Abstract

Gastrosplenic fistula is an unusual complication of benign as well as malignant gastric and splenic pathologies. This pathology acquires an important clinical significance due to its rare association with life-threatening upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. The aim of this article is to review the English-language literature in order to gain a better understanding of etiological factors, diagnostic evaluation, and management of gastrosplenic fistula. The systematic search of the literature was performed on PubMed and MEDLINE from January 1950 to September 2020 according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement. We retrieved 44 articles matching our selection criteria from the search. There were 3 case series, 37 case reports, and 4 review of the literature. In our appraisal of articles published in PUBMED, a total of 36 cases of malignant and 10 cases of benign gastrosplenic fistula could be identified. Gastrosplenic fistula is an exceptional complication of malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract. Lymphomas particularly arising from the spleen are the commonest cause. Gastric adenocarcinoma causing GSF is extremely rare. Most cases occur spontaneously, but at times, it can be secondary to tumour necrosis following chemotherapy.

Keywords: Gastrosplenic fistula, Malignant and benign aetiology, Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage

Introduction

Gastrosplenic fistula (GSF) is an unusual complication of benign as well as malignant gastric and splenic pathologies. Lymphoma of the spleen being the most commonly incriminated aetiopathology [1, 2]. However, rarely, it can occur due to gastric lymphoma or adenocarcinoma. Its occurrence in association with benign pathologies is even rare. Though the presentation is often insidious, nevertheless, it may rarely present with catastrophic gastrointestinal haemorrhage requiring emergent embolization or surgical extirpation for control [3, 4]. Therefore, a high index of suspicion of GSF is warranted in all patients with gastrointestinal lymphomas presenting with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Most cases occur spontaneously, though occasionally, they may complicate following a course of chemotherapy. In this study, we present and share a review of the English literature devoted to GSF in order to gain a better understanding of the etiological factors, diagnostic evaluation, and management of this pathology.

Methods

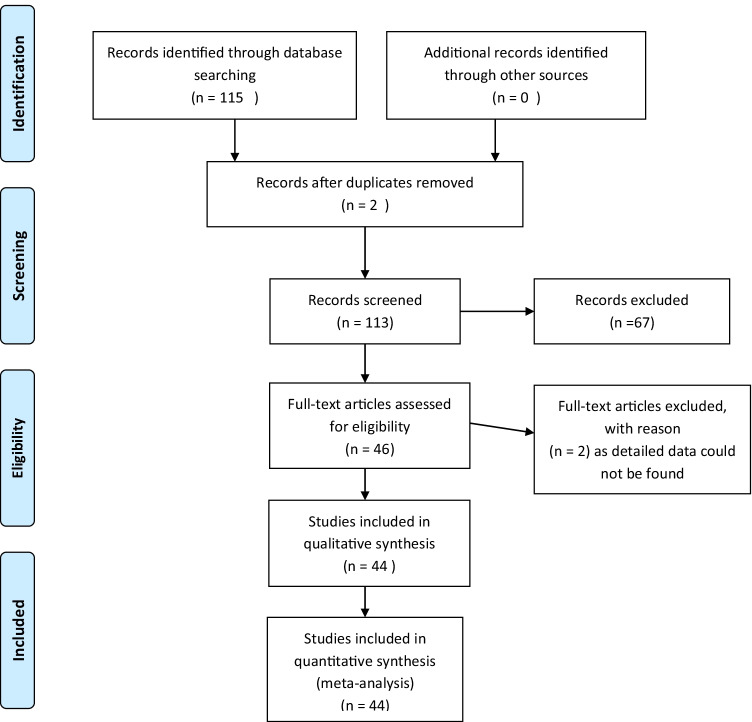

The search strategy, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and primary and secondary outcomes were defined before the search. The systematic search of the literature was performed on PubMed and MEDLINE from January 1950 to September 2020 according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement (Fig. 1). All resulting titles, abstract, and full text, when available, were read and kept for reference. Specific MeSH terms included “gastrosplenic fistula,” “malignant etiology,” “benign etiology,” “histopathology,” “imaging studies,” “endoscopy,” “chemotherapy,” and “surgical intervention.”

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart

Observation prospective and retrospective studies, case series, and case reports on gastrosplenic fistula secondary to benign as well as malignant aetiology of stomach and spleen were included for the full review. Exclusion criteria included patients with a history of primary malignancy other than stomach and spleen and patients with a history of distal gastrectomy or gastric pull through procedure (as surgery results in distortion of anatomy and the procedure itself can result in iatrogenic fistula formation).

