Abstract

Appropriate ventilation may help in the mitigation of airborne transmission of viruses in buildings. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the ventilation rate was determined depending on the number of occupants, net floor area, and building pollution category. Increasing the ventilation rate, the risk of cross infections may be reduced substantially. Ventilation effectiveness provides information about the airflow capacity to remove the pollutants from the breathing zone of occupants. In the present study, the interrelation between ventilation effectiveness and the air temperature was analysed in the case of different isothermal balanced ventilation strategies. Mixing, displacement, and personalized ventilation were investigated in a test room, measuring the CO2 concentration, and having the air exhaust positions above the floor and under the ceiling. The air temperatures were set between 21 °C and 26 °C. To illustrate the airflow patterns numerical simulations have been carried out. It was shown that there are significant differences between ventilation effectiveness depending on the air temperature and ventilation strategy. In most cases, the ventilation effectiveness was higher when the air exhaust was positioned under the ceiling. For investigated air temperatures, differences of even 20%–40% have been determined between ventilation effectiveness values in the case of a certain ventilation strategy.

Keywords: COVID-19, Airborne transmission, Ventilation strategy, Ventilation effectiveness, CO2 concentration

Nomenclature and list of abbreviations

- IEQ

indoor environment quality

- MV

mixing ventilation

- DV

displacement ventilation

- PV-FS

personalized ventilation, front air supply

- PV-LS

personalized ventilation, lateral air supply

- AF

air exhaust – air terminal device located above the floor

- UC

air exhaust – air terminal device located under the ceiling

- ATD

air terminal device;

- ρ

air density, [kg/m3]

- η

dynamic viscosity, [kg/m⋅s]

- R0

basic reproduction number

- cex

is the CO2 concentration in the extracted air, [ppm]

- ci

is the CO2 concentration in the indoor air, [ppm]

- cs

is the CO2 concentration in the supplied air, [ppm]

- ε

ventilation effectiveness, [−]

- tex

is the temperature in the extracted air, [°C]

- ti

is the temperature in the indoor air, [°C]

- ts

is the temperature in the supplied air, [°C]

- N

number of data

- SD

standard deviation

1. Introduction

In the building sector, energy saving was in the focus of researchers and developers in the last decades. In the European Union, energy performance directives have been elaborated and strict thermo-physical and air tightness requirements were established regarding external building elements and the whole building envelope. Nevertheless, appropriate indoor air quality had to be provided to assure the occupants’ well-being. The suggested ventilation rates are given in different standards in the function of the building comfort category. However, the COVID-19 pandemic enlightens that the question of ventilation in buildings cannot be solved and closed providing only a certain amount of ventilation rate. Morawska and Milton drew the attention of designers to the use of preventive measures to mitigate the airborne transmission of coronavirus, [1]. Besides hand hygiene and environmental cleaning and disinfection [2], one of the most important measures is to increase the existing ventilation rates (outdoor air change rate) and enhance ventilation effectiveness, [3]. Certainly, increasing the ventilation rate, the energy used for ventilation will increase as well. It has to be noted that the relation between ventilation rate and ventilation effectiveness is not linear, [4]. It was shown that at low airflow rates the experimentally determined ventilation effectiveness is higher than the calculated theoretical value while in the case of high ventilation rates the measured effectiveness is around the calculated value. Besides the high ventilation effectiveness, the increase of the social distance can help in reducing the infection risk, [5]. Employees were encouraged to perform remote work, reducing the number of occupants in buildings. Cross infection depends also on the airway exposure to indoor particulate contaminants, [6]. Numerical simulations proved that the cross-infection can be reduced by choosing an appropriate ventilation strategy. The obtained airflow pattern strongly influences the airborne transmission of viruses in a closed space. In the case of existing ventilation systems, a newly developed air jet control box can help to obtain the most appropriate airflow pattern, [7]. Previously, mixing of supplied fresh air with the polluted room air was highly expected. Now, to reduce airborne transmission, the mixing between fresh (outdoor) air and room air should be avoided or reduced as much as possible. Melikov stated that in ventilation design practice a paradigm shift should be realized: from space focused to occupant-focused ventilation [8]. The developed air jet control box significantly reduces the induction rate of the supplied airflow, [7]. The ventilation system should provide clean air in the breathing zone not only to dilute the contaminants, [9]. Contaminants have to leave the occupational zone and never return. The obtained airflow pattern in a closed space depends on a series of factors, such as the ventilation system type, air terminal devices, room geometry, ventilation flow rate, air temperatures, etc. To identify the interrelation between influencing factors and ventilation effectiveness, experimental investigations are needed in controlled environments. Carbon dioxide concentration might be used as an indicator of the ventilation process [10]. Qian et al. analysed the major characteristics of the enclosed spaces in which the coronavirus outbreaks were reported, [11]. They concluded that the current ventilation rate standards do not consider infection control. Pan et al. formulated anti-epidemic design and operation strategies for building services systems, [12]. They claimed larger volumes of fresh air in buildings and adjustable fans with variable speeds. The strong correlation between infection risk and ventilation rates was demonstrated by Li and Tang either, [13]. They performed onsite measurements of CO2 concentrations and attempted to determine the infection probability in a hospital. It was shown that the infection probability is much lower at high ventilation rates. The infection probability depends on the adopted operation strategy of the ventilation systems as well. Pereira and Ramos analysed the impact of mechanical ventilation operation strategies on indoor CO2 concentration and air exchange rates in residential buildings, [14]. They concluded that intermittent ventilation should not be adopted, and airflow rate optimisation should be chosen instead depending on the occupancy profile. Avoiding intermittent ventilation was recommended by Melikov et al. as well, [15]. Moreover, they proposed to ask occupants to leave the room 10–20 min every hour. Zhang et al. proposed an occupancy-aided ventilation strategy, optimizing the occupancy load and occupancy flexibility to reduce airborne infection risk and minimize the loss of work productivity, [16]. Natural ventilation shows advantages and disadvantages as well. Opening the windows quite high air change rates can be obtained, keeping the infection probability lower than 1%, [17]. However, the process is strongly influenced by temperature differences and wind velocity. Moreover, important differences between the air change rates occur providing single-side or cross ventilation strategy. In the case of single-side natural ventilation, Wu and Niu proposed mechanical exhaust to increase the air change rate and reduce the contamination risk, [18]. In cold seasons or cold climates, natural ventilation may lead to a substantial decrease in the indoor air temperature affecting thermal comfort. Nevertheless, even in Mediterranean climates in naturally ventilated classrooms the indoor CO2 concentrations may exceed 2000 ppm, [19]. When the windows are opened by occupants depending on their perception of the indoor air quality, the obtained air change rates were lower than 1.0 h−1, [20]. In the case of time scheduled opening air change rates around 1.0 h−1 were obtained. These air change rates are far from the expected fresh (outdoor) air supply rates. Lu et al. have shown that CO2 monitoring systems can help in providing the necessary ventilation rates and natural ventilation may be used in parallel with mechanical ventilation systems adjusting properly the operation, [21]. It can be concluded that natural ventilation can help in the reduction of infection risk and appropriate indoor air quality but the ventilation rate hardly can be controlled, so in cold seasons thermal discomfort problems may likely occur or the energy used for heating will increase substantially.

Mechanical ventilation systems can provide the fresh air demand, but the ventilation effectiveness depends on a series of parameters. Using enhanced air filtering, purification and cleaning techniques the required indoor air quality can be assured. Elsaid and Ahmed proposed adjusting the exhaust air amount higher than supplied air amount (providing a negative pressure of at least 2.5 Pa in the ventilated closed space), [22]. On the other hand, having a negative pressure in a room, the polluted air from other rooms may enter the ventilated space. As was stated by Wu et al. even the transmission of viruses induced by air infiltration cannot be neglected, [23]. Besides the position of air supply and exhaust, the obtained ventilation performance and effectiveness depend on the type of installed air terminal device as well, [4,7,24,25]. Xu and Liu drew attention to personalized ventilation systems, which may serve as a possible solution in some building types to reduce the infection probability, [26]. It was already shown that personalized ventilation systems provide higher ventilation effectiveness values in the breathing zone even in the case of screened working desks, [4].

Summarizing the literature review, it can be stated that the ventilation systems have to fulfil (at least) two requirements which have “vectorially” opposite directions: minimization of airborne transmission of viruses (high air change rates) and minimization of energy consumption (low air exchange rates). The most important is to provide clean air in the breathing zone of occupants without affecting the thermal comfort perception. To find the optimal solution a series of parameters have to be analysed: ventilation strategy, air supply and exhaust types and positions, ventilation rate, air temperatures, room dimensions, number of occupants, and distance between occupants.

Our research aimed to study the effect of air temperature on the local ventilation effectiveness in the breathing zone, having different isothermal ventilation strategies. A high number of studies analysed the ventilation effectiveness for different ventilation strategies, but the dependence of the ventilation effectiveness on the air temperature in the case of isothermal ventilation was not studied yet. Nowadays, the focus is on the reduction of infection probability, but the required thermal comfort parameters have to be assured, so even at high air change rates, the discomfort caused by draught has to be avoided. In large open offices, the number of occupants has to be reduced to fulfil the required social distance between employees. However, by providing directly fresh air in the breathing zone with appropriate airflow patterns, airborne transmission can be reduced efficiently. The removal of contaminants from the occupants’ breathing zone is crucial. Avoiding or reducing the mixing of the supplied fresh air with polluted indoor air is crucial as well. We aimed to investigate the ventilation effectiveness in the case of isothermal ventilation by setting different air temperatures and adopting different ventilation strategies. To the best of our knowledge, there is no information about the variation of local ventilation effectiveness with temperature in the case of isothermal ventilation, even though the set point temperature in buildings is different in cold, warm and transition periods of the year. In the case of isothermal ventilation, the ventilation effectiveness is assumed constant. But, can be the air temperature kept constant along the whole air path (supply-breathing zone-exhaust) in practice? If the temperature of the airflow is not constant, what happens with the contaminant removal in the breathing zone? Our hypothesis was, that the temperature is not constant despite the goal and efforts to provide isothermal ventilation. It was presumed that the effectiveness (contaminant removal efficiency in the breathing zone) is not constant even though the ventilation rate and the supply temperature are constant and equal to the indoor set point temperature. The ventilation effectiveness can be analysed based on CO2 concentration measurements, [10,21]. Eight different ventilation strategies were analysed.

