Abstract

Escherichia coli cells, the outer membrane of which is permeabilized with EDTA, release a specific subset of cytoplasmic proteins upon a sudden drop in osmolarity in the surrounding medium. This subset includes EF-Tu, thioredoxin, and DnaK among other proteins, and comprises ∼10% of the total bacterial protein content. As we demonstrate here, the same proteins are released from electroporated E. coli cells pretreated with EDTA. Although known for several decades, the phenomenon of selective release of proteins has received no satisfactory explanation. Here we show that the subset of released proteins is almost identical to the subset of proteins that are able to pass through a 100-kDa-cutoff cellulose membrane upon molecular filtration of an E. coli homogenate. This finding indicates that in osmotically shocked or electroporated bacteria, proteins are strained through a molecular sieve formed by the transiently damaged bacterial envelope. As a result, proteins of small native sizes are selectively released, whereas large proteins and large protein complexes are retained by bacterial cells.

The procedure of osmotic shock was originally introduced for the purpose of extracting periplasmic enzymes of Escherichia coli (20). In this procedure, bacterial cells are preincubated in a hyperosmotic sucrose solution supplemented with EDTA to permeabilize their outer membrane and then transferred into a solution of low osmolarity. The resulting osmotic pressure within shocked cells was believed to cause extrusion of the contents of the periplasm. Later experiments have shown, however, that osmotically shocked bacteria, while remaining viable, also release a number of cytoplasmic molecules, including ions, metabolites (22), and certain proteins. In fact, the major protein released from the shocked cells is a cytoplasmic constituent, translation elongation factor EF-Tu, at least half of which is extracted by the osmotic shock procedure (12, 13). The subset of released cytoplasmic proteins also includes thioredoxin (1, 17), molecular chaperone DnaK (6, 8), and proteins involved in the biosynthesis of enterobactin (9), among others (5). Some foreign proteins expressed in the cytoplasm of E. coli have also been successfully extracted by the osmotic shock procedure (16, 23).

It has been unclear what determines the selectivity of protein release from osmotically shocked bacteria, since the released cytoplasmic proteins share no apparent common characteristics distinguishing them from the majority of proteins, which are retained by the cells. How these proteins leave the cytoplasm in the absence of cell lysis has also remained an enigma. The most frequently entertained hypothesis postulates that these proteins normally concentrate in a hypothetical “osmotically sensitive compartment” of the bacterial cytoplasm, which is presumably adjacent to the zones of adhesion between the plasma membrane and the outer membrane and, therefore, is selectively extruded from the shocked cells (4, 8–10, 18, 23). This hypothesis leaves open, however, a seemingly intractable question about the molecular mechanism of compartmentalization of highly soluble proteins in a specific cytoplasmic region. Here we demonstrate that the selective release of cytoplasmic proteins from osmotically shocked E. coli has a much simpler explanation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Cells of E. coli strain LMG194 (F− ΔlacX74 galE thi rpsL ΔphoA Δara714 leu::Tn10), which were used in the majority of experiments, were obtained from Invitrogen. Strain AW405 (F− galK2 galT1 lacY1 mtl-1 xyl-5 hisG4 leuB6 thr-1 sup tonA31/T5 tsx-78 prsL136) and its derivative, PB103, containing an ΩCmr marker inserted into the mscL gene, were obtained from either S. Sukharev (University of Maryland) or A. Ghazi (Universite Paris-Sud, Orsay, France) and, regardless of the source, gave identical results. Disruption of the mscL gene in PB103 was confirmed by PCR, using primers corresponding to the sequences flanking the gene. Plasmids expressing E. coli proteins TrxA, TrxC, GrxA, FolA, and CheY were constructed on the basis of the expression vector pSE420 (Invitrogen), containing the trc promoter. The DNA fragments coding for these proteins were amplified by PCR, with LMG194 E. coli chromosomal DNA as a template, and cloned into the multicloning site of the vector in such a way that the initiator methionine codon was placed under control of the ribosome-binding site of the vector.

Overexpression of proteins.

LMG194 cells transformed with the plasmids described above were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 1% NaCl) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.3, at which point isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was added to a 100 μM concentration to induce protein expression. Incubation continued for 1.5 h in a room temperature shaker. The low temperature at the expression stage was necessary to prevent aggregation of some of the proteins (GrxA, TrxC, and CheY).

Osmotic shock fractions.