Data were extracted by one author independently and then compared by the other author. The study author provided additional data if incomplete data were noted. Titles/abstracts considered potentially relevant were retrieved for review of the full manuscript. The list of full manuscript meeting inclusion criteria were compared, and any disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus.

Results

We retrieved 44 articles meeting our criteria from the search. Tables 1, 2, and 3 list articles matching the inclusion criteria. There were 3 case series, 37 case reports, and 4 review of the literature. In our appraisal of articles published in PubMed, a total of 36 cases of malignant GSF (Table 1) and 10 cases of GSF due to benign aetiologies could be identified (Table 2). Table 3 lists 22 articles with detailed description as the complete data of other reported cases was not available.

Table 1.

Gastrosplenic fistula due to malignant aetiology (n = 36); NHL: non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

| Author/year | Site and type of primary | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Kyang LS et al. (2020) [30] | Splenic lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Yokoyama Y et al. (2020) [31] | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Saito M et al. (2019) (2 cases) [32] | Splenic B-cell lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Kang DH et al. (2017) [33] | Splenic T-cell lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Gentilli S et al. (2016) [34] | Splenic B-cell lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Martinez JD et al. (2015) | Gastric adenocarcinoma | Spontaneous |

| Senapati J et al. (2014) [35] | Splenic B-cell lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Ding YL et al. (2012) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Dellaportas D et al. (2011) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Moran M et al. (2011) | Gastric, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Jain V et al. (2011) | ? Gastric ?? Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Rothermal LD et al. (2010) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Khan F et al. (2010) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| García MA et al. (2009) | Gastric, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Maillo C et al. (2009) | Splenic, Hodgkins lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Seib CD et al. (2009) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Palmowski M. et al. (2008) | Splenic, NHL | Post-chemotherapy |

| Aribas BK et al. (2008) | Splenic, NHL | Post-chemotherapy |

| Moghazy KM et al. (2008) | Splenic, NHL | Post-chemotherapy |

| Al-Ashgar HI et al. (2007) | Splenic, Hodgkins lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Kerem M et al. (2006) | Gastric, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Puppala R et al. (2005) | Gastric, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Bird M A et al. (2002) | Splenic lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Pizzirusso F et al. (2004) | Colonic cancer with splenic metastasis | Post-Chemotherapy for Carcinoma colon |

| Choi JE et al. (2002) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Yang SE et al. (2002) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Carolin KA et al. (1997) | Gastric, NHL | Post-chemotherapy |

| Blanchi A et al. (1995) (Case 1) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Blanchi A et al. (1995) (Case 2) | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Delgado Sanchez MJ et al. (1994) [36] | Splenic lymphoma | Spontaneous |

| Hiltunen KM et al. (1992) | Gastric, high-grade centroblastic lymphoma | Post-chemotherapy |

| Krause R et al. (1990) | Gastric, adenocarcinoma | ?Post-chemotherapy |

| Harris NL et al. (1984) [37] | Splenic, NHL | Spontaneous |

| Bubenik O et al. (1983) | Splenic, NHL | Post-chemotherapy |

| De Scoville A et al. (1967) (Case 1) | Splenic lymphosarcoma | Spontaneous |

| De Scoville A et al. (1967) (Case 2) | Splenic lymphosarcoma | Spontaneous |

Table 2.

Benign causes of gastrosplenic fistula (n = 10)

| Author | Year | Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Leeds IL et al. [38] | 2016 | Splenic abscess |

| Lee KJ et al. [39] | 2015 | Splenic tuberculosis |

| Ballas K et al. [40] | 2005 | Splenic abscess |

| Nikolaidis N et al. [41] | 2005 | Post-traumatic |

| Kryshtalskyi N et al. [42] | 1991 | Splenic abscess |

| Cary ER et al. [27] | 1989 | Crohn’s disease of stomach |

| Glick SN et al. [43] | 1987 | Gastric ulcer perforation |

| Joffe N et al. [44] | 1981 | Gastric ulcer perforation |

| Immelman EJ. et al. [45] | 1975 | Gastric ulcer perforation |

| Stoica T et al. [46] | 1973 | Gastric ulcer perforation |

Table 3.