To meet the mitigation efforts of the airborne transmission of viruses in closed spaces is essential to identify all parameters which influence the ventilation effectiveness since this is one of the key factors in the air cleaning process of the occupants’ breathing zone.

The performed research work is summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Summary of the performed work.

| Tested ventilation strategies (eight modes) | MV AF, MV UC, DV AF, DV UC, PV-FS AF, PV-FS UC, PV-LS AF, PV-LS UC |

|---|---|

| Air temperatures (six values) | 21 °C; 22 °C; 23 °C; 24 °C; 25 °C; 26 °C. |

| Measured parameters | local turbulence intensity (head level) |

| air temperatures (supply, breathing zone, exhaust) | |

| relative humidity (supply, breathing zone, exhaust) | |

| globe temperature (head level) | |

| air velocities (in six points for calibration of the simulation model for each ventilation strategy) | |

| supplied and exhausted airflow rates | |

| CO2 concentrations (supply, breathing zone, exhaust) | |

| Calculated parameters | mean value of local ventilation effectiveness (48 cases) and standard deviation |

| Simulations | airflow patterns in the test room |

| Statistics | significance analysis of the differences between the obtained ventilation effectiveness (for different ventilation strategies at a certain temperature and for different temperatures in the case of a certain ventilation strategy) |

| Uncertainties | air temperatures and CO2 concentrations in the supplied, indoor and exhausted air |

2. Methods

The ventilation effectiveness was analysed in the case of a balanced mechanical ventilation system with an isothermal air supply in the case of mixing (MV), displacement (DV) and personalized ventilation (PV) systems. For all air supply strategies, two exhaust positions were tested: under the ceiling (UC) and above the floor (AF). In the analysis of ventilation effectiveness, CO2 was used as a tracer gas. The CO2 source in all tested cases was the same person sitting in the middle of the room at a desk. The CO2 emission of the occupant at 13.4 l/h (178 cm, 72 kg) was determined previously, [4]. The CO2 concentration was measured in the supplied airflow, in the exhausted airflow and in the breathing zone – 25 cm above the desk leaf (1.0 m above the floor), 60 cm from the right side of the desk and 40 cm from the front of the desk. One measurement lasted 60 min and the CO2 concentrations were gathered every 5.0 min. The supplied airflow rate was set to 30 m3/h (ACH = 1.3 h−1) in the case of mixing and displacement ventilations, while in the case of personalized ventilation 15 m3/h (0.65 h−1). Measurements were carried out for an isothermal balanced ventilation strategy having the indoor and supply air temperatures set to 21 °C, 22 °C, 23 °C, 24 °C, 25 °C and 26 °C (from January to June 2022). The relative humidity varies between 40% and 50% (according to Ref. [22] settings below 21 °C and 40% relative humidity should be avoided). The activity level was considered 1.2 met (office work sitting at the desk) and the occupant was allowed to change clothing depending on the thermal comfort needs. The air velocity, local turbulence intensity and draught rate were measured with TESTO 480 instrument (180 s) at the head level of the occupant sitting at the table and in other five locations to validate the simulation model.

2.1. Test room

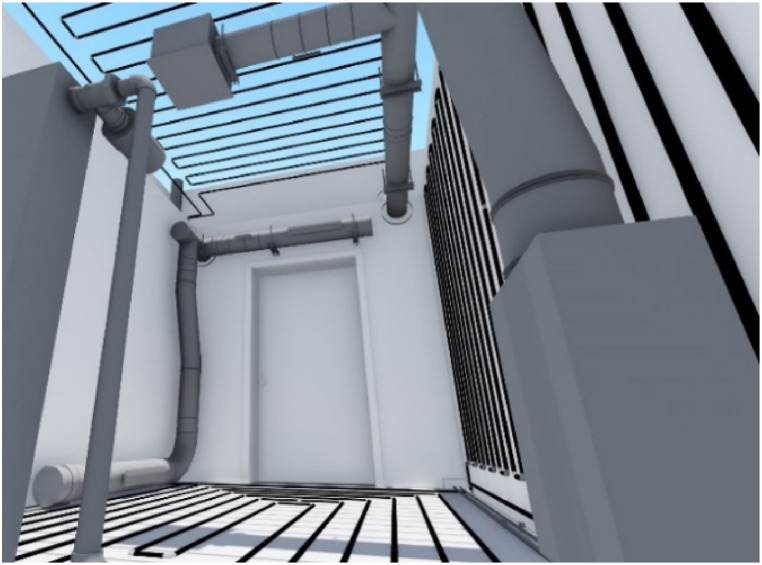

Measurements were carried out in the Indoor Environment Quality (IEQ) laboratory of the University of Debrecen. The test room is placed in a well-sealed adiabatic chamber which is constructed from polyurethane (PUR) 15 cm thick sandwich panels. The adiabatic room itself is placed indoors in a well-insulated and airtight building built in 2013. The internal dimensions of the test room are: 2.49 m in width, 3.65 m in length and 2.56 m in height. In the test room floor-, wall-, ceiling and radiator heating is possible (Fig. 1 ). Wall, floor and ceiling cooling is possible as well. Furthermore, in the space between the adiabatic room and test room temperatures between −15 °C and +35 °C can be set.

Fig. 1.

Test room.

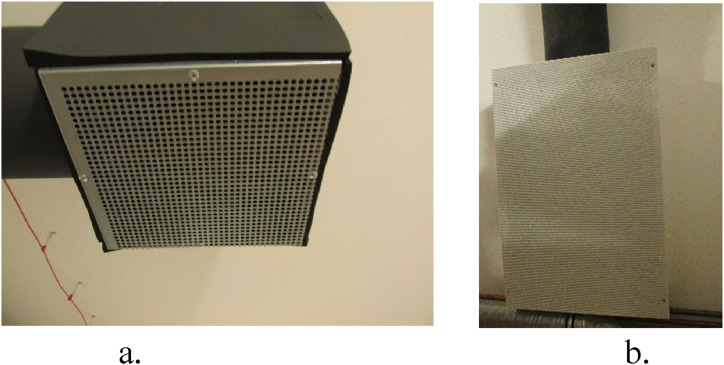

In the test room, both the air temperature and mean radiant temperature can be precisely controlled. The diffuse mixing ventilation (MV) is realized with the air terminal device (ATD) fixed in the middle of the ceiling (Fig. 2 a), while displacement ventilation (DV) is possible by having the ATD placed on the left side corner above the floor (on the opposite side of the room assuming the entrance door) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Air terminal devices used for diffuse (a) and displacement (b) ventilation.

The exhaust ATDs are placed above the floor (AF - Fig. 3 a) and under the ceiling (UC - Fig. 3b) are similar. The ventilation strategy (the change between the exhaust modes) can be set using butterfly valves installed in the exhaust branch of air ducts. The AF exhaust ATD is fixed on the right side wall (taking into account the entrance door) in the corner of the test room (diagonally opposite to the DV ATD), while the UC exhaust ATD is fixed above the entrance door (Fig. 1). The AF ATD grill is vertical, while the UC ATD grill is inclined with 45°.

Fig. 3.

Exhaust elements: AF (a) and UC (b).

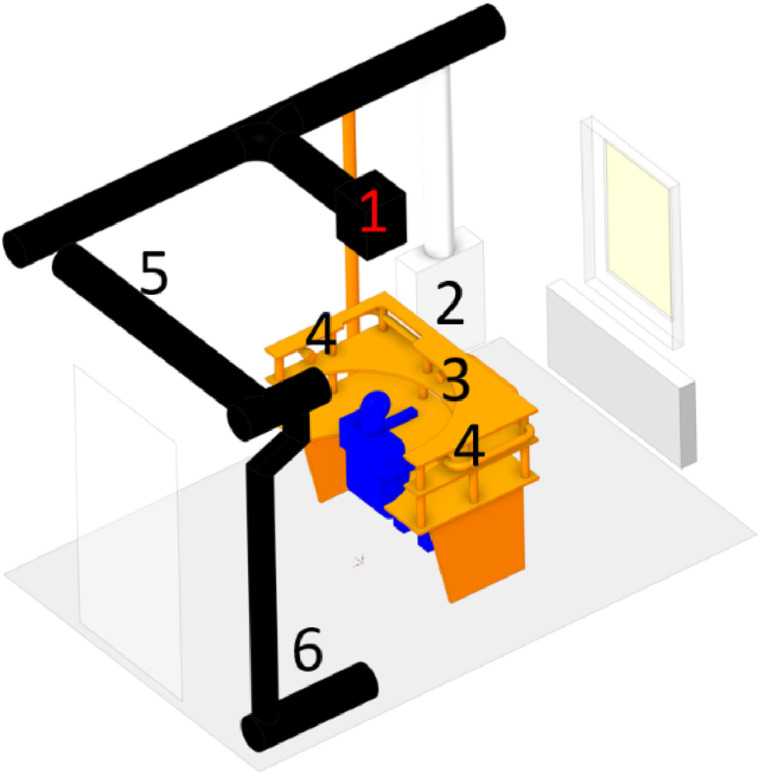

2.2. PV desk

The personalized ventilation desk was developed at the University of Debrecen, [27,28]. The frame of the desk practically serves as built-in air ducts (Fig. 4 ). The desk has its ventilator and an air distribution box. The equipment permits the air jet supply in the breathing zone from three different directions: front, left and right. The air jet directions controlled by magnetic valves can be set by the user through a touch screen control panel (the air velocity as well). The air can be supplied in the breathing zone either from one, two or three directions at the same time. The air jet direction can be constant or variable during the operation. The PV desk was placed in the test room so that the occupant sitting at the desk was positioned in the middle of the room (exactly under the MV ATD). The working desk was connected to the fresh air supply air duct.

Fig. 4.

PV desk.

In the case of personalized ventilation, the flow rate was reduced to half (15 m3/h) to decrease the air velocity around the head of the occupant. It was decided to study two different PV air supply modes. In the first case the fresh air was introduced only from the ATD placed in front of the occupant sitting at the desk (PV-FS), while in the second case the air was introduced simultaneously through the ATD-s placed on the left (7.5 m3/h) and right side (7.5 m3/h) of the occupant (PV-LS). Both AF and UC exhaust modes were tested in each of the air supply cases.

