Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The Kobayashi score (KS) is the most widely used tool for predicting intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) resistance in Kawasaki disease (KD). The KS has shown good sensitivity (86%) and specificity (68%) in Japanese children; however, its use is limited outside of Japan. No models accurately predict IVIG resistance of children with KD in the United States. We sought to develop and test a novel scoring system to predict IVIG resistance in hospitalized children with KD.

METHODS

A retrospective chart review was conducted of all children diagnosed with KD from January 2000 to December 2015. Subjects were divided into 2 groups: IVIG susceptible or resistant. Variables that differed between the groups were identified and used to create a “new score” to predict resistance to IVIG. The new score was then compared with the KS and performance characteristics were determined.

RESULTS

A total of 208 subjects were reviewed. White blood cell count, neutrophil percentage, age, and serum albumin were used in the new score with equal weighting. Overall, the new score achieved improved sensitivity (54% vs 26%) and similar specificity (69% vs 74%) compared with the KS in predicting IVIG resistance in hospitalized children diagnosed with KD.

CONCLUSIONS

Predicting IVIG resistance in children diagnosed with KD remains challenging. The KS has low sensitivity in predicting IVIG resistance in children with KD in the United States. The new score resulted in improved sensitivity, but many children with true IVIG resistance may be missed. Further research is needed to improve IVIG resistance prediction.

Keywords: coronary artery aneurysm, intravenous immunoglobulin resistance, Kawasaki disease, Kobayashi score

Introduction

Kawasaki disease (KD) is an acute vasculitis of unknown etiology primarily seen in children younger than 5 years of age.1 In the United States the incidence of KD is 19 cases per 100,000 children, with regional variations.2 Although the incidence is relatively low, if left untreated, children with KD can experience life-threatening coronary artery aneurysms (CAA).1 Additionally, KD is the number 1 cause of acquired heart disease in children in developed countries.3 Therefore, prompt and effective treatment of KD is important.

Initial treatment of KD in children consists of large dose intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) and aspirin. The goal of treatment is to reduce the rate of CAA. In the acute care setting efficacy is measured by a cessation of fever following initial treatment. A majority of children experience cessation of fever following a single dose of IVIG. However, approximately 10% to 20% of children will experience refractory fever and will require additional treatment with IVIG or alternative anti-inflammatory therapy.3 These children are considered IVIG resistant and have a higher chance of developing CAA.3

In Japan, 3 scoring systems exist and include the Kobayashi, Egami, and Sano scores.4–6 The Kobayashi score (KS) (Table 1) is the most widely used scoring system in Japan, with a reported sensitivity and specificity of 86% and 68%, respectively.5 However, these scoring systems have limited utility outside of Japan. Japan's homogenous population is thought to be a contributing factor for decreased sensitivity and/or specificity of scores developed in Japan and used in other countries. Risk scoring systems such as the KS have shown a low sensitivity (33%) and moderate-to-high specificity (87%) in mixed ethnicity children of North America.7 Currently, no reliable scoring system exists for prediction of IVIG resistance in children with KD in the United States.

Table 1.

The Kobayashi Score

| Variable | Threshold | Points* |

|---|---|---|

| Serum sodium, mEq/L | ≤133 | 2 |

| Days of illness at initial treatment† | ≤4 | 2 |

| AST, IU/L | ≥100 | 2 |

| Neutrophil, % | ≥80 | 2 |

| CRP, mg/dL | ≥10 | 1 |

| Age, mo | ≤12 | 1 |

| Platelet count, ×104/mm3 | ≤30 | 1 |

AST, aspartate transaminase; CRP, C-reactive protein; IVIG, intravenous immunoglobulin

* High Risk defined as a score ≥4 points.

† Days of fever prior to IVIG administration.