Presentation characteristics, radiological diagnosis, endoscopic features, surgical treatment, and final HPE in of malignant GSF (22 cases)

| Author / Year | Malignant/ Benign | Site of primary | Cause | CECT Findings | Endoscopic findings | Endoscopic Biopsy | Surgery Done | Chemo | Post-surgery/FINAL HPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dellaportas D et al. (2011) | Malignant | Splenic |

Spontaneous Hematemesis |

Gastrosplenic fistula | Ulcer gastric fundus | Diffuse large B Cell NHL | Enbloc resection |

Given Nature?? |

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (NHL) |

| Moran M et al. (2011) | Malignant | Gastric | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic fistula | Ulcer with fistula gastric fundus | Malignant B cell NHL | Gastrectomy + Splenectomy | CHOP | Malignant B cell NHL |

| Jain V et al. (2011) | Malignant | ? Gastric ?? Splenic |

Spontaneous Melaena |

Gastrosplenic fistula | Ulcer with fistula gastric fundus | Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma | Partial gastrectomy + Splenectomy |

Given Nature?? |

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (both from stomach and spleen) |

| Rothermal LD et al. (2010) | Malignant | Splenic |

Spontaneous Heme positive in stool examination |

Gastrosplenic fistula | Gastric ulcer | Moderate chronic gastritis | Sleeve gastrectomy + splenectomy + liver biopsy | CHOP | Large B cell lymphoma |

| Khan F et al. (2010) | Malignant | Splenic |

Spontaneous hematemesis and melaena |

Gastrosplenic fistula | Irregular Ulcer gastric fundus | Diffuse large B cell lymphoma | Not done | R –CODOXM/VAC regimen | - |

| A García MA et al. (2009) | Malignant | Gastric | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic Fistula | Ulcer greater curve stomach which surrounded a GSF | Chronic gastritis due to H. pylori infection, without malignancy |

Total gastrectomy, splenectomy And distal pancreatectomy |

Given Nature?? |

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (NHL) |

| Maillo C et al. (2009) | Malignant | Splenic |

Spontaneous (gastro-splenic and thoraco-splenic fistula Hematemesis |

Gastrosplenic Fistula | Two regular ulcerated lesions in greater curvature next to cardia | NA | Urgent laparotomy splenectomy, partial gastrectomy,diaphragmatic primary repair, ICD and feeding jejunostomy | Not given | Splenic Large B cell lymphoma |

| Seib CD et al. (2009) | Malignant | Splenic | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic Fistula | Not done | NA | Exploratory laparotomy adhesiolysis, splenectomy, and partial gastrectomy |

Pre op given No post-operative given |

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma classical type nodular-sclerosing |

| Palmowski M et al. (2008) | Malignant | Splenic (diffuse large B cell NHL) | Post-chemotherapy | Follow up CT after chemotherapy showed gastrosplenic fistula | Not done | NA | Splenectomy with resection of greater curvature of stomach |

Pre and post-op R-CHOP regimen |

Normal splenic and gastric parenchyma, only avital tumour cells |

| Aribas BK et al. (2008) | Malignant | Splenic (large B cell NHL) | Post-chemotherapy | Retrograde CT cystography showed gastrosplenic fistula | Not done | NA | Splenectomy, fistula resection and gastric wedge resection |

Pre-op CHOP & MINE |

Splenic abscess |

| Moghazy KM et al. (2008) | Malignant | Splenic (differentiated histiocytic lymphoma) | Post-chemotherapy | Gastrosplenic fistula | Follow up endoscopy showed spontaneous fistula closure | NA | Splenic artery embolization, followed by splenectomy and gastric resection |

Given Nature?? |

NA |

| Al-Ashgar HI et al. (2007) | Malignant | Splenic | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic Fistula | Opening in lateral part of fundus with blind end | NA | laparoscopic excision of fistula tract, partial gastrectomy |

Doxorubicin, bleomycin, Vinblastine Dacarbazine |

Hodgkin’s lymphoma classical type nodular-sclerosing |

| Kerem M et al. (2006) | Malignant | Gastric (diffuse B cell NHL) | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic fistula | Not done | NA | Splenectomy, proximal gastrectomy, oesophagon-eogastrostomy, and pyloroplasty | CHOP | Diffuse B cell NHL |

| Puppala R et al. (2005) | Malignant | Gastric lymphoma | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic fistula | |||||

| Pizzirusso F et al. (2004) | Malignant | Splenic | Post-chemotherapy for Ca colon | Gastrosplenic fistula | Resection of the spleen and the greater gastric curvature |

Adenocarcinoma Colon |

|||

| Choi JE et al. (2002) | Malignant | Splenic | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic Fistula | Deep ulcer like opening in the gastric fundus | Diffuse large cell type malignant lymphoma | Splenectomy, gastric wedge resection, distal pancreactomy |

