-20 | 31.6 (54) |

| >20 | 33.9 (58) |

| Practice setting | |

| Academic | 17 (8-33) |

| Private | 19 (10-39) |

| Privademic | 23 (15-43) |

| Level I trauma or comprehensive stroke center | |

| No | 22.8 (38) |

| Yes | 77.2 (129) |

| Call frequency (days per month) | |

| <3 (n = 16) | 9.5 (16) |

| 3-5 (n = 25) | 14.8 (25) |

| 6-10 (n = 70) | 41.4 (70) |

| >10 (n = 58) | 34.3 (58) |

| Futile surgery frequency | |

| Never (0/y) | 8.7 (15) |

| Rare (1/y) | 28.9 (50) |

| Sometimes (2-5/y) | 42.2 (73) |

| Often (>5/y) | 20.2 (35) |

| Burnout (OLBI) | |

| Burned out | 67.1 (116) |

| At risk | 13.9 (24) |

| Not burned out | 19.1 (33) |

| Burnout (self-assessment) | |

| Yes | 41.0 (71) |

| Maybe | 32.4 (56) |

| No | 24.9 (43) |

| Experienced moral distress within past year | |

| Strongly agree | 23.8 (41) |

| Agree | 23.8 (41) |

| Disagree | 33.7 (58) |

| Strongly disagree | 18.6 (32) |

| Leaving a position because of moral distress | |

| No | 63.6 (110) |

| Considering | 26.5 (46) |

| Have left | 9.8 (17) |

OLBI, Oldenburg Burnout Inventory.

Moral Distress

The median moral distress score was 19 (Q1-Q3 10-35). The most frequently encountered scenario was caring for the patient lacking clear treatment goals. The most distressing scenario was performing futile surgery from family insistence (Table 2). Nearly, half of respondents (47.7%) strongly or generally agreed they had experienced moral distress within the past year (Table 1); they had significantly greater moral distress scores than respondents denying distress (P < .001) (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Moral Distress Survey

| Question | Frequency, mean ± SD (rank) | Intensity, mean ± SD (rank) | Contribution to moral distress score, Mean ± SD (rank) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Giving “false hope” to a patient or family | 0.84 ± 0.87 (8) | 1.50 ± 1.45 (8) | 1.93 ± 2.76 (8) |

| 2. Perform surgery following the family's insistence to continue aggressive treatment even though I believe it is not in the best interest of the patient | 1.53 ± 1.00 (2) | 2.30 ± 1.37 (1) | 4.06 ± 4.00 (2) |

| 3. Feel pressured to order or carry out orders for what I consider to be unnecessary or inappropriate tests and treatments | 1.47 ± 1.12 (3) | 1.79 ± 1.32 (5) | 3.50 ± 3.88 (3) |

| 4. Perform surgery for a person who is most likely to die regardless of this treatment when no one will make a decision to withdraw it | 1.31 ± 1.04 (4) | 1.97 ± 1.36 (2) | 3.36 ± 3.78 (4) |

| 5. Participate in care that I do not agree with, but do so because of fears of litigation | 1.19 ± 1.16 (5) | 1.85 ± 1.55 (3) | 3.34 ± 4.31 (5) |

| 6. Be required to care for patients who have unclear or inconsistent treatment plans or who lack goals of care | 1.8 8 ± 1.14 (1) | 1.8 0 ± 1.15 (4) | 4.10 ± 3.88 (1) |

| 7. Performing an operation that I think is not aligned with the patient's values and goals | 0.88 ± 0.89 (7) | 1.58 ± 1.46 (6) | 2.16 ± 2.90 (7) |

| 8. Feeling overwhelmed in hyper-intense conversations | 1.13 ± 1.01 (6) | 1.58 ± 1.30 (6) | 2.66 ± 3.50 (6) |

SD, standard deviation.

Responses (n = 173) scored on an ordinal scale 0 to 4 with higher scores representing greater frequency/intensity.

TABLE 3.