Multiple studies in the past have explored predictive measures for IVIG resistance in children with KD.8–14 In China, a retrospective analysis of children with KD admitted to a hospital showed age, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, mean platelet volume, and serum albumin prior to IVIG treatment as helpful for prediction of IVIG resistance in children.15 A study from Israel reported that echocardiogram findings before day 5 of fever had high sensitivity in identifying IVIG non-responders in patients with KD.16 These studies have not led to validated novel scoring systems, particularly of applicability to heterogenous populations of North America. The purpose of this current study was to develop and test a novel scoring system to predict IVIG resistance in hospitalized children with KD.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective medical records review of all cases involving children with a discharge diagnosis of KD at the Women and Children's Hospital of Buffalo between January 2000 and December 2015.17 Subjects were further screened to determine if they met the 2017 American Heart Association's criteria for diagnosis of KD.3 Serum albumin, aspartate transaminase (AST), serum calcium, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, hematocrit, hemoglobin, neutrophil percentage, platelet count, serum potassium, red blood cell count, serum sodium, and white blood cell (WBC) count collected within 48 hours of admission were used for analysis.

Included cases were divided into 2 groups: IVIG susceptible or resistant. Subjects were deemed to be IVIG resistant if they required more than a single dose of IVIG. The specific cutoff used was 2.5 g/kg IVIG as it is common practice to use the full contents of vials of IVIG, which often leads to slightly higher than 2 g/kg dosing. Variables that were largely available in a major portion of cases were used to compare the 2 groups. For those variables that showed significant differences (p ≤ 0.05), receiver operator curves (ROCs) were used to determine the optimal threshold of each variable that resulted in the greatest sensitivity and specificity for predicting IVIG resistance. These variables were then used to create a “new score.” The ROC value marking the highest sensitivity and specificity for predicting IVIG resistance in the new score was chosen to be the threshold. Each variable in the new score was assigned equal weighting as differences were small and there was no biological support to weight any category higher than the other. The new score and the KS were applied to the same cohort of children and the sensitivity and specificity of each scoring tool were compared.

As an ultimate goal is to create a more universal scoring system applicable across geographical locations, the new score was tested in a KD data set obtained from Fujian, China and Boston, Massachusetts. The data set from China consisted of 644 patients with confirmed KD and included laboratory values, demographics, and whether the patient had IVIG resistance.18 The Boston data set contained 97 children with confirmed KD.19 Both the KS and the new score were applied to these KD data sets, and the sensitivity and specificity of each scoring tool were determined.

All statistical analysis were performed using Graph-Pad Prism version 8.0.0 (2021 GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). The threshold values of the new score were chosen to optimize both sensitivity and specificity, known as the maximum likelihood ratio, which assesses the goodness of fit. When tests for statistical significance were required, α was set to 0.05. T tests were used to analyze continuous variables and either the χ2 or Fisher exact test was used to analyze categorical variables.

Results

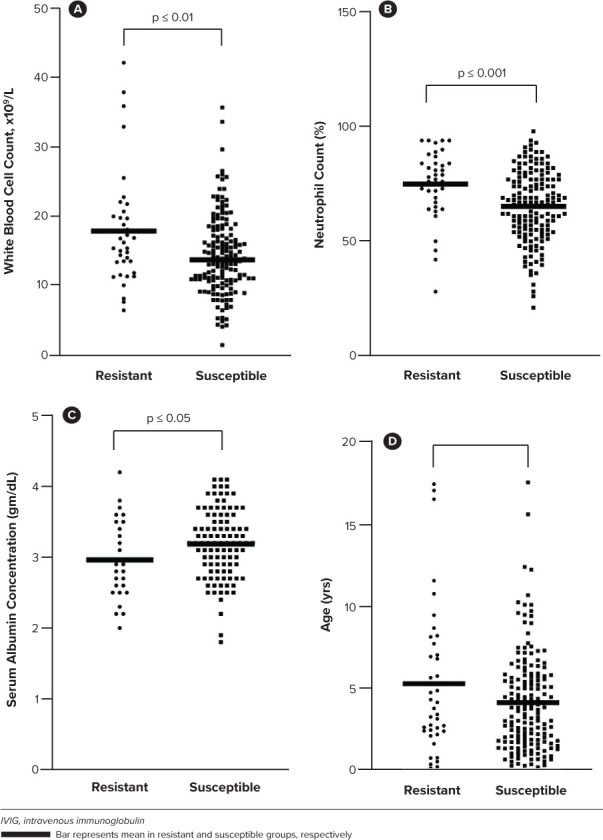

A total of 263 cases were reviewed with 208 cases meeting inclusion criteria. The primary reason for exclusion was admission for an unrelated diagnoses. Characteristics of included cases are summarized in Table 2. Of the 208 cases, 39 were determined to be IVIG resistant. Four variables demonstrated significant or near significant differences between the IVIG susceptible and resistant groups: WBC count (p = 0.0028), neutrophil percentage (p = 0.0008), age (years) (p = 0.0544), and serum albumin concentration (p = 0.0449) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) Resistant and Susceptible Cases *

