Abstract

Rice (Oryza sativa) is one of the most important crops worldwide. Heading date is a vital agronomic trait that influences rice yield and adaption to local conditions. Hd3a, a proposed florigen that primarily functions under short-day (SD) conditions, is a mobile flowering signal that promotes the floral transition in rice. Nonetheless, how Hd3a is transported from leaves to the shoot apical meristem (SAM) under SDs remains elusive. Here, we report that FT-INTERACTING PROTEIN9 (OsFTIP9) specifically regulates rice flowering time under SDs by facilitating Hd3a transport from companion cells (CCs) to sieve elements (SEs). Furthermore, we show that the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) protein OsTPR075 interacts with both OsFTIP9 and OsFTIP1 and strengthens their respective interactions with Hd3a and the florigen RICE FLOWERING LOCUS T1 (RFT1). This in turn affects the trafficking of Hd3a and RFT1 to the SAM, thus regulating flowering time under SDs and long-day conditions, respectively. Our findings suggest that florigen transport in rice is mediated by different OsFTIPs under different photoperiods and those interactions between OsTPR075 and OsFTIPs are essential for mediating florigen movement from leaves to the SAM.

The tetratricopeptide repeat protein OsTPR075 regulates heading in rice by associating with FT-interacting proteins OsFTIP9 and OsFTIP1 to facilitate florigen transport to the shoot apical meristem.

IN A NUTSHELL.

Background: Hd3a and RICE FLOWERING LOCUS T1 (RFT1) are mobile flowering signals that promote the floral transition in rice and were proposed to function as florigens that play major roles under short-day (SD) and long-day (LD) conditions, respectively. Hd3a and RFT1 are synthesized in leaves and transported to the shoot apex to trigger the transition to flowering. FT-INTERACTING PROTEIN1 (OsFTIP1) is the only protein reported to mediate RFT1 transport in rice under LDs. Hd3a plays major roles in promoting flowering under SDs.

Question: How is Hd3a transported from leaves to the shoot apex in SDs? What is the function of tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) proteins in regulating heading date in rice?

Findings: We found that OsFTIP9 specifically regulates rice heading date under SDs by facilitating the transport of Hd3a from companion cells to sieve elements. Furthermore, we show that OsTPR075 interacts with both OsFTIP9 and OsFTIP1, which strengthens their respective interactions with Hd3a and RFT1. This in turn affects Hd3a and RFT1 trafficking to the shoot apical meristem, thus regulating heading date under SDs and LDs, respectively.

Next steps: Given that OsFTIPs and OsTPRs are important for the functions of protein transport complexes, we are interested in identifying additional interactors of these proteins and the crystal structures of OsFTIPs and OsTPRs. Moreover, it would be worth exploring the potential relevance of the FTIP–TPR interaction for members of the FTIP and TPR families involved in regulating flowering time in other plants.

Introduction

The floral transition from the vegetative stage to the reproductive stage is one of the most crucial processes in the plant lifecycle (Srikanth and Schmid, 2011; Cho et al., 2017). Rice (Oryza sativa) is one of the most important crops in the world, and heading date (flowering time) is a vital agronomic trait that influences yield and regional adaptation (Jung and Müller, 2009). Rice is a facultative short-day (SD) plant that flowers earlier under SD conditions than under long-day (LD) conditions.

Flowering is precisely modulated by multiple flowering pathways in response to both endogenous developmental signals and external environmental cues in plants (Tsuji et al., 2013; Song et al., 2015; Cho et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2021). In Arabidopsis thaliana, the photoperiod pathway regulates flowering time mainly via the GIGANTEA–CONSTANS–FLOWERING LOCUS T (GI–CO–FT) module in which CO receives signals from GI and then affects the expression of FT (Mouradov et al., 2002; Fujiwara et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2021). The conserved OsGI-heading date 1 (Hd1)–Hd3a/RICE-FLOWERING LOCUS T1 (RFT1) pathway (analogous to the Arabidopsis GI–CO–FT pathway) could also regulate heading date in rice (Takahashi and Shimamoto, 2011). In addition, Ghd7-early heading date 1 (Ehd1)-RFT1 is a unique signaling pathway that regulates rice flowering (Doi et al., 2004; Xue et al., 2008). The conserved and unique signaling pathways have a critical interaction through the Ghd7–Hd1 module. The transcription factors Ghd7 and Hd1 interact and form a complex to affect the expression of a series of genes in flowering signaling pathways (Nemoto et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2021; Zong et al., 2021). Meanwhile, Ehd1 expression is affected by OsGI, Ehd2, CONSTANS-LIKE4 (OsCOL4), or Phytochrome B under LDs and/or SDs (Kim et al., 2007; Matsubara et al., 2008; Park et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2021). Several regulatory pathways are thought to converge to generate florigen, encoded by FT in Arabidopsis and Hd3a and RFT1 in rice. Florigen, a systemic signal synthesized in the phloem companion cells (CCs) of leaves, is transported to the shoot apical meristem (SAM) where it accumulates and promotes the floral transition. In Arabidopsis, FT interacts with FD and 14-3-3 proteins to activate floral meristem identity genes (such as AP1/LEAFY) to induce the floral transition (Corbesier et al., 2007; Jaeger and Wigge, 2007; Lin et al., 2007; Mathieu et al., 2007; Tamaki et al., 2007; Komiya et al., 2009; Song et al., 2015).

In Arabidopsis, two multiple C2 domain and transmembrane region proteins (MCTPs), FT-INTERACTING PROTEIN1 (FTIP1) and QUIRKY (QKY), mediate the trafficking of FT from CCs to sieve elements (SEs; Liu et al., 2012, 2019). The soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor protein attachment protein receptor SYNTAXIN OF PLANTS 121 (SYP121) interacts with QKY to regulate FT transport in a temperature-dependent manner with FTIP1 (Liu et al., 2019, 2020). In addition, SODIUM POTASSIUM ROOTDEFECTIVE 1 (NaKR1), a heavy metal-associated domain-containing protein, regulates the long-distance movement of FT from leaves to the SAM (Zhu et al., 2016). These findings provide insights into the long-distance trafficking of florigen in Arabidopsis. However, despite this progress, how florigen transport is mediated in other plants, such as rice, remains largely unknown.

Hd3a and RFT1 are mobile flowering signals that promote the floral transition in rice and are thought to be florigens that primarily function under SDs and LDs, respectively (Tamaki et al., 2007; Komiya et al., 2008, 2009). Hd3a and RFT1 are synthesized in leaves and transported to the shoot apex, where they separately form florigen activation complexes (FACs) with 14-3-3 protein and the transcription factor OsFD1 to activate the expression of floral identity genes (such as OsMADS14 and OsMADS15) to trigger the transition to flowering (Tamaki et al., 2007; Komiya et al., 2008; Taoka et al., 2011; Cai et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). A recent study showed that the calcineurin B-like-interacting protein kinase OsCIPK3 directly interacts with and phosphorylates OsFD1 to promote the formation of an RFT1-containing FAC, thereby inducing flowering under LDs (Peng et al., 2021). An OsCOL4 transcription factor encoded by Delayed Heading Date 4 competes with 14-3-3 to interact with OsFD1 and interferes with the formation of the Hd3a-14-3-3–OsFD1 complex, thus resulting in reduced expression of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15, ultimately regulating flowering (Cai et al., 2021). OsFTIP1 is the only protein reported to mediate RFT1 transport in rice under LDs (Song et al., 2017). Under SDs, Hd3a plays major roles in promoting flowering (Tamaki et al., 2007; Komiya et al., 2008, 2009). However, how Hd3a is transported from leaves to the shoot apex in SDs remains elusive.

In this study, we show that OsFTIP9, an OsFTIP1-like MCTP, plays an important role in regulating flowering time in rice under SDs by mediating Hd3a transport. We further show that the tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) protein OsTPR075 interacts with both OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9 and modulates flowering time in rice under both LDs and SDs. The TPR motif forms structural domains that act as interaction scaffolds to form multi-protein complexes involved in numerous cellular processes such as transcription, protein degradation, and protein transport (Goebl and Yanagida, 1991; Blatch and Lässle, 1999; D'Andrea and Regan, 2003; Wochnik et al., 2005; Allan and Ratajczak, 2011; Wei and Han, 2017). Our results reveal that OsTPR075 regulates the interaction intensity of OsFTIP9–Hd3a or OsFTIP1–RFT1 in leaves, which in turn affects Hd3a or RFT1 trafficking to the SAM, thus regulating flowering time in rice under both SDs and LDs. These findings provide a mechanistic understanding of florigen transport in rice under SDs and reveal a key role of OsTPR075 in mediating FTIP–florigen interactions required for florigen transport from leaves to the SAM.