Univariable Analysis of Moral Distress Score With Other Factors

| Group | Moral distress score Median (Q1-Q3) |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 19 (10-35) | |

| Sex | .24 | |

| Male | 18 (8-34) | |

| Female | 20.5 (12.5-38.5) | |

| Years in practice | .07 | |

| <5 | 20 (11-38) | |

| 5-10 | 24 (12-39) | |

| 11-20 | 20.5 (7-39) | |

| >20 | 16 (8-23) | |

| Practice setting | .13 | |

| Academic | 17 (8-33) | |

| Private | 19 (10-39) | |

| Privademic | 23 (15-43) | |

| Level I trauma or comprehensive stroke center | .015 | |

| No | 14 (7-23) | |

| Yes | 20 (10-38) | |

| Call frequency (d/mo) | .17 | |

| <3 (n = 16) | 10.5 (3.5-22.5) | |

| 3-5 (n = 25) | 24 (10-35) | |

| 6-10 (n = 70) | 20 (10-38) | |

| >10 (n = 58) | 19 (8-39) | |

| Futile surgery frequency | <.001 | |

| Never (0/y) | 10 (0-15) | |

| Rare (1/y) | 13 (4-23) | |

| Sometimes (2-5/y) | 22 (12-38) | |

| Often (>5/y) | 41 (19-56) | |

| Burnout (OLBI) | <.001 | |

| Not burned out | 7 (4-19) | |

| At risk | 16 (8.5-21) | |

| Burned out | 23 (4-42) | |

| Burnout (self-assessment) | <.001 | |

| No | 8 (3-16) | |

| Maybe | 22 (14-37) | |

| Yes | 24 (15-43) | |

| Experienced moral distress within past year | <.001 | |

| Strongly disagree | 8 (4-17) | |

| Disagree | 15.5 (8-27) | |

| Agree | 26 (15-49) | |

| Strongly agree | 31 (18-56) | |

| Leaving a position because of moral distress | <.001 | |

| No | 16.5 (7-28) | |

| Have left | 18 (14-22) | |

| Considering | 33 (15-56) |

OLBI, Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. P ≤ .05 is significant.

Univariable analysis identified provider traits and practice characteristics associated with increased survey scores (Table 3). Neurosurgeons with burnout had higher scores than those without burnout (P < .001). Moral distress scores correlated weakly with disengagement (rs = 0.37, P < .001) and moderately with exhaustion (rs = 0.46, P < .001). Multivariable analysis identified futile surgery frequency (P = .003) and burnout (P < .001) as independent correlates of greater moral distress scores. Employment at a level I trauma/comprehensive stroke center was borderline (P = .06) (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Multivariable Regression Analysis of Moral Distress Score With Other Factors

| Group | P value |

|---|---|

| Years in practice | .37 |

| Level I trauma or comprehensive stroke center | .06 |

| Futile surgery frequency (≥2/y) | .003 |

| Burnout (OLBI) | <.001 |

OLBI, Oldenburg Burnout Inventory. P ≤ .05 is significant.

Ten percent of neurosurgeons had left a prior position because of moral distress. Neurosurgeons currently considering leaving their position because of moral distress were 26.6%, a subgroup suffering “moral injury.” “Morally injured” neurosurgeons had higher scores (33, Q1-Q3 16-56) than neurosurgeons who had left positions of moral distress (18, Q1-Q3 14-22) or denied moral distress (16.5, Q1-Q3 7-28) (P < .001). Two important thresholds for moral injury were identified on the moral distress survey. A score of <12 was 85% sensitive (odds ratio [OR]: 0.31, 95% CI 0.13-0.74) for the outcome of contemplating attrition (“morally injured”). A score of >24 was 71% specific (OR: 3.5, 95% CI 1.7-70) for identifying neurosurgeons with moral injury.

Moral Distress Survey Validation

The Messick Unified Theory of Validity was applied to build validity evidence for the moral distress survey.26,27 Content validity was supported by deriving test questions from previously validated moral distress tests (measure of moral distress for the healthcare professional) and through expertise of 2 attending neurosurgeons and 1 palliative care faculty. Two attending neurosurgeons evaluated the response process for question clarity and accuracy. Internal structure of the 8-question survey was assessed with a strong Cronbach alpha score of 0.89. We hypothesis tested the survey because we suspected that moral distress would correlate with respondents contemplating leaving their current position21 and burnout12 with survey results corroborating the hypotheses (Tables 3 and 4).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first systematic evaluation of moral distress among practicing neurosurgeons. The data indicate that over the course of 1 year, half of neurosurgeons experience moral distress. Moreover, two-thirds of neurosurgeons meet criteria for “burnout” and one-fifth perform >5 futile surgeries with moral distress particularly prevalent among these cohorts. We also adapted an existing moral distress measure to make it applicable to high-risk surgical specialties and shortened it for easy application.

On our moral distress survey, the scenario with the highest moral distress composite score was caring for patients lacking clear treatment goals. This scenario ranked first on the composite score because it was the moral distress scenario neurosurgeons encountered most frequently. With 63.3% of Americans lacking an advanced directive,28 existing directives requiring ∼3 days to appear in patient charts,29 physicians and families disagreeing on how to interpret directives,29 and patient surrogates often unclear about patient preferences,30 it is unsurprising that the moral distress scenario most frequently encountered is the critical patient lacking lucid goals of care.