Unless indicated otherwise, cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.8, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended to an OD600 of 10 in 10 ml of ice-cold TSE buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 20% sucrose, 2.5 mM Na-EDTA). After a 10-min incubation on ice, cells were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 5,000 × g at 4°C, resuspended in 10 ml of ice-cold water, and, 10 min later, centrifuged again. The supernatant, containing released proteins, was saved for electrophoretic analysis. The cell pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of TE (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 2.5 mM Na-EDTA) and homogenized in a French press cell (Aminco) at 16,000 lb/in2. To analyze total proteins of untreated cells, they were directly resuspended in 10 ml of TE and subjected to the French press homogenization.

Homogenate fractions.

LMG194 cells grown to an OD600 of 0.8 were collected by centrifugation and resuspended to an OD600 of 10 in either TE or TM (10 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.5], 2.5 mM MgCl2). Ten milliliters of the suspension was homogenized in a French press as described above. In some experiments, 10 ml of the homogenate in TM was supplemented with 10 U of RQ1 RNase-free DNase I (Promega), and this mixture was then incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The homogenates were clarified by 15 min of centrifugation at 12,000 × g. One milliliter of a clarified homogenate was loaded into a 100-kDa-cutoff Centricon YM-100 molecular filtration device (Amicon catalog no. 4211) and centrifuged for 5 min in a Beckman JA20 rotor at 2,500 rpm (760 × g). The filtrate was collected and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. The short time of centrifugation was chosen to avoid significant changes of protein concentrations in the homogenate in the course of ultrafiltration; during this time, only ∼20% of the volume passed through the membrane filter. Longer centrifugation time (30 min) resulted in at least 80% passage of the homogenate volume through the filter, thus indicating that the membrane remained unclogged in the course of ultrafiltration. In some experiments, Centricon YM-50 and Nanosep 300 (Pall Gelman) devices were used instead of Centricon YM-100. In these cases, centrifugation was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, but for a shorter period (5 min).

Measurements of dihydrofolate reductase activity.

Dihydrofolate reductase activity in the protein fractions, obtained as described above, was measured as described in reference 11 by monitoring the decrease in the A340 of NADPH in the presence of dihydrofolate. One enzymatic unit corresponds to the oxidation of 1 μmol of NADPH per min.

Periplasmic fraction.

The fraction of periplasmic proteins was obtained by spheroplasting bacteria by lysozyme-EDTA treatment under isotonic conditions according to the procedure of Kaback (14). Specifically, LMG194 cells grown in LB medium to an OD600 of 0.8 were collected by centrifugation and resuspended to an OD600 of 10 in a buffer containing 30 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 20% sucrose, and 10 mM Na-EDTA. Lysozyme (L6876; Sigma) was added to 50 μg/ml, and cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature; during this time, 98 to 99% of them became spheroplasts. The latter were pelleted by 15 min of centrifugation at 3,000 × g, and the supernatant containing periplasmic proteins was collected for electrophoretic analysis.

Electroporation.

Cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.8, harvested by centrifugation, and resuspended to an OD600 of 10 in 1 ml of ice-cold TE buffer to permeabilize the outer membrane. After 10 min, cells were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 1 min and resuspended in 1 ml of either ice-cold water or 20% sucrose. One hundred microliters of cell suspension was placed into an ice-cold Bio-Rad electroporation cuvette (2-mm gap) and electroporated at 2.5 kV with a BTX E. coli TransPorator. The electroporated cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 1 min, and the supernatant was collected for electrophoretic analysis.

Electrophoretic analysis of proteins.

Twelve microliters of each protein fraction was supplemented with 4 μl of 4× sample buffer and analyzed by standard Laemmli sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) electrophoresis in 18% (in Fig. 2) or 15% (other figures) polyacrylamide gels in a Bio-Rad Mini-PROTEAN II apparatus. Since cell concentrations were kept identical throughout all manipulations, each lane contained proteins obtained from the same number of cells (∼5 × 108). Gels were stained with Coomassie blue R-250. Either Bio-Rad Precision protein standards or Bio-Rad Low Range standards were used as molecular weight markers. To perform N-terminal sequencing, proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane according to a standard protocol and stained with Coomassie blue, and the bands of interest were excised and sequenced at the Protein Analysis Facility of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

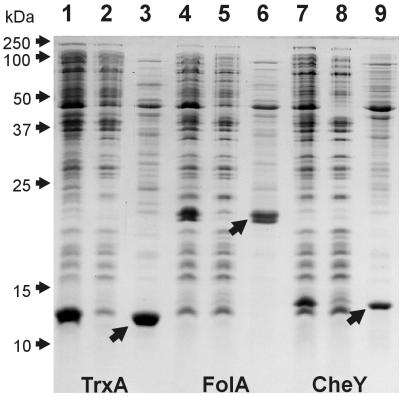

FIG. 2.

