Abstract

Background

This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of en bloc resection for patients with nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and explore whether a reresection can be avoided after initial en bloc resection.

Material and methods

We conducted research in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science up to October 12, 2021, to identify studies on the second resection after initial en bloc resection of bladder tumor (ERBT). R software and the double arcsine method were used for data conversion and combined calculation of the incidence rate.

Results

A total of 8 studies involving 414 participants were included. The rate of detrusor muscle in the ERBT specimens was 100% (95%CI: 100%–100%), the rate of tumor residual in reresection specimens was 3.2% (95%CI: 1.4%–5.5%), and the rate of tumor upstaging was 0.3% (95%CI: 0%–1.5%). Two articles compared the prognostic data of the reresection and non-reresection groups after the initial ERBT. We found no significant difference in the 1-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate (OR = 1.44, 95%CI: 0.67–3.09, P = 0.35) between the two groups nor in the rate of tumor recurrence (OR = 0.72, 95%CI: 0.44–1.18, P = 0.2) or progression (OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.33–2.89, P = 0.97) at the final follow-up.

Conclusions

ERBT can almost completely remove the detrusor muscle of the tumor bed with a very low postoperative tumor residue and upstaging rate. For high-risk NMIBC patients, an attempt to appropriately reduce the use of reresection after ERBT seems to be possible.

Keywords: high-risk, nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer, en bloc resection, reresection, systematic review and meta-analysis

Introduction

At present, transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) combined with postoperative intravesical instillation is the gold standard for the treatment of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) (1). However, due to piecemeal resection, traditional TURBT has a high tumor residual rate, making it difficult to provide accurate pathological staging (2, 3). For accurate staging and detection of tumor residue, reresection is recommended for patients with high-risk NMIBC, although it significantly increases the complication risk and financial stress (1, 4).

Different from traditional TURBT, as a new strategy, transurethral en bloc resection of bladder tumor (ERBT) can theoretically wholly remove the bladder tumor and even achieve a 100% detrusor muscle (DM) presence rate. Several recent studies also confirmed that detrusor muscle was present in above 95% of ERBT specimens (5–9). Some previous studies showed that the presence rate of DM was closely related to recurrence and could be a surrogate marker of resection quality (10–12). Although the latest study by Mastroianni et al. showed that the absence of DM has no impact on tumor recurrence, the high DM presence rate and tumor tissue integrity could provide a significant advantage in tumor staging (13, 14). Xu et al. performed reresection on high-risk NMIBC patients who underwent initial ERBT. The results showed that the residual tumor rate and tumor progression rate were only 5.9% and 3.9%, respectively. Moreover, they found that reresection did not seem to improve the prognosis of these patients (5). Given the advantages of ERBT, is it possible to reduce the need for a reresection in high-risk NMIBC patients after initial ERBT?

To answer this question, we conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of ERBT in treating NMIBC by integrating DM presence rate in primary ERBT specimens and tumor residual and upstaging rate in reresection specimens. In addition, we also compared the prognostic indicators of the reresection and non-reresection groups to assess whether patients would benefit from reresection. We believe that if the efficacy of ERBT is satisfactory and the patient cannot derive sufficient benefit from reresection, an attempt can be made to avoid reresection appropriately.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted research in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science up to October 12, 2021, to identify studies on reresection after initial ERBT. The search terms used include: (“bladder neoplasm” OR “bladder cancer” OR “bladder tumor” OR “carcinoma of bladder”) and (“en bloc” OR “en-bloc” OR “en-bloc”) and (“second” OR “repeat” OR “reresection” OR “restaging” OR “reTUR”). We also scanned references of key articles and searched the grey literature to ensure we did not miss any relevant articles. We reported the study according to the preferred reporting items of the systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) (15).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria are as follows: (P) patients diagnosed with primary high-grade Ta (TaHG) or T1 NMIBC who have received initial ERBT; (I) reresection performed within 12 weeks after initial ERBT; (C) no reresection after initial ERBT; (O) outcome indicators should include at least one of the following: detrusor muscle presence rate in primary ERBT specimens, tumor residual rate in reresection specimens, tumor upstaging rate in reresection specimens, comparison of prognostic data between reresection and non-reresection groups; and (S) observational study (prospective or retrospective).

Exclusion criteria are as follows: (a) case reports, comments, conference abstracts, and republished literature; (b) no interest outcome; and (c) data incomplete or invalid.