Results

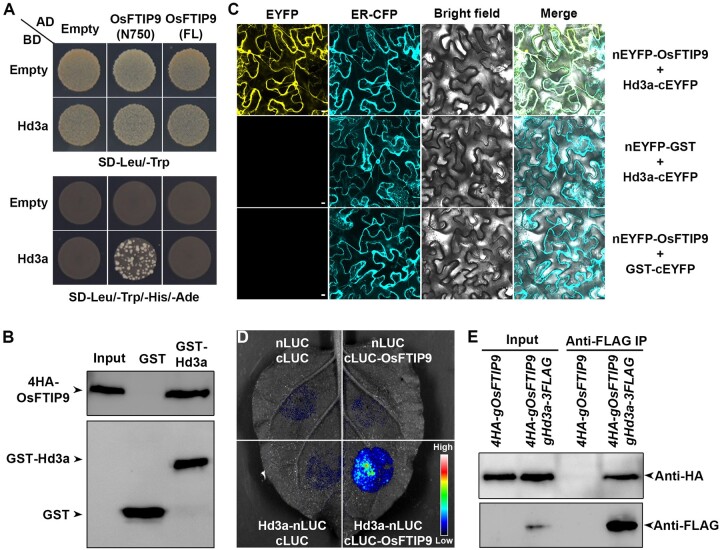

OsFTIP9 interacts with Hd3a

To elucidate the mechanism underlying Hd3a movement from leaves to the SAM, we carried out a yeast two-hybrid screening to isolate the putative interacting proteins of Hd3a using Hd3a as a bait (Supplemental Table S1). The identified proteins included OsFTIP9 (Os01g0587300), containing four C2 domains and two transmembrane regions (Supplemental Figure S1), another member of the FTIP family. FTIPs play essential roles in protein transport (Liu et al., 2012, 2018, 2019; Song et al., 2017, 2018). To validate the screening result, we utilized various approaches to test the interaction between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a. First, a yeast two-hybrid assay revealed the interaction between Hd3a and OsFTIP9 N750, a truncated protein devoid of the C-terminal transmembrane region, which might interfere with the binding of FTIPs with other proteins (Liu et al., 2012; Song et al., 2017, 2018), but not the full-length (FL) OsFTIP9 protein (Figure 1A). Moreover, we found that the second C2 domain is responsible for the interaction of OsFTIP9 with Hd3a (Supplemental Figure S2).

Figure 1.

OsFTIP9 interacts with Hd3a. A, Yeast two-hybrid assay of interactions between Hd3a and FL OsFTIP9 and its N terminus (amino acid 1–750; N750), including four C2 domains. Transformed yeast cells were grown on SD–Leu/–Trp and SD–Leu/–Trp/–His/–Ade medium. Empty refers to AD- or BD-containing vector only. B, In vitro GST pull-down assay of the interaction between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a. 4HA-OsFTIP9 generated from rice protoplasts was incubated with immobilized GST or GST-Hd3a. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-HA or anti-GST antibodies. Input, 5% of the 4HA–OsFTIP9 generated from rice protoplasts. C, BiFC analysis of the interaction between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a. GST was used as a negative control. Merge, merge of EYFP, ER-CFP, and bright field images. Scale bars, 10 μm. D, LCI assay of interactions between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a. The indicated fusion pairs were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. E, In vivo interaction between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a shown by CoIP in rice. Total protein extracts from leaves of 4HA-gOsFTIP9 and 4HA-gOsFTIP9 gHd3a-3FLAG plants at 35 DAS under SDs were immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG beads. The input and coimmunoprecipitated proteins were detected by anti-HA (upper) or anti-FLAG (lower) antibody.

Secondly, a glutathione S-transferase (GST) pull-down assay showed that 4HA-OsFTIP9 generated from rice protoplasts was precipitated by GST-Hd3a, but not by GST (Figure 1B), verifying the in vitro interaction between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a. Third, a bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay revealed the presence of the enhanced yellow fluorescence protein (EYFP) signal of nEYFP-OsFTIP9 and Hd3a-cEYFP in all regions of Nicotiana benthamiana epidermal cells except the nuclei, whereas no fluorescent signals were detected in the negative controls (Figure 1C). Fourth, a firefly luciferase complementation imaging (LCI) assay revealed strong luciferase signals when OsFTIP9 and Hd3a were both present (Figure 1D), suggesting the in vivo interaction of OsFTIP9 and Hd3a in plants. Finally, to verify the in vivo interaction between Hd3a and OsFTIP9 in rice, we crossed Osftip9-1 g4HA-OsFTIP9 (#16), in which the late flowering of Osftip9-1 was fully rescued under SDs (Supplemental Figure S3B), with hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG (#9) to obtain 4HA-gOsFTIP9 gHd3a-3FLAG. In a coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) assay, 4HA-OsFTIP9 was immunoprecipitated with Hd3a-3FLAG, demonstrating the physical interaction of Hd3a and OsFTIP9 in vivo (Figure 1E). These results collectively confirm the notion that OsFTIP9 interacts with Hd3a.

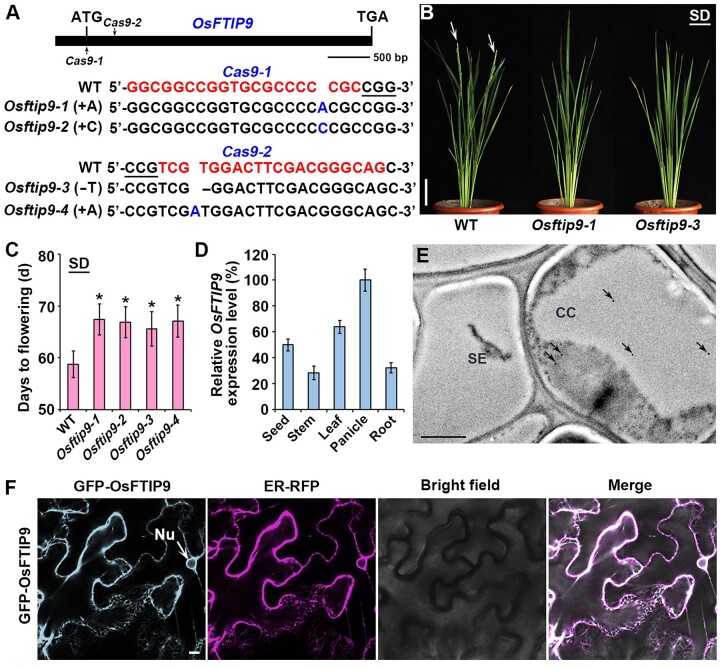

Loss function of OsFTIP9 delays flowering in rice under SDs

To investigate the biological role of OsFTIP9 in flowering regulation in rice, we generated Osftip9 mutants in the Nipponbare cultivar background by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated nuclease 9 (Cas9)-mediated target mutagenesis. Two different single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) were designed to target the coding region of OsFTIP9 (Figure 2A). More than 20 independent T0 lines were identified for each mutation occurring 3- to 4-bp upstream of the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which is the location of the Cas9 cleavage site. After sequencing the targeted genomic regions inT2 populations derived from T1 homozygotes, we selected four homozygous mutants that were negative for the CRISPR/Cas9 transgene: Osftip9-1, Osftip9-2, Osftip9-3, and Osftip9-4, which contained a 1-bp adenine (A) insertion, a 1-bp cytosine (C) insertion, a 1-bp thymine (T) deletion, and a 1-bp adenine (A) insertion, respectively (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Loss function of OsFTIP9 delays flowering in rice under SDs. A, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated target mutagenesis of OsFTIP9. The upper part shows a schematic diagram of the OsFTIP9 gene bearing the CRISPR/Cas9 target sites (indicated by arrows). Exons and introns are represented by black boxes and lines, respectively. Each alignment between wild-type and mutated sequences containing the target sites is shown below the schematic diagrams. The target sequences adjacent to the underlined PAMs are indicated in red in wild-type sequences. The newly generated Osftip9-1, Osftip9-2, Osftip9-3, and Osftip9-4 mutants include a 1-bp A insertion, a 1-bp C insertion, a 1-bp T deletion, and a 1-bp A insertion, respectively. B, Comparison of the phenotypes of wild-type, Osftip9-1 and Osftip9-3 plants grown under SDs. Arrows indicate panicles. The phenotypes were observed >6 times independently with similar results. Scale bar, 12 cm. C, Days to flowering of wild-type and Osftip9 plants. Error bars denote sd (n = 20). Asterisks indicate significant differences between wild-type and Osftip9 plants (Student’s t test, P < 0.001). D, RT-qPCR analysis of OsFTIP9 expression in various tissues of the wild-type. Error bars denote sd (n = 3). E, 4HA-OsFTIP9 localization by immunogold electron microscopy using anti-HA antibody in companion cell-sieve element complexes in the leaf vasculature of Osftip9-1 4HA-gOsFTIP9. Arrows indicate the locations of gold particles. CC, companion cell; SE, sieve element. Scale bar, 1 μm. F, Subcellular localization of GFP-OsFTIP9 in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. GFP, GFP fluorescence; ER-RFP, RFP fluorescence of an ER marker; Nu, nucleus; Arrow indicates the location of the nucleus. Merge, merge of GFP, RFP, and bright field. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Phenotypic observation revealed that all alleles of Osftip9 displayed late heading date compared to wild-type plants under SDs (Figure 2, B and C) but showed comparable flowering to the controls under LDs (Supplemental Figure S4), indicating that OsFTIP9 plays a specific role in regulating rice flowering under SDs. To confirm that the late-flowering phenotype of Osftip9 is caused by the abolishment of OsFTIP9 function, we transformed Osftip9-1 homozygous plants with the genomic construct gOsFTIP9 or 4HA-gOsFTIP9, harboring a 6.2-kb OsFTIP9 genomic region bearing the 3.0-kb 5′-upstream sequence and the entire 3.2-kb coding sequence (Supplemental Figure S3A). Homozygous transgenic plants were selected based on germination on hygromycin-containing medium, and at least 10 independent transformants containing a single-copy transgene based on a 3:1 Mendelian segregation ratio were obtained. Phenotypic examination of these transgenic lines revealed that the late-flowering phenotype of Osftip9-1 was rescued to different extents in these 10 lines, and most displayed comparable heading dates to wild-type plants (Supplemental Figure S3B), indicating that the late-heading phenotype of Osftip9 under SDs was attributed to the loss function of OsFTIP9.