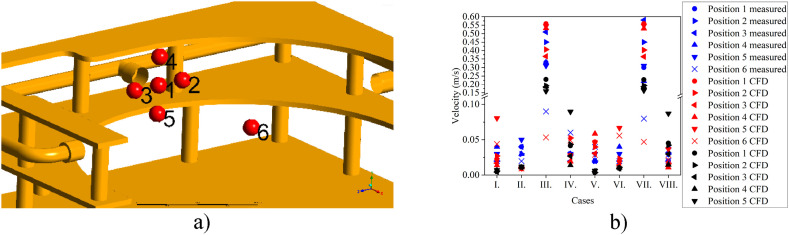

At the head of the occupant the local turbulence intensity was 35% and 38% for MV AF and MV UC ventilation modes, 27% and 31% for DV AF and UC ventilation modes, 31% and 34% for PV-FS AF and UC ventilation modes and finally 46% and 49% for PV-LS AF and UC ventilation modes. The draft rate was 0 for all MV and DV ventilation modes, while in the case of PV-FS AF mode was 5%, in the case of PV-FS UC mode was 6%, in the case of PV-LS AF was 0 and for PV-LS UC ventilation mode was 3%. The velocities have been used for the validation of the simulation model and are presented in Fig. 7b.

Fig. 7.

Velocity measurement points alignments (a); velocity comparison (b) (red: person is not in the room; black: person is in the room). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

2.3. Instruments

The supplied and exhausted airflow, the air velocities, relative humidity, air temperature, and the globe temperature were set before starting the measurements, while the air temperatures, relative humidity and CO2 concentrations were recorded every 5 min during the experiments. The air velocity, local turbulence intensity and draught rate were measured according to EN 16798–3, [29]. The used instruments were calibrated and their accuracies are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Instruments and accuracy.

| Measured parameter | Instrument | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Ventilation rate (MV, DV) – calculated based on velocity | KIMO AMI 300 | ±0.03 m/s ±3% of m.v. |

| Ventilation rate (PV) - calculated based on velocity | TESTO 445 | ±(0.1 m/s +1.5% of m.v.) |

| Air temperature | TESTO 400 | ±0.2 °C |

| Air velocity | TESTO 480 | ±(0.03 m/s +4% of m.v.) |

| Relative humidity | TESTO 400 | ±(1.8 %RH +0.7% of m.v.) |

| Globe temperature | TESTO 480 | Class 1 |

| CO2 concentration | TESTO 400 | ±(50 ppm CO2 +3% of m.v.) |

*m.v. – measured value.

3. Boundary conditions and validation of the simulation model

In the test room, different ventilation systems are installed. These could create various structures of airflow. To describe the patterns of the indoor streams numerical analyses were made. An alternative solution can be the utilization of particle image velocimetry (PIV) which could describe the actual flow patterns, [30]. Numerical analysis was preferred because the desk, which is a relevant object of the measurement, could limit the measured area.

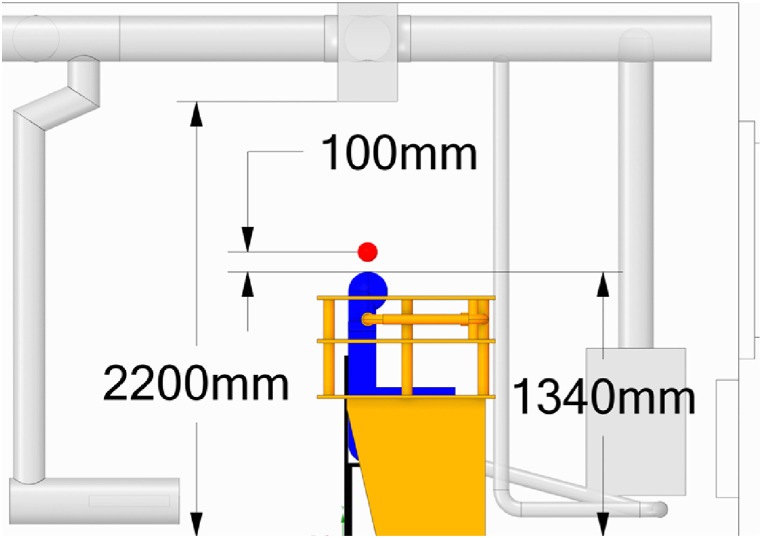

The room and the air channels are shown in Fig. 5 . The mixing and displacement ventilation ATDs are provided with perforated sheets, so the flow direction was always normal to the diffuser surfaces. In the case of PV, three swirl diffusers were used (no. 3 for PV FS, no. 4 for PV LS). Return flow was extracted through a rectangle-shaped diffuser which was applied to the duct (5 - UC and 6 - AF).

Fig. 5.

ATD's location in the test room (1: MV ATD; 2: DV ATD; 3: PV-FS ATD; 4: PV-LS ATD; 5: UC exhaust ATD; 6: AF exhaust ATD).

The created numerical model is an improved version of a previous [4] model of the room. The model inherited the simplified diffuser description, the porous surface was merged into sixteen equal rectangles and the sum of the rectangles was the effective area of the diffusers. The effective area was calculated by dividing the volume flow rate by the velocity in front of the diffuser. This method [31] increases the surface element size while it preserves the flow characteristics and decreases the computational demand. Only the diffusers of the personal ventilation had initial swirls. The swirling motion was described in a localized cylindrical coordinate system, where the origin of the reference frame was the centre point of the diffuser. In all the three diffusers the ratio of the axial to tangential components was 1:3. The magnitude of the flow rate is changed by position. The rest of the flow rates were normal to the boundary. A sitting human body was placed in the middle of the room, so it was possible to represent the flow around a person who sits at the desk. For the boundary condition, the UC and AF exhaust ATD mass flow was given, equal to the inflow.

Based on the analysis of the thermal plume surrounding a person (Appendix A1), simplification was implemented. Natural convection was not modelled since it is considered that the induced flow created by the ventilation system cancels the natural convection flows and the occupant was not in the test room during the validation measurement. As a result of this restriction, the simulation is limited to depicting flow directions and velocity magnitudes.

For discretization polyhedral meshing was used and mesh sensitivity analyses were made for 25 mm 50 mm and 100 mm maximum cell sizes. In all three cases, refinement was applied for the supply and exhaust boundary surfaces. Prismatic cells on the near-wall zones were not made since the model focuses on the room domain and not on the near-wall zones. Furthermore, the Reynolds Averaged model allows for having a larger y+ in the computational domain. To be more precise k-ω SST model turbulence model was utilized, which suits complex isothermal flows [32]. The applied model also inherited the previous solver setup [4]. In which pressure and velocity coupling solver; for pressure PRESTO! for momentum, turbulent kinetic energy, and turbulent dissipation rate calculation third-order upwind MUSCL scheme was applied. The simulations were carried out with Ansys Fluent 2022 R2 software (ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA).

For inlet and outlet boundary conditions, mass flows were used which were calculated from the applied volume flow rates and density of the air for two isothermal scenarios 21 °C (ρ = 1.2006 kg/m; η = 1.8253⋅10−5 kg/m⋅s) and 25 °C (ρ = 1.1845 kg/m3; η = 1.8444⋅10−5 kg/m⋅s). The corresponding flow rates can be seen in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Boundary flow conditions.

| Ventilation mode | Flow rates, [m3/h] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV | DV | PV-FS | PV-LS | Exhaust | |

| Case I | 30 | 30 (AF) | |||

| Case II | 30 | 30 (AF) | |||

| Case III | 15 | 30 (AF) | |||

| Case IV | 7.5–7.5 | 15 (AF) | |||

| Case V | 30 | 30 (UC) | |||

| Case VI | 30 | 30 (UC) | |||

| Case VII | 15 | 15 (UC) | |||

| Case VIII | 7.5–7.5 | 15 (UC) | |||

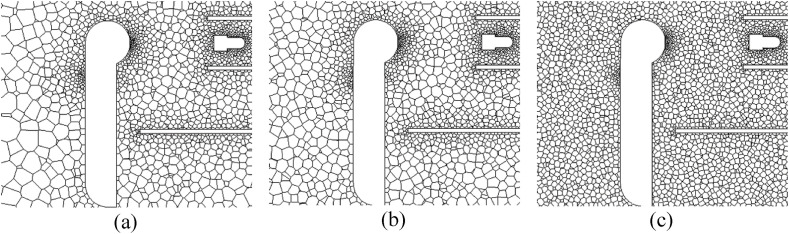

Mesh Sensitivity analyses were made to ensure the quality of the mesh. Three different sizes of polyhedral mesh were used with a maximum cell size of 25 mm; 50 mm and 100 mm respectively. The different meshes are presented in Fig. 6 .

Fig. 6.

Applied meshes: coarse (a), medium (b); fine (c).

For evaluation, the volume-averaged velocity of the room was chosen to be a control parameter. The relative velocities (Table 4 ) show that the 50 mm large cells can give acceptable results. Further refinement only gives a slight change in the control parameter. The chosen mesh volume averaged quality indicators are the following: skewness 0.05, orthogonal quality 0.95 aspect ratio 2.

Table 4.

Results of mesh sensitivity analysis.

| Mesh density | Cell size, [mm] | Cell count | Relative change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 100 mm | 3.95∙105 | 2.27% |

| Medium | 50 mm | 6.04∙105 | 0% |

| Fine | 25 mm | 2.60∙106 | 2.35% |

To validate the numerical model, six notable points were chosen (Fig. 7a) to compare the measured and calculated velocities. The measured velocities were time-averaged values (180 s), thus a steady-state model could represent the actual internal flows. Five measurement points were chosen in a plane located at 10 cm from the frontal diffuser of the PV system. The distance between the measuring point was 10 cm as well. The sixth point is at the intersection of the three PV ATD horizontal axes and MV ATD vertical axis (head of the occupant sitting at the desk practically). This arrangement of the control points helps to adequately compare the swirling diffuser characteristics for cases III and VII. Furthermore, the inlet profile can be adapted for cases IV and VIII. When the air velocities were measured, the occupant was not sitting at the table. That is the reason why two sets of the model were created for the validation process. One set was created without- and one set with the person sitting at the desk. Both are presented in Fig. 7b.