Expression and osmotic shock-induced release of plasmid-encoded thioredoxin (TrxA; lanes 1 to 3), dihydrofolate reductase (FolA; lanes 4 to 6), and CheY (lanes 7 to 9). Lanes 1, 4, and 7 contain total cell lysates. Lanes 2, 5, and 8 contain lysates of osmotically shocked cells. Lanes 3, 6, and 9 contain osmotic shock extracts. Arrows point at overexpressed proteins.

Western blotting of thioredoxin.

Thioredoxin was revealed in a nitrocellulose blot of an electrophoresis gel by using Sigma rabbit anti-thioredoxin antibody (T-0803) followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (A-0545). Peroxidase was visualized by using Renaissance Western blot chemiluminescence reagent (NEN Life Science). Incubation with antibodies was performed in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 1% fat-free dry milk.

Image analysis.

Coomassie blue-stained gels were digitally photographed with Kodak Electrophoresis Documentation System 120, and the gray-scale TIFF files obtained were quantified with Adobe Photoshop 5.0 software. To do this, an Invert command was applied to an entire image, and then the intensity of Coomassie staining within a selected image window was measured by determining mean pixel value of a window by using the Image Histogram function of the software. The ratios of the staining intensities of neighboring electrophoresis lanes were determined after subtraction of background values measured in a space between lanes.

RESULTS

Selective release of cytoplasmic proteins from osmotically shocked E. coli

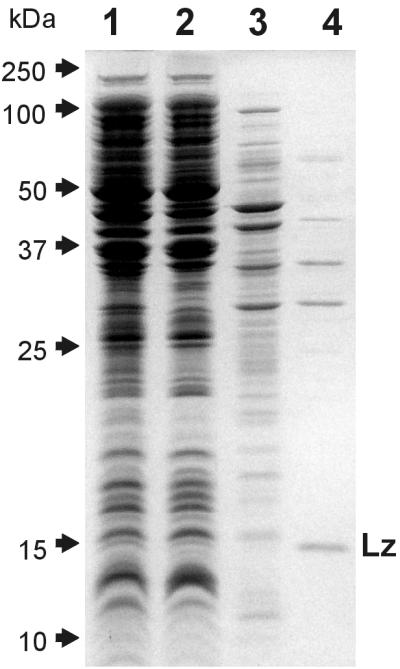

Figure 1 illustrates the essence of the phenomenon analyzed in this work. After E. coli cells were subjected to the osmotic shock procedure, a majority of E. coli polypeptides (lane 1) were retained by cells (lane 2), whereas a small subset comprising approximately 10% of the bacterial protein content was released (lane 3). Only some of the released polypeptides represent periplasmic constituents (lane 4), while the rest of them apparently have a cytoplasmic origin.

FIG. 1.

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of total E. coli proteins (lane 1), proteins retained (lane 2) and released (lane 3) by osmotically shocked cells, and periplasmic proteins released upon converting E. coli cells into spheroplasts (lane 4). All lanes contain protein fractions obtained from the same number of cells. Lz indicates the band of lysozyme that was used for preparing spheroplasts.

In order to analyze the behavior of individual cytoplasmic proteins during osmotic shock, we used the plasmid expression vector pSE420 to overexpress five E. coli proteins: thioredoxin (TrxA), thioredoxin 2 (TrxC), glutaredoxin (GrxA), dihydrofolate reductase (FolA), and chemotaxis signaling protein CheY. In full agreement with previous reports (16, 18), overexpressed thioredoxin was quantitatively released by osmotically shocked cells (Fig. 2, lanes 1 to 3). To our surprise, all four other proteins studied behaved in a similar way: they were almost completely extracted by the osmotic shock procedure. The results for FolA and CheY are presented in Fig. 2, lanes 4 to 9.