Next, we examined the expression patterns of OsFTIP9 in various tissues of wild-type plants using real time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). OsFTIP9 was ubiquitously expressed in all tissues examined, with the highest expression in panicles and leaves (Figure 2D). We also performed immunoelectron microscopy using an Osftip9-1 4HA-gOsFTIP9 transgenic line (#16) to precisely localize OsFTIP9. Notably, 4HA-OsFTIP9 signals were only detected in phloem CCs, but not in SEs (Figure 2E). Additionally, we examined the subcellular localization of OsFTIP9 by transiently expressing 35S:GFP-OsFTIP9 with various fluorescent protein-tagged organelle markers (Nelson et al., 2007) in N. benthamiana leaf epidermal cells. GFP-OsFTIP9 was intensively colocalized with the red fluorescent protein (RFP)-tagged endoplasmic reticulum (ER) marker ER-RFP throughout the cells (Figure 2F).

OsFTIP9 mediates Hd3a movement from leaves to the SAM

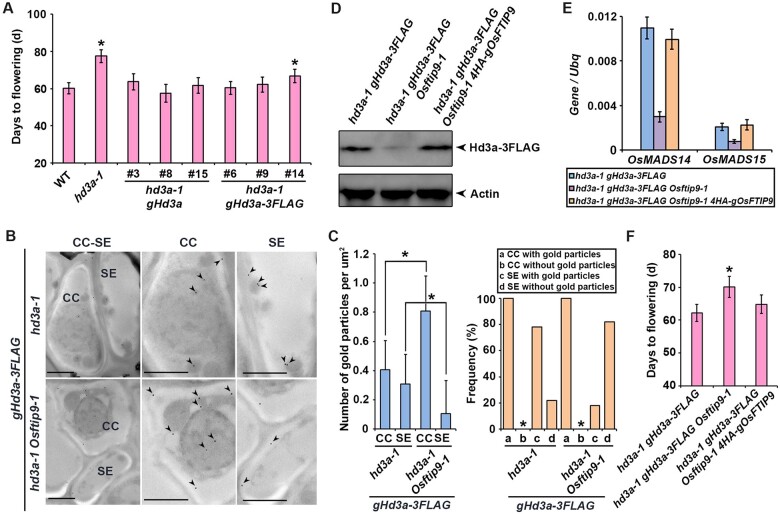

Given that OsFTIP9 and Hd3a interact with each other (Figure 1) and that both hd3a and Osftip9 exhibited late flowering under SD conditions (Figure 2, B and C), it is possible that OsFTIP9 modulates rice flowering by mediating Hd3a function. RT-qPCR revealed that Hd3a mRNA accumulation was not altered in Osftip9 (Supplemental Figure S5), suggesting that OsFTIP9 might affect the function of Hd3a at the posttranscriptional level. To clarify the biological significance of the interaction between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a and to quantify Hd3a protein, we transformed homozygous hd3a-1 calli with a genomic construct (gHd3a) harboring a 4.1-kb Hd3a genomic fragment including the 2.0-kb upstream sequence and the 2.1-kb coding sequence plus three introns with or without the 3FLAG tag (gHd3a or gHd3a-3FLAG). Homozygous transgenic plants were selected and at least eight independent transformants contained a single-copy transgene based on a 3:1 Mendelian segregation ratio were obtained. Phenotypic examination revealed that the late heading date of hd3a-1 was rescued to different extents in all homozygous progenies in the T2 generation (Figure 3A). The transgenic lines hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG #9, which showed similar flowering times to the wild-type (Figure 3A), were selected for further study.

Figure 3.

OsFTIP9 affects Hd3a transport. A, Days to flowering of selected hd3a-1 lines harboring gHd3a or gHd3a-3FLAG in the T2 generation. Asterisks indicate a significant difference between wild-type and hd3a-1 (Student’s t test, P < 0.001). Error bars denote sd (n = 20). B, Analysis of Hd3a-3FLAG distribution in CC–SE complexes in leaves of hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG and hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 plants at 35 DAS under SDs by immunogold electron microscopy using anti-FLAG antibody. CCs are characterized by dense protoplasts and well-developed nuclei, whereas SEs lose most of their cellular contents during maturation and retain few minor organelles. The left parts show representative CC–SE complexes. Higher magnification views of CCs or SEs are shown in the middle and right parts, respectively. Arrowheads indicate the locations of gold particles. Bars, 0.5 μm. C, Quantification of Hd3a-3FLAG immunogold signals in CCs and SEs of gHd3a-FLAG hd3a-1 (hd3a-1 background) or gHd3a-FLAG hd3a-1 Osftip9-1 (hd3a-1 Osftip9-1 background) is shown in the left part. Over 100 CC–SE complexes in 50 sections from five different plants per genotype were analyzed. The data are presented as the mean number of gold particles per micrometer square plus or minus sd. The asterisks represent significant differences between the indicated groups (P = 2.3E-28 and P = 1.5E-10, respectively). The right part shows a frequency histogram of the appearance of Hd3a-3FLAG immunogold signals in CCs and SEs in all examined sections of gHd3a-3FLAG or gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1. Asterisks indicate that the frequency of CCs without gold particles was zero in all sections examined. D, Immunoblot analysis using anti-FLAG antibody showing Hd3a-3FLAG abundance in shoot apices of gHd3a-3FLAG plants in various genetic backgrounds (hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG, hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1, and hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 gFTIP9) at 35 DAS under sds. Actin was used as a loading control. E, The expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in shoot apices of various genotypes at 40 DAS under SDs. Results were normalized against the expression levels of Ubiquitin (Ubq) based on three biological replicates. The expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG were set to 1. Error bars denote sd. F, Days to flowering of hd3a-1 gHd3a-FLAG plants in various genetic backgrounds under SDs (n = 20). Asterisk indicates significant difference between hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG and hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 (Student t test, P < 0.001). Error bars represent SD.

To validate how OsFTIP9 affects the role of Hd3a in regulating rice flowering, we crossed hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG #9 and Osftip9-1 4HA-OsFTIP9 #16 to various genotypes containing the biologically functional allele gHd3a-FLAG. Hd3a is synthesized in leaves and transported to the SAM through the phloem (Tamaki et al., 2007). The observation that OsFTIP9 only localized to phloem CCs (Figure 2E) and that OsFTIP1, the homolog of OsFTIP9, mediates the movement of RFT1 from leaves to the SAM under LDs (Song et al., 2017) suggest that the effect of OsFTIP9 on heading date under SD conditions might be caused by the modulation of Hd3a transport through the phloem. Hence, we utilized immunoelectron microscopy to test whether OsFTIP9 influences Hd3a export from CCs to SEs in gHd3a-3FLAG lines in both the hd3a-1 and hd3a-1 Osftip9-1 backgrounds (Figure 3B).

Hd3a-3FLAG signals were detected by anti-FLAG antibody in CCs in both the hd3a-1 and hd3a-1 Osftip9-1 backgrounds, albeit at different frequencies, whereas in SEs, the signals were greatly reduced in the hd3a-1 Osftip9-1 background (Figure 3B). Although all hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG and hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 sections exhibited Hd3a-3FLAG signals in CCs (Figure 3B), quantitative analysis revealed a significant increase in Hd3a-3FLAG signals in hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 versus hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG (Figure 3C). Meanwhile, Hd3a-3FLAG signals in SEs were much stronger in the hd3a-1 versus hd3a-1 Osftip9-1 background (Figure 3C, left). Moreover, Hd3a-3FLAG signals were found in 78% of hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG sieve element sections but only 18% of hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 sections (Figure 3C, right). Thus, loss function of OsFTIP9 affects Hd3a-3FLAG accumulation in CCs and its transport to SEs.

Consistent with the observations from immunoelectron microscopy, Hd3a-3FLAG levels were reduced in shoot apices but not in leaves of hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 compared to hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG plants. Moreover, introduction of OsFTIP9 into hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 restored Hd3a accumulation in the shoot apices (Figure 3D;Supplemental Figure S6). Additionally, the expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15, which are involved in floral meristem development and activated by Hd3a in the SAM (Komiya et al., 2008), exhibited similar patterns to Hd3a-3FLAG abundance in hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG, hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1, and hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Osftip9-1 4HA-OsFTIP9 (Figure 3E). Furthermore, the heading dates of gHd3a-3FLAG plants in various genetic backgrounds were closely related to Hd3a-3FLAG protein levels and the expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in the shoot apex (Figure 3F). Taken together, these results demonstrate that OsFTIP9 mediates Hd3a export from phloem CCs to SEs, thus affecting Hd3a abundance in the SAM.