Selection process and data abstraction

The authors first read the titles and abstracts to conduct a preliminary literature screening. Documents that meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria will be directly included in the full-text evaluation. During the full-text evaluation phase, disputes were settled by two authors through consultation. If no agreement can be reached, a third author was consulted.

Two authors independently extracted data using a predesigned data extraction table. Baseline data included the following: first author and publication year, country, study type, ERBT method, reresection cases, and reresection time. Clinicopathological data included the following: the stage and grade of the primary tumor, primary tumor size, number of primary tumors, location of the residual tumor, follow-up, and prognosis. Data required for meta-analysis included the following: detrusor muscle presence rate in primary ERBT specimens, tumor residual rate in reresection specimens, tumor upstaging rate in reresection specimens, and comparison of prognostic data between reresection and non-reresection groups.

Literature quality and risk of bias assessment

We assessed the quality of literature using a Methodological index for nonrandomized studies (MINORS). The first eight items of MINORS were specially used for quality assessment of noncomparative studies, with 16 points. A score greater than or equal to 12 points was considered moderate to high literature quality (16).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses in this study were performed using R software and Cochrane Review Manager 5.3 (China). The significance level was P < 0.05. In a meta-analysis of prevalence, if the event incidence was greater than 0.8 or less than 0.2, the double arcsine method will be used (17). Inconsistencies (I2) statistics were used to assess heterogeneity. I2 > 50% indicates that the heterogeneity is very significant, and the random-effect model should be adopted. I2 < 50% indicates that the heterogeneity is acceptable, and the fixed-effect model should be adopted. If heterogeneity was significant, sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis will be used to explore the source of heterogeneity. Egger's test was used to evaluate publication bias quantitatively. P > 0.05 indicated no significant publication bias.

Results

Basic characteristics and quality assessment

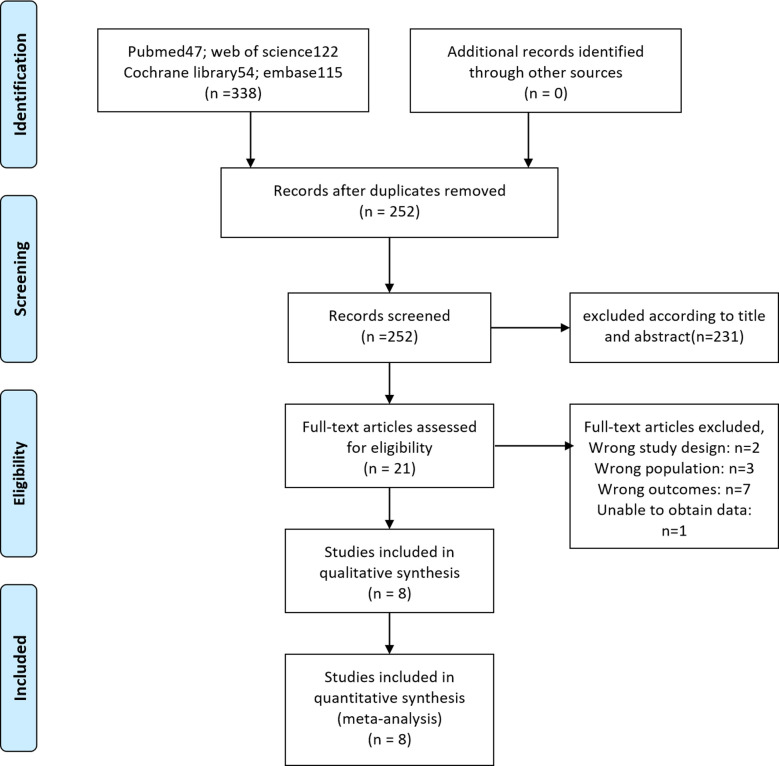

A PRISMA flow diagram visually illustrated the screening process (Figure 1). At last, eight studies (5–9, 18–20), including 414 participants, were included by carefully screening 252 articles. Among them, five (7, 8, 18–20) were prospective and three (5, 6, 9) were retrospective. In addition, five studies (5, 6, 18–20) were laser-based ERBT, two (7, 8) were based on electrotomy, and one (9) was based on laser or electrotomy (Table 1). The clinicopathological features of patients with reresection are presented in Table 2. The MINORS scale showed that all included studies had scores greater than or equal to 12 points, and the quality of the literature was satisfactory (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Literature search and selection.

Table 1.