Pre-op given Nature?? |

Diffuse large cell type malignant lymphoma |

| Bird MA et al. (2002) | Malignant | Splenic |

Spontaneous Hematemesis |

Splenic artery embolization, followed by splenectomy and gastric resection | |||||

| Yang SE et al. (2002) | Malignant | Splenic | Spontaneous | Gastrosplenic Fistula | ulcerated lesions | Diffuse Large B cell Lymphoma (NHL | splenectomy and a partial resection of gastric fundus |

Pre and post-op CHOP |

NA |

| Carolin KA et al. (1997) | Malignant lymphoma | Gastric | Post-chemotherapy | Post-chemo:- evidence of GS fistula |

Pre chemo:- gastric ulcer in fundus Post-chemo follow up: evidence of GS fistula,closed by 4th cycle |

Poorly differentiated large cell lymphoma | Exploratory laparotomy and splenectomy |

Pre-op CHOP |

No evidence of fistula, no malignancy in spleen and lymph nodes |

| Blanchi A et al. (1995) (Case 1) | Malignant | Splenic | Spontaneous | Suspected gastrosplenic fistula | Direct communication between fundus of stomach and ulcerated splenic cavity | NA | Resection of spleen, tail of pancreas and involved stomach |

Given Nature?? |

B cell high grade centroblastic lymphoma |

| Blanchi A et al. (1995) (Case 2) | Malignant | Splenic | Spontaneous | gastrosplenic fistula | Ulcerated cavity fundus | B cell high grade centroblastic lymphoma | Not done |

Given Nature?? |

NA |

| Delgado Sánchez MJ, (1994) | Malignant | Splenic lymphoma | Spontaneous | gastrosplenic fistula |

Discussion

Gastrosplenic fistula (GSF) is one of the rare causes of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. The earliest case of GSF was reported by Scoville et al. in 1962 [5]. They described two patients of GSF due to splenic lymphosarcomas. One was a case of double fistula diagnosed at autopsy, and the other was suspected by virtue of the presence of air within an enlarged spleen at imaging studies, which the authors termed as “aerosplenomegalie.”

GSF can occur due to benign or malignant diseases, the commonest cause reported being a lymphoma of the spleen. Most of the cases were due to lymphomas (86.11%) 31/36. Of all causes of GSF due to lymphomas, the predominant primary site of lymphoma was spleen in 66.67% (24/36) followed by the stomach 16.67% (6/36). In one study, the authors failed to locate whether the source of primary was gastric or splenic in origin [3]. There were 2 cases due to adenocarcinomas [6, 7]. One patient developed GSF due to adenocarcinoma of the colon while receiving postoperative chemotherapy following local excision [8]. Isolated cases of GSF have also been reported due to benign aetiologies, viz, peptic ulcers, Crohn’s disease, trauma, and splenic abscess and splenic tuberculosis (Table 2). We could acquire the details on clinical characteristics, radiological features, pathological diagnoses, and therapeutic procedures in 22 cases of malignant GSF published in literature which have been enumerated in Table 3.

The development of internal fistulation in gastric malignancies is reported to occur in less than 1% of gastric cancers [9, 10]. GSF formation and perforation of viscus are considered to be unfavourable prognostic events, resulting from tumour progression or post-chemotherapy complications [11]. The close proximity of the stomach and spleen as also the presence of a gastrosplenic ligament have been proposed to facilitate the formation of a GSF due to involvement by tumour growth, infection, or necrosis [2, 3, 12]. It is intriguing to note that despite the fact that adenocarcinomas of the stomach are commoner than primary gastric lymphomas, all the cases of malignant gastric GSF reviewed in our series were resultant to lymphomas and only two were due to an adenocarcinoma of the stomach [6]. A probable explanation is the absence of desmoplastic reaction in lymphomas when compared with adenocarcinomas, as also rapid growth and tumour necrosis which occurs in lymphomas [11]. The fistula most often occurs spontaneously as was seen in 75% (27/36) patients reviewed in our series.

Perforation of malignant gastrointestinal lymphomas can occur following chemotherapy in 5% cases [13]. Perforations can occur either into the free peritoneal space or into an adjacent organ [9]. GSF reported after chemotherapy is less common and has been postulated to occur due to rapid lysis of the tumour, i.e., the rate of tumour destruction being far greater than the regenerative capacity of the gastric mucosal cells [12]. It has been postulated that spontaneous GSF secondary to lymphomas of stomach or spleen usually occurs in advanced terminal stage of the illness as opposed to post-chemotherapy GSF [12].