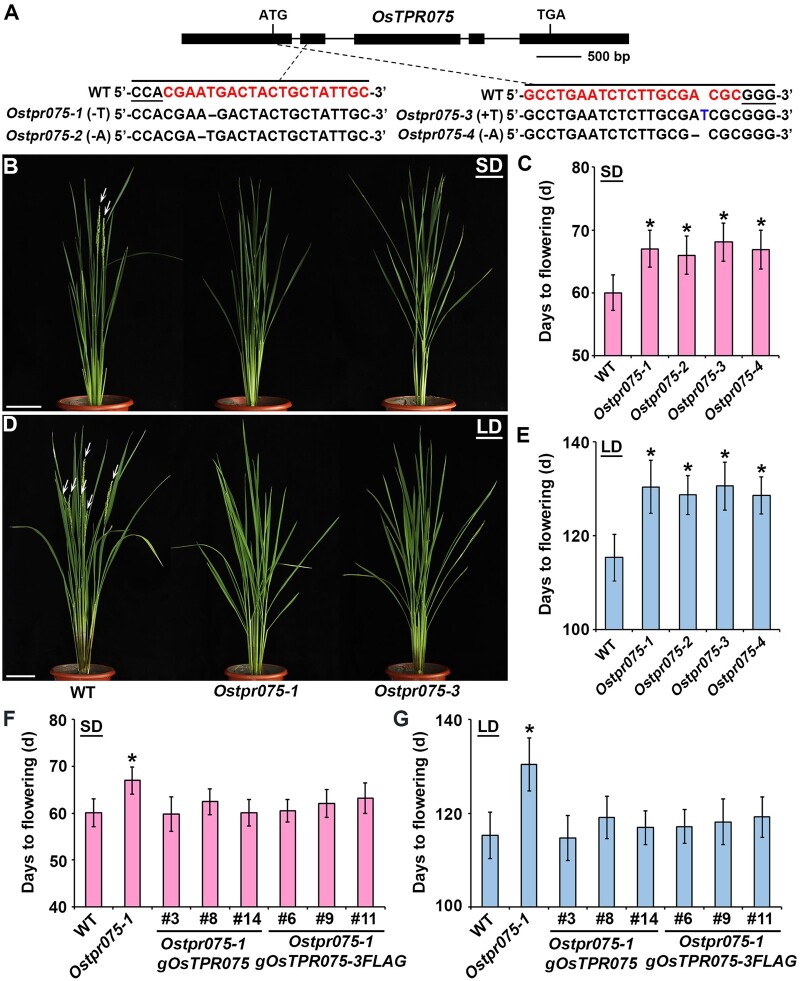

OsTPR075 promotes flowering in rice

To gain insights into the molecular mechanism of OsFTIP9–Hd3a-meditated flowering time in rice, we performed a CoIP assay followed by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) to identify components associated with 4HA-OsFTIP9 in an Osftip9-1 4HA-gOsFTIP9-tagged line (Supplemental Table S2). A TPR protein of unknown function, OsTPR075 (Os03g0200600), was isolated as a potential interacting partner of OsFTIP9 (Supplemental Figure S7). To explore the biological role of OsTPR075 in flowering regulation in rice, we generated Ostpr075 mutants by CRISPR–Cas9-mediated gene editing by designing two different sgRNAs (Figure 4A). Four homozygous mutants with different alterations in the absence of the CRISPR/Cas9 transgene were selected (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Ostpr075 delays heading date in rice under both SDs and LDs. A, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted mutagenesis of OsTPR075. Exons and introns are represented by black boxes and lines, respectively. Each alignment between wild-type and mutated sequences containing the target sites is shown below the schematic diagrams. The target sequences adjacent to the underlined PAMs are indicated in red in wild-type sequences. B, and D, Comparison of the phenotypes of wild-type, Ostpr075-1, and Ostpr075-3 plants grown under SDs (B) or LDs (D). Arrows indicate panicles. The phenotypes were observed >6 times independently with similar results. Scale bars, 12 cm. C, and E, Days to flowering of wild-type and Ostpr075 plants under SDs (C) or LDs (E). Error bars denote sd (n = 20). Asterisks indicate significant differences between wild-type and Ostpr075 plants (Student’s t test, P < 0.001). F, and G, Days to flowering of selected Ostpr075-1 lines harboring gOsTPR075 or gOsTPR075-3FLAG in the T2 generation under SDs (F) or LDs (G). Error bars denote sd (n = 20). Asterisks indicate significant differences between wild-type and Ostpr075-1 plants (Student’s t test, P < 0.001).

Phenotypic observation revealed that all alleles of Ostpr075 displayed late heading dates under both SDs and LDs (Figure 4, B–E). To validate the notion that the late-flowering phenotype of Ostpr075 is attributed to the loss function of OsTPR075, we transformed Ostpr075-1 homozygous calli with the genomic construct gOsTPR075 or gOsTPR075-3FLAG harboring the 6.1-kb OsTPR075 genomic region including the 3.0-kb 5′-upstream sequence and the entire 3.1-kb coding sequence plus introns. Homozygous transgenic plants were selected, and at least nine independent transformants containing a single-copy transgene based on a 3:1 Mendelian segregation ratio were obtained. Phenotypic examination of six transgenic lines revealed that the late heading date of Ostpr075-1 was rescued to different extents in these lines under both SDs and LDs (Figure 4, F and G, respectively), suggesting that the late-flowering phenotype of Ostpr075-1 was caused by the loss function of OsTPR075.

To further investigate the role of OsTPR075 in controlling flowering time, we also generated the overexpression lines of OsTPR075. Among the 15 transgenic lines generated, 5 representative lines were selected for further study. OsTPR075 expression was upregulated in these lines and all of these lines displayed early flowering under both SDs and LDs (Supplemental Figure S8, A–C). Meanwhile, the expression of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 was enhanced when OsTPR075 was overexpressed (Supplemental Figure S8, D and E), which is consistent with the early flowering phenotype of these lines. Collectively, our results suggest that OsTPR075 promotes flowering in rice. Furthermore, the mRNA levels and protein abundance of OsTPR075 were not affected by the circadian clock or day length (Supplemental Figure S9).

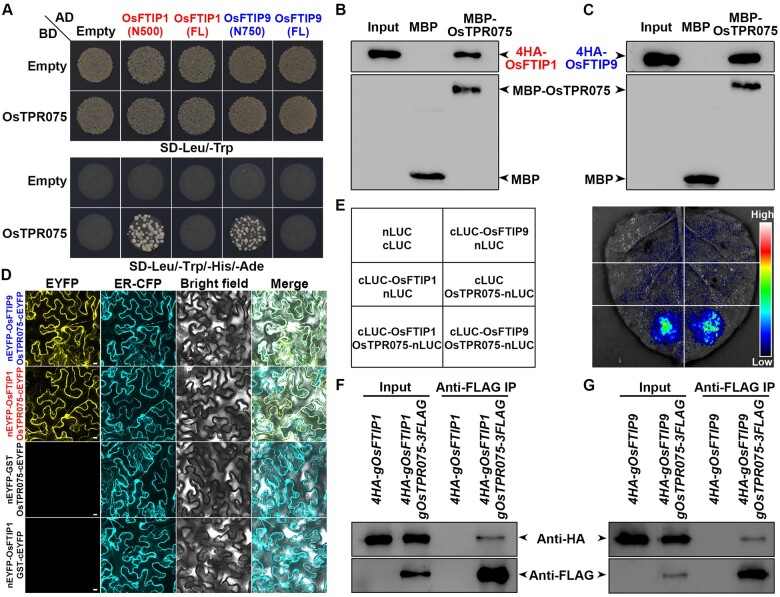

OsTPR075 interacts with OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9

Given that Ostpr075 exhibited late heading date similar to Osftip1 under LDs or Osftip9 under SDs, we conjecture that OsTPR075 may interact with both OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9. To verify the hypothesis, we conducted detailed analyses of their physical interaction via various approaches. The yeast two-hybrid assays implied the interaction between OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 N500 or OsFTIP9 N750, but not the FL OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9 (Figure 5A). Moreover, the OsTPR075 interacted with OsFTIP1 via the third C2 domain and with OsFTIP9 via the second C2 domain (Supplemental Figure S10). The maltose-binding protein (MBP) pull-down assay showed that 4HA-OsFTIP1 or 4HA-OsFTIP9 generated from rice protoplasts was bound by MBP-OsTPR075, but not by MBP (Figure 5, B and C). BiFC assay showed the EYFP signals of OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9 in N. benthamiana epidermal cells except the nuclei, but not in the negative controls (Figure 5D). Furthermore, the LCI assay revealed strong luciferase signals when OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9 were both present, suggesting the in vivo interaction of OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9 in plants (Figure 5E). Lastly, we crossed Osftip1-1 4HA-gOsFTIP1 or Osftip9-1 4HA-gOsFTIP9 with Ostpr075-1 gOsTPR075-3FLAG #16, to obtain 4HA-gOsFTIP1 gOsTPR075-3FLAG or 4HA-gOsFTIP9 gOsTPR075-3FLAG plants for CoIP analysis. The results revealed that 4HA-OsFTIP1 or 4HA-OsFTIP9 could be immunoprecipitated with OsTPR075-3FLAG, demonstrating the in vivo interaction of OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9 in rice (Figure 5, F and G). These data collectively confirm that OsTPR075 interacts with both OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9. In addition, we generated the transgenic lines of ProOsFTIP9:GUS and ProOsTPR075:GUS driven by the promoters harbored in the genomic fragments that rescued the late-flowering phenotypes of Osftip9 and Ostpr075, respectively. The GUS staining results showed that both ProOsFTIP9:GUS and ProOsTPR075:GUS exhibited the GUS signal specifically in the vascular tissues of leaves. Furthermore, examination of transverse sections revealed that OsFTIP9 and OsTPR075 were specifically expressed in the phloem, including CCs (Supplemental Figure S11), which is similar to the expression patterns of FTIP1 in Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 2012) and OsFTIP1 in rice (Song et al., 2017), indicating that OsFTIP9 and OsTPR075 act in the phloem to promote flowering.