| Variable | Data Presented as Mean | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IVIG Resistant (n = 39) | IVIG Susceptible (n = 169) | ||

| Age, yr | 5.3 | 4.1 | 0.05 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 3 | 3.2 | 0.04 |

| AST, IU/L | 51 | 48.7 | 0.81 |

| Serum calcium, mg/dL | 9 | 9.1 | 0.27 |

| CRP, mg/L | 117.3 | 91.1 | 0.16 |

| ESR, mm/hr | 65.5 | 68.8 | 0.61 |

| Hematocrit, % | 33.2 | 33.2 | 0.97 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 11.4 | 11.3 | 0.81 |

| Neutrophil, % | 75 | 65.3 | 0.0008 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 377 | 416 | 0.22 |

| Serum potassium, mEq/L | 379 | 415.3 | 0.26 |

| RBC, ×1012/L | 4 | 4.1 | 0.55 |

| Serum sodium, mEq/L | 134.4 | 134.7 | 0.62 |

| WBC, ×109/L | 17.7 | 14.2 | 0.04 |

| Sex† | |||

| Male | 26 | 107 | 0.85 |

| Female | 13 | 62 | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 31 | 117 | 0.34 |

| Black | 6 | 31 | |

| Other | 2 | 21 | |

AST, aspartate transaminase; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell

* All variables used in analysis were obtained within 48 hours of admission.

† data presented as n

Figure 1.

Comparisons of variables that displayed statistical significance or near statistical significance between the intravenous immunoglobulin resistant and susceptible patients.