Literature basic information and literature quality evaluation results.

| Study | Country | Study type | ERBT method | Reresection cases | Reresection time | Outcomes | Quality scores |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolters 2011 | Germany | PS | Thulium laser | 5 | 6 weeks | ABC | 12/16 |

| Muto 2014 | Italy | PS | Thulium laser | 49 | 30–90 days | ABC | 13/16 |

| Migliari 2015 | Italy | PS | Thulium laser | 53 | 90 days | ABC | 14/16 |

| Hurle 2020 | Italy | RS | Thulium laser/Electrotomy | 78 | 40 days | ABC | 13/16 |

| Soria 2020 | Italy | PS | Electrotomy | 42 | 2–6 weeks | ABC | 14/16 |

| Yang 2020 | China | PS | Electrotomy | 28 | 2–6 weeks | ABC | 14/16 |

| Zhou 2020 | China | RS | Thulium laser | 108 | 2–6 weeks | ABCD | 14/16 |

| Xu 2021 | China | RS | RevoLix 2-µm laser | 51 | 2–6 weeks | ABCD | 13/16 |

PS, prospective study; RS, retrospective study; A, detrusor muscle presence rate in ERBT specimens; B, tumor residual rate in reresection specimens; C, tumor upstaging rate in reresection specimens; D, comparison of prognostic data between reresection and non-reresection groups.

Table 2.

Clinicopathological features of patients with reresection.

| Study | Initial resection results |

Reresection results | Follow-up and prognosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T state and grade | Tumor diameter (cm) | Single lesion | Location of the residual tumor | ||

| Wolters 2011 | TaG1:1 (20%); TaG2:1 (20%); T1G3:3 (60%) | <3 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 0 | NA |

| Muto 2014 | TaLG:31 (63.3%); T1HG:18 (36.7%) | 2.36 ± 1.47 | Mixed | In situ:1 | 16 mon (RFS = 41/48, 85.4%; PFS = 100%); |

| 18mon (RFS = Ta:90%, T1:76%) | |||||

| Migliari 2015 | TaLG:30 (56.6%); T1HG:23 (43.4%) | 2.5 (0.5–4.5) | 53 (100%) | 0 | 20mon (RFS = 46/58, 79.3%; PFS = 100%) |

| 18mon (RFS = Ta:90%; T1:76%) | |||||

| Hurle 2020 | Ta:17 (21.8%); T1:57 (73.1%); Tis:4 (5.1%); G3:72 (92.3%) | 1.9 (1–3.5) | Mixed | In situ:1; Ectopic:4 | 30.8mon (RFS = 67/78, 85.9%; PFS = 77/78, 98.7%) |

| 3mon (RFS = 75/78, 96.2%) | |||||

| Soria 2020 | Ta:27 (64.3%); T1:8 (19.0%); Tis:7 (16.7%) | 2 (1–3) | 21 (50%) | In situ:1; Ectopic:1 | NA |

| Yang 2020 | HG or T1 | 2 (1–3) | Mixed | In situ:2 | NA |

| Zhou 2020 | Ta:60 (55.6%); T1:48 (44.4%); | 2.74 ± 0.13 | 56 (51.9%) | NA | 41.5mon (RFS = 85/108, 78.7%; PFS = 104/108, 96.3%) |

| LG:25 (23.2%); HG:83 (76.8%) | 12mon (RFS = 92.6%; PFS = 98.1%); | ||||

| 36mon (RFS = 84.3%; PFS = 96.3%) | |||||

| Xu 2021 | Ta:16 (31.4%); T1:35 (68.6%) | <3 cm (42.9%) | 22 (46.8%) | NA | 27mon (RFS = 41/51, 80.4%; PFS = 49/51, 96.1) |

| LG:13 (25.5%); HG:38 (74.5%) | ≥3 cm (46.7%) | 12mon (RFS = 94.1%) | |||

LG, low grade; HG, high grade; RFS, recurrence-free survival; PFS, progression-free survival; NA, not available.

Table 3.