The release of the five overexpressed proteins from osmotically shocked cells was in clear contrast with the behavior of the majority of E. coli polypeptides, which were largely retained by the cells. The unusual behavior of these proteins could hardly be explained by the compartmentalization hypothesis frequently invoked to rationalize the selective release of other proteins (see the introduction). Indeed, it would be a rather improbable coincidence if all five tested proteins were compartmentalized in the same osmotically sensitive region of the cytoplasm. In search of the explanation, we considered two characteristics that are shared by the five proteins.

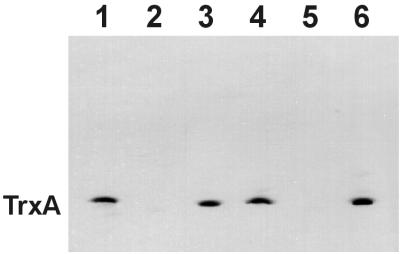

One such common characteristic was the fact that, in our experiments, these proteins were expressed at levels far exceeding their natural expression levels. Western blotting analysis demonstrated, however, that thioredoxin, even at a naturally expressed level, was extracted from osmotically shocked bacteria with remarkable efficiency (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 3), in full agreement with previous reports (1, 17). The behavior of naturally expressed FolA was assessed by comparison of dihydrofolate reductase activity in the total homogenate of wild-type E. coli cells with that in the osmotic shock extract. The results (2.60 U/1012 cells in the homogenate and 1.67 U/1012 cells in the extract) indicate that 65% of FolA is released from shocked cells. It appears, therefore, that overexpression of the tested proteins was not the reason for their high extractability by the osmotic shock procedure.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of thioredoxin (TrxA) release from osmotically shocked wild-type E. coli strain AW405 (lanes 1 to 3) and the MscL knockout strain PB103 (lanes 4 to 6). Lanes 1 and 4 contain total cell lysates. Lanes 2 and 5 contain lysates of osmotically shocked cells. Lanes 3 and 6 contain osmotic shock extracts.

The other common property of the five proteins tested was their small size: all of them are monomeric proteins with molecular masses of only 9 to 18 kDa. Admittedly, the hypothesis that the release of proteins by osmotically shocked cells is determined by their size seems to contradict the results presented in Fig. 1. The subsets of retained (Fig. 1, lane 2) and released (Fig. 1, lane 3) proteins include polypeptides with a broad range of molecular masses and do not appear to differ in the average protein size. It should be noted, however, that SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis reveals molecular weights of unfolded individual polypeptides rather than of native proteins. In their native state, polypeptides can form intermolecular complexes or can be engaged in large macromolecular structures, thus increasing their effective sizes. The experiments presented below demonstrate that, indeed, SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis creates an erroneous impression about the size distribution of proteins and that the native sizes of the released and retained proteins actually differ.

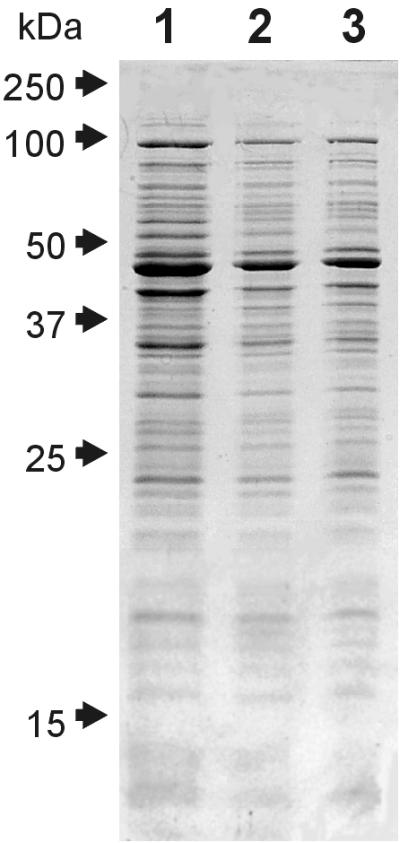

Molecular sieve mechanism of selective protein release.

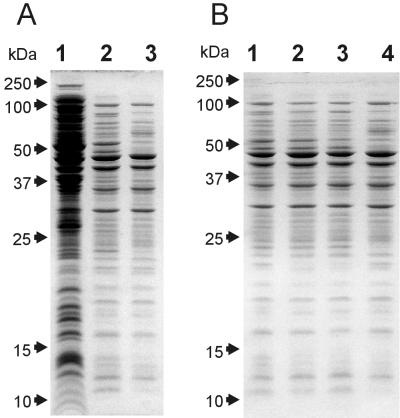

In order to separate E. coli proteins by their native sizes, we performed molecular filtration of an E. coli homogenate through a cellulose membrane with a 100-kDa molecular mass cutoff (Fig. 4A). Only a small subset of total proteins of the homogenate passed through the membrane (compare lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 4A). This subset of filterable polypeptides remained essentially the same, with noticeable differences in only a few minor bands, whether the homogenate was prepared in the presence of EDTA, MgCl2, or MgCl2 plus DNase (Fig. 4B, lanes 1 to 3).