The presentation of GSF is largely innocuous often being incidentally detected in imaging studies for nonspecific abdominal pain with left upper abdominal pain being the most common presenting symptom [14]. Splenomegaly is reported to be present in 85% cases [15]. Unlike GSF resultant to benign aetiologies like peptic ulcer disease which commonly present with gastrointestinal (GI) bleed, malignant GSF infrequently present with clinical features of frank upper GI bleed as was seen in 18% patients in the series. Alternatively, patients can have occult haemorrhage presenting as heme positivity in stools [4]. Rarely, the haemorrhage can be exsanguinating necessitating an urgent angiographic embolization or emergency surgical extirpation to control the bleed [16–19]. Thus, a high index of suspicion of GSF is warranted in all patients with gastric or splenic lymphomas presenting with upper GI haemorrhage [2].

Endoscopy is the initial investigation of choice in patients with upper GI bleed. However, in the diagnosis of GSF, the findings are often deluding and therefore inferior to a CECT. Some authors have questioned the need for endoscopy in cases where the CT diagnosis is obvious [3]. Nevertheless endoscopy is useful for providing supportive evidence and helps in obtaining a biopsy as the lesion often ulcerates the stomach. Details of endoscopy were present in 19 patients in our reviewed series. The classical endoscopic finding is that of an ulcer in the fundus or the greater curvature of the stomach and was seen in most cases. Alternatively, only irregular or distorted gastric folds may be visualized at times converging on the greater curvature to a bright red area with central ooze [9, 12, 20]. Seldom can one visualize the fistulous tract as a direct communication between the stomach and spleen as observed in 26% patients in our review [1, 3, 11, 12, 21]. The site of involvement is usually the fundus or the greater curvature possibly due to the relative proximity of the area to spleen. Endoscopic biopsy when attempted is confirmatory in most cases in the present review [2, 3, 12, 21–24]. Caution should be exercised as the mass could represent a splenic hematoma. Therefore, CECT before the endoscopic biopsy is valuable. Often, the gastric ulcer biopsy was positive irrespective of the primary site, i.e., stomach or spleen. It is noteworthy that most of the tumours were non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), i.e., 63.89% (23/36) particularly of diffuse large B cell type 58.33% (21/36), which is quoted as the commonest type of lymphoma in the stomach, constituting > 95% of all gastric lymphomas [13, 20]. This type of lymphomas is commonly incriminated in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal fistulae by virtue of its aggressive growth pattern and infiltrative nature [9, 22, 24].

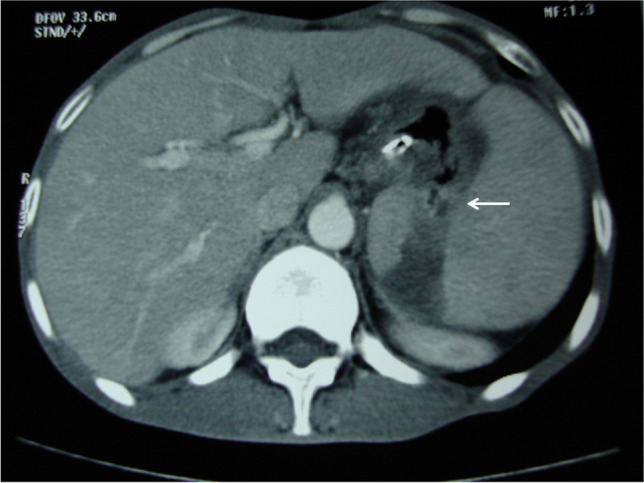

In non-contrast CT, the finding of an air fluid level in the spleen should raise the suspicion [12] CECT is the investigation of choice in the diagnosis of GSF [5, 9, 12, 14, 23, 26]. The classic depiction of a contrast filled tract between the spleen and the stomach is pathognomic of the disease [9, 22] (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, a fair presumption can be made from indirect evidences such as the presence of an oral contrast or air in the spleen, even in the absence of a demonstrable fistula tract. Loss of fat planes between adjacent organs is usually noted which can help in situations where the fistulous tract is not visualized. Rarely, CECT may mimic a splenic abscess and a retrograde CT cystography was deemed helpful [26]. Supportive evidence from an upper GI endoscopy is beneficial in indirect cases. CECT clinched the diagnosis in all except one reported case in the series. Though there was an indirect evidence of splenic enlargement in the patient, no GSF could be identified and patient had repeated episodes of hematemesis or melaena without a definite identifiable source. In one such case, repeated endoscopy, angiography, and isotope scan also failed to detect the source of bleed initially and resulted also in a negative laparotomy. The GSF was suspected subsequently from indirect detection of an area of ooze in endoscopy and confirmed at relaparotomy [19]. Upper gastrointestinal series and barium studies have also been quoted to demonstrate the fistula in an occasional patient [27].