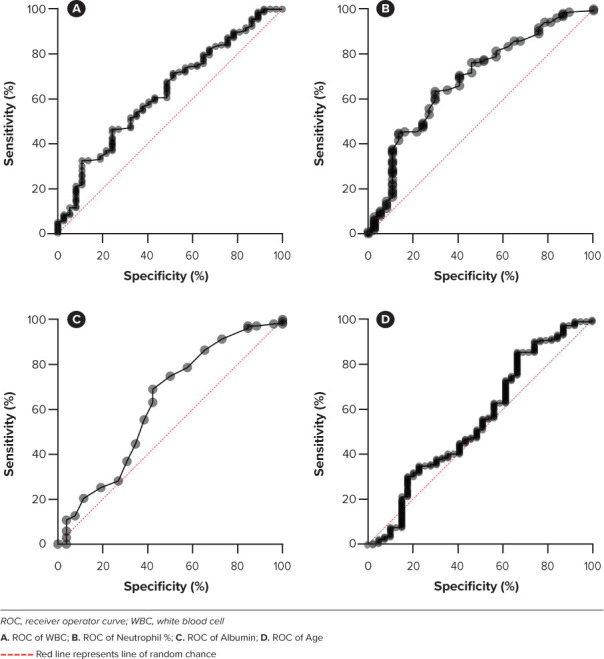

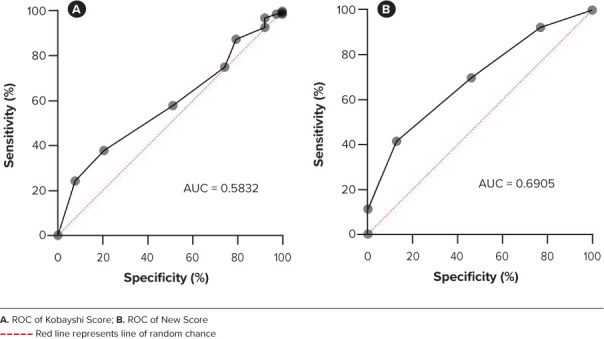

The ROCs for each of the 4 variables identified appear in Figure 2. The thresholds for each variable were as follows: WBC greater than 11 × 109 cells/L, age greater than 2 years, neutrophil percentage greater than 72, and serum albumin concentration less than 3 g/dL. Each variable was included in the new score and were assigned 1 point (Table 3). Alternative weighting for variables in the new score to optimize sensitivity or specificity was not attempted. Differences between the IVIG susceptible and resistant group were small, and we felt pursuit of alternative weights for variables was not justified given the scope of our study. A score greater than or equal to 3 on the new score was determined to be high risk for IVIG resistance. The threshold for all the variables in the new score were determined based off the ROCs generated for each. The cutoff for each variable yielded the highest sensitivity and specificity values. The cutoff for the new score was determined to be 3 based off the ROC generated from the composite score. At this value, the new score displayed the highest sensitivity and specificity in predicting IVIG resistance in the Western New York (WNY) cohort. The KS score demonstrated a sensitivity of 26% and specificity of 74% in the WNY cohort. The new score demonstrated an improved sensitivity of 54% and similar specificity at 69%. The ROCs for the new score and the KS when applied to this cohort of cases are displayed in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Receiver operator curves for variables included in the new score using the Western New York patient data set (N = 208).

Table 3.

The New Score For Predicting Intravenous Immunoglobulin Resistance

| Variable | Threshold* | Points† |

|---|---|---|

| Total WBC, ×109/L | >11 | 1 |

| Age, yr | >2 | 1 |

| Total neutrophil count, % | >72 | 1 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | <3 | 1 |

WBC, white blood cell

* Threshold for each variable displaying highest sensitivity and specificity for identification of Kawasaki disease.

† One point for each variable that falls above or below listed threshold, with a high risk defined as a score ≥ 3 points.

Figure 3.

The Kobayashi score and the new score applied to the Western New York patient data set and the resulting receiver operator curves (ROCs) and their respective areas under the curve (AUC).

A score that is applicable across the world is of more interest than a score limited to certain geographical locations. To this end, we tested the new score in a data set of children diagnosed with KD from Fujian, China and Boston, Massachusetts. The new score demonstrated a sensitivity of 27% and specificity of 78% in the Chinese data set. Similarly, the KS had a sensitivity of 36% and specificity of 50% in this data set. The new score demonstrated a sensitivity of 40% and specificity of 73% in the Boston data set, whereas the KS had a sensitivity of 0% and specificity of 99%.

Discussion

The new score had an improved sensitivity and similar specificity when compared with the KS in predicting IVIG resistance in a cohort of children diagnosed with KD in the WNY area. The application of the new score in a data set from China resulted in decreased sensitivity and a moderate-to-high specificity. The new score did perform significantly better in the Boston data set, showing improved sensitivity and moderately decreased specificity when compared with the KS. These findings underscore the regional variations that exist with KD and the limitations with applying a risk prediction tool to a population outside of the one it was derived from. Similar to the application of the KS to patients outside of Japan, the new score demonstrated variable performance in predicting IVIG resistance in children from China and Boston. However, the new score may be more useful, compared with the KS, in predicting IVIG resistance in children diagnosed with KD in heterogenous North American populations.

Prediction of IVIG resistance in children diagnosed with KD is challenging. The new score system resulted in improved sensitivity (54% vs 26%) with comparable specificity (69% vs 74%) compared with traditional methods (i.e., the KS). The new score may accurately identify IVIG resistance in more children diagnosed with KD in WNY compared with the KS; however, neither system is highly sensitive. These data reflect the complex ethnical and geographic variations that exist in children with KD.

When comparing the new score and the KS, half of the variables in the new score are present in the KS; the variables in both scores are neutrophil percentage and patient age. An increase in neutrophil percentage is a ubiquitous response observed in nearly all types of inflammation and supports the theory of KD being of pathogenic origin.1 Several studies performed in East Asia have shown a relationship between serum sodium concentrations and CAA or IVIG resistance.8–10 Our study found no association between serum sodium concentrations and IVIG resistance. Decreases in the serum sodium may only be observed in patients with severe inflammation and those who develop CAA.8 All patients in our study were discharged after their course of treatment, with the exception of 1 patient who died due to CAA. It is possible that our cohort of patients could have presented with milder inflammation, resulting in no significant changes in serum sodium concentrations between IVIG resistant and susceptible groups.