FIG. 4.

Similarity of protein composition of a 100-kDa membrane filtrate of an E. coli homogenate and an osmotic shock extract. Lanes contain clarified E. coli homogenate in Tris-EDTA buffer (A, lane 1); a 100-kDa filtrate of a homogenate obtained in Tris-EDTA buffer (A, lane 2; B, lane 1), Tris-MgCl2 buffer (B, lane 2), or Tris-MgCl2 buffer containing DNase (B, lane 3); and an osmotic shock extract (A, lane 3; B, lane 4). All lanes contain protein fractions obtained from the same number of cells.

The major finding of our work is that this subset of filterable polypeptides is strikingly similar to the subset of polypeptides released from osmotically shocked E. coli cells (compare lanes 2 and 3 in Fig. 4A, lanes 1 to 3 and 4 in Fig. 4B, or lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 5). In contrast, the filtrate obtained with a 300-kDa- cutoff membrane contained many more proteins than the osmotic shock extract, whereas a membrane with a nominal 50-kDa cutoff allowed the passage of only a very few proteins (data not shown). It appears, therefore, that osmotic shock causes selective release of proteins that can pass through a 100-kDa-cutoff membrane. In accordance with this conclusion, lanes 2 and 3 of Fig. 5 demonstrate that only a small fraction of polypeptides that can pass through such a membrane are retained by osmotically shocked cells. The extent of this retention varies substantially between individual polypeptides, although there is a clear general tendency toward a higher level of retention for polypeptides with higher molecular masses (Fig. 5, chart).

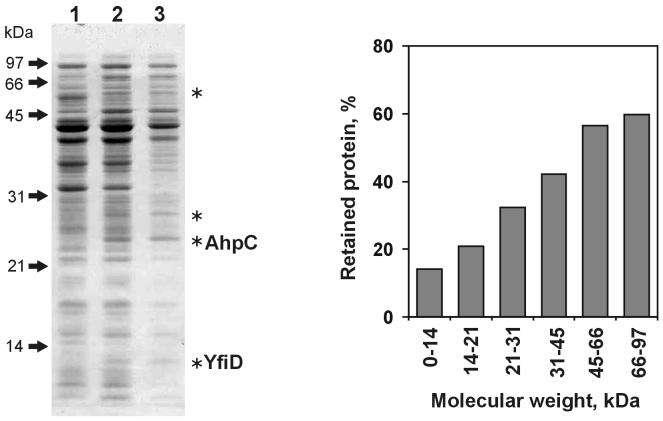

FIG. 5.

Partial retention of filterable polypeptides in osmotically shocked E. coli cells and its dependence on the molecular mass of a polypeptide. Lanes contain protein fractions obtained from the same number of cells: osmotic shock extract (lane 1), a 100-kDa filtrate of an E. coli homogenate (lane 2), and a 100-kDa filtrate of a homogenate obtained from osmotically shocked E. coli (lane 3). The chart shows the results of image analysis of lanes 2 and 3 of the gel and reflects the ratio of staining intensity of lane 3 to that in lane 2 in different regions of the gel. Image analysis was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Asterisks indicate proteins represented in lane 2 in significantly larger amounts than in lane 1. AhpC and YfiD indicate two such proteins, whose identity was determined by N-terminal sequencing (see text).

A small number of polypeptides, indicated in Fig. 5, behaved aberrantly: they passed through the membrane filter in the cell homogenate, but were absent in the osmotic shock extract and were completely retained by shocked bacteria. The N-terminal amino acid sequencing of one of such aberrant polypeptide identified it as the alkyl hydroperoxidase AhpC: the first seven residues of the sequenced polypeptide (SLINTKI) exactly corresponded to residues 2 to 8 of AhpC. The second aberrant polypeptide yielded the N-terminal sequence MITGIQI, which unequivocally identified it as YfiD, a putative glycyl radical protein (21). The possible reasons for the unusual behavior of these two polypeptides are presented in the Discussion section.