Our results support the hypothesis that a key driver of moral distress among neurosurgeons is nonmedical pressure to perform aggressive surgery, which arises in the aftermath of a patient lacking clear treatment goals. According to the survey, neurosurgical distress is at its greatest intensity when a neurosurgeon feels obligated to perform futile surgery because of family insistence, surrogate indecisiveness, or medicolegal concerns. These constraints may preclude neurosurgeons from enacting a professional value not to operate because healthcare culture is heavily biased toward operating. For example, 55% of Americans state that the “health care system has the responsibility…to offer treatments and spend whatever it takes to extend lives”31 while 75% of neurosurgeons admit viewing patients as “potential lawsuits”32 and 90% admit practicing defensive medicine, such as unnecessary tests and procedures.33 Moreover, physicians receive lower patient satisfaction scores when they refuse unnecessary treatments34 and fear reputational fallout from negative postings on physician-rating websites.35 We suspect it is often practically easier for neurosurgeons who doubt a surgery's benefit to operate for nonmedical reasons than refuse for medical reasons.

Moral distress has real consequences in the form of neurosurgeon attrition. We classified the progression from moral distress to physician attrition as the subset of neurosurgeons whose moral distress has deepened into “moral injury.” Most likely, this transition arises from repeated frustration at the hands of external forces to frustration with oneself at continued participation in a framework that negates professional values or alters neurosurgeon's perceived role as expert provider. In support of the latter, performing as few as 2 futile surgeries per year predicts a higher moral distress score on multivariable analysis, indicating that neurosurgeons can become demoralized from subjugation of professional ethics and independence to practical needs. Worrisomely, our study found that 9.8% of neurosurgeons had left a prior position and 26.6% were considering attrition because of moral distress. Neurosurgeons considering attrition had significantly increased odds (OR 3.5, 95% CI 1.7-70) of a high-risk score on our survey (>24).

Importantly, we found that moral distress scores were highest among neurosurgeons contemplating leaving a position because of moral distress, as compared with neurosurgeons who denied this thought or who had already left a position from moral distress (Table 3). The difference in scores between neurosurgeons who left a position because of moral distress from those contemplating leaving suggests that changing one's injurious environment can heal or mitigate moral injury—but at what price? Although a neurosurgeon experiencing moral injury at 1 job can address it by seeking out another, is this really the best option? Changing jobs carries significant cost to the doctor and hospital alike.36 The clear preference is preventing moral injury from occurring in the first place by alleviating nonmedical pressures to perform futile surgery and by providing appropriate moral support to surgeons employed under more stressful conditions (eg, level I trauma centers). To achieve this, hospital and physician groups should research means to promote the use of advanced directives, educate patient/family expectations as to what quality care entails, advocate for medicolegal reform to protect physicians from suit when they appropriately do not act, improve neurosurgeon understanding of risk, and strengthen institutional rapport between neurosurgeons and hospital administrations so neurosurgeons are supported in their recommendations. The association between moral distress and burnout (P < .001) underscores the magnitude of this need.

Our findings align with the growing literature on physician moral distress, but there are novel findings as well. First, our observation that moral distress arises most dramatically from external forces pressuring unwarranted or nonbeneficial treatment reflects the literature.2,7,9–11,37,38 Surveying the American College of Surgeons, Zimmermann et al38 noted worsened distress when performing surgery to provide added time for coping or fear of “legal consequences…when the patient or family requests surgery.” To these reports, we add the first national survey of the high-acuity subspecialty of neurosurgery. Second, our finding of 9.8% neurosurgical attrition because of moral distress is higher than previous estimates of 5% to 8.5%,9,10 which may reflect neurosurgical practice patterns, but the 26.6% of neurosurgeons contemplating attrition because of moral distress is in keeping with prior physician estimates of 18% to 33%.7-10 Third, our study follows previous studies9,11,12 in emphasizing that moral distress has an association with physician burnout, which we demonstrate to persist on multivariable analysis.

Contrary to previous studies,38,39 we did not find that female physicians were more likely to suffer moral distress. In the literature, other correlations of increased physician moral distress include surgeons and medical subspecialists compared with primary care doctors,9 surgeons compared with emergency department physicians or hospitalists,40 >50% of patients being critical care patients,9 early to mid-career (6-10 years) as opposed to late-career (11-20) practice,9 a negative “ethical climate,”10 uncertainty in ethical aspects of treatment,41 and divergent treatment assessments by colleagues.41 Other studies find that years in practice,37,38 consulting intensivists endorsing surgical intervention38 and time needed to discuss medical management38 do not affect moral distress. With the exception of our univariable analysis associating late career practice (>20 years) with reduced moral distress, our survey did not explore these associations.