Patient age is a factor taken into consideration in nearly all scores, including the KS and Egami score.4,5 There was a non-significant difference in age between IVIG resistant and susceptible patients in our cohort. Furthermore, our data showed the opposite of the KS score when using age to determine IVIG resistance. Our analyses showed that older patients in WNY were more likely to develop IVIG resistance, whereas younger patients in Japan are more likely to develop IVIG resistance.1,5 Children younger than the age of 6 months have been known to present with incomplete or atypical KD and the diagnosis can be more difficult.11 A lesser understanding of KD in populations outside of Japan and difficulty in diagnosing infants could have resulted in skewed data. Serum albumin concentration, AST, and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values have been associated with IVIG unresponsiveness in patients with KD.12 Our analyses only showed the serum albumin to be significantly different between the IVIG resistant and IVIG susceptible groups. The mechanism of liver abnormality in patients with KD remains unclear.13,14 But the ongoing inflammatory processes of KD may have an effect on liver function, therefore causing increases in liver function measurements such as AST, ALT, serum bilirubin, and decreases in serum albumin.13,14 It is possible that the ethnic heterogeneity of children who reside in the WNY area, as compared with Japan, could also be a factor contributing to the differences that exist in the variables included in the new score.

Few studies have looked at IVIG resistant KD in the United States. A retrospective study of patients with KD in 43 hospitals across the United States attempted to characterize the incidence of IVIG resistant KD and risk factors for resistance. No clinical prediction model was generated from this study, but the group noted variations in evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of IVIG resistant KD due to differing institutional practices.20 Our study contributes to the literature by exploring variables that may assist with the prediction of IVIG resistance in children in the United States, specifically the WNY area. Further research is needed to determine if the new score is applicable in regions of the United States outside of the WNY area.

To our knowledge, this was the first study to investigate a new risk prediction tool for IVIG resistance in children diagnosed with KD in the United States. Our study, although small, highlights the challenges with predicting IVIG resistance and reiterates common themes from previous studies. For example, some variables included in the new score were similar to those in the KS supporting the fact that there are some clinical features of KD found in patients around the world.15 Additionally, application of the new score in a data set of children with KD from China reinforced the heterogeneity of KD and the need for regional-specific IVIG resistance prediction models.

Our study did have limitations that are important to consider. For included cases, laboratory values that were analyzed were restricted to the first 48 hours of the child being admitted to the hospital. The rationale for this was to minimize including laboratory values that may have drastically changed due to treatment. However, due to the retrospective nature of this study, this may have led to selection bias. Similarly, this was a study conducted at 1 center, which could have also contributed to selection bias. Echocardiogram findings are an important variable to consider in the diagnosis and prognosis of children with KD and unfortunately, we did not have access to these tests and therefore they were not included.

Future studies should be aimed at identifying an expanded number of variables predictive of IVIG resistance in children across the United States. Novel risk prediction should include clinical variables but also climate, ethnicity, and socioeconomic variables that may vary significantly across regions of the United States. Analysis of biomarkers, such as interleurkin-6, may also be helpful in improving future clinical prediction models.21 Widely performed diagnostic tests such as echocardiograms may also prove useful if incorporated into prediction models.16

Conclusion

Predicting IVIG resistance in children remains challenging. The KS has low sensitivity in predicting IVIG resistance in children with KD in the United States. The new score resulted in improved sensitivity in the WNY region, but many children with true IVIG resistance may be missed. Further research is needed to improve the prediction of IVIG resistance in children diagnosed with KD in the United States.

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results were presented at the Virtual Annual Meeting of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in October 2021.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- CAA

coronary artery aneurysm

- IVIG

intravenous immunoglobulin

- KD

Kawasaki disease

- KS

Kobayashi score

- ROC

receiver operator curve

- WBC

white blood cell

- WNY

Western New York

Funding Statement

Disclosures. The authors declare no financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

Disclosures. The authors declare no conflicts.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national guidelines on human experimentation and has been approved by the appropriate committees at our institution. The project was exempt from informed consent.