MINORS assessment of included studies.

| Study | MINORS criteria |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clearly stated aim | Inclusion of consecutive patients | Prospective collection of data | Endpoints appropriate to the aims of the study | Unbiased assessment of the study endpoint | Follow-up period appropriate to the aim of the study | Loss to follow-up less than 5% | Prospective calculation of the study size | Total | |

| Wolters 2011 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 12 |

| Muto 2014 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| Migliari 2015 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Hurle 2020 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

| Soria 2020 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 14 |

| Yang 2020 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Zhou 2020 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Xu 2021 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 13 |

Meta-analysis results

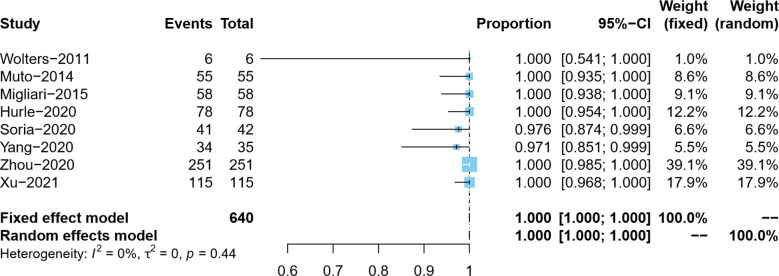

Detrusor muscle presence rate in primary ERBT specimens

Overall, the DM presence rate was reported by eight studies (5–9, 18–20). In the process of tumor resection, Yang et al. distinguished the clinical stage of bladder tumor in real-time and did not resect the detrusor muscle of the Ta tumor, so the actual DM presence rate was 97.1% (34/35) (7). Since the present rate of DM in ERBT specimens in the included studies was as high as 97.1%–100%, we adopted the double arcsine method for data conversion and, at the same time, corrected the data with the present rate of DM of 100%. Due to no pronounced heterogeneity observed (I2 = 0%), the meta-analysis results using the fixed effects model showed that the pooled DM presence rate in the ERBT specimens and its 95% confidence interval was 100% (95%CI: 100%–100%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot – detrusor muscle presence rate.

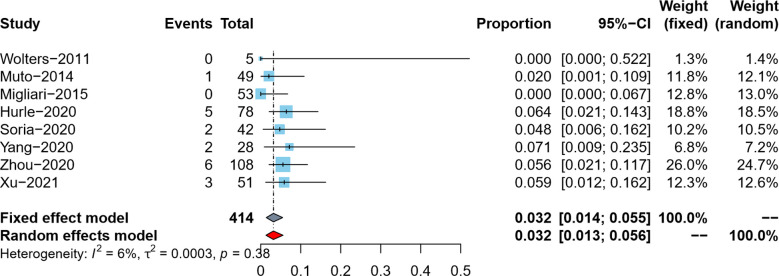

Tumor residual rate in reresection specimens

Tumor residual rate was reported by eight studies (5–9, 18–20). Since the tumor residual rates in the included studies were all lower than 10%, we used the double arcsine method for data conversion, and at the same time, we corrected the data with a tumor residual rate of 0. Due to no pronounced heterogeneity observed (I2 = 6%), the meta-analysis results using the fixed effects model showed that the pooled tumor residual rate in reresection specimens and its 95% confidence interval was 3.2% (95%CI: 1.4%–5.5%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot – tumor residual rate.

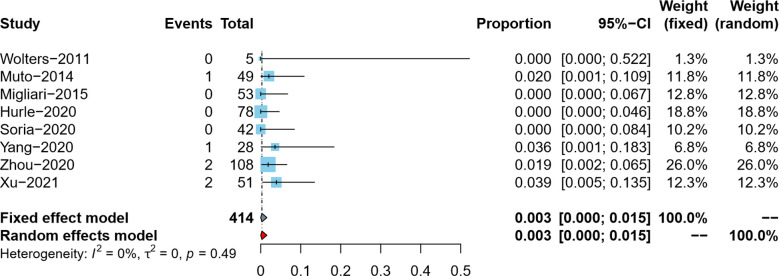

Tumor upstaging rate in reresection specimens

The tumor upstaging rate was reported by eight studies (5–9, 18–20). After data conversion and correction using the double arcsine method, the meta-analysis results using the fixed effects model showed that the pooled tumor upstaging rate in reresection specimens and its 95% confidence interval was 0.3% (95%CI: 0%–1.5%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot – tumor upstaging rate.