With the exception of several aberrant polypeptides, the protein fractions obtained by two very different procedures, osmotic shock extraction and molecular filtration of bacterial homogenate, are remarkably similar both qualitatively and quantitatively. The only conceivable explanation of this result is that the selective release of proteins from osmotically shocked cells is fundamentally similar to the filtration process and is based on molecular sieving. While proteins with small native sizes penetrate the hypothetical sieve and get released, large proteins and protein complexes remain inside shocked cells.

The nature of the molecular sieve determining the size of released proteins.

It has been reported recently that the genetic knockout of the osmotically regulated membrane channel MscL impairs the release of EF-Tu, DnaK, and thioredoxin from osmotically shocked E. coli cells, leading to the suggestion that proteins exit shocked cells directly through the MscL channel (1, 6). MscL therefore could potentially serve as a sieve defining the size of proteins released during osmotic shock. In our experiments, we used the same MscL knockout and control E. coli strains as those used in references 1 and 6, but were unable to detect any difference in the spectra or quantities of the released polypeptides (data not shown). The release of thioredoxin was also not affected by the disruption of the mscL gene (Fig. 3), thus directly contradicting the results presented in reference 1. Although the cause of this discrepancy remains unknown, it is clear that MscL cannot be the major factor defining the process of selective protein release.

An important clue to the identity of the molecular sieve is presented by the finding that electroporation of cells leads to the release of the same subset of proteins released by osmotic shock. In these experiments, cells were preincubated with EDTA to permeabilize the outer membrane, washed, and electroporated under the conditions traditionally used for transforming E. coli with plasmid DNA. Although without EDTA pretreatment or application of an electric pulse, cells released no proteins (not shown), Fig. 6 shows that electroporated EDTA-treated cells released the same polypeptides as osmotically shocked cells, albeit with somewhat less efficiency. When electroporation was applied to the E. coli strain overexpressing thioredoxin, only approximately half of the thioredoxin was released from the cells (data not shown). Importantly, the release of proteins from electroporated cells did not depend on the osmolarity of the medium: cells electroporated in water or in 20% sucrose released the same polypeptides with equal efficiency (lanes 2 and 3 in Fig. 5). This result demonstrates that electroporation, although giving qualitatively the same result as osmotic shock, is unlikely to do so by creating similar transmembrane osmotic gradients.

FIG. 6.

Similarity of proteins released by osmotically shocked E. coli (lane 1) and proteins released by EDTA-treated E. coli electroporated in either water (lane 2) or 20% sucrose (lane 3). All lanes contain protein fractions obtained from the same number of cells.

It is well established that electroporation causes formation of transient pores in biological membranes (19, 24). In view of the similarity in protein release between the two procedures, it is tempting to speculate that osmotic shock also causes transient perforation of the plasma membrane. This would allow cytoplasmic proteins to come into direct contact with the peptidoglycan mesh surrounding the E. coli cell. As described in some detail below, we hypothesize that it is this mesh that serves as a sieve responsible for the selectivity of protein release from osmotically shocked or electroporated bacterial cells.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed a previously unnoticed strong correlation between the behavior of E. coli proteins during the osmotic shock procedure and their ability to pass through a 100-kDa-cutoff membrane filter: filterable proteins, with only a few exceptions, are largely released by cells undergoing osmotic shock, while nonfilterable proteins are retained. This correlation can hardly be explained by the previously proposed cytoplasm compartmentalization hypothesis (see the introduction). In fact, there appears to be only one reasonable explanation for the discovered correlation: namely, that in osmotically shocked cells, cytoplasmic proteins are strained through a molecular sieve, presumably formed by the damaged bacterial envelope, thus being separated according to their native sizes. The sizes of the majority of proteins and protein complexes formed by E. coli polypeptides apparently exceed the cutoff value of the sieve formed in osmotically shocked cells (∼100 kDa), thus leading to retention of ∼90% of the total protein content and preservation of cell viability.

The molecular sieve mechanism of protein release is strongly supported by the finding that, even among proteins that can pass through a 100-kDa membrane filter, there is a direct correlation between the size of polypeptides and the extent to which they are retained by shocked cells (Fig. 5). This correlation has a general character, but is not absolute: individual polypeptides of similar molecular masses demonstrate great variability in the extent of retention. This variability is likely due to differences in the shapes of folded polypeptides, which should affect their passage through a sieve, and, to an even larger extent, differences in the formation of protein complexes.