In Fig. 7b the comparison of the numerical model and measurement can be seen. Velocity values are shown for the above-mentioned eight different cases for the six control points chosen. With blue the measured velocity values, with red the CFD without the occupant and with black colour the CFD with the occupant sitting at the desk are presented. The scale was divided into a below 0.1 m/s and a 0.15 m/s section. The reason was to highlight the differences in the low-velocity regime. The black colour represents the cases when a person was placed in the measurement area, thus position six was not calculated in these scenarios. One can see that the numerical model accurately predicts the velocities at the monitored points. The most notable changes can be seen in cases III. and VII. where velocity at the head was underpredicted, while closer to the diffuser velocities were overpredicted. The change can be attributed to the swirl diffuser flow pattern, it produces a strong initial flow and dissipates slightly faster than the experimental data shows. However, the quality of the diffuser setup was strengthened with the result of cases IV. and VIII., where the velocities gave good agreement. With an object placed in the centre of the room, it moderately damped the velocities by blocking and altering the main flows.

4. Results

4.1. Visualization of airflow patterns in the test room

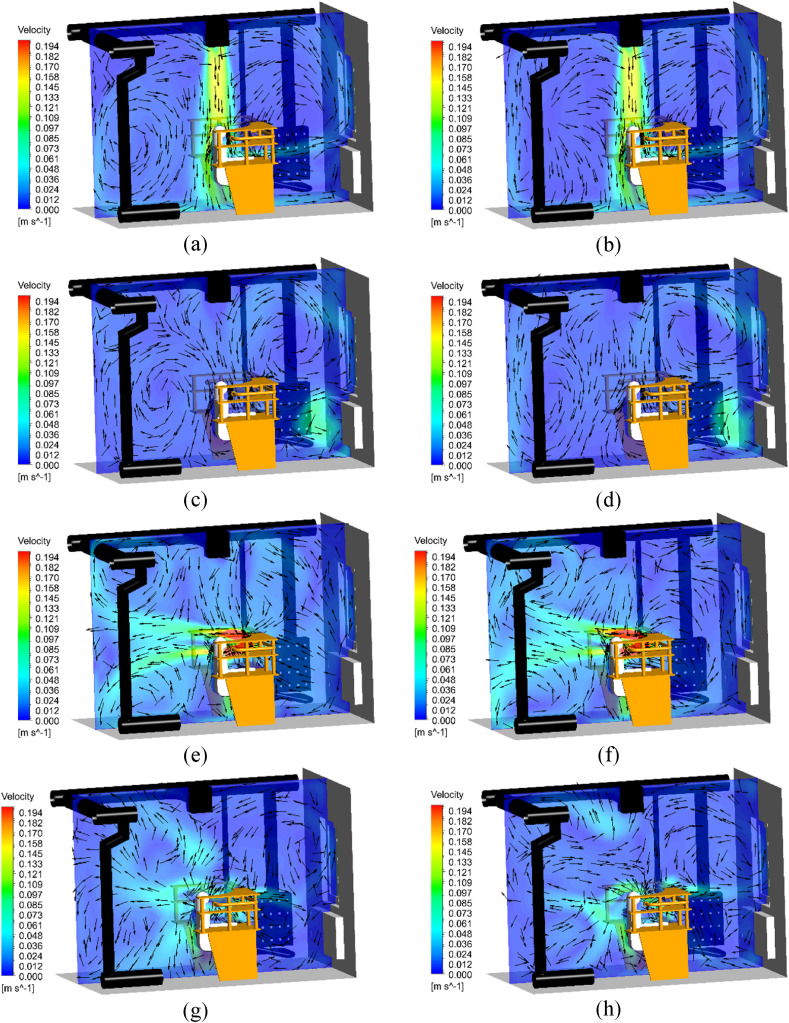

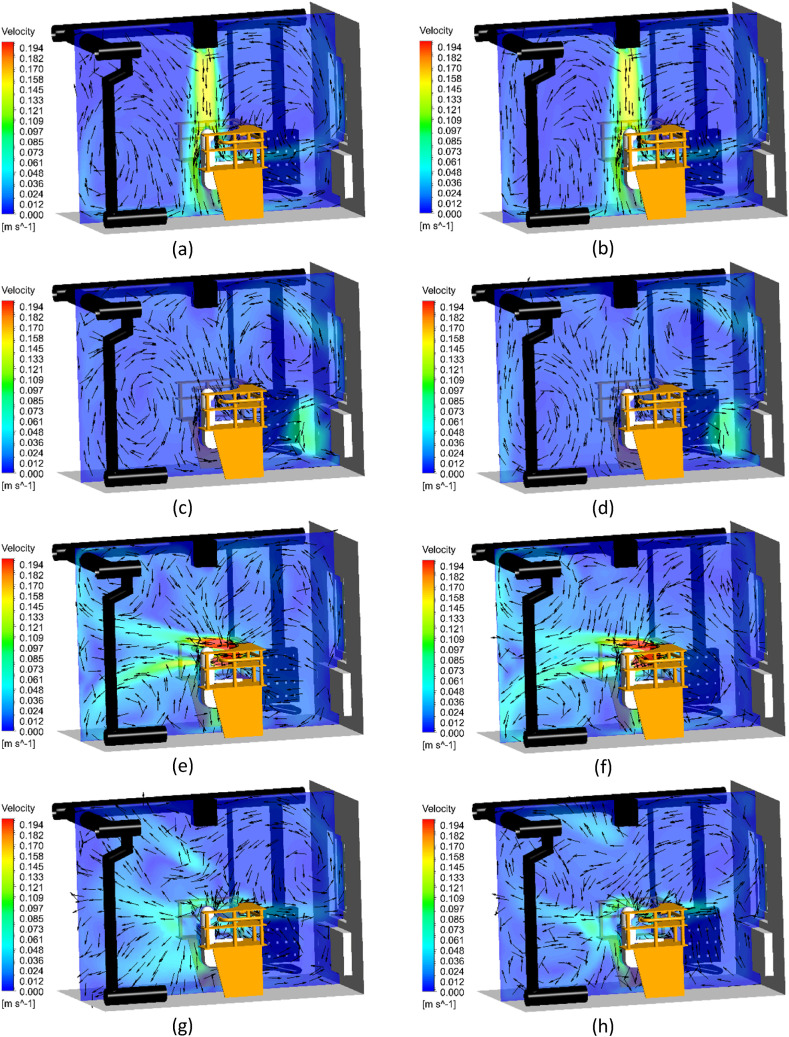

For the sake of visualization, the velocity magnitudes were plotted on the mid-plane of the room. Normalized velocity vectors were used to indicate the airflow direction along the plane. The magnitude with contour plot between 0 and 0.2 m/s. Velocity distributions are plotted in Fig. 8 for the AF exhaust (left column) and for the UC exhaust (right column).

Fig. 8.

Velocity distribution at 25 °C in Case I (a); Case V (b); Case II (c); Case VI (d), Case III (e); Case VII (f); Case IV (g); Case VIII (h).

Since the MV ATD did not have an initial swirl, a moderate speed of airflow was around the person. The main airflow due to the desk created a stream at its level (Fig. 8a–b).

The most homogeneous flow and lowest speeds around the person were achieved in cases II and VI (Fig. 8c–d) when the air was supplied from the DV ATD to the person. Two major flows were created in these cases which generated a downstream on the person sitting at the desk.

The highest velocities were generated around the body when the frontal diffuser of the personal ventilation was applied (Fig. 8e–f). In cases III and VII, a strong swirling flow was generated from the frontal diffuser, which created a cone-like shape. The form was attributed to the different directions of velocities. Models show that when the swirling speed is three times larger than the axial component of the flow the stream flows around the head of the sitting person and most of the fresh air is transferred to the chest of the person. The upper half of the cone shape flow determines the flow profile of the upper region of the room. Furthermore, the flow also induces additional flow which increases the flow rate around the person. The lower half of the flow is directed downward to the floor by the person. Interestingly due to the upper circulation and the absence of notable axial directional flow, around the head, a slight backflow can be seen. This flow is indicated with arrows near the neck region. The position of the return flow diffuser has no effect on the flow structure in these two cases.

In the case of the PV LS ventilation mode, a radial flow was generated. The main flow is indicated on the mid-section plane, the origin was the head of the person. The velocity distribution indicates that around the person a high-velocity zone is created, and its magnitude rapidly decreases when it gets further from the desk. To preserve the continuity of the flow in every case the air moved from the top to the person. Up flows were only noted in cases III and VII.

The position of the exhaust ATD had a significant role in most of the cases (excluding III and VII). When the UC exhaust was utilized the circulating flow behind the person was amplified. With this amplification, the higher zones of the room were also ventilated. When the AF exhaust was used the rear recirculation did not reach the ceiling. The bottom return flow solely increased the velocity at the lower half of the room.

Flow profiles were not only established for 25 °C, but for 21 °C air temperature as well. It was expected that the temperature could alter the flow structure considerably, however, the isothermal models do not show notable changes. The only change in the velocity field is that the boundaries are given in volume flow rate, thus at lower temperatures more mass moved through the room over time. The established flow profiles can be seen in appendix A2.

4.2. Measurements

Eight different ventilation strategies were tested at six different temperatures. One measurement lasted 1 h, but the ventilation system was switched on 30 min before starting the measurement to obtain stable airflows in the test room. Moreover, the ventilation system was started after obtaining in the room the expected set point air and mean radiant temperatures. During the measurements, the CO2 concentration values were registered every 5 min in the supplied air, in the indoor air above the desk leaf (breathing zone), and in the exhausted air.

The ventilation effectiveness was calculated using the following equation:

where: c ex – is the CO2 concentration in the extracted air, [ppm]; c i – is the CO2 concentration in the indoor air (breathing zone), [ppm] c s – is the CO2 concentration in the supplied air, [ppm].