References

- 1.Rife E, Gedalia A. Kawasaki disease: an update. Curr Rheumatol Rep . 2020;22(10):75. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00941-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uehara R, Belay ED. Epidemiology of Kawasaki disease in Asia, Europe, and the United States. J Epidemiol . 2012;22(2):79–85. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20110131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation . 2017;135(17):e927–e999. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egami K, Muta H, Ishii M et al. Prediction of resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in patients with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr . 2006;149(2):237–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kobayashi T, Inoue Y, Takeuchi K et al. Prediction of intravenous immunoglobulin unresponsiveness in patients with Kawasaki disease. Circulation . 2006;113(22):2606–2612. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.592865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sano T, Kurotobi S, Matsuzaki K et al. Prediction of non-responsiveness to standard high-dose gamma-globulin therapy in patients with acute Kawasaki disease before starting initial treatment. Eur J Pediatr . 2007;166(2):131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0223-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sleeper LA, Minich LL, McCrindle BM et al. Evaluation of Kawasaki disease risk-scoring systems for intravenous immunoglobulin resistance. J Pediatr . 2011;158(5):831–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee IR, Park SJ, Oh JI et al. Hyponatremia may reflect severe inflammation in children with Kawasaki disease. Childhood Kidney Diseases . 2015;19(2):159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki H, Takeuchi T, Minami T et al. Water retention in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease: relationship between oedema and the development of coronary arterial lesions. Eur J Pediatr . 2003;162(12):856–859. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1326-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koyanagi H, Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H. Lower level of serum potassium and higher level of C-reactive protein as an independent risk factor for giant aneurysms in Kawasaki disease. Acta Paediatr . 1998;87(1):32–36. doi: 10.1080/08035259850157831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singh S, Agarwal S, Bhattad S et al. Kawasaki disease in infants below 6 months: a clinical conundrum? Int J Rheum Dis . 2016;19(9):924–928. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baek JY, Song MS. Meta-analysis of factors predicting resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in patients with Kawasaki disease. Korean J Pediatr . 2016;59(2):80–90. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2016.59.2.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eladawy M, Dominguez SR, Anderson MS, Glodé MP. Abnormal liver panel in acute Kawasaki disease. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2011;30(2):141–144. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f6fe2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu L, Yin W, Wang R et al. The prognostic role of abnormal liver function in IVIG unresponsiveness in Kawasaki disease: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Res . 2016;65(2):161–168. doi: 10.1007/s00011-015-0900-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu S, Liao Y, Sun Y et al. Prediction of intravenous immunoglobulin resistance in Kawasaki disease in children. World J Pediatr . 2020;16(6):607–613. doi: 10.1007/s12519-020-00348-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bar-Meir M, Kalisky I, Schwartz A, et al. Israeli Kawasaki Group Prediction of resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin in children with Kawasaki disease. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc . 2018;7(1):25–29. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piw075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang A, Delmerico AM, Hicar MD. Spatiotemporal analysis and epidemiology of Kawasaki disease in Western New York: a 16-year review of cases presenting to a single tertiary care center. Pediatr Infect Dis J . 2019;38(6):582–588. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang T, Liu G, Lin H. A machine learning approach to predict intravenous immunoglobulin resistance in Kawasaki disease patients: a study based on a Southeast China population [published correction appears in PLoS One 2021;16(6):e0253675] PLoS One . 2020;15(8):e0237321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0237321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newburger JW, Sleeper LA, McCrindle BW et al. Randomized trial of pulsed corticosteroid therapy for primary treatment of Kawasaki disease. N Engl J Med . 2007;356(7):663–675. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moffett BS, Syblik D, Denfield S et al. Epidemiology of immunoglobulin resistant Kawasaki disease: results from a large, national database. Pediatr Cardiol . 2015;36(2):374–378. doi: 10.1007/s00246-014-1016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato S, Kawashima H, Kashiwagi Y, Hoshika A. Inflammatory cytokines as predictors of resistance to intravenous immunoglobulin therapy in Kawasaki disease patients. Int J Rheum Dis . 2013;16(2):168–172. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]