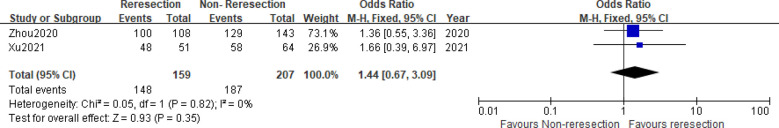

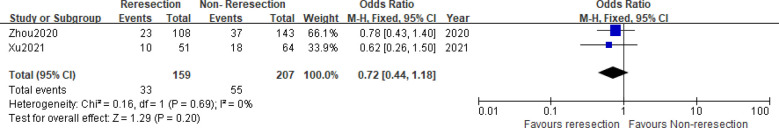

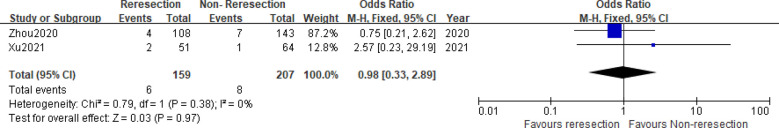

Comparison of prognostic data between reresection and non-reresection groups

Two studies (5, 6) compared the prognostic data of the reresection and non-reresection groups after the initial ERBT (Table 4). We found no significant difference in the 1-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate (OR = 1.44, 95%CI: 0.67–3.09, P = 0.35, I2 = 0%) (Figure 5) between the two groups nor in the rate of tumor recurrence (OR = 0.72, 95%CI: 0.44–1.18, P = 0.2, I2 = 0%) (Figure 6) or progression (OR = 0.98, 95%CI: 0.33–2.89, P = 0.97, I2 = 0%) (Figure 7) at final follow-up.

Table 4.

Prognosis of patients with high-risk NMIBC after initial ERBT (reresection vs. non-reresection).

| Study | Groups | Initial resection result |

follow-up (months) | 1-year recurrence-free rate | P | Tumor recurrence | P | Tumor progression | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T stage | Grade | |||||||||

| Xu 2021 | Reresection (n = 51) | Ta:16 (31.4%) | LG:13 (25.5%) | 27 (5–60) | 48/51 (94.1%) | 0.269 | 10/51 (19.6%) | >0.05 | 2/51 (3.9%) | 0.430 |

| T1:35 (68.6%) | HG:38 (74.5%) | |||||||||

| Non-reresection (n = 64) | Ta:15 (23.4%) | LG:13 (25.5%) | 58/64 (90.6%) | 18/64 (28.1%) | 1/64 (1.6%) | |||||

| T1:49 (76.6%) | HG:38 (74.5%) | |||||||||

| Zhou 2020 | Reresection (n = 108) | Ta:60 (55.6%) | LG:25 (23.2%) | 40 (3–72) | 100/108 (92.6%) | >0.05 | 23/108 (21.3%) | >0.05 | 4/108 (3.8%) | >0.05 |

| T1:48 (44.4%) | HG:83 (76.8%) | |||||||||

| Non-reresection (n = 143) | Ta:87 (60.8%) | LG:49 (34.3%) | 129/143 (90.2%) | 37/143 (27.3%) | 7/143 (4.0%) | |||||

| T1:56 (39.2%) | HG:94 (65.7%) | |||||||||

LG, low grade; HG, high grade.

Figure 5.

Forest plot – comparison of the 1-year recurrence-free survival rate between reresection and non-reresection groups.

Figure 6.

Forest plot – comparison of the tumor recurrence rate between reresection and non-reresection groups.

Figure 7.

Forest plot – comparison of the tumor progression rate between reresection and non-reresection groups.

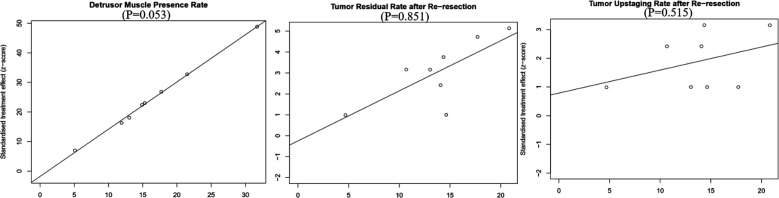

Publication bias

We used Egger's test to evaluate publication bias quantitatively, and the results showed that no obvious publication bias was found in all outcome index groups. We showed Egger plots and P values for the primary outcome indicators in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Publication bias – Egger’s graph.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first meta-analysis to explore whether a reresection can be avoided for high-risk NMIBC patients after initial ERBT. For high-risk NMIBC patients who underwent traditional TURBT, the primary purposes of reresection are to improve the present rate of DM, clarify tumor stage, reduce tumor residue, and improve the prognosis of patients (21, 22). However, our study showed that the present rate of DM in primary ERBT specimens could reach 100%. On this basis, the tumor upstaging rate and tumor residual rate in reresection specimens were extremely low. A recent meta-analysis involving 29 studies also showed that ERBT had a significantly higher DM presence rate in primary ERBT specimens and a significantly lower tumor residual rate in reresection specimens than traditional TURBT. It is consistent with our study (23). In addition, our study also found that reresection did not seem to improve the prognosis of high-risk NMIBC patients with initial ERBT. It can be seen that the advantages of ERBT over traditional TURBT seem to have satisfied the original intention of carrying out reresection. Reresection after initial ERBT in high-risk NMIBC patients does not appear to be critical and essential. Considering the trauma and economic pressure brought by reresection, for patients with poor physical conditions who are difficult to tolerate reresection, it seems that an attempt can be made to avoid reresection appropriately.