The existence of several aberrant polypeptides, such as AhpC and YfiD, which are retained by osmotically shocked cells but pass through a membrane filter in the homogenate, does not contradict the proposed molecular sieve mechanism of protein release. It has been shown that AhpC of Amphibacillus xylanus, a close homolog of the E. coli AhpC, forms decamers that easily dissociate into dimers (15). Apparently, inside the cell, the E. coli AhpC also exists as a decamer and is too large (∼210 kDa) to exit from osmotically shocked cells, whereas in the homogenate, it dissociates into dimers (∼42 kDa) that are able to pass through the 100-kDa-cutoff membrane filter. The second aberrant polypeptide, YfiD, is highly homologous to C-terminal glycyl radical-forming domains of large enzymes: pyruvate formate lyase and ribonucleotide reductase (21). This homology suggests that YfiD may form a complex with an unidentified E. coli protein or proteins to yield an enzyme of yet unknown function. If this complex dissociates in the homogenate, this would explain the aberrant behavior of YfiD in our experiments. Other aberrant polypeptides are also likely to form multimolecular complexes that dissociate upon dilution in the cell homogenate, thus enabling them to pass through the membrane filter.

The proposed molecular sieve mechanism of selective protein release is in good agreement with the majority of results obtained in the previous studies of the osmotic shock phenomenon, with only a few notable exceptions. Specifically, osmotically shocked cells have been shown to retain a small (8.5-kDa) soluble acyl carrier protein (9), thus seemingly contradicting our conclusion. However, this protein might be prevented from exiting cells by binding the plasma membrane (2, 3). The other apparent contradiction is presented by a large EntF polypeptide (142 kDa) that was shown to be partially released upon osmotic shock (9). It is easy to imagine, however, that a multidomain EntF may have an elongated or even flexible shape that would allow it to pass through a molecular sieve with a nominal 100-kDa cutoff. Indeed, polypeptides with molecular masses of up to ∼150 kDa can be detected in both the osmotic shock extract and the 100-kDa filtrate of the bacterial homogenate (Fig. 4 and 5).

The exact nature of the molecular sieve through which proteins have to pass in order to leave osmotically shocked cells is unknown. An interesting clue is provided by our finding that electroporation of cells, known to generate transient pores in biological membranes (19, 24), causes selective release of the same subset of proteins, presumably passing through the same molecular sieve. Furthermore, solutions containing EDTA and a membrane-permeabilizing agent, such as Triton X-100 or polymyxin B, have been reported to extract from E. coli the same proteins as the osmotic shock procedure (23). It is tempting to speculate that the sudden swelling of the cytoplasm in osmotically shocked cells also leads to transient perforation of the plasma membrane. Because membrane holes created by these diverse treatments are unlikely to have similar sizes, we hypothesize that, regardless of the mechanism of membrane permeabilization, the role of a sieve is played by the peptidoglycan mesh that encases each E. coli cell and to which cytoplasmic proteins would become exposed when the plasma membrane is perforated. Globular proteins of up to 25 kDa have been shown to readily penetrate isolated peptidoglycan sacculi (7). Considering that in a living bacterial cell the peptidoglycan mesh is stretched by the enclosed cytoplasm, it can actually be comparable in porosity to the 100-kDa-cutoff cellulose membrane.

Direct verification of the sieving role of peptidoglycan in osmotically shocked or electroporated cells would require additional experiments. We doubt, however, that identification of the molecular nature of the sieve is a worthy task. Indeed, our results demonstrate that the selective release of proteins from osmotically shocked bacteria, contrary to what was suspected before (1, 4, 6, 8–10, 16–18, 23), has a trivial explanation and perhaps limited biological importance.

The positive aspect of our results is the notion that the very simple osmotic shock procedure can be used as a first step in purification of any small protein produced in E. coli, unless this protein forms aggregates or becomes engaged in complexes with E. coli proteins. From the basic science standpoint, our results suggest that either osmotic shock or electroporation can be used to assess the quaternary structure of polypeptides in live bacteria. The experiments presented here have already yielded several interesting observations. In particular, it appears that only a surprisingly small fraction of E. coli proteins have a native size of less than ∼100 kDa. Another unexpected finding is that apparently only a few polypeptide complexes, exemplified by AhpC and YfiD, dissociate upon homogenization of cells, which in our experiments involved dilution of the cytoplasm by as much as ∼200-fold. These observations may become a starting point for a detailed investigation into the molecular organization of the cytoplasm of live bacteria.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Science Foundation grants 9729204 and 9816872.