Figure 5.

OsTPR075 interacts with OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9. A, Yeast two-hybrid assay of interactions between OsTPR075 and FL or truncated (including C2 domains) OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9. Transformed yeast cells were grown on SD–Leu/–Trp and SD–Leu/–Trp/–His/–Ade medium. B, and C, In vitro MBP pull-down assay of the interaction between OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9. 4HA-OsFTIP1 or 4HA-OsFTIP9 generated from rice protoplasts was incubated with immobilized MBP or MBP-OsTPR075, respectively. Immunoblot analysis was performed using anti-HA or anti-MBP antibodies. Input, 5% of the 4HA-OsFTIP1 or 4HA-OsFTIP9 generated from rice protoplasts. D, BiFC analysis of the interaction between OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9. GST was used as a negative control. Merge, merge of EYFP, ER-CFP and bright field images. Scale bars, 10 μm. E, LCI assay of interactions between OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9. The indicated fusion pairs were coexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves. F, and G, In vivo interactions between OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9 shown by CoIP in rice. Total protein extracts from leaves of 4HA-gOsFTIP1, 4HA-gOsFTIP1 gOsTPR075-3FLAG or 4HA-gOsFTIP9, 4HA-gOsFTIP9 gOsTPR075-3FLAG plants were immunoprecipitated by anti-FLAG beads. The input and coimmunoprecipitated protein were detected by anti-HA (upper) or anti-FLAG (lower) antibody.

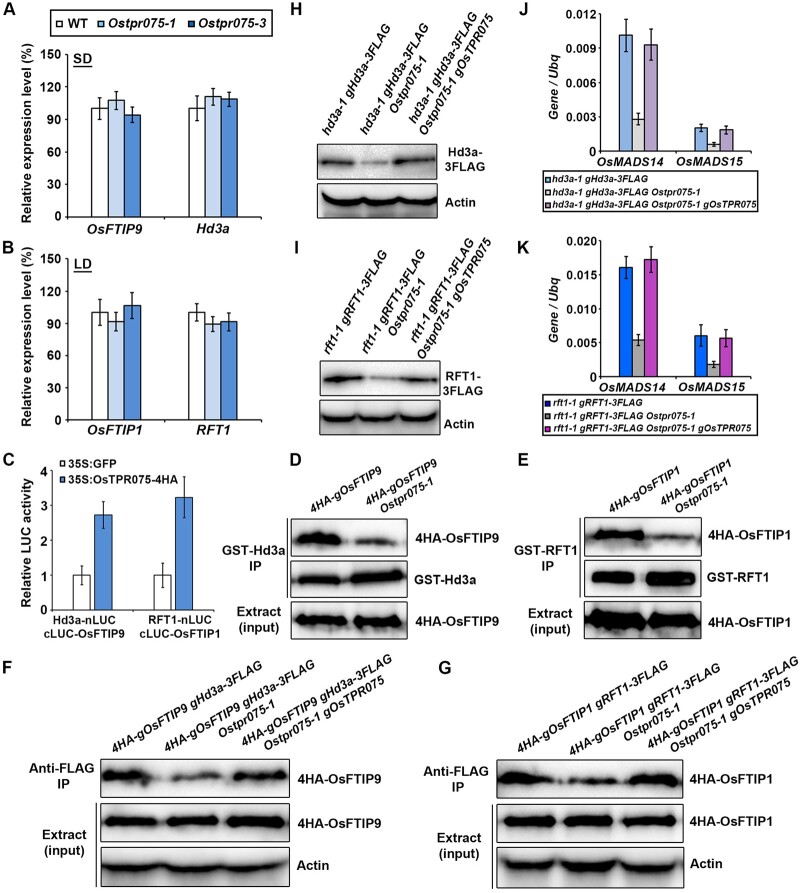

OsTPR075 strengthens the OsFTIP9–Hd3a and OsFTIP1–RFT1 interactions

Since OsTPR075 promotes flowering in rice under both SDs and LDs (Figure 4), we investigated the in-depth mechanism regulating heading date. First, we examined the expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in Ostpr075 mutants and control plants and found that the expression of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in the shoot apices of Ostpr075 was significantly downregulated compared to wild-type plants (Supplemental Figure S12), which is consistent with the late-flowering phenotype of Ostpr075. Nonetheless, the mRNA accumulation of OsFTIP1, OsFTIP9, RFT1, and Hd3a in the leaves was not altered (Figure 6, A and B), implying that the downregulation of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in Ostpr075 was not caused by the transcription activation of Hd3a and RFT1. Given that OsTPR075 interacts with OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9 and the specific interaction of OsFTIP9–Hd3a and OsFTIP1–RFT1 (Figure 5;Supplemental Figure S13), we reasoned that these interactions might affect the interactions between OsFTIPs and florigen, thus influencing the transport efficiency of florigen. We then determined whether OsTPR075 alters the interaction intensity between OsFTIP1 and RFT1 or OsFTIP9 and Hd3a. The LCI assays validated that the interactions between Hd3a and OsFTIP9, RFT1, and OsFTIP1 were enhanced by the introduction of OsTPR075 (Figure 6C;Supplemental Figure S14). Additionally, in semi pull-down assays, less 4HA–OsFTIP9 or 4HA–OsFTIP1 was precipitated by GST-Hd3a or GST-RFT1 beads in the Ostpr075-1 background (Figure 6, D and E), suggesting that OsTPR075 positively affects the interaction of each pair of proteins. Furthermore, the CoIP assays revealed that 4HA-OsFTIP9 immunoprecipitated was decreased in 4HA–OsFTIP9 gHd3a-3FLAG Ostpr075-1 than that in 4HA-OsFTIP9 gHd3a-3FLAG by anti-FLAG beads. Notably, when Ostpr075-1 was complemented, the abundance of 4HA–OsFTIP9 immunoprecipitated with Hd3a-3FLAG in 4HA-OsFTIP9 gHd3a-3FLAG Ostpr075-1 gOsTPR075 was comparable with that in 4HA–OsFTIP9 gHd3a-3FLAG (Figure 6F), demonstrating that OsTPR075 is essential for the interaction between OsFTIP9 and Hd3a in vivo. Likewise, the CoIP assays also showed that OsTPR075 enhances the in vivo interaction between RFT1 and OsFTIP1 (Figure 6G). Collectively, these data substantiate that OsTPR075 strengthens the physical interaction between OsFTIPs and florigen.

Figure 6.

OsTPR075 strengthens interactions between Hd3a and OsFTIP9 or RFT1 and OsFTIP1. A, and B, Expression levels of various genes in wild-type and Ostpr075. Relative expression levels of OsFTIP9 and Hd3a (A), OsFTIP1 and RFT1 (B) in the leaves of three genotypes under SDs and LDs, respectively. Leaves of each genotype were collected at 35 DAS under SDs and 50 DAS under LDs. The expression levels of each gene normalized to Ubq expression are shown relative to the level of the wild-type, which was set to 100%. Error bars denote sd (n = 3). C, LCI assay of the effect of OsTPR075 on the interaction between Hd3a and OsFTIP9 or RFT1 and OsFTIP1. Error bars indicate sd (n = 3). D, and E, Semi pull-down assay evaluating the interactions between Hd3a and OsFTIP9 or RFT1 and OsFTIP1 in the presence or absence of OsTPR075. GST-Hd3a (D) or GST-RFT1 (E) beads were used for immunoprecipitation. F, and G, CoIP assays of the OsFTIP9–Hd3a or OsFTIP1–RFT1 interaction in the presence or absence of OsTPR075. Actin was used as a loading control. For (D) and (F), leaves of the indicated genotypes were collected at 35 DAS under SDs; For (E) and (G), leaves of the indicated genotypes were collected at 50 DAS under LDs. H, and I, Immunoblot analyses using anti-FLAG antibody showing the abundance of Hd3a-3FLAG (H) or RFT1-3FLAG (I) in shoot apices of the indicated genotypes. Shoot apices of the indicated plants were collected at 35 DAS under SDs in (H) or 50 DAS under LDs in (I). Actin was used as a loading control. J, and K, The expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in the shoot apices of plants of various genetic backgrounds grown at 40 DAS under SDs (H) or 60 DAS under LDs (I). Results were normalized against the expression levels of Ubq based on three biological replicates. Error bars indicate sd.

Next, the florigen abundances in the shoot apices and leaves were detected in the absence or presence of OsTPR075 subsequently. The immunoblot result revealed that the accumulation of Hd3a-3FLAG was significantly lower in shoot apices but not leaves of hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Ostpr075-1 versus hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG. Nonetheless, supply of OsTPR075 activity in hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Ostpr075-1 gOsTPR075 restored the abundance of Hd3a-3FLAG (Figure 6H;Supplemental Figure S15A). In addition, the abundance of RFT1-3FLAG protein exhibited a similar pattern (Figure 6I;Supplemental Figure S15B). Consistently, the expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 were downregulated in hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG or rft1-1 gRFT1-3FLAG in the absence of OsTPR075 but were recovered in the presence of OsTPR075 in hd3a-1 gHd3a-3FLAG Ostpr075-1 gOsTPR075 or rft1-1 gRFT1-3FLAG Ostpr075-1 gOsTPR075 (Figure 6, J and K). These results suggest that OsTPR075 positively affects the abundances of Hd3a-3FLAG and RFT1-3FLAG proteins in the shoot apices.