When there is no DM in the initial specimen, reresection can provide detrusor muscle of the tumor bed, thus improving the accuracy of tumor staging (24). Gordon's study showed that the present rate of DM in traditional TURBT specimens was 71.2%, which increased to 87.8% after reresection (25). Han et al.'s study showed that the tumor upstaging rate was 16.1% after referring to the reresection specimens (26). A recent systematic review also showed that tumor upstaging occurred in 0%–32% (T1 to ≥T2) of cases (24). In a single-center retrospective study by Zhou et al., DM was present in all 251 ERBT participants’ specimens, and the tumor upstaging rate was only 1.9% (2/108) after reresection of 108 high-risk NMIBC patients (6). Subsequently, Xu et al. also obtained similar results in the study of 115 patients, with the DM presence rate in primary ERBT specimens and the tumor upstaging rate in reresection specimens of 100% and 3.9%, respectively (5). Our study, which integrated all available data, showed that DM was present in 100% of ERBT specimens and the tumor upstaging rate was 0.3% after referring to the reresection specimens. Regarding tumor staging, ERBT has a high presence rate of DM and excellent staging accuracy. Therefore, reresection does not seem to be indispensable in terms of tumor staging.

Cumberbatch et al. conducted a systematic review of studies on reresection after traditional TURT. For Ta tumors, the rate of residual tumors found at reresection ranged from 17% to 67%, and for T1, it ranged from 20% to 71% (24). Subsequently, the study of Akitake et al. also showed that among 143 high-risk NMIBC patients with traditional TURBT, 66 tumor residues (46.2%) were found after reresection (27). Unlike the high tumor residual rate of traditional TURBT, our study showed that patients with initial ERBT found an extremely low tumor residual rate (3.2%) at reresection. In addition, Zhou et al. and Xu et al. performed cystoscopy on patients in the non-reresection group three months after ERBT. They found that the tumor residual rate was similar to that in the reresection group (5, 6). They believe that although the cystoscopy timing differed between groups, the results may have been biased. Nevertheless, in part, it might reflect that reresection after the initial ERBT did not seem to reveal more tumor residuals than non-reresection. In summary, the tumor residual rate of ERBT is low, and reresection may not find more residual tumors. It provides a basis for avoiding reresection.

In a prospective study, patients with T1 NMIBC at initial diagnosis were randomly divided into reresection and non-reresection groups. The first- and third-year recurrence-free survival rates were 82% and 65% in the reresection group and 57% and 37% in the non-reresection group, respectively. It indicates that the reresection can significantly improve the recurrence-free survival rates of patients (28). However, the study of Calo et al. showed that if the initial resection was complete, reresection did not improve RFS and progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with high-grade T1 NMIBC (29). The study of Gontero et al. also pointed out that if the detrusor muscle was not present in the initial TURBT specimen, the RFS and PFS of T1HG patients could be improved by reresection. If the detrusor muscle was present, the patient's prognosis could not be improved by reresection (30). We believe that the mechanism of reresection to improve prognosis lies in removing the DM in the tumor bed and removing the residual tumor as much as possible. In contrast, in ERBT patients who have almost achieved R0 resection, the effect of reresection to improve prognosis will no longer be indispensable. Our results confirm this hypothesis. We found no significant difference in the 1-year RFS rate between the reresection and non-reresection group, nor in the tumor recurrence rate or progression at final follow-up. Due to a lack of data, we included only two studies, which, despite possible bias, have demonstrated to some extent that high-risk NMIBC patients with initial ERBT do not seem to obtain significant improvement in prognosis from reresection.