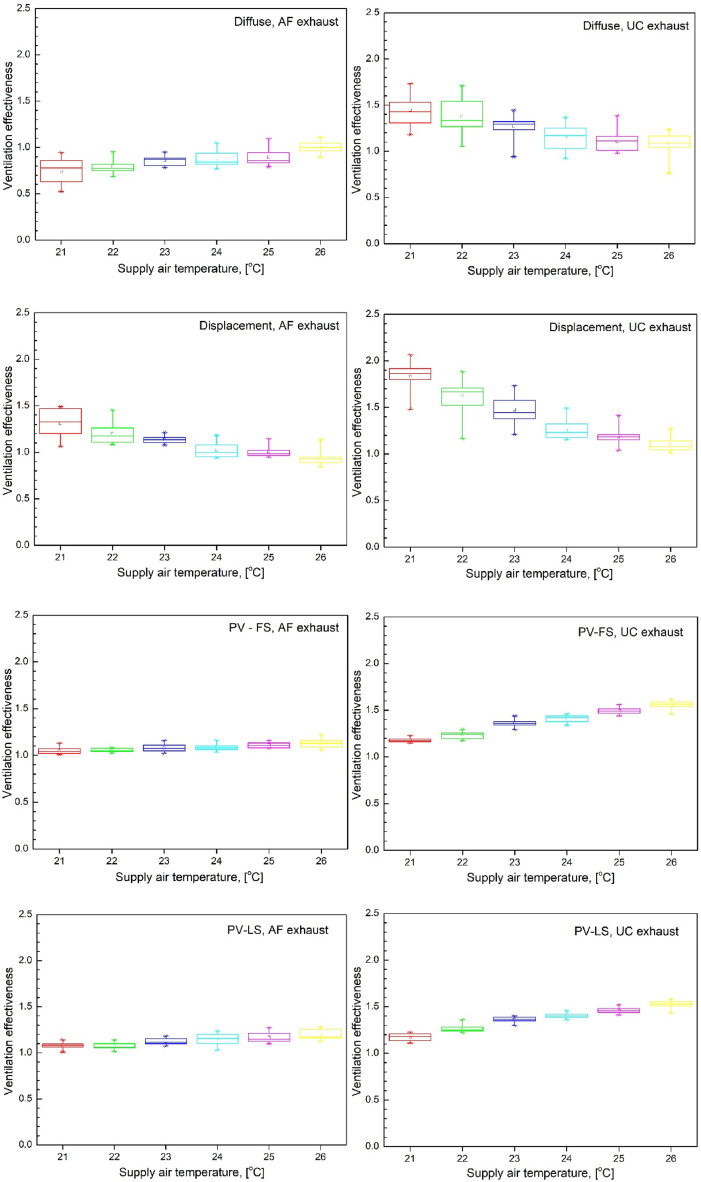

The ventilation effectiveness was not constant during the measurement. The statistical analysis was done using ORIGIN LAB software. In Fig. 9 the box plot diagrams of the analysed cases can be seen. It can be observed that the local ventilation effectiveness shows different variations in function of the air temperature in the case of different ventilation strategies. For the analysed air temperature interval, the MV ventilation mode presented a small increase in the case of AF exhaust, while in the case of UC exhaust a decrease can be observed. In the case of displacement ventilation, the local ventilation effectiveness decreases for both AF and UC exhaust. Personalized ventilation shows an increase in local ventilation effectiveness in all analysed cases. The increase is higher in the case of UC exhaust. The mean values of the ventilation effectiveness are presented in Table 5 . As can be observed in the case of mixing and displacement ventilation the obtained values are a little bit higher than usual. This can be caused by the small dimensions of the test room on one hand and the type and position of ATDs on the other hand.

Fig. 9.

Ventilation effectiveness depending on the air temperatures.

Table 5.

Ventilation effectiveness values.

| Ventilation mode | Value | Temperature, [°C] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | ||

| MV AF | Mean | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 1.00 |

| SD | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | |

| MV UC | Mean | 1.45 | 1.38 | 1.27 | 1.16 | 1.11 | 1.09 |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.12 | |

| DV AF | Mean | 1.31 | 1.20 | 1.14 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 0.94 |

| SD | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | |

| DV UC | Mean | 1.83 | 1.63 | 1.47 | 1.26 | 1.19 | 1.10 |

| SD | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 | |

| PV-FS AF | Mean | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.13 |

| SD | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | |

| PV-FS UC | Mean | 1.18 | 1.23 | 1.36 | 1.41 | 1.49 | 1.55 |

| SD | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | |

| PV-LS AF | Mean | 1.07 | 1.08 | 1.12 | 1.15 | 1.17 | 1.20 |

| SD | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | |

| PV-LS UC | Mean | 1.17 | 1.27 | 1.36 | 1.40 | 1.46 | 1.53 |

| SD | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |

In all ventilation modes, the ventilation effectiveness is higher in the case of the UC position of the exhaust element.

Shapiro-Wilk normality test was done at a 0.05 significance level for each gathered data group. The null hypothesis was that the data are normally distributed. For all cases p-value was greater than 0.05, so the null hypothesis couldn't be rejected (the test did not show evidence of non-normality). The differences between obtained ventilation effectiveness both between temperatures (Table 6 ) and investigated ventilation strategies (Table 7 ) were analysed using paired sample t-test. It was chosen that at the 0.05 level the difference of the population means is significantly different with the test difference (0). The null hypothesis was: mean1−mean2 = 0.

Table 6.

Ventilation effectiveness differences in the case of different temperatures (Sig.: significant difference; Not sig.: not significant difference).

| Temp. [°C] | Ventilation mode |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV AF | MV UC | DV AF | DV UC | PV-FS AF | PV-FS UC | PV-LS AF | PV-LS UC | |

| 21–22 | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. |

| 21–23 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 21–24 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 21–25 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 21–26 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 22–23 | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 22–24 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 22–25 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 22–26 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 23–24 | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 23–25 | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 23–26 | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| 24–25 | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. |

| 24–26 | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. |

| 25–26 | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. |

Table 7.

Significance testing of ventilation effectiveness differences in the case of different ventilation modes (Sig.: significant difference; Not sig.: not significant difference).

| Ventilation modes | Temperatures, [°C] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | |

| MV AF − MV UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. |

| MV AF − DV AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV AF − DV UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV AF − PV-FS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV AF − PV-FS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV AF − PV-LS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV AF − PV-LS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV UC − DV AF | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV UC − DV UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. |

| MV UC − PV-FS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. |

| MV UC − PV-FS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| MV UC − PV-LS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Sig. |

| MV UC − PV-LS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| DV AF − DV UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| DV AF − PV-FS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| DV AF − PV-FS UC | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| DV AF − PV-LS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| DV AF − PV-LS UC | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| DV UC − PV-FS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. |

| DV UC − PV-FS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| DV UC − PV-LS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Not sig. | Sig. |

| DV UC − PV-LS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| PV-FS AF − PV-FS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| PV-FS AF − PV-LS AF | Not sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| PV-FS AF − PV-LS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| PV-FS UC − PV-LS AF | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

| PV-FS UC − PV-LS UC | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Not sig. | Sig. | Not sig. |

| PV-LS AF − PV-LS UC | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. | Sig. |

In the case of PV AF systems, for 1 K air temperature difference, the ventilation effectiveness practically presented no significant differences in most of the analysed cases (only PV-LS AF shows a significant difference for 22 °C − 23 °C and 24 °C − 25 °C). PV UC systems presented significant differences between the local ventilation effectiveness for all analysed temperatures. In the case of MV AF ventilation strategy, for 1 K air temperature difference, the variation of the ventilation effectiveness is significant in the case of 22 °C–23 °C and 25 °C − 26 °C. MV UC ventilation mode shows significant differences in the ventilation effectiveness between temperatures: 22 °C − 23 °C and 23 °C − 24 °C. The difference was significant in the case of DV AF ventilation mode for 23 °C − 24 °C and 25 °C − 26 °C. In the case of DV UC ventilation, the difference was significant for 21 °C − 22 °C, 22 °C − 23 °C and 23 °C − 24 °C. There are cases where the difference between the ventilation effectiveness is not significant even for 2 K temperature difference: MV AF (23 °C − 25 °C), MV UC (24 °C − 26 °C) and PV-LS AF (24 °C − 26 °C).

It can be observed that the difference between ventilation effectiveness is significant between AF and UC position of the exhaust element for almost all analysed ventilation strategies (the only exception is MV ventilation mode in the case of 26 °C air temperature). For a certain air temperature, there are significant differences between the ventilation effectiveness in most of the compared ventilation modes. Interestingly, the PV-FS UC and PV-LS UC ventilations presented no significant difference in the ventilation effectiveness for almost each of the investigated air temperatures (only one exception is 25 °C). The difference is not significant in the case of MV UC – DV AF ventilation for 21 °C air temperature. MV UC and PV-FS AF ventilation strategies show no significant differences in ventilation effectiveness in the case of 24 °C, 25 °C, and 26 °C. The difference is not significant between the local effectiveness between MV UC and PV – LS AF in the case of 23 °C and 24 °C. Furthermore, the difference is not significant in the case of MV UC − DV UC ventilation modes for 25 °C and 26 °C air temperatures.

5. Uncertainties

The measurements performed aimed to analyse the relation between temperature and ventilation effectiveness. To determine the ventilation effectiveness, the CO2 concentration was measured in the supplied, indoor (breathing zone) and exhausted air. In the framework of this study, the uncertainties of air temperatures and CO2 concentrations were determined.