Limitations

This study has multiple limitations. First, the response rate was low and may not represent neurosurgeons as a whole. Unfamiliarity with the concept of “moral distress” may have reduced responses, but our response rate (5.8%) aligns with that of recent Congress of Neurological Surgeons member surveys (2.2%-8.0%).42,43 Second, we defined “morally injured” neurosurgeons as those contemplating leaving a position because of moral distress. This definition may be too narrow and underestimate moral injury. Third, although scores of 12 and 24 on the moral distress survey represent important thresholds of moral injury, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding intermediary scores. Fourth, we outlined concepts such as “futile surgery” or “nonbeneficial care” but did not overly define them to allow respondents to interpret these terms as they do in actual practice. Finally, we focused on moral distress and injury in the setting of end-of-life care because of the gravity of the decisions neurosurgeons face in this situation. However, this does not capture the moral distress neurosurgeons encounter in the ambulatory setting where electronic health records,44 understaffing, profit-driven healthcare systems, insurers, and loss of physician autonomy also impede patient care. As such, a renewed emphasis on a collegial environment and practice of meaningful work may offer additional protection against moral distress.45

CONCLUSION

For the first time, moral distress among neurosurgeons has been quantified. In our national survey, we explored that the role end-of-life care plays on the moral distress of neurosurgeons and found that the most common cause of distress is managing the critical patient lacking a clear treatment plan and that the most intense distress comes from external pressure by patient families, surrogate indecision, and medicolegal concerns to perform futile operations. As few as 2 futile surgeries per year can place a neurosurgeon at increased risk of moral distress. These distresses have led approximately 50% of neurosurgeons to report moral distress within the past year, 25% of neurosurgeons to contemplate leaving their current position, and 10% to have left a position while placing neurosurgeons at increased burnout risk. However, we note that the sequelae of moral distress do not have to be permanent. Changing practices can abate distress. To capture neurosurgical distress, we developed and validated a modified moral distress survey and encourage its use in future studies that assess moral distress among neurosurgeons and other high-risk surgical specialties.

Footnotes

Roger B. Davis and Martina Stippler are joint senior authors on this work.

An abstract of these findings was presented as a poster at the October 16-20, 2021, Congress of Neurological Surgeons Annual Meeting in Austin, TX.

CNS Journal Club Podcast and CME Exams available at cns.org/podcasts.