Limitations

Admittedly, there are still flaws in our research. First, this study is a meta-analysis of the rate and lacks a control group, which cannot directly reflect the difference between ERBT and traditional TURBT. Second, only two studies compared the prognosis of the reresection and non-reresection groups, which is theoretically not suitable for meta-analysis. Third, due to the lack of primary data, we could not detail how many CIS, BCG nonresponse, multifocal, and 3 cm HG bladder tumors were reported in selected studies. Again, because of insufficient data, our study was not limited to T1 cases or included in subgroup analyses. Fourth, we did not consider the possibility of acquiring diabetes in sections far from the deepest part of the tumor, which may have skewed the results. Finally, despite the meta-analysis, the total sample size is still insufficient, and more large-sample randomized controlled studies are needed in the future to verify our results further.

Conclusion

ERBT can almost completely remove the detrusor muscle of the tumor bed with very low postoperative tumor residue and upstaging rate. Reresection after initial ERBT in high-risk NMIBC patients does not appear to be critical and essential. For patients with poor physical conditions who are difficult to tolerate reresection, it seems that an attempt can be made to appropriately avoid reresection.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

Conception and design: HY. Administrative support: HY. Provision of study materials or patients: JX, ZX. Collection and assembly of data: JX, ZX. Data analysis and interpretation: JX, ZX. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Babjuk M, Burger M, Capoun O, Cohen D, Comperat EM, Dominguez Escrig JL, et al. European association of urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (Ta, T1, and Carcinoma in Situ). Eur Urol. (2022) 81(1):75–94. 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vianello A, Costantini E, Del Zingaro M, Bini V, Herr HW, Porena M. Repeated white light transurethral resection of the bladder in nonmuscle-invasive urothelial bladder cancers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endourol. (2011) 25:1703–12. 10.1089/end.2011.0081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazica DA, Roth S, Brandt AS, Bottcher S, Mathers MJ, Ubrig B. Second transurethral resection after Ta high-grade bladder tumor: a 4.5-year period at a single university center. Urol Int. (2014) 92:131–5. 10.1159/000353089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svatek RS, Hollenbeck BK, Holmang S, Lee R, Kim SP, Stenzl A, et al. The economics of bladder cancer: costs and considerations of caring for this disease. Eur Urol. (2014) 66:253–62. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu S, Cao P, Wang K, Wu T, Hu X, Chen H, et al. Clinical outcomes of reresection in patients with high-risk nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer treated with en bloc transurethral resection: a retrospective study with a 1-year follow-up. J Endourol. (2021) 35(12):1801–7. 10.1089/end.2021.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou W, Wang W, Wu W, Yan T, Du G, Liu H. Can a second resection be avoided after initial thulium laser endoscopic en bloc resection for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer? A retrospective single-center study of 251 patients. BMC Urol. (2020) 20:30. 10.1186/s12894-020-00599-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang YJ, Liu C, Yang XF, Wang DW. Transurethral en bloc resection with monopolar current for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer based on TNM system. Transl Cancer Res. (2020) 9:2210–9. 10.21037/tcr.2020.03.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soria F, D'Andrea D, Moschini M, Giordano A, Mazzoli S, Pizzuto G, et al. Predictive factors of the absence of residual disease at repeated transurethral resection of the bladder. Is there a possibility to avoid it in well-selected patients? Urol Oncol. (2020) 38:77.e1–.e7. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2019.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hurle R, Casale P, Lazzeri M, Paciotti M, Saita A, Colombo P, et al. En bloc re-resection of high-risk NMIBC after en bloc resection: results of a multicenter observational study. World J Urol. (2020) 38:703–8. 10.1007/s00345-019-02805-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mariappan P, Zachou A, Grigor KM, Edinburgh Uro-Oncology G. Detrusor muscle in the first, apparently complete transurethral resection of bladder tumour specimen is a surrogate marker of resection quality, predicts risk of early recurrence, and is dependent on operator experience. Eur Urol. (2010) 57:843–9. 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.05.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gontero P, Sylvester R, Pisano F, Joniau S, Vander Eeckt K, Serretta V, et al. Prognostic factors and risk groups in T1G3 non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients initially treated with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin: results of a retrospective multicenter study of 2451 patients. Eur Urol. (2015) 67:74–82. 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.06.