We further explored the genetic relationship of OsTPR075, OsFTIP9, Hd3a, and OsTPR075, OsFTIP1, RFT1 by comparing the flowering phenotypes of the single, double and triple mutants under SDs or LDs, respectively. Under SDs, the flowering phenotype of Osftip9 hd3a was similar to that of hd3a, implying that OsFTIP9 modulates flowering via Hd3a. Meanwhile, Ostpr075 Osftip9 double mutant flowered similarly to Osftip9, and Ostpr075 Osftip9 hd3a exhibited comparable heading dates with Osftip9 hd3a (Supplemental Figure S16A). These genetic data demonstrate that these three genes act in the same pathway under SDs. Similarly, OsTPR075, OsFTIP1, and RFT1 were found to function in a common pathway under LDs (Supplemental Figure S16B). In addition, we checked the abundance of Hd3a or RFT1 in various genetic backgrounds under SDs or LDs by immunoblot analysis. The accumulation of Hd3a-3FLAG was significantly reduced in the shoot apices of Osftip9-1, Ostpr075-1, and Osftip9-1 Ostpr075-1 compared to the wild-type. Meanwhile, the abundance of Hd3a-3FLAG was comparable in Osftip9-1 and Osftip9-1 Ostpr075-1, indicating that regulation of florigen transport by OsTPR075 depends on OsFTIP9 under SDs (Supplemental Figure S17A). A similar trend of RFT1-3FLAG accumulation was observed in single and double mutants of OsFTIP1 and OsTPR075 under LDs (Supplemental Figure S17B). Taken together, these data suggest that OsTPR075 regulates flowering via OsFTIP1/9-mediated florigen transport.

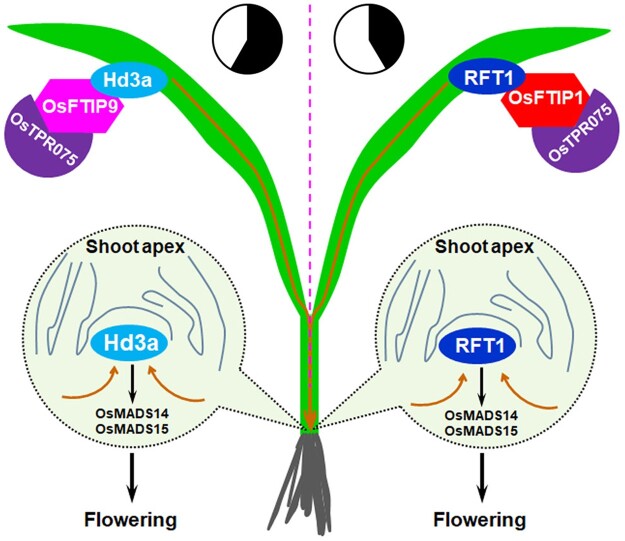

In summary, we report that OsFTIP9 interacts with Hd3a and facilitates its export from CCs to the SEs under SDs. Meanwhile, OsTPR075 strengthens the interaction between Hd3a and OsFTIP9 or RFT1 and OsFTIP1 to enhance the florigen transport efficiency from leaves to the SAM, where the florigen activate the expression of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15, thus promoting floral meristem development in rice (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

A model describing OsTPR075–OsFTIP1/9 complex-mediated florigen transport in rice. Under SDs, OsFTIP9 interacts with Hd3a and facilitates its export from CCs to SEs. Under LDs, OsFTIP1 helps transport RFT1 from leaves to the SAM. OsTPR075 strengthens the interaction between Hd3a and OsFTIP9 or RFT1 and OsFTIP1 to enhance the efficiency of florigen transport from leaves to the SAM, where the florigen activates the expression of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15, thus promoting floral meristem development.

Discussion

Rice is one of the most important crops worldwide and heading date is a critical trait that determines the regional adaptability and yield of rice (Jung and Müller, 2009; Srikanth and Schmid, 2011; Song et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2021). Hd3a and RFT1 have been identified as specific florigens that play major roles in rice flowering under SD and LD conditions, respectively (Tamaki et al., 2007; Komiya et al., 2008, 2009). We previously demonstrated that OsFTIP1 is required for the export of RFT1 from CCs to SEs and affects the movement of RFT1 to the SAM under LDs (Song et al., 2017). However, how Hd3a, the major florigen under SDs, is transported in rice, a facultative SD plant, remains unclear. Here, we showed that OsFTIP9 specifically regulates rice flowering time under SDs by modulating Hd3a transport from CCs to SEs. In addition, we revealed that a TPR-containing protein, OsTPR075, interacts with OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9 and facilitates their ability to transport florigen in leaves, thus affecting Hd3a and RFT1 abundance in the SAM and consequently modulating flowering time under both SDs and LDs (Figure 6J). These findings shed light on the mechanisms underlying the regulation of florigen transport in the monocot crop rice and suggest that the OsTPR075–OsFTIPs complex is integral to their effects on florigen transport in source tissues.

Notably, a previous study showed that SYP121 interacts with QKY and coordinately regulates FT export from CCs to SEs, thus affecting FT transport through the phloem to the SAM in Arabidopsis (Liu et al., 2019). Whether SYP121 orthologs in rice affect the role of OsFTIPs in regulating Hd3a/RFT1 movement in a similar manner should be further explored.

It is noteworthy that the TPR domain-containing protein OsTPR075 interacts with both OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9 and enhances their ability to transport florigen, thereby promoting flowering under both LD and SD conditions. These findings suggest that the TPR-mediated trafficking complex is ultimately important for regulating florigen transport in rice. Given that TPR motifs are important for the functions of chaperones and protein transport complexes (Blatch and Lässle, 1999; D'Andrea and Regan, 2003; Allan and Ratajczak, 2011; Wei and Han, 2017), it would be interesting to identify additional interactors of OsTPR075 and the crystal structure of this protein. Moreover, the potential relevance of the FTIP–TPR interaction for members of the FTIP and TPR families involved in flowering time regulation in other plants would be worth exploring. Taken together, our findings suggest that the OsTPR075–OsFTIP1/9–RFT1/Hd3a module is ultimately important for the regulation of florigen transport in rice. Hence, further study of this module in other flowering plants, especially crops, will advance our understanding and utilization of the molecular mechanism of florigen transport and flowering time regulation.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Rice (O.sativa ssp. Japonica cultivar Nipponbare) was grown in growth rooms (10-h light at 30°C/14-h dark at 25°C for SDs and 14-h light at 30°C/10 h dark at 25°C for LDs) with a relative humidity of ∼70%. Light at a wavelength of 500–700 nm, 100–200 μmol m−2 s−2 was provided by fluorescent white light tubes.

Plasmid construction and plant transformation

To construct psgR-CAS9-Os-OsFTIP9/OsTPR075, the psgR-Cas9-Os backbone was digested by BbsI and ligated with the synthesized sgRNA oligos. The resulting fragments were subcloned into the pCAMBIA1300 binary vector in the HindIII/EcoRI site for stable rice transformation (Feng et al., 2014). To create OsTPR075gOsTPR075-3FLAG and 4HA-gOsFTIP9, the genomic fragments of OsTPR075OsTPR075 and OsFTIP9 were amplified and cloned into pENTER-3FLAG/4HA, respectively. DNA fragments were transferred from the entry vector to pHGW by LR reaction performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Primers used to create the above constructs are listed in Supplemental Table S3. Transgenic rice plants were generated by Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of rice calli as previously described (Toki et al., 2006). All transgenic rice plants were selected on 50 μg mL−1 hygromycin.

LC–MS/MS analysis

Wild-type and Osftip9 4HA-gOsFTIP9 plants were collected and ground into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen. Total protein was isolated from the samples with RIPA buffer (150-mM NaCl, 50-mM Tris (pH 8.0), 5-mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 1 × protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche, Basel, Switzerland]). The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and incubated with anti-HA agarose beads (Yeasen, Shanghai, China) for 4 h at 4°C. After washing, the immunoprecipitated protein mixture was eluted and analyzed by LC–MS/MS using a Q Exactive HF-X System (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The spectrum data were searched against the RGAP database using Thermo Proteome Discoverer.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated from the samples with a Plant RNA Kit (Omega, Biel/Bienne, Switzerland) and reverse transcribed with Hifair III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR (Yeasen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR was performed in triplicate on a Light Cycler 480 real-time system (Roche) with Hieff qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Yeasen). The relative expression levels were calculated as previously reported (Liu et al., 2007). Expression analysis was performed with three independent batches of plants. The sampling times and sampled tissues are described in detail in the corresponding figure legends. All primers used for gene expression analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S3.

Transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves and rice protoplasts

The coding sequences of OsFTIP9 and OsTPR075 were amplified and separately cloned into pGreen-GFP. Agrobacteria were cultured overnight until the optical density600 (OD) was ∼1.0, harvested, and resuspended to OD600 ∼0.5 in infiltration buffer containing 10-mM MgCl2, 100-mM acetosyringone, and 10-mM MES, pH 5.6. Cultures with different combinations of constructs were infiltrated into 3-week-old N.benthamiana leaves. Signals were observed under a confocal microscope (Olympus FV3000) at 40–48 h after infiltration. Isolation of rice protoplasts and PEG-mediated transfection were performed as described previously (Bart et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2021). After transformation, the protoplasts were incubated in the dark for 12–16 h for further analysis.