Funding

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst, the Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center, National Center for Research Resources, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health Award UL1 TR002541, and financial contributions from Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Harvard Catalyst, Harvard University and its affiliated academic health care centers or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this article. Dr Buss was paid to review articles on Palliative Care topics for up-to-date, receiving an honorarium of $200 to 300/year. Dr Spiotta receives research support and is a consultant for Penumbra, Stryker, Medtronic, and RapidAI and is a consultant for Terumo.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pauly BM, Varcoe C, Storch J. Framing the issues: moral distress in health care. HEC Forum. 2012;24(1):1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houston S, Casanova MA, Leveille M, et al. The intensity and frequency of moral distress among different healthcare disciplines. J Clin Ethics. 2013;24(2):98-112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zalta AK, Held P. Commentary on the special issue on moral injury: leveraging existing constructs to test the heuristic model of moral injury. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(4):598-599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean W, Talbot SG, Caplan A. Clarifying the language of clinician distress. JAMA. 2020;323(10):923-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grimell J, Nilsson S. An advanced perspective on moral challenges and their health-related outcomes through an integration of the moral distress and moral injury theories. Mil Psychol. 2020;32(6):380-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: a systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychol. 2017;22(1):51-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehead PB, Herbertson RK, Hamric AB, Epstein EG, Fisher JM. Moral distress among healthcare professionals: report of an institution‐wide survey. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47(2):117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodek PM, Wong H, Norena M, et al. Moral distress in intensive care unit professionals is associated with profession, age, and years of experience. J Crit Care. 2016;31(1):178-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Austin CL, Saylor R, Finley PJ. Moral distress in physicians and nurses: impact on professional quality of life and turnover. Psychol Trauma. 2017;9(4):399-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamric AB, Borchers CT, Epstein EG. Development and testing of an instrument to measure moral distress in healthcare professionals. AJOB Prim Res. 2012;3(2):1-9.26137345 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck J, Randall CL, Bassett HK, et al. Moral distress in pediatric residents and pediatric hospitalists: sources and association with burnout. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(8):1198-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fumis RRL, Junqueira Amarante GA, de Fátima Nascimento A, Vieira Junior JM. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7(1):71-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Halbesleben JR, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirom A, Nirel N, Vinokur AD. Overload, autonomy, and burnout as predictors of physicians' quality of care. J Occup Health Psychol. 2006;11(4):328-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balch CM, Freischlag JA, Shanafelt TD. Stress and burnout among surgeons: understanding and managing the syndrome and avoiding the adverse consequences. Arch Surg. 2009;144(4):371-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(11):784-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stern J. Moral Distress in Neurosurgery. New York Times; August 15, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miranda SP, Schaefer KG, Vates GE, Gormley WB, Buss MK. Palliative care and communication training in neurosurgery residency: results of a trainee survey. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(6):1691-1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C, Thacker LR, Hamric AB. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(2):113-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackel CE, Nelton EB, Reynolds RM, Fox WC, Spiotta AM, Stippler M. A scoping review of burnout in neurosurgery. Neurosurgery. 2021;88(5):942-954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peterson U, Demerouti E, Bergström G, Åsberg M, Nygren Å. Work characteristics and sickness absence in burnout and nonburnout groups: a study of Swedish health care workers. Int J Stress Manag. 2008;15(2):153. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldhagen BE, Kingsolver K, Stinnett SS, Rosdahl JA. Stress and burnout in residents: impact of mindfulness-based resilience training. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2015;6:525-532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leung S, Panda M, McIntosh G, et al. Relationship between physician burnout and patient's perception of bedside time spent by physicians. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2021;8(1):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Downing SM, Haladyna TM. Validity and Its Threats Assess in Health Professions Education. Vol 1. Routledge; 2009:41-76. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messick S. The standard problem: meaning and values in measurement and evaluation. Am Psychol. 1975;30(10):955-966. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav KN, Gabler NB, Cooney E, et al. Approximately one in three US adults completes any type of advance directive for end-of-life care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(7):1244-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leder N, Schwarzkopf D, Reinhart K, Witte OW, Pfeifer R, Hartog CS. The validity of advance directives in acute situations: a survey of doctors’ and relatives’ perceptions from an intensive care unit. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2015;112(43):723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):493-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The Regence Foundation. Americans Choose Quality Over Quantity at the End of Life, Crave Deeper Public Discussion of Care Options; 2011. Accessed November 8, 2021. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/new-poll-americans-choose-quality-over-quantity-at-the-end-of-life-crave-deeper-public-discussion-of-care-options-117575453.html. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith TR, Habib A, Rosenow JM, et al. Defensive medicine in neurosurgery: does state-level liability risk matter? Neurosurgery. 2015;76(2):105-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yan SC, Hulou MM, Cote DJ, et al. International defensive medicine in neurosurgery: comparison of Canada, South Africa, and the United States. World Neurosurg. 2016;95:53-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jerant A, Fenton JJ, Kravitz RL, et al. Association of clinician denial of patient requests with patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(1):85-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kemp E, Porter M, III, Albert C, Min KS. Information transparency: examining physicians’ perspectives toward online consumer reviews in the United States. Int J Healthc Manag. 2020;14(4):1050-1056. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen R, Judkins-Cohn T, deVelasco R, et al. Moral distress among healthcare professionals at a health system. JONAS Healthc Law Ethics Regul. 2013;15(3):111-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmermann CJ, Taylor LJ, Tucholka JL, et al. The association between factors promoting non-beneficial surgery and moral distress: A national survey of surgeons. Ann Surg. Published online ahead of print November 17, 2020. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Førde R, Aasland OG. Moral distress among Norwegian doctors. J Med Ethics. 2008;34(7):521-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abbasi M, Nejadsarvari N, Kiani M, et al. Moral distress in physicians practicing in hospitals affiliated to medical sciences universities. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16(10):e18797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mehlis K, Bierwirth E, Laryionava K, et al. High prevalence of moral distress reported by oncologists and oncology nurses in end‐of‐life decision making. Psychooncology. 2018;27(12):2733-2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laldjising E, Sekercan A, Gadjradj PS. Neurosurgeons’ opinions on discussing sexual health among brain tumor patients: room for improvement? J Clin Neurosci. 2021;94:292-297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gadjradj PS, Ghobrial JB, Harhangi BS. Experiences of neurological surgeons with malpractice lawsuits. Neurosurg Focus. 2020;49(5):E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams MS. Misdiagnosis: burnout, moral injury, and implications for the electronic health record. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28(5):1047-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiotta AM, Kalhorn SP, Patel SJ. Letter: how to combat the burnout crisis in neurosurgery? Cathedrals and mentorship. Neurosurgery. 2019;84(4):E257-E258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]