Fig. 2.

CECT showing gastropslenic fistula (arrow)

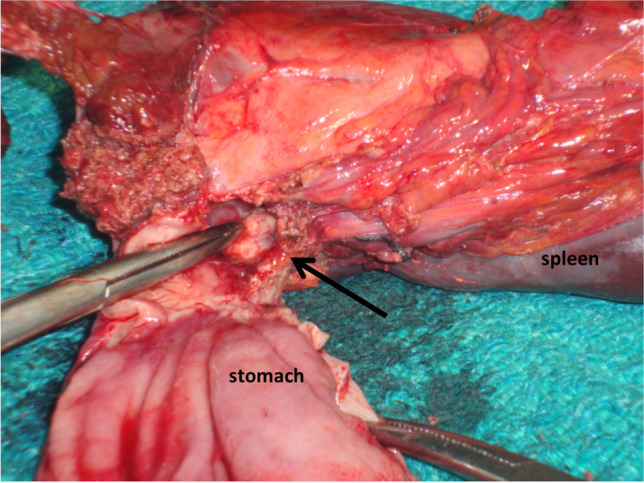

Most authors opted for resectional surgery, viz, resection of spleen along with part or whole of stomach and adjacent organs as the treatment modality for GSF (Fig. 3). Infrequently, an insidiously detected GSF has been treated with chemotherapy alone and followed up with endoscopy but such reports are usually confined to post-chemotherapy GSF and can be considered anecdotal till definitive evidence is available to support the advocacy of non-operative strategies [19, 22, 23] The potential danger imminent in pursuing a non-operative therapy is the risk of it culminating in a catastrophic haemorrhage. It has been reported that gastric juice can cause erosion of splenic vessels and result in massive bleeding [22], requiring emergent surgery or embolization to control bleeding [16, 18, 19]. In one patient, a case of GSF complicating a primary gastric lymphoma, non-operative therapy was adopted in view of associated comorbidities; however, the patient succumbed 2 months following diagnosis [25].

Fig. 3.

Resected specimen showing gastrosplenic fistula (arrow)

Reports exist of upper GI haemorrhage resultant to GSF during chemotherapy in cases of splenic lymphoma raising concerns whether all such cases merit a routine pre-chemotherapy endoscopic evaluation of the stomach [14]. Surgery provides a definitive tissue diagnosis in cases where a prior histological diagnosis could not be ascertained [9]. The extent of gastric resection is controversial with authors variably resorting to a wedge excision, a sleeve resection of greater curvature, or a partial or total gastrectomy. A splenectomy is routinely added to the procedure which may rarely need an additional distal pancreatectomy [1, 9, 24]. However, in one reported case, the authors refrained from a splenectomy and only excision of the fistulous tract along with a partial gastrectomy was performed [28]. Rarely, GSF following chemotherapy has been treated with an isolated splenectomy without gastric resection [23]. Splenic artery embolization followed by splenectomy and gastric resection may be a prudent choice in massive bleed due to a GSF [17, 18]. Though, most authors performed the operation through an open approach; reports of successful excision of the fistulous tract along with gastrectomy using the laparoscopic approach have also been published [29]. It is noteworthy that in most patients undergoing a surgical resection, following chemotherapy residual malignancy is rarely demonstrable [11, 19, 23, 29].