Histochemical analysis of GUS expression

For GUS staining, tissues were infiltrated with staining solution (50-mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 0.5-mM potassium ferrocyanide, 0.5-mM potassium ferricyanide, and 0.5-mg mL−1 X-Gluc) in a vacuum chamber and subsequently incubated with the same solution at 37°C for 6 h. The samples were dehydrated through an ethanol series and an ethanol/Histoclear series and finally embedded in paraffin for sectioning at a thickness of 8 µm using an Ultracut UCT ultramicrotome (Leica).

Yeast two-hybrid assay

For the yeast two-hybrid assay, the coding sequences of Hd3a, OsFTIP9, and OsTPR075 were amplified and cloned into pGBKT7 or pGADT7 (Clontech). Yeast two-hybrid assays were carried out using the Yeastmaker Yeast Transformation System 2 (Clontech).

Pull-down assay

To produce GST/MBP-tagged proteins, the cDNAs encoding Hd3a, RFT1, and OsTPR075 were cloned into the pGEX-4T-1 (Pharmacia, New Jersey, USA) and pMAL-C2X (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) vectors, respectively. The above constructs and the empty pGEX-4T-1 or pMAL-C2X vector were transformed into Escherichiacoli Rosetta (DE3) (Novagen) cells, and protein expression was induced by treatment with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactoside at 16°C. The soluble GST or MBP fusion proteins were extracted and immobilized on glutathione Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences, Amersham, UK) or amylose resin (New England Biolabs) for subsequent pull-down assays. To produce HA-tagged OsFTIP1 and OsFTIP9, the plasmids pENTR–4HA–OsFTIP1 and pENTR–4HA–OsFTIP9 were transformed into rice protoplasts to generate 4HA–OsFTIP1 or 4HA–OsFTIP9 protein. The 4HA–OsFTIP1 or 4HA–OsFTIP9 protein was then incubated with the immobilized MBP and MBP-OsTPR075 or GST and GST-Hd3a, GST-RFT1, respectively. Proteins retained on the beads were resolved by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and detected with anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA,, 1:1,000 dilution).

BiFC analysis

The cDNAs encoding OsFTIP9, Hd3a, OsTPR075, and OsFTIP1 were separately cloned into primary pSAT1 vectors. The resulting cassettes (including fusion protein genes driven by constitutive promoters) were cloned into pGreen binary vector pHY105 and transformed into Agrobacterium for BiFC analysis as previously described (Sparkes et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2020). GST proteins fused with nEYFP or cEYFP were used as negative controls.

LCI and luciferase activity assay

For the firefly LCI assay, the coding sequences of Hd3a and OsTPR075 were fused with the N-terminus of luciferase (Hd3a-nLUC and OsTPR075-nLUC). The FL coding sequences of OsFTIP9 and OsFTIP1 were fused with the C-termini of luciferase (cLUC–OsFTIP9 and cLUC–OsFTIP1) to examine the interactions of Hd3a and OsFTIP9, OsTPR075 and OsFTIP1, or OsTPR075 and OsFTIP9. The constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium and co-infiltrated into 3-week-old N.benthamiana leaves. Signals were observed using a low-light cooled charge-coupled device imaging apparatus (Tanon 5200) after 40–48 h cultivation. LUC activity was measured as described previously (Chen et al., 2008).

Immunoblotting

For total protein isolation, rice tissues were ground in liquid nitrogen and resuspended in RIPA buffer. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bio-Rad protein assay. Total proteins (25–30 μg) from each sample were resolved by SDS–PAGE and detected by anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-GFP (Abcam, 1:2,000) or anti-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:5,000) antibodies. Immunoblotting was performed using Super ECL Star Chemiluminescent Substrate (US Everbright).

Immunogold transmission electron microscopy

Immunoelectron microscopy was performed as previously described (Liu et al., 2012). Samples were fixed in paraformaldehyde–glutaraldehyde solution (2% and 2.5%, respectively) overnight at room temperature and imbedded in LR white medium (EMS). Ultrathin sections were mounted on nickel grids, blocked with 1% BSA in TBST (20-mM Tris, 500-mM NaCl, and 0.05% Tween-20, pH 7.5) for 30 min, and incubated with anti-HA antibody at 1:5 dilution (v/v) for 1 h. After washing three times with TBST, the grids were incubated for 40 min with 25-nm gold-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (EMS) that was diluted 1:20 with blocking solution. The grids were subsequently washed with TBST and distilled water. After staining the tissues with 2% uranyl acetate for 15 min at room temperature, photomicrographs were taken using a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, H-7650). To quantitatively analyze immunogold labeling, electron micrographs of randomly photographed immunogold-labeled transverse sections were digitized. The number of gold particles and the cell area were measured with ImageJ software. We analyzed 100 individual sections from seven different plants per genotype to calculate the density of gold particles throughout the projected cell area. The results are presented as the mean number of gold particles per square micrometer plus or minus the SD and statistically evaluated by a two-tailed paired Student’s t test.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in Microsoft Excel via two-tailed Student’s t test, and the P-values are summarized in Supplemental Data Set 1.

Accession numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under the following accession numbers: OsFTIP1 (Os06g0614000), OsFTIP9 (Os01g0587300), Hd3a (Os06g0157700), OsTPR075 (Os03g0200600), OsMADS14 (Os03g0752800), and OsMADS15 (Os07g0108900).

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Bioinformatic analysis of OsFTIP9 protein.

Supplemental Figure S2. Hd3a interacts with the second C2 domain of OsFTIP9 in yeast.

Supplemental Figure S3. Complementation of Osftip9-1 by the OsFTIP9 genomic fragment.

Supplemental Figure S4. No flowering defects were observed in Osftip9 mutants under LDs.

Supplemental Figure S5. The expression of Hd3a is not altered in Osftip9.

Supplemental Figure S6. Hd3a levels in leaves of the indicated genotypes.

Supplemental Figure S7. OsTPR075 is identified as a potential interacting partner of OsFTIP9.

Supplemental Figure S8. Overexpression of OsTPR075 results in an early heading date in rice.

Supplemental Figure S9. The expression patterns of OsTPR075.

Supplemental Figure S10. Yeast two-hybrid assay of interactions between OsTPR075 and various C2 domains of OsFTIP1 or OsFTIP9.

Supplemental Figure S11. GUS expression driven by the OsFTIP9 and OsTPR075 promoters.

Supplemental Figure S12. Expression levels of OsMADS14 and OsMADS15 in wild-type and Ostpr075.

Supplemental Figure S13. No detectable interactions of OsFTIP1–Hd3a and OsFTIP9–RFT1 were observed.

Supplemental Figure S14. Immunoblot analysis of GFP or OsTPR075-4HA levels are shown in Figure 6G.

Supplemental Figure S15. Hd3a and RFT1 levels in leaves of the indicated genotypes.

Supplemental Figure S16. Heading dates of various mutants.

Supplemental Figure S17. Hd3a and RFT1 levels in the SAMs of the indicated genotypes.

Supplemental Table S1. Potential interacting proteins of Hd3a identified by yeast two-hybrid screening.

Supplemental Table S2. Potential interacting partners of OsFTIP9 identified by CoIP followed by LC–MS/MS analysis.

Supplemental Table S3. List of primers used in this study.

Supplemental Data Set 1. Summary of statistical analyses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. H. Zhang for generously providing the psgR-CAS9-Os vector.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32000213 and 32070209), Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LR21C130001 and LQ21C020003), Leading Innovative and Entrepreneur Team Introduction Program of Zhejiang (2019R01002), Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang (2020C02002 and 2021C02063-1), and the Singapore National Research Foundation Investigatorship Program (NRF-NRFI2016-02).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Contributor Information

Liang Zhang, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, China National Rice Research Institute, Hangzhou 311400, China; College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Resources, Institute of Crop Science, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Fan Zhang, College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Resources, Institute of Crop Science, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Xuan Zhou, Department of Biological Sciences and Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, National University of Singapore 117543, Singapore.

Toon Xuan Poh, Department of Biological Sciences and Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, National University of Singapore 117543, Singapore.

Lijun Xie, College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Resources, Institute of Crop Science, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Jun Shen, College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Resources, Institute of Crop Science, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Lijia Yang, College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Resources, Institute of Crop Science, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Shiyong Song, College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Resources, Institute of Crop Science, Hangzhou 310058, China.

Hao Yu, Department of Biological Sciences and Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory, National University of Singapore 117543, Singapore.

Ying Chen, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, China National Rice Research Institute, Hangzhou 311400, China; College of Agriculture and Biotechnology, Zhejiang University, State Key Laboratory of Rice Biology, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Crop Genetic Resources, Institute of Crop Science, Hangzhou 310058, China.

L.Z., F.Z., Z.X., S.S., H.Y., and Y.C. conceived the project and designed the experiments. L.Z., F.Z., Z.X., T.X.P., L.X., J.S., and L.Y. performed the experiments; L.Z., S.S., H.Y., and Y.C. conducted all statistical analyses. L.Z., F.Z., Z.X., S.S., H.Y., and Y.C. analyzed the data. L.Z., S.S., H.Y., and Y.C. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plcell) are: Shiyong Song (shiyongsong@zju.edu.cn), Hao Yu (dbsyuhao@nus.edu.sg), and Ying Chen (chenying02@caas.cn).