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yeo L, Jain S. Good quality white-light transurethral resection of bladder tumours (GQ-WLTURBT) with experienced surgeons performing complete resections and obtaining detrusor muscle reduces early recurrence in new non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: validation across time and place and recommendation for benchmarking. BJU Int. (2012) 109:E27.; author reply E-8. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11011_3.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer MW, Altieri V, Hurle R, Lusuardi L, Merseburger AS, Rassweiler J, et al. Current evidence of transurethral en-bloc resection of nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Eur Urol Focus. (2017) 3:567–76. 10.1016/j.euf.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mastroianni R, Brassetti A, Krajewski W, Zdrojowy R, Salhi YA, Anceschi U, et al. Assessing the impact of the absence of detrusor muscle in Ta low-grade urothelial carcinoma of the bladder on recurrence-free survival. Eur Urol Focus. (2021) 7(6):1324–31. 10.1016/j.euf.2020.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. (2003) 73:712–6. 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barendregt JJ, Doi SA, Lee YY, Norman RE, Vos T. Meta-analysis of prevalence. J Epidemiol Community Health. (2013) 67:974–8. 10.1136/jech-2013-203104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Migliari R, Buffardi A, Ghabin H. Thulium Laser endoscopic en bloc enucleation of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer. J Endourol. (2015) 29:1258–62. 10.1089/end.2015.0336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muto G, Collura D, Giacobbe A, D'Urso L, Muto GL, Demarchi A, et al. Thulium:yttrium–aluminum–garnet laser for en bloc resection of bladder cancer: clinical and histopathologic advantages. Urology. (2014) 83:851–5. 10.1016/j.urology.2013.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolters M, Kramer MW, Becker JU, Christgen M, Nagele U, Imkamp F, et al. Tm:YAG laser en bloc mucosectomy for accurate staging of primary bladder cancer: early experience. World J Urol. (2011) 29:429–32. 10.1007/s00345-011-0686-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamiya N, Suzuki H, Suyama T, Kobayashi M, Fukasawa S, Sekita N, et al. Clinical outcomes of second transurethral resection in nonmuscle invasive high-grade bladder cancer: a retrospective, multi-institutional, collaborative study. Int J Clin Oncol. (2017) 22:353–8. 10.1007/s10147-016-1048-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eroglu A, Ekin RG, Koc G, Divrik RT. The prognostic value of routine second transurethral resection in patients with newly diagnosed stage pT1 non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results from randomized 10-year extension trial. Int J Clin Oncol. (2020) 25:698–704. 10.1007/s10147-019-01581-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanagisawa T, Mori K, Motlagh RS, Kawada T, Mostafaei H, Quhal F, et al. En bloc resection for bladder tumors: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of its differential effect on safety, recurrence and histopathology. J Urol. (2022) 207:754–68. 10.1097/JU.0000000000002444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cumberbatch MGK, Foerster B, Catto JWF, Kamat AM, Kassouf W, Jubber I, et al. Repeat transurethral resection in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review. Eur Urol. (2018) 73:925–33. 10.1016/j.eururo.2018.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon PC, Thomas F, Noon AP, Rosario DJ, Catto JWF. Long-term outcomes from re-resection for high-risk non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a potential to rationalize use. Eur Urol Focus. (2019) 5:650–7. 10.1016/j.euf.2017.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han KS, Joung JY, Cho KS, Seo HK, Chung J, Park WS, et al. Results of repeated transurethral resection for a second opinion in patients referred for nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer: the referral cancer center experience and review of the literature. J Endourol. (2008) 22:2699–704. 10.1089/end.2008.0281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akitake M, Yamaguchi A, Shiota M, Imada K, Tatsugami K, Yokomizo A, et al. Predictive factors for residual cancer in second transurethral resection for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Anticancer Res. (2019) 39:4325–8. 10.21873/anticanres.13598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Divrik RT, Sahin AF, Yildirim U, Altok M, Zorlu F. Impact of routine second transurethral resection on the long-term outcome of patients with newly diagnosed pT1 urothelial carcinoma with respect to recurrence, progression rate, and disease-specific survival: a prospective randomised clinical trial. Eur Urol. (2010) 58:185–90. 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calo B, Chirico M, Fortunato F, Sanguedolce F, Carvalho-Dias E, Autorino R, et al. Is repeat transurethral resection always needed in high-grade T1 bladder cancer? Front Oncol. (2019) 9:465. 10.3389/fonc.2019.00465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gontero P, Sylvester R, Pisano F, Joniau S, Oderda M, Serretta V, et al. The impact of re-transurethral resection on clinical outcomes in a large multicentre cohort of patients with T1 high-grade/grade 3 bladder cancer treated with bacille Calmette-Guerin. BJU Int. (2016) 118:44–52. 10.1111/bju.13354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.