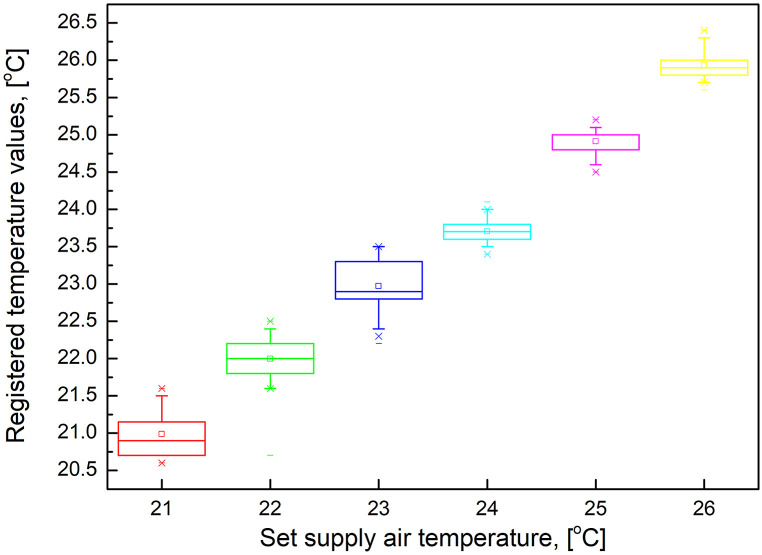

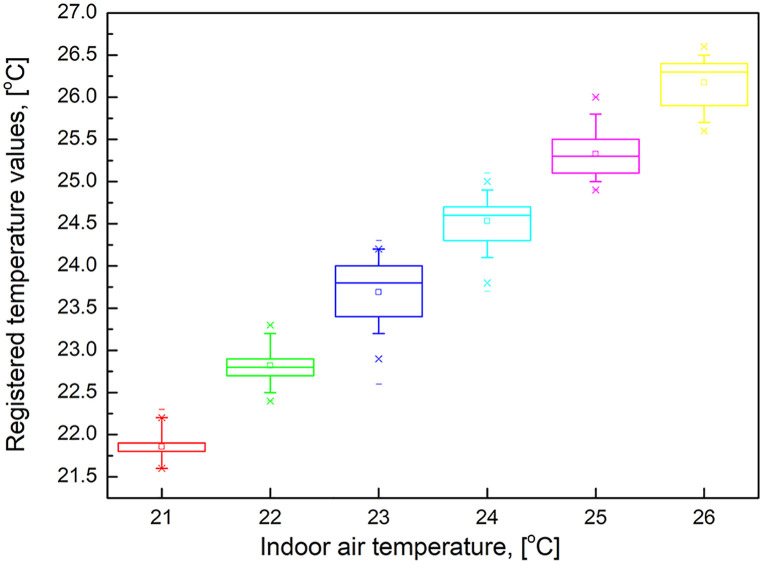

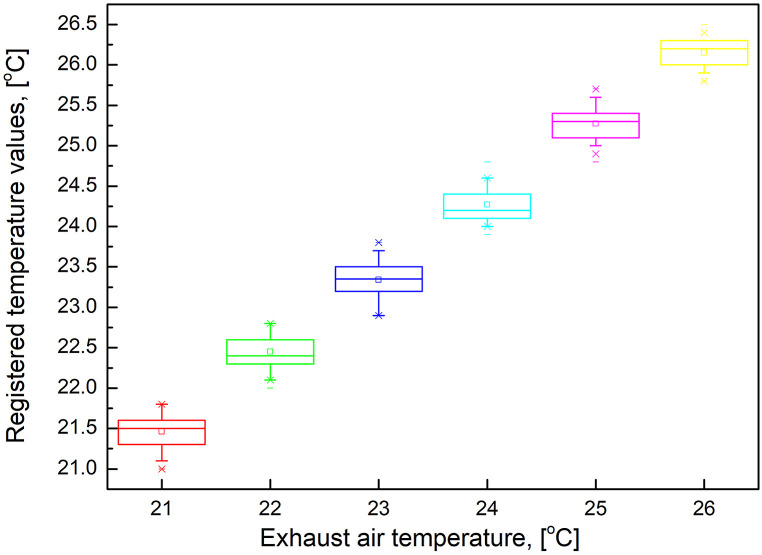

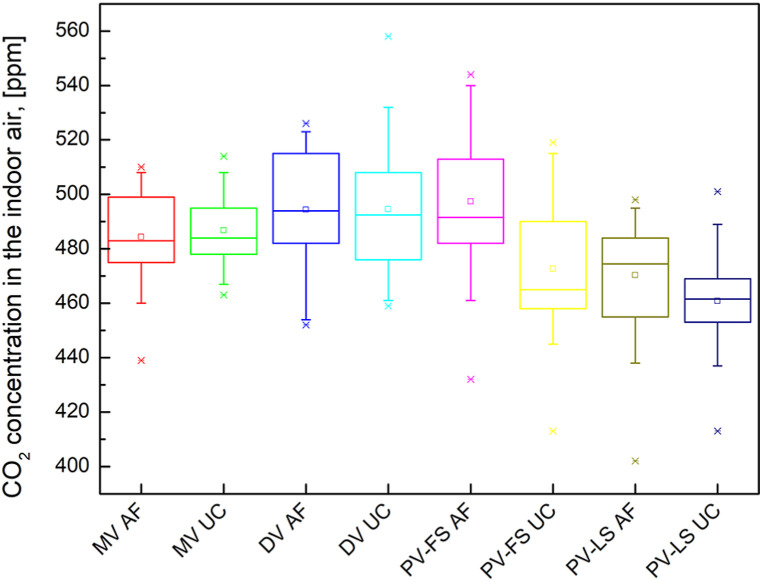

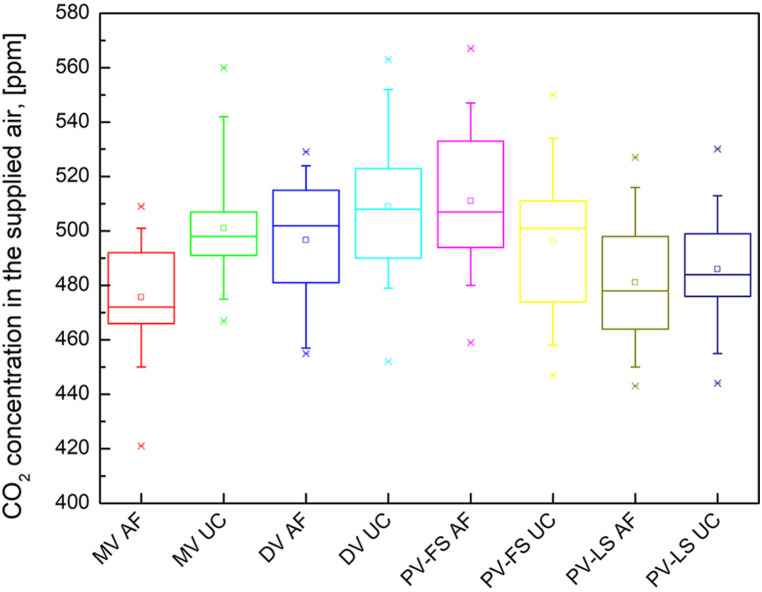

Based on the standard uncertainty Type A (repeated measurements) and Type B (“imported” from the calibration certificate of the measuring instruments), the combined standard uncertainties were calculated (Table A7 and Table A8 in the Appendix). In the calibration certificate, the uncertainty of ±0.08 °C for temperature is given (each probe), while for CO2 concentration the probes had different uncertainties: ±0.9 ppm (supply air), ±1.0 ppm (indoor air) and ±1.6 ppm (exhaust air). The air temperature and CO2 concentration values are presented in Figures A3-A8 in the Appendix. Having eight different ventilation strategies and 13 data registered during one measurement, for a certain temperature 104 values were processed. Having six different temperature values and 13 data registered, for a certain ventilation strategy 78 CO2 concentration data were taken into account.

6. Discussion

To reduce the survival time of the SARS-COV-2 virus the indoor temperature should be kept above 21 °C, [22]. On the other hand, the thermal comfort of occupants might be affected and the work productivity may decrease if the indoor temperature exceeds 26 °C. The cross-infection risk can be mitigated by choosing an appropriate ventilation system which supplies fresh air in the breathing zone reducing the mixing with the polluted indoor air as much as possible. The local effectiveness of a ventilation system practically represents the airflow capacity to clean the air (remove the pollutants) in the breathing zone of the occupant. In practice, designers are using the effectiveness data provided by different standards. Olesen summarized the effectiveness of typical ventilation/air distribution systems [33]. For the isothermal mixing ventilation strategy, the 0.9–1.0 values are given, for displacement ventilation 0.7–0.9 while for personalized isothermal ventilation 1.6–3.5. It can be stated, that in the case of MV and DV strategies the results of the present research correlate well with these values (DV shows higher effectiveness values). However, this study proved that by providing isothermal ventilation with a certain ventilation rate the ventilation effectiveness is not constant at different air temperatures. In the case of mixing ventilation and exhaust above the floor the effectiveness increases at higher temperatures, while in the case of exhaust under the ceiling the effectiveness decreases at higher temperatures. In the case of displacement ventilation, the effectiveness decreases at higher air temperatures both for AF and UC position of the exhaust ATD. For personalized ventilation, the effectiveness increases with the temperature in all analysed cases. The calculated effectiveness values were lower than the usual values for all temperatures in all studied strategies. This fact draws attention to the importance of supply ATD type and exhaust ATD position in the case of personalized ventilation. The set point value of the indoor temperature may be different in cold and warm periods of the year even in a conditioned room. To provide clean air in the breathing zone of occupants in a closed space during the whole year is extremely important to know the exact value of the ventilation effectiveness. Obviously, in the case of air heating or cooling the effectiveness will show other variations [34,35]. Previous studies found that there is a correlation between perceived air quality and air temperature [36,37]. Occupants complain of lower air quality in the case of higher indoor air temperatures even though the ventilation rate was the same as in the case of lower air temperatures. It was presumed that there is a correlation between warm thermal comfort sensation and poor air quality perception in the case of higher air temperatures. This interpretation cannot be rejected, but the present research proved that the ventilation effectiveness decreases at higher air temperatures in the case of some ventilation strategies. The rate of decrease depends on the air temperature and ventilation strategy. The decrease of the ventilation effectiveness can reach in the case of UC exhaust 24% (MV) or even 40% (DV) if the indoor set point temperature is increased from 21 °C to 26 °C. In the case of MV AF, the ventilation effectiveness increases with the increase of the temperature from 0.75 to 1.00 (25%). Almost the same increase rate can be observed in the case of PV UC modes (23.8%). The differences between the local ventilation effectiveness values were significant in most of the analysed cases. Furthermore, between different ventilation modes, the difference in ventilation effectiveness was significant. The main question is: why the ventilation effectiveness varies in the case of isothermal ventilation? Measurements proved that in practice the air temperature is not constant along its way from supply to exhaust in a ventilated space even though isothermal ventilation is planned to be achieved. One reason can be that in the breathing zone the exhaled air is mixed with the supplied air and the temperature of this mixed air exceeds the planned set point temperature value. Besides the temperature, the exhaled airflow has a certain velocity. In the case of very low air velocities around the occupant, the “polluted” exhaled air is only partially removed by the supplied airflow. The exhaled air partially lefts the breathing zone and enters the less ventilated zones of the room. If the used ventilation strategy leads to the mixing of the air in the whole room, the air with high pollutant concentration may return to the breathing zone and finally, the pollutant (CO2 in our case) concentration in the breathing zone will be higher than expected. The mixing of the air in the room is well illustrated by the airflow patterns obtained through simulation. Therefore, the supplied airflow should be always chosen taking into account the ventilation strategy and air temperature. To reduce the cross-infection risk, even 12 h−1 air change rates are recommended, [22]. At the same time, the mixing between the polluted indoor air and fresh supplied air should be avoided, [7]. Melikov stood for occupant-focusing ventilation design instead of space ventilation, [8]. As it was demonstrated in previous studies [4,38,39], personalized ventilation may assure in the breathing zone clean air even at lower ventilation rates. In the present study, the ventilation effectiveness was the highest in the case of DV UC ventilation mode in the vase of 21 °C, 22 °C, and 23 °C, but for 24 °C, 25 °C and 26 °C the highest ventilation effectiveness values were presented by personalized ventilation strategies (UC exhaust) providing half of the ventilation rate supplied with mixing and displacement ventilation modes 15 m3/h instead of 30 m3/h). Providing high ventilation effectiveness in the breathing zone of occupants in indoor spaces is of utmost importance, taking into consideration the mitigation efforts of the airborne transmission of SARS-COV-2 and other viruses. In existing mechanically ventilated buildings the ventilation system (fans, air channels, ATDs, heating and cooling devices, humidifier, heat exchanger) was designed to provide a certain ventilation rate in the closed spaces. Shifting a ventilation system operation to a high air change rate (from 2.0 h−1 to 12 h−1) can be a serious challenge in most of cases. To enhance the ventilation effectiveness changing the ventilation strategy can be the more advantageous solution. The basic reproduction number (R0) is a well-known epidemiological concept to measure the spread of an infectious disease. Locatelli et al. studied the R0 both in European countries and China [40]. They evaluated the percentage of immune persons needed to stop the outbreak. It should be mentioned that currently, in the derivated formula of basic reproduction number (based on the CO2 concentration), the ventilation effectiveness is not taken into account, [10].