Conclusion

Gastrosplenic fistula is an exceptional complication of malignancies of the gastrointestinal tract. Lymphomas particularly arising from the spleen are the commonest cause. Gastric adenocarcinoma causing GSF is extremely rare. Most cases occur spontaneously, but at times, it can be secondary to tumour necrosis following chemotherapy. CECT is superior to endoscopy in diagnosing GSF and is the investigation of choice. An iconic depiction of the fistulous tract or contrast and air in the spleen is pathognomic. Endoscopy usually demonstrates an ulcer in the region of gastric fundus or greater curvature and can provide with a tissue biopsy prior to definitive management. Most cases are due to NHL, diffuse B cell, or histiocytic type. Resectional surgical therapy is advocated to circumvent acataclysmal bleed and includes splenectomy along with segmental, partial, or total gastrectomy depending on the extent of involvement of the organ. The limitation of this study is that the detailed data of all the reported cases could not be retrieved.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Statement of Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Garcia MA, Bernardos GL, Vaquero RA, MenchénViso L, Turégano FF. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula secondary to primary gastric lymphoma. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:76–78. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082009000100014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dellaportas D, Vezakis A, Fragulidis G, Tasoulis M, Karamitopoulou E, Polydorou A. Gastrosplenic fistula secondary to lymphoma, manifesting as upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 2011, 43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Jain V, Pauli E, Sharzehi K, Moyer M. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula secondary to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:608–609. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothermel LD, Chadwick CL, Thambi-Pillai T. Gastrosplenic fistula: etiologies, diagnostic studies, and surgical management. Int Surg. 2010;95:270–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.deScoville A, Bovy P, Demeester P. Radiologic aerosplenomegaly caused by necrotizing splenic lymphosarcoma with double fistulization into the digestive tract. Acta Gastro-Enterol Belg. 1967;30:841–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krause R, Larsen CR, Scholz FJ. Gastrosplenic fistula: complication of adenocarcinoma of stomach. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1990;14:273–276. doi: 10.1016/0895-6111(90)90009-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez JD, Moya L, Hernandez G, Viola L. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2015;35:165–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pizzirusso F, Gillet JP, Fobe D. Isolated spleen metastatic involvement from a colorectal adenocarcinoma complicated with a gastrosplenic fistula. A case report and literature review. Acta Chir Belg. 2004;104:214–6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Kerem M, Sakrak O, Yilmaz TU, Gultekin FA, Dursun A, Bedirli A. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula in primary gastric lymphoma: surgical management. Asian J Surg. 2006;29:287–290. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60104-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macmahon CE, Lund P: Gastrocolic fistulae of malignant origin. A consideration of its nature and report of five cases. Am J Surg 1963 Aug,106:333–47 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bubenik O, Lopez MJ, Greco AO, Kraybill WG, Cherwitz DL. Gastrosplenic fistula following successful chemotherapy for disseminated histiocytic lymphoma. Cancer. 1983;52(994):6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830915)52:6<994::aid-cncr2820520611>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran M, Bilgiç I, Dizen H, EvrenDilektaşlı, TankutKöseoğlu, Özmen M. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula resulting from primary gastric lymphoma: case report and review of the literature. Balkan Medical Journal 2011;28:205–8

- 13.David M, Mahvi and Seth B. Krantz. Stomach. In Textbook of surgery, The biological basis of modern surgical practice. 19th edition. Edited by Courtney M. Townsend, R. Daniel Beauchamp, B. Mark Evers, Kenneth L. Mattox.Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2012:1182–1226

- 14.Seib CD, Rocha FG, Hwang DG, Shoji BT. Gastrosplenic fistula from Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;10:27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.7695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding YL, Wang SY. Gastrosplenic fistula due to splenic large B-cell lymphoma. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:805–807. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maillo C, Bau J. Gastrosplenic and thoracosplenic fistula due to primary untreated splenic lymphoma. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2009;101:222–223. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082009000300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moghazy KM. Gastrosplenic fistula following chemotherapy for lymphoma. Gulf J Oncolog. 2008;3:64–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bird MA, Amjadi D, Behrns KE. Primary splenic lymphoma complicated by hematemesis and gastric erosion. South Med J. 2002;95:941–942. doi: 10.1097/00007611-200295080-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiltunen KM, Airo I, Mattila J, Helve O. Massively bleeding gastrosplenic fistula following cytostatic chemotherapy of a malignant lymphoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:478–481. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199108000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Julian A. Abrams, Timothy C. Wang. From adenocarcinoma and other tumours of the stomach.In Gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology/diagnosis/management. Volume 1. 9th edition.Edited by Mark Feldman, Lawrence S.Friedman, Lawrence J Brandt. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:887–906

- 21.Blanchi A, Bour B, Alami O. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula revealing high-grade centroblastic lymphoma: endoscopic findings. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:587–589. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(95)70017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan F, Vessal S, McKimm E, D'Souza R. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula secondary to primary splenic lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2010:bcr0420102932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Carolin KA, Prakash SH, Silva YJ. Gastrosplenic fistulas: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 1997;63:1007–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi JE, Chung HJ, Lee HG. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula: a rare complication of splenic diffuse large cell lymphoma. Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:728–730. doi: 10.1007/s00261-002-0011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puppala R, Harvey Wl. Spontaneous gastrosplenic fistula in primary gastric lymphoma: case report and review of literature. Clin Radiol Extra. 2005; 60:20–2