We thank A. S. Mankin (University of Illinois) for helpful discussions and an important suggestion and Hyunyoung Jeong for participation in some experiments. We are grateful to S. Sukharev and A. Ghazi for donation of bacterial strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajouz B, Berrier C, Garrigues A, Besnard M, Ghazi A. Release of thioredoxin via the mechanosensitive channel MscL during osmotic downshock of Escherichia coli cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26670–26674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bayan N, Therisod H. Membrane-binding sites for acyl carrier protein in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1989;253:221–225. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80963-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayan N, Therisod H. Photoaffinity cross-linking of acyl carrier protein to Escherichia coli membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1123:191–197. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(92)90111-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayer E M, Bayer M H, Lunn C A, Pigiet V P. Association of thioredoxin with the inner membrane and adhesion sites in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:2659–2666. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.6.2659-2666.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beacham I R. Periplasmic enzymes in Gram-negative bacteria. Int J Biochem. 1979;10:877–883. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(79)90117-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berrier C, Garrigues A, Richarme G, Ghazi A. Elongation factor Tu and DnaK are transferred from the cytoplasm to the periplasm of Escherichia coli during osmotic downshock presumably via the mechanosensitive channel MscL. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:248–251. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.1.248-251.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demchick P, Koch A L. The permeability of the wall fabric of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:768–773. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.768-773.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El Yaagoubi A, Kohiyama M, Richarme G. Localization of DnaK (chaperone 70) from Escherichia coli in an osmotic-shock-sensitive compartment of the cytoplasm. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7074–7078. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7074-7078.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hantash F M, Ammerlaan M, Earhart C F. Enterobactin synthase polypeptides of Escherichia coli are present in an osmotic-shock-sensitive cytoplasmic locality. Microbiology. 1997;143:147–156. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-1-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hantash F M, Earhart C F. Membrane association of the Escherichia coli enterobactin synthase proteins EntB/G, EntE, and EntF. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1768–1773. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.6.1768-1773.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwakura M, Shimura Y, Tsuda K. Cloning of dihydrofolate reductase gene of Escherichia coli K12. J Biochem. 1982;91:1205–1212. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a133804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson G R, Rosenbusch J P. Abundance and membrane association of elongation factor Tu in E. coli. Nature. 1976;261:23–26. doi: 10.1038/261023a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson G R, Takacs B J, Rosenbusch J P. Properties of a major protein released from Escherichia coli by osmotic shock. Biochemistry. 1976;15:2297–2303. doi: 10.1021/bi00656a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaback H R. Bacterial membranes. Methods Enzymol. 1971;22:99–120. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitano K, Niimura Y, Nishiyama Y, Miki K. Stimulation of peroxidase activity by decamerization related to ionic strength: AhpC protein from Amphibacillus xylanus. J Biochem. 1999;126:313–319. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaVallie E R, DiBlasio E A, Kovacic S, Grant K L, Schendel P F, McCoy J M. A thioredoxin gene fusion expression system that circumvents inclusion body formation in the E. coli cytoplasm. Bio/Technology. 1993;11:187–193. doi: 10.1038/nbt0293-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunn C A, Pigiet V P. Localization of thioredoxin from Escherichia coli in an osmotically sensitive compartment. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:11424–11430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lunn C A, Pigiet V P. Chemical cross-linking of thioredoxin to hybrid membrane fraction in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:832–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lurquin P F. Gene transfer by electroporation. Mol Biotechnol. 1997;7:5–35. doi: 10.1007/BF02821542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nossal N G, Heppel L A. The release of enzymes by osmotic shock from Escherichia coli in exponential phase. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3055–3062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sawers G, Watson G. A glycyl radical solution: oxygen-dependent interconversion of pyruvate formate-lyase. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:945–954. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schleyer M, Schmid R, Bakker E P. Transient, specific and extremely rapid release of osmolytes from growing cells of Escherichia coli K-12 exposed to hypoosmotic shock. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:424–431. doi: 10.1007/BF00245302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thorstenson Y R, Zhang Y, Olson P S, Mascarenhas D. Leaderless polypeptides efficiently extracted from whole cells by osmotic shock. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5333–5339. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5333-5339.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zimmermann U. Electrical breakdown, electropermeabilization and electrofusion. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1986;105:176–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]