An important question is about the air velocities around the occupant. Natural convection happens in a room when the flow is not induced by any mechanical device and there is a significant heat load. This upward flow has the potential to reach relatively high velocities [41]. The upward flow has a greater temperature than the surrounding environment, concentrating in a plume-like form. Investigating the presence of the thermal plume in the mechanically ventilated test room, measurements show that the magnitude of the velocity above the person's head is significantly larger when solely natural convection occurs than when mechanical ventilation is present (Appendix A1).

We assumed -based on the measured data-that the mechanically induced flow completely disrupts the thermal plume and distorts the direction of the main current created by natural convection.

7. Conclusions and future work

Present work aimed to analyse the ventilation effectiveness depending on the air temperature in the case of different isothermal balanced ventilation modes. Air temperatures between 21 °C and 26 °C have been investigated.

The following conclusions may be drawn:

-

-

the ventilation effectiveness shows significant variations depending on the temperature in the case of all studied ventilation strategies;

-

-

the highest ventilation effectiveness values were obtained in the case of displacement ventilation for 21 °C–23 °C, while for 24 °C–26 °C personalized ventilation modes with air exhaust under the ceiling provide the highest local effectiveness values (even though the ventilation rate was reduced to half in comparison with mixing and displacement ventilation);

-

-

in the case of personalized ventilation with air exhaust above the floor the ventilation effectiveness was lower than expected in both frontal and lateral air supply cases;

-

-

significant differences in ventilation effectiveness were identified between the investigated ventilation modes (the only exception was PV-FS UC and PV-LS UC); To mitigate the airborne transmission of viruses, currently, the recommendation is to increase substantially the air change rate in ventilated spaces. However, the variation of ventilation effectiveness depending on different operational factors (air temperature, ventilation rate, airflow patterns) should be known as well, to provide clean air to occupants in the breathing zone, minimizing the cross-infection risk accordingly.

To provide more information to designers and building operators the research has to be continued to analyse the ventilation effectiveness in large spaces taking into consideration different internal and external disturbance factors of the airflow patterns. The ventilation effectiveness should be introduced in the equation of basic reproduction number (R0).

8. Limitations

Measurements were carried out in a test room placed in an adiabatic chamber, which is constructed inside an airtight, well-insulated building. The size of the test room is 2.49 m in width, 3.65 m in length and 2.56 m in height. The CO2 source was one person sitting at the desk placed in the middle of the room. All parameters (supplied air temperature, ventilation rates) were properly controlled. In large indoor spaces with different internal and external disturbance factors, the results might be different. Natural convection was not modelled. As a result of this restriction, the simulation is limited to depicting flow directions and velocity magnitudes.

Authors contribution

KT: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, writing original draft; SZF: simulation, validation, visualization, writing (section 3, 4.1); KF: conceptualization, writing - review & editing

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Project no. TKP2021-NKTA-34 has been implemented with the support provided from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund of Hungary, financed under the TKP2021-NKTA funding scheme.

Appendix.

A1. Thermal plume

To determine the effects of the heat released by the occupant through convection on the air velocities in the room, a series of measurements were performed (for 23 °C and 26 °C air temperatures) measuring the air velocities 10 cm above the head of the occupant in the case of different ventilation strategies. Each measurement lasted 180 s and was repeated three times. The time-averaged velocities were taken into account.

Measurements were performed using TESTO 480 instrument with an air velocity probe. We measured the average velocity for 180 s and repeated the measurement three-six times.

Fig. A1.

Location of the measuring point

In the case of 26 °C in the test room, when the mechanical ventilation was switched off, the air velocities were between 0.17 m/s-0.19 m/s. Switching on the mechanical ventilation and supplying 30 m3/h air flow rate at 26 °C (MV AF ventilation strategy) the air speed in the measuring location was 0.02 m/s and 0.03 m/s when the occupant was not in the room. With this ventilation strategy, the air velocity (with occupant in the room) was 0.04 m/s – 0.05 m/s. In the case of MF UC ventilation strategy, the air velocity was 0.04 m/s – 0.06 m/s without occupant and 0.04 m/s – 0.05 m/s with occupant. For DV UC ventilation strategy the velocities were 0.05 m/s for each measurement without occupant and 0.04 m/s – 0.05 m/s with occupant. For DV AF ventilation strategy the air speed was 0.03 m/s without occupant (for each measurement) and 0.03 m/s – 0.04 m/s with occupant.

In the case of 23 °C in the test room, when the mechanical ventilation was switched off, we measured velocities between 0.18 m/s-0.20 m/s above the head of the occupant. Switching on the mechanical ventilation and supplying 30 m3/h air flow rate (MV AF ventilation strategy) the air speed was 0.05 m/s and 0.06 m/s when the occupant was not in the room. When the occupant was in the room the air velocity in the case of this ventilation strategy was 0.05 m/s – 0.06 m/s. In the case of MF UC ventilation strategy, the air velocity was 0.04 m/s (for each measurement) without occupant and 0.05 m/s – 0.07 m/s with occupant. For DV UC ventilation strategy the velocities were 0.06 m/s for each measurement without occupant and 0.04 m/s – 0.06 m/s with occupant. For DV AF ventilation strategy the air speed was 0.04 m/s −0.05 m/s without occupant (for each measurement) and 0.04 m/s – 0.06 m/s with occupant.

A2. Airflow patterns (21 °C)

Fig. A2.

Velocity distribution at 21 °C in Case I (a); Case V (b); Case II (c); Case VI (d), Case III (e); Case VII (f); Case IV (g); Case VIII (h)

A3. Registered air temperatures

Fig. A3.

Registered supply air temperature

Table A1.

Mean supply air temperature (ts) and standard deviation

| N | ts, [°C] | SD |

|---|---|---|

| 104 | 20.99 | 0.31 |

| 104 | 22.00 | 0.28 |

| 104 | 22.97 | 0.33 |

| 104 | 23.70 | 0.14 |

| 104 | 24.91 | 0.17 |

| 104 | 25.93 | 0.18 |

N – data number (8 ventilation strategies × 13 registered data).

Fig. A4.

Registered indoor air temperature

Table A2.

Mean indoor air temperatures (ti) and standard deviation

| N | ti, [°C] | SD |

|---|---|---|

| 104 | 21.86 | 0.15 |

| 104 | 22.82 | 0.21 |

| 104 | 23.69 | 0.35 |

| 104 | 24.53 | 0.28 |

| 104 | 25.33 | 0.29 |

| 104 | 26.17 | 0.28 |

Fig. A5.

Registered exhaust air temperature

Table A3.

Mean exhaust air temperatures (tex) and standard deviation

| N | tex, [°C] | SD |

|---|---|---|

| 104 | 21.46 | 0.20 |

| 104 | 22.45 | 0.19 |

| 104 | 23.34 | 0.22 |

| 104 | 24.27 | 0.19 |

| 104 | 25.27 | 0.20 |

| 104 | 26.15 | 0.16 |

A4. CO2concentration

Fig. A6.

Registered CO2 concentration in the supplied air

Table A4.

Mean CO2 concentration and standard deviation (supplied air)

| Ventilation strategy | N | Mean CO2, [ppm] | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MV AF | 78 | 434.5 | 16.8 |

| MV UC | 78 | 431.9 | 13.2 |

| DV AF | 78 | 427.5 | 8.5 |

| DV UC | 78 | 430.9 | 14.6 |

| PV-FS AF | 78 | 391.4 | 16.7 |

| PV-FS UC | 78 | 385.9 | 10.4 |

| PV-LS AF | 78 | 386.2 | 10.6 |

| PV-LS UC | 78 | 385.7 | 12.0 |

Fig. A7.

Registered CO2 concentration in the indoor air

Table A5.

Mean CO2 concentration and standard deviation (indoor air)

| Ventilation strategy | N | Mean CO2, [ppm] | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MV AF | 78 | 484.4 | 15.7 |

| MV UC | 78 | 486.8 | 11.9 |

| DV AF | 78 | 494.3 | 23.1 |

| DV UC | 78 | 494.5 | 23.3 |

| PV-FS AF | 78 | 497.4 | 22.9 |

| PV-FS UC | 78 | 472.6 | 23.2 |

| PV-LS AF | 78 | 470.4 | 19.8 |

| PV-LS UC | 78 | 460.9 | 15.1 |

Fig. A8.