References

- Allan RK, Ratajczak T (2011) Versatile TPR domains accommodate different modes of target protein recognition and function. Cell Stress Chaperones 16: 353–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart R, Chern M, Park CJ, Bartley L, Ronald PC (2006) A novel system for gene silencing using siRNAs in rice leaf and stem-derived protoplasts. Plant Methods 2: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blatch GL, Lässle M (1999) The tetratricopeptide repeat: a structural motif mediating protein-protein interactions. Bioessays 21: 932–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai M, Zhu S, Wu M, Zheng X, Wang J, Zhou L, Zheng T, Cui S, Zhou S, Li C, et al. (2021) DHD4, a CONSTANS-like family transcription factor, delays heading date by affecting the formation of the FAC complex in rice. Mol Plant 14: 330–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Zou Y, Shang Y, Lin H, Wang Y, Cai R, Tang X, Zhou JM (2008) Firefly luciferase complementation imaging assay for protein-protein interactions in plants. Plant Physiol 146: 368–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Song S, Gan Y, Jiang L, Yu H, Shen L (2020) SHAGGY-like kinase 12 regulates flowering through mediating CONSTANS stability in Arabidopsis. Sci Adv 6: eaaw0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Shen J, Zhang L, Qi H, Yang L, Wang H, Wang J, Wang Y, Du H, Tao Z, et al. (2021) Nuclear translocation of OsMFT1 that is impeded by OsFTIP1 promotes drought tolerance in rice. Mol Plant 14: 1297–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho LH, Yoon J, An G (2017) The control of flowering time by environmental factors. Plant J 90: 708–719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier L, Vincent C, Jang S, Fornara F, Fan Q, Searle I, Giakountis A, Farrona S, Gissot L, Turnbull C, et al. (2007) FT protein movement contributes to long-distance signaling in floral induction of Arabidopsis. Science 316: 1030–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Andrea LD, Regan L (2003) TPR proteins: the versatile helix. Trends Biochem Sci 28: 655–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doi K, Izawa T, Fuse T, Yamanouchi U, Kubo T, Shimatani Z, Yano M, Yoshimura A (2004) Ehd1, a B-type response regulator in rice, confers short-day promotion of flowering and controls FT-like gene expression independently of Hd1. Genes Dev 18: 926–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z, Mao Y, Xu N, Zhang B, Wei P, Yang DL, Wang Z, Zhang Z, Zheng R, Yang L, et al. (2014) Multigeneration analysis reveals the inheritance, specificity, and patterns of CRISPR/Cas-induced gene modifications in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111: 4632–4637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara S, Oda A, Yoshida R, Niinuma K, Miyata K, Tomozoe Y, Tajima T, Nakagawa M, Hayashi K, Coupland G, et al. (2008) Circadian clock proteins LHY and CCA1 regulate SVP protein accumulation to control flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20: 2960–2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goebl M, Yanagida M (1991) The TPR snap helix: a novel protein repeat motif from mitosis to transcription. Trends Biochem Sci 16: 173–177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger KE, Wigge PA (2007) FT protein acts as a long-range signal in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 17: 1050–1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung C, Müller AE (2009) Flowering time control and applications in plant breeding. Trends Plant Sci 14: 563–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SL, Lee S, Kim HJ, Nam HG, An G (2007) OsMADS51 is a short-day flowering promoter that functions upstream of Ehd1, OsMADS14, and Hd3a. Plant Physiol 145: 1484–1494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya R, Yokoi S, Shimamoto K (2009) A gene network for long-day flowering activates RFT1 encoding a mobile flowering signal in rice. Development 136: 3443–3450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya R, Ikegami A, Tamaki S, Yokoi S, Shimamoto K (2008) Hd3a and RFT1 are essential for flowering in rice. Development 135: 767–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Jeong DH, Lee DY, Yi J, Ryu CH, Kim SL, Jeong HJ, Choi SC, Jin P, Yang J, et al. (2010) OsCOL4 is a constitutive flowering repressor upstream of Ehd1 and downstream of OsphyB. Plant J 63: 18–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, Belanger H, Lee YJ, Varkonyigasic E, Taoka KI, Miura E, Xoconostlecazares B, Gendler KC, Jorgensen RA, Phinney BS (2007) FLOWERING LOCUS T protein may act as the long-distance florigenic signal in the cucurbits. Plant Cell 19: 1488–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Zhou J, Bracha-Drori K, Yalovsky S, Ito T, Yu H (2007) Specification of Arabidopsis floral meristem identity by repression of flowering time genes. Development 134: 1901–1910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhang Y, Yu H (2020) Florigen trafficking integrates photoperiod and temperature signals in Arabidopsis. J Integra Plant Biol 62: 1385–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li C, Liang Z, Yu H (2018) Characterization of multiple C2 domain and transmembrane region proteins in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 176: 2119–2132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Li C, Teo ZWN, Zhang B, Yu H (2019) The MCTP-SNARE complex regulates florigen transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 31: 2475–2490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Liu C, Hou X, Xi W, Shen L, Tao Z, Wang Y, Yu H (2012) FTIP1 is an essential regulator required for florigen transport. PLoS Biol 10: e1001313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu J, Warthmann N, Küttner F, Schmid M (2007) Export of FT protein from phloem companion cells is sufficient for floral induction in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 17: 1055–1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara K, Yamanouchi U, Wang ZX, Minobe Y, Izawa T, Yano M (2008) Ehd2, a rice ortholog of the maize INDETERMINATE1 gene, promotes flowering by up-regulating Ehd1. Plant Physiol 148: 1425–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouradov A, Cremer F, Coupland G (2002) Control of flowering time: interacting pathways as a basis for diversity. Plant Cell 14: S111–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenführ A (2007) A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J 51: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto Y, Nonoue Y, Yano M, Izawa T (2016) Hd1,a CONSTANS ortholog in rice, functions as an Ehd1 repressor through interaction with monocot-specific CCT-domain protein Ghd7. Plant J 86: 221–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SJ, Kim SL, Lee S, Je BI, Piao HL, Park SH, Kim CM, Ryu CH, Park SH, Xuan YH, et al. (2008) Rice Indeterminate 1 (OsId1) is necessary for the expression of Ehd1 (Early heading date 1) regardless of photoperiod. Plant J 56: 1018–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q, Zhu C, Liu T, Zhang S, Feng S, Wu C (2021) Phosphorylation of OsFD1 by OsCIPK3 promotes the formation of RFT1-containing florigen activation complex for long-day flowering in rice. Mol Plant 14: 1135–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Chen Y, Liu L, See YHB, Mao C, Gan Y, Yu H (2018) OsFTIP7 determines auxin-mediated anther dehiscence in rice. Nat Plants 4: 495–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, Chen Y, Liu L, Wang Y, Bao S, Zhou X, Teo ZWN, Mao C, Gan Y, Yu H (2017) OsFTIP1-mediated regulation of florigen transport in rice is negatively regulated by the ubiquitin-like domain kinase OsUbDKγ4. Plant Cell 29: 491–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song YH, Shim JS, Kinmonth-Schultz HA, Imaizumi T (2015) Photoperiodic flowering: time measurement mechanisms in leaves. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66: 441–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes IA, Runions J, Kearns A, Hawes C (2006) Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat Protoc 1: 2019–2025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srikanth A, Schmid M (2011) Regulation of flowering time: all roads lead to Rome. Cell Mol Life Sci 68: 2013–2037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Shimamoto K (2011) Heading date 1 (Hd1), an ortholog of Arabidopsis CONSTANS, is a possible target of human selection during domestication to diversify flowering times of cultivated rice. Genes Genet Syst 86: 175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaki S, Matsuo S, Wong HL, Yokoi S, Shimamoto K (2007) Hd3a protein is a mobile flowering signal in rice. Science 316: 1033–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taoka KI, Ohki I, Tsuji H, Furuita K, Hayashi K, Yanase T, Yamaguchi M, Nakashima C, Purwestri YA, Tamaki S, et al. (2011) 14-3-3 proteins act as intracellular receptors for rice Hd3a florigen. Nature 476: 332–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Hara N, Ono K, Onodera H, Tagiri A, Oka S, Tanaka H (2006) Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J 47: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji H, Taoka KI, Shimamoto K (2013) Florigen in rice: complex gene network for florigen transcription, florigen activation complex, and multiple functions. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 228–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K, Han P (2017) Comparative functional genomics of the TPR gene family in Arabidopsis, rice and maize. Mol Breed 37: 152 [Google Scholar]

- Wochnik GM, Rüegg Jl, Abel GA, Schmidt U, Holsboer F, Rein T (2005) FK506-binding proteins 51 and 52 differentially regulate dynein interaction and nuclear translocation of the glucocorticoid receptor in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 280: 4609–4616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Xing Y, Weng X, Zhao Y, Tang W, Wang L, Zhou H, Yu S, Xu C, Li X, et al. (2008) Natural variation in Ghd7 is an important regulator of heading date and yield potential in rice. Nat Genet 40: 761–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Zhu S, Cui S, Hou H, Wu H, Hao B, Cai L, Xu Z, Liu L, Jiang L, et al. (2021) Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of heading date in rice. New Phytol 230: 943–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Liu L, Shen L, Yu H (2016) NaKR1 regulates long-distance movement of FLOWERING LOCUS T in Arabidopsis. Nat Plants 2: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zong W, Ren D, Huang M, Sun K, Feng J, Zhao J, Xiao D, Xie W, Liu S, Zhang H, et al. (2021) Strong photoperiod sensitivity is controlled by cooperation and competition among Hd1, Ghd7 and DTH8 in rice heading. New Phytol 229: 1635–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.