- 26.Aribaş BK, Başkan E, Altinyollar H, Ungül U, Cengız A, Erdıl HF. Gastrosplenic fistula due to splenic large cell lymphoma diagnosed by percutaneous drainage before surgical treatment. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19:69–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cary ER, Tremaine WJ, Banks PM, Nagorney DM. Isolated Crohn’s disease of the stomach. Mayo Clin Proc. 1989;64:776–779. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)61750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Ashgar HI, Khan MQ, Ghamdi AM, Bamehriz FY, Maghfoor I. Gastrosplenic fistula in Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated successfully by laparoscopic surgery and chemotherapy. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:1898–1900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmowski M, Zechmann C, Satzl S, et al. Large gastrosplenic fistula after effective treatment of abdominal diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:337–338. doi: 10.1007/s00277-007-0404-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyang LS, Gosal P, Na A, Cox MR, Devadas M (2020) Gastrosplenic fistula due to primary splenic lymphoma. ANZ J Surg. 10.1111/ans.16340 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Yokoyama Y, Kashyap S, Ewing E, Block R (2020) Gastrosplenic fistula secondary to non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma. J Surg case Rep. 10.1093/jscr/rjz376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Saito M, Miyashita K, Miura Y, Harada S, Ogasawara R, Izumiyama K, et al. Successful treatment of gastrosplenic fistula arising from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with chemotherapy: two case reports. Case Rep Oncol. 2019;12:376–383. doi: 10.1159/000500505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang DH, Huh J, Lee JH, Jeong YK, Cha HJ. Gastrosplenic fistula occurring in lymphoma patients: systematic review with a new case of extranodal NK T-cell lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6491–6499. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i35.6491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gentilli S, Oldani O, Zanni M, Ferreri E, Terrone A, Valente G, et al. Gastrosplenic fistula as a complication of chemotherapy for large B-cell lymphoma. Ann Ital Chir.2016;26:87:S2239253X16025731 [PubMed]

- 35.Senapati J, Devasia AJ, Sudhakar S, Viswabandya A. Asymptomatic gastrosplenic fistula in a patient with marginal zonal lymphoma transformed to diffuse large B cell lymphoma- a case report and review of literature. Ann Hematol. 2014;93:1599–1602. doi: 10.1007/s00277-013-1986-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Delgado Sanchez MJ, Bernardos Rodriguez A, Serrano Diez-Canedo J, Buezas Martinez G, Alamo JC. Gastrosplenic fistula from primary lymphoma of the spleen. Rev Enferm Dig. 1994;86:543–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harris NL, Aisenberg AC, Meyer JE, Ellman L, Elman A: Diffuse large cell (histiocytic) lymphoma of the spleen. Clinical and pathological characteristic of ten cases. Cancer. 1984,142:711–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Leeds IL, Haut ER, Barnett CC. Splenic abscess complicated by gastrosplenic fistula. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81:612–614. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee KJ, Yoo JS, Jeon H, Cho SK, Lee JH, Ha SS, et al. A case of splenic tuberculosis forming a Gastrosplenic fistula. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015;66:168–171. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2015.66.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ballas K, Rafailidis S, Demertzidis C, Eugenidis N, Alatsakis M, Zafiriadou E, et al. Gastrosplenic fistula: a rare complication of splenic abscess. Surg Pract. 2005;9:153–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-1633.2005.00269.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nikolaidis N, Giouleme O, Gkisakis D, Grammatikos N. Posttraumatic splenic abscess with gastrosplenic fistula. GastrointestEndosc. 2005;61:771–772. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02836-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kryshtalskyi N, Shafir MS. Splenic abscess with gastrosplenic fistula. Can Fam Physician. 1991;37:465–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glick SN, Levine MS, Teplick SK, Gasparaitis A. Splenic penetration by benign gastric ulcer: Preoperative recognition with C T. Radiology. 1987;163:637–639. doi: 10.1148/radiology.163.3.3575707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joffe N, Antonioli DA. Penetration into spleen by benign gastric ulcer. Clin Radiol. 1981;32:177–181. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(81)80155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Immelman EJ. Rupture of a subcapsular hematoma of the spleen resulting from a penetrating gastric ulcer. South Afr J Surg. 1975;13:261–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stoica T, Dragomir T, Gabrovescu D, Laky D, Marinescu M. Ulcer of the fornix perforated into the spleen, simulating a gastric diverticulum. Chirurgia (Bucur) 1973;22(509):12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]