Registered CO2 concentration in the exhaust air

Table A6.

Mean CO2 concentration and standard deviation (exhaust air)

| Ventilation strategy | N | Mean CO2, [ppm] | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| MV AF | 78 | 475.7 | 16.6 |

| MV UC | 78 | 501.0 | 20.2 |

| DV AF | 78 | 496.7 | 22.2 |

| DV UC | 78 | 509.0 | 22.9 |

| PV-FS AF | 78 | 511.1 | 24.1 |

| PV-FS UC | 78 | 496.4 | 24.5 |

| PV-LS AF | 78 | 481.1 | 21.3 |

| PV-LS UC | 78 | 486.0 | 17.6 |

A5. Uncertainties

Table A7.

Uncertainties of air temperature data (coverage factor k = 2), confidence 95%

| Air | Temperature, [°C] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | |

| Supply | ±0.100 | ±0.097 | ±0.103 | ±0.085 | ±0.086 | ±0.087 |

| Indoor | ±0.085 | ±0.090 | ±0.105 | ±0.097 | ±0.098 | ±0.097 |

| Exhaust | ±0.089 | ±0.088 | ±0.091 | ±0.088 | ±0.089 | ±0.086 |

Table A8.

Uncertainties of CO2 concentration data (coverage factor k = 2), confidence 95%

| Air | Ventilation mode |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV AF | MV UC | DV AF | DV UC | PV-FS AF | PV-FS UC | PV-LS AF | PV-LS UC | |

| Supply | ±3.911 | ±3.117 | ±2.120 | ±3.434 | ±3.880 | ±2.514 | ±2.559 | ±2.865 |

| Indoor | ±3.698 | ±2.864 | ±5.326 | ±5.359 | ±5.291 | ±5.347 | ±4.587 | ±3.562 |

| Exhaust | ±4.235 | ±4.923 | ±5.510 | ±5.659 | ±6.188 | ±5.115 | ±5.101 | ±4.191 |

Data availability

The data that has been used is confidential.

References

- 1.L. Morawska, D. K. Milton, It is time to address airborne transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Clin. Infect. Dis., 71(2020), 2311-2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Mouchtouri V.A., Koureas M., Kyritsi M., Vontas A., Kourentis L., Sapounas S., Rigakos G., Petinaki E., Tsiodras S., Hadjichristodoulou Ch. Environmental contamination of SARS-CoV-2 on surfaces, air-conditioner and ventilation systems. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2020;230 doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2020.113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lidia M., Tang Julian W., Bahnfleth W., Bluyssen M., Boerstra A., Buonanno G., Cao J., Dancer S., Floto A., Franchimon F., Haworth C., Hogeling J., Isaxon Ch, Jimenez J.L., Kurnitski J., Li Y., Loomans M., Marks G., Marr L.C., Mazzarella L., Melikov A.K., Miller S., Milton D.K., Nazaroff W., Nielsen P.V., Noakes C., Peccia J., Querol X., Sekhar C., Seppänen O., Tanabe S., Tellier R., Tham K.W., Wargocki P., Wierzbicka A., Yao M. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Environ. Int. 2020;142 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalmar T., Szodrai F., Kalmar F. Experimental study of local effectiveness in the case of balanced mechanical ventilation in small offices. Energy. 2022;244 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun C., Zhai Z. The efficacy of social distance and ventilation effectiveness in preventing COVID-19 transmission. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020;62 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.M. H. Hvelplund, L. Liu, K. M. Frandsen, H. Qian, P. V. Nielsen, Y. Dai, L. Wen, Y. Zhang, Numerical investigation of the lower airway exposure to indoor particulate contaminants Indoor Built Environ. 29(4), 575-586.

- 7.Szekeres Sz, Kostyák A., Szodrai F., Csáky I. Investigation of ventilation systems to improve air quality in the occupied zone in office buildings. Buildings. 2022;12(4):493. doi: 10.3390/buildings12040493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melikov A.K. COVID-19: reduction of airborne transmission needs paradigm shift in ventilation. Build. Environ. 2020;186 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.M. Sandberg, A. Kabanshi, H. Wigo, Is building ventilation a process of diluting contaminants or delivering clean air?, Indoor Built Environ. 29(6), 768-774.

- 10.Chen C.Y., Chen P.H., Chen J.K., Su T.Ch. Recommendations for ventilation of indoor spaces to reduce COVID-19 transmission. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021;120:2055–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian H., Miao T., Liu L., Zheng X., Luo D., Li Y. Indoor transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Indoor Air. 2021;31:639–645. doi: 10.1111/ina.12766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan Y., Du Ch, Fu Zh, Fu M. Re-thinking of engineering operation solutions to HVAC systems under the emerging COVID-19 pandemic. J. Build. Eng. 2021;43 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Ch, Tang H. Study on ventilation rates and assessment of infection risks of COVID-19 in an outpatient building. J. Build. Eng. 2021;42 [Google Scholar]

- 14.P. F. Pereira, N. M. M. Ramos, The impact of mechanical ventilation operation strategies on indoor CO2 concentration and air exchange rates in residential buildings, Indoor Built Environ. 30(9), 1516-1530.

- 15.Melikov A.K., Ai Z.T., Markov D.G. Intermittent occupancy combined with ventilation: an efficient strategy for the reduction of airborne transmission indoors. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;744 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang S., Ai Z., Lin Z. Occupancy-aided ventilation for both airborne infection risk control and work productivity. Build. Environ. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park S., Choi Y., Song D., Kim E.K. Natural ventilation strategy and related issues to prevent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) airborne transmission in a school building. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;789 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Y., Niu J. Assessment of mechanical exhaust in preventing vertical cross-household infections associated with single-sided ventilation. Build. Environ. 2016;105:307–316. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gil-Baez M., Lizana J., Becerra Villanueva J.A., Molina-Huelva M., Serrano-Jimenez A., Chacartegui R. Natural ventilation in classrooms for healthy schools in the COVID era in Mediterranean climate. Build. Environ. 2021;206 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stabile L., Massimo A., Canale L., Russi A., Andrade A., Dell'Isola M. The effect of ventilation strategies on indoor air quality and energy consumptions in classrooms. Buildings. 2019;9:110. doi: 10.3390/buildings9050110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu Y., Li Y., Zhou H., Lin J., Zheng Z., Xu H., Lin B., Lin M., Liu L. Affordable measures to monitor and alarm nosocomial SARS-CoV-2 infection due to poor ventilation. Indoor Air. 2021;31:1833–1842. doi: 10.1111/ina.12899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elsaid A.M., Salem Ahmed M. Indoor air quality strategies for air-conditioning and ventilation systems with the spread of the global coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemic: improvements and recommendations. Environ. Res. 2021;199 doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y., Tung T.C.W., Niu J. On-site measurement of tracer gas transmission between horizontal adjacent flats in residential building and cross-infection risk assessment. Build. Environ. 2016;99:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berlanga F.A., Olmedo I., Ruiz de Adana M., Villafruela J.M., San José J.F., Castro F. Experimental assessment of different mixing air ventilation systems on ventilation performance and exposure to exhaled contaminants in hospital rooms. Energy Build. 2018;177:207–219. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng P., Pomianowski M., Zhang Ch, Guo R., Jensen R.L., Jønsson K.T., Gong G. Experimental investigation on the ventilation performance of diffuse ceiling ventilation in heating conditions. Build. Environ. 2021;205 [Google Scholar]

- 26.C. Xu, L. Liu, Personalized ventilation: one possible solution for airborne infection control in highly occupied space?, Indoor Built Environ. 27(7), 873-876.

- 27.Kalmár F., Kalmár T. Alternative personalized ventilation. Energy Build. 2013;65:37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalmár F. Innovative method and equipment for personalized ventilation. Indoor Air. 2015;25:297–306. doi: 10.1111/ina.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.EN 16798-3:2018, Energy Performance of Buildings. Ventilation for Buildings. Part 3: for Non-residential Buildings. Performance Requirements for Ventilation and Room-Conditioning Systems.

- 30.Zheng C., Liu J. Study on indoor air movement under the crowding conditions by numerical simulations and PIV small-scale experiments. Procedia Eng. 2015;121:1650–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.09.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao B., Li X., Yan Q. A simplified system for indoor airflow simulation. Build. Environ. 2003;38(4):543–552. doi: 10.1016/S0360-1323(02)00182-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J., Zhu S., Kim M.K., Srebric J. A review of CFD analysis methods for personalized ventilation (PV) in indoor built environments. Sustain. Times. 2019;11(15):5–7. doi: 10.3390/su11154166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olesen B.W. Revision of EN 15251: indoor environmental criteria. REHVA Journal –. 2012;August:6–12. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian X., Zhang S., Awbi H.B., Liao C., Cheng Y., Lin Z. Multi-indicator evaluation on ventilation effectiveness of three ventilation methods: an experimental study. Build. Environ. 2020;180 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomasi R., Krajcík M., Simone A., Olesen B.W. Experimental evaluation of air distribution in mechanically ventilated residential rooms: thermal comfort and ventilation effectiveness. Energy Build. 2013;60:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalmár F. An indoor environment evaluation by gender and age using an advanced personalized ventilation system. Build. Serv. Eng. Technol. 2017;38(5):505–521. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalmár F. Investigation of thermal perceptions of subjects with diverse thermal histories in warm indoor environment. Build. Environ. 2016;107:254–262. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaczmarczyk J., Melikov A., Fanger P.O. Human response to personalized ventilation and mixing ventilation. Indoor Air. 2004;14(Suppl 8):17–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang J., Sekhar S.C., Cheong K.W.D., Raphael B. Performance evaluation of a novel personalized ventilation–personalized exhaust system for airborne infection control. Indoor Air. 2015;25:176–187. doi: 10.1111/ina.12127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Locatelli I., Trächsel B., Rousson V. Estimating the basic reproduction number for COVID-19 in Western Europe. PLoS One. 2021;16(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voelker C., Alsaad H. Simulating the human body's microclimate using automatic coupling of CFD and an advanced thermoregulation model. Indoor Air. 2018;28:415–425. doi: 10.1111/ina.12451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that has